If you just looked at Germany’s expected goal numbers you’d think they were extremely unlucky to be eliminated in the World Cup. That’s a good reason to not just look at expected goals numbers.

In their three group stage games, Germany averaged 1.84 xG per game. Only Belgium, Brazil, England and Spain averaged more. Defensively they weren’t quite as strong, they gave up 1.17 expected goals per match. That was pretty average for the tournament, 15th give or take a rounding error. Put it all together and you get the sixth best xG difference in the tournament. Hard not to look at just that numbers and come to a very simple conclusion. If the team with the sixth best xG difference doesn’t make the last 16 teams there’s nothing much to be done. Bad luck happens, shrug your shoulders, go get 'em next time.

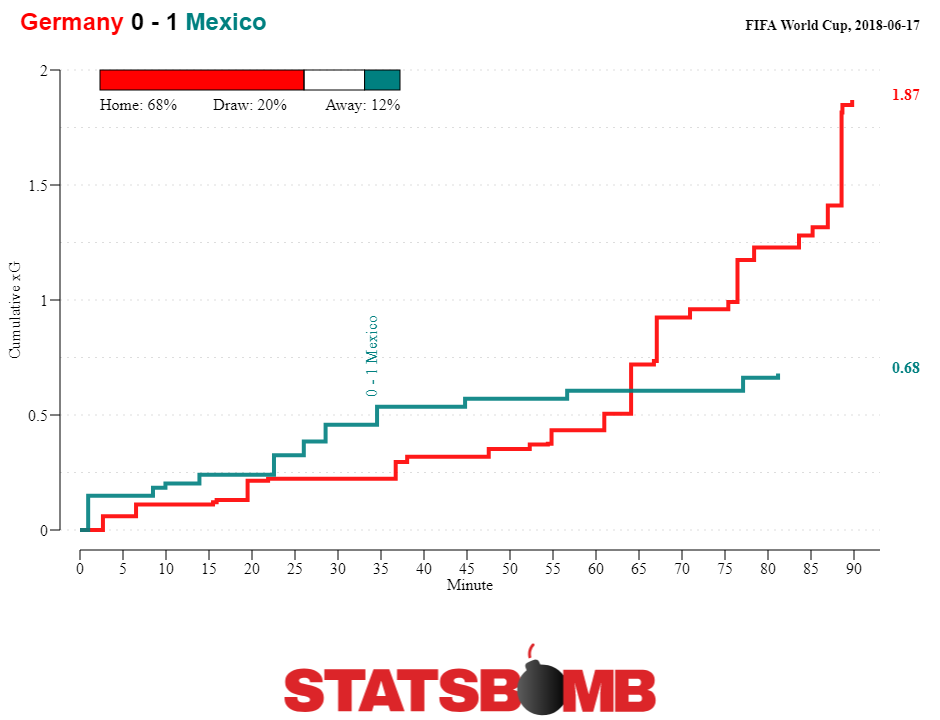

This, of course, would be an incredibly incomplete analysis. Let’s take a look at the games individually. Here’s the Mexico match which started it all off.

Two important things to note. When the game was even, Germany trailed from an xG perspective before they conceded and started trailing from an actual goal perspective. The bulk of their xG accumulated as they were chasing the match, ultimately unsuccessfully.

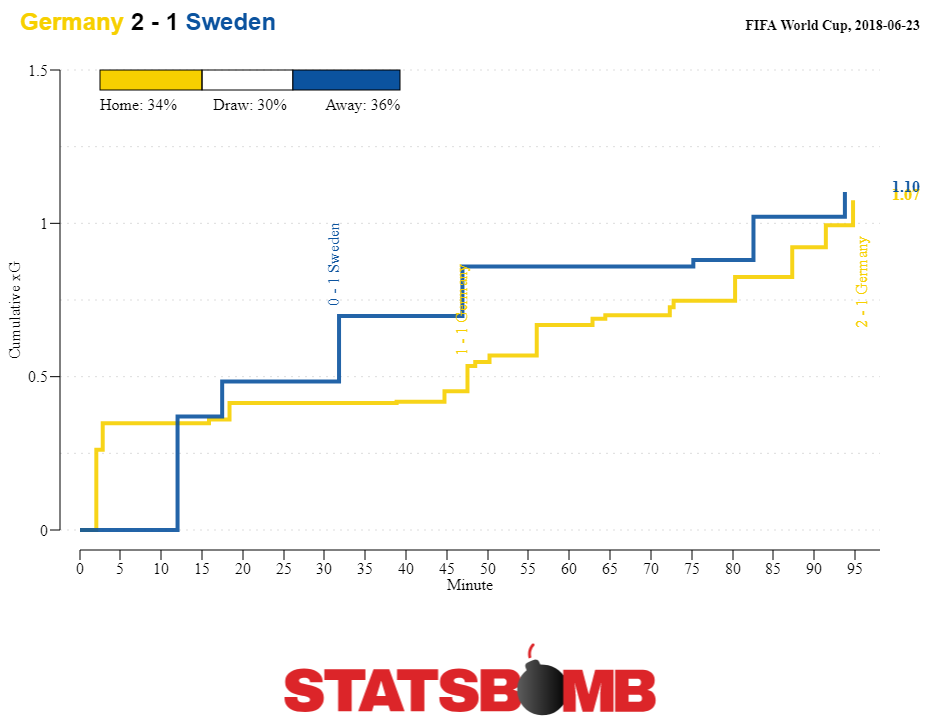

And, hey, what do you know, they same thing happened in their second match

Germany were not only chasing the match, but chasing their survival in the tournament and ultimately they snuck ahead thanks to all that pressure, and an amazing set piece strike from Toni Kroos.

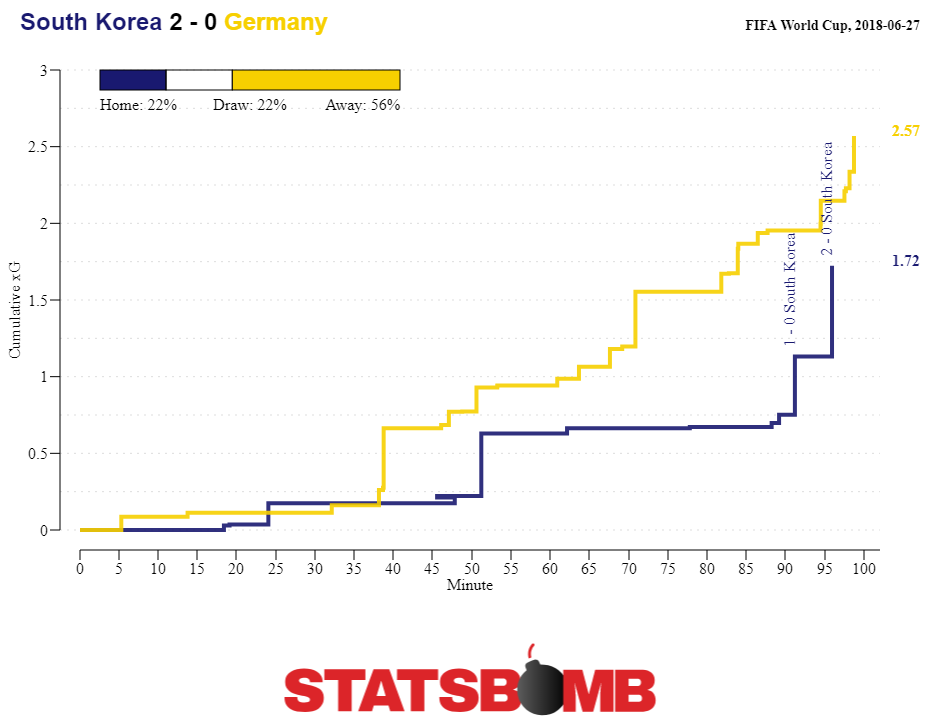

Match three is a bit of an eye of the beholder situation, and also demonstrates the limits of game state analysis in a tournament structure. Germany needed to win to advance, they started the match accordingly. As the match progressed they were increasingly (correctly) playing tactically as if they were down a goal.

And, of course, they kept missing. It’s certainly reasonable to look at the entire match and understand that Germany were unlucky not to score, but also that if they had scored earlier, their xG total would likely have ended up lower as they switched modes to preserve their lead.

Imagine a world where Germany came out and scored against South Korea in the first minute. It’s obviously impossible to know exactly how the rest of the game would play out but, at a minimum it’s hard to imagine that protecting a lead with advancement on the line, two forwards, Mario Gomez and Thomas Mueller would have come on for two midfielders in Sami Khedira and Leon Goretzka. Of course, the flip side is also true, if Germany weren’t ramping up the pressure and desperately chasing the game, they certainly wouldn’t have been so wide open, like Manuel Neuer in midfield leaving an empty net wide open, in the dying minutes of the match.

Small sample size isn’t just a problem when it comes to the difference between goals and xG, it’s also a problem when it comes to what xG says about teams themselves. It takes only a passing understanding of xG to look at Germany and correctly point out that they were unlucky not to score more. But, it’s also true that if they had not been unlucky, then on the attacking end their xG would have been more modest.

Three games is only three games, and it can only tell us so much about at team. In the same way that goal scored and conceded don’t tell us the whole story and there aren’t enough matches to even out the whims of the finishing gods, so too there aren’t enough matches to get past how the whims of the finishing gods can influence xG. We don’t know what Germany’s xG totals would have looked like if they hadn’t spent so much time chasing matches. But, what we do know is that in two games, against two teams they were supposed to be better than, they played roughly equally until falling behind.

Over the course of a season, of course, these things even themselves out. Sometimes a team will chase a handful of games in a row, and sometimes they’ll be chased. Sometimes they’ll get exceptionally hot or exceptionally cold for a match or two or six, and that will impact their xG totals, but eventually, the finishing evens out, and so does the xG. Not over three matches though, and especially not over three matches when a team spent one of them chasing the match from kick-off.

There are two separate ways that xG is predictive. We talk a lot about the first, that it's better at predicting future goals than just about anything else out there. But, there’s a second factor as well, and that’s that xG is very predictive of itself. Generally speaking, teams find their xG levels fairly quickly and those levels remain fairly stable going forward. That’s why the metric can underpin predictive models. But, even if xG is a fairly reliable fairly quickly, it’s not settled after only three games. And even if it was, outliers remain, and part of the task of doing analysis involves looking at outliers and evaluating whether there’s any reason for their outlier status…like say spending an entire game running up the xG score specifically because there’s no actual scoring going on.

Ultimately, it’s difficult to say anything definitive about Germany in just three games. We can’t say for sure whether a more normal slate of games would have served to increase or decrease their xG difference, but it certainly could have changed it. Over three games, looking at xG without the context of what happened will often lead to getting the wrong impression. Statistical tools are great, but the smaller the sample size the more they need context. And the World Cup is an absolutely tiny sample size.