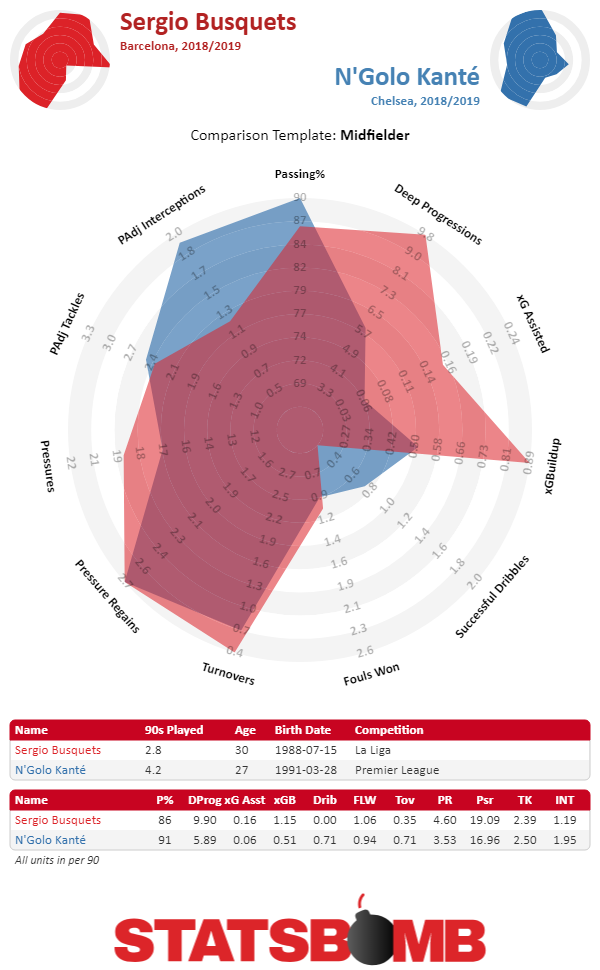

It’s been a while since the last StatsBomb mailbag. Summer’s over, the transfer window is closed and the domestic season is in full swing. Let’s answer some questions shall we? https://twitter.com/oldfashionedthe/status/1040512138396278784 Using defensive stats is hard. When profiling non-goal scoring players there are basically two different things you’re trying to do. You’re both trying to figure out what they do, and then to figure out how good they are at it. That’s why you don’t just look at one statistic, you look at lots of statistics. Which is why (among other reasons), we use radars. So, to take Kante and Busquets for example. They’re both nominally defensive midfielders. They’re both excellent. They also do very different things in very different contexts. Stats pick up on that though. They both have giant sized, but different looking, radars.  When you collect enough data, you can measure lots of different things. And, the further removed from goal scoring a player’s task is, the more varieties of skills they can use to accomplish their role on the field. The best players, and the best teams, marry skills to roles in a symbiotic way that makes everybody look great. As to the broader question of whether high defensive stats always mean that a player is good, the short answer there is no. Simple stats can be misleading in any number of ways, and part of the job of analytics is to account for that. Often times players with large numbers of interceptions and tackles aren’t particularly good, they just play on particularly bad teams that have to do a lot of defending. If your team is in possession of the ball, you can’t make a defensive action. That’s why we adjust defensive statistics for possession. It’s an easy way to further isolate exactly how often a player is making defensive actions in the context of how often they might have a chance to do so. Of course, the complications don’t stop there. Isolating a player’s impact from their teammates is difficult. Figuring out how players stop attackers without doing things that might qualify as a defensive action is important. For example, how do we measure a player being skilled at closing down passing lanes and forcing lateral passes? It’s a challenge. As always, the best way to think about statistics is as a tool to use to ask better questions, not as an ultimate answer. So, can the same stats tell us that both Busquets and Kante are good? Sure, if you’re looking at a broad enough, and smart enough, range of stats. But that’s only the beginning. https://twitter.com/RealJohnWolff/status/1040338249749688320 The thing about running a soccer club is that it’s hard. Think about the practical way that statistical based innovation in sport has to happen. I can be sure that something is true. I then have to convince people within a soccer club, usually fairly high up the organizational food chain that it’s true. They then have to pass marching orders down to practical level staff, management and coaches to act on that true thing. Those coaches then have to alter the behavior of the players on the pitch. That’s a lot of steps. There are tons of places things can go wrong, messages can get lost, implementation can break down, and that’s when everybody is on the same page philosophically about the breakthrough. Imagine what it’s like when there’s resistance. A relatively simple example of this is shot selection of course. The math is pretty conclusive on this one. It’s a much better decision for a player who’s around 35 yards out from goal to try a risky pass into the box than to take a whack at goal. Even if the pass comes off an extremely low percentage of the time. It can take some work to get people to buy into that idea, but it can be done. I know analysts who have actually had the coaching staff try and score from 35 yards repeatedly to drive the point home, or who have collated every single shot a player took from deep and made them sit and watch it in a row, just to drive the relative likelihoods home. But, even then, translating that knowledge into real action on the field takes work. It takes training. Often times there are years of instincts to be unlearned. Players have to learn to identify better situations, coaches have to learn to structure their team in ways to create those situations. It’s not just flipping a switch. I don’t want to discount the idea that sometimes analysts pick up on things we see as obvious and then those things get ignored. This month in the media there was some mild consternation over Liverpool hiring a throw-in coach. That’s something analysts (certainly the ones at StatsBomb anyway) talk about all the time as an easy, discrete, phase of the game in which some basic planning and coaching can convey at least a small edge. The fact that this might be mocked is indicative of those doing the mocking being insistent on shooting themselves in the foot out of spite. But, obvious examples aside, I think often times we’re all too quick to downplay the very real challenges of doing something new. Even when everybody agrees on an innovation, that doesn’t mean it automatically happens. https://twitter.com/sammcbride19/status/1040335244006760448 Yes. Much too early. Let’s at least wait until teams are playing twice a week before we write off players who were brought in, in large part, to improve the depth of a team. https://twitter.com/Tacticalfouling/status/1040366662523019265 I’ve written about the current Harry Kane struggles here before. His numbers are certainly down, and they have been since he injured his anklelate last March. Aside from the obvious implications for Spurs, the Kane situation is an interesting example of the ways in which sports challenges analytics to work with very little data. The reality is that from a numbers perspective you can’t say anything remotely definitive about Kane in a sample size that’s still well under 1000 minutes, spread out over the course of six months (not counting international play, because it’s tricky figuring out how to count international play). The question is, does the fact that you can’t say anything definitive mean you shouldn’t say anything at all? Because, realistically speaking, you very rarely if ever have the luxury of waiting until you have enough data to be sure about something in sports before you make a decision about it. To be nerdy about it, we should be Bayesian and constantly adjusting our priors. I expected Kane to be fine this season, I expected him to perform roughly at the level he performed at last season, although maybe slightly worse given just how supernova he went last year. I’ve now been shown some evidence to the contrary. That evidence is certainly not definitive. He may end up being totally fine, but so far he has been worse. I still don’t know why he’s been worse so far this season than last. Is it the lingering impact of his injury? Have tactical changes on Spurs shifted the way he’s played? Is it a combination of both? Did Kane’s injury down the stretch last year cause Spurs to evolve him into a slightly more reserved role, a role he’s still inhabiting despite being healthy? These are all possibilities. So is the possibility that there’s absolutely nothing wrong, and that Kane is going to take 20 shots over the next three weeks and score four goals. The point of all those words which could have just been a shrug emoji is to say that we shouldn’t really be asking the question is Harry Kane ok, but rather, how likely is it that Harry Kane is ok? And the answer to that question has certainly decreased as the weeks have gone on. https://twitter.com/FootEnStats/status/1040336361310576641 So much! Guys and gals we are so excited about all the stuff that we’re doing here and honestly we still feel like we haven’t scratched the surface of what we can do with all the data we’re collecting. We’ve teased goalkeeper stuff in the past, and that’s going to be rolling out in a more robust way. We have so much more work to do with pressure, and what it means, and how it influences games. Not just on the defensive side of the ball, but on the attacking side of the ball as well. We’re rebuilding passing models to more accurately reflect the real world. There’s also a super secret project or two floating around, because of course there is. Generally speaking most of the awesome stuff we do gets rolled out internally and for clients, and then slowly makes its way into the work we do publicly on the site. So, stick around we’ve got lots of cool stuff on the way.

When you collect enough data, you can measure lots of different things. And, the further removed from goal scoring a player’s task is, the more varieties of skills they can use to accomplish their role on the field. The best players, and the best teams, marry skills to roles in a symbiotic way that makes everybody look great. As to the broader question of whether high defensive stats always mean that a player is good, the short answer there is no. Simple stats can be misleading in any number of ways, and part of the job of analytics is to account for that. Often times players with large numbers of interceptions and tackles aren’t particularly good, they just play on particularly bad teams that have to do a lot of defending. If your team is in possession of the ball, you can’t make a defensive action. That’s why we adjust defensive statistics for possession. It’s an easy way to further isolate exactly how often a player is making defensive actions in the context of how often they might have a chance to do so. Of course, the complications don’t stop there. Isolating a player’s impact from their teammates is difficult. Figuring out how players stop attackers without doing things that might qualify as a defensive action is important. For example, how do we measure a player being skilled at closing down passing lanes and forcing lateral passes? It’s a challenge. As always, the best way to think about statistics is as a tool to use to ask better questions, not as an ultimate answer. So, can the same stats tell us that both Busquets and Kante are good? Sure, if you’re looking at a broad enough, and smart enough, range of stats. But that’s only the beginning. https://twitter.com/RealJohnWolff/status/1040338249749688320 The thing about running a soccer club is that it’s hard. Think about the practical way that statistical based innovation in sport has to happen. I can be sure that something is true. I then have to convince people within a soccer club, usually fairly high up the organizational food chain that it’s true. They then have to pass marching orders down to practical level staff, management and coaches to act on that true thing. Those coaches then have to alter the behavior of the players on the pitch. That’s a lot of steps. There are tons of places things can go wrong, messages can get lost, implementation can break down, and that’s when everybody is on the same page philosophically about the breakthrough. Imagine what it’s like when there’s resistance. A relatively simple example of this is shot selection of course. The math is pretty conclusive on this one. It’s a much better decision for a player who’s around 35 yards out from goal to try a risky pass into the box than to take a whack at goal. Even if the pass comes off an extremely low percentage of the time. It can take some work to get people to buy into that idea, but it can be done. I know analysts who have actually had the coaching staff try and score from 35 yards repeatedly to drive the point home, or who have collated every single shot a player took from deep and made them sit and watch it in a row, just to drive the relative likelihoods home. But, even then, translating that knowledge into real action on the field takes work. It takes training. Often times there are years of instincts to be unlearned. Players have to learn to identify better situations, coaches have to learn to structure their team in ways to create those situations. It’s not just flipping a switch. I don’t want to discount the idea that sometimes analysts pick up on things we see as obvious and then those things get ignored. This month in the media there was some mild consternation over Liverpool hiring a throw-in coach. That’s something analysts (certainly the ones at StatsBomb anyway) talk about all the time as an easy, discrete, phase of the game in which some basic planning and coaching can convey at least a small edge. The fact that this might be mocked is indicative of those doing the mocking being insistent on shooting themselves in the foot out of spite. But, obvious examples aside, I think often times we’re all too quick to downplay the very real challenges of doing something new. Even when everybody agrees on an innovation, that doesn’t mean it automatically happens. https://twitter.com/sammcbride19/status/1040335244006760448 Yes. Much too early. Let’s at least wait until teams are playing twice a week before we write off players who were brought in, in large part, to improve the depth of a team. https://twitter.com/Tacticalfouling/status/1040366662523019265 I’ve written about the current Harry Kane struggles here before. His numbers are certainly down, and they have been since he injured his anklelate last March. Aside from the obvious implications for Spurs, the Kane situation is an interesting example of the ways in which sports challenges analytics to work with very little data. The reality is that from a numbers perspective you can’t say anything remotely definitive about Kane in a sample size that’s still well under 1000 minutes, spread out over the course of six months (not counting international play, because it’s tricky figuring out how to count international play). The question is, does the fact that you can’t say anything definitive mean you shouldn’t say anything at all? Because, realistically speaking, you very rarely if ever have the luxury of waiting until you have enough data to be sure about something in sports before you make a decision about it. To be nerdy about it, we should be Bayesian and constantly adjusting our priors. I expected Kane to be fine this season, I expected him to perform roughly at the level he performed at last season, although maybe slightly worse given just how supernova he went last year. I’ve now been shown some evidence to the contrary. That evidence is certainly not definitive. He may end up being totally fine, but so far he has been worse. I still don’t know why he’s been worse so far this season than last. Is it the lingering impact of his injury? Have tactical changes on Spurs shifted the way he’s played? Is it a combination of both? Did Kane’s injury down the stretch last year cause Spurs to evolve him into a slightly more reserved role, a role he’s still inhabiting despite being healthy? These are all possibilities. So is the possibility that there’s absolutely nothing wrong, and that Kane is going to take 20 shots over the next three weeks and score four goals. The point of all those words which could have just been a shrug emoji is to say that we shouldn’t really be asking the question is Harry Kane ok, but rather, how likely is it that Harry Kane is ok? And the answer to that question has certainly decreased as the weeks have gone on. https://twitter.com/FootEnStats/status/1040336361310576641 So much! Guys and gals we are so excited about all the stuff that we’re doing here and honestly we still feel like we haven’t scratched the surface of what we can do with all the data we’re collecting. We’ve teased goalkeeper stuff in the past, and that’s going to be rolling out in a more robust way. We have so much more work to do with pressure, and what it means, and how it influences games. Not just on the defensive side of the ball, but on the attacking side of the ball as well. We’re rebuilding passing models to more accurately reflect the real world. There’s also a super secret project or two floating around, because of course there is. Generally speaking most of the awesome stuff we do gets rolled out internally and for clients, and then slowly makes its way into the work we do publicly on the site. So, stick around we’ve got lots of cool stuff on the way.

Month: September 2018

Previewing Liverpool's Trip to Tottenham

There’s no doubt that Tottenham against Liverpool is the Premier League game of the weekend, but that doesn’t mean previous encounters haven’t felt somewhat flat. Since Jurgen Klopp arrived at Liverpool, he has faced Mauricio Pochettino’s Spurs six times in the league. Both sides have won one game fairly convincingly, while the other four have been drab, uninspiring draws. It’s as though both managers’ high pressing systems have a tendency to cancel out and create little in the way of goalmouth action. Even the most recent 2-2 draw was a very unentertaining affair for the first 75 minutes or so, before Victor Wanyama scored a screamer and Spurs won two penalties. The knowledge that both sides have had difficulties breaking down the other in the past may inform some of the choices the managers make here, such as:

Will Spurs Press High?

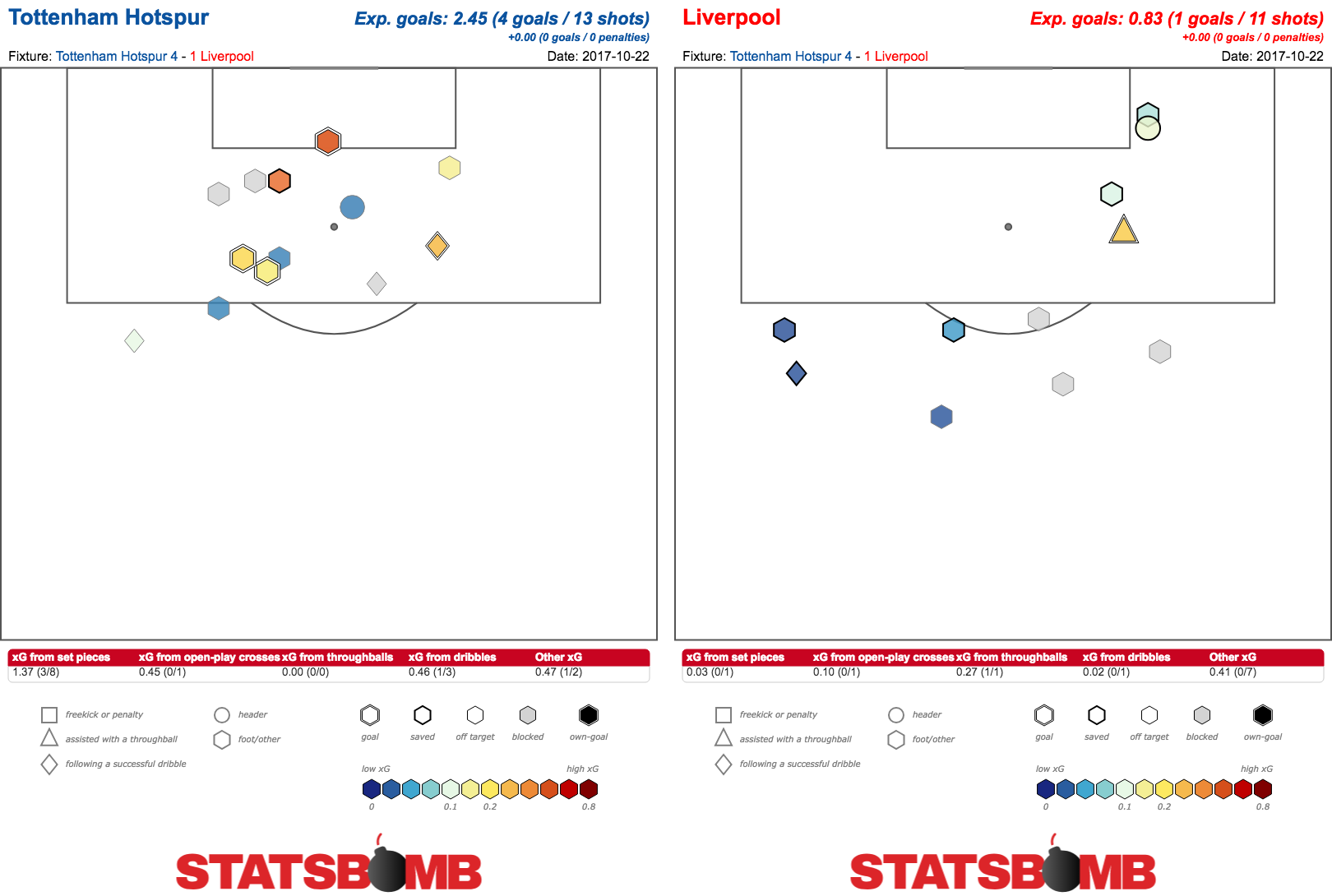

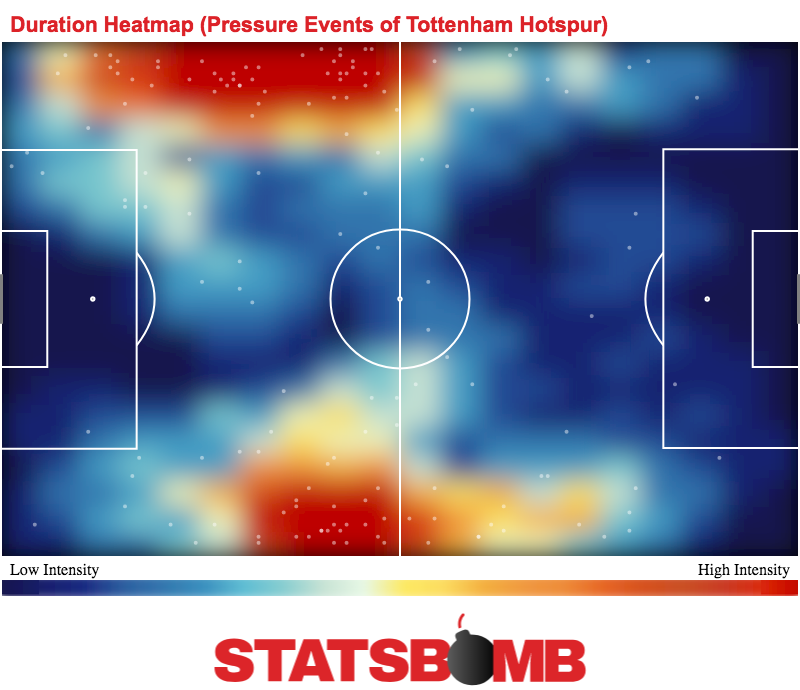

Pochettino’s only decisive victory against Klopp’s Liverpool came at Wembley last October, in which his side played on the counter to tear apart Liverpool and record a 4-1 win. Liverpool commande 64% possession and a comparable shot total to Spurs, but one side was able to generate much higher quality chances than the other.  The way they did it was in a drastic shift from their usual plan. As shown from StatsBomb’s pressure numbers, they barely pressed in the opposition half at all.

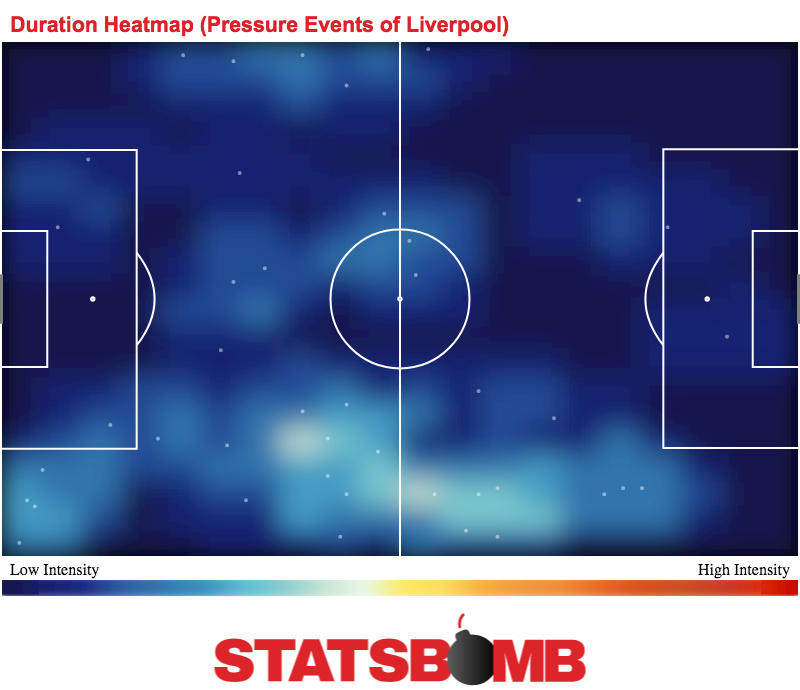

The way they did it was in a drastic shift from their usual plan. As shown from StatsBomb’s pressure numbers, they barely pressed in the opposition half at all.  It was this defensive tactic that allowed them to hit Liverpool, who left a lot of space in behind, so effectively. In fact, they didn’t allow Klopp’s men almost any chances to press them at all.

It was this defensive tactic that allowed them to hit Liverpool, who left a lot of space in behind, so effectively. In fact, they didn’t allow Klopp’s men almost any chances to press them at all.  Liverpool did seem to wise up to this significantly in the return fixture the following February, and became much more compact themselves. As for Spurs, they haven’t exactly followed that path so far this season. On average they allow the opponent to make only 7.88 passes before making a defensive action; this is the fewest passes per defensive action in the league. Their high press rating (based on StatsBomb’s pressing data) is the third highest. Thus far in the season, this is not a side that has sat back. Whether Pochettino reverts to this strategy is perhaps the key unknown that Klopp will have to contend with.

Liverpool did seem to wise up to this significantly in the return fixture the following February, and became much more compact themselves. As for Spurs, they haven’t exactly followed that path so far this season. On average they allow the opponent to make only 7.88 passes before making a defensive action; this is the fewest passes per defensive action in the league. Their high press rating (based on StatsBomb’s pressing data) is the third highest. Thus far in the season, this is not a side that has sat back. Whether Pochettino reverts to this strategy is perhaps the key unknown that Klopp will have to contend with.

Who Starts in Midfield for Liverpool?

Unlike Spurs, who have adopted a range of different systems this season, Liverpool’s team largely picks itself at the moment. The formation will be 4-3-3. The attackers will be Sadio Mane, Mohamed Salah and Roberto Firmino. The back four will probably be Trent Alexander-Arnold, Joe Gomez, Virgil van Dijk and Andy Robertson, though there is an outside chance of Nathaniel Clyne or Joel Matip being rotated in. The only serious question is in midfield. For the first three games of the season, Gini Wijnaldum started as the deepest midfielder, a role he is not accustomed to, with Naby Keita and James Milner in front. Wijnaldum is a slightly strange if not entirely ineffective fit for the role. His 2.53 possession-adjusted tackles and interceptions per 90 minutes this season are well below what we’d expect from a defensive midfielder at a top side, and while it has not yet led to conceding significant chances, a minor flaw for Liverpool so far has been that teams have been able to move the ball through the centre of midfield without a lot of difficulty. Jordan Henderson came into the side against Leicester, with Wijnaldum moving further forward and Keita rested (though one imagines he will return to the side) presumably to better deal with this, but the result was not hugely different to before. Liverpool still allowed Leicester a number of decent counter-attacking opportunities, though it again only led to 0.82 expected goals. Expensive summer signing and specialist holding midfielder Fabinho remains unused, with his absence from Liverpool over the international break making it possible this will remain the case for another game. The most likely outcome is that Henderson starts, though there does not currently look to be an ideal option to offer Liverpool the defensive control from midfield the side craves.

Can Spurs Fix the Right Side, or can Liverpool Exploit It?

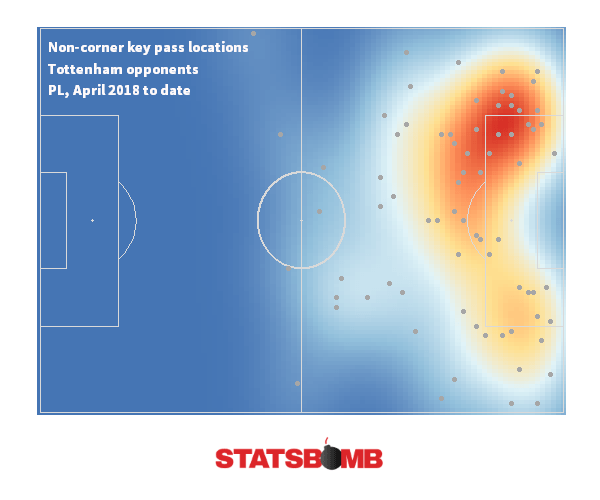

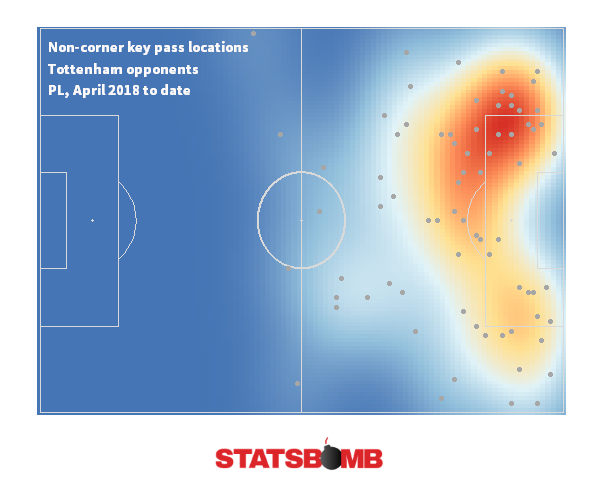

Spurs have a defensive issue. As James Yorke has written for StatsBomb, “across the last ten to fifteen fixtures, Tottenham’s expected goal production has been roughly equal in attack and defence. The attack side has been largely good, the defence has not”. Yorke points out that this issue has been specifically one down Spurs’ right side, with a large number of the chances they concede being created in this area:  Usual right back Kieran Trippier appears to be particularly culpable, and thus a change may be wise. If there’s one thing associated with Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool, it is pace, with Mane on the left flank a key part of that. Serge Aurier, a player not without his flaws but certainly someone much quicker than Trippier, could make a return to the starting eleven to plug this hole. Conversely, it is something Liverpool may well look to exploit. Mane has started the season in excellent form, with 4 goals in 360 minutes. On the same side, Robertson is currently assisting 0.36 expected goals per 90, an outrageous figure for a full back, while star creative midfield force Keita has had a tendency to drift left in his appearances so far. If Spurs don’t find a way to get this locked down, it could easily be something that Liverpool create a lot of chances from.

Usual right back Kieran Trippier appears to be particularly culpable, and thus a change may be wise. If there’s one thing associated with Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool, it is pace, with Mane on the left flank a key part of that. Serge Aurier, a player not without his flaws but certainly someone much quicker than Trippier, could make a return to the starting eleven to plug this hole. Conversely, it is something Liverpool may well look to exploit. Mane has started the season in excellent form, with 4 goals in 360 minutes. On the same side, Robertson is currently assisting 0.36 expected goals per 90, an outrageous figure for a full back, while star creative midfield force Keita has had a tendency to drift left in his appearances so far. If Spurs don’t find a way to get this locked down, it could easily be something that Liverpool create a lot of chances from.

Are Liverpool Now Counter Attack-Proof?

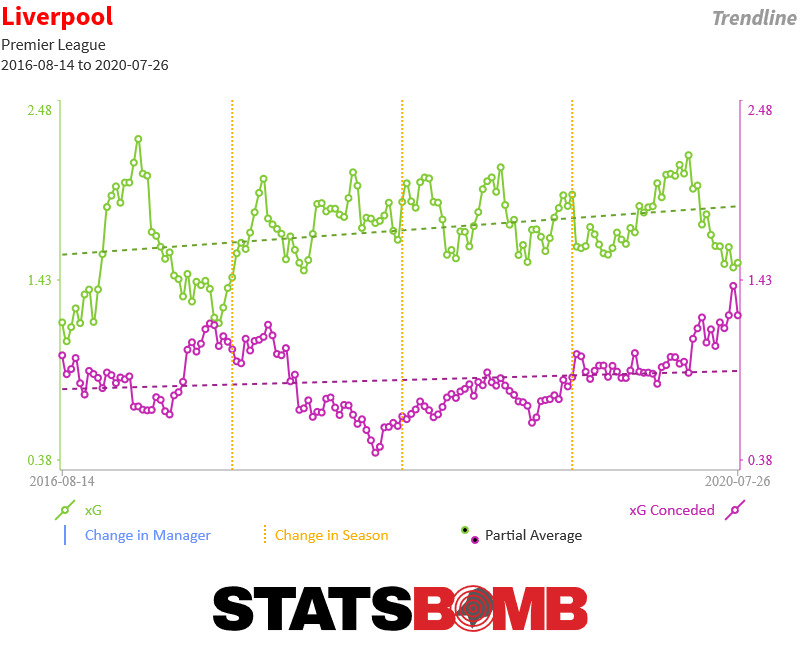

In the aforementioned edition of this fixture last season, Spurs picked Liverpool apart on the counter. While it was somewhat surprising for Spurs to switch to that approach, there was nothing surprising about it being effective against Liverpool. The consensus among pretty much everyone was that Liverpool were hilariously open at the back, had a tendency to switch off at these moments and, as the harshest critics claimed, “couldn’t defend”. A quick look at the team’s rolling xG conceded since that game shows that things have changed a fair amount.  Spurs created 2.45 non-penalty expected goals against Liverpool that day. In the eleven months since, there hasn’t been a single Premier League game in which Liverpool have conceded more than 2. This is a team that “can defend”. What’s interesting is that this has been done without a huge change in strategy. Liverpool still play in largely the same way, and still attack in the same way, just without the defensive issues that plagued the side before. The arrival of Van Dijk was widely heralded as a major component in this shift, as was the signing of Robertson and the emergence of youngsters Gomez and Alexander-Arnold. Of this first choice back four, only one featured at Wembley last October. The feeling among many was that the individuals couldn’t possibly be that bad and clearly there was a systemic problem, but maybe it simply was the players not being up to task. Perhaps more work on the training ground led to the team finally grasping what was being asked of them. We may never know. If Spurs attempt the same counter-attacking strategy that worked so well last year, we should have a fairly interesting test case around how much this defence has actually improved.

Spurs created 2.45 non-penalty expected goals against Liverpool that day. In the eleven months since, there hasn’t been a single Premier League game in which Liverpool have conceded more than 2. This is a team that “can defend”. What’s interesting is that this has been done without a huge change in strategy. Liverpool still play in largely the same way, and still attack in the same way, just without the defensive issues that plagued the side before. The arrival of Van Dijk was widely heralded as a major component in this shift, as was the signing of Robertson and the emergence of youngsters Gomez and Alexander-Arnold. Of this first choice back four, only one featured at Wembley last October. The feeling among many was that the individuals couldn’t possibly be that bad and clearly there was a systemic problem, but maybe it simply was the players not being up to task. Perhaps more work on the training ground led to the team finally grasping what was being asked of them. We may never know. If Spurs attempt the same counter-attacking strategy that worked so well last year, we should have a fairly interesting test case around how much this defence has actually improved.

What Formation Will Pochettino Use?

In their opening game of the season, Spurs were broadly in a 4-2-3-1 shape, with Dele Alli and Lucas Moura playing narrow in the wide roles. For the following game against Fulham, they played a 3-5-2 shape, switching to three centre backs and having Alli and Christian Eriksen in “free eight” roles advanced of Eric Dier, with Lucas Moura as a support striker alongside Harry Kane. Against Manchester United, Pochettino returned to the back four, and initially played a diamond in midfield (with Mousa Dembele as the holding midfielder) before adjusting in game to a sort of 4-2-2-2, with Eriksen and Alli behind the front two of Moura and Kane. For the most recent game against Watford, Pochettino changed it back to the 3-5-2 shape, with the only personnel change from the last time it was rolled out against Fulham being Dembele for Dier. It has become something of a guessing game as to how the manager will set up his side, perhaps just as a genuine tailored strategy for each opponent, or perhaps as he finds different solutions to fix his side’s defensive issues. If it is the latter, the back three may be tempting as a way to address Trippier’s aforementioned struggles. If it is the former, however, this is less likely considering Liverpool’s penchant to crack back threes open with the pace and movement of Mane, Salah and Firmino. A back four may be more likely, especially considering the troubles the team had against Watford. The absence of Alli and return of Son Heung-min, who is unlikely to be able to play such a free eight role, is another thing Pochettino will have to contend with, perhaps making the 3-5-2 even less likely.

Will We Actually Get an Entertaining Game?

As discussed at the start of the article, these contests have not typically been a good watch for the neutral. On the few occasions that they haven’t been drab draws, we’ve instead had one sided contests. There are some reasons for optimism, though. Both sides have had some midfield control issues, with none of Gini Wijnaldum, Jordan Henderson, Eric Dier or Mousa Dembele performing the holding midfield role at a high level this season. Spurs’ right sided defensive problems persist, while Liverpool look particularly dangerous on that side. Perhaps we might finally get a game worthy of these two excellent sides.

StatsBomb Release Free FIFA World Cup Data

StatsBomb announces the release of the 2018 Men's World Cup on our industry-leading event data spec StatsBomb Data, for free. From the beginning, StatsBomb has been about fostering an analytics community dedicated to learning more about the game of football.

One of the major issues for new potential analysts is difficulty in obtaining high quality data at scale. The same problem exists for teachers who are responsible for training new data scientists. The World Cup data, along with our continuing release of women's football data, helps address this problem directly.

This data is the same industry-leading, professional spec that we collect for all leagues and includes a level of detail you won’t find from any other data provider, including:

- location of players on the pitch in any shot, including the position and actions of the Goalkeeper

- detailed information on ALL players applying defensive pressure on a player in possession – including how long the pressure lasted

- which foot a player passes with, and many more minor enhancements

Like the free women's football data we started producing this summer, this data will be available via our Resource Centre for non-commercial use. This is also the same data used by John Burn-Murdoch and the outstanding data team at the Financial Times while the World Cup was in progress.

NEW for our final @FT World Cup stats briefing: In Pogba and Kanté, France have the bestex player at progressing the ball, and the best at winning it https://t.co/yPXjJXtVnm #FRACRO Here's how the dominant duo compare to the best of the rest: pic.twitter.com/l3rmxHECmW

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) July 13, 2018

You are actively encouraged to write about your analysis publicly and share it on social media.

Our only request is that you credit StatsBomb as your data source and where possible include our logo.

The analysis at the FT and on our own site set a high bar for World Cup coverage this summer, but now fans everywhere have data available to match those performances or even better them.

We heartily invite you to try.

Best of luck,

The Entire StatsBomb Team

The Not Altogether Unserious Case For a Managerial Transfer Window

Does the football season really begin before clubs start playing managerial musical chairs? The gap between those two start dates is minimal. Notts County fired Kevin Nolan, who led them to League Two’s playoffs, five matches into the season. After two matches (three if you’re generous), Jose Mourinho and Manchester United began spinning their inevitable uncoupling. West Ham saw the last few season’s tensions return before the first international break of the season. Sam Allardyce’s name has already been connected to just about any footballing entity with “club” in its name. This is madness. Judging a manager on the first few results of a season puts undue emphasis on finishing luck and scheduling. That should not be enough to sway a club’s managerial assessment l — either from what they saw last year or during the hiring process for a new hire. This form of madness is hardly novel. Many clubs now do little more than, well, bounce from one managerial bounce to the next. While this strategy is sometimes accompanied by promotion or survival (causality is too often inferred here), it also results in the misallocation of funds, the squandering of player potential, and miserable football. It doesn’t have to be this way. Football authorities could — but won’t, if we’re being honest — do something about this by implementing a cognate to the player transfer window. For the sake of simplicity, let’s call it the Managerial Replacement Window. The basic idea here is simple: Clubs can only sign new managers in prescribed periods. Outside of those windows, clubs only promote their existing employees to the role of manager. For the sake of argument, let’s say the Managerial Replacement Window would be open for much of the summer and the first twenty days of December. This particular configuration would allow managers to bring in new players and be able to use the pre-season and, in applicable leagues, the mid-season break to implement their ideas. For good measure, this configuration roughly bifurcates most club seasons. Consider the player transfer window. Its main benefit, the Premier League’s own website explained in 2017, is “that it enables clubs and managers to plan for a set period of time, knowing the players they have at their disposal.” That is somewhat self-serving, but the transfer window does serve as a bulwark against the chaos of players coming and going at all times. The vision of planning the Premier League describes is largely at odds with the reality of managerial hiring. On average, managers now last little more than a year. They come and go throughout the season. Some clubs have structures to ensure a consistent vision amid managerial changes, but it’s still relatively common for new managers to be sorting through players from five previous short-term visions. There can be no set planning of the sort the player transfer window envisions without the barest modicum of managerial stability. The Managerial Replacement Window puts some mild limits on this madness. It insists that managers come in before transfer windows and remain for the months that follow. While there’s only so much that can be done to save a self-destructive club from itself — in England, the only real regulation is that owners must pass the “fit-and-proper-person test” — this limits the chaos of relegation-threatened clubs frantically shuffling through players and managers for a few years before falling off a cliff, Road Runner-style, as the incoherence of their assembled parts suddenly hits home. Stats Bomb editor Mike Goodman justifiably calls this the Sunderland Vortex. The vortex, beyond bad results, is an awful financial problem that causes players to be splurged upon only to be quickly dropped. This cycle would not fully be addressed through the Managerial Replacement Window, but the deliberate pacing of managerial changes would at least attenuate it. Limiting managerial changes to specific windows, more broadly, is an attempt to force a structured system for thinking about these moves on clubs. Before the summer window, they’d have to consider whether, based on the available months of information, they believe in the incumbent is up to the task. Dithering through the player transfer window and into the season would come at a much higher cost: You could be stuck with Gus Poyet for months. This wouldn’t necessarily lengthen managerial tenures. Instead of dithering, teams might just cut managers inside the windows. Yet this structured churn would at least force teams to make their cuts based on more than panic. Moreover, new hires would have a better chance to prove their merits. A few games is not enough time to disentangle structural problems from blips that’ll be solved by regression, yet that’s how long into the season before games currently become must-wins. In the name of fairness, it’s worth noting that managers sometimes prove themselves unfit for their jobs in very short periods of times. These cases tend to have more to do with temperament or process than results. A manager who offends all their players or picks starting XIs based on astrology, is manifestly not up to the task. Teams that currently fire such managers as quickly as possible are behaving reasonably. The logic of the player transfer window, mind you, is that teams should have to live with their mistakes. If Everton is dumb enough to sign Davy Klassen, every team should get to face him or the reserve who takes his place. If only the spirit of consistency, why shouldn’t this apply to managers? If a team is dumb enough to hire Tim Sherwood, every team should get to face him or the first-team coach forced to take his place until a proper replacement can be secured. Such consistency with how football currently works would at least be entertaining. Institutionalizing that sort of buyer’s remorse may sound like mean-spirited entertainment, but it’s really an effort to create a greater cost for teams that don’t think through their decisions. The Managerial Replacement Window is unlikely to be implemented. Outside of American sports, where mechanisms like the Stepien Rule seek to limit teams’ decision-making powers, teams can do as they wish with their money and assets. Without attaching greater costs to bad processes and decisions, though, it’s likely the current system of firing managers at inopportune times with questionable evidence will persist. Smart teams may avoid the Sunderland Vortex, but panic is a strong motivator. If we can’t have a Managerial Replacement Window, can we at least get a ban on hiring Tim Sherwood? Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Atletico Madrid's Slow Start

Atletico Madrid are off to a curiously slow start. It’s the rare year where there might be some cracks at the top of La Liga. The departure of Cristiano Ronaldo from Real Madrid means there’s a crack of daylight at the top of the table. But, three games in, the perennial favorites, Barcelona, and Ronaldo-less Madrid are perfect and Diego Simeone’s team has already dropped five points. Is there anything amiss with Atletico, or have their opening three games been the kind of fluke that the next 35 games will make everybody forget?

The most notable difference for Atleti so far this season, is that their defense simply hasn’t been up to their usual standards. Last year they were the best team in the league defensively. They only conceded 0.87 expected goals per game, one of only two teams, along with Getafe, under the one goal barrier. This year, they’re at 1.21. That’s a really big jump. It’s easy to see that the defense has performed relatively poorly, getting under the hood and figuring out why is important for figuring out whether it will continue.

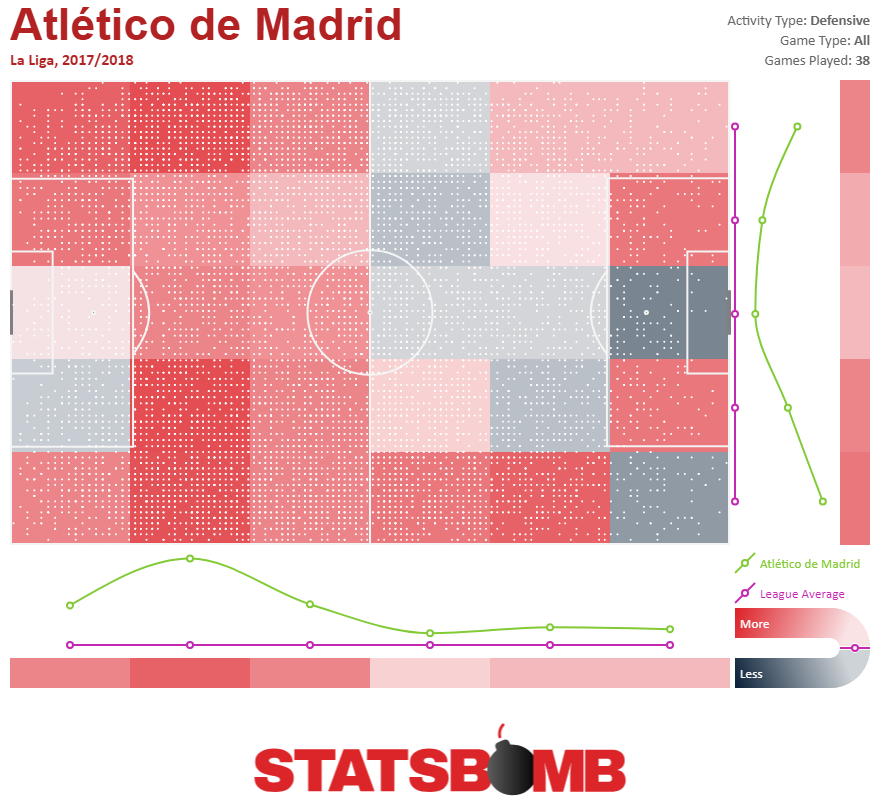

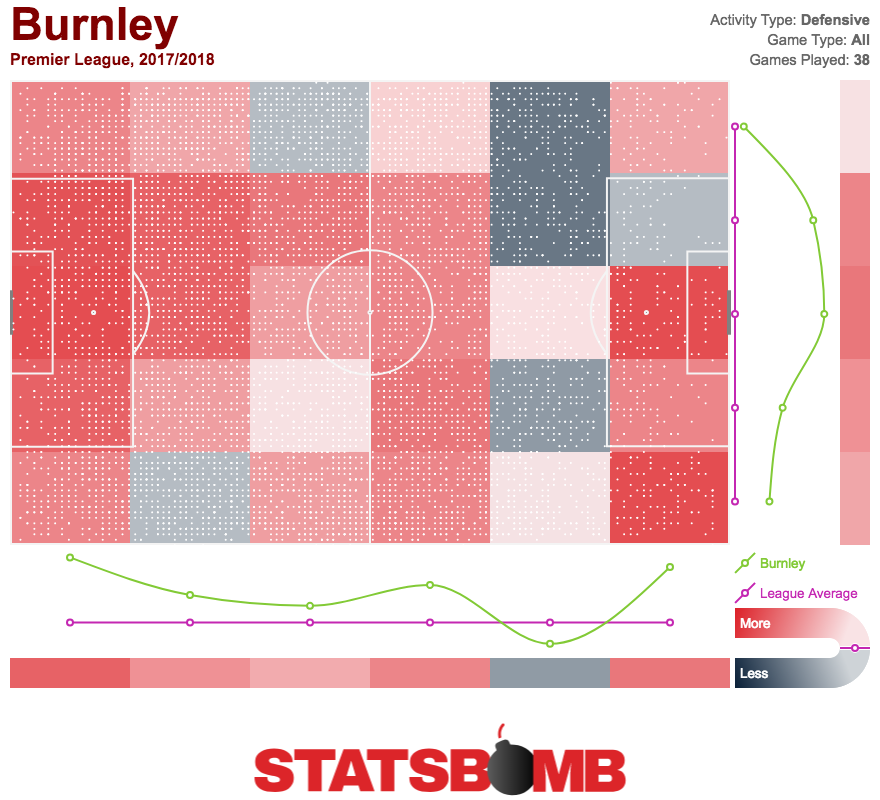

Traditionally Atletico have been happy to cede territory in their opponents half, but been extraordinarily aggressive in their own. Here’s what their defensive heat map looked like last season.

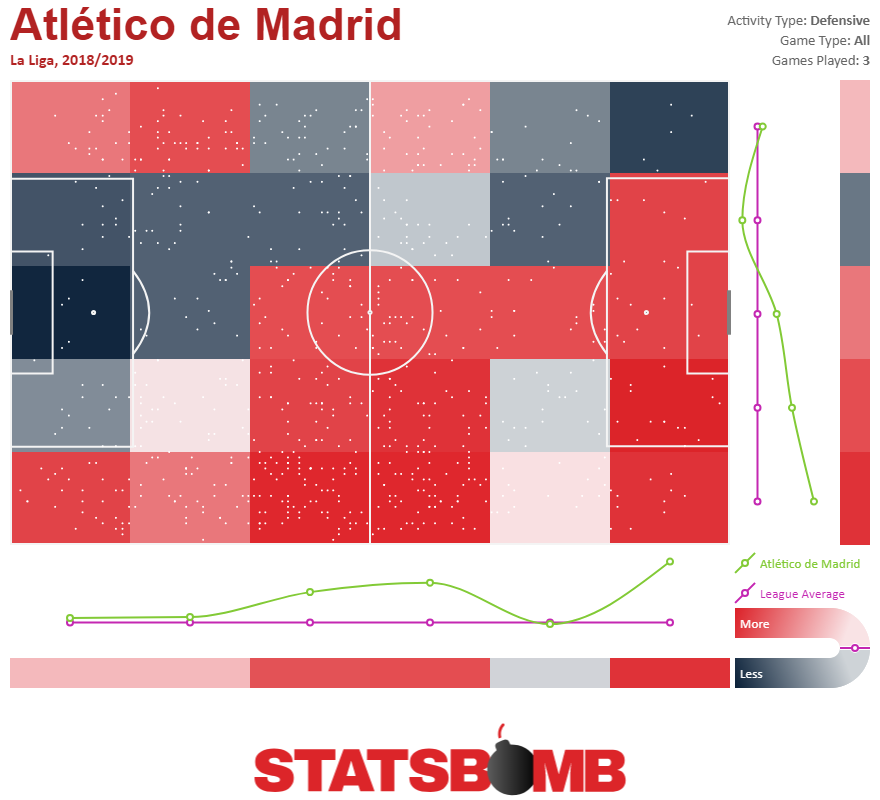

This year, well, so far that pressure map looks entirely different.

There are lots of reasons that might be. They’ve played an interesting set of opponents, going away to Valencia and drawing, before beating Rayo Vallecano at home and then going on the road (and playing 20 minutes down a man) to lose 2-0 to Celta Vigo. It’s certainly possible that some combination of tactical interplay is what’s driving the difference.

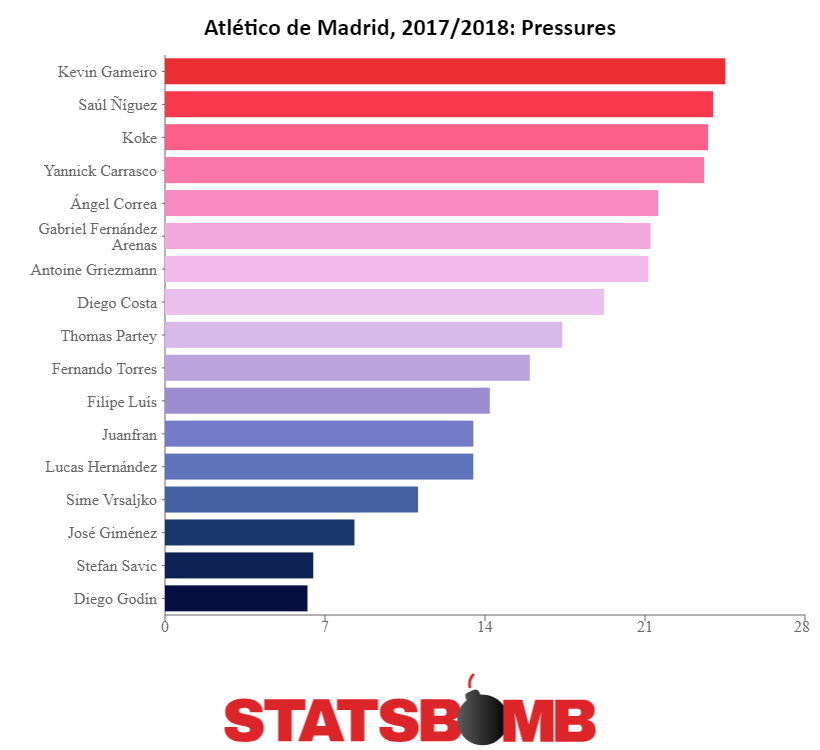

It’s also possible that Simeone is playing catch-up when it comes to indoctrinating parts of his new team defensively. Here are the players that led the team in ball pressures per 90 minutes last season (and played over 900 minutes).

It’s a peculiar system that Simeone runs. The team doesn’t press high up the field, but still asks the forwards and wingers do to a lot of defensive work, dropping into their own half and then harassing the ball. Often times one or both wingers are asked to pinch inside and serve as an extra midfielder while one of the forwards drops back to cover the wing. It’s how Simone can both nominally play a 4-4-2 system while also seeming to have bodies everywhere behind the ball.

Several of the players who were instrumental to that system are now gone. Four of the team’s ten most active players at pressuring the ball are no longer around. For the attackers that’s not a huge change. Kevin Gameiro, and Fernando Torres were both bench options by the end of last season, and Yannick Carrasco left last January for China, but in midfield, the loss of Gabi looms large. Yes, he was 35, and his legs weren’t what they were, but his expertise at holding the midfield together was real.

In three games so far this season, Simeone has deployed three different midfield pairings. Against Valencia, Koke and Saul Niguez started together. Against Rayo, Koke sat and Rodri came into the side to pair with Saul, and then during the debacle against Celta it was Saul and Thomas Partey. Three matches, three different partners for Saul. It’s possible Simeone is planning to mix and match all season long, customizing his midfield approach to his opponents. It’s also possible that he simply doesn’t know what his best midfield is yet. World Cup summers are short, and they cast long preparation shadows. Simeone is trying to work newcomers like Rodri and Thomas Lemar into the side. He is trying to do it despite Lemar, along with both starting forwards in Antoine Griezmann and Diego Costa, as well as Koke and Saul being gone for most of the summer on international duty. It’s certainly possible that the first three weeks are simply a symptom of everybody not quite knowing each other yet and a team that needs to work its way up to full speed.

But, Simeone needs to get them there, because the defense simply isn’t working as well as it’s supposed to. They’re conceding both more shots, and better shots than last year. Last year they conceded 11.87 shots per game and 0.08 expected goals per shot and this year that’s up to 12.33 and 0.10. The fact that both numbers have gone up suggests that rather than seeing a style change, we’re simply seeing a defense that isn’t executing at the high levels we’re accustomed to seeing from Simeone teams.

Atletico’s style also gives them a smaller margin for error. Their grind it out defensive approach means that often times even beating mediocre teams means lots of work. Last season, even while finishing second the team was ninth in expected goals scored per game with only 1.18. They only took 10.95 shots per game, only five teams took fewer. Even at the best of times Atletico make things difficult for themselves.

Of course, if anybody deserves the world’s faith when it comes to molding and shaping a defensive unit, it’s Simeone. He has repeatedly worked with shifting personnel to put together teams that dominate on the defensive side of the ball. There was a time when the midfield was patrolled by Gabi and Tiago. He managed to navigate Diego Costa leaving and then returning. This is a team that managed to move on from once talismanic winger Arda Turan seamlessly. Simeone has managed the same thing in the defensive line where Diego Godin is the only constant. Miranda left, Filipe Luis left and came back. Toby Alderweireld came and went. A cadre of young defenders took their places with Lucas Hernandez and Stefan Savic in particular stepping to the fore. Simeone is the constant on the sideline, the majority of the players on the pitch have changed over the years.

Atletico will probably be fine. Simeone will take the new pieces, integrate with the old ones, and put together a strong squad that will finish comfortably in the top four of La Liga. That doesn’t mean there’s nothing wrong at Atletico right now. There is. It just means that given his track record Simeone is almost certainly the man to put it all right, and to do it quickly.

Are Manchester United and Burnley Just Regressing to the Mean?

A lot of ink was spilled last season on why these two teams were breaking expected goals models. Between them, the two sides conceded a shade under 90 expected goals but just 63 non-penalty goals: about 1.4 times better than we’d expect.

We’ve had a lot of theories emerge about why this situation might have arisen. In United’s case, the thinking has mostly been around David de Gea, goalkeeping superhuman. As for Burnley, there has been some talk of the keeping exploits of Tom Heaton and Nick Pope, but the assumption for the most part is that their superior ability to get bodies behind the ball in a compact shape means that xG models are overrating the chances they concede.

Cut forward a few months and the two sides together have conceded 15 non-penalty goals from around 11.5 expected goals.

So what’s happening? Is this just regression to the mean after a year of surprising overperformance? Is everything actually fine, and this is just a weird small sample size? Has something actually changed at either club? Let’s take a closer look.

Manchester United

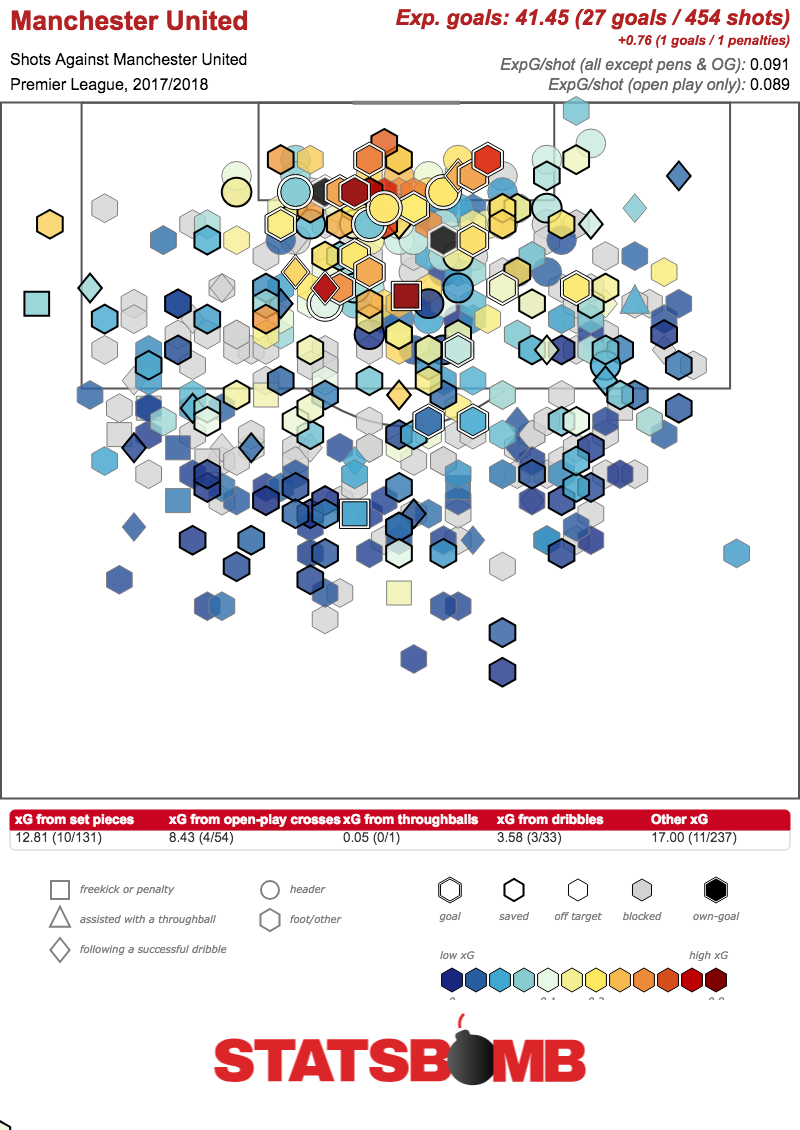

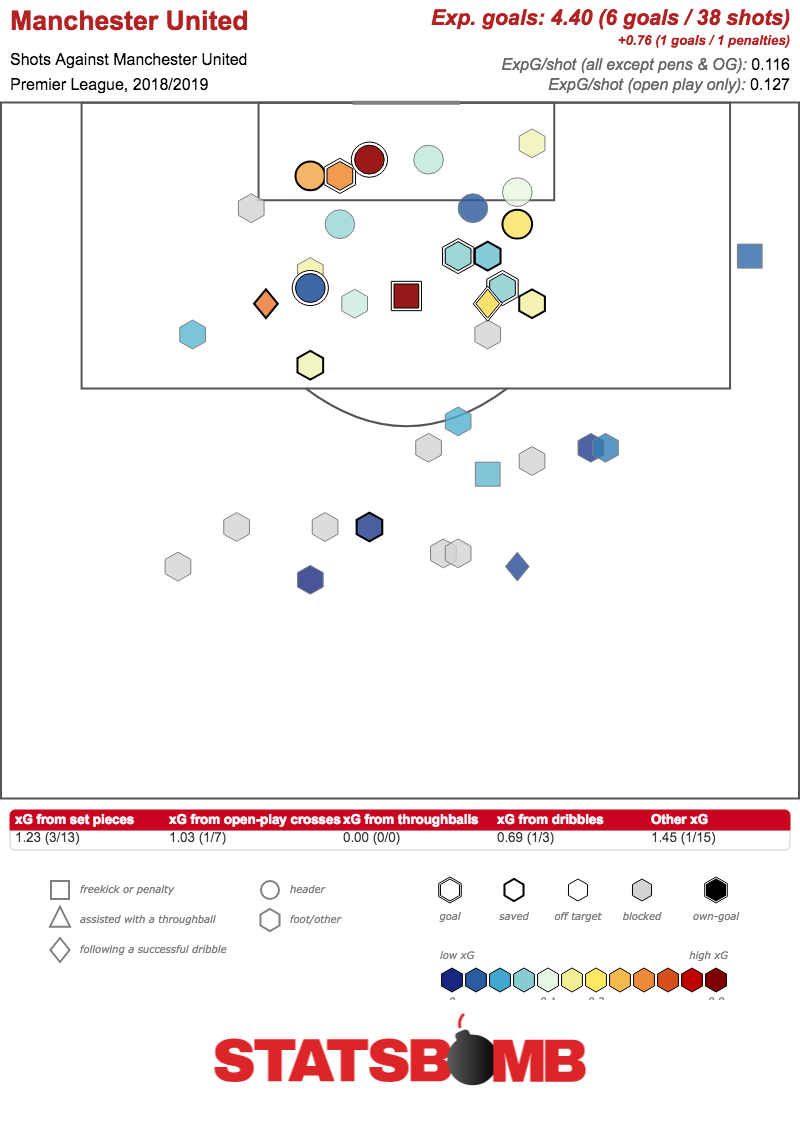

On the face of it, it’s hard to see what has changed for United. The manager is the same, the players are the same, save for Fred, who has been the side’s most aggressive presser off the ball without offering an awful lot on it. The system is still the same 4-3-3 that Mourinho adopted in the second half of last season, and it’s still producing around the same numbers it has been for all of this calendar year.

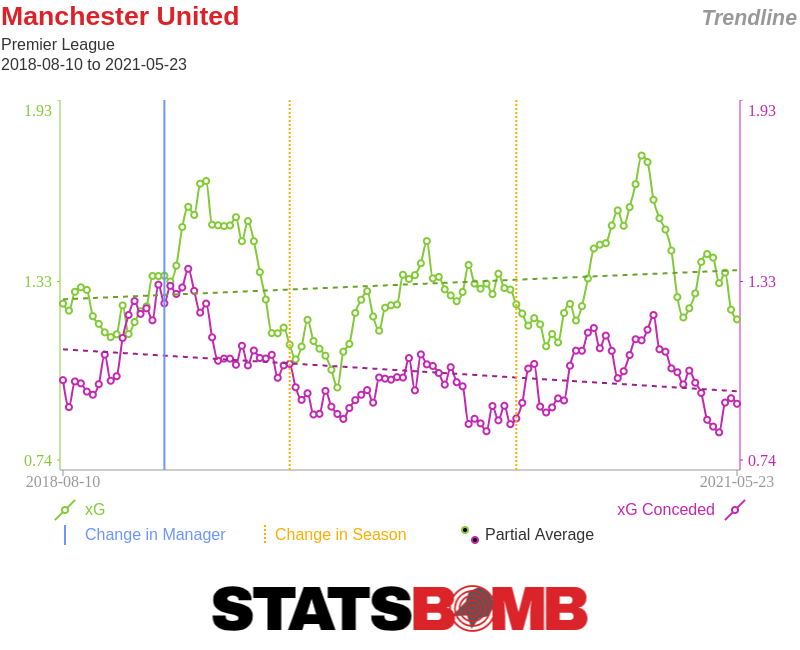

So, is anything different? It requires a touch of squinting, but there are some small differences that, if we’re being very generous, could have contributed. Even though the xG conceded per game is almost identical this year (1.10) to last (1.09), the xG per shot has risen from 0.09 to 0.12. The team are conceding about 2.4 shots fewer per game than last year, but those shots are a full third more likely to be scored. As to why that is, the early evidence suggests the side’s pressing profile has changed somewhat. United have completed 211 defensive actions per game, barely any different to last season’s 216, but the areas of the pitch where they choose to engage have shifted. In the final third, the team are now making around 43 defensive actions per game, a subtle increase on last year’s 40. In their own defensive third however, so far there has been a noticeable drop-off, going from close to 85 defensive actions last year to 68 now. This is a higher pressing United than last season. As such, it’s not a surprise to see a different profile of shots conceded, with high pressing systems generally associated with excellent shot suppression but the risk of giving away the odd very dangerous chance.

The other big question at Manchester United is around David de Gea. Consistently an above average keeper, albeit with an off the charts year last season that was surely unsustainable, De Gea has experienced some challenges in recent times. Following a World Cup with some high profile errors, De Gea has yet to find the groove of previous seasons. What might be notable here is that Spain were very much a high pressing side, one that conceded a low volume of shots per game (7.5) with a fairly middling xG per shot (0.10). It’s not that De Gea isn’t capable of performing well in a high pressing side. His excellent form under Louis van Gaal shows that he’s more than able to be a top goalkeeper in such a system. It is possible, though, and we’re definitely in straw clutching territory here, that a fairly sudden shift in the kind of shots he’s facing has caused disruption. He likely needs to take up starting points further off his line, and generally position himself differently to what his instincts might be. It’s also not inconceivable that a decrease in defensive pressure in United’s own third means that the shift in shot quality is actually greater than the model is indicating, and that the side were actually doing things that the numbers weren’t picking up on last season. The most likely scenario, though, remains simply that these are the early signs of a predictable regression, and we will need to see these trends continue for longer before making any bold claims.

Which brings us to another, slightly smaller, club in the North West…

Burnley

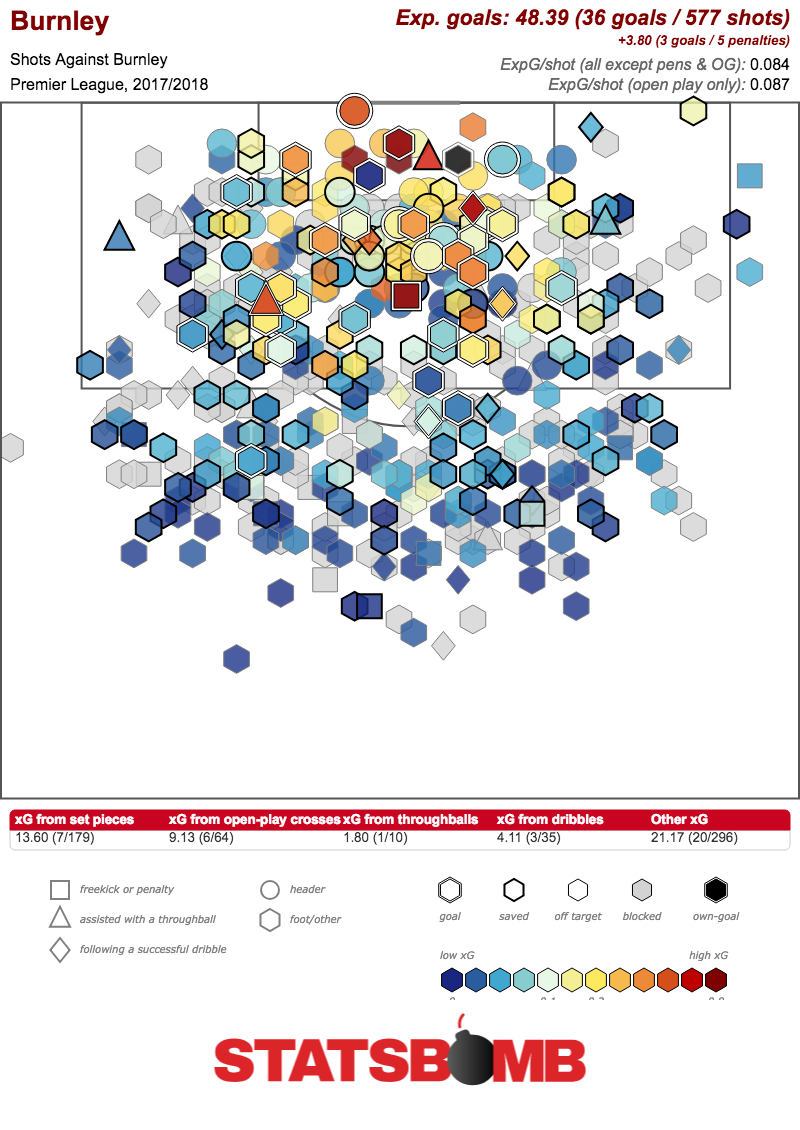

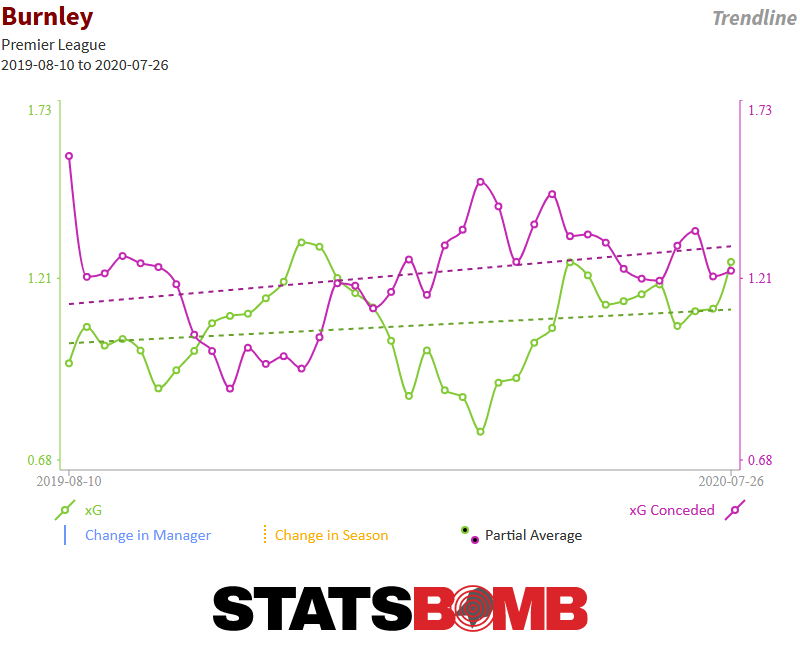

You can’t talk about beating xG without talking about Burnley. Their significant overperformance last season wasn’t even particularly out of line for them, and for some time now there has been talk that “Sean Dyche is a warlock”, such is his team’s ability to defy the models. The received wisdom in football analytics has always been that the side get a greater number of bodies behind the ball than average, making them better able to block shots (which they do a lot of) or just make it more difficult for the attacker to place his shot properly. That StatsBomb’s expected goals model, which takes player locations when the shot took place, did not rate Burnley’s defence any higher suggested this was in doubt, but it certainly felt as though something was happening. Underlying numbers fluctuated throughout the season and yet, save for a lull around midseason, results kept coming for Burnley last year.

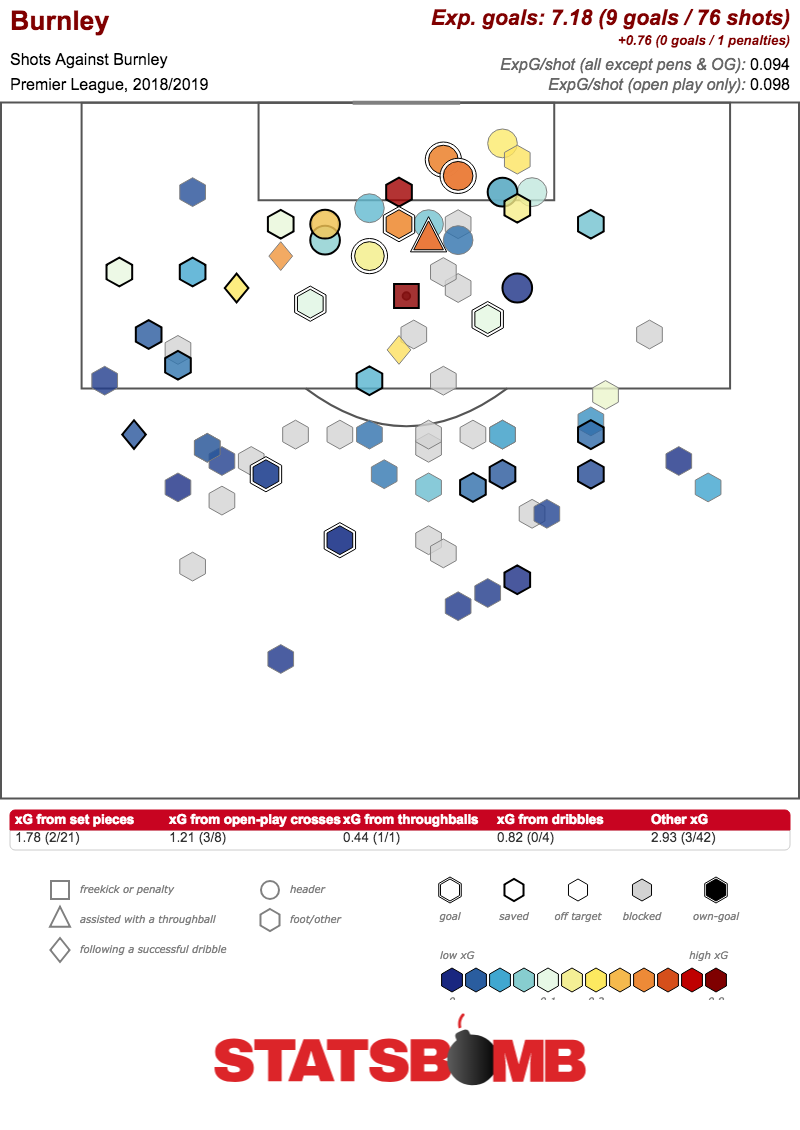

Currently, the side is on one point from four games, having scored three and conceded nine. The defensive magic that saw them invulnerable to xG has apparently dried up. Those of you who were sceptical that Burnley ever had anything sustainable in this regard will probably point to this again as the start of a simple regression, and you may have a point. The contingent who argued that Tom Heaton and Nick Pope were both simply goalkeepers who had fantastic seasons will look at Joe Hart’s less than stellar record and identify his arrival as the problem. Again, they may well have a case. But if there is an alternate reason, and it is a stretch to say that there is, it might be as follows. Burnley were an aggressive pressing side all over the pitch last year, but especially in their own half, as we can see from all the red on the defensive activity map:

Burnley on average made 220 defensive actions last season, while this season it is a small drop off to 198. What more, these actions in Burnley’s defensive third are down from 92 per game last year to 67 now. Burnley’s defending right in front of their own goal is a step less aggressive. We can see this elsewhere. Last season, Burnley managed to block 36% of the shots they faced, in what was a very important part of their defensive game. This year, that figure is 28%: not a dramatic fall, but still a less impressive figure. This may be just normal fluctuation from a sample size of just four games. It may be a fitness issue, with the Europa League fixtures causing trouble (a problem that will not recur, with the team failing to qualify for the group stages). It might be a deliberate stylistic shift. Again, we will have to wait for a larger sample in order to have any confidence.

Conclusion

It needs to be said that we’re four games into the season. This is nowhere near enough to make any grand, sweeping statements. Put it this way: we had a whole season of data last year and people still aren’t convinced what happened wasn’t a weird blip that would even itself out over time. Nonetheless, it was last season for both sides that was the outlier, and now we’re seeing something more in line with what we’d expect to happen on the defensive side.

There was always less of a sense that Manchester United were doing something that the xG models were genuinely missing than Burnley. While Dyche has a relatively long track record of this, Mourinho’s sides typically perform fairly close to expectations, so it was a surprise to see them suddenly concede very few goals from those chances. As such, a fall was always likely to be on the cards. Burnley are an altogether more questionable case, and this is perhaps one of the most interesting stories to track over the season. If they are able to turn this start around and get back to conceding improbably few goals, it will get harder to doubt Dyche’s warlock status. For now, though, questions remain, and any magic remains yet to be proven.

How Should England Build Their Team?

What did we learn about England at the World Cup?

First off, the team were heavily reliant on set-pieces to create chances. There was little to no open play creativity. Some were pretty convinced the new set-up was mainly for defensive purposes. I’m convinced otherwise because Steve Holland, Gareth Southgate’s assistant, said this in a great interview with Daniel Taylor at the Guardian:

“The game against Holland in March was the first time you would have seen us play with two offensive ‘No 8s’ rather than a Livermore, for example, who’s a good player but more defence minded,” Holland says. “Nigeria was the first time we tried Dele there – the balance of him running forward, the positions Jesse was taking up and Raheem dropping short. That created problems for our opponent.”

“After [Harry Kane], where are our goals? Dele has goals for Tottenham but hasn’t yet managed to do that consistently [for England]. Raheem has goals [for Manchester City] but hasn’t quite transferred that to international level. Jesse has taken time to get goals for Manchester United. He got into great positions [against Tunisia]. Have we better scoring options in that position? I’m not sure we have. We’re going with the players we think have the potential but they’re young men with not many caps. It might just take a bit of time.”

In that same interview, Holland stated that Southgate knew the start of a qualifying campaign wasn’t the time for revolution.

Arguably, neither is the immediate run up to a World Cup tournament, but hey, they changed it. But the new look is 11 games old now. It’s been tested out for several months both with competitive matches and the rare month-long opportunity to get continuous work in on the training ground in Russia.

So at the start of another qualifying campaign, will Southgate stick, or be brave and twist? Following the tournament the England boss played growth and development bingo in his press dealings. He was talking a good game. I have my doubts he’ll walk it. Throughout his career, Southgate has been Captain Sensible, it’s almost unthinkable that he would change it up now, especially as the media and public are with him.

Perhaps more pertinently, the start of the UEFA League of Nations is upon us. The new tournament provides a potential parachute to those who don’t make it in qualifying proper for Euro 2020 – the groups for which won’t even be drawn until December 2019.

This whole new format is absolutely perfect for making important decisions about team set-up way before any matches of real importance get going. Before 2018 is done, England get to try the current system out 5 more times against good quality opposition in Spain (twice), Switzerland and Croatia (twice). Oh and the USA too.

That would be 17 games in 6 months to get things to gel in attack. If it does, great. If it doesn’t and England still can’t get those chance creation numbers up, there’s some serious evidence there to drop it and still a full year to come up with a new plan for qualifying.

The Current Set-Up

England have produced a "DNA document" that discusses their ideas behind how they want to approach how they play, and it states that:

England teams aim to regain possession intelligently, with a focus on winning the ball as early and as efficiently as possible.

The World Cup centre back trio were Kyle Walker, John Stones, Harry Maguire. None of those guys regularly play in a back 3 for their club. Jordan Pickford does not keep goal with back three in front of him at Everton. Kieran Trippier and Ashley Young have never played regularly as wing backs next to a back three at club level.

By the numbers, the teams who press the ball highest up the pitch the last two seasons are Tottenham, Manchester City and Liverpool.

The teams that actually do as the DNA states don’t employ a back three regularly. Mauricio Pochettino and Pep Guardiola have flirted with one on the occasional trip out, but tend to go back to a four where they know it’s comfortable. Jürgen Klopp rarely strays from his beloved back four.

The Game Strategy “How We Coach” section of the DNA states:

Plan

- Devise a specific tactical plan for each fixture

- Use recommendations and evaluation from previous fixtures and training to inform planning

After each fixture the effectiveness of the game-strategy is reviewed against individual and team objectives. The review process utilises all available data and statistics and is supported by all performance service functions.

To my eyes during the World Cup, there didn’t seem to be much evidence of tailored specific tactical plan for each fixture. England played pretty much the same way against every opponent. And unless the effectiveness review was limited to just looking at the result, the poor attacking numbers in open play available clearly didn’t inform planning to change anything.

As our own Ted Knutson pointed out on Twitter even the set-pieces weren’t changed up. Everything was knocked in to Maguire. Effective? Damn, yes. A specific tactical plan for each fixture? Nope. We flog to death what we can see works right now.

Both Southgate and Holland have shaped the team into what they know themselves: the back three, the attacking full backs. Southgate as player played a huge chunk of his career in this system. Holland in the interview states his time at Chelsea under Antonio Conte influenced his back three thinking.

At the World Cup the back three dominated possession of the ball. All three made around a hundred more passes than anyone else. The only midfielder who made more passes than Pickford was Jordan Henderson.

Guardiola re-inspired football to the extent that people were talking about him playing with ten midfielders if he could. England are effectively trying to play with one. Where is the link up from all those ballers at the back to those runners up the front?

Sorry, but I’d drop golden boy Maguire. I don’t want three at the back and I want more people in midfield. As Pep has been caught saying: “The guy is not fast”.

Stones is just about better all round and more mobile, Walker is super quick, can defend 1 v 1 and mop up Stones’ gaffs (and his own). As a bonus, with no Maguire, it means England have to come up with a new set-piece routine or two before everyone figures out how to stop it.

After Harry Kane, where are our goals?

City don’t play with two offensive ‘No 8s’, a roving forward who also comes into midfield (Sterling) and a bustling centre forward (Kane) who also loves dropping off deep to receive the ball. Nor do Liverpool. Nor do Tottenham. Why? Because it doesn’t make any sense.

Recently, how has the ball transitioned from back to front effectively for England? It hasn't. Which is why they created next to nothing and can’t score goals goals from open play even with all those ‘goals’ in the line up. Coincidentally the ‘transition’ part of the DNA document in the ‘How we play’ section is one of the shortest. There’s more mention of goalkeepers in it than midfielders.

The top clubs playing the pressing game tend to use if not one playmaker, then two, or if none at all, then an entire central midfield at ease with having the ball 60 times a game each. Both their defences AND midfield dominate the ball.

Back to the DNA document:

The game-strategy is a tactical plan based on the availability of players.

Let’s be honest. England don’t have a playmaker like Eriksen, De Bruyne or Silva.

So let’s look at Liverpool as an example. Once Coutinho had gone, they didn’t have a traditional playmaker either. They played Henderson, James Milner and Georginio Wijnaldum. None are world beaters. But with the right coaching all are comfortable in possession, working the ball, feeding the more talented players, and pressing the ball. They got to a Champions League Final and were part of a team in the Premier League who boasted some damn good numbers. England might have had Henderson and Milner already but for the fact the latter retired from international football two years ago. And that's a shame, for though Milner doesn’t fit the age ethos England have going right now, even to a fairly rabid non-fan like me, there is absolutely no denying it – he’s played really well for 18 months.

For me, that means Fabian Delph should come in. He ticks all of the pressing, physicality and ball possession boxes. He also adds some left footed balance to midfield. Can England find someone to do something like Wijnaldum does? If you look at the Dutchman’s passing patterns and volumes, then yes, and he already played for England at the World Cup. Eric Dier!

The groans are audible, people. Shut up for a minute. Does Dier play for a pressing side? Yep. Does he fit the age profile we want right now? Yep. If you don’t like him then there’s a younger model on the numbers and his name his Harry Winks. Does he play for a pressi…you get the idea. But forget Winks, let’s stick with Dier for now.

We’re balancing up the Dier groans with some yays because Young would be gone for me. He is nowhere near a left back that you’d want in a pressing team, who works solidly for 90 mins like, well…Kieran Trippier. Do we have a player who’s played left back for a pressing team, who’s comfortable on the ball, who gets forward? Yes! Two of them were in England’s World Cup Squad! Fabian Delph would fit the bill, but we're using him in midfield so welcome Danny Rose.

That leaves us trying to replicate Liverpool’s front three in some way. First up let's look to the sides, can we find a Sadio Mané and a Mohamed Salah? Wide forwards, great pace, ball carrying skills, ability to get into good areas in the box. Raheem Sterling does that for City. Every week. Does he play for a pressi…you get the idea…

After that we’re struggling a bit for direct replacements in wide positions. Sterling is more like Salah than Mané. So who can match Mané’s pace, intelligent, well-timed runs in wide areas and ability to get in the box for goal scoring opportunities? For me, it’s Jamie Vardy. He hasn’t got Mané’s eye for a pass but he brings everything else to the table. However, Vardy retired from international football so that brings us to Marcus Rashford. He is a lot younger, nicer(!), and is more effective at carrying the ball.

That leaves someone for the Roberto Firmino false nine-ish role. Without much forward dynamism in midfield, the player here has to be mobile. Do we have someone that loves to dart back and forth between midfield and the box? Someone who can create and score goals? Plays for a pressing team? Step forward Dele! Yep, I’ve just dropped Maguire AND Harry Kane.

With the likes of Kane coming in you could go for a more orthodox front three. There’s a lot of diverse young forward talent making strides in the Premier League right now to add in too. At the back, Maguire for Stones is not really a problem either. There’s seemingly never been more young English defenders playing regularly at top level than right now. Identifying these contenders is for another article. For now, the shapes all make sense and the players make sense. Well, to me at least.

Can England become a genuinely good team with sustainable ideas that fit their published ethos? For me, there are loads of options to make numerous variations of 4-3-3 work where England should be able to join it all up more effectively - dominate possession of the ball in BOTH the first two thirds AND press effectively from the middle third onwards – all the while posting good underlying numbers at both ends of the field.

How Are Leeds Doing Under Marcelo Bielsa?

If we rewind back to the end of fall in 2017, Marcelo Bielsa was in a tough situation as a manager. The initial excitement of his hiring at Lille had dissipated within a couple of months and the club was residing near the bottom of the table in Ligue 1. Lille were bad enough under his watch that it led to a suspension and his eventual sacking in December. Bielsa was out of a job and what had looked to be one of the more intriguing projects in European football was now a relegation scrap. While his legacy remained strong thanks to the famous managerial disciples that have followed him and his time with the Chile national team and parts of his tenures at Athletic Bilbao and Marseille, the idea of hiring Bielsa in 2018 looked fairly risky. Add to it that he was going to Leeds, a team that's recent history has featured its fair share of dysfunction, and you could see why many people were skeptical and even outright snarky about the appointment.

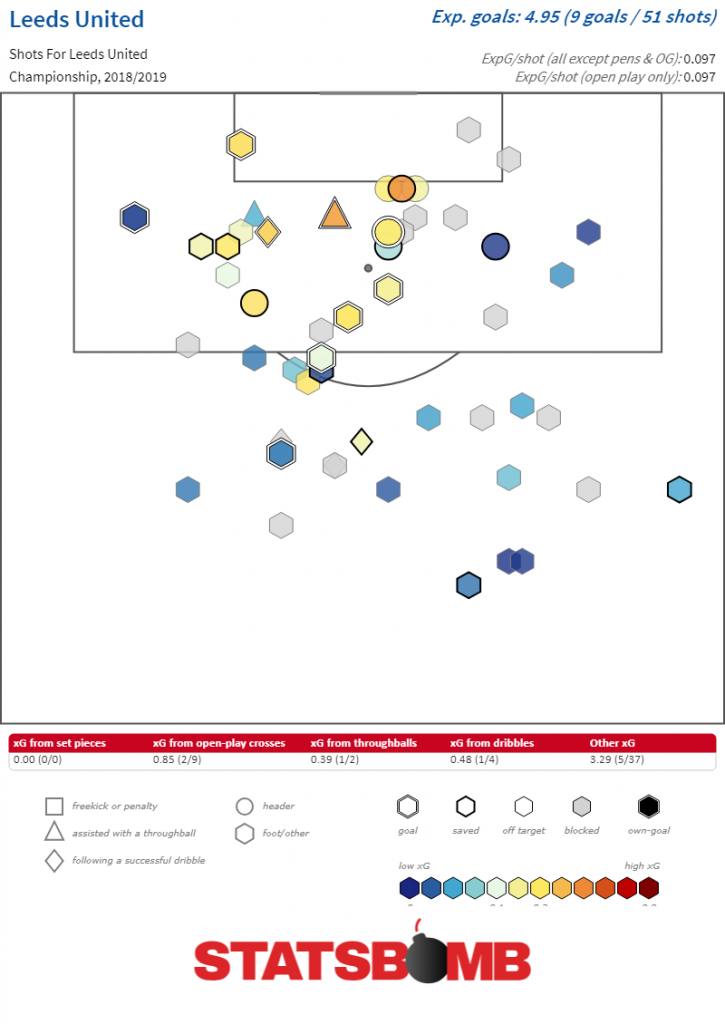

That said, while it’s very early to make concrete projections, Leeds being as good as they’ve been so far this season is a welcome sign. There are things to quibble about when solely looking at their first 6 matches, including a sky high shot conversion rate that’s helped boost their goal total, but Leeds have markedly improved their performances from last season.

With Bielsa led sides in the past, verticality has been a major part of the gameplan in attack. The simple idea is that the ball should get into advanced areas as quickly as possible. Already this is coming into play at Leeds. At times, they have had as many as five outfield players in the final third (striker, wide players, advanced CMs) with the goal being that once they recover possession of the ball through second balls or layoffs, they can strike up quick combination plays and create shots in the penalty box. That being said, it should be noted that Leeds rank near the bottom in the Championship in open play long passes originated from their own third. There is more than one way to be direct. What's there in addition to their moments of going direct is a team that’s shown the ability to attract pressure from the opponent and progress the ball from overloads and quick combination plays. When the opportunity arises once the goalkeeper is in possession of the ball, they’ll use a common tactic of spreading their CBs apart and bringing a midfielder inwards to create a numerical advantage deep to find a passing outlet.

Leeds have shown frailties during buildup play, and those frailties were most obvious in their two draws against Swansea and Middlesbrough. Leeds tend to leave a gap between the defensive midfielder (Kelvin Phillips) and the two advanced midfielders (Mateusz Klich + Samuel Saiz) when creating attacks. While this is largely by design, it does mean that being disciplined in regards to blocking passing lanes to the defensive midfielder can make it hard for Leeds to access the middle while in their own third. Leeds could not access the middle when Middlesbrough were in a set defense, relegated to ball circulation among the back line or going long from their own third. Britt Assombalonga did a good job for most of the match in positioning his body to make sure there was no pass available to Phillips. It would be one thing if the Middlesbrough match was an isolated incident because teams managed by Tony Pulis in the Championship are well drilled defensively, but similar things happened for long periods of time in their match against Swansea. It makes you wonder whether this will become more of a common occurrence as more games occur and Bielsa's style is more understood.

Once the ball is progressed further up the field, Leeds are most prolific when attacking on the left side because of the presence of Barry Douglas, one of the prolific chance creators from the fullback position in the league. While it’ll be hard to see him replicate the assist totals he had last season, there's no doubt that he's a good passer. No Leeds player has had more deep progressions (passes + dribbles + carries into final third) per 90 minutes than Douglas at 7.16. When he's off the ball, Leeds will try to get him sprinting into the wide areas near the penalty box while a couple of runners go into the heart of the box to create potential cutback opportunities.

Leeds can also attack from the right wing via Pablo Hernandez as he is really good both in directly creating chances for others or just simply generating passes into the box, but they've leaned more towards favoring the left side. When all else fails, Leeds have been very able to create opportunities via transitions or broken plays when the opposition don't have a set defense. This might be their best method of creating chances because they do a good job of supporting the man on the ball. With the presence of Hernandez and Sáiz, Leeds have the requisite passing quality to find runners making off ball runs and create chances from these scenarios.

Leeds can also attack from the right wing via Pablo Hernandez as he is really good both in directly creating chances for others or just simply generating passes into the box, but they've leaned more towards favoring the left side. When all else fails, Leeds have been very able to create opportunities via transitions or broken plays when the opposition don't have a set defense. This might be their best method of creating chances because they do a good job of supporting the man on the ball. With the presence of Hernandez and Sáiz, Leeds have the requisite passing quality to find runners making off ball runs and create chances from these scenarios.

Along with above average play in set pieces, Leeds have managed the best goal differential in the league this season at +10, and place second in goals scored at 14. On the surface, these are good indicators for their performance, but peek behind the curtains and you’ll see some concerns with their attack. While shot volume hasn’t been a problem in open play, their average quality per shot at just under 10% has not been the greatest and it’s been aided by the level of variance that isn’t sustainable long term.

Being a team that has above average open play shot volume but pretty average with their shot locations isn’t exactly the type of profile you want from your attack unless you’re lucky to have multiple players who have shown to be above average finishers. The goal is to take as many shots as possible from good areas and in absence of being able to marry shot generation + locations that in open play, you’re better off taking fewer shots that are higher quality chances versus taking a lot of inefficient shots and relying on variance going your way. This hasn't mattered so much so far because Leeds have had the variance bounce through six games, but you get into dangerous territory when you’re relying on that to prop up an attack to the degree that’s it’s gone for Leeds so far. This isn’t to necessarily say that Leeds are going to automatically regress back to break even because variance doesn't quite work in such a linear way within a season, but the odds of them continuing to out lap their expected goal output to this degree are next to none. It would be in their best interest to look to improve their shot locations to withstand a possible downturn in fortune moving forward.

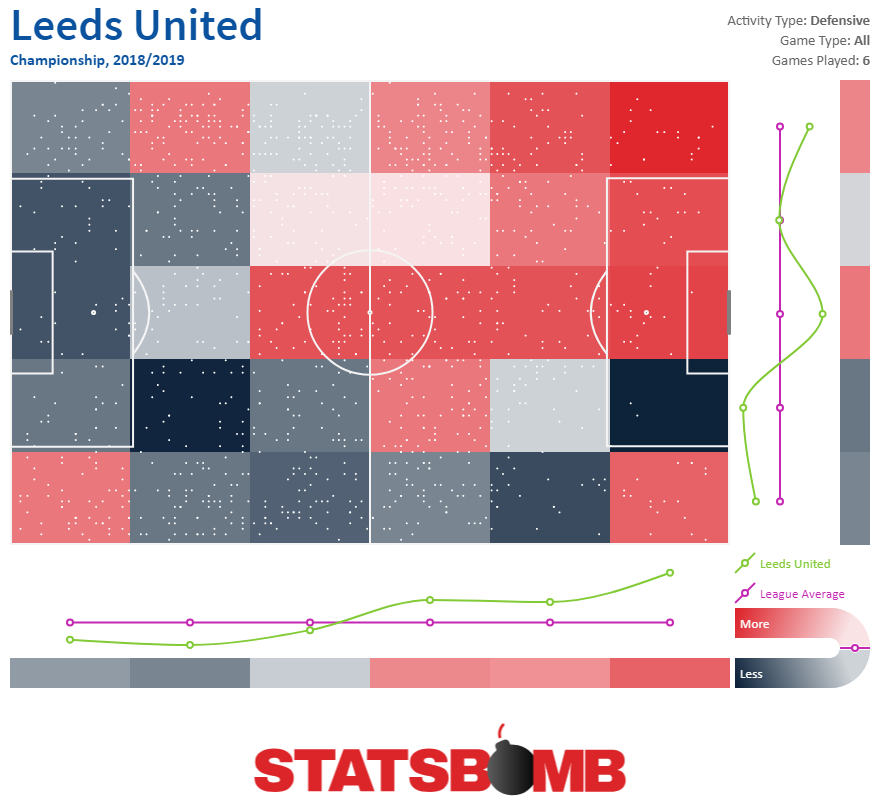

While Leeds attack has more questions than perhaps their goal totals would suggest, it can't be denied that their defense has been quite good even beyond their strong defensive record of four goals through six games. They've been able to combine both the ability to suppress shots by only giving up 11 shots per game and not allowing teams to create good chances from those shots, only giving up an average xG/shot of just over 8% in open play. Leeds have basically been what you would expect from a Bielsa led side at their best: junk up the middle by having everyone guard their own marker, and not be afraid for the game to turn into chaos ball.

On the whole, this has worked well but one problem with such a heavy man-marking scheme is that it can be susceptible to individual dribbling because you're not guarding space but rather where the man is at the time. In particular, opponents have had success here and there when using their center back to carry the ball from deep and provoke a Leeds player to try and match up with him, opening passing lanes around him and creating chain reactions that leads to dangerous opportunities. Kemar Roofe will be on his own up front trying to disrupt the two center backs, which means one will have the pathway to carry the ball into the middle third and possibly even further. Ball carrying from the center back position is something that I think will become more prominent in the years to come as another way of destabilizing a team's defensive setup, a way to add even more attacking value for a central defender on top of passing duties.

On the whole, this has worked well but one problem with such a heavy man-marking scheme is that it can be susceptible to individual dribbling because you're not guarding space but rather where the man is at the time. In particular, opponents have had success here and there when using their center back to carry the ball from deep and provoke a Leeds player to try and match up with him, opening passing lanes around him and creating chain reactions that leads to dangerous opportunities. Kemar Roofe will be on his own up front trying to disrupt the two center backs, which means one will have the pathway to carry the ball into the middle third and possibly even further. Ball carrying from the center back position is something that I think will become more prominent in the years to come as another way of destabilizing a team's defensive setup, a way to add even more attacking value for a central defender on top of passing duties.

It would be risky to suggest strong opinions about Leeds' future prospects for the rest of the season as we're only 13% of the way through, even though it would be fun if this side finished as one of the three promoted sides and finally made their way back to the Premier League. As much as it’s a cliche to say, the Championship in the 46 game season format it’s in makes it a grind, and Bielsa’s teams in the past have had their problems with pacing themselves through the season. Even if you're someone who's skeptical towards the idea that teams coached by Bielsa actually suffer the level of burnout that's been suggested, there are things to be slightly concerned about with their approach.

But it can’t be denied that on the whole Leeds have been fun so far, and the fact that they’ve so seamlessly become a proactive side that has shown the ability to blitz teams in doses is a credit on some level to Bielsa. He’s a genius, one with perhaps a short shelf life, but a genius nonetheless and it is nice to see him return to being a relevant name within European football. Even if this season ends in Leeds finishing just outside a playoff spot but having these peaks of exciting football, it’s a massive step up from basically every season Leeds have had over the past decade or so.

On the aggregate, Leeds have been good through six games. It could be argued that their performance level makes them closer to the 2nd/3rd best team in the league than one with the best goal differential and tied for most points, but they wouldn't be the first team to have their position in the table get some sort of positive bump. They have created a solid defense with an attack that's been fine but not necessarily better than that. As it's come to be with Bielsa over the years, all possible scenarios are on the table in regards to what happens with Leeds moving forward, but so far so good.

StatsBomb Podcast: The Kane Debate And Early PL Winners and Losers

Downloadable on the soundcloud link and also available on iTunes, subscribe HERE

Radar Wars

In August 2018, I was invited to be a keynote speaker at the CASSIS sports analytics conference in Vancouver. These are my slides from the keynote and I did a voiceover that is as close to what I said at the time as I can remember.

The first time I did a version of this talk was at Verily/Google around Sloan time in Boston. I didn't expect Evil Luke Bornn to be in the room, while I knew Seth Partnow would be there ahead of time.

This time, I knew Luke would be at CASSIS, but so was Sam Ventura, and there was a rumour that Daryl Morey was in Vancouver at the time (later confirmed), and could randomly show up as well. That created an odd, but amusing vibe. All of these people make appearances in this talk.

--Ted Knutson @mixedknuts ted@statsbomb.com

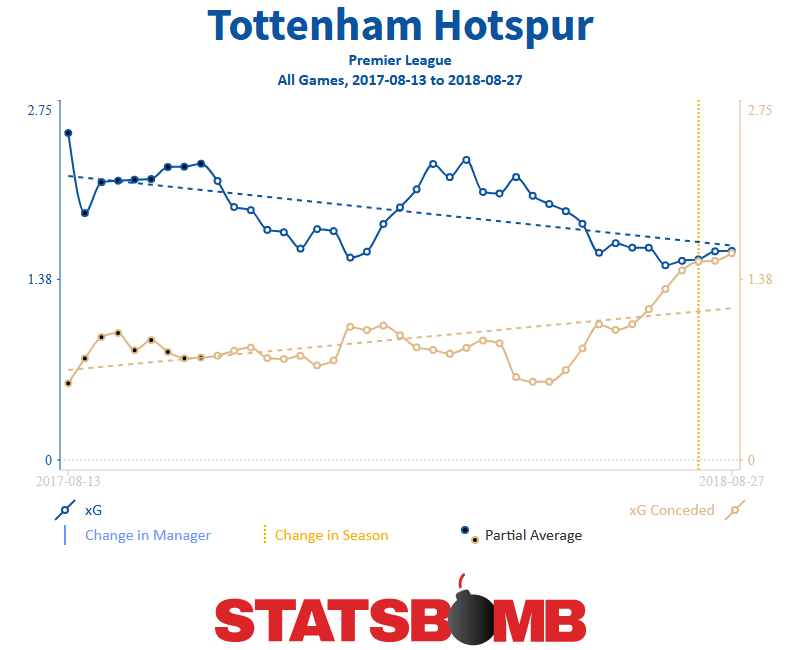

Tottenham's Defensive Issues: Fixing the Right Side

After a 3-0 victory at Old Trafford last Monday night, it would be easy to presume that Mauricio Pochettino would be overjoyed. In the moment, he made all the right noises but by the time Friday had come round and he was doing the pre-match press conference ahead of this weekend's Watford game, his mood had soured: "I was so disappointed. I think we need to improve our performance. The first half I wasn't happy and I translated that to the players. We need to fight against the perception. When you compare the perception and the reality, we need to talk about the reality, and the reality was in the first half we can concede one, two or three goals.” This attitude towards the performance is encouraging, for it shows a clear understanding of process, and while the result was ideal, the way in which it transpired was far less so. Across Pochettino’s entire Tottenham tenure, the team has not allowed more than the 23 shots that Man Utd created in this game. In the first instance, that’s a big red flag. Nobody expects a trip to Old Trafford to be a straightforward task, but nor does any plan involve allowing so many shots. Immediately it reflects a lack of control. The obvious kicker here is whether they were good shots. United’s xG for the game came out at around 1.7, so at least in part the answer is “not really”. However, Pochettino was correct in his assessment that United could well have scored, with Lukaku’s jarring miss the most obvious example, and he is correct to be annoyed that his team failed to keep United’s attack quiet. The vagaries of football mean that expectation and reality can often diverge in single matches, or over small samples of games and that’s why analysis is most useful over longer periods. The trend to reset the world and all totals as a season ticks from one to another is understandable but means much early season analysis does not lend itself to hefty evaluation. There really is no need to look at just this season, when we have all of last season that we can happily connect to this and the resulting trends to examine too. And that’s why we end up here: Tottenham’s defensive metrics have been trending negatively since around February:  Basically, across the last ten to fifteen fixtures, Tottenham’s expected goal production has been roughly equal in attack and defence. The attack side has been largely good, the defence has not. Let’s define the defensive numbers from the start of 2017-18 onwards, so 42 games. Since 7th April, via expected goals against, we have seen eight of Tottenham’s worst 10 performances: