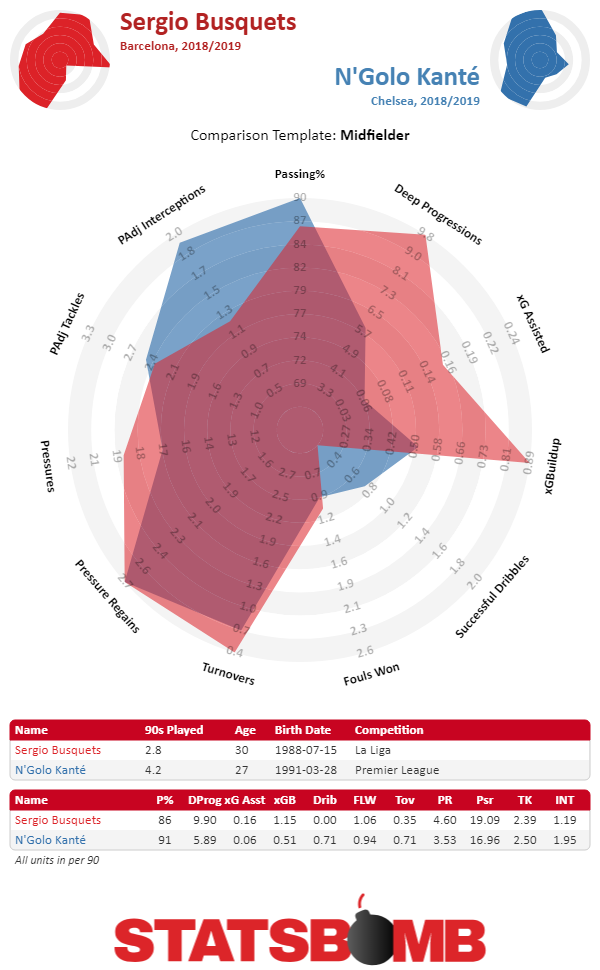

It’s been a while since the last StatsBomb mailbag. Summer’s over, the transfer window is closed and the domestic season is in full swing. Let’s answer some questions shall we? https://twitter.com/oldfashionedthe/status/1040512138396278784 Using defensive stats is hard. When profiling non-goal scoring players there are basically two different things you’re trying to do. You’re both trying to figure out what they do, and then to figure out how good they are at it. That’s why you don’t just look at one statistic, you look at lots of statistics. Which is why (among other reasons), we use radars. So, to take Kante and Busquets for example. They’re both nominally defensive midfielders. They’re both excellent. They also do very different things in very different contexts. Stats pick up on that though. They both have giant sized, but different looking, radars.  When you collect enough data, you can measure lots of different things. And, the further removed from goal scoring a player’s task is, the more varieties of skills they can use to accomplish their role on the field. The best players, and the best teams, marry skills to roles in a symbiotic way that makes everybody look great. As to the broader question of whether high defensive stats always mean that a player is good, the short answer there is no. Simple stats can be misleading in any number of ways, and part of the job of analytics is to account for that. Often times players with large numbers of interceptions and tackles aren’t particularly good, they just play on particularly bad teams that have to do a lot of defending. If your team is in possession of the ball, you can’t make a defensive action. That’s why we adjust defensive statistics for possession. It’s an easy way to further isolate exactly how often a player is making defensive actions in the context of how often they might have a chance to do so. Of course, the complications don’t stop there. Isolating a player’s impact from their teammates is difficult. Figuring out how players stop attackers without doing things that might qualify as a defensive action is important. For example, how do we measure a player being skilled at closing down passing lanes and forcing lateral passes? It’s a challenge. As always, the best way to think about statistics is as a tool to use to ask better questions, not as an ultimate answer. So, can the same stats tell us that both Busquets and Kante are good? Sure, if you’re looking at a broad enough, and smart enough, range of stats. But that’s only the beginning. https://twitter.com/RealJohnWolff/status/1040338249749688320 The thing about running a soccer club is that it’s hard. Think about the practical way that statistical based innovation in sport has to happen. I can be sure that something is true. I then have to convince people within a soccer club, usually fairly high up the organizational food chain that it’s true. They then have to pass marching orders down to practical level staff, management and coaches to act on that true thing. Those coaches then have to alter the behavior of the players on the pitch. That’s a lot of steps. There are tons of places things can go wrong, messages can get lost, implementation can break down, and that’s when everybody is on the same page philosophically about the breakthrough. Imagine what it’s like when there’s resistance. A relatively simple example of this is shot selection of course. The math is pretty conclusive on this one. It’s a much better decision for a player who’s around 35 yards out from goal to try a risky pass into the box than to take a whack at goal. Even if the pass comes off an extremely low percentage of the time. It can take some work to get people to buy into that idea, but it can be done. I know analysts who have actually had the coaching staff try and score from 35 yards repeatedly to drive the point home, or who have collated every single shot a player took from deep and made them sit and watch it in a row, just to drive the relative likelihoods home. But, even then, translating that knowledge into real action on the field takes work. It takes training. Often times there are years of instincts to be unlearned. Players have to learn to identify better situations, coaches have to learn to structure their team in ways to create those situations. It’s not just flipping a switch. I don’t want to discount the idea that sometimes analysts pick up on things we see as obvious and then those things get ignored. This month in the media there was some mild consternation over Liverpool hiring a throw-in coach. That’s something analysts (certainly the ones at StatsBomb anyway) talk about all the time as an easy, discrete, phase of the game in which some basic planning and coaching can convey at least a small edge. The fact that this might be mocked is indicative of those doing the mocking being insistent on shooting themselves in the foot out of spite. But, obvious examples aside, I think often times we’re all too quick to downplay the very real challenges of doing something new. Even when everybody agrees on an innovation, that doesn’t mean it automatically happens. https://twitter.com/sammcbride19/status/1040335244006760448 Yes. Much too early. Let’s at least wait until teams are playing twice a week before we write off players who were brought in, in large part, to improve the depth of a team. https://twitter.com/Tacticalfouling/status/1040366662523019265 I’ve written about the current Harry Kane struggles here before. His numbers are certainly down, and they have been since he injured his anklelate last March. Aside from the obvious implications for Spurs, the Kane situation is an interesting example of the ways in which sports challenges analytics to work with very little data. The reality is that from a numbers perspective you can’t say anything remotely definitive about Kane in a sample size that’s still well under 1000 minutes, spread out over the course of six months (not counting international play, because it’s tricky figuring out how to count international play). The question is, does the fact that you can’t say anything definitive mean you shouldn’t say anything at all? Because, realistically speaking, you very rarely if ever have the luxury of waiting until you have enough data to be sure about something in sports before you make a decision about it. To be nerdy about it, we should be Bayesian and constantly adjusting our priors. I expected Kane to be fine this season, I expected him to perform roughly at the level he performed at last season, although maybe slightly worse given just how supernova he went last year. I’ve now been shown some evidence to the contrary. That evidence is certainly not definitive. He may end up being totally fine, but so far he has been worse. I still don’t know why he’s been worse so far this season than last. Is it the lingering impact of his injury? Have tactical changes on Spurs shifted the way he’s played? Is it a combination of both? Did Kane’s injury down the stretch last year cause Spurs to evolve him into a slightly more reserved role, a role he’s still inhabiting despite being healthy? These are all possibilities. So is the possibility that there’s absolutely nothing wrong, and that Kane is going to take 20 shots over the next three weeks and score four goals. The point of all those words which could have just been a shrug emoji is to say that we shouldn’t really be asking the question is Harry Kane ok, but rather, how likely is it that Harry Kane is ok? And the answer to that question has certainly decreased as the weeks have gone on. https://twitter.com/FootEnStats/status/1040336361310576641 So much! Guys and gals we are so excited about all the stuff that we’re doing here and honestly we still feel like we haven’t scratched the surface of what we can do with all the data we’re collecting. We’ve teased goalkeeper stuff in the past, and that’s going to be rolling out in a more robust way. We have so much more work to do with pressure, and what it means, and how it influences games. Not just on the defensive side of the ball, but on the attacking side of the ball as well. We’re rebuilding passing models to more accurately reflect the real world. There’s also a super secret project or two floating around, because of course there is. Generally speaking most of the awesome stuff we do gets rolled out internally and for clients, and then slowly makes its way into the work we do publicly on the site. So, stick around we’ve got lots of cool stuff on the way.

When you collect enough data, you can measure lots of different things. And, the further removed from goal scoring a player’s task is, the more varieties of skills they can use to accomplish their role on the field. The best players, and the best teams, marry skills to roles in a symbiotic way that makes everybody look great. As to the broader question of whether high defensive stats always mean that a player is good, the short answer there is no. Simple stats can be misleading in any number of ways, and part of the job of analytics is to account for that. Often times players with large numbers of interceptions and tackles aren’t particularly good, they just play on particularly bad teams that have to do a lot of defending. If your team is in possession of the ball, you can’t make a defensive action. That’s why we adjust defensive statistics for possession. It’s an easy way to further isolate exactly how often a player is making defensive actions in the context of how often they might have a chance to do so. Of course, the complications don’t stop there. Isolating a player’s impact from their teammates is difficult. Figuring out how players stop attackers without doing things that might qualify as a defensive action is important. For example, how do we measure a player being skilled at closing down passing lanes and forcing lateral passes? It’s a challenge. As always, the best way to think about statistics is as a tool to use to ask better questions, not as an ultimate answer. So, can the same stats tell us that both Busquets and Kante are good? Sure, if you’re looking at a broad enough, and smart enough, range of stats. But that’s only the beginning. https://twitter.com/RealJohnWolff/status/1040338249749688320 The thing about running a soccer club is that it’s hard. Think about the practical way that statistical based innovation in sport has to happen. I can be sure that something is true. I then have to convince people within a soccer club, usually fairly high up the organizational food chain that it’s true. They then have to pass marching orders down to practical level staff, management and coaches to act on that true thing. Those coaches then have to alter the behavior of the players on the pitch. That’s a lot of steps. There are tons of places things can go wrong, messages can get lost, implementation can break down, and that’s when everybody is on the same page philosophically about the breakthrough. Imagine what it’s like when there’s resistance. A relatively simple example of this is shot selection of course. The math is pretty conclusive on this one. It’s a much better decision for a player who’s around 35 yards out from goal to try a risky pass into the box than to take a whack at goal. Even if the pass comes off an extremely low percentage of the time. It can take some work to get people to buy into that idea, but it can be done. I know analysts who have actually had the coaching staff try and score from 35 yards repeatedly to drive the point home, or who have collated every single shot a player took from deep and made them sit and watch it in a row, just to drive the relative likelihoods home. But, even then, translating that knowledge into real action on the field takes work. It takes training. Often times there are years of instincts to be unlearned. Players have to learn to identify better situations, coaches have to learn to structure their team in ways to create those situations. It’s not just flipping a switch. I don’t want to discount the idea that sometimes analysts pick up on things we see as obvious and then those things get ignored. This month in the media there was some mild consternation over Liverpool hiring a throw-in coach. That’s something analysts (certainly the ones at StatsBomb anyway) talk about all the time as an easy, discrete, phase of the game in which some basic planning and coaching can convey at least a small edge. The fact that this might be mocked is indicative of those doing the mocking being insistent on shooting themselves in the foot out of spite. But, obvious examples aside, I think often times we’re all too quick to downplay the very real challenges of doing something new. Even when everybody agrees on an innovation, that doesn’t mean it automatically happens. https://twitter.com/sammcbride19/status/1040335244006760448 Yes. Much too early. Let’s at least wait until teams are playing twice a week before we write off players who were brought in, in large part, to improve the depth of a team. https://twitter.com/Tacticalfouling/status/1040366662523019265 I’ve written about the current Harry Kane struggles here before. His numbers are certainly down, and they have been since he injured his anklelate last March. Aside from the obvious implications for Spurs, the Kane situation is an interesting example of the ways in which sports challenges analytics to work with very little data. The reality is that from a numbers perspective you can’t say anything remotely definitive about Kane in a sample size that’s still well under 1000 minutes, spread out over the course of six months (not counting international play, because it’s tricky figuring out how to count international play). The question is, does the fact that you can’t say anything definitive mean you shouldn’t say anything at all? Because, realistically speaking, you very rarely if ever have the luxury of waiting until you have enough data to be sure about something in sports before you make a decision about it. To be nerdy about it, we should be Bayesian and constantly adjusting our priors. I expected Kane to be fine this season, I expected him to perform roughly at the level he performed at last season, although maybe slightly worse given just how supernova he went last year. I’ve now been shown some evidence to the contrary. That evidence is certainly not definitive. He may end up being totally fine, but so far he has been worse. I still don’t know why he’s been worse so far this season than last. Is it the lingering impact of his injury? Have tactical changes on Spurs shifted the way he’s played? Is it a combination of both? Did Kane’s injury down the stretch last year cause Spurs to evolve him into a slightly more reserved role, a role he’s still inhabiting despite being healthy? These are all possibilities. So is the possibility that there’s absolutely nothing wrong, and that Kane is going to take 20 shots over the next three weeks and score four goals. The point of all those words which could have just been a shrug emoji is to say that we shouldn’t really be asking the question is Harry Kane ok, but rather, how likely is it that Harry Kane is ok? And the answer to that question has certainly decreased as the weeks have gone on. https://twitter.com/FootEnStats/status/1040336361310576641 So much! Guys and gals we are so excited about all the stuff that we’re doing here and honestly we still feel like we haven’t scratched the surface of what we can do with all the data we’re collecting. We’ve teased goalkeeper stuff in the past, and that’s going to be rolling out in a more robust way. We have so much more work to do with pressure, and what it means, and how it influences games. Not just on the defensive side of the ball, but on the attacking side of the ball as well. We’re rebuilding passing models to more accurately reflect the real world. There’s also a super secret project or two floating around, because of course there is. Generally speaking most of the awesome stuff we do gets rolled out internally and for clients, and then slowly makes its way into the work we do publicly on the site. So, stick around we’ve got lots of cool stuff on the way.

2018

StatsBomb Mailbag: Busquets, Kante, Harry Kane's Ankle, and More!

By Kevin Lawson

|

September 14, 2018