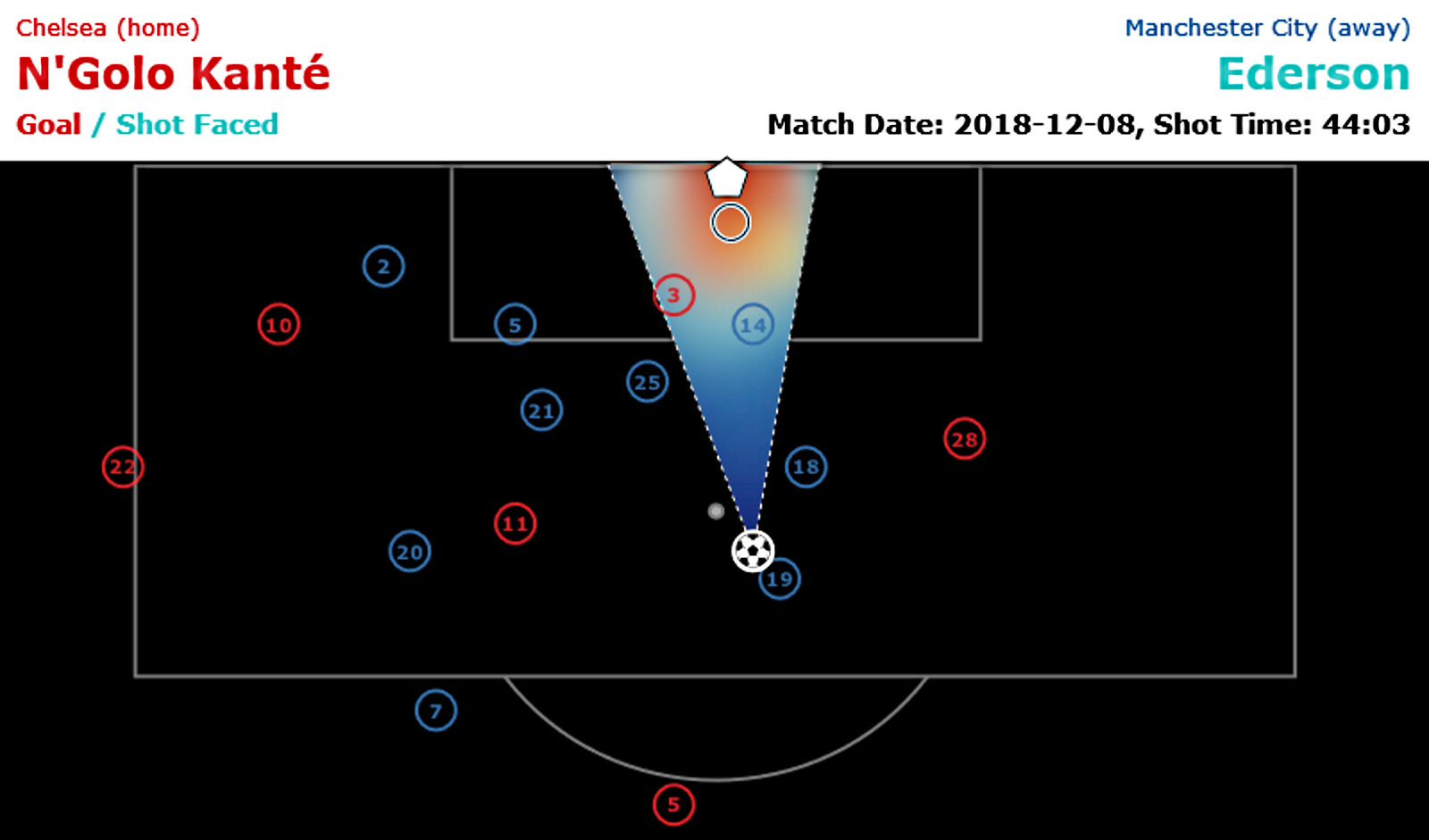

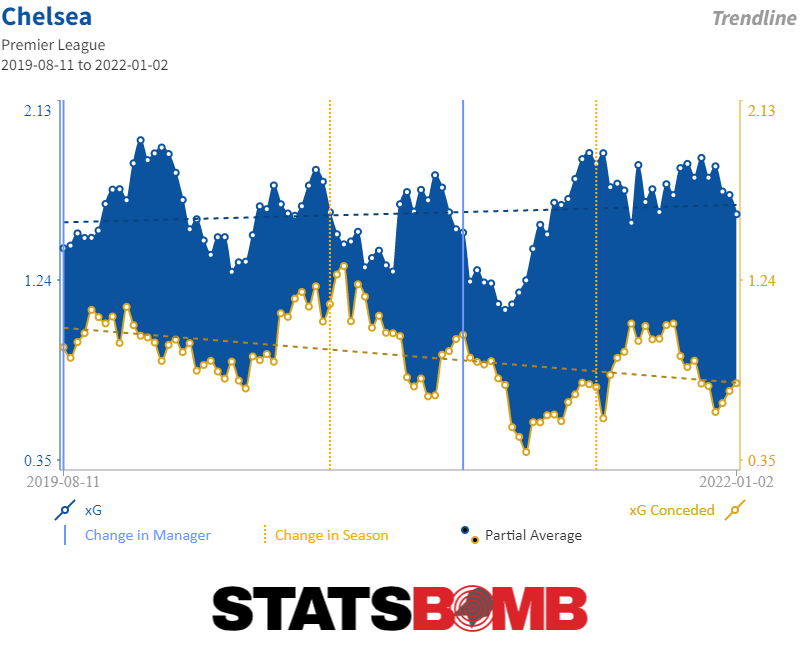

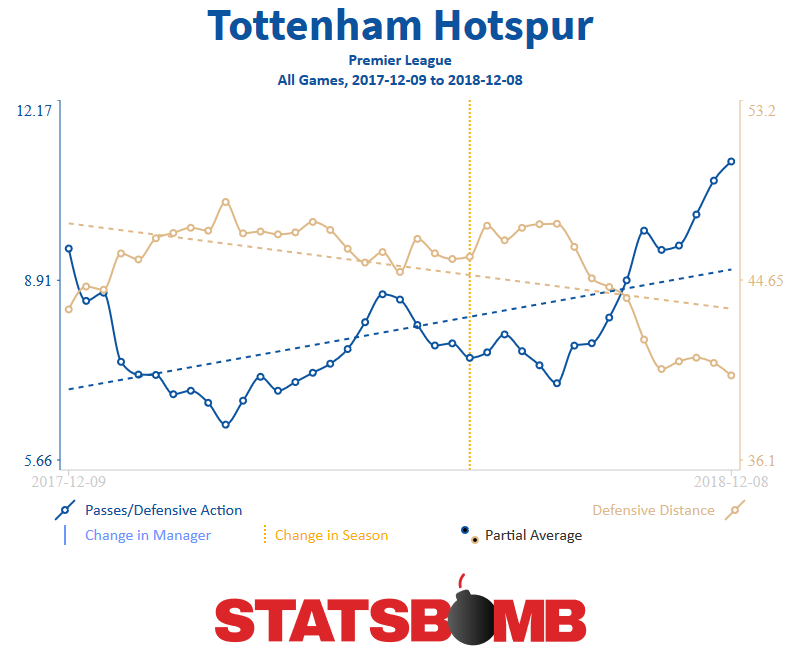

What a difference ten days makes. This little burst of Premier League action that traverses November and December certainly focuses the attention around what exactly is going on in the league. The main winners were as usual, the top five, who all scored a minimum of two wins and happily bamboozled the watching world by failing to clearly reveal who was in any kind of crisis. Chelsea moved on from a role of “the team that Tottenham destroyed”, dipped their nose into the crisis zone by getting beaten by Wolves, then rose gloriously to become “the team that beat Man City”. Tottenham moved from being “destroyed in the North London Derby” to quietly picking up straightforward wins against weaker teams, while even Man Utd got a break from the whip by rolling over Fulham with ease. Nice work when you can get it. Playing Fulham that is. With Liverpool marching on relentlessly (three wins out of three on the week) and Arsenal picking up seven points through variously impressive and grinding methods, it rather leaves Man City facing the music, at least for now. Mainly the focus will land there because it is so rare that they falter, despite the fact that all they did was get sucker punched in a tough away game, which can happen. At least it keeps things interesting for some weeks longer as the red side of Liverpool giddily consumes their now exclusive hold on an unbeaten start, and title dreams live on. Chelsea Chelsea’s result against City did a lot to keep the crisis-mongers at bay. The manner of the Tottenham defeat and the mere existence of the (more unfortunate) Wolves defeat would have been compounded had they been on the wrong end of another result, even allowing for the Man City effect. Pens were at the ready to supply Maurizio Sarri thinkpieces to a willing world. At times these result-reactive prevailing narratives are hard to inhibit, and can be erratically accurate, so Chelsea proving that they have some residual quality--despite the result being more impressive than the performance--created an new layer of protection. As time stood still, N’Golo Kanté strode through to make the decisive contribution and rocket the ball into the roof of City’s net. His arrival in the box was so late, as if to question the nature of his new box-to-box role, but he still arrived quicker than if had he still been sweeping house in his traditional defensive midfield position. Sarri is no doubt tired of explaining why he wants a passer and not a provocateur in the heart of his midfield. While it may be hard for home tacticians to understand why any team would line up with Kanté playing anywhere but his best position, if we consider him as a high class player regardless, perhaps it’s not that outlandish to presume he will adapt. The Tottenham game was an aberration that didn’t reflect wider progress, and while early in the season Kanté looked a little lost, recently that’s less often been the case. And after all, elsewhere in the league among sometimes troubled clubs, we occasionally see squad deficiencies bravely masked by defensive midfielders lining up among defenders in the back line, and that’s okay! Kanté at least still gets to play in midfield. If you must, Mateo Kovačić has zero goals this season, go pick on him.

Month: December 2018

Could Pablo Fornals Fit Into Arsenal's Rebuild?

Arsenal are one of a number of clubs reported to be keeping close tabs on the progress of Villarreal’s talented midfielder Pablo Fornals, who continues to impress in La Liga.

Before we get to the statistics, it is worth noting that Fornals is simply a very fun player to watch.

After a fine debut full season in the top flight with Malaga (0.27 goal contribution per 90 minutes), followed by an excellent campaign at Villarreal last time out (0.43 goal contribution per 90 off of 0.35 xG + xGA per 90), this season, the 22-year-old has continued to stand out even as part of a side situated in the lower reaches of the table. While his range of attributes haven’t quite yet coal

esced into a consistently decisive player, the raw materials are certainly there.

Fornals is comfortable using either foot, strikes the ball well, and has a touch of ingenuity to his game that allows him to break down sturdy defences with an unexpected pass or effort on goal. Impressive technical attributes are allied to an ability to maintain a high rhythm. “If in the first minute, I get into a race with the central defender or defensive midfielder, I won’t win it, but in the 90th, it’s more likely I will,” he said in a recent interview. “At that stage, I know that I am fresher than other teammates and opponents.”

His excellent fitness levels are borne out by the fact that he has only missed out on six match-day squads over the course of the last two seasons and this to date, and taken part in 81 of the 90 league matches his teams have been involved in during that time.

Last season, Fornals impressed at the tip of a midfield diamond, but this season, he has largely been employed in the wide positions of a flatter 4-4-2. He has been dribbling more often to help carry the ball forward (covering for the summer departure of Samuel Castillejo) and has been more forceful with his passing, playing the ball forward more and backwards less. He leads the team in deep progressions (passes, dribbles and carries into the opposition final third).

He is also still producing in attack. There has been a slight skew from assists towards shots, but the end result is the same 0.35 xG + xGA per 90 that he was providing last season. He leads the team in passes into the area, and still takes the same amount of touches there himself.

The positional change has required more defensive work from him. Villarreal remain a fairly average side in La Liga in terms of the intensity with which they press out of possession, but Fornals’ individual numbers have increased. He is making roughly the same number of possession-adjusted tackles and interceptions (2.12 per 90), but is pressuring the ball around eight times more per match and more often regaining possession.

In short, Fornals is making a bigger defensive contribution than last season, utilising a different set of skills to help his team progress the ball into the final third and once there, providing the same solid offensive output as in the previous campaign.

At 22, Fornals has established himself in La Liga and already made his debut for the Spain national team, but what makes him a really attractive proposition is that it still feels as if there is more to come. The way he has adapted to his new role this season suggests that with proper guidance, he could potentially develop into an elite player in any number of midfield positions. Especially so as he remains self-critical. He accepts that his constant desire to get involved sometimes results in him clogging up passing lanes for teammates, and has admitted that his flummoxing of Athletic Club’s Íñigo Martínez, linked at the start of this piece, had no real value given that the resulting cross was easily cleared.

Add that to an accessible buyout clause of €30 million and it is no wonder than interest in him is growing. Reports indicate that he has already rejected approaches from Fulham and West Ham, while Barcelona and Sevilla are also thought to be monitoring his situation. He is keen to stay at Villarreal until the end of the season in order to help them from their current position just above the relegation zone, and the feeling is that he is more minded to remain in Spain than make a move abroad at this stage of his career. Arsenal nevertheless may be keen to make a push for his signature.

The Gunners have been more proactive in their defensive work under Unai Emery, and Fornals fits the profile of a player who would be comfortable operating in such a setup. He has the attributes to perhaps become a less injury prone version of his compatriot, current teammate and ex-Arsenal midfielder Santi Cazorla, capable of operating deeper or further forward as needed. Looking across North London, it also doesn’t take too much of a squint to see similarities to Tottenham Hotspur’s Christian Eriksen.

It is clear that Fornals has a valuable set of technical and physical attributes. Next summer’s move will be key in dictating just how far they can take him.

Header Image courtesy of the Press Association

Six Theories About Burnley

It’s safe to say Burnley won’t appear in Europe next year. Despite languishing 19th in the table, they’re also not sure bets for relegation because the Premier League has quite a few bad teams. A team like Burnley — I repeat: Burnley — finishing, say, 17th is not an obviously interesting story. That is where teams that are neither tremendously dysfunctional nor wholly out of their depths often finish in the Premier League. Enter Sean Dyche. Footballing circles, especially those of the statistical persuasion, have spent the last few years getting dragged into debates about the manager’s team. During their stints in the Premier League, Dyche’s teams have been wont to outperform their underlying numbers. Could they being doing something advanced models don’t pick up on? Probably not, but inquisitive minds can’t leave it at that. And what if they did? Every win or setback for the team therefore becomes a referendum on the existence and nature of The Burnley Effect. It’s not hard to understand how we get here. Debating the existence of magic is sexier than the tedium of squad construction. In all the talk about what this season’s relative fall from grace means for The Burnley Effect, though, more mundane explanations for the team’s indifferent performances have fallen by the wayside. Alternately hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive with the existence of a Burnley Effect. Lots of things can be wrong with a team that maybe also does things expected goals models undervalue. Before debating Burnley’s supposedly magical defence and why it’s gone missing this season, we should probably work through the more obvious problems with this team.

- Burnley has steadily shed talent since 2014-15.

Kieran Trippier, Michael Keane, and Danny Ings have all moved on to greener pastures. (Well, Liverpool loaned Ings out to Southampton, but still!) In some cases, replacements have been conjured out of thin air: James Tarkowski arriving for a pittance has made the loss of Keane tolerable. In other cases…[wildly gesticulates in the direction of the black hole that is the striker position]. Some of this is economics. Burnley, as one of the Premier League’s less wealthy team, has chosen to invest in infrastructure instead of players. But that leaves them with a moderate talent drain and additions like Aaron Lennon, Steven Defour and Jack Cork, who are useful but don’t change the team’s talent situation. Burnley, in other words, has worked very hard not to get worse for the last five years. They’re in a situation where good coaching doesn’t preclude spending time around the bottom five of the Premier League.

- Don’t look now, but this is not a young team.

Burnley has regularly fielded some of the 2018-19 Premier League’s oldest sides. (Along with Brighton and Watford, they account for all but one of the 25 oldest XIs this season.) Instead of mixing youngsters and veterans, the team gets to its average age of 29 by fielding a mass of players aged 28, 29, and 30. Its youth contingent is often just left-back Charlie Taylor (25) and striker Chris Wood (26). The team’s profile suggests that many of its players are still useful but on the tail-end of their primes. A good coach can still get something out of such a team, but it’s hardly a surprise if players in this age range start experiencing marginal losses in physical ability. The uniform age of Burnley’s squad, moreover, means that downside risk is spread across the entire team. (Watford, on the other hand, fielded five players aged 27 or younger in its oldest squad, but they were playing alongside 34-year-old left back José Holebas and, in a position that ages differently, 35-year-old goalkeeper Ben Foster.) All of this can be related to the previous talent point, insofar as Burnley has sold its young performers and profited by bringing in older facsimiles. The deeper resemblance, though, is that it’s a picture of a team working very hard to not get worse.

- They’ve played Joe Hart, who is extremely washed.

This one isn’t complicated. Burnley have two goalkeepers and they also have Joe Hart. Joe Hart has not been a good goalkeeper for many years. But Burnley, due to injuries and their own decision to sign him, have started Joe Hart 14 times in the Premier League this season. In those matches he’s conceded 25 goals, which…yikes? This may not be unrelated to whatever the rest of the team is doing, but StatsBomb’s calculation of Goals Saved Against Average also suggests that Hart (-1.0%) has been slightly below par. By the same metric last season, Burnley goalkeepers Tom Heaton (9.8%) and Nick Pope (7.6%) were both much better. Before staging a referendum on the Burnley Effect, then, it’s worth remembering that starting Joe Hart — who is in fact and talent a third-string keeper at this point in his career — has been an issue.

- IDK it’d probably help if they had a striker.

The story of Burnley’s defence is complicated and nuanced. The same cannot be said for its attack. Nobody claims that Sean Dyche is an offensive wizard. Last season Burnley generated 0.95 expected goals per 90 minutes…and scored 0.95 goals per game. These were low totals achieved extremely inefficiently, but the goals came at the right time and the defence made them count, so they were just good enough. There was no indication that Burnley would get better at putting the ball in the net this season. And they haven’t! Oooooooooooh boy have they not, in fact. Through 15 matches, Burnley are averaging a league-worst 0.75 expected goals per 90 minutes. Only Brighton are lower. Other teams in the relegation zone were faring better. Thus far, Burnley’s saving grace is that it has scored 14 goals against 11 expected goals. This sort of over-performance has been needed just to approximate last season’s paltry scoring level. The attack is bad, and it’s unlikely that it’ll continue to overperform its underlying numbers. Forwards Sam Vokes, Matej Vydra and Ashley Barnes all have goal totals that are between 150 and 200% of their expected goals totals, and none of them have the pedigree to suggest they’ll do better than expected goals in the long run. Chris Wood is the only forward who isn’t running hot right now. A slight uptick in form on his part, however, would hardly fix Burnley’s problems. This is a bad, inefficient attack — as it has been for quite some time.

- The game states, they haven’t been good.

It is likely not a mystery to Sean Dyche that his team is not an attacking powerhouse. His tactics reflect this. Throughout his tenure, the platonic ideal of a Burnley match has been one where his team takes the lead and then protects it, thereby obviating the need to score any other goals. Paradoxically, this strategy requires Burnley’s attacking players, who are few and not very good, to score first. Put otherwise: How often can a group generating a near to league-worst 0.75 expected goals per 90 minutes be expected to open scoring? If your answer to that question was “you can barely expect Burnley to score in 90 minutes, never mind before any other team in a league where they have the worst attack,” you have spotted the issue with this year’s team. Even with a less impressive defence, Sean Dyche’s tactics still depend on his team scoring first. They haven’t recorded a single point in the Premier League when opponents score first. All but two of their points have come from matches where they score first. The two stray points were nil-nil draws. What’s gone wrong? Luck plays a part: Burnley converted some low-value shots early in games last season and has not done that much of late. This, however, is mainly a talent story. Burnley rarely takes an early lead — or any lead, for that matter — because that would require players capable of generating good chances. Burnley is generating 0.08 expected goals per shot, taking very few shots (8.5/90 minutes), and counting on bad attackers to make something of those chances. Of course they don’t take many leads. (Again, this is all happening while many of Burnley’s players — and the team as a whole — overperforms expected goals.) Burnley’s attack was never good, but this year’s decline has made what was always a difficult balancing act nearly impossible. For good measure, having to chase games more often is unlikely to have done the defence any favours.

- It’s not actually that unusual for Sean Dyche’s Burnley to go on long streaks of futility.

Even last year, which is held up as Peak Burnley, saw the team go winless for more than two months. This had a negligible on Burnley’s spot in the league standing because the team had enjoyed a good start to the season and other sides were in strange forms of disarray. It also helped that Burnley’s underlying numbers, while rarely great, were better. Still, it can be helpful to remember that Burnley has only produced a few good Premier League months in the Sean Dyche era. This context can help clarify our questions about this year’s team. Europa League Burnley isn’t coming back; the real question is if the team that does enough to not get relegated is still out there.

Turning Theory Into Practice: Paul Riley Meets Swedish National Goalkeeping Coach Maths Elfvendal

Back in 2012, spurred on by my wife and a friend who out of boredom at work deliberately sparked daily debate with his outlandish football takes, I started blogging about football and using data to answer the questions it poses. Fast forward six years and what started as a mess about has become seriously surreal.

Twitter gets its fair share of criticism, but it’s enabled me personally to reach crazy great people. At first it was all about volume of traffic and gaining new followers. Soon, it became about more than that. I was invited back to my home town to visit Bolton Wanderers’ Head of Analytical Development, invited by the Scouting and Recruitment Co-ordinator of my beloved Everton to speak with him at Finch Farm. It’s still bonkers to me that people in the professional game speak to me, read some of the words I’ve written and listened to some of the words I speak. Following my StatsBomb come back in August the Swedish national team goalkeeping coach messaged me wanting to chat.

There’s a feeling that the new generation of football club analysts and coaches, routinely more formally educated than their predecessors, are embracing new ways of communicating their ideas about the game. Maths Elfvendal is definitely one of these guys.

“Wherever you’re working you need to be good in a lot of areas to be a good coach these days," says Elfvendal, “but especially the bigger the club or the bigger the national side. It’s getting complex. You need to handle the social relationships. With the national team you have one, two, three goalkeepers who think they should be playing. You need to handle them with care – both individually and as a group.”

Elfvendal has been a semi-professional footballer in Sweden. His father was goalkeeping coach for the Swedish U21 team, and coached in the Swedish top flight while Maths grew up looking on. Now the boy is grown up and goalkeeping coach for both IFK Norrköping and the national team. Elfvendal is still only 31 years old but has somehow also managed to fit in 5 and a half years of university - learning to be a secondary teacher in social studies. He sees his educational experience every bit as important as his footballing background: “I adapt myself to the goalkeeper I have. I speak to every goalkeeper in a different way. In one way I have those years learning how to teach. In another way I have years of experience in the dressing room and hear what footballers say. I need to adapt.”

The concept of adaptation comes up repeatedly in our two hour chat. Elfvendal believes the new wave of technology and information available now is changing the game rapidly. It’s a matter of keeping up and developing your own philosophy or being left behind. “I’ve been reading your blog and it’s helped me a lot to build my own philosophy, both from statistics and also experiences with goalkeeper coaches and players,” says Elfvendal casually. I nearly choke on my cup of tea. “A lot of football experience can be short-cut these days. With all the information we have you can gain the necessary experience and knowledge of the game much faster now.”

I have to admit, despite being flattered by Elfvendal’s comments I’m still a ‘football philosophy’ sceptic. If you have three keepers to look after with the national team and they’re all different how do you approach a training session they’re all involved in? “That’s interesting. They are different, definitely.” he says. “Physically, technically. They also play in different leagues. On international duty the standard is only three training sessions before a game. For me, to believe I can change them technically in that space of time and for them to then perform at their best would be naive. With the national team my training sessions are based on tactical aspects for the next game, for the next opponent. In that sense it’s easier. How do we want to build up our play, how do we need to protect the area from crosses or from cutbacks. These positional changes we can change a little bit. It’s more based on the game plan so the whole team is on the same page. At a club there’s more time to work on technical detail. Also, you have to respect that the clubs own the players, we just borrow them for the national team. I don’t want to change anything that will negatively impact them when they go back to their clubs. I don’t want to say something when the coach at their club says otherwise.”

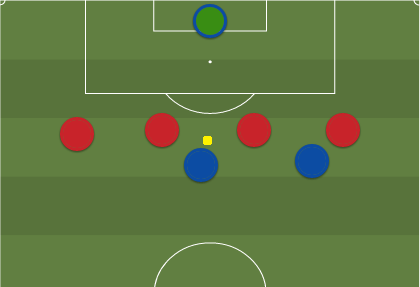

The teacher is eager to test me using some of the presentation slides he uses when delivering lectures to other coaches. “What position do you prefer the goalkeeper to take up?” he says flicking up a still of an attacking situation. The goalkeeper has been removed from the image. “See the positions marked there? One, two, three, four, five. I want you to tell me in 5 seconds what position you want the goalkeeper in.”

“One or two?” My answer is more of a question.

“Yes, thanks, next!” barks Elfvendal. “One, two, three, four, five?”

“Two?”

We go through a couple more before this bomb is dropped on me:

I take longer than 5 seconds. “Er, five? I feel worried now, Maths.” He laughs at me.

I start bleating: “It depends on your goalkeeper and what you want the team to do I guess.”

“Ah,” he says switching to the next slide. “It’s in Swedish there but it says ‘What information do you need to have to answer the question of what the best position is?’.”

“Are you asking me?”

“Yeah, you taught me one of them so…”

This statement doesn’t help. I start rambling about what your coaching style is (are you leading as coach or are you allowing the player to lead you). Is the keeper good at moving? Can he move his feet?

“Ok, that’s two. Team tactics and goalkeeper style. Four more.”

“Four?!”

"You don’t need to answer, it’s just a fun game.” He sounds disappointed. I try and up my game.

“Ok, so I want to know where my defenders are. Do I want to be aggressive and hit the opposition on the break if I can quickly gather it?”

“That’s still tactics. I don’t have all the answers here…” My brain has gone.

“Tell me what else?”

“Expected goals! What is the expected goal value of a shot from here?”

“Next to nothing."

“Right so what is the expected goal value if he is assisting one of the forwards? He can cross it here. There’s a defensive line four versus two. As a keeper you can either be aggressive and come and get it, say at position 2 or position 4 on the picture.”

I remark that the Premier League I see more and more that keepers are taking up position 7 or even a 9 as if they’re terrified of being beaten on the near post.

“Yeah, you have a big problem there if the header comes.” Elfvendal modifies the picture an adds an extra attacker: “How does your position change now?”

“Possibly between 5 and 7?”

“This is really interesting”, he says. “Do you think if the ball is played into him where the attacker has moved to now, do you have enough reaction time standing on his line?”

“Yes.”

“Yep. So if the ball is played in front of him to five and a half metres…ah…to the six yard line, I am talking to an Englishman now. Do you think you have reaction time?”

Elfvendal is well aware of my comfort zone preferences. He’s fishing. Images of David De Gea saves flash through my mind. I take the bait: “Yes.”

“I think you overestimate a little bit,” he laughs. “From my point of view you will have difficulty reacting in a good way from there. A guy called Scott Peterson is doing some science about this. What’s the likelihood of saving the ball depending on the distance between the ball and the goalkeeper? Imagine you are in position 8. You will be one to two metres away from the striker, less reaction time but close enough to block the sight of the whole goal with your body. Back on your line you have more time and reach but are not covering so much goal. Also Scott’s research shows that the conversion rate for a goal when the distance between ball and goalkeeper is 2-7m is significantly higher than any other distance.”

I start protesting about sample size, the possibilities and permutations of what could happen as things stand in the still image. Anything could happen from here. Is Elfvendal teaching physical cues? He flicks another image on screen. “I showed this to one of the participants on my course,” he says.

Yeah, by the way, Elfvendal is a course instructor on the UEFA goalkeeping A License. “We’re just looking at the biggest threat,” says the Swede. “From my point of view I’m trying to prevent a high value xG chance here. From position 2 or position 4 I can gather a cross to stop the header every time. I can also move to position 8 quickly if there is a striker coming to the near post like the second picture.” He shows me several video clips of keepers doing just that. Then he shows me another still. Pretty much the same as the first two but the man with the ball is just wider, out near the touchline about 25 yards out.

“What if the keeper is super aggressive? What if he is out like near the penalty spot leaving his goal open? How does the xG change?”

I’m still in stupid mode: “There isn’t enough sample to model it.”

“I was expecting a deeper answer here,” he says sounding disappointed again. He perks up immediately and laughs. “Use your imagination! You can be aggressive here. I showed the goalkeepers, I put them in the position on the ball near the touchline that far out. I stood myself near the penalty spot. Try and score against me guys. Left foot from there, score on me now. They didn’t score a goal I can tell you that. It’s harder than people think. By being higher, you are not risking too much being beaten from there, but you’re helping the team by protecting a higher xG value chance being made from the cross.”

And it dawns on me that right here is the value of theory meeting a real life practitioner. A practitioner influencing real outcomes, taking it to the next level with a logical step. I’ve been looking at this stuff for years, I’ve never even thought of it this way and this guy is here crediting me for the inspiration. “I see all kinds of rubbish on the internet about evidence based coaching,” I say. “This is the real deal.” “Yeah,” says Elfvendal, satisfied.

After two hours, I think the coach is finally happy with me. He’s used every trick in the teacher’s book – serious voice, disappointed voice, gentle mocking, laughter and praise to bring it out of me.

And how do I feel?

In footballers parlance: “I’m buzzing.”

Christian Pulisic Is Very Good. It’s Just That Jadon Sancho Is Amazing.

The only thing people love more than heralding new, exciting young talents is discarding them for newer, more exciting young talents.

This is the story with Christian Pulisic and Jadon Sancho. Way back in the final stretches of the 2015/16 season, when it looked as though Thomas Tuchel could build a dynasty at Borussia Dortmund, a 17 year old Pulisic was beginning to receive some minutes off the bench and looking rather interesting in the process.

The following year, he managed to become a more integrated part of the side and managed to get everyone excited. The United States had produced its first great men’s soccer player. The rumours of a big money move to the Premier League were abound. The world was to have a new superstar. Then Sancho turned up in Dortmund and stole his career.

Let’s track back on that slightly.

Sancho arrived at Dortmund from Manchester City in the summer of 2017, with the then 17 year old having to wait until the second half of the season to get on the pitch, just as Pulisic did at the same age. In what was a mess of a Dortmund side, he took to the Bundesliga like a duck to water and established himself as the poster boy for young Englishmen plying their trade in Germany.

He initially started this season on the bench, but a string of great performances as a substitute ha meant he has forced his way not just into the starting eleven but has become a key player for Lucien Favre’s potential title winners. The player he displaced from the starting line up? Christian Pulisic. Let’s take a closer look at them both to see what’s going on.

Christian Pulisic

In some senses, Pulisic feels like the star of a Dortmund team that never existed. Having been signed by the club as a 16 year old back in 2015, he was clearly groomed for the kind of football we saw from the club under then manager Jürgen Klopp. With Klopp’s reign coming to an unceremonious end, Thomas Tuchel came in with broadly the same principles, albeit a greater emphasis on possession play.

While Tuchel’s first season was built around Henrikh Mkhitaryan, Marco Reus and Shinji Kagawa in the attacking midfield roles, his second saw a changing of the guard, with Pulisic and new signing Ousmane Dembélé now trusted behind Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang. Dembélé was clearly the senior partner here, setting himself up for the big move to Barcelona. But Pulisic showed himself to be well on the way to stardom, combining a terrific natural talent at dribbling through congested areas with intelligent off the ball movement.

Of course, the side’s inability to build on the previous season’s results combined with reported clashes with senior figures at the club led to the end of Tuchel’s reign, though a theoretically similarly minded figure in Peter Bosz was appointed. The less said about Bosz’s reign, the better, and he was replaced by Peter Stöger in less than ideal circumstances halfway through the season. Almost by accident, Stöger began the trend away from the club’s famed pressing game and towards a deeper counter-attacking approach, a move that has been heavily reinforced this year by Favre.

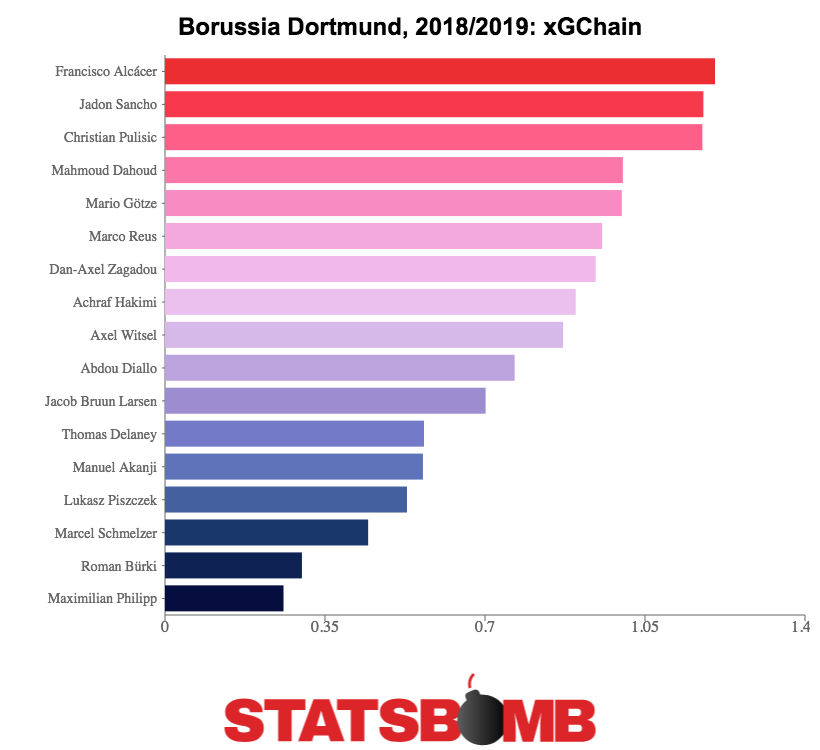

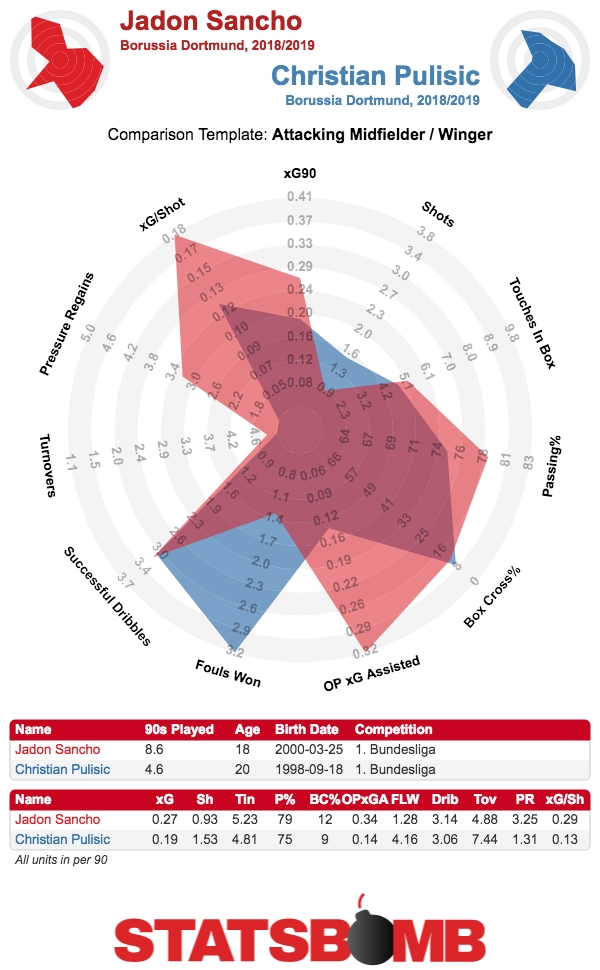

In an alternate world where Dortmund are in the fourth year of Tuchel, it’s easy to imagine Pulisic as a key player. Under Favre, he increasingly seems sidelined. So is he failing to have any impact? Well, not quite. For Dortmund, his xGChain this season remains as strong as Sancho and behind only Paco Alcácer.

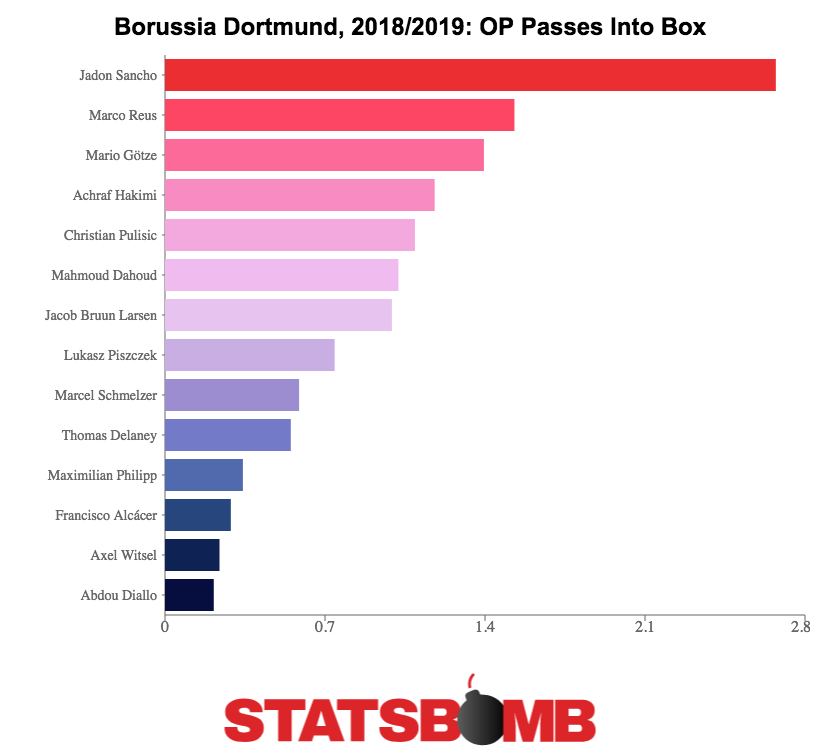

He is involving himself in just as many sequences that lead to high quality chances as Sancho, albeit not in such noticeable and arguably decisive ways as the Englishman. He is dribbling a solid amount (3.06 times per 90) but his expected goals and assists remain fairly middling. Nothing about his creative passing really stands out as much as it perhaps should for his ability in the numbers. It does feel as though he has stalled.

As he matures and evolves his game, it may be that he is more suited to being a ball progressing midfielder than a wide player. In recent weeks, Pulisic has been heavily linked with both Chelsea and Liverpool.

If he were to move to Liverpool, it is easy to imagine a positional evolution similar to Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, with the American’s skillset well suited to Klopp’s quest to turn stalling attacking midfielders into deeper ball progressors.

The Chelsea move would also have logic behind it, with Sarri’s possession heavy pressing system probably much better suited to the Favre set up. While one could see him as the most advanced midfielder in the 4-3-3, a position currently occupied by Ross Barkley, it’s easy to imagine him as a zone moving wide forward replacing Willian long term and sharing some of the burden currently taken by Eden Hazard.

This could help Hazard become the goalscoring wide forward Sarri wants him to be while replacing some of the ball progression he’s been doing in the past few years. If he goes to either of these clubs, it seems like he could have an excellent career in the Premier League. As it stands, the more ball progressing part of his skillset doesn’t seem especially useful to a Dortmund side who want to move up the pitch quickly with the speed of some of the other attacking players. Such as…

Jadon Sancho

If Favre’s arrival at the Westfalenstadion has been a hindrance to Pulisic, it might have been the best thing that could have happened to Sancho. During the player’s time in English youth football, the player was seen as something of an unpredictable dribbler, someone who could do something truly surprising at any point.

“You get a lot of players in academies who have been coached, but [Sancho] has got that natural street ability where you don't necessarily know what he is going to do before he gets the ball. He then goes and carries it past two or three players with ease”, stated former England Under 16 coach Paul Williams.

“He could be our Neymar-type player – in terms of being unpredictable, playing on that left-hand side”, claimed another former England youth coach Dan Micche. That is, of course, “provided he doesn’t become restricted”.

Favre is, of course, not a manager who likes to play “unrestricted” football. “Efficient” would be a better word to describe his approach, with his continual ability to overperform expected goals in part a feature of compact organisation and getting men behind the ball.

At Borussia Dortmund in particular, this has been accompanied by a counter attack at blistering pace, with relatively little scope for slowing down and overcomplication. This has kept him at a relatively medium 3.1 dribbles per 90, while Micche’s proposed idol Neymar puts up 4.8 and stat breaker Adama Traoré manages 5.0.

What he is doing a lot of, though, is creating chances, with Sancho assisting as many expected goals in open play per 90 as anyone else in the Bundesliga. He’s also become a key ball progressing cog, becoming comfortably Dortmund’s most frequent player to complete open play passes into the box. This is a team that are top of the Bundesliga and a not insignificant amount of their attacking plan seems to be to give the ball to this 18 year old.

It has at times felt recently as though some particularly gifted young English players have been allowed to be a little too unrestricted. Players such as Jack Wilshere and Ross Barkley have been encouraged to flourish without really being defined to specific roles and tasks, and it does feel as though it has contributed to them stalling, as Barkley himself implied when he admitted he hadn’t been coached at Everton to the extent he is right now at Chelsea.

Sancho, meanwhile, finds himself in a situation where he is being given clear instructions and responsibilities. Though Neymar is the superstar Micche suggested he should emulate, perhaps Sancho might be best off looking at the early evolution of Cristiano Ronaldo. Under the tutelage of Sir Alex Ferguson, a young Ronaldo was taught to generally simplify his game, reducing the “tricks” and becoming a more decisive footballer in the process. While it is unlikely that any player will achieve as much as Ronaldo, this does seem to be the path that he should be aiming for under Favre.

Conclusion

Predicting the path of player development is hard and fraught with elements that are difficult to control. Pulisic seemed to be blazing a path to great success before dipping somewhat in the past 18 months. Sancho is currently defying logic with his form, but it is very possible that he will see similar frustrations in the future.

A player such as Raheem Sterling spent several years unable to perform like he did at age 19 before having a sudden leap in production under Pep Guardiola. It happens. Improvement is not linear. While he has the advantage of being more suited to the style of football, it does feel right now as though Sancho has a higher ceiling than Pulisic.

That Dortmund have tied Sancho down to a new deal while apparently being open to letting Pulisic go suggests the view is the same internally. But this is not a huge indictment of Pulisic rather than an endorsement of Sancho. Both look more than capable of having terrific careers. Bear that in mind if you’re reading an article in two years’ time about how Sancho is struggling to live up to expectations.

StatsBomb Podcast: December 2018 #1: Southampton, Burnley, NLD, Tottenham Midfielders & Burnley

Beyond The Narrative: What's The Truth Behind Wolves' Poor Run?

Wolves’ time in the Premier League was hotly tipped to be a roaring success. In recent weeks, the results have waned and they now find themselves down in twelfth place: perfectly respectable for a newly promoted team, but perhaps slightly underwhelming given the pre-season hype. So how good are Wolves?

Promotion and a fine start

Powered by significant investment, the team readily won the Championship in 2017-18 having retained their position at the top of the league from the end of October through til May. The summer saw more investment, or at least a bunch of the previous season’s loans got made permanent, and a sprinkling of class was added on top. The aging but richly decorated João Moutinho arrived to form a “Portugal, Then And Now” central midfield alongside last year’s club Player of the Season Rúben Neves while Rui Patrício gave the team what every newly promoted side could do with, a competent goalkeeper. Football stats fans also got the coin in the Christmas pudding when late on Adama Traoré confirmed a move from Middlesbrough, to continue his love affair with ball carrying and the touchline at the highest level.

And for two months, it went really well.

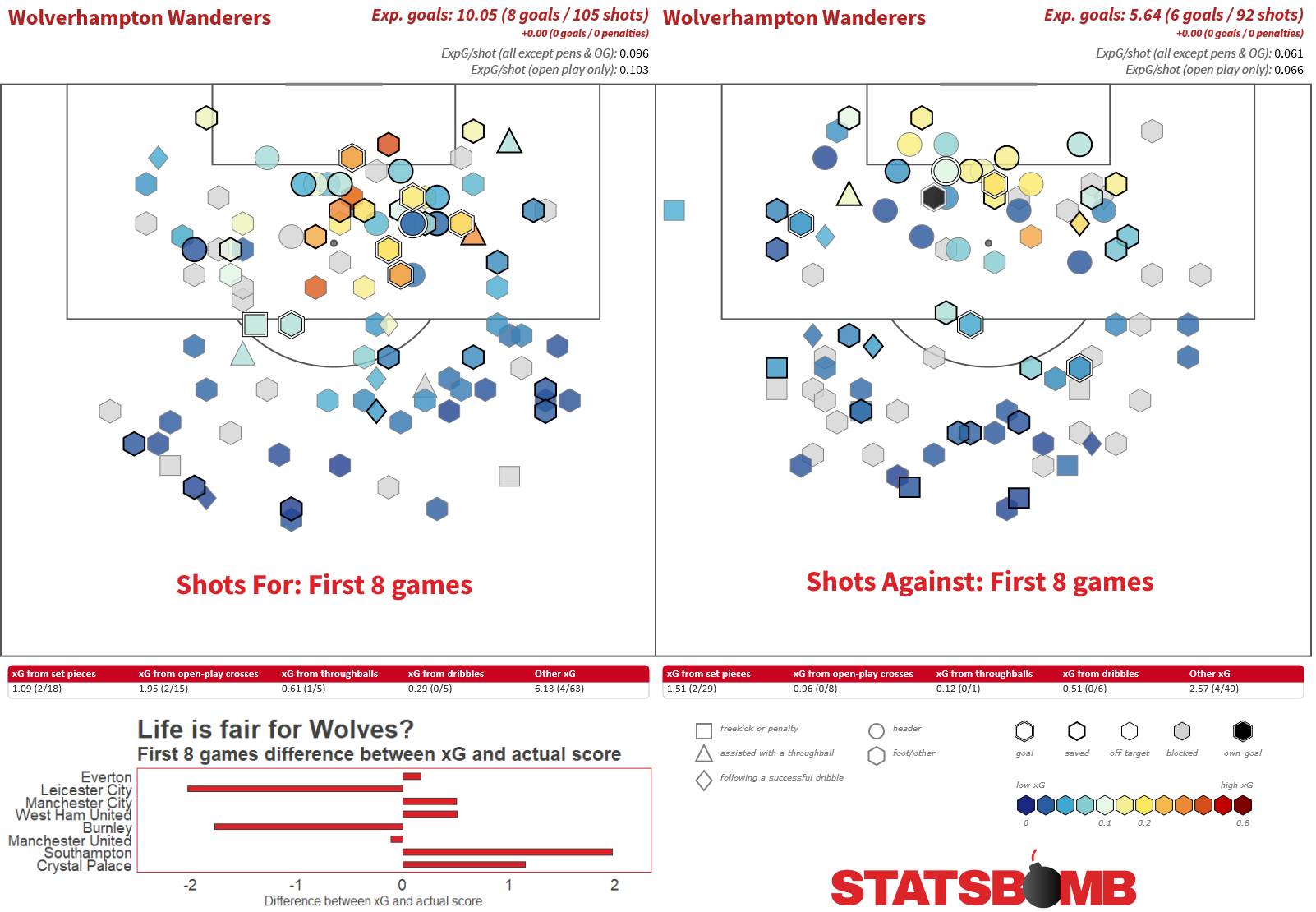

Draws with Everton, Manchester United and most notably Manchester City were all more than ample reward for a team new to the division, and a 30 shot 1-0 beatdown of last season’s seventh placers, Burnley showed the world that Wolves could compete well at this level. On the 6th October, Wolves sat seventh with a 4-3-1 record and a plus-two goal difference, a shade behind their plus-four and a half goal expected rate:

The inset bar chart shows the single game differences between expected goals and the actual score. As is evident, throughout the first eight games, there was a fairly usual split between expected goals skewing in favour or against Wolves.

Six games of misery

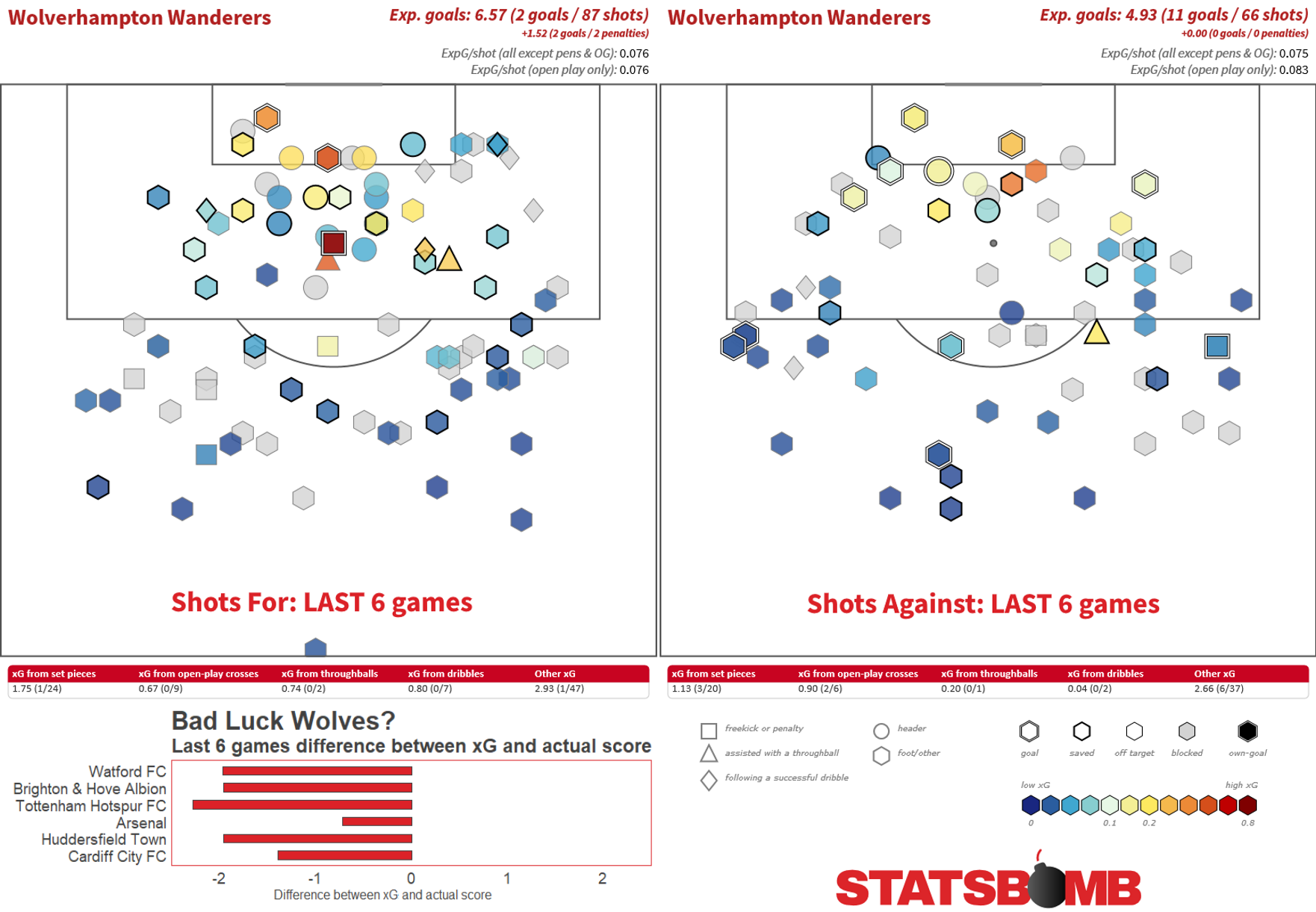

The last six games have been close to a disaster for Wolves: in a mixed schedule they have lost five and drawn one. There is no shame in being edged out by the odd goal in five against Tottenham and a draw against Arsenal was good, perhaps even disappointing given Henrikh Mkhitaryan’s late equaliser. Otherwise, home defeats to Watford and Huddersfield don’t read too well on the surface and neither do away defeats at Brighton and Cardiff. Yes, Wolves are a newly promoted team, but also these are all teams that they need to perform well against and pick up points. To hit a bad run at exactly this moment is far from ideal, especially given that they host Chelsea and Liverpool as well as the return games against Man City and Tottenham, all within the next six weeks. Points may be hard to find this at times through early winter.

However, the last six games have had an almost comical negative skew for Wolves. Expected goals still likes them--a lot-- and has them (including their two penalties against Tottenham) at about eight goals to five across this period, so a healthy +0.5 xG per game. Reality has taken a far darker turn, with four scored and 11 allowed. Ignore the penalties and you’ve got the overall attack at four and a half goals behind expectation and the defence behind by six goals. And consistent too! Check out the skews in the bar chart subset. Wolves just can’t buy a break right now:

If you evaluate the goals Wolves have conceded recently, quite a few have emerged from the realm of the improbable. Mkhitaryan’s goal was a cross that went the whole way, Etienne Capoue drilled one from thirty yards and Junior Hoilett’s winner last Friday night was the type of hit that might go in once in fifty attempts, possibly less than that if the pace of it could truly be accounted for. That estimate isn’t trivial, they all spec out as between 1.5 and 2.5% chances.

Attack

So we’ve established that Wolves have been on the mother of all cold streaks recently, but the simple interpretation is that their profile isn’t that of a team that will struggle long term. There are two aspects in play though: in attack Wolves look no more than okay but have finishing woes, while in defence they look very solid.

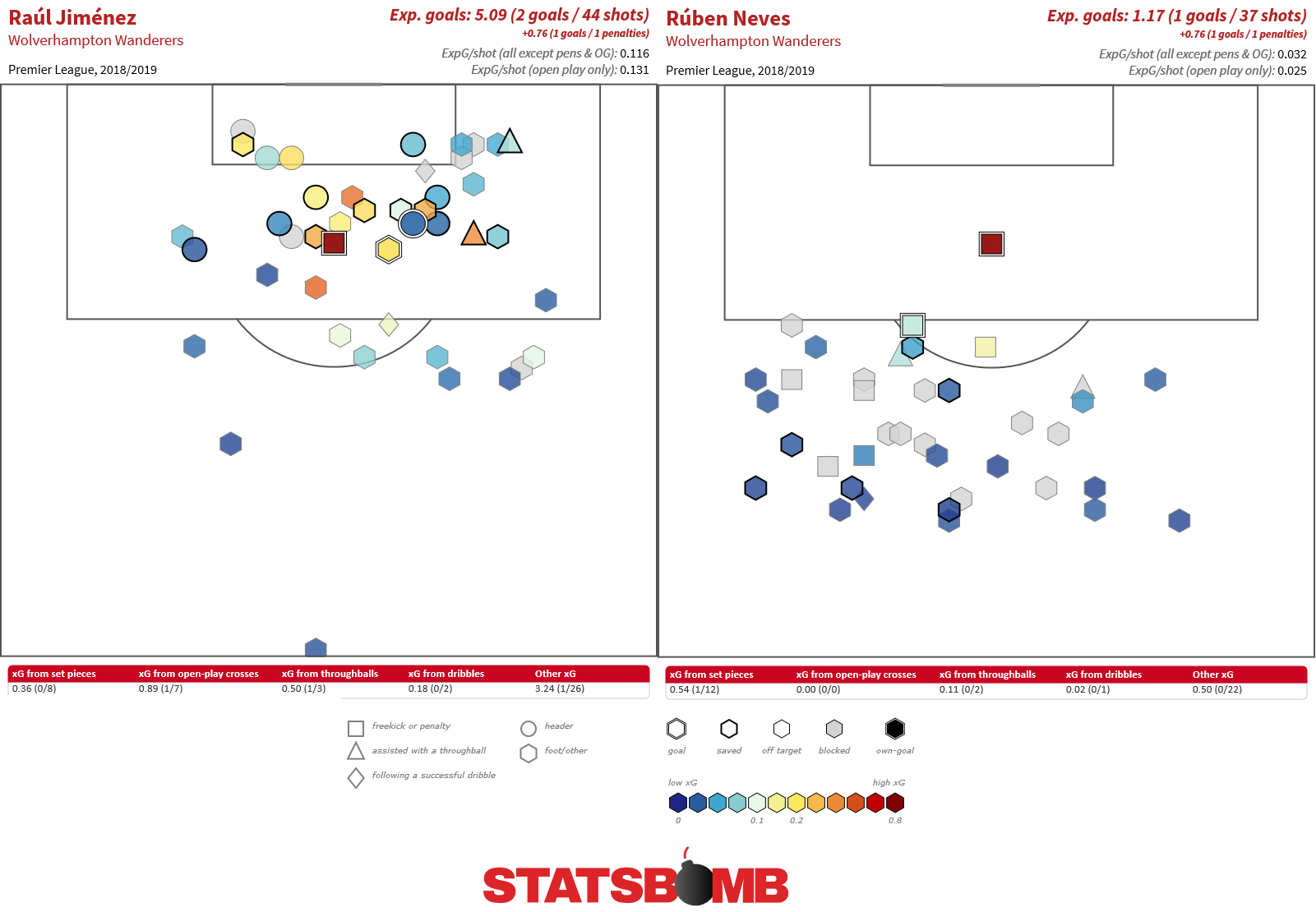

Being behind expected rates in attack can happen to any team in short bursts, but with the league now up to 14 games, there is the consideration of whether or not Wolves’ attackers are contributing enough overall or if this is an area of the team that may benefit from yet more investment. Raúl Jiménez has two goals (and a penalty) from an expectation of five. He was bought to fit into the team ahead of Léo Bonatini who hasn’t scored a league goal since December and having not started a league game this season looks well out of favour. It’s also surprising that none of the support cast has pitched in with goals, in particular, Diogo Jota, after his 17 league goals last season, but also Hélder Costa. Between the two of them, 1800 minutes for zero goals and zero assists is distinctly underwhelming while Traoré and Ivan Cavaleiro have made small contributions in fleeting minutes. Indeed, behind Jiménez nobody in the team who has played any significant time has any kind of notable goal expectation. Neves is the only regular starter other than Jiménez to average more than two shots per game, and the single shot he’s taken in the penalty area was a penalty. Indeed, feeding into a lack of creativity high up the pitch, 46% of shots they take from outside the box, enough to rank fifth most in the league. For chance creation, Jiménez leads the way for regular starters at around 0.22 expected goals assisted per game that feed into four assists. Jota is at 0.16, but the only other contributors here are the bench men. Overall, there's distinct room for improvement in the final third.

Defence

It’s possible the push-pull effect of running an effective defence has hampered Wolves’ attack. We’ve seen similar recently with Liverpool, who while fixing defensive issues have slowed down a smidgen up front. Unless you’re Man City, getting the best of both worlds appears to be extremely difficult to attain. Yet in adapting to the Premier League, Wolves’ defence appears to be very good. They have persisted with the three centre back formation they used in the Championship and Ryan Bennett, Conor Coady and Willy Boly have missed one start between them. They are the only team in the Premier League this season to have started consistently with three centre backs, Huddersfield have used it in the majority of their games but not all and a bunch of teams have tried it more occasionally. Perhaps the effect of Antonio Conte's Chelsea title winners is starting to wear off? After all fashions are fickle in football but Wolves and Nuno Espírito Santo are admirably committed to their method. Consistency in selection has extended to Moutinho and Neves, both ever present shielding in front of the defence. The core and strategy has been stable.

Wolves’ defensive focus can be initially identified by the opposition pass success rate, which at over 80% is third highest in the league. Easy to pass against? Not quite, move into their final third and Wolves rank tenth. They are happy to allow sterile possession but will put the squeeze on when you enter their defensive areas. Closer in it gets even better, they rank sixth for passes allowed in the box. The shots they allow are generally of low value. Their expected goals per shot against rate leads the league (around 0.07 per shot, reliable throughout the season), and is powered at least in part by the league's longest average distance for non-penalty shots. This kicks into other defensive indicators which all imply organisation and structure. When facing shots they have the most defenders between the shooter and the goal, and they also lead the league for the most defenders within the “cone” between the shooter and the goal. All told, Wolves’ expected goals against at 0.82 per game is better than everyone but Liverpool and Man City. Stern stuff.

There have been some noises around the form of Rui Patrício recently. He left his line for Aron Gunnarsson's goal against Cardiff and was perhaps easily beaten by Aaron Mooy's free kick last week, but at least in terms of general shot stopping across the season, he rates as bang on expectation via StatsBomb's model for shot outcomes.

What next?

As mentioned, Wolves’ short term future is not without tough games, and December may well stretch their resources. No team in the Premier League has used as few players--just 17 so far--and the squad looks as though it lacks depth. The first team is stable and capable, but should injuries bite at some point, the depth of the squad will be tested. They have already lost left back Jonny ahead of this busy period and 19 year old Rúben Vinagre has stepped in, while in midfield Leander Dendoncker has been unsighted in the league since a summer loan move and the promising 18 year old Morgan Gibbs-White has been empowered to play. Ahead of the January window, Wolves have a choice whether to bulk out their squad and continue building or run with a thin squad and wait for the summer. At least one attacking, creative option would appear a prudent play.

Regardless, this Wolves team is well capable of landing comfortably in mid-table, and with the right breaks and some life instilled into the attack, potentially more. Their current run of form looks like nothing more than a freakish blip and their defensive level should carry them a fairly long way. A combination of what is a well drilled and now fairly unique system for the league and decent talent levels should ensure that Wolves turn the corner soon enough. Ultimately, teams that beat Wolves during this part of the season may look back and be very thankful for their points.

Header picture courtesy of the Press Association