It used to be so simple.

A fullback’s job was to stop the opposition winger from putting crosses in. It was about providing support to the centre backs and maintaining a good shape without the ball, preventing spaces between the back four which the opposition could exploit. This understanding of the role began to be challenged in the 90s and especially into the twenty first century, with the left and right backs taking up more and more advanced positions to the point where some less enlightened commentators would say they are “really wingers”. That players in these positions used their deeper starting points to gain acceleration, and thus would be less suited to a classic wide midfield role, often seemed to be misunderstood.

Pep Guardiola, ever the tactical innovator, took this to extremes with Dani Alves at Barcelona, and the rest of football followed suit. But when he moved over to Bayern Munich, he surprised somewhat with his very different ideas about how a fullback should play. This was not in small part down to personnel, with Philipp Lahm and David Alaba both outstanding footballers, but generally better in possession than as outlets bombing down the flanks. So, the Catalan opted to play “inverted” fullbacks, who would effectively become central midfielders at times during the side’s build up play. It seemed at the time as though Guardiola, the man who so frequently set the tone for how football tactics would evolve, had invented the next big trend. In five years’ time, every top side in Europe would surely be employing the inverted fullback role to some extent.

But something else happened. The inverted fullback role exists, yes, but it’s hardly a dominant trend. The overlapping fullback, far from dying a slow death, has arguably hit new heights. Liverpool, with the 6 players in front of them generally very narrow and compact, have seen full backs Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold become the club’s top assist getters. The position, rather than adopting a new norm as it previously did, has become more diffuse than ever. By my count there are roughly four main types of fullback in the modern game. Let’s take a look at them.

The Overlapping Fullback

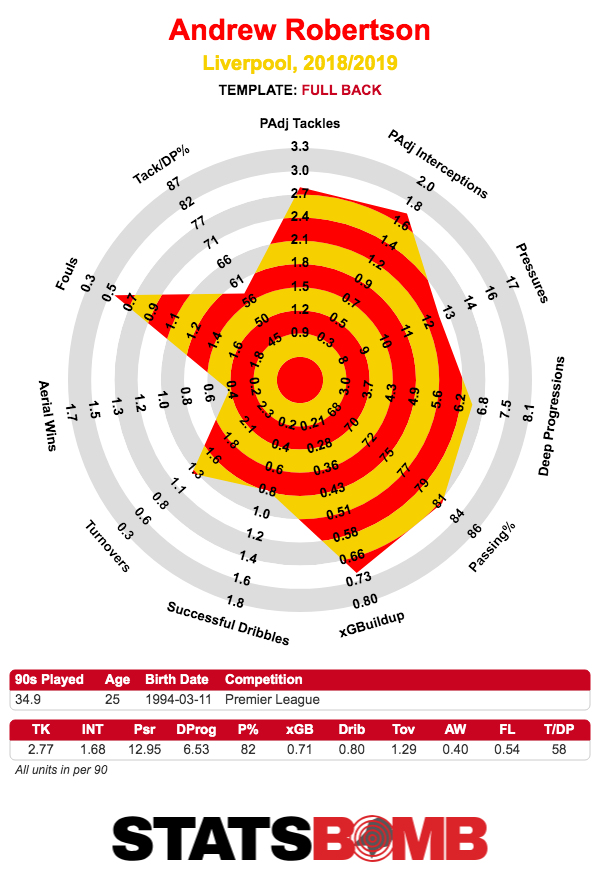

The dominant form of full back at top sides in the twenty first century continues to play a big part in football. As the sport became less about two conventional 4-4-2 systems battling against each other, wingers started adjusting to attack more central spaces, and fullbacks started to find themselves with more opportunities to break forward. And the prominence of these more narrow, often inverted, wingers made it important to get the width from somewhere, so fullbacks were bombing down the flank all the time. Thus what the role requires perhaps most of all is a high level of athleticism, allowing the player to contribute in wide areas of the final third while still getting back quick enough for defensive duties. This is difficult, and it leads to a lot of players getting exposed in this role, especially as they hit the later years of their career and can’t move as they once did. One player who does tick these boxes is the aforementioned Robertson, currently leading the Premier League in assists for fullbacks.

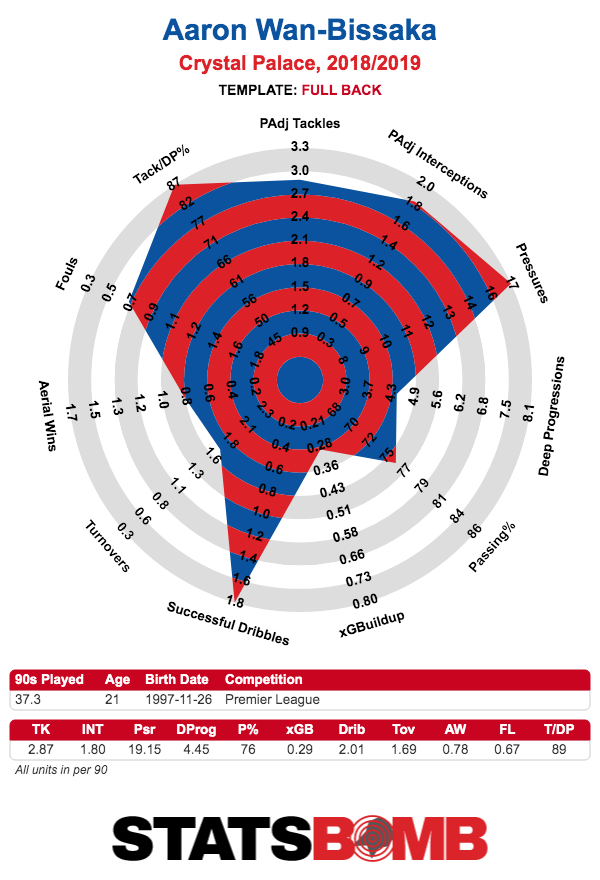

A thing that marks Robertson out among some others in the role is his relatively low volume of dribbles. The Scot generally offers an outlet without the ball, often arriving on the edge of the box, but rarely beats a man himself. This is in stark contrast to someone like Aaron Wan-Bissaka, who also likes to overlap, but interprets the role differently.

Wan-Bissaka is much more all action than Robertson, managing to get through a huge volume of defensive work while still pushing forward. But, as most fullbacks can’t do everything he does, there has to be some kind of strategy for preventing the side getting exposed when they push up the pitch. The most simple answer is to only have one fullback join the attack at a time, but this obviously limits the attacking options. For a while, a popular approach was to have the centre backs split wide, while the defensive midfielder drops in between and plays almost a sweeper-esque role. A more recent strategy can be seen at Liverpool, where the left sided central midfielder (most commonly James Milner or Naby Keita) drops into the backline to fill the space left by Robertson, while the right sided centre back moves across slightly to occupy the territory vacated by Alexander-Arnold. What is certainly the case is that, if your side wants to avoid easy counter attack situations for the opposition, there has to be some kind of attempt to cover the space wide of the centre backs when fullbacks overlap.

The Inverted Fullback

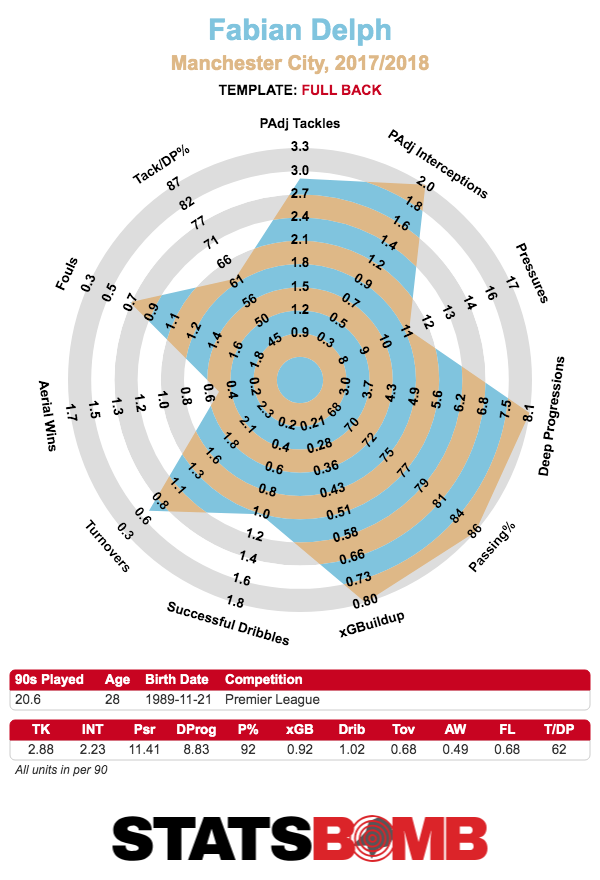

The Guardiola special. When the Catalan arrived at Bayern, not only did he inherit fullbacks more comfortable in possession than running down the flanks, but also a different kind of wide player than what he was used to at Barcelona. Previously he had operated with the likes of Thierry Henry, David Villa, Pedro, Alexis Sanchez and at times some bloke called Lionel Messi in the wide forward roles. These were all very much wide forwards, more comfortable taking up roles high and narrow, especially once Messi moved to the false nine role and created space for the “wingers” to attack in the centre. At Bayern, however, he inherited Franck Ribery and Arjen Robben who, yes, like to cut inside (we’ve all watched that one Robben move over and over), but start from wider positions, preferring to dribble more frequently. Thus it made sense to have the fullbacks take up narrower positions and help the team structure in other ways. Crucially, allowing them to fill the gaps in midfield helped prevent counter attacks from sides that defended deep, possibly the only weakness of Guardiola’s Barcelona team. After the mess that was the fullback positions in Guardiola’s first season at Manchester City, he began to implement the approach especially with Fabian Delph. A natural central midfielder, Delph was able to dovetail with Leroy Sane wonderfully, as Sane took up classic winger positions as a natural left footed player on the left, with Delph thus taking up narrower positions and coming inside to join the midfield. Delph occupying this more central position thus allowed central midfielders David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne to push higher up, in turn making sure Sane kept a wider role.

This season, with Delph’s injury, alternate options Oleksandr Zinchenko and Danilo not being of the same ability, and Raheem Sterling’s form on the left as more of an inverted wide forward, Guardiola has been more flexible in his left back approach. Benjamin Mendy has often been deployed as an overlapping fullback. But there is another question of Kyle Walker’s role at right back, which brings us to…

The Auxiliary Centre Back

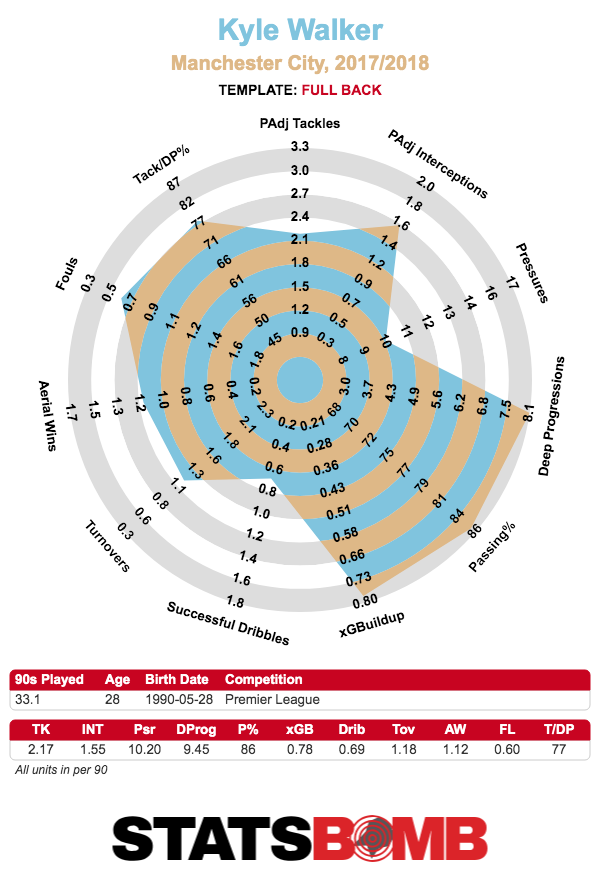

During last summer’s World Cup, much fuss was made over England manager Gareth Southgate’s decision to field Kyle Walker as a right sided centre back in a 3-5-2 system. “He’s playing one of the best right backs in the world out of position at centre back”, said many. But anyone who had watched Manchester City closely in the preceding season would have seen that it was a role largely in keeping with what he was already doing. As Delph would move inside on the left to at times form a double pivot with defensive midfielder Fernandinho, on the other side, Walker would shuffle along to become a third centre back, keeping Guardiola’s preferred 3-2 defensive structure. This doesn’t mean Walker interprets the role as a purely defensive one, far from it, as he really becomes an extreme example of a ball playing centre back at times.

The rise of back three systems, and increasing use of formations that oscillate between three and four defenders, has blurred the lines between fullback and centre back. A player like Cesar Azpilicueta, a natural fullback if ever there was one, was deployed as a right sided centre back under Antonio Conte’s 3-4-3 system. It was ultimately only a slight shift from his naturally defensive focused fullback game. As we are in an era where formations are particularly fluid, this kind of not-quite-one-not-quite-the-other role is common. But sometimes, systems are not very fluid at all, and make use of…

The Classic Defensive Fullback

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. As much as many teams like to play fluid, interchanging football, there’s still a time and place for teams primarily trying to keep a compact defensive shape, and if said shape involves two banks of four, then you need classic defensive fullbacks. Take Burnley’s Phil Bardsley, for example.

Everyone knows how Sean Dyche likes his team to play. Burnley operate an at times aggressive but always compact 4-4-2 system. That means that a lot of the fullbacks’ work doesn’t show up in the numbers, with maintaining a good position being the most important thing. Being able to do basic defensive tasks such as dominating in the air are also useful, so it’s not shocking that all the radar shows him doing is winning aerial duels and not giving the ball away. If Burnley were to try and do anything more expansive, one imagines Bardsley would be continually exposed, but as it is, he does what is required of him and nothing more.

The fullback position has never been more diverse in terms of how it can be interpreted. Once largely understood in the same way, it gradually became a question of how attacking or defensive a side wanted to be. Now, however, it can mean many different things to many different players and systems. Just like every other position on the pitch.