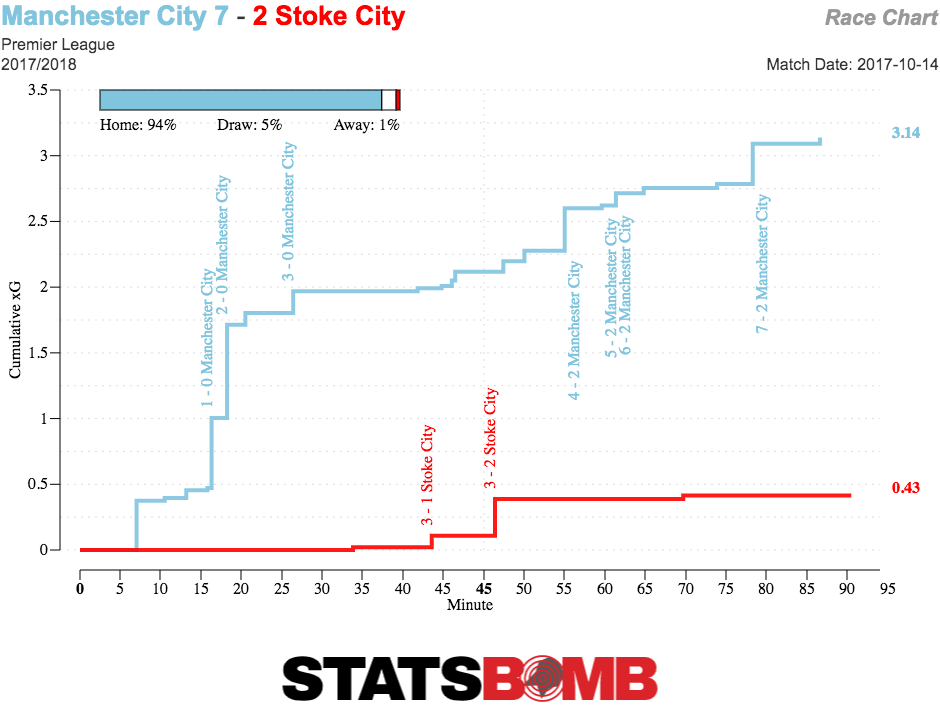

There won't be much Stoke discussion in this one, but I don’t think their fans will be particularly upset about that. Kevin De Bruyne or David Silva picks up the ball in a central area just outside the box. He slides it out wide to Raheem Sterling or Leroy Sané, who then plays in a low cross for someone to score a tap in on the cutback. Has any single goal been scored more times in the history of the Premier League? They added more variance to their game in the years since, but 2017–18 saw Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City take this approach to extremes, working everything around creating these sequences.  The 7–2 victory over Stoke was, somehow for this side, not their most impressive result. But it was certainly notable as it saw several changes to the side, especially in light of Benjamin Mendy’s injury, and really set the template for the rest of the season. Let’s break it down a little:

The 7–2 victory over Stoke was, somehow for this side, not their most impressive result. But it was certainly notable as it saw several changes to the side, especially in light of Benjamin Mendy’s injury, and really set the template for the rest of the season. Let’s break it down a little:

Fullback/Winger combinations

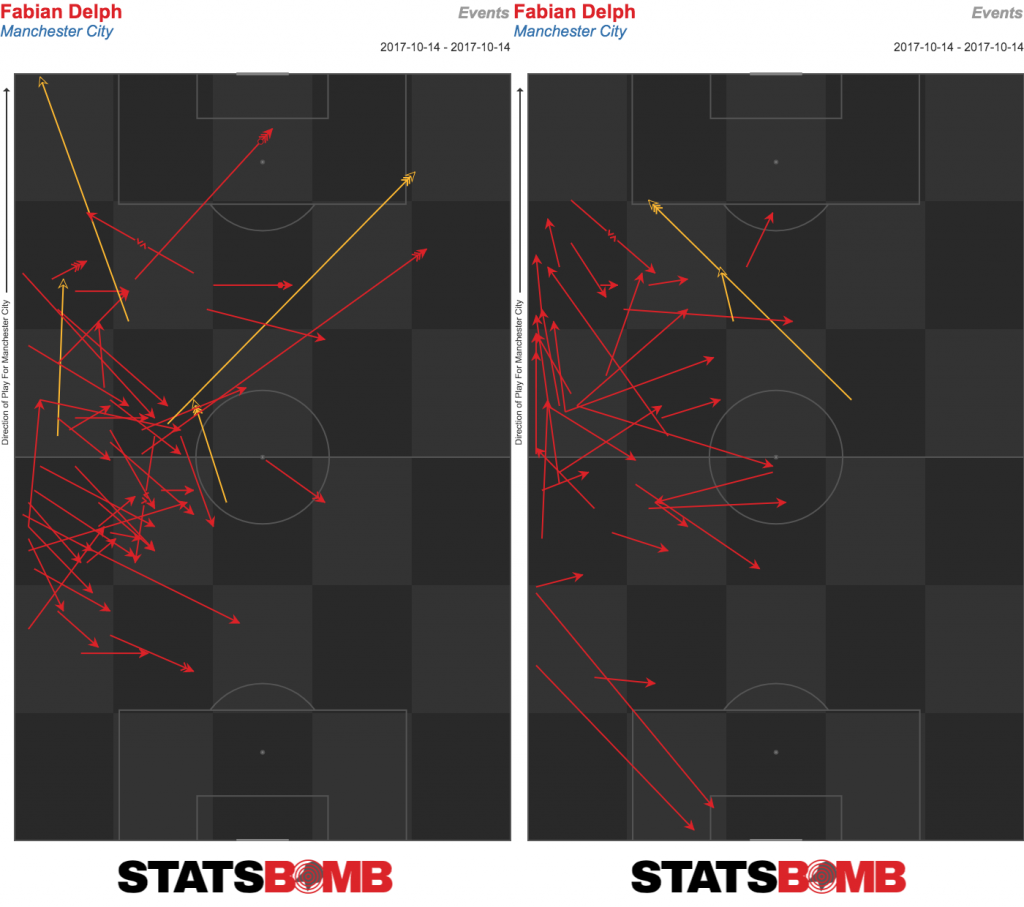

This is the thing that really stood out to me at the time as the difference between City and other top sides, and it wasn’t even the plan. In the early weeks of 2017–18, City favoured a back three system with Benjamin Mendy as a left wing-back, or as a left back in a four at times. He’s much more of a conventional attacking fullback, similar to the way Guardiola used Dani Alves at Barcelona but on the opposite flank. That all blew up when he suffered a cruel injury, and a rethink was needed. The 3-5-2ish system was dead and buried in favour of the more conventional 4-3-3ish shape (look, it’s Pep, you can’t just throw out some numbers and describe a formation here). Kyle Walker remained at right back, while Fabian Delph came in on the left.  Delph was a fullback very much in the mould of Guardiola’s Bayern side, where Philipp Lahm and David Alaba would invert and become central midfielders at times. Delph doesn't come close to their ability, but he does have interesting skills. He was one of the most two-footed players in the league that season, making 63% of his passes with his left foot (the vast majority lean very much toward a preferred foot). The graphic below from the Stoke game shows just how comfortable he was switching between passing with his left foot (left) and his right foot (right). You can barely tell that he’s left-footed.

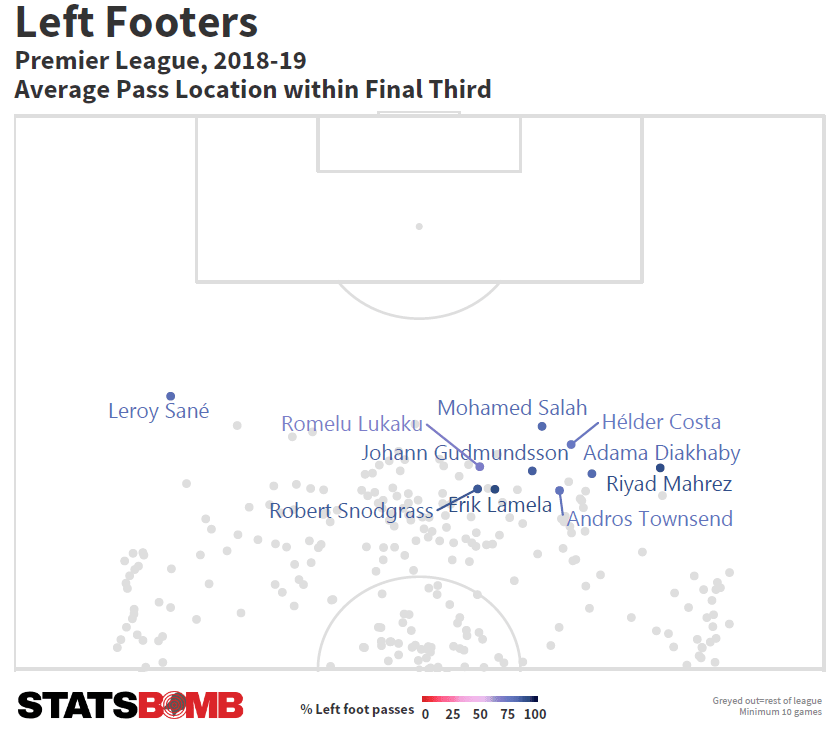

Delph was a fullback very much in the mould of Guardiola’s Bayern side, where Philipp Lahm and David Alaba would invert and become central midfielders at times. Delph doesn't come close to their ability, but he does have interesting skills. He was one of the most two-footed players in the league that season, making 63% of his passes with his left foot (the vast majority lean very much toward a preferred foot). The graphic below from the Stoke game shows just how comfortable he was switching between passing with his left foot (left) and his right foot (right). You can barely tell that he’s left-footed.  Though he and Sterling sometimes switched places, Delph generally had Sané in front of him. This combination felt so perfect it's almost impossible to believe they just stumbled onto it. As James Yorke wrote for StatsBomb previously, Sané is just about the only true left-footed left winger at the top level in England. This graphic of where left footers pass the ball is from the following season, but it tells the same story of how rare Sané’s skillset is. With Delph underlapping and Sané taking a very wide role, City had the entire left flank covered. It allowed Sané to consistently play in those low crosses from wide, knowing Delph would fill the more narrow space behind him.

Though he and Sterling sometimes switched places, Delph generally had Sané in front of him. This combination felt so perfect it's almost impossible to believe they just stumbled onto it. As James Yorke wrote for StatsBomb previously, Sané is just about the only true left-footed left winger at the top level in England. This graphic of where left footers pass the ball is from the following season, but it tells the same story of how rare Sané’s skillset is. With Delph underlapping and Sané taking a very wide role, City had the entire left flank covered. It allowed Sané to consistently play in those low crosses from wide, knowing Delph would fill the more narrow space behind him.  On the other side, Walker and Sterling played a little more straightforward. Walker generally took on a more reserved role, often becoming a third centre back at times (which famously became his main position for England). In this game, though, he was allowed to effectively swap with Sterling at times, becoming the more advanced attacker making runs into the box. Both players are mobile right footers, so they have much more of a skillset overlap than Delph and Sané. This could have become too predictable, but their ability to switch against Stoke made things very flexible. The system ensured that City always had someone at the byline on each flank waiting, without pushing the fullbacks too far forward all the time.

On the other side, Walker and Sterling played a little more straightforward. Walker generally took on a more reserved role, often becoming a third centre back at times (which famously became his main position for England). In this game, though, he was allowed to effectively swap with Sterling at times, becoming the more advanced attacker making runs into the box. Both players are mobile right footers, so they have much more of a skillset overlap than Delph and Sané. This could have become too predictable, but their ability to switch against Stoke made things very flexible. The system ensured that City always had someone at the byline on each flank waiting, without pushing the fullbacks too far forward all the time.

Free Eights

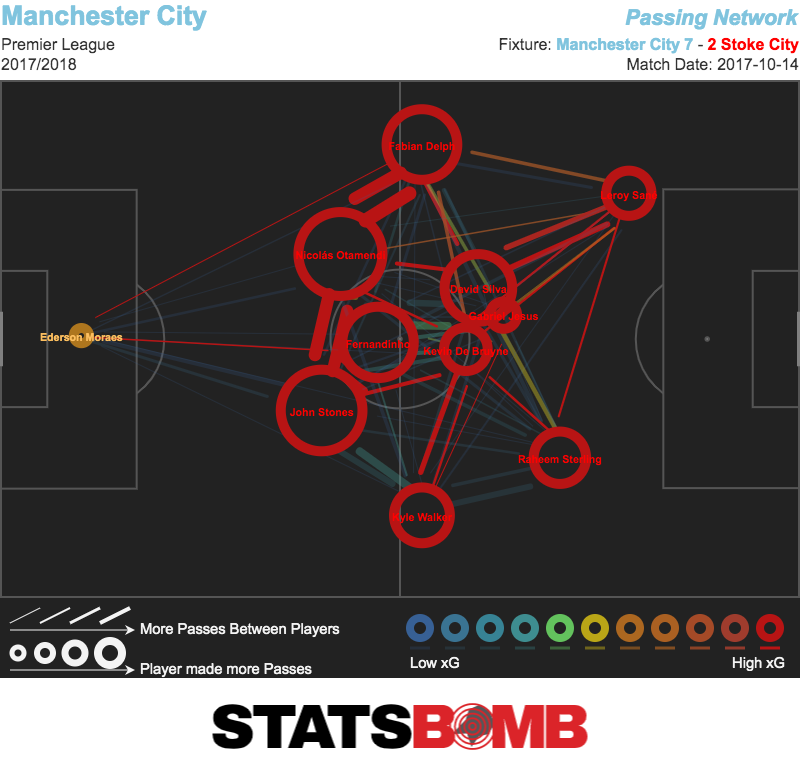

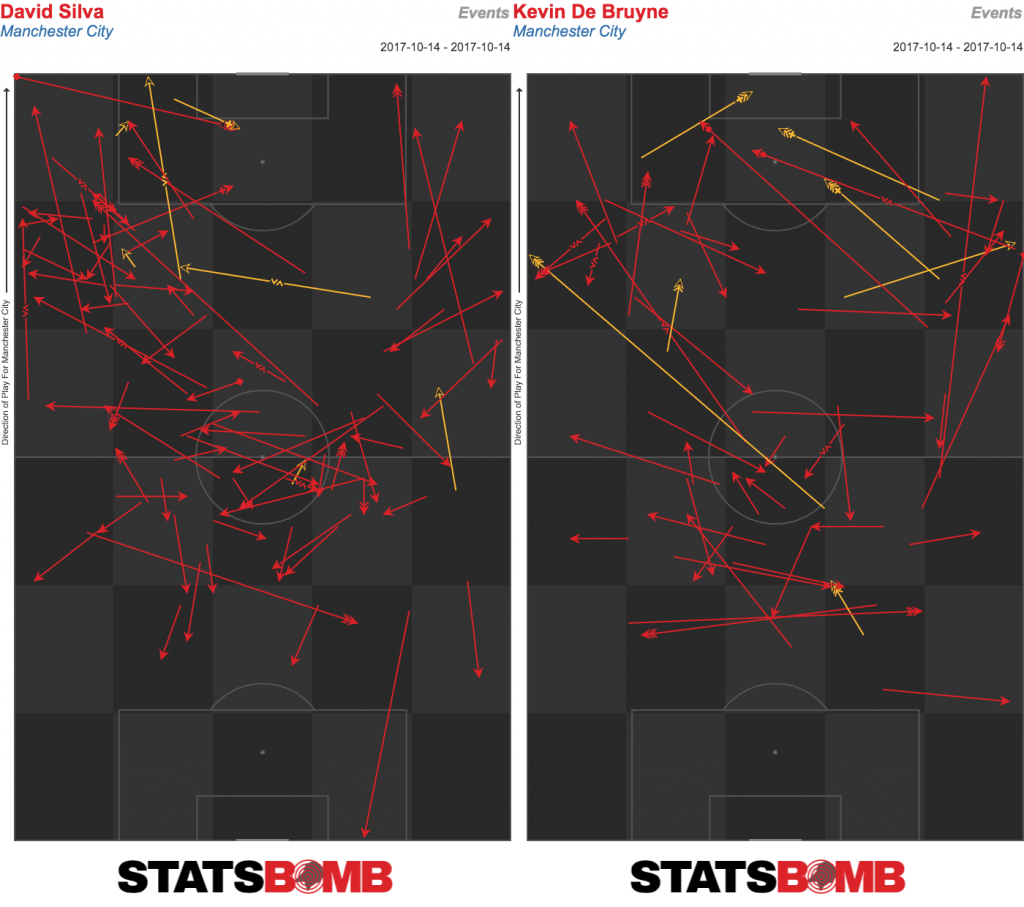

Ok, so we have the wingers in those wide areas ready to deliver the cutbacks into the box. But how do we feed them the ball? That, of course, revolves around Kevin De Bruyne and David Silva. De Bruyne would broadly play on the right of the midfield three and Silva on the left, though they could frequently switch. These two were about the freest eights you could find, given licence to push right up and join the attack, threading passes in advanced areas, secure in the knowledge that Fernandinho and an underlapping Fabian Delph had them covered. While there's been so much discussion of De Bruyne and Silva as a pair, their differences aren’t often appreciated. Here’s Silva's (left) and De Bruyne's (right) passes against Stoke:  Silva is the more involved, successfully completing 76 passes to De Bruyne’s 45. He makes a lot more short passes in the final third, linking up on the left as he does. De Bruyne, on the other hand, is more direct, pinging more long balls straight to the attackers from deep and taking more risks. No Guardiola side ever had a midfielder so willing to risk losing the ball like De Bruyne, and he’s exactly what makes City different to his previous teams. The Catalan's sides have always been the best around at covering space, with this City team certainly no exception. As Sterling and Sané covered the widest areas, with De Bruyne and Silva in the half-spaces and Jesus (here, but frequently Sergio Agüero) as the striker, it was impossible for opposing sides to get out of their own third even when they won the ball.

Silva is the more involved, successfully completing 76 passes to De Bruyne’s 45. He makes a lot more short passes in the final third, linking up on the left as he does. De Bruyne, on the other hand, is more direct, pinging more long balls straight to the attackers from deep and taking more risks. No Guardiola side ever had a midfielder so willing to risk losing the ball like De Bruyne, and he’s exactly what makes City different to his previous teams. The Catalan's sides have always been the best around at covering space, with this City team certainly no exception. As Sterling and Sané covered the widest areas, with De Bruyne and Silva in the half-spaces and Jesus (here, but frequently Sergio Agüero) as the striker, it was impossible for opposing sides to get out of their own third even when they won the ball.

Subsequent Years

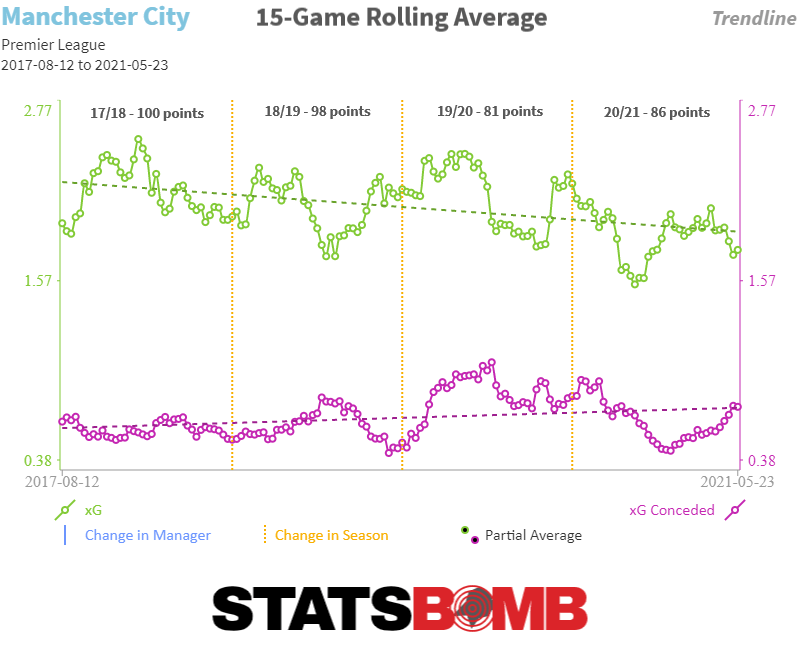

In pure numbers terms, City haven’t seen much of a drop off since their “best” season.  Their play is stylistically different, though, and feels a little less unique. Bernardo Silva, then generally a substitute, put up such good form that he had to start more often. At times he's in central midfield, but Guardiola primarily favours him cutting in from the right. Riyad Mahrez, the biggest attacking addition in the years since, also favours cutting in from the right onto his weapon of a left foot. That, combined with the ever-improving Sterling’s preference for playing on the left, has seen Guardiola move to a more common inverted winger format. Delph’s slight decline and departure also hastened this move. Sané hasn’t become a lesser player, but Guardiola’s increased disinterest in him may be partly driven by the lack of an ideal partner like Delph. And then of course a catastrophic injury took the winger out of the picture altogether this season. The patterns are different now. City often play with a true double pivot and an attacking quartet rather than a front five. It’s changed. It’s not necessarily bad, but there’s something about the 2017–18 incarnation that feels a little elusive.

Their play is stylistically different, though, and feels a little less unique. Bernardo Silva, then generally a substitute, put up such good form that he had to start more often. At times he's in central midfield, but Guardiola primarily favours him cutting in from the right. Riyad Mahrez, the biggest attacking addition in the years since, also favours cutting in from the right onto his weapon of a left foot. That, combined with the ever-improving Sterling’s preference for playing on the left, has seen Guardiola move to a more common inverted winger format. Delph’s slight decline and departure also hastened this move. Sané hasn’t become a lesser player, but Guardiola’s increased disinterest in him may be partly driven by the lack of an ideal partner like Delph. And then of course a catastrophic injury took the winger out of the picture altogether this season. The patterns are different now. City often play with a true double pivot and an attacking quartet rather than a front five. It’s changed. It’s not necessarily bad, but there’s something about the 2017–18 incarnation that feels a little elusive.