Newcastle's metrics last season were bad enough to immediately make them one of the default favourites for relegation this time around. They finished 13th with a points total that was within the same range as the two previous years, but other top-line and underlying numbers revealed notable decline.

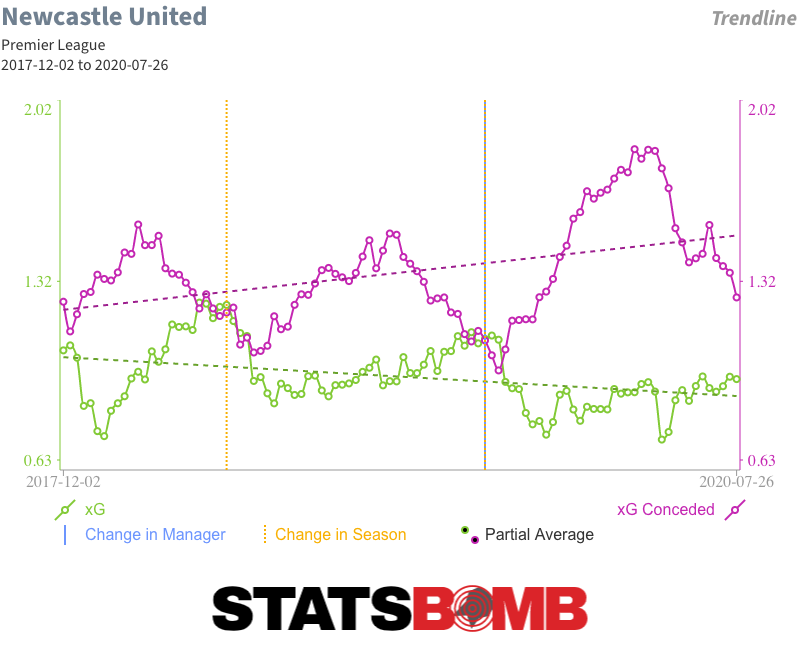

Steve Bruce’s side scored slightly fewer goals than in either of those campaigns while conceding 10 more, leading to a goal difference of -20 compared to those of -6 and -8 in the preceding seasons. That was mirrored in the metrics: the attack got marginally worse; the defence, dramatically so.

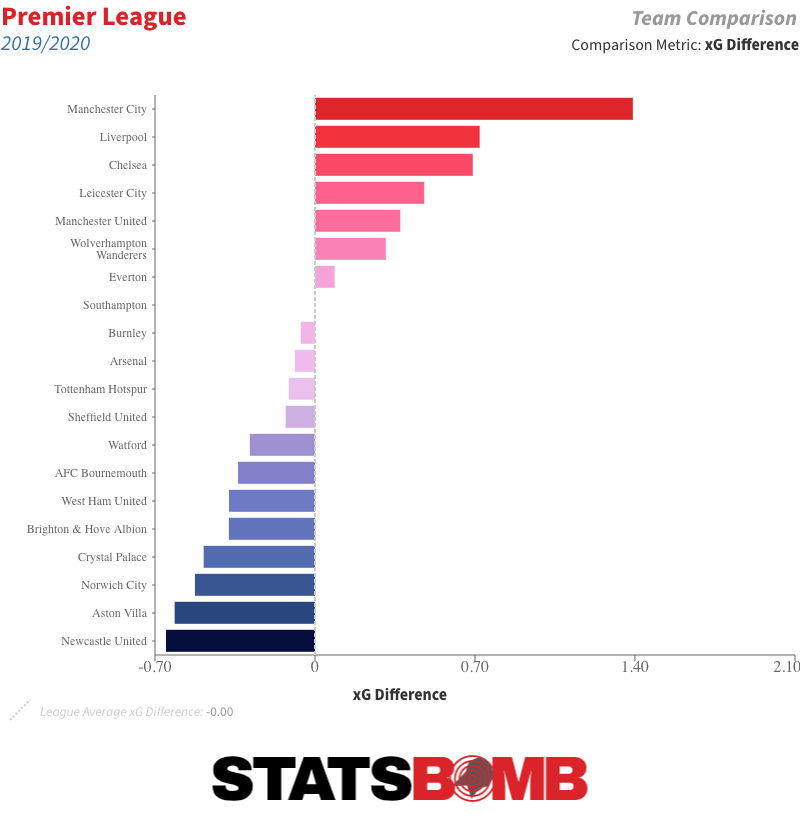

In combination, the second-worst attack and third-worst defence in the league gave them its worst expected goal (xG) difference.

So how did they stay up? Not only that, but relatively comfortably so? Two things happened: Newcastle overperformed their metrics to a greater degree than teams like Aston Villa and West Ham who finished below them, while the three relegated sides all underperformed theirs fairly significantly. Take either away and the Magpies would have been right on the cusp of relegation. Take both away, and it would have been a near certainty.

The defence falling away upset the delicate balance of the Rafael Benítez years. Under him, Newcastle were comfortably below average in attack but had the seventh best defence in the league in both 2017-18 and 2018-19. That kept them within respectable distance of a par goal difference and the mid-table safety that comes with it.

The scale of the defensive deterioration was impressive, particularly given the relative lack of squad turnover. In addition to the aforementioned 10-goal negative swing including penalties, Newcastle were 14 non-penalty goals and 9.24 xG worse off that the previous season.

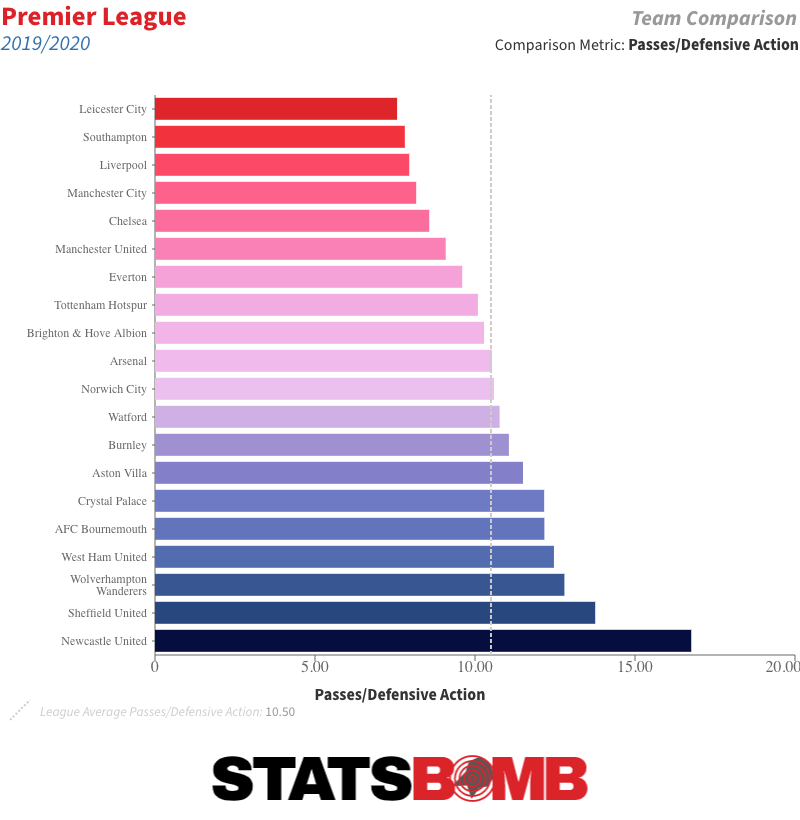

Under Benítez, Newcastle always defended a fair amount deeper and less proactively than the league average, but last season they just completely retreated into their shell. They defended deeper than any other side in the division and became almost comically passive.

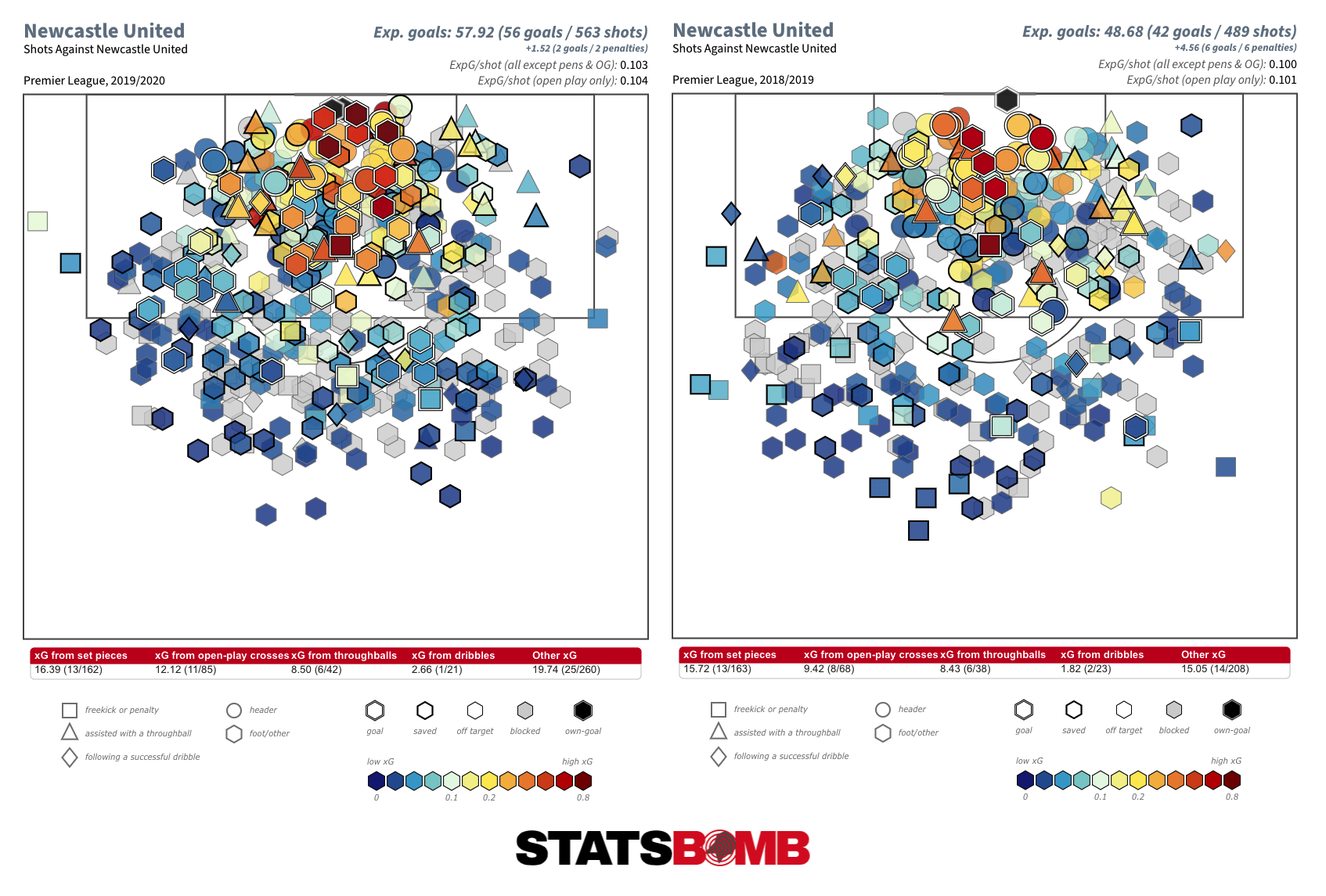

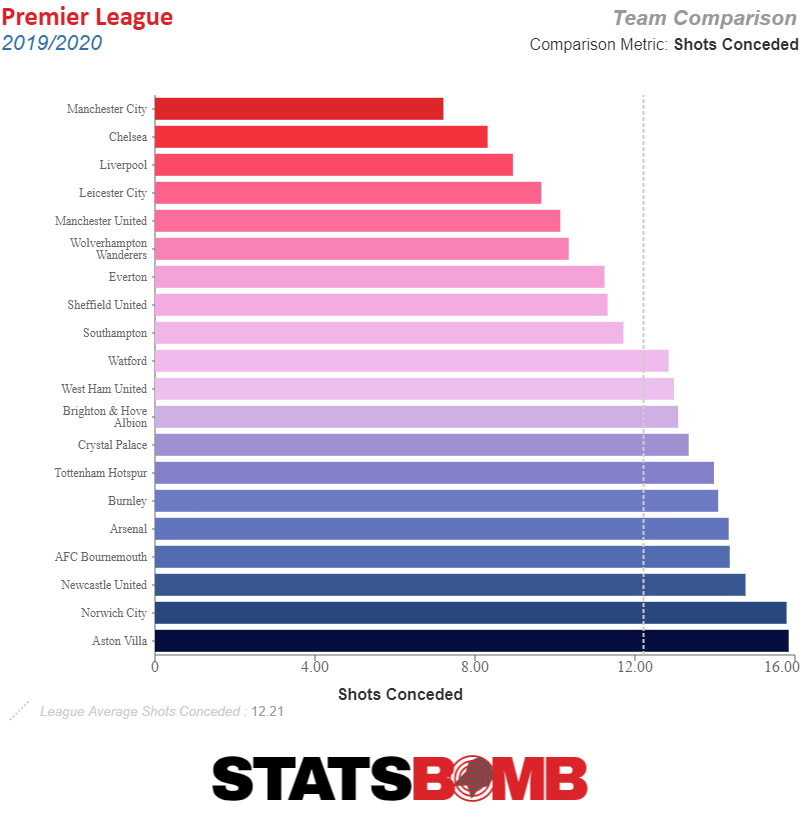

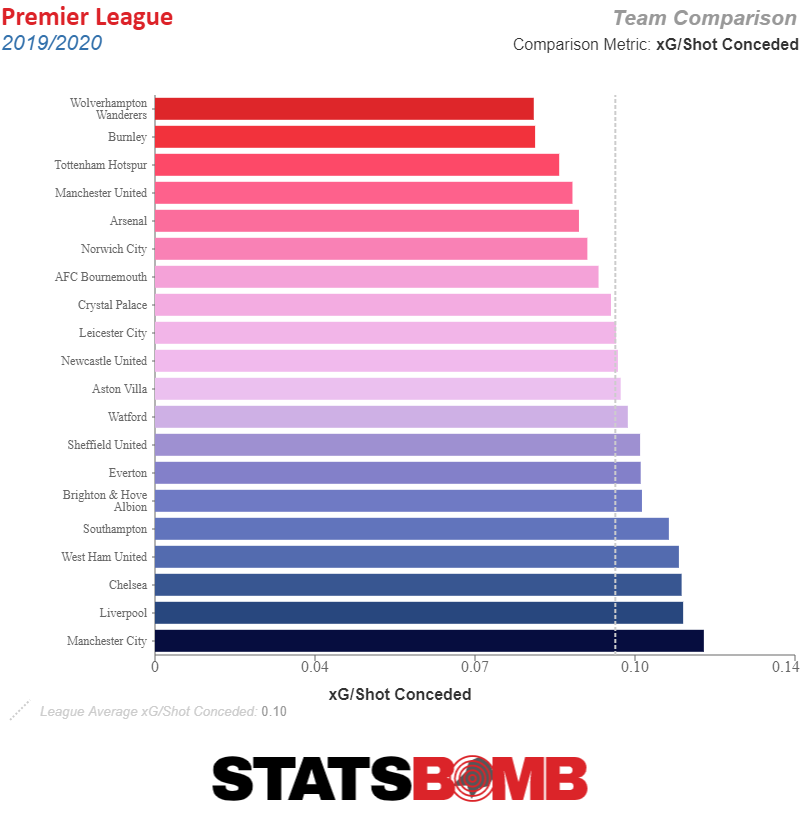

If Bruce’s idea was to restrict opposition shot quality by getting large numbers of players behind the ball then it really didn’t work out. Newcastle conceded around two more shots per match than the previous season (14.76, third worst in the league) without any change in the average quality of them.

It also doesn’t say much for his work on the training ground that Newcastle were genuinely bad at defending set pieces. Only two teams conceded more than their 13 goals from those situations, while their xG conceded of 16 was pretty comfortably the worst in the division. It wasn’t simply a case of Newcastle giving up a lot of set pieces, and consequently a lot of chances for opponents to create chances from them, due to their deep stance. They were about average in that, and anyway they were also the worst side in the league in terms of xG per set piece conceded.

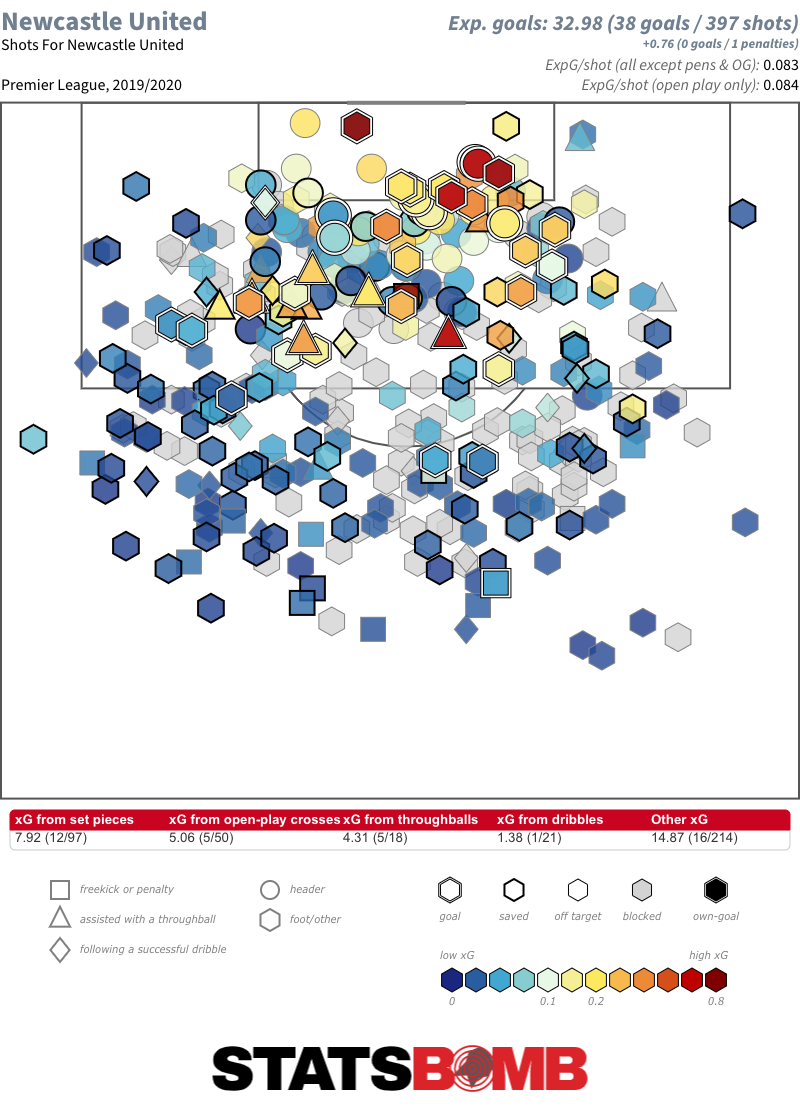

The defence may have been the area of the team that declined most season-on-season, but Newcastle’s deficiencies in attack were no less alarming. A five-goal positive swing versus their expected numbers just about got them up to an average of one goal per match, but this was a team who really struggled to work the ball into good shooting positions.

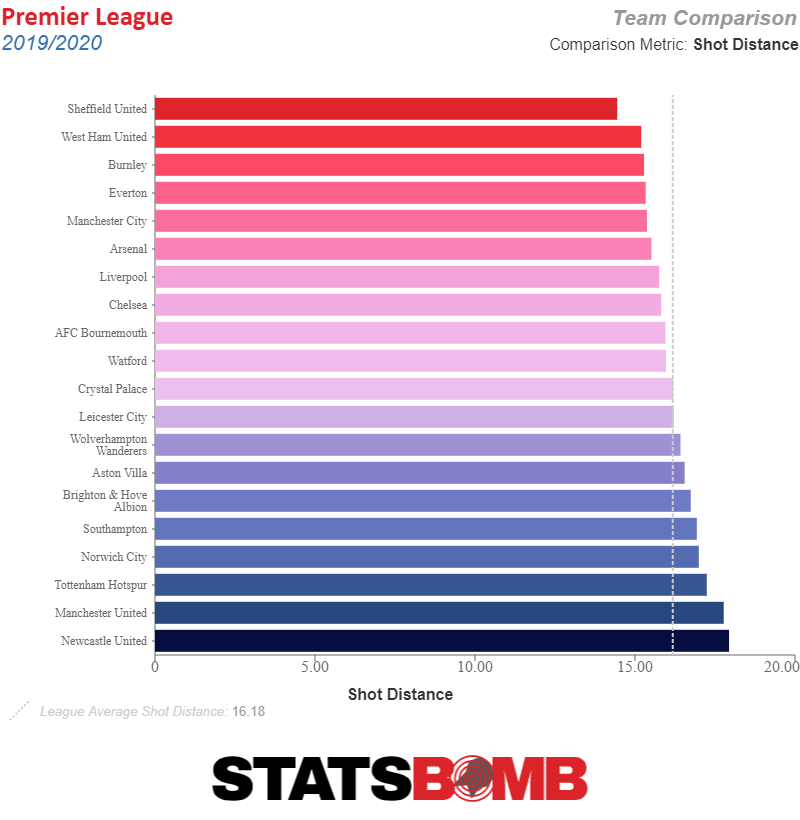

The Magpies took a below-average number of shots (10.45 per match), and those they did take were of the lowest average quality in the league. They took their shots from further out and got off less efforts from inside the area than any other team. Whenever they did shoot, they had more opposition defenders between shooter and goal than any other side.

There was a broader problem there. Newcastle lacked a reliable means of progressing the ball into advanced areas. No team in the league completed less passes within 20 metres of the opposition goal. Aside from Matt Ritchie, who missed just under the half the season through injury, no one else was able to successfully move the ball into the penalty area with even a semblance of regularity.

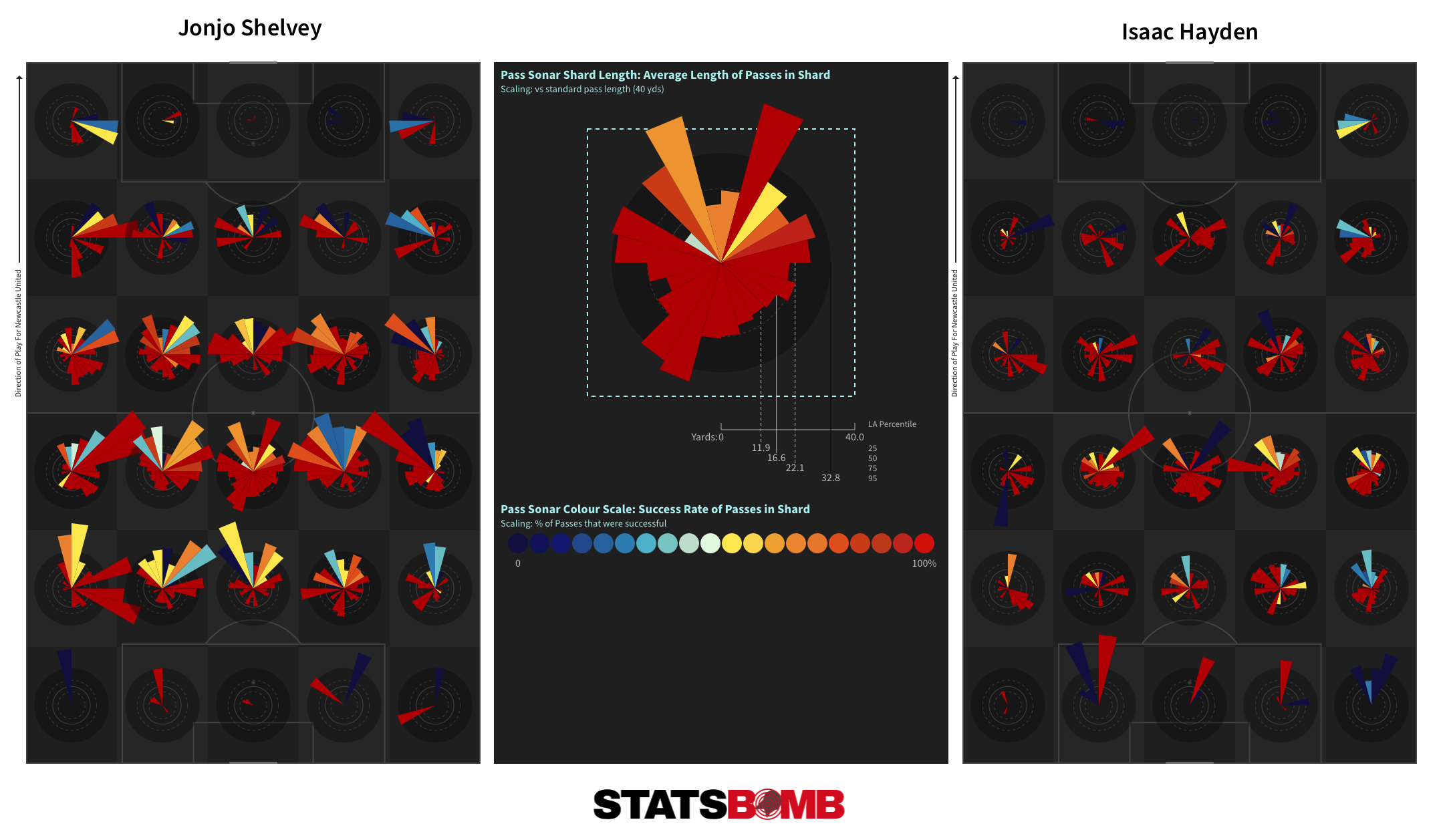

Newcastle were quite direct in initially advancing the ball. For the third season in a row, Jonjo Shelvey's attempted and completed passes were of a longer average length than those of any other Premier League midfielder who saw at least 900 minutes of action. That was in neat contrast to his fellow central midfielder Isaac Hayden, whose passing was demonstrably shorter and more conservative.

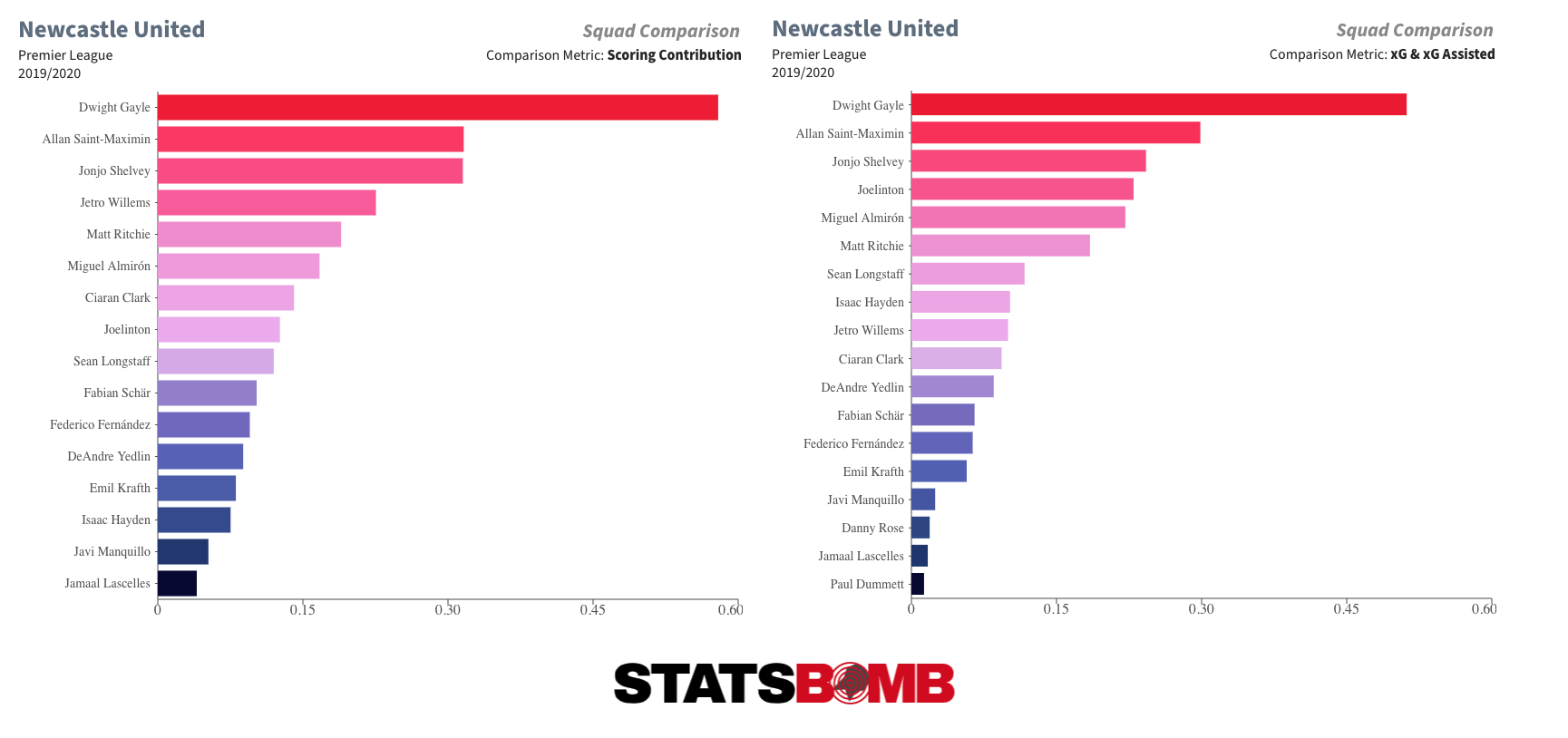

Along with Miguel Almirón, new arrivals Allan Saint-Maximin and Joelinton were Shelvey’s main targets from deeper areas. Saint-Maximin was fun to watch and also provided better end product than the rest of Newcastle’s regular attackers. Only Dwight Gayle, who only saw just over 900 minutes of action due to a recurring calf problem, bettered him in terms of both expected and actual goal and assist output per 90 minutes.

On a season total level, Shelvey was the top scorer with just six goals. No attackers got close to the marks set by the departed Ayoze Pérez (12) and Salomón Rondón (11) the season previous. Gayle and Almirón were the first attackers on the list with four. Joelinton grabbed just two from a marginally more encouraging 4.89 xG, although even that worked out to just 0.15 xG per 90.

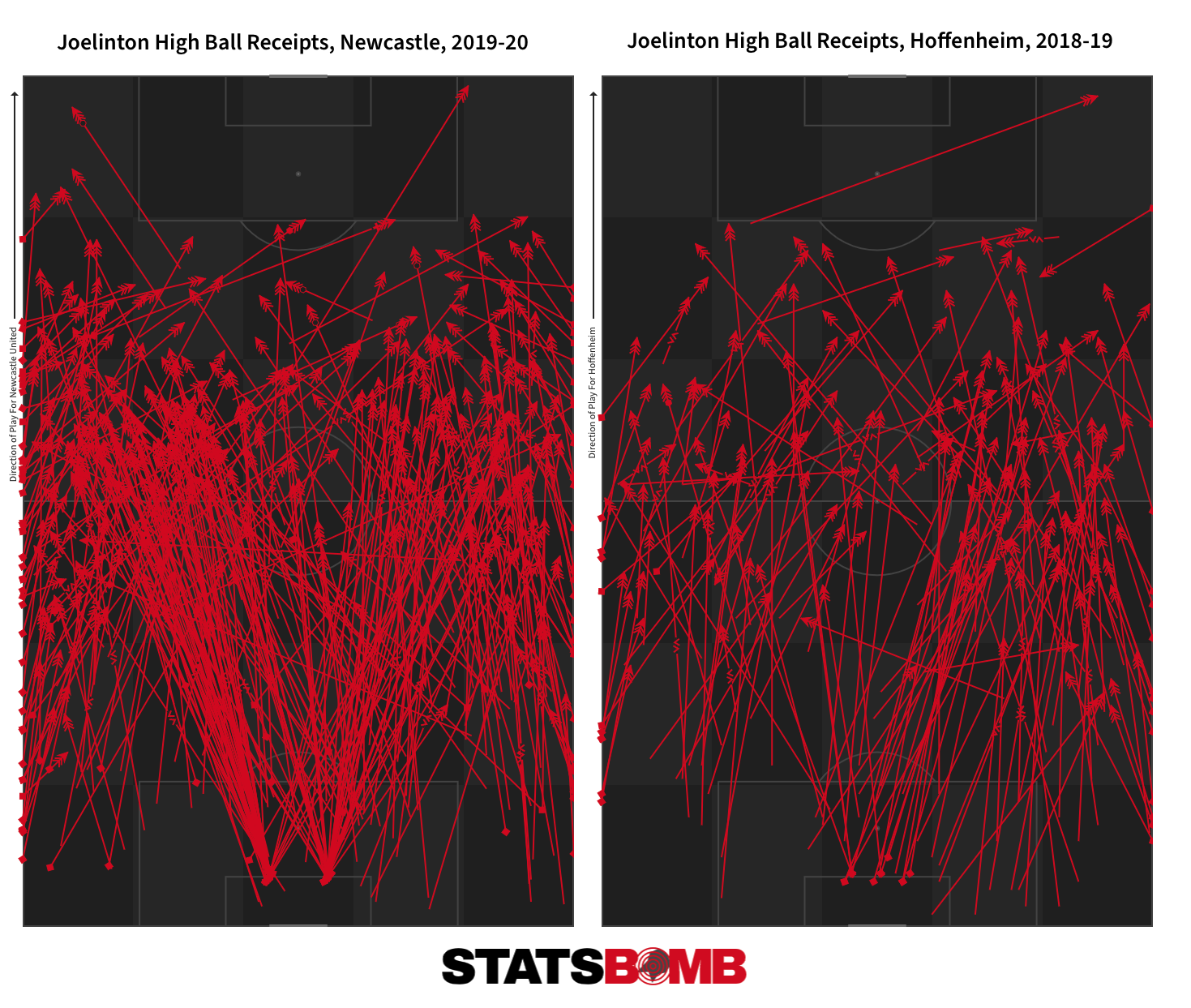

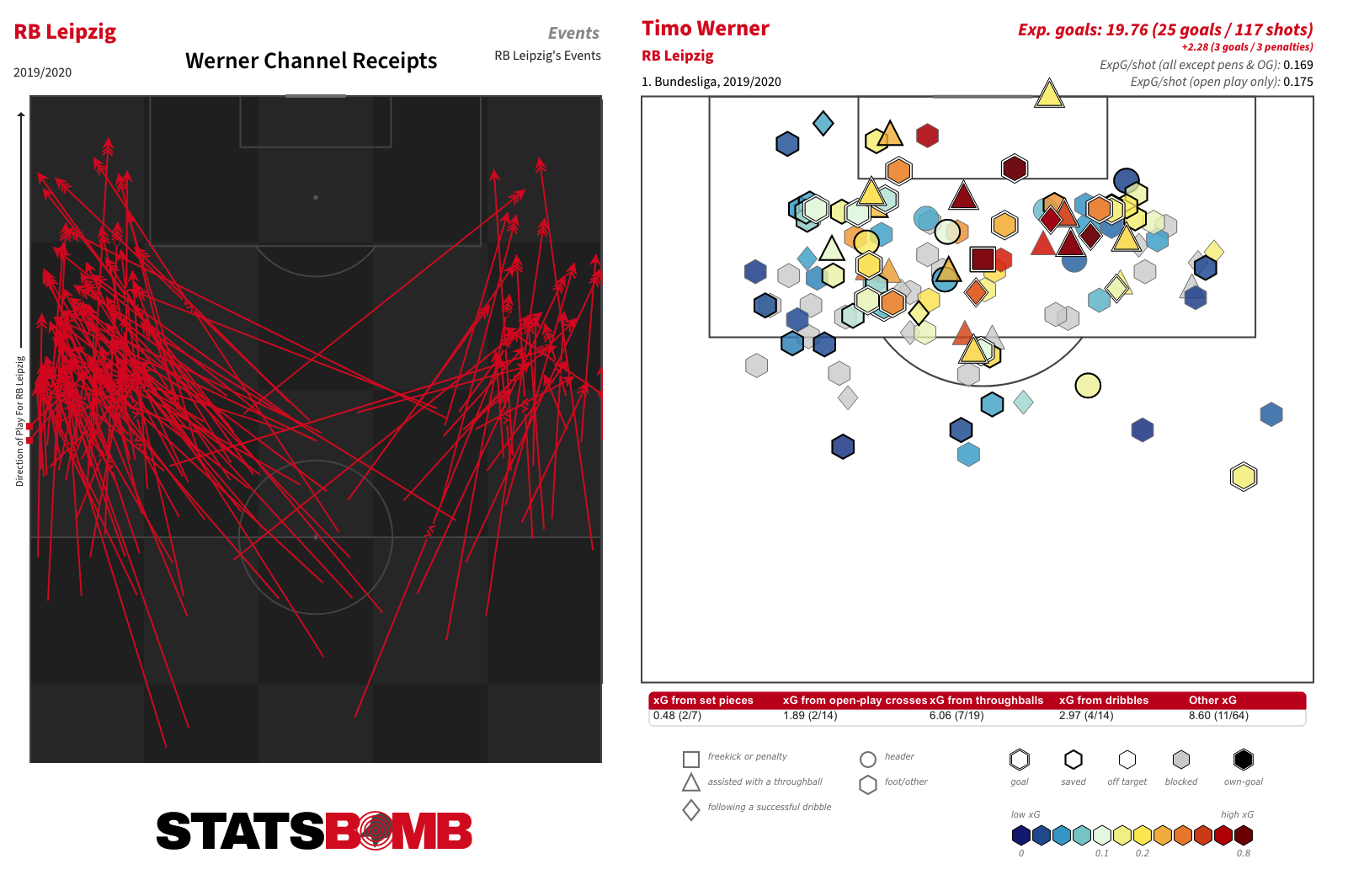

The Brazilian striker seems to have become somewhat of a figure of fun in certain quarters, but he was rather set up to fail following his £40 million move from Hoffenheim. Not only did the fee appear inflated, but there was little evidence he was capable of playing the role Newcastle required of him. He was plucked from a high-pressing, attack-minded team with options all around him and plonked straight into the role of battering ram striker on a deep-lying, defensive-minded side with huge spaces between teammates.

If goals were what Newcastle wanted, he wasn't really the man either. He was, after all, only a one-in-three goalscorer on an attacking team in the most open of the big five European leagues. He was more roving facilitator than main striker, receiving, combining, carrying the ball forward and offering a solid combination of shot and creative output. Ishak Belfodil and Andrej Kramarić were the main goal-getters. At Newcastle, shorn of close collaborators and subjected to a bombardment of aerial service (46.81% of the passes he received were high balls, compared to just 24.36% at Hoffenheim), he looked very much out of place.

Joelinton was never going to be a direct stylistic replacement for Rondón, and his signing asks questions of the recruitment department or a huge disconnect between them and the coaching staff.

The club had made just a couple of low-profile free transfer signings ahead of the new season at time of writing, with goalkeeper Mark Gillespie and winger Jeff Hendrick coming in from Motherwell and Burnley respectively. There is talk of strong interest in the Bournemouth pair of Ryan Fraser and Callum Wilson, which would at least refresh things a little in attack, even though it is likely to take a bit more than that to avoid a struggle against the drop.

For months, hopes rested on the promise of a Saudi-backed takeover that would have brought with it a huge injection of funds and the arrival of high-profile coaching and playing staff. Regardless of where you stand on the Premier League’s decision to deny it, it was undeniably a much more enticing prospect than the alternative: another season of Bruce and the gang.

Relying on enough other teams to be worse and/or more unlucky than you it not a viable long-term strategy for remaining in the Premier League. Something has to change in comparison to last season, but it is genuinely hard to see where that change and improvement might come from within the current coaching and playing staff, certainly under the stewardship of the current ownership. If it doesn’t, Newcastle may just sleep walk their way to relegation.

If you're a club, media or gambling entity and want to know more about what StatsBomb can do for you, please contact us at Sales@StatsBomb.com We also provide education in this area, so if this taste of football analytics sparked interest, check out our Introduction to Football Analytics course Follow us on twitter in English and Spanish and also on LinkedIn

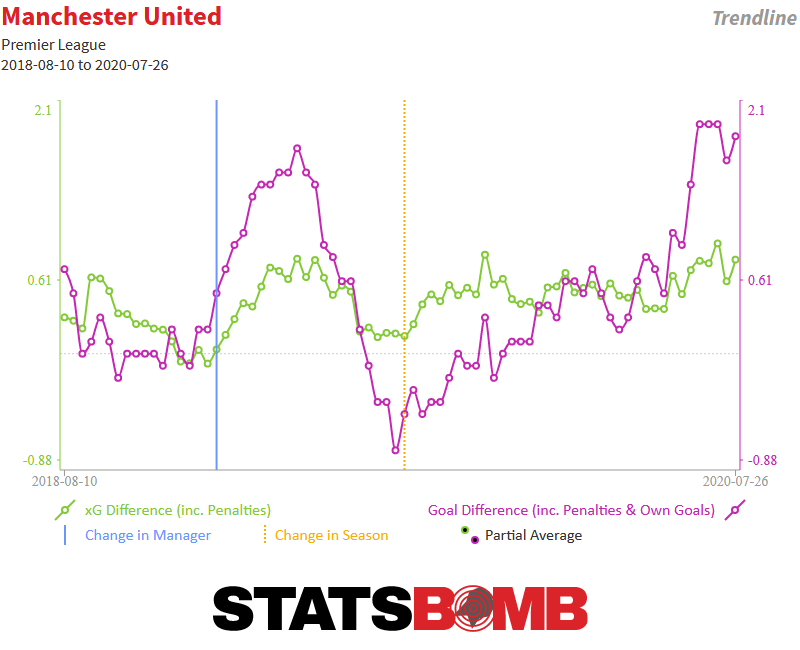

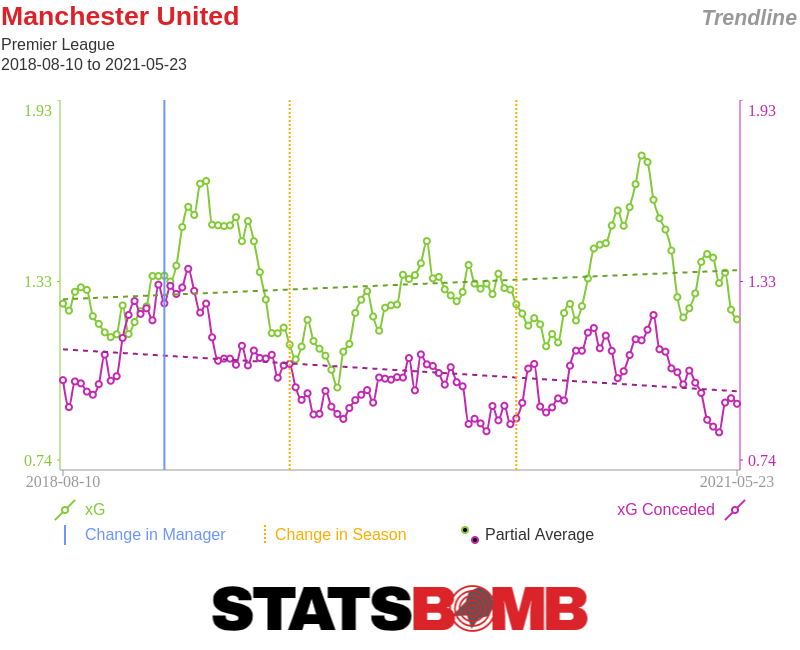

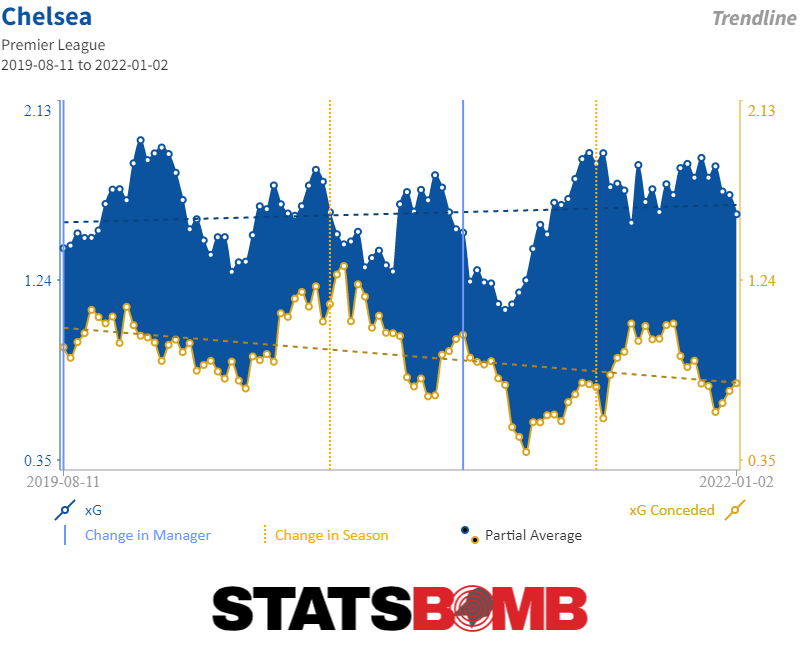

Translation? Expected metrics have slowly crept upwards over time, kinda, actual goal outcomes look more like a heart monitor. This tendency towards wild deviations has actually caused narratives to become slightly faulty. The blast of finishing and run of penalties while Fernandes has been at the club gives the impression that United's attack is their strength, when actually the opposite is likely true--the defence is their bedrock and has been for some while:

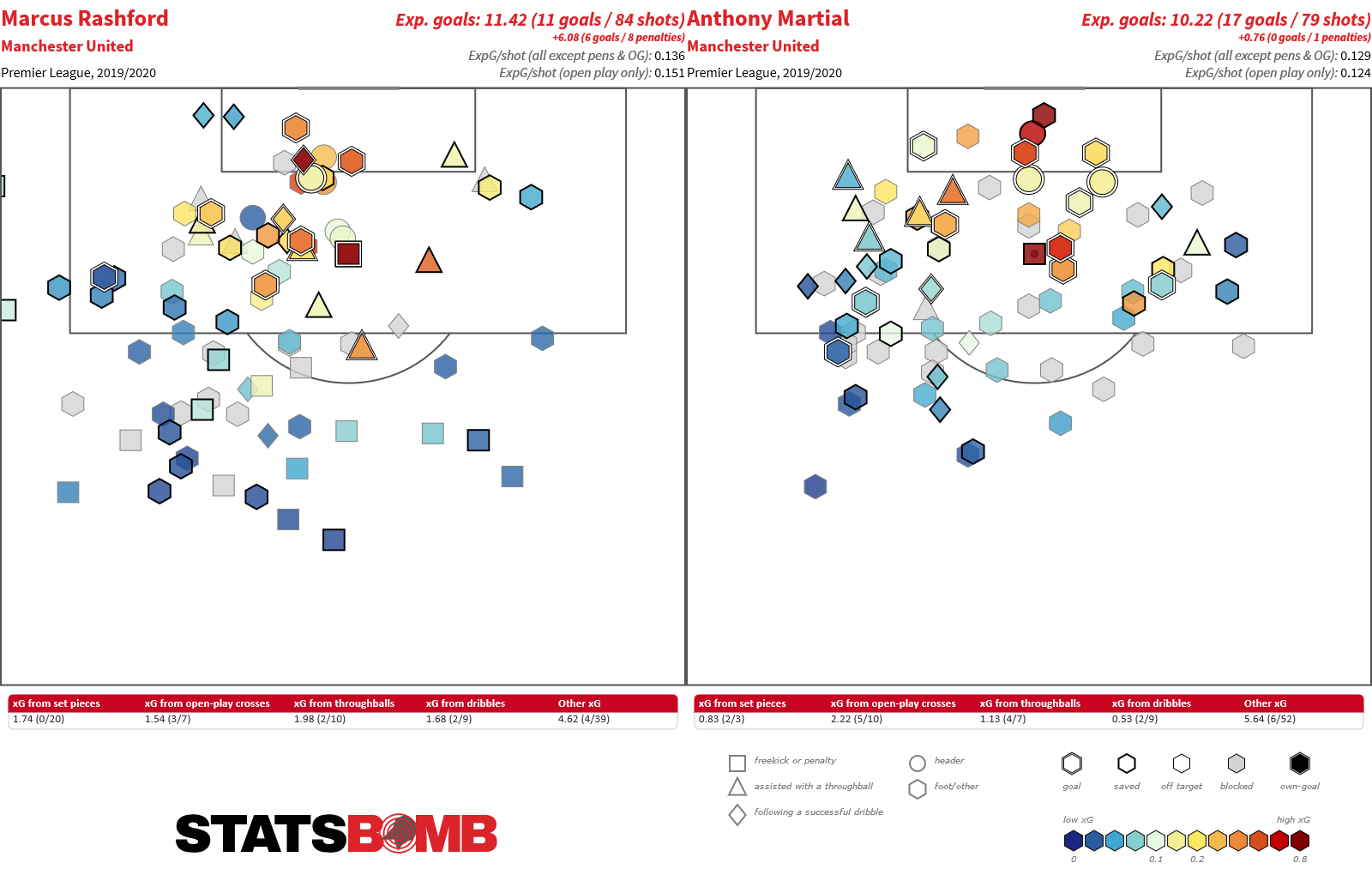

Translation? Expected metrics have slowly crept upwards over time, kinda, actual goal outcomes look more like a heart monitor. This tendency towards wild deviations has actually caused narratives to become slightly faulty. The blast of finishing and run of penalties while Fernandes has been at the club gives the impression that United's attack is their strength, when actually the opposite is likely true--the defence is their bedrock and has been for some while:  A season long expected goal against value of around 0.9 per game is in the ballpark of their rivals--including Manchester City and Liverpool. A season long expected goal for value of 1.3 per game parks then between Southampton and Everton. If this team has designs of winning enough games to point upwards out of the island of third to fourth, it will first and foremost need to get better in attack. How can this be achieved? The front five United fielded during their unbeaten run are a blend of dual purpose longer range shooters and creators (Pogba and Fernandes), shooters (Rashford and Greenwood) and a player with long term finishing prowess who has seen creativity drop off as he's been empowered into a centre forward role (Martial). It's likely that carrying Rashford, Greenwood and Martial (in this role) damages the ability for this team to create a high volume of chances. As we saw towards the end of the season, if Fernandes is quiet, United can really drift and lack incisive creativity. The depth in this area of the pitch is not ideal too with the likes of Jesse Lingard, Juan Mata or Andreas Pereira more sporadic and limited influences. The ship has sailed, but ironically, the profile provided by Alexis Sánchez, or at least a younger more virile version of him, would fit well into this set-up. Somewhere, United's balance of shooting and creativity needs to skew towards the latter. It's what makes the [potential] signing of Donny van de Beek ostensibly curious, as it's quite hard to directly envisage which of United's current attackers or midfielders he will likely replace, or specifically how he'd fit into midfield given how little he tends to contribute towards general buildup. Of course, as more required depth, he's entirely fine, but there's not an obvious way to get Van de Beek into a starting lineup that include Martial, Rashford and Greenwood unless you're entirely throwing caution to the wind and giving midfield a complete pass. This then undermines your already solid defence and puts a heck of a lot onto Pogba and/or Fernandes. This isn't Garth Crooks' team of the week; the Matic/Fred role can't just be abandoned. But at least this problem exists. Yes, the squad needs more depth and the drop off should injury hit any key starter is severe but the outright Manchester United first XI nearly picks itself, something that hasn't always been the case in the post-Ferguson era. To be more generally positive though, in Greenwood and his breakthrough, another fine talent looks to have been unearthed but this has slightly deflected focus on the development of Rashford. Of the attacking unit, his form was perhaps the least impressive post-lockdown, but now in a more settled left sided position, on aggregate his progression is tangible:

A season long expected goal against value of around 0.9 per game is in the ballpark of their rivals--including Manchester City and Liverpool. A season long expected goal for value of 1.3 per game parks then between Southampton and Everton. If this team has designs of winning enough games to point upwards out of the island of third to fourth, it will first and foremost need to get better in attack. How can this be achieved? The front five United fielded during their unbeaten run are a blend of dual purpose longer range shooters and creators (Pogba and Fernandes), shooters (Rashford and Greenwood) and a player with long term finishing prowess who has seen creativity drop off as he's been empowered into a centre forward role (Martial). It's likely that carrying Rashford, Greenwood and Martial (in this role) damages the ability for this team to create a high volume of chances. As we saw towards the end of the season, if Fernandes is quiet, United can really drift and lack incisive creativity. The depth in this area of the pitch is not ideal too with the likes of Jesse Lingard, Juan Mata or Andreas Pereira more sporadic and limited influences. The ship has sailed, but ironically, the profile provided by Alexis Sánchez, or at least a younger more virile version of him, would fit well into this set-up. Somewhere, United's balance of shooting and creativity needs to skew towards the latter. It's what makes the [potential] signing of Donny van de Beek ostensibly curious, as it's quite hard to directly envisage which of United's current attackers or midfielders he will likely replace, or specifically how he'd fit into midfield given how little he tends to contribute towards general buildup. Of course, as more required depth, he's entirely fine, but there's not an obvious way to get Van de Beek into a starting lineup that include Martial, Rashford and Greenwood unless you're entirely throwing caution to the wind and giving midfield a complete pass. This then undermines your already solid defence and puts a heck of a lot onto Pogba and/or Fernandes. This isn't Garth Crooks' team of the week; the Matic/Fred role can't just be abandoned. But at least this problem exists. Yes, the squad needs more depth and the drop off should injury hit any key starter is severe but the outright Manchester United first XI nearly picks itself, something that hasn't always been the case in the post-Ferguson era. To be more generally positive though, in Greenwood and his breakthrough, another fine talent looks to have been unearthed but this has slightly deflected focus on the development of Rashford. Of the attacking unit, his form was perhaps the least impressive post-lockdown, but now in a more settled left sided position, on aggregate his progression is tangible:  He still likes a dip from range, but has shown ever greater ability to get into good quality finishing positions, and at 22 years old, can't be far off the finished article as a player. Martial too appeared to prosper given the centre forward position. His 17 goals from an expected 10 was a welcome boost, but only continues a theme: few players are over their xG every season, but he has been for his entire time at United, albeit not to this degree before:

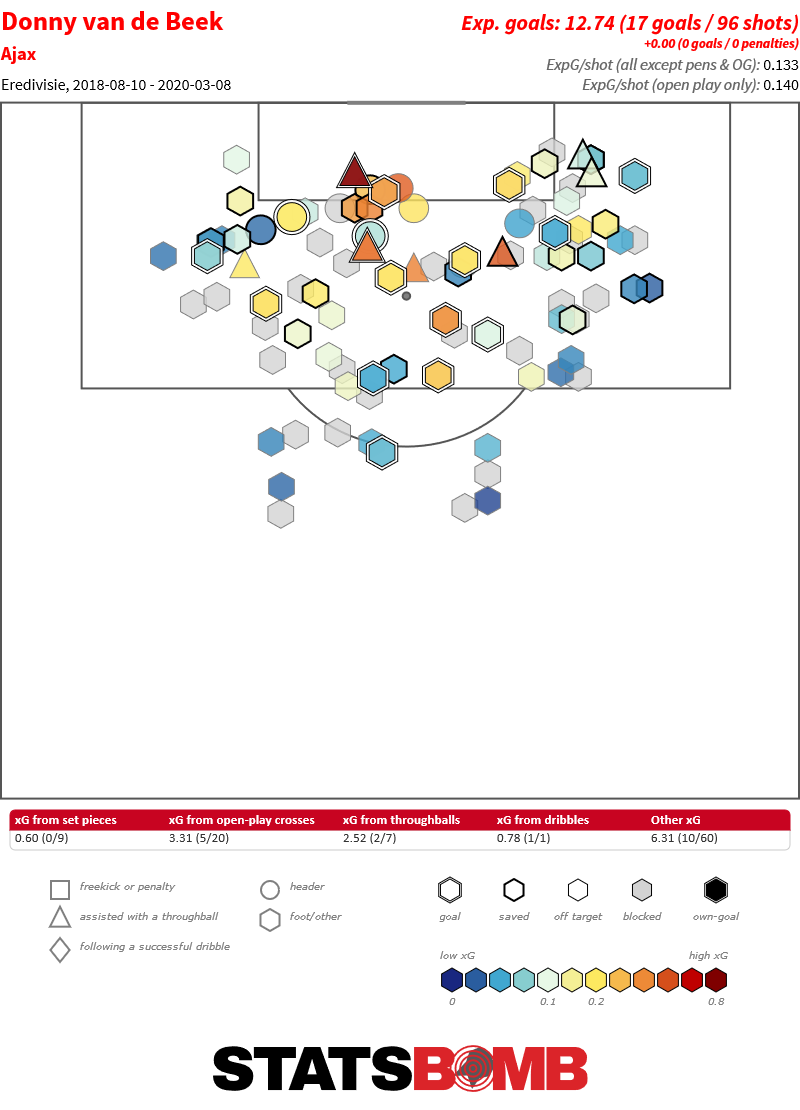

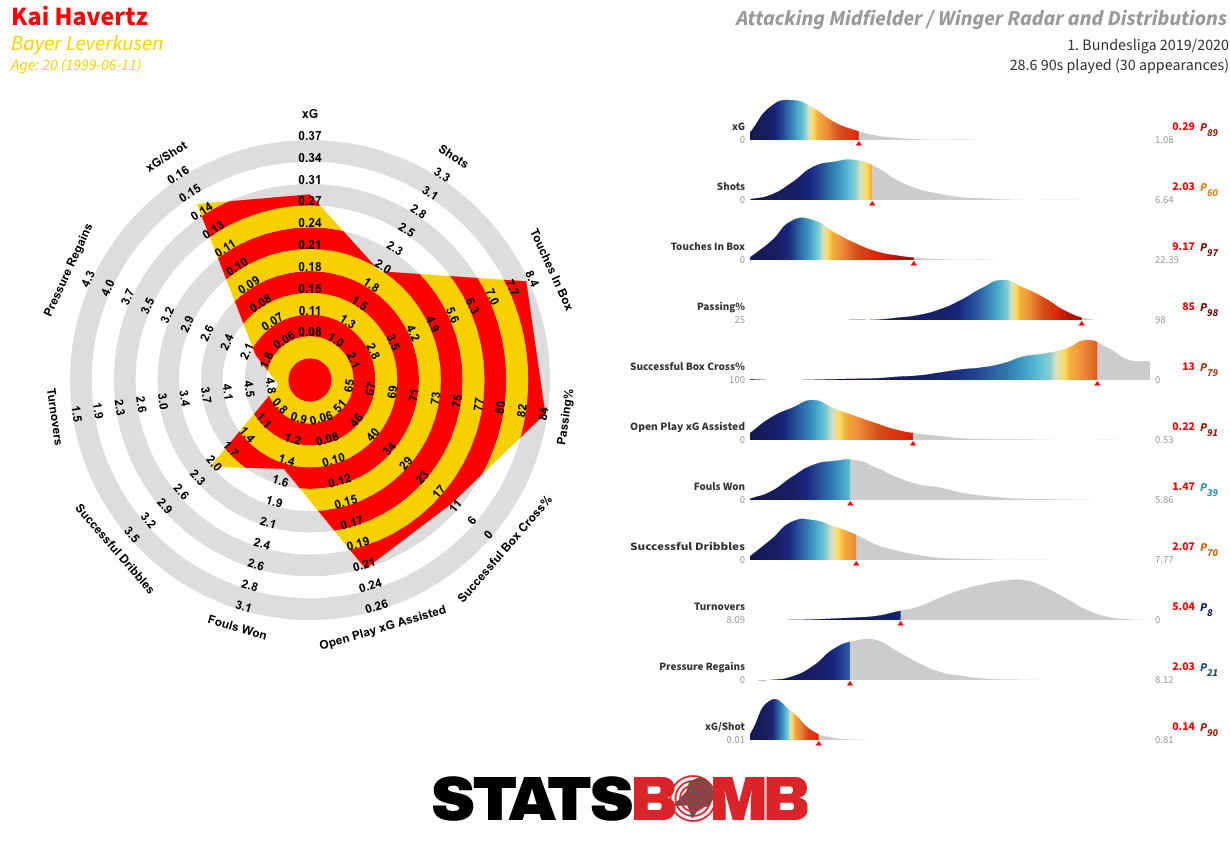

He still likes a dip from range, but has shown ever greater ability to get into good quality finishing positions, and at 22 years old, can't be far off the finished article as a player. Martial too appeared to prosper given the centre forward position. His 17 goals from an expected 10 was a welcome boost, but only continues a theme: few players are over their xG every season, but he has been for his entire time at United, albeit not to this degree before:  If we turn to the new man, Van de Beek, his main qualities can be seen inside the box too. He looks to be a good quality finisher, as we can see from two seasons of Eredivisie shots here:

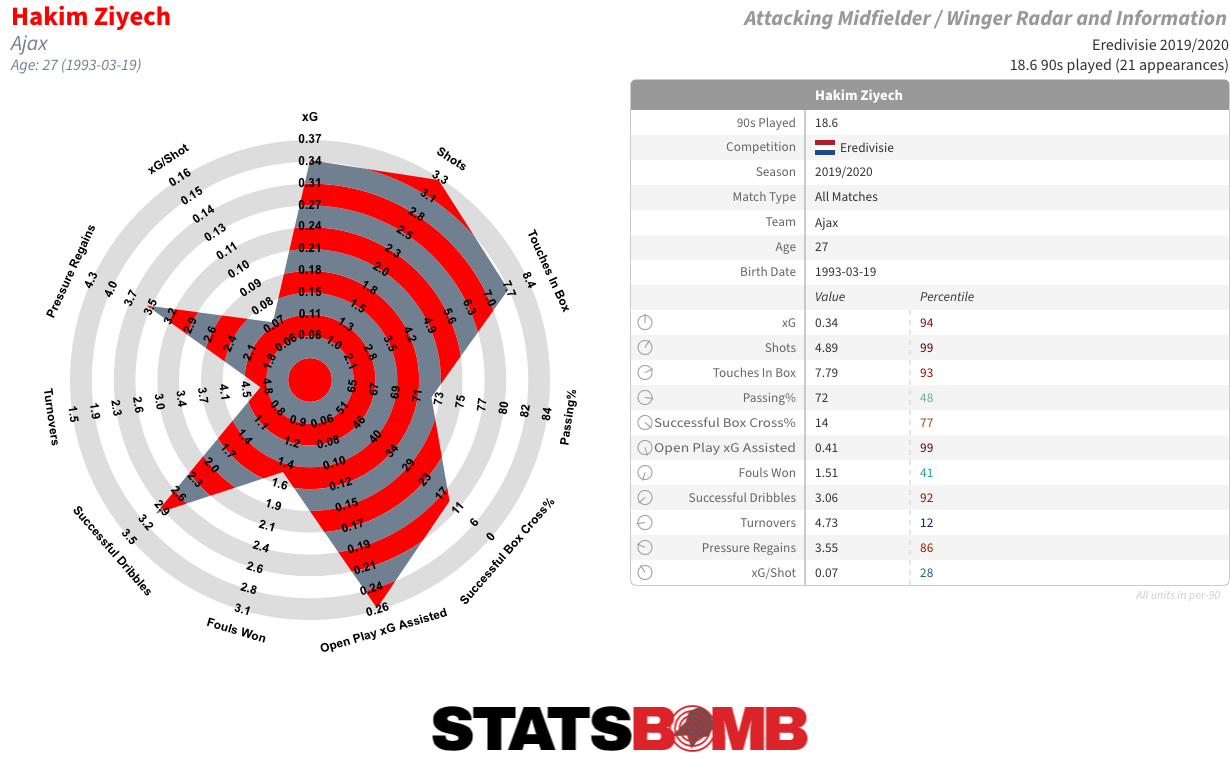

If we turn to the new man, Van de Beek, his main qualities can be seen inside the box too. He looks to be a good quality finisher, as we can see from two seasons of Eredivisie shots here:  He's predominantly right footed, but there's some left foot and head in there too. We reviewed him for our Pro-Scouting project and our executive summary was as follows: Strengths ● Exceptional off-ball movement in and around the penalty area. ● Goalscoring and chance creation numbers outstanding. ● Positionally versatile, can play as central or attacking midfielder. Weaknesses ● Little involvement in build-up. ● Limited defensive output. Summary Donny van de Beek is world-class within his role. He is an exceptional goalscorer from midfield and combines that with great chance creation numbers. However, his involvement in other areas of the game is limited. It is unclear whether or not this profile is enough for clubs at the very highest level, to which he is often linked. Current: Europa League top 5 leagues Potential: Champions League level, in a very defined role. Transfer Potential ● Ajax do not sell cheap, transfer fee likely to be upwards of 40m. My sense here is that the best of Van de Beek may come later in his contract if United continue to build and recruit well, and he's able to fulfil a specific role, but goals and assists from midfield win friends and can cover sins, so he may well come out ahead regardless. With a deal for Jadon Sancho seemingly receding in likelihood and Lionel Messi yet to be sighted in Lancashire, that's it so far for United. The one position that needs no attention is goalkeeper with David De Gea likely to continue despite a less than stellar 2019-20 and Dean Henderson's future slightly uncertain. He won't be returning to Sheffield United, but is plenty good enough to continue as a Premier League number one for someone. Could there be more depth in defence? The work done last summer in acquiring Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Harry Maguire locked down two positions and Luke Shaw has staged something of a renaissance to claim left-back. Victor Lindelöf has nailed down the other starting role across the last two seasons, and again it feels like a question of whether the assorted depth that exists can cover sufficiently, or whether new blood is needed. It would be great to see Eric Bailly or Phil Jones find a run of form and fitness but those eternal question marks mean another centre back would be nice, while Brandon Williams was a successful find last season and can cover both defensive flanks as required. United's whole line up does feel one key injury away from sticking plasters in most positions so another defender and midfield option would tidily round out the summer. Projection Manchester United have a curious schedule to start. They don't face an away trip to a team that finished in the top half last season until week 12 and Sheffield United on December 15th. Of course this means a bunch of better rated teams visiting Old Trafford early on, including Manchester City, Tottenham, Arsenal and Chelsea, from which they got 10/12 points in the corresponding 2019-20 fixtures. A few things will probably happen:

He's predominantly right footed, but there's some left foot and head in there too. We reviewed him for our Pro-Scouting project and our executive summary was as follows: Strengths ● Exceptional off-ball movement in and around the penalty area. ● Goalscoring and chance creation numbers outstanding. ● Positionally versatile, can play as central or attacking midfielder. Weaknesses ● Little involvement in build-up. ● Limited defensive output. Summary Donny van de Beek is world-class within his role. He is an exceptional goalscorer from midfield and combines that with great chance creation numbers. However, his involvement in other areas of the game is limited. It is unclear whether or not this profile is enough for clubs at the very highest level, to which he is often linked. Current: Europa League top 5 leagues Potential: Champions League level, in a very defined role. Transfer Potential ● Ajax do not sell cheap, transfer fee likely to be upwards of 40m. My sense here is that the best of Van de Beek may come later in his contract if United continue to build and recruit well, and he's able to fulfil a specific role, but goals and assists from midfield win friends and can cover sins, so he may well come out ahead regardless. With a deal for Jadon Sancho seemingly receding in likelihood and Lionel Messi yet to be sighted in Lancashire, that's it so far for United. The one position that needs no attention is goalkeeper with David De Gea likely to continue despite a less than stellar 2019-20 and Dean Henderson's future slightly uncertain. He won't be returning to Sheffield United, but is plenty good enough to continue as a Premier League number one for someone. Could there be more depth in defence? The work done last summer in acquiring Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Harry Maguire locked down two positions and Luke Shaw has staged something of a renaissance to claim left-back. Victor Lindelöf has nailed down the other starting role across the last two seasons, and again it feels like a question of whether the assorted depth that exists can cover sufficiently, or whether new blood is needed. It would be great to see Eric Bailly or Phil Jones find a run of form and fitness but those eternal question marks mean another centre back would be nice, while Brandon Williams was a successful find last season and can cover both defensive flanks as required. United's whole line up does feel one key injury away from sticking plasters in most positions so another defender and midfield option would tidily round out the summer. Projection Manchester United have a curious schedule to start. They don't face an away trip to a team that finished in the top half last season until week 12 and Sheffield United on December 15th. Of course this means a bunch of better rated teams visiting Old Trafford early on, including Manchester City, Tottenham, Arsenal and Chelsea, from which they got 10/12 points in the corresponding 2019-20 fixtures. A few things will probably happen:

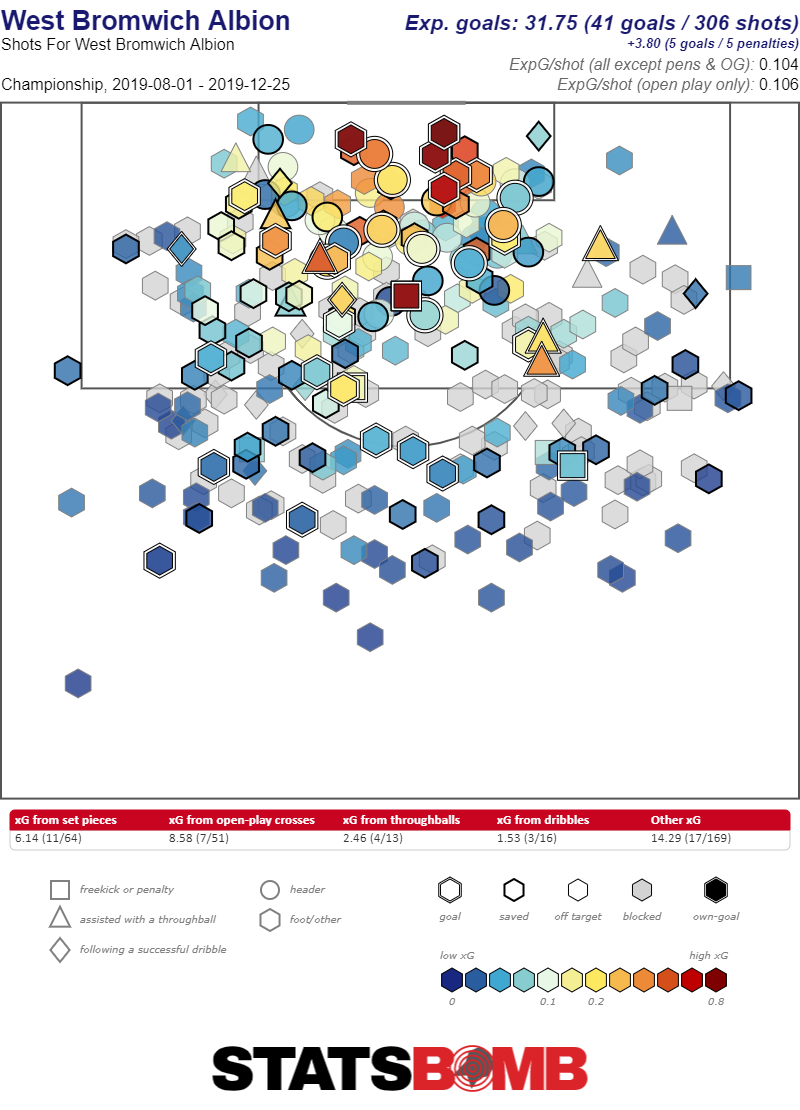

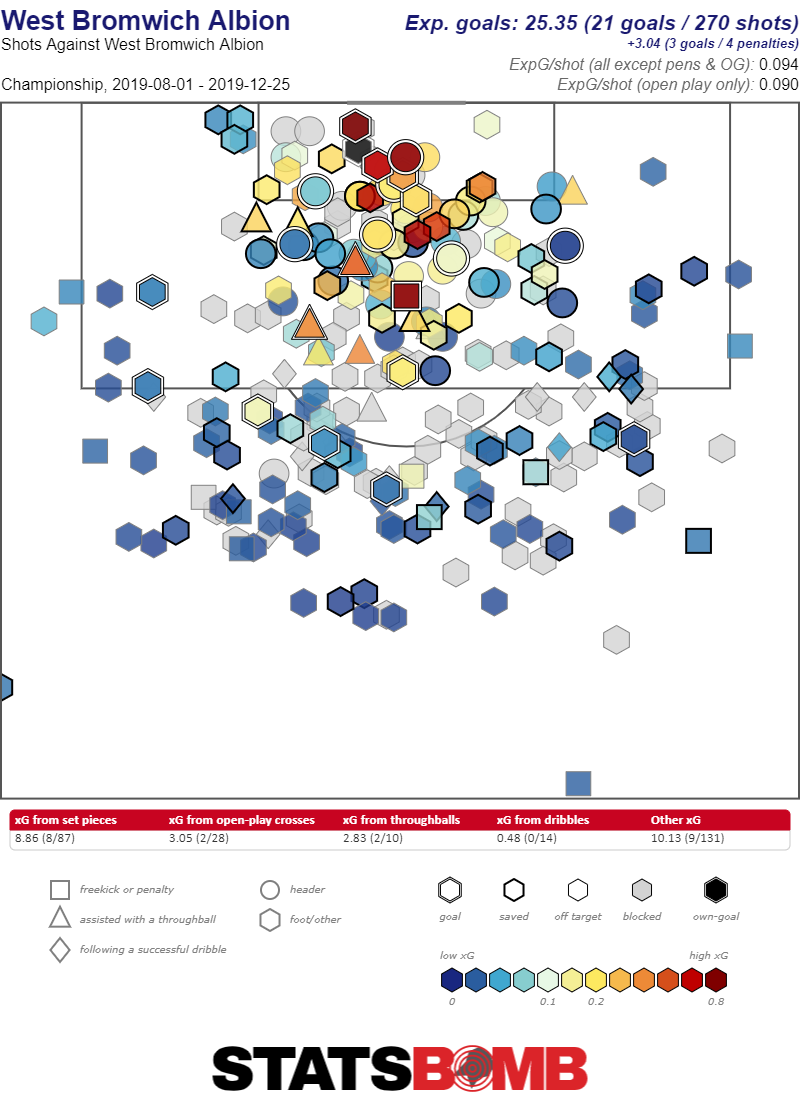

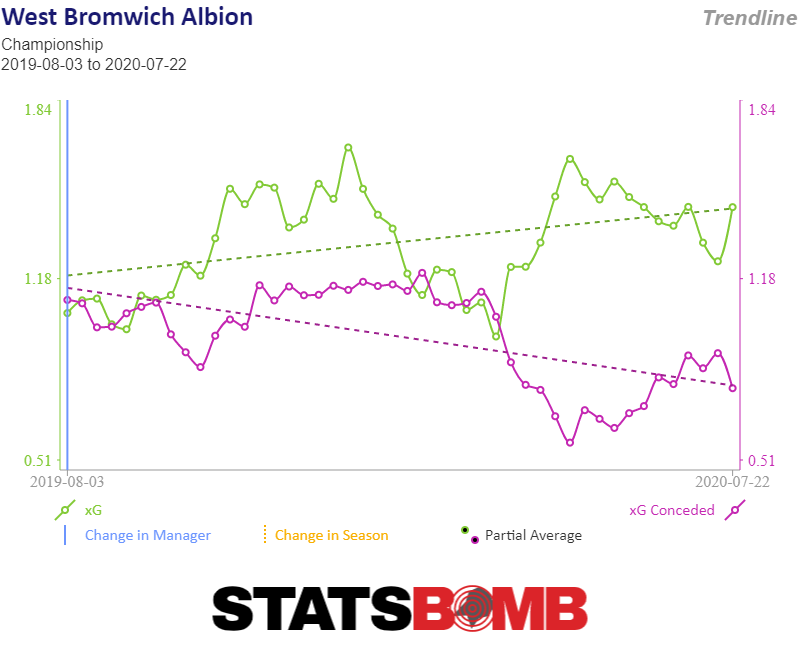

Whilst at the back, there was a little bit of separation on the actual total versus expectation, but nothing as dramatic, conceding 21 times from 25.35xG (plus 3/4 penalties).

Whilst at the back, there was a little bit of separation on the actual total versus expectation, but nothing as dramatic, conceding 21 times from 25.35xG (plus 3/4 penalties).  Running at a 100-point pace in the first half of the season meant that West Brom had the breathing space required to afford them a stagger and stumble on the home stretch. Their subsequent haul of 33 points from the second set of 23 games – only the 10th best record in the Championship in that period - should ring alarm bells for a side bracing themselves to face the Premier League juggernauts ahead, but the underlying numbers may counter the narrative that the Baggies are going into it as a worse side than the one that raced into 1st place by Christmas.

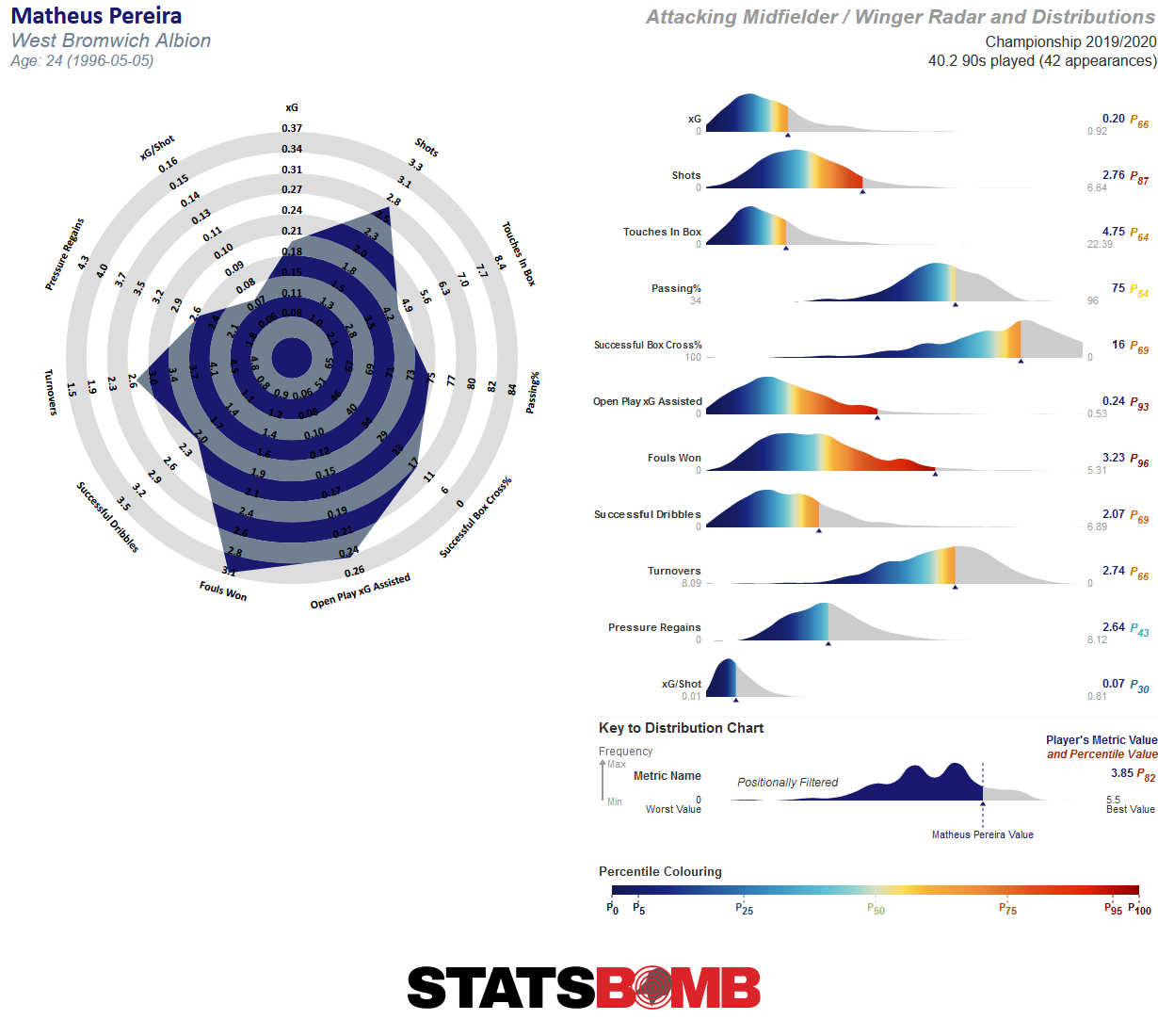

Running at a 100-point pace in the first half of the season meant that West Brom had the breathing space required to afford them a stagger and stumble on the home stretch. Their subsequent haul of 33 points from the second set of 23 games – only the 10th best record in the Championship in that period - should ring alarm bells for a side bracing themselves to face the Premier League juggernauts ahead, but the underlying numbers may counter the narrative that the Baggies are going into it as a worse side than the one that raced into 1st place by Christmas.  Metrics took a nosedive through the Winter period as they rode out a seven-match winless streak in that time but to a large extent that can be explained by the quashing of two of their best performers at that point in the season. West Ham dynamo Grady Diangana, on loan for the season and with 5 goals + 5 assists at that point, picked up an injury which in itself weakened West Brom’s attacking power, but it also allowed the opposition to put even more focus on outstanding talent Matheus Pereira, on 5 goals + 10 assists by that point, shutting him down and roughing him up to an even greater extent. They recovered sufficiently though and, although results were much less impressive, the metrics were virtually identical in the second half of the season: they scored 29 from 32.76xG (plus 2/2 penalties) and conceded 20 from 18.36xG. So, if anything, the metrics were even better and the surface level drop off in results shouldn’t be too much cause for concern, particularly as the pace set in the first half of the season was never likely to sustain anyway. Had they picked up their 83 points in 42 and 41 splits, as their relatively stable (save for the mid-season blip) metrics suggested they could’ve, then there wouldn’t even be a conversation to be had about it. Coming into the top tier, it’s clear West Brom will need reinforcements and a bit of a rejuvenation to the squad - whether they get it or not is another matter. Bilić has already hinted that it’s likely their transfer business will be more Sheffield United than Aston Villa, when comparing to the activities of the promoted Championship sides in last summer’s window. However, The Baggies have made one of the signings of the summer already in making Pereira’s loan deal permanent. Signed from Sporting Lisbon on deadline day in August 2019 for a £750k loan fee, the agreed £8million price tag at that time has turned out to be an absolute snip as Pereira established himself as one of the best players, let alone attacking midfielders, seen in the Championship last season.

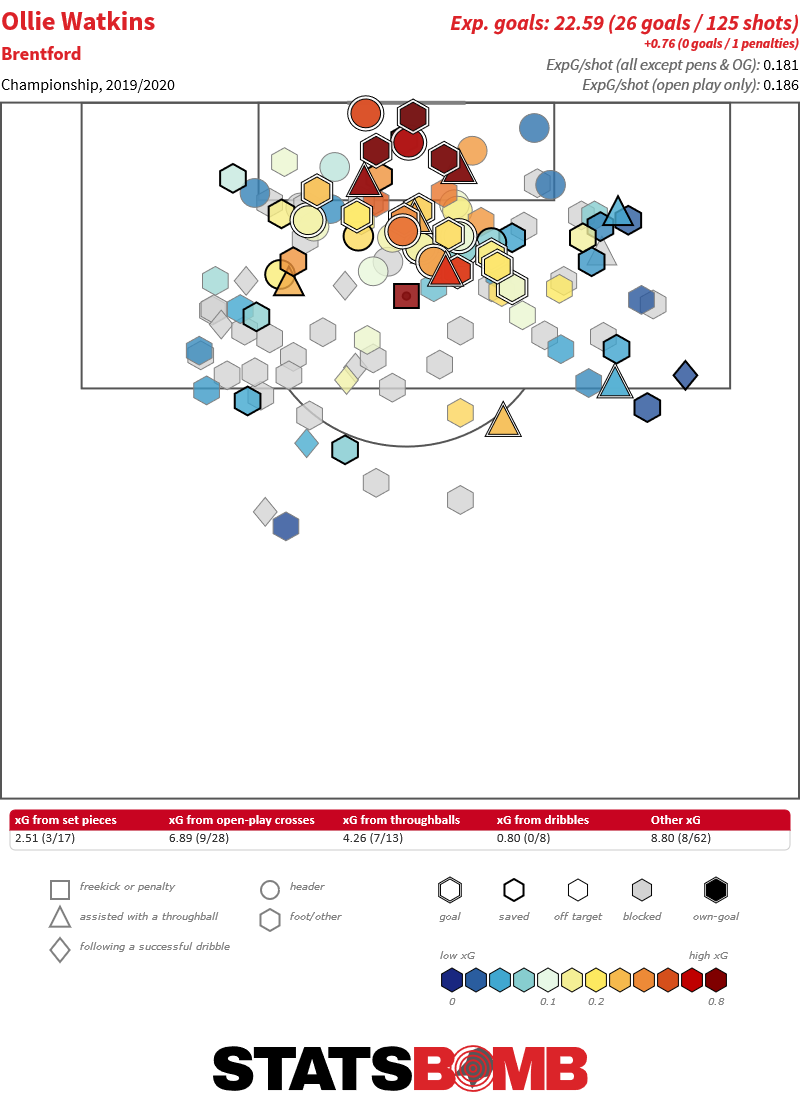

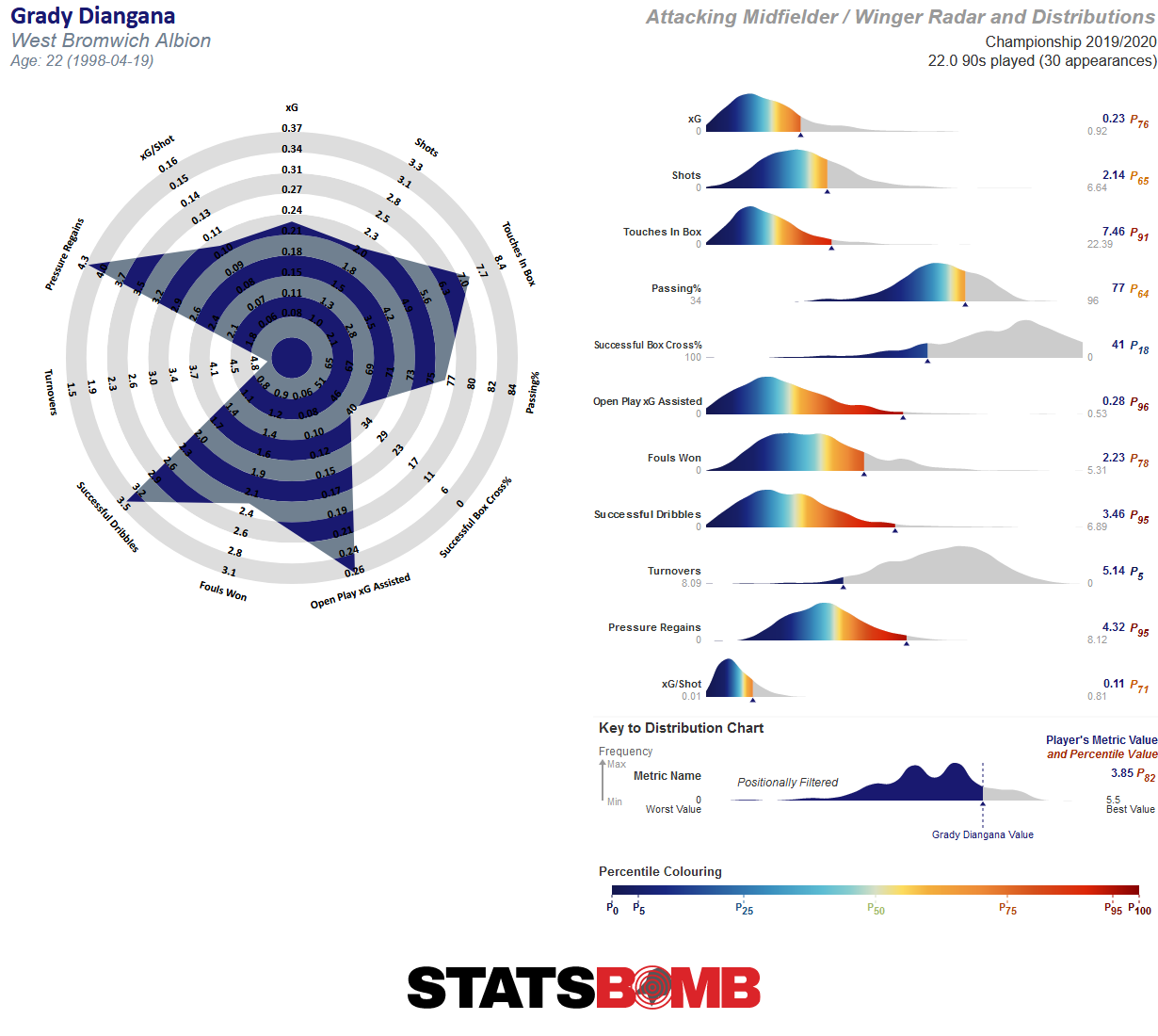

Metrics took a nosedive through the Winter period as they rode out a seven-match winless streak in that time but to a large extent that can be explained by the quashing of two of their best performers at that point in the season. West Ham dynamo Grady Diangana, on loan for the season and with 5 goals + 5 assists at that point, picked up an injury which in itself weakened West Brom’s attacking power, but it also allowed the opposition to put even more focus on outstanding talent Matheus Pereira, on 5 goals + 10 assists by that point, shutting him down and roughing him up to an even greater extent. They recovered sufficiently though and, although results were much less impressive, the metrics were virtually identical in the second half of the season: they scored 29 from 32.76xG (plus 2/2 penalties) and conceded 20 from 18.36xG. So, if anything, the metrics were even better and the surface level drop off in results shouldn’t be too much cause for concern, particularly as the pace set in the first half of the season was never likely to sustain anyway. Had they picked up their 83 points in 42 and 41 splits, as their relatively stable (save for the mid-season blip) metrics suggested they could’ve, then there wouldn’t even be a conversation to be had about it. Coming into the top tier, it’s clear West Brom will need reinforcements and a bit of a rejuvenation to the squad - whether they get it or not is another matter. Bilić has already hinted that it’s likely their transfer business will be more Sheffield United than Aston Villa, when comparing to the activities of the promoted Championship sides in last summer’s window. However, The Baggies have made one of the signings of the summer already in making Pereira’s loan deal permanent. Signed from Sporting Lisbon on deadline day in August 2019 for a £750k loan fee, the agreed £8million price tag at that time has turned out to be an absolute snip as Pereira established himself as one of the best players, let alone attacking midfielders, seen in the Championship last season.  The Brazilian finished the campaign with a total of 8 goals and 16 assists, a contribution eclipsed only by Brentford’s Ollie Watkins, and it’s one piece of the jigsaw Bilić and West Brom fans will be relieved at not having to try and replace, especially at that price point. A reunion with buddy Filip Krovinović remains on the cards, the Croatian came on loan from Sporting’s rivals Benfica but struck up a fruitful relationship on and off the pitch with Pereira. Krovinović’s ball retention turned out to be the perfect counter point to the risk-friendly Pereira and there was often a regular supply line between the two. If reports are to be believed, negotiations are well underway for his return. A deal that could be just as important, and equally shrewd to the Pereira deal if they can successfully negotiate it, is the return of Grady Diangana on a permanent from West Ham, with the Hammers apparently considering accepting an offer for the England U21 winger. Diangana’s season wasn’t held to quite as much fanfare outside of the West Midlands largely due to the medium-term injury he suffered, but Baggies fans know what a talent they had dovetailing with Pereira and probably hadn’t even considered a return for him would be likely on a temporary basis, let alone on a permanent, expecting his good form to take him into the West Ham first team.

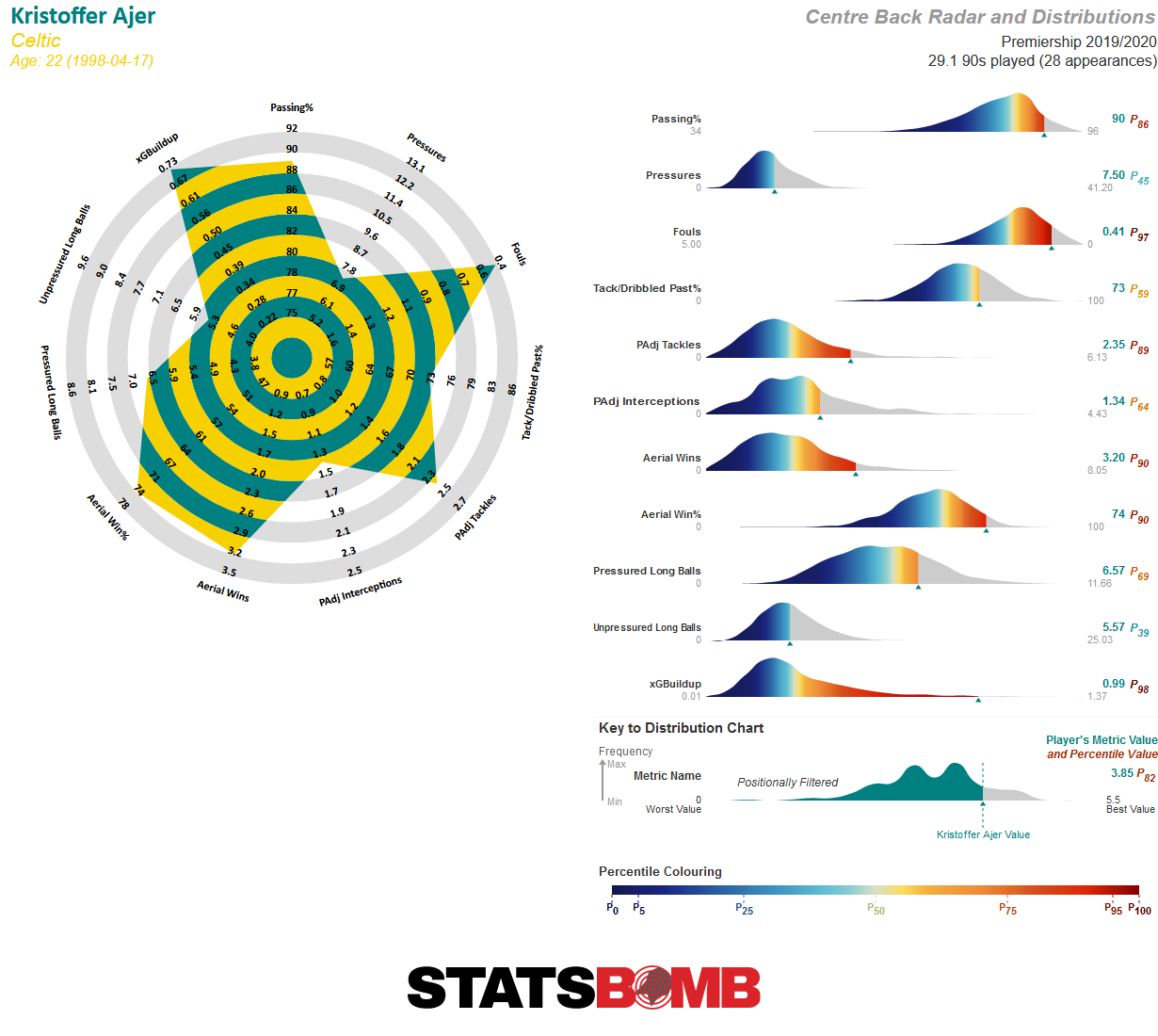

The Brazilian finished the campaign with a total of 8 goals and 16 assists, a contribution eclipsed only by Brentford’s Ollie Watkins, and it’s one piece of the jigsaw Bilić and West Brom fans will be relieved at not having to try and replace, especially at that price point. A reunion with buddy Filip Krovinović remains on the cards, the Croatian came on loan from Sporting’s rivals Benfica but struck up a fruitful relationship on and off the pitch with Pereira. Krovinović’s ball retention turned out to be the perfect counter point to the risk-friendly Pereira and there was often a regular supply line between the two. If reports are to be believed, negotiations are well underway for his return. A deal that could be just as important, and equally shrewd to the Pereira deal if they can successfully negotiate it, is the return of Grady Diangana on a permanent from West Ham, with the Hammers apparently considering accepting an offer for the England U21 winger. Diangana’s season wasn’t held to quite as much fanfare outside of the West Midlands largely due to the medium-term injury he suffered, but Baggies fans know what a talent they had dovetailing with Pereira and probably hadn’t even considered a return for him would be likely on a temporary basis, let alone on a permanent, expecting his good form to take him into the West Ham first team.  * Despite only managing 1980 minutes, Diangana undoubtedly made West Brom a much better side when he was in it and his 0.64 goals+assists per 90 minutes ranked 6th in the Championship for players with 1500 minutes or more – ahead of the likes of Pereira, Watkins, Mitrovic and Benrahma – and his 3.46 successful dribbles per 90 ranked 2nd in the league, getting the better of whichever fullback he was up against virtually every week. Reuniting Pereira, Diangana and Krovinovic, three key contributors to West Brom’s promotion, would be a huge boost and perhaps one that was unexpected at the close of the season, Pereira’s formality of a transfer aside. Probably the most important business they still have to do will be in recruiting a centre forward. None of Charlie Austin, Hal Robson-Kanu or Kenneth Zohore nailed down the role through last season and an upgrade is a high priority. Romaine Sawyers and Jake Livermore had excellent seasons as the double pivot in midfield but will need more help with little depth behind them, whilst Semi Ajayi needs a partner at centre back as Ahmed Hegazy and Kyle Bartley were rotated and apparently not entirely trusted by Bilić. A move for Brighton’s Shane Duffy failed as he opted to join Celtic, but that in itself could open the door for West Brom to make a move to bring Kristoffer Ajer south of the border who has been linked.

* Despite only managing 1980 minutes, Diangana undoubtedly made West Brom a much better side when he was in it and his 0.64 goals+assists per 90 minutes ranked 6th in the Championship for players with 1500 minutes or more – ahead of the likes of Pereira, Watkins, Mitrovic and Benrahma – and his 3.46 successful dribbles per 90 ranked 2nd in the league, getting the better of whichever fullback he was up against virtually every week. Reuniting Pereira, Diangana and Krovinovic, three key contributors to West Brom’s promotion, would be a huge boost and perhaps one that was unexpected at the close of the season, Pereira’s formality of a transfer aside. Probably the most important business they still have to do will be in recruiting a centre forward. None of Charlie Austin, Hal Robson-Kanu or Kenneth Zohore nailed down the role through last season and an upgrade is a high priority. Romaine Sawyers and Jake Livermore had excellent seasons as the double pivot in midfield but will need more help with little depth behind them, whilst Semi Ajayi needs a partner at centre back as Ahmed Hegazy and Kyle Bartley were rotated and apparently not entirely trusted by Bilić. A move for Brighton’s Shane Duffy failed as he opted to join Celtic, but that in itself could open the door for West Brom to make a move to bring Kristoffer Ajer south of the border who has been linked.  The apparent faltering at the back end of the campaign has probably quelled confidence amongst the fanbase and there’s a sense of realism that they’ll have to overcome the odds to finish above the dotted red line in 2020/21. The squad was already in need of retooling anyway - let alone to be ready to step up to the Premier League - and there seemingly isn’t a huge amount of backing available in order to do that. That said, shrewd additions in problem areas will at least help the Baggies to be competitive and should Bilić adjust the tactical setup sufficiently in order to keep them solid at the back, providing a foundation for the star quality in the side to thrive, then they may just have a chance. Otherwise, a return trip down the yo-yo in May 2021 could beckon.

The apparent faltering at the back end of the campaign has probably quelled confidence amongst the fanbase and there’s a sense of realism that they’ll have to overcome the odds to finish above the dotted red line in 2020/21. The squad was already in need of retooling anyway - let alone to be ready to step up to the Premier League - and there seemingly isn’t a huge amount of backing available in order to do that. That said, shrewd additions in problem areas will at least help the Baggies to be competitive and should Bilić adjust the tactical setup sufficiently in order to keep them solid at the back, providing a foundation for the star quality in the side to thrive, then they may just have a chance. Otherwise, a return trip down the yo-yo in May 2021 could beckon.

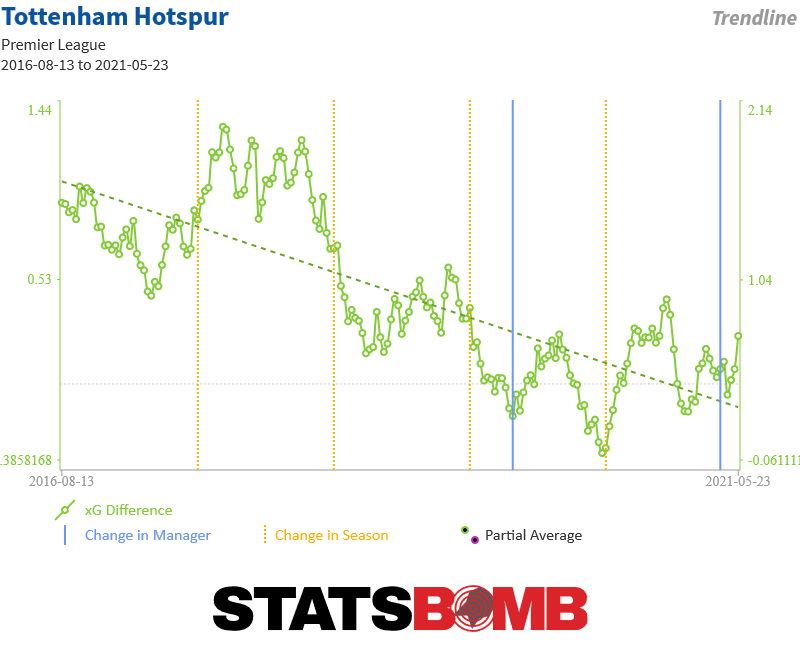

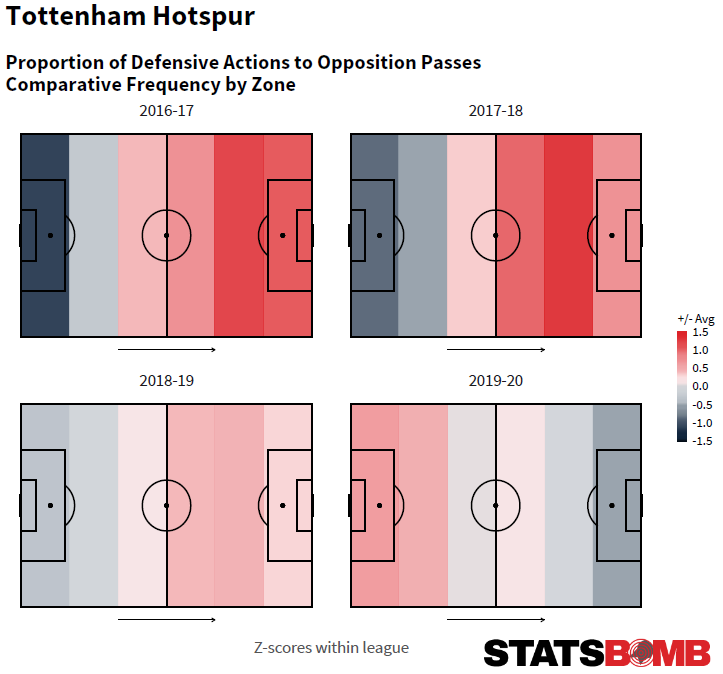

Well, the first thing that went wrong was that the metrics got worse. The second thing that went wrong was the results were terrible. The third thing that went wrong was Mauricio Pochettino was fired. Really, this was all just one large thing that engulfed the club in a manner befitting of a 22-minute segment in a documentary. There was no way around it though, Tottenham had three wins from twelve in the league, had deserved no more from their performances and had been annihilated 7-2 in the Champions League by a promising German side, Bayern Munich. Enter Mourinho. On the surface the 26 league games Mourinho has overseen have been just about good enough. Tottenham got 45 points (65 point pace) which ranked fourth and their goal difference of +13 ranked fourth too. What that conceals is that Mourinho’s tenure has already been through three distinct acts, and the main hope for fans is that the most recent of those acts involved winning more frequently than not. It's also challenging to get used to a Tottenham team that plays very different football to that of the best of Pochettino--and by the time of his departure, despite the Champions League run, that best was a long time passed. Act 1: Duration: 8 games in 2019 Results: 5-1-2 GD: +6 xG: +5 Note: xG Against at 0.65 per game is best in the league The start for Mourinho was promising but didn't come without disappointments. Defeats against his two former clubs, Manchester United (2-1 at Old Trafford in a low event game decided by a Marcus Rashford penalty) and Chelsea (2-0 at home, a Willian penalty sealing the deal soon after renowned hatchet man Son Heung-min was sent off) were classics in the "create nothing, try not to lose" Mourinho canon. Elsewhere the team won five from six before the turn of the new year and certain metrics shone brightly; in defence, the team was giving up very few shots, specifically in good, central dangerous locations. Occasional penalties apart, Tottenham were repelling all. Yes, the schedule was quite kind, but there was a win over Wolves in there too alongside more straightforward victories against lower ranked teams such as Burnley, West Ham, Brighton and Bournemouth. Something to build on? Act 2: Duration: 9 games in a world gradually learning about coronaviruses Results: 3-2-4 GD: +0 xG: -5 Note: xG Against at 1.82 per game is second worst in the whole league The second act was not-so-good. In fact it was downright bad. The schedule bit a little with defeats against Southampton (1-0, created nothing), Liverpool (1-0, played surprisingly well, at least in the second half), Chelsea (again 2-1, this time created nothing, deserved nothing) and Wolves (3-2, overpowered late on, gave it away). There was also a 2-0 win against Manchester City which was as equally improbable as the 2-2 draw earlier in the season at the Etihad. In both games City did enough to win multiple games but somehow couldn't get anything to stick. But the underlying concern came in the same form that had looked so promising weeks before. The defence faltered horribly, moving from league best to nearly league worst and in every one of these nine games Tottenham allowed xG worth between 1.4 to 3.7 per game. They didn't have a single defensively secure game all through and were averaging 16 shots per game against. Really grim stuff. Tottenham also departed the Champions League after being significantly worse than RB Leipzig and lost in the FA Cup on penalties to Norwich, the kind of result that is hard to explain away when you know, deep down, the manager would like to nab a trophy and quick. When the curtains came down on football, they had lost five out of six, and were limping along having been left weakened by injuries to key men such as Kane and Son. Act 3: Duration: 9 games, summer is here and so is your Premier League finale Results: 5-3-1 GD: +7 xG: -2 Note: xG For is 15th, xG Against is 6th Turns out a three month break does wonders for the health of a squad! With Kane and Son back fit, the back end of 2019-20 held a degree of promise. Results were generally good. Performances were... less so. The 0-0 with Bournemouth was about as poorly as Tottenham have played in memory, with the Sheffield United defeat not far behind. Tottenham's attack created very little during this spell: in six of nine games the took ten or fewer shots or failed to create more than one expected goal. To brazenly defy expected goals they also took the lead three times via an own goal. The only game in which the result happily matched expectation was the 2-1 derby win over Arsenal. The defence was sturdier--in four of nine games the expected goals allowed was less than one--and in two further games it was just a shade over. Overall, it's impossible to be analytically inclined and generally happy with how performances have developed across the Mourinho reign, but the better post-break results certainly eased pressure that had been building, even this quickly into his tenure. Style Undoubtedly the style of play is very different. After five hard years, the Pochettino press had already somewhat waned a deal of time before his departure:

Well, the first thing that went wrong was that the metrics got worse. The second thing that went wrong was the results were terrible. The third thing that went wrong was Mauricio Pochettino was fired. Really, this was all just one large thing that engulfed the club in a manner befitting of a 22-minute segment in a documentary. There was no way around it though, Tottenham had three wins from twelve in the league, had deserved no more from their performances and had been annihilated 7-2 in the Champions League by a promising German side, Bayern Munich. Enter Mourinho. On the surface the 26 league games Mourinho has overseen have been just about good enough. Tottenham got 45 points (65 point pace) which ranked fourth and their goal difference of +13 ranked fourth too. What that conceals is that Mourinho’s tenure has already been through three distinct acts, and the main hope for fans is that the most recent of those acts involved winning more frequently than not. It's also challenging to get used to a Tottenham team that plays very different football to that of the best of Pochettino--and by the time of his departure, despite the Champions League run, that best was a long time passed. Act 1: Duration: 8 games in 2019 Results: 5-1-2 GD: +6 xG: +5 Note: xG Against at 0.65 per game is best in the league The start for Mourinho was promising but didn't come without disappointments. Defeats against his two former clubs, Manchester United (2-1 at Old Trafford in a low event game decided by a Marcus Rashford penalty) and Chelsea (2-0 at home, a Willian penalty sealing the deal soon after renowned hatchet man Son Heung-min was sent off) were classics in the "create nothing, try not to lose" Mourinho canon. Elsewhere the team won five from six before the turn of the new year and certain metrics shone brightly; in defence, the team was giving up very few shots, specifically in good, central dangerous locations. Occasional penalties apart, Tottenham were repelling all. Yes, the schedule was quite kind, but there was a win over Wolves in there too alongside more straightforward victories against lower ranked teams such as Burnley, West Ham, Brighton and Bournemouth. Something to build on? Act 2: Duration: 9 games in a world gradually learning about coronaviruses Results: 3-2-4 GD: +0 xG: -5 Note: xG Against at 1.82 per game is second worst in the whole league The second act was not-so-good. In fact it was downright bad. The schedule bit a little with defeats against Southampton (1-0, created nothing), Liverpool (1-0, played surprisingly well, at least in the second half), Chelsea (again 2-1, this time created nothing, deserved nothing) and Wolves (3-2, overpowered late on, gave it away). There was also a 2-0 win against Manchester City which was as equally improbable as the 2-2 draw earlier in the season at the Etihad. In both games City did enough to win multiple games but somehow couldn't get anything to stick. But the underlying concern came in the same form that had looked so promising weeks before. The defence faltered horribly, moving from league best to nearly league worst and in every one of these nine games Tottenham allowed xG worth between 1.4 to 3.7 per game. They didn't have a single defensively secure game all through and were averaging 16 shots per game against. Really grim stuff. Tottenham also departed the Champions League after being significantly worse than RB Leipzig and lost in the FA Cup on penalties to Norwich, the kind of result that is hard to explain away when you know, deep down, the manager would like to nab a trophy and quick. When the curtains came down on football, they had lost five out of six, and were limping along having been left weakened by injuries to key men such as Kane and Son. Act 3: Duration: 9 games, summer is here and so is your Premier League finale Results: 5-3-1 GD: +7 xG: -2 Note: xG For is 15th, xG Against is 6th Turns out a three month break does wonders for the health of a squad! With Kane and Son back fit, the back end of 2019-20 held a degree of promise. Results were generally good. Performances were... less so. The 0-0 with Bournemouth was about as poorly as Tottenham have played in memory, with the Sheffield United defeat not far behind. Tottenham's attack created very little during this spell: in six of nine games the took ten or fewer shots or failed to create more than one expected goal. To brazenly defy expected goals they also took the lead three times via an own goal. The only game in which the result happily matched expectation was the 2-1 derby win over Arsenal. The defence was sturdier--in four of nine games the expected goals allowed was less than one--and in two further games it was just a shade over. Overall, it's impossible to be analytically inclined and generally happy with how performances have developed across the Mourinho reign, but the better post-break results certainly eased pressure that had been building, even this quickly into his tenure. Style Undoubtedly the style of play is very different. After five hard years, the Pochettino press had already somewhat waned a deal of time before his departure:  Despite clear mentions of pressing in the Amazon documentary, it doesn't really come out in the metrics. Tottenham may still work hard, but not as high up the pitch as before. The signing of Steven Bergwijn defines what Mourinho wants from his non-Kane attackers. Quick and able to stretch defences especially on the break, Bergwijn's talents categorise neatly alongside Lucas Moura and Son. Midfield has been a problem for Tottenham for a number of seasons, and Mourinho's solution was somewhat creative: try to bypass it.

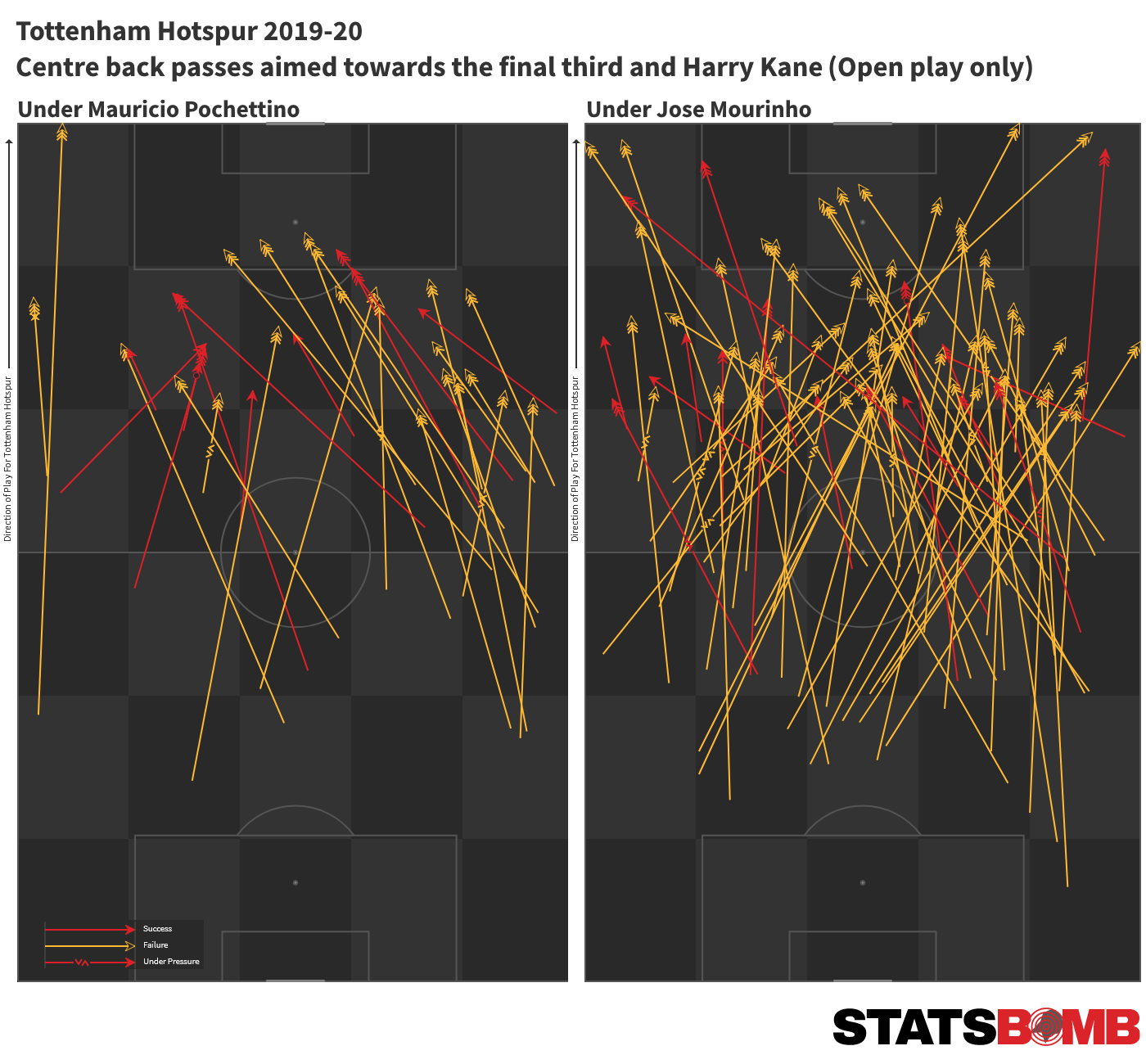

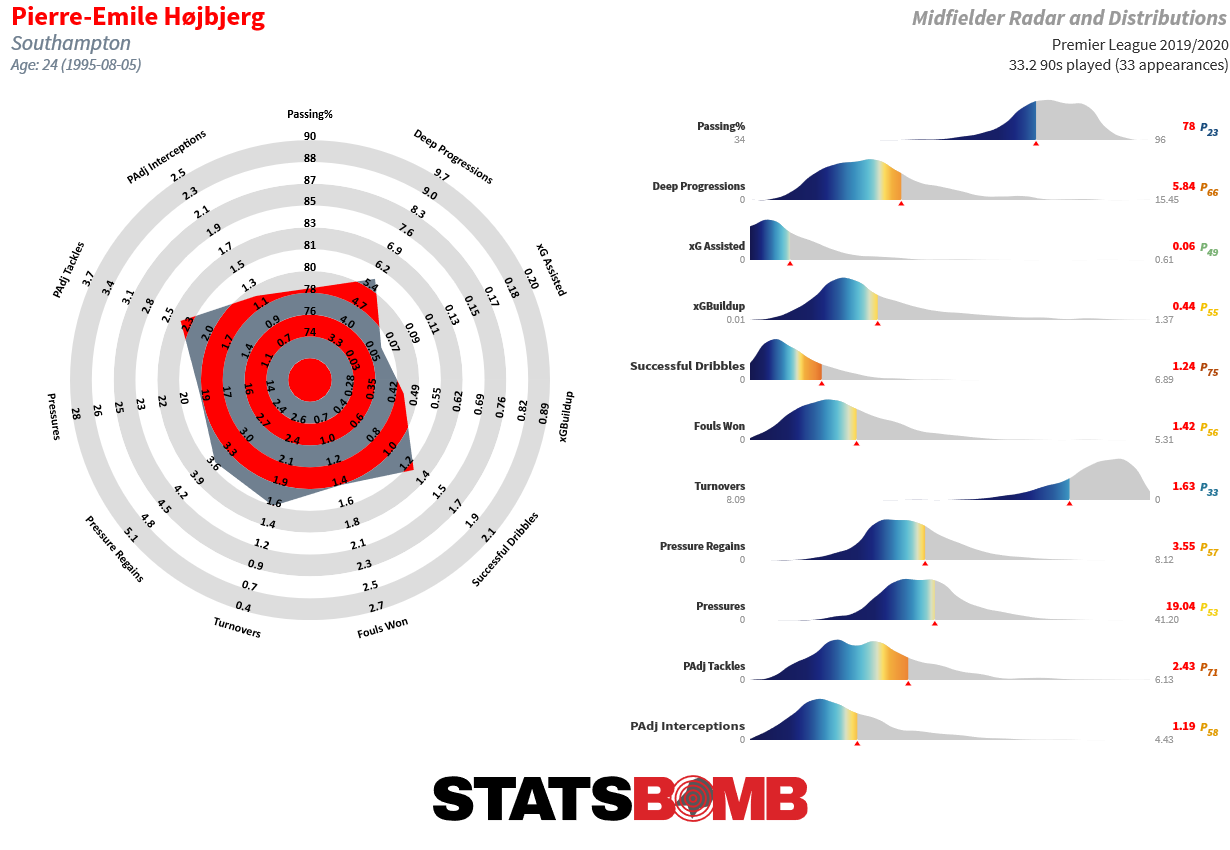

Despite clear mentions of pressing in the Amazon documentary, it doesn't really come out in the metrics. Tottenham may still work hard, but not as high up the pitch as before. The signing of Steven Bergwijn defines what Mourinho wants from his non-Kane attackers. Quick and able to stretch defences especially on the break, Bergwijn's talents categorise neatly alongside Lucas Moura and Son. Midfield has been a problem for Tottenham for a number of seasons, and Mourinho's solution was somewhat creative: try to bypass it.  The change here from the steadier possession game deployed by Pochettino to a more direct targeted passing system was notable. The graphic shows balls aimed at Kane from centre backs in open play, and this type of pass went from three per game under Pochettino with a huge skew towards Alderweireld (over two-thirds of these passes were from him) to over five per game under Mourinho, with all the centre backs looking for this ball. The other attackers saw a similar uptick in receiving targeted long passes too, with Son, Lucas and eventually Bergwijn under Mourinho combining to receive nearly six of these passes per game up from three, and again a large skew away from just Alderweireld towards all centre backs. Both goalkeepers looked for similar out balls too, with a large rise in any keeper clearance (dead ball or otherwise) aimed at the forwards. This is also where the signing of Matt Doherty is interesting, as he's shown himself to be well capable in competing for long, high balls and taking up an advanced position -- Serge Aurier already takes up similar roles but hasn't the aerial prowess to dominate opposing full backs. Doherty may well be able to do this and provide flicks and nod downs, to help release Tottenham's speedy forwards. It's not total football, but it could well be part of the Mourinho plan. Personnel The eternal dance at Tottenham between Chairman Daniel Levy and incumbent managers regarding player acquisition appears so far to not be taking place with Mourinho. Players that have been recruited are not wildly expensive or apparently indulgent and may well be better than the raw detail suggests. The talent within the Tottenham squad is impossible to deny, from World Cup winner Hugo Lloris in goal right through to Kane up front. But supporting roles have waned over time, and the signings of Pierre-Emile Højbjerg and Doherty in particular, appear to show the intent to solidify key positions to perhaps allow the gifted attackers to flourish. There are distinct "do everything, but just a bit" vibes to Højbjerg's metrics in particular, but perhaps that's what this team needs: consistency and stability.

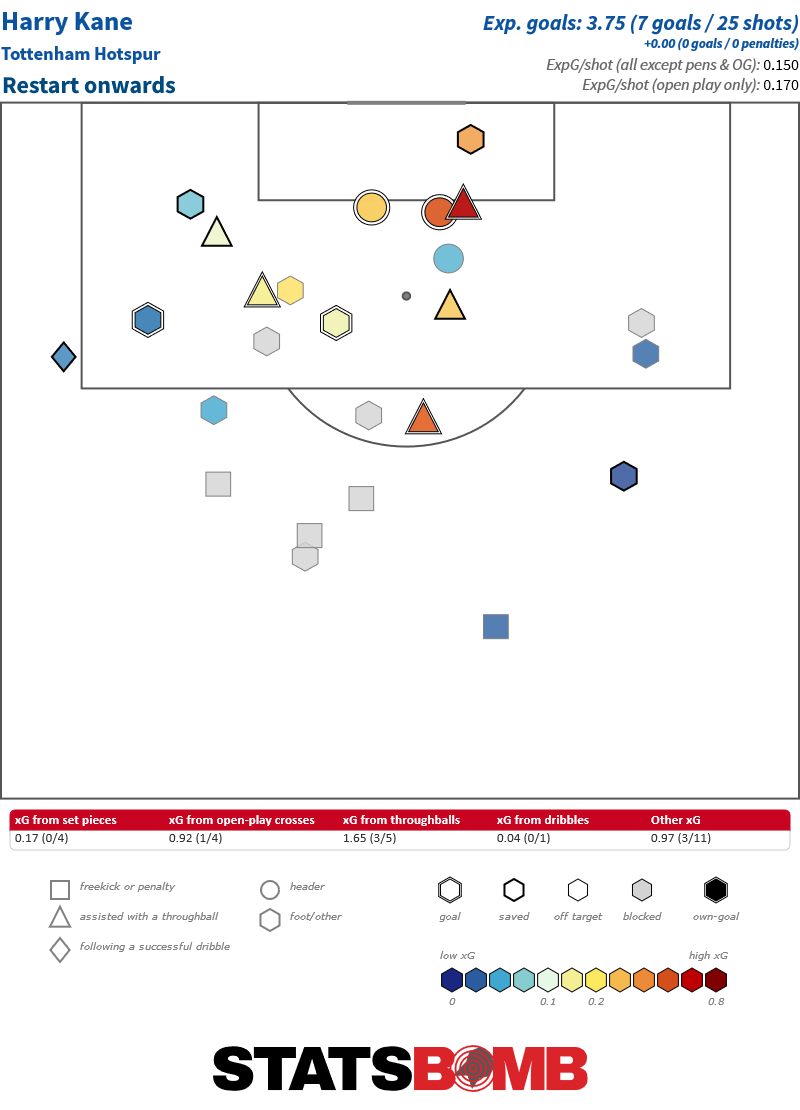

The change here from the steadier possession game deployed by Pochettino to a more direct targeted passing system was notable. The graphic shows balls aimed at Kane from centre backs in open play, and this type of pass went from three per game under Pochettino with a huge skew towards Alderweireld (over two-thirds of these passes were from him) to over five per game under Mourinho, with all the centre backs looking for this ball. The other attackers saw a similar uptick in receiving targeted long passes too, with Son, Lucas and eventually Bergwijn under Mourinho combining to receive nearly six of these passes per game up from three, and again a large skew away from just Alderweireld towards all centre backs. Both goalkeepers looked for similar out balls too, with a large rise in any keeper clearance (dead ball or otherwise) aimed at the forwards. This is also where the signing of Matt Doherty is interesting, as he's shown himself to be well capable in competing for long, high balls and taking up an advanced position -- Serge Aurier already takes up similar roles but hasn't the aerial prowess to dominate opposing full backs. Doherty may well be able to do this and provide flicks and nod downs, to help release Tottenham's speedy forwards. It's not total football, but it could well be part of the Mourinho plan. Personnel The eternal dance at Tottenham between Chairman Daniel Levy and incumbent managers regarding player acquisition appears so far to not be taking place with Mourinho. Players that have been recruited are not wildly expensive or apparently indulgent and may well be better than the raw detail suggests. The talent within the Tottenham squad is impossible to deny, from World Cup winner Hugo Lloris in goal right through to Kane up front. But supporting roles have waned over time, and the signings of Pierre-Emile Højbjerg and Doherty in particular, appear to show the intent to solidify key positions to perhaps allow the gifted attackers to flourish. There are distinct "do everything, but just a bit" vibes to Højbjerg's metrics in particular, but perhaps that's what this team needs: consistency and stability.  Will it work? Getting Højbjerg in as a likely guaranteed starter means we're unlikely to see Harry Winks and Moussa Sissoko start many games together with Giovani Lo Celso already the passing heartbeat of the side picked ahead of them. Doherty's arrival allows Aurier to depart and locks down one position. The attacking midfield band is rich with Dele Alli, Bergwijn, Moura, Son and Erik Lamela competing for a maximum of three positions. What of Tanguy Ndombélé? I'll plead the fifth, thanks. It's possible that the Frenchman's inability to nail down a starting place is indicative of the slightly altered transfer focus, as his signing combined with an investment in Jack Clarke and Ryan Sessegnon that is a long way off bearing fruit means £100m of summer 2019 purchases are not yet directly impacting the first team. Doherty and Højbjerg scope out at around £30m (and books are balancing a little more once Kyle Walker-Peters' departure is factored in) and will likely play every week. Getting purchases into the team and contributing counts for a lot. There are noises that more players could arrive, most notably a rotational striker, but in Covid-19 world, it's likely to be more book-balancing than big purchases, so it also depends who is on the outs. With football finishing only a month ago, we have fresh answers to long term questions. Whether Kane could refind something near to his best form after a six month break to recover from his latest injury appeared to be answered in the affirmative by a tidy finishing streak. To the casual eye he looked more dynamic than before, and whatever the truth is of his long term mobility and the impact of injuries on him, the work that he's put into his finishing over the course of many years will likely carry him well into his latter career. It's also possible that there's a bias generated in seeing him score three goals from five throughball shots as it's never been an area in which he's been wildly prolific (10 goals from 31 such shots in the league across the previous four seasons). Still: at 2.5 shots per 90, albeit for a ten shot a game team, he needs the finishing to stay sharp to get the totals up and mini runs such as this will not persist long term:

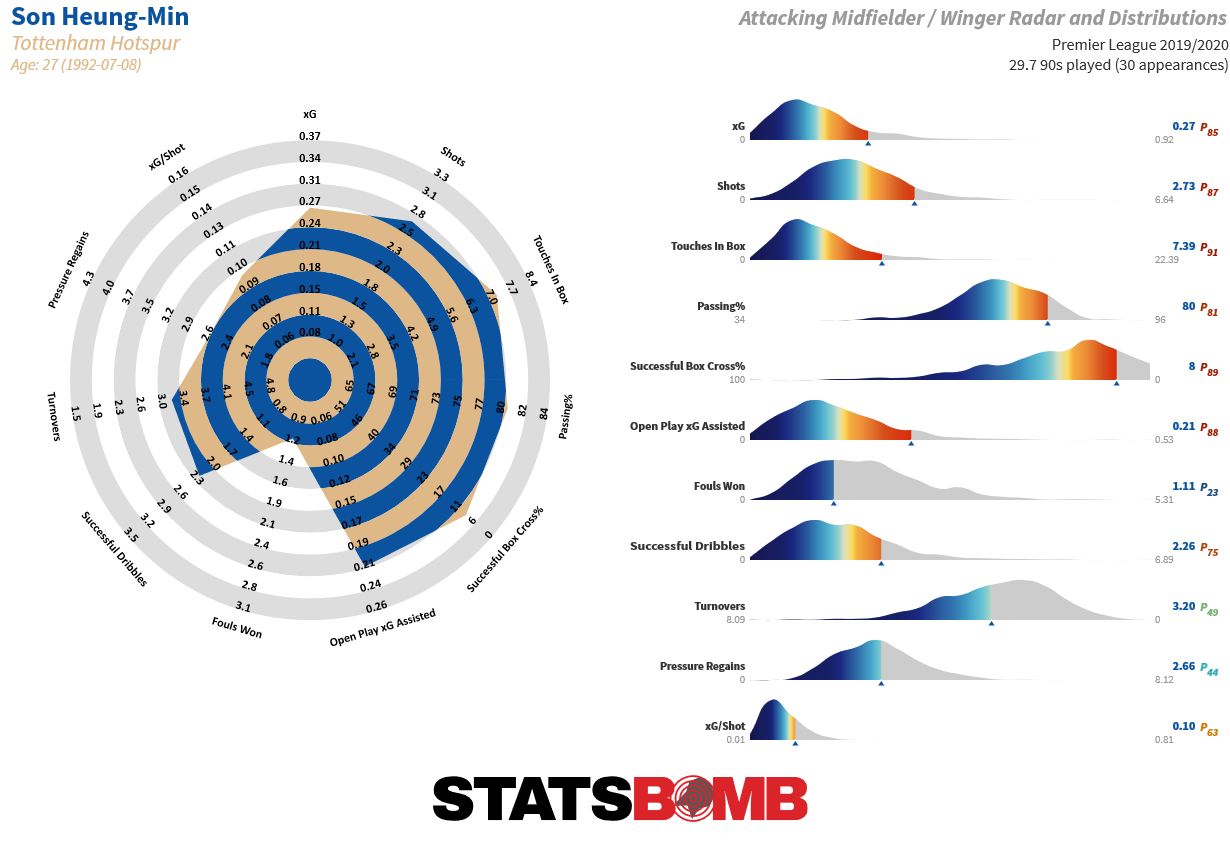

Will it work? Getting Højbjerg in as a likely guaranteed starter means we're unlikely to see Harry Winks and Moussa Sissoko start many games together with Giovani Lo Celso already the passing heartbeat of the side picked ahead of them. Doherty's arrival allows Aurier to depart and locks down one position. The attacking midfield band is rich with Dele Alli, Bergwijn, Moura, Son and Erik Lamela competing for a maximum of three positions. What of Tanguy Ndombélé? I'll plead the fifth, thanks. It's possible that the Frenchman's inability to nail down a starting place is indicative of the slightly altered transfer focus, as his signing combined with an investment in Jack Clarke and Ryan Sessegnon that is a long way off bearing fruit means £100m of summer 2019 purchases are not yet directly impacting the first team. Doherty and Højbjerg scope out at around £30m (and books are balancing a little more once Kyle Walker-Peters' departure is factored in) and will likely play every week. Getting purchases into the team and contributing counts for a lot. There are noises that more players could arrive, most notably a rotational striker, but in Covid-19 world, it's likely to be more book-balancing than big purchases, so it also depends who is on the outs. With football finishing only a month ago, we have fresh answers to long term questions. Whether Kane could refind something near to his best form after a six month break to recover from his latest injury appeared to be answered in the affirmative by a tidy finishing streak. To the casual eye he looked more dynamic than before, and whatever the truth is of his long term mobility and the impact of injuries on him, the work that he's put into his finishing over the course of many years will likely carry him well into his latter career. It's also possible that there's a bias generated in seeing him score three goals from five throughball shots as it's never been an area in which he's been wildly prolific (10 goals from 31 such shots in the league across the previous four seasons). Still: at 2.5 shots per 90, albeit for a ten shot a game team, he needs the finishing to stay sharp to get the totals up and mini runs such as this will not persist long term:  As important is the form of Son. A beacon of consistency in the aggregate throughout the good times, and not-so-good times, he has now registered four consecutive seasons oscillating close to a combined 0.7 per 90 for goals and assists, most usually ahead of expectation thanks to his versatile finishing. He can blow hot and cold at times from week to week, but when on-song, is as devastating an attacking midfielder as there is in the league:

As important is the form of Son. A beacon of consistency in the aggregate throughout the good times, and not-so-good times, he has now registered four consecutive seasons oscillating close to a combined 0.7 per 90 for goals and assists, most usually ahead of expectation thanks to his versatile finishing. He can blow hot and cold at times from week to week, but when on-song, is as devastating an attacking midfielder as there is in the league:  Projection Everything from a metric perspective at Tottenham has pointed downwards since the end of 2017-18, so the first thing to try and do is reverse that slide. Can Mourinho do that? His Zlatan-powered first Manchester United season was a legitimately dominant shooting team with a finishing problem, so there's a blueprint to get to a position of strength. The following season United finished second with 81 points despite less impressive metrics and season three is a well worn trail now. It's just about possible to give the benefit of the doubt and offer a pass for 2019-20 given weird circumstances and a mid-season appointment, but Tottenham will need to start well to keep any goodwill in the tank, and the Amazon documentary is dropping and building a whole new set of memes and storylines just as this season emerges. It's the Jose Mourinho Show again, and he needs to show he can still provide an above average return for his salary. Mourinho-era metrics don't yet offer solid encouragement, given how variable they have been. Teams with minus expected goal differences and minus shot counts simply don't earn high league positions in this league. The Sporting Index projection has Arsenal and Tottenham in the fifth and sixth slots, but no more than a result or two from below and significantly further away from Chelsea and Manchester United in the backend of the top four. Somewhere in the top four does represent the very best outcome, and a plan realised, but it is not the most likely outcome at all. However, if Tottenham can improve metrics and somehow stay in range of such an outcome deep into the season, all good, if not, then the Mourinho project may founder ahead of any expected three year timeline.

Projection Everything from a metric perspective at Tottenham has pointed downwards since the end of 2017-18, so the first thing to try and do is reverse that slide. Can Mourinho do that? His Zlatan-powered first Manchester United season was a legitimately dominant shooting team with a finishing problem, so there's a blueprint to get to a position of strength. The following season United finished second with 81 points despite less impressive metrics and season three is a well worn trail now. It's just about possible to give the benefit of the doubt and offer a pass for 2019-20 given weird circumstances and a mid-season appointment, but Tottenham will need to start well to keep any goodwill in the tank, and the Amazon documentary is dropping and building a whole new set of memes and storylines just as this season emerges. It's the Jose Mourinho Show again, and he needs to show he can still provide an above average return for his salary. Mourinho-era metrics don't yet offer solid encouragement, given how variable they have been. Teams with minus expected goal differences and minus shot counts simply don't earn high league positions in this league. The Sporting Index projection has Arsenal and Tottenham in the fifth and sixth slots, but no more than a result or two from below and significantly further away from Chelsea and Manchester United in the backend of the top four. Somewhere in the top four does represent the very best outcome, and a plan realised, but it is not the most likely outcome at all. However, if Tottenham can improve metrics and somehow stay in range of such an outcome deep into the season, all good, if not, then the Mourinho project may founder ahead of any expected three year timeline.

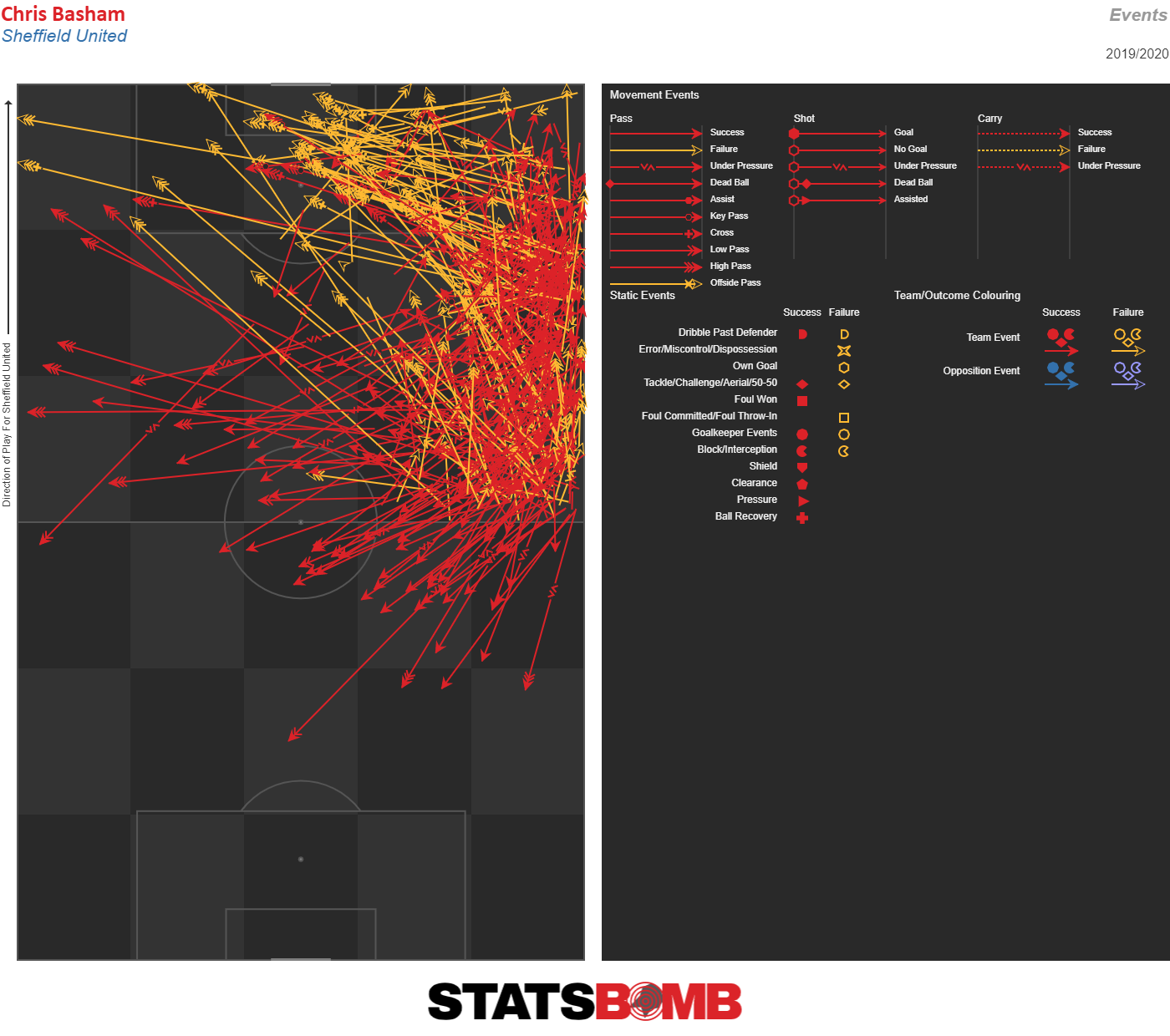

Having a laser-focus on creating quality opportunities negated the fact that they actually took the fewest shots in the league, only adding to the novelty of the Blades’ methods – creating fewer shots than all three relegated sides and the rest is not something you’d associate with a team pushing for European qualification but, unusual though it may be, it did the job. The reason for this ‘low volume / high quality’ aspect of their attacking play is their propensity for crossing both from deep and through combinations to get to the byline. Tough passes to execute but often leading to chances from central areas and close to goal when they did connect. Their wing play and crossing approach was ably supported, of course, by – get your klaxons ready people – the overlapping centre backs. Player of the year Chris Basham’s performances have led to the Bramall Lane stands christening his position the ‘Basham role’, and his pass map from right and central areas in the opposition half highlight how often he got forward to add extra numbers to United’s play in the attacking phase.

Having a laser-focus on creating quality opportunities negated the fact that they actually took the fewest shots in the league, only adding to the novelty of the Blades’ methods – creating fewer shots than all three relegated sides and the rest is not something you’d associate with a team pushing for European qualification but, unusual though it may be, it did the job. The reason for this ‘low volume / high quality’ aspect of their attacking play is their propensity for crossing both from deep and through combinations to get to the byline. Tough passes to execute but often leading to chances from central areas and close to goal when they did connect. Their wing play and crossing approach was ably supported, of course, by – get your klaxons ready people – the overlapping centre backs. Player of the year Chris Basham’s performances have led to the Bramall Lane stands christening his position the ‘Basham role’, and his pass map from right and central areas in the opposition half highlight how often he got forward to add extra numbers to United’s play in the attacking phase.  Of course, there’s little reason to focus on their attacking play when it’s the defence that powered the Blades to their lofty finish. Conceding just 39 goals as a newly promoted team, a number bettered only by the eventual top three, takes some doing. Creating openings did not come easy to their opponents, even the “Ferraris”: games against Chelsea, Spurs and Arsenal returned three wins, three draws, no defeats. Three elements forged this Steel City defence. The first was limiting the opportunities their opposition were able to generate, with the sheer number of bodies United would have in the centre of the park both in the defensive and the midfield lines often doing a fine job of congesting that area and forcing the opposition to look for openings elsewhere – the 11.32 shots conceded per game was 8th fewest. Of the sides that had a better record, only Everton finished below them.

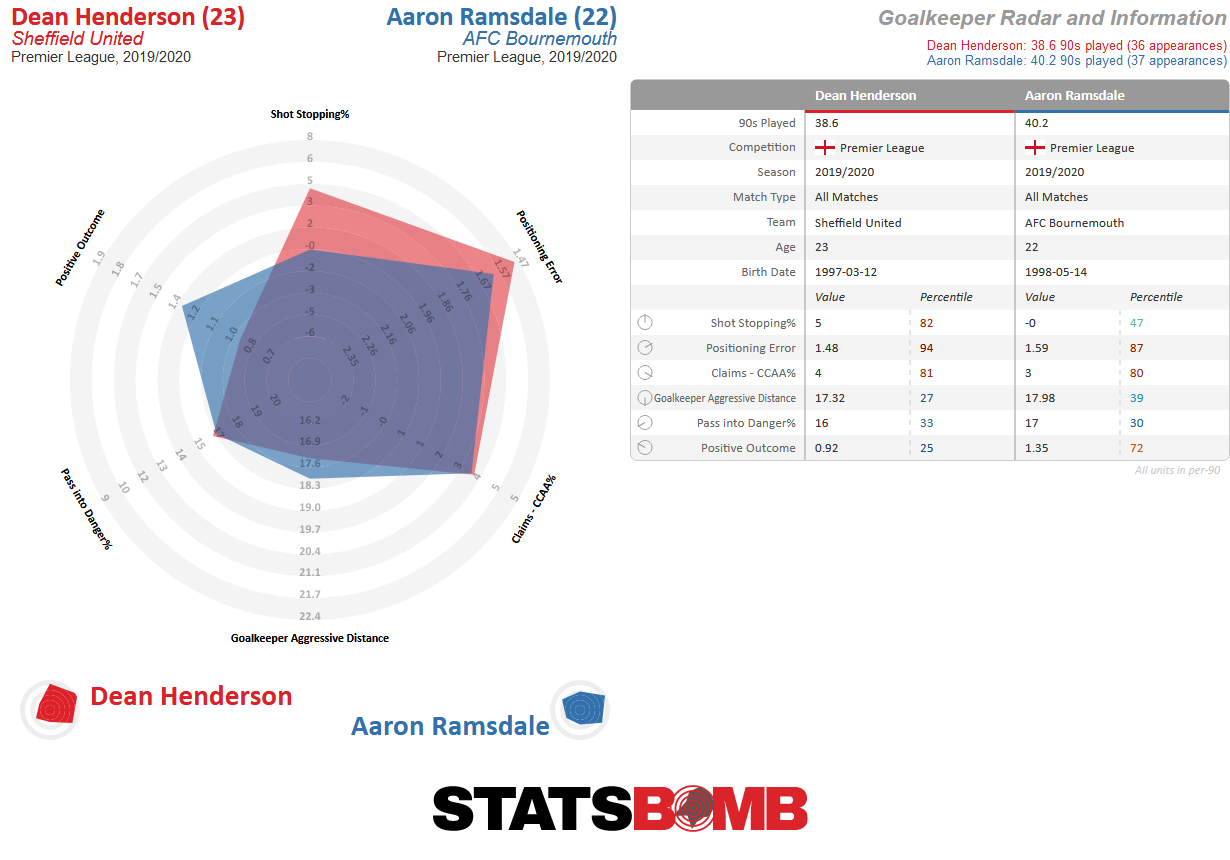

Of course, there’s little reason to focus on their attacking play when it’s the defence that powered the Blades to their lofty finish. Conceding just 39 goals as a newly promoted team, a number bettered only by the eventual top three, takes some doing. Creating openings did not come easy to their opponents, even the “Ferraris”: games against Chelsea, Spurs and Arsenal returned three wins, three draws, no defeats. Three elements forged this Steel City defence. The first was limiting the opportunities their opposition were able to generate, with the sheer number of bodies United would have in the centre of the park both in the defensive and the midfield lines often doing a fine job of congesting that area and forcing the opposition to look for openings elsewhere – the 11.32 shots conceded per game was 8th fewest. Of the sides that had a better record, only Everton finished below them.  The second element? Dean Henderson. When their opponents did generate a shot, they often found the Manchester United loanee in the sort of form that catapulted him into immediate England contention, earning him a first senior callup in October. Henderson particularly excelled in the old-fashioned arts of goalkeeping: taking pressure off the defence by claiming crosses and making saves that you shouldn’t necessarily expect him to make. Lastly, the Blades performed well on set play’s once again, though this time the acclaim comes on the defensive end, tying with Leicester for the fewest set play goals conceded with 6. When combined, these elements made for a stubborn defence that gave United a reasonable chance of taking a result from virtually every game they played in the 2019/20 season. Unfortunately, Henderson’s form was too good for the decision makers at Old Trafford to ignore and he looks set to compete with David De Gea for the #1 jersey there in 2020/21. Wilder and his recruitment team moved quickly to replace him, spending £18.5 million on bringing Aaron Ramsdale in from relegated Bournemouth. Not far behind Henderson in the England pecking order, Ramsdale will be hoping he can follow in his predecessor’s footsteps and comes with decent pedigree and an upwardly mobile trajectory mirroring that of his new club; capped 26 times in England’s age group squads and also comes in on the back of winning Young Player of the Year at AFC Wimbledon in 2018/19 and Supporters Player of the Year at Bournemouth in 2019/20.

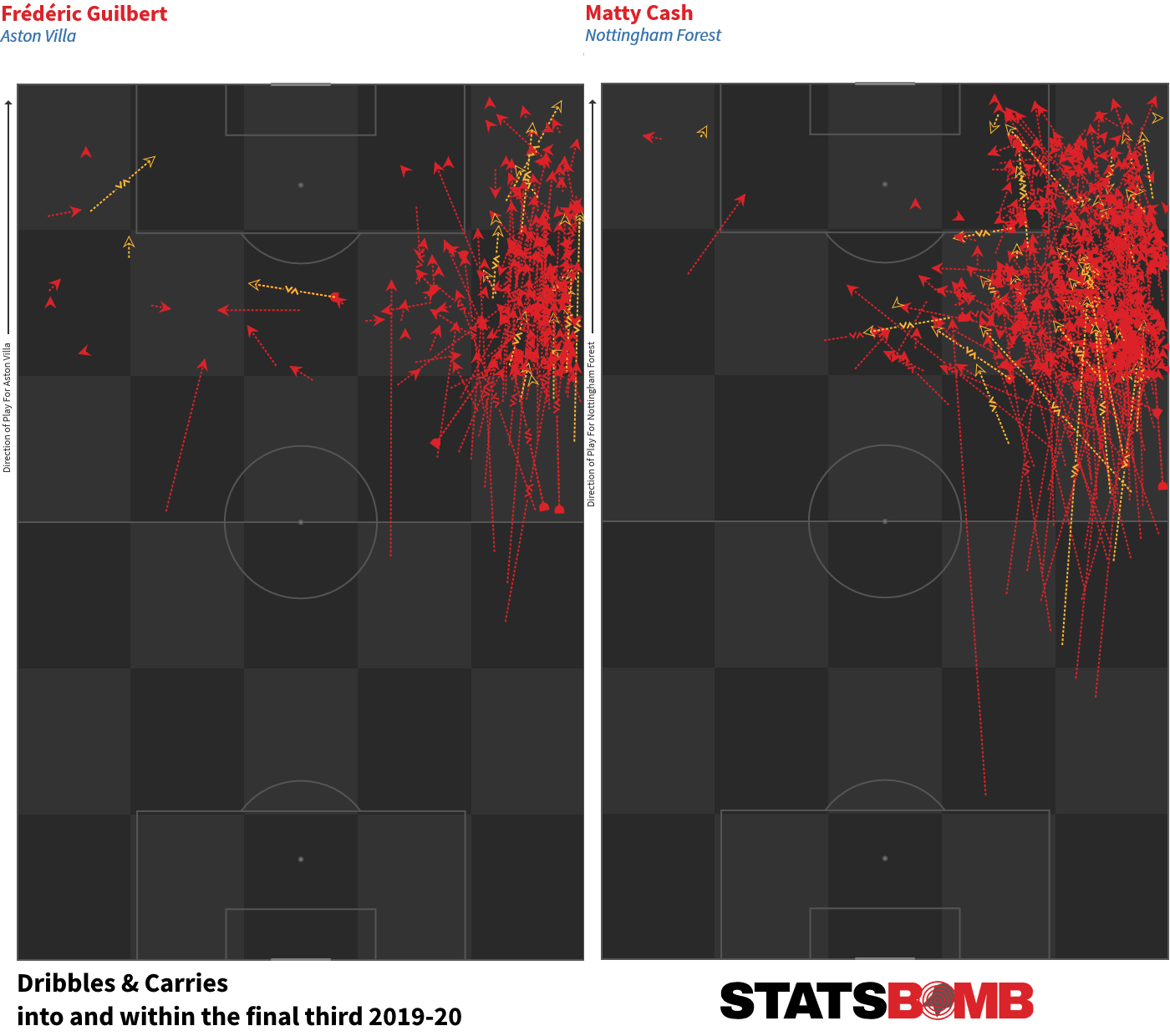

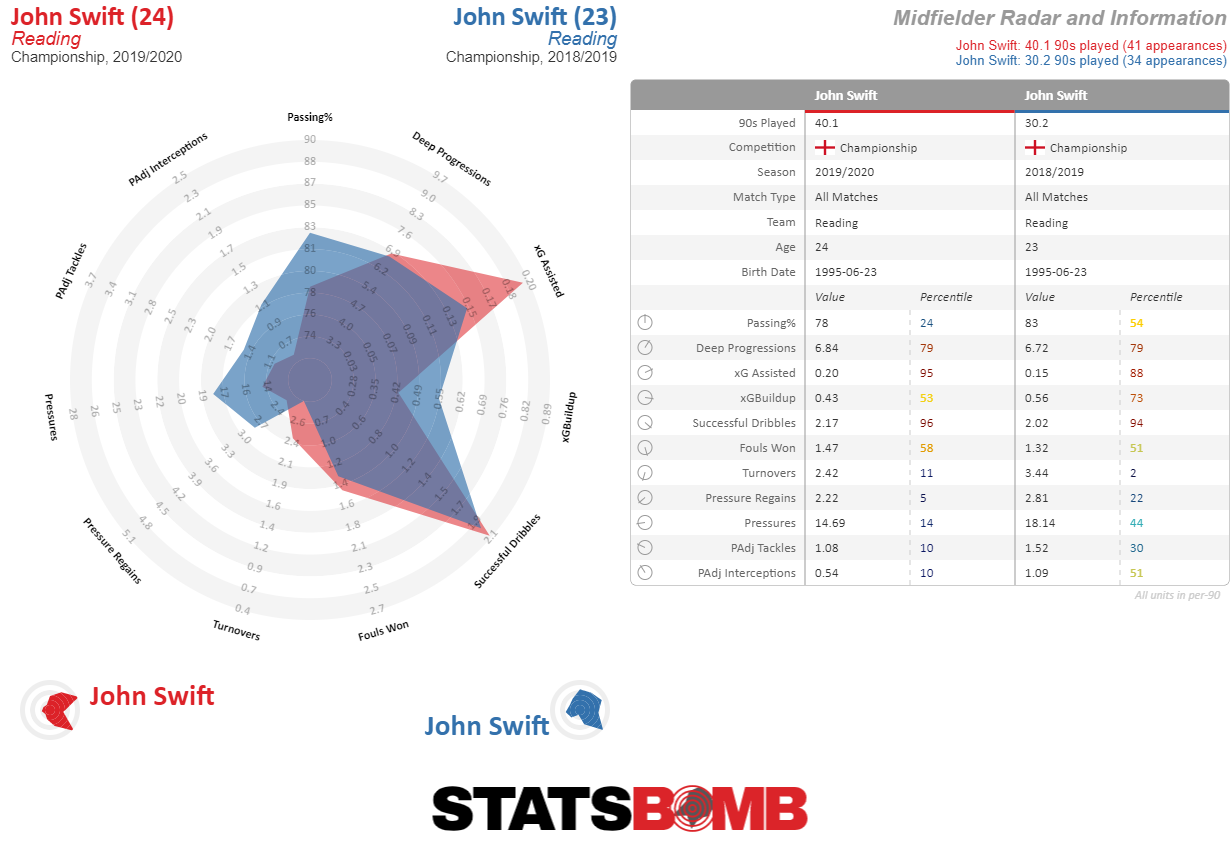

The second element? Dean Henderson. When their opponents did generate a shot, they often found the Manchester United loanee in the sort of form that catapulted him into immediate England contention, earning him a first senior callup in October. Henderson particularly excelled in the old-fashioned arts of goalkeeping: taking pressure off the defence by claiming crosses and making saves that you shouldn’t necessarily expect him to make. Lastly, the Blades performed well on set play’s once again, though this time the acclaim comes on the defensive end, tying with Leicester for the fewest set play goals conceded with 6. When combined, these elements made for a stubborn defence that gave United a reasonable chance of taking a result from virtually every game they played in the 2019/20 season. Unfortunately, Henderson’s form was too good for the decision makers at Old Trafford to ignore and he looks set to compete with David De Gea for the #1 jersey there in 2020/21. Wilder and his recruitment team moved quickly to replace him, spending £18.5 million on bringing Aaron Ramsdale in from relegated Bournemouth. Not far behind Henderson in the England pecking order, Ramsdale will be hoping he can follow in his predecessor’s footsteps and comes with decent pedigree and an upwardly mobile trajectory mirroring that of his new club; capped 26 times in England’s age group squads and also comes in on the back of winning Young Player of the Year at AFC Wimbledon in 2018/19 and Supporters Player of the Year at Bournemouth in 2019/20.  To date, only Wes Foderingham as a backup ‘keeper has followed Ramsdale through the door, but it’s clear that the Blades will be targeting a bit more quality in the middle and top end of the pitch in order to enhance their attacking output. Links with Matty Cash who had an impressive season for Nottingham Forest make sense – the winger-turned-right-back would provide quality in the final third, though the intensity of those links seem to have died down in recent weeks. A deal for Reading’s John Swift would also add some much-needed creativity to the Blades midfield line and could make the difference in games when they’re on top and in search of a breakthrough. Swift’s last two seasons in the Championship have seen him regularly demonstrate his creative capabilities, but he also has a dribbling ability that has been missing from Sheffield United’s arsenal in the last couple of seasons.

To date, only Wes Foderingham as a backup ‘keeper has followed Ramsdale through the door, but it’s clear that the Blades will be targeting a bit more quality in the middle and top end of the pitch in order to enhance their attacking output. Links with Matty Cash who had an impressive season for Nottingham Forest make sense – the winger-turned-right-back would provide quality in the final third, though the intensity of those links seem to have died down in recent weeks. A deal for Reading’s John Swift would also add some much-needed creativity to the Blades midfield line and could make the difference in games when they’re on top and in search of a breakthrough. Swift’s last two seasons in the Championship have seen him regularly demonstrate his creative capabilities, but he also has a dribbling ability that has been missing from Sheffield United’s arsenal in the last couple of seasons.  A refresh will also be needed up top soon, if not now. Despite his

A refresh will also be needed up top soon, if not now. Despite his

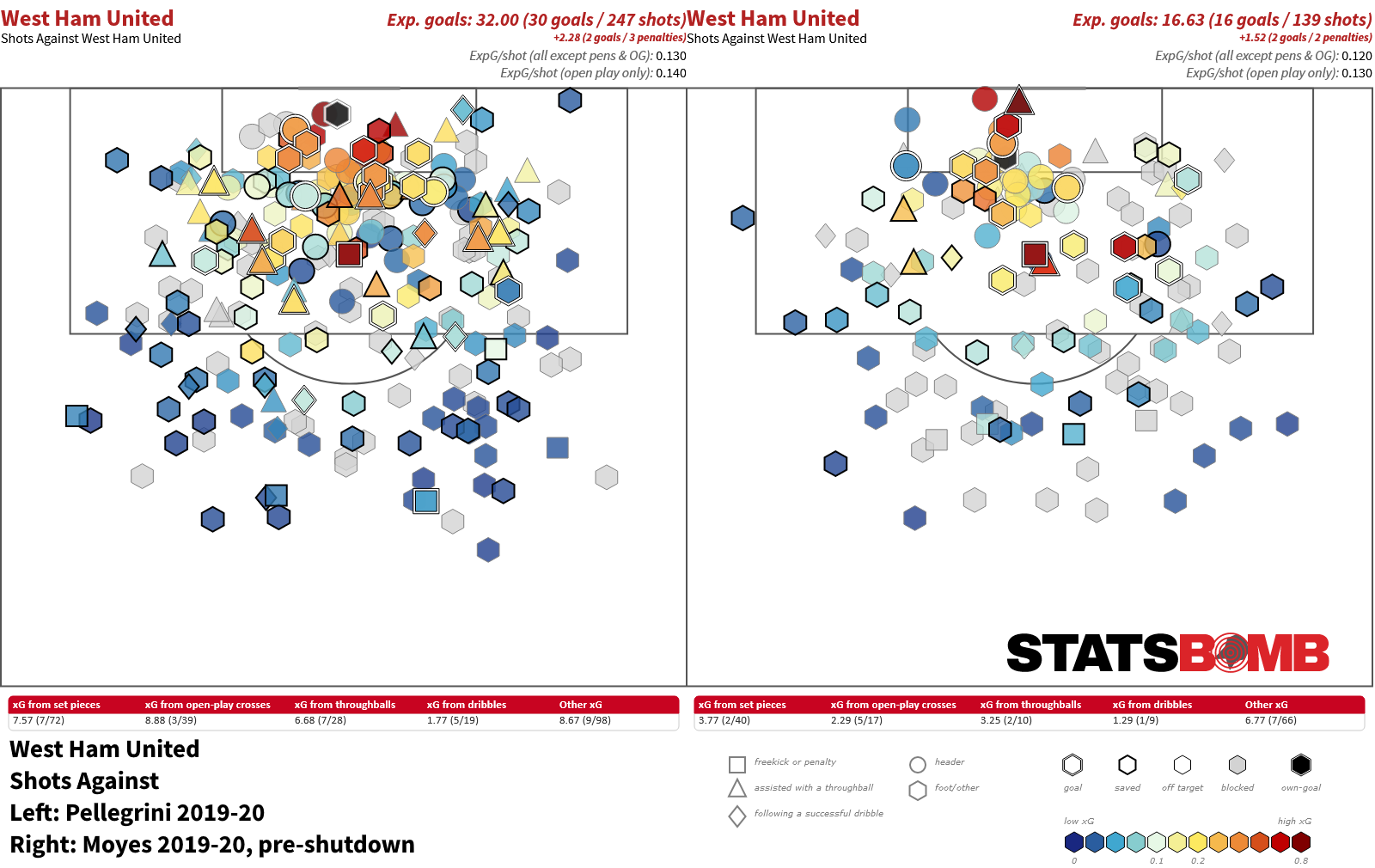

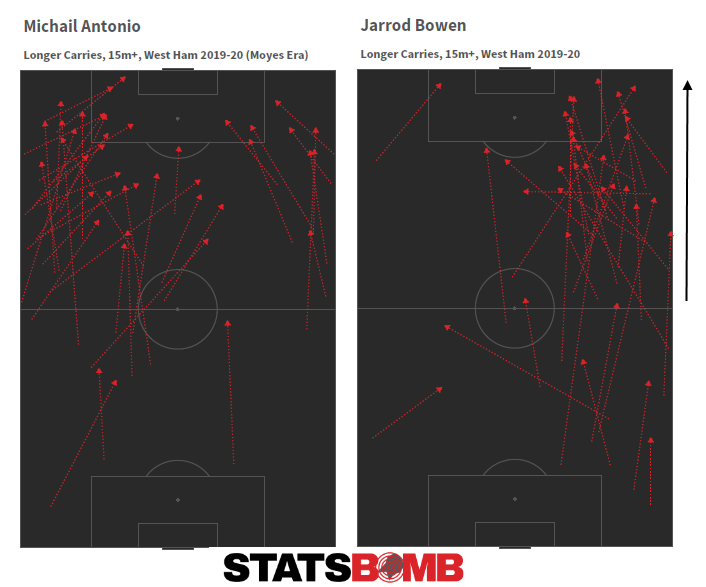

It’s an open question what may have happened to West Ham’s season had the viral intervention not occurred. The team were in sixteenth on 27 points, level with Watford and Bournemouth in seventeenth and eighteenth and with nine games left to rescue themselves from possible relegation. It's also an open question as to how reliable the form is of this concentrated post-lockdown period. Oddly, since leaving Everton and starting at Manchester United, Moyes has had four further managerial tenures, and apart from the summer of 2015 while in charge of Real Sociedad, the Covid break has been the only time he has had an extended period as a manager outside the grind of regular in season games. And given three months to prepare, Moyes managed to hit upon something that worked. The initial Moyes period did have the misfortune of some schedule stacking--they faced Liverpool twice, and Manchester City-- so there is room for some caution when considering the apparent improvement the team made, but he chopped and changed his formations in that early run, and post-lockdown stuck with a 4-2-3-1. As the season wound up, his starting eleven became more consistent too: Łukasz Fabiański in goal, a back four of Ryan Fredricks, Issa Diop, Angelo Ogbonna, Aaron Cresswell, Declan Rice and Tomáš Souček sitting, Pablo Fornals or Manuel Lanzini left, Jarrod Bowen right, Mark Noble's aging legs parked upfield as an attacking midfielder, at least in name, and Michail Antonio up front. This left a selection of expensive potential game-changers often manning the bench. Sébastien Haller, Andriy Yarmolenko and Felipe Anderson's combined cost was around £100m and they watched a good deal of football in those final weeks, occasionally, pitching in late on in games. The players that benefited most from Moyes' June reboot were the two January signings, Bowen and Souček and converted striker Antonio. Souček is a fascinating player for a central midfielder as despite many column inches being spent on the possibility of his midfield partner Rice becoming a centre back, at least from a data perspective he looks to have more centre back aligned tools. No central midfielder in the league got anywhere near his 5.1 aerial wins per 90 (next best was Phillip Billing at 3.4). He's also useful at the other end of the pitch as a goal threat in open play and from set-pieces having scored 30 goals in his last two seasons at Slavia Prague. He's added three more since arriving in England. He's a curious passer for a defensive midfielder too. Keeping the ball on the deck and playing short, he's just about secure enough (he completed over 90% of passes, still less than Rice's 95%) but as soon as he puts the ball forward and in the air it drops to 40% (down from 60% at Slavia). Quick analysis suggests that quite a lot of these failed attempts are out balls aimed at Antonio or Bowen, and Rice scopes out better at those too. Add Noble into the mix, who nominally played in the middle of the attacking midfield band as the season drew to a close, but effectively sat a lot closer to the other two defensive midfielders, and we see a clear strategy--find Antonio or Bowen if you can--that is effective only sporadically. Just 28% of high and longer passes from their own half forward and into the opponent half are finding their intended target. All this feeds into the idea of what you can get from Bowen and Antonio. Each is effective at carrying the ball deep into opposition territory (as is Felipe Anderson, moreso even, across the whole season, he ranks second behind Adama Traoré for these long carries) and are a danger to the opponent's goal:

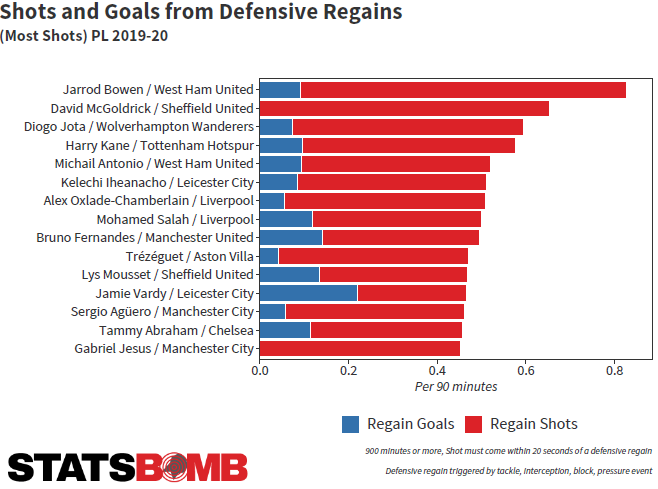

It’s an open question what may have happened to West Ham’s season had the viral intervention not occurred. The team were in sixteenth on 27 points, level with Watford and Bournemouth in seventeenth and eighteenth and with nine games left to rescue themselves from possible relegation. It's also an open question as to how reliable the form is of this concentrated post-lockdown period. Oddly, since leaving Everton and starting at Manchester United, Moyes has had four further managerial tenures, and apart from the summer of 2015 while in charge of Real Sociedad, the Covid break has been the only time he has had an extended period as a manager outside the grind of regular in season games. And given three months to prepare, Moyes managed to hit upon something that worked. The initial Moyes period did have the misfortune of some schedule stacking--they faced Liverpool twice, and Manchester City-- so there is room for some caution when considering the apparent improvement the team made, but he chopped and changed his formations in that early run, and post-lockdown stuck with a 4-2-3-1. As the season wound up, his starting eleven became more consistent too: Łukasz Fabiański in goal, a back four of Ryan Fredricks, Issa Diop, Angelo Ogbonna, Aaron Cresswell, Declan Rice and Tomáš Souček sitting, Pablo Fornals or Manuel Lanzini left, Jarrod Bowen right, Mark Noble's aging legs parked upfield as an attacking midfielder, at least in name, and Michail Antonio up front. This left a selection of expensive potential game-changers often manning the bench. Sébastien Haller, Andriy Yarmolenko and Felipe Anderson's combined cost was around £100m and they watched a good deal of football in those final weeks, occasionally, pitching in late on in games. The players that benefited most from Moyes' June reboot were the two January signings, Bowen and Souček and converted striker Antonio. Souček is a fascinating player for a central midfielder as despite many column inches being spent on the possibility of his midfield partner Rice becoming a centre back, at least from a data perspective he looks to have more centre back aligned tools. No central midfielder in the league got anywhere near his 5.1 aerial wins per 90 (next best was Phillip Billing at 3.4). He's also useful at the other end of the pitch as a goal threat in open play and from set-pieces having scored 30 goals in his last two seasons at Slavia Prague. He's added three more since arriving in England. He's a curious passer for a defensive midfielder too. Keeping the ball on the deck and playing short, he's just about secure enough (he completed over 90% of passes, still less than Rice's 95%) but as soon as he puts the ball forward and in the air it drops to 40% (down from 60% at Slavia). Quick analysis suggests that quite a lot of these failed attempts are out balls aimed at Antonio or Bowen, and Rice scopes out better at those too. Add Noble into the mix, who nominally played in the middle of the attacking midfield band as the season drew to a close, but effectively sat a lot closer to the other two defensive midfielders, and we see a clear strategy--find Antonio or Bowen if you can--that is effective only sporadically. Just 28% of high and longer passes from their own half forward and into the opponent half are finding their intended target. All this feeds into the idea of what you can get from Bowen and Antonio. Each is effective at carrying the ball deep into opposition territory (as is Felipe Anderson, moreso even, across the whole season, he ranks second behind Adama Traoré for these long carries) and are a danger to the opponent's goal:  Once they have the ball, there's a good chance you'll see a shot at the end of it. One of Bowen's known weaknesses is shot selection, but from enforced turnovers, his rate of getting shots (any kind) leads the league, with Antonio not that far behind:

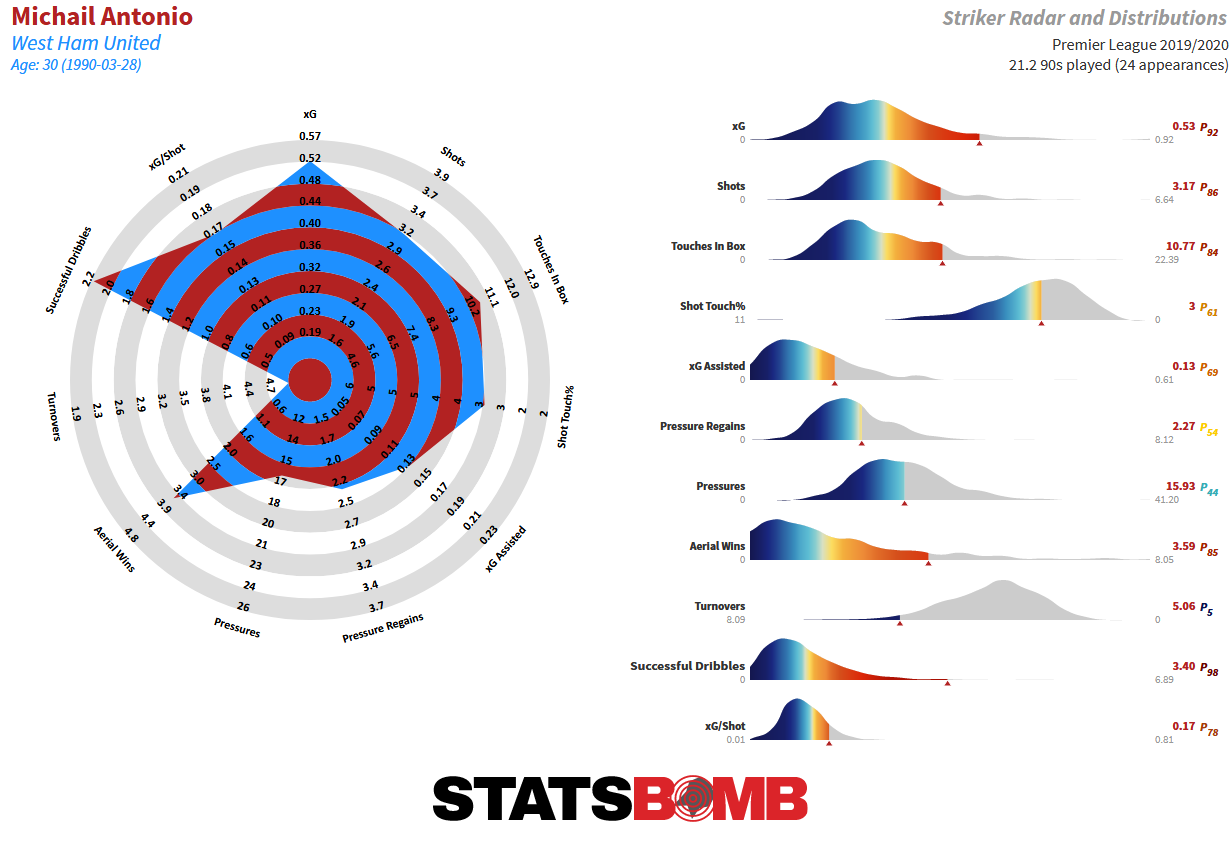

Once they have the ball, there's a good chance you'll see a shot at the end of it. One of Bowen's known weaknesses is shot selection, but from enforced turnovers, his rate of getting shots (any kind) leads the league, with Antonio not that far behind:  So Moyesball 2.0 is thus: defence first, a defensive midfielder with centre back qualities and an eye for goal, a converted passing defensive midfielder in the 10 slot and targeting zone movers to get the ball up the pitch and shoot. The result of this was spectacular for Antonio, who was second only to Raheem Sterling for xG per 90 after the restart. Once more reborn as a striker, he was more than a handful:

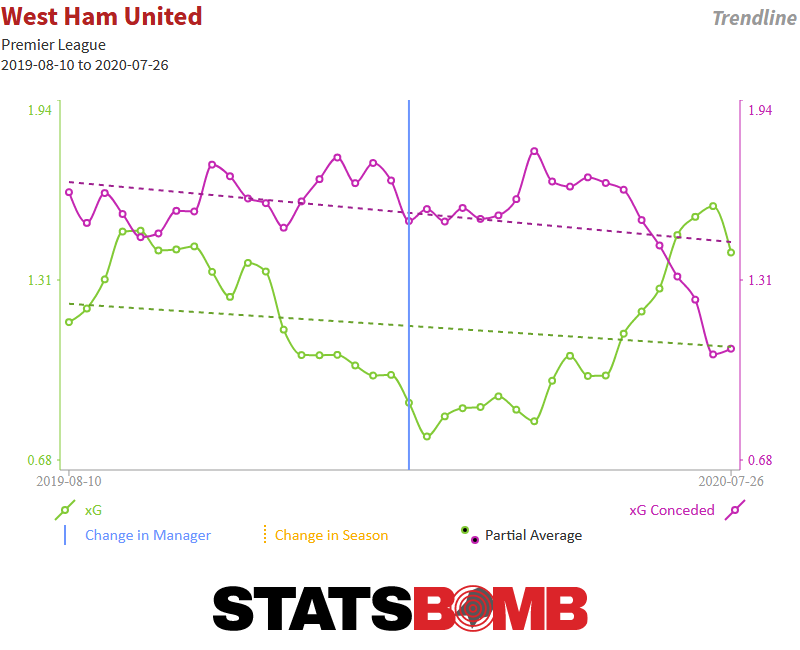

So Moyesball 2.0 is thus: defence first, a defensive midfielder with centre back qualities and an eye for goal, a converted passing defensive midfielder in the 10 slot and targeting zone movers to get the ball up the pitch and shoot. The result of this was spectacular for Antonio, who was second only to Raheem Sterling for xG per 90 after the restart. Once more reborn as a striker, he was more than a handful:  Even if we unfairly disregard his four-goal, nine shot, 2.1 xG game against Norwich, he still scopes out very well. A shade under three shots and 0.55 xG per 90 in the Moyes era is everything you want from a centre forward on a non-elite team. It will be hard to keep him out of the starting line-up when the league resumes providing an injury sustained in a warm-up match against Brentford does not persist. The period of summer football saw West Ham pick up twelve points from nine games. Not bad. But among that their metrics took a huge u-turn moving from "actually bad" to "really quite good":

Even if we unfairly disregard his four-goal, nine shot, 2.1 xG game against Norwich, he still scopes out very well. A shade under three shots and 0.55 xG per 90 in the Moyes era is everything you want from a centre forward on a non-elite team. It will be hard to keep him out of the starting line-up when the league resumes providing an injury sustained in a warm-up match against Brentford does not persist. The period of summer football saw West Ham pick up twelve points from nine games. Not bad. But among that their metrics took a huge u-turn moving from "actually bad" to "really quite good":  Post-lockdown xG difference was around +0.3 per 90, and goal difference matched it. The key to this defensively was the opposition shot quality finally taking a positive hit. It crashed down to 0.09 per shot. This shaved around a third off versus their season long xG Against during this period, and they also had the better end of set-pieces, scoring four and allowing just one, in line with expectation there too. Now a lot of these movements fall into the realm of possible variance within a short period of time, but West Ham haven't see this kind of positive move in metrics for a long time. At least, for now, there can be some hope that they can continue to play the style of football they provided in the summer of 2020 and be more successful, perhaps even lift themselves out of the mix for a relegation battle. Recruitment and fitness of key men may play a part in how successful that desire is. Personnel Director of Football Mario Husillos left with Manuel Pellegrini in December 2019. His record was embodied by a lot of money spent on appealing attackers, few of which have really made enough of a mark when factored against fees spent. This senior role hasn’t subsequently been publicly filled by anyone, though somebody signed off on the transfers of Bowen and Souček in January. Moyes appeared clear minded in what he wanted to do this window in an