The brainchild of Gabriel Hanot, editor of L’Équipe, the European Cup, now known as the Champions League, very quickly established itself as the pinnacle of European club football after its introduction in 1955. Many of the sport’s greatest teams have since made concrete their legacies by lifting the famous trophy.

With the help of our data, I am going to analyse a European Cup final from each decade, from the 1960s through to the present day, looking at the trends, developments and differences over the years.

First up is Real Madrid’s 7-3 win over Eintracht Frankfurt in the 1960 final at Hampden Park in Glasgow, which remains the highest-scoring final in the history of the competition.

Real Madrid had won each of the first four editions and had lost just six times in 35 European Cup matches prior to this encounter. More than any other, they are a team defined by this competition.

Formations

This is still more or less the era of the 3-2-2-3 (WM) formation, with wingers, inside forwards and a centre-forward making up the front line. With certain variations, both teams employed that system.

A Fast and Imprecise Game

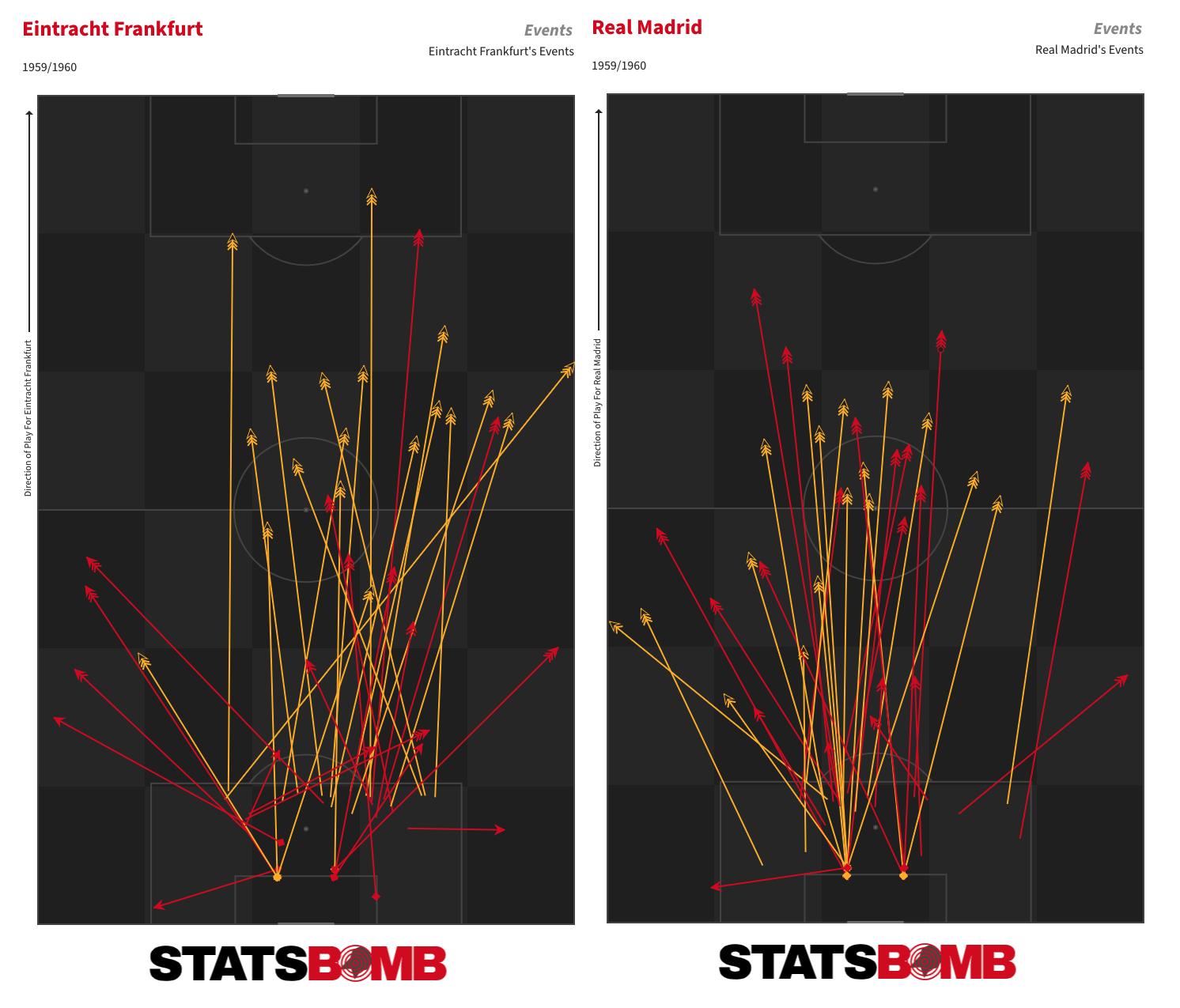

The first thing that immediately stands out is the number of times the teams turned over possession. Real Madrid completed just 69% of their passes; Frankfurt only 61%. For comparison, the average passing completion rate in last season’s Champions League was 80%. There were 483 distinct possessions in this match, compared to 374 in an average modern-day match in the competition.

In the commentary, much is made of the bumpy surface at Hampden Park. That may certainly have contributed, but those completion rates feel more like a consequence of the directness with which both teams played. This is the textbook example of a back and forth shot-fest. Upon gaining possession, both teams moved forward at a faster rate than modern-day teams, and the final shot count of 42 was 13 more than the tally in the 2018-19 final, and 15 more than last season’s competition average.

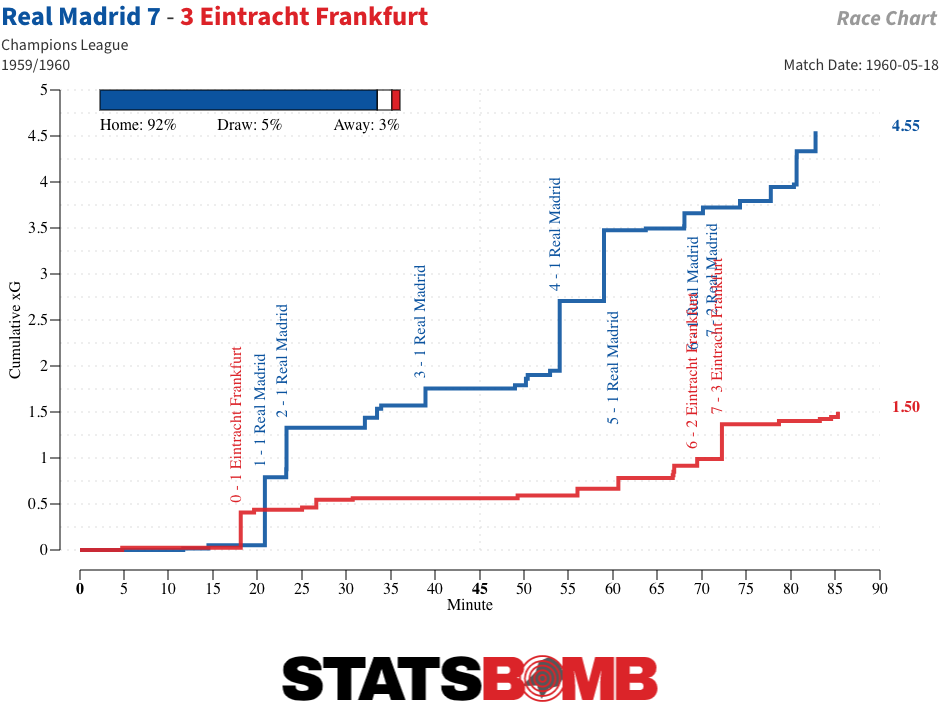

You don’t see many matches with xG sums like this these days:

This was a contest of quick passes, flick-ons and direct duels. Between them, the two teams attempted a mammoth 55 dribbles, of which 33 were completed -- itself about the average rate of attempted dribbles in last season’s competition.

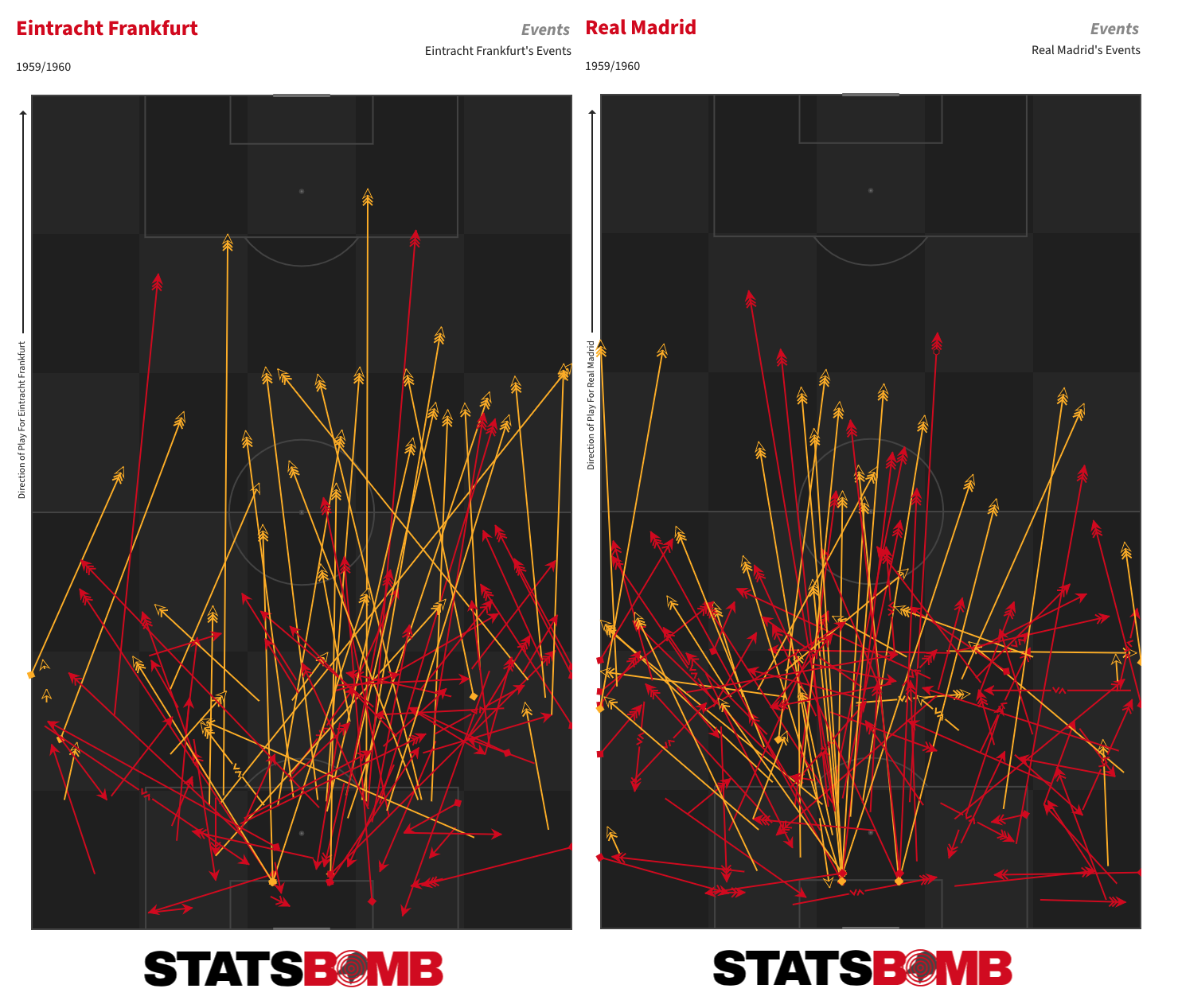

Goalkeepers Go Long

The impression I had when watching the match was that the two goalkeepers kicked long a lot more often than those of top teams in the modern game. Frankfurt’s Egon Loy got particularly impressive distance on a number of his first-half dropkicks.

The numbers bear that out. The average goalkeeper pass lengths of the large majority of teams considered viable winners of the contemporary Champions League fall within a range of about 32-40 metres. In this match, Real Madrid’s average was 48.86 metres; Frankfurt’s 50.93.

There were very few passing moves built up patiently from deeper areas. Real Madrid elaborated a little more inside their defensive third, but both teams mainly sought to quickly get the ball forward into the attacking half.

The majority of attacking moves arose from contested loose balls in the middle third of the pitch.

Alfredo Di Stéfano: All-Round Forward

Alfredo Di Stéfano perhaps deserves a more prominent place in discussions over the best player of all time. A league-title winner in three different countries and the driving force behind Madrid’s five consecutive European Cup triumphs, he was not only a prime goalscorer but also a highly adept organiser of play.

In our recent series on Lionel Messi, I mentioned that Di Stéfano was the kind of withdrawn and roving forward that we’d probably describe as a “False Nine” in modern parlance, and that is very much played out by his role in this match.

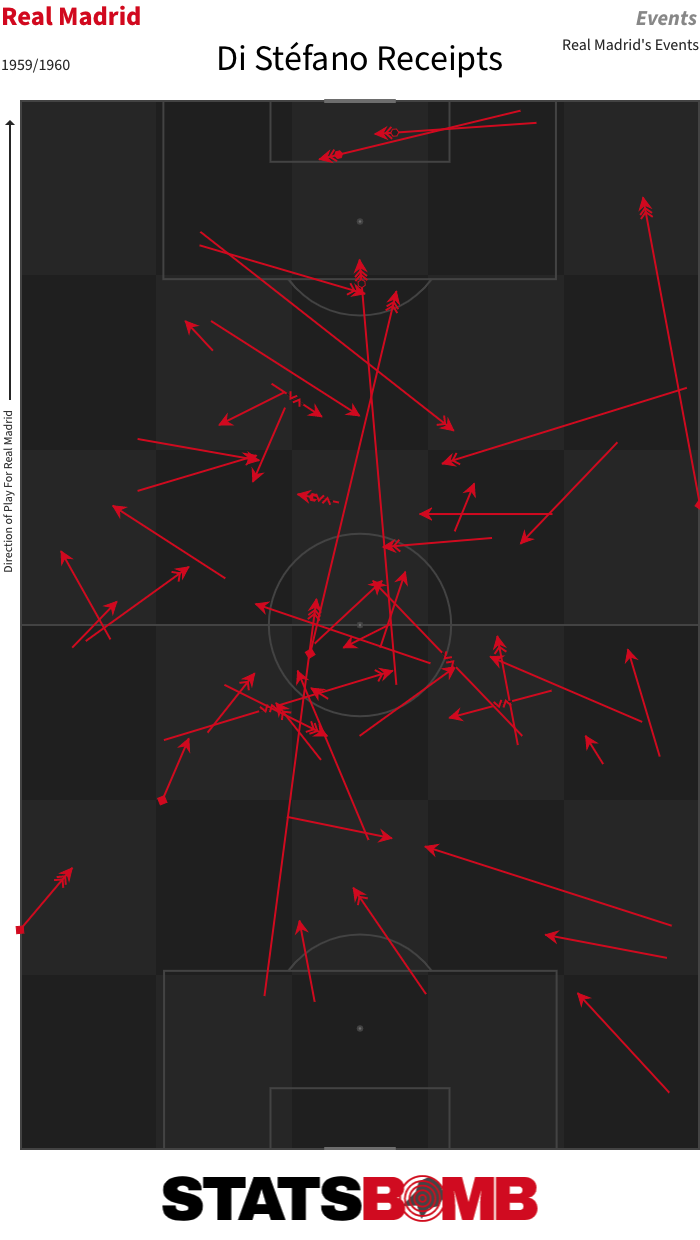

Di Stéfano’s first involvement is deep inside own half, receiving the ball from a teammate, dummying to pass and moving forward into the created space. It is a scene repeated throughout, usually accompanied by gestures of suggested movements for those around him. His receipt locations demonstrate the extent of his involvement in constructing play and bringing the ball forward.

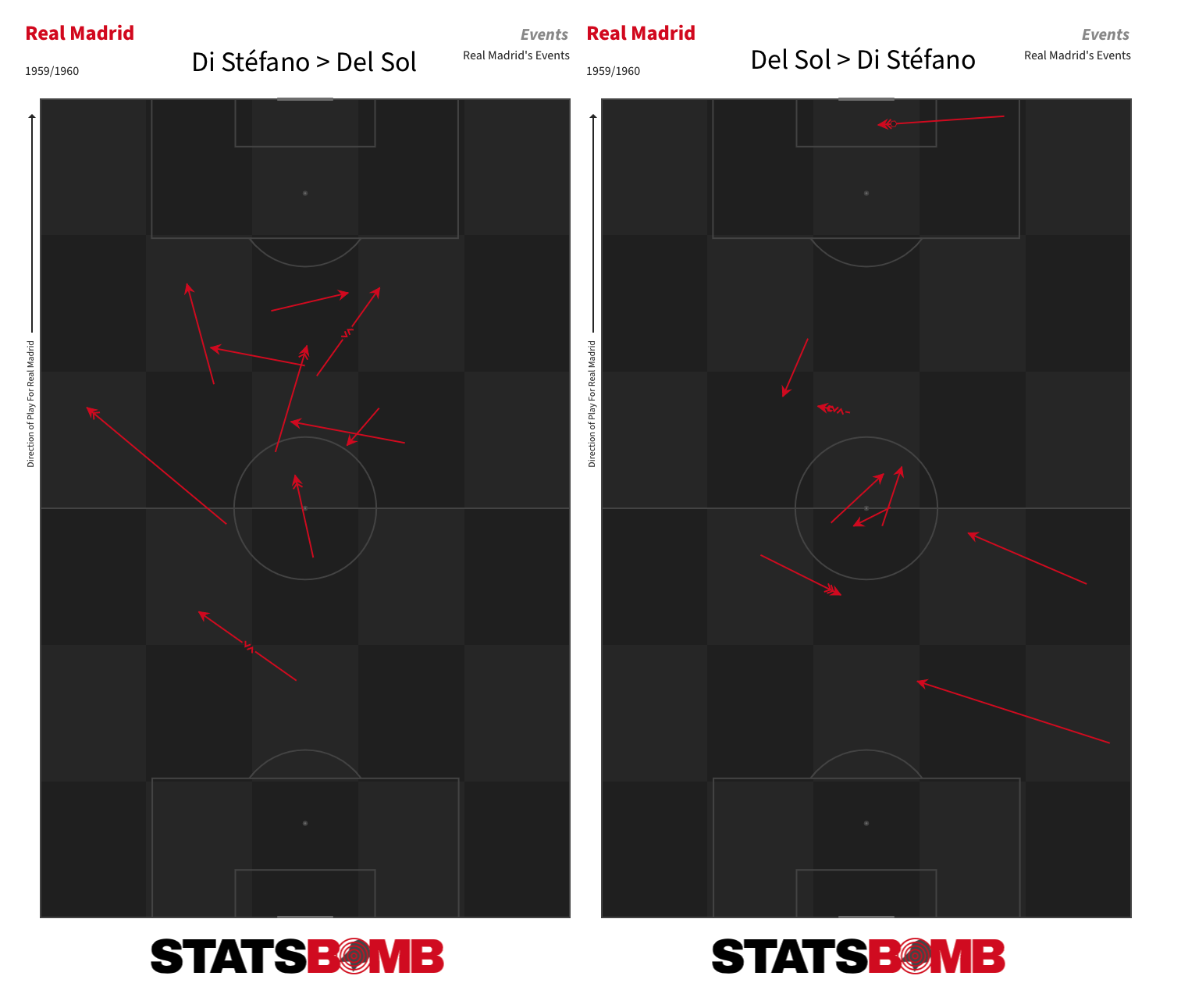

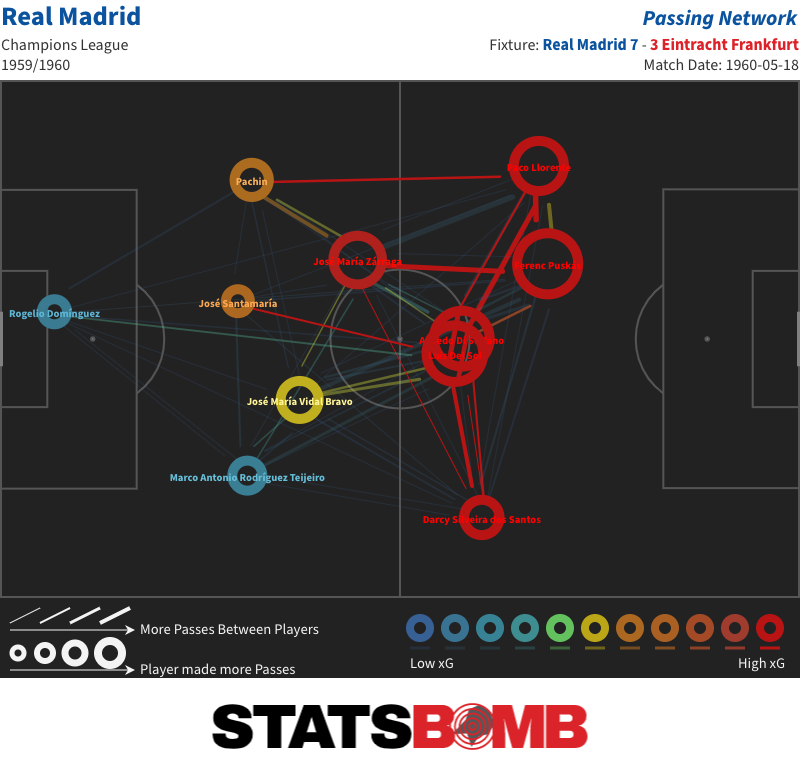

In Luis del Sol, an inside forward of energy and class, he had a key accomplice. They exchanged more passes than any other pair of players.

When Di Stéfano did appear in areas more consistent with his starting position as a centre forward, it was largely to finish from close range inside the penalty area. That was how two of his three goals arose.

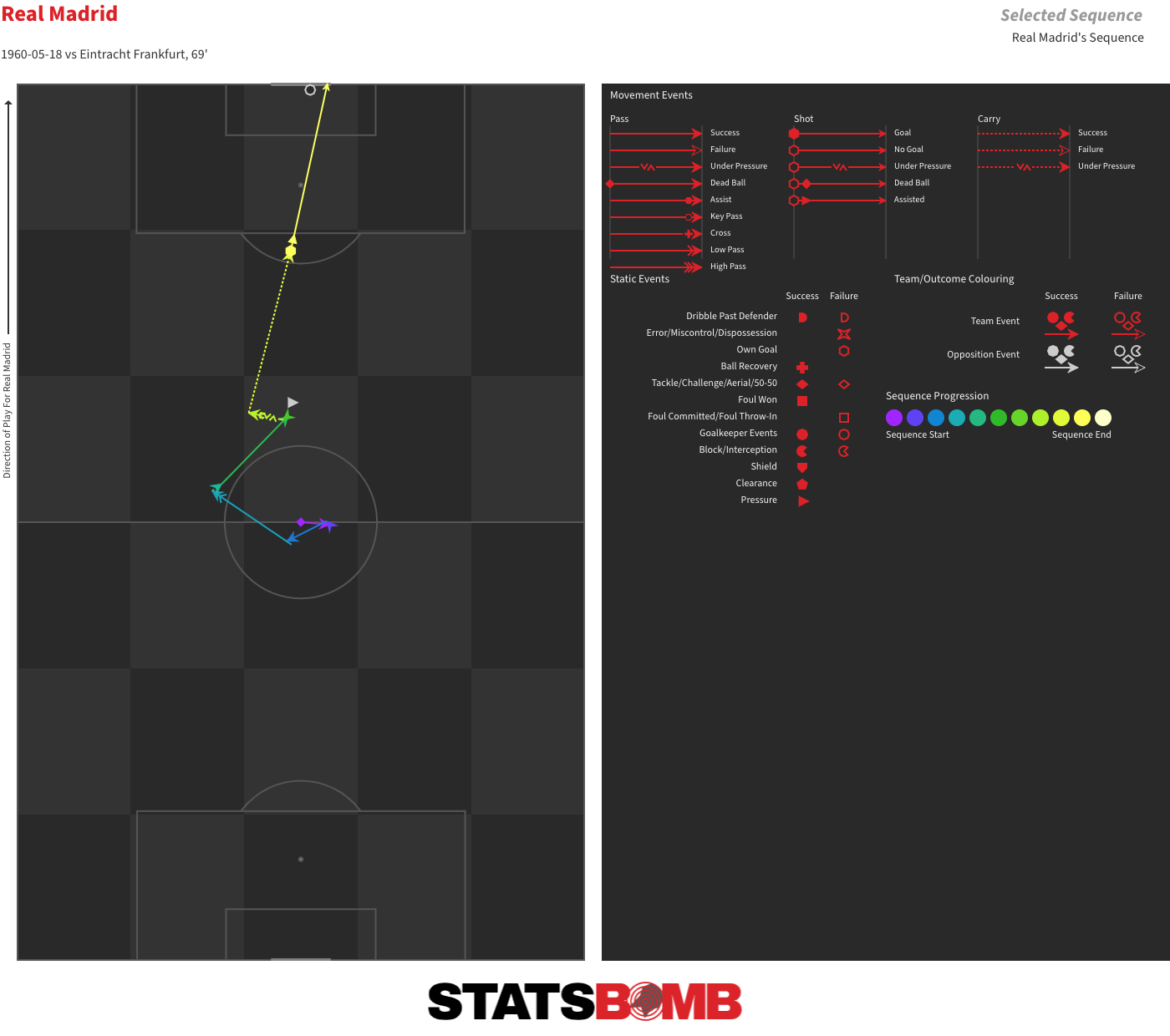

The third came from a kickoff. After exchanges with Gento and Del Sol, he accelerated through the centre of the pitch before firing home a crisp effort into the corner from outside the area. One of the great European Cup final goals.

Puskás the Sharpshooter Di Stéfano may have notched a hat-trick, but he wasn’t Madrid’s top scorer on the day. That honour fell to Ferenc Puskás, nominally the inside left but more often than not Madrid’s most advanced player.

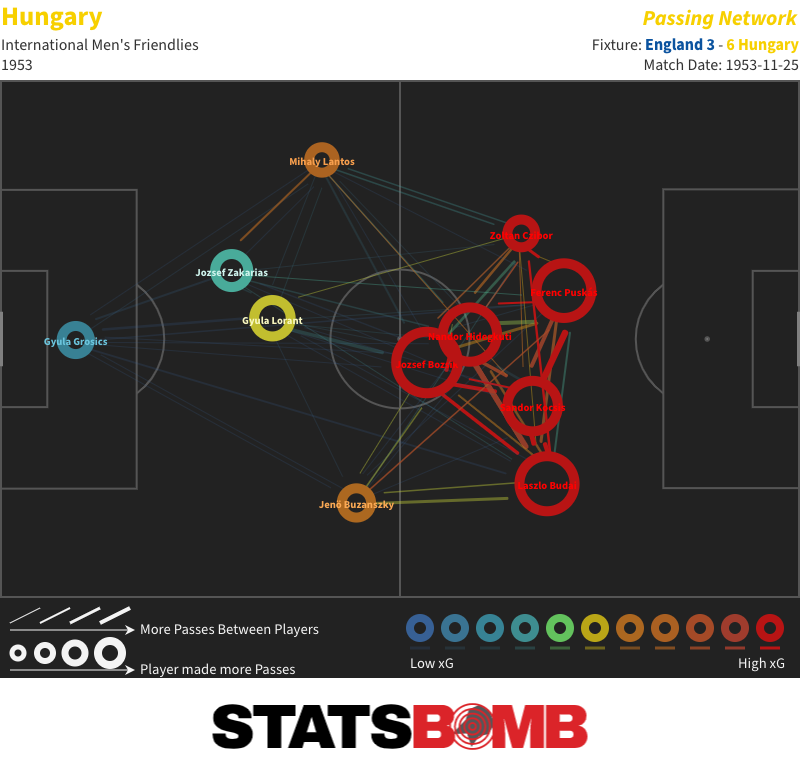

It was a role Puskás was used to performing. In the great Hungary side of the 1950s, he played alongside Nándor Hidegkuti, who, like Di Stéfano, was often more of a withdrawn playmaker than an outright centre-forward. If we look at the pass map from Hungary’s famous 6-3 win over England at Wembley in 1953, it is interesting to note just how similar the relative positioning and spacing is between Puskás and Hidegkuti there, and Puskás and Di Stéfano in this final.

Puskás was notorious for his powerful shot, and he does seem to spend a fair amount of this match casually walloping the ball goalwards whenever it comes his way. Even in a match of many shots, his total of 11 is still five more than any other player on either side.

His four goals (including one penalty) should have earned him the match ball for keeps. But the persistence of Frankfurt captain Hans Weilbächer eventually wore him down.

Eintracht Frankfurt’s Attack Frankfurt started the match well and even took the lead, but Madrid’s greater talent eventually began to shine through. By half-time, it already seemed likely they would be the losing side. The attacking output provided by their two inside forwards was much more limited than that of their Madrid counterparts.

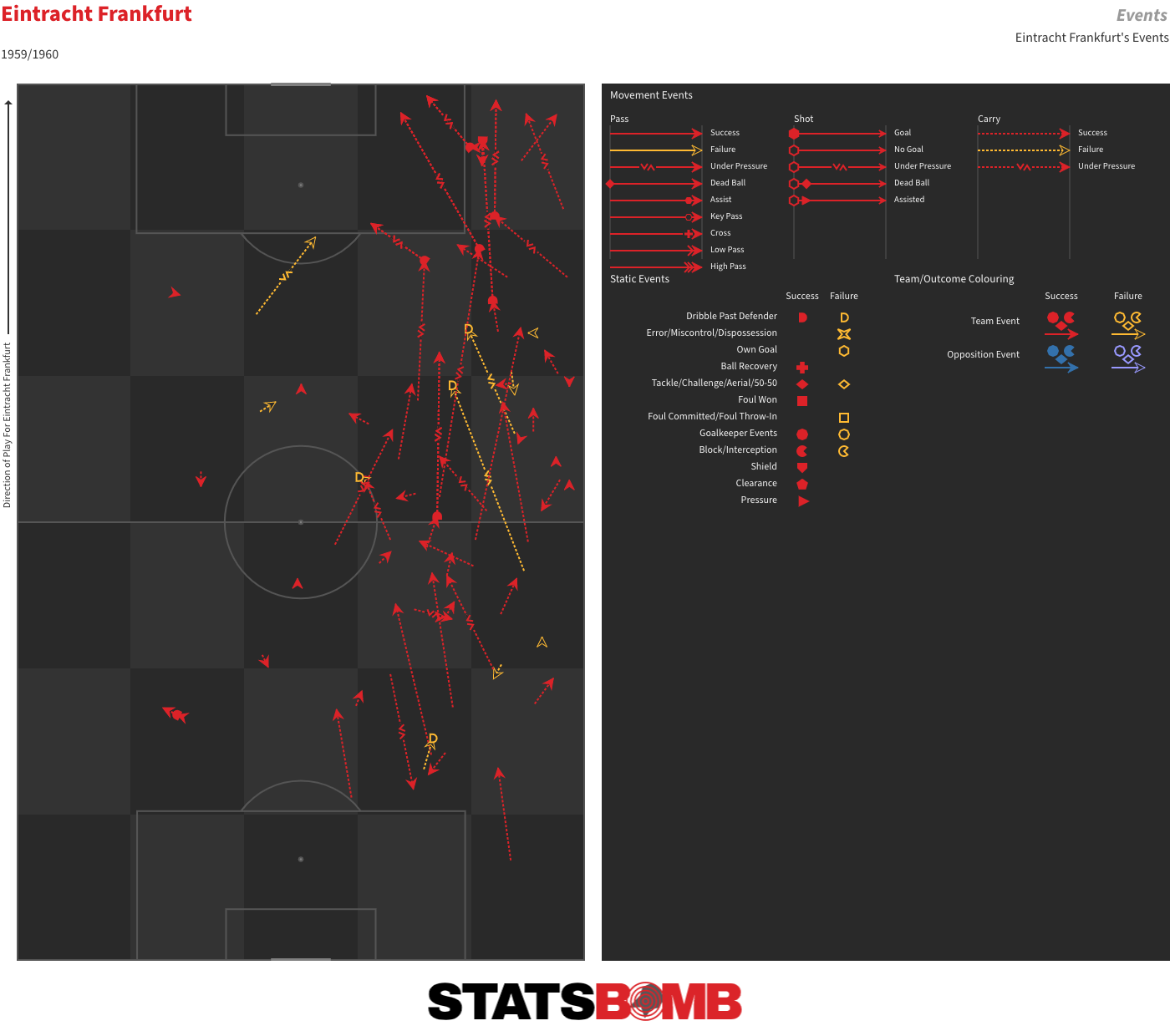

The threat Frankfurt did carry came from the two wingers and centre-forward Erwin Stein. Richard Kress was a regular menace down the right, receiving and driving forward at every opportunity.

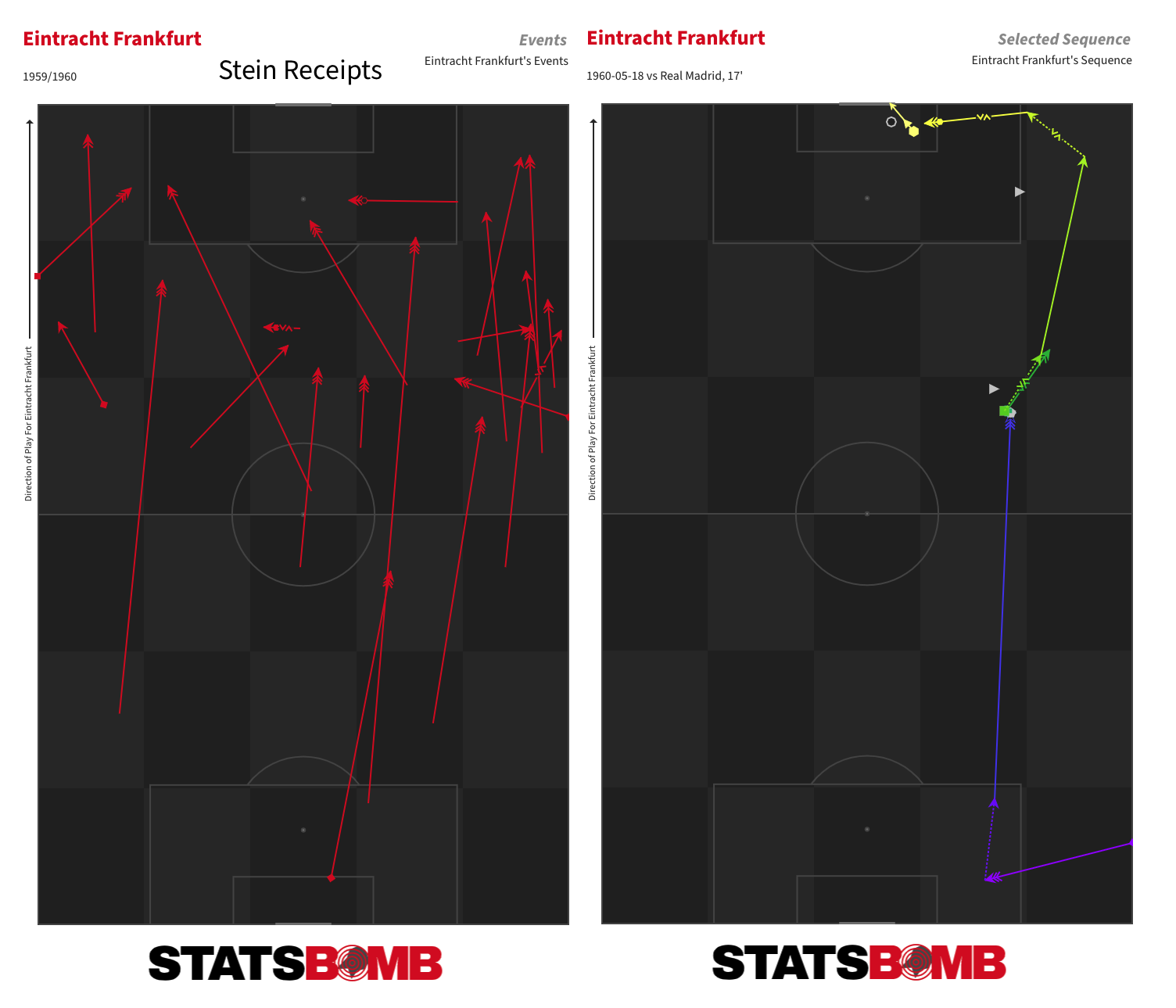

But it was Stein who caused most damage, scoring twice and assisting the other. In an era of man-marking schemes, it was interesting to note just how disruptive his peeled runs into the right channel proved for the Madrid defence. It was Frankfurt’s most reliable method for advancing into the final third and it yielded the opening goal of the match. He received a pass into that space from Dieter Lindner, drove on to the byline and crossed to the near post for Kress to finish.

Obstruction

To the modern eye, some of the fouls called in this match looked very soft indeed. The standard for what was considered an obstruction was obviously much lower at the time. Merely placing yourself somewhat across your opponent’s path was enough to be penalised. Madrid’s penalty is the very mildest of mild obstructions.

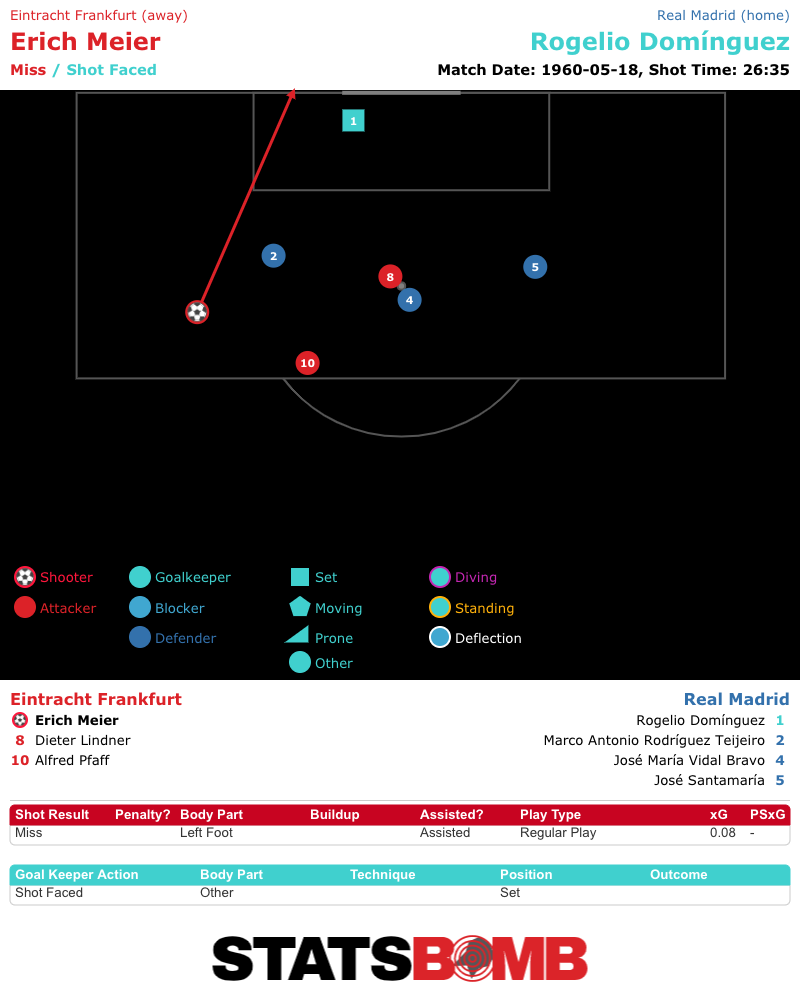

“He Should Have Scored” Watch

Our commentator, Kenneth Wolstenholme: “You can’t afford to miss chances like that and win the European Cup.”