Our history of the European Cup continues with the 1995 final between Ajax and AC Milan. We are only six years on from the match we covered last time out, but there have been some significant changes in the meantime. The offside law has been altered, the back-pass rule has been introduced and the European Cup has been rebranded as the Champions League.

This is the fourth entry in this series looking at a final from each decade of the European Cup. We’ve already covered:

- 1960: Real Madrid 7 - 3 Eintracht Frankfurt

- 1972: Ajax 2 - 0 Inter Milan

- 1989 - AC Milan 4 - 0 Steaua Bucharest

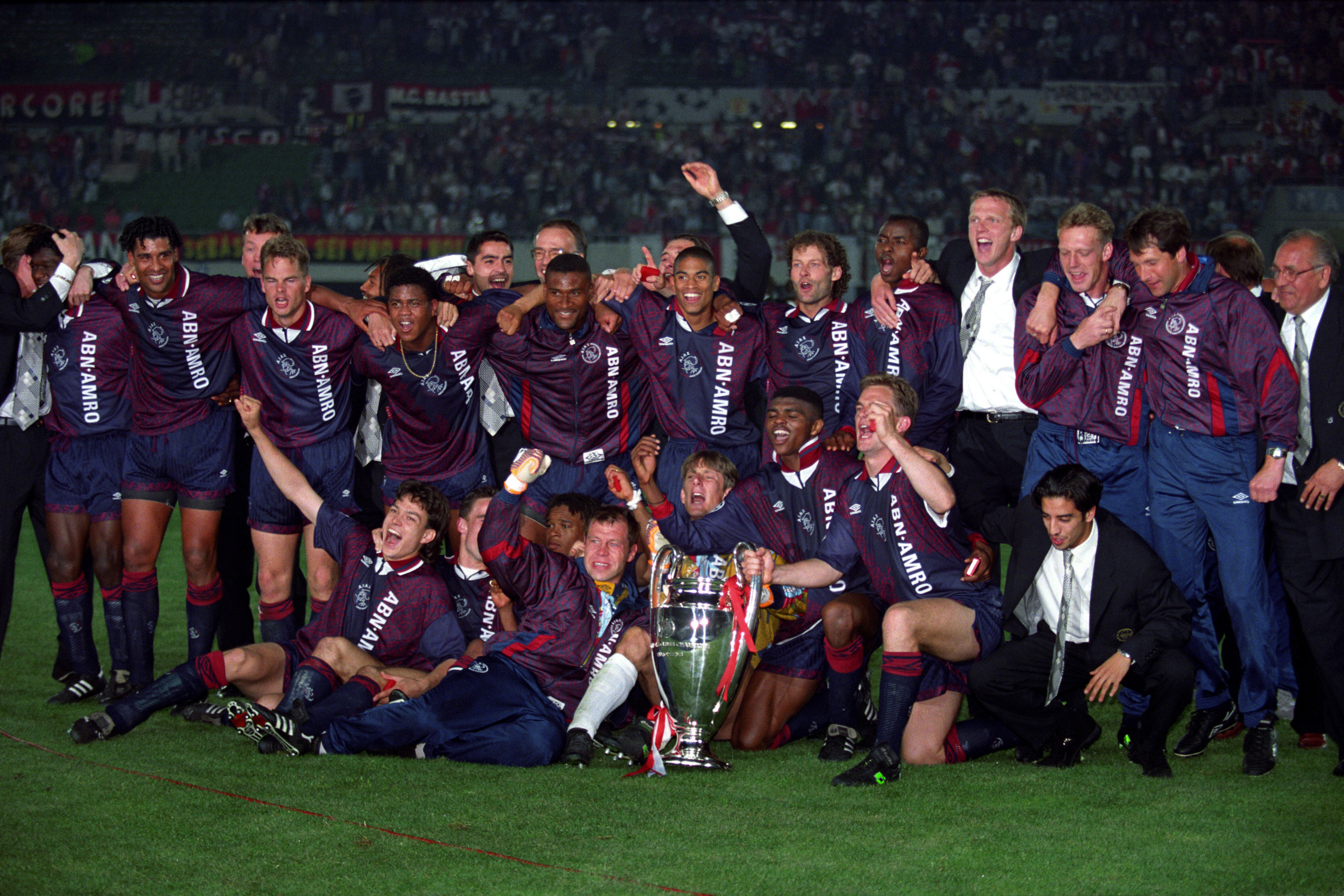

This time around we have a contest between Louis van Gaal’s young Ajax team and an AC Milan side appearing in their third consecutive final, and their fifth in a seven-year stretch beginning with their victory in 1989 that yielded three triumphs. They were already well-acquainted, having met twice during the group stage, with Ajax victorious on both occasions.

Differing Styles, Similar Results

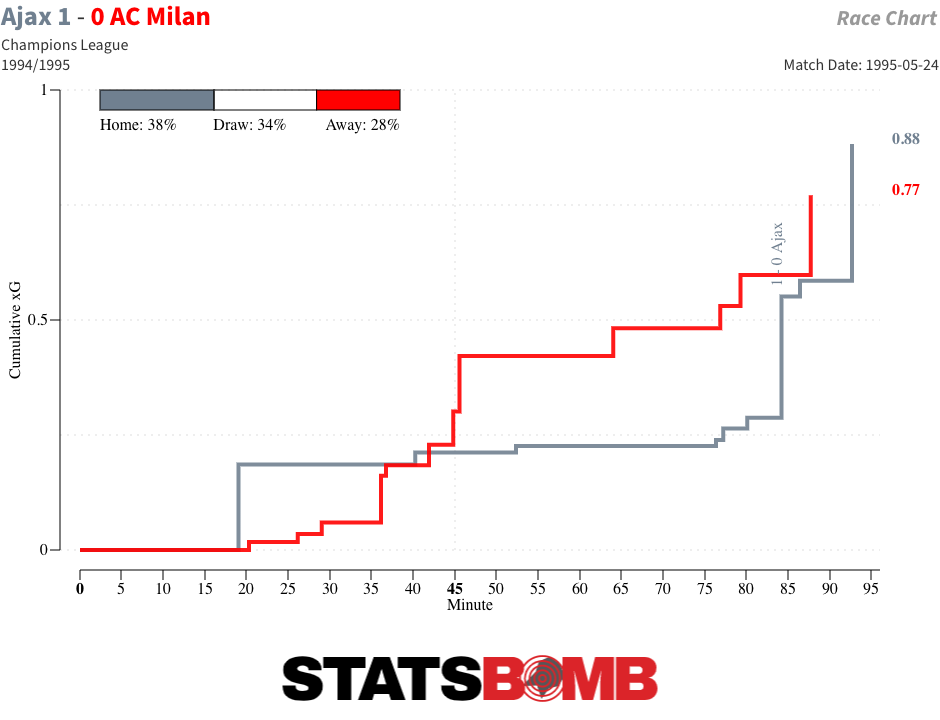

The last two finals we covered both featured winning teams who established territorial dominance with a high press. Both Ajax in 1972 and Milan in 1989 were able to pen their opponents in and seriously inhibit their ability to advance into dangerous positions. In contrast, this match was a much more even contest between differing yet equally valid approaches.

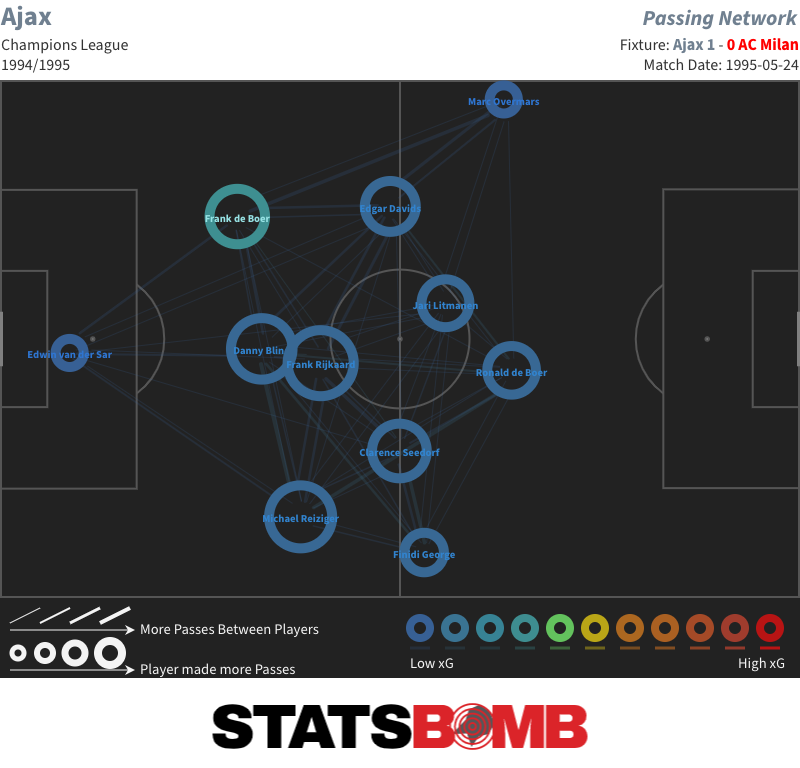

Ajax held the lion’s share of possession (61%) and sought to patiently construct play from the back with a ball progression scheme that was far more systemised than any we’ve seen in the previous finals in this series. Their 3-4-3 system with a diamond midfield provided a central column of reference points around whom the rest of the team could triangulate.

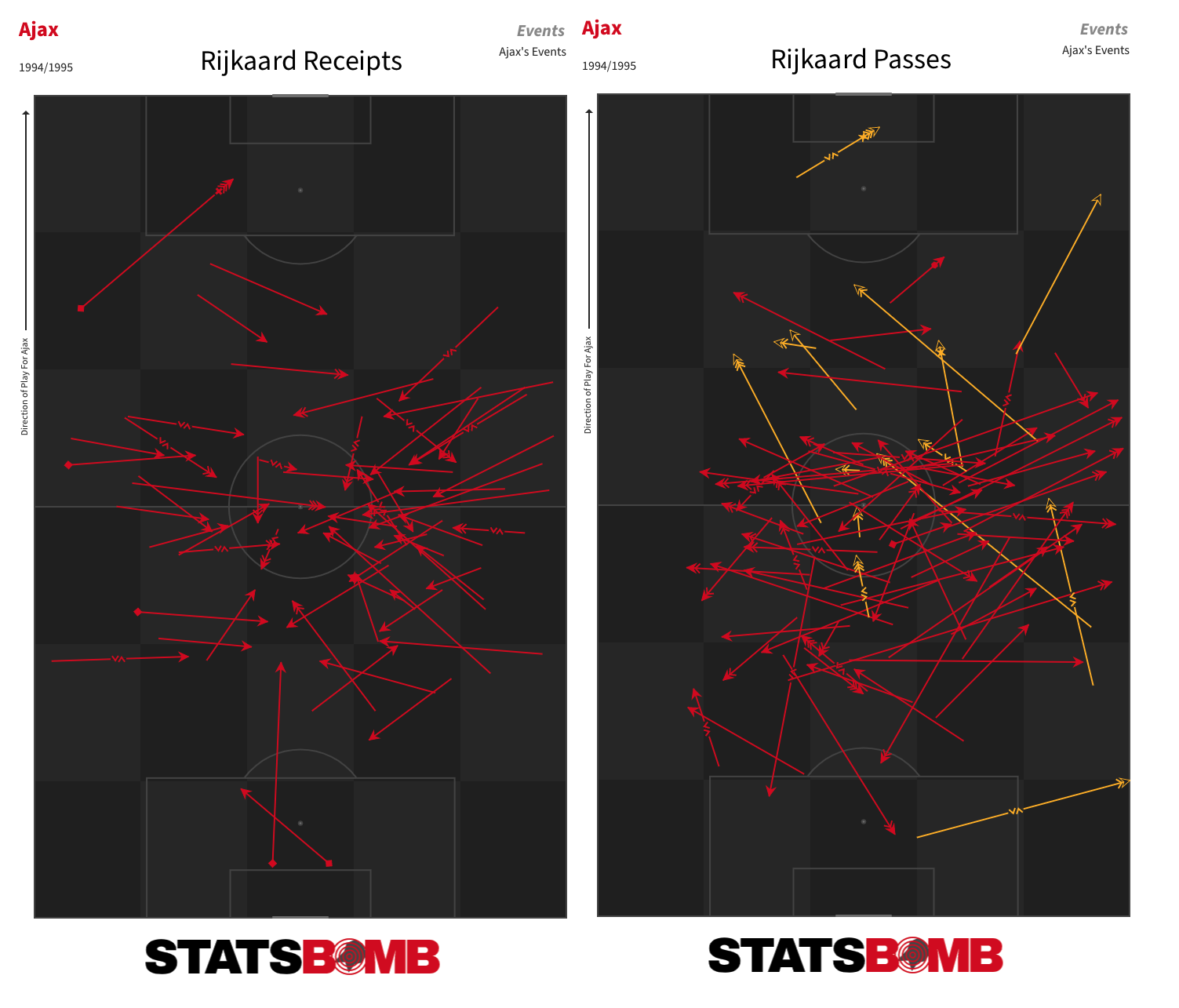

Danny Blind, Frank Rijkaard and (until he was moved back into midfield) Ronald de Boer frequently acted as pivots to change the angle of attack -- often with back-to-goal layoffs in the case of the latter-mentioned pair. Van Gaal’s side were highly methodical in working the ball from side-to-side in search of openings, and Rijkaard was the brains of the operation.

Blind and Rijkaard were the experienced figures in an otherwise young team. The remainder of the starting XI were all 25 or younger, while the two substitutes, Nwankwo Kanu and match-winner Patrick Kluivert, were both 18. Six of the starting XI, and seven of the 13 players used were academy graduates. This side provided the spine of the Netherlands teams who reached the semi-finals of both the 1998 World Cup and Euro 2000.

The degree to which Ajax’s ball use was structured was made clear by how quickly they paused counter-attacks to reset their positions once initial progress had been slowed.

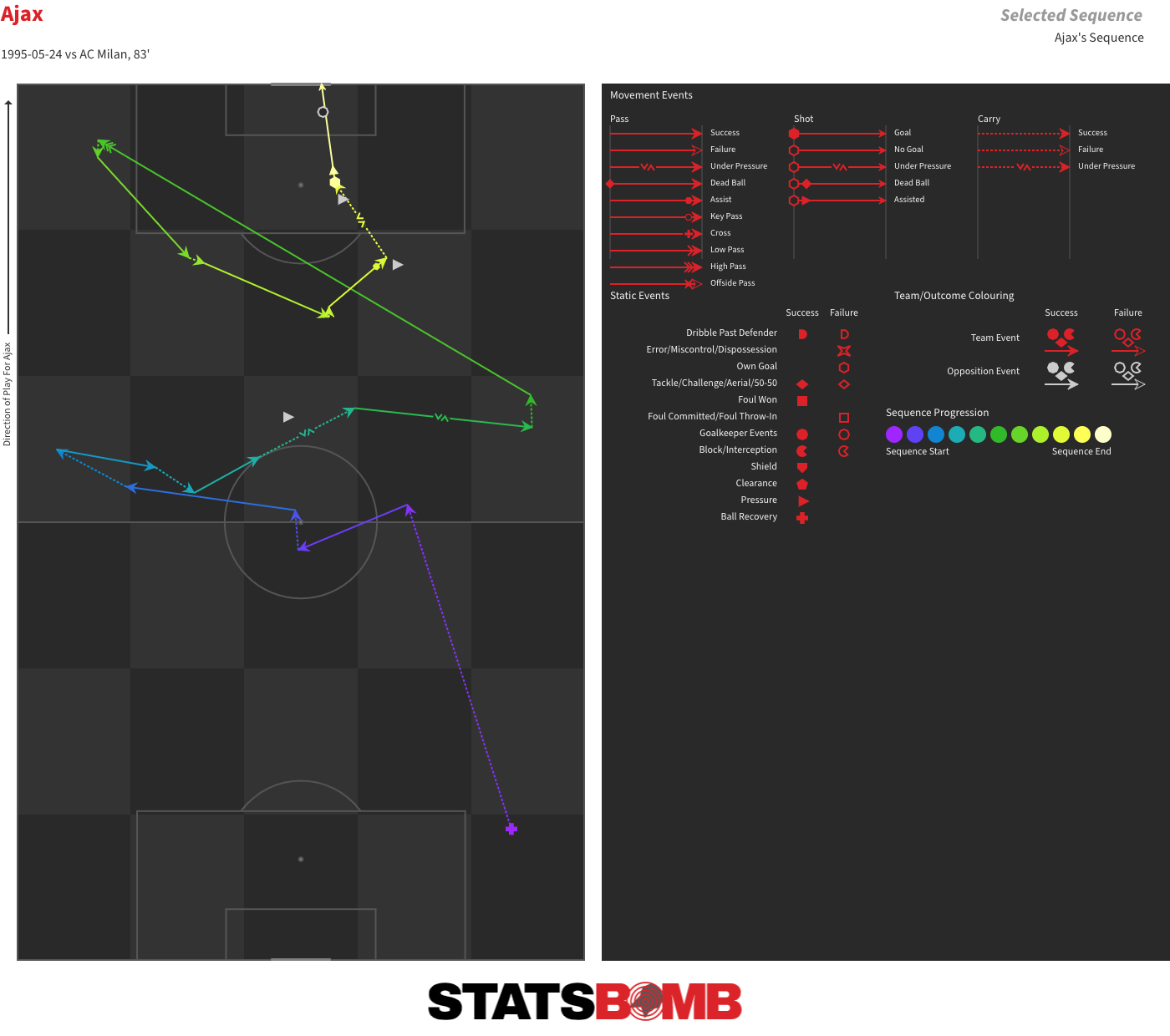

That was exactly what happened on their winning goal. Ronald de Boer burst forward out of defence into midfield, only to halt as options ahead of him narrowed. From there, the ball was worked out to the left, across to the right, back to left, and from there into the centre, where Rijkaard found Kluivert to prod home from inside the area.

This Ajax side utilised possession as a means of control. They denied it to the opposition, and moved the ball in such a way as to leave themselves adequately positioned to win it back once lost. It was almost more of a defensive tool than an attacking one. Ajax kept eight clean sheets across their 11 matches in the 1994-95 competition, including four in their five knockout round matches. It was the same story the following year, when they lost on penalties to Juventus in the final after recording eight clean sheets in 10 matches to get there.

To a degree, Milan were content to allow Ajax the ball and then drop off to form a solid defensive block. They didn’t regularly contest possession chains and leaned on their experienced and well-organised backline to defend their area. Alessandro Costacurta, Franco Baresi and Paulo Maldini were still in place from the 1989 final.

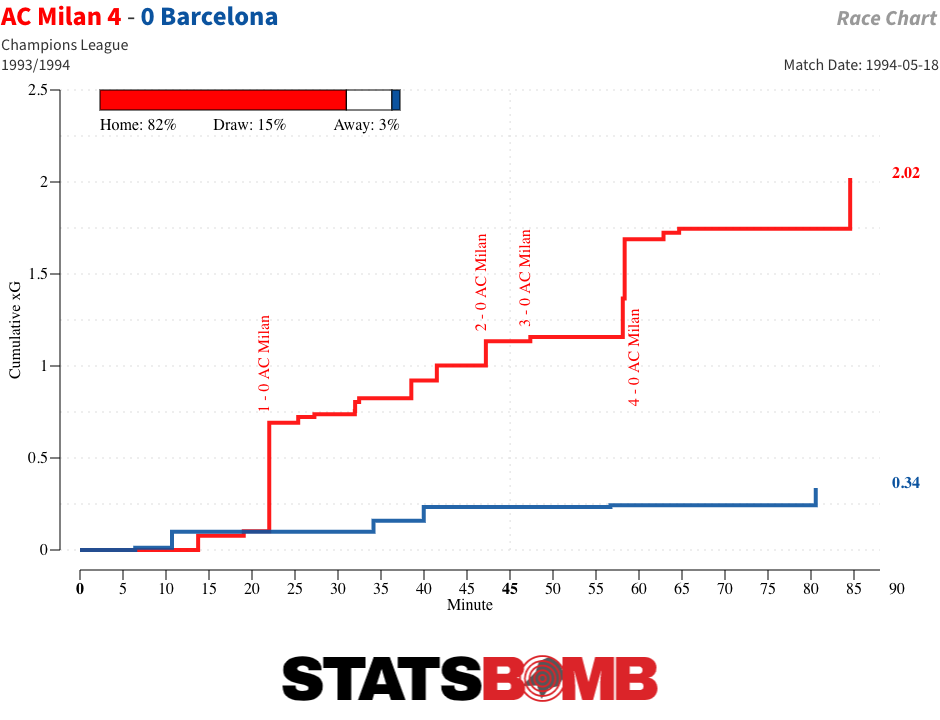

In total, they lined up together in four of the five finals Milan contested in this period. The only time they hadn’t was in the previous year’s final. With Costacurta and Baresi unavailable, Milan chose not to rely on defensive stability and instead took the game to Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona. The result was a convincing 4-0 victory.

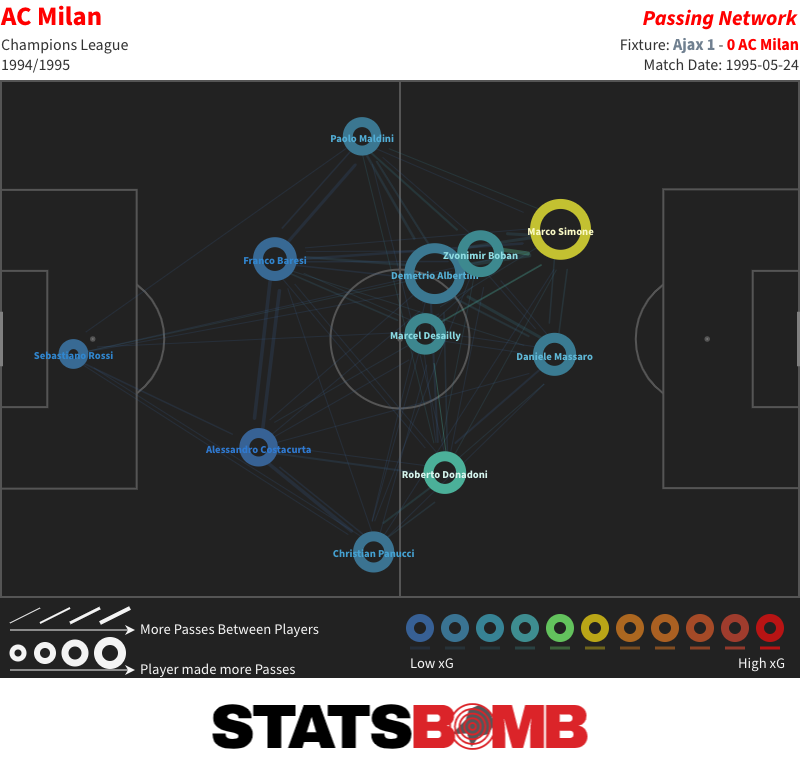

That didn’t seem to alter Fabio Capello’s underlying thinking. This late-era Milan side lacked the sheer offensive might of the earlier incarnations, and a cautious approach probably played better to their strengths. This was a much flatter 4-4-2 than the one we saw in the 1989 final, with only Zvonmir Boban’s movements infield from the left upsetting the symmetry.

Milan’s comfort in their game plan was illustrated by Capello’s level of inactivity on the sidelines. Van Gaal was by some distance the more animated of the two coaches, and there was a reminder that his dramatic reenactments of on-pitch incidents weren’t exclusive to his spell at Manchester United.

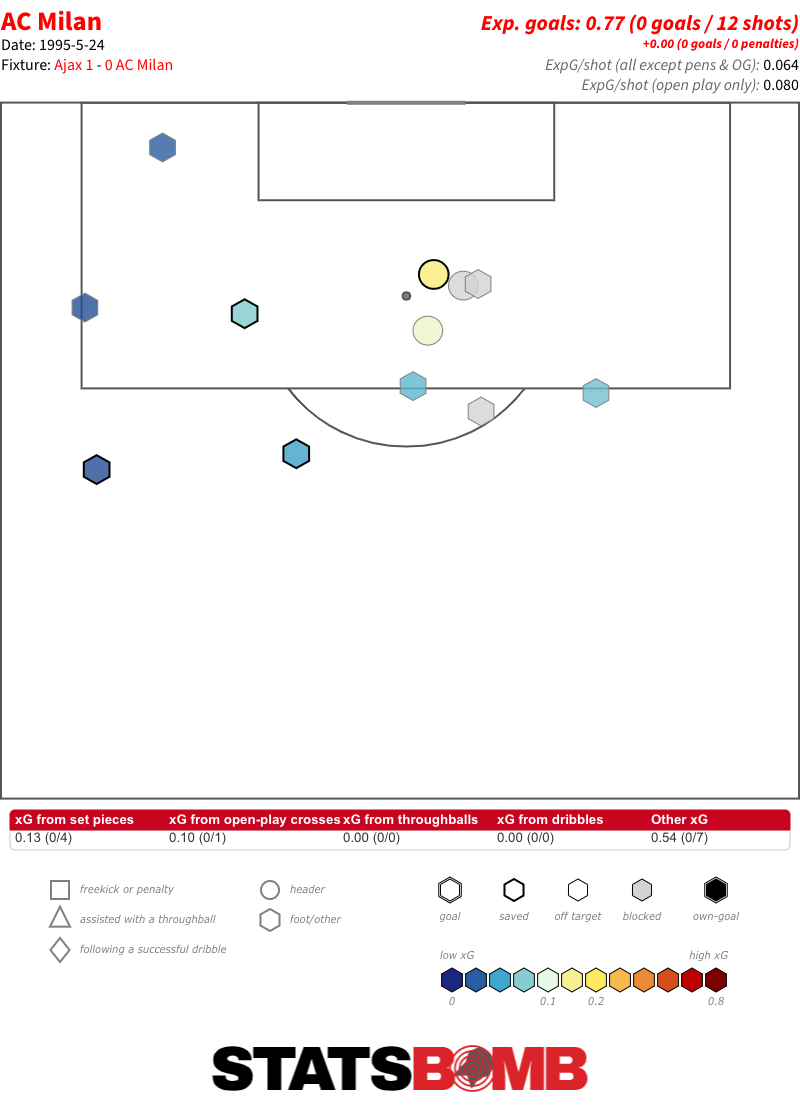

For much of the match, there was very little to separate the teams. Ajax moved the ball and moved the ball but struggled to penetrate. Marc Overmars completed just two of his 10 attempted dribbles from the left. Milan were much more direct in the way in which they moved forward, with longer balls through the centre and into the channels, but the majority of their efforts were just potshots.

Neither team created all that much. The final shot tally of 21 was a full 14 less than in any of the previous three finals in this series. The xG sum of 1.65 was also the lowest so far. Ajax generated the clearest opportunity and took the spoils, but it was a match that could easily have gone either way.

Edwin Van der Sar

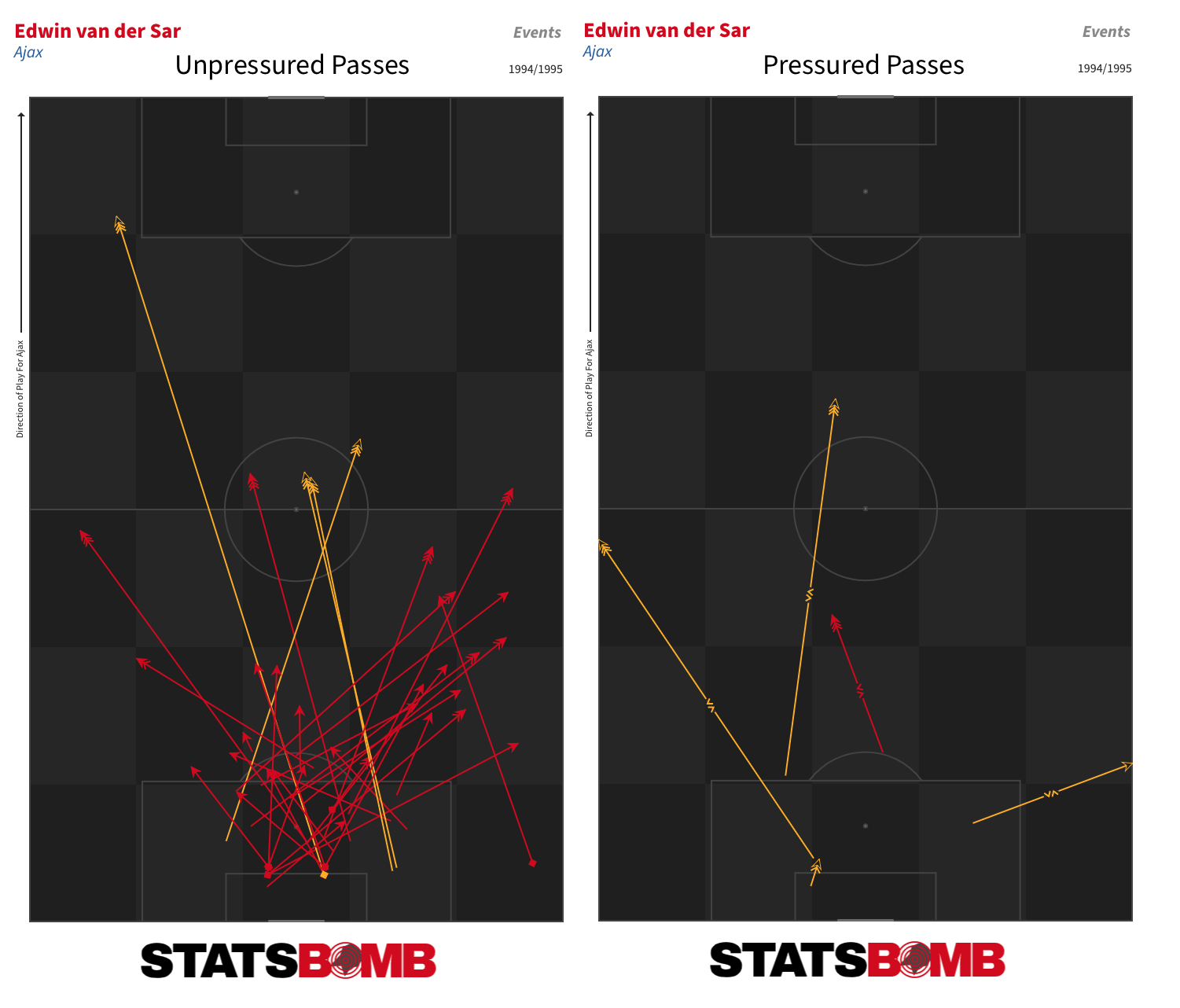

Edwin van der Sar was somewhat of an early template for the modern-day goalkeeper. He was certainly not the first custodian to show proficiency with the ball at his feet, but he was one of the most prominent examples of a goalkeeper with that skillset in the years directly following the outlawing of the back-pass in 1992.

That was evident here. He very rarely went long without reason, and while he wasn’t quite as slick in his execution as many of the goalkeepers of today, he was willing to take a touch to open up an angle for a pass or draw a degree of opposition pressure. There were a couple of awkward moments when he was directly pressed, but he otherwise used the ball in exactly the manner Ajax’s system required of him.

His completion rate of 79% was comparable to those of Alisson or Manuel Neuer in last season’s competition, but was also achieved with a longer average pass length. It’s worth noting, too, that a greater proportion of his passes were attempted under pressure. That completion rate dropped slightly over a larger sample size for the Netherlands at Euro 96 but was still within the range of some of the modern game’s most competent distributors.

Van der Sar was not the most aesthetically pleasing goalkeeper, never quite seeming to be in complete control of his lanky frame. He had at least a couple of particularly flappy moments in this match. But he enjoyed plenty of success over the course of his career and was an early indication of the direction in which his profession was heading.

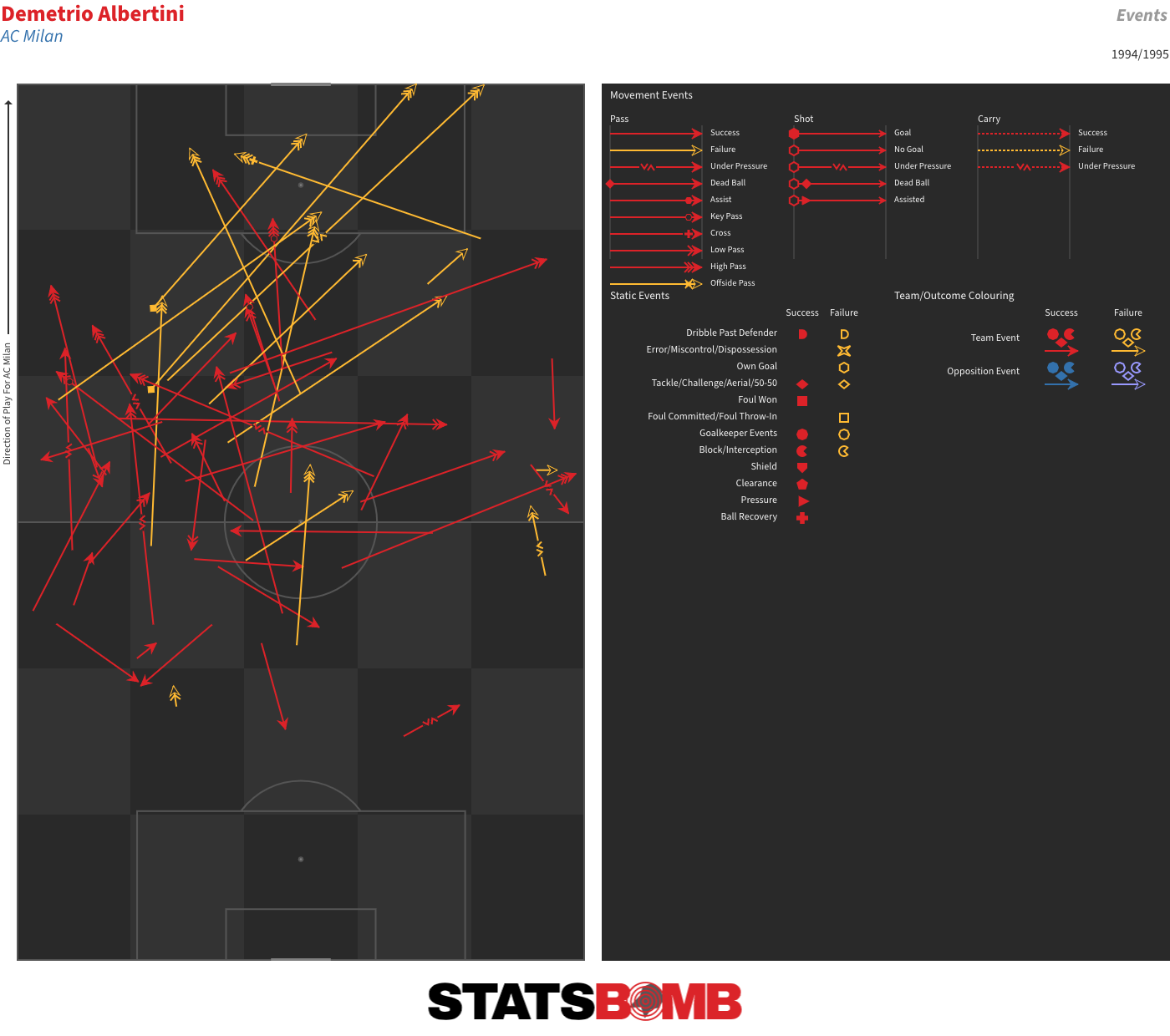

Demetrio Albertini

It is worth highlighting the importance of Demetrio Albertini to this Milan side. He was a consistently progressive passer in transition, the Milan player who most often moved the ball into the final third, and he also created more chances in open play (three) than any other player. His clipped pass into Daniele Massaro for one of the striker’s patented swivel shots just past the hour mark was particularly well-executed.

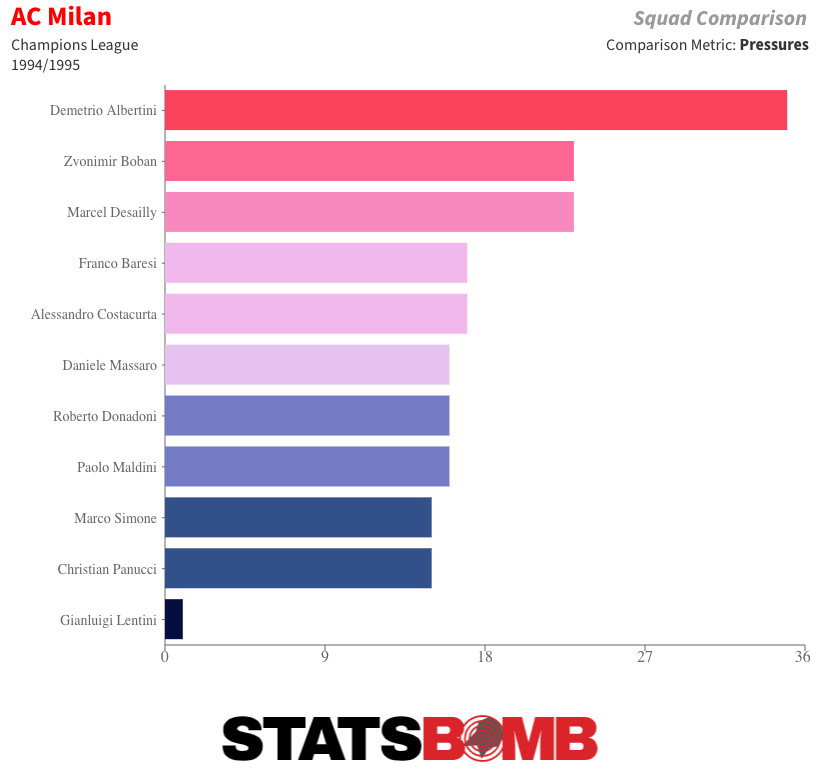

He also got through a ton of work off the ball, leading his team in interceptions, tackles and pressures.

Albertini had played alongside Rijkaard, his opposite number four, at Milan, and they would later join forces once more when Rijkaard, then head coach at Barcelona, signed him in 2005 to see out of the final few months of his career at the Camp Nou.