Bournemouth, I keep being told, are an exciting football team.

This seems to be a multipurpose euphemism, recognizing the club’s limited stature, mildly radical interest in scoring goals, and Eddie Howe’s distinction as the least-dour English manager. (Historically, this has not been a fiercely contested title.) All of those plaudits are deserved, but they add up to something less exciting than the idea of Bournemouth. All the moment-to-moment excitement the club has generated in four seasons of Premier League play has produced what might generously be termed radical stasis. Bournemouth is football’s Groundhog Day; no matter what it does, it keeps having the same season.

Mind you, there are worse fates.

At this time last year, James Yorke noted that Bournemouth’s time in the Premier League had been characterized by low transfer spending, more attacking play than you’d expect from a club of their stature, points collected in hot stretches that were consistently followed by long periods of ineffectiveness, and season totals narrowly clustered between 42 and 46 points.

One year later, all those characterizations hold true. Bournemouth spent little in 2018-19 and accrued the bulk of their 45 points in an early-season run that was followed by a remarkable period of futility. One could therefore argue that Bournemouth had a typically Bournemouth season. There’s just one catch: Eddie Howe’s team produced this familiar outcome in a wholly new way.

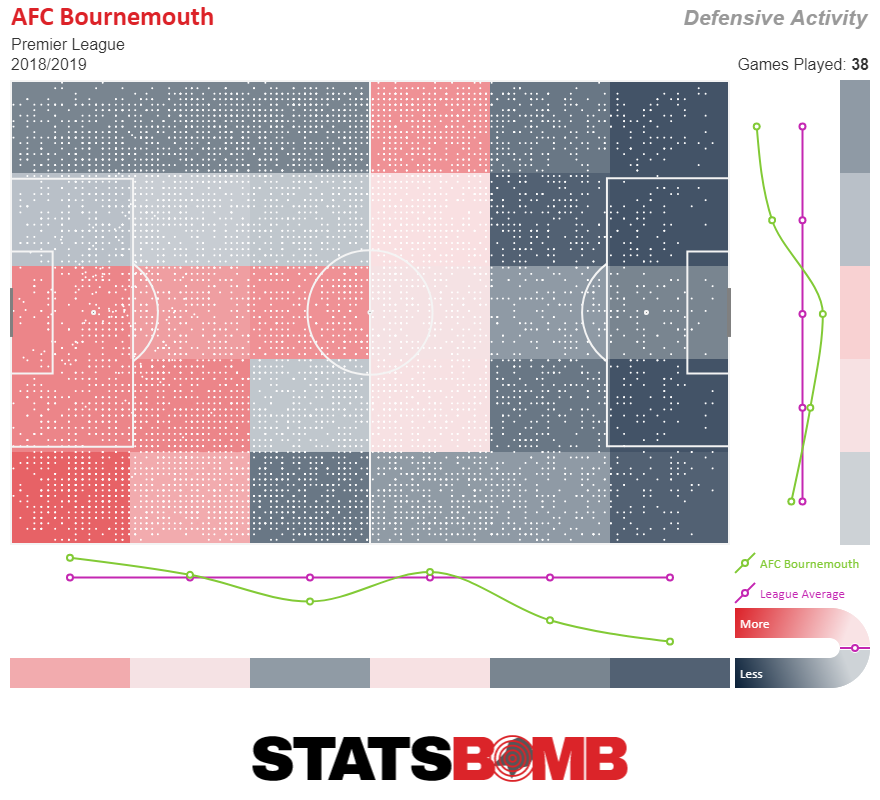

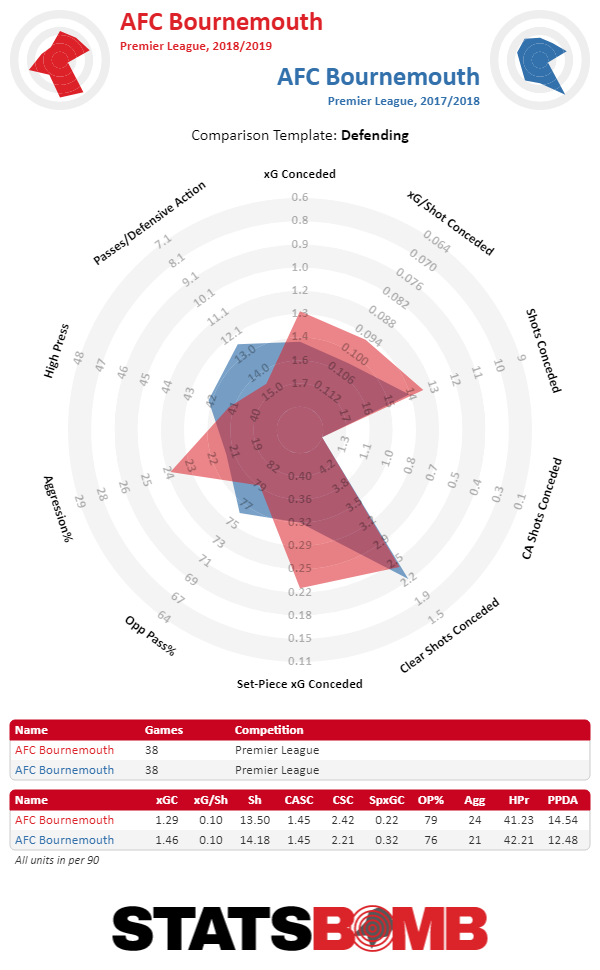

Bournemouth’s tactical and personnel changes in 2018-19 are best understood as attempts to solve the longstanding problem of opponents regularly waltzing into their penalty box. Howe switched from a 4-3-3 to a 4-4-2 and dialed back his team’s pressing to leave two midfielders stationed in the problem area in front of the penalty box. This shift left playmaker Lewis Cook without a clear place in the team, but his absence was smoothed over by the arrival of David Brooks, a right-winger with central pretensions. These changes saw Bournemouth go from a team that did little defending in front of its box to one with above-average defensive activity in most of that area:

This wasn’t defensive activity for defensive activity’s sake: Bournemouth conceded fewer shots in 2018-19 and those shots they allowed were of a lower quality than in the previous season.

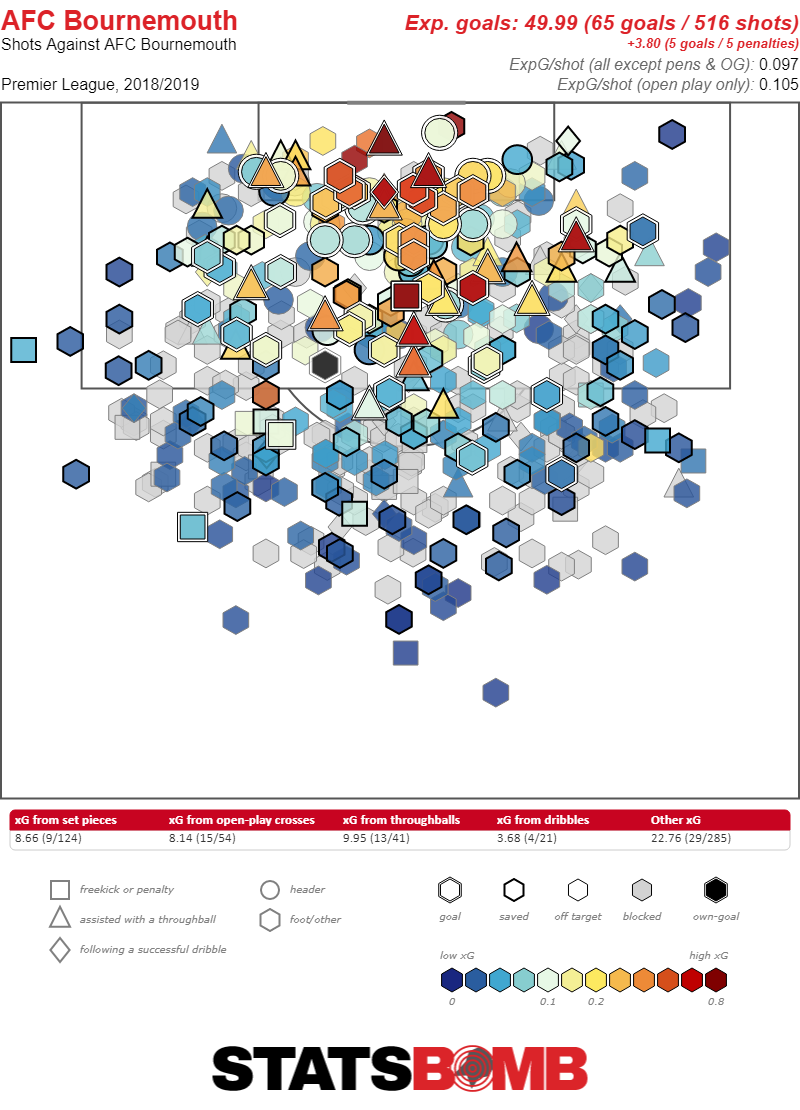

Those changes, combined with Callum Wilson being a very good striker and Ryan Fraser doing a ton of creative work, made Bournemouth an attractive proposition — at least in a spreadsheet. They were 8th in terms of expected goals created (1.24 per 90 minutes) and tied for 13th in expected goals conceded (1.29 per 90). With the league’s 11th best expected goal difference, Bournemouth had the statistical profile of a mid-table team. There was just one problem:

Conceding fewer and lower quality shots only matters if you can keep those shots out. Bournemouth, to put it delicately, did not. Only two teams conceded more goals than the Cherries last season, and they were both relegated with extreme prejudice.

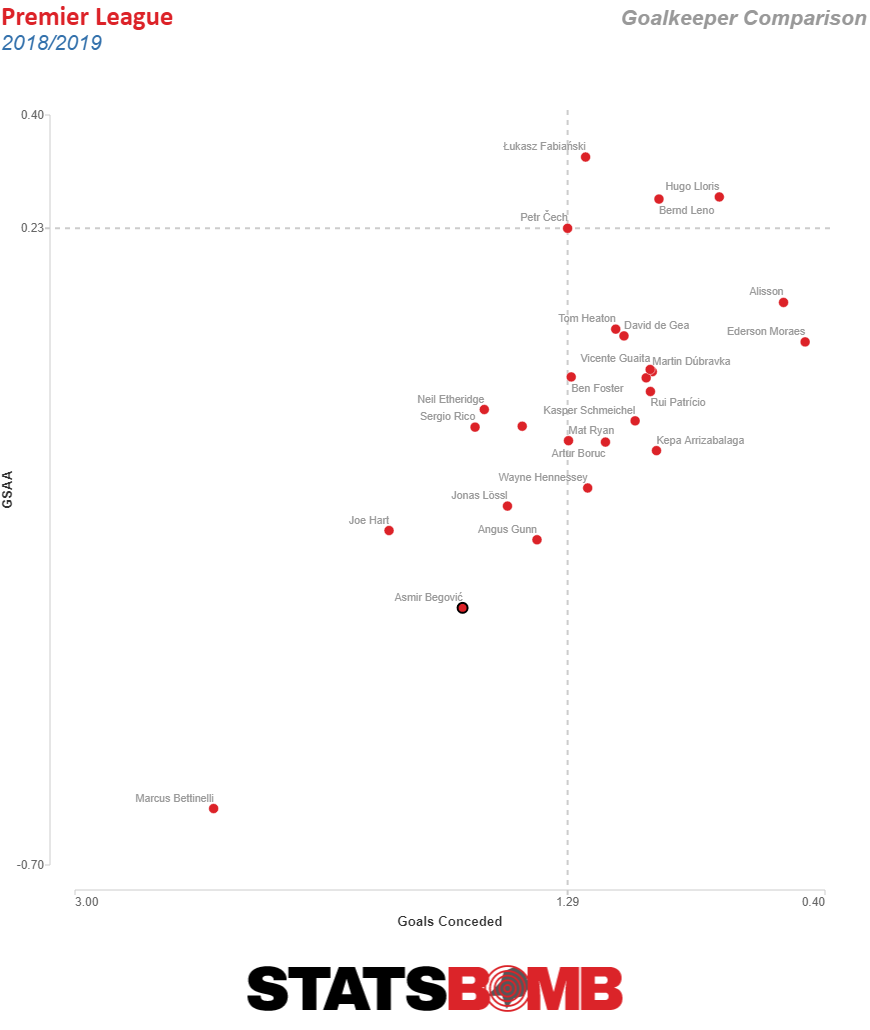

Whenever a team so egregiously underperforms its statistics, one can safely assume that many things went wrong. There were probably some injuries. Luck clearly wasn’t on their side. Still,

Asmir Begovic, who started the majority of Bournemouth’s game’s last season, was a disaster. Only Marcus Bettinelli was a worse goalkeeper on a per-90 basis, but at least Fulham — Fulham!!! — had the good sense not to start him as often as Bournemouth started Begovic, who put up the worst season totals of any keeper. Even Joe Hart, whose benching fixed most of Burnley’s defensive woes, had a better season. Begovic conceded a whopping 8.4 more goals than expected. His backup, Artur Boruc, was also notably substandard.

Bournemouth, with a settled Jefferson Lerma and a healthy Lewis Cook in midfield, could be a league-average goalkeeper away from delivering on last season’s mid-table promise. The club has been linked with Jack Butland, but Howe is reportedly unwilling to meet Stoke’s transfer fee demands. (Butland was useful in Stoke’s 2017-18 Premier League campaign, but was slightly below average in the Championship last year.) Failing that, the club appears to be hoping that Bergovic and Boruc won’t be the league’s worst goalkeeping tandem in consecutive seasons.

It’s not like Bournemouth is that much more prolific with its outfield transfers. They’ve purchased young fullbacks Lloyd Kelly and Jack Stacey from Championship clubs and sold center back Tyrone Mings and forward Lys Mousset. Bournemouth is on track to make a profit this summer, but its squad remains worryingly thin. Retaining a striker of Wilson’s calibre is the club’s main transfer success in this window. While Bournemouth has limited means, Howe has also spent scarce resources erroneously (the ghost of Jermain Defoe is still under contract and back from his loan spell at Rangers) or failed to integrate the likes of Mousset or Dominic Solanke. His squad, which was improved by the signing of Brooks and Lerma last summer, is still never more than a couple injuries from catastrophe.

Injuries happen. Bournemouth’s strong start to the 2018-19 season coincided with a period of good health, and the omnishambles that followed was exacerbated by a series of key players going down. Lewis Cook and Simon Francis are unlikely to rupture their cruciate ligaments in consecutive seasons, but it’s foolish to expect that nothing else will go wrong. The drop-off from Bournemouth’s ten best outfield starters to their backups is significant and worrying.

When projecting Bournemouth’s 2019-20 season, the team’s inconsistent play represents the main interpretive challenge.

One can make a generous argument that the team’s streakiness last year was largely a function of its schedule; Bournemouth beat up on lesser teams early in the season and struggled against better competition. Injuries further accentuated this dynamic. Reshuffle the order of the matches, the argument goes, and you have a relatively normal profile for a 14th-placed team.

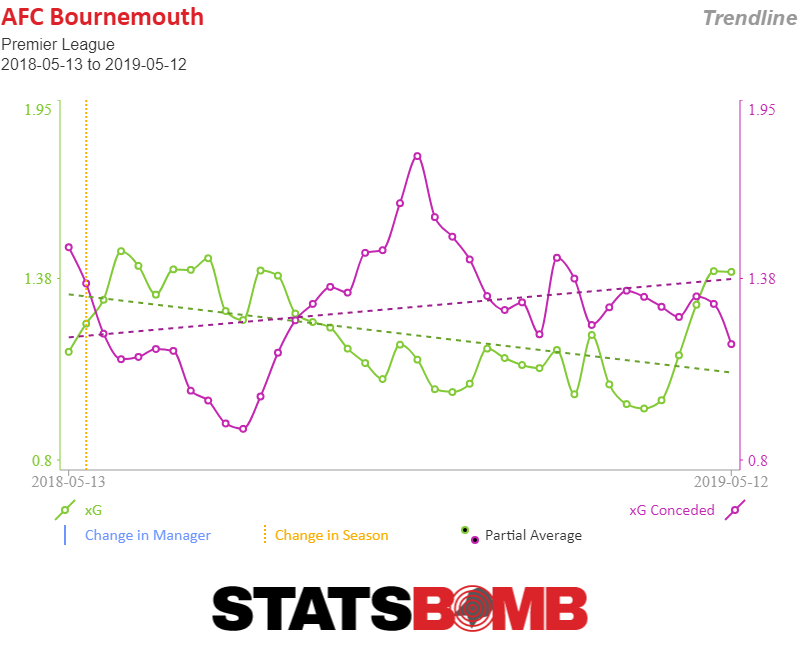

After four seasons of Premier League football, though, Bournemouth’s hot-and-cold nature seems like more of a feature than a bug. The team last won consecutive matches in January and was defeated by relegation-bound Fulham and Cardiff. This wasn’t solely a quirk of sequencing; Bournemouth got worse as the season went on. And even smoothing their stats into a ten game rolling average doesn't sugarcoat their inconsistency.

Much as Eddie Howe deserves credit for the big-picture shifts in Bournemouth’s tactics last season, his inability to solve problems during the season should be interrogated. (“All our goalkeepers are less effective than training pylons” is admittedly one of the harder problems to solve by tweaking tactics, but it’s not like Howe has done much in the transfer market to address this glaring weakness.) The situation is reminiscent of the late Arsene Wenger years at Arsenal, where the manager would stumble into a good tactical switch — using a defensive midfielder, trying a back three/five — and then not tweak it at all until the cycle restarted 18 months later. Howe could do worse than become late-period Wenger, but his upside, like Bournemouth’s, may not be as high as some optimists suggest.

Still, the cautious outlook for Bournemouth is not that grim. For the first time in its Premier League history, the club has done enough to suggest its defending won’t be atrocious. Moreover, the club barely flirted with relegation last season despite incompetent goalkeeping and mediocre injury luck. A healthy Bournemouth shouldn’t be tipped for relegation this year, but it’s unlikely to improve on last year’s potential of mid-table comfort — even with a good goalkeeper. Eddie Howe’s transfer record and historical inability to fix problems mid-season suggest another finish in the 14th-16th place range is likelier.

Bournemouth are likely to produce another Very Bournemouth season. The only question is how.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association