By far the most surprising element of the 2018 World Cup has been the inability of Germany to get out of what looked to be a fairly soft group. At least part of that perception is that any group that includes Germany looks hard for the opposition and soft for themselves. Much like Brazil, they are favoured for every tournament they feature in and simply never fail, with semi finals, finals and trophies the norm.

Until now.

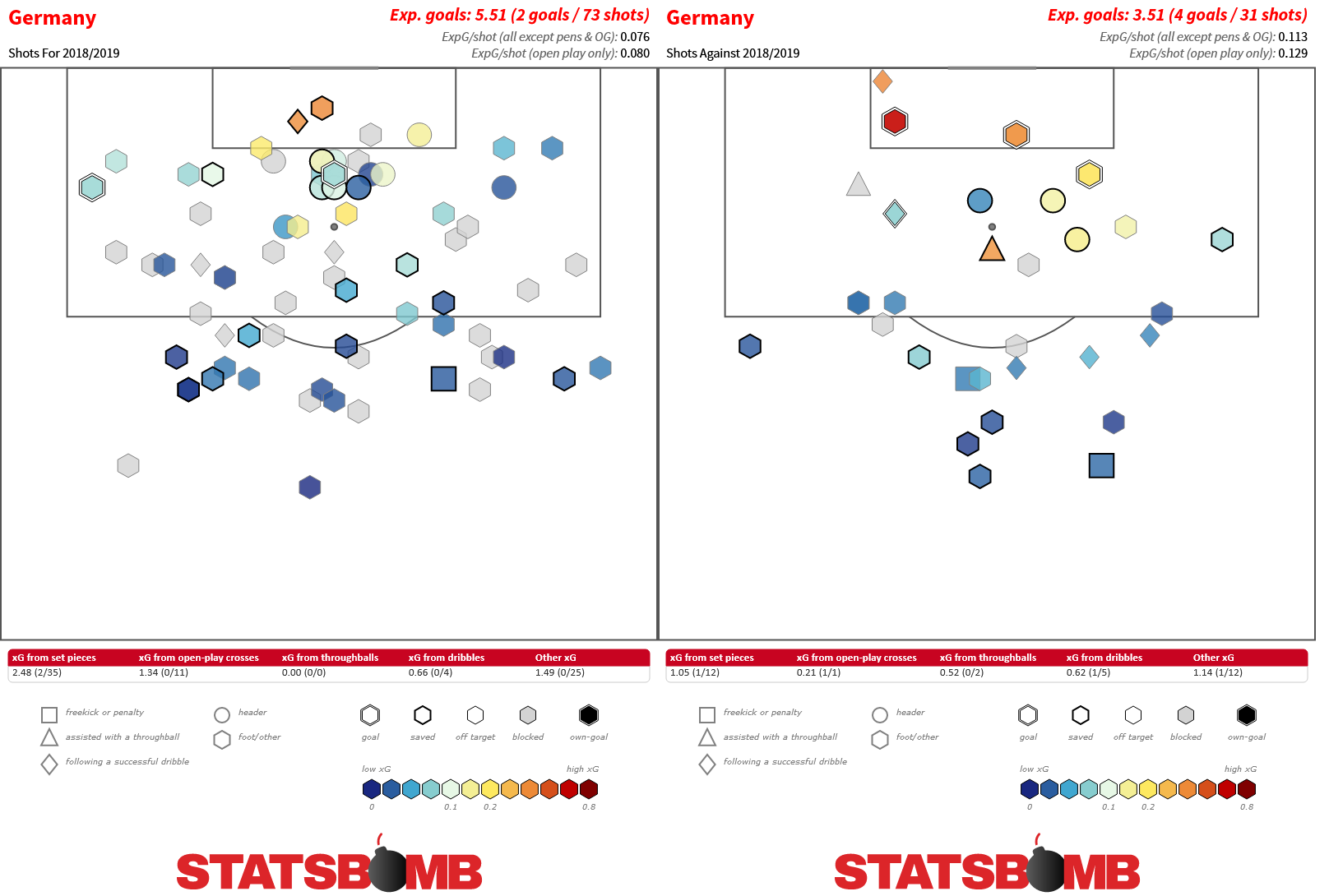

How they contrived to fail on the big stage remains a mild puzzle at least part of which can be attributed to the unfortunate ability of three games to fail to accurately represent team quality. Let's take a look at their shot maps:

The most obvious thing to note here is an expectation of 5.5 goals compared with a reality of just two. No team took as many shots as Germany in the group stage, but the actual quality of those chances was under par. An xG per shot of 0.08 in open play is distinctly below average (around 0.095) and below what you might expect from a decent side (the better Premier League sides were up towards 0.12 per shot this last season).

The obvious hook here from the South Korea game was the succession of missed chances from what looked like clear headers in the centre of the box. Mario Gomez, Mats Hummels, Leon Goretzka and Thomas Muller all got their heads to the ball in such positions and despite the best of those chances appearing to be gilt edged, they still spec out as relatively low conversion attempts, somewhere in the 0.15 to 0.20 range. The commentator may demand that they "must score" but probabilities disagree.

Given that the single best chance location that Germany carved out in this game involved Hummels wiggling past two defenders in the six yard box, it's hard to be super positive about their chance creation. A pre-tournament gripe, certainly from the Anglo-centric press and fanbase was the lack of Leroy Sané in the squad, and an inability to beat men wide via dribbling was a notable German absence. Mesut Özil, stationed centrally, completed five dribbles against South Korea and had a solid creative game--just without outcome-- but neither of Marco Reus or Leon Goretzka were able to stretch the opposition.

There is also an element of Germany's play that impacted at both ends: speed.

In attack, of Germany's 73 shots, only 16 of them emerged within ten seconds of them gaining possession: that 22% rate is the lowest of the any team in the competition. Germany got plenty of the ball, but they did not attack quickly. Part of this is a function of being a strong passing team trying to break down defensive units, but at no point did it appear that Germany had new ideas towards how to combat their lack of goals. The world waited for them to score, Germany lumbered on, apparently a blunt force and it never came to pass.

In contrast, as was starkly apparent in the Mexico and South Korea games, Germany were vulnerable to quick breaks. They left acres of space in midfield, particularly down their own right side where Joshua Kimmich was often stationed high up the pitch. The 44% of shots allowed that came within ten seconds of a new possession ranks as below average (12th worst) and supports what was only too apparent to a viewer's eyes.

The two South Korean goals skewed any broad numeric analysis of the shots allowed by the German defence, but overall, the goals allowed broadly matched expectation, and in terms of xG conceded, Germany were again firmly mid rank.

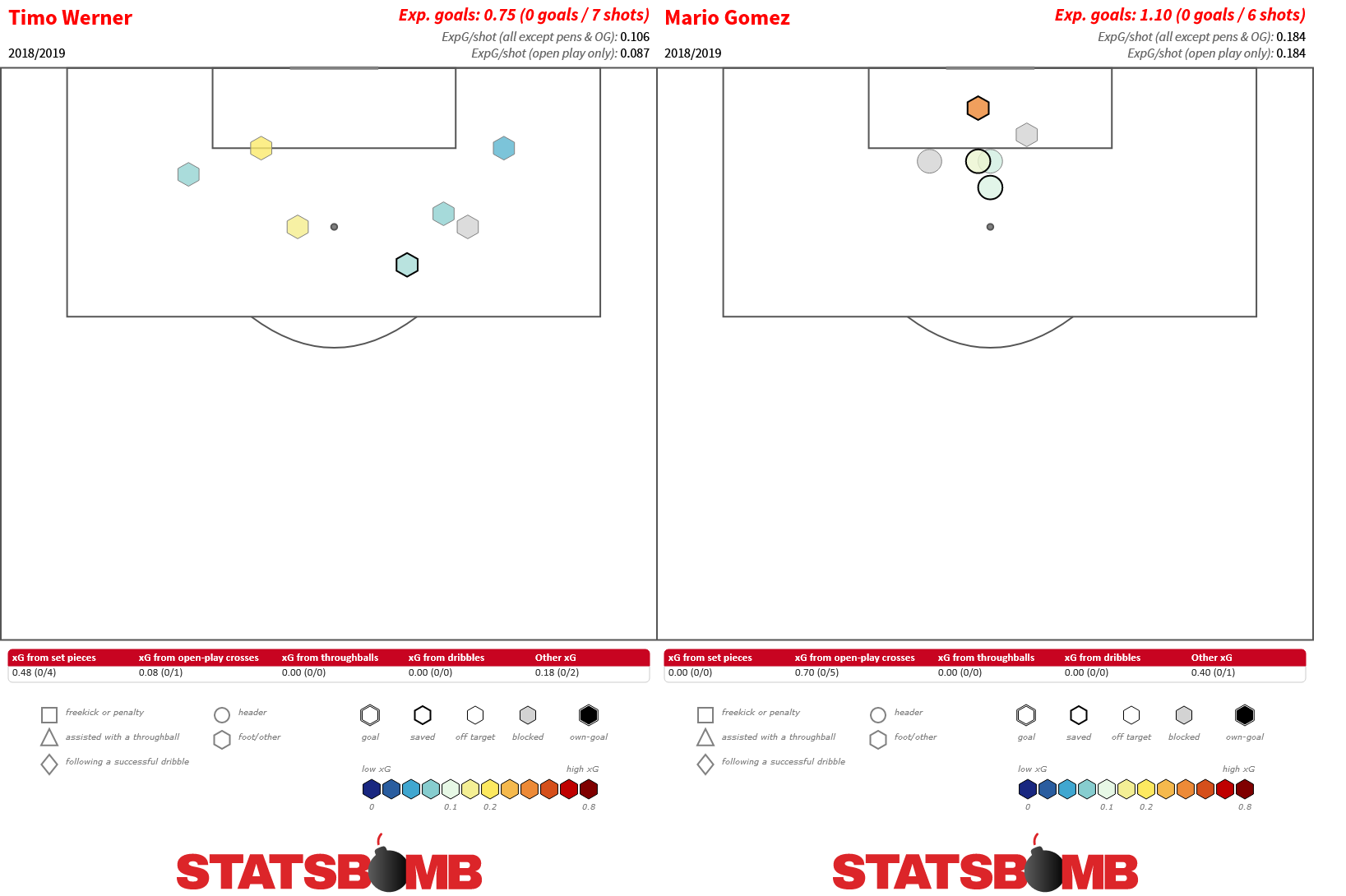

Sami Khedira and Thomas Müller had noticeably quiet tournaments but Timo Werner's contribution did not match that one might expect from the number one German striker pick. Compare his shots map from over 260 minutes to Mario Gomez's from around 80 minutes:

The bottom line remains that neither scored, but Werner clearly suffered in finding the space to get on the end of final balls. It all enters the melting pot of "reasons why" but if your main striker can't score or even get shots off at a rate commensurate to the dominance of the ball that Germany enjoyed, there is likely a link missing in the chain.

Failure has struck Germany square in the face and it feels like a typical lesson regarding squad transition. The core of this team have been together for eight years, and the virility of the 2010 World Cup debut has now given way to sterility as they age together. There has been talk of the German group using advanced machine learning in an attempt to leave no stone unturned, but this failure feels far more like a traditional football error. Revere your champions for too long and your team will not progress or transition. It takes some guts to cast out highly decorated legends, but as the repeated underperformance of recent World Cup winners shows, hard decisions may well be the ones that bear the greatest fruit.

For now, Germany will have to lick their wounds. Their national team structure and support group remains extremely solid and will regroup and rebuild. The message here is that the time to do that is now.

Thanks to Euan Dewar for additional data work here Header image courtesy of the Press Association