In terms of results, it’s hard to imagine England Under-21s having a worse tournament than what played out in Italy this summer at the European Championship.

Things started off reasonably well. England first played a France side stacked with top tier talents like Houssem Aouar and Moussa Dembélé. The Young Lions were able to play a mostly even game with the French for an hour, with a terrific individual goal from Phil Foden putting England ahead. An inexplicable moment of stupidity from Hamza Choudhury, however, put England down to ten men.

With the side not only a man down but playing without the squad’s sole defensive midfielder (in the kind of quirk that national teams often deal with, England’s talented young midfielders right now are overwhelmingly forward thinkers), England were totally unable to prevent France from generating attacks and deservedly conceded two late goals. The volume of good chances France created in the last half hour makes it hard to argue with the result, but there were genuine signs of encouragement when the contest was eleven against eleven.

There were fewer positive signs in the subsequent games. Choudhury’s suspension really hamstrung England, and an unbalanced midfield were never able to exert any control over matches. Granted, when you concede three goals from outside the box, as the Young Lions did against Romania, it’s hard not to feel like fate was working against you. But these were chaotic games where anything that could happen seemingly did. They spoke to England’s lack of disciplined midfielders, and arguably manager Aidy Boothroyd’s selection choices.

What they did not speak to, though, is the talent of the players. Of the 23-man squad, 14 have won a World Cup or European Championship at various youth levels with England. Among those without an international medal are Aaron Wan-Bissaka, recently bought by Manchester United for £50 million, and James Maddison, who would likely command an even higher fee if he made the same rumoured move. This is a promising group.

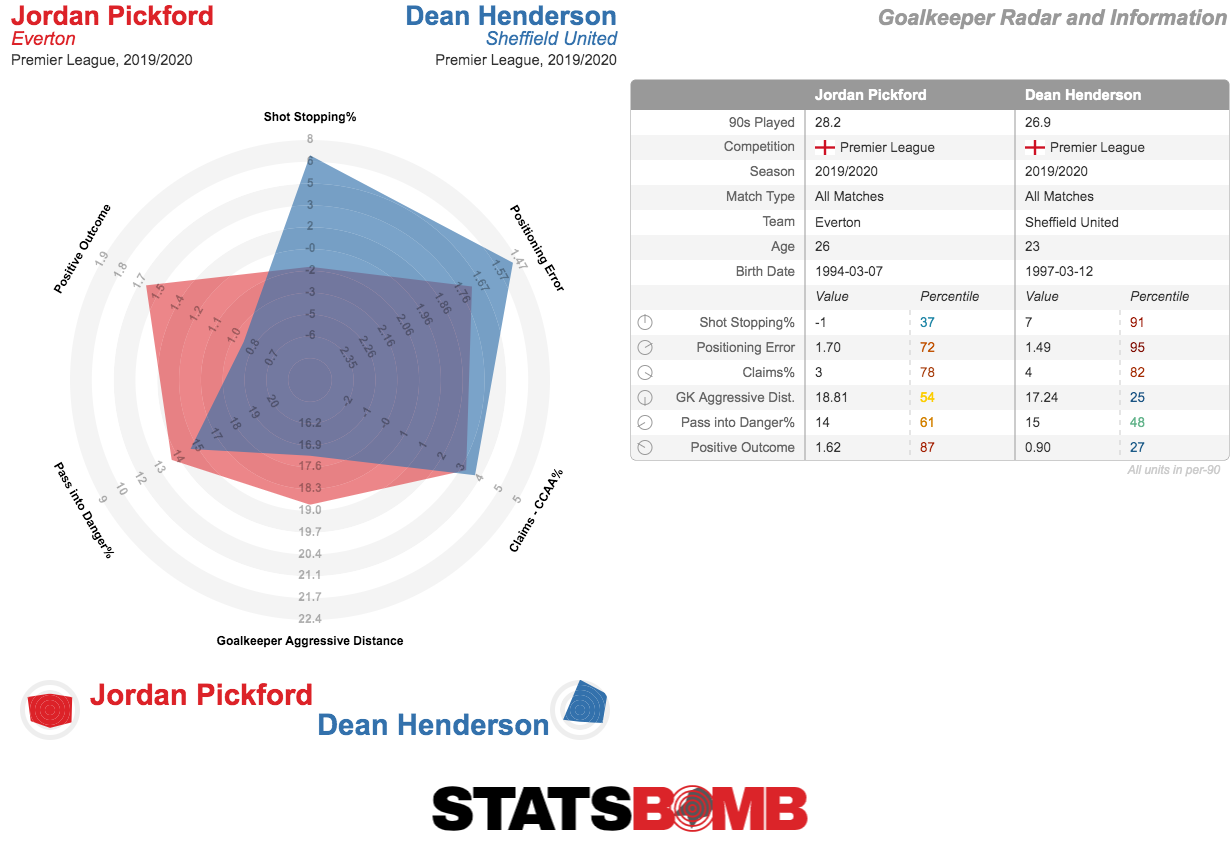

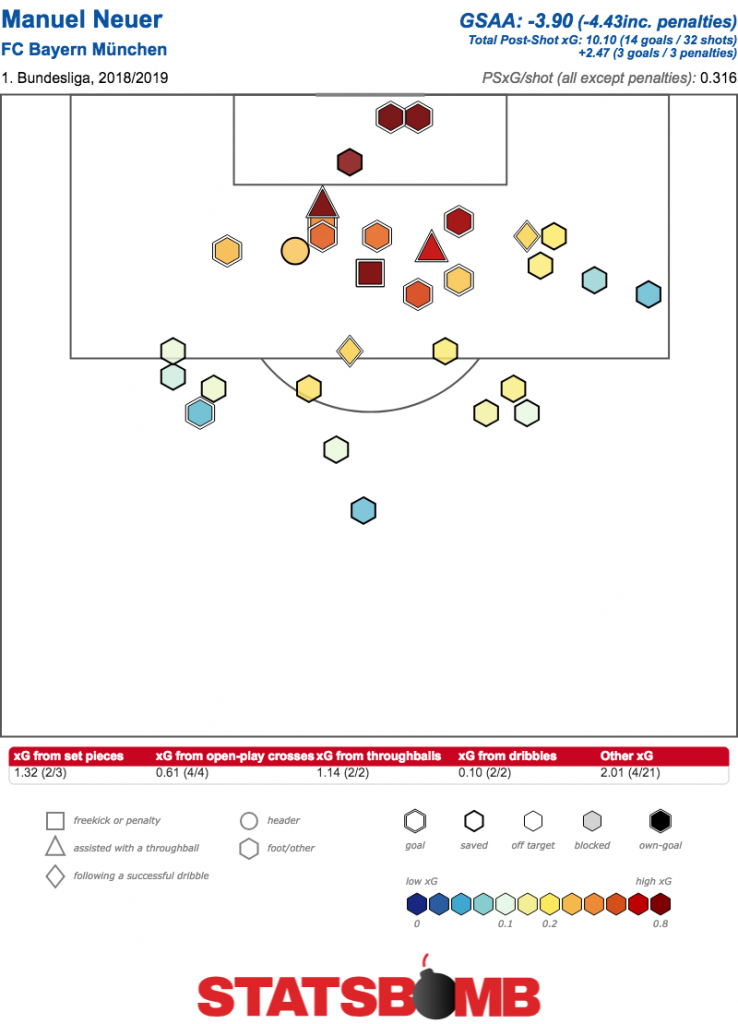

England senior side manager Gareth Southgate will surely want to see promote plenty of them in the coming years so let’s take a look at who might be progressing and how close they are to break through. (For purposes of this article, we have only looked at outfield players. Goalkeepers aren’t under as much of a time-crunch to develop, so let’s give Dean Henderson, Angus Gunn and Freddie Woodman a few more years before making serious judgements on them.)

Tier One: Ready Right Now

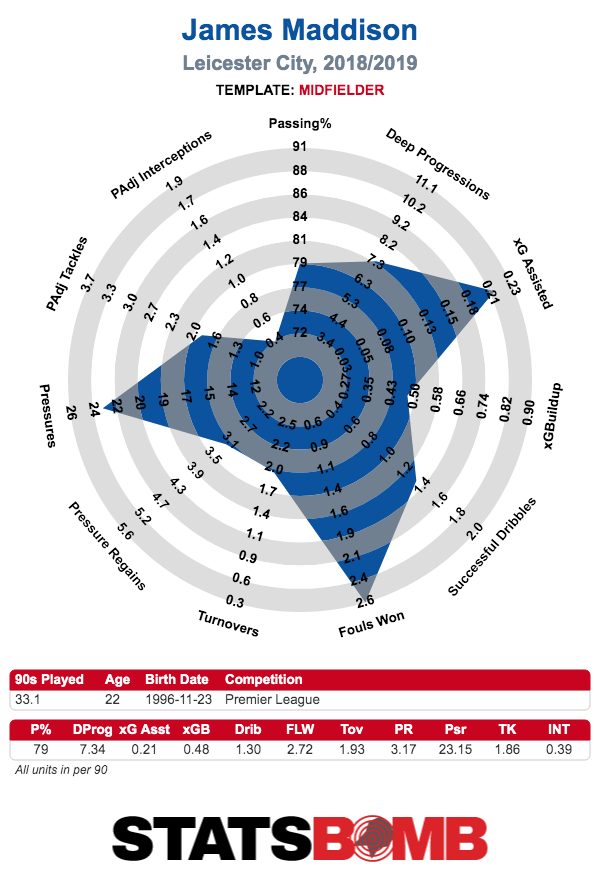

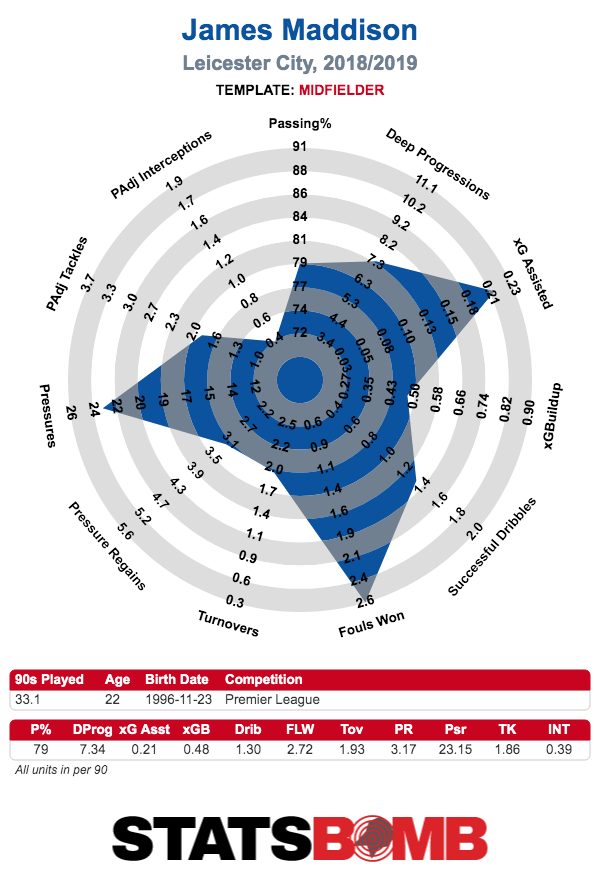

This is less a tier than a man. Mohamed Mohamed wrote about Maddison here at StatsBomb back in April, and it’s obvious that his qualities could translate to international football:

“[Maddison is] just constantly on his toes trying to get himself into open space for teammates to get him the ball. Whether it be moving a couple of yards diagonally to be between two opposition players, or making in-out cuts on the blindside of his marker to lose him, he’s got a lot of tricks in the bag… His positioning and ability to interpret space is arguably his greatest strength, constantly hunting for openings within the opposition. His ability to pass into tight windows in the middle third has been solid, along with his capacity to either be the initiator of combination plays or act as the link-man.”

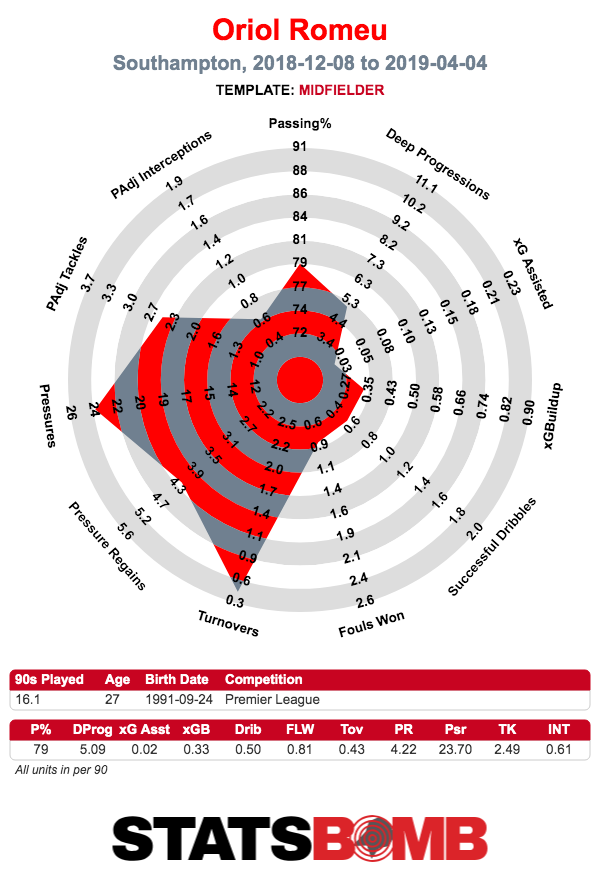

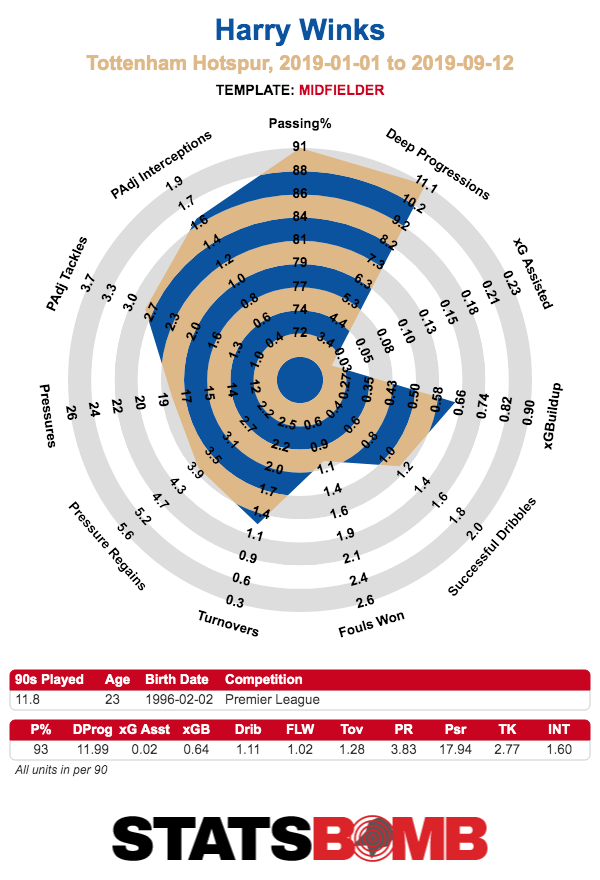

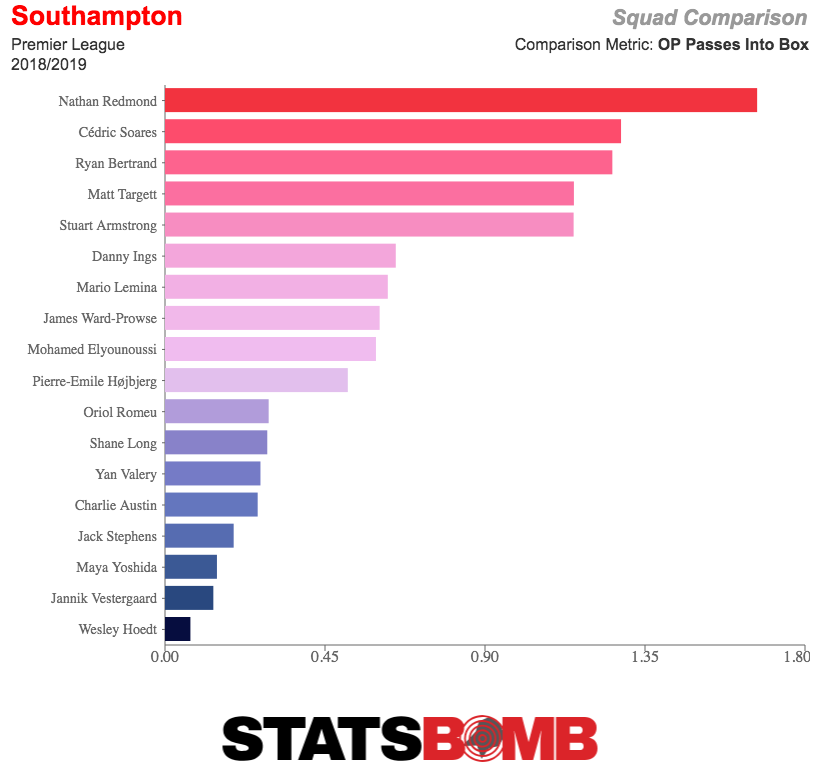

No English midfielder under 24 completed more open-play passes into the box per 90 in the Premier League last season, while only Harry Winks managed more deep progressions. There were concerns earlier in the season that the 4-3-3 system England are currently operating would not have space for a No.10 like Maddison. This has been somewhat alleviated since Rodgers’ arrival at Leicester has seen the 22-year-old move into more of a “free eight” role alongside Youri Tielemans, though one can wonder whether England’s midfield shape is too conservative for someone like him.

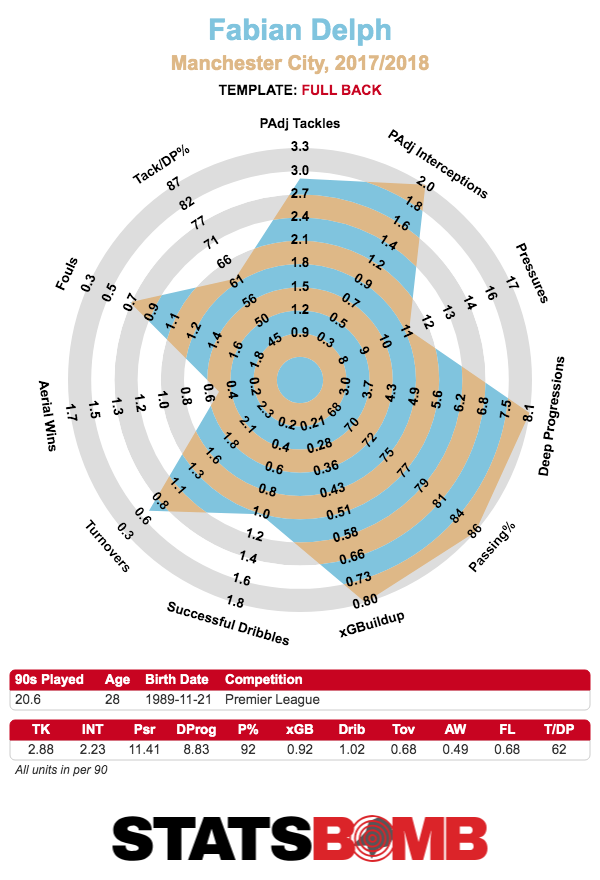

Nonetheless, he offers playmaking qualities sorely lacking in a team that recently started a midfield three of Declan Rice, Fabian Delph and Ross Barkley. He might not be a perfect fit, but he would certainly offer variety to England’s build-up play that has been lacking. Call him up in September, Gareth.

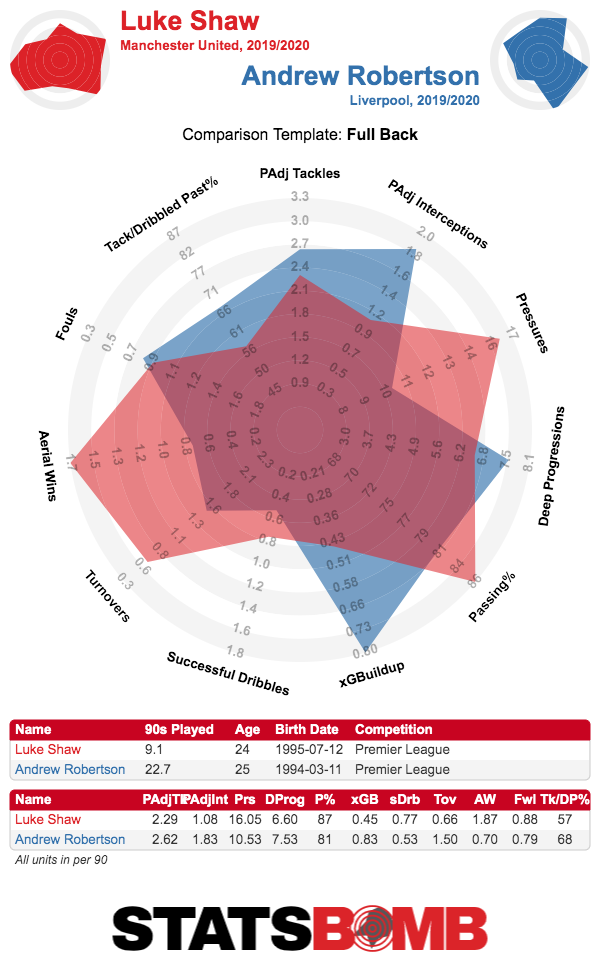

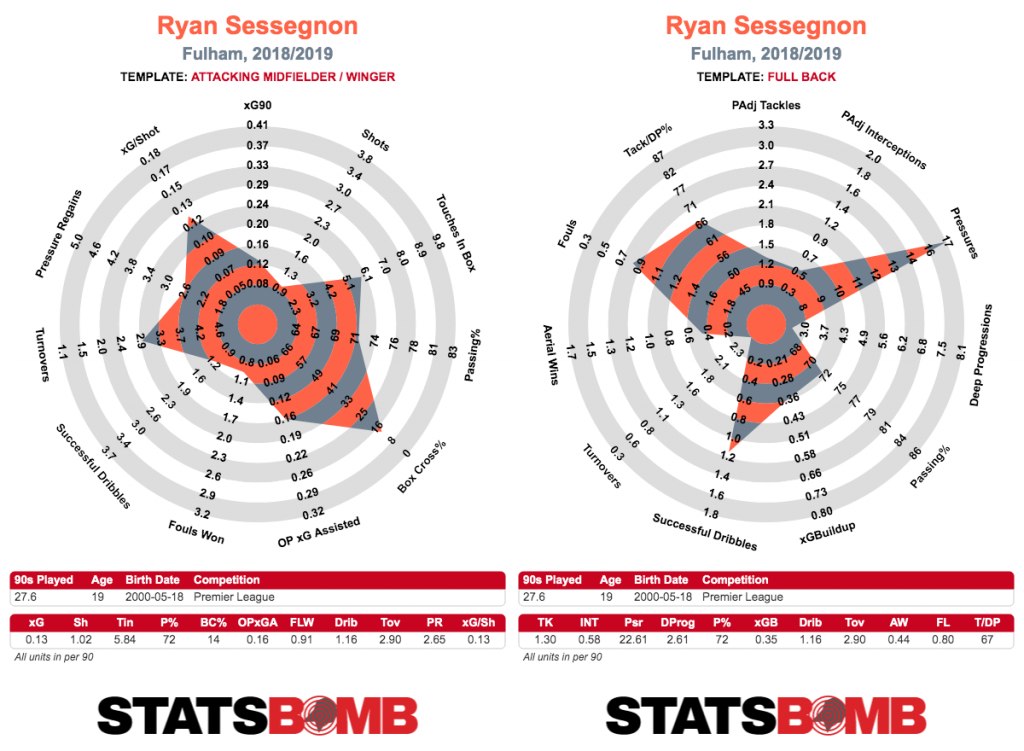

Tier Two: Options For Euro 2020, if They Have a Good Season

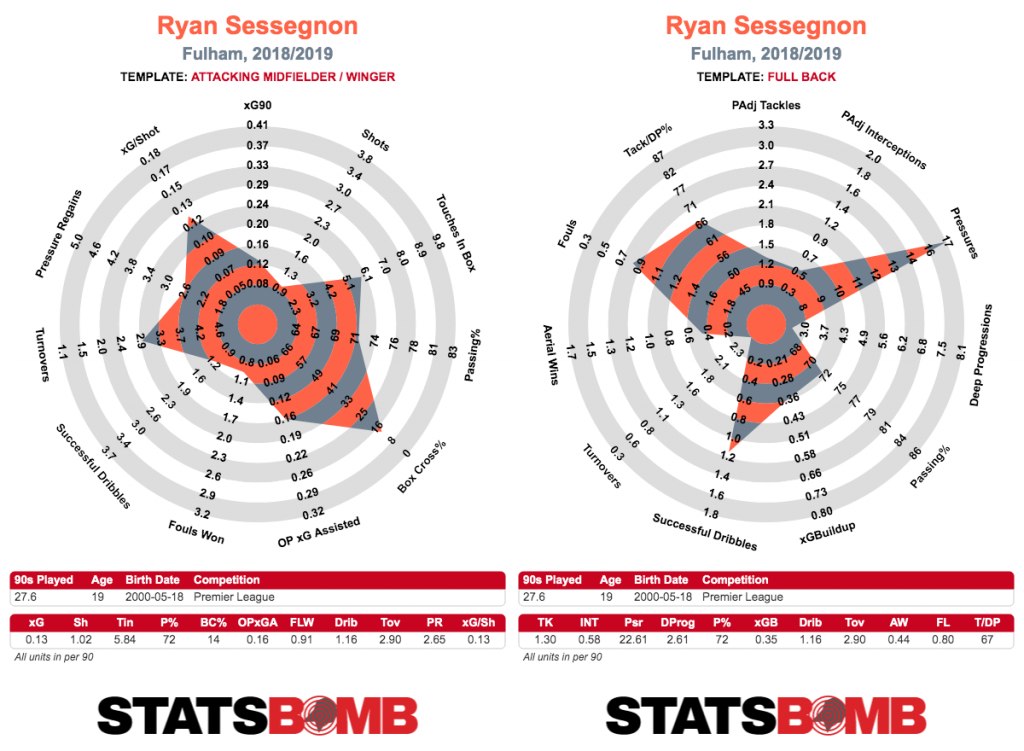

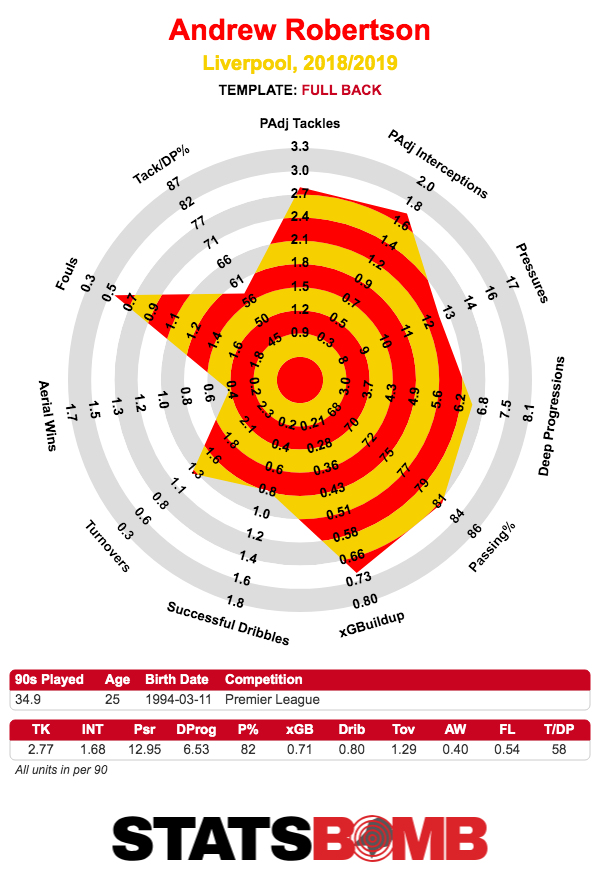

Ryan Sessegnon’s first season in the Premier League could not have been under worse circumstances. In one campaign, Fulham went through three different managers, all with their own ideas about how to use Sessegnon, and all unable to build anything like a coherent side. It’s hard to fault Sessegnon for not setting the world alight in such an environment, and it’s not obvious that this should be a permanent black mark against him. Even through all this, he put up a better open-play expected goals assisted per 90 than any young English player in the Premier League except Trent Alexander-Arnold, who had teammates a fair bit better than Sessegnon’s. A move to Spurs has been heavily rumoured and Mauricio Pochettino could well help him develop his obvious talent. While Sessegnon offers a lot on the ball in the final third, his acceleration could better suit starting at the left-back role from which he can move up the pitch. Here he could easily challenge Ben Chilwell and Luke Shaw for that England spot in the long term.

If any young player is obviously being groomed to make the leap to the senior team eventually, it’s Phil Foden. Player of the tournament in the Under-17 World Cup two years ago, Foden has transitioned to the Under-21 side without an issue, proving to be England’s outstanding performer against France. Of course, playing for Manchester City is both a blessing and a curse, as he has both the ideal manager to develop under and perhaps the toughest pathway to a starting role in world football. It’s very easy to imagine Foden playing less than 1000 league minutes next season and this would be a not insignificant hinderance to his development. Nonetheless, his talent is so obvious that even in those circumstances, one could imagine Southgate taking him to Euro 2020 as the 23rd man in the squad.

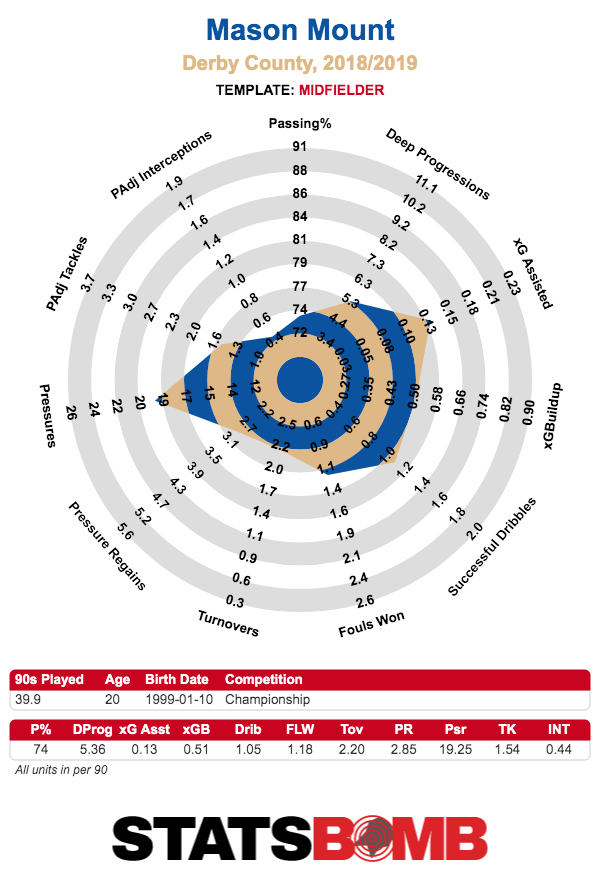

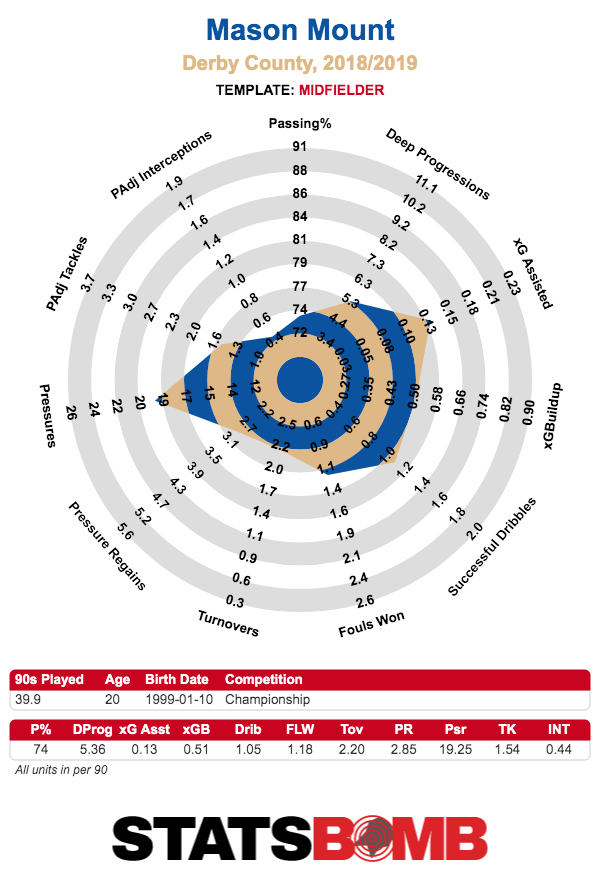

There are a lot of reasons to be sceptical of Frank Lampard’s appointment as Chelsea manager, but it could be good news for more than a few young English players. Mason Mount may or may not be ready to play Champions League football. What he does have is a season under Lampard at Derby, and if the new boss at Stamford Bridge takes some time to get Chelsea playing the way he wants, he may look to people who already understand what that is. Mount was more of a solid contributor at Derby than anything spectacular, but Lampard is clearly a fan, and anyone who gets serious minutes for Chelsea is likely to be in the England frame almost by default (see: Barkley, Ross).

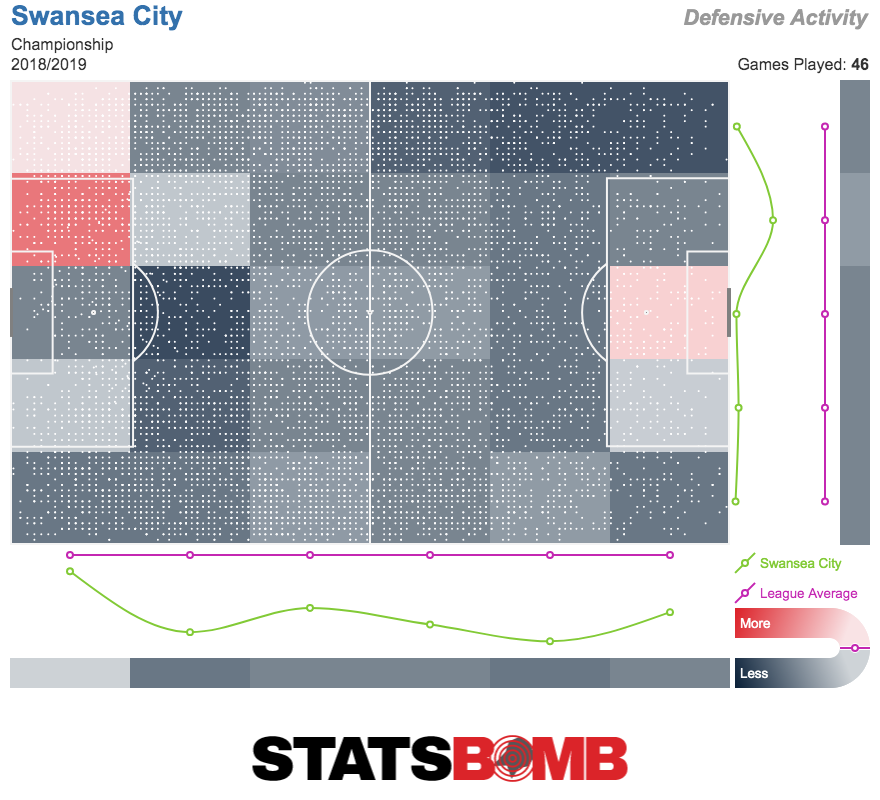

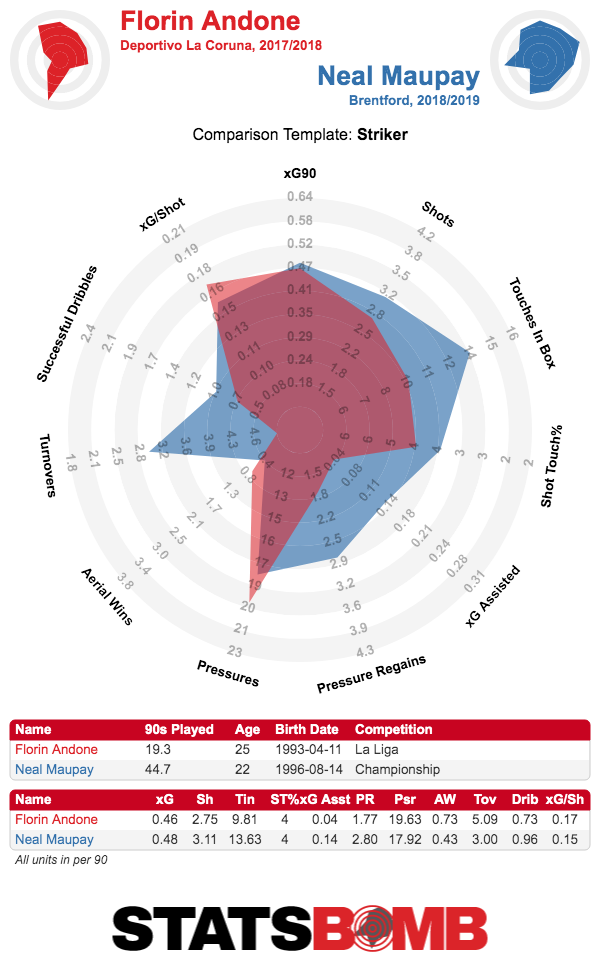

In much the same boat is perennial StatsBomb favourite Tammy Abraham. Across two seasons in the Championship, the 21-year-old has scored 41 non-penalty goals, at a rate of just over half a goal per 90. Sandwiched in between those two second-tier seasons was a year at Swansea. While this year was deemed a failure by many (enough for Chelsea to send him back down a division), it came at a truly awful attacking side that spent a lot of time relying on the “playmaking” abilities of Tom Carroll and Sam Clucas.

Despite having as close as a striker will ever get to no service, Abraham still put up a solid 0.31 expected goals per 90, the best rate of any young English player outside the top six. Chelsea’s past disinterest in promoting young players has been particularly tough on Abraham, but he could well be the one to benefit the most from Lampard’s appointment. The solid-but-unspectacular Callum Wilson currently serves as England’s back up to Harry Kane and it’s not unreasonable for Abraham to target overtaking the Bournemouth man this season.

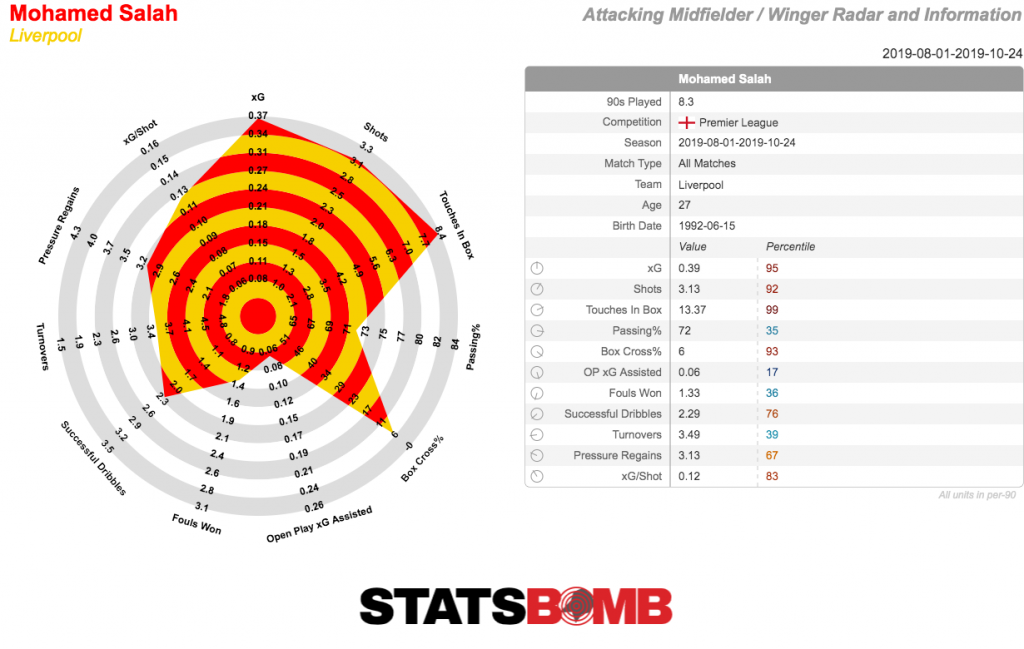

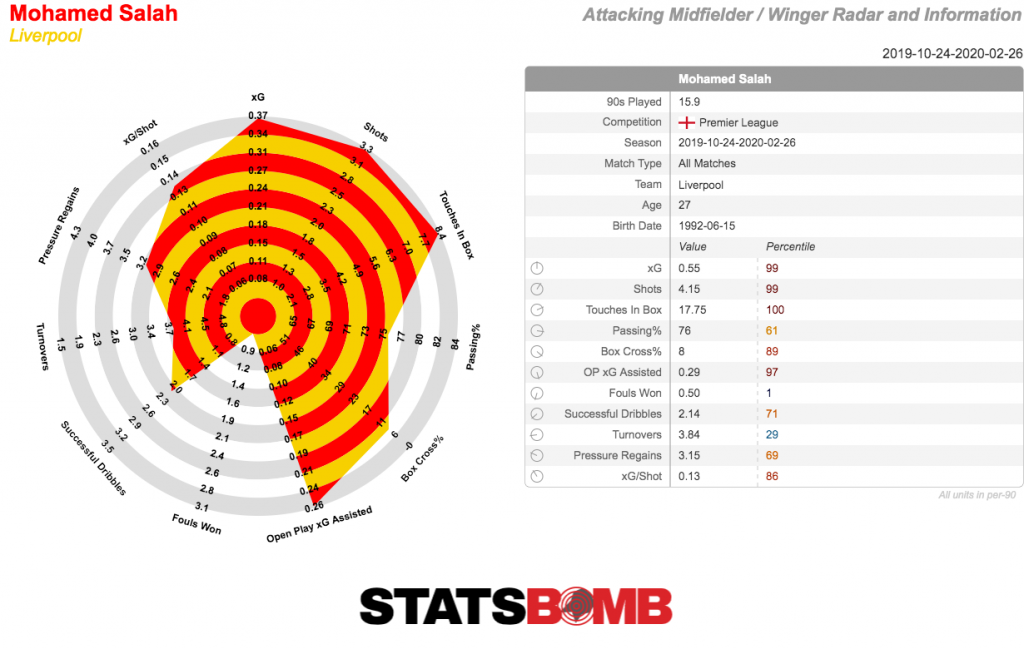

Wilson could well also face competition closer to home, and I’d be remiss not to mention another past stats (and personal) favourite here. His Bournemouth colleague Dominic Solanke is highly thought of within the England youth setup, having won the Golden Ball at the 2017 Under-20 World Cup and continued his good work at Under-21 level with nine goals in 18 appearances. On a purely numbers level, his time at Liverpool was fairly ridiculous in a very small sample size, putting up a figure of 0.76 expected goals and expected goals assisted per 90, better than anyone at the club save for Mohamed Salah. It’s entirely possible that this small sample size was wildly unrepresentative of his true ability, and some injury issues have seen him not yet hit his stride at Bournemouth, but it’s definitely possible that he could establish himself as Bournemouth’s most important striker, and Southgate would be hard pressed to take Wilson ahead of him next summer.

Tier Three: Longer Term Bets

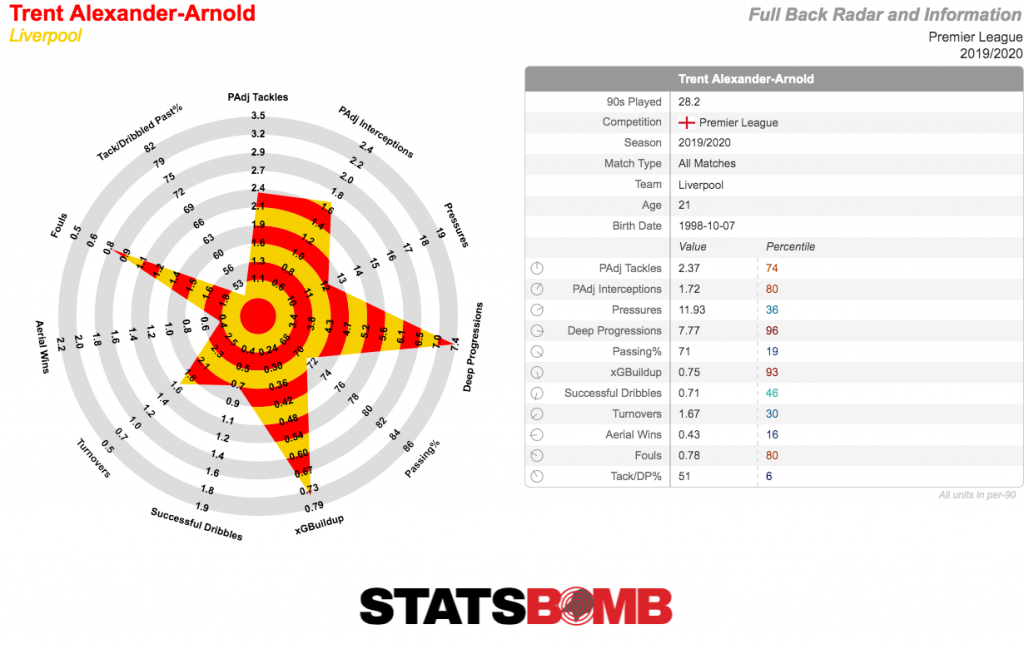

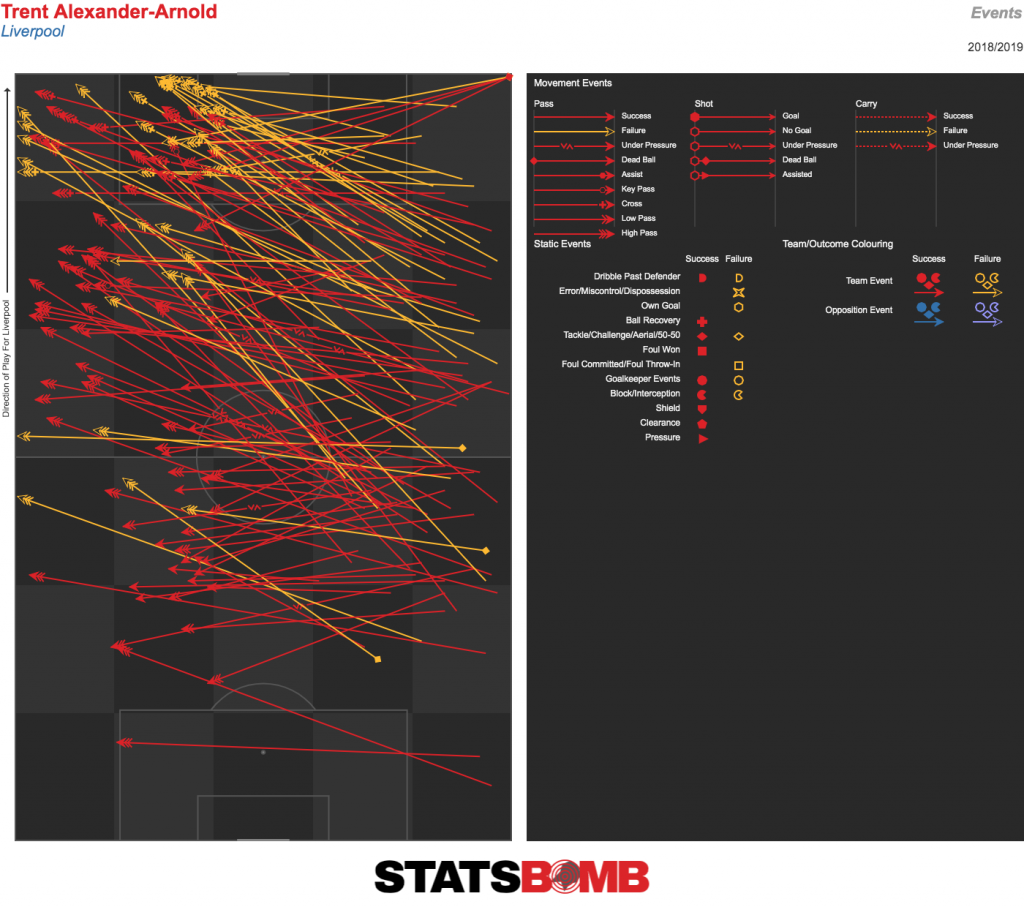

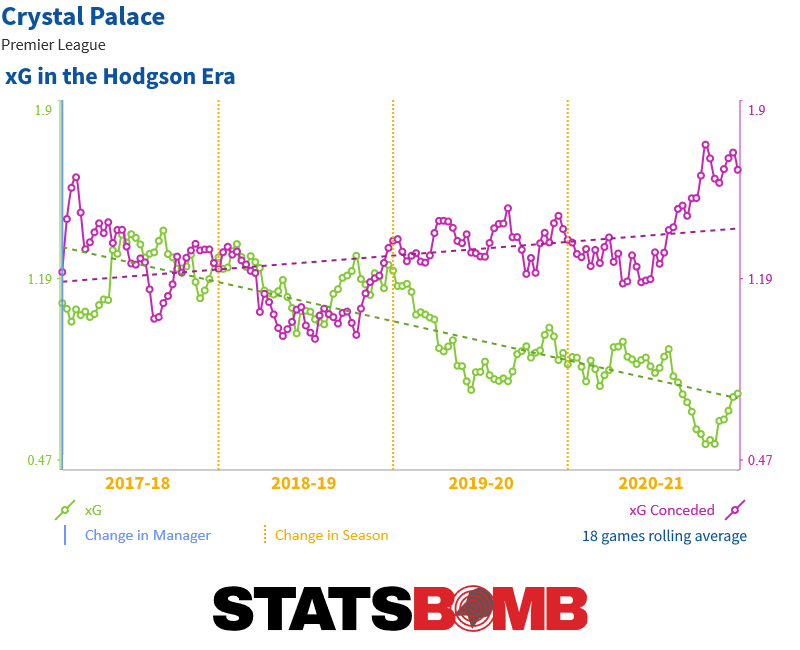

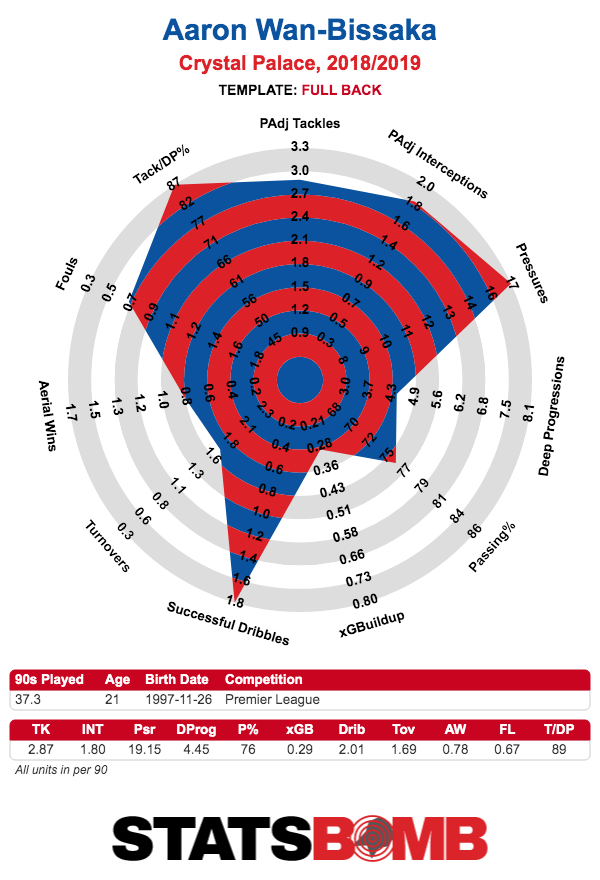

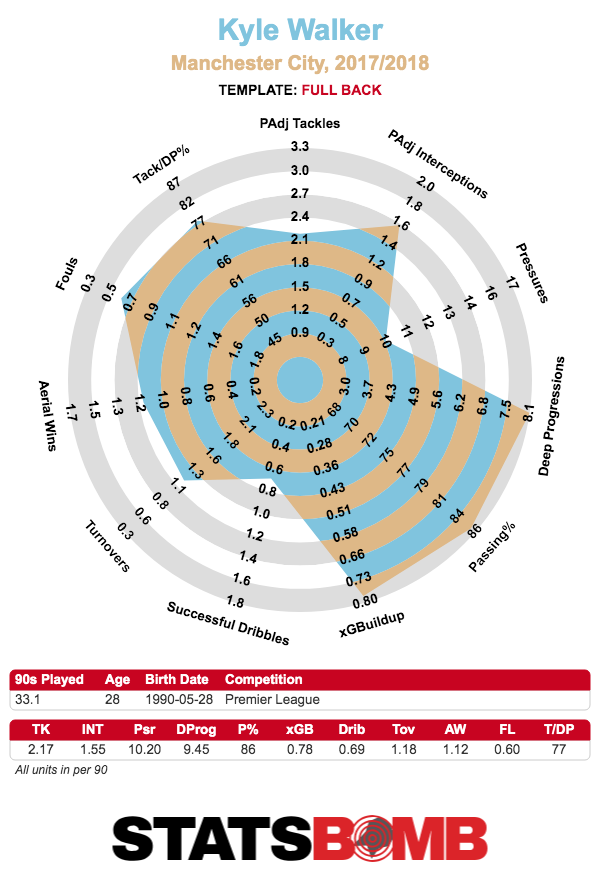

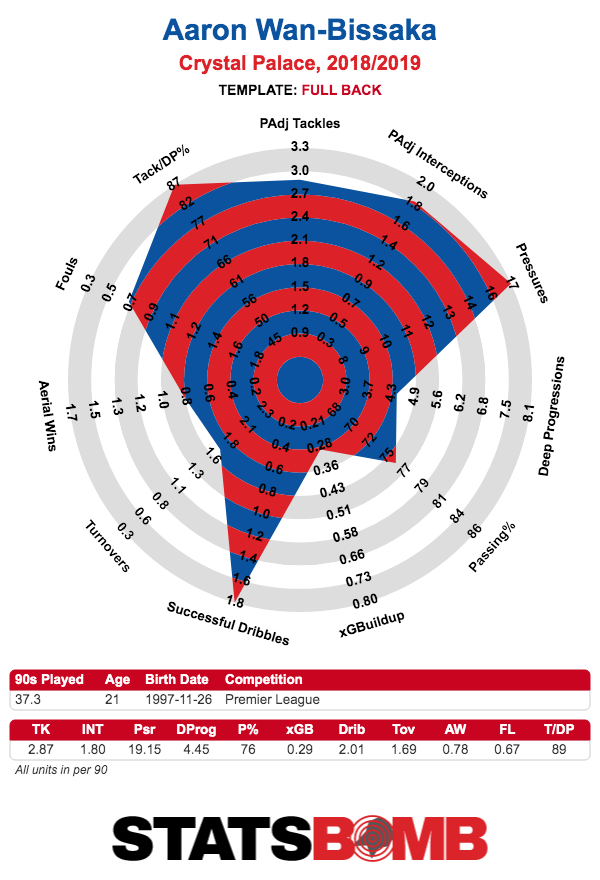

Aaron Wan-Bissaka might be the unluckiest player on this list. The right-back had a huge breakout season for Crystal Palace, earning widespread plaudits and getting a big money move to Manchester United. Were he playing just about anywhere else on the pitch, he’d be a shoo-in for the England squad. As it is, Kyle Walker has fully established himself as the country’s first choice right-back while Trent Alexander-Arnold stands just behind him as one of the most promising young English players in any position. Wan-Bissaka is another player Mohamed wrote about recently for StatsBomb, and most of it remains relevant in an England context:

“Manchester United potentially spending up to £50 million on Wan-Bissaka represents a bet on him eventually becoming one of the better fullbacks in the world two to three years from now. For that to occur, his offensive value will have to get to a high enough level through ironing out some of the kinks. Given how good he projects to be defensively over the next few years, it might be that he merely needs to be a slight net-positive offensively rather than a no-doubt stud in attack. It’s not impossible to imagine that being the case for Wan-Bissaka: his dribbling abilities are outstanding and that alone brings value. His passing isn’t a lost cause, though it’s not a strength yet.

The hope is that his dribbling abilities continue to translate and create passing opportunities for him that it wouldn’t exist for others, and with more reps in advanced areas as well as playing with talented teammates at United, he becomes a better offensive player. That version of Wan-Bissaka would be more than worth the high price tag that United will reportedly paid for his services. The more pessimistic angle would be that Wan-Bissaka’s passing never appreciably develops from its current state, and as a result, his game doesn’t quite scale up to the highest level of competition and makes him less of an asset.”

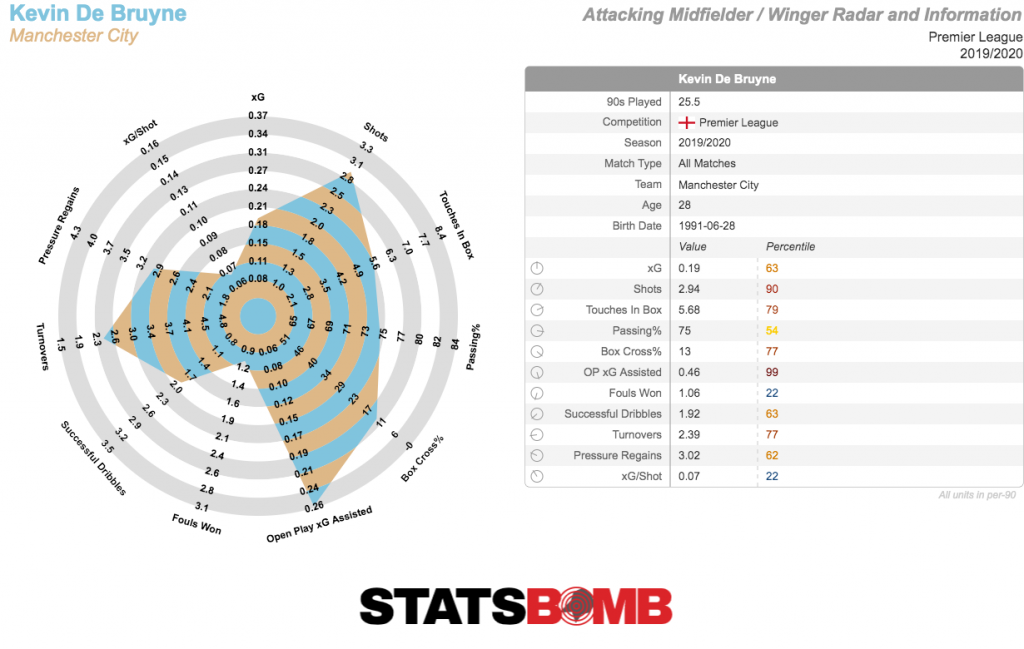

It’s hard to disagree with Mohamed’s central thesis: that Wan-Bissaka is an excellent defensive full back who offers much in terms of dribbling ability but needs to improve his passing. This feels in complete contrast to his England rival Alexander-Arnold, who offers so much on the ball but at times gets caught out by fast wide players. The race to become Walker’s successor might be one about seeing who can add the other side to their game first. Right now, the Liverpool player seems very much in front, but time could be on the new Old Trafford arrival’s side if he can continue to improve.

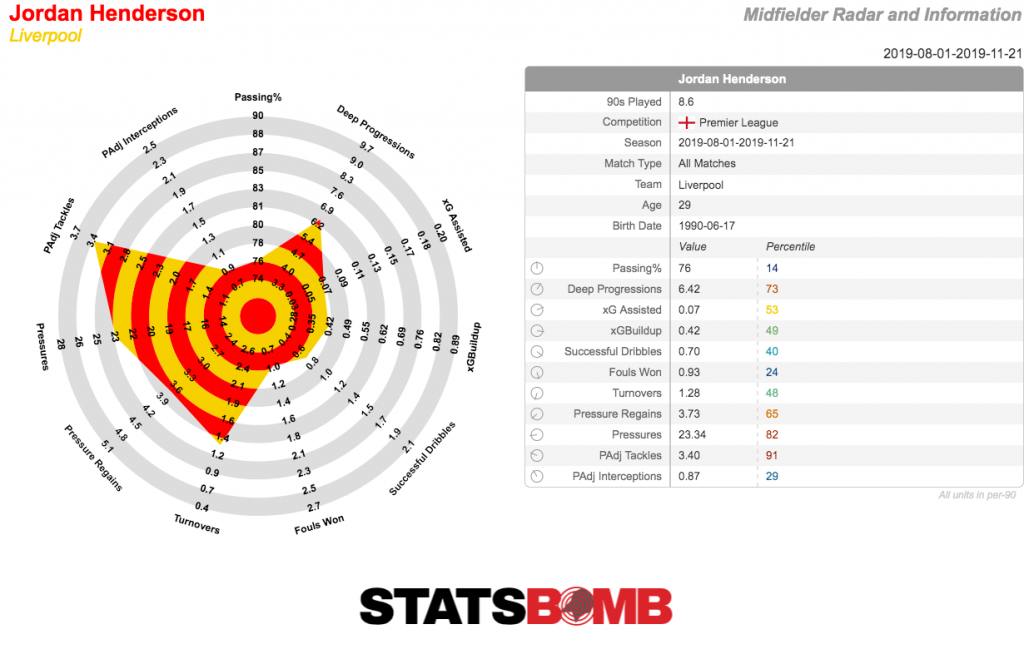

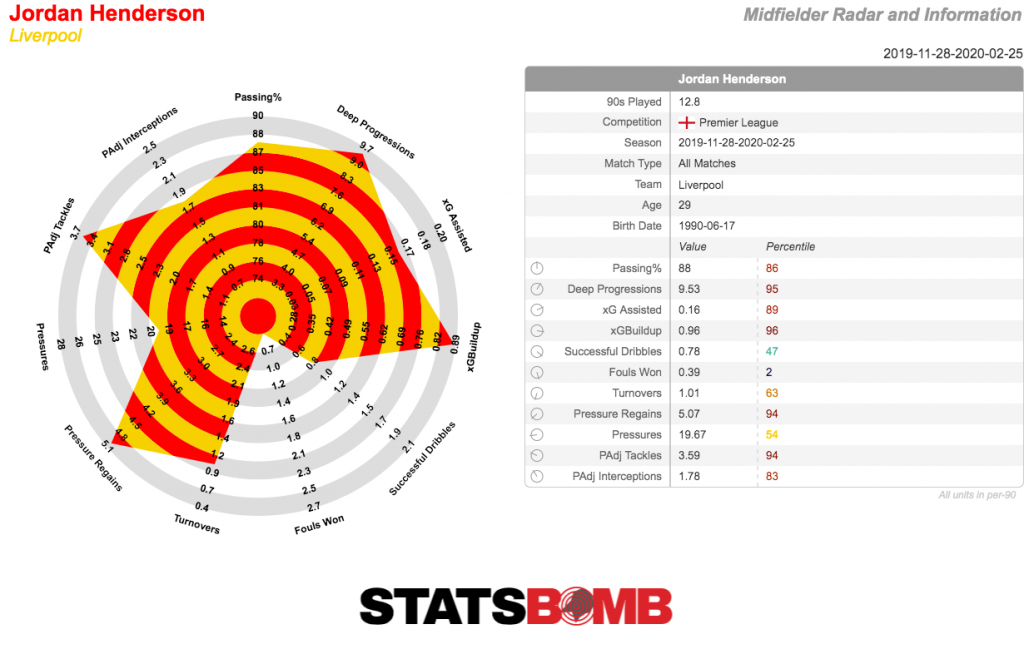

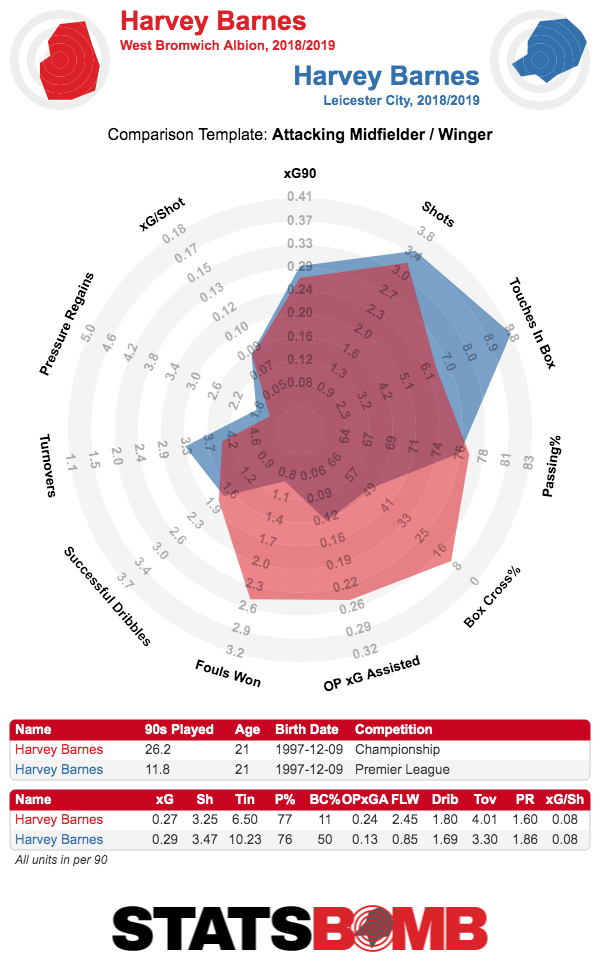

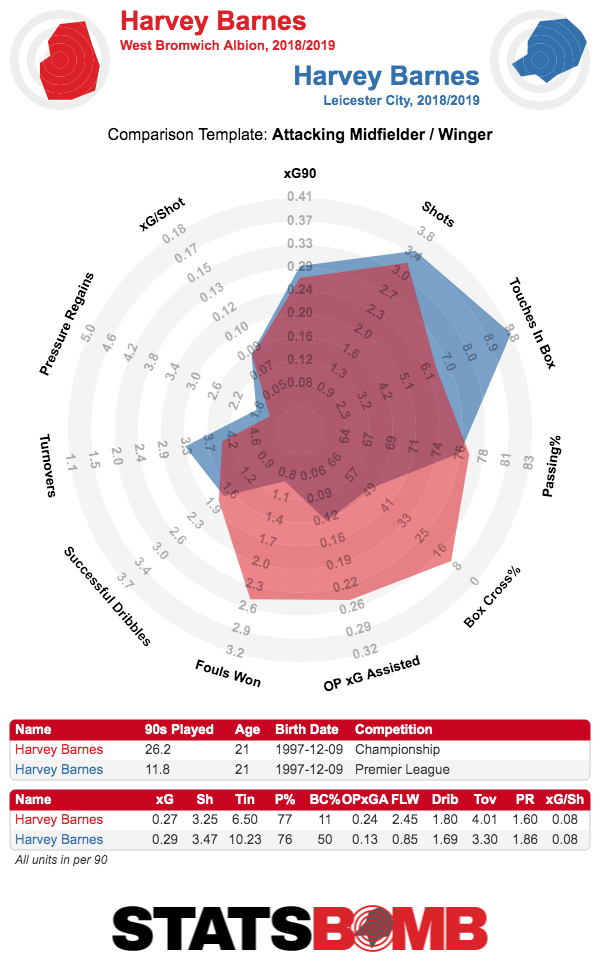

Leicester pair Harvey Barnes and Hamza Choudhury have both acquitted themselves well under Brendan Rodgers and could easily make the jump to the national side at some point. In his half-season loan to West Brom, Barnes had the highest scoring contribution of any young English player in the Championship, with expected numbers largely backing up these performances. As one would expect, his numbers were a little worse when returning to the Premier League, but still offered enough as a solid wide forward contributor to suggest there could be a real player here. Choudhury, meanwhile, has put up big defensive midfield numbers in limited minutes. Leicester already have one of the league’s better aggressive ball-winning midfielders in Wilfried Ndidi, so minutes are limited for the youngster, but Rodgers has shown willingness to use them both in big games. Choudhury probably can’t contribute to England right now, but as Jordan Henderson ages out of the side and Eric Dier seemingly won’t push on, there may be an opening for him in the future.

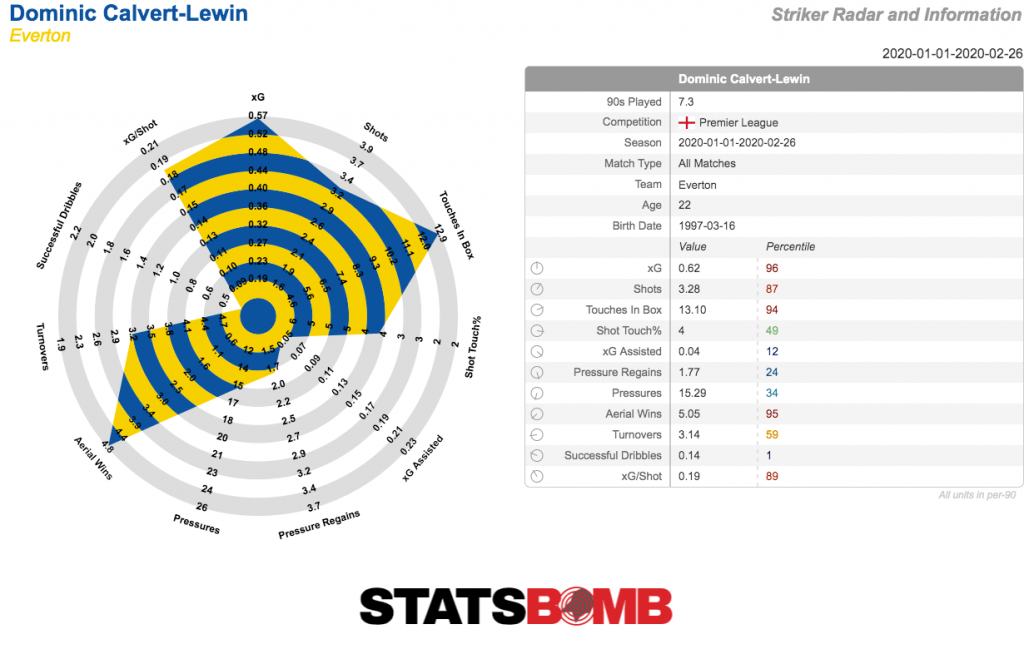

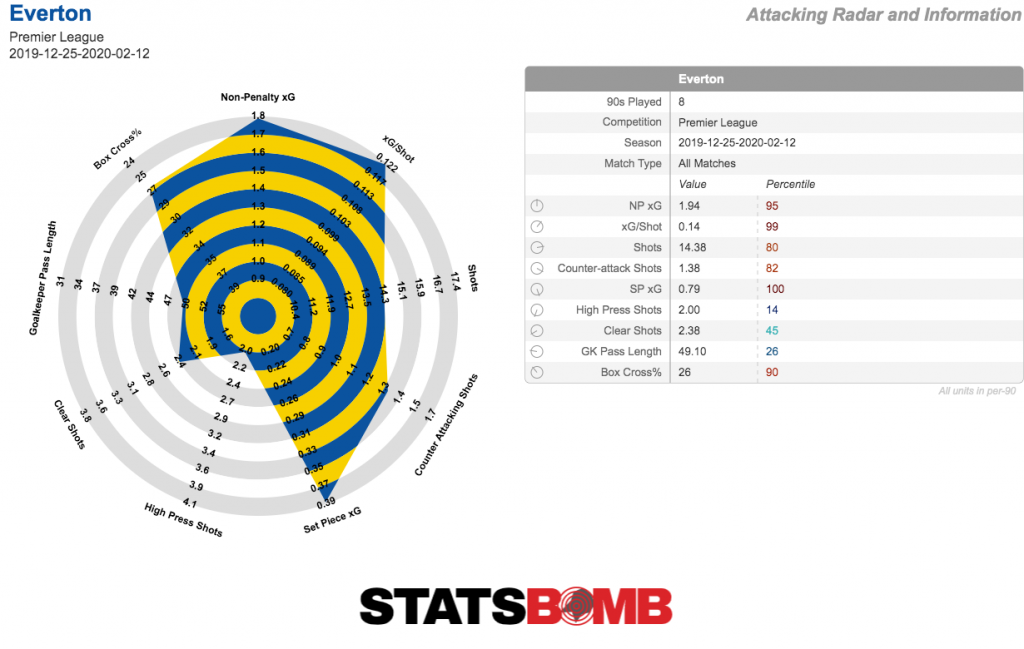

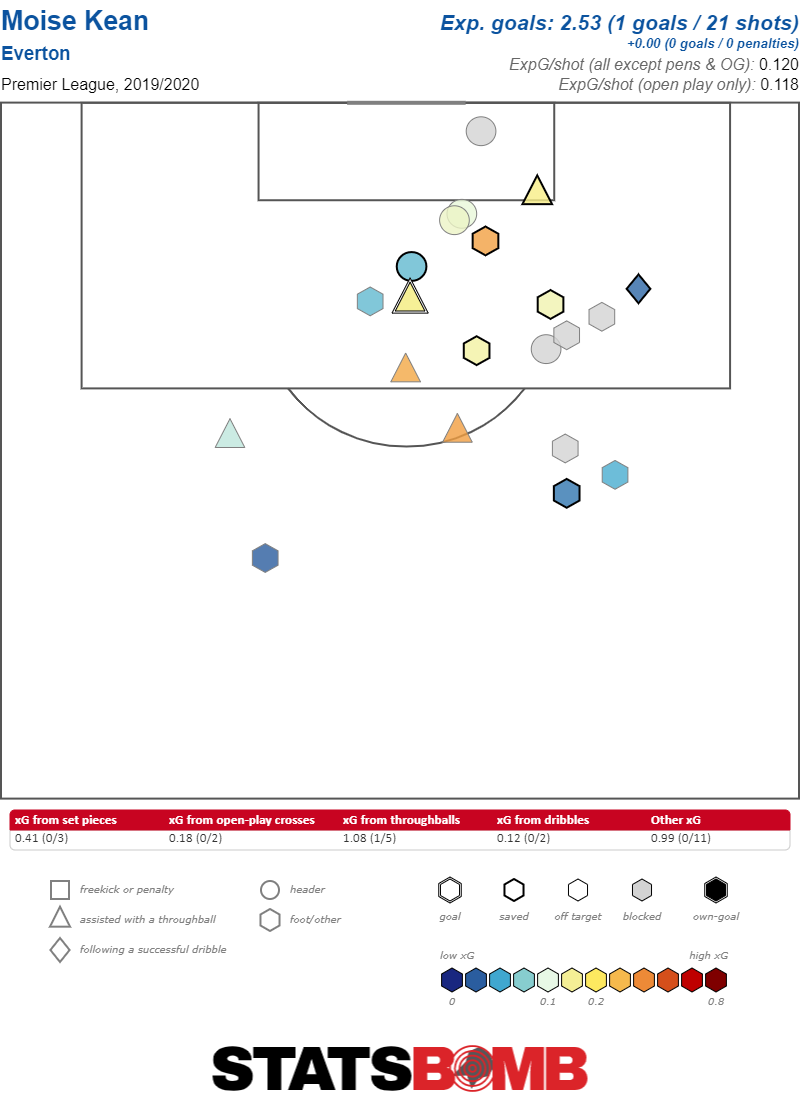

Dominic Calvert-Lewin has been knocking around international youth football for some time now without ever seriously threatening to break into the senior team, but he still looks capable of doing so. His 3.9 aerial wins per 90 in the Premier League last season puts him as one of the more dominant target men in the division, and it’s relatively rare for someone to match that with the burst of pace that he has. Calvert-Lewin is still a fairly unimpressive goal threat, getting just six last year from 22.1 90s, but the raw tools are such that he could be an excellent all-round forward in a few years.

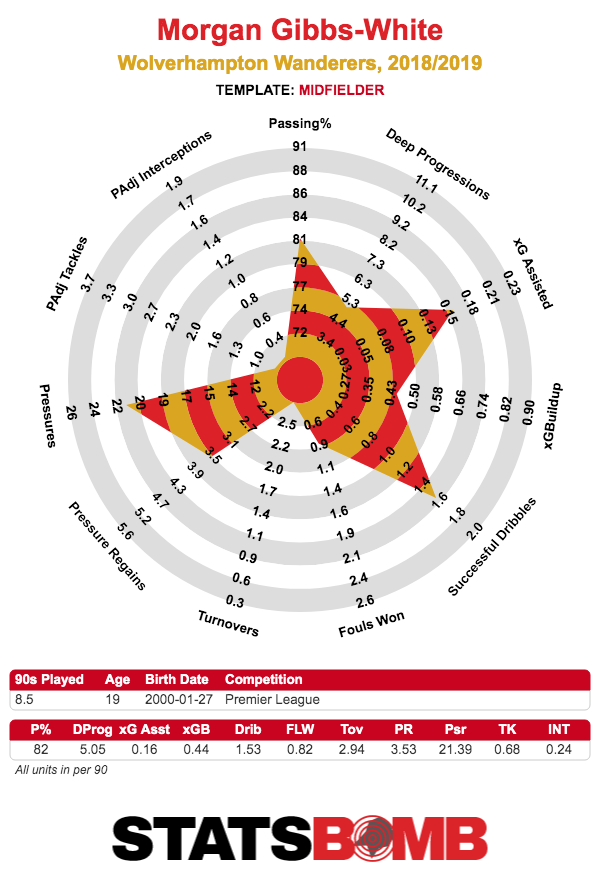

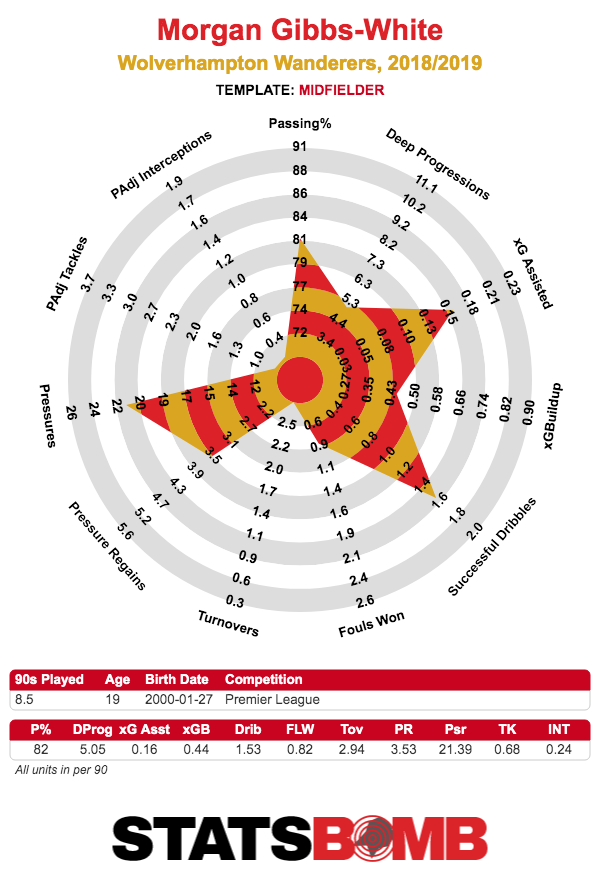

Morgan Gibbs-White could have the highest ceiling of anyone in this squad bar Foden, though there is still quite a lot of work that needs to be done to get there. The Wolves man was an impressive cog in the Under-17 World Cup winning side, failing to get the headlines of Foden or Rhian Brewster but still looking a cut above most of the others in the knockout stages. While his role in that tournament was out wide, most of his minutes for Wolves have been in more of a central, creative midfield role, and he may end up moving even deeper. Like many young players, it’s not obvious what he’ll end up being, but as a technique player capable of a dribble he should be able to fit in somewhere.

Elsewhere, Reiss Nelson was heavily flattered by a goal return in the Bundesliga last season of seven from an expected total of 1.94, but he nonetheless seems a useful wide forward who should hopefully get minutes for Arsenal next season and is young enough at 19 that he has time to develop into something more. Centre-backs are perhaps the most difficult position to project future success onto, since it relies so much on both surroundings and reading of the game that can develop a little later. Nonetheless, Derby’s player of the season Fikayo Tomori hasn’t done anything wrong yet. A fairly aggressive front foot defender, he should suit the relatively high pressing style that England want to implement long term. Lloyd Kelly has largely played left-back so far in his career, but the centre is probably his final destination. If past performance is an indicator, he’s going to a lot of defending to do under Eddie Howe’s style at Bournemouth, so there should be plenty of learning opportunities. Similarly, Ezri Konsa is making the Premier League jump after a year in the Championship and has a reasonable shot at being a very good defender, but it’s difficult to predict what he will end up being.

Tier Four: Longer Shots

It might be harsh to put Jonjoe Kenny in this category. He’s a right back who provides solid defensive work and decent attacking play with rare dominance in the air from that position. But if Wan-Bissaka is unlucky to have to compete against this right-back crop, the argument applies doubly so to Kenny.

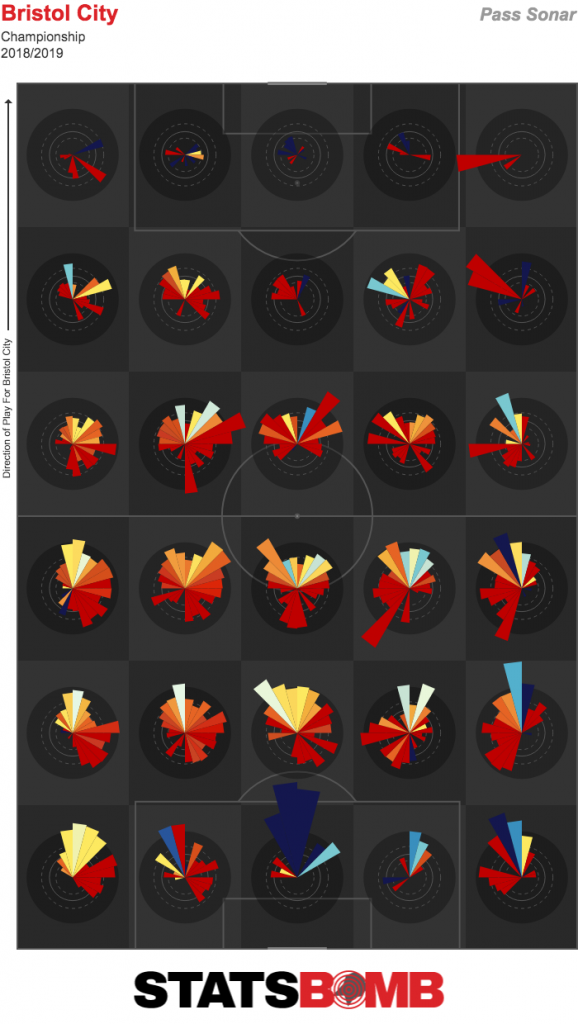

Similarly, Jake Clarke-Salter could easily be in the above group, but for a 21-year-old Chelsea loanee to still spend time at Vitesse does not suggest he is considered a future star by the Stamford Bridge hierarchy. If he doesn’t at least go to a decent Championship side this season, he should be thinking about a permanent move away from Chelsea. Someone who has quit the Stamford Bridge loan army is Jay Dasilva, a solid all round left-back now owned by Bristol. He may surprise us, but considering Chilwell is only a year older than him as England’s established starter in that role, and he doesn’t have the upside of someone like Sessegnon, the future may not be bright for his England career. Kieran Dowell probably has a future at Premier League level, but it just might not be for England. After Choudhury was sent off in the first game and England lacked any other natural defensive midfielders, Dowell moved to the deeper role and looked as though his passing could be a threat from that position, perhaps more so than higher up the pitch. Spending the second half of last season on loan at Sheffield United, he looked ok, and will spend another year in the Championship at Derby. Dowell could be a solid player eventually, but it doesn't seem like he’s particularly special.

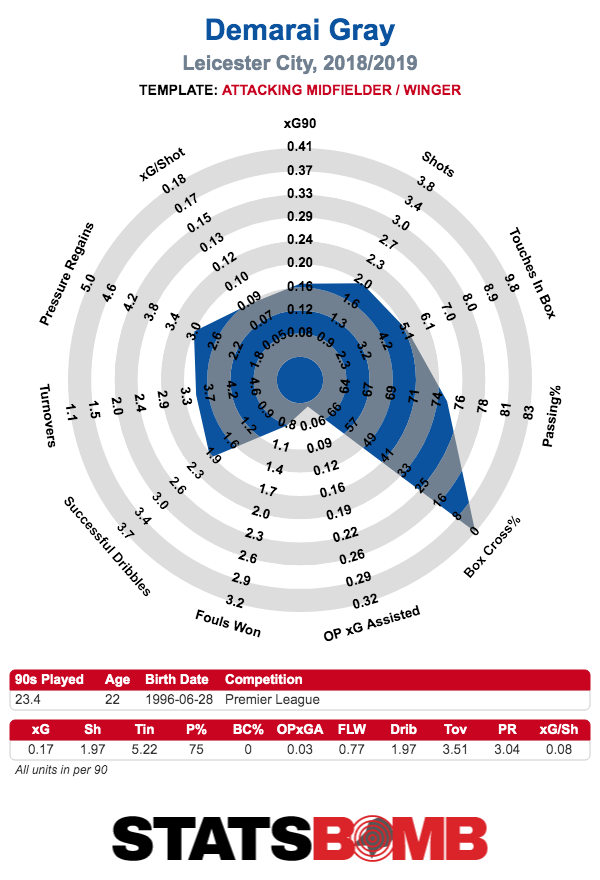

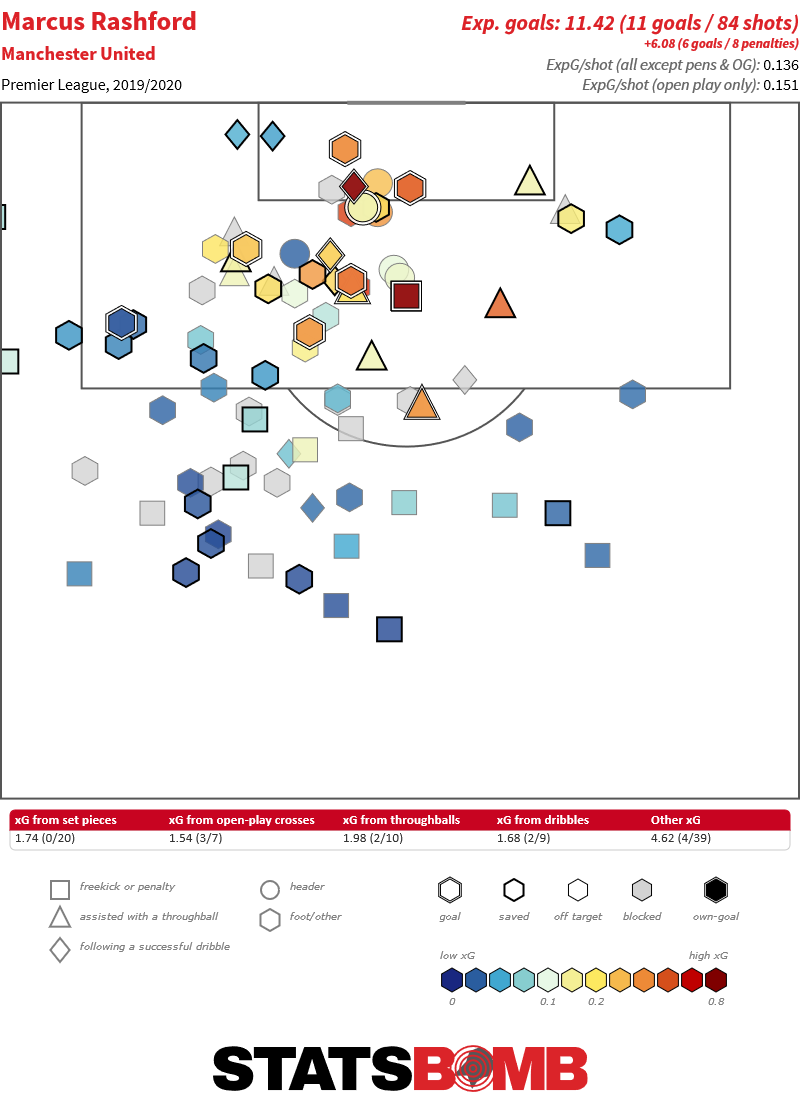

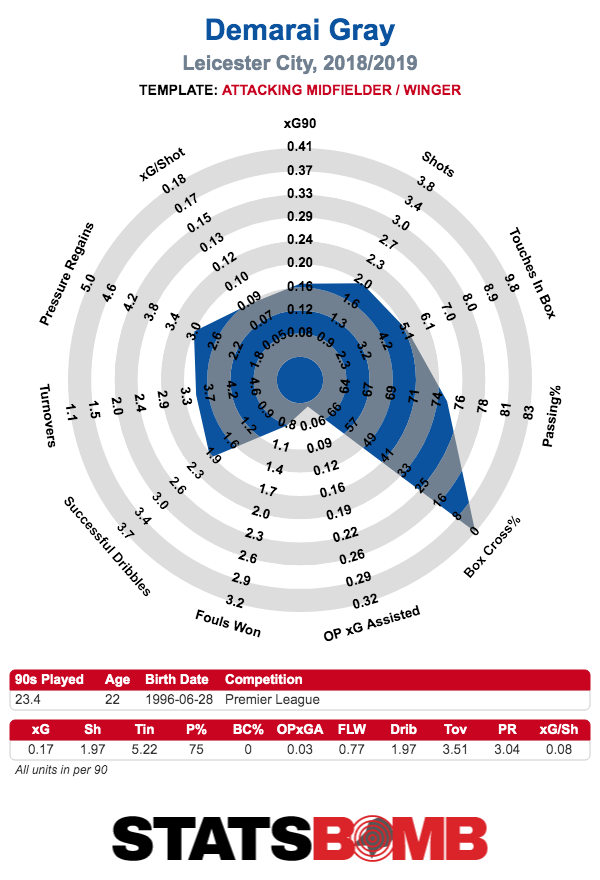

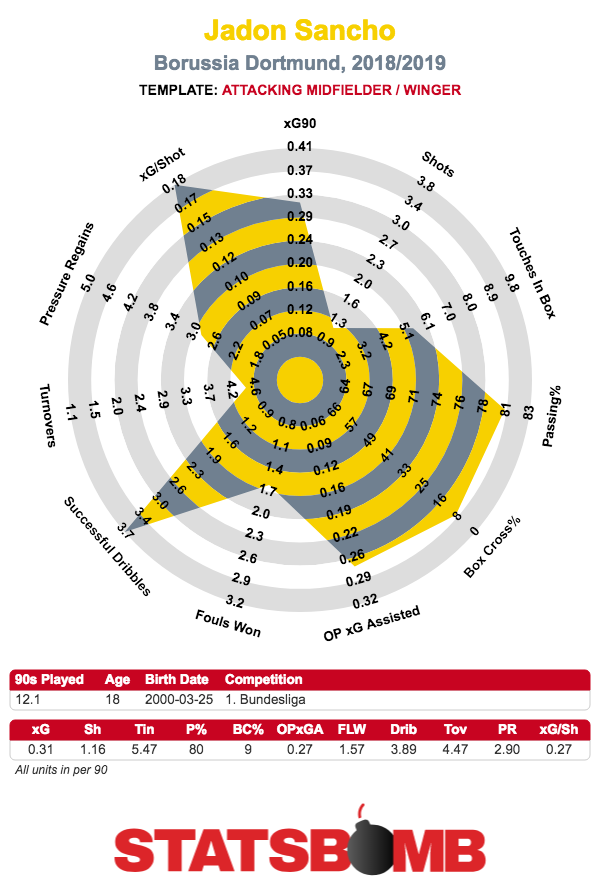

Last and, to be brutally honest, least is Demarai Gray. At 22, he is no longer eligible for the Under-21 side, and in truth it’s not obvious that he should have played as much as he did at the Euros. Jadon Sancho and Callum Hudson-Odoi are both significantly younger than Gray and have already jumped well ahead of him in terms of Southgate’s wide options. Even Marcus Rashford is younger than the Leicester winger. Looking at his numbers, it’s hard to find anything that stands out as really exciting. All the best, Demarai.