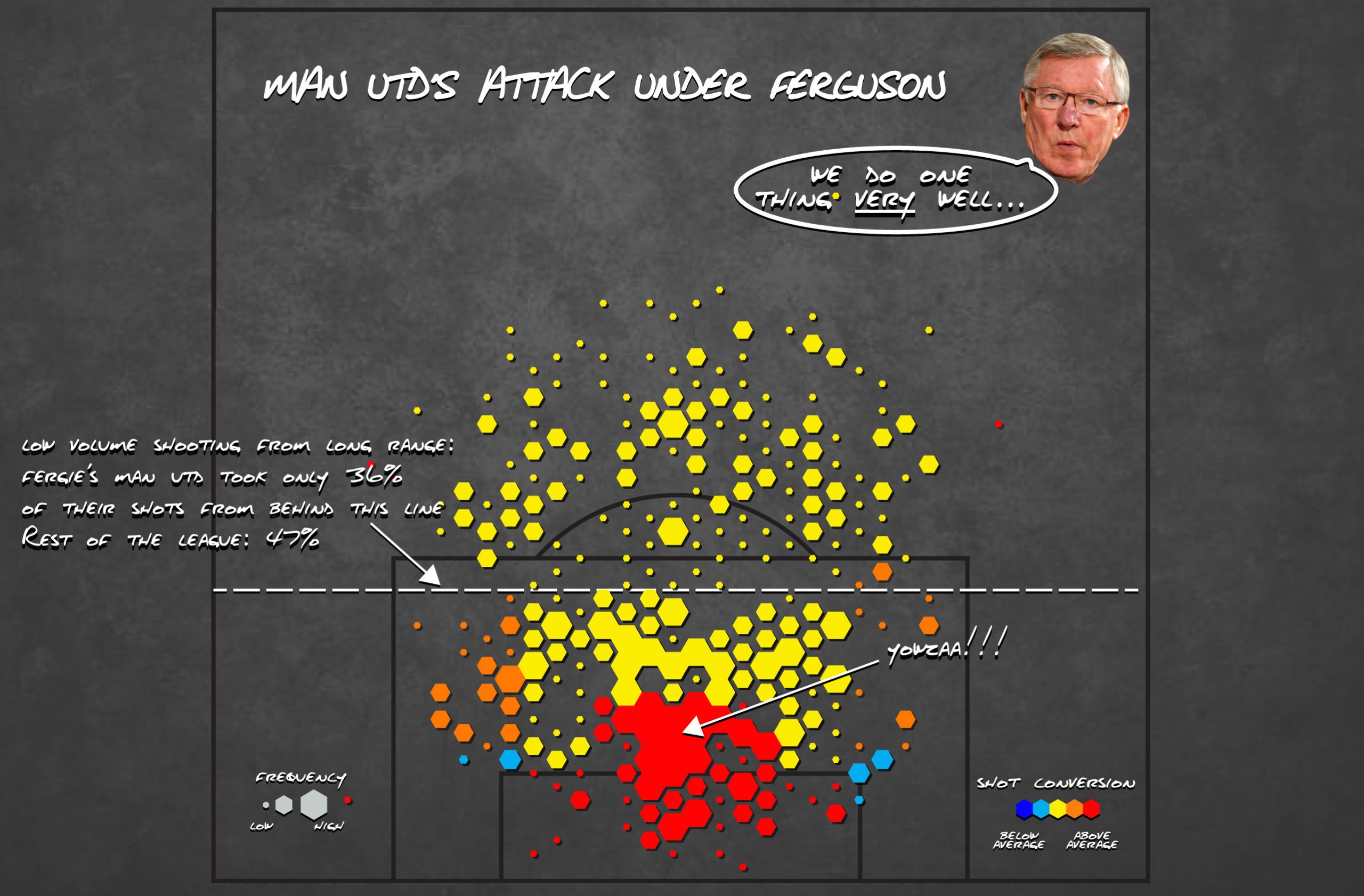

In part one of this piece, I said that Alex Ferguson’s 2012/13 Man United team drastically overachieved their expected goals total and I showed where almost all of the extra goals came from (in and around the edge of the six-yard box). In part two, I’m going to explain how United posted such an underwhelming shots profile despite being a dominant team.

Strangely enough, it all starts with Theo Walcott…

The ‘Walcott Effect’

At some point after the 2011/12 Premier League season, Paul Riley posted a piece in his blog about Theo Walcott’s crossing. In it, he described how rarely Walcott’s crosses found their target.

Here’s Riley,

“It takes [Walcott] nearly two games to put in an accurate cross. He crossed the ball 134 times last year. Only 18 (EIGHTEEN) of them found a teammate.”

But (more Riley),

“When you look closer at Walcott’s accurate crosses the only way to describe them is ‘devastating’. 8[1] of the 18 crosses have been assists.”

It’s counterintuitive: less shots, more goals.

Now you could chalk that down to fluke, or to some otherworldly finishing performance by the other Arsenal players[2], but Riley doesn’t buy it. He thinks that when Walcott’s good at ‘putting it on a plate’ for his teammates. He shows how 6 of the 8 Walcott cross-assists come deep inside the opposition box, and makes is easy to imagine how Walcott’s crosses are easier to finish than the deliveries of the ‘into the mixer’ crowd.

He’s convincing because it jibes with what you see when you watch football. Getting into the opposition box with the ball at feet is the scariest thing a wide player can do. That’s what makes the Theo Walcotts, the Angel di Marias, and of course, the Cristiano Ronaldos of this world so good. When they do that, everything goes to shit; goalies stay pinned to their lines, defenders abandon their assignments, and the whole time, they’re all too terrified to make a tackle.

Buuutttttt… But it makes it harder to cross the ball. Put yourself in Theo’s shoes. You’ve left your man for dead, you’re in the box with the ball at your feet. It’s nice that you’ve pulled all these players out of position, away from the men they’re supposed to be marking, but it means they’re coming for you! They’re blocking your shot, they’re clogging up your passing lanes, not to mention that unless you place your delivery within inches of your striker’s foot or noggin, he’s not going to be able to react fast enough to direct the ball towards goal.

That said, if you can manage to thread the eye of the needle, if that cross finds its way to a teammate, almost any shot on target is going to be a goal.

When you’re reading the stats, that looks like less shots, more goals.

Maybe you can see where I’m going with this…

Heating Up

Look at the wide players on that 2012/13 United team; Patrice Evra, Rafael, Nani, Antonio Valencia. There’s no messing about with ‘central wingers’ or ‘inverted fullbacks’, those are true-footed players with dribbling skills and real speed.

You like overlapping runs? Eat your heart out.

Those Walcott-esque crosses are the type of deliveries this 2012/13 Man United attack was designed to create.

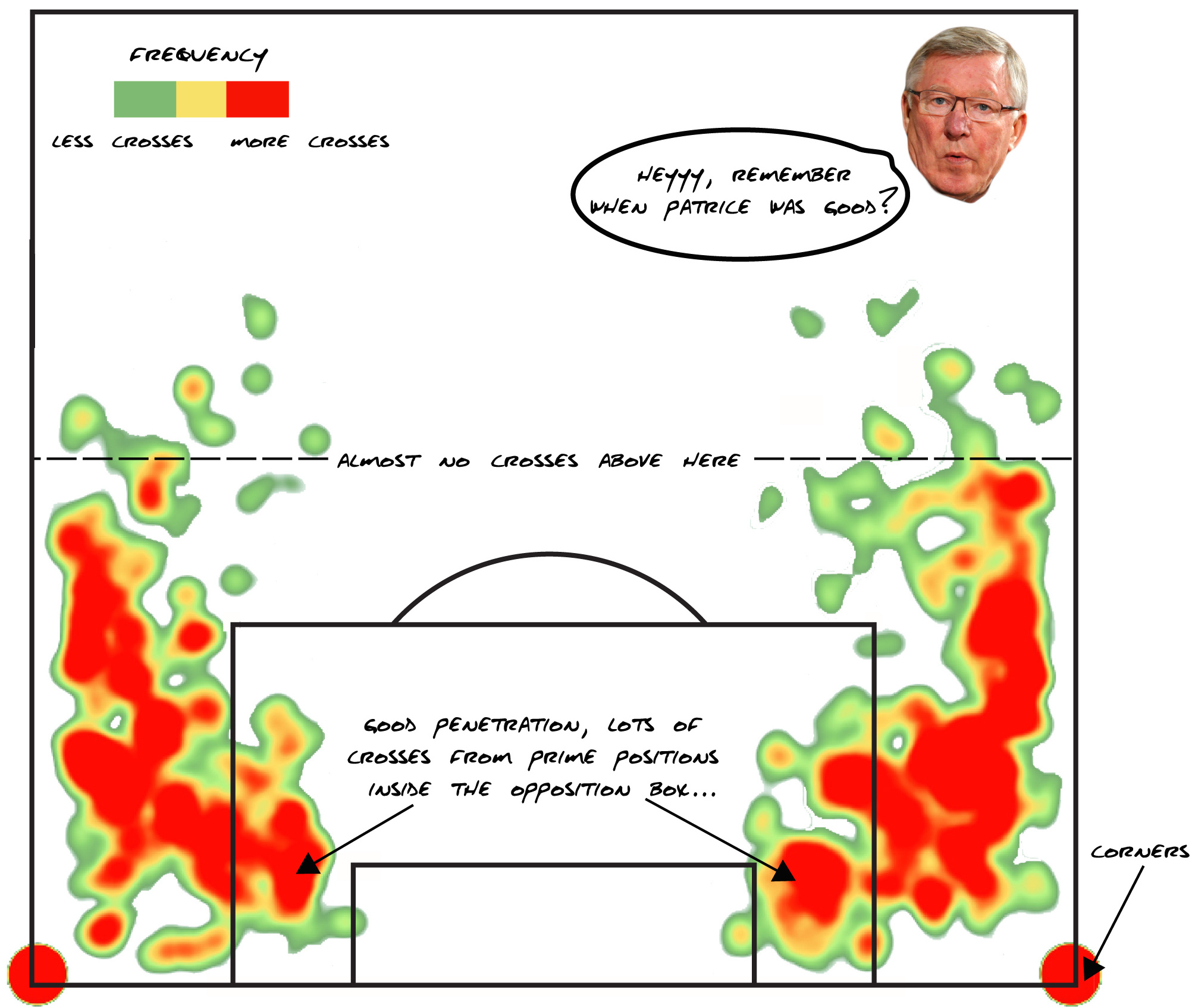

Don’t believe me? Take a look.

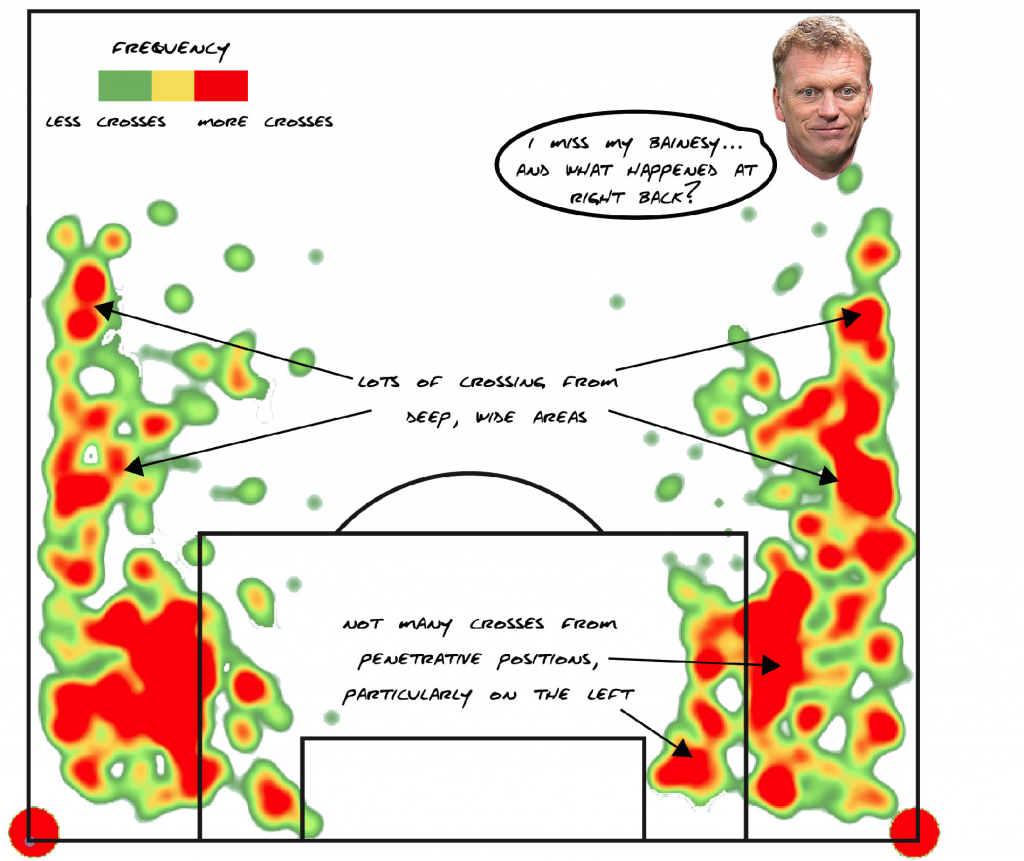

That’s a heat map of all the crosses United took in the 2012/13 season (actually I’m missing data from a couple of games, but you get the idea). The second, just for comparison’s sake, is a heat map of the crosses United took when David Moyes was in charge. The difference is stark, Ned Stark.

Both 2012/13 and 2013/14 United based their attacking philosophy around crossing. Under Fergie, United actually crossed the ball (~25 per game under Fergie vs. ~24 per game under Moyes).

It just didn’t feel like that.

‘Moyes’ men’ lobbed in a lot of crosses from deeper positions, and even when they got closer in, they rarely penetrated the opposition box. On the other hand, ‘Fergie’s buoys’ passed up on the lottery balls and frequently crossed from position deep inside enemy territory. I’m not putting that all on Moyes; Evra was on the wrong side of the aging curve; Rafael was in and out of the lineup with injury. But some it’s his fault; he tinkered constantly; he played guys like Phil Jones and Chris Smalling at fullback… But that’s a different discussion.

Why Fergie’s 2012/13 United Team Fucks Up Your ExpG Models

Phantoms. That’s what I’m calling them anyway. Goal-scoring opportunities that never have the chance to be registered in shot-based ExpG models, because they never turn into shots. These crosses are difficult to complete. It’s hard to pass through a thicket of defenders, and on the finishing side, it’s hard to react fast enough to get shot off. But make no mistake, even the ones that don’t make it to feet are (non-negligible) chances to score.

If you fail to take them into account, if you don’t include them in your expected goals models, you will be underestimating teams that use these tactics. Team like Alex Ferguson’s 2012/13 Man United.

Other Factors

The ‘Walcott Effect’ is not the only reason why 2012/13 United deceive ExpG models, but this article is already too long, and those other factors have been intelligently covered elsewhere. But briefly…

Robin Van Persie is Very Good at Scoring Goals

Robin Van Persie is an underrated passer, an intelligent runner, and has perfect balance and technique. He’s very good in any type of offense, but he was the perfect finisher for this ‘drive and kick’ style offense.

Robin Van Persie is Great at Taking Set Pieces

Possibly the one thing Van Persie does better than finishing is taking set-pieces. In case watching Arsenal struggle flounder on set-pieces over the last few seasons wasn’t enough, this is Mike L. Goodman writing for Grantland:

“Last season (2012/13), in the attacking third when van Persie was on the field, he was responsible for 49.8 percent of all free kicks taken by United.”

And that for a side which overachieved its ExpG values from set-pieces by a pretty ludicrous margin.

Winning Penalties and Scoring Own Goals Can Be a Skill

There’s a good deal of luck that goes into getting these freebies, but you have to think that a team which specialises in putting the ball at the feet of quick-footed dribblers who attack the box (and whip in balls from the byline) has a good chance of getting a few of both each season.

The 2012/13 Man United vintage was not lucky, it was a dominant team that had the title race sewn up by April. Fergie’s ‘buoys’ were well trained at set pieces and they had an elite finisher in Robin Van Persie. But that extra ‘oomph’ in conversion rate? That was the result of phantoms: goal-scoring opportunities that don’t show up as shots. It’s not sorcery, it’s not special sauce, it’s not some kind of cosmic imbalance. It’s just what a ‘drive and kick’ offense looks like on a football pitch.

[1] Riley actually says 6 of 18, but then goes on to talk about 8 cross-assists, so I think it’s 8 of 18. [2]

After all, he was playing with Robin Van Persie that year.