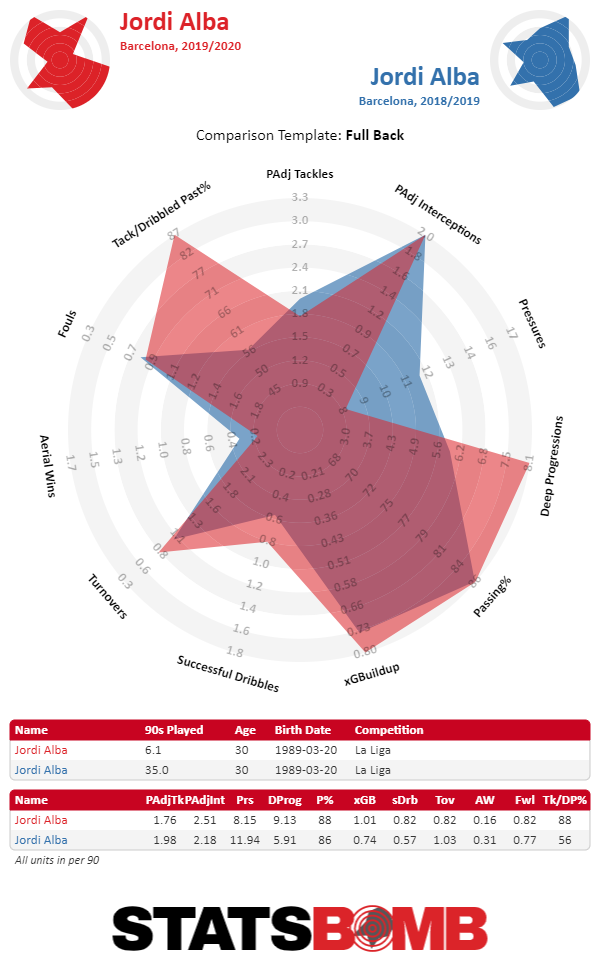

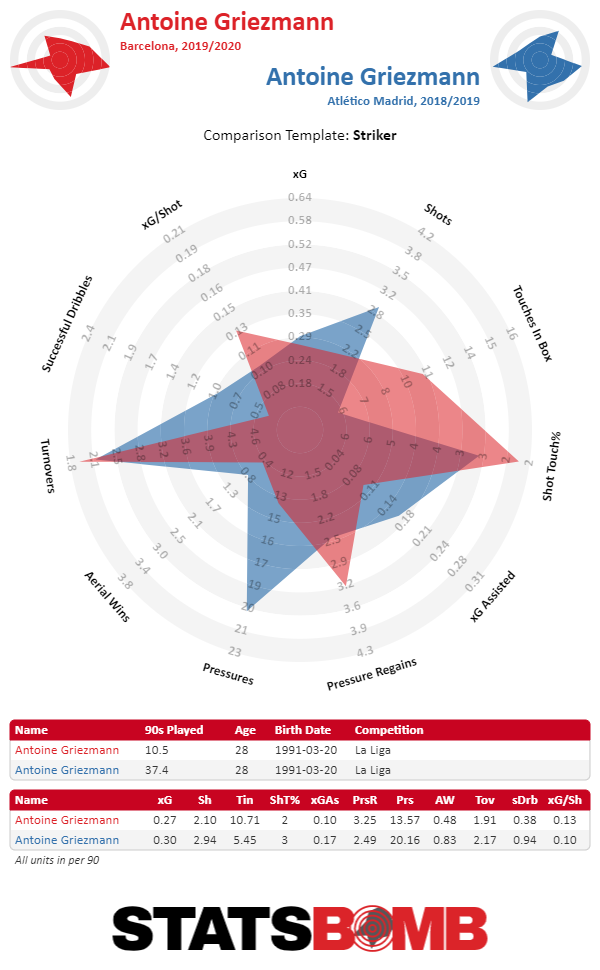

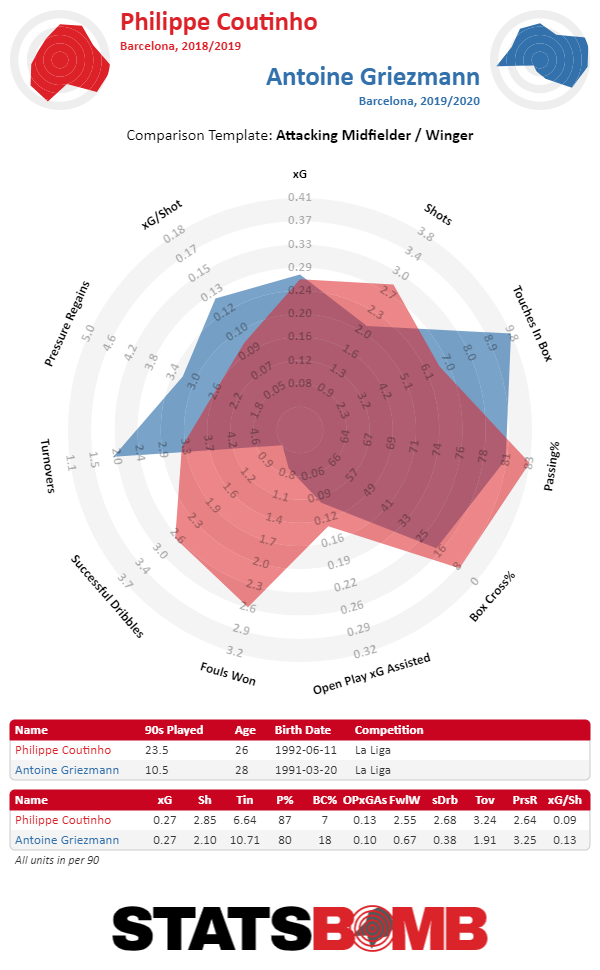

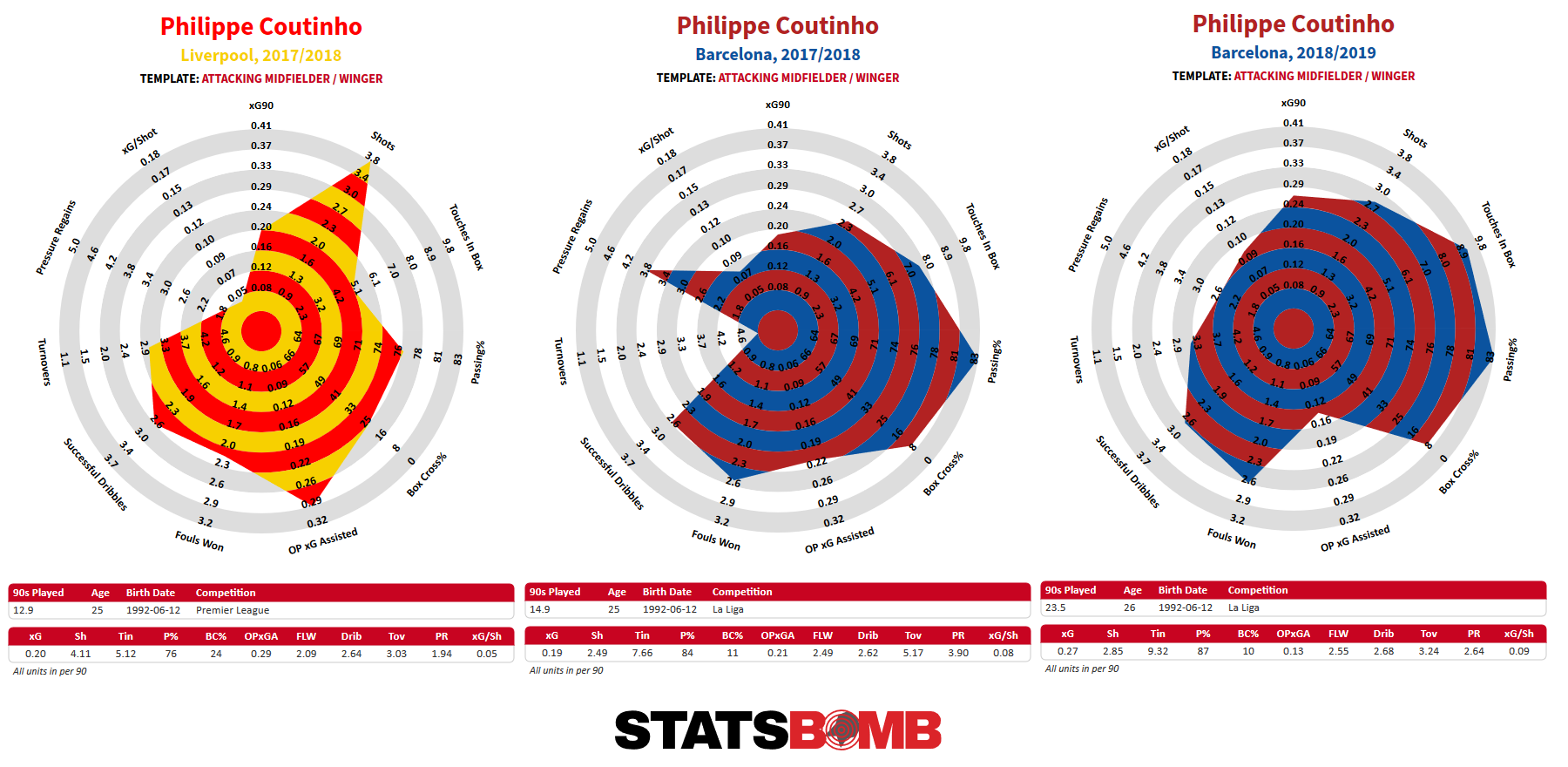

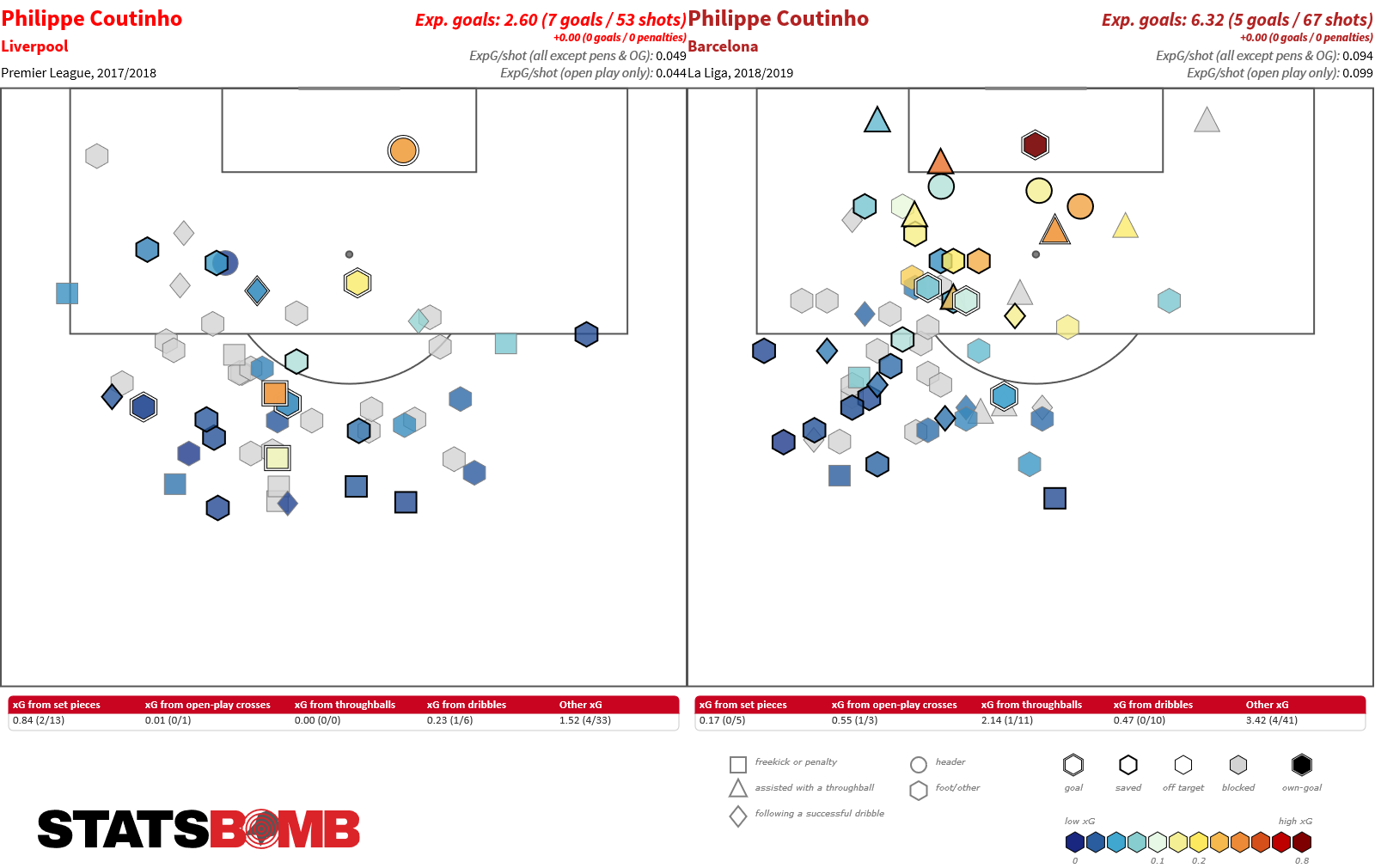

Antoine Griezmann's start to life at Barcelona has not gone entirely as planned. The questions surrounding his signing with the Catalan side remain unanswered. They include where he would fit into the team: “Good question,” he responded when asked recently about his best position, both avoiding the question and ensuring there would be further analysis of the topic. There were also the lingering bad feelings over his decision to stay at Atlético Madrid the summer before Barcelona eventually signed him and, more so, why he documented it in The Decision, a cliff-hanger transfer documentary and the first of its kind. Some Barcelona loyalists said they wouldn’t go to the Camp Nou as long as he was in the team. Griezmann, therefore, is fighting a tactical battle, a dressing room that hasn’t exactly opened their arms to him and a suspicious fanbase. Rocky as his start might have been, as Gerard Piqué pointed out, Barcelona are leading the league and winning their Champions League group while adjusting to a couple of new players in key positions. Frenkie de Jong has replaced the previously ever-present Ivan Rakitić while Griezmann has slotted in to replace Philippe Coutinho. That’s two brand-new players on the left-hand side of the field. De Jong has been, at times, very good, but it's taking him a number of games to find his place in the team. While he doesn’t have the baggage Griezmann does, he also doesn't have the experience. Meanwhile, Griezmann has been shunted out to the left when Lionel Messi and Luis Suárez are healthy, where players tend to become the third wheel, marginalized by the flourishing and productive relationship Messi has with fulback Jordi Alba. Being a supporting conduit isn’t Griezmann's strong point. While there are opportunities to drift inside onto his right and shoot or create, he is very left-footed. StatsBomb’s bespoke left-right footedness metric has him behind just Clement Lenglet in how much he uses his left foot (78%). If he can avoid using his right, he will, which isn’t ideal for a position where he is supposed to cut inside and cause havoc. Philippe Coutinho, the man he replaced, suffered a similar fate on the left, and was marginalized despite not having to deal with the awkwardness of preferring his left foot; he simply never found a way to add to the already excellent Alba-and-Messi-controlled territory. But this season Barcelona are suffering from a more general problem on the left-hand side of the field. It’s just being blamed on the new guy. Jordi Alba has missed six games through injury and rest, Junior Firpo, another summer signing (albeit much cheaper than Griezmann), has failed to convince Ernesto Valverde, and Nelson Semedo has been transplanted to the left from his natural position at right-back (and looked good in the process). Messi naturally turns and looks to his left where Jordi Alba used to be while Griezmann has to fight his every instinct to run toward Messi or into the box where Luis Suárez is busy scheming. Alba, on the other hand, runs away from Messi, waiting for the ball to drop onto his big toe. Ansu Fati does the same but is too young to consistently play this role and Ousmane Dembélé is more comfortable on the right. Valverde has often opted for width at home and left Griezmann on the bench in place of the speedier, width-providing wingers. Alba has been fine this season when fit, and his number of pressures have improved, which should help remedy Barcelona’s stuttering attack provided he can get and stay healthy.  As Alba and Messi return to the same page, the question becomes whether Griezmann will join them. The relationship seems off to an unsure start. While the Frenchman has befriended Suárez—the pair organised Diego Godín’s wedding—he has yet to demonstrate a bond off the field with the beating heart off Barcelona. The rumours haven’t been helped by clumsy explanations as to how it’s progressing. You’d think, in such a highly-experienced dressing room, they would kill the speculation with some ready-made lines to release to the press. Defender Clément Lenglet never got that memo. “They’re getting to know each other little by little,” he said. In terms of linking up on the field, they haven’t set the world on fire either, although Lenglet had an explanation for that too. “All of us need to understand how changing position has affected his game—he has evolved at Barça and has taken on other roles—including playing wide on the wing,” he said. That said, there have only been five passes from Griezmann to Messi inside the box; of the twelve total, three of those went backwards. It’s safe to say the hymns both men are singing are very different so far.

As Alba and Messi return to the same page, the question becomes whether Griezmann will join them. The relationship seems off to an unsure start. While the Frenchman has befriended Suárez—the pair organised Diego Godín’s wedding—he has yet to demonstrate a bond off the field with the beating heart off Barcelona. The rumours haven’t been helped by clumsy explanations as to how it’s progressing. You’d think, in such a highly-experienced dressing room, they would kill the speculation with some ready-made lines to release to the press. Defender Clément Lenglet never got that memo. “They’re getting to know each other little by little,” he said. In terms of linking up on the field, they haven’t set the world on fire either, although Lenglet had an explanation for that too. “All of us need to understand how changing position has affected his game—he has evolved at Barça and has taken on other roles—including playing wide on the wing,” he said. That said, there have only been five passes from Griezmann to Messi inside the box; of the twelve total, three of those went backwards. It’s safe to say the hymns both men are singing are very different so far.  You don't spend five years in a Diego Simeone team without becoming a diligent defender. Even if it's not something you completely buy into, you tend to pick up its importance through osmosis. Griezmann’s pressures and regains are amongst the best in the Barcelona team. Fans of the club will argue that they didn’t sign Griezmann to defend, but it does serve a purpose, and will give Alba much more freedom to venture forward when he eventually hits his stride again. This should endear Griezmann to Messi further; if it means Griezmann sacrificing his best play to let Alba raid, he will likely oblige given what we have seen so far. His 3.25 pressure regains is the highest for anyone in the team who has played at least 600 minutes this season. His 1.24 counterpressures is amongst the best in the team too with just Sergio Busquets, De Jong and Sergi Roberto ahead of him. Much of the problem is that at Atlético Madrid he almost always started on the right or in the centre. His deep progressions are as low as they’ve ever been on the right and his successful dribbles are not very positive either—a sign of a loss in confidence, perhaps, or not fully knowing his confines on the left. Griezmann is pressing more at Barcelona with less success. He has more touches inside the box, which makes sense given Barcelona’s propensity to dominate possession but his shots are down too, a consequence of playing with shot-hogs Messi and Suárez.

You don't spend five years in a Diego Simeone team without becoming a diligent defender. Even if it's not something you completely buy into, you tend to pick up its importance through osmosis. Griezmann’s pressures and regains are amongst the best in the Barcelona team. Fans of the club will argue that they didn’t sign Griezmann to defend, but it does serve a purpose, and will give Alba much more freedom to venture forward when he eventually hits his stride again. This should endear Griezmann to Messi further; if it means Griezmann sacrificing his best play to let Alba raid, he will likely oblige given what we have seen so far. His 3.25 pressure regains is the highest for anyone in the team who has played at least 600 minutes this season. His 1.24 counterpressures is amongst the best in the team too with just Sergio Busquets, De Jong and Sergi Roberto ahead of him. Much of the problem is that at Atlético Madrid he almost always started on the right or in the centre. His deep progressions are as low as they’ve ever been on the right and his successful dribbles are not very positive either—a sign of a loss in confidence, perhaps, or not fully knowing his confines on the left. Griezmann is pressing more at Barcelona with less success. He has more touches inside the box, which makes sense given Barcelona’s propensity to dominate possession but his shots are down too, a consequence of playing with shot-hogs Messi and Suárez.  He is also not dribbling as much as he did at Atlético and is putting up nowhere close to the numbers Coutinho was clocking with the ball at his feet either.

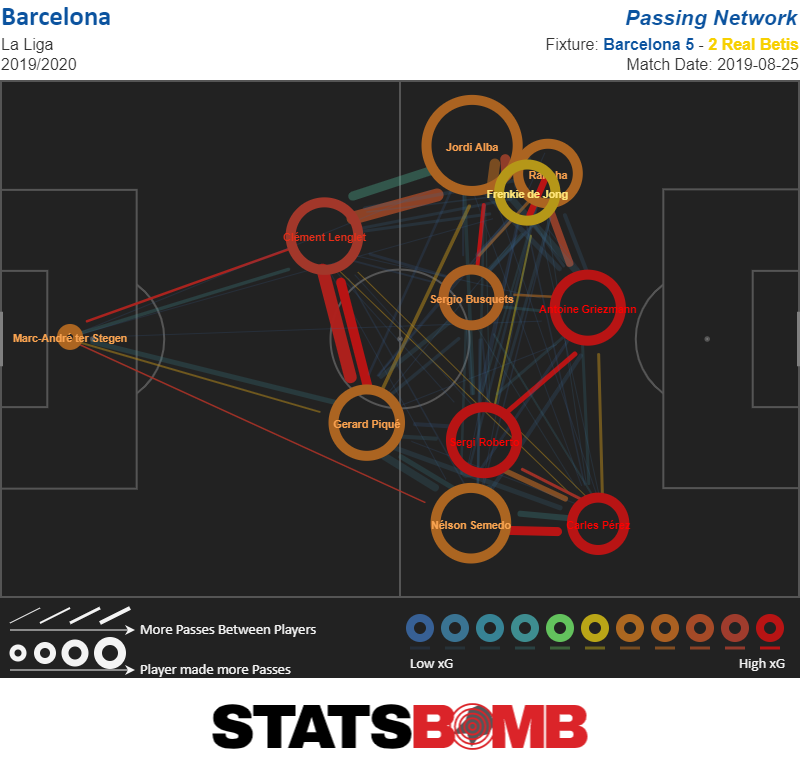

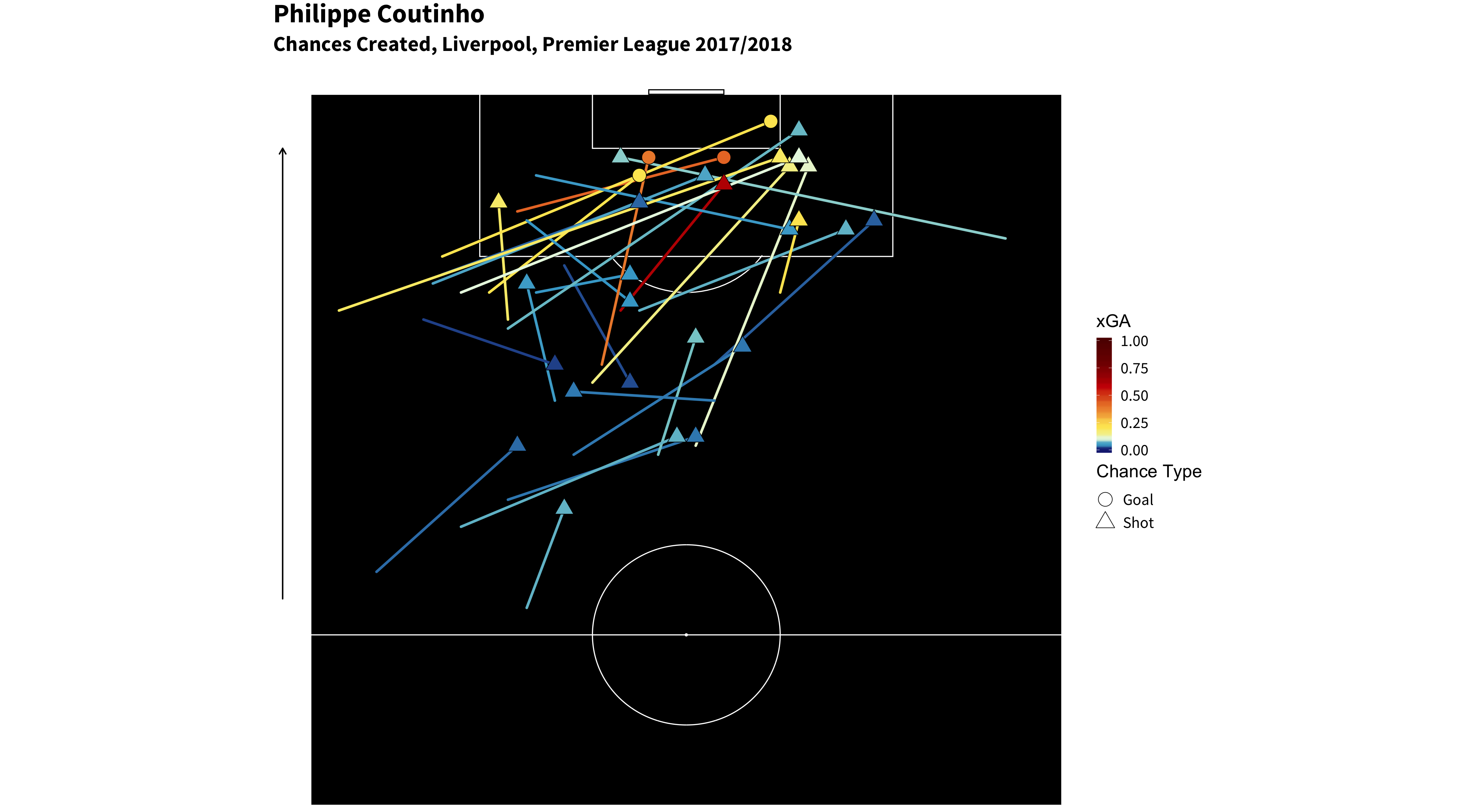

He is also not dribbling as much as he did at Atlético and is putting up nowhere close to the numbers Coutinho was clocking with the ball at his feet either.  In terms of expected goals, Griezmann has been forced to work off scraps compared to Messi and Suárez, who shoot in bulk for Barcelona. His best performance by a distance came against Real Betis when he scored twice and assisted one in a 5-2 win. He was the centre of attention that night as the only striker and had the Camp Nou faithful on their feet. Rafinha and Carles Pérez played out wide and fed Griezmann, which suited him perfectly.

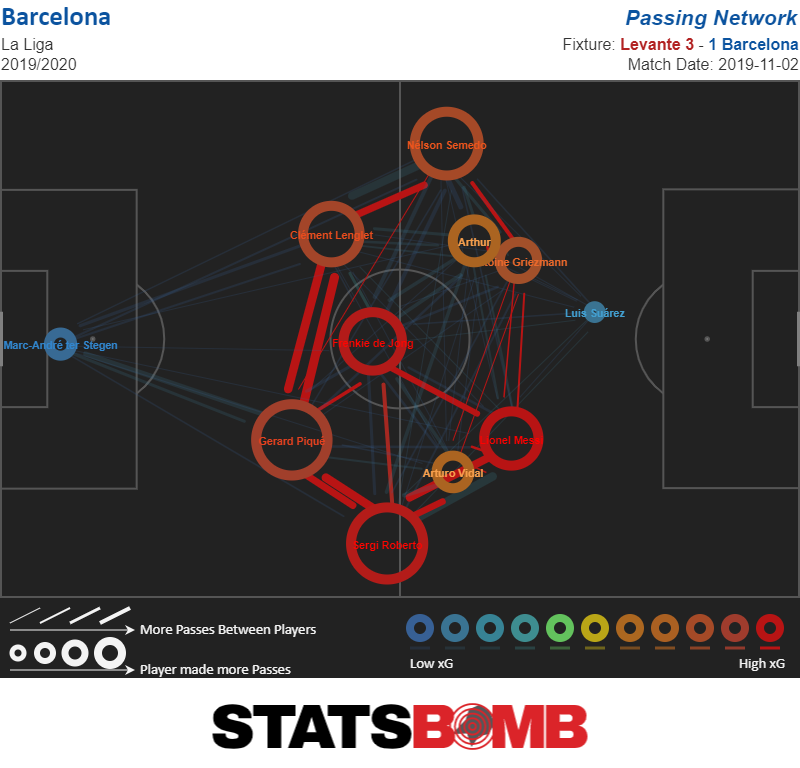

In terms of expected goals, Griezmann has been forced to work off scraps compared to Messi and Suárez, who shoot in bulk for Barcelona. His best performance by a distance came against Real Betis when he scored twice and assisted one in a 5-2 win. He was the centre of attention that night as the only striker and had the Camp Nou faithful on their feet. Rafinha and Carles Pérez played out wide and fed Griezmann, which suited him perfectly.  Compare that to, for example, the Levante game, when he was in on top of Suárez and had very little connection with him—or Messi, for that matter.

Compare that to, for example, the Levante game, when he was in on top of Suárez and had very little connection with him—or Messi, for that matter.  The big question in the coming weeks is whether Griezmann can adapt to his role on the left and if he can’t, whether Ernesto Valverde is willing to change his position. His former agent, Erik Olhats, says he believes Griezmann was “sold a project that he isn’t seeing” and that he is no longer the focal point of the attack, which he has to accept and get used to. Griezmann said he wanted to dine at the same table as Messi a few years ago when he was still playing at Atlético Madrid. By playing on the same team as the Argentine, he is now invited to every meal. It’s not easy stepping into an unfamiliar and relatively hostile environment with Messi waiting for you to prove you’re good enough, but Griezmann can’t say he wasn’t warned about this before he decided to join Barcelona.

The big question in the coming weeks is whether Griezmann can adapt to his role on the left and if he can’t, whether Ernesto Valverde is willing to change his position. His former agent, Erik Olhats, says he believes Griezmann was “sold a project that he isn’t seeing” and that he is no longer the focal point of the attack, which he has to accept and get used to. Griezmann said he wanted to dine at the same table as Messi a few years ago when he was still playing at Atlético Madrid. By playing on the same team as the Argentine, he is now invited to every meal. It’s not easy stepping into an unfamiliar and relatively hostile environment with Messi waiting for you to prove you’re good enough, but Griezmann can’t say he wasn’t warned about this before he decided to join Barcelona.

Tag: Player Analysis

Fede Valverde has revitalized Real Madrid's midfield

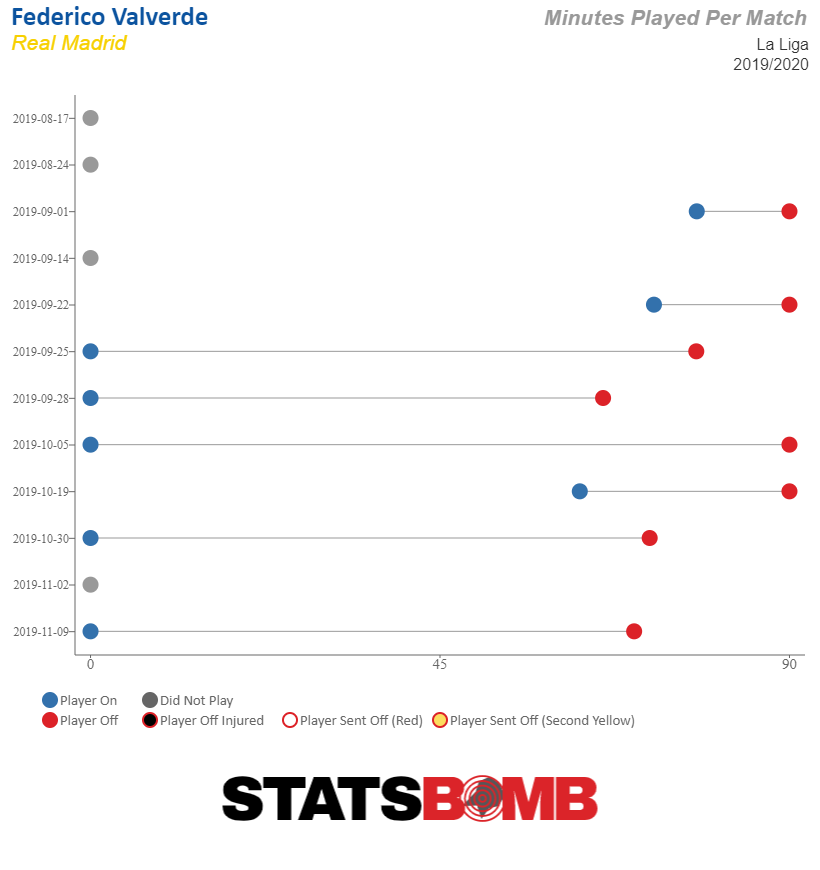

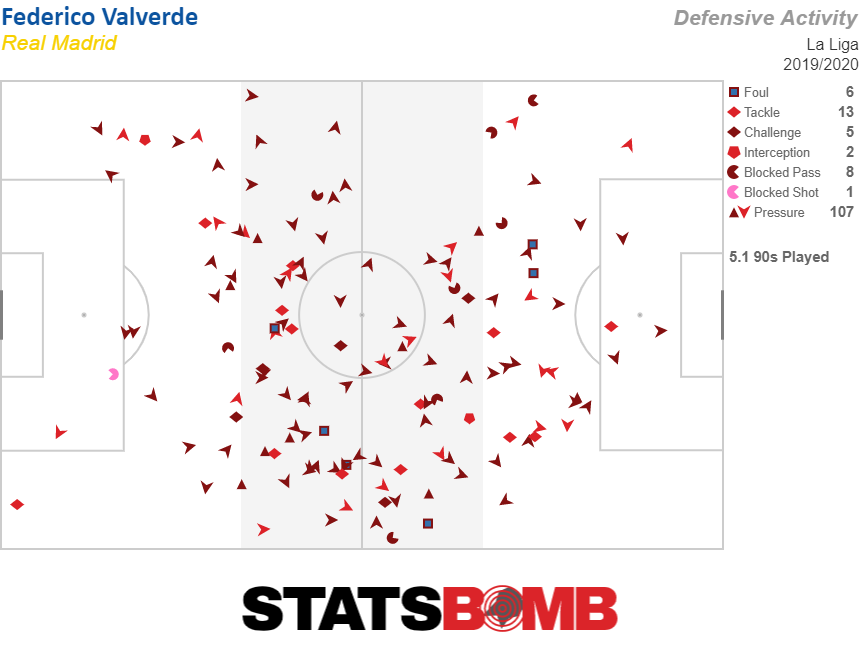

The war dragged on all summer, the fighting waged on many fronts. Zinedine Zidane found himself in the trenches against his own club, Real Madrid, insisting he needed an energetic midfielder that could play a box-to-box role. Up north, Paul Pogba was drawing battle lines at Manchester United in search of a way out, dropping hints with the subtlety of a sledgehammer. Mino Raiola, Pogba’s agent, fought with his words: "Everyone within the club from the manager to the owner knows Paul’s wishes," he said. But for the first time in a long time, Real Madrid didn’t get what they wanted. The pressure on United wasn’t enough, and Pogba stayed put. Meanwhile in Madrid, Fede Valverde toiled under the baking summer sun, just waiting for a chance. The season didn’t start as planned and they found themselves humiliated against Paris Saint Germain in the Champions League and overrun on a number of occasions — Madrid’s defence and midfield was likened to a sieve. Zidane’s second coming at the club looked like it was going to be short as José Mourinho readied his own return speech and the eulogies were written for the Frenchman. Desperation, however, is the mother of all innovation. Zidane was forced into giving the Uruguayan the chance he was seeking. "I just feel like another player in the squad," Valverde said after the Eibar game at the weekend when asked if he felt like he was Real Madrid’s best signing of the summer. "They have given me confidence and I feel like I did when I arrived . . . like Fede Valverde.” He might feel like just another player, but he has been a revelation this season, the solution to Madrid’s midfield malaise. One of the first things Zidane noticed when he returned to the club at the tail end of last season was that the engine room, which had driven much of the team's success during his first spell, was stale and tired. Modrić had come back from the World Cup after dragging Croatia to the final and was a shadow of the player who had been directing things in midfield for the club for years. His midfield partner, Toni Kroos, was once referred to as a “diesel tractor” by his former manager Bernd Schuster. The German is essentially useless without a line breaker beside him and Casemiro, behind them, could only carry so much water. And so Zidane decided to try Valverde in the box-to-box role. The 21-year-old has been phenomenal ever since. Of the last seven games, Valverde didn't start against Mallorca, where Real Madrid lost, or Real Betis, a game which Real Madrid drew.  Since Valverde has come in, the only other player with at least 300 minutes who has more pressures is Lucas Vázquez, who has carved out a specialty for himself and a steady supply of minutes in the team as the hard-tackling winger.

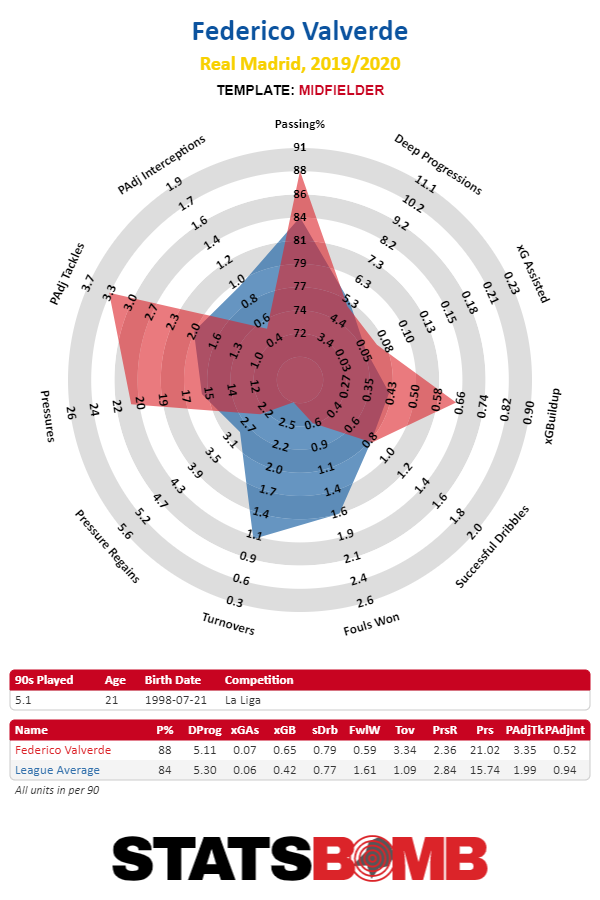

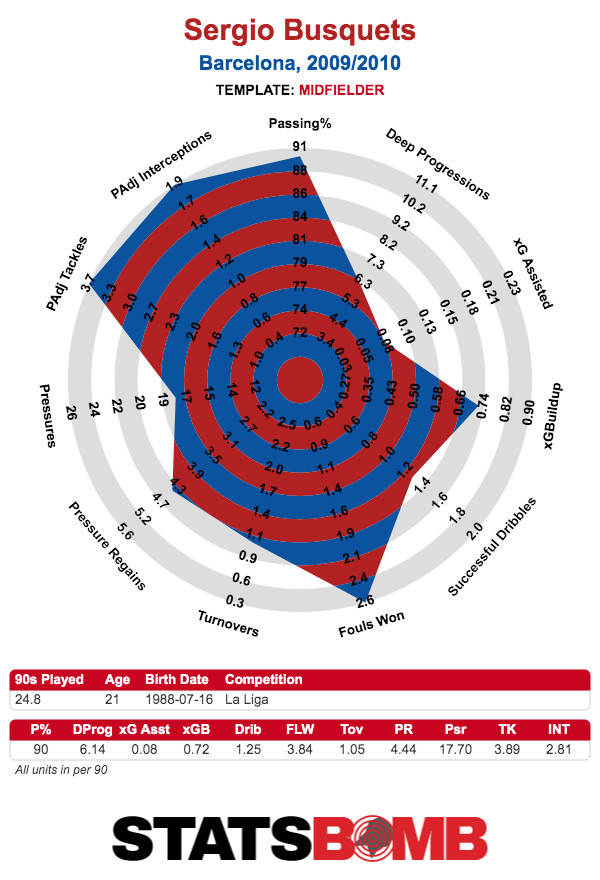

Since Valverde has come in, the only other player with at least 300 minutes who has more pressures is Lucas Vázquez, who has carved out a specialty for himself and a steady supply of minutes in the team as the hard-tackling winger.  Before Zidane slotted Valverde in, Real Madrid simply weren't exerting any pressure. This made life more difficult on the midfield and attack and almost impossible for Thibaut Courtois. He came under criticism for conceding eight goals in his first four league games of the season. Real Madrid were still picking up results but their form was unsustainable. With the chance he's been given, Valverde has 24.76 aggressive actions per 90 minutes, ensuring teams are once again on the back-foot when they face Real Madrid. Their game truly started to change against Osasuna, Valverde's first start of the season. Real Madrid dominated throughout. During that game, Valverde had 17 pressures, which was third behind Casemiro and Lucas Vázquez. His midfield radar shows not only his pressures, but his PAdj Tackles is far higher than the league average too. He's also involved in the team's build-up play.

Before Zidane slotted Valverde in, Real Madrid simply weren't exerting any pressure. This made life more difficult on the midfield and attack and almost impossible for Thibaut Courtois. He came under criticism for conceding eight goals in his first four league games of the season. Real Madrid were still picking up results but their form was unsustainable. With the chance he's been given, Valverde has 24.76 aggressive actions per 90 minutes, ensuring teams are once again on the back-foot when they face Real Madrid. Their game truly started to change against Osasuna, Valverde's first start of the season. Real Madrid dominated throughout. During that game, Valverde had 17 pressures, which was third behind Casemiro and Lucas Vázquez. His midfield radar shows not only his pressures, but his PAdj Tackles is far higher than the league average too. He's also involved in the team's build-up play.  "The best thing I have is my vision and the rhythm to play the ball," he told Real Madrid TV recently. "And always with the desire to run and arrive in both areas in order to defend and attack. You could say I am a little hot-blooded on the field.” So, basically he offers everything. Everything that Zidane needed. There's no doubt that Zidane knew he would be good, but he wasn’t sure if he could be the player he desperately needed. The Real Madrid manager wasn’t going to put his future on the line for an untested youngster. But when Donny Van Der Beek became available, Zidane held firm; it was either Pogba or nobody. In the end, nobody may have been the best thing to happen to the team.

"The best thing I have is my vision and the rhythm to play the ball," he told Real Madrid TV recently. "And always with the desire to run and arrive in both areas in order to defend and attack. You could say I am a little hot-blooded on the field.” So, basically he offers everything. Everything that Zidane needed. There's no doubt that Zidane knew he would be good, but he wasn’t sure if he could be the player he desperately needed. The Real Madrid manager wasn’t going to put his future on the line for an untested youngster. But when Donny Van Der Beek became available, Zidane held firm; it was either Pogba or nobody. In the end, nobody may have been the best thing to happen to the team.

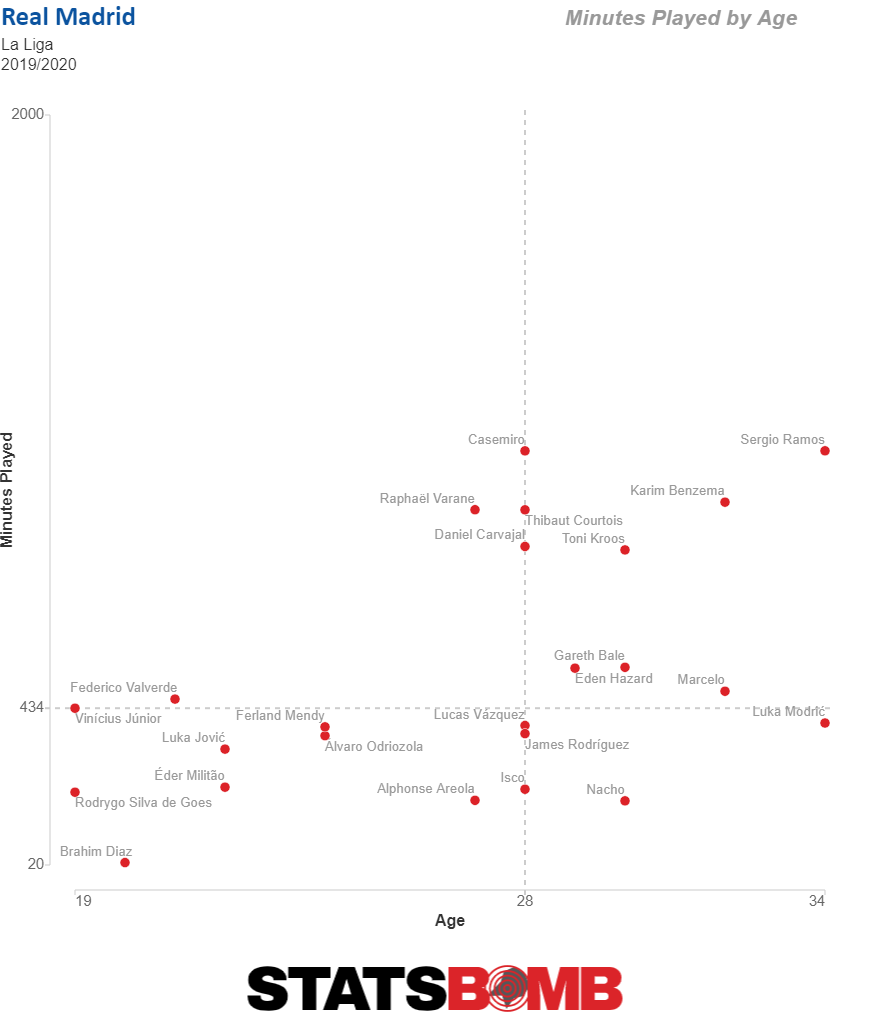

Changing Real Madrid's ageing side

Real Madrid have been trying to find replacements for their ageing players for a couple of years now. The signings of Marco Asensio from Mallorca, Dani Ceballos from Real Betis, Vinicius from Flamengo and Rodrygo from Santos respectively have certainly been welcome additions to the squad. But, as is normal for a highly successful team, breaking into the starting XI has proven difficult for the newcomers.  None of their bright young stars had done so until Valverde came along, followed quickly by Rodrygo, who continues to impress. Yet the Brazilian doesn't necessarily change the way the team play, but is simply a replacement for Gareth Bale. Dani Ceballos couldn't find a role for himself and left for Arsenal, Alvaro Odriozola hasn't been able to supplant Dani Carvajal at right-back or even compete for minutes at the position. Vinicius' decent run last year looks to be finished as a loan deal in January becomes a possibility. Sergio Reguilon is on loan to Sevilla and Eder Militao is still finding his feet. Meanwhile, Brahim is linked again with a loan deal as he fails to make an impact and Luka Jović has scored just once all season. Aside from Eden Hazard replacing Cristiano Ronaldo and Rodrygo just now taking Bale's place, the back four and midfield for Real Madrid have looked too familiar for too long. Valverde, on the other hand, nicknamed "El Pajarito" or 'The Little Bird' because he used to fly around the field when he was younger, changes everything. He creates spaces in the opposition penalty area with his driving runs and puts pressure on defenders with his leggy pressing. He helps out at the back and frees up Casemiro at the base of midfield, where previously he was swamped time and time again. Valverde's emergence also means the need for Casemiro to be a box-to-box midfielder with attacking intent as well as a defensive, holding midfielder is gone. “Every time I pick him, he plays well,” said Zidane after another excellent performance against Eibar, possibly Valverde's best yet. “He was just missing the goal and he got that so I’m delighted for him and for Madrid.” If he keeps up his current form and can add a consistent threat in front of goal, the Little Bird will continue to soar.

None of their bright young stars had done so until Valverde came along, followed quickly by Rodrygo, who continues to impress. Yet the Brazilian doesn't necessarily change the way the team play, but is simply a replacement for Gareth Bale. Dani Ceballos couldn't find a role for himself and left for Arsenal, Alvaro Odriozola hasn't been able to supplant Dani Carvajal at right-back or even compete for minutes at the position. Vinicius' decent run last year looks to be finished as a loan deal in January becomes a possibility. Sergio Reguilon is on loan to Sevilla and Eder Militao is still finding his feet. Meanwhile, Brahim is linked again with a loan deal as he fails to make an impact and Luka Jović has scored just once all season. Aside from Eden Hazard replacing Cristiano Ronaldo and Rodrygo just now taking Bale's place, the back four and midfield for Real Madrid have looked too familiar for too long. Valverde, on the other hand, nicknamed "El Pajarito" or 'The Little Bird' because he used to fly around the field when he was younger, changes everything. He creates spaces in the opposition penalty area with his driving runs and puts pressure on defenders with his leggy pressing. He helps out at the back and frees up Casemiro at the base of midfield, where previously he was swamped time and time again. Valverde's emergence also means the need for Casemiro to be a box-to-box midfielder with attacking intent as well as a defensive, holding midfielder is gone. “Every time I pick him, he plays well,” said Zidane after another excellent performance against Eibar, possibly Valverde's best yet. “He was just missing the goal and he got that so I’m delighted for him and for Madrid.” If he keeps up his current form and can add a consistent threat in front of goal, the Little Bird will continue to soar.

Statistical Standouts: Four La Liga players who are making waves in the numbers

Here are some La Liga players doing good and/or interesting things so far this season.

Arthur’s Increased Attacking Output

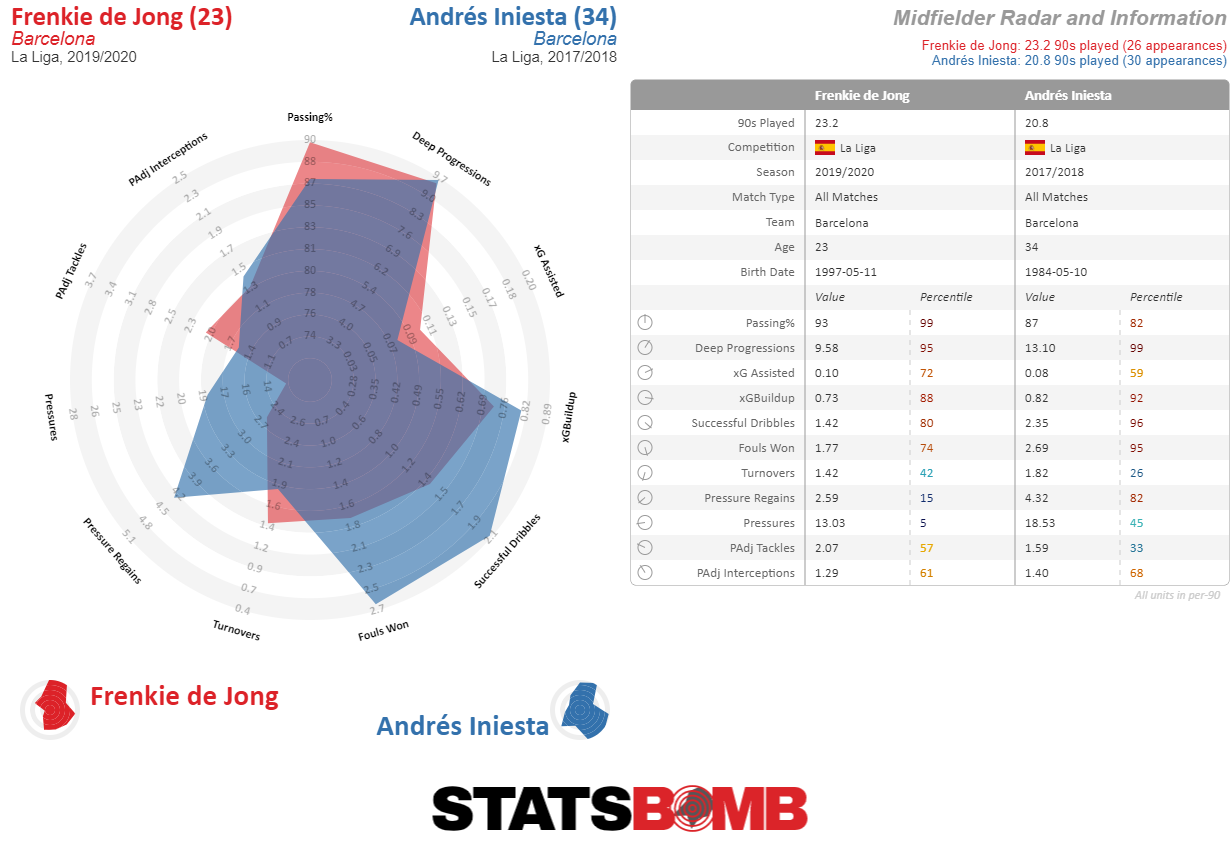

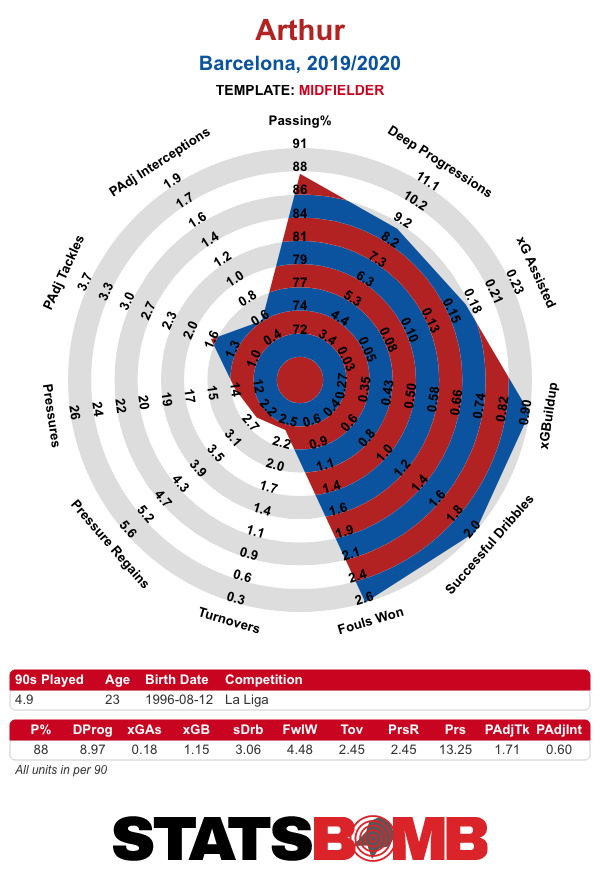

Frenkie de Jong has rightly taken plaudits for his good start at Barcelona (including a standing ovation from the Ipurua crowd in Saturday’s win away at Eibar). Despite a certain degree of awkwardness in set attacking situations, as is probably to be expected at this stage, in more open environments his movement and on and off-ball contributions have impressed.  Another member of the Barcelona midfield has also looked good. Last season, Arthur settled in well following his move from Gremio in Brazil. This time around, he has been set the target of increasing his attacking output by coach Ernesto Valverde. He has responded gamely, scoring his first goals for the club, doubling his through-ball and shot output, increasing his key pass and expected assist numbers, and taking a huge jump forward in terms of successful dribbles.

Another member of the Barcelona midfield has also looked good. Last season, Arthur settled in well following his move from Gremio in Brazil. This time around, he has been set the target of increasing his attacking output by coach Ernesto Valverde. He has responded gamely, scoring his first goals for the club, doubling his through-ball and shot output, increasing his key pass and expected assist numbers, and taking a huge jump forward in terms of successful dribbles.  Not since Andrés Iniesta in 2013/14 (thanks Messi Data Biography!) has a regular Barcelona midfielder completed over three dribbles per match. In an admittedly fairly low sample size that is exactly what Arthur is doing. A small, scampering figure of neat touches and tight turns, he has also carried a 100% success rate through his 15 dribble attempts to date (the most anyone else has completed without fail is Thomas Partey’s eight). Arthur has transitioned from more of a controlling role last season (with more deep progressions and a higher passing success rate) to a more aggressively forward-minded one. The arrival of De Jong has helped balance the midfield to make that possible. They are both very able ball-carriers (for the first time since Xavi and Iniesta’s last season together in 2014-15, Barcelona have a pair of regular midfielders who are both carrying the ball over 300 metres per 90), and while any statistical assessment of their impact is complicated by the fact that two of the four league matches they’ve started together have also been two of the three that Lionel Messi has started, on a subjective level, Barcelona’s best midfield lineup already looks to be the pair of them plus one other as circumstances dictate.

Not since Andrés Iniesta in 2013/14 (thanks Messi Data Biography!) has a regular Barcelona midfielder completed over three dribbles per match. In an admittedly fairly low sample size that is exactly what Arthur is doing. A small, scampering figure of neat touches and tight turns, he has also carried a 100% success rate through his 15 dribble attempts to date (the most anyone else has completed without fail is Thomas Partey’s eight). Arthur has transitioned from more of a controlling role last season (with more deep progressions and a higher passing success rate) to a more aggressively forward-minded one. The arrival of De Jong has helped balance the midfield to make that possible. They are both very able ball-carriers (for the first time since Xavi and Iniesta’s last season together in 2014-15, Barcelona have a pair of regular midfielders who are both carrying the ball over 300 metres per 90), and while any statistical assessment of their impact is complicated by the fact that two of the four league matches they’ve started together have also been two of the three that Lionel Messi has started, on a subjective level, Barcelona’s best midfield lineup already looks to be the pair of them plus one other as circumstances dictate.

Loren Morón’s Scoring Start

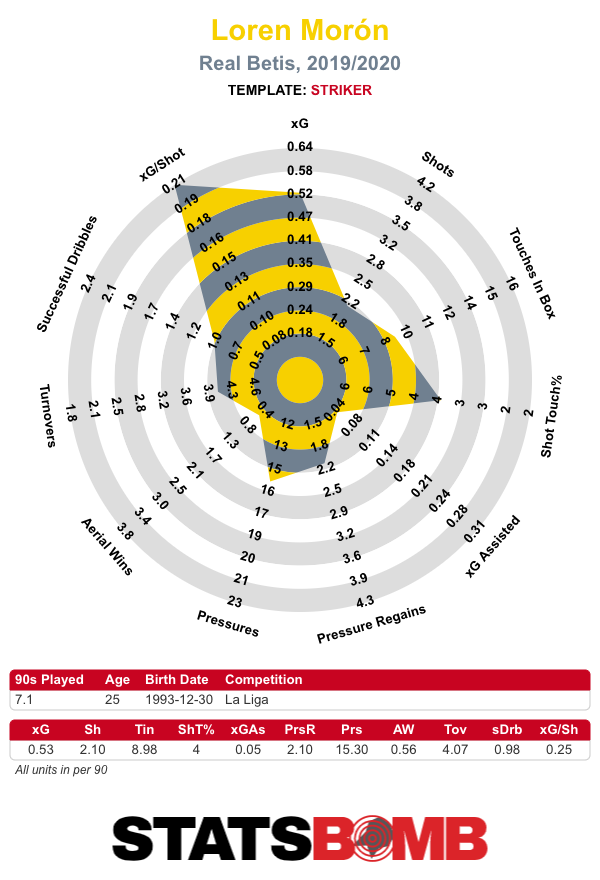

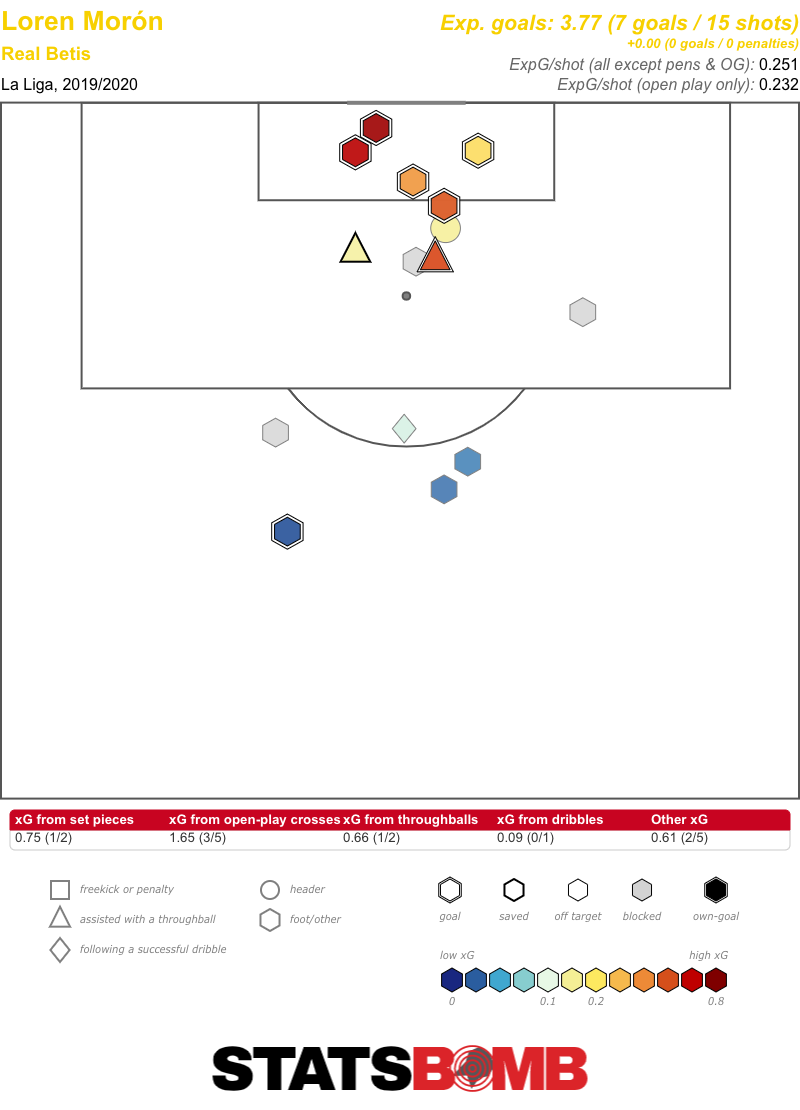

Real Betis have made a disappointing start to the season and are currently down in the relegation zone. Amidst a series of structural and individual issues, one player has nevertheless managed to stand out. Loren Morón is La Liga’s top scorer, with seven goals. There has been a fair degree of over-performance in relation to his expected goals (xG), but even at an underlying level, the 25-year-old is still approximating the output of an elite striker.  Last season, only 12 players in the big five leagues recorded 0.50 or more xG per 90. Most of those were high volume shooters, with only two of them taking less than three shots per 90. Loren is averaging just over two so far, which does place a question mark over the sustainability of his output. In that group, Edinson Cavani has the most similar shot profile, but he plays for a dominant team in his league. Loren has shown himself to be a sharp and decisive presence inside the area, but he is relatively service reliant.

Last season, only 12 players in the big five leagues recorded 0.50 or more xG per 90. Most of those were high volume shooters, with only two of them taking less than three shots per 90. Loren is averaging just over two so far, which does place a question mark over the sustainability of his output. In that group, Edinson Cavani has the most similar shot profile, but he plays for a dominant team in his league. Loren has shown himself to be a sharp and decisive presence inside the area, but he is relatively service reliant.  It is also worth noting that at this stage last season, Loren sat on 0.48 xG per 90. Of the five players in the league who were averaging over 0.50 xG per 90 at that juncture, only one of them maintained it over the course of the entire campaign (although Levante’s Roger Martí came very close, at 0.49 xG per 90). Loren ended up with a seasonal average of 0.34 per 90, a smidgen up from his mark during his first half-season in the first team. Can he sustain his improved top-line and underlying numbers this time around?

It is also worth noting that at this stage last season, Loren sat on 0.48 xG per 90. Of the five players in the league who were averaging over 0.50 xG per 90 at that juncture, only one of them maintained it over the course of the entire campaign (although Levante’s Roger Martí came very close, at 0.49 xG per 90). Loren ended up with a seasonal average of 0.34 per 90, a smidgen up from his mark during his first half-season in the first team. Can he sustain his improved top-line and underlying numbers this time around?

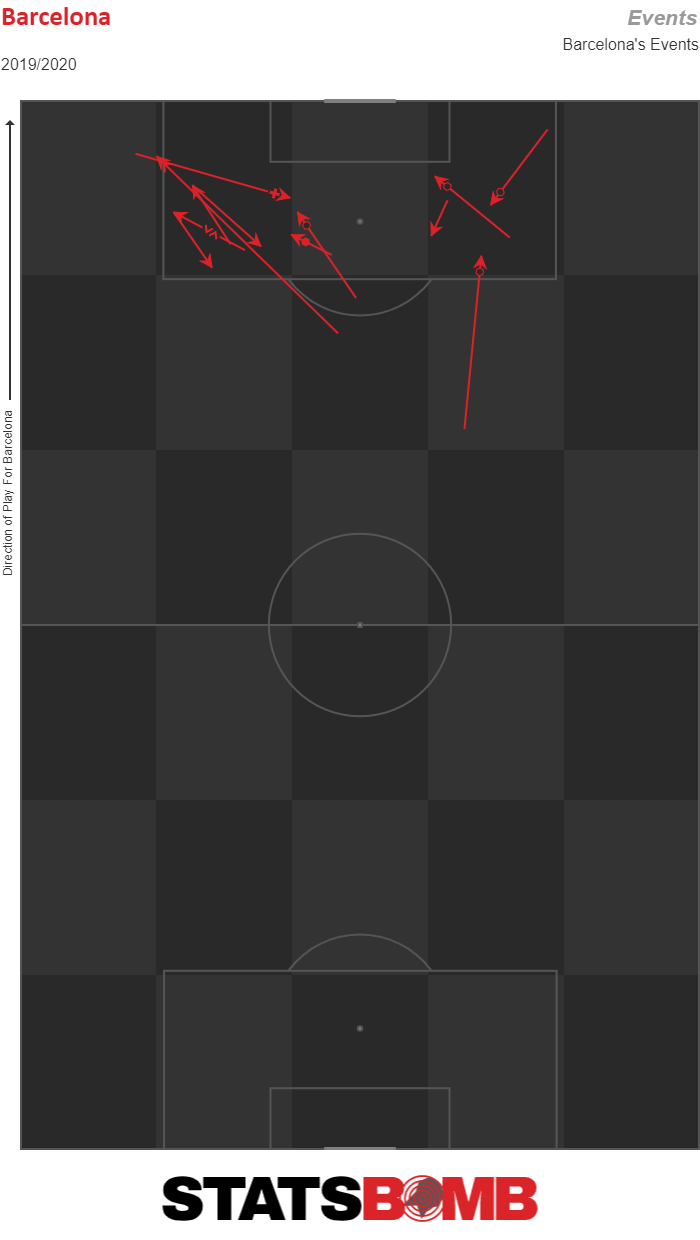

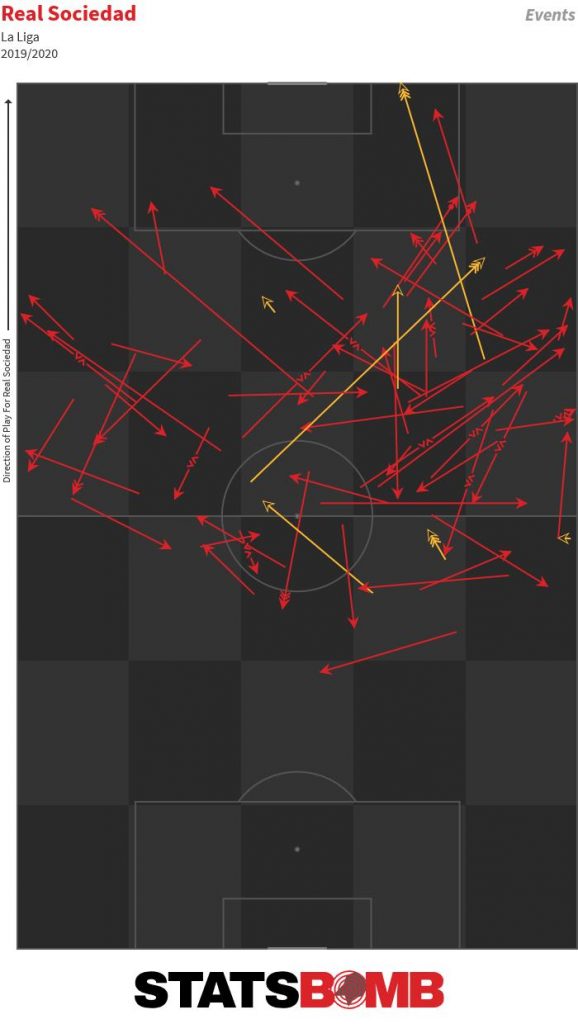

Sergio Reguilón’s Attacking Impact

Sergio Reguilón showed enough in his minutes at Real Madrid last season to suggest that he was, at the very least, a competent top-flight performer with room for further growth. This season, on loan at Sevilla, he’s arguably been the best attacking full-back in La Liga. Sevilla’s system under Julen Lopetegui puts a lot of emphasis on the full-backs to get forward and support the attack, and in Reguilón he has a player who relishes the opportunity to constantly drive forward down the left. He is one of only seven players in La Liga to have carried the ball over 300 metres per 90, while only Samuel Chukwueze and Vinícius Junior have carried the ball at a greater average speed. Reguilón also stands out in just how often he gets forward into positions to shoot or assist. His tally of 3.35 shots and key passes per 90 is far more than that of any other full-back with a reasonable number of minutes, while his 4.77 touches inside the box per 90 is again a clear league high among players in his position. He looks comfortable carrying the ball into central areas, maintaining a good panorama of play and picking out some nice passes at pace. Here are his key passes to date:  Defensively, he looks better on the front foot and does struggle a bit with movement in and around him in more set situations. But that is something that can be refined over time. As it is, in Reguilón and Achraf Hakimi (on loan at Borussia Dortmund), Real Madrid have two young and talented full-backs capable of competing in the first team group next season if space opens up for them to do so.

Defensively, he looks better on the front foot and does struggle a bit with movement in and around him in more set situations. But that is something that can be refined over time. As it is, in Reguilón and Achraf Hakimi (on loan at Borussia Dortmund), Real Madrid have two young and talented full-backs capable of competing in the first team group next season if space opens up for them to do so.

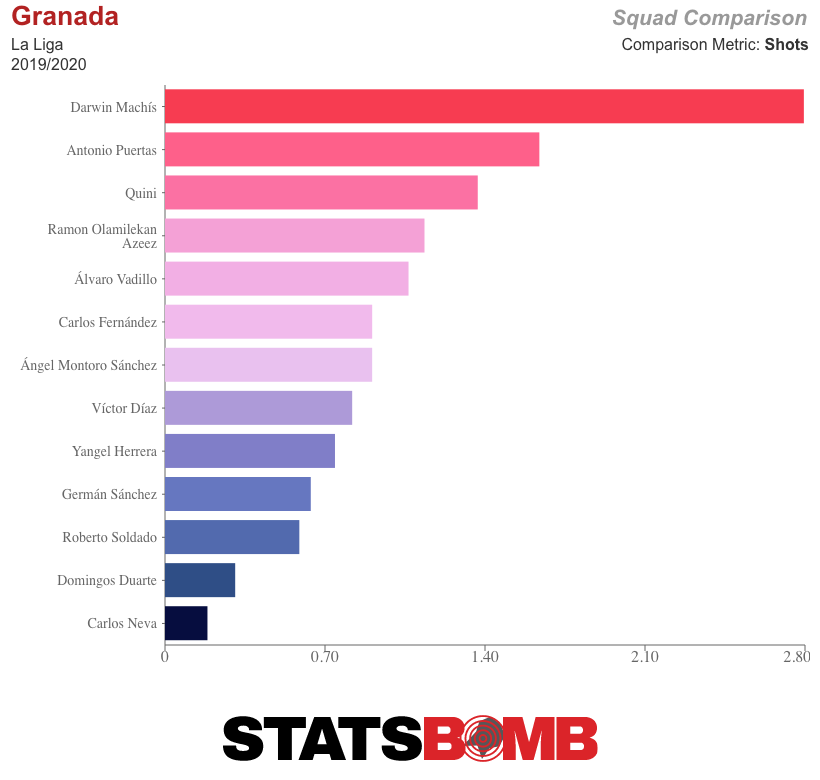

Darwin Machís: Shot Machine

Granada have exceeded all expectations on their return to the top flight. They are up in third, just two points behind leaders Barcelona and with the opportunity to go top, at least for a time, with victory at home to Real Betis on Sunday. Theirs has primarily been a collective triumph, but certain individuals have still shone. Goalkeeper Rui Silva has been a solid and assured presence, while Ángel Montoro has proved to be a key ball-progressor and creative force from both open play and set pieces. But the Granada player with the most interesting statistical profile is probably Darwin Machís. He doesn’t really seem to do anything other than carry, dribble and shoot. He attempts fewer passes than all but one of his teammates, carries the ball further that any of them (at one of the quickest speeds in the division), completes far more dribbles than any of them, and also clearly leads the way in terms of shots per 90.  A league-third-high (amongst players with at least 400 minutes) 4.53% of his total touches to date have been shots. They’ve not exactly been a stellar selection of efforts:

A league-third-high (amongst players with at least 400 minutes) 4.53% of his total touches to date have been shots. They’ve not exactly been a stellar selection of efforts:  But within the context of a team who don't necessarily have the personnel to consistently create good looks in open play, a player capable of advancing upfield and getting off shots can still form a useful part of a wider and more varied game plan.

But within the context of a team who don't necessarily have the personnel to consistently create good looks in open play, a player capable of advancing upfield and getting off shots can still form a useful part of a wider and more varied game plan.

Does Sadio Mané have a shot at winning the Ballon d’Or?

With the 30-man shortlist revealed today, Sadio Mané is among the outsiders to be named the world’s best player this calendar year.

It takes one to know one, they say, so perhaps it made sense that Lionel Messi gave Sadio Mané his first vote for the FIFA World Player of the Year award last month. The Argentine eventually came out top, but if he plans to win the Ballon d’Or as well, he might want to hand his next vote to a less threatening rival.

Mané came fifth for the same award, but perhaps he should have been higher. Since the start of the year he has won the Champions League, helped Liverpool to a 97-point league finish and guided Senegal to the Africa Cup of Nations final, which his country lost 1-0 to Algeria despite leading the shot count 12-1. Arsène Wenger believes Mané should win the award.

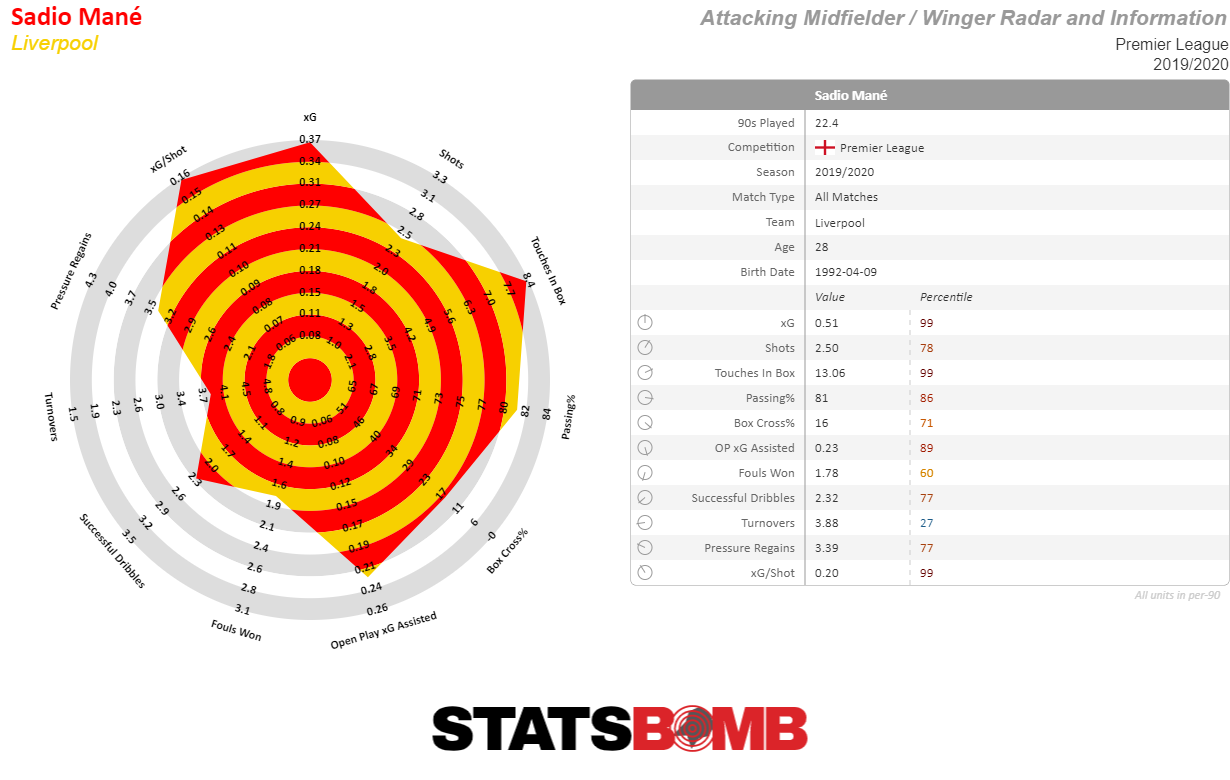

The stats reflect a superb year for Mané so far. He takes few shots but lets rip from excellent positions. His open-play expected assists rate (xA) stands at 0.15 per 90 minutes. His number of pressure regains is solid and on the rise: this season Mané has been the forward with the sixth most pressure regains per 90 in the league (4.01).

Though Mané is a winger, the raids of Andrew Robertson down the left let him move into the box like a striker. Not only does Mané take up positions like a poacher, he finishes like one too.

Along with the achievements of his two teams, do these stats give Mané a shout for the Ballon d’Or? Let’s compare him with the other candidates. Those who came ahead of him for the FIFA award were Messi, Virgil van Dijk, Cristiano Ronaldo and Mohamed Salah. But a couple of the players who came just behind Mané might pose a threat too.

The outsiders

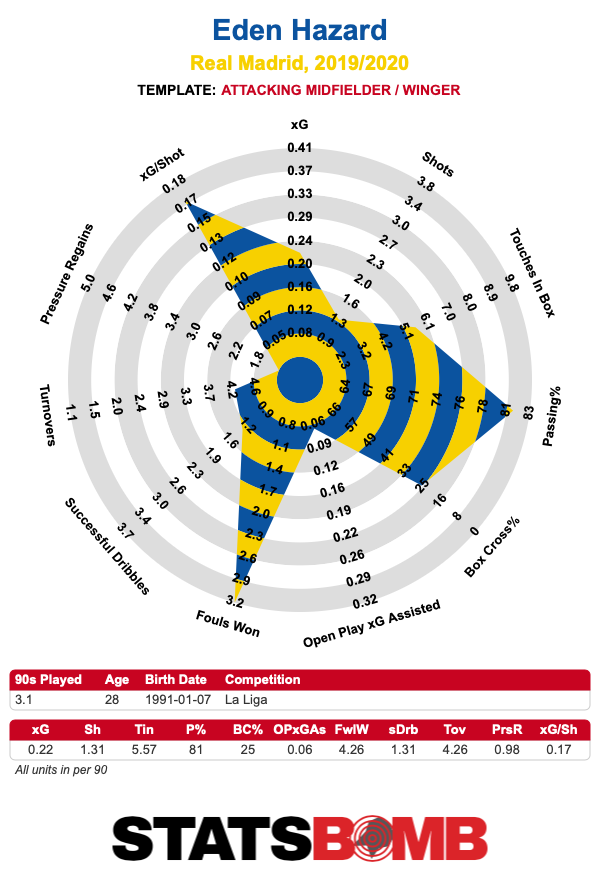

A cluster of three players got just a few votes fewer than Mané. One was Frenkie de Jong, but considering Mané won the Champions League, the Dutch playmaker should have a hard time getting ahead of him. Another was Eden Hazard, yet as good as he was in the Premier League last season, Mané has done more in the cups, and a thigh injury has married the Belgian’s start to life in Spain.

The third is Kylian Mbappé, and here Mané can only beat him on his Africa Cup of Nations displays, the stronger reputation of the Premier League and Paris Saint-Germain’s debacle in the Champions League. As a striker, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Yet collective trophies matter, and so Mané will most likely face a bigger challenge from his two teammates as well as Messi and Cristiano. Let’s begin with fourth place.

The favourites

Just ahead of Mané came Salah, with three votes more. That denotes a close race, yet the stats say Mané should prevail. Whereas Salah takes more shots, Mané selects his attempts better and has a higher expected goals rate (xG) per 90. Most of the other key metrics favour Mané as well: his passing is more accurate, his xA from open play is higher, he loses the ball less often and he presses more efficiently.

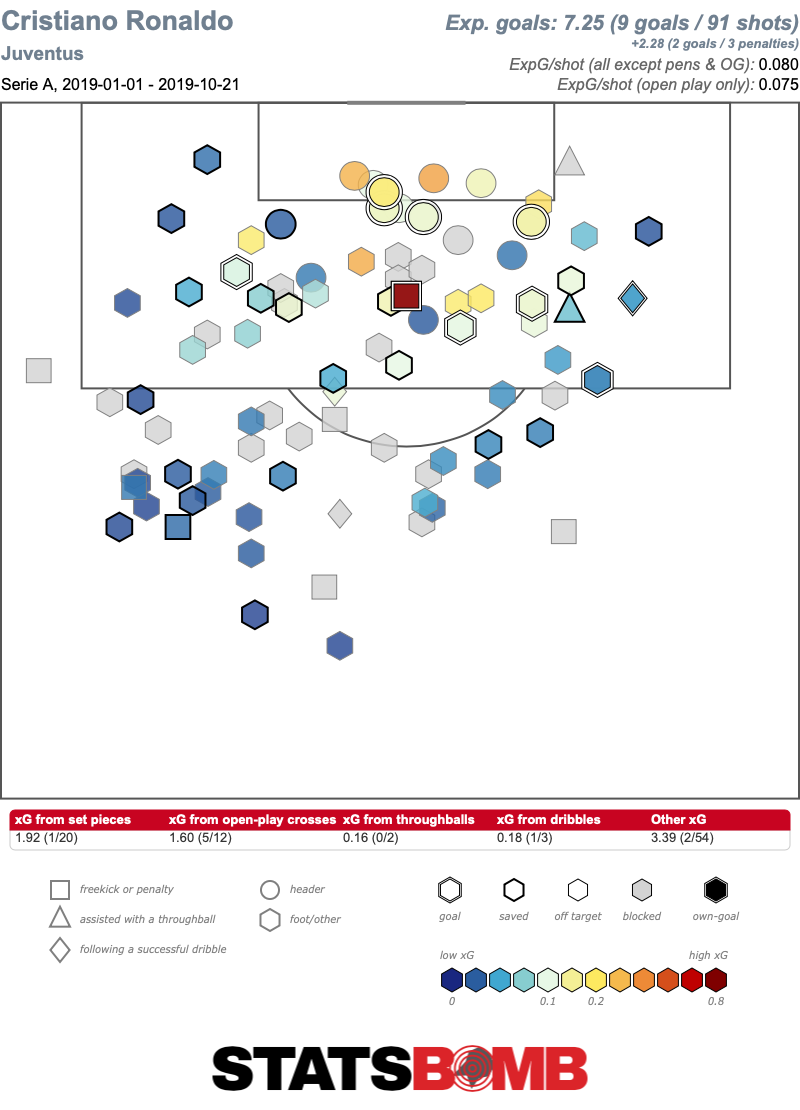

After Salah there’s a big gap up to the top three. Third is Cristiano, and again you can make the argument that Mané has been better. Like Salah, Cristiano beats him on shot volume, but Mané comes out top for expected goal involvements and work rate. (You could argue that Cristiano plays more as a striker, though his radar for that position does him no favours here.)

It is also worth highlighting their finishing. Whereas Mané has scored 19 non-penalty goals from an xG of 11.83, Cristiano has nine non-penalty goals from a slightly lower xG. Cristiano won the UEFA Nations League, but Mané became European club champion. Throw in the Africa Cup of Nations and Mané has a strong case.

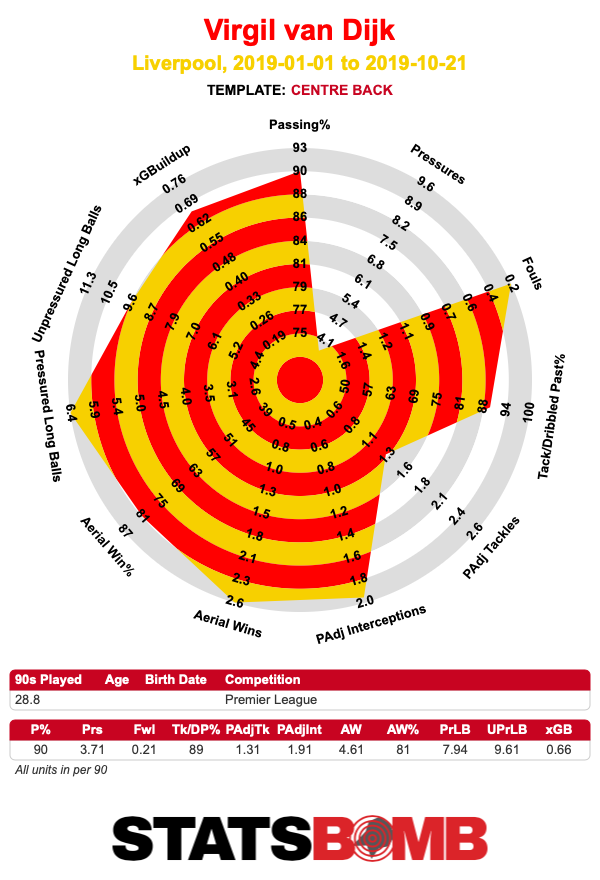

All of which leads us to second place. Here we find Van Dijk, which hands us a tricky comparison between a winger and a centre back. The Dutchman might have the upper hand: he won the UEFA Player of the Year award in late August and, looking at his stats, it is hard to say what more he could have done.

Then comes the king, Messi, who won the FIFA award by a clear margin. Mané has a better shot selection, works harder and loses the ball less often. Beyond that, it’s not really a contest.

But wait. Did Mané not outperform Messi in the Champions League? We remember that Messi supposedly played badly when Barcelona lost 4-0 at Anfield. Do the stats reflect this? Well… no.

The forgotten one

And so while Messi remains Messi, Mané does compare favourably to most of the candidates for the Ballon d’Or.

But have we not forgotten someone?

When the shortlist for the FIFA award came out, Pep Guardiola said he thought no player had had a better season than Bernardo Silva. Yet another City player who got little mention was Raheem Sterling. He was not among the 10 nominees for the award, a call that can only have been based on City’s travails in the Champions League. Compared to Mané, Sterling has been better since the start of the year.

One can only hope Sterling gets more recognition when the Ballon d’Or voting gets underway. Whether he’ll beat Mané is doubtful, however, given the weight the biggest cup titles carry. Mané has been Liverpool’s best attacker this year and, while he’s unlikely to win the Ballon d’Or, a spot among the top three would be well deserved.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

Robert Lewandowski is still the best

Everybody knows that Robert Lewandowski is good. This season, though, he's been way better than good.

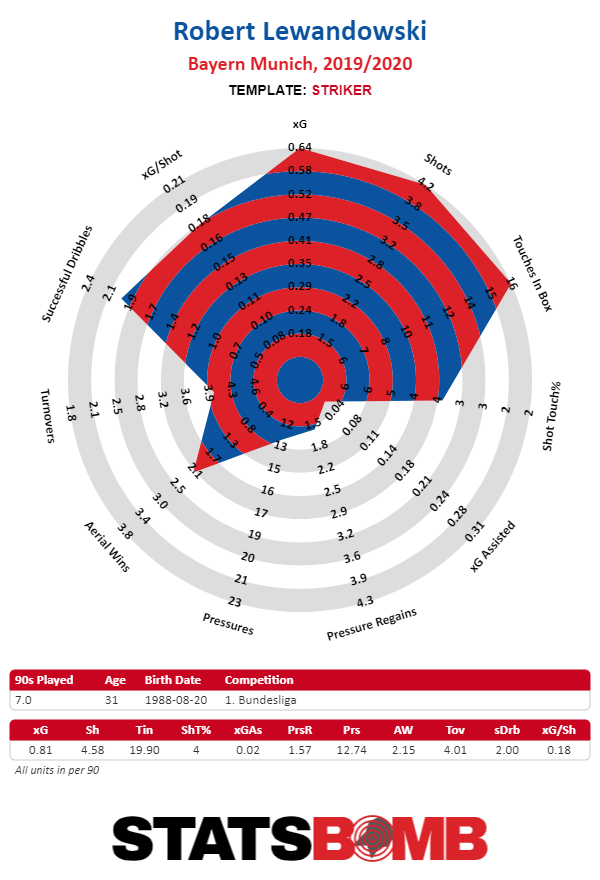

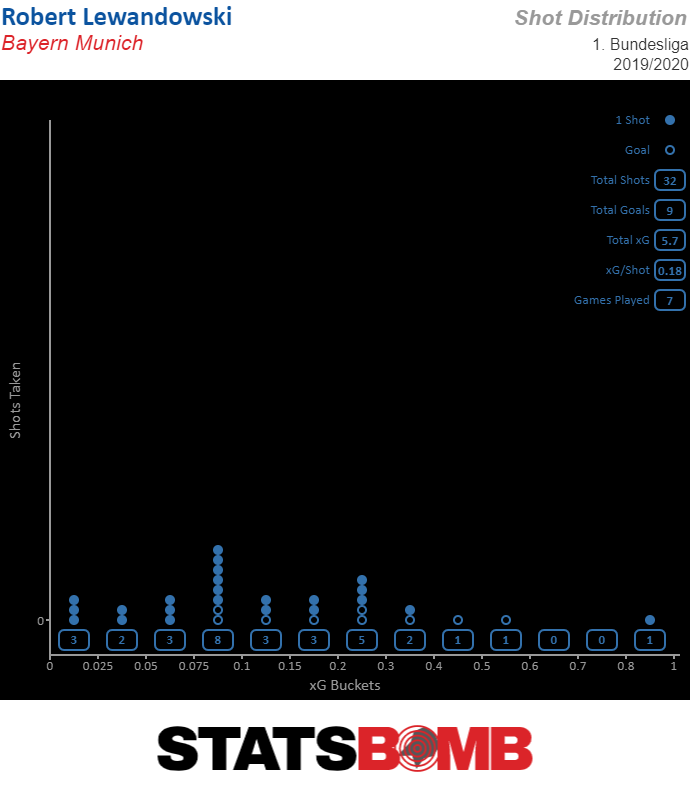

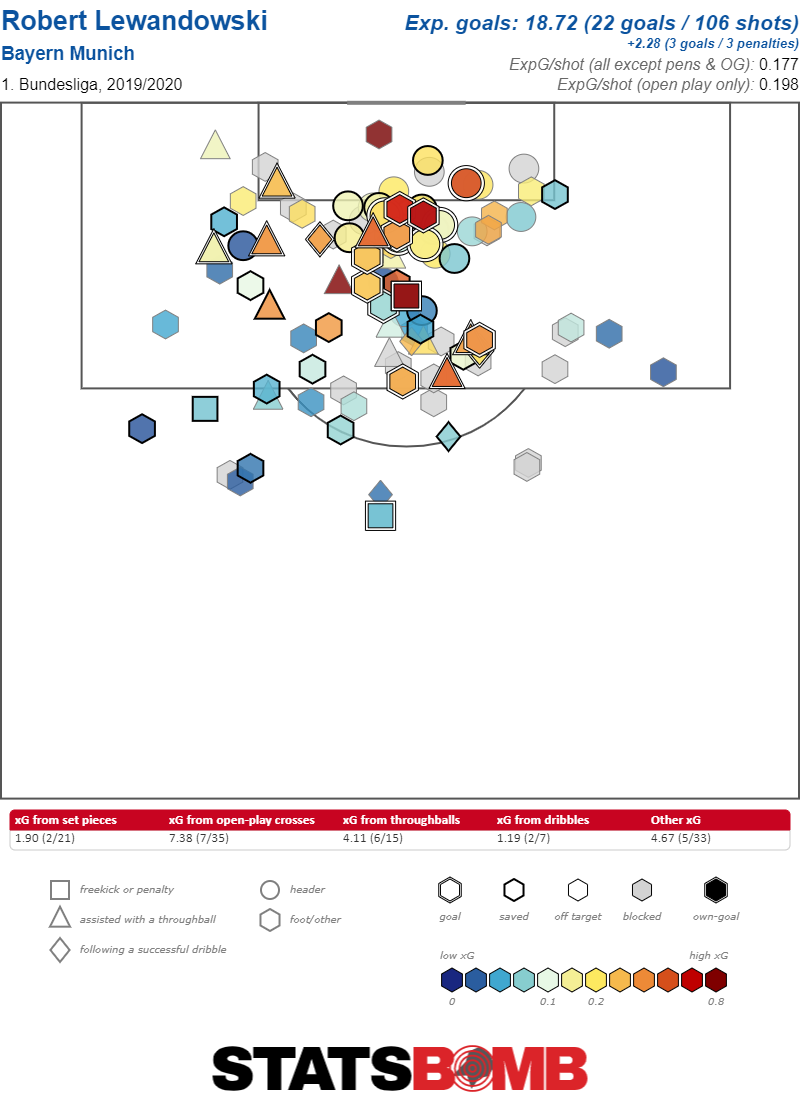

Let's start with the most basic number of all. He's scoring, including penalties, 1.57 goals per 90 minutes. He's the only player (with over 300 minutes played) in the Bundesliga averaging more than a goal per 90. Filter out penalties and he's averaging "only" 1.27 goals per 90. That, at least brings him to almost within a third of a goal of his closest competitor, Paco Alcácer at 0.97. Nobody else in the league cracks the 0.,80 barrier.

How exactly is he doing this? The answer is that he's doing the two things that every great scorer dreams of doing. He's taking lots of shots and he's taking only great shots. Do that and things look really really easy. Lewandowski is taking the most shots in the league, 4.58 per 90, and among forwards is averaging the third highest shot quality at 0.18 expected goals per shot. It's just exceptionally rare to be both a high quality and high quantity shooter.

There only 15 players in the Bundesliga averaging over three shots per 90 minutes. And, of those players, only two are near Lewandowski. Alassane Pléa and Timo Werner are both also averaging 0.18 xG per shot, but they have only 3.21 and 3.35 shots per 90 respectively. Those are both really good totals, and in an alternate universe where Lewandowski didn't exist we'd be talking about their numbers as being uniquely able to capitalize on both of a striker's necessary skills. It just happens to be that Lewandowski is superhuman outdoes them both in each category.

The reason that this shot profile is so rare is that most high volume shooters buttress their great shots with a raft of more speculative efforts. Lewandowski doesn't.

Put it all together and Lewandowski's shot chart is simply a thing of beauty. It's certainly true that his hot start to the season has him overperforming his xG but that xG is itself just absolutely mammoth.

It's likely that he won't keep up this absurd level of goal scoring. Nobody runs this hot forever. But, the underlying numbers, while fantastic, aren't particularly beyond what we've come to expect from the Polish striker. Last season his xG per shot was virtually identical to the numbers he's putting up now. The main difference is that he's averaging half a shot more per match.

That might seem small, but do the math. Over the course of a season that works out to 17 more shots. If his xG per shot remains constant at 0.18 then that means that the increase in shots should lead to roughly three more goals. Such margins are the kinds of things titles are won and lost on. Robert Lewandowski is fantastic.

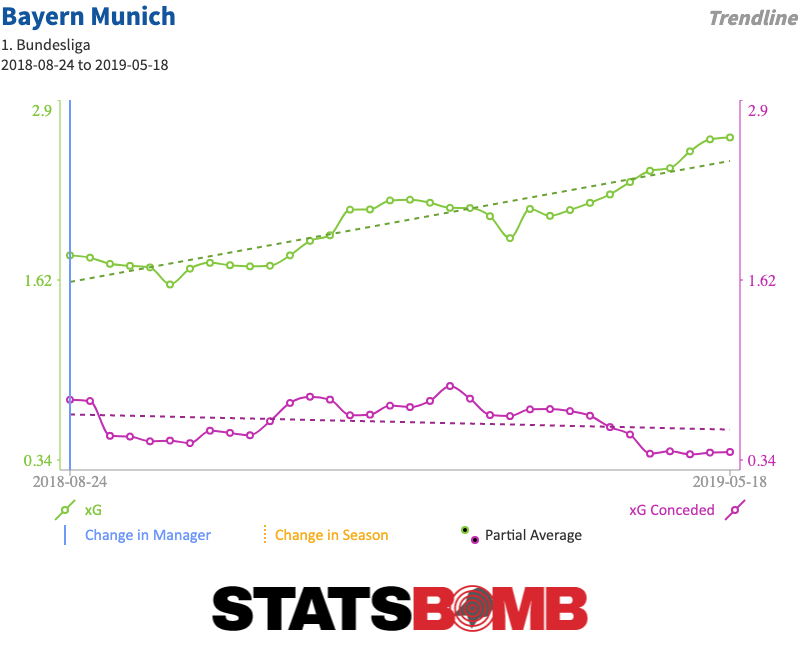

He gets all the shots, and they're all great. Bayern have gone a long way to revamping their attack this season. Franck Ribery and Arjen Robben are gone with Serge Gnabry and Kingsley Coman stepping into their huge shoes. Philippe Coutinho and Ivan Perišić arrived to help shoulder the load. But, at the end of the day, it remains Lewandowski sitting atop it all, unparalleled, and hammering in all the goals.

Marco Giampaolo's AC Milan is off to a miserable start in Serie A

“I believe in my ideas, but this Milan team looked like it turned up without ever having a training session together. It played badly on an individual level, with no organization or sense of collective responsibility”. Nothing gives a clearer impression of how poorly AC Milan's season has started than the words pronounced by their own coach, Marco Giampaolo, at the end of the match against Fiorentina. The three goals scored by the Viola at San Siro resulted in the fourth defeat in six games for the Rossoneri, surely not the landmark that their fans, who left the stadium on Sunday evening well before the final whistle, were expecting to reach after yet another new start. Milan hadn't lost four of the first six games since the 1938-39 season. And what's even more worrying is that the six points collected so far, are the result of wins, both for 1-0, against Brescia and Hellas Verona, two of the three teams just promoted from the Serie B. The Berlusconi era is now well over and in recent years, Milan's technical potential has been gradually depleted and not even the most sanguine of their supporters expected this team to compete for the Scudetto, but it was rather difficult to predict such an abysmal start. This summer the management selected by the Elliot fund (which includes club legends Paolo Maldini and Zvonimir Boban) has followed a transfer market strategy aimed at cutting wages (-€25 million compared to last season) and towards the purchasing of young players to be developed, such as 20-years-old striker Rafael Leao, which can allow the club to draw significant resources from player trading and therefore to pursue a sustainable growth model. The policy makes even more sense given that they've been excluded from the Europa League over breaches of Financial Fair Play rules. In theory then, a coach capable of nurturing talent, such Giampaolo, sould play a key role. All in all, the roster at Giampaolo's service is not very different from the one which Gennaro Gattuso led to fifth place last season. In addition to Leao, they purchased Léo Duarte (23 years old) as a backup for centerbacks Alessio Romagnoli and Mateo Musacchio, leftback Theo Hernández (21), Empoli’s midfielders Ismaël Bennacer (21) and Rade Krunic (25) and Ante Rebic (25), who arrived on loan in a double swap deal, with André Silva joining Eintracht Frankfurt on loan for two years. Although new purchases were not immediately included in the starting XI (their total playing time to date accounts for 14.9% of total minutes), so far Milan players have not been able to assimilate the ideas of the former coach of Sampdoria, whose employment status is now tenuous at best. Although Giampaolo has tried to propose tweaks to his favorite system of play, the 4-3-1-2, AC Milan’s play has been very poor both on offense and defense. The results are only the logical consequence of the team's performance.

Offensive struggles and tactical conundrums

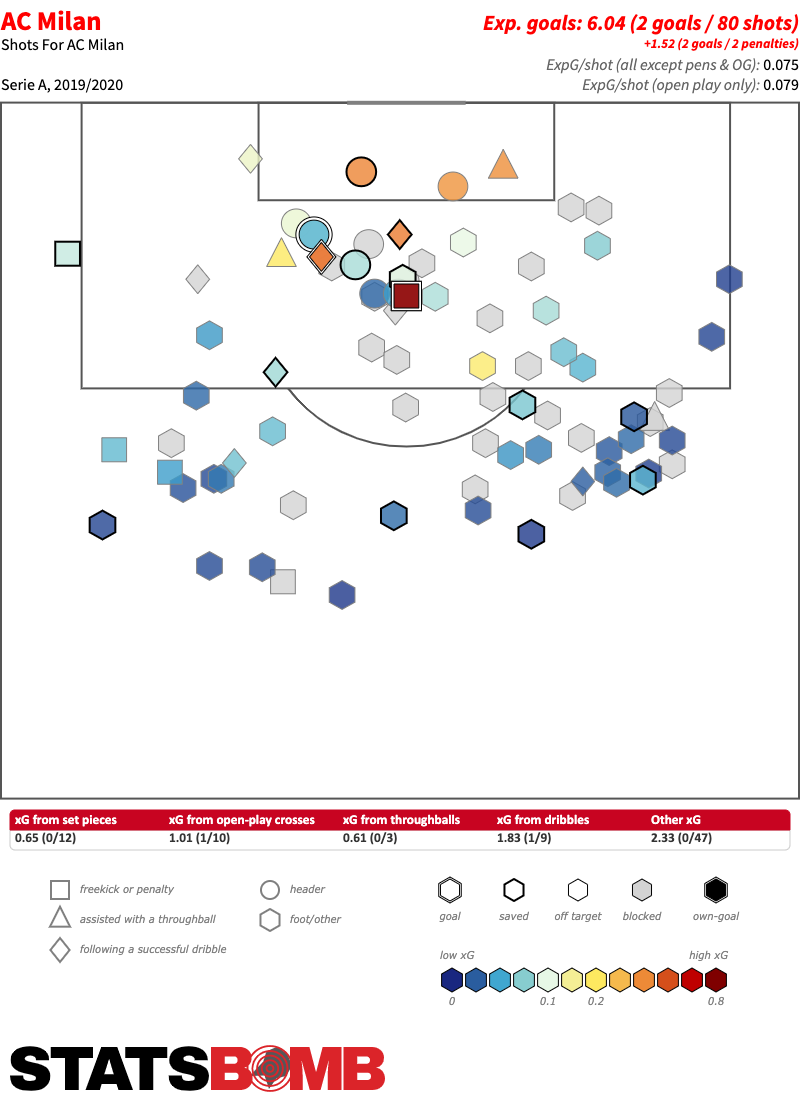

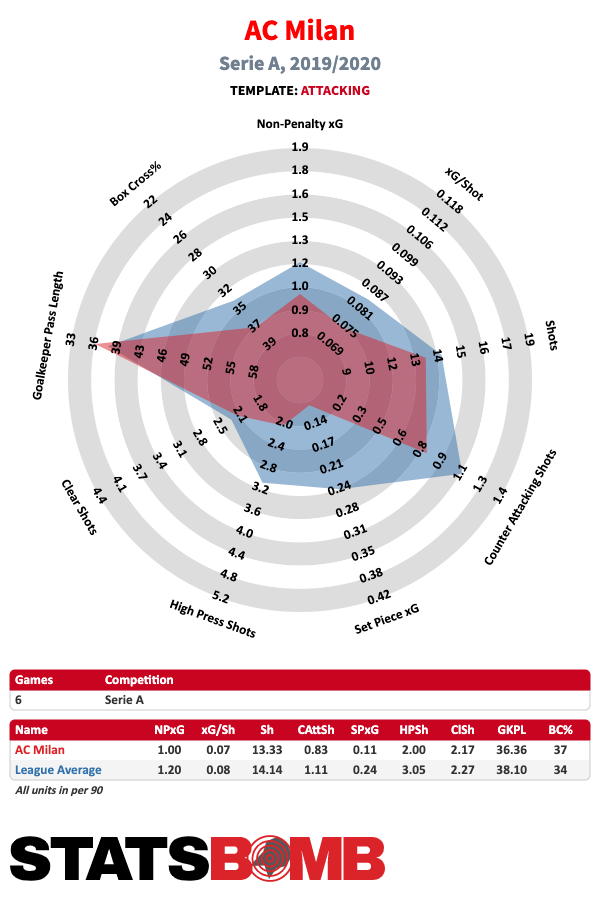

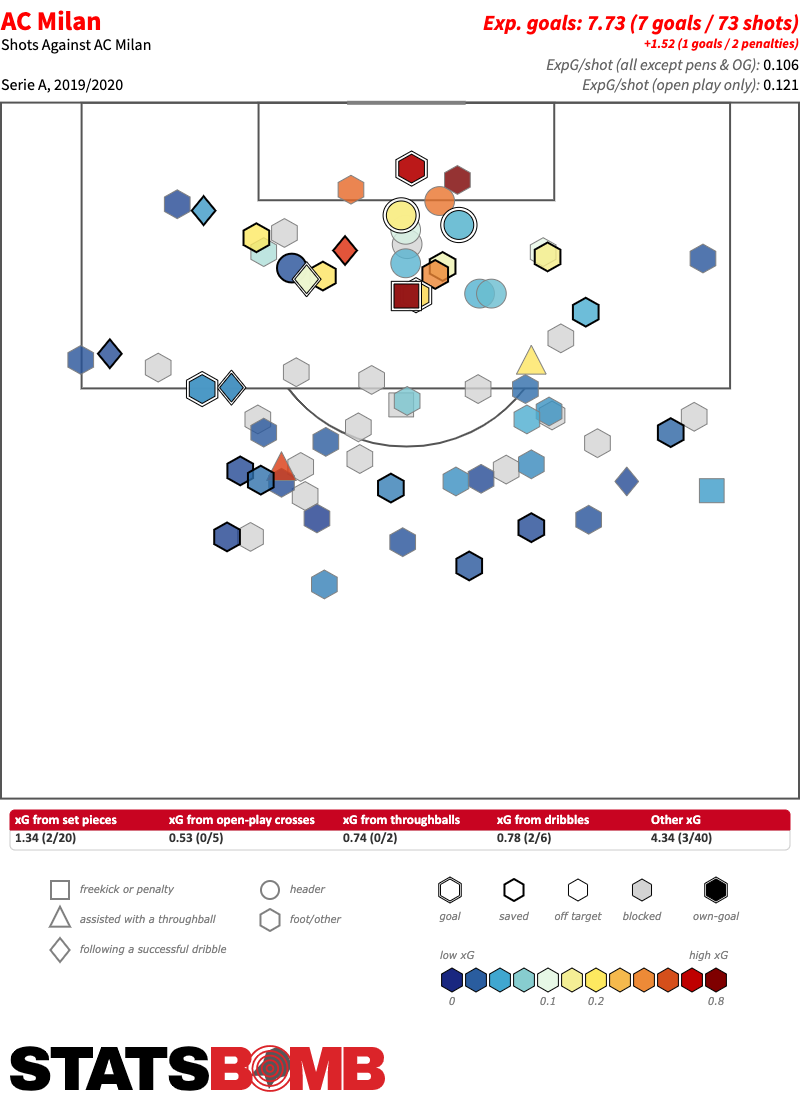

At Giampaolo's debut on the Milan bench, the Rossoneri weren't able to fire a single shot on target against Udinese’s keeper Juan Musso and generated just 0.52 expected goals. Apart from a 2.32 xG outlier against Torino, which was the best Milan game of the season, they have struggled to create high-scoring opportunities (0.075 xG/shot on average, sixteenth in the league) and to convert them in other matches, too. No wonder their shot map looks like Pablo Picasso’s palette during his Blue Period.  Not only have they generated just 1.00 xG on average (13th in the league), but they have not been able to convert their chances at a rate not even remotely acceptable, having scored only two open play goals, the worst figure in the entire Serie A. They are below league average in every main offensive stat, so of course their attacking radar looks ugly.

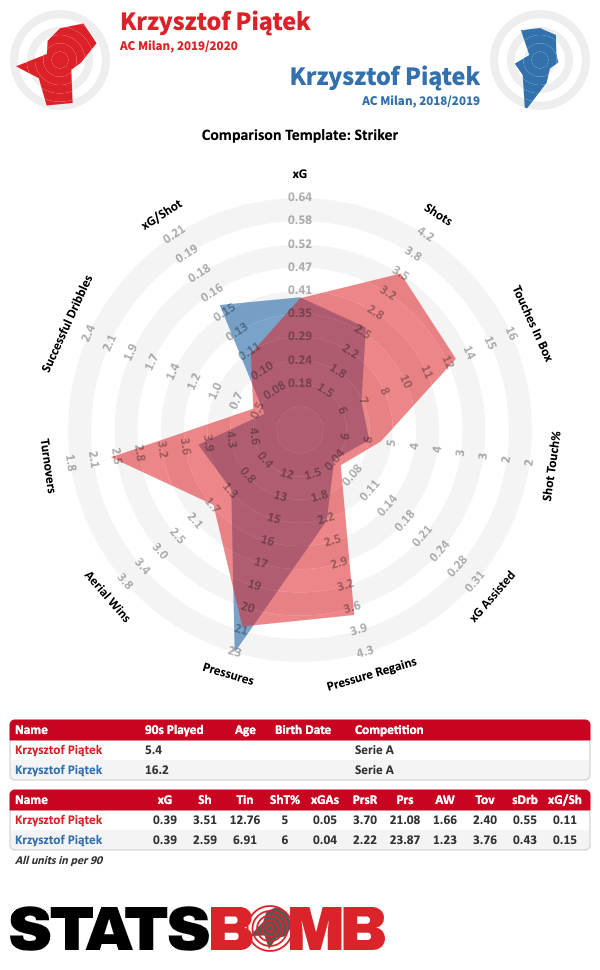

Not only have they generated just 1.00 xG on average (13th in the league), but they have not been able to convert their chances at a rate not even remotely acceptable, having scored only two open play goals, the worst figure in the entire Serie A. They are below league average in every main offensive stat, so of course their attacking radar looks ugly.  In a situation where the team has a hard time scoring, it's normal for the starting striker to become the target of criticism. Krzysztof Piątek is responsible for 35% of Milan's total xG (2.11 out of a total of 6.04 xG), but he's still on the hunt for his first open play goal. An xG overperformer in 2018-2019 (his scoring efficiency was ~146%), the average quality of his shots this season (0.111) is much lower than that of the 1459 minutes played with AC Milan jersey last season (0.152), but in line with that of his amazing period at Genoa (0.102), in which he scored at will but with a rate well beyond expectations.

In a situation where the team has a hard time scoring, it's normal for the starting striker to become the target of criticism. Krzysztof Piątek is responsible for 35% of Milan's total xG (2.11 out of a total of 6.04 xG), but he's still on the hunt for his first open play goal. An xG overperformer in 2018-2019 (his scoring efficiency was ~146%), the average quality of his shots this season (0.111) is much lower than that of the 1459 minutes played with AC Milan jersey last season (0.152), but in line with that of his amazing period at Genoa (0.102), in which he scored at will but with a rate well beyond expectations.  In general, if you look at his data, he's shooting more, touching twice as many balls in the box and losing the ball less than during his first six months with the Rossoneri. But are we sure that he will ever stand out as a lone striker in a system of play that doesn't capitalize on his strengths? Piatek is a poacher. His greatest ability is scoring goals. When he doesn't score, though, his limitations emerge more clearly. His overall contribution to team play is not consistent and even if he doesn't lose too many balls, he's not particularly effective with his back to the goal (his percentage of completed passes decreases by 12% when he is pressed) or at playing wall-passes, which are pivotal to ball progression in Giampaolo’s system. He doesn’t create scoring chances for his team-mates (0.05 open play xG assisted per 90 minutes this season, 0.04 last season) and not even for himself, given that he rarely manages to dribble his direct opponent (0.55 successful dribbles per 90 this season, 0.43 last season). Since Piatek can't be expected to create opportunities, it's the players around him who have to do it. In this sense, there were high expectations for Suso. Throughout the summer it was discussed whether the Spaniard could prove to be the right player to play as the trequartista in Giampaolo's 4-3-1-2. So far, the answer on the pitch seems to be negative, so much so that the Milan coach has given up deploying Suso in that role, choosing instead a 4-3-3 in the last few games. Suso plays 1.74 open-play key passes per 90, more than any teammate with at least 300 minutes played, but his contribution in terms of xG assisted is at 0.17 per 90. That's not really what you expect for your main creator. Moreover, his attacking danger is limited to the few chances he creates, since he generated only 0.09 xG per 90 from over two shots on average because of the highly questionable shooting selection that has characterized his career. Suso is a player who has a reluctance to use both feet and who tends to be predictable: he seemed lost away from the right flank and Giampaolo immediately had to move him back in his natural position. A bit like Piatek, he seems not very functional to the new football project and he has already become a walking tactical conundrum in Milanello. In theory, along with goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma, the Spaniard was the most valuable asset on the roster and since at least on paper his compatibility with football ideas of the new coach (despite the statements of Giampaolo himself) was limited, he could have been sacrificed on the transfer market to finance the signings of different kind of players. But apparently it was his new manager’s decision to keep him, so now it is also his problem to solve. And it’s a problem that needs to be solved fast, considering that the team's midfield isn't exactly showing any signs of brilliance either. Milan’s offensive structure is often disconnected and there are limited options for progressive passes and a lack of players between the lines to receive the ball. Although there is almost no difference between the average number of carries of Hakan Calhanoglu and Franck Kessié and the midfielders of Sampdoria last season, the eye test tends to suggest that the two keep the ball too much (and indeed their carries are 13.5% longer on average) and distribute it with too much laziness, giving the opponents time to take sides on the pitch or, worse, to recover the ball, as happened on the occasion of two of the three goals for Fiorentina, both created by the Turkish player's turnovers. Below you can see the map of their open play passing combined and see how it is full of horizontal passes while also lacking penetration in central zones.

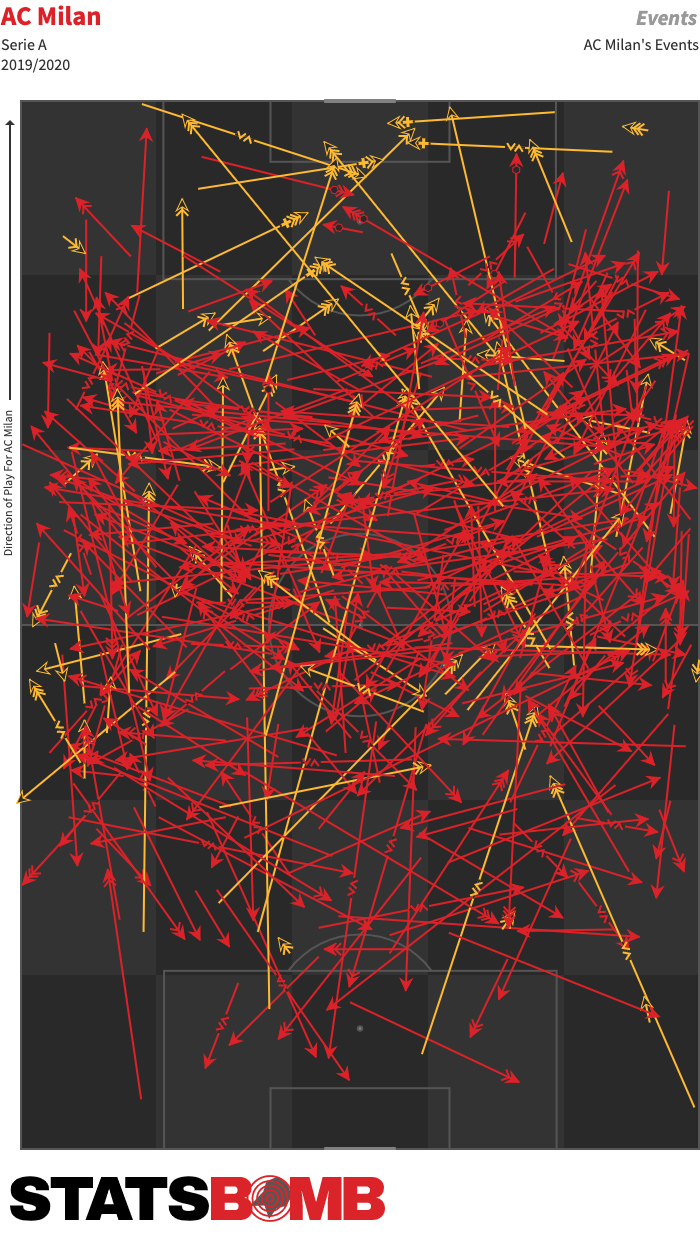

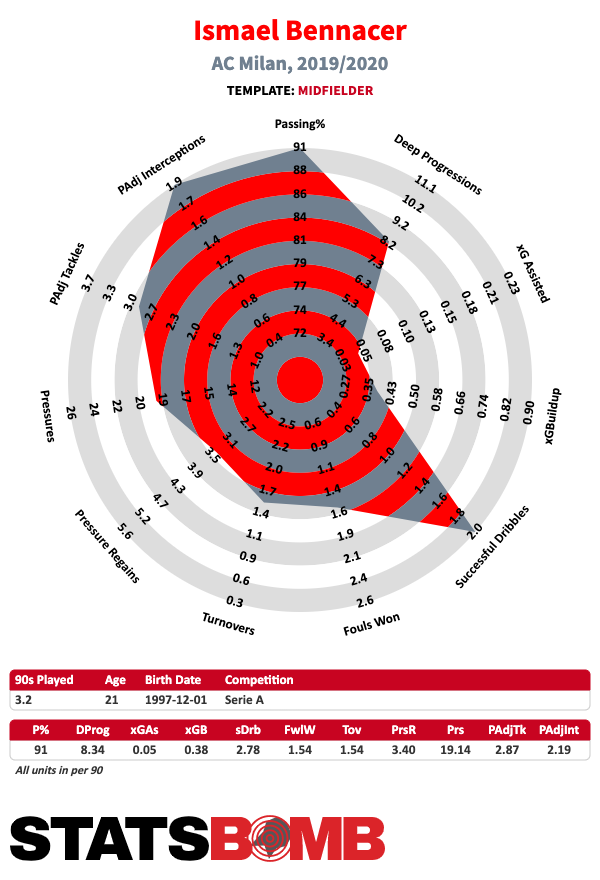

In general, if you look at his data, he's shooting more, touching twice as many balls in the box and losing the ball less than during his first six months with the Rossoneri. But are we sure that he will ever stand out as a lone striker in a system of play that doesn't capitalize on his strengths? Piatek is a poacher. His greatest ability is scoring goals. When he doesn't score, though, his limitations emerge more clearly. His overall contribution to team play is not consistent and even if he doesn't lose too many balls, he's not particularly effective with his back to the goal (his percentage of completed passes decreases by 12% when he is pressed) or at playing wall-passes, which are pivotal to ball progression in Giampaolo’s system. He doesn’t create scoring chances for his team-mates (0.05 open play xG assisted per 90 minutes this season, 0.04 last season) and not even for himself, given that he rarely manages to dribble his direct opponent (0.55 successful dribbles per 90 this season, 0.43 last season). Since Piatek can't be expected to create opportunities, it's the players around him who have to do it. In this sense, there were high expectations for Suso. Throughout the summer it was discussed whether the Spaniard could prove to be the right player to play as the trequartista in Giampaolo's 4-3-1-2. So far, the answer on the pitch seems to be negative, so much so that the Milan coach has given up deploying Suso in that role, choosing instead a 4-3-3 in the last few games. Suso plays 1.74 open-play key passes per 90, more than any teammate with at least 300 minutes played, but his contribution in terms of xG assisted is at 0.17 per 90. That's not really what you expect for your main creator. Moreover, his attacking danger is limited to the few chances he creates, since he generated only 0.09 xG per 90 from over two shots on average because of the highly questionable shooting selection that has characterized his career. Suso is a player who has a reluctance to use both feet and who tends to be predictable: he seemed lost away from the right flank and Giampaolo immediately had to move him back in his natural position. A bit like Piatek, he seems not very functional to the new football project and he has already become a walking tactical conundrum in Milanello. In theory, along with goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma, the Spaniard was the most valuable asset on the roster and since at least on paper his compatibility with football ideas of the new coach (despite the statements of Giampaolo himself) was limited, he could have been sacrificed on the transfer market to finance the signings of different kind of players. But apparently it was his new manager’s decision to keep him, so now it is also his problem to solve. And it’s a problem that needs to be solved fast, considering that the team's midfield isn't exactly showing any signs of brilliance either. Milan’s offensive structure is often disconnected and there are limited options for progressive passes and a lack of players between the lines to receive the ball. Although there is almost no difference between the average number of carries of Hakan Calhanoglu and Franck Kessié and the midfielders of Sampdoria last season, the eye test tends to suggest that the two keep the ball too much (and indeed their carries are 13.5% longer on average) and distribute it with too much laziness, giving the opponents time to take sides on the pitch or, worse, to recover the ball, as happened on the occasion of two of the three goals for Fiorentina, both created by the Turkish player's turnovers. Below you can see the map of their open play passing combined and see how it is full of horizontal passes while also lacking penetration in central zones.  There aren’t many more alternatives in midfield and unless Giampaolo plays Lucas Paquetá, who could also be a good trequartista if the team went back to a 4-3-1-2, there is not much room to twist the line-up in these roles and we will likely see the same midfield in the coming games, too. Surely Ismael Bennacer, who seems to have now surpassed Lucas Biglia, AC Milan’s oldest player at 34, as the starting holding midfielder, seems to be able to bring more incisiveness to the passing game of Milan, although the match with Fiorentina was a disaster for him because of the two penalties he caused.

There aren’t many more alternatives in midfield and unless Giampaolo plays Lucas Paquetá, who could also be a good trequartista if the team went back to a 4-3-1-2, there is not much room to twist the line-up in these roles and we will likely see the same midfield in the coming games, too. Surely Ismael Bennacer, who seems to have now surpassed Lucas Biglia, AC Milan’s oldest player at 34, as the starting holding midfielder, seems to be able to bring more incisiveness to the passing game of Milan, although the match with Fiorentina was a disaster for him because of the two penalties he caused.  Speaking of new signings, Rafael Leao is definitely worthy of a starting spot and the Portuguese could be, at least in part, the solution to Milan's problems. So far the 20-year-old, who scored 0.53 non-penalty goals per 90 for Lille last season, has played mainly on the left wing, but he has the off-the-ball moves, the strength, and the smartness to play with his back to his goal to complement Piatek in a striking partnership or to play as the lone striker. In both cases, unless Suso significantly improves in a central offensive midfielder role, Giampaolo will have to make an important decision and probably put the Spaniard or Piatek on the bench. The Portuguese striker (2.67 dribbles and 2.00 key passes on average, in just 270 minutes) can give that offensive unpredictability that Milan damn well needs while the team adapts to the new brand of football. Focus on what Leao does before the goal here: shielding the ball with his back to the goal, passing it to a team-mate to gain territory and offering a passing option toward the inside of the pitch to the wide ball-carrier.

Speaking of new signings, Rafael Leao is definitely worthy of a starting spot and the Portuguese could be, at least in part, the solution to Milan's problems. So far the 20-year-old, who scored 0.53 non-penalty goals per 90 for Lille last season, has played mainly on the left wing, but he has the off-the-ball moves, the strength, and the smartness to play with his back to his goal to complement Piatek in a striking partnership or to play as the lone striker. In both cases, unless Suso significantly improves in a central offensive midfielder role, Giampaolo will have to make an important decision and probably put the Spaniard or Piatek on the bench. The Portuguese striker (2.67 dribbles and 2.00 key passes on average, in just 270 minutes) can give that offensive unpredictability that Milan damn well needs while the team adapts to the new brand of football. Focus on what Leao does before the goal here: shielding the ball with his back to the goal, passing it to a team-mate to gain territory and offering a passing option toward the inside of the pitch to the wide ball-carrier.  The same goes for left-winger Ante Rebic, who has so far played just 82 minutes overall and could find more space in a different configuration. The Croatian is a player who takes risks, which is something that for now his teammates don't do, knows how to overtake his direct opponent and is also able to offer a good scoring contribution for a wide player. The under fire ex-Sampdoria manager has to earn himself time and Leao and Rebic could give it to him.

The same goes for left-winger Ante Rebic, who has so far played just 82 minutes overall and could find more space in a different configuration. The Croatian is a player who takes risks, which is something that for now his teammates don't do, knows how to overtake his direct opponent and is also able to offer a good scoring contribution for a wide player. The under fire ex-Sampdoria manager has to earn himself time and Leao and Rebic could give it to him.

When pressing fails, the defense collapses

In the first three games, the defense had been the main strength of Milan: conceding a single goal, the Rossoneri had managed to earn 6 points out of 9 despite their offensive woes. But it is also true that Udinese (18th for non-penalty xG), Brescia (17th) and Hellas Verona (13th) are among the worst teams in Serie A in terms of offensive production. It was therefore predictable that Milan would suffer more against stronger opponents. In the following three games against Inter, Torino and Fiorentina, Milan suffered 6 open play goals, conceding way more opportunities to their opponents. But, if Giampaolo was expected to make the Rossoneri defend higher up the pitch, you can’t be particularly disappointed. Milan is third in defensive distance and fourth in passes per defensive action (PPDA), two indexes of a team that brings relatively high and aggressive pressure. Among other positive notes, they are the team with the second most counterpressure actions (232) and they also conceded the least deep completions in the league (just two on average).  The main defensive problem is the high average value of opponents' chances. AC Milan concedes open-play shots with an average xG of 0.12, a sign that when the pressing fails (and we saw it well in games against Torino, Inter and Fiorentina) there are too many spaces in which to build high-scoring opportunities. Pressing requires well-oiled mechanisms that develop over time, but when those processes fail, Milan is far too vulnerable and there is too much space to cover for defensive players. That situation puts a strain on the center backs, who are often forced to face their opponents one on one in critical situations. Romagnoli, who last year was the best defender in the league in percentage of tackles compared to times dribbled pass (87%), is now dribbled 44% of the time that he attempts a tackle, while the percentage rises to 56% for the other defender Musacchio. You don't become a pressing defensive force in a month, but again since they aren't scoring, there's no cushion compensate for those goals conceded due to growing pains.

The main defensive problem is the high average value of opponents' chances. AC Milan concedes open-play shots with an average xG of 0.12, a sign that when the pressing fails (and we saw it well in games against Torino, Inter and Fiorentina) there are too many spaces in which to build high-scoring opportunities. Pressing requires well-oiled mechanisms that develop over time, but when those processes fail, Milan is far too vulnerable and there is too much space to cover for defensive players. That situation puts a strain on the center backs, who are often forced to face their opponents one on one in critical situations. Romagnoli, who last year was the best defender in the league in percentage of tackles compared to times dribbled pass (87%), is now dribbled 44% of the time that he attempts a tackle, while the percentage rises to 56% for the other defender Musacchio. You don't become a pressing defensive force in a month, but again since they aren't scoring, there's no cushion compensate for those goals conceded due to growing pains.

Conclusion

It seems absurd after only six games, but the new Milan project is already hanging by a thread. Changing the sixth coach in five years now would probably be a mistake, since at least in the first half against Torino we saw what the team is capable of, but this group is still too far behind and the problems are not just about learning the new system. It's time for Giampaolo to take important choices before the management takes them about his future.

Joshua Kimmich is the key to Bayern's revitalized midfield

Considering that it’s my first weekly digest about the Bundesliga on Statsbomb - Sam, nice to meet you etc. - I figured that I’d start off with a spicy take about the powerhouse of German football. And by take, I mean TAKE. Ready? Here it goes. I believe that Bayern München, who have been criticized a fair bit on their transfer business these past few months - most notably when they missed out on signing Manchester City winger Leroy Sané or RB Leipzig speedster Timo Werner as the future frontman of their attack - might have made one of the sweetest deals amongst all the big summer signings in international football. His name? Benjamin Pavard. Really, Benjamin Pavard.

Yes, the same Pavard that was the most boring starter on one of the most boring World Cup-winning teams in recent memory - mind you, in a French starting eleven that featured Oliver Giroud as a striker up top. Yes, the same Pavard that played in the heart of VfB Stuttgart’s defence, which ceded 70 goals in 34 league games on its way to relegation last season. Yes, even the same Pavard that hasn’t looked all that comfortable on the pitch in his first weeks as a Bayern regular.

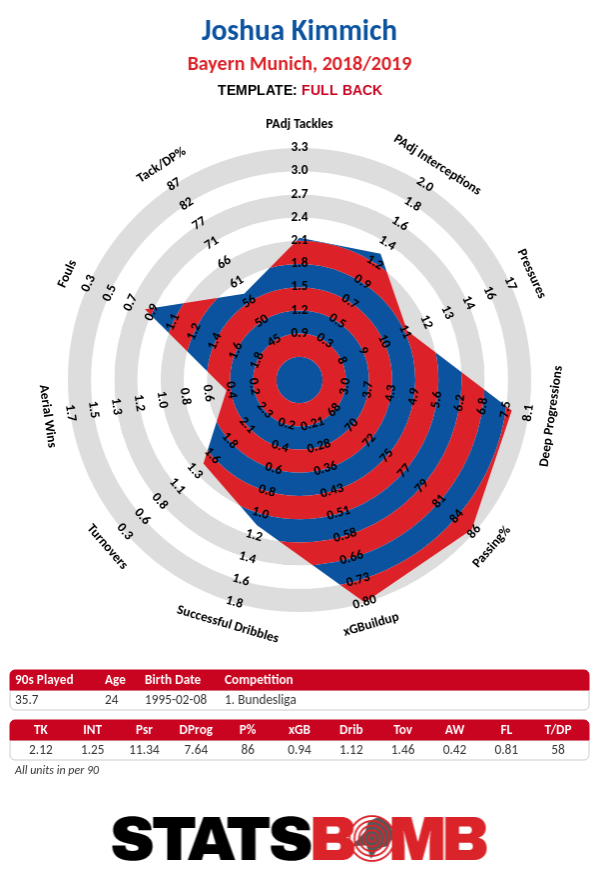

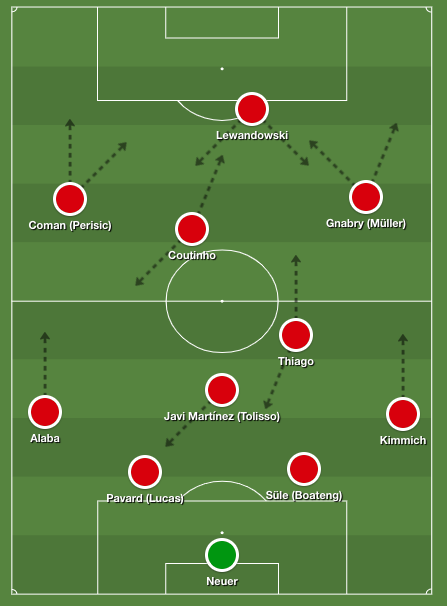

The most logical question to ask now would in fact be: why? Why is the signing of this clearly talented, but somewhat boring and at times even shaky, young French defender such a win for Bayern? The answer is rather simple. Because the arrival of a dependable right back has promptly given Der Rekordmeister one of the best - if not the best - midfield duo’s in all of European club football. The presence of Pavard on the roster has provided manager Niko Kovac with a legitimate option at the right side of defense, which has opened up the door for Joshua Kimmich to move up to a spot in the heart of Bayern’s midfield, right next to the oft-injured, but excellent Thiago Alcántara. This midfield is good, y’all.

Yes, there was, or is, a strong case to be made that Kimmich might have been the best right-back in all of European football for the past few seasons. Especially from an offensive point of view. Kimmich played in 81 Bundesliga and Champions League games the past two seasons, in which he posted the absurd tallies of 28 assists and 178 chances created. Which is - *check notes* - ridiculous for a fullback, even one who specialises in corner kicks.

This level of production for a fullback goes a long way in explaining how Kimmich did not make the transition to midfield earlier at Munich - as a teen at Leipzig, he actually played as a midfielder. Kovac et al already knew what Kimmich’s skill-set was, but the risk of giving up a large chunk of his output on the flank made the seemingly logical switch to midfield a pretty dicey proposition.

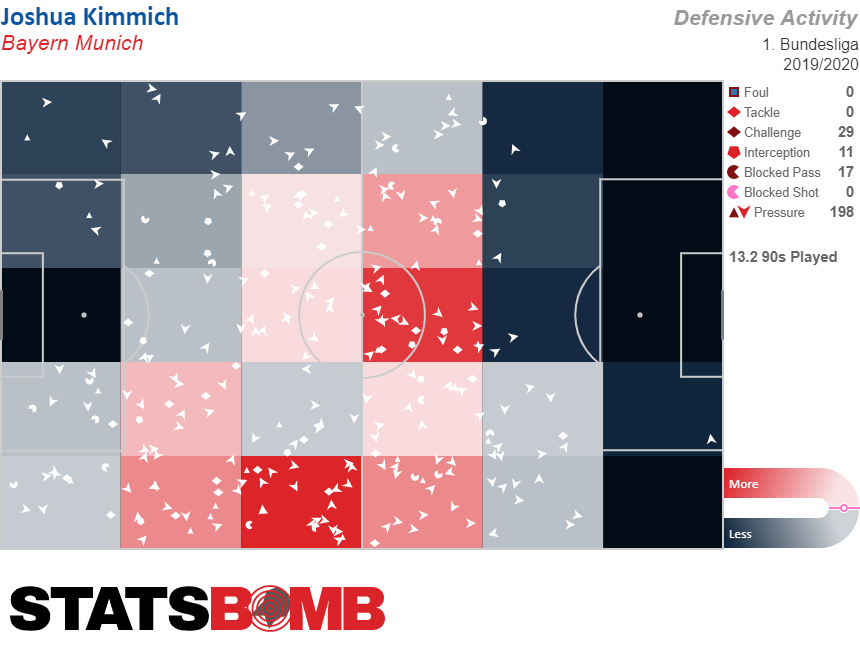

Ralf Rangnick once lauded Kimmich as the most tactically sound, positionally fluid player he had ever seen. Kimmich is the poster child for the wave of tactical and technical innovation that swept through German in the last decade plus: he’s lightning-quick as a decision-maker, has always been smart beyond his years in positional play, reacts fast, possesses good ball-control with both feet, applies pressure on the ball in a rather relentless way, hounds passing lanes and, maybe most importantly for a player in his tactical role, is the type of star player that can also excel in a non-star-role. Which, at Bayern, is kind of a big deal.

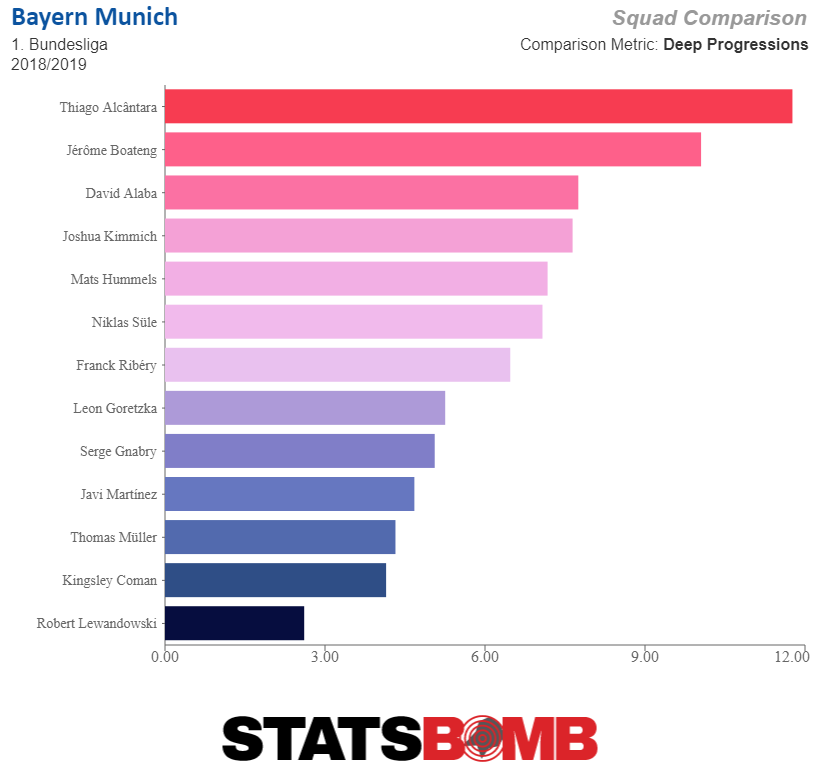

If Kimmich is the Prince of Pragmatism (from the House of Gegenpressing), Thiago can be viewed as the Sultan of Style. The Spaniard is often overlooked in the debates about who the best midfielder in the world currently is, and that has a lot to do with Thiago’s one glaring weakness: he truly deserves the label ‘injury-prone’. Even though the playmaker has avoided another major injury since his ACL tear in 2014, Thiago has missed 40 out of a possible 208 competitive matches with nine different smaller injuries since the start of 2015-16. When Thiago is able to play, he pretty much balls out. Due to his silk first touch, his Xavi-esque vision of what transpires around him on the pitch - he is one of those passing wizards for which the football cliché of ‘player X sees things before they even happen’ seems to be invented - his at times jaw-dropping ball control, his accurate short ánd deep passing and his impressively calm on-field demeanour, Thiago regularly looks ‘un-pressable. Unsurprisingly, he led Bayern in deep progressions per 90 minutes last season (among players with over 1200 minutes).

The combination of his flair and ball progression with the durability, stamina, and tactical flexibility of Kimmich gives Bayern something they’ve been searching for for quite some time: an elite midfield duo at the heart of their squad.

The fact that a bunch of the star players were deteriorating at the same time last season, drew some attention away from Bayern’s ongoing search for the ideal balance in midfield. Whilst an at times unrecognizable Manuel Neuer, a slowed-down Jérôme Boateng and an out-of-form Mats Hummels took the brunt of the criticism last year, mainly due to the team’s vulnerability against the counter-attack, the midfield just wasn’t all that good, for the lofty standard Bayern have set for themselves. Especially in the games where Thiago was out. This midfield struggle, one of the main reasons Bayern struggled in the early months of Kovac’s tenure last season, was a long time coming. They simply didn’t have the same amount of really good-football-plsaying dudes that they did it in the days of Guardiola. Javi Martínez’ decline was foreseeable, the Basque defensive band-aid in midfield never was much of a speedster, and quietly fell off a cliff, agility-wise, last season. Renato Sanches just wasn’t Bayern material. Corentin Tolisso missed all of last year with an ACL injury. Leon Goretzka is a good all-around player, but seems to be functioning better in a more attacking role.

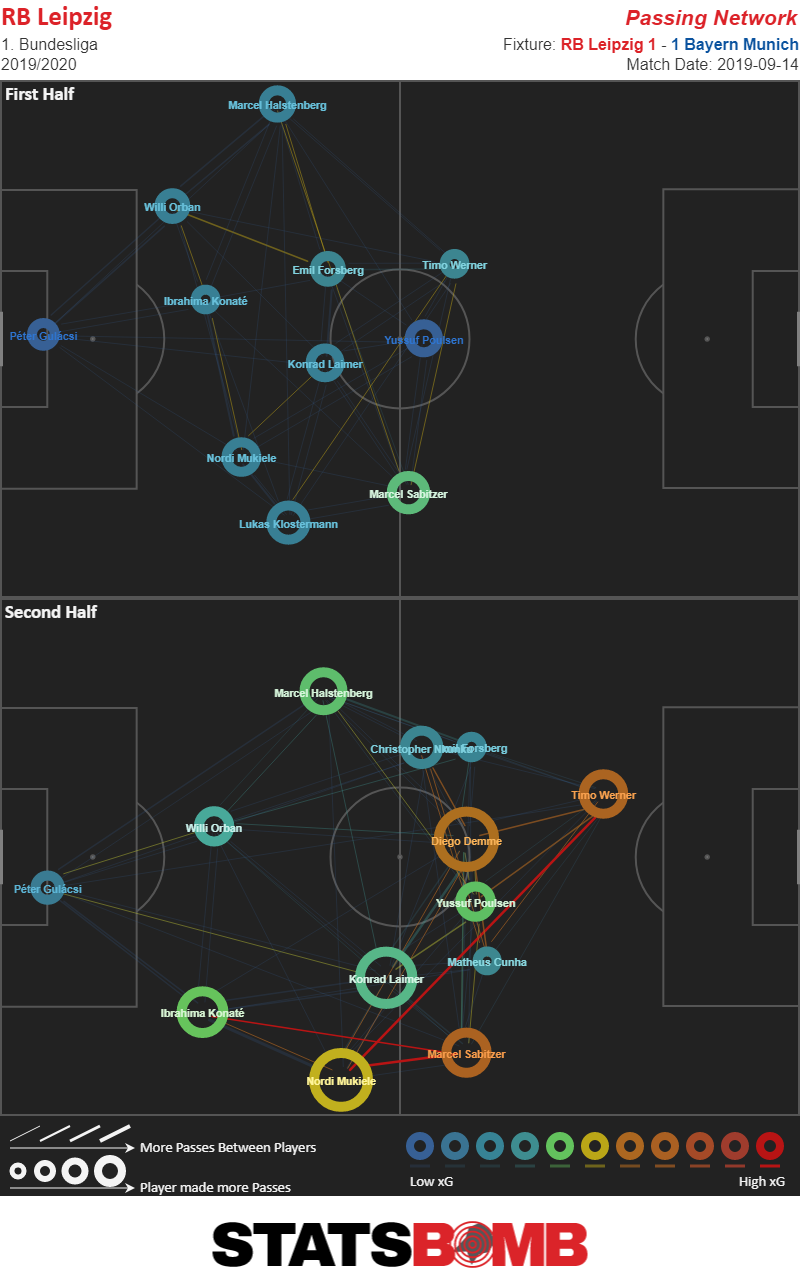

But none of the midfield sets Kovac could forge out of those options, seemed anywhere near as comfortable in possession as Bayern has looked in its last two league games, against Mainz (6-1) and at RB Leipzig (1-1). In the first big league fixture of Bayern’s league campaign, they were cruising in the first half against Leipzig. If it weren’t for two rigorous tactical changes from Julian Nagelsmann at half-time - switching from a 5-3-2 to the Red Bull-approved 4-2-2-2 ‘vice grip’ formation, and letting Yussuf Poulsen start his press from a cover shadow on one of Bayern’s midfielders in the second half - that brought new life to Leipzig’s patented press, the reigning champ would’ve crushed the energy drink-fueld new kid on the block last weekend. Making Leipzig’s pressing scheme look ineffective, even toothless, is one tall order.

And Thiago and Kimmich managed just that in the first half, with Pavard not only providing solid defensive work on the right in Kimmich’s old spot, but also offering Bayern a lot more flexibility in its build-up: varying between ‘3+1’ (three defenders, one midfielder in the build-up), ‘3+2’ or ‘2+4’ is a lot easier when both your fullbacks - Pavard and the big money signee Lucas Hernández (from Atlético Madrid) - have had experience at positions in the center of the defense.

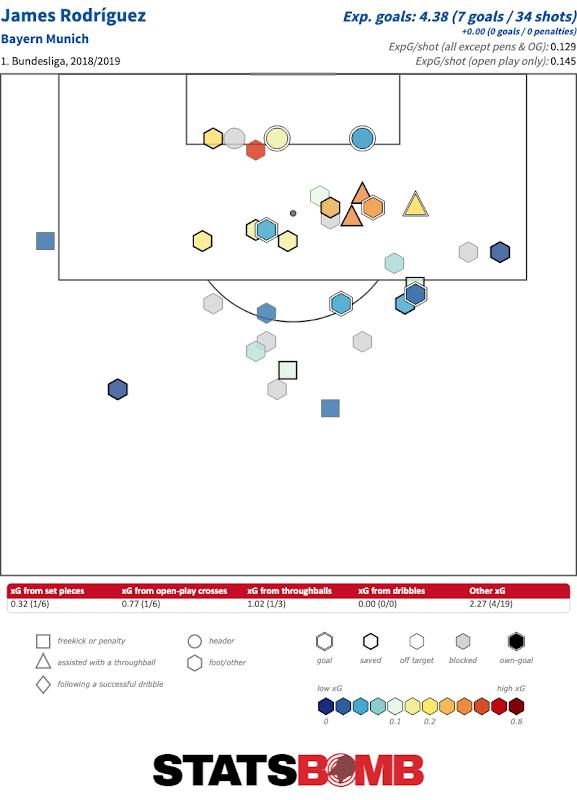

Bayern’s offense looks to be zooming, at the moment. And the prospect of Thiago-and-Kimmich-run midfield is very exciting for all of us tactics nerds out there. The biggest question mark in the formation is the 10-position. Goretzka has proven to be a valid option for that role, with his patented box-runs and general technical usefulness. If Bayern can coax the real Philippe Coutinho from the ghost-version of him in his days at Camp Nou, the Brazilian would be the main option. But as it stands, it seems that all signs point to - who else? - Thomas Müller. If you put the premier Raumdeuter - ‘explorer of space’ - in front of a functioning central midfield and behind a world-class striker, watch out. And that is exactly what Bayern’s competition should do.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

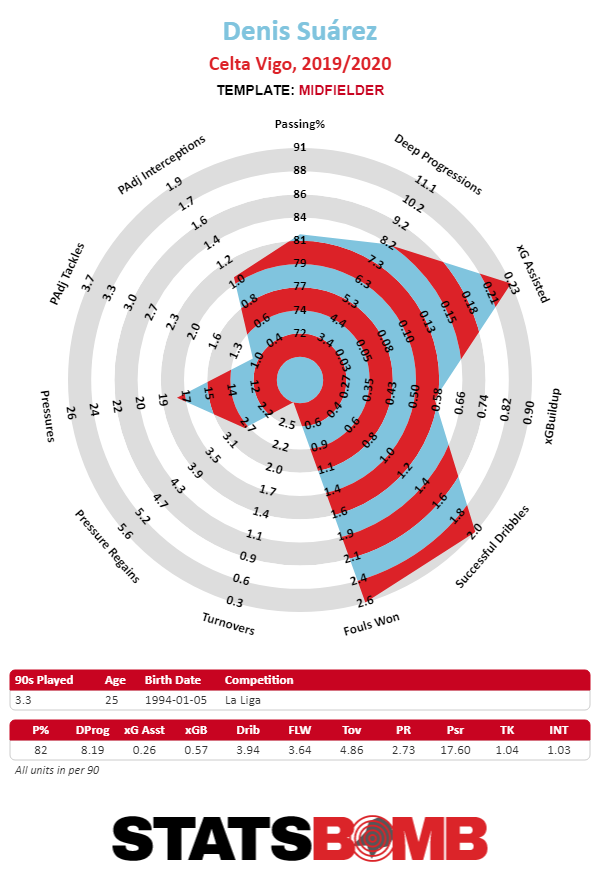

Denis Suárez has come home, and Celta Vigo are reaping the rewards

Celta’s Plan A in recent years was simple; get the ball to Iago Aspas. Plan B was to make sure Plan A didn’t get injured. Having lost Daniel Wass and Maxi Gomez in recent seasons, Celta knew they had to not only reinvest in the squad but reinvent themselves to become more anti-fragile. Relying on one excitable talent is not a sustainable strategy.

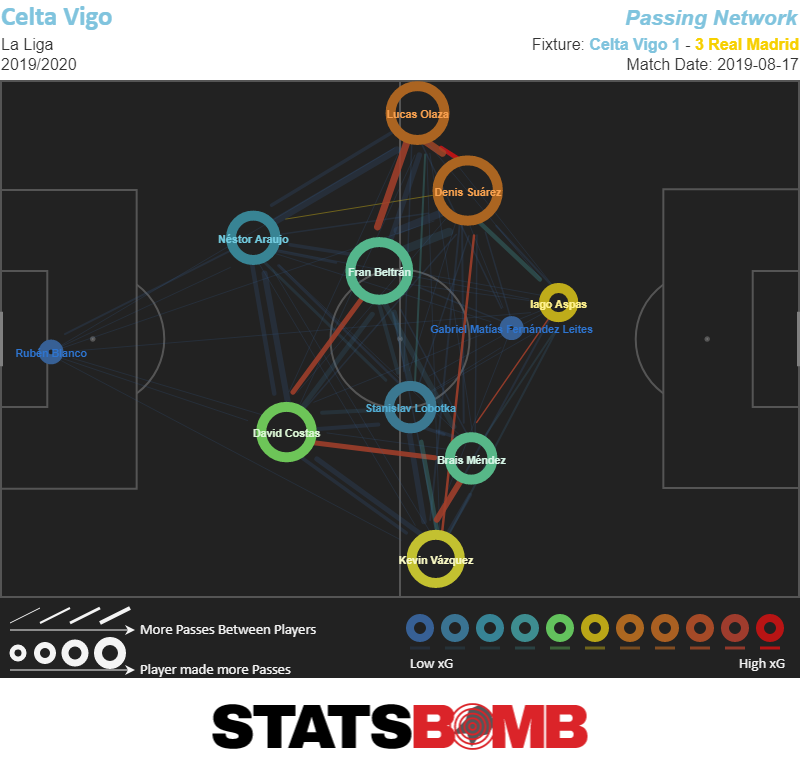

Felipe Miñambres, who worked wonders with Rayo Vallecano during their longest ever spell in La Liga before leaving for Vigo, has done some of the most significant work in all of European football this summer. He has identified players who can play in Fran Escriba’s preferred system — 4-4-2 — and built a side which is likely to be one of the best teams to watch in Spain. After three games, Denis Suárez has been a key to the newly revitalized team.

Suárez was convinced that he would make it at Barcelona. There was the sense that if he left the club, regardless of where he went, he would never have it as good and that his chance to fulfill early promise would never return. Obsession can be good for elite athletes and most of them have something compulsive that drives them to be the best but when your own ambition is holding you back from realising your potential, you need to take stock. Suarez did just that and he eventually left Barcelona but only after Frenkie de Jong arrived and his hopes of game time were slashed even further. With Valencia and other clubs in for his signature, he made the more sentimental choice by moving back to Celta, the team where he spent his youth.

He has played 270 minutes so far this season, which is more than he managed in six months at Arsenal and the previous six at Barcelona combined. He’s almost half way to his total in La Liga from two years ago too. Celta and Escriba trust Suárez to be a catalyst in midfield and he is already repaying the faith they have shown in him.

Celta Vigo have one of the freshest, most vibrant, young midfields in La Liga. Fran Beltrán is still a kid. Stan Lobotka is not much older and Brais Mendez is on track to become one of the finest central midfielders in Europe. Adding Suárez was meant to keep the age down, inject some hometown talent and a player for the fans to get behind, add a dash of dribbling ability from the left and a sprinkle of playmaking too. He was meant to be an ancillary piece. Instead, he has become the fulcrum of the team, the link between midfield and attack, the man that unbalances opposition and the man who should make it a lot easier for Iago Aspas to find space to do damage.

That was the whole idea after all. Celta's big task was either replacing Maxi Gomez or rebuilding the team so he wasn't missed. They replaced him with a man named Gabriel ‘The Bull' Fernandez but Gomez’ ability to create a black hole around him into which defenders seemed to disappear is second to none. The now-Valencia striker was the perfect remedy to teams keying in on Aspas. In his 75 games with Celta, he scored 31 goals. But he needed Aspas as much as Aspas was helped by him as the pair worked well together and not as effectively alone. Simply put, the centre was never going to hold for Celta with such a reliance on the health of such a small fraction of their team.

The signing of Suárez, along with a loan deal for Rafinha, has completely changed the midfield and given Fran Escriba, a loyal purveyor of the 4-4-2, options in his midfield and attack. There are no classic wingers in the team with Pione Sisto, a player whose star looked to be rising, shunted to the bench in favour of Suarez and only used now as a change of pace and when all other avenues of progress have been exhausted. Sofiane Boufal, a player who left you more frustrated than satisfied after watching him play, has left for Southampton. Riyad Boudebouz was also tried as the left midfielder when Escriba took over and Emre More too but they never fit and have both moved on too.

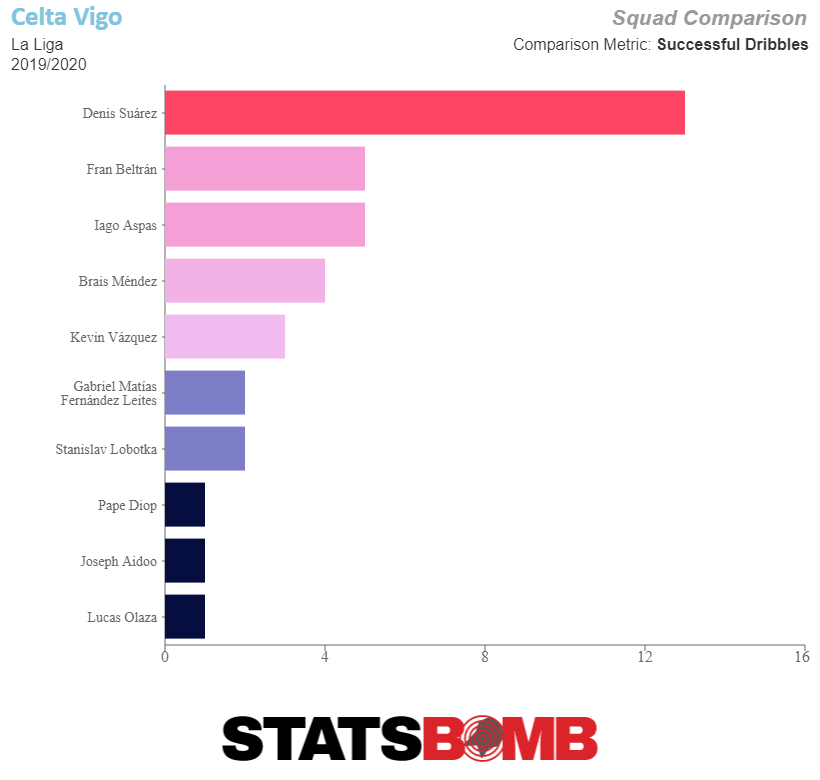

Occupying a space on the left, Suárez is willing to drop deep, roam into central positions and join the attack as a versatile and technically excellent midfielder. His 13 successful dribbles is twice as many as anybody else on the team.

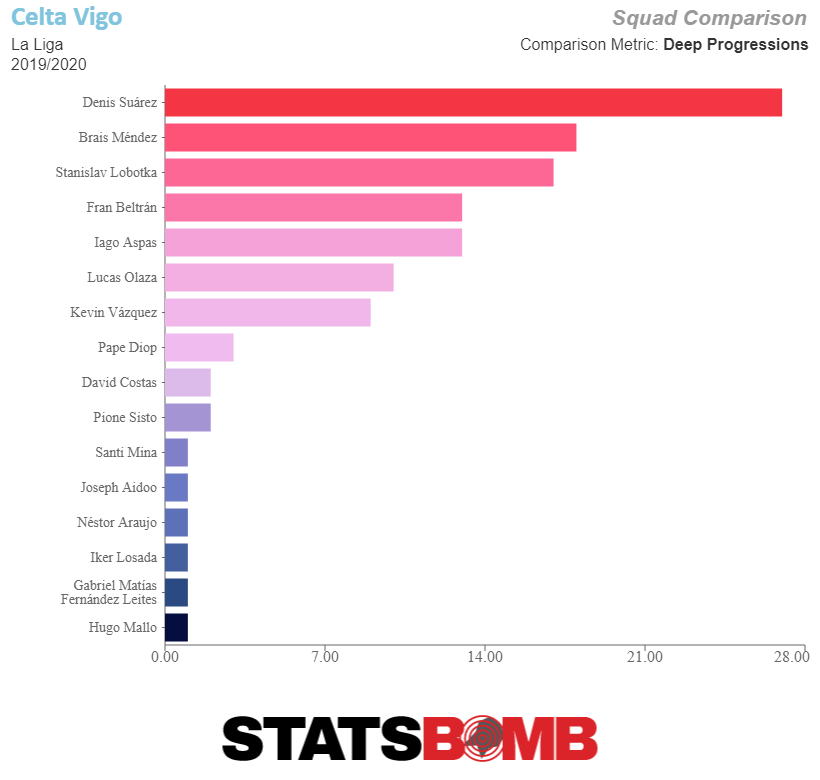

He’s also the team’s most important ball progressor and his 27 deep progressions make him Celta’s most frequent engine to get the ball into the attacking zone.

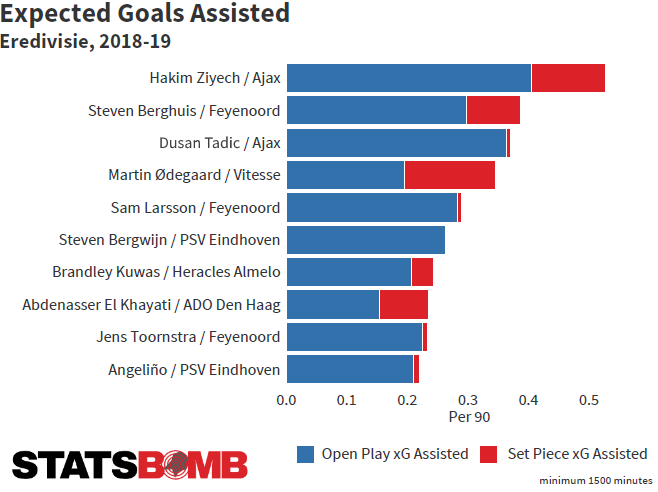

There’s an argument to be made, and a very strong one at that, that Denis Suárez has been the most influential midfielder through three games in La Liga. Although with so few games played it’s unwise to project his performances forward, what he’s accomplished in the young season is remarkable. Those 13 successful dribbles work out to 3.94 per 90 minutes, the second most of any player with 200 minutes played. The deep progressions work out to 8,19 per 90, 14th in the league (though if you’d like to see an example of how early numbers skew things, four of the top five ball progressors in La Liga at this point play for Barcelona). And finally his 0.26 expected goals assisted per 90 is the third best total at this early point in the season. The fixture-makers have not been kind to them either. They have already played Real Madrid, a game in which he excelled as Celta’s most dangerous attacker despite the team’s 1-3 loss.

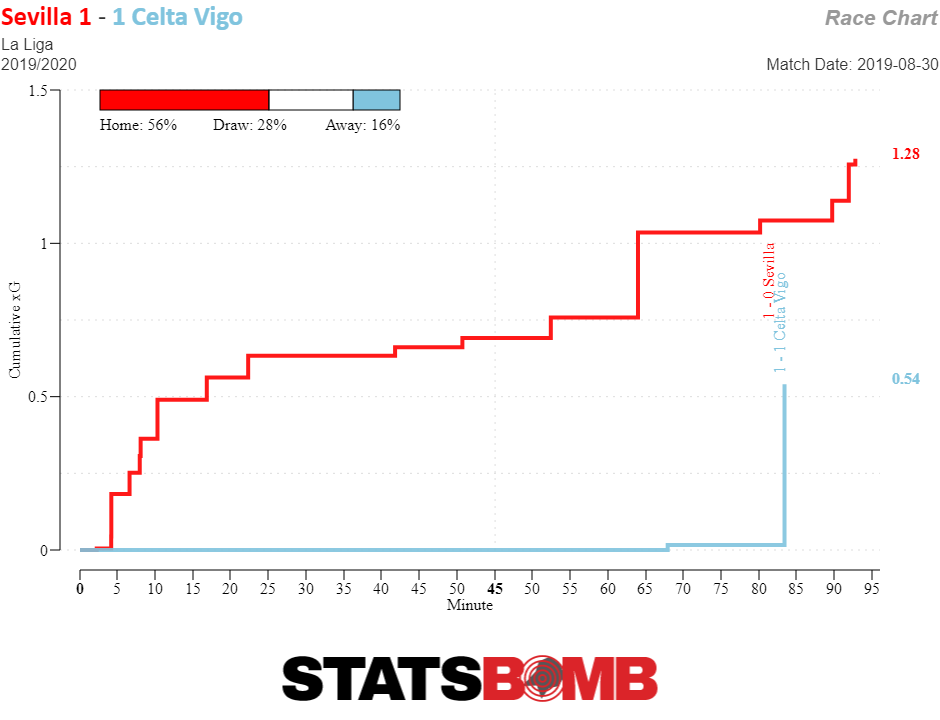

He starred against Valencia, a game in which he was man of the match, and converted the stoppage time penalty to win the game, and Sevilla, a game in which he scored the equaliser after Celta had created literally nothing for the better part of 85 minutes.

Naturally those two goals have been drawing the attention, but they are are also the only two shots he has taken this season. It has been the rest of his play, the creativity both to move the ball up the pitch and in the final third that has really set Suárez apart.

With no number 10 to focus on, Celta have to bypass midfield, meaning Suárez and Mendez on the wings are both controllers of the game and the main source of creativity with Aspas playing off the main striker. The scope of their roles is broad, their ability to fulfill their remit has been faultless to far.

Fran Escriba has rattled a tune out of his several new players early on. He has to integrate Rafinha into the fold now too and is yet to find a place for Santi Mina, another versatile Vigo-born player. Aspas, who is now 32, was being held together with matchsticks by the end of last season as he helped them stave off relegation. He can rest assured that this season there are enough players around him that will lighten his load so he can be decisive late in the season and late in games when they are likely to need him most.

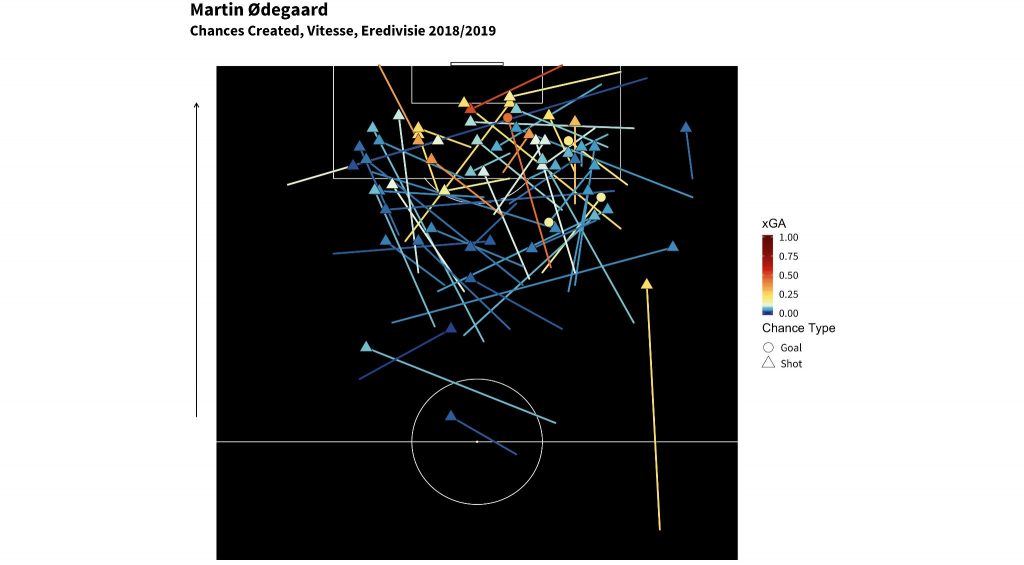

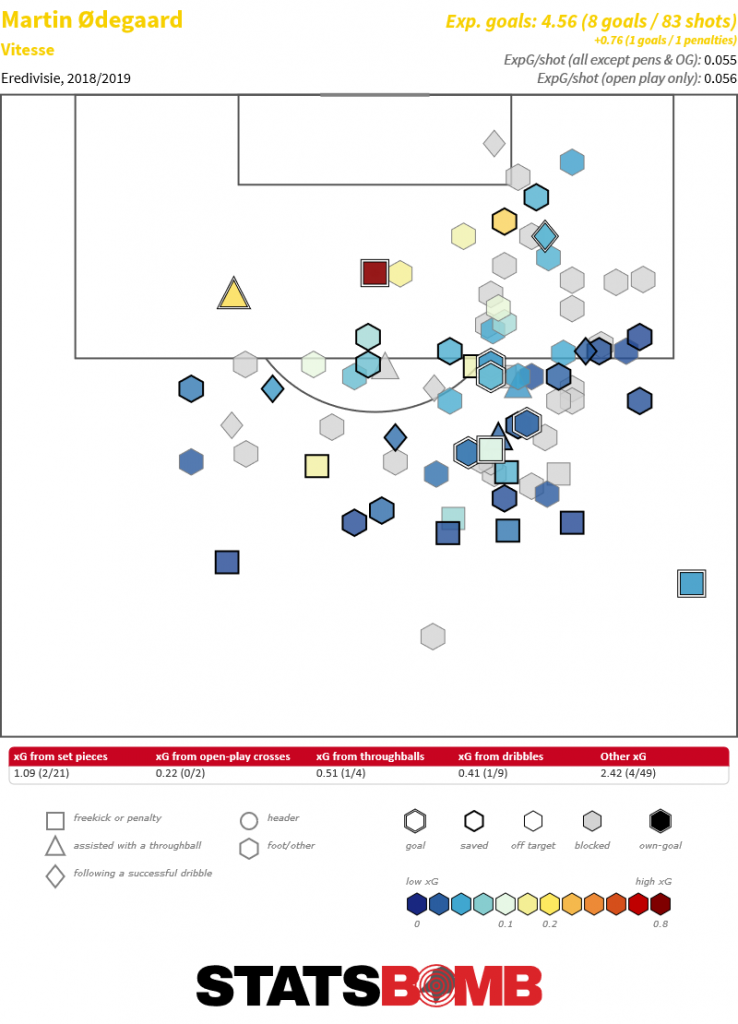

How Martin Ødegaard Got His Career Back On Track

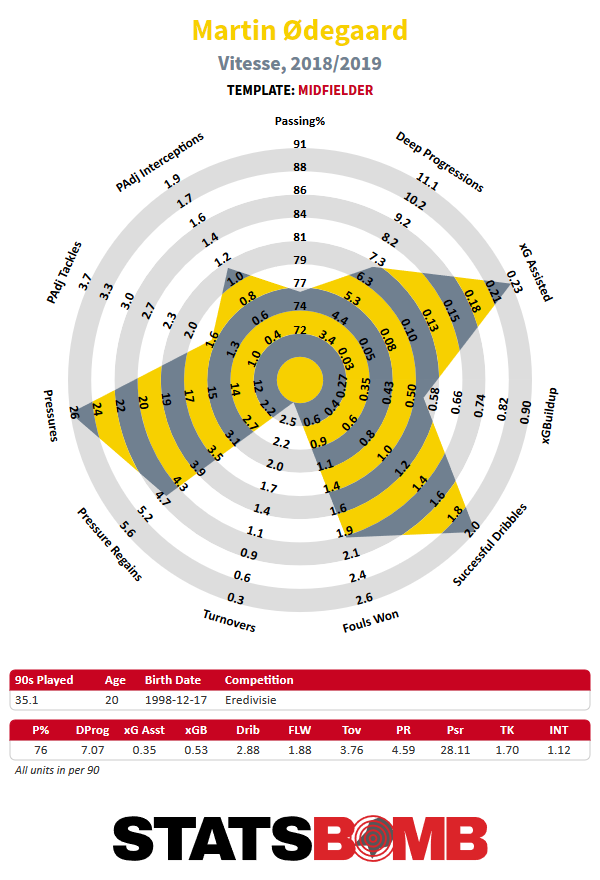

The mental change that has transformed Martin Ødegaard from lost talent to decisive playmaker resembles the one that helped Zlatan Ibrahimović step up his game.

The year was 2004 and the Swede had joined Juventus from Ajax, where he had averaged about a goal every two league games. That wasn’t good enough for Fabio Capello, the Juve coach, who told him that he was going to knock the Ajax style out of him. What Capello wanted was fewer tricks and more goals, so he put Zlatan through relentless shooting drills. The drills flicked a switch. “A little of Ajax has stayed with me – the quality,” Zlatan has said. “But even if I now play out of the area more and always look to do the kind of move that motivates me, the first thought I have is to score and to win. That’s Capello’s lesson.”

A similar decisiveness has galvanised Martin Ødegaard, the Norwegian wunderkind. When Ødegaard joined Real Madrid at the age of 15, he began to flounder in the reserves, and the comparisons shifted from Lionel Messi to Freddy Adu. But at 20 Ødegaard has returned to Spain with Real Sociedad, whom he joined this summer on a two-year loan from Madrid. The playmaker has become a key cog at La Real after two games and struck a late winner at Mallorca on Sunday. While his touch is as silky as ever, his approach has changed since those troubled days in Madrid.

Back then Ødegaard arrived as a mini galáctico, having toured Europe with his family in search of a top club. As a kid who had danced around defenders twice his age (and size) in the Norwegian top flight, Ødegaard could pick and choose. Alongside his father, Hans Erik, a former professional footballer, he opted for Madrid, who told him that he would train with the first team and play for Castilla, the reserve team, who had just slid to the third division. Florentino Pérez invested a lot of time and personal prestige in luring him to the capital, and when Ødegaard touched down in January 2015, Madrid presented him in front of the press. Then the season turned into a disaster.