Thanks to a strong finish, RB Leipzig have secured Bundesliga’s imaginary autumnal championship called “Herbstmeisterschaft” in German and start the second half of the season as league leaders. What distinguishes the team? And where are its vulnerabilities?

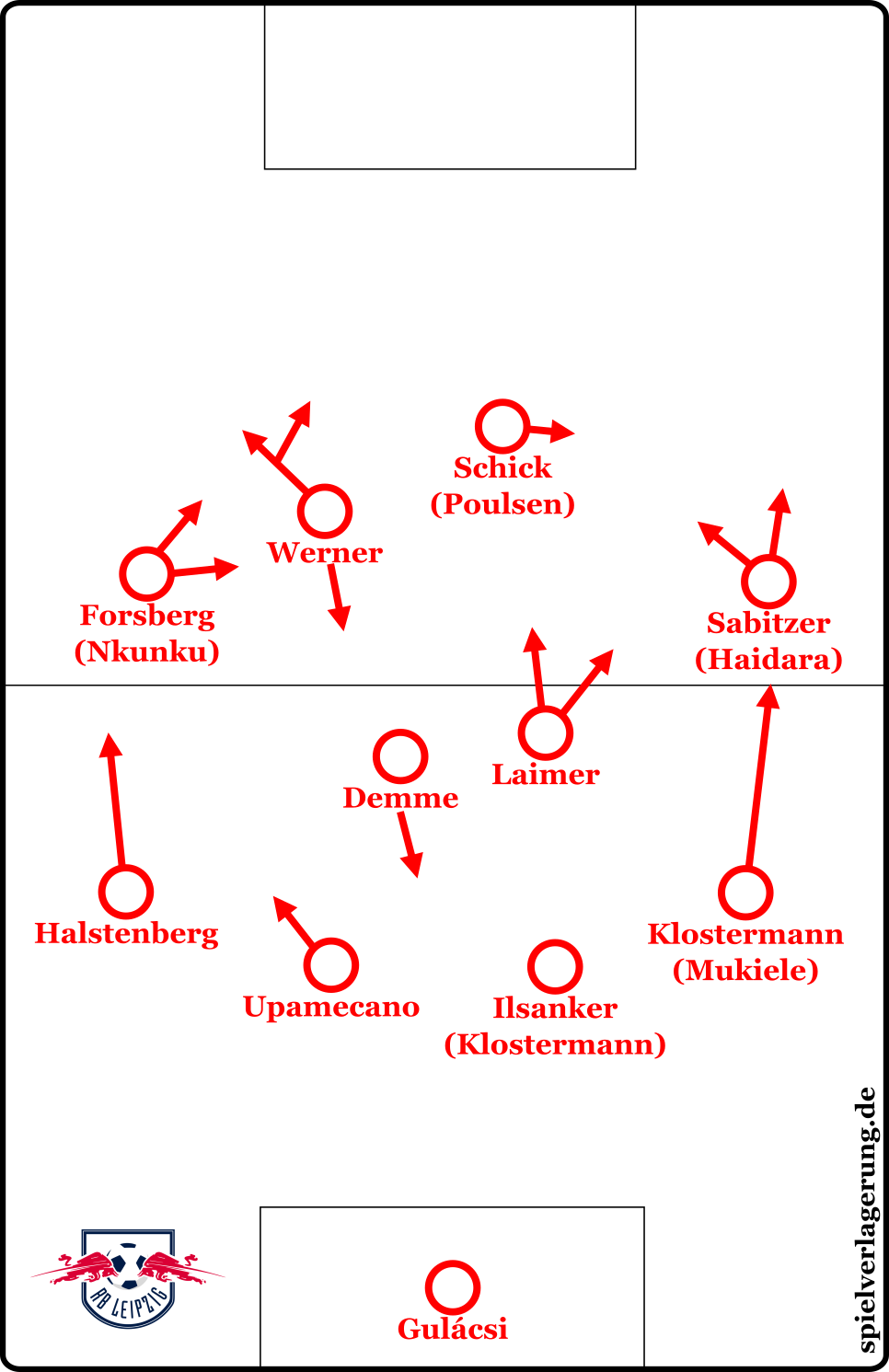

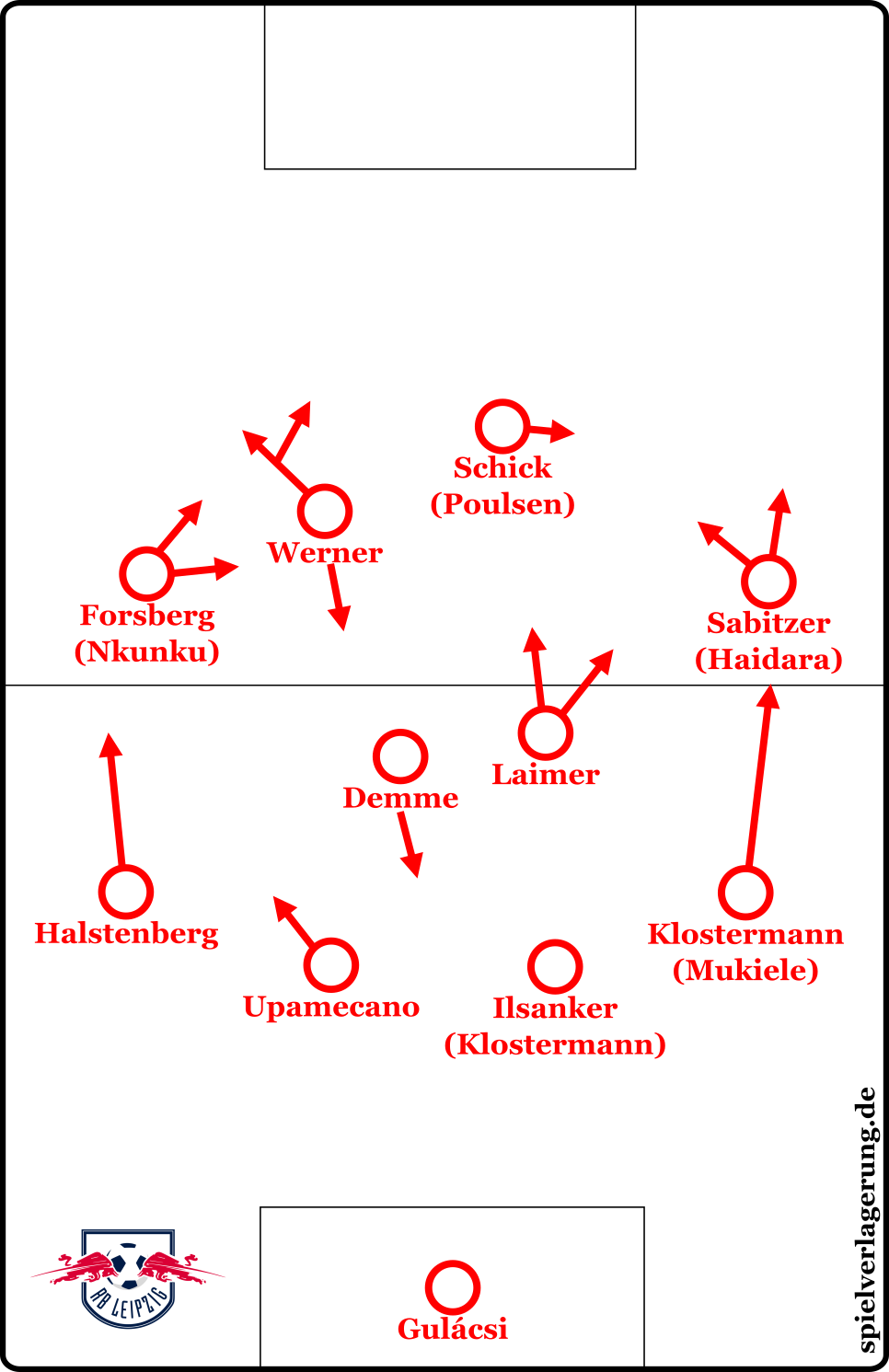

The last five Bundesliga games ahead of the winter break largely serve as the foundation for this analysis. In these, Leipzig without fail played in a 4-4-2/4-2-2-2 formation which has once again become the customary formation of the team after an asymmetrical 3-5-2 had intermittently been used.

Attacking organisation

On the whole, Leipzig show themselves, especially in games against visibly inferior teams, to be a dominant unit that has developed confidence in its qualities in possession. In that way, this differentiates this Leipzig team from the ones in previous seasons in which the possession game seemed less competent.

The first build-up phase, typically starting a few metres ahead of their own penalty box, is coined by a distinct calmness. The central defenders aim to establish this phase of the game with initial passes and thus prepare a move without hastily forcing an attacking passing lane. Instead, the first passes go toward one of the central midfielders or fullbacks without those passes carrying much consequence.

The most common move entails the ball being played to a full-back, who forwards it diagonally to a winger who has moved inside. From there, the ball is either laid off to a team-mate behind or around him or the player opens himself up into the open space. The fullbacks, though, differ from each other in terms of their play-style and positional characteristics quite severely. Lukas Klostermann, for one, is someone who wants to make forward runs early, while Nordi Mukiele hangs back much more often and thus receives more touches of the ball in the first build-up phase.

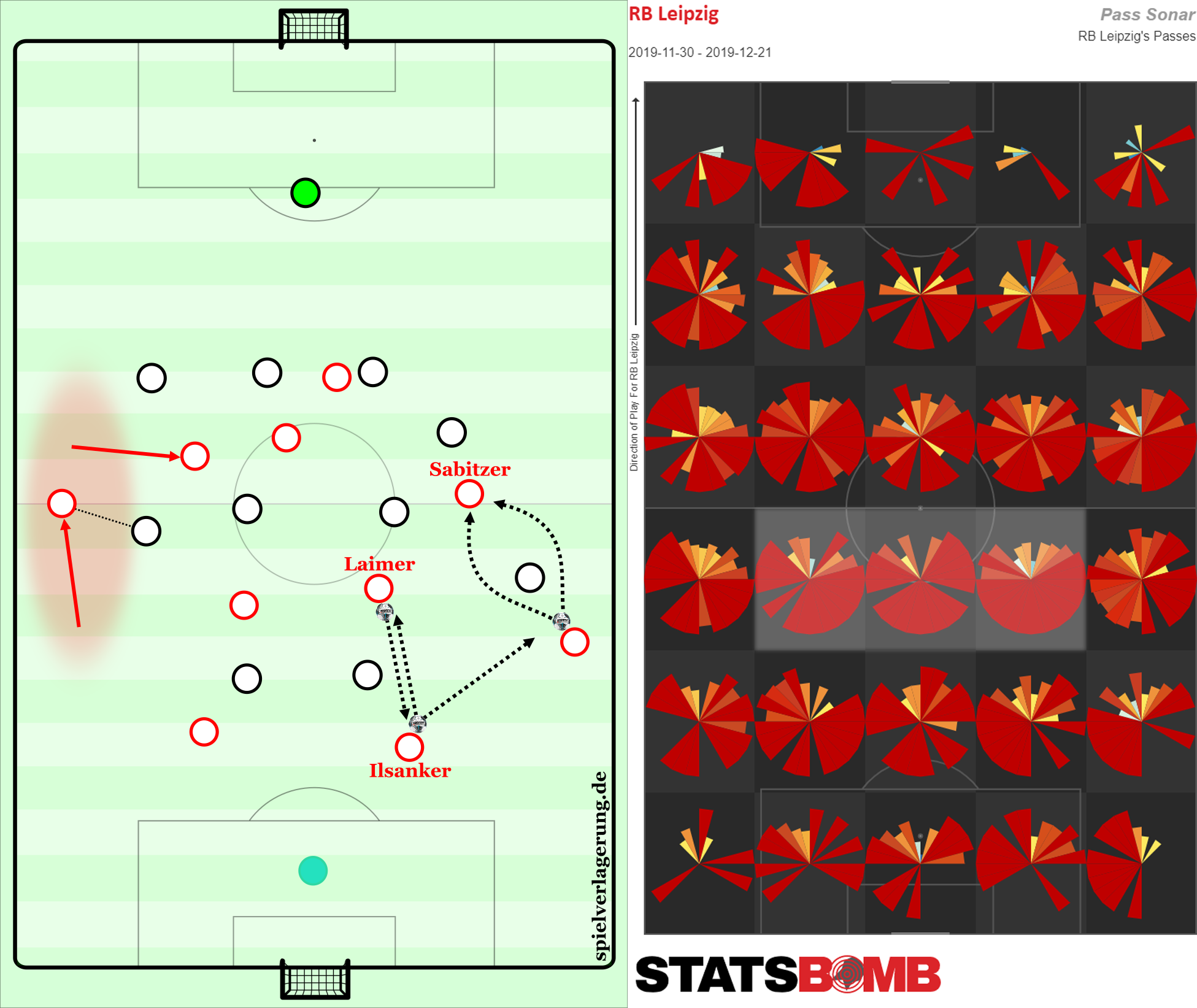

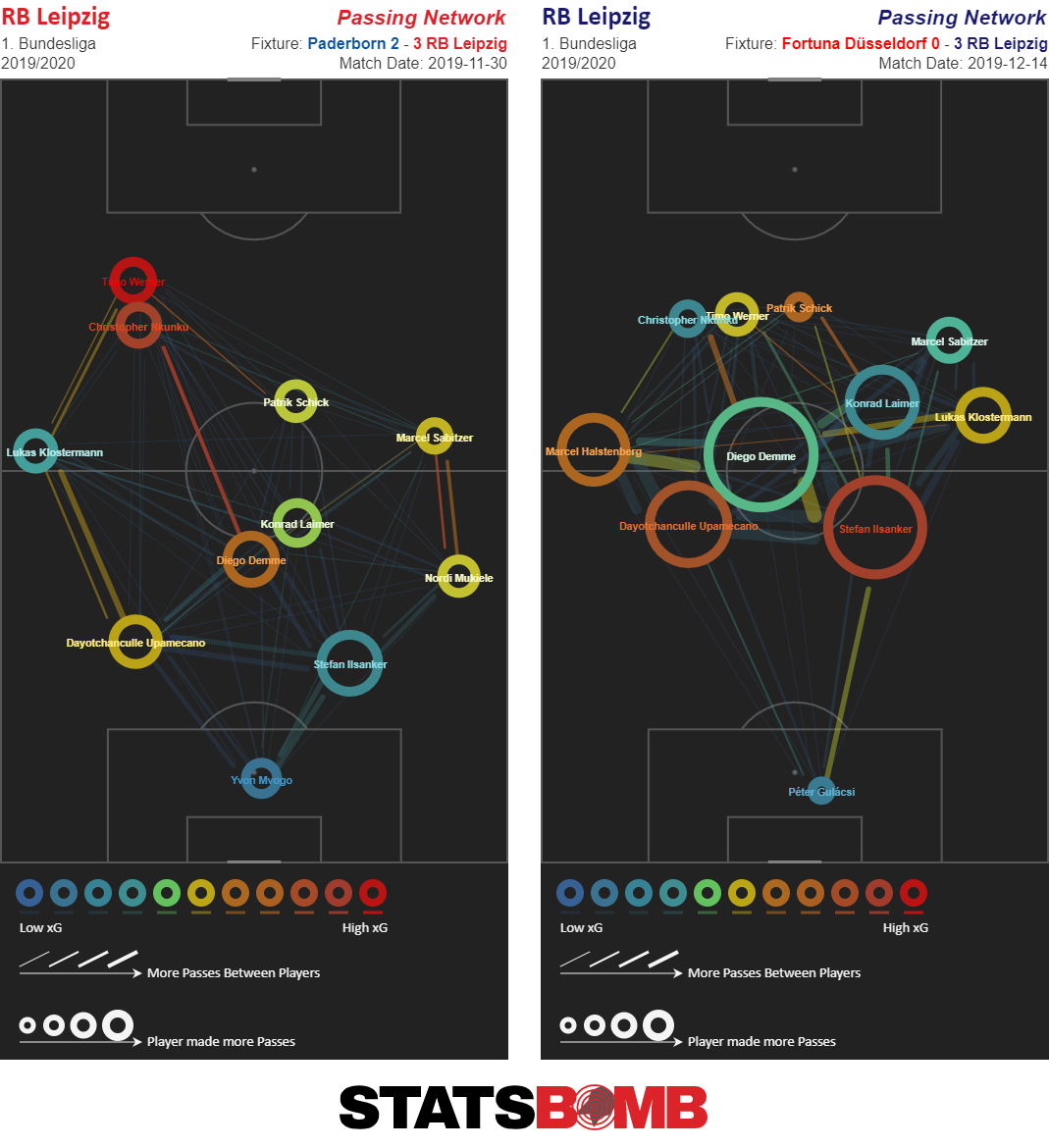

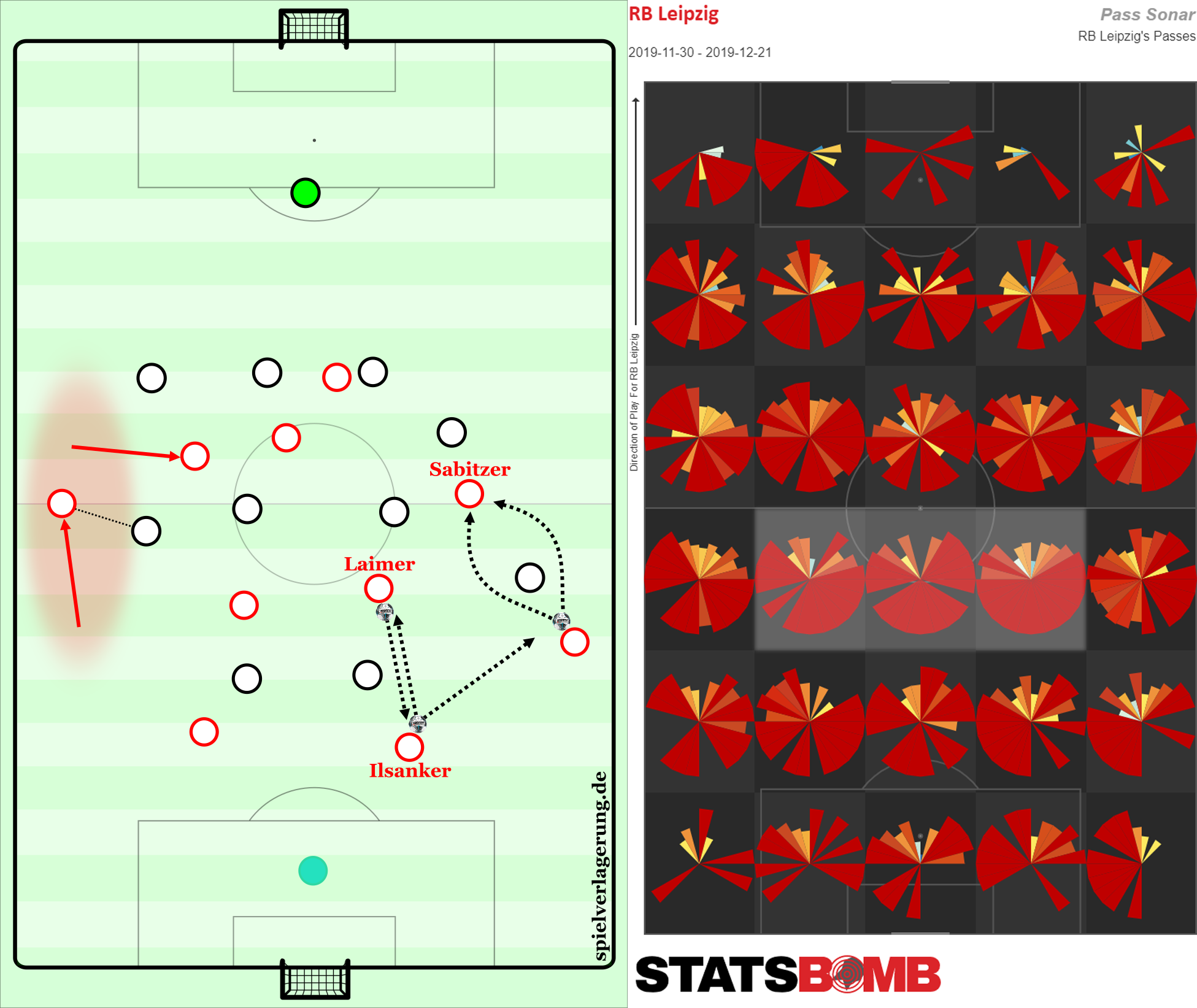

This is how Leipzig's initiating of play presents itself. The Pass Sonar underlines how the central players at the halfway line—most commonly the central defenders—rarely play vertical passes into the attack, rather shifting play toward the wings.

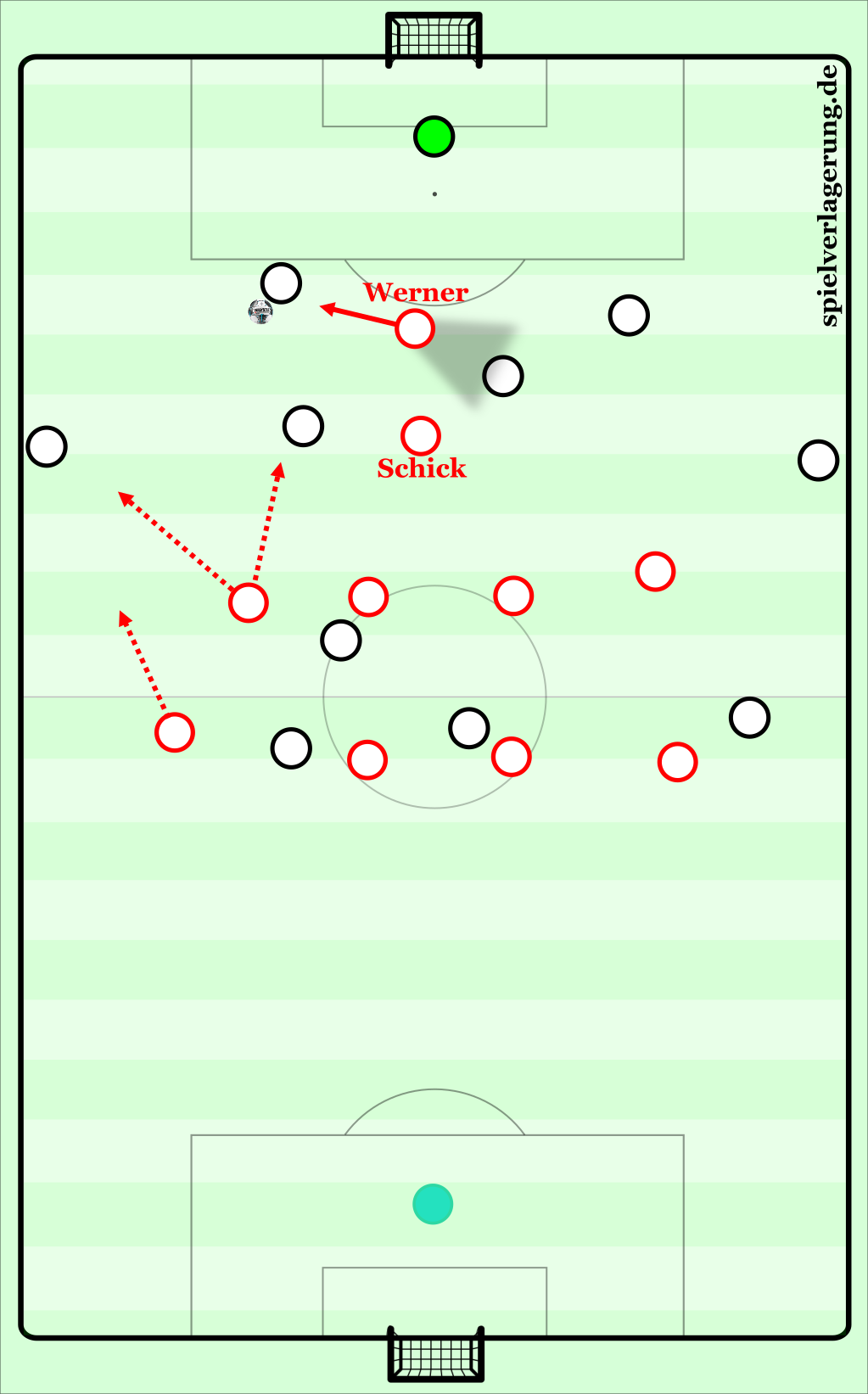

Furthermore, the two holding midfielders serve different functions. Konrad Laimer clearly is the more attacking-minded of the two central midfielders which expresses itself in his aggressive advancing up the pitch. Laimer works very well as a receiver for the aforementioned layoffs from one of the wingers—in this case the right winger. On the half-left side, though, Diego Demme hangs back further and so covers the space behind. Instead, it is Timo Werner who moves toward the left side and thus offers the left winger an option to forward passes to him. Thus, while Laimer is actively looking for tight spaces and high-pressure situations, Werner attempts to evade the tightness and to penetrate the opponent's defensive formation from the flank.

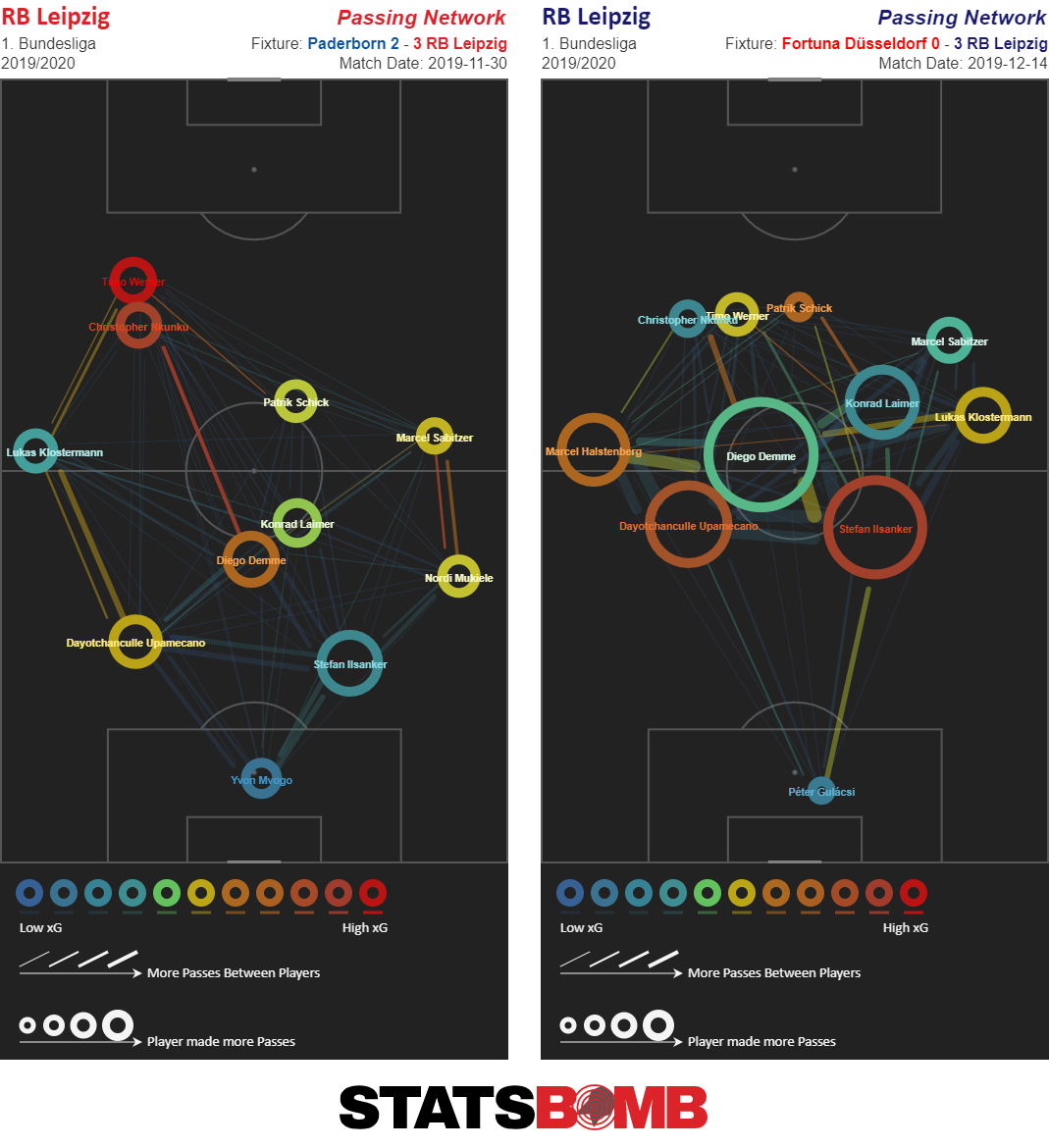

The Passing Network and Average Positions illustrate the diverging roles of players in the position groups. Klostermann is the full-back that advances higher. Laimer most often pushes forward a bit from the half-right space. Comparing the wingers, Nkunku typically chimes in more concretely in the No.10 space.

Occasionally, Demme will produce a different build-up structure by dropping between the centre backs and thus automatically pushing the fullbacks a bit more forward. When the wingers move inward more quickly accordingly, this opens a lane for Klostermann, for instance, who can use it to sprint and receive the ball at full speed.

As attacks develop into the final third of the pitch it becomes apparent how Leipzig use simple, but well-thought-out, positional play. The wingers usually move inward with the left winger adapting himself to the movements of Werner, who himself can also fall back into the half-space. The inward movement of the wingers and the advancing runs of the full-backs create a consistent staggering in terms of width, without it becoming too flat thanks to forward and backward movements within the lanes themselves.

This GIF shows the processes when Leipzig can advance into the opposing half without much resistance, which happened time and time again in the win over Düsseldorf, for example. 1) Werner presents himself in the half-space and does not evade toward the left flank due to limited space. 2) Sabitzer and Forsberg or Nkunku shape their runs toward the middle or into the points of intersections based on personal preferences and in adaptation to the strikers' movements.

On the whole, Leipzig create a strong presence at the points of intersections even against a back-five and thus occupy the entire back line. 3) Both full-backs use the open wings for runs and at times position themselves at the offside border, thus occupying their immediate opponents. Alternatively, one of the full-backs receives an uncontested pass. 4) The four-man block in behind is responsible for coverage and can transition into Gegenpressing in case of a loss of possession.

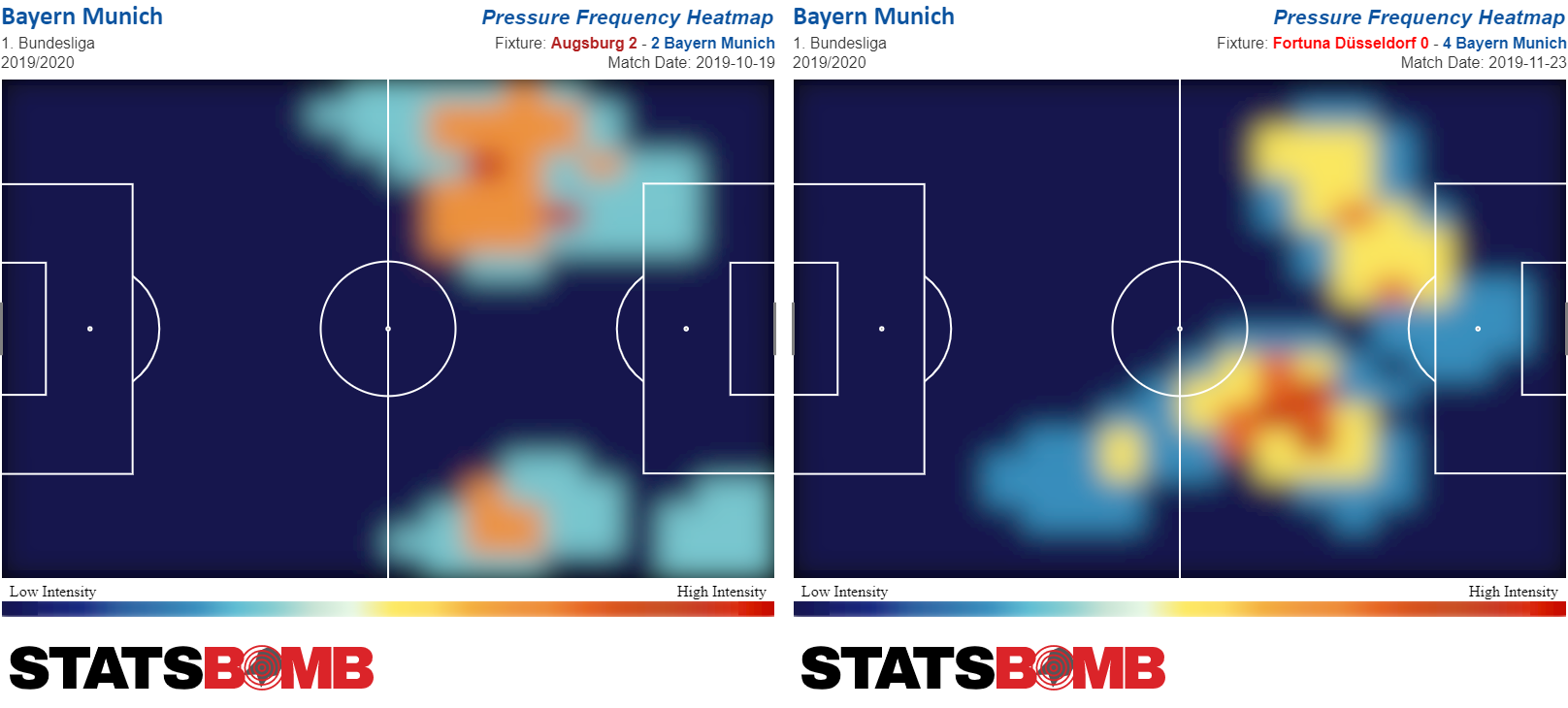

Defensive Transitioning

Typically, Leipzig are able to avoid being surprised by counters after losses of possession deep in the opponent's half. Often times, singular proactive movements from the defenders prove sufficient, with them looking to duel with the intended receiver of a long ball and thus pushing him off the track. In situations in which Leipzig give up the ball a short way ahead of the box and centrally, usually one or two players immediately behind will step in. On the right side that might be Laimer and Sabitzer who are in close proximity to the ball anyway. High pressure on the opponent is being applied especially ahead of the halfway line, so that there is little time for decisions and the new ball-carrier cannot even get into position for a long shifting pass.

Looking at them individually, some players behave differently in defensive transitioning. Laimer, for one, is an aggressive defender, whereas Demme is a man-orientated pursuit-player, mostly trying to eliminate his direct opponent as a receiving option. When losing possession at the halfway line, and thus in situations where only defenders will be behind the ball, the back-four typically moves back toward its own penalty box in orderly fashion and also moves closer together in an attempt to fend off potential crossing attempts in the middle and not to let potentially fatal holes develop by going into early duels.

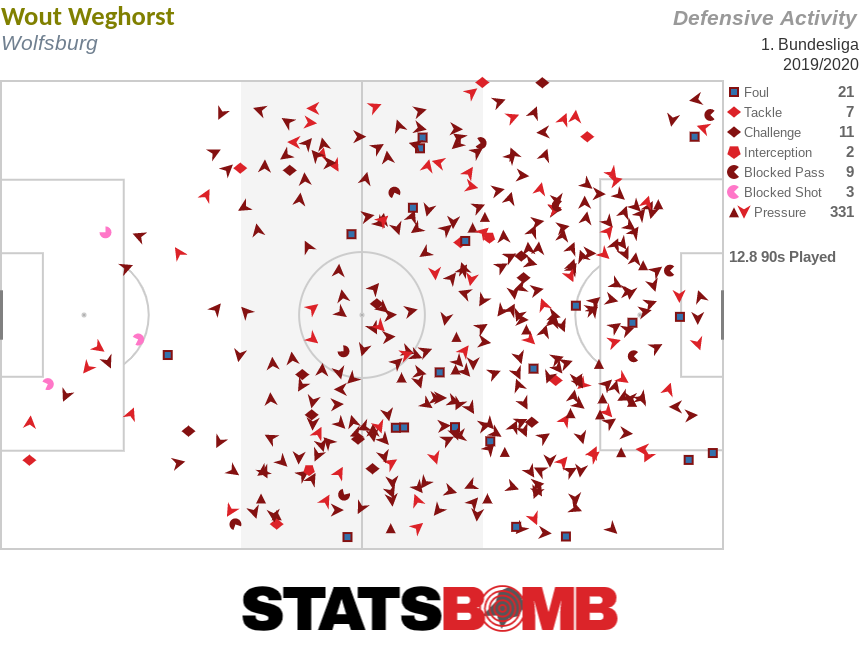

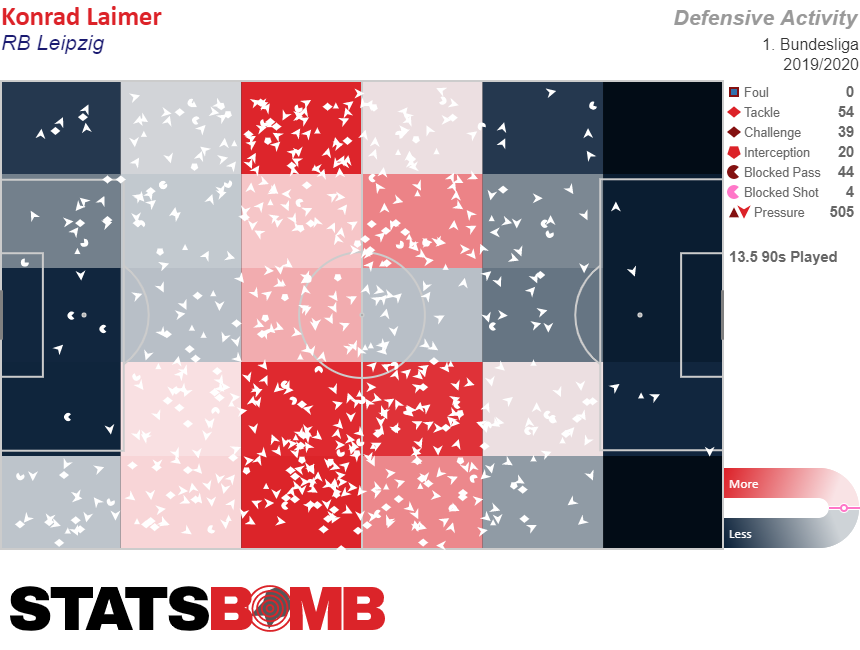

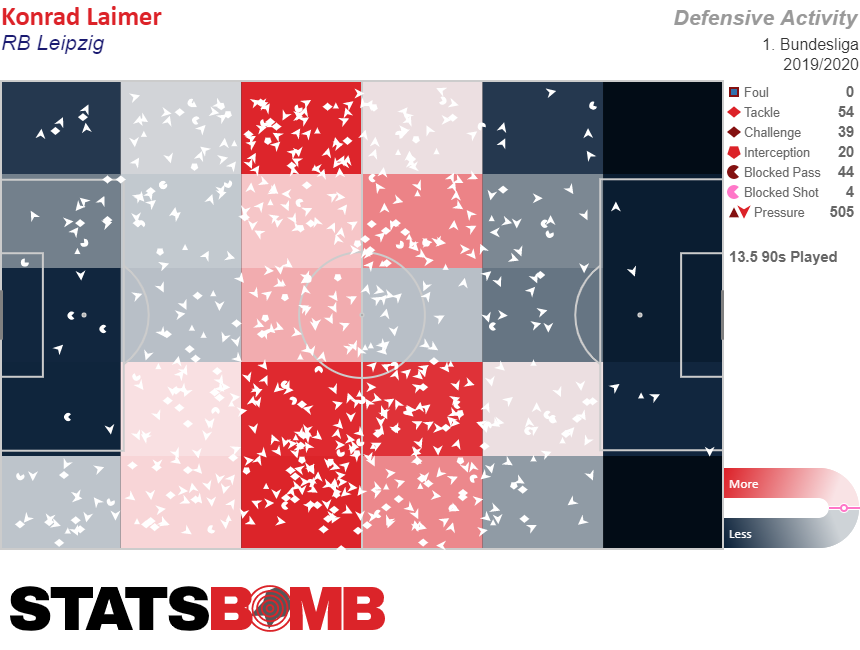

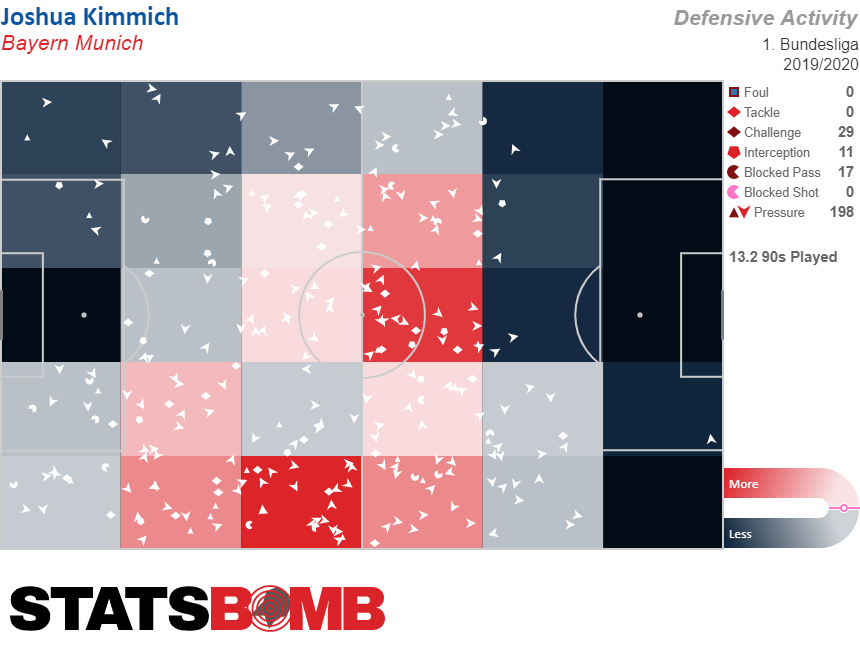

Laimer's Defensive Activity over the entire season thus far shows how he behaves quite dominantly on his usual half-right position. The picture is slightly distorted because he played a number of matches on the right wing.

Laimer's Defensive Activity over the entire season thus far shows how he behaves quite dominantly on his usual half-right position. The picture is slightly distorted because he played a number of matches on the right wing.

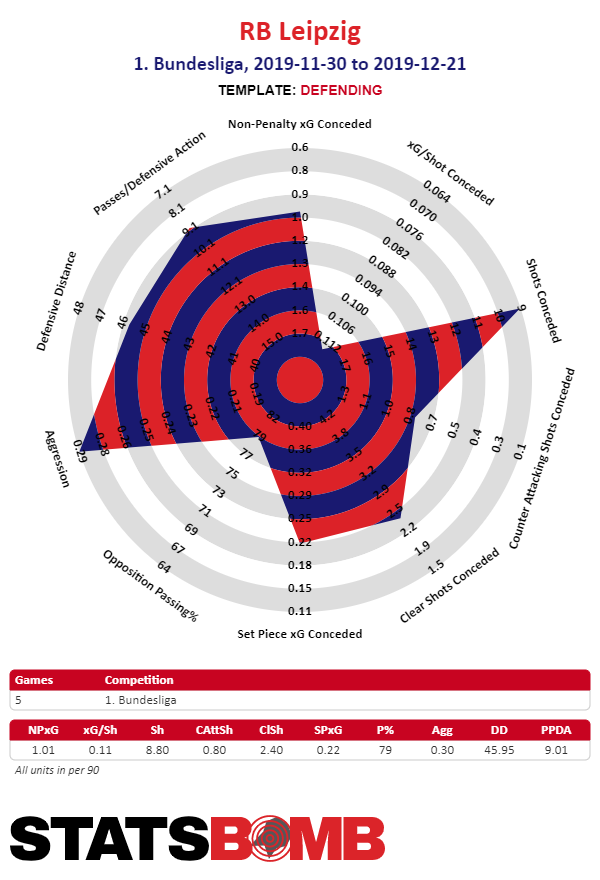

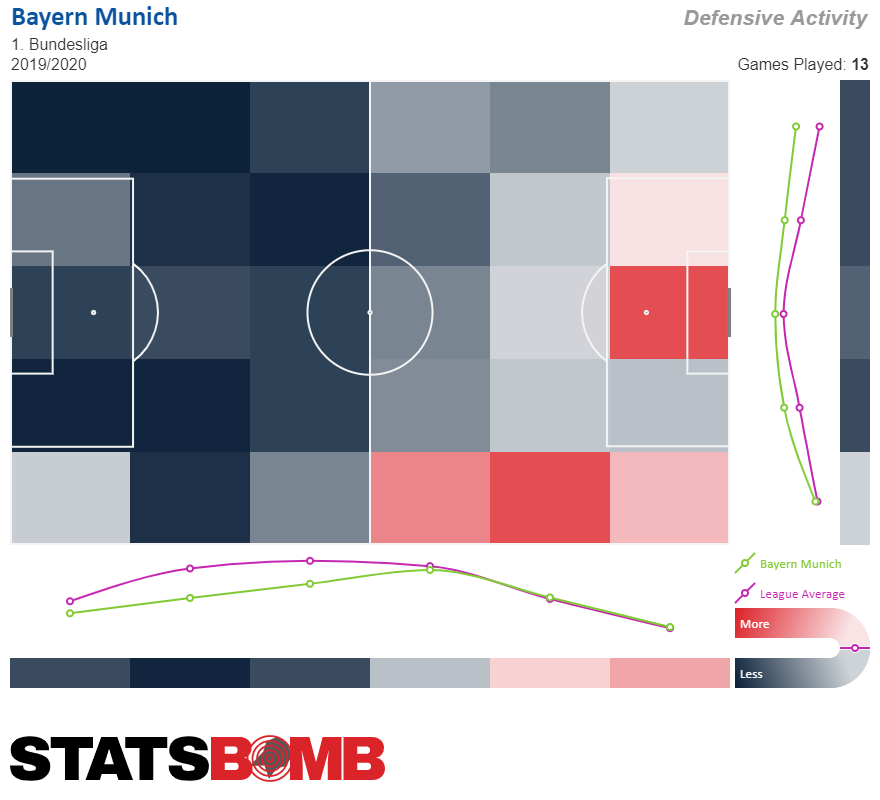

Defensive Organisation

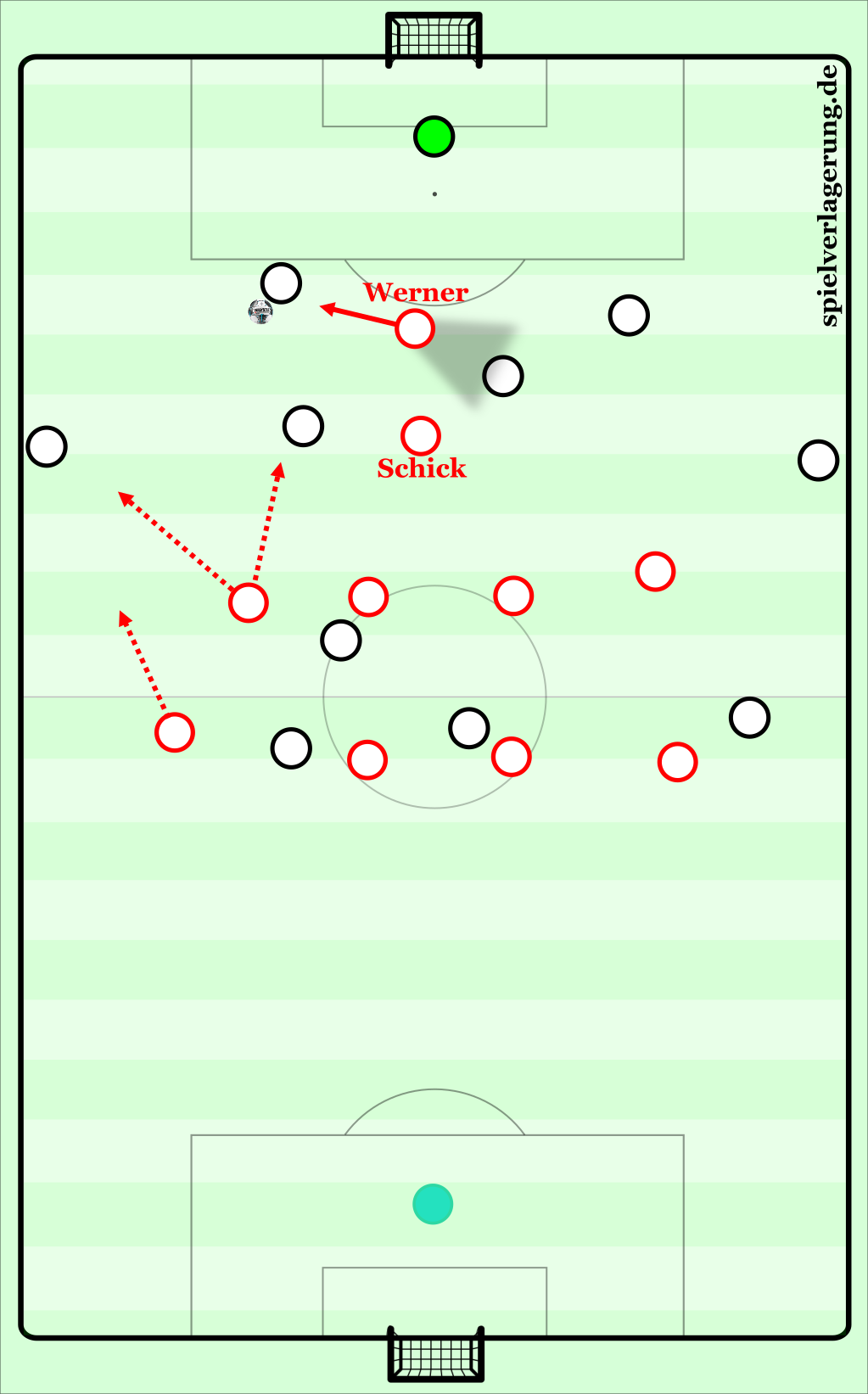

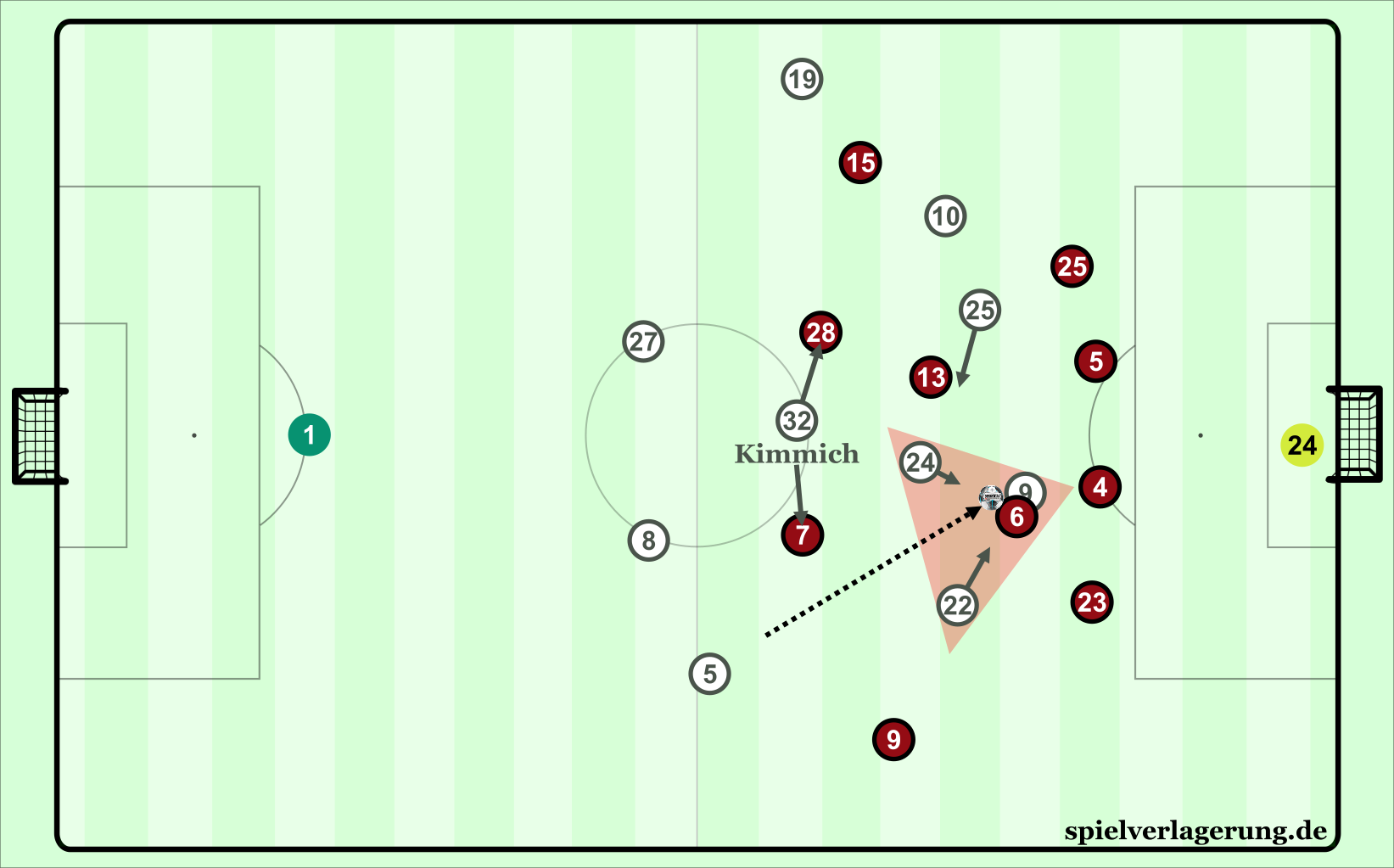

Against the open build-up play of the opponent, so, when they build-up in an orderly fashion from the back, Leipzig often play in a 4-4-1-1/4-2-3-1 formation. The allocation of the two strikers at times will adapt to the opponent and may even vary within games slightly. The players have some liberties in these aspects. Interestingly, in the 4-4-1-1 it is not rare for the more physical Patrik Schick to be positioned as the temporary No.10 and stay in proximity of the opponent's central midfield. Werner is then being used further ahead as a runner who tries to push wide-standing centre backs toward the flanks and to guide passes that way as well.

The flanks, though, are not being defended head-to-head. Especially in the 4-4-1-1, Leipzig's wingers are positioned more centrally in the midfield line and only move in on the opponent when he receives the ball, in order to prevent an uncontested diagonal pass forward. Leipzig's central midfielders, in turn, are typically man-orientated when an opposing player pushes forward through the centre in an attempt to present himself as a receiving option behind the halfway line.

Leipzig's pressing structure in the 4-4-1-1 distinguishes itself by the staggering between Werner and his striking partner as well as the adapted movements of the wingers who will orient themselves either to the full-back, a dropping holding midfielder or even one of the opposing centre backs.

Sporadically, Leipzig's defenders in the back line tend to pursue dropping movements from the wingers or central strikers, thus abandoning space at the offside border. This can take its toll, however, when another opponent runs into the space behind the defender for a layoff pass from a winger or central striker. Most of the time, the defenders will abort their pursuing runs in time, but a certain, albeit small, risk of danger remains.

Leipzig's defensive problems are, in fact, larger when the team moves back in a 4-4-1-1 or a 4-4-2 and tries to defend while using a low press. The statics of Leipzig's defensive formation are then a curse for the team, since it only rarely allows immediate access, instead turning into a passenger when the opponent turns to quick passing moves. Leipzig live off their strength in duels and intensity in proximity to the ball, but they can only develop when the team is in movement. Otherwise, they turn into a relatively simple man-orientated defensive team that is constantly a step too late and only rarely manages to block passing lanes, simply because it fails to disengage from its own man-orientation.

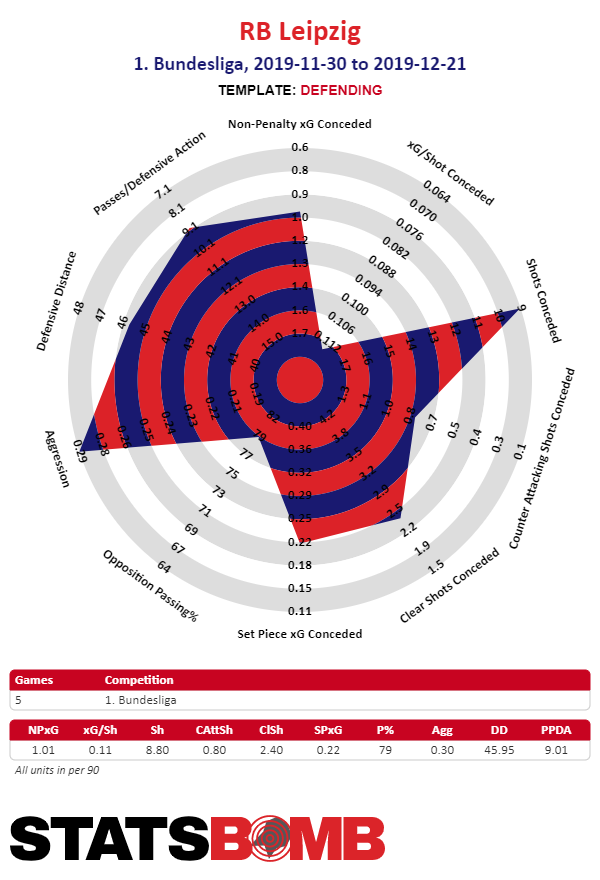

Over the last five matches, Leipzig failed to decisively disturb the opposing passing flow. This was especially true for the games against Hoffenheim and Dortmund. Still the team manages to defend opposing attacks in a way that no shot is actually fired off. Attempts on goal by the opponent mostly are a result from an attempt to play on the counter or from a very inviting position from open play when Leipzig's defence is ultimately beaten.

Building up with a back-three and full-backs that are positioned higher up the pitch seems like an effective means against Leipzig. The full-backs would push Leipzig's wingers back, while the numerical advantage in the first build-up line would allow for a secure passing and, situationally, for advances through the half-spaces. Rarely, Leipzig tinker with their pressing formation in a way that at least one of the wingers moves toward one of the opposing centre backs.

Of course, someone like Emil Forsberg will occasionally make such a run, but usually, high-positioned opposing wing-players and dominance in the early build-up phase should make Leipzig turn to a retreat into passivity.

Offensive Transitioning

The aforementioned structure in pressing, with Schick as a hanging striker, has the major benefit of the Czech being able to immediately function as a pass receiver after winning the ball. Schick is the first target player who can, for example, lay the ball off for a sprinting Laimer. Laimer most often leads the first wave in advancing after winning possession, while the third ball will more often than not end up at the feet of the defenders who themselves move forward. Especially after third balls, the next pass usually is a medium-length ball toward the flanks where, for instance, Timo Werner or Christopher Nkunku will be located to move away from the contracted defence and receive the ball.

Set Pieces

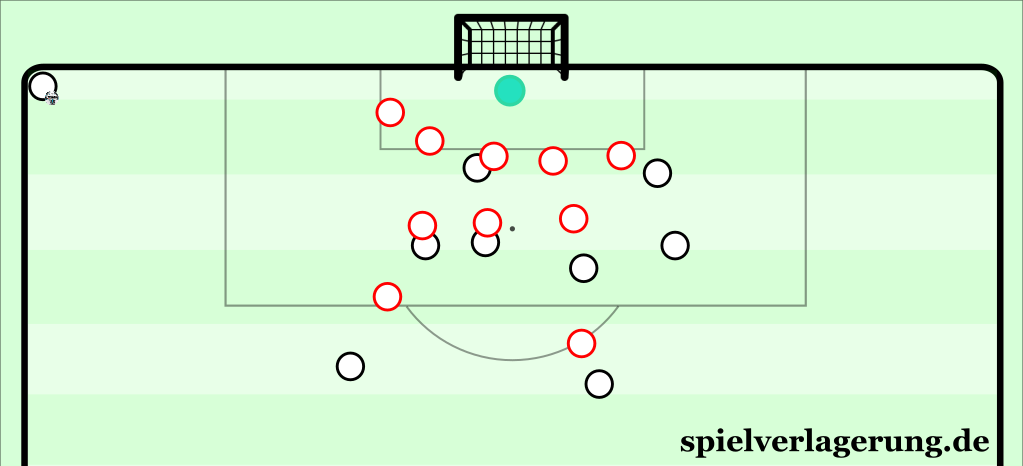

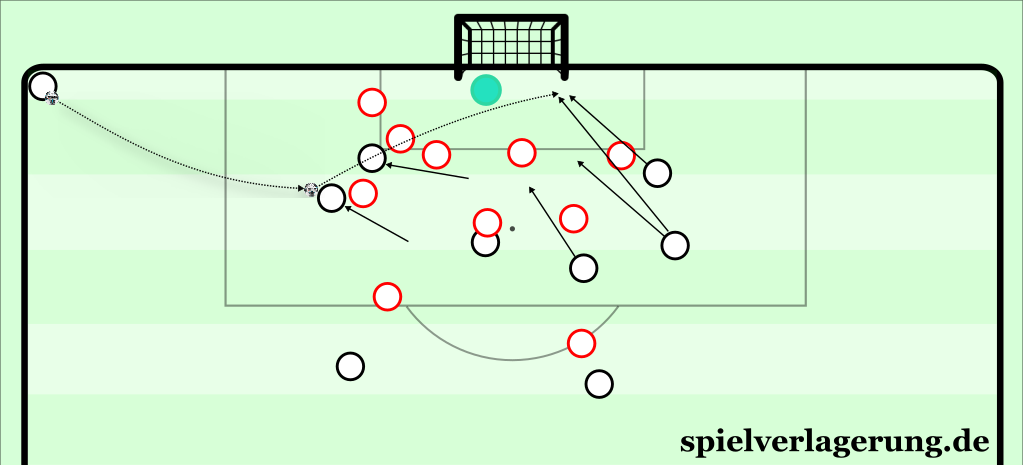

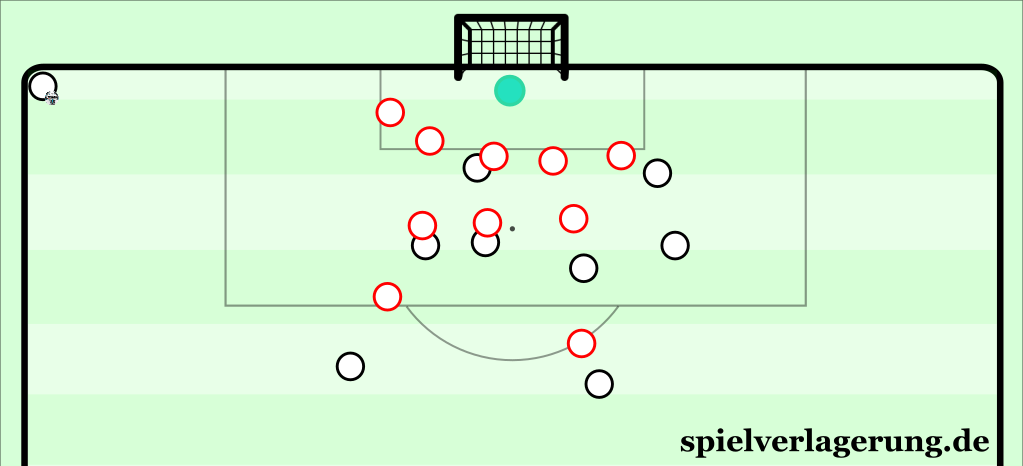

Corners are not necessarily a Leipzig speciality. Defensively, the team again and again seems vulnerable, which is also down to the staggering. Most often, five players position themselves more or less behind one another at the edge of the six-yard box, with one of those five possibly taking on a man-marking task. Ahead of them, there are three more Leipzig players in a tight man-marking scheme, trying to defend against the opponents' runs. Since a number of players are positioned exactly on a line, the inner five-man block can be levered out, for instance with a short corner and a flick-on toward the far post—be that straight-away horizontally or diagonally from the corner of the six-yard box. The block remains static, after all, forming a density of defenders that is restricted in its reactivity.

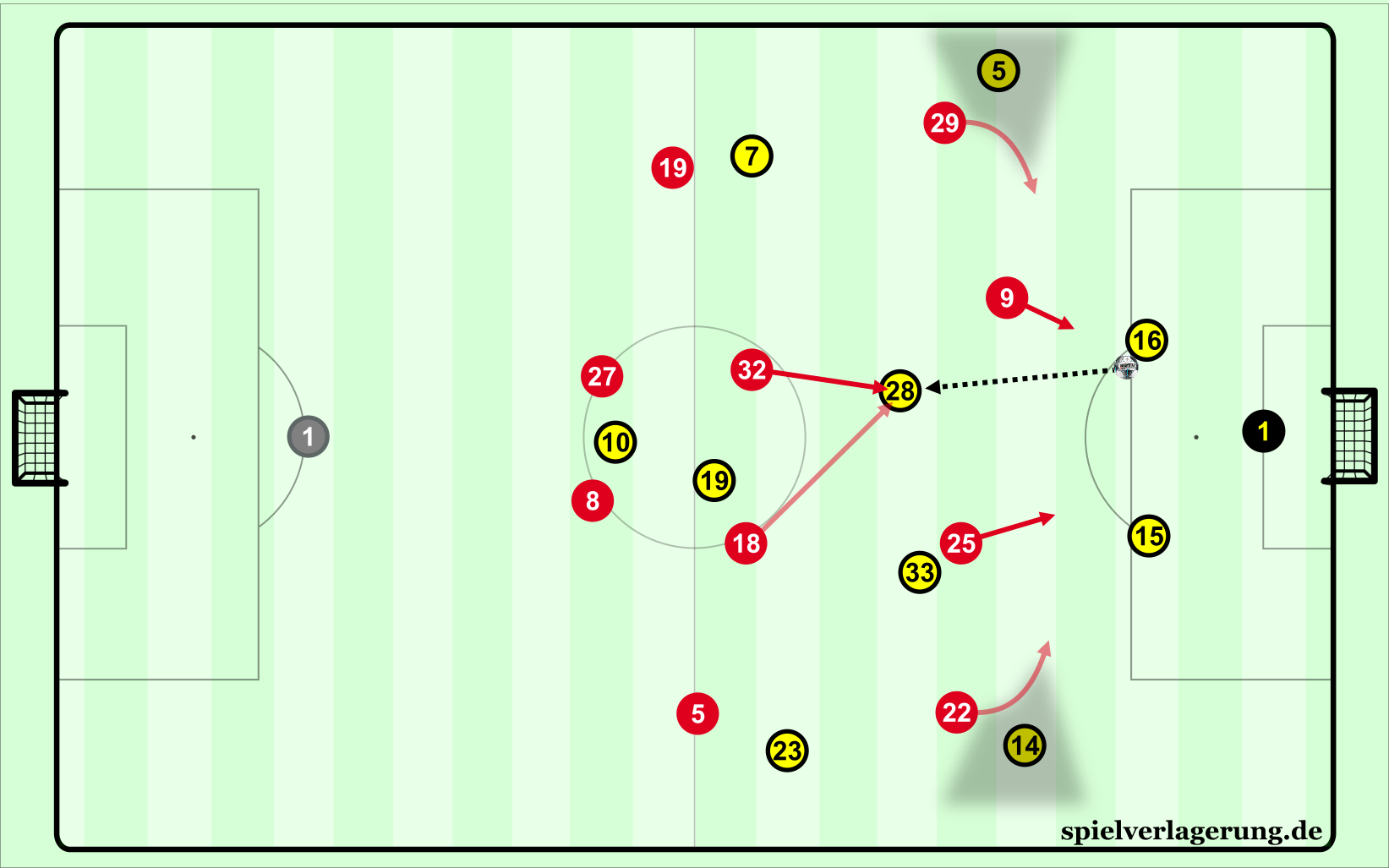

Example of Leipzig's staggering for a defensive corner…

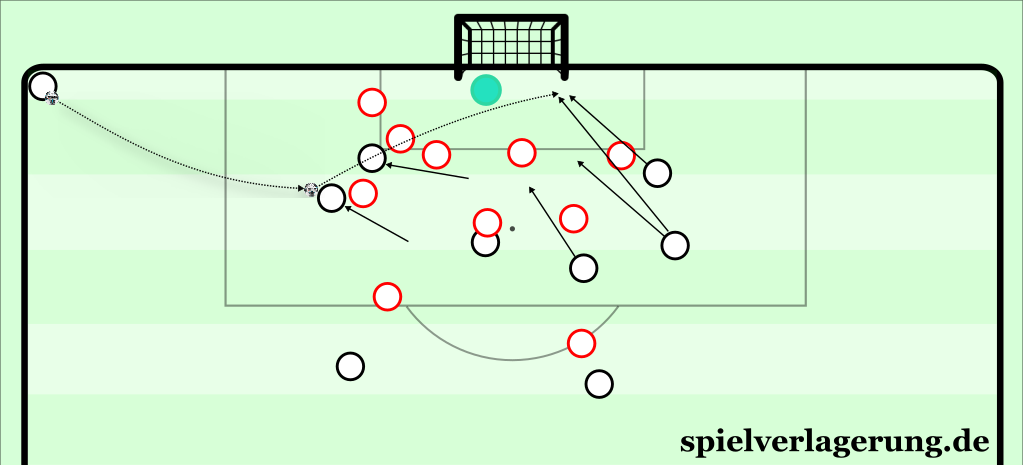

…and how an opponent can beat Leipzig following a corner.

For attacking corners, three Leipzig players may, for example, position themselves centrally ahead of the six-yard box. Three more players stand further back at the penalty spot, with one of them often dropping back from there toward the short side of the penalty box. In other cases, five Leipzig players stand ahead of the penalty spot and run in a diversified manner and in timely accord to the corner's being taken toward the six-yard box. Here, Werner, as the player bringing up the rear in that block, will move away a bit and not make a direct run inside. Another player mimics a run toward the corner flag, however abandoning it when he's pursued. Schick, then again, occupies the six-yard box in this alignment and works as a nuisance for the goalkeeper as far as the rules will allow it.

For crosses from free-kicks in the half-spaces, four Leipzig players will occasionally position themselves in the opposite half-space and start their runs, almost classically, shortly ahead of the offside border. Three more players hang back a few metres and can free themselves for a short pass. Schick, in turn, will sometimes gain more of a head of steam from further back and thus enter the box with more dynamism as long as he is not running into an offside position before the free-kick is being taken in the first place.

Leipzig's major advantage is the pure physicality that Schick, as well as Yussuf Poulsen or Dayot Upamecano, brings to the table for corners. Even from static positions, when they are situated at the six-yard box, they can win aerial duels.

So how do Leipzig distinguish themselves?

- The team no longer lives off only their intensity and speed, even though those elements still play an important role since almost no other Bundesliga team can piece together this many exact passes and receptions at high speeds.

- The many movements within the structure in possession make life hard for man-orientated defensive lines. They also train the passing communication of Leipzig and encourage their intuitive actions high up the pitch.

- Werner more present than ever by not only chiming in on the left side, but also more and more actively asking to receive the ball in the half-space. Spending time as a play-making or heavy-on-touches striker in a 3-5-2 also bears fruit.

- The strength in duels by which Konrad Laimer and also Stefan Ilsanker distinguish themselves is of high importance in defensive transitioning, since it puts a stop to a number of attacks. Only rarely a physical collision will be interpreted as a foul by the aggressor when defending counter-attacks, as long as there is only minimal contact between the legs.

- Passiveness is a curse for Leipzig just as much as a match in which they are too dominant. At times, the team will give up a bit on their strong positional play when they are in the lead, while also becoming less precise in the transition into the final third of the pitch. This lack of precision results in a loss of dominance and a less strong Gegenpressing because of the weaker staggering in the initial phase.

How can Leipzig be beaten?

- Building up with a back-three, in connection with secure ball-circulation and constant advancing of the wing-players without the general aspiration to actually include them immediately into the passing, can force Leipzig into the role of a passive defender.

- Once dominance is achieved, the challenge is that the attacking players have to be in constant movement to be available as receiving options and to create opportunities for layoffs and subsequent through-balls.

- To defend against Leipzig's build-up, it has to be attacked at its weakest point. The weakest point is the well-used pass from the full-back to the winger that has moved inside. Here, an opponent has to give the winger a little space at first to provoke the pass, but then force the immediate attack to either intercept the pass or create a loss of possession through a duel.

- Corners offer a number of options with short-flight balls and flick-ons toward the far post.

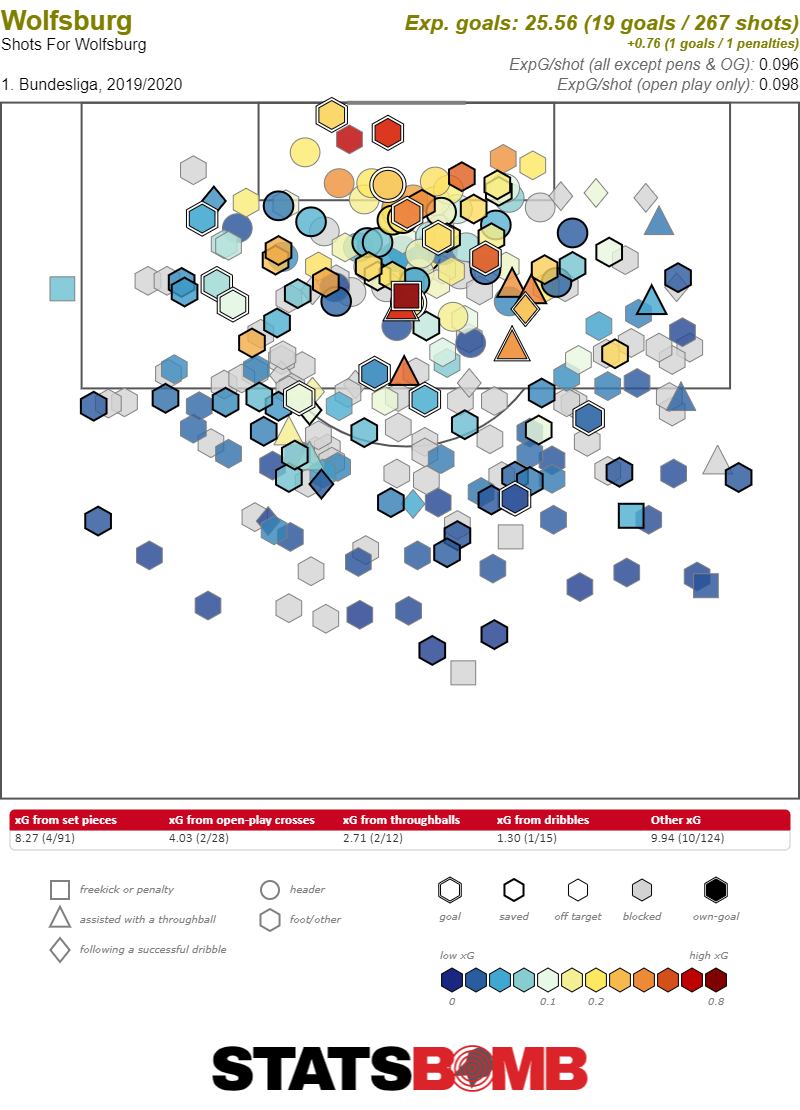

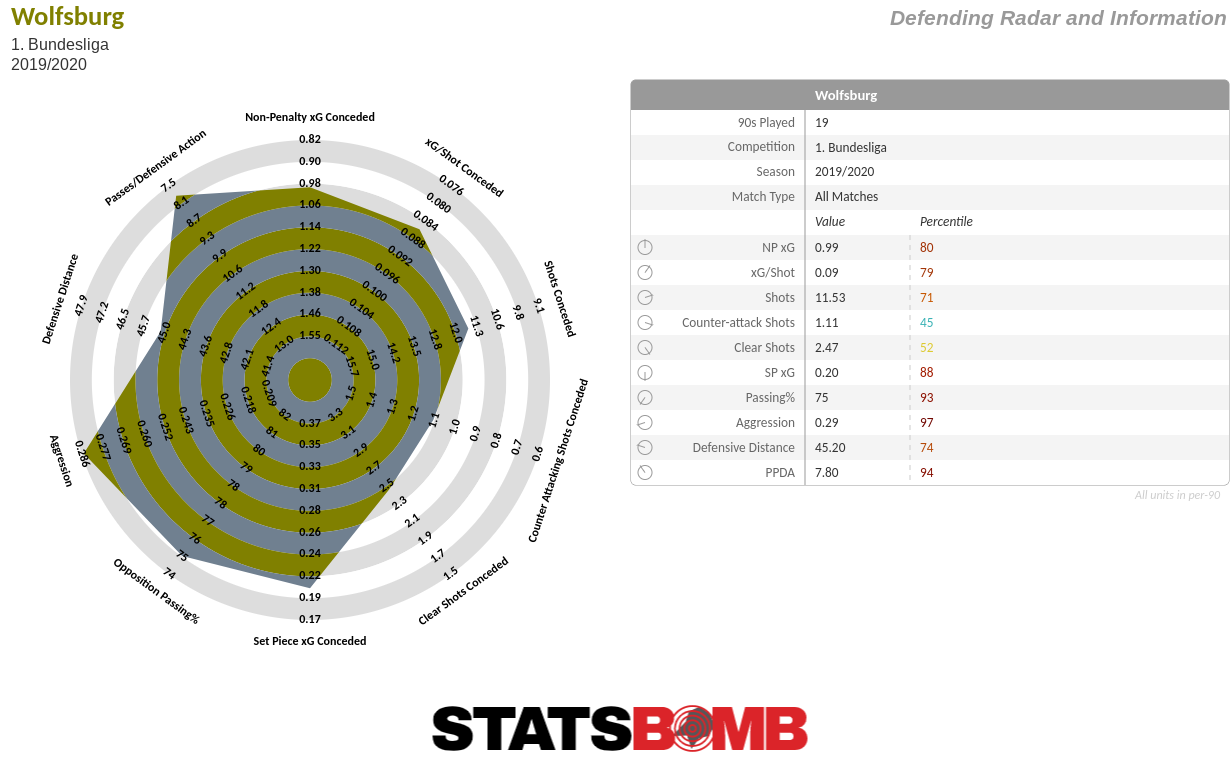

Since former LASK Linz manager Oliver Glasner took over this summer, Die Wölfe boast one of the league’s best defences.

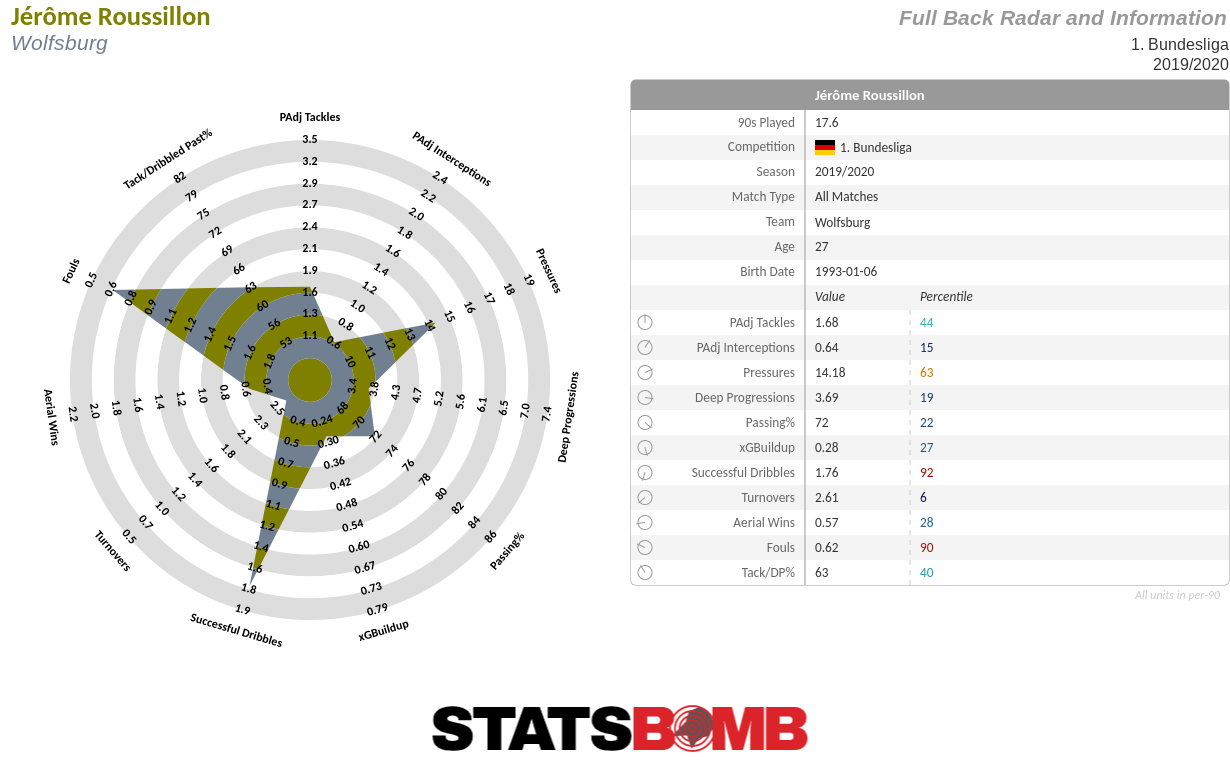

Since former LASK Linz manager Oliver Glasner took over this summer, Die Wölfe boast one of the league’s best defences.  Glasner built a sturdy defensive side by implementing a rigid but beautiful pressing style, the same style that allowed his lowly LASK side to put up really impressive performances in the Austrian Bundesliga in recent seasons. But Glasner’s squad also has the personnel to drop back deeper at times, with physically strong, tall players like John-Anthony Brooks (6'4"), Josuha Guillavogui (6'3") and Marcel Tisserand (6'3") playing in the axis. Glasner has three decent wing-backs at his disposal on the flanks: summer-signee Kevin Mbabu, anonymous-but-good Brazilian William and, most importantly, French leftie Jérôme Roussilon, who, given his extremely specific dribbling skillset. seems set for a big club move next summer.

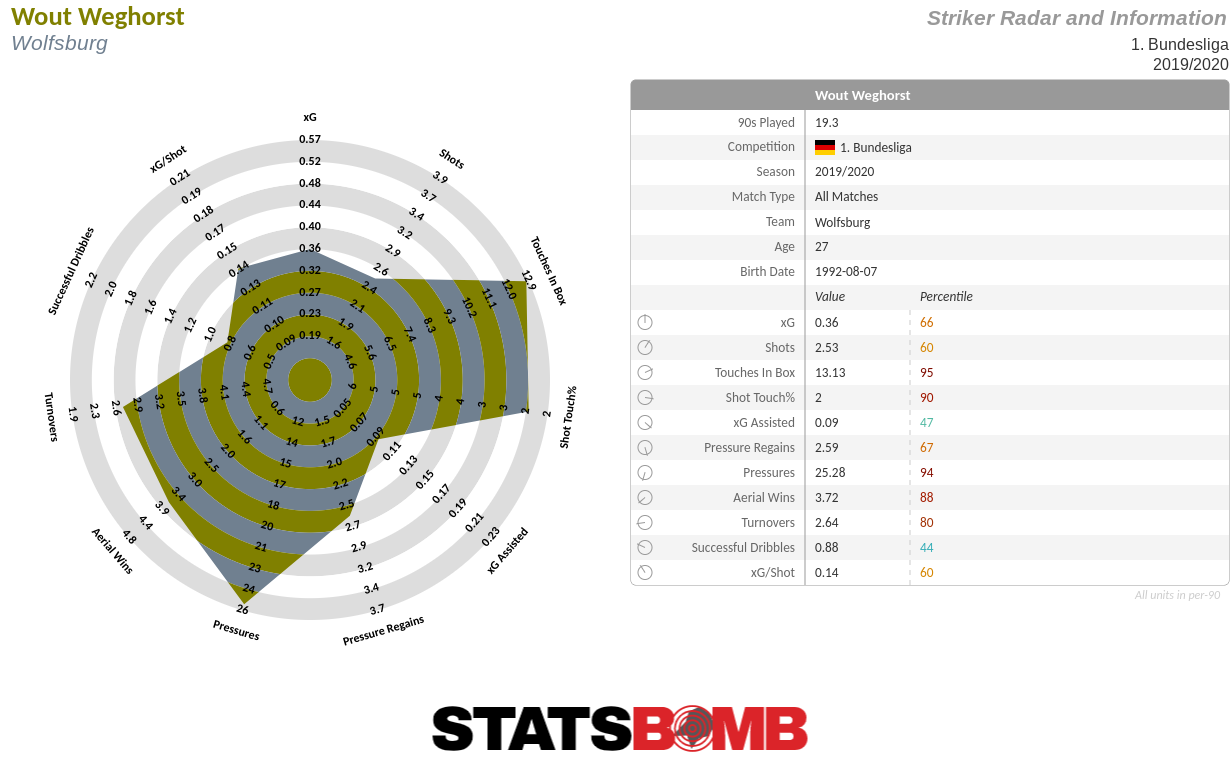

Glasner built a sturdy defensive side by implementing a rigid but beautiful pressing style, the same style that allowed his lowly LASK side to put up really impressive performances in the Austrian Bundesliga in recent seasons. But Glasner’s squad also has the personnel to drop back deeper at times, with physically strong, tall players like John-Anthony Brooks (6'4"), Josuha Guillavogui (6'3") and Marcel Tisserand (6'3") playing in the axis. Glasner has three decent wing-backs at his disposal on the flanks: summer-signee Kevin Mbabu, anonymous-but-good Brazilian William and, most importantly, French leftie Jérôme Roussilon, who, given his extremely specific dribbling skillset. seems set for a big club move next summer.  Judging by their January transfers — they replaced a mediocre centre back (Jeffrey Bruma, loaned to Mainz) with a much more promising one (Salzburg’s Marin Pongracic) — Wolfsburg won’t crash on defensively in the second half of the season. The question is whether their attacking numbers will turn around. Certain offensive woes are down to squad management, but Wout Weghorst is a truly excellent target man, whose intense running suits Glasner’s pressing style perfectly.

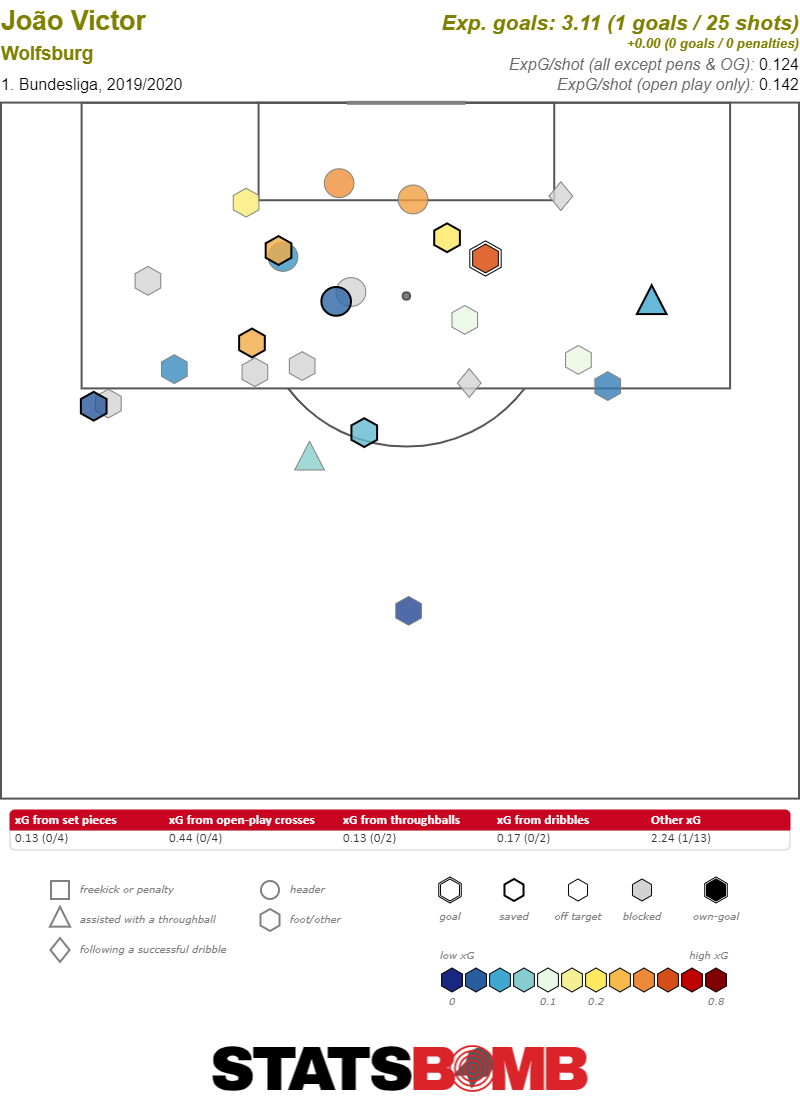

Judging by their January transfers — they replaced a mediocre centre back (Jeffrey Bruma, loaned to Mainz) with a much more promising one (Salzburg’s Marin Pongracic) — Wolfsburg won’t crash on defensively in the second half of the season. The question is whether their attacking numbers will turn around. Certain offensive woes are down to squad management, but Wout Weghorst is a truly excellent target man, whose intense running suits Glasner’s pressing style perfectly.  But Wolfsburg has had real trouble providing Weghorst with much-needed creative talent. Glasner rotates five players through the two positions supporting the Dutch forward: João Victor (ex-LASK), the talented but inconsistent Josip Brekalo, Swiss players Admir Mehmedi and Renato Steffen, and utility man Felix Klaus, This fivesome currently boast a disappointing cumulative goal total of six strikes in nineteen Bundesliga matches played. Not good. Finding non-Weghorst goals will be key for a successful second half of the season for Wolfsburg. Hopefully Victor in particular, who is playing well behind his xG numbers, can come good

But Wolfsburg has had real trouble providing Weghorst with much-needed creative talent. Glasner rotates five players through the two positions supporting the Dutch forward: João Victor (ex-LASK), the talented but inconsistent Josip Brekalo, Swiss players Admir Mehmedi and Renato Steffen, and utility man Felix Klaus, This fivesome currently boast a disappointing cumulative goal total of six strikes in nineteen Bundesliga matches played. Not good. Finding non-Weghorst goals will be key for a successful second half of the season for Wolfsburg. Hopefully Victor in particular, who is playing well behind his xG numbers, can come good

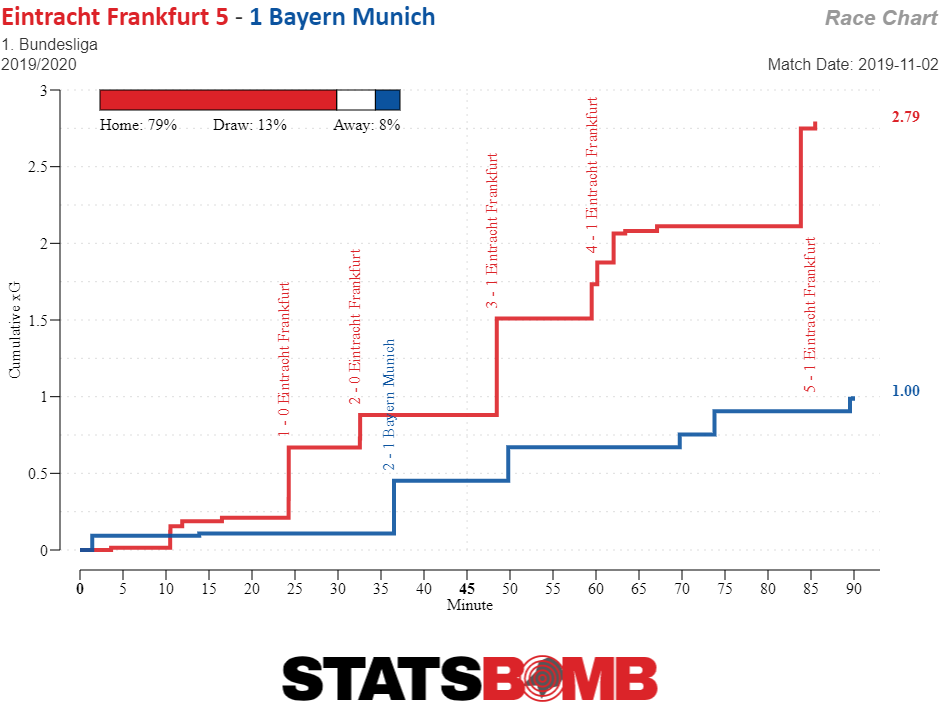

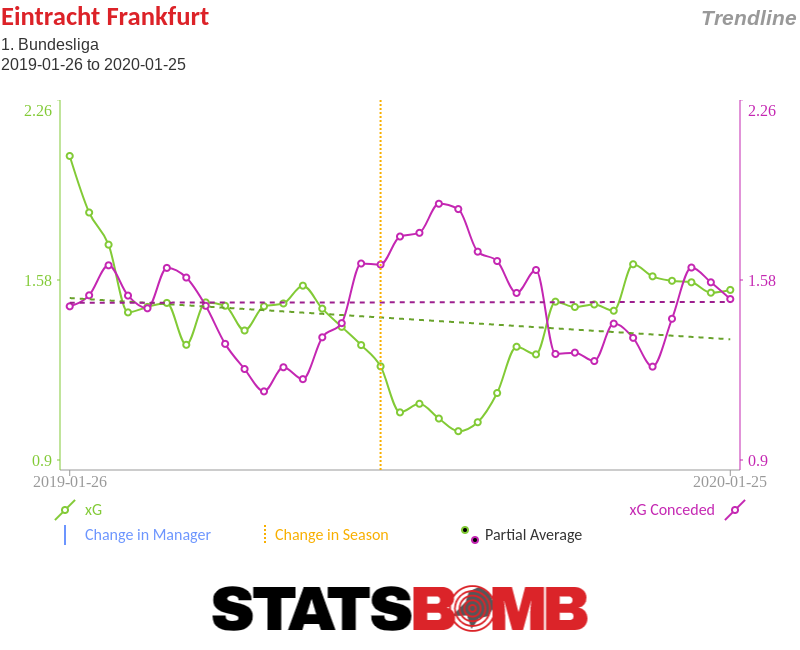

Frankfurt grabbed only one point in the remaining seven league games of 2019. The side's only hope during this horrid run of games was that their level of play — although not good, of course — never dropped to super worrisome depths.

Frankfurt grabbed only one point in the remaining seven league games of 2019. The side's only hope during this horrid run of games was that their level of play — although not good, of course — never dropped to super worrisome depths.  And lo and behold! Frankfurt have stormed out of the gate in 2020. They re-opened their league campaign by beating Hoffenheim 2–1 on their turf, and followed that up with a 2–0 victory against league leaders RB Leipzig. On paper, Eintracht manager Adi Hütter has opted for a much more defensive style than the one at which his team excelled last season. Since the winter break, Hütter has traded in the 3-4-1-2 system for a 4-4-1-1 setup, with Timothy Chandler and Filip Kostić — both wing-backs in the old system — as wingers, and the intense running of Mijat Gaćinović as the only support of central striker Bas Dost.

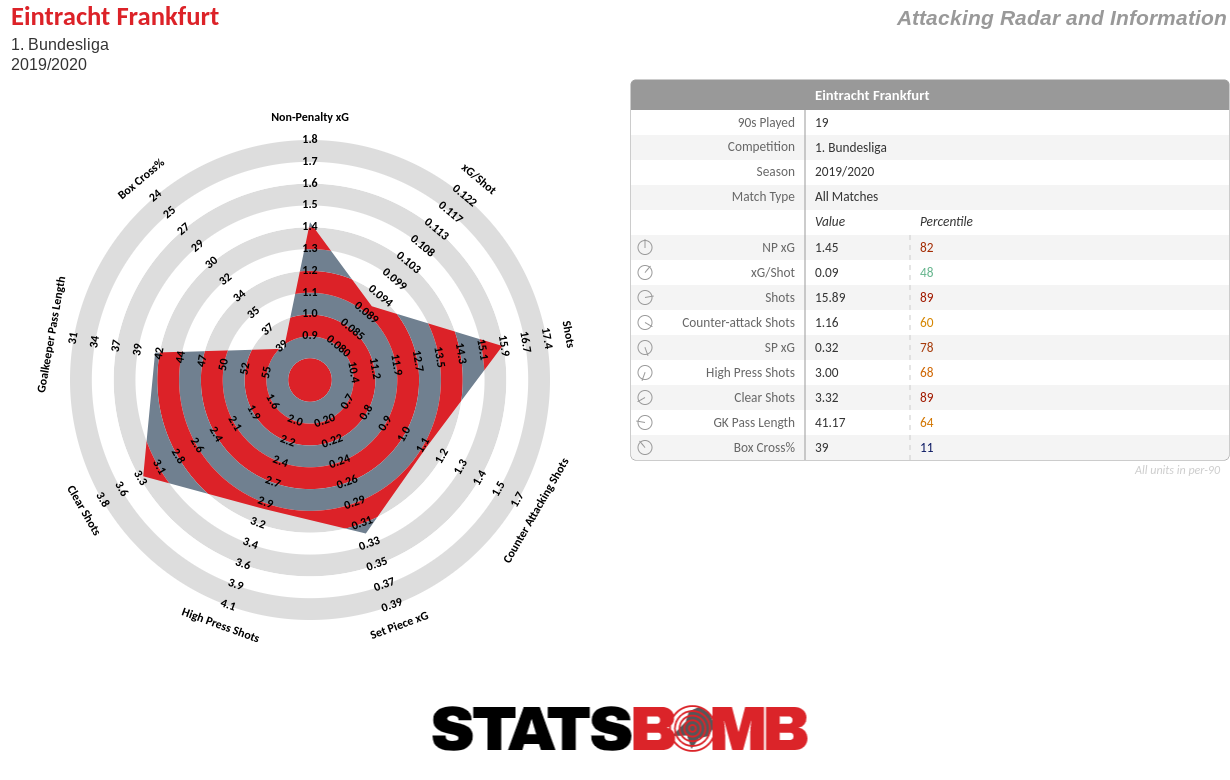

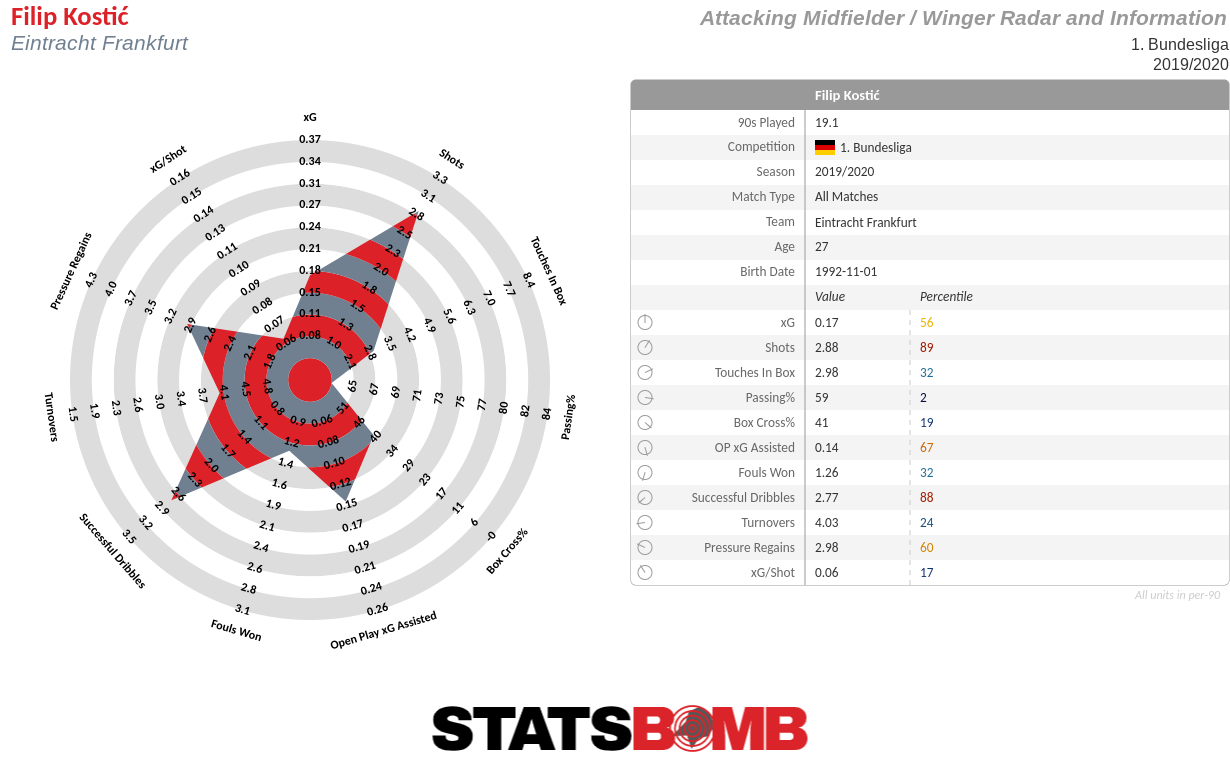

And lo and behold! Frankfurt have stormed out of the gate in 2020. They re-opened their league campaign by beating Hoffenheim 2–1 on their turf, and followed that up with a 2–0 victory against league leaders RB Leipzig. On paper, Eintracht manager Adi Hütter has opted for a much more defensive style than the one at which his team excelled last season. Since the winter break, Hütter has traded in the 3-4-1-2 system for a 4-4-1-1 setup, with Timothy Chandler and Filip Kostić — both wing-backs in the old system — as wingers, and the intense running of Mijat Gaćinović as the only support of central striker Bas Dost.  As is often the case, a team’s reality can differ wildly than what's on paper. Powerhouses Bayern and Leipzig, alongside fifth-placed Leverkusen, are the only teams to put up more shots on a per-game basis than Hütter’s heavy-pressing squad (a solid 15.89 per game average). Super impressive, if you take into account that Frankfurt sold their shiniest players — Sébastien Haller (West Ham), Luka Jović (Real Madrid) and Ante Rebić (AC Milan) — this summer, a three-headed offensive monster who accounted for a whopping 41 league goals in 2018–19. The only star player on offense who stayed with Die Adler last summer, Serbian winger Kostić, has been sensational this season. After 19 match weeks, Frankfurt’s leftie is second in the league in key passes (46) and in successful dribbles (53), whilst only Robert Lewandowski and Timo Werner have put up more shots than Kostić (55) so far.

As is often the case, a team’s reality can differ wildly than what's on paper. Powerhouses Bayern and Leipzig, alongside fifth-placed Leverkusen, are the only teams to put up more shots on a per-game basis than Hütter’s heavy-pressing squad (a solid 15.89 per game average). Super impressive, if you take into account that Frankfurt sold their shiniest players — Sébastien Haller (West Ham), Luka Jović (Real Madrid) and Ante Rebić (AC Milan) — this summer, a three-headed offensive monster who accounted for a whopping 41 league goals in 2018–19. The only star player on offense who stayed with Die Adler last summer, Serbian winger Kostić, has been sensational this season. After 19 match weeks, Frankfurt’s leftie is second in the league in key passes (46) and in successful dribbles (53), whilst only Robert Lewandowski and Timo Werner have put up more shots than Kostić (55) so far.  With Hütter seemingly settled on his favourite starting eleven for the coming months, Eintracht’s main concern is improving their set-piece defence. Before the winter break, only Mainz conceded more goals than Frankfurt from corners and free-kicks (8 in 17 games). With Frankfurt playing a free-roving style in open play, a somewhat acceptable goal balance from dead-ball moments is pretty crucial to avoid arcade-like scoring lines. However, much more quietly than last season, Hütter has done well with Frankfurt this year, and their nine-point gap behind sixth-placed Schalke does not seem impossible to close in the remaining fifteen weeks.

With Hütter seemingly settled on his favourite starting eleven for the coming months, Eintracht’s main concern is improving their set-piece defence. Before the winter break, only Mainz conceded more goals than Frankfurt from corners and free-kicks (8 in 17 games). With Frankfurt playing a free-roving style in open play, a somewhat acceptable goal balance from dead-ball moments is pretty crucial to avoid arcade-like scoring lines. However, much more quietly than last season, Hütter has done well with Frankfurt this year, and their nine-point gap behind sixth-placed Schalke does not seem impossible to close in the remaining fifteen weeks.

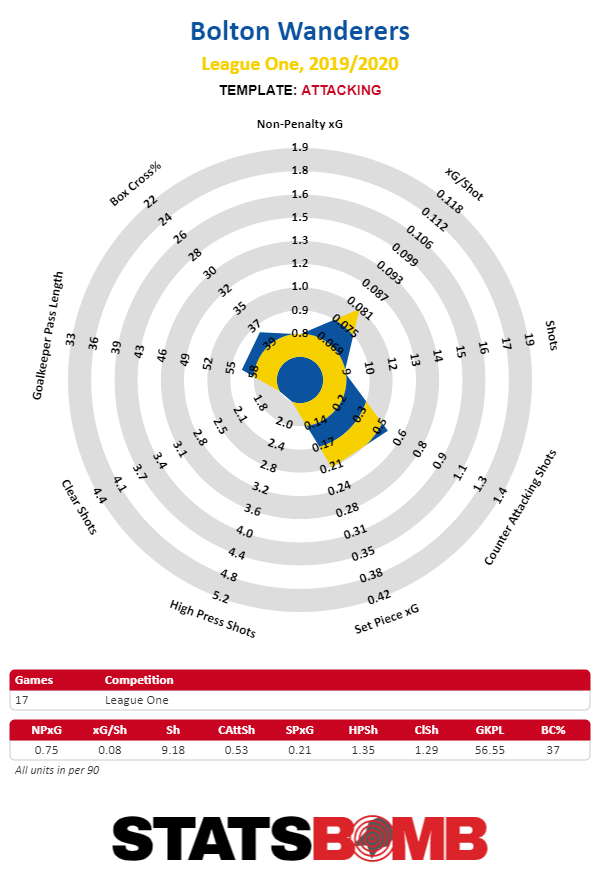

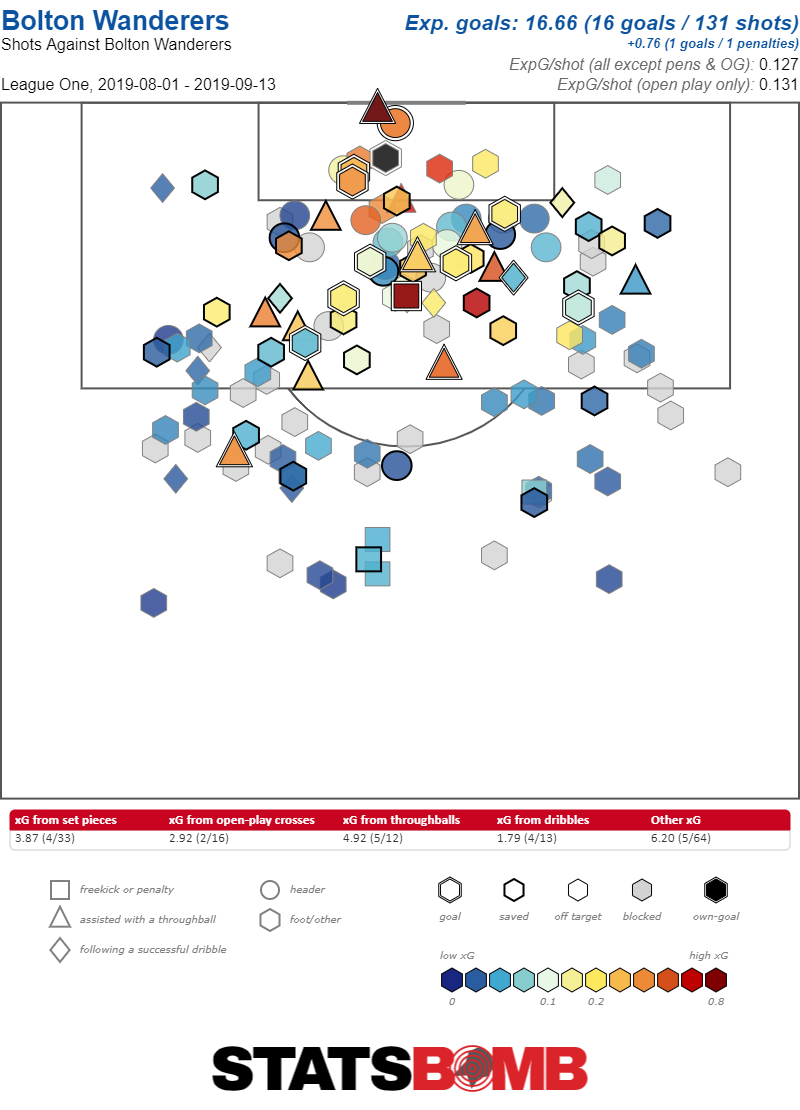

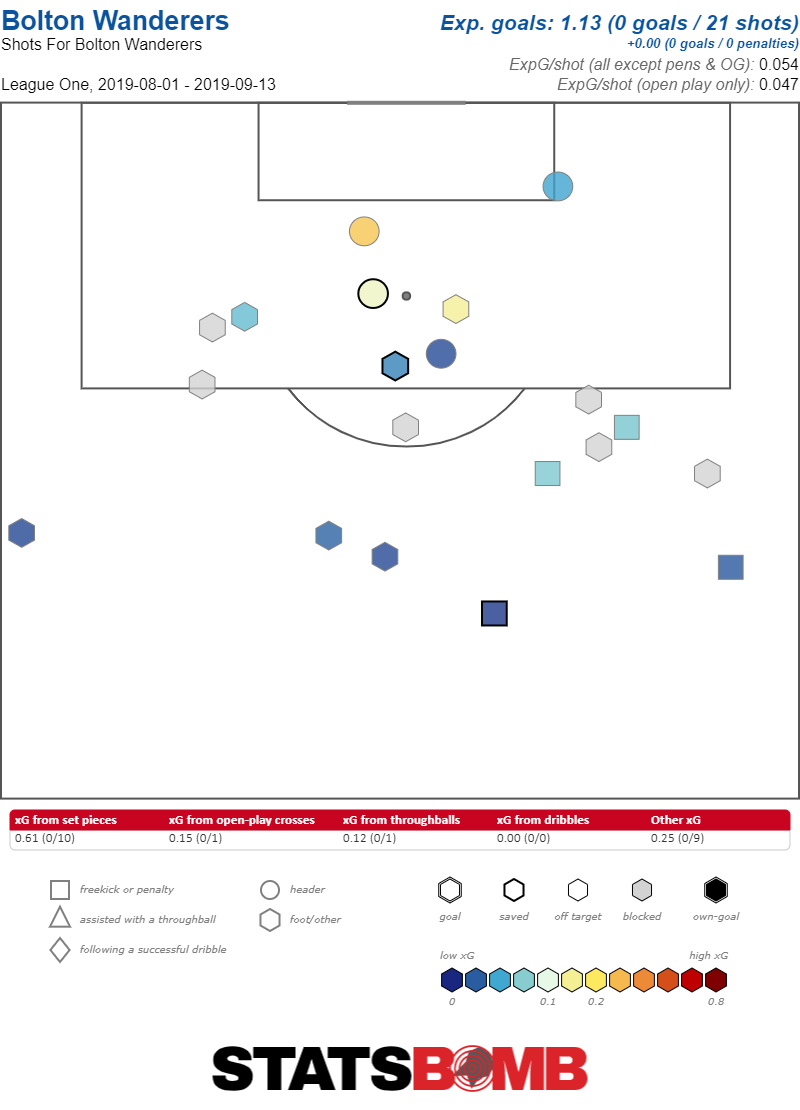

All this and . . . Bolton started the season with a 12-point deduction for going into administration whilst the takeover was in process. That unexpected draw with Coventry took them to -11 points, and begun the long road toward a positive tally. It helped that on August 28th the takeover finally went through and they could sign a few senior professionals for the season. Five games in, but better late than never. Meanwhile, manager Phil Parkinson resigned, understandably exhausted by months of constant pressure and uncertainty around the club's future, whist seldom receiving his salary on time (if at all) for his troubles.

All this and . . . Bolton started the season with a 12-point deduction for going into administration whilst the takeover was in process. That unexpected draw with Coventry took them to -11 points, and begun the long road toward a positive tally. It helped that on August 28th the takeover finally went through and they could sign a few senior professionals for the season. Five games in, but better late than never. Meanwhile, manager Phil Parkinson resigned, understandably exhausted by months of constant pressure and uncertainty around the club's future, whist seldom receiving his salary on time (if at all) for his troubles.  A bit of a downpour on the parade, but

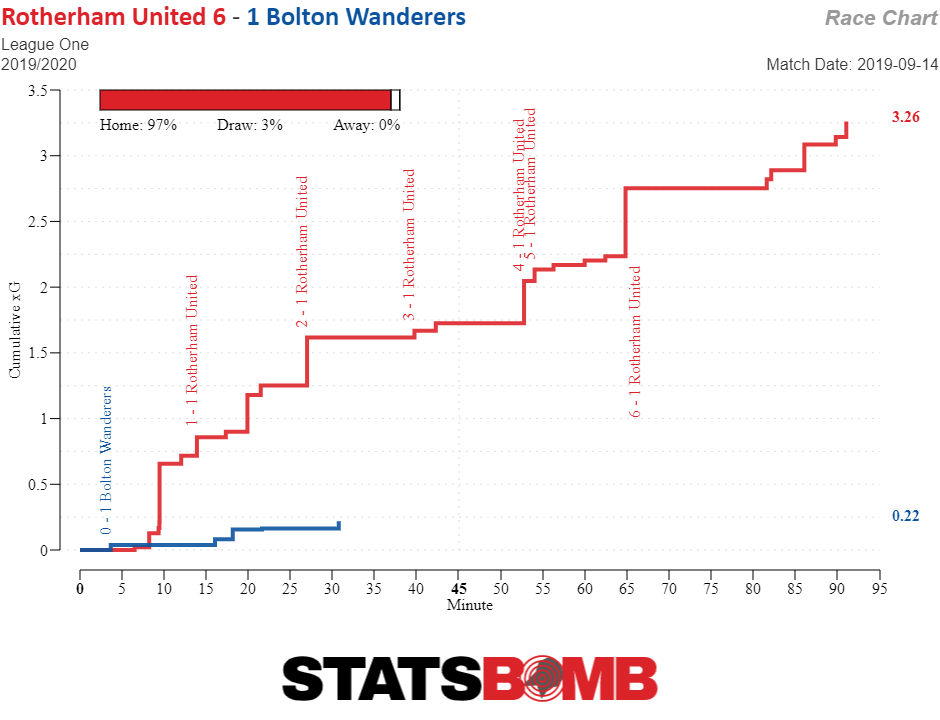

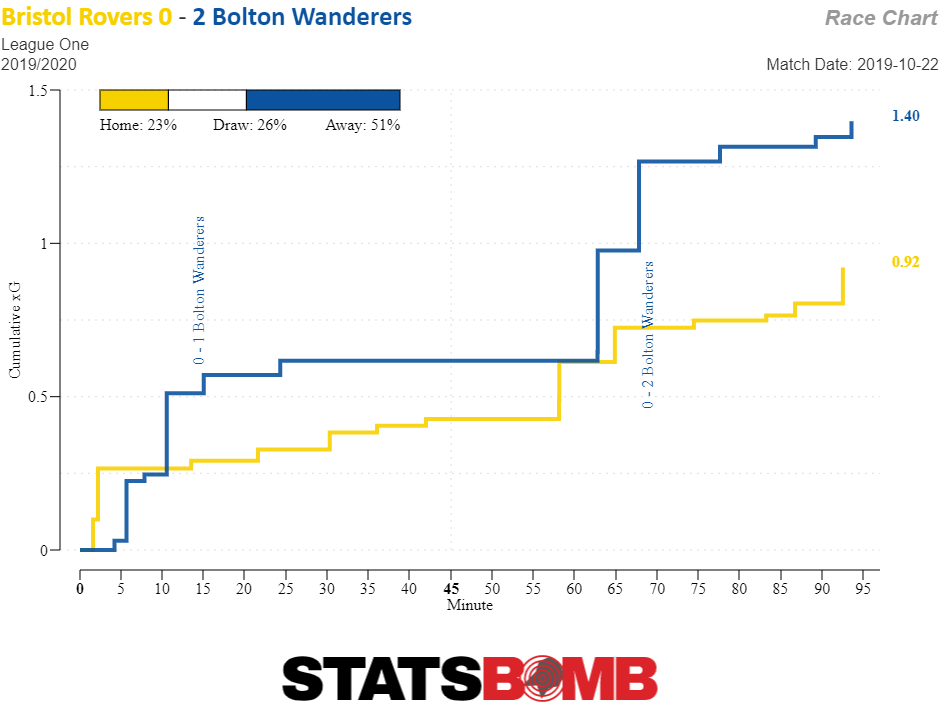

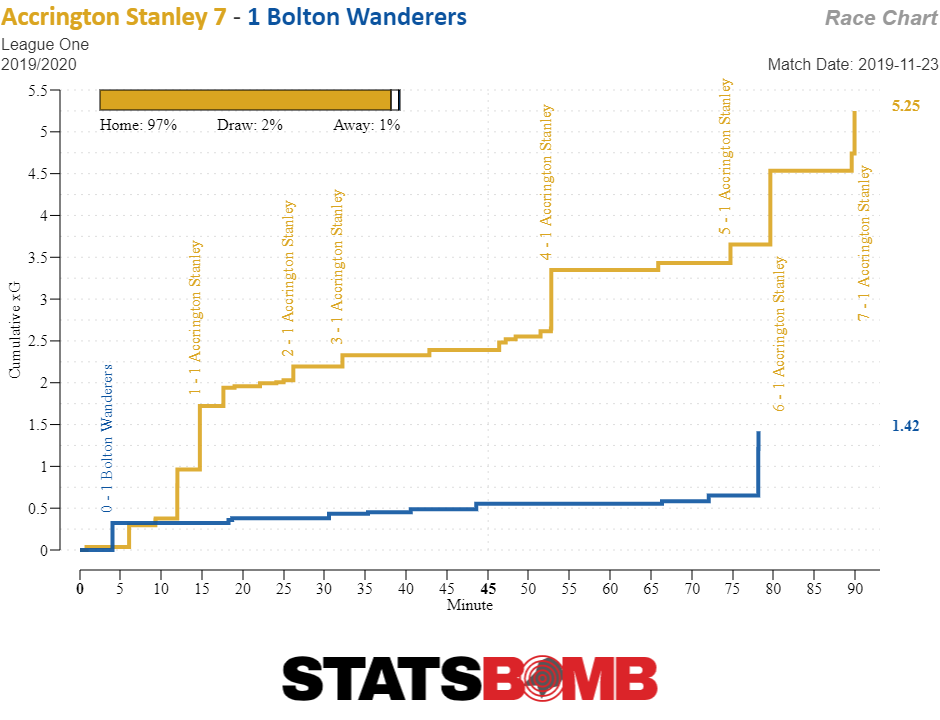

A bit of a downpour on the parade, but  That first win lit the touch paper. The remaining deficit was wiped out within the next two matches as victories over Fleetwood and Milton Keynes saw them hit the milestone that had been objective number one since Hill had taken charge. Clearly the footballing gods decided this was all becoming a bit too much of a fairytale. We all know and love (what do you mean you don’t?) the sacred cliché, 'goals change games'. We all know that red cards change games too. As Bolton went 1–0 up away at Accrington on the back of their three-game winning streak, the omnipotent soccer powers above us decided that a penalty to Accrington and a red card to defender Josh Earl for the offending incident were just recourse to keep fans' feet planted firmly on the ground. They might’ve gone a bit far with the resultant 7–1 hammering, mind.

That first win lit the touch paper. The remaining deficit was wiped out within the next two matches as victories over Fleetwood and Milton Keynes saw them hit the milestone that had been objective number one since Hill had taken charge. Clearly the footballing gods decided this was all becoming a bit too much of a fairytale. We all know and love (what do you mean you don’t?) the sacred cliché, 'goals change games'. We all know that red cards change games too. As Bolton went 1–0 up away at Accrington on the back of their three-game winning streak, the omnipotent soccer powers above us decided that a penalty to Accrington and a red card to defender Josh Earl for the offending incident were just recourse to keep fans' feet planted firmly on the ground. They might’ve gone a bit far with the resultant 7–1 hammering, mind.  The 95th-minute equaliser at home to AFC Wimbledon restored spirit and belief to keep Bolton’s unlikely mission on track before they became the latest victim to succumb to Peterborough and Ivan Toney last weekend.

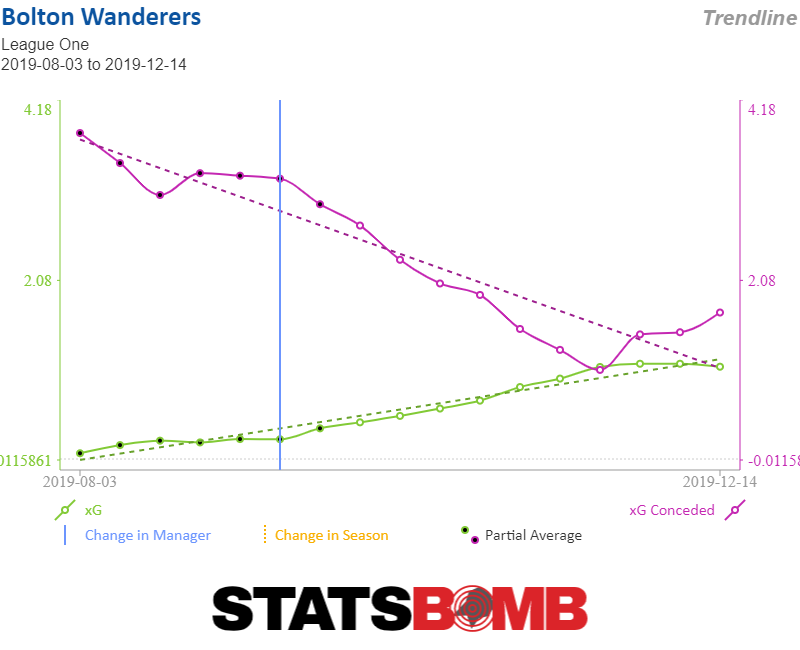

The 95th-minute equaliser at home to AFC Wimbledon restored spirit and belief to keep Bolton’s unlikely mission on track before they became the latest victim to succumb to Peterborough and Ivan Toney last weekend.  The blue marker shows both when Keith Hill was appointed and when Bolton started fielding senior players. Their league record since that moment is W3 D4 L5 from 12 games, a rate of 1.08 points per game. There are always caveats, but a simplistic projection of that rate over the remainder of the season would leave Bolton on 31 points, well short of the required total to survive. Now to colour it with the necessary context. Bolton have essentially and necessarily been running a pre-season regime during this period, playing against opposition with the privilege of correctly implemented strength and conditioning programmes, able to not only fully recover game-to-game but also play at the peak of their powers. There’s scope to suggest that Bolton should get better as the season wears on and their fitness levels match those of their opponents. It's likely there'll be another minor reshuffling of the pack and the arrival of new faces in January to further mould the side in Hill’s image. This should leave Bolton more competitive and able to pick up points at a higher rate. The major issue remains the mountain that they have to scale. For all the good work that’s been done to get them to a competitive level, that height might be too much. Essentially starting the season from scratch with just two points, they have to pick up more points in a half-season than their relegation rivals will in the full season. The clever clogs at the spread firms suggest the points total needed to survive could end up being as high as 50. That leaves Bolton needing to pick up points at the rate of a play-off standard team for the remainder of the season, which would require yet another large leap forward in their levels of performance. To put it one way, Bolton could win their next eight matches on the spin and would still need to pick up points from then onwards at around the same 1.08ppg rate they’ve managed so far under Hill. To focus in too closely on that would be to lose sight of the bigger picture. No matter what division the club competes in next season, the slate will be wiped clean, the team will start the season with a neutral points tally, hell, they’ll even get a proper pre-season under their belts. There’ll be no fretting over whether or not the season tickets fans purchased will actually manifest into a team to watch on the pitch. This season should’ve been a complete write-off, yet while Bolton’s great escape still isn’t probable, it’s certainly not impossible. And that's an unlikely victory on its own.

The blue marker shows both when Keith Hill was appointed and when Bolton started fielding senior players. Their league record since that moment is W3 D4 L5 from 12 games, a rate of 1.08 points per game. There are always caveats, but a simplistic projection of that rate over the remainder of the season would leave Bolton on 31 points, well short of the required total to survive. Now to colour it with the necessary context. Bolton have essentially and necessarily been running a pre-season regime during this period, playing against opposition with the privilege of correctly implemented strength and conditioning programmes, able to not only fully recover game-to-game but also play at the peak of their powers. There’s scope to suggest that Bolton should get better as the season wears on and their fitness levels match those of their opponents. It's likely there'll be another minor reshuffling of the pack and the arrival of new faces in January to further mould the side in Hill’s image. This should leave Bolton more competitive and able to pick up points at a higher rate. The major issue remains the mountain that they have to scale. For all the good work that’s been done to get them to a competitive level, that height might be too much. Essentially starting the season from scratch with just two points, they have to pick up more points in a half-season than their relegation rivals will in the full season. The clever clogs at the spread firms suggest the points total needed to survive could end up being as high as 50. That leaves Bolton needing to pick up points at the rate of a play-off standard team for the remainder of the season, which would require yet another large leap forward in their levels of performance. To put it one way, Bolton could win their next eight matches on the spin and would still need to pick up points from then onwards at around the same 1.08ppg rate they’ve managed so far under Hill. To focus in too closely on that would be to lose sight of the bigger picture. No matter what division the club competes in next season, the slate will be wiped clean, the team will start the season with a neutral points tally, hell, they’ll even get a proper pre-season under their belts. There’ll be no fretting over whether or not the season tickets fans purchased will actually manifest into a team to watch on the pitch. This season should’ve been a complete write-off, yet while Bolton’s great escape still isn’t probable, it’s certainly not impossible. And that's an unlikely victory on its own.

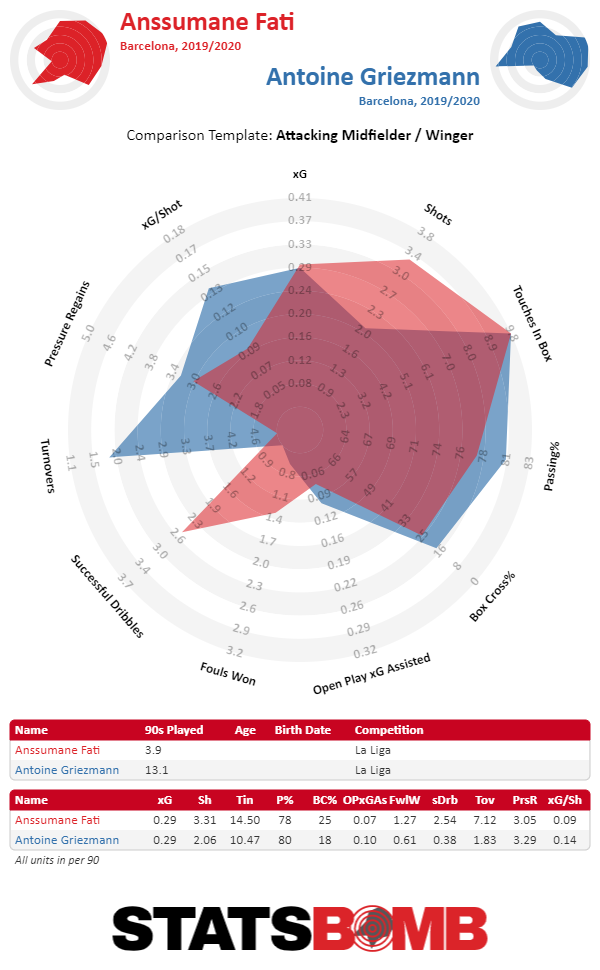

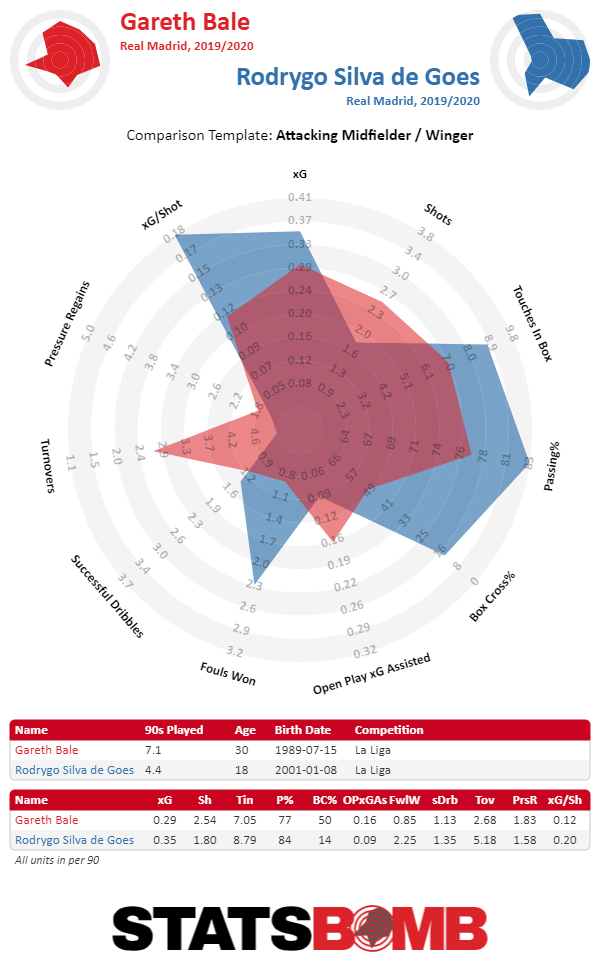

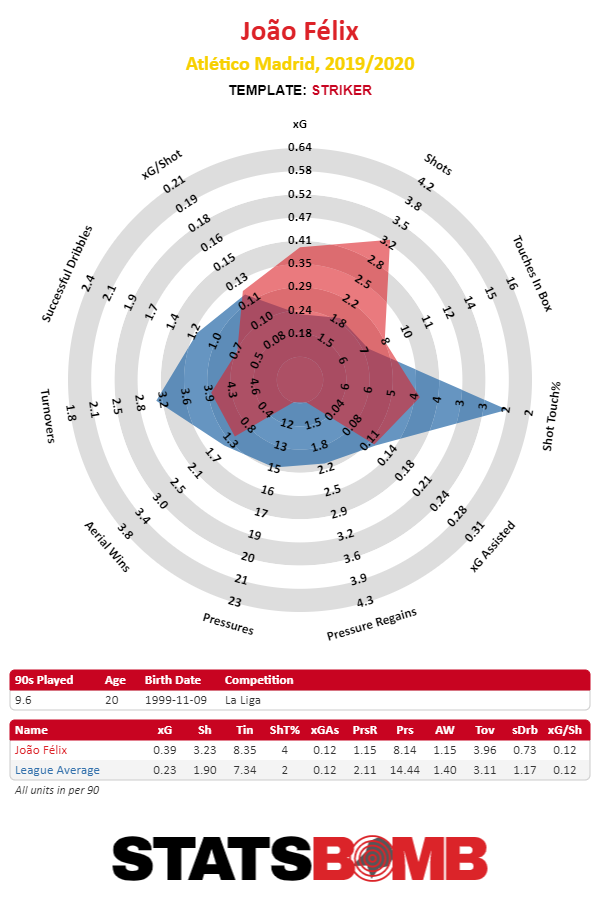

On the right wing, Rodrygo is competing against Bale for the starting role in the lineup. He’s not an elite dribbler like Vinícius, but he tries to compensate by being more cerebral and precise. Rodrygo does not shoot often but is more careful about his shot locations, averaging the highest xG per shot this season among Real Madrid forwards. While Bale seems increasingly comfortable staying on the wing and whipping a cross into the box, Rodrygo seems more willing to attack the box, which is ultimately reflected in his higher rate of touches in the box and xG.

On the right wing, Rodrygo is competing against Bale for the starting role in the lineup. He’s not an elite dribbler like Vinícius, but he tries to compensate by being more cerebral and precise. Rodrygo does not shoot often but is more careful about his shot locations, averaging the highest xG per shot this season among Real Madrid forwards. While Bale seems increasingly comfortable staying on the wing and whipping a cross into the box, Rodrygo seems more willing to attack the box, which is ultimately reflected in his higher rate of touches in the box and xG.

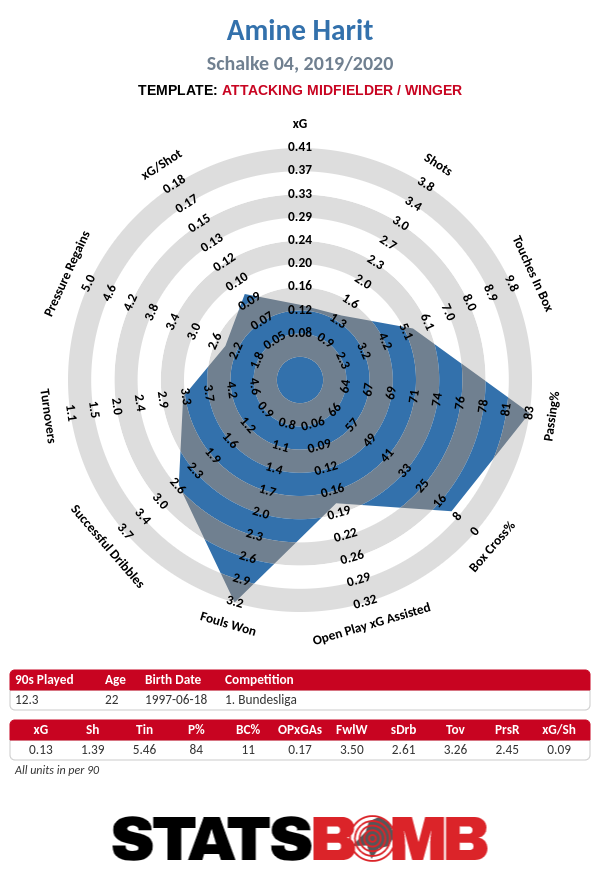

Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.

Harit really is doing a lot of things well with the ball at his feet; however, he is neither shooting a lot (1.39 shots per 90), nor taking high-value shots (0.09 xG per shot). If the goals are going to keep coming, at least one of those two things will have to change.