As you may know, I have had some time on my hands recently. In addition to taking a bit of a holiday, during my free time I have also been writing a book explaining the various competitive edges I have uncovered in the last couple of years researching football.

Now the majority of this book may never see print, but that's not really the point - the point of this is to explain to stats laypeople how their football teams can improve. A lot of the material inside it isn't completely unique, but it adheres to some extremely important requests decision makers inside of various sports have with regard to analysis.

It's practical.

It's hopefully easy to understand.

It focuses on what is important: winning.

In the past, there has always been a fear among analyst types that by writing about edges and explaining too much of their research, they would be giving away hugely valuable information for free.

What if that's the only edge I ever uncover? Do I diminish my own chances of success by making everyone else smarter?

For a while, I also held this fear until I realized something I explained in a mailbag a couple of weeks ago - the well on improvement goes incredibly deep. I could cut this or any number of other chapters out and still end up with a book chock full of innovation and improvement.

At the end of the day, it seemed a lot better choice not to live in fear and just work hard at being awesome.

Amusingly, even if a team knew all of this information and kept it to themselves, they would not be guaranteed success. As I have been explaining publicly for the last two months, simply possessing great information isn't enough - it's how you use it that truly matters.

Unnamed Book Title Chapter X - Shot Locations

We’ll start here because I think this is one of the easiest concepts to grasp from an analytical perspective and one of the hardest to teach to football people. It flows from four basic principles

- The closer a shot is to goal, the more likely it is to be converted.

- Central locations are better than wide. (This mostly has to do with angles of the goal covered by the goalkeeper from wide shots.)

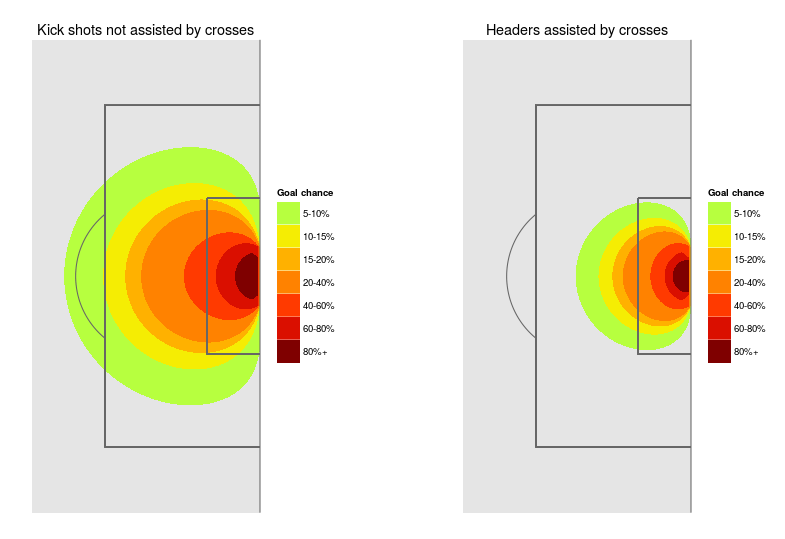

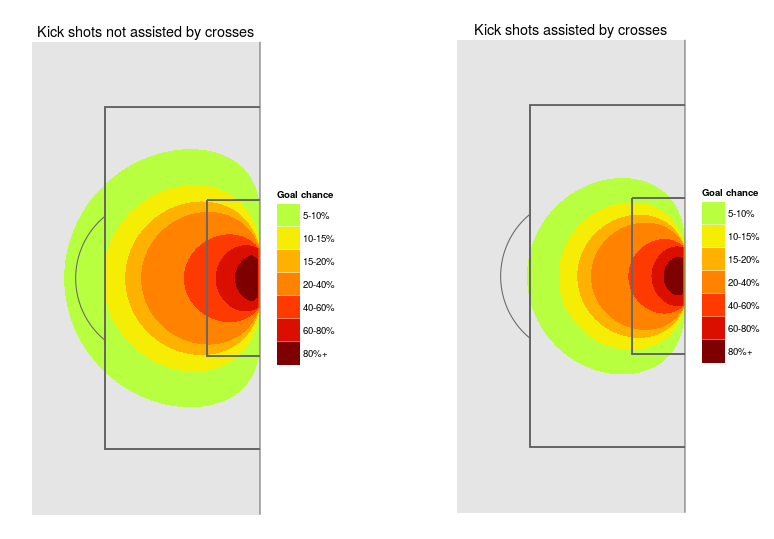

- At the same distance, shots with feet are far more likely to become goals than shots with the head.

- Crosses are hard.

If you want to visualize these principles, they look like this:

Principle 1 is very easy to explain and understand. Principle 2 is also quite straightforward, with or without the trigonometry involved to prove the concept. 3 and 4 might seem open to argument, but are conclusively proven by data analysis.

From these principles flows one core concept: We want to push players to take the highest quality shots possible. And related to that, at a team level we need to find ways of attacking that create high quality shots.

I’m not suggesting these are ground shaking ideas – far from it. These are basic truths about the game of football. Why then are they hard to teach?

Consider the following common football cliches:

You can’t score if you don’t shoot.

Go ahead son, have a pop.

We want our players to have the freedom to try things on the pitch – we don’t want to limit their creativity.

He unleashed a thunderbastard from distance!

Players are often taught to “try their luck from range,” and to “test the keeper.” In my experience, they are rarely taught where good shooting locations are and not to shoot unless they are inside them. This creates a problem because the whole concept of shot locations competes directly with a far more powerful force: habit.

We try to automate as much behavior as possible on the pitch so that players can use their active brains to concentrate on reading the game. When it comes to shots, you are dealing with hundreds of thousands of past attempts at every level of football played, where that player has taken a shot. If they have never been taught where to take them, a player then needs to think before every time they might shoot whether that shot is good or not, and then choose whether to take it.

The combination of fan culture where long-range goals are the ones that make the highlight shows and get the plaudits from the pundits and the sheer weight of habit make this a hard concept to convey, especially to mature professional footballers. This is even more true if no one has bothered to explain the concept of good and bad shots to players previously.

At some point not limiting creativity of your players begins to directly butt heads with the probability of winning games.

Okay, whatever - it seems hard for some players to learn this… Why bother?

Because taking higher value shots makes your attack and scoring output more consistent. As a result, it should make you more likely to win.

These are two huge edges to grind over the course of a season.

It helps to add some very basic math into this to fully illustrate the scale of what I’m talking about.

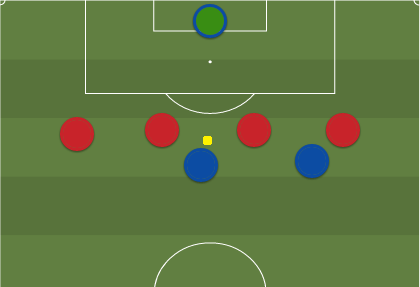

Take the picture below.

A shot from this location would have about a 3% chance of being a goal (.03 expected goals or xG). If a player is completely by himself with no teammates around, it might make sense to take the shot, but on average you will get 1 goal for every 33 shots from this location. For most teams that is about one goal for every two to three games worth of shots. Not great, Bob!

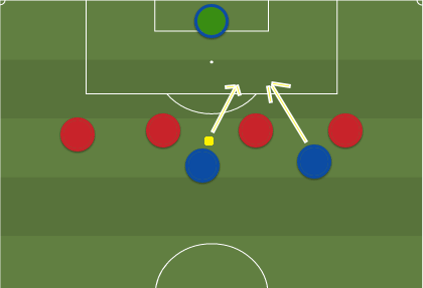

Now add an additional player to the mix that is making a vertical run toward the goal.

A completed pass here creates a likely 1v1 with the goalkeeper from fairly close range. The resulting shot is approximately a minimum of .40 xG, so it would be converted into a goal at least 40% of the time.

How often does that pass need to be successful for passing to be a better option than shooting?

The mathematic answer is easy, but I can tell you from experience that most players gut instinct gives them an answer far higher than the actual probability.

If we do the math(s), we find the shot in example 2 (after the pass) is 13.3 times more likely to become a goal than the shot from distance (.40/.03). Even if your players could only pull off this successful pass one in every ten times, it still adds positive expectation to the result at the end of the game.

However, it doesn't mean that making this pass every time is the correct way to go about it. In every strategy game in the world, you need to vary your strategies to have the highest chance at success. Football is no different.

There’s another factor here that gets far more math-y, but it involves variance. The ride on the variance train is a bumpy one, and we would far prefer to minimize variance whenever possible in an effort to create more certainty in the outcome.

Consistently creating fewer, higher quality chances lowers the variance in scoring output. The example used in a great piece of writing by Danny Page is Team Coin vs Team Die. Team Coin takes 4 shots a game, making their expected goal return 2. Team Die takes 12 shots a game, which on a six-sided die would also make their expected goal return 2. Simples. However, this is where variance comes into play.

If we simulate these two teams playing each other 10000 times, what we find is that Team Coin wins an average of 40% of the time, Team Die 36% of the time, and a draw occurs 24% of the time. The point return over the course of the season would be 1.42 for Team Coin and 1.36 for Team Die.

.06 points per game difference seems microscopic, right? Take that across a whole season, however, and you end up with 2-3 points more for the team with lower variance in their chances. 2-3 points is often the difference between relegation and survival, and it can also be the difference between Champions/Champions League spots or automatic promotion vs the playoffs.

This is counterintuitive across the entire sport, so let me state it again:

All things being equal, you would rather have fewer chances with a very high quality than many small quality chances.

Creating the big chances is hard, but it’s also damned important in giving your team the best chance of ending the season at the top of the table.

The variance train also makes a huge difference in player value when it comes to scoring goals.

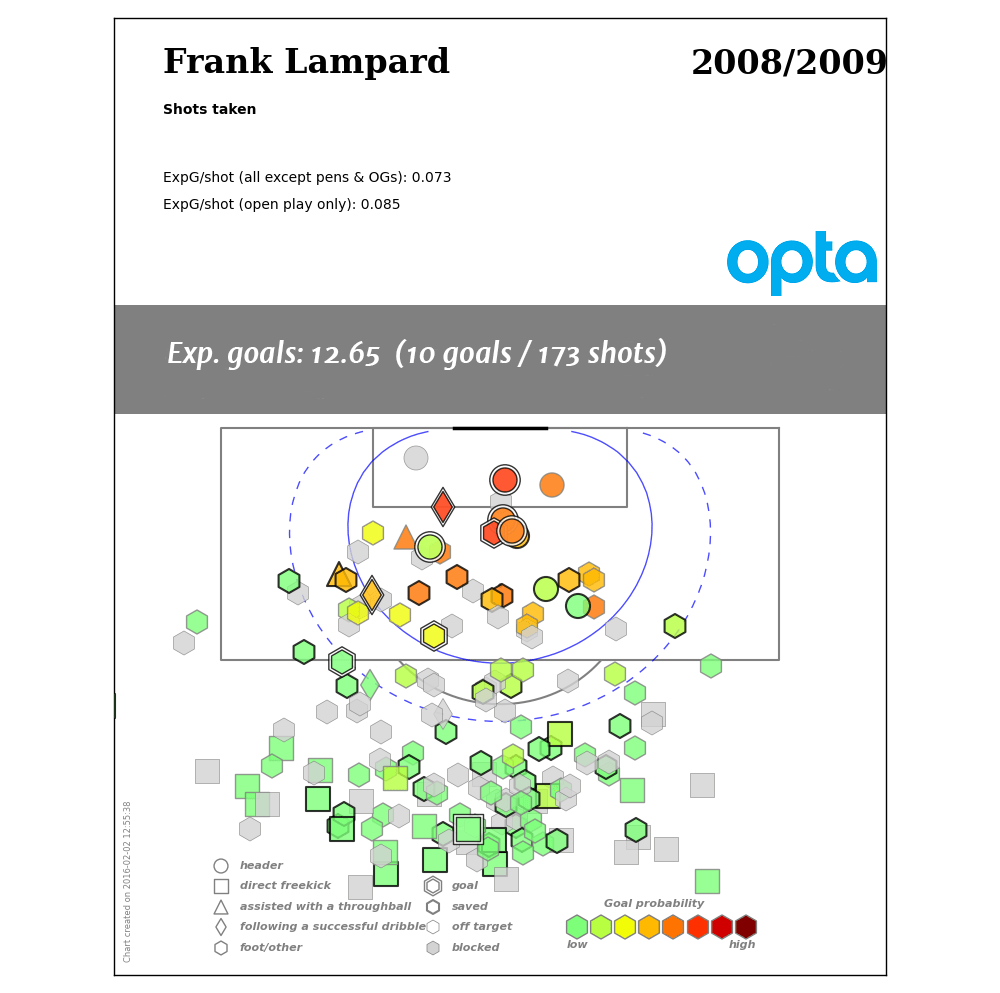

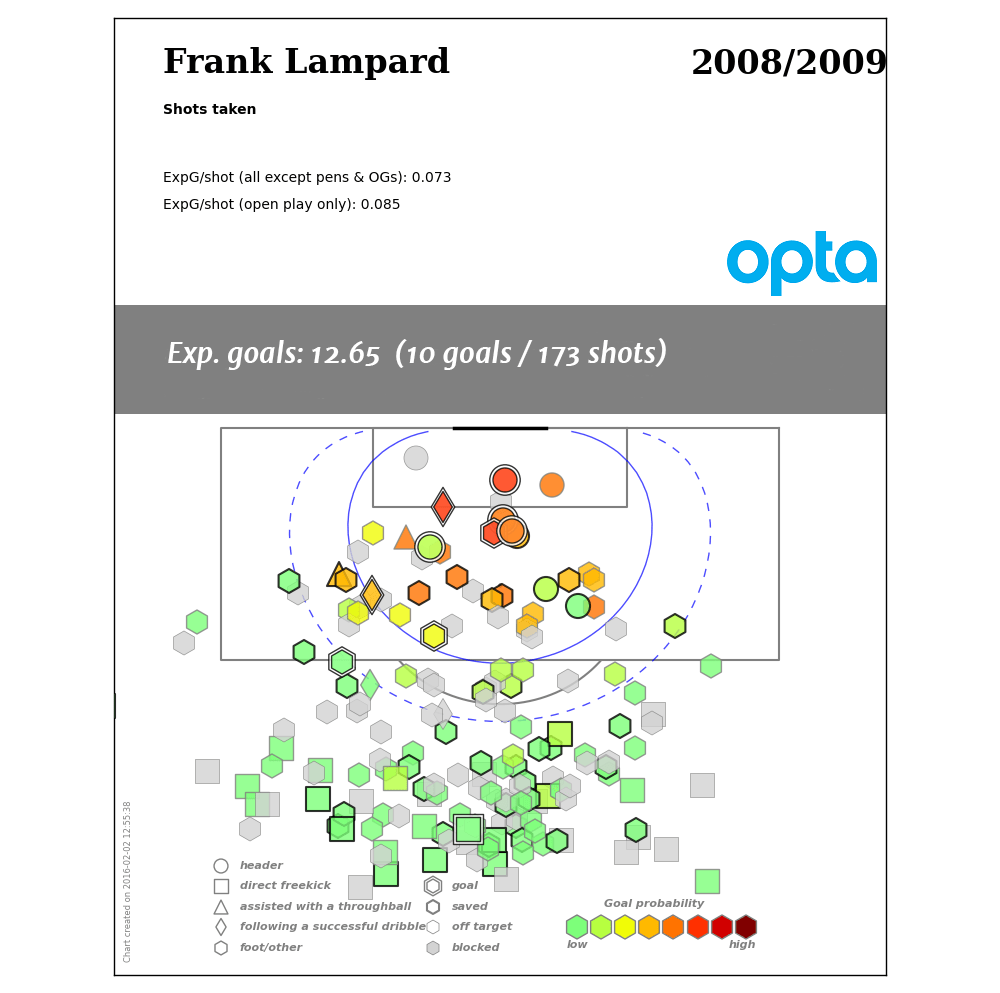

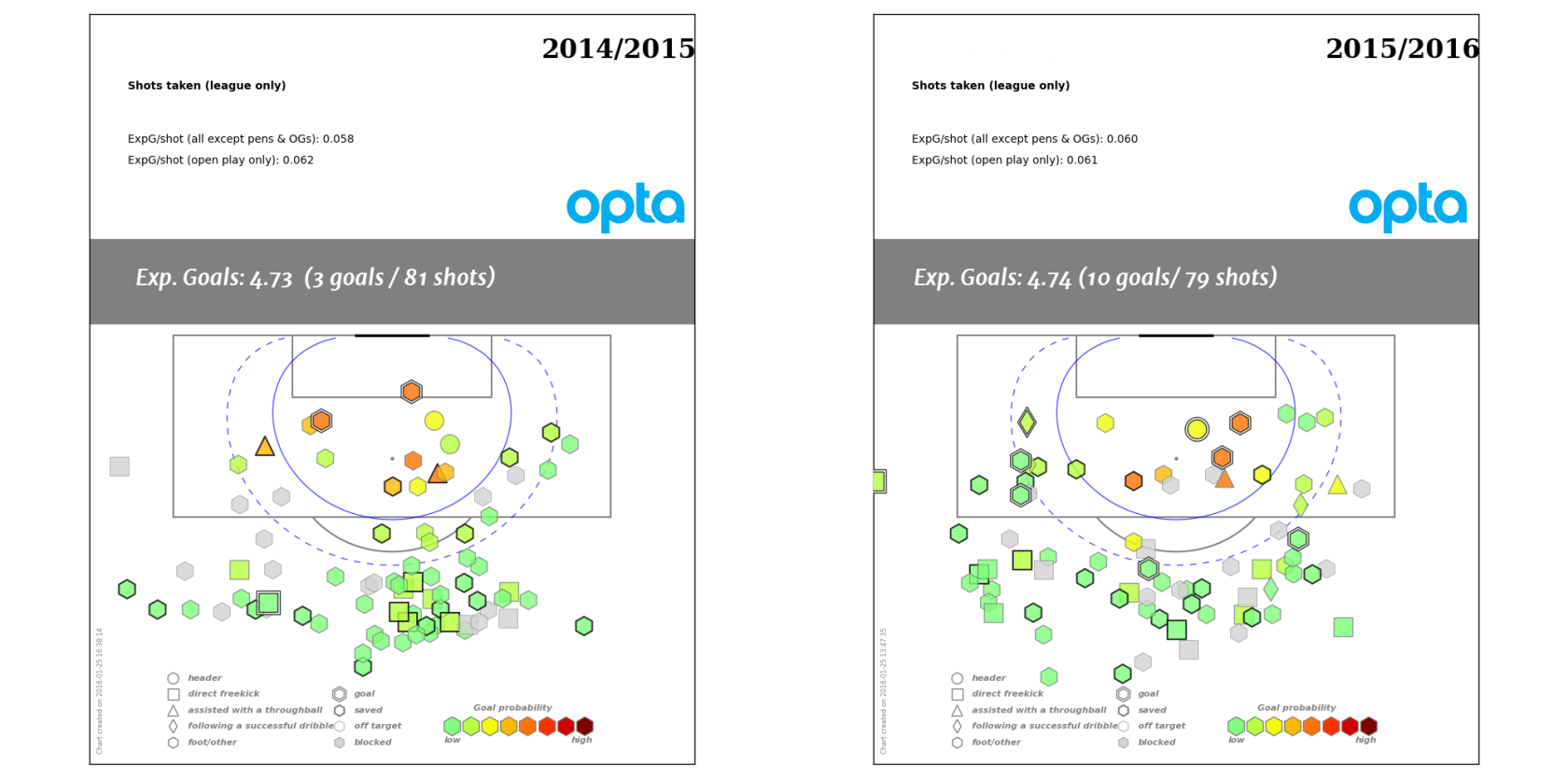

This is the same player, two seasons apart. As you can see, nearly every detail in this plot is identical except one thing: the goal return. In one season the player scored three goals and was considered good, but not great. In the next season, he scored 10 across almost exactly the same number of shots and was considered one of the best players in the league.

What changed?

Nothing.

His expected goals per shot were the same. His shot locations were almost shockingly similar, despite playing in a couple of different roles. And yet one season the goal return was below xG and the other it was basically twice expectation.

That’s the role that variance plays in the game and in our perception of player value.

Should it? Almost certainly not.

What about shooters who we are sure are good at shooting from long distance?

This is a question I get asked all the time whenever I present this information to coaches. "We know David and Frank are good shooters from long range – shouldn’t they be allowed to shoot from distance when they want to?"

The answer to this question and so many other ones in football is: Lionel Messi

Messi is assuredly one of the most skilled shooters in football. His accuracy from almost any range is precise and in many cases astounding.

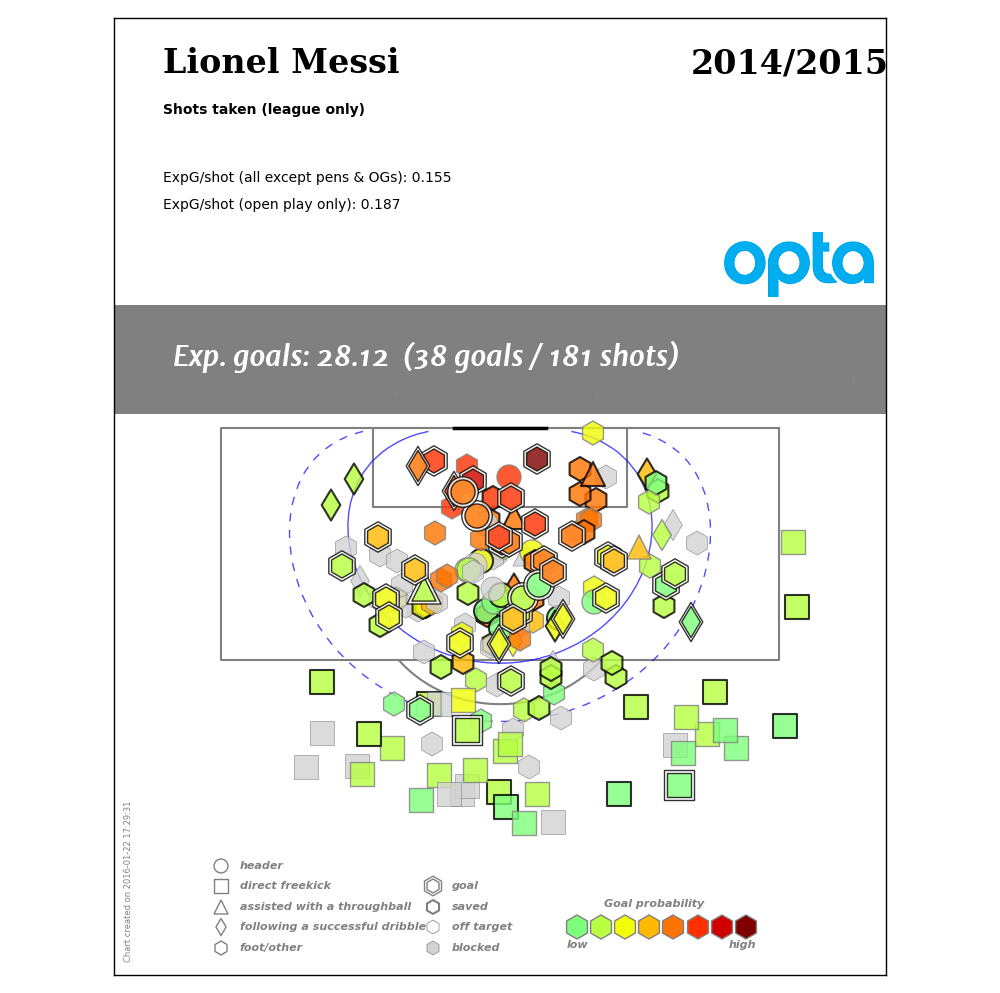

This is Messi’s shot map from the 2014-15 season.

Nearly every one of his 181 non-penalty shots that season were clustered in good areas. The ones that are outside the good areas are almost exclusively from direct free kicks. This is despite the fact that we know he is skilled at shooting.

The rationale behind this is simple: Barcelona know that shooting from prime locations makes them far more likely to score, which in turn makes them more likely to win. They pass up tons of possible shots over the course of a possession in search of a better one, a choice that few teams and players in the world make.

However, the teams that do make this choice tend to be the teams that have the most success.

To put it another way: if shooting only from prime locations is good enough for Leo Messi, shouldn't it be good enough for you?

How can we teach this to players?

There are many ways you can go about introducing and reinforcing the concept to players and coaches alike, but I have two favorites. One of these is an experiment and the other involves a bit of paint.

The Experiment

- Put two one-yard wide targets on either side of a normal goal, spanning the entire height of the goal.

- Mark out shooting locations at 9, 15, and 23 yards away from goal.

- Ask players to estimate how many of their own shots out of ten they expect will hit either target from each distance.

- Roll the ball to the players and have them shoot for the targets. Do this 10 times from each distance and record the results. (You can do this over a few days, and you can also do it multiple times over pre-season and early in the year.)

- Tabulate the results by individual and by population and present them.

The reasoning behind this easy: merely telling players about the concept is one thing. Having them learn it for themselves is a far more potent learning tool. Additionally, it teaches you a bit about their accuracy from distance in a laboratory setting. Game settings are obviously much harder, and you expect performance to be worse there.

Even if players are two or even three times as likely to score from 23 yards as an average player, that still only takes their expected goals per shot from that range from .03 to .09. This continues to compare poorly to the .40 you would get from completing throughball passes to runners into the box. That said, you also have learned who you are more likely to want taking long shots versus a packed defense to help mix up your strategy.

The Paint

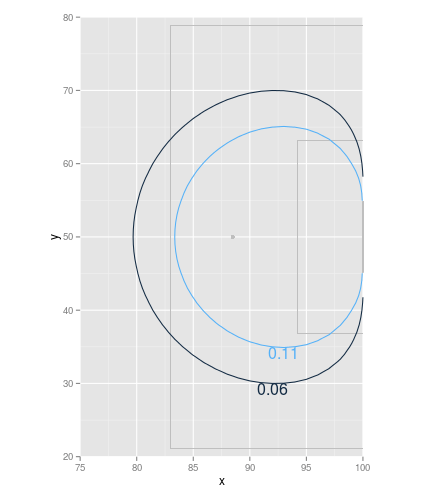

Explaining to players constantly about what is and is not a good shot annoys everyone and will wear thin pretty quickly. As an alternative measure, you can paint rings like you see on the shot maps on each of your training pitches. The solid blue line below corresponds to an 11% chance or better for a normal shot taken with feet, and it’s convenient because it basically rubs up against the 18-yard box). The black line is a 6% chance or better. Anything beyond these lines is considered a poor shot unless something special is going on (like a 1v1 with a keeper).

Explain to the players what the lines mean, and then let them evaluate themselves every time they take a shot. In behavioral economics terms, this is a nudge, and it’s one that will likely have a large impact across your entire club as time progresses. If the senior players in your team buy in to the concept and start to police it, you’ve already succeeded.

Other Ways to Reinforce the Concept

You have seen the shot maps above. A further method to highlight the issue to players is to review their own past shot locations and how successful they have been from each spot. Another way is to have them highlight past players they thought were good at shooting from specific locations and review how those players performed as well.

Almost inevitably, everyone remembers the long range screamer that went into the top 90. No one pictures the other 30 shots from that same distance that never turned into goals.

This is a classic example from a Premier League legend.