I have two major things on my agenda for today’s piece:

- Get a positively ancient Salt n’ Pepa song stuck in the heads of most of our readers simply by reading the title.

- To deliver a foundational piece discussing why we here at StatsBomb seem to care a great deal about pressing, both at the team and the player level.

However, in order to examine the press, we first have to discuss an often-overlooked topic in online football discourse: defending.

Defensive Choices and Principles

All tactical choices in football start with defending. Choices for how to defend strongly impact what types of players are needed across all the positions in the squad. The defensive structure of the team determines what is possible and necessary in the transition to attack. Regardless of what style of defending you choose, every system has inherent trade offs. High pressing leaves you vulnerable to high quality shots when opponents break the press. Deep blocks rarely restrict volume of opposition chances, but instead try to restrict the quality of those chances. Middle blocks try to strike a balance between restricting quantity and quality, but take high levels of organization and can concede too much space to dangerous players out wide. It’s worth noting that even inside these categories there remains a huge amount of variation.

Deep Block – Traditional English

This is the style usually employed by teams managed by Tony Pulis, Sam Allardyce, and weirdly enough, Arsenal. (Arsenal’s defense has been coached by Steve Bould, though Arsenal tend to include some mild gegenpressing.) It continues to see moderate success in the English lower leagues. Deep Block teams sacrifice control of the defensive half of the pitch in order to better control the area in and around the box. Defense of this style is typically happy to concede higher volumes of shots from distance on the assumption that few of these will be scored.

Middle Block (Portuguese and Italian Variations)

This style of defending is focused on jamming the middle of the pitch 20-40m away from goal with bodies, thus forcing opponents wide if they want to progress the ball. Progression through the middle is heavily contested, and progression wide often gets trapped, or results in easily cleaned up crosses. They will allow the opponent a ton of possession in “safe” areas, far from goal, but get aggressive as the ball approaches danger areas. Strengths of this style are that it blends some of the benefits of low block and high press together. Good middle blocks are excellent at constraining shot volume, while also leaving opponents with poor quality shots when they do get them. Antonio Conte’s teams are a good example of elite middle block teams, but it’s fairly common among well-trained Italian and Portuguese head coaches.

High Press – Many Variations

Pressing styles have gained popularity in the last decade, largely because of how successful they have been. Guardiola’s style is an elite positional press that almost no one in football really replicates. Thomas Tuchel’s press from his Dortmund days is probably the closest anyone has come, but still differs in execution. Jurgen Klopp’s press is also different from Guardiola’s, but has also been very successful over the years. It comes out of the Ralf Rangnick/Hoffenheim school of zonal pressure, but has morphed enough over the years from its roots that it’s probably unique. Then you get to the Salzburg/Roger Schmidt press, which shares common roots in the Hoffenheim school, but is now probably the most aggressive of the lot.

Those teams typically run a 4-2-2-2 formation, and are defined by a narrow, extremely intense pressing style that focuses keeping the ball high up the pitch in wide areas, and winning the ball back early to then immediately transition against the goal. Adi Hutter has also successfully used this style to dominate the Swiss Super League this past season, despite a fairly massive budget disparity when compared with Basel. The benefits of high pressing come from severe shot constraints to the opposition.

Elite high pressure teams can give up as few as 6.5 shots per match across a season, which is an absurd number. The flip side of this is giving up very good chances when opponents do break the press, which happens more against teams with talent or when your pressing side lacks pace. Additionally, this type of defending takes very high physical output, which can wear a squad down over a season, especially across multiple competitions. Finally, it requires serious athletes, with pace in nearly every position and some amount of tactical smarts, because the tactical concept of “covering shadows” is damned important. Note: Man-marking presses like the Dutch style are probably outmoded and tend to constrain the attack too much to function well in the modern day, especially in better leagues.

Traditional Defensive Stats

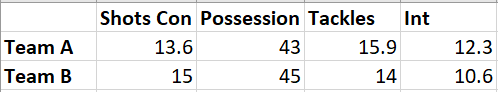

Historically, the defensive stats we had access to were tackles, interceptions, fouls, clearances, blocks, aerial wins, and fouls, plus a few minor additions. They are useful, but inherently limited in helping you evaluate team tactics and player output via data (and believe me, I have tried). Pressures as a type of event don’t exist in other event data sets, but they do in StatsBomb Data, and we think this is a Big Deal(™). Let me walk through some examples to better illustrate why. Take two teams from the English Premier League 17-18. These are their traditional defensive stats per game:

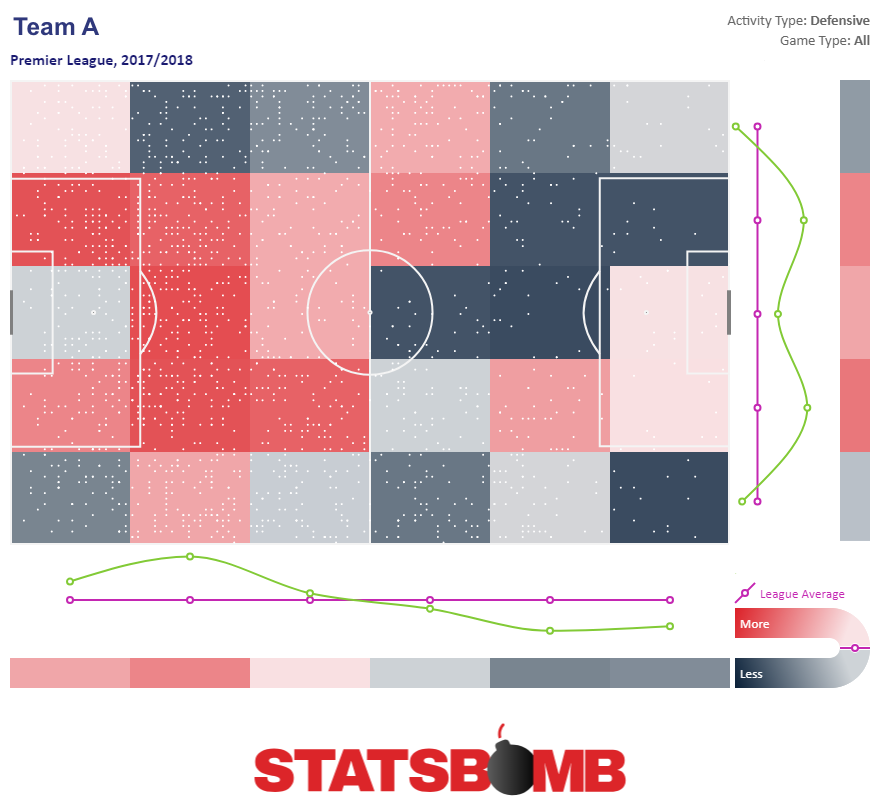

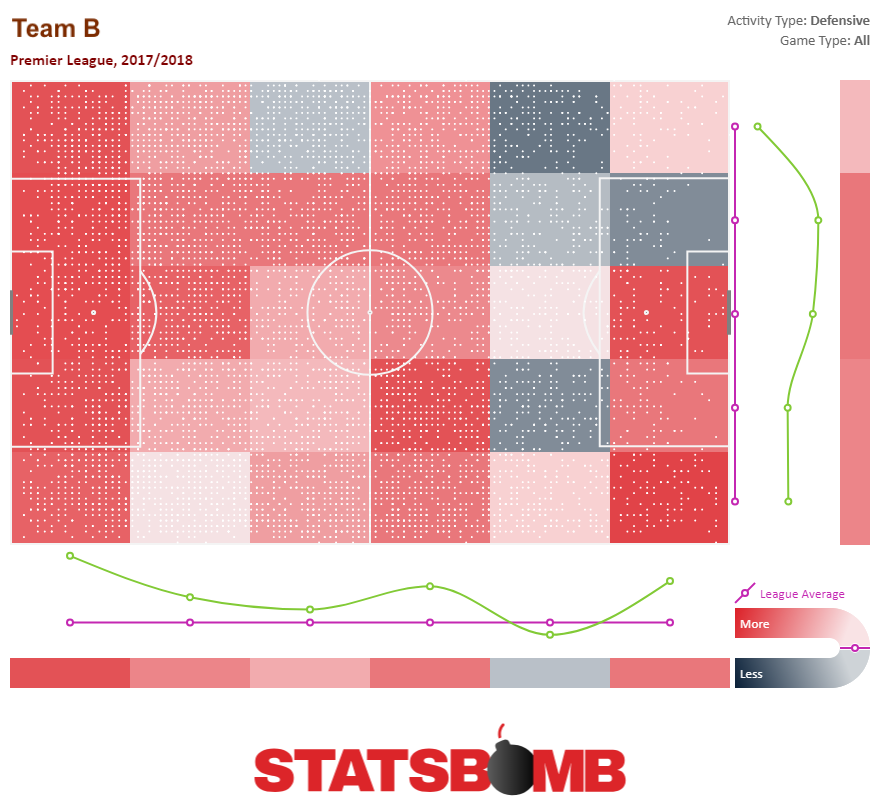

On the surface, there is very little separating these teams, and that includes when you look at their defensive activity maps. These visualisations plot where defensive actions occur on the pitch in each zone, and then colour them hot or cold compared to league averages.

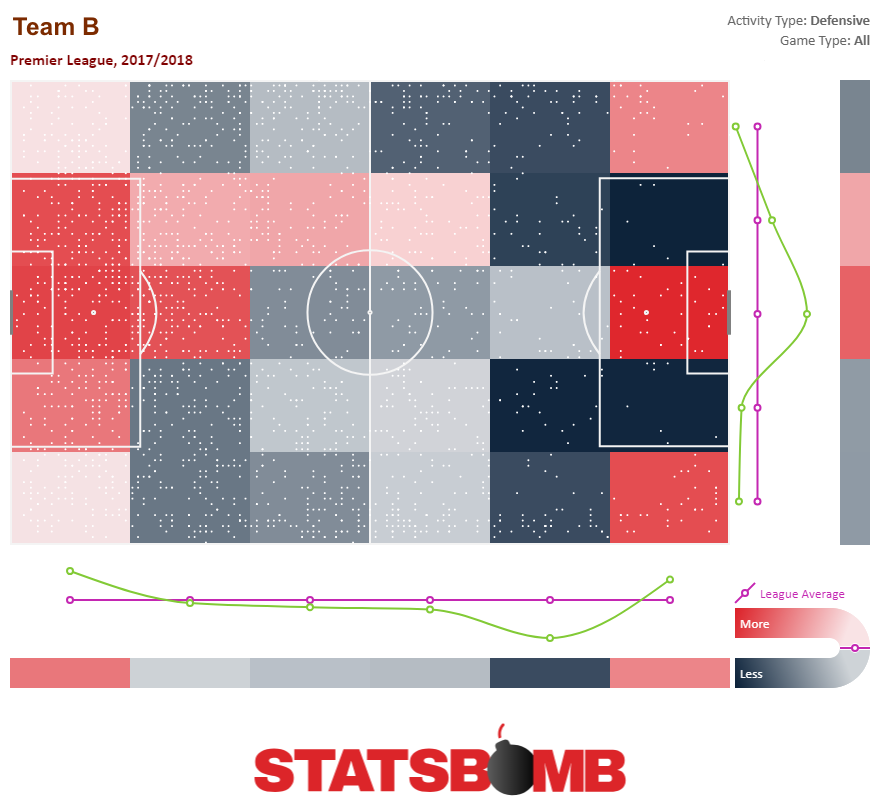

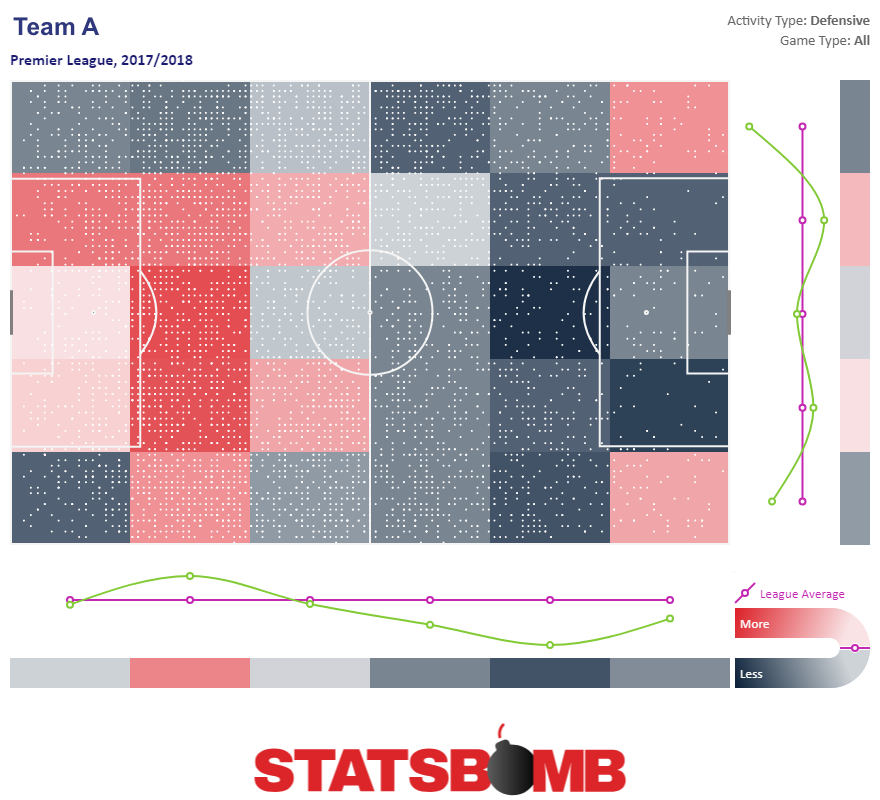

So it looks like Team A is a little more active defensively each match based on the stats, and they defend in very similar areas. But what happens when you add pressure data into the mix?

Team A looks basically the same compared to league average, while Team B looks complete and utterly different with the incorporation of pressure data. Now, instead of a traditional deep block, Team B looks absolutely miserable to play against. You simply do not get time on the ball against Team B almost anywhere on the pitch. Team A = West Brom Team B = Burnley These are two teams you could easily describe as Deep Block in style, but boy do they vary in execution when you play against them, and from a data perspective, you only see that when you layer in pressing information.

Pressure Players

Let’s drill down a little further into analysing individual players. Like many sports, football is an invasion sport. As in basketball and hockey, each team attempts to defend a goal, and possession is traded back and forth regularly between both sides. The two obvious questions about gaining an edge in this system then become:

- Can we get an advantage over our opponent in scoring chances or difference per possession, or trip up and down the pitch?

- Can we create more possessions?

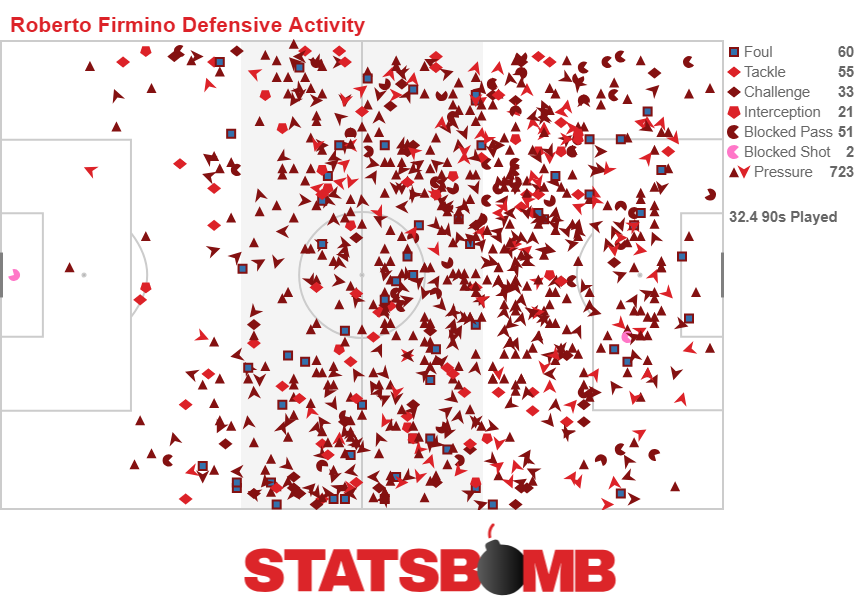

Traditional defensive stats usually reflect a possession change. Defenders can tackle or intercept the ball, they can get a ball recovery off a mistake, they can win headers, they can block/clear the ball, the ball can be claimed/saved by a Goalkeeper, and that’s about it. But there’s also one other thing they do more than anything else, that hasn’t really been recorded before: they can force mistakes. And that is where pressure comes into play. Take Roberto Firmino from this season.

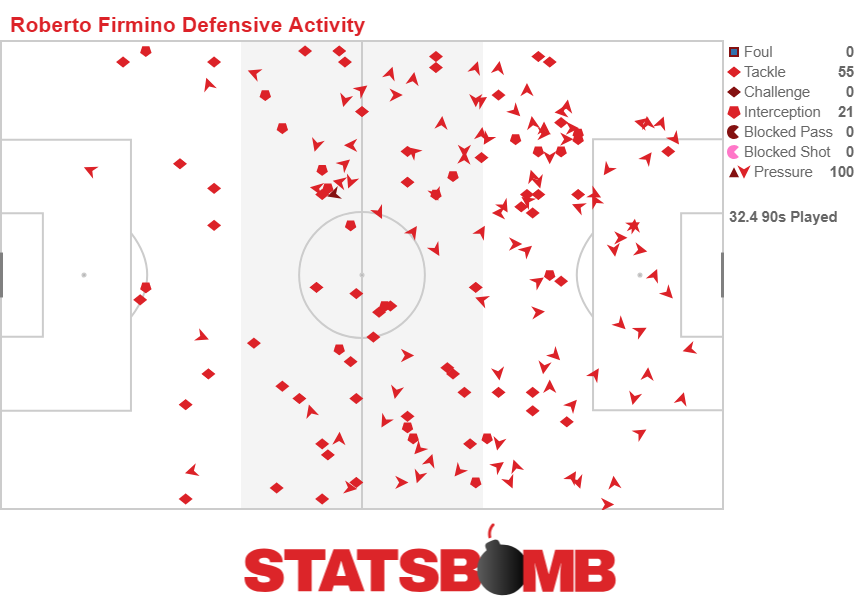

77 total tackles and interceptions... 723 pressures. The broad definition of a pressure is to close down an opponent in a way that forces them to make a decision. And sometimes - actually, LOTS of times - those decisions* fail and result in a change of possession. *Decisions, or actions under pressure, or inevitably, because Twitter shortens everything, AUPs Here’s Firmino’s map again, but this time with a focus on just those actions that resulted in an obvious change of possession (tackle, interception), or when his pressure caused the opponent’s action to fail (usually a failed pass).

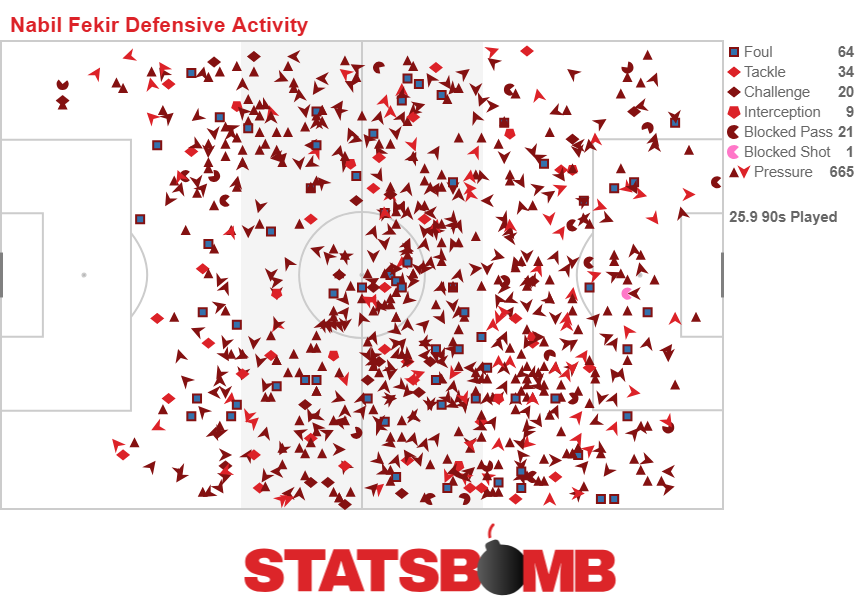

76 tackles and interceptions… 100 forced failures of actions under pressure. Nabil Fekir is an excellent player, and I’ve been high on his potential for years, but in addition to his attacking skills, he had a monster season pressing the opponent at Lyon. This extra layer of information reinforces why Liverpool should be interested in Fekir on any number of levels.

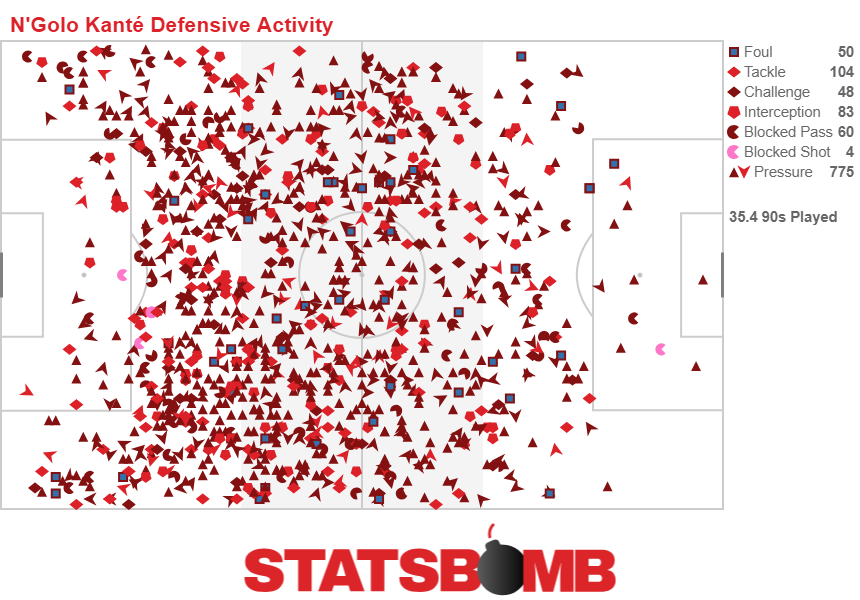

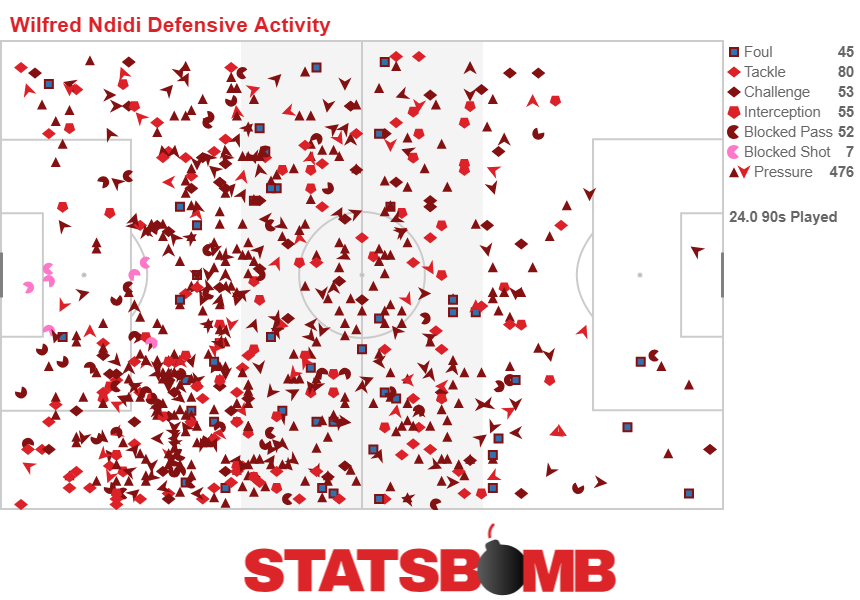

And it’s not just the hard-working, sometimes underappreciated forwards that benefit from this info, it’s also hard-working, often underappreciated defensive midfielders as well.

Kante is everywhere, but so is Ndidi, at least when it comes to defensive output. Kante's numbers are probably more exciting here because Chelsea tended to dominate possession more than Leicester this season, but both of these gentlemen Do Work.

Further Research

- The visualisations above only show failures caused immediately after/by the pressure, but sometimes a press is a destabilising factor for future actions in a possession. We can continue the filtering process to find possessions that broke down 1, 2, X actions after the pressure from a player to better attribute credit.

- For any particular match, we can look at who is being pressed, and specifically which actions are being put under pressure, and where. This can help in building game plans, but also in better evaluating where your own attacks are breaking down.

- How does pressing change over game time? With fatigue? After subs? Based on game state?

Thank you for listening to me ramble on about why we think pressure events are such a big deal when it comes to analysing football. We're admittedly just scratching the surface on the information from the new data set, but the new avenues for research opened by StatsBomb Data are incredibly exciting.

Ted Knutson

ted@statsbomb.com

@mixedknuts

Photo courtesy of the Press Association