Argentina are out of the World Cup, and all eyes are unsurprisingly on one man. The tournament is over, and now it’s time for the quadrennial tradition of arguing about whether it’s all Lionel Messi’s fault.

Messi generated the most expected goals of any Argentina player at the World Cup. He had the most open play passes into the box while still managing to get into the area for the second most touches in the box. He managed the most dribbles and the most shots of anyone in the squad. He had the most key passes and assisted the second most xG. All of this led to him reaching the joint highest total xGChain in the side. Yet, all it got him was a single goal, two assists, and an early flight home to a furious Argentine public.

To the shock of no one, there has been a strong reaction both in support of and critical of Messi. Inevitably this is heavily driven by club loyalties, with Real Madrid fans keen to attack him while Barcelona supporters desperately defend their man. But what exactly did Messi do in the World Cup? Were there choices he could’ve made to improve the side, or did his teammates simply fail him?

Game One - Unable to Break the Ice

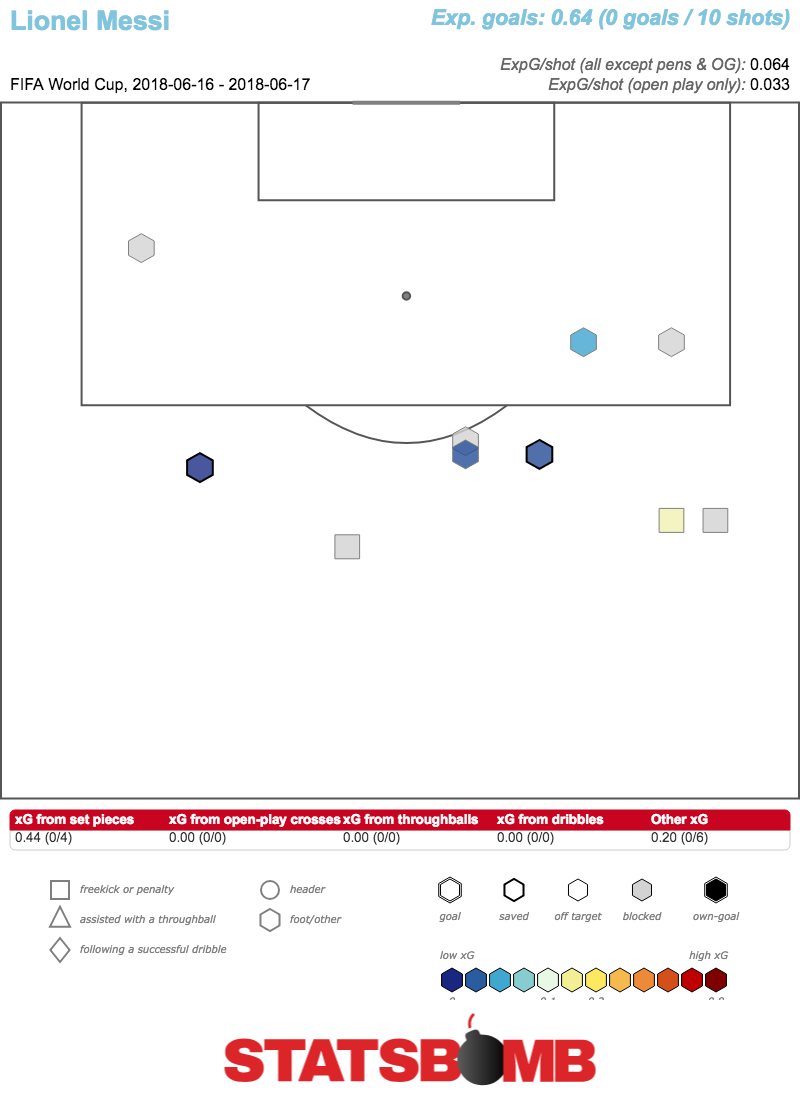

Iceland had a plan for stopping Messi and Argentina, one that certainly seemed to frustrate him. The main man registered ten shots in the game, more than half of his attempts in the entire World Cup. None managed to pose a serious threat, however, and he produced a shot map that matched the colours of La Albiceleste’s home kit.

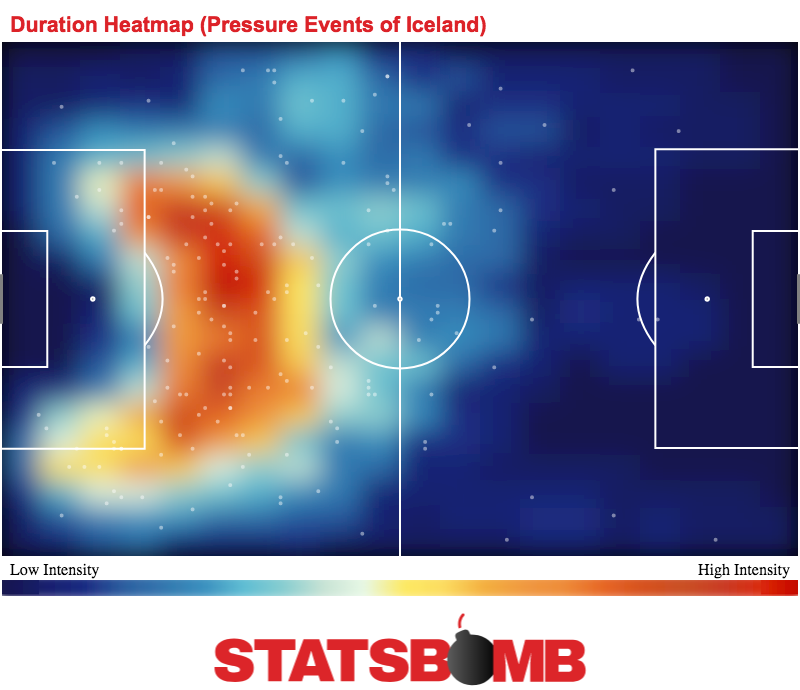

How Iceland managed to do this is not complicated, but it was still impressive in execution. Their low block 4-4-2 system was able to pack an abnormally large number of players behind the ball at any one time, not unreminiscent of Sean Dyche’s Burnley. When looking at a heatmap of Iceland’s pressure events, the gameplan becomes obvious: frustrate Argentina in deep positions around the edge of the box, making it extremely difficult to break through.

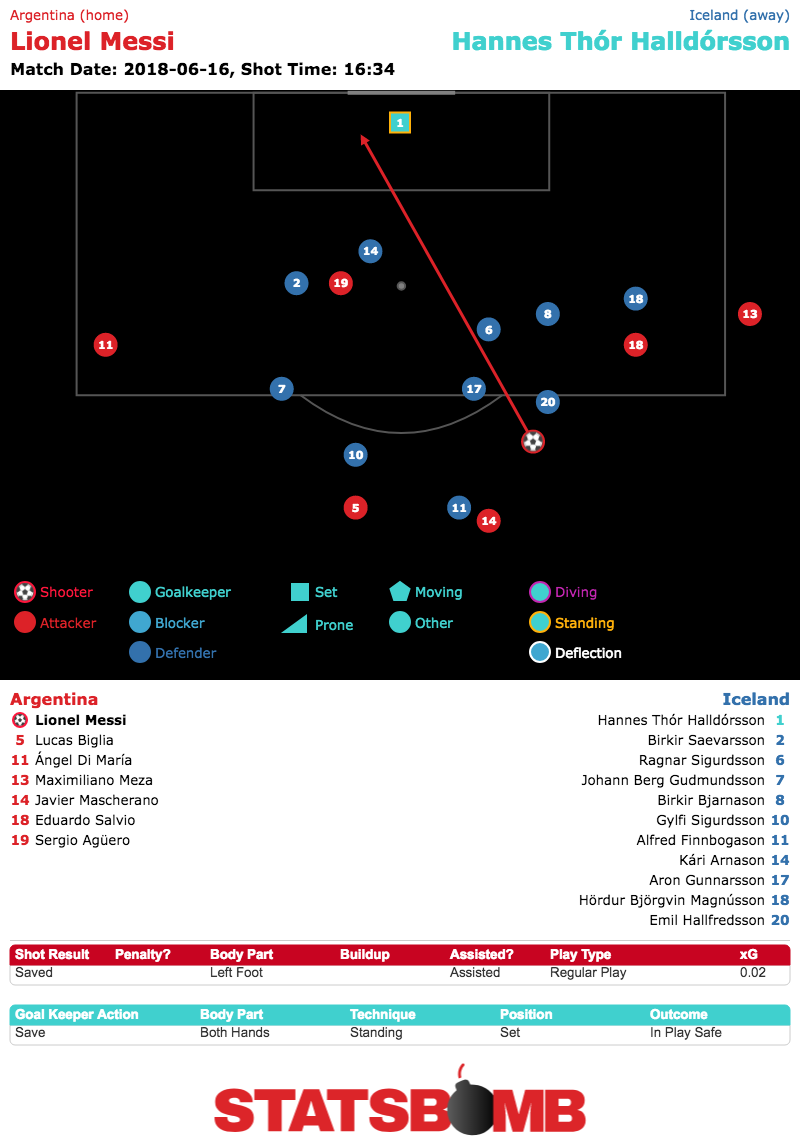

We can see this plan on the pitch too, with a full eight Iceland players behind the ball as Messi attempts one of his many shots from range. What’s even more notable is that this is at 0-0, long before a side would typically be settling for what they have.

While Iceland played well, their style wasn’t a surprise to anyone who had seen them at Euro 2016, and it’s not clear what manager Jorge Sampaoli’s plan was to break them down. Messi was nominally playing as a number ten behind Sergio Aguero, but he would often be seen drifting to his familiar right sided role or into a deeper midfield position to compensate for the lack of progressive passing from central areas. Giving one of the best players in the history of football licence to roam isn’t in itself a bad idea, so long as there is a clear structure around him. As it was, Maxi Meza and Ángel Di María in the wide roles were themselves often coming inside. Had they held their positions on the flanks, this could have stretched Iceland’s compact block and created some space for Messi in central areas. But they didn’t, so the whole thing was without structure and this allowed Iceland to easily keep their compact shape.

Messi was extremely isolated in this game, a number ten standing between the lines alone, surrounded by two Icelandic banks of four. Argentina’s only thought to break down the deep block of Iceland was to give the ball to Messi and let him figure it out, which, yes, he was unable to do, but there really should’ve been another idea.

Game Two – Pressed by Croatia

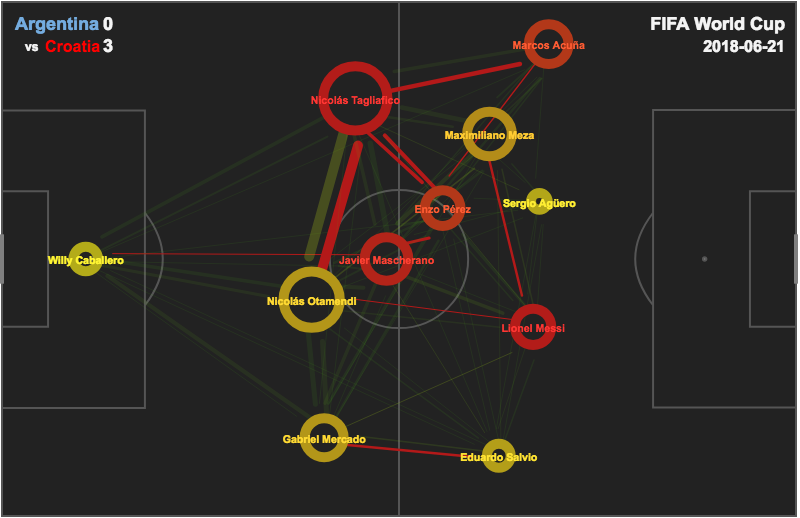

Considering the structural problems in the first game, it wasn’t a huge shock to see Argentina change formation against Croatia. The new system was a 3-4-3 in possession (though it often looked more like a back four without the ball), seeing Messi and Meza both take up number ten roles behind Aguero. The idea behind this appeared to be an attempt to fix the structural problems against Iceland, with Marcos Acuña and Eduardo Salvio taking up wide positions as wing-backs to stretch the play and free up Messi.

There is one obvious problem with this approach, however. Croatia’s style could not be more different to Iceland’s. If Messi’s first game was best understood by shot quality, his second can be seen through the lens of volume. After ten shots against Iceland, he managed just one attempt against Croatia.

Yes, you read that right.

One.

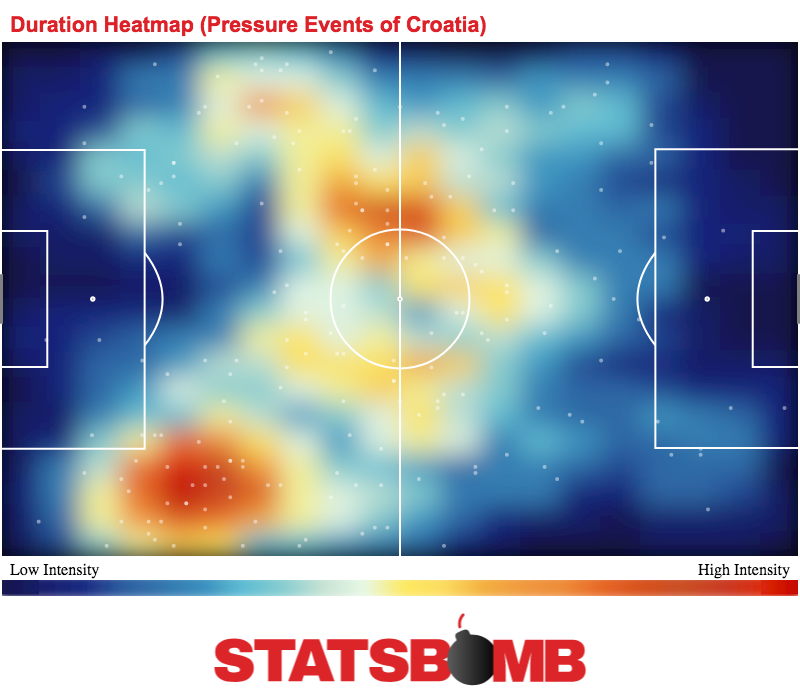

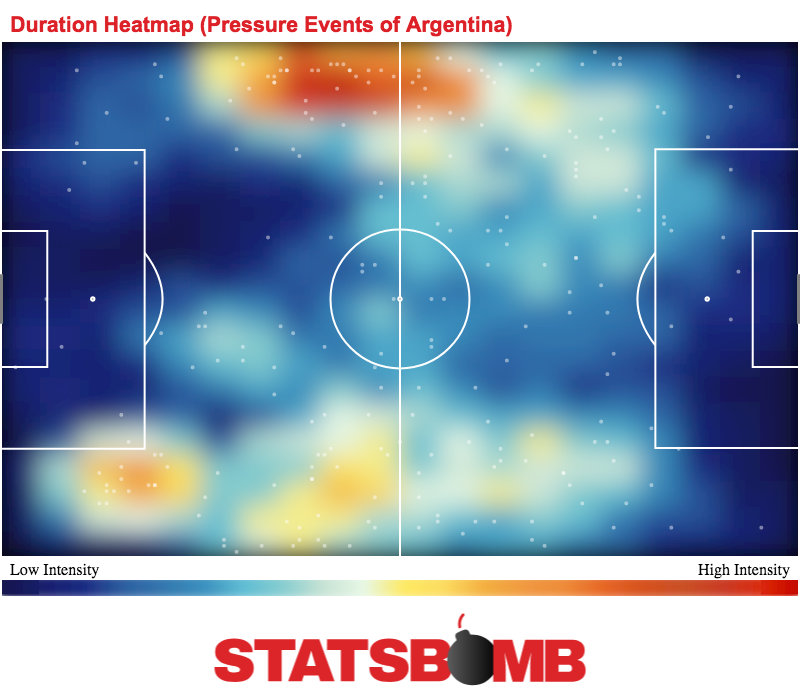

A fairly basic idea about defending in football is that a deep block will look to blunt the opposition’s shot quality, forcing them into attempts from range, while a more aggressive high pressing system will attempt to stop the problem at the source and limit the number of shots conceded. Looking at a heatmap of Croatia’s pressure events, it becomes obvious that they were much more interested in causing problems for Argentina in midfield than Iceland were, trying to prevent the ball from even reaching the final third.

Meanwhile, Argentina’s approach seemed to be to press Croatia most aggressively in wide areas and allow them to play through midfield. You know, the midfield with Luka Modrić and Ivan Rakitić.

Whether this was a deliberate strategy, or simply the result of Croatia’s midfield taking advantage of Argentina’s ageing legs is unclear, but either way it was obviously suboptimal. One of the central themes of the game was Croatia winning the ball in midfield and using Modrić and Rakitić’s excellent passing range to quickly get the ball to the attacking players. That Croatia’s front three effectively got to have a 3 vs 3 contest with Argentina’s back three was also not ideal.

The kindest thing to be said from an Argentine perspective is that expected goals saw it as a much closer contest, with StatsBomb’s model evaluating it at 1.74 to 1.35 in Croatia’s favour (though the game state must be noted here, with Argentina continually having to create new attacks while Croatia were in a comfortable position for most of the game). In fact, the two sides were neck and neck until Rakitic’s excellent 91st minute goal to make it 3-0. The other two goals were from a brilliant Luka Modric strike from range and a terrible mistake by goalkeeper Willy Caballero, hardly systemic issues. Messi himself had the highest xGChain of any player on the pitch, showing that he was involved in Argentina’s gameplay, even though he wasn’t able to make many decisive contributions. Even if there were unheralded positives from this game, the manner of defeat again led to Argentina throwing everything out and trying a completely different system.

Game Three – Just About Good Enough Against Nigeria

For the final game in the group stages, a match that Argentina absolutely had to win, the side switched to a 4-3-3 formation. Whether this was purely Sampaoli’s decision or it was heavily influenced by the players is something we’ll never know, but it had several effects on the team. Obviously this system gets an additional central midfielder into the side, which may have been another reaction to the problems in the previous game.

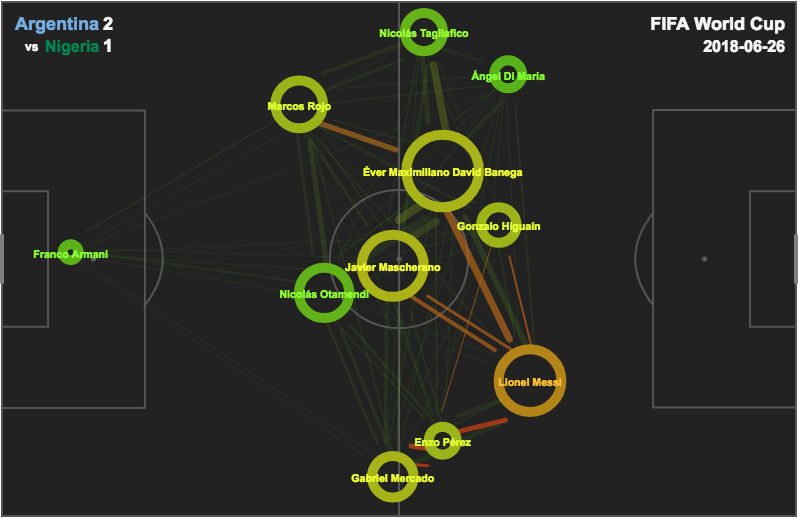

It also helped that said extra midfielder was Éver Banega, one of the best progressive passers in European club football. The other notable shift was that Messi himself now played on the right of a front three, a position he has played a lot for Barcelona. This allowed him some more space, and the new position along with Banega’s ability to find him let him take a very involved role in the proceedings. Looking at the passmap, it’s obvious how much of an emphasis there is on getting the ball to Messi down the right flank.

And so It followed, Messi scored his first goal of the tournament, Argentina got a 2-1 victory and made it into the knockout stages. It worked!

About that…

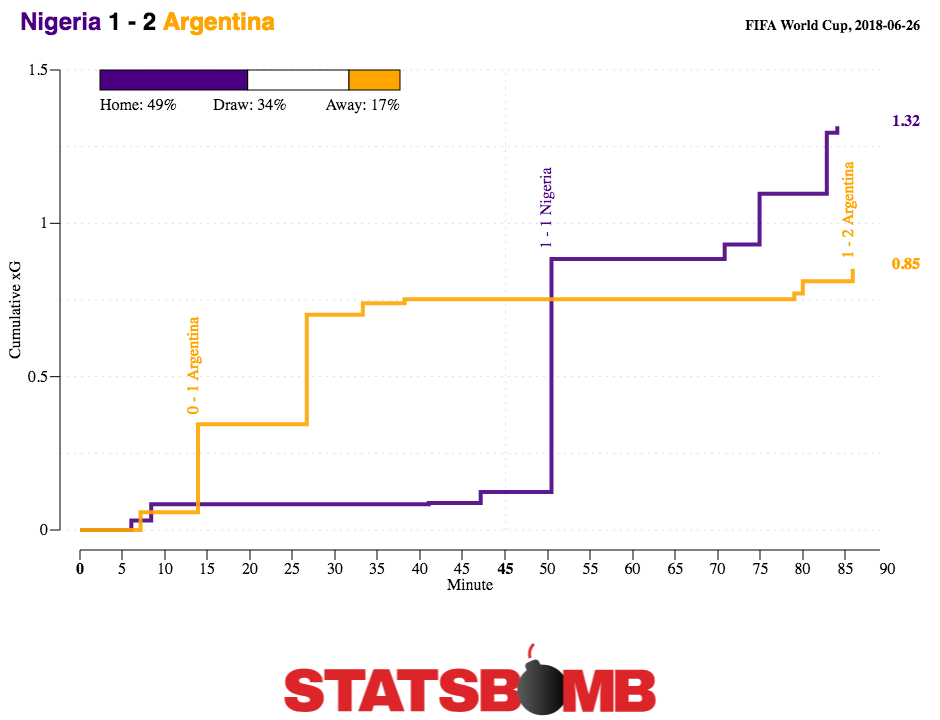

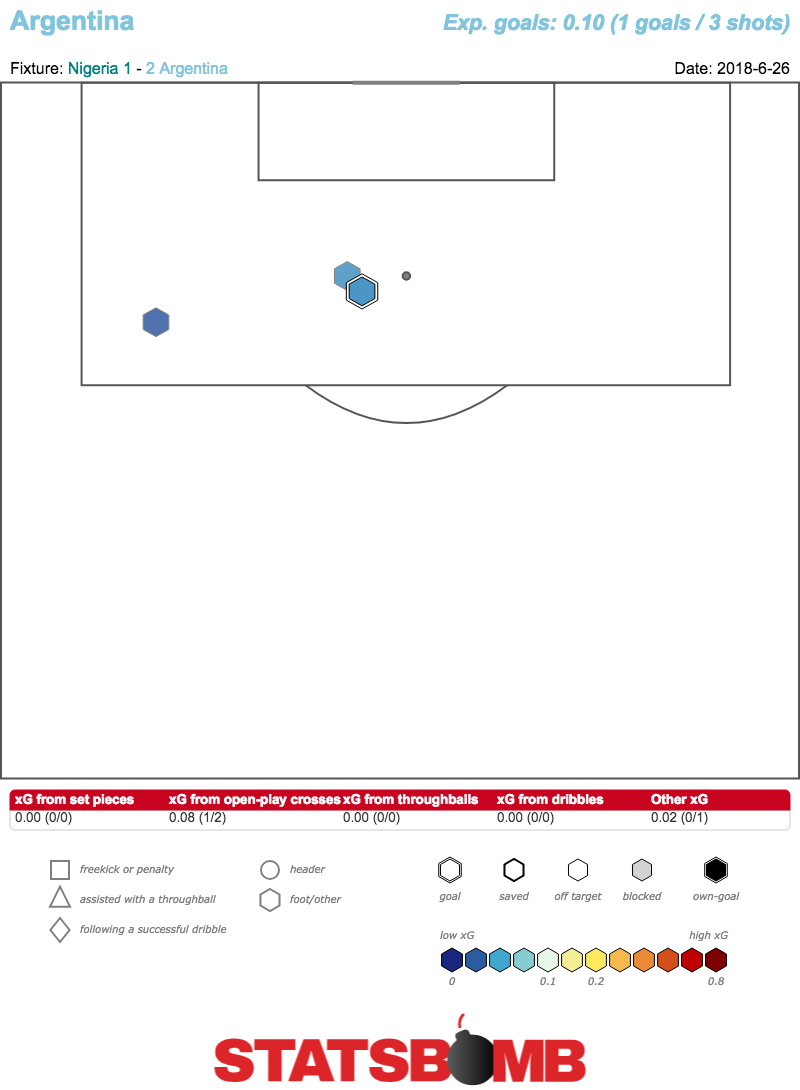

Argentina were able to generate very little against Nigeria, and when one includes the penalty they conceded, expected goals has them as a clear second best.

And the penalty itself was the crucial factor in the game. While the incident itself against Javier Mascherano was a debatable one, it allowed Nigeria to focus on defending in more of a deep block that Argentina would need to break down. And in switching to this, they limited Argentina to just 3 shots over 40 minutes, with a total xG of 0.10.

That Marcos Rojo happened to connect well with a cross should not cloud what a poor attacking performance this was. One of the most frequent images of the game was of Argentina players with no genuine passing options, thanks to the extremely poor structure of the side. This was just enough to get through the group stages, but it was obvious that any side of higher quality would put them at serious risk of elimination. Which brings us to…

Game Four – Beaten on the Counter by France

There was only a single tactical change for what proved to be Argentina’s final game in the competition, but it was a significant one. After looking fairly comfortable on the right of a front three against Nigeria, Lionel Messi started as the central striker against France. As anyone who watched Barcelona in the first half of this decade will remember, Messi interprets the striker role very much as a false nine, dropping deep and looking to play short passes with the central midfielders.

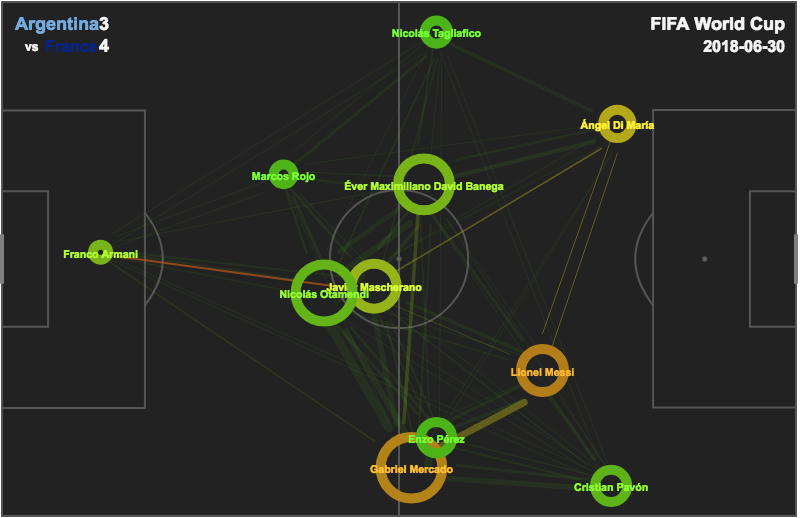

This is fine and can be a very effective tactic providing other players are making runs beyond the striker and into the box. Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona side exemplified this with wide players such as Pedro and David Villa positioned narrow in order to exploit the space Messi vacated. Sampaoli’s side, however, opted to have Ángel Di María and Cristian Pavón take up very wide positions on their natural sides, as is visible from the passmap.

Throughout the game, Messi would drift around the halfway line, looking to receive the ball, while Di María and Pavón would stay wide waiting to cross the ball to… no one. A further indictment from the passmap is that, despite often moving into midfield areas, Messi made almost no decent connections with Éver Banega, Enzo Perez and Javier Mascherano. Despite specialist passing midfielder Banega being in the side primarily to get the ball to Messi in dangerous areas, the strongest passing link Messi had was with right back Gabriel Mercado.

What lost this game for Argentina was an inability to deal with France’s pace on the counter. Much was written about how this match represented a changing of the guard, with Messi looking past his best and Kylian Mbappé rising as football’s new superstar. What the French side understood was that the most effective way to use Mbappé in this game was to have him running into space, with balls over the top putting him in a footrace against Argentina’s ageing defenders and midfielders. Argentina, however, had no real idea of the best way to use Messi in this game. It seemed as though he was playing the false nine role mostly because it’s a position where he has done well in the past, but the rest of the team seemed to be built as though a true striker such as Gonzalo Higuaín or Sergio Agüero would be playing there.

Conclusion

Argentina played four games at the World Cup and managed to pull out four entirely different systems. Astonishingly, none of these systems actually seemed set up to deal with the problems that the opposition of that day would cause, and it often just felt like the lineups were attempts to fix whatever the problem was in the last game. That they kept changing strategies without ever addressing one of the core issues of ageing legs in midfield is quite odd, though may speak to the dressing room dynamics rumoured to be at play in the squad.

Messi was central to everything Argentina did, but almost by default more than any systematic plan to get the most out of him. Having a star in your side with such a rich and varied skill set can often pose problems about how best to use him, but one can at least attempt to create familiarity with a coherent side. Messi failed to deliver the decisive moments his country needed to progress further in the World Cup, but it is almost impossible to argue that he was given the best platform to do it.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association