We complete our data history of the European Cup with the all-Bundesliga final of 2013. After seeing off the Spanish giants in their semi-finals, Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund met at Wembley, each seeking to become the first German winner in over a decade. This is the sixth and final part of the series.

We’ve previously covered: - 1960: Real Madrid 7 - 3 Eintracht Frankfurt - 1972: Ajax 2 - 0 Inter Milan - 1989: AC Milan 4 - 0 Steaua Bucharest - 1995: Ajax 1 - 0 AC Milan - 2009: Barcelona 2 - 0 Manchester United

Bayern were the favourites coming into the match, having run away with the Bundesliga and traversed a difficult route to the final that included a historic 7-0 aggregate thrashing of Barcelona in the final four; Dortmund had come ever so close to elimination against Málaga in the last eight before then seeing off Real Madrid to make it through to the final.

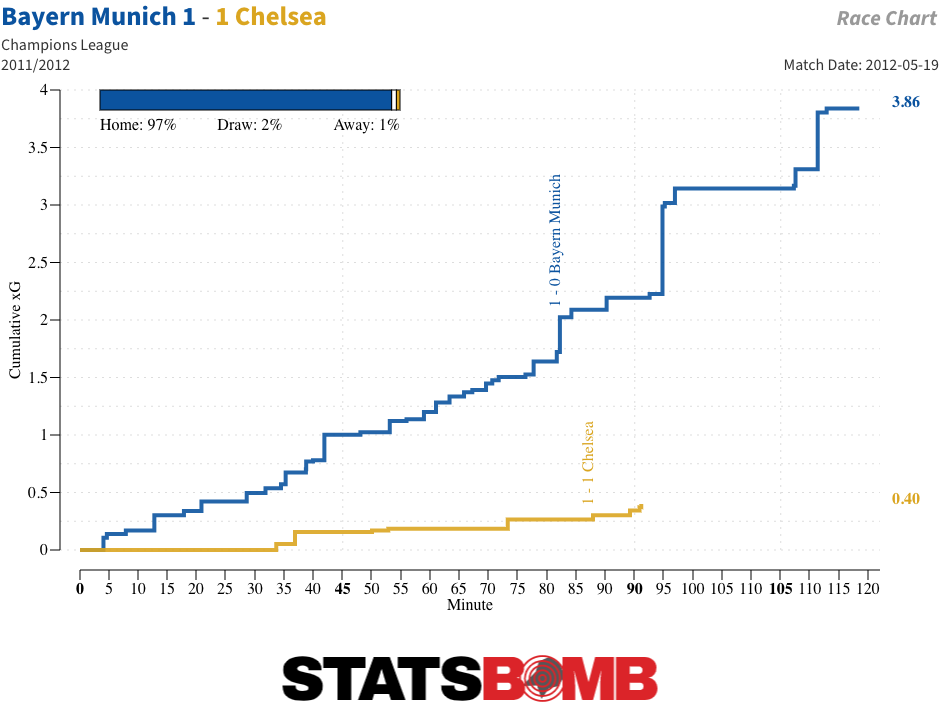

Bayern had been extremely unfortunate to lose out to Chelsea in the 2012 final and were seeking to make amends and send coach Jupp Heynckes off into retirement on a high with victory.

New Style, Vintage Results

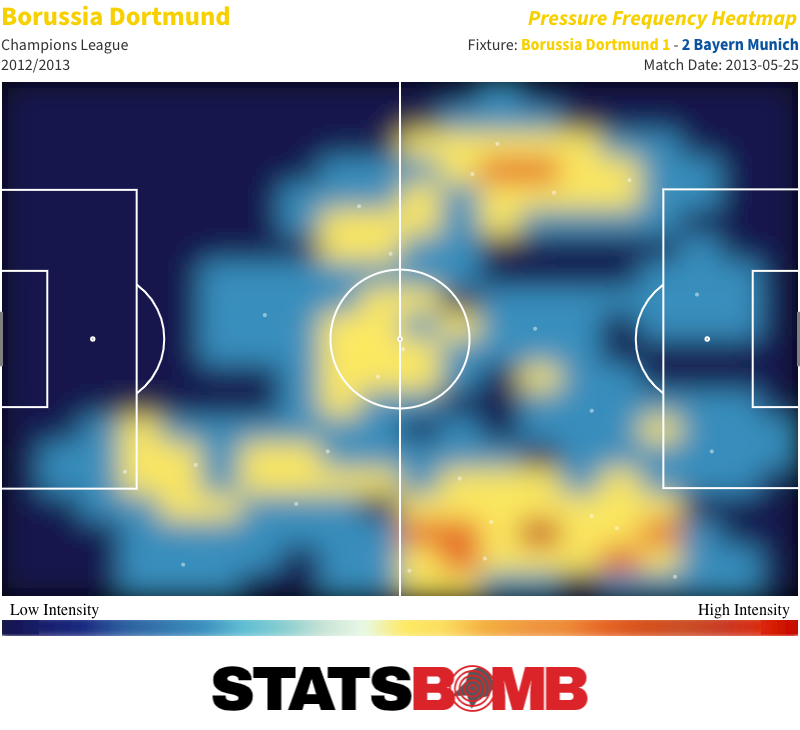

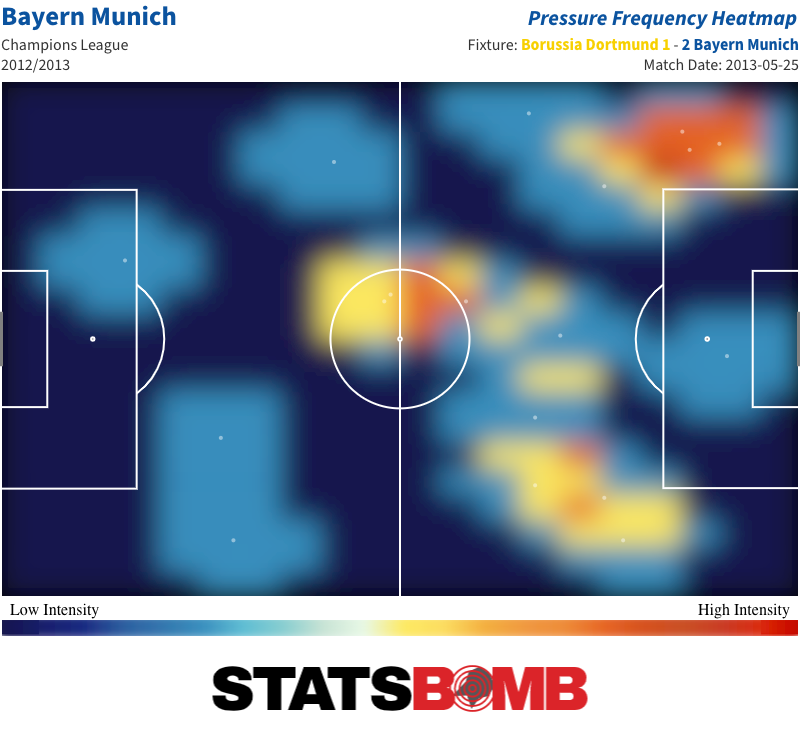

Just as we seemed to have settled into a stylistic tussle between patient possession and deep block defending, along came the Germans to upset the apfelkarren. Suddenly, the attention of the footballing world shifted to the Bundesliga. Gegenpressing (later translated as counterpressing) firmly entered the football lexicon and there was much talk of the importance of transitional phases of play.

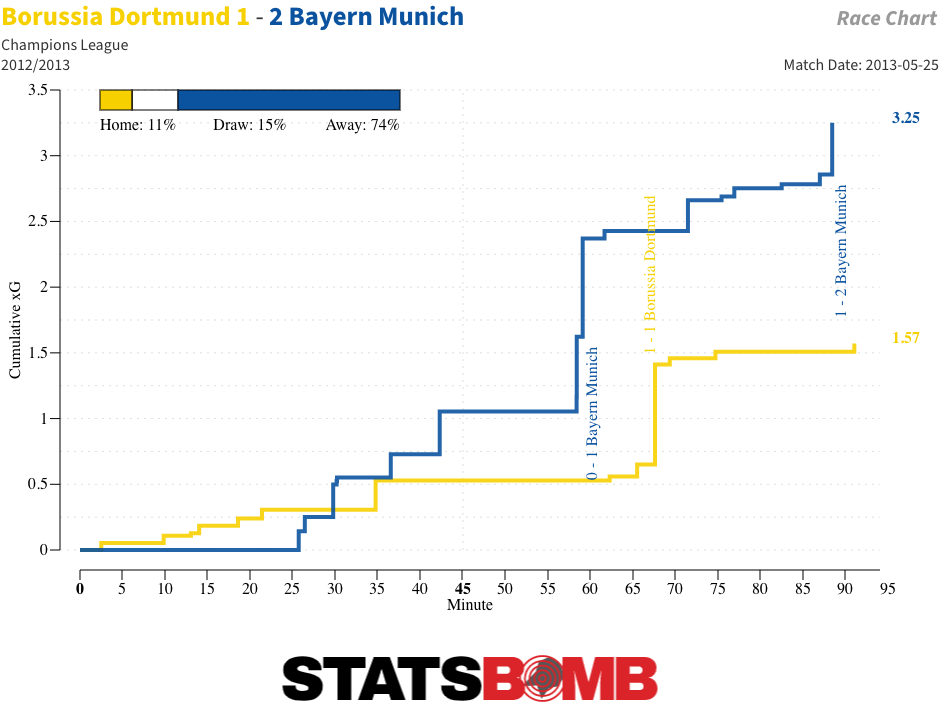

The meeting of two German sides at Wembley produced a high-paced encounter that was actually closer in style and output to the 1960 final that any of the others we’ve covered in this series. The shot count was nowhere near as high, but the 2013 final nevertheless sits second only to 1960 in terms of the expected goals (xG) total, although that was heavily tilted towards Bayern.

There was also some of the frantic, back-and-forth play of that early final on display. The average speed of attack was the fastest of all the finals we’ve covered, faster still than in 1960. Dortmund were especially swift to transition forward after gaining possession.

The average pace towards goal for teams in last year’s Champions League was 2.53 metres per second; Dortmund raced forward at a rate of 4.61 metres per second. Not that it lead to a particularly dangerous set of shots. Jurgen Klopp’s team began on the front foot, getting off six efforts on goal before Bayern had even mustered one, and accumulated 12 over the course of the 90 minutes.

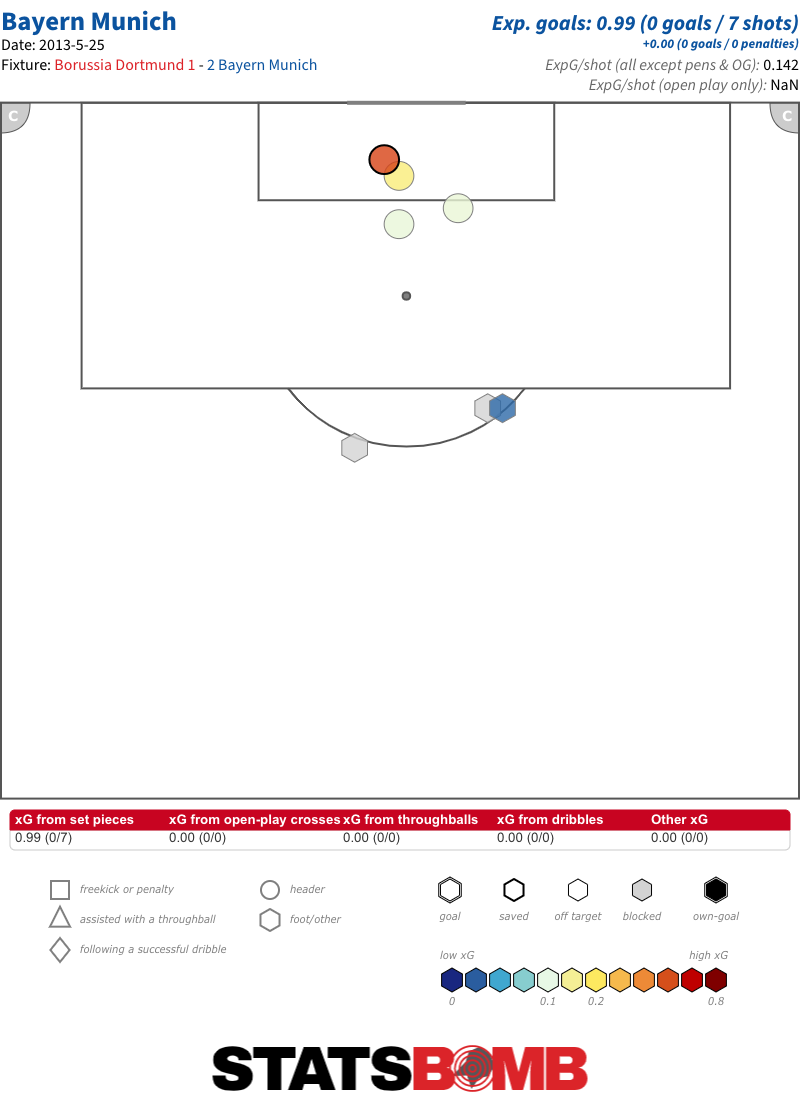

But even with Robert Lewandowski, scorer of all four goals in Dortmund’s 4-1 thrashing of Real Madrid in the first leg of their semi-final and impeccable in his use of his body to shield the ball and turn defenders, and an effervescent Marco Reus among their starts, they not only managed five less shots than Bayern, but the average quality of those shots was also far below those of their opponents. Despite a heavily aerial attack, there was very little fat on the Bayern shot map.

Remove Dortmund’s penalty from the equation and they created under one expected goal. It may have taken Bayern until the 89th minute, when Arjen Robben skipped between two defenders and finished neatly to finally enjoy success in a major continental final after two failed attempts at the Champions League with Bayern and a World Cup final defeat with the Netherlands, to score their winner but it was clearly deserved. Robben and Thomas Müller had been involved in much of their best play.

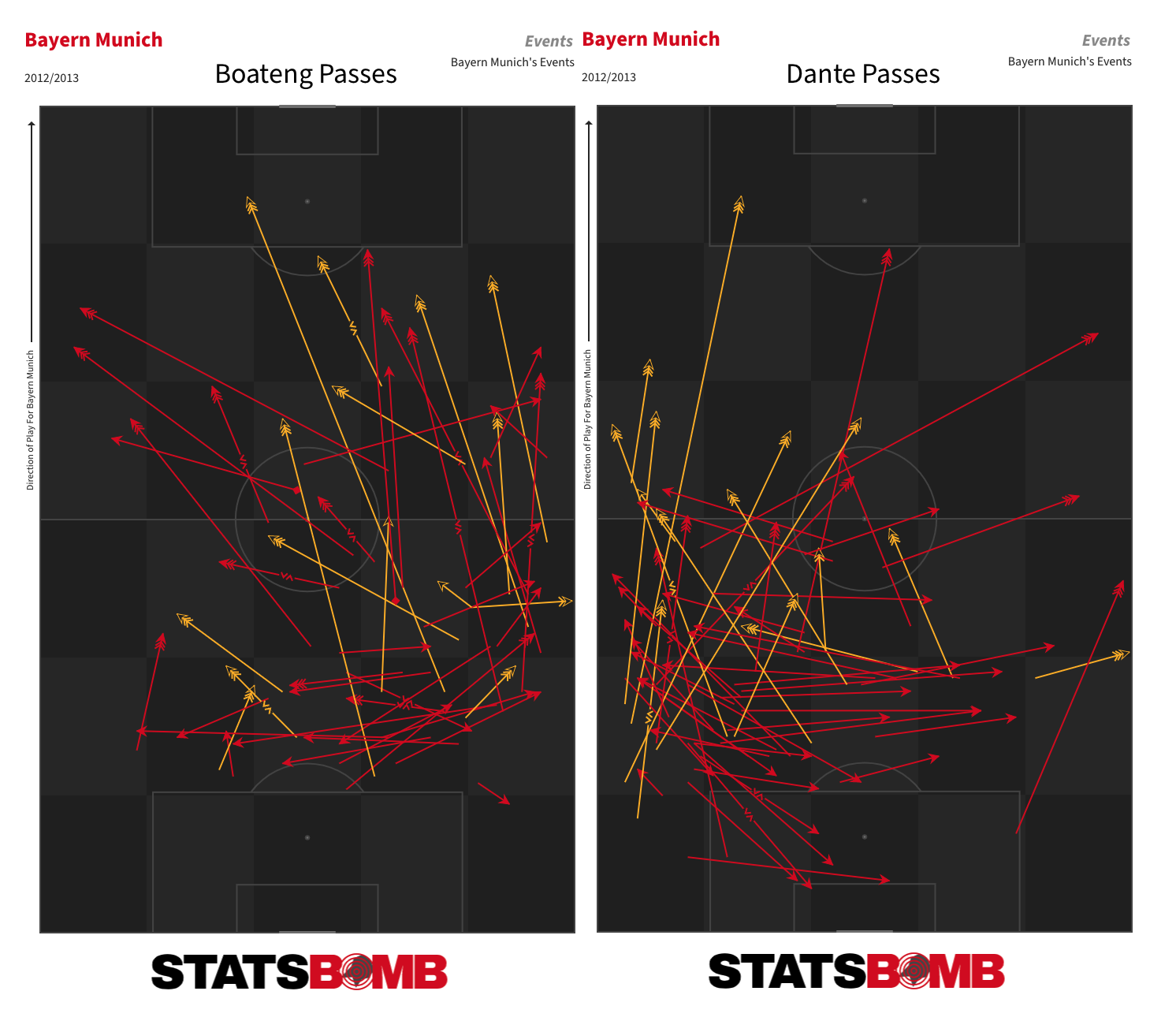

The pace with which the two teams attacked saw them regularly turn over possession. Even Bayern’s more patient buildup in deeper areas usually eventually resulted in a long ball forward from one of the two central defenders.

The final featured the lowest passing completion percentage of any since 1960, with just a 71% completion rate -- nearly four percentage points fewer than the next lowest. Dortmund’s 65% rate was the first time since 1960 that a team had dipped below 70%.

Not only did it stand out in comparison to the other finals in this series but also within the context of contemporary finals. The completion rate was the lowest of all those contested in the 2010s. [table id=82 /] And that’s the thing. For all that this was heralded as a new dawn in football, it didn’t start a revolution nor did it herald a new era of German dominance.

The national team won the following year’s World Cup, but did so with a more possession-dependent style of play. At club level, Spain came back strongly, with Barcelona and Real Madrid lifting the Champions League trophy in each of the subsequent five seasons -- four times in Madrid’s case.

Germany is yet to provide another finalist.

Such is the widespread availability of footage in the modern age that even before Bayern and Dortmund took to the pitch at Wembley, their ideas had already been acutely analysed and elements incorporated elsewhere.

They didn’t enjoy the same sort of extended advantage that a novel play style afforded Inter Milan in the 1960s or Ajax in the 1970s, for example. The totals for counterpressures and counterpressures in the respective attacking thirds in this match fell on or below the average points for those metrics during last season’s Champions League.

What was once unique quickly became commonplace.

Pep Guardiola’s arrival at Bayern in the summer of 2013 and some of his innovations, including narrowly positioned full-backs, also provided ready examples of how possession-based teams might seek to better protect themselves against rapid transitions. Add all that up and this final almost feels like a rapidly resolved glitch in the system.

Dangerous Bayern Corners

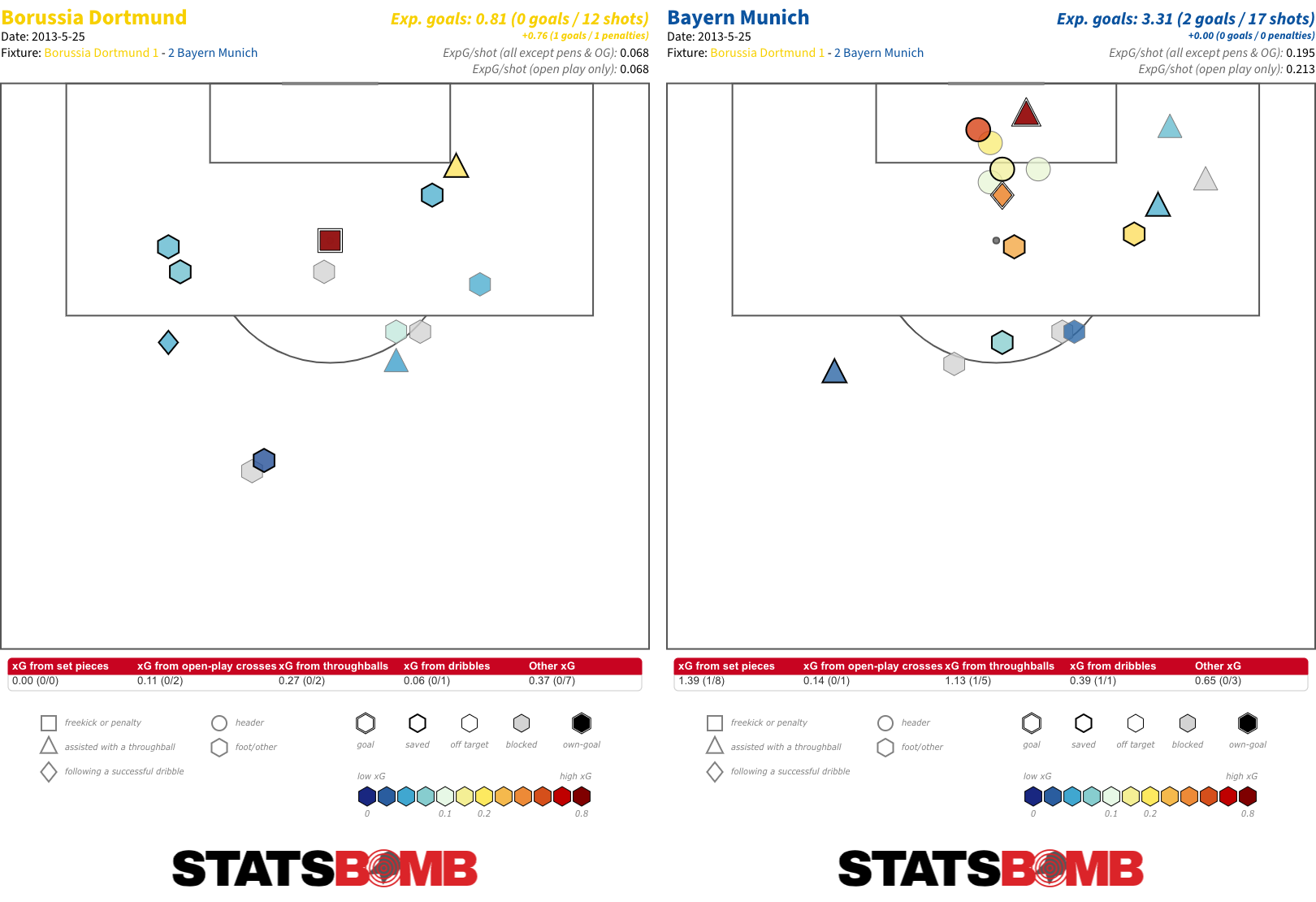

This Bayern side were a real force from set-pieces. Two of the goals in their semi-final rout of Barcelona had come from them, and they also created numerous chances from corners in the final. Seven shots from eight corners and pretty much an entire expected goal.

There wasn’t all that much sign of some of the more advanced routines we see these days, although a neat early free-kick scheme saw Thomas Müller drop off to receive a central pass and lay wide for a cross headed on goal by Mario Mandzukic.

The same player was unable to adjust his body sufficiently to successfully convert a near-post flick from a right-wing corner. But in Mandzukic, Müller and Javi Martínez, Bayern had three players very much capable of winning individual duels to get on the end of deliveries.

------------------------------

We hope you’ve enjoyed this series. Alongside our release of the Arsenal Invincibles data earlier this week, we also made our data from each of the last 20 Champions League finals freely available. If you fancy digging into some of the competition’s recent history, all the details for accessing the data can be found here.

And a complete primer (in English and Espanol) on how to work with the data via StatsBombR is here.