Barcelona and Real Madrid dominated European football throughout most of the 2010s by surrounding their historic stars—Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo—with defenders and central midfielders who were outstanding playmakers: Gerard Piqué, Sergio Ramos, Marcelo, Dani Alves, Sergio Busquets, Xavi, Toni Kroos, Andrés Iniesta, Luka Modrić. Inspired by these teams and players, elite European football demanded defensive players to do more and more with the ball. Sweeper keepers and attacking fullbacks stopped being just a curiosity of South American football while deep midfield playmakers replaced the number ten role.

As the decade moved on, however, football developed a response to this era of possession football in the form of increasingly aggressive and complex pressing systems, from the positional pressing systems of Pep Guardiola or Thomas Tuchel to the zonal pressing schools of Jürgen Klopp or the Red Bull clubs. A rising tide of teams want to dominate European football not so much by what they do on the ball, but how intense and organized they behave off it. Pressing has been a key element in allowing Manchester City and Liverpool to rack up 90+ points in the Premier League, and it's a commonality shared by three of last season’s Champions League semifinalists, Liverpool, Tottenham, and Ajax. In this new era of pressing, modern midfielders and forwards need different skill sets to defeat opponents. Midfielders cannot be just outstanding passers, but more complete ball movers who are able to dribble past opponents from deeper midfield zones. Forwards must make longer runs to beat the higher defensive lines, so speed and dribbles in open spaces are once again considered as relevant as close control and dribbling in tight spaces. And forwards, now more than ever, must be the first line of defense. Real Madrid and Barcelona forwards seem to be lagging behind in several of these key skills, so we decided to dig into the data to find more.

Defense and Pressing

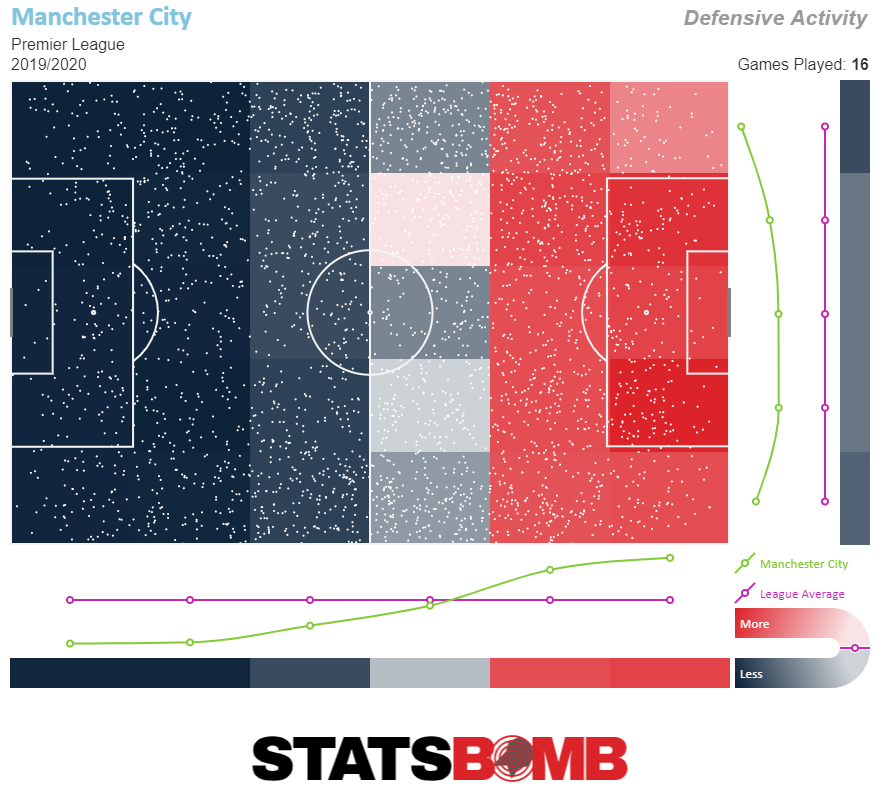

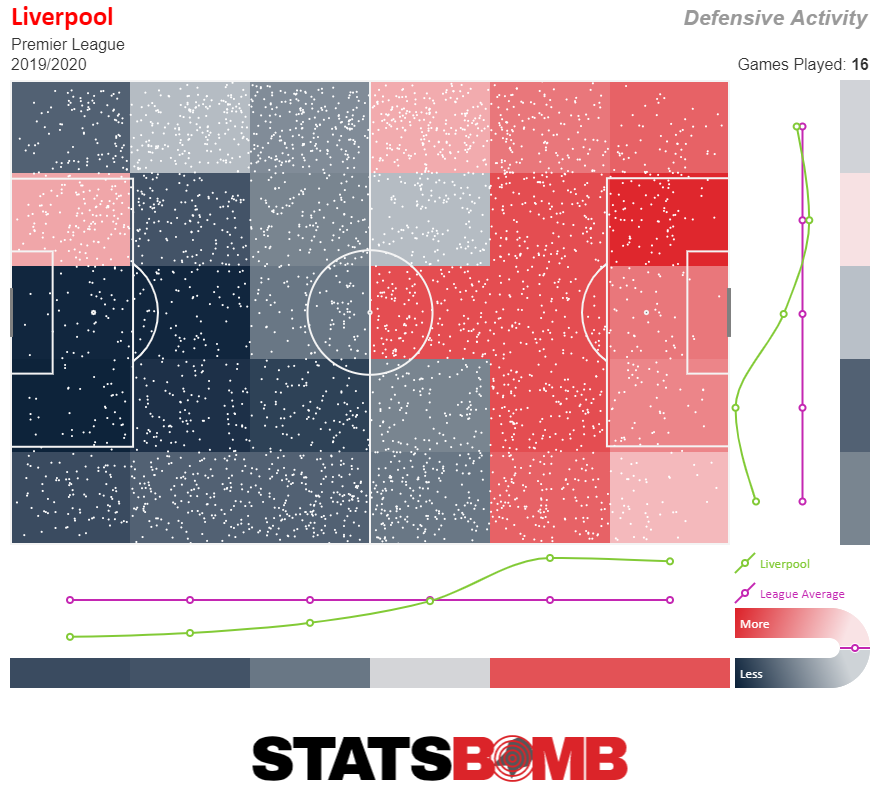

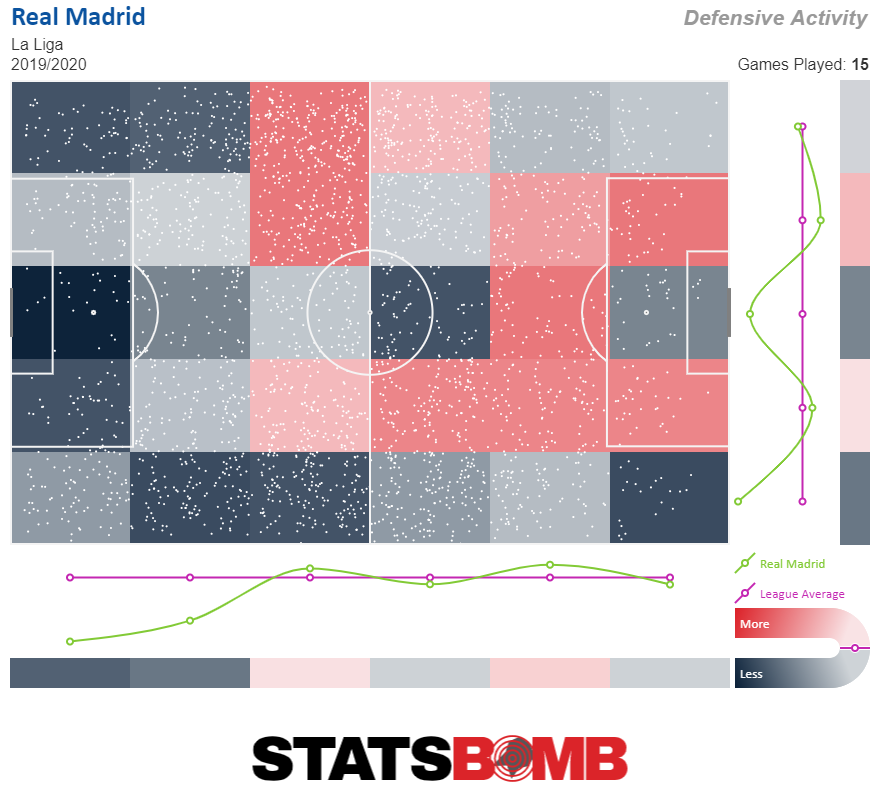

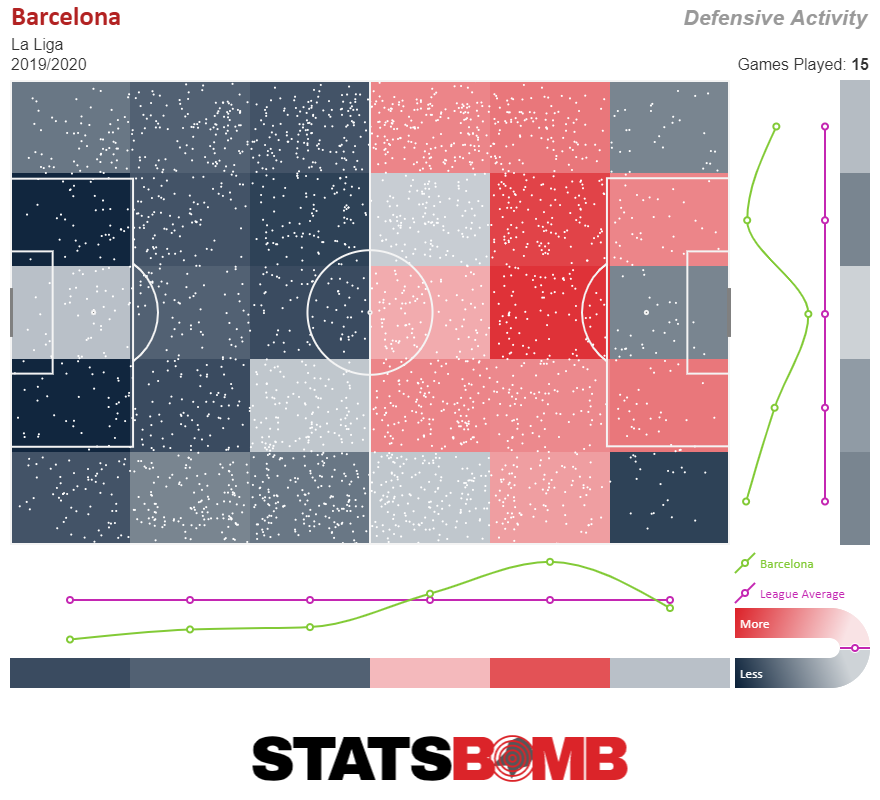

Let’s begin by using the 2019–20 season data to compare the defensive activity of Real Madrid and Barça to two of the most mature, consistent, and high-profile pressing systems in European football: Manchester City and Liverpool. Counting only the players with more than 600 league minutes under their belt, we see the midfielders in all four teams do similar amounts of pressing work: a midfielder at City and Liverpool averages 17 and 19 pressure events per game, respectively, while a midfielder at Real Madrid and Barça averages 18 and 15 pressures per game. The big difference between the defenses of the English and Spanish giants pops out when looking at the pressure data of their forwards. In both English clubs, the forwards lead the way of the press, averaging slightly more pressure events than their midfielders. A forward at City and Liverpool averages 18 and 20 pressures per game, respectively, almost twice the rates of his counterparts at Real Madrid and Barcelona, who average 9 and 11 pressures. Such a difference in the defensive work rate of the forwards is reflected in the collective pressing effort. While Liverpool and City cover the entire final third with a blanket of above-average pressure. . .

. . . Real Madrid and Barça exhibit a patchier defensive activity coverage, leaving more openings for the opposition to progress through the midfield areas.

. . . Real Madrid and Barça exhibit a patchier defensive activity coverage, leaving more openings for the opposition to progress through the midfield areas.

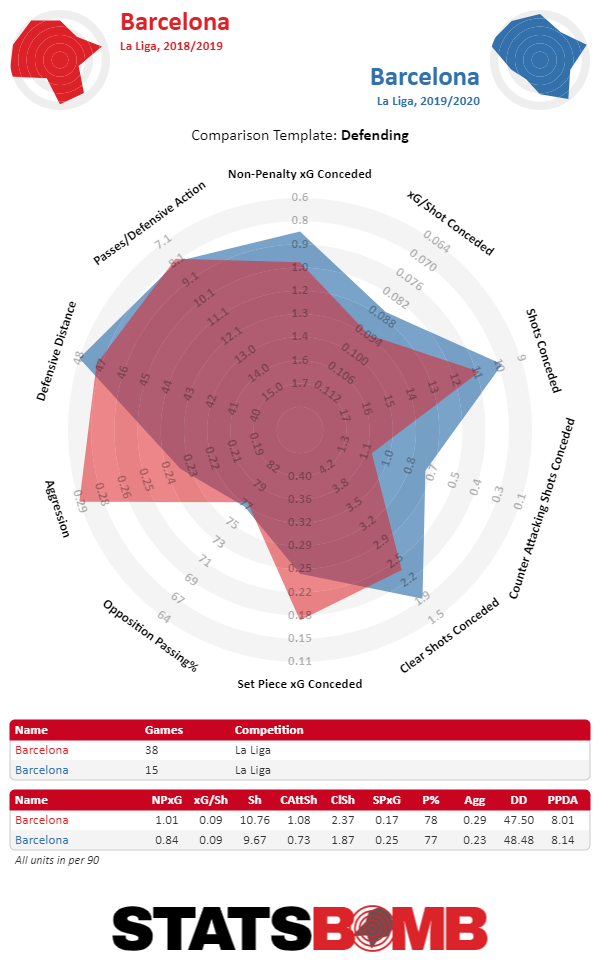

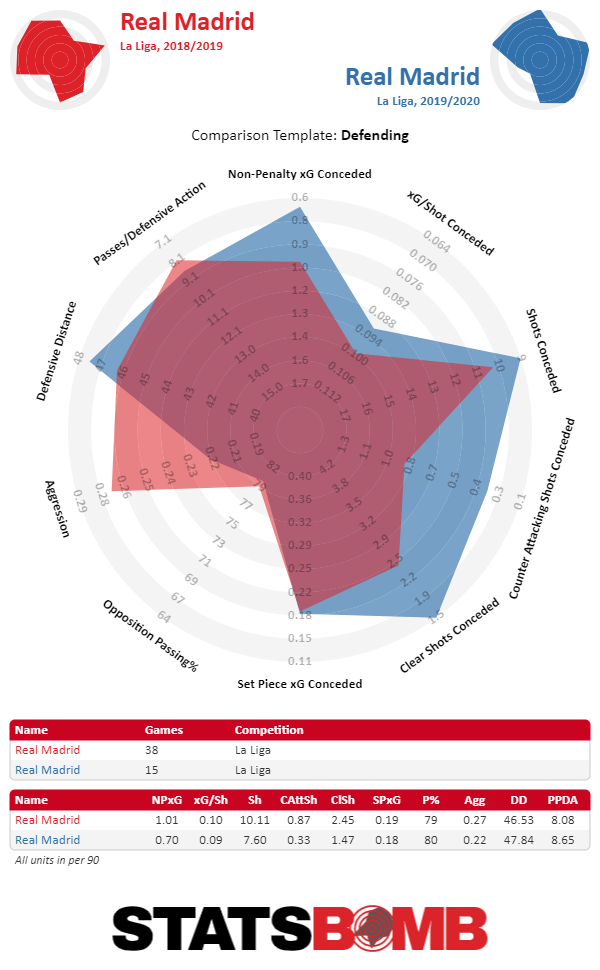

Since midfielders at the Spanish giants must compensate for the pressing work their forwards don’t do, they are forced to push up higher and higher into opposition territory to harass their rivals, leaving bigger gaps behind their backs that can be exploited. A recent example is evident in last weekend’s game between Real Sociedad and Barça. Busquets — still the most active presser in his squad despite being 31 years old — constantly moved right behind Messi and Luis Suárez to pester his opponents during the buildup. Meanwhile, also-31-year-old Ivan Rakitić often drifted wide to the right wing to press the opposition left-back to compensate for the defensive work Messi doesn’t do. Both defensive actions left big gaps behind the veteran midfielders, and neither has the legs to recover on time when overpassed by the opposition. And with Real Sociedad having a skillful midfield trio of Ander Guevara, Mikel Merino, and Martin Ødegaard, they beat the Barça press often, allowing their forward trio of Alexander Isak, Mikel Oyárzabal, and Cristian Portu to thrive in the spaces behind the Blaugrana pressing line. Real Sociedad outshot their rivals by 19 shots to 9. Barcelona managed to draw this game because Gerard Piqué put forth a titanic performance defending his own box, while Antoine Griezmann, Suárez and Messi packed a bigger goal-scoring punch than their opponents and took better advantage of their fewer chances. Moving over to Madrid, Los Blancos have avoided these defensive issues through (a) a less aggressive defensive block and (b) the excellent defensive efforts of Fede Valverde — the team’s most active presser — and Casemiro. Both midfielders have the speed burst that Barcelona’s veteran midfielders lack, so even if they are bypassed or make a mistake when marking opponents, they can recover more easily. This year, both Real Madrid and Barça appear to have acknowledged and adapted to the defensive deficits of their forward lines. As the defensive radars below show, both teams have actually improved on last season’s open play expected goals conceded by using less aggressive defensive behaviors, as measured by StatsBomb’s aggression metric. Both teams are now more selective about when they send their midfielders up to press.

Since midfielders at the Spanish giants must compensate for the pressing work their forwards don’t do, they are forced to push up higher and higher into opposition territory to harass their rivals, leaving bigger gaps behind their backs that can be exploited. A recent example is evident in last weekend’s game between Real Sociedad and Barça. Busquets — still the most active presser in his squad despite being 31 years old — constantly moved right behind Messi and Luis Suárez to pester his opponents during the buildup. Meanwhile, also-31-year-old Ivan Rakitić often drifted wide to the right wing to press the opposition left-back to compensate for the defensive work Messi doesn’t do. Both defensive actions left big gaps behind the veteran midfielders, and neither has the legs to recover on time when overpassed by the opposition. And with Real Sociedad having a skillful midfield trio of Ander Guevara, Mikel Merino, and Martin Ødegaard, they beat the Barça press often, allowing their forward trio of Alexander Isak, Mikel Oyárzabal, and Cristian Portu to thrive in the spaces behind the Blaugrana pressing line. Real Sociedad outshot their rivals by 19 shots to 9. Barcelona managed to draw this game because Gerard Piqué put forth a titanic performance defending his own box, while Antoine Griezmann, Suárez and Messi packed a bigger goal-scoring punch than their opponents and took better advantage of their fewer chances. Moving over to Madrid, Los Blancos have avoided these defensive issues through (a) a less aggressive defensive block and (b) the excellent defensive efforts of Fede Valverde — the team’s most active presser — and Casemiro. Both midfielders have the speed burst that Barcelona’s veteran midfielders lack, so even if they are bypassed or make a mistake when marking opponents, they can recover more easily. This year, both Real Madrid and Barça appear to have acknowledged and adapted to the defensive deficits of their forward lines. As the defensive radars below show, both teams have actually improved on last season’s open play expected goals conceded by using less aggressive defensive behaviors, as measured by StatsBomb’s aggression metric. Both teams are now more selective about when they send their midfielders up to press.

Given the improvement in their defensive underlying numbers, why are we so hung up on their pressing numbers? Pressing high or defending deep, isn’t that just a stylistic choice? Up to this point in the season, Real Madrid has conceded fewer goals and expected goals than Liverpool and Manchester City. If the less aggressive defense works for them, is there really a problem with forwards not doing defensive work? Funnily enough, the problems of the less aggressive approach used by Real Madrid and Barça might be reflected in the attack rather than defense. Teams that recover the ball deeper into their own territory need faster, trickier, and more dynamic forwards who can threaten the opposition goal from longer distances. These players must make fast 30-, 40-, 50-meter runs and still have the lungs and brains to maneuver into good shooting positions and finish clinically. In their prime, Messi, Suárez, Karim Benzema, and Gareth Bale were all part of historic counterattacking trios that destroyed high-profile opponents through a devastating mix of speed and technical precision. If you’re a fan of FC Bayern, you probably remember what I’m talking about (sorry, Bayern fans). Half a decade after those events, none of these forwards retain such explosiveness in their veteran legs. Messi can still single-handedly dribble past defensive systems from time to time, but these moments are becoming rarer and rarer.

Given the improvement in their defensive underlying numbers, why are we so hung up on their pressing numbers? Pressing high or defending deep, isn’t that just a stylistic choice? Up to this point in the season, Real Madrid has conceded fewer goals and expected goals than Liverpool and Manchester City. If the less aggressive defense works for them, is there really a problem with forwards not doing defensive work? Funnily enough, the problems of the less aggressive approach used by Real Madrid and Barça might be reflected in the attack rather than defense. Teams that recover the ball deeper into their own territory need faster, trickier, and more dynamic forwards who can threaten the opposition goal from longer distances. These players must make fast 30-, 40-, 50-meter runs and still have the lungs and brains to maneuver into good shooting positions and finish clinically. In their prime, Messi, Suárez, Karim Benzema, and Gareth Bale were all part of historic counterattacking trios that destroyed high-profile opponents through a devastating mix of speed and technical precision. If you’re a fan of FC Bayern, you probably remember what I’m talking about (sorry, Bayern fans). Half a decade after those events, none of these forwards retain such explosiveness in their veteran legs. Messi can still single-handedly dribble past defensive systems from time to time, but these moments are becoming rarer and rarer.

Barça’s Attack and the Deficit of Explosiveness

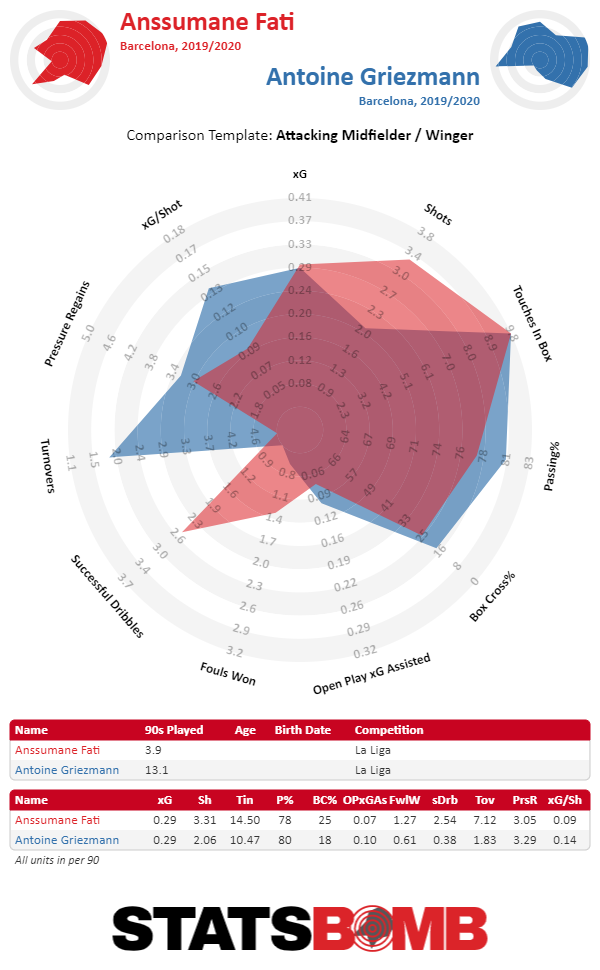

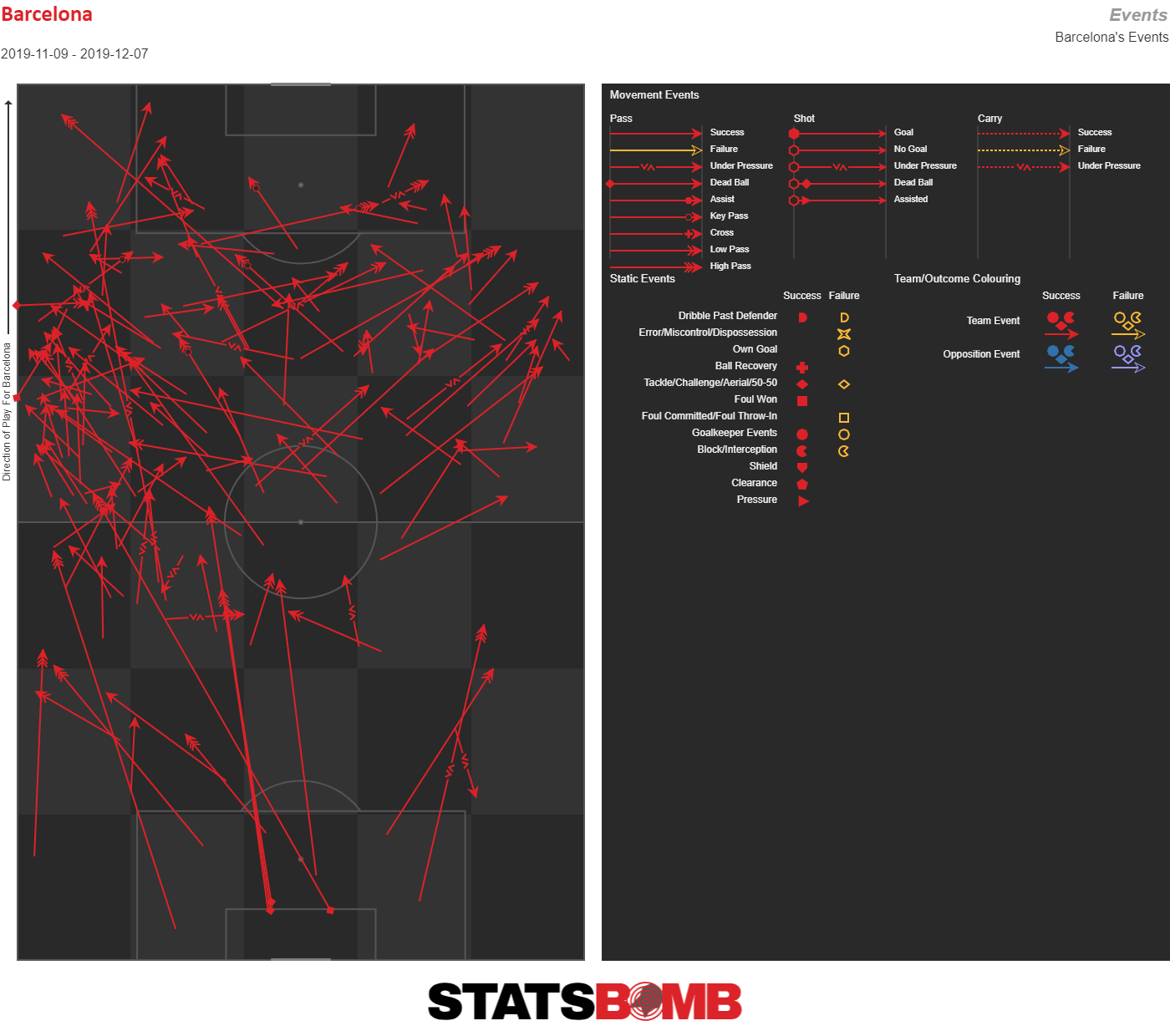

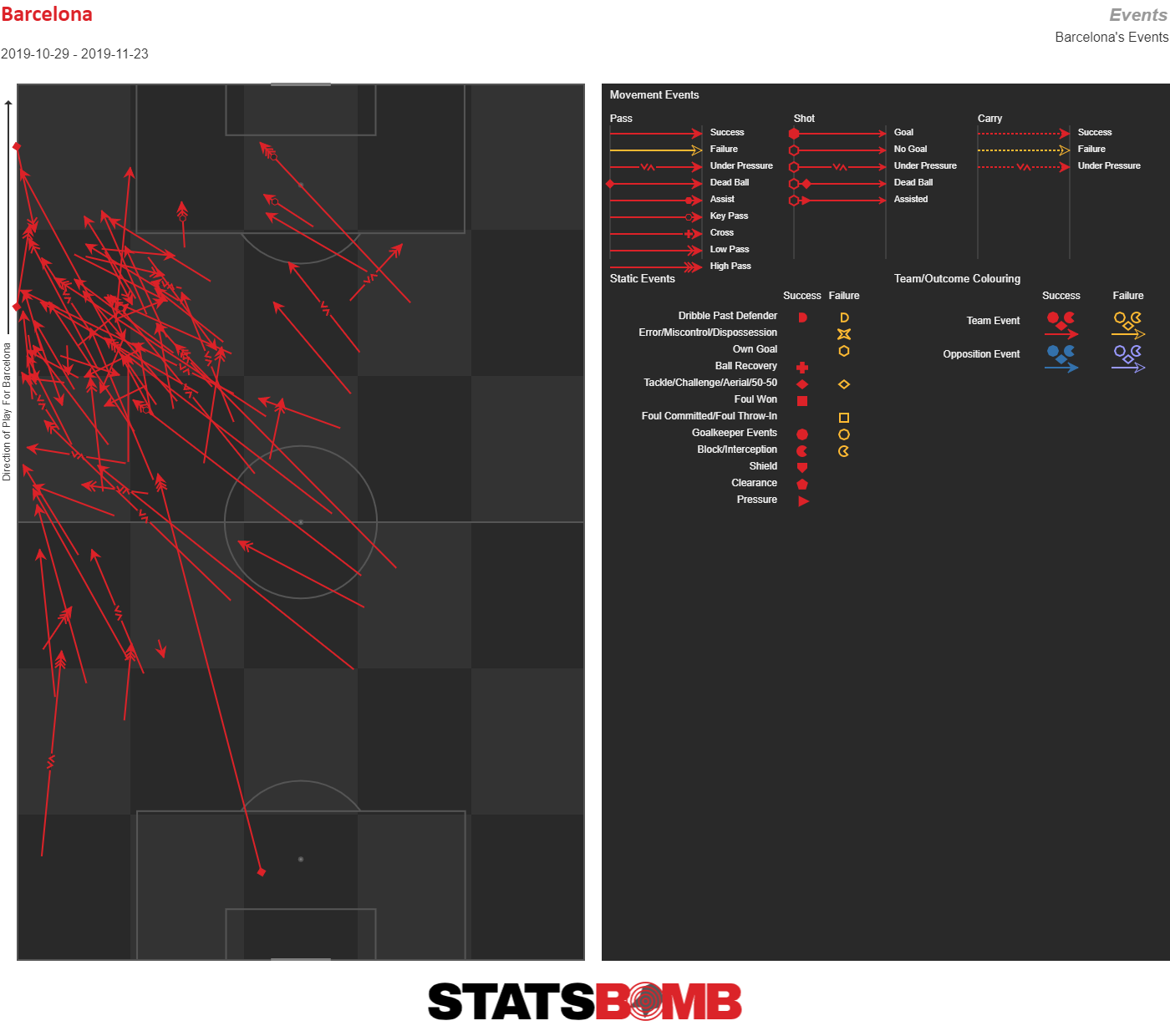

Barça tried to compensate for an aging Messi and the departure of Neymar by signing Ousmane Dembelé, but he has struggled to live up to his potential over his two injury-plagued years at the club. This past summer, instead of using the transfer war chest to sign another speedy trickster and goal-scorer who could play off Messi, they went for Griezmann, a striker known for his technical precision, finishing, and game intelligence rather than his speed and dribbling. And to boot, his ideal role and zones of influence are similar to Messi’s. This leads to a forward trio of Messi, Suárez, and Griezmann who accumulate plenty of goal-scoring punch, but not enough explosiveness to threaten defenses. It should thus come as no surprise that the Blaugrana team received a breath of fresh air with the surprise appearance of 17-year-old Anssumane “Ansu” Fati, the newest hot prospect from La Masía who is now the youngest player ever to score in a Champions League game. He has barely played 327 minutes in La Liga, but despite the small sample size at hand, it’s not outlandish to argue that his speed and dribbling make him a better fit for Barcelona’s left winger role than Griezmann.  As seen in the passing visualization below, Griezmann’s preferred way of playing the left winger role is . . . to not play as a left winger. He’s not a dribbler, so he compensates by smartly moving across the pitch, slipping into the gaps left by the opposition defense. This is how he can end up stepping on Messi's areas of influence and becoming redundant.

As seen in the passing visualization below, Griezmann’s preferred way of playing the left winger role is . . . to not play as a left winger. He’s not a dribbler, so he compensates by smartly moving across the pitch, slipping into the gaps left by the opposition defense. This is how he can end up stepping on Messi's areas of influence and becoming redundant.  Fati’s dribbling ability, on the other hand, allows him to stick to the left wing and avoid interfering with Messi and Suárez while still managing to get into the box and produce shots.

Fati’s dribbling ability, on the other hand, allows him to stick to the left wing and avoid interfering with Messi and Suárez while still managing to get into the box and produce shots.

Real Madrid’s Attack and Their Goal-Scoring Deficit

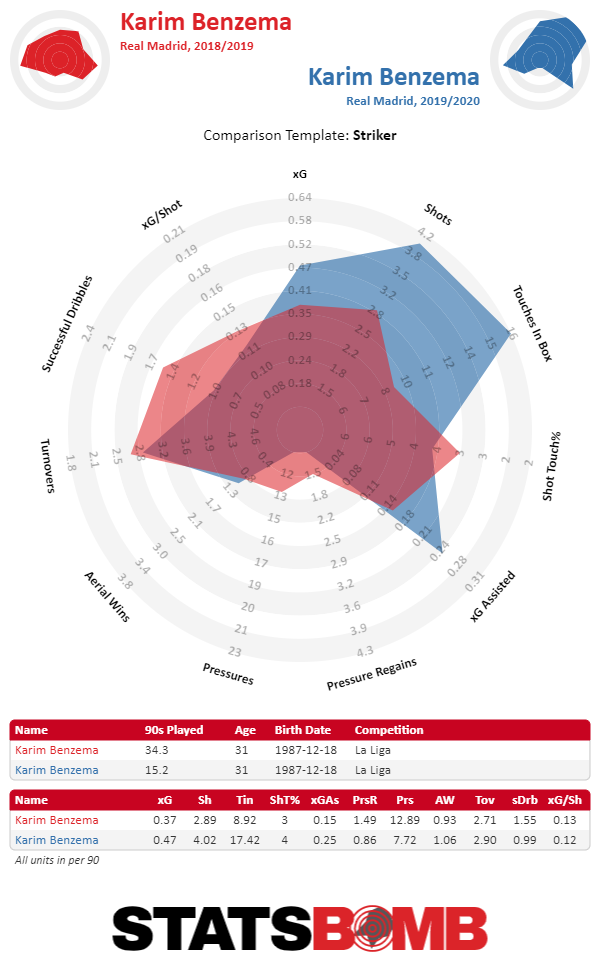

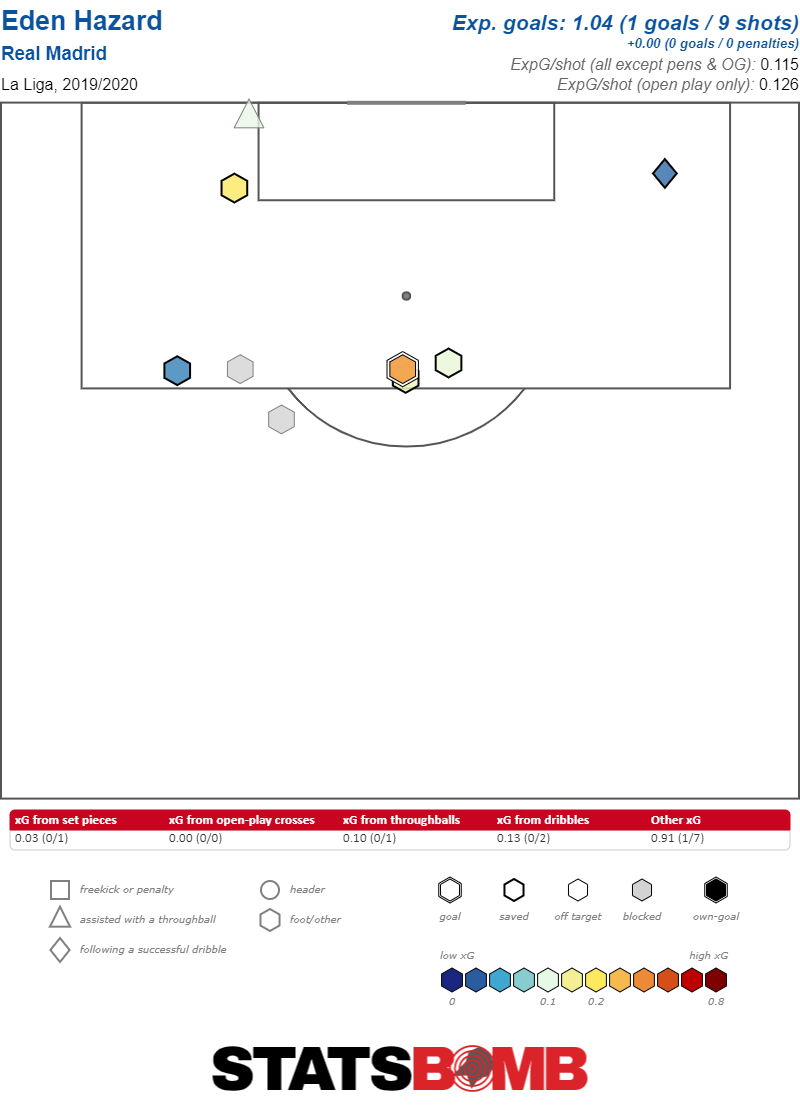

Real Madrid not only ignored the decreasing speed and dribbling skill of their forward line for a couple of years, but in the summer of 2018, they also ignored a gargantuan goal-scoring deficit by letting go of Ronaldo without replacing him with another world-class goal scorer. This past summer they tried to make amends in these areas by signing top striker prospect Luka Jović and a superstar dribbler in Eden Hazard, but this still doesn’t solve all their attacking problems. Zidane wants to build the team around his best dribbler — Hazard — and his best striker — a Benzema who is undergoing a late renaissance — but often uses a 4-3-3 setup that relegates Jović to a substitute role, since the Serbian doesn’t have the speed to act as a goal-scoring winger beside Benzema. With Zidane barely using the forward who should be his second-best goal-scorer, an overworked Benzema must carry the team’s goal production. 45% of Real Madrid’s expected goal output (and 52% of their actual goals) in the league has been shot or assisted by Benzema.  With a slow and injury-ridden start to the 19/20 season, Hazard has suffered his lowest goal-assist productivity since his 2015–16 annus horribilis, with a meager 0.27 non-penalty expected goals + expected assists per 90.

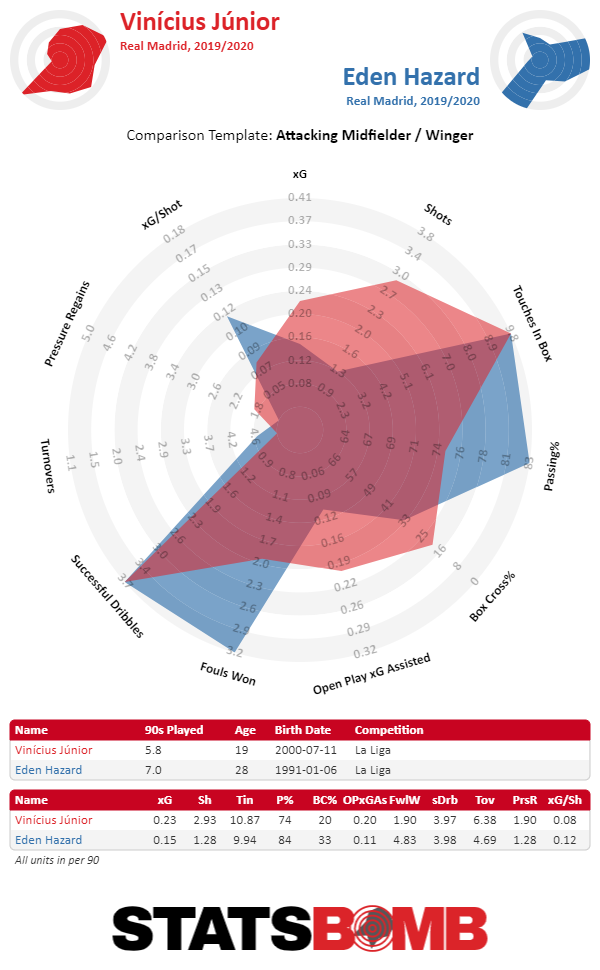

With a slow and injury-ridden start to the 19/20 season, Hazard has suffered his lowest goal-assist productivity since his 2015–16 annus horribilis, with a meager 0.27 non-penalty expected goals + expected assists per 90.  Bale is doing better, with a rate of 0.47 non-penalty xG + xG assisted per 90, but his performance has once again been affected by injuries and the mistrust of a fanbase who questions his commitment to the team. With every passing year, the 30-year-old Bale seems slower and less able to get into ideal shooting positions. Given the lackluster performance of the senior forwards, Real Madrid’s hopes have shifted to their U-20 players: 19-year-old Vinícius Jr. and 18-year-old Rodrygo Goes. After his breakout 18–19 season, Vinícius continues to be one of La Liga’s elite dribblers, but he must master the art of goalscoring. While Hazard is too reluctant to shoot, Vinícius is too eager, which often leads him to shoot from subpar locations. His open play shot quality of 0.08 xG per shot ranks below league average, by far the lowest among Real Madrid forwards.

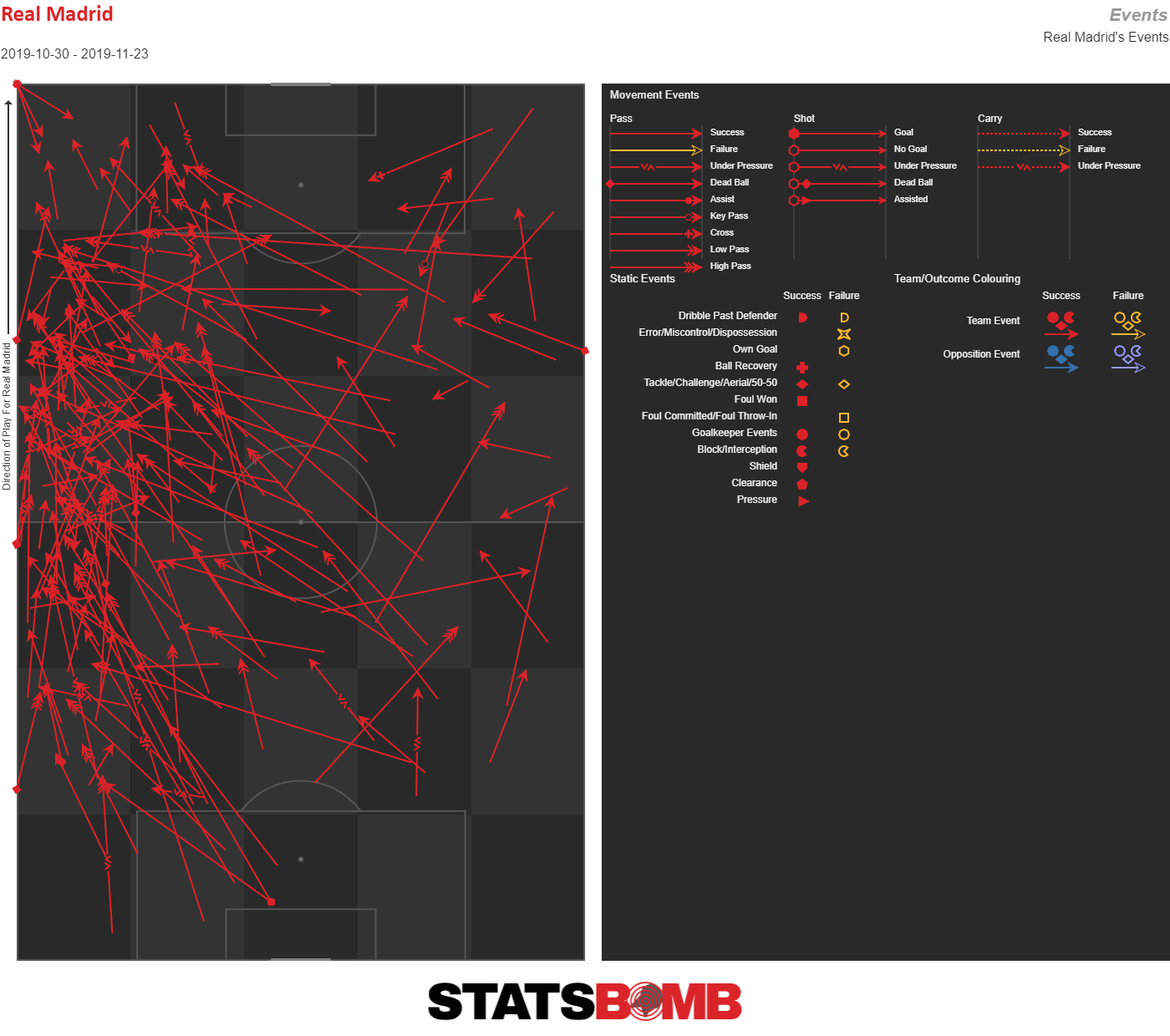

Bale is doing better, with a rate of 0.47 non-penalty xG + xG assisted per 90, but his performance has once again been affected by injuries and the mistrust of a fanbase who questions his commitment to the team. With every passing year, the 30-year-old Bale seems slower and less able to get into ideal shooting positions. Given the lackluster performance of the senior forwards, Real Madrid’s hopes have shifted to their U-20 players: 19-year-old Vinícius Jr. and 18-year-old Rodrygo Goes. After his breakout 18–19 season, Vinícius continues to be one of La Liga’s elite dribblers, but he must master the art of goalscoring. While Hazard is too reluctant to shoot, Vinícius is too eager, which often leads him to shoot from subpar locations. His open play shot quality of 0.08 xG per shot ranks below league average, by far the lowest among Real Madrid forwards.  That being said, Vinícius does offer things that none of his senior teammates do. As the passing graphic below shows, Hazard will often receive the ball in his own half, aiming to dribble or combine with his teammates to help progress through midfield zones.

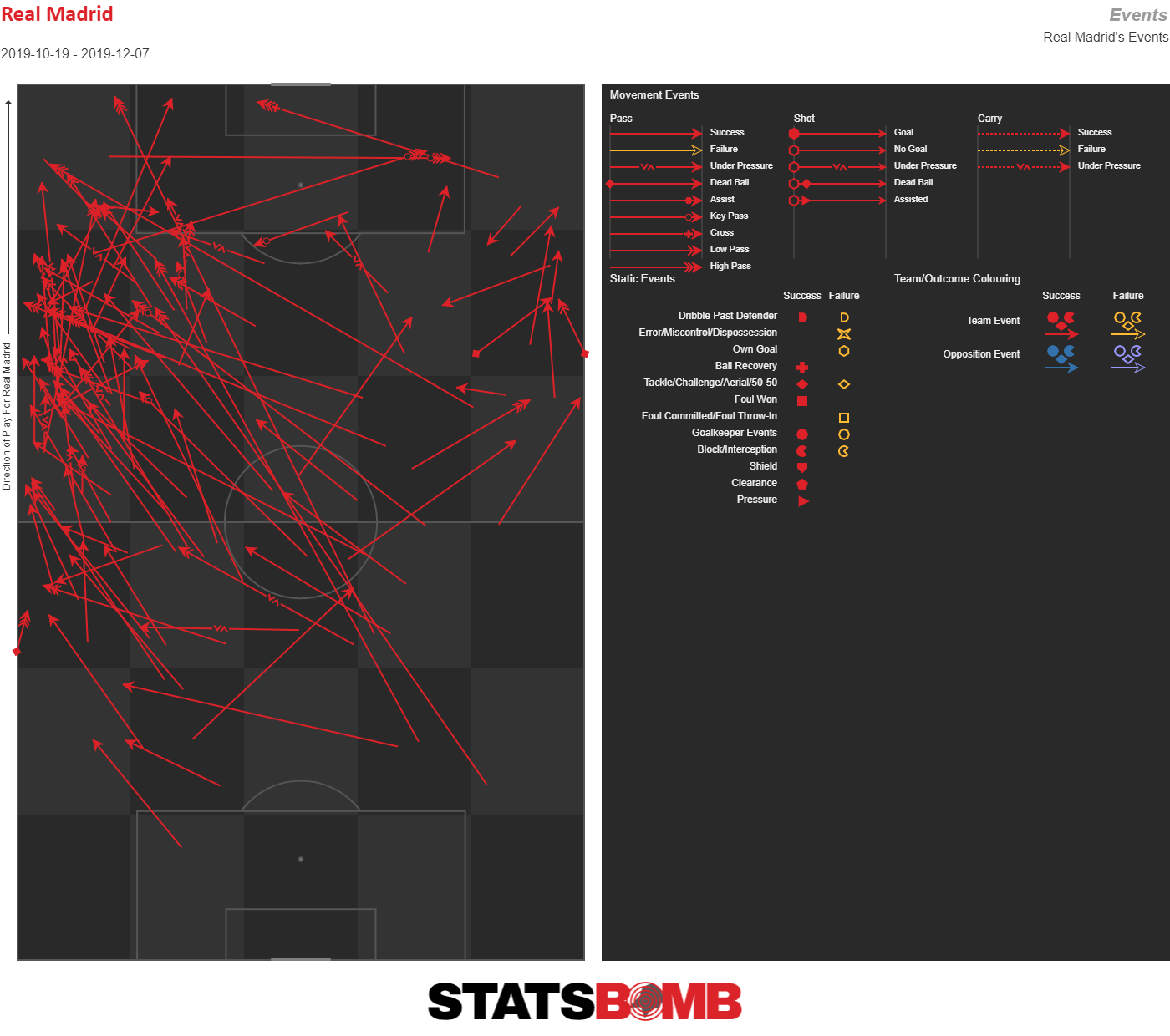

That being said, Vinícius does offer things that none of his senior teammates do. As the passing graphic below shows, Hazard will often receive the ball in his own half, aiming to dribble or combine with his teammates to help progress through midfield zones.  Vinícius performs some of these progressive runs and passes, too, but his efforts are more concentrated in the opposition half. Not only does he want to run at defenders, but he’s often willing to run behind them too. Bale, Benzema, and Hazard don’t make these runs into space frequently.

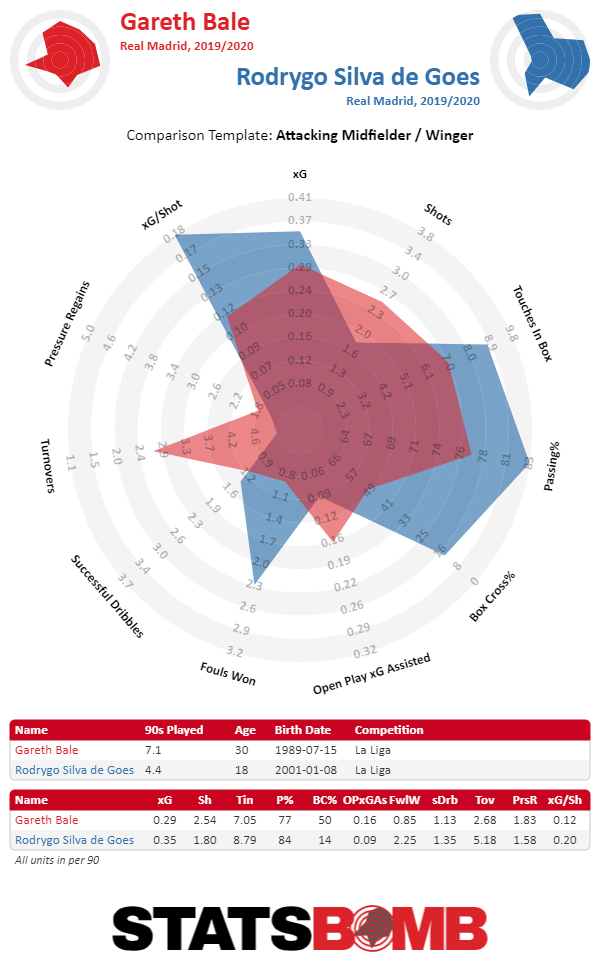

Vinícius performs some of these progressive runs and passes, too, but his efforts are more concentrated in the opposition half. Not only does he want to run at defenders, but he’s often willing to run behind them too. Bale, Benzema, and Hazard don’t make these runs into space frequently.  On the right wing, Rodrygo is competing against Bale for the starting role in the lineup. He’s not an elite dribbler like Vinícius, but he tries to compensate by being more cerebral and precise. Rodrygo does not shoot often but is more careful about his shot locations, averaging the highest xG per shot this season among Real Madrid forwards. While Bale seems increasingly comfortable staying on the wing and whipping a cross into the box, Rodrygo seems more willing to attack the box, which is ultimately reflected in his higher rate of touches in the box and xG.

On the right wing, Rodrygo is competing against Bale for the starting role in the lineup. He’s not an elite dribbler like Vinícius, but he tries to compensate by being more cerebral and precise. Rodrygo does not shoot often but is more careful about his shot locations, averaging the highest xG per shot this season among Real Madrid forwards. While Bale seems increasingly comfortable staying on the wing and whipping a cross into the box, Rodrygo seems more willing to attack the box, which is ultimately reflected in his higher rate of touches in the box and xG.  A great example of Rodrygo’s precision and composure in finishing is his debut goal against Osasuna, where he easily controlled a 40-meter pass from Casemiro, ran into the box, and waited for the correct moment to cut inside with his right foot and score. The irony in this story of Vinícius and Rodrygo is that one youngster seems to have what the other lacks, and vice versa.

A great example of Rodrygo’s precision and composure in finishing is his debut goal against Osasuna, where he easily controlled a 40-meter pass from Casemiro, ran into the box, and waited for the correct moment to cut inside with his right foot and score. The irony in this story of Vinícius and Rodrygo is that one youngster seems to have what the other lacks, and vice versa.

Conclusions

Real Madrid and Barcelona have incredibly talented squads, but their players don’t necessarily complement each other, which leads to many of the tactical problems mentioned. This happens when clubs buy talent for the sake of buying talent, without a specific philosophy or game plan in mind. That represents the big difference over the last three years between the two Spanish giants and the two English giants: the latter first defined — through their management and coaching teams — an idea of how they wanted to play, and then bought players who fit their needs and the rest of the squad. By building these strong collective structures, Liverpool and Manchester City created teams who could rack up 90+ points in their domestic league or win the Champions League without needing a Messi or a Ronaldo. I’m willing to bet that the forwards in Real Madrid and Barcelona who are not doing much defensive work now would significantly increase their defensive work rates if they played at Manchester City or Liverpool instead. Real Madrid and Barça can keep buying players as much as they want, but they will keep running into problems of squad coherence until they learn to first settle on an identity, and then buy the talent that fits. At least Real Madrid can say they’ve never followed that approach, but Barça have long prided themselves in being a philosophy club, yet their current first-team squad building doesn’t seem to follow a coherent game plan.