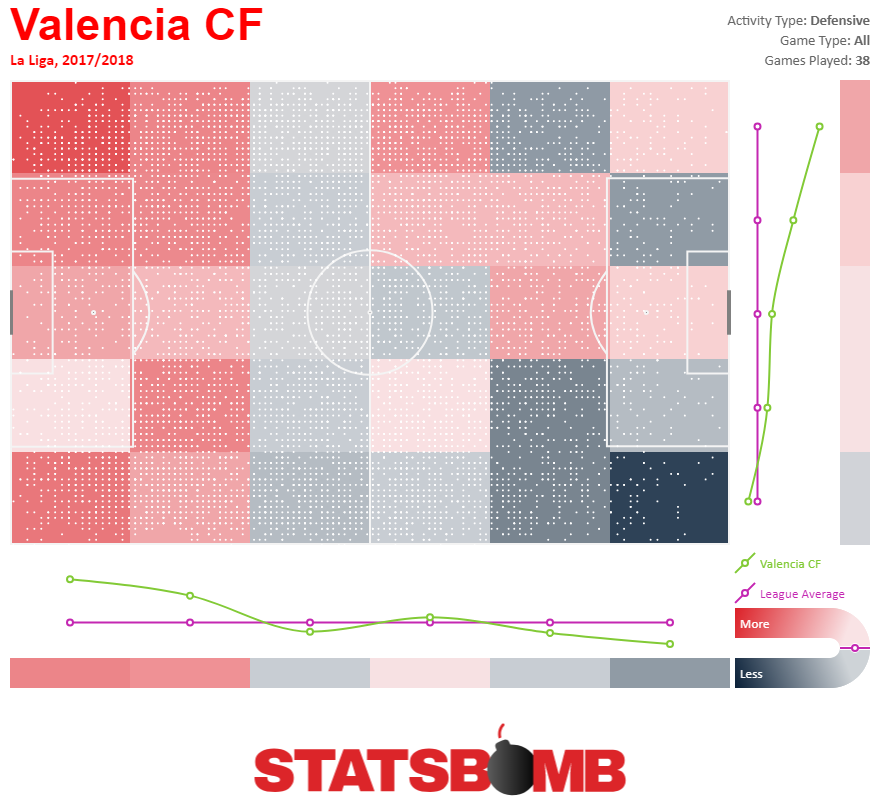

After a couple of tumultuous campaigns filled with coaching changes and general unrest, Valencia jumped up from 12th to finish fourth in La Liga last season, 12 points clear of Villarreal in fifth, just three off Real Madrid in third, and with an xG difference that was also the fourth-best in the division. While the club did good work in offloading older fringe players and bolstering the squad with some good value permanent and loan deals, the best signing of all was the appointment of Marcelino to their bench. A demanding, detail-obsessed coach with a clearly defined approach, he brought purpose to a team who had previously lacked direction. Marcelino’s teams always seek to maintain a compact shape to control space out of possession and once the ball is won, move forward swiftly and directly to create shooting opportunities before the opposition can get set. “I want us to be organised, with everyone participating equally, regardless of whether we are defending or attacking,” he said in 2015, while in charge of Villarreal. “If we can complete a move in five successive passes along the ground, we won’t do it in 20.” A glance at Valencia’s defensive activity map for last season demonstrates the degree to which their defensive routine was based around quickly regaining their shape and dropping into a deep block. There are some patches of higher pressing but the extreme commitment to applying serious pressure on the edge of their defensive third clearly shines through.  It was an approach that worked very well for them. While they allowed 12.84 shots per match, seventh most in La Liga, only Atletico Madrid conceded shots of a lower average xG value than those of 0.08xG/shot given up by Valencia. That added up to the third best defence in the division. Valencia also ranked pretty well going forward, with the fifth-best xG and the fourth-best actual scoring record. If their defensive scheme was based around constricting shot quality then their attacking approach sought to generate good quality opportunities by quickly converting turnovers of possession into efforts on goal. When the ball was won, a wide player would move infield or a striker, usually Rodrigo, would drop off to find space to receive between the lines. While one came for the ball, the others would quickly spread to widen the pitch and create onward options, often criss-crossing as they did so, particularly when Gonzalo Guedes made diagonal movements in from the left flank. The speed with which attacks were constructed and completed is shown by the domination of the team’s shot numbers by the five players most often utilised across the four forward-most positions.

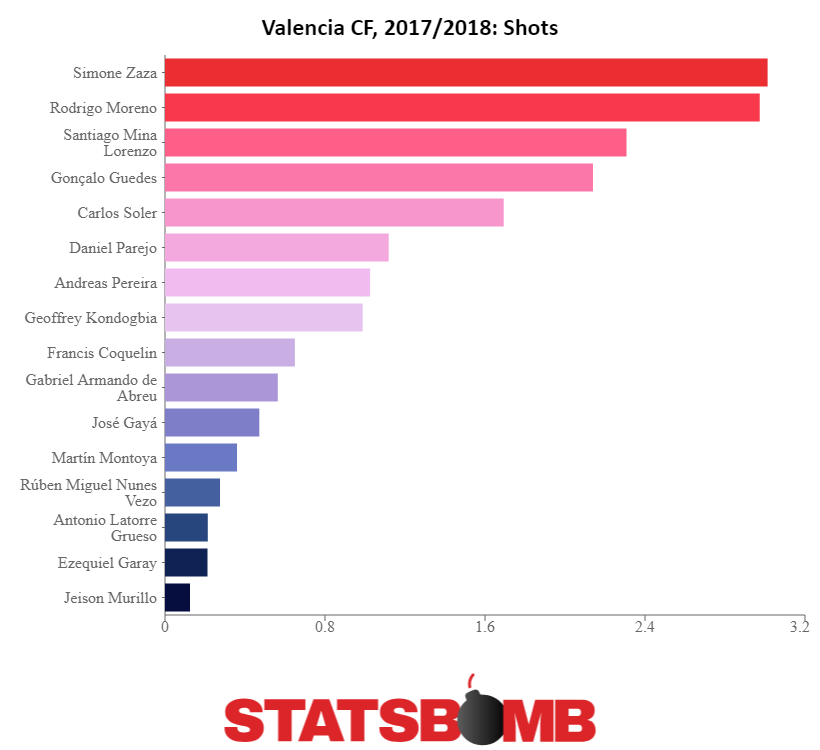

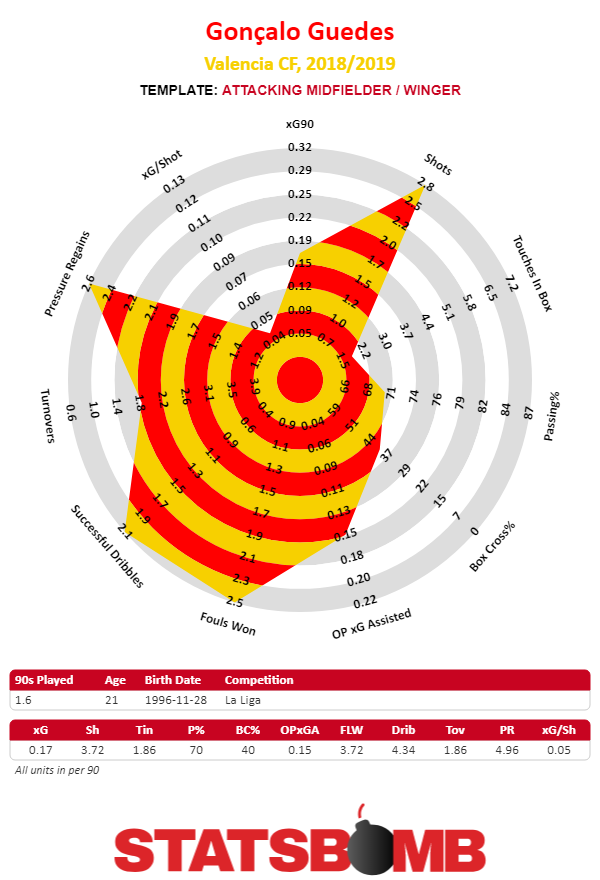

It was an approach that worked very well for them. While they allowed 12.84 shots per match, seventh most in La Liga, only Atletico Madrid conceded shots of a lower average xG value than those of 0.08xG/shot given up by Valencia. That added up to the third best defence in the division. Valencia also ranked pretty well going forward, with the fifth-best xG and the fourth-best actual scoring record. If their defensive scheme was based around constricting shot quality then their attacking approach sought to generate good quality opportunities by quickly converting turnovers of possession into efforts on goal. When the ball was won, a wide player would move infield or a striker, usually Rodrigo, would drop off to find space to receive between the lines. While one came for the ball, the others would quickly spread to widen the pitch and create onward options, often criss-crossing as they did so, particularly when Gonzalo Guedes made diagonal movements in from the left flank. The speed with which attacks were constructed and completed is shown by the domination of the team’s shot numbers by the five players most often utilised across the four forward-most positions.  Strikers Rodrigo, Santi Mina and the since departed Simone Zaza all enjoyed the most productive seasons of their careers to date, but despite some inconsistency - that he himself admits to - it was Guedes who was perhaps the most important element in the Valencia attack. He was the player who led the team in successful dribbles, who most often moved the ball into the box, who produced the most assists and drew the most fouls. At times he was unplayable, most notably in a 4-0 home win over Sevilla in which he notched two goals and an assist. A scoring contribution of five goals and nine assists, 0.50 per 90 minutes, as a 20-21 year-old in his first season in La Liga was a very solid return. It was no surprise that Valencia paid €40 million to Paris Saint-Germain to make his transfer permanent this summer, even if, as El Pais’ rather snarky headline of “Indebted Valencia secure the signing of Guedes, the most expensive in their history” suggested, there are question marks over how the deal was financed. If Guedes can add more goals to everything he contributed last season - which his increased shot count early into the new campaign suggests is possible - Valencia could have a genuine star on their hands.

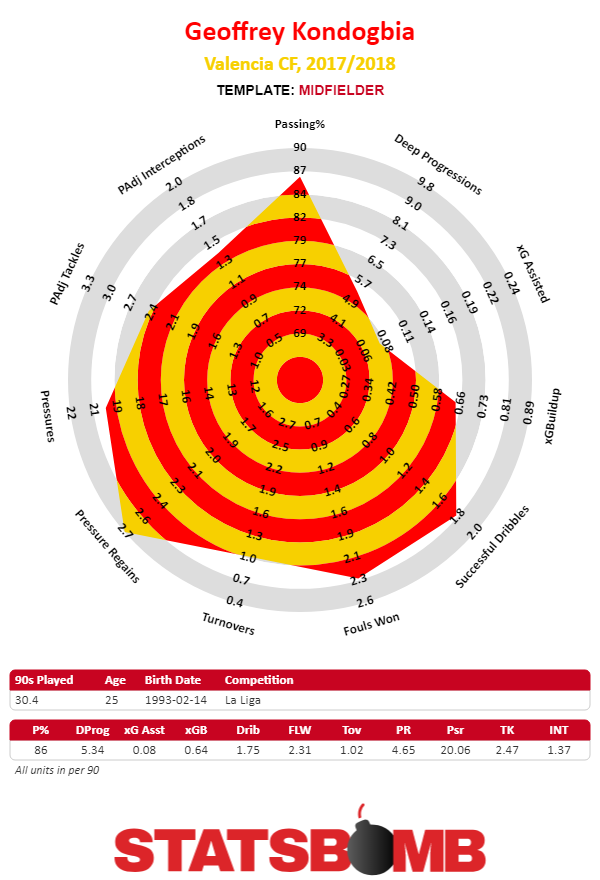

Strikers Rodrigo, Santi Mina and the since departed Simone Zaza all enjoyed the most productive seasons of their careers to date, but despite some inconsistency - that he himself admits to - it was Guedes who was perhaps the most important element in the Valencia attack. He was the player who led the team in successful dribbles, who most often moved the ball into the box, who produced the most assists and drew the most fouls. At times he was unplayable, most notably in a 4-0 home win over Sevilla in which he notched two goals and an assist. A scoring contribution of five goals and nine assists, 0.50 per 90 minutes, as a 20-21 year-old in his first season in La Liga was a very solid return. It was no surprise that Valencia paid €40 million to Paris Saint-Germain to make his transfer permanent this summer, even if, as El Pais’ rather snarky headline of “Indebted Valencia secure the signing of Guedes, the most expensive in their history” suggested, there are question marks over how the deal was financed. If Guedes can add more goals to everything he contributed last season - which his increased shot count early into the new campaign suggests is possible - Valencia could have a genuine star on their hands.  The two players tasked with holding things together in the centre of midfield, putting the first concerted pressure on the ball and orchestrating the initial transition from defence to attack were Daniel Parejo and Geoffrey Kondogbia. They formed a mutually enhancing partnership. Parejo put indirect pressure on the ball and helped progress it forward with the subtlety of his passing, leading the team with a league top-10 9.15 deep progressions per 90 minutes; Kondogbia was more directly involved in breaking up play, used the ball well and advanced it on the dribble. He put together an impressive campaign.

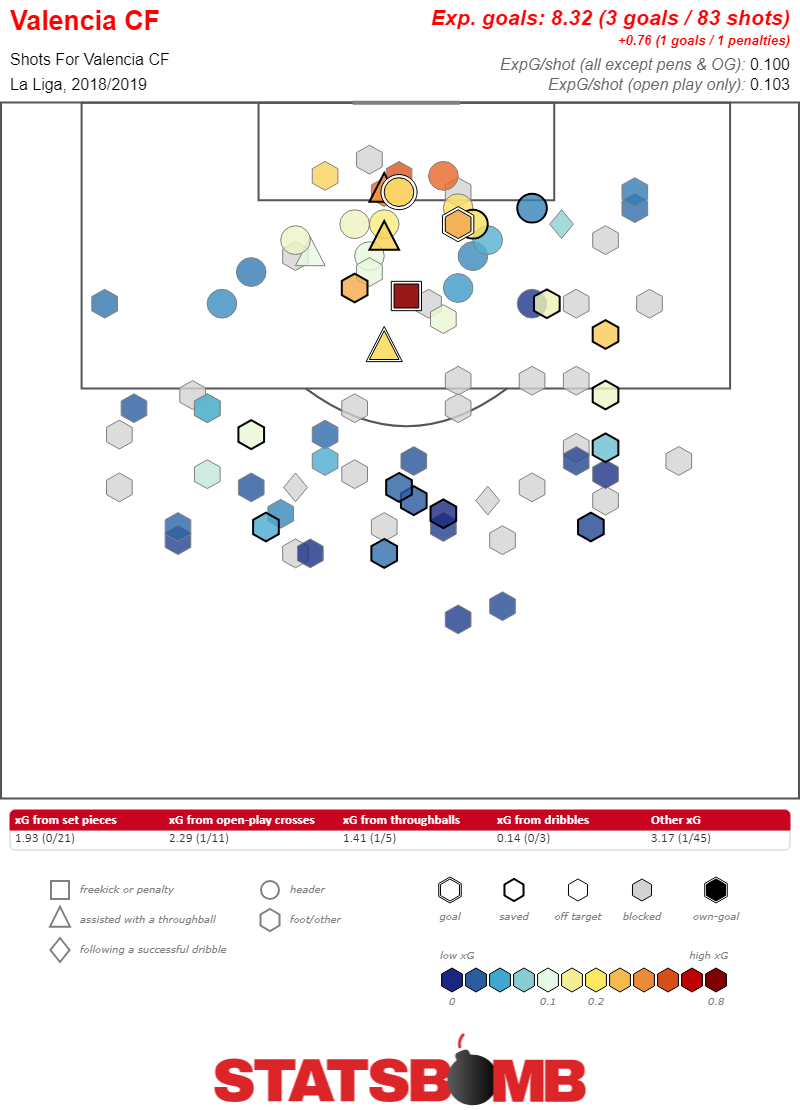

The two players tasked with holding things together in the centre of midfield, putting the first concerted pressure on the ball and orchestrating the initial transition from defence to attack were Daniel Parejo and Geoffrey Kondogbia. They formed a mutually enhancing partnership. Parejo put indirect pressure on the ball and helped progress it forward with the subtlety of his passing, leading the team with a league top-10 9.15 deep progressions per 90 minutes; Kondogbia was more directly involved in breaking up play, used the ball well and advanced it on the dribble. He put together an impressive campaign.  While Valencia were marginally outshot over the course of the season, they were able to create better chances than they conceded and consequently ended up with a clearly positive xG difference. They weren’t elite at either end of the pitch, but it was a highly encouraging campaign that left plenty of room for growth. Things have not, however, gone to plan so far this season, despite some additions to the squad who seem good fits in terms of attributes (the intelligence and application of Daniel Wass) and output (Michy Batshuayi joined on loan from Chelsea on the back of a goal every 120 minutes at Borussia Dortmund in the second half of last season). Coming into their Champions League group stage match against Manchester United at Old Trafford on Tuesday, Valencia have recorded just one win (alongside five draws and a defeat) in seven in La Liga and are in need of a positive result after losing 2-0 at home to Juventus in their group opener. The statistics suggest that they are still a good side. “If we continue like this, results will come,” said assistant coach Ruben Uria in the wake of the team’s draw with Celta Vigo, and he wasn’t wrong. The attack is still functioning as well as it did last season in terms of creating chances. The problem is that they aren’t being finished anywhere near as efficiently.

While Valencia were marginally outshot over the course of the season, they were able to create better chances than they conceded and consequently ended up with a clearly positive xG difference. They weren’t elite at either end of the pitch, but it was a highly encouraging campaign that left plenty of room for growth. Things have not, however, gone to plan so far this season, despite some additions to the squad who seem good fits in terms of attributes (the intelligence and application of Daniel Wass) and output (Michy Batshuayi joined on loan from Chelsea on the back of a goal every 120 minutes at Borussia Dortmund in the second half of last season). Coming into their Champions League group stage match against Manchester United at Old Trafford on Tuesday, Valencia have recorded just one win (alongside five draws and a defeat) in seven in La Liga and are in need of a positive result after losing 2-0 at home to Juventus in their group opener. The statistics suggest that they are still a good side. “If we continue like this, results will come,” said assistant coach Ruben Uria in the wake of the team’s draw with Celta Vigo, and he wasn’t wrong. The attack is still functioning as well as it did last season in terms of creating chances. The problem is that they aren’t being finished anywhere near as efficiently.  There has, though, been a slight regression defensively. As was the case last season, Valencia can be stretched horizontally by teams who get good numbers forward across the width of the pitch - a weakness that was particularly evident in the first half of their loss to Juventus. But they have also generally been a bit looser this time around. They are giving up a similar number of shots but better quality ones, in part because their turnovers of possession are more often leading to efforts on goal. They have also been guilty of a catalogue of defensive errors: clumsily conceded penalties, lapses in concentration, failures to track runners and breakdowns in communication. The integration of a few new players is one plausible explanation for this - new right-back Cristiano Piccini has certainly been at fault for at least a couple of goals - while the fitness problems suffered by Kondogbia, their only clearly destructive presence in midfield, has lessened their ability to limit opposition progress towards their back four. With potential top-four contenders Sevilla making a stronger start to the season, Valencia need to find a solution to their defensive issues and start taking their chances if they are to become the first team outside of Barcelona, Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid to achieve consecutive top-four finishes since they themselves did it three times in a row between 2009-2010 and 2011-12. And that same formula could very well yield success against United.

There has, though, been a slight regression defensively. As was the case last season, Valencia can be stretched horizontally by teams who get good numbers forward across the width of the pitch - a weakness that was particularly evident in the first half of their loss to Juventus. But they have also generally been a bit looser this time around. They are giving up a similar number of shots but better quality ones, in part because their turnovers of possession are more often leading to efforts on goal. They have also been guilty of a catalogue of defensive errors: clumsily conceded penalties, lapses in concentration, failures to track runners and breakdowns in communication. The integration of a few new players is one plausible explanation for this - new right-back Cristiano Piccini has certainly been at fault for at least a couple of goals - while the fitness problems suffered by Kondogbia, their only clearly destructive presence in midfield, has lessened their ability to limit opposition progress towards their back four. With potential top-four contenders Sevilla making a stronger start to the season, Valencia need to find a solution to their defensive issues and start taking their chances if they are to become the first team outside of Barcelona, Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid to achieve consecutive top-four finishes since they themselves did it three times in a row between 2009-2010 and 2011-12. And that same formula could very well yield success against United.

2018

Valencia Look to Regain Last Year's Form Ahead of Manchester United Champions League Clash

By admin

|

October 1, 2018