One of the frustrations in football analytics is the inability to do long term studies. The field is still relatively new, data is often proprietary and the sport simply doesn’t have the wealth of historical statistical record that leagues such as MLB or the NBA do.

Part of why StatsBomb has formulated the Messi Project is to make a small move to redress that balance. By releasing data from Lionel Messi’s entire La Liga career, it will enable amateur analysts to dig right into the numerical representations of one of history’s greatest footballers and track his evolution from teenage tearaway winger to an all-time great goalscorer. It is entirely unprecedented for a data company to offer this kind of opportunity for evaluation and insight and we are proud to lead the way here.

The data will be released in four season batches and will be available for free, for everyone from the resource centre from Tuesday 16th July onwards. Get stuck in as soon as you can. We are very much looking forward to seeing the analyst world’s ability to create and iterate over this dataset and flex their skills.

The first tranche of games released (and available this week) covers his early years between 2004-05 and 2007-08 and we will look at that period here.

Messi arrived in the Barcelona first team as a 17 year old and his first four seasons were all under the tutelage of Frank Rijkaard. In these early years, he had more injury absences than he would later on, and though he contributed goals to the team, he was not yet the goalscorer he became. Samuel Eto’o and Thierry Henry were nominally the team’s chief goals men in this era and while Messi’s third season (2006-07) saw him chip in with 14 La Liga goals, the following season saw his goalscoring regress somewhat and he managed just six non-penalty goals.

Messi’s creativity saw a different trajectory. With a mere three assists in total across games played between 2004-05 and 2006-07, he made a large leap forwards in 2007-08 and recorded 12 assists. In truth, he played a similar volume of minutes in the each of these later two seasons and his expected goal assisted values were fairly similar (around 6 or 7 per season), but his teammates converted far more readily later on.

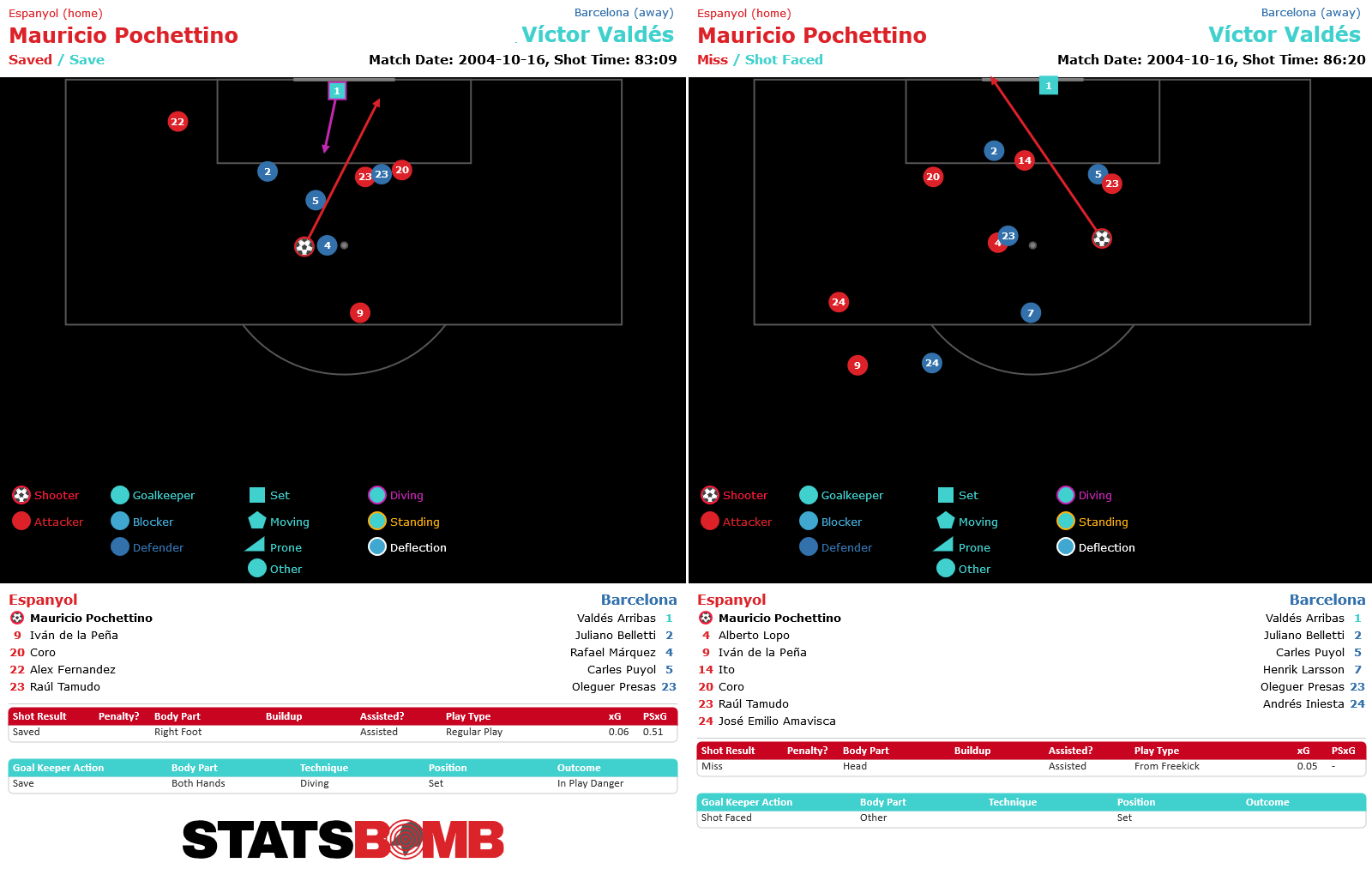

There are some fun angles too, even from the very start. In Messi’s very first appearance, a nine minute run out in an October 2004 fixture against Espanyol, it was not Messi who threatened to score but current Tottenham manager Mauricio Pochettino, who had two shots during the time Messi was on the pitch:

During those first nine minutes, Messi attempted four dribbles, two of which he completed and then was fouled straight after. Veteran players did not take kindly to this 17 year old running rings around them, a trend that continued throughout the early seasons in which his fouled volumes were consistently high.

All the Dribbles

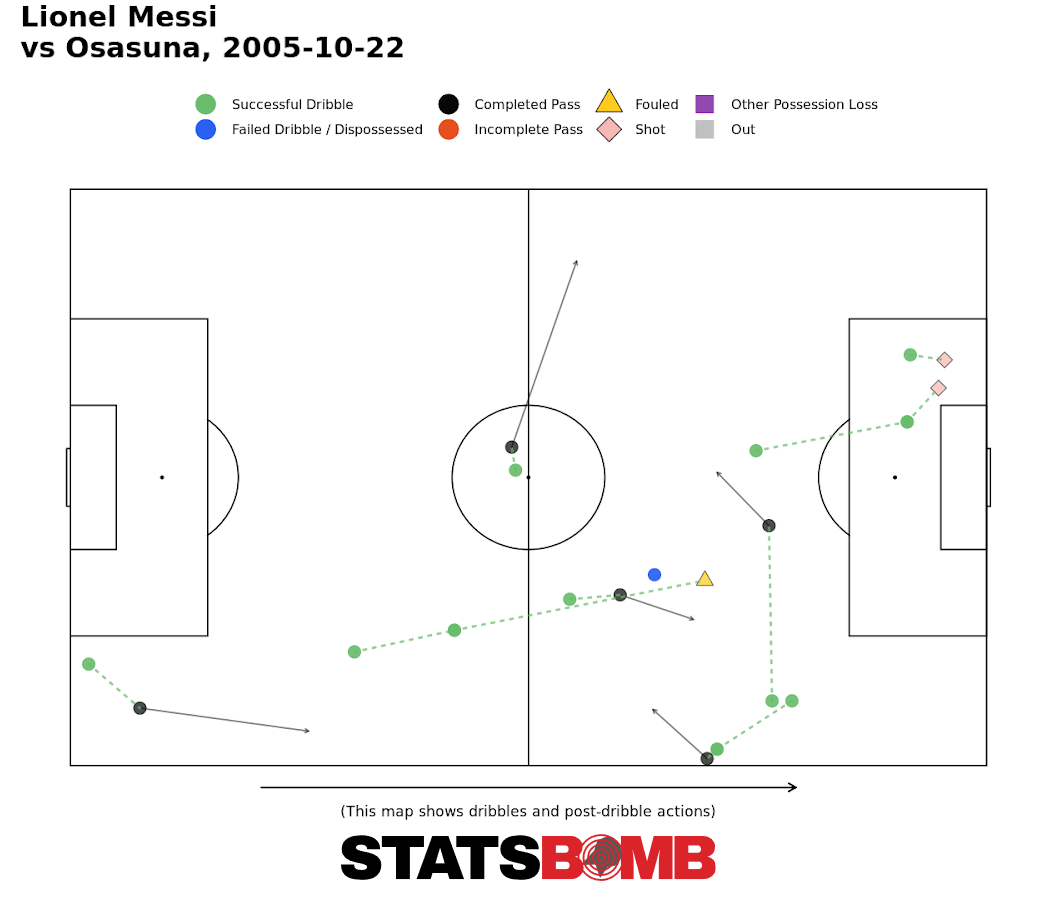

One of the angles that emerges quickly from the early dataset is how fearsome a dribbler Messi was. Even in his very first start against Osasuna in October 2005, he was terrorising defences. He recorded an impressive eleven completed dribbles (on a tough day for the Osasuna defence, Ronaldinho also completed nine):

It is no wonder the Barcelona faithful took Messi to their hearts instantly, he was box office even at 18.

This dribble proficiency is perhaps the strongest hallmark of these early seasons. In 2005-06 he averaged 7.4 completed dribbles in every 90 minutes played, he averaged 7.1 in 2006-07 before kicking upwards from that in 2007-08 to record 8.4 per 90. All of these volumes are greater than any player in the big European leagues across the last two seasons and unlike some talented but erratic winger types, he always had tangible goal contribution outputs to go alongside the zip.

This last season, Sofiane Boufal comes closest with 6.9 per 90, but his goal contributions are tiny (3 goals and 3 assists in 2195 minutes). Poster boy for dribbling Adama Traoré only logged 5.1 per 90 (one goal and one assist in around 1000 minutes). Neymar gets close in 2017-18 (5.7 per 90), and certainly passes the goal contribution test but essentially young Messi was a step above them all. He’s even ahead of himself in this regard with 4.6 successful dribbles per 90 in 2018-19 and 5.3 per 90 in 2017-18. Even Messi conforms to the population trend that dribble volumes decline as players age, it’s just he remains in the top tier even as he turns 32.

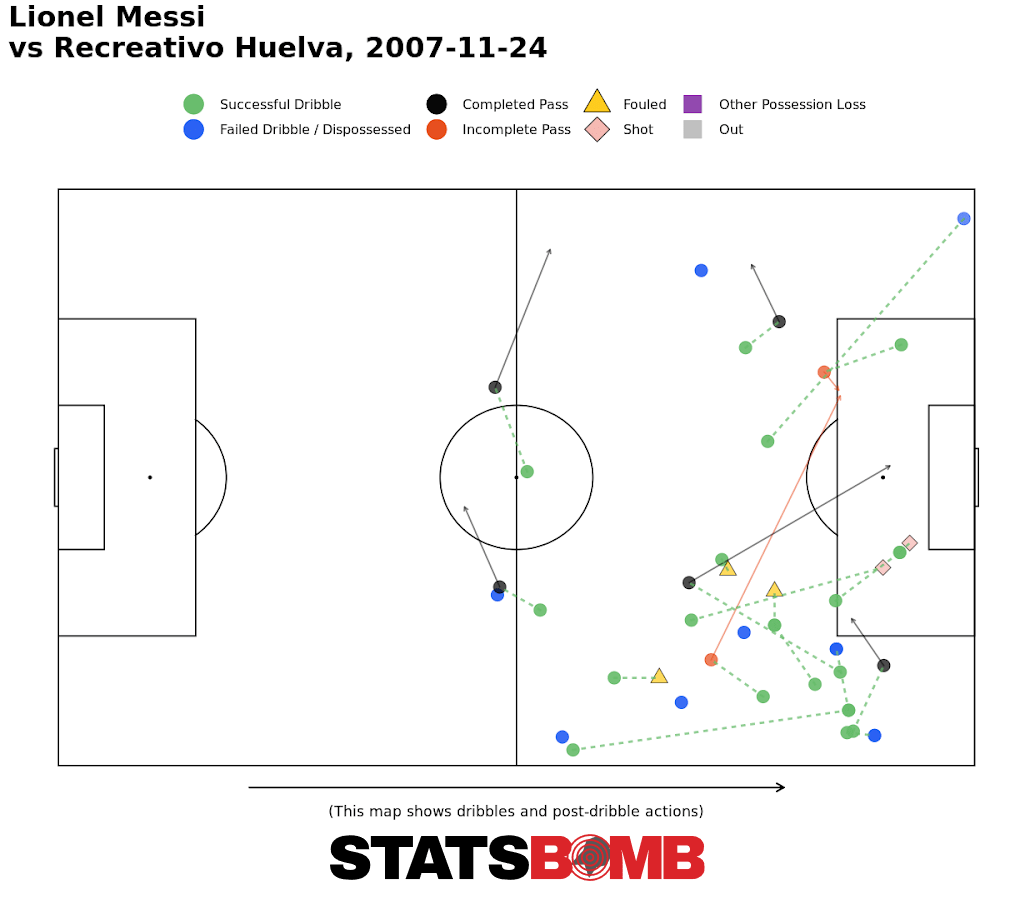

There were nine games in these early seasons in which he recorded more successful dribbles than the 11 in his first start with a high of 18 recorded in this November 2007 game against Recreativo Huelva:

To dribble successfully so frequently is a scarce skill, indeed when we compare to 2018-19 La Liga, only Ousmane Dembélé (14 vs Leganés) and Sofiane Boufal (12 vs Atlético Madrid) have got anywhere near this level (Messi’s 2018-19 season high is 10 vs both Real Betis and Atlético Madrid). It’s worth noting that frequently teams go entire games recording fewer dribbles than young Messi did. He was a class apart and from his early days was almost certainly the most frequent and effective ball carrier in Europe and as such, probably the world.

We often see a player beaten by an elaborate piece of skill and the idea that they’ve been “ended” by it is mentioned. Spare a thought then for Espanyol’s Clemente Rodríguez who in January 2008 was dribbled past six times in 90 minutes–the joint most pain Messi inflicted on one player during a single game. He made only two further La Liga starts for the club before leaving that summer. Also perhaps a moment of reflection for Angelos Basinas and Fernando Varela who were representing Mallorca during the early period of Messi’s career and both saw the back of him eight times in total as he dribbled past them, the joint most in the sample.

Messi the Shooter

The evolution of Messi’s goalscoring is not as linear as might be imagined. While the run through to 2006-07 was excellent–and that season featured a notable hat-trick against Real Madrid, including a last minute equaliser–2007-08 saw Messi’s role skew away from that of being a predominant shooter. Later in his career, Messi’s shot volumes became much higher, up around five per game, but through his teenage years he was less a volume shooter and his locations were occasionally sub-optimal. In 2007-08 his average expected goal per shot value was around 0.08 per shot, significantly down on the breakthrough years when from open play it was more like 0.14 to 0.15 per shot and a complete outlier compared to all his other seasons. See here:

We do see Messi getting into two familiar zones in those last two seasons though. Evidently coming from the right flank and arriving on the edge of the box or, surging deeper in to find a shot heading towards the right corner of the six yard box. These were Messi trademarks early on, but only later did he successfully add the more central shots that are essential for any high volume goalscorer. We will see more of that as the series progresses, and heavily so as he thrives in Pep Guardiola’s teams.

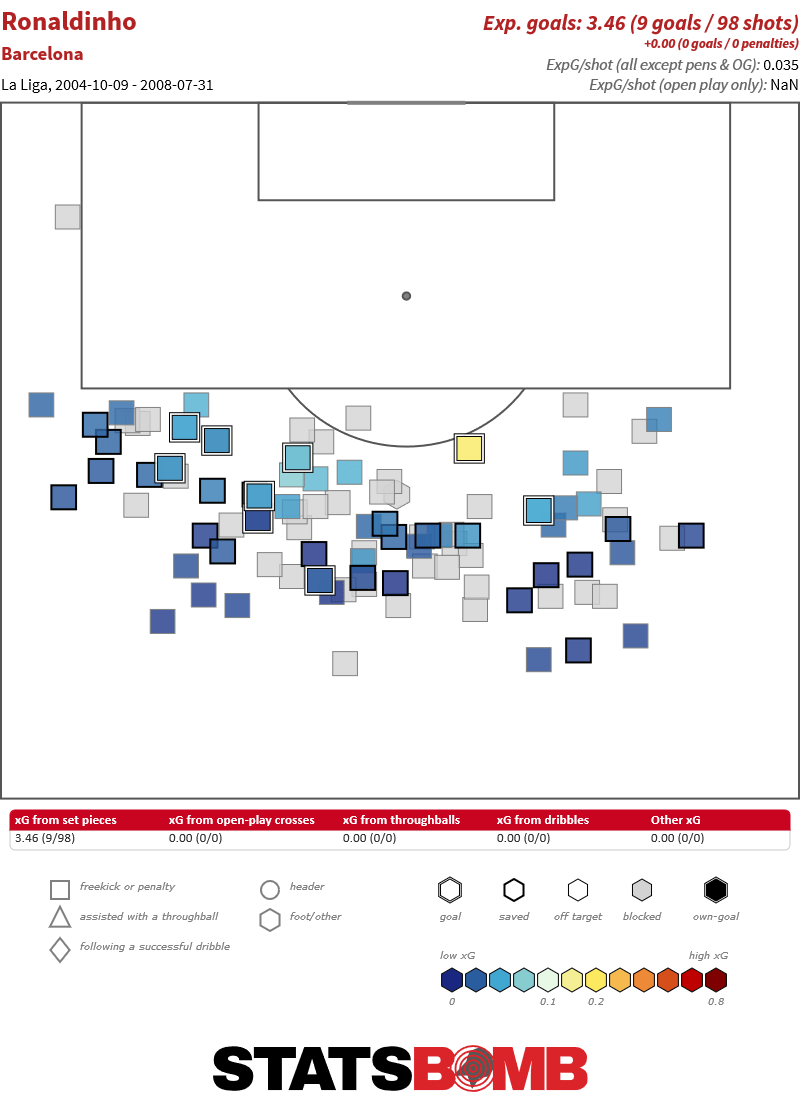

It’s also worth noting that he was yet to be a free kick taker. We see only four in these early seasons and no goals. Why? Step forward Ronaldinho. He was a core member of this group and as the senior man and extravagantly talented himself, in this era he was responsible for free kicks. From the matches collected–only those that involved Messi–we can see Ronaldinho was a prolific dead ball specialist, there was simply no reason to pass the job over:

Indeed, one of the pleasures of this project is the ability to examine Messi’s supporting cast, both for and against, with many fondly and not-so-fondly remembered Clasicos featuring within the dataset.

Creative Passing

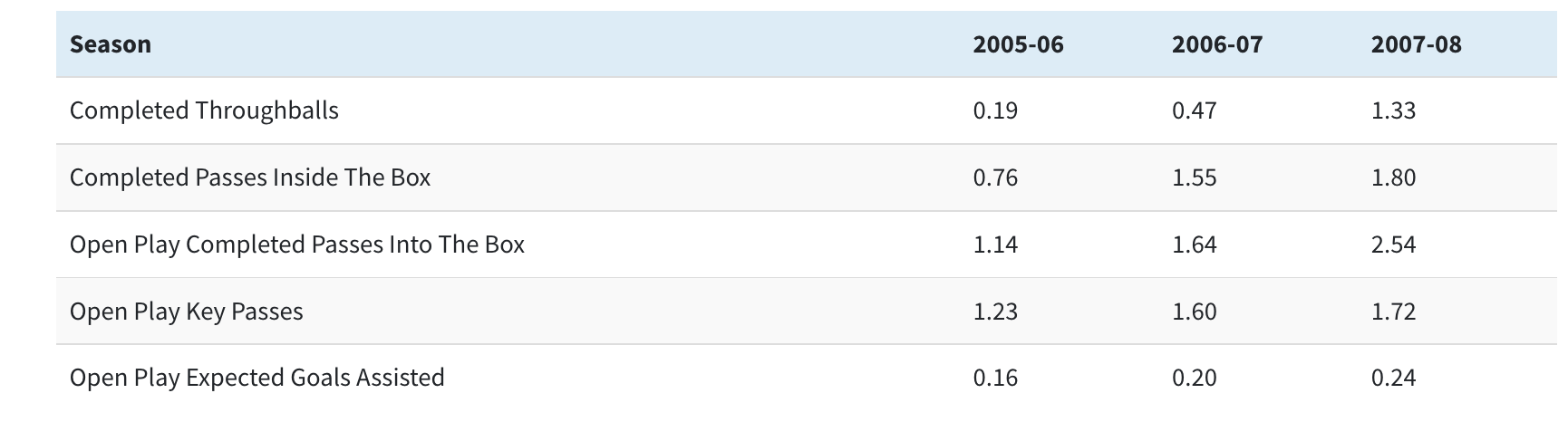

The first three Messi seasons in which we saw him play significant minutes (he was only on the pitch for 91 minutes during 2004-05) show a clear progression in a bunch of passing metrics:

This consistent development around a specific area of Messi’s game feels like a classic transition of a young player learning his trade. The dribbles were there from the start but often we see players who can beat a man with a dribble but don’t develop creative passing to go alongside. For Messi, this possible faultline was navigated readily, and by the time he was a consistent starter in the Barcelona first team, the ways in which he could hurt the opposition were multiple.

So that gives us a flavour of what the dataset contains. StatsBomb data contains footedness on all shots and passes, unique pressure events, shot freeze frames denoting all defender and fellow attacker locations for every shot and a wealth more besides.

There are many angles in which this dataset can be interrogated, so do get involved with the fun. This dataset sits alongside our Women’s World Cup 2019, Men’s World Cup 2018, NWSL and FAWSL datasets as freely available and perfect for testing ideas in analysis and visualisation. Football will need competent data analysts and technicians ever more in the coming years. If that’s the direction you want to travel, Lionel Messi may well be able to help you get noticed.

Thanks to all the StatsBomb team for their work on this project. It’s been a huge effort to coordinate collection, video sourcing, timelines and analysis to land this where we have. Ted can take the credit for the specific vision and plan, while I’d like to thank Euan specifically for his contribution to analysis and visualisation work for this post.

Roll on part two next week, that’s the Pep Guardiola era and Messi the Goal Machine.