We continue our series on the history of the European Cup with a look at the 1972 final between Ajax and Inter Milan. Last week, we covered Real Madrid’s victory over Eintracht Frankfurt in 1960; over a decade on, much has changed.

Ajax are the competition holders following their success over Panathinaikos at Wembley in 1971, while Inter, two-time winners in the mid-1960s, are back in the tournament for the first time since their loss to Celtic in the final of 1967. Ajax’s 2-0 win here would be followed by a third consecutive triumph against Juventus in 1973.

The Ajax Revolution

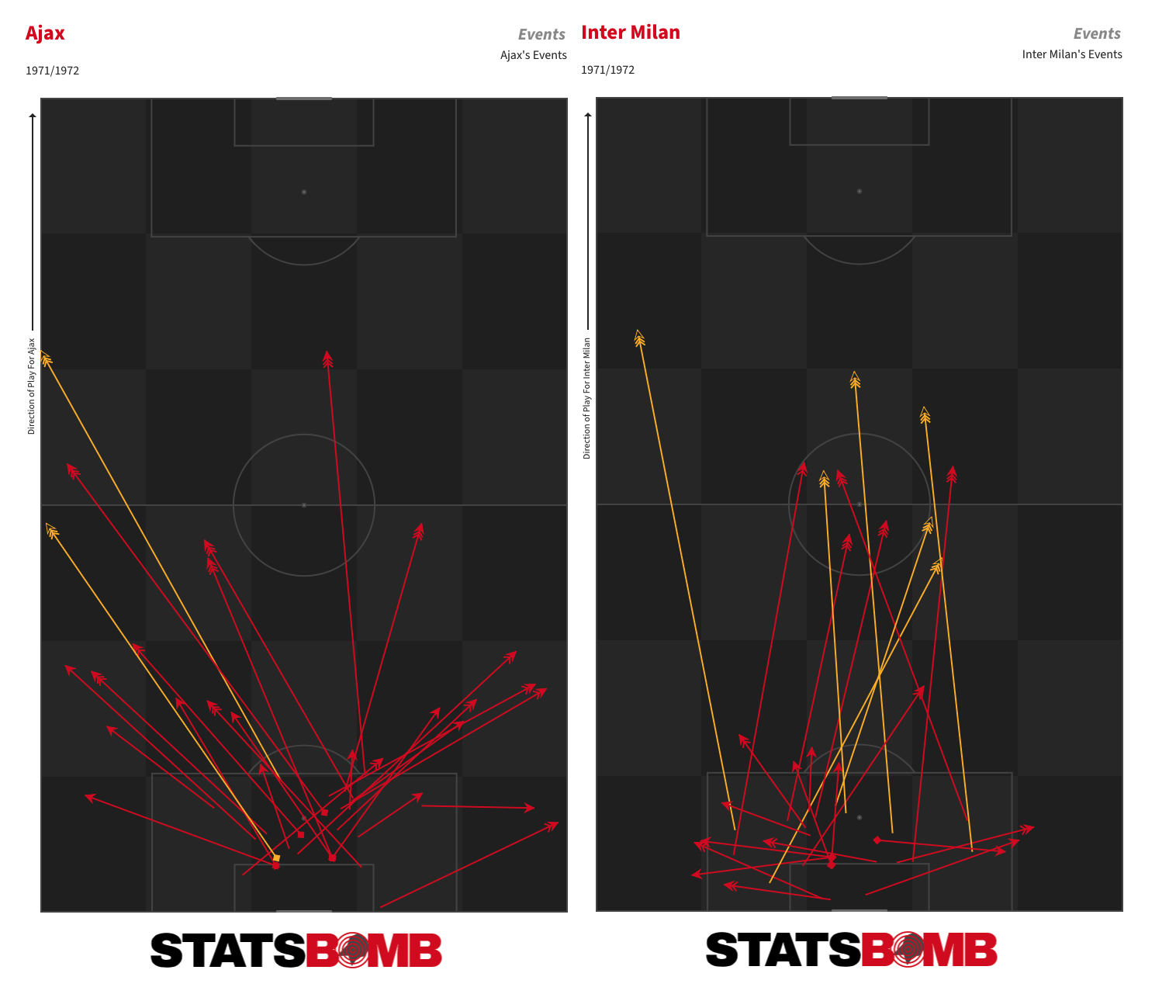

This match immediately feels more akin to the modern game than the 1960 final did. The formations are familiar: a 4-3-3 for Ajax and a 4-4-1-1/4-2-3-1 for Inter. Ajax are using squad numbers. Passing completion rates are up, there are less long balls, longer spells of possession and more attempts at collective play. The distribution of the two goalkeepers looks much more like that of their contemporary equivalents:

This Ajax side were the early prototype for the press and possess football of today. They regularly contested possession in opposition territory and when the ball was won, moved forward swiftly into shooting positions. The rhythm at which they played and their positional flexibility were unlike anything seen before, although it must be noted that Carlos Peucelle would later argue that River Plate’s La Máquina side of the 1940s were the first template for this style of play. There is some evidence that Rinus Michels, the Ajax coach who got the Total Football bandwagon rolling, was inspired by watching a Millonarios side that featured Adolfo Pedernera, the hub of that River team. It would, though, be fair to say that Ajax and the Dutch national team were its first proponents in a widely televised era.

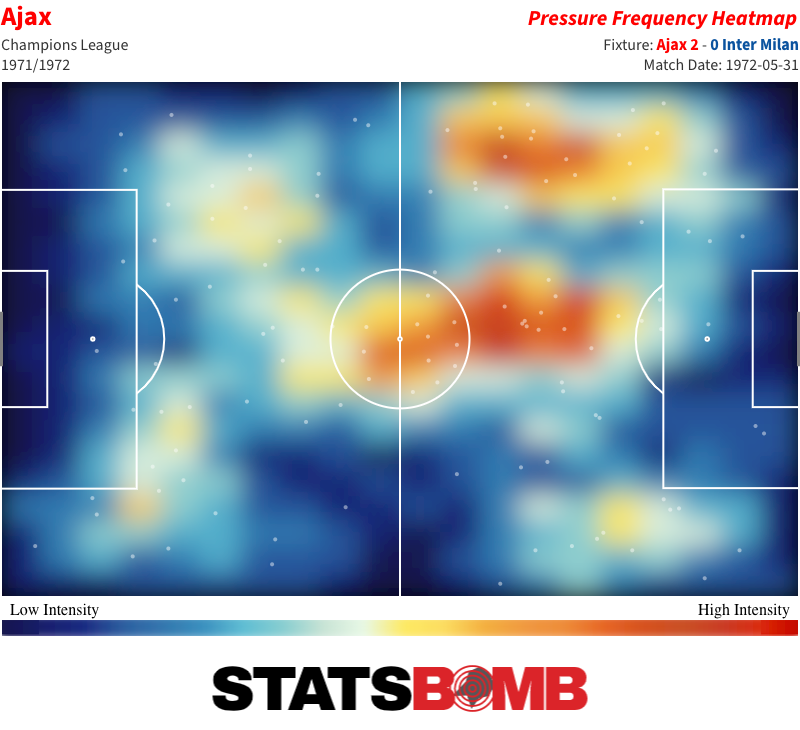

Ajax’s press in this match isn’t quite as aggressive and chaotic as that of the Netherlands at the 1974 World Cup, but they are still quick to close down, and they also step up swiftly to force offsides. When they lose the ball, it doesn’t usually take them long to regain it. They established clear territorial dominance, particularly during a first half in which Inter were penned in. The difference in the locations in which the two teams retrieved possession is striking:

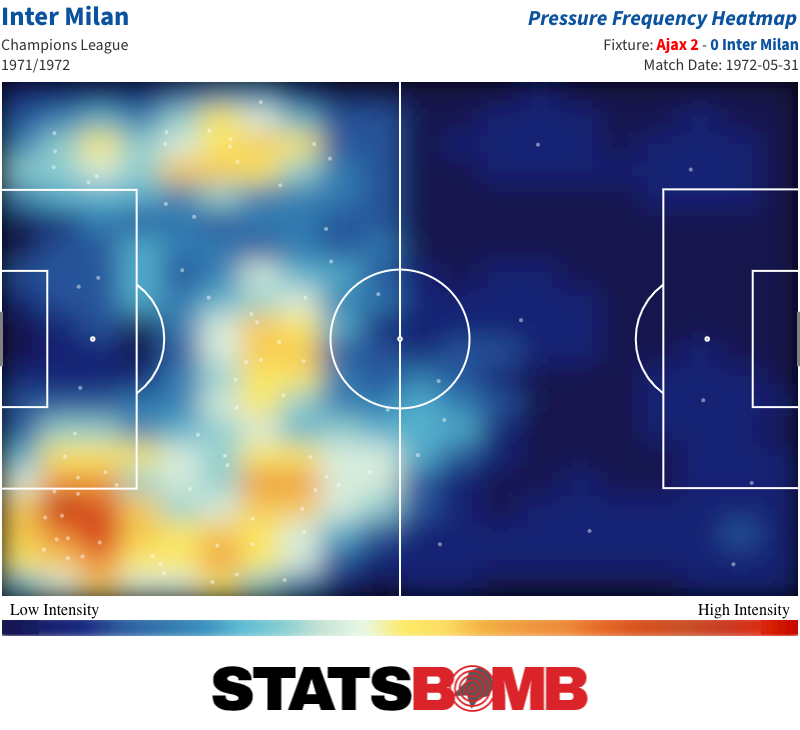

As are the match-long heatmaps of their pressure locations:

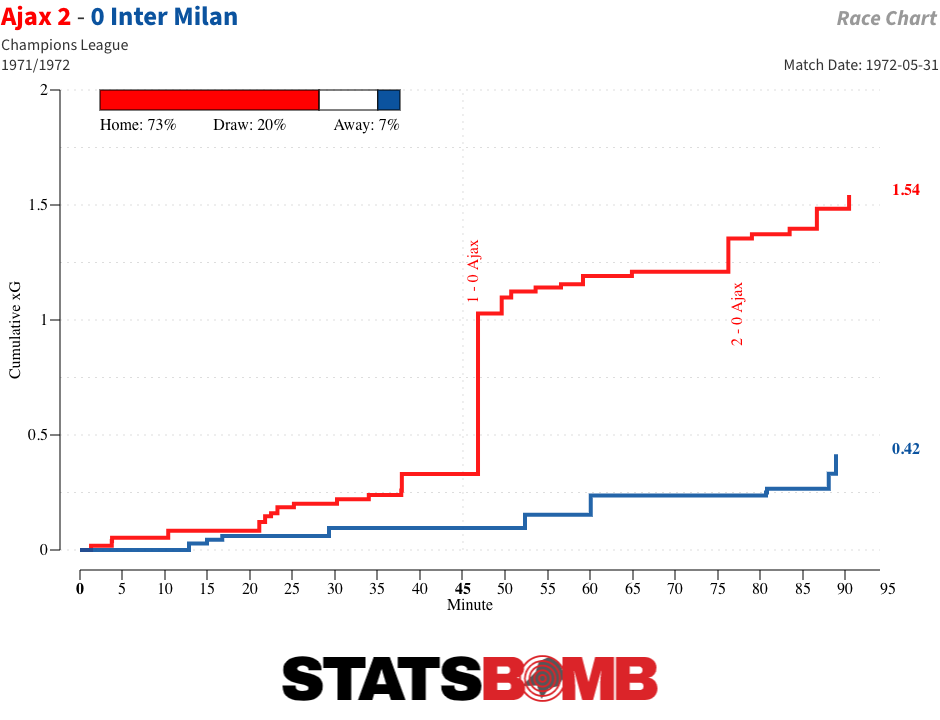

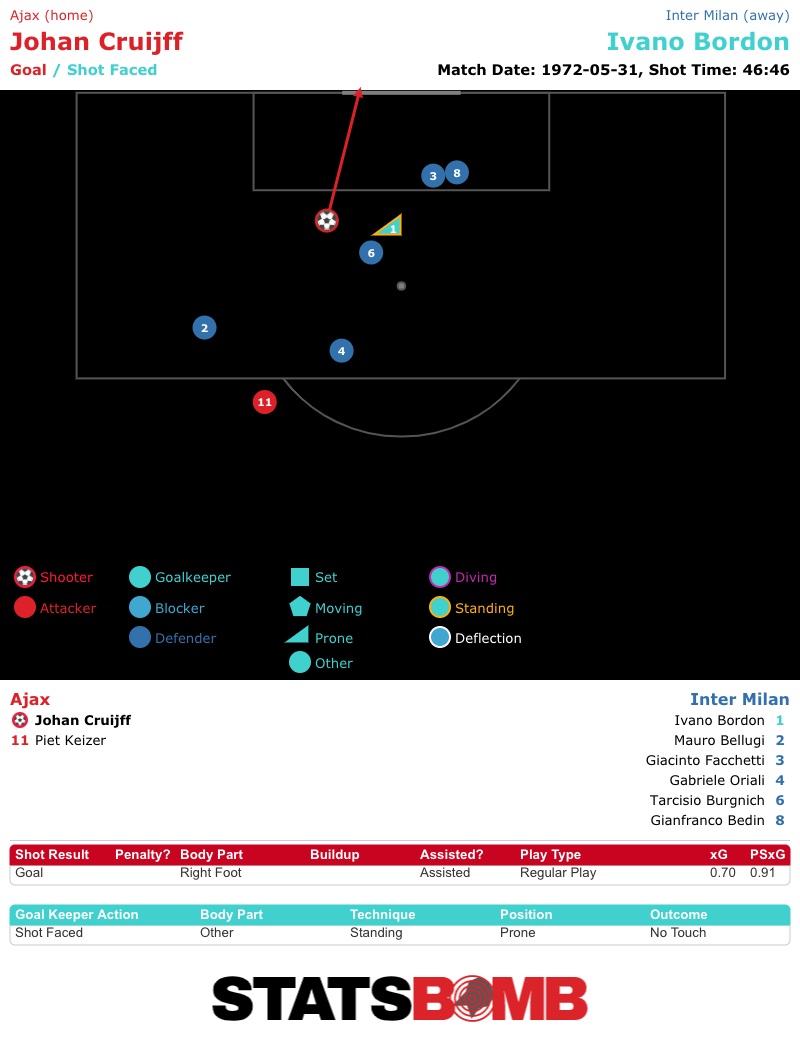

Overall, Ajax dominated in terms of territory, possession, shots and expected goals (xG). Two goals from Johan Cruyff, the second a header from a left-wing corner, saw them to victory.

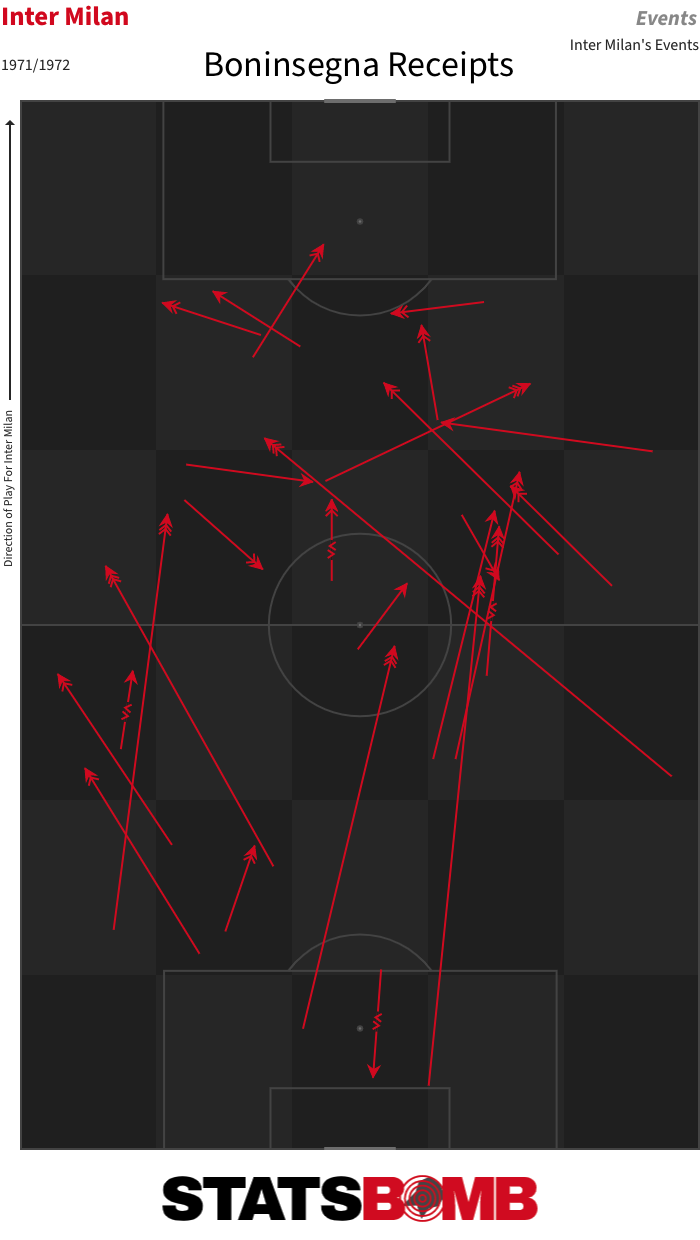

This Ajax team are largely thought of as an attacking one, but their approach was often just as, if not more effective in stifling their opponents. Their three consecutive European Cup triumphs in this era were all coupled with clean sheets. In this match, Inter were barely able to work the ball forward. When they did, it was usually thanks to the astute movement of Roberto Boninsegna off the front and into the channels.

But Boninsegna, Inter’s top scorer for seven consecutive seasons between 1969 and 1976, barely got a sniff at goal, and he and his teammates were only able to muster 0.42 xG from their 10 shots. Sandro Mazzola picked out a couple of nice passes in transition but was largely unable to influence things, partly due to the close attention of Johan Neeskens.

Mazzola and the other holdovers from the Grande Inter of the 1960s still weren’t all that old at the time of this match. Gianfranco Bedin was 26; Mazzola and Giacinto Facchetti, 29; and Jair da Costa, 31. Only Taricisio Burgnich, at 33, was obviously past his prime. Yet while their players might not have been, their style of play was certainly made to look so by a trailblazing Ajax side.

Long-Range Shots and Lots of Crosses

Where Ajax’s approach deviated from the modern game was in what happened once they got into the final third. Two of the key early takeaways from statistical analysis of football were that central shots closer to goal are far more valuable than wider and long-range efforts, and that crosses are generally a fairly inefficient means of creating chances.

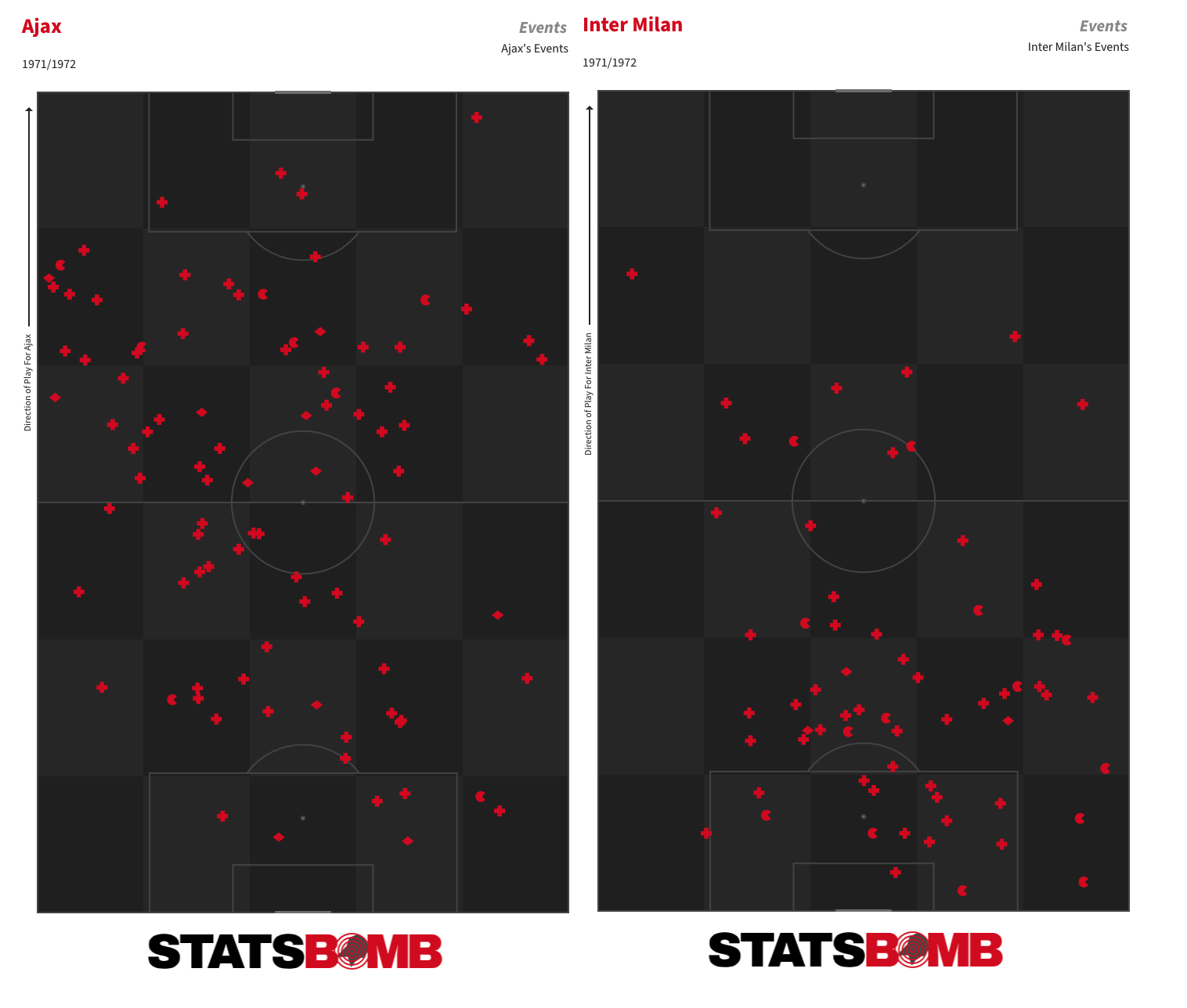

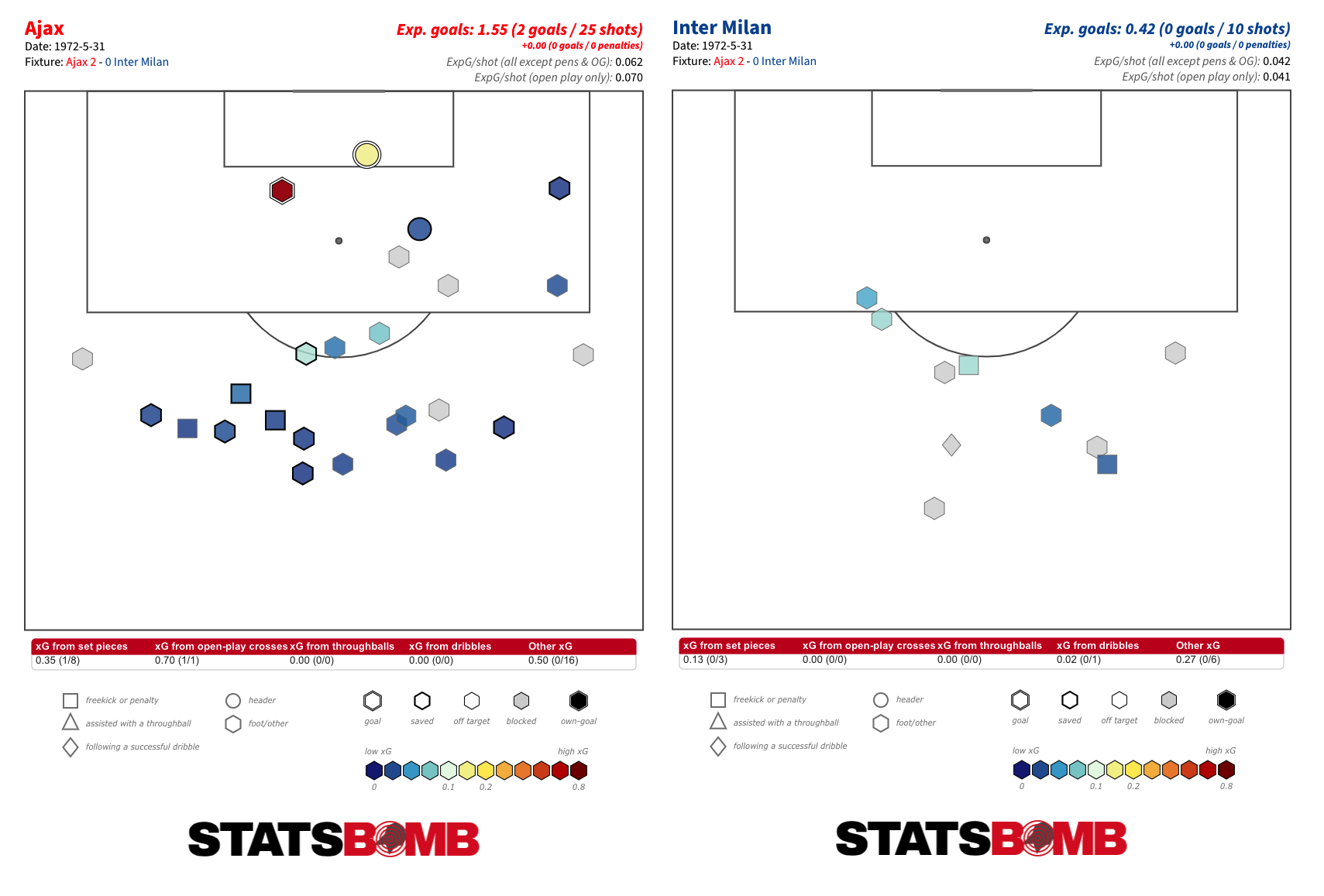

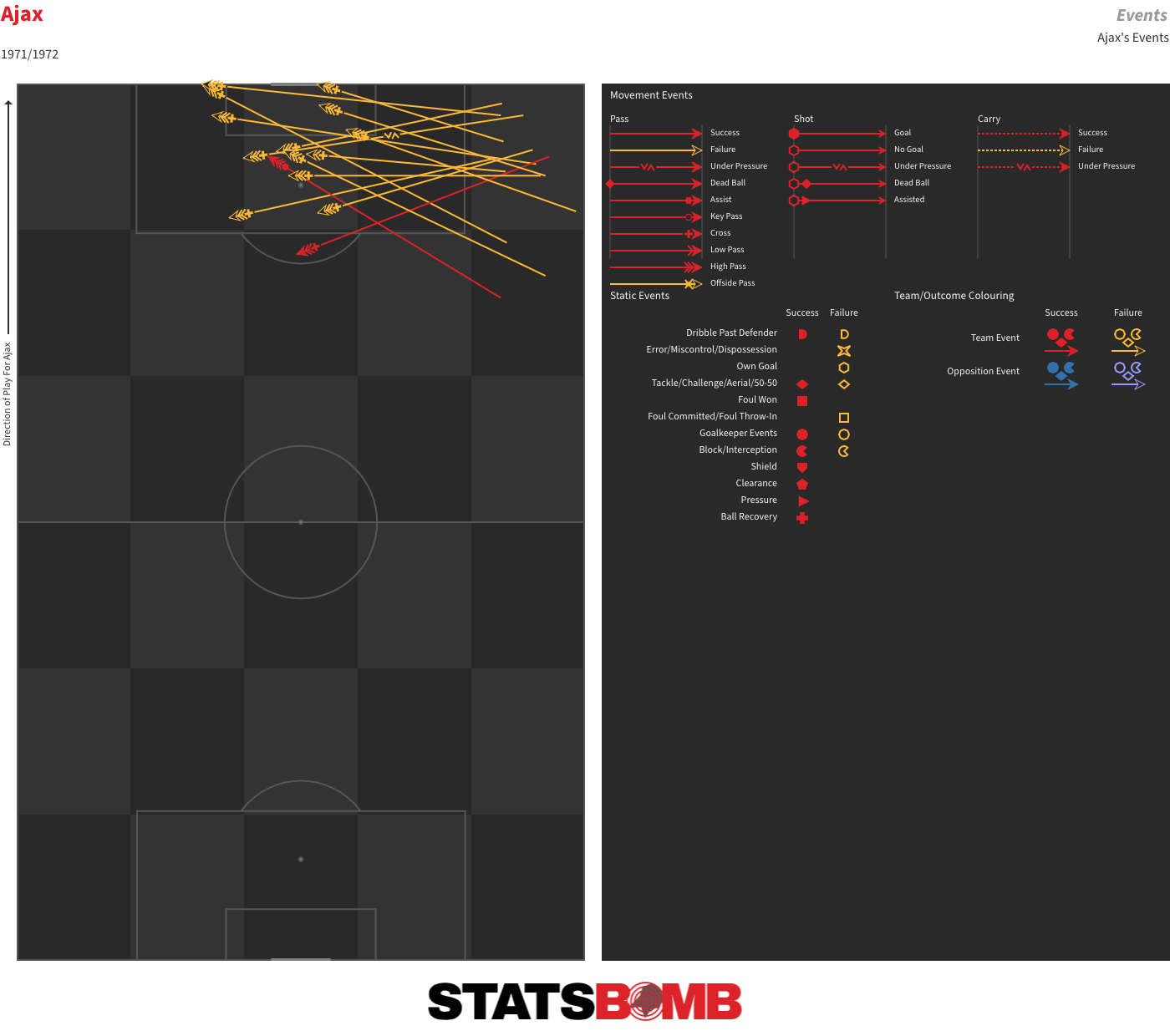

Clearly neither team got the shots memo:

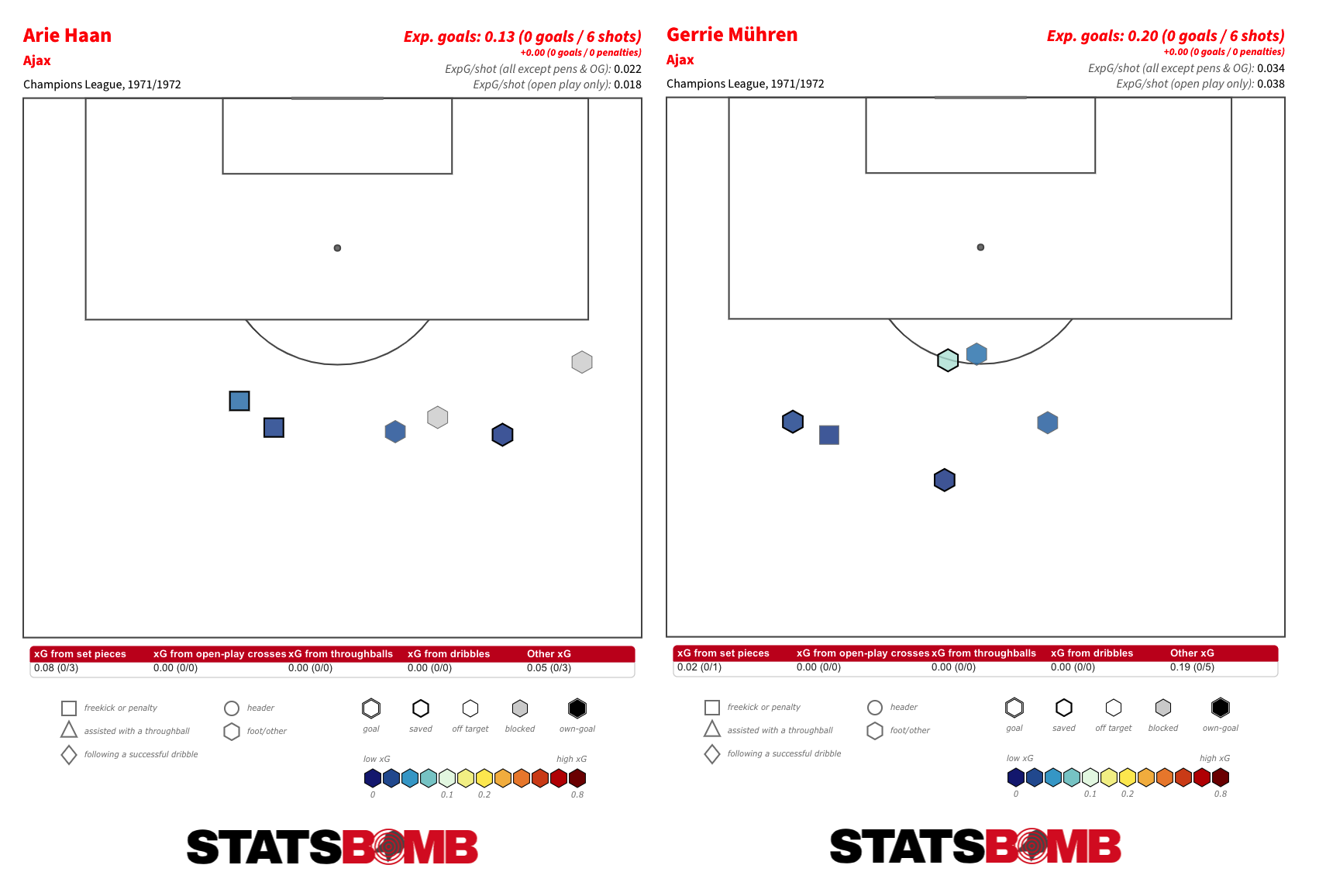

A shoot-on-sight policy particularly prevailed among the midfielders of Ajax:

Given their territorial dominance, Ajax really struggled to create good-quality chances from open play. Aside from Cruyff’s opener, none of their other 16 shots from open play were even 1-in-10 opportunities. There were even a couple of 1-in-100 swings. Indeed, that Cruyff goal, an easy finish after goalkeeper and defender collided to provide him with an open goal from an otherwise fairly harmless hanging cross, accounted for 58% of Ajax’s open-play xG.

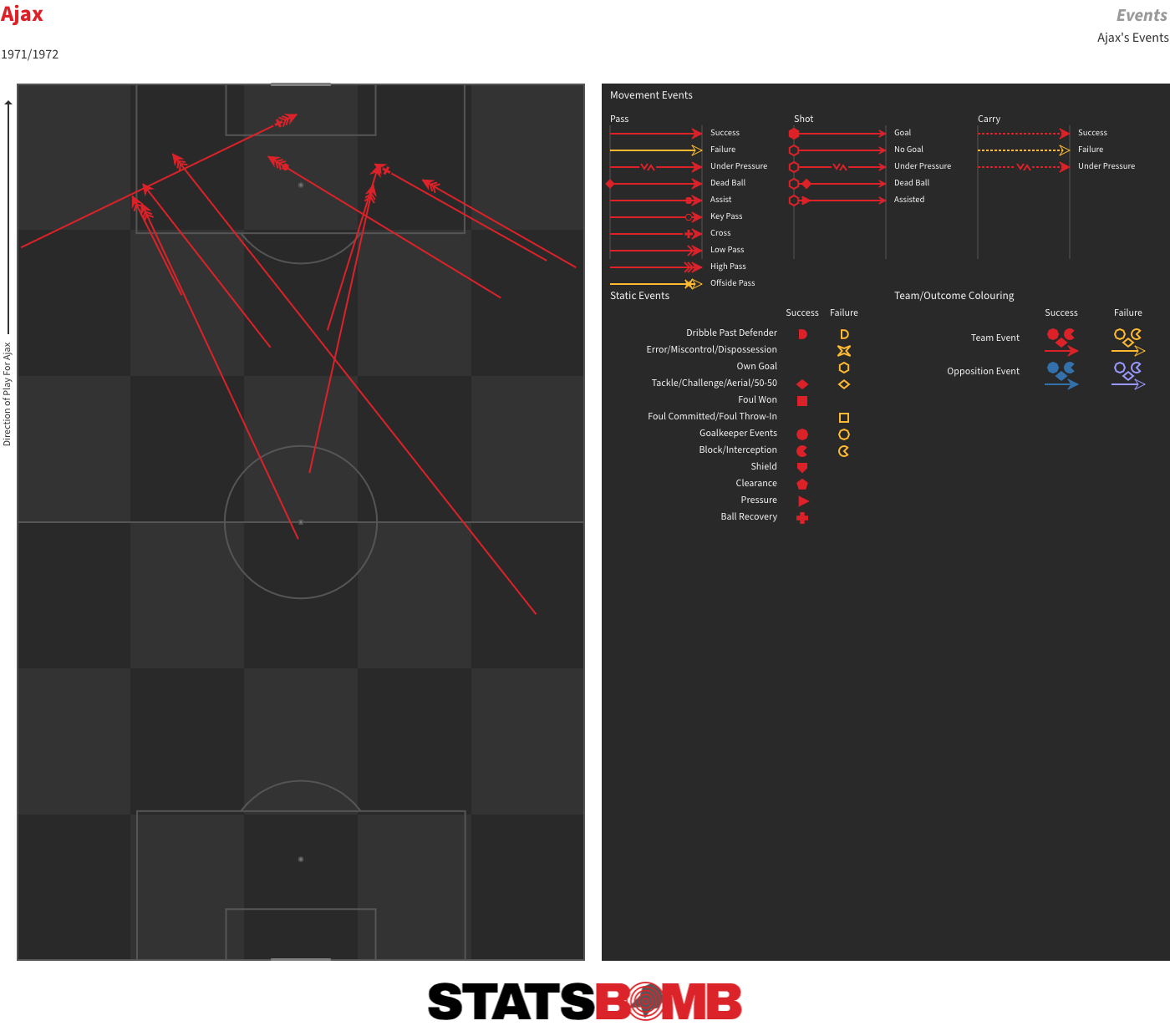

That was also the only effort on goal to directly originate from one of the 29 crosses Ajax swung into the Inter penalty area. For comparison, the highest team average in last season’s Champions League was 14; the competition average, 7.84. Over half of their attempted box entries came from crosses, versus a competition average of 28% in 2018-19. Just two of the 15 deliveries from the right by Sjaak Swart and the ever-advancing full-back Wim Suurbier found their target.

This graphic of Ajax’s box entries shows how infrequently they moved the ball through the centre into the area. There was a cute early pass from Arie Haan and a couple of other incursions but not much given how much time they spent in the Inter half. Neither they nor Inter completed a throughball.

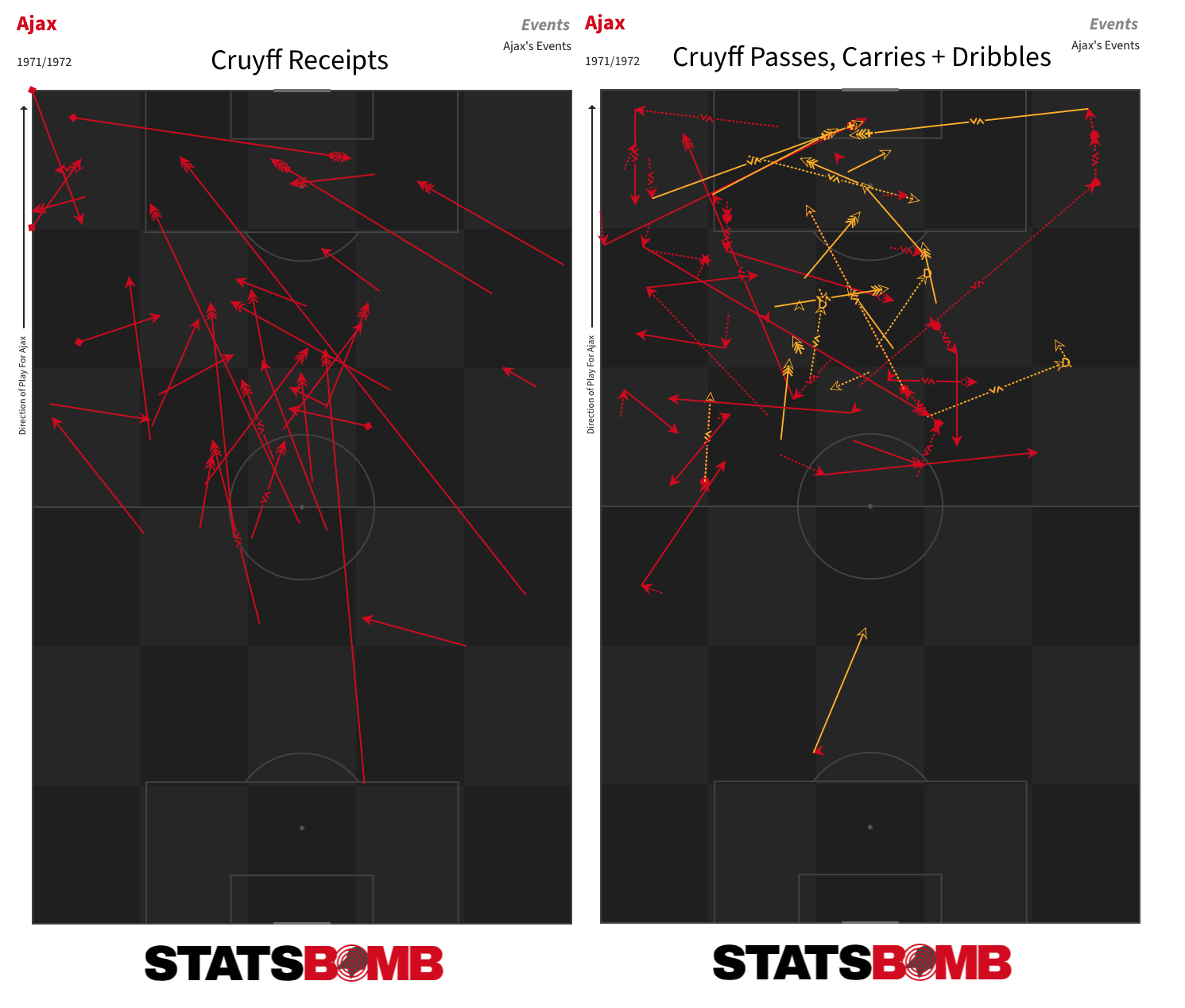

Johan Cruyff

Cruyff scored both of Ajax’s goals in this match, but it doesn’t act as a particularly good example of the idea we have of Cruyff as orchestrator of play. While he did drop back to receive in midfield at times, he attempted more individual actions than collective ones, and completed just 53% of his passes -- only two players, both for Inter, completed less. It was his supple changes of direction and neat burst of acceleration that stood out.

In amongst all of those Ajax shots, Cruyff only set up two, worth a paltry 0.05 xG. Three teammates moved the ball into the penalty area more often than he did. Where he did lead the team was in touches inside the area. Indeed, from this super small sample size of just a single match from a 20-year career he profiles as more of a mobile centre-forward than a playmaker masquerading as one.

Some Random Numbers and Observations

- the players who took part in this match were more ambidextrous than most. There were seven players within a 15% range of an even 50/50 split of passes between both feet. Inter’s Boninsegna had an exact split; Cruyff was only three percentage points off. For comparison, there were only two players within that 15% range in the 1960 final; and just one in 2019.

- the number of dribbles was slightly down from the 1960 final, but the figures of 47 attempted and 30 completed were both still well above those usually seen in the modern game.

- this match featured something we very rarely see these days: an indirect free-kick for obstruction inside the area.