Of all sides in the Premier League, Leicester might have had the hardest time in recent years of gauging what realistic expectations should be.

The highs of winning the title in 2016 may never be beaten by any team in English football for a generation. Of course, this set the bar at a certain level, and Claudio Ranieri’s brief flirtation with relegation (though the numbers always had them relatively ok) saw him get the sack the following year. Successor Craig Shakespeare rode a huge positive conversion rate into a long term contract, with a negative one getting him the axe shortly afterwards. Claude Puel did stabilise things, but a little too much in the eyes of many, with the perceived dullness of his side giving way to the hoped for excitement of Brendan Rodgers.

Results have been good, with 6 wins out of 11, and the general sense is that fans are happier with the more positive playing style. But is this form sustainable? Is Rodgers helping to build the foundations for a strong Leicester side that can challenge the top six, or is it a false dawn? Let’s take a closer look.

What Rodgers Inherited

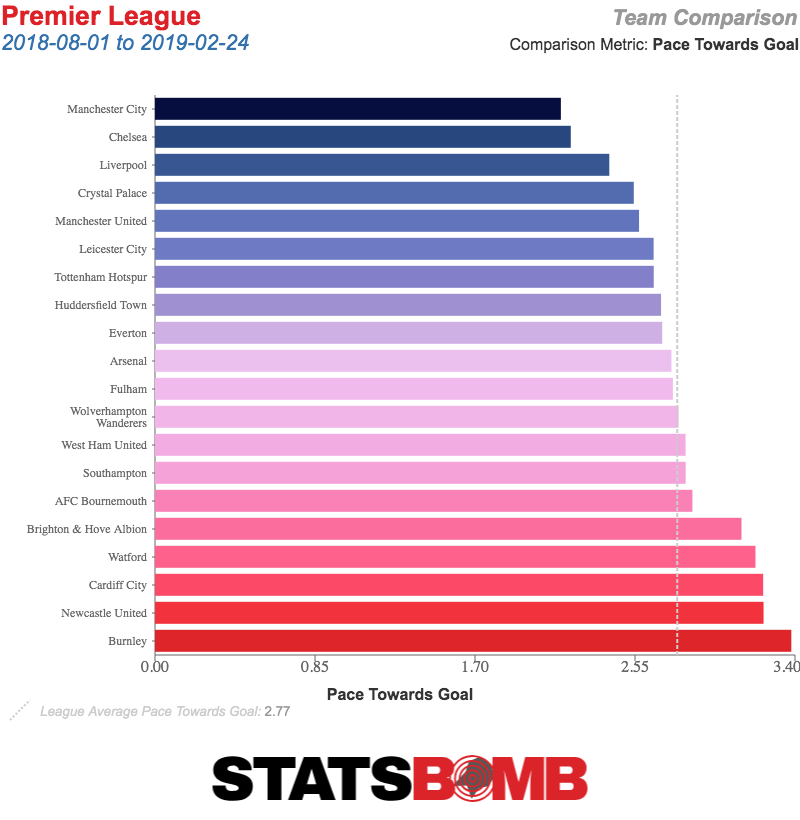

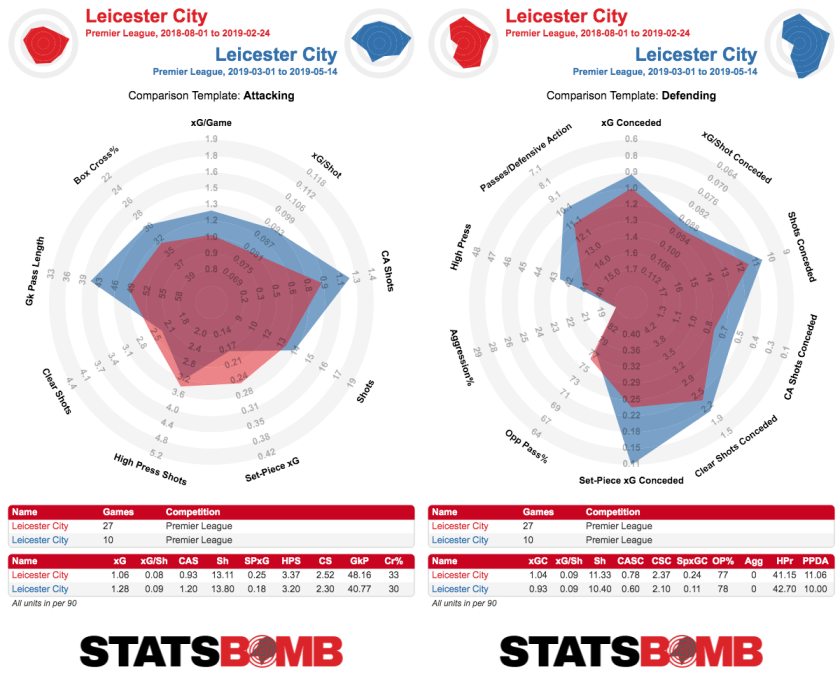

Leicester were not a bad side under Puel, but they also weren’t anyone’s idea of a good time. By expected goals per game, they had the 12th best attack in the league and the 7th best defence. They defended deeper than the average Premier League side, ranking 16th in the league in terms of how high up the pitch they made their average defensive actions. Sitting back without the ball was likely not in and of itself a problem for Leicester supporters, with it being a cornerstone of the magnificent 15/16 season. What may have caused more irritation is the attacking approach. The side’s pace towards goal, the speed at which their possessions that end in shots reached the chance, ranked them as the 6th slowest attackers in the league, and the second slowest outside the top six. Similarly, the team was rated 15th in the division for “directness” of attacking moves. For the most part, fans in England are often comfortable accepting a deeper defending style if it’s met with fast counter attacks. A combination of compact defending without the ball and a stale, slow approach with it, however, tends to frustrate people to a great degree.

The shape of the side was a fairly conventional 4-2-3-1. Puel’s preferred midfield partnership of Wilfried Ndidi and Nampalys Mendy might sum up his approach. Ndidi is a ball winning defensive midfielder, while Mendy is a patient recycler. The pair rank 8th and 10th for Leicester in terms of moving the ball into the final third, but that’s not what Puel wanted his midfielders to do, instead putting an emphasis on screening the back four and retaining possession. This was an effective team, yes. But it irritated fans (and, according to rumours, the players) enough that the change was made, and with Rodgers came the promise of exciting, entertaining football.

So What Is Rodgers Doing?

For all that Rodgers likes to present himself as a hero of playing “the right way”, the truth is that he has embraced a number of different approaches in his career. At Swansea, he certainly embraced a ball-dominant approach, managing to dominate possession in most games with a team newly promoted to the Premier League, a feat almost unheard of. Upon moving to Liverpool, the assumption was that he’d continue the so-called “Swansealona” approach but scaled up to the superior talent available at his disposal at Anfield. This was clearly his initial plan. “Brendan’s philosophy”, Luis Suarez claimed in his autobiography, “was to play on the floor, keep possession of the ball and, if we lost it, to pressure to get it back. Don’t panic, don’t play so fast as we had the previous season, look for the spaces at the right time”. A poor first six months, however, saw him make a dramatic u-turn towards a faster, counter attack based style aimed at maximising the threat of Suarez and new signing Daniel Sturridge. A million different formations were seen along the way. The following year, with Suarez having left for the Camp Nou, the team’s best results came when playing a defensive minded 3-4-3 system. At Celtic, he returned to a possession-heavy approach, but that’s hardly a shock considering the talent disparity at play. Rodgers is and remains something of a tactical chameleon, borrowing systems and ideas from elsewhere more than building a singular cohesive style at a club.

So what has Rodgers been up to at the King Power? Well, first of all, he has overseen an improvement in the side.

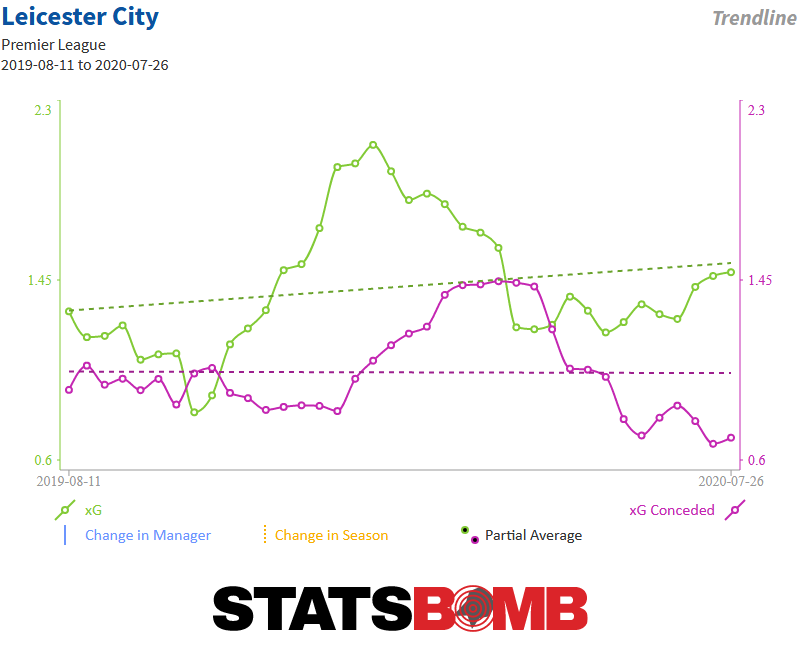

Leicester were putting up an expected goal difference per game of 0.02 under Puel that has risen to 0.35 since Rodgers took over. The majority of the improvement has come at the attacking end but there has been a defensive bump as well.

It seems a slightly odd quirk that Rodgers has overseen such an improvement in defending set pieces considering his reputation in that part of the game, though this is a small sample size so it might not be something we’d expect to continue. Stylistically, though, we can see that Leicester are pressing higher up the pitch, and now make their defensive actions further up than the league average, if not by a huge margin. The team have added an extra 4% to their possession figure, again not a huge change, but an indicative one. Kasper Schmeichel is passing it shorter than previously, and Leicester now have the shortest passing goalkeeper outside the top 6. This couldn’t be further removed from the kind of football that saw the Foxes win the Premier League, but it’s a style with an attacking intent at its core, and for that reason it seems to be going down easier with the fans.

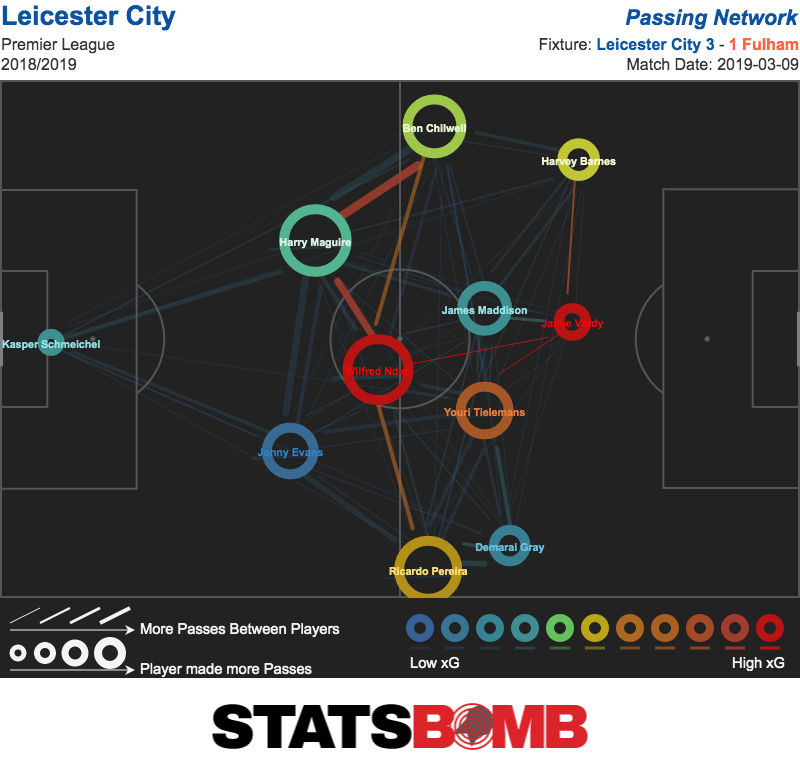

The saying is that good artists copy while great artists steal, and Rodgers is certainly a great artist in that regard. The main place he seems to be stealing from in this case is Manchester City. The first idea seemed to be to play a broad 4-3-3 system but, and taking particularly from Guardiola’s shape in this regard, using James Maddison and Youri Tielemans as “free eights”, given the freedom to push higher up the pitch than traditional central midfielders with Ndidi covering as the lone pivot. This passmap, from an early victory against Fulham, shows the shape of the team fairly clearly.

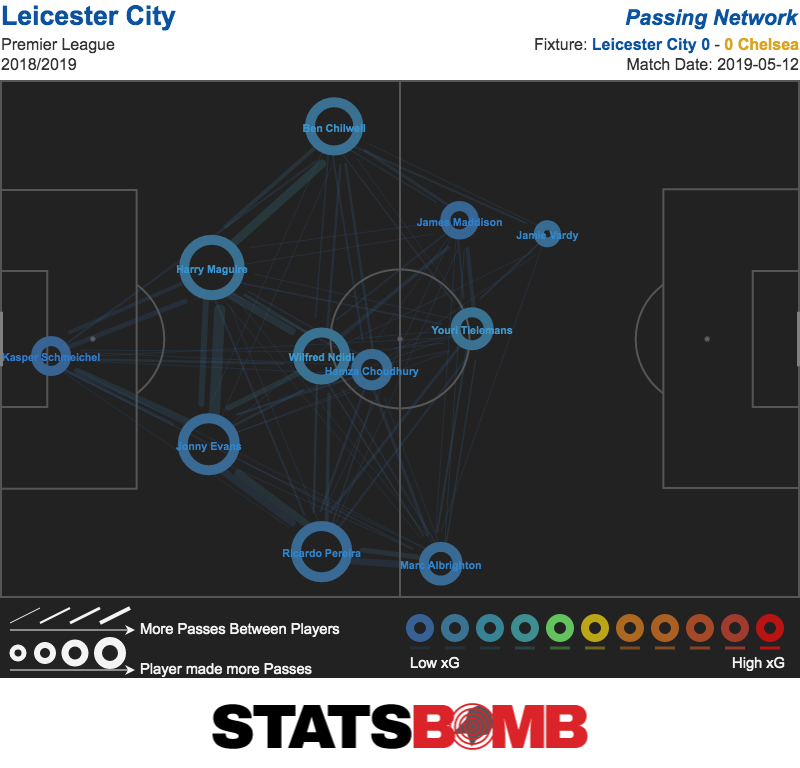

This system was trusted for most of the remainder of the season, even as Marc Albrighton came into the side for Harvey Barnes. The free eights would take up advanced midfield roles and the wide players would stay relatively wide. The very difficult run in for Leicester, with the final three fixtures against Arsenal, Manchester City and Chelsea, saw an important tweak. Hamza Choudhury, a natural ball winning midfielder, came in alongside Ndidi, with Maddison now positioned narrow on the left flank. Going for a more solid double pivot in big games is a fairly obvious tactical tweak, and Maddison’s instincts to drift inside from a wide position only added to the numerical superiority in midfield. Since there generally isn’t as much need to stretch the play and move the ball from side to side against stronger teams, as they are less likely to defend deep and form a compact block that’s difficult to crack, this is a move that doesn’t seem to have too many consequences. It speaks to Rodgers’ flexibility that he was comfortable making the change, and 4 points from 9 in these games is a return he can be proud of.

Leicester have felt for a little while now like a club on the cusp of really pushing on. The team’s average age of 26.3 is one of the lower figures in the league, but even that number doesn’t tell the whole story, with older players such as Jamie Vardy (32) and Wes Morgan (35) pulling the mean upwards. The new core of this team is with players such as Ndidi, Maddison, Choudhury, Harvey Barnes, Ben Chilwell and Demarai Gray, all yet to turn 23. Tielemans also fits into this category, and would be a terrific signing if the club can strike a permanent deal for him, though that remains to be seen. Rodgers seems well positioned to reap the rewards of a young squad likely to improve even if no major additions are made.

That transfer question, though, has raised some concerns. Leicester recently announced Lee Congerton as the club’s new head of recruitment, which appears to be a very direct Rodgers choice. With Congerton’s track record at Celtic and Sunderland, it’s hard to see any reason for hiring him other than a strong working relationship with Rodgers, so it certainly seems like the club have fully bought into the Northern Irishman’s ideas. Leicester do have good people working behind the scenes, with Mladen Sormaz newly hired as head of analytics among a seemingly strong team. In his time at Liverpool, Rodgers very famously clashed with then head of technical performance Michael Edwards, with the apparent view of Rodgers being that Edwards’ analytics-focused signings were not fit for standards. Since Rodgers left Liverpool, Edwards has been promoted to sporting director and overseen a hugely successful recruitment process that has led to the side reaching two Champions League finals. Granted, we’re obviously going to be in favour of the numbers people here at StatsBomb, but Rodgers might be wise to break previous habits and listen to the analytics advice this time. The odds of that happening, though, seem rather slim.

But Rodgers’ success has never come in building for the long term. In all of his jobs (save for a rough spell at Reading early in his career), he’s overseen a rapid improvement of the side in the first two years, then either left or seen things decay. It’s not hard to imagine the same trajectory happening here, and recruitment is a concern if the squad becomes weighed down with his own signings. For next season, though, things look bright, with Rodgers’ playing an attractive style of football while also improvising for specific players and situations. The club could be in for a really bright future, so long as they remember that the time will come to cut Rodgers loose.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association