It is often said that the life of a goalkeeper is unfair. Repeated brilliance and octopus-like saving talent can be forgotten in an instant if a moment of ineptitude or bad luck costs his team the game. This is nothing new. Throughout the history of football, the goalkeeper has only rarely been the hero and has suffered more than any other player in the hands of critics. Heurelho Gomes, a keeper who switched from the sublime to ridiculous with revolving door frequency is my particular favourite example of the dual nature of goalkeeping efforts.

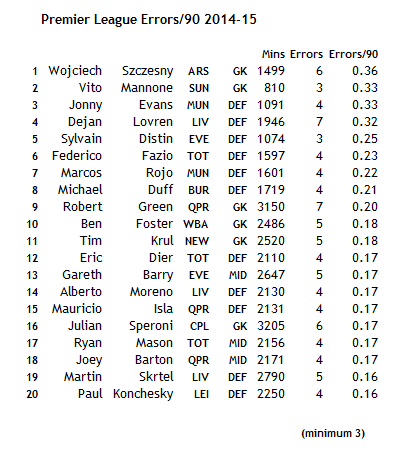

We can see the perilous nature of goalkeeping by looking at the rate of errors charged to players in the Premier League this year:

An excellent post from @shots_on_target last year looked at repeatability levels for errors, and found there was none. This follows simple logic, they are a non-regular event, and what defines an “error” is at least arguably subjective. None of this seems to have stopped players living or more relevantly dying by their error rates though, as parts of the table show.

Topping the table are two goalkeepers, Szeczesny and Mannone who have been cast out by their coaches. But as we see quickly, and given that it is a defensive measure, unsurprisingly, the centre back is particularly vulnerable too. Poster boy for “transfers that didn't go as hoped” Dejan Lovren had a horrific start to the year, so much so that he has struggled for minutes since and has a very low reputation amongst fans. Is he so bad? I'd suggest he hit a bad patch trying to settle into a new team and is unlikely to repeat these levels. This list is chock full of players that you can see have had difficult seasons; old players maybe losing their legs (Distin, Barry), players struggling to adapt to new teams or leagues (Lovren, Fazio, Dier, Duff, Moreno), the usual crowd of keepers (Krul, Green) and players hung out to dry by a failing system, but possibly not good enough (Mason).

Quite simply, I think errors inform selection decisions and on occasion time, patience and more context is probably required. Players do not become bad because they commit a series of errors in a short space of time, but in the cut-throat world of football, sometimes they are denied the opportunity to prove otherwise. And the centre back is vulnerable to the vagaries of their position.

So what am I focusing on errors for?

Well, last night's Champions League fixture between Bayern and Barcelona was a curate's egg for Bayern centre back Medhi Benatia. It started encouragingly for him as he scored a delightfully placed header to give his team the lead but then events took a turn for the worse. After being left calling for offside as Messi threaded a ball to Suarez who fed Neymar to score, he made one genuine error in charging out to challenge an already marked Messi leaving Suarez to dash clear and again feed Neymar. The piece de resistance was revealed via replays as Suarez outrageously spun him with a flick for the ages:

And this was all before half time! Poor Mehdi Benatia! At half time, Paul Scholes on ITV rounded on Bayern's defense and particularly Benatia and even many hours later, as I write, Alan McInally is on SSN telling me that Bayern are "defensively (...) nowhere near where they need to be to compete at the top end of European football". I'd contend the 114 goals shared amongst Messi, Suarez and Neymar this season could also be included as counter evidence to this knee-jerk analysis.

So what if I tried to convince you that beyond the obvious error for the second goal, Benatia had a really good game, indeed that he made contributions that marked out his performance as an exceptionally rare feat? Benatia's game brings to mind the quarterback who passes for 400 yards yet tosses up an interception to cost his team the game. It happens, it's what gets remembered but it is rarely the whole story.

It was noted by site owner, Ted Knutson, that Benatia had attempted four shots, made eight interceptions and succeeded with four tackles and that this was likely a rare combination of feats. It was, you have to go back some years to find a comparable numerical performance. Now whilst the defensive measures noted here, much like errors, are not noted for their usefulness in predicting future performance, they do offer a descriptive measure of involvement. Benatia was facing probably the finest front three in recent memory, and he was working relentlessly hard to repel them. Meanwhile he was also a danger at the other end, availing himself of four shots and a goal. He also made ten of Bayern's 17 clearances, suggesting his positional lapse was momentary not permanent. And I think we can forgive his role as victim in the first goal, the combination of Messi's pass with the timing of Suarez' run would beat any defense. However, Benatia's legacy from this game is likely to be negative.

And this is the wider point. The speed of the modern game has damaged the perceived reliability of the centre back. Ten years ago, defensive systems involving two defensive midfielders offered superior centre back protection. The advent of high lines, a widespread abandonment of 4-4-2 and ever more focus on attacking full backs has left the centre back more isolated. They now appear more error prone than before. Just recently, @footyintheclouds expressed surprise to me that Gary Cahill reached the PFA team of the year alongside the one genuinely solid centre back in the Premier League, John Terry, and when pressed for solid worthy alternatives, I could think of none. The centre back is less happy with his lot than he once was.

Next time your centre back struggles to keep pace with Luis Suarez or falls at the feet of Messi, it's worth remembering that their task may well be increasingly weighted against them from the start and that their qualities are being limited by systems and the evolution of the game. They are better than they might look.

Medhi Benatia sure is.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

Follow me on twitter here: @jair1970