A historic Bundesliga season is in the books. As Germany’s top-flight managed to restart the season after the coronavirus-induced break sooner than the Premier League and La Liga, it experienced how the new environment affects the game earlier than others.

The Bundesliga staged nine matchdays under unusual precautions, most notably the banning of fans from the stadiums. It quickly became clear that--at least in this league--the home-field advantage was reduced when there weren’t tens of thousands cheering the team although this development has been overstated. In total, 37 out of 82 matches (81 matches on nine regular matchdays plus one match that was postponed before the break) were won by the away side, with nine of these wins for the underdog according to the standings. For comparison, we saw only 27 wins in the 80 matches on the nine matchdays before the break, including five underdog wins.

The empty stands undeniably affected the football played on the pitch. There’s a point to be made that football is less consequential when no one – besides the coaching staff and a handful of bench players – is reacting to success and failure. Especially early after the break, several Bundesliga players were keen to show that they can escape situations with elegance instead of brute force. This resulted in pressing attacks being outmanoeuvred with dribbles and smart movements while in normal times the long hoof might have been the typical reaction from defenders that don’t possess the best feet.

But that’s just anecdotal. Let’s look at some of the numbers that indicate the various effects of the different environment in what Germans call Geisterspiele (ghost games). We compare the nine matchdays after the break with the nine before, starting on 20 December 2019.

Less intensity

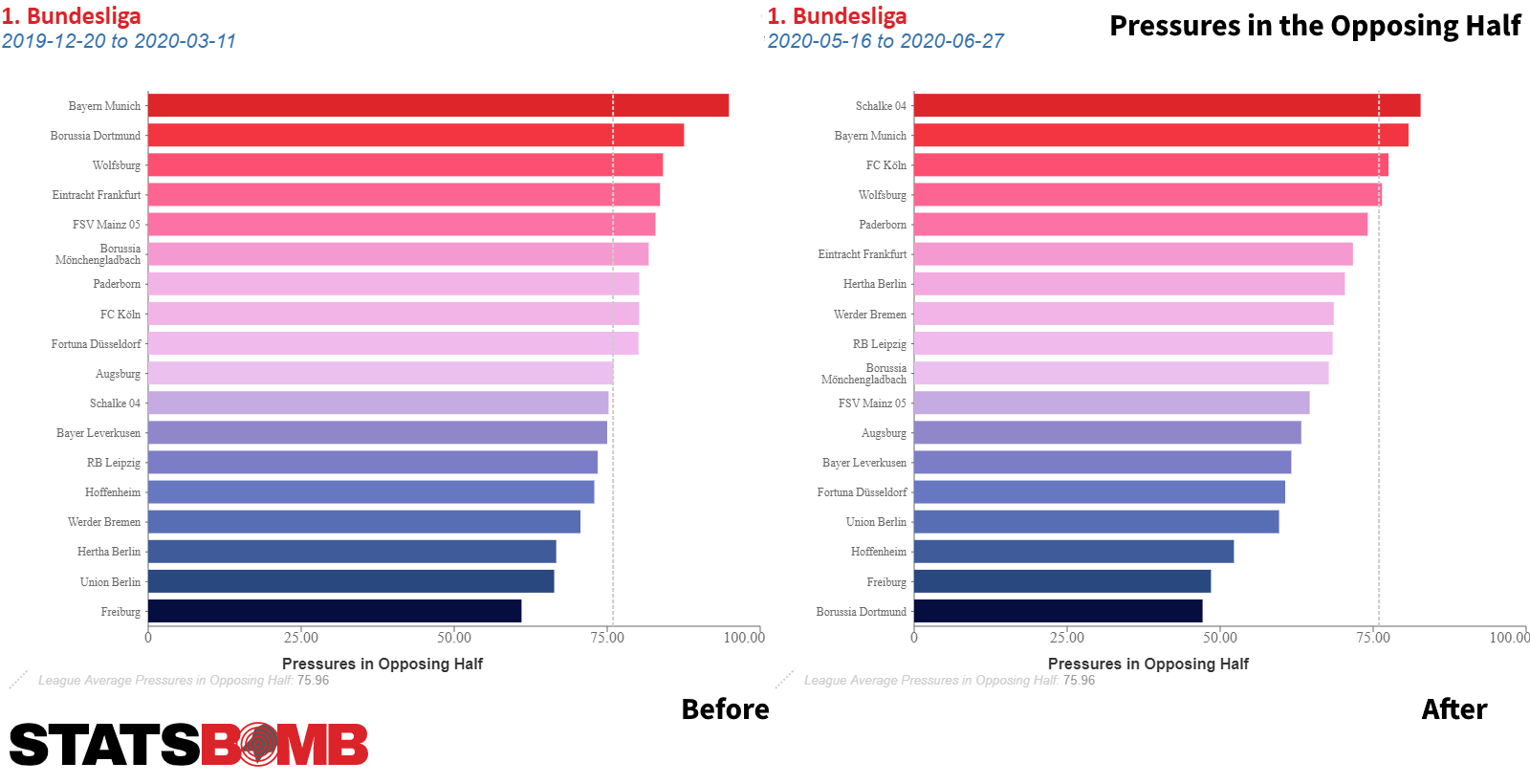

The eye test suggested early on that teams were less intense, particularly in advanced positions defending against the build-up of the opponents. The high press has been a prominent feature of Bundesliga football for several years. Centre-backs with bad feet often fell victim to this kind of style, while coaches of smaller clubs sometimes decided to abandon any kind of constructive build-up play for security concerns. While the pressures in the opposing half averaged around 77 per team per match before the break, it fell to 66 after it. This significant change certainly proves the eye test correct. What’s also striking is how many teams didn’t necessarily change their overall approach as the ranking among the Bundesliga clubs has remained largely the same, with two exceptions: Schalke, somewhat surprisingly, recorded the most pressures in the opposing half after the break which goes to show that the team did not give up in the midst of a crisis but rather were not able to capitalise on its intensity. Meanwhile, Borussia Dortmund dropped from second down to rock bottom which might give Lucien Favre’s critics some new fodder, as BVB were already third from last in this category before they lost to Mainz and Hoffenheim late in the season.

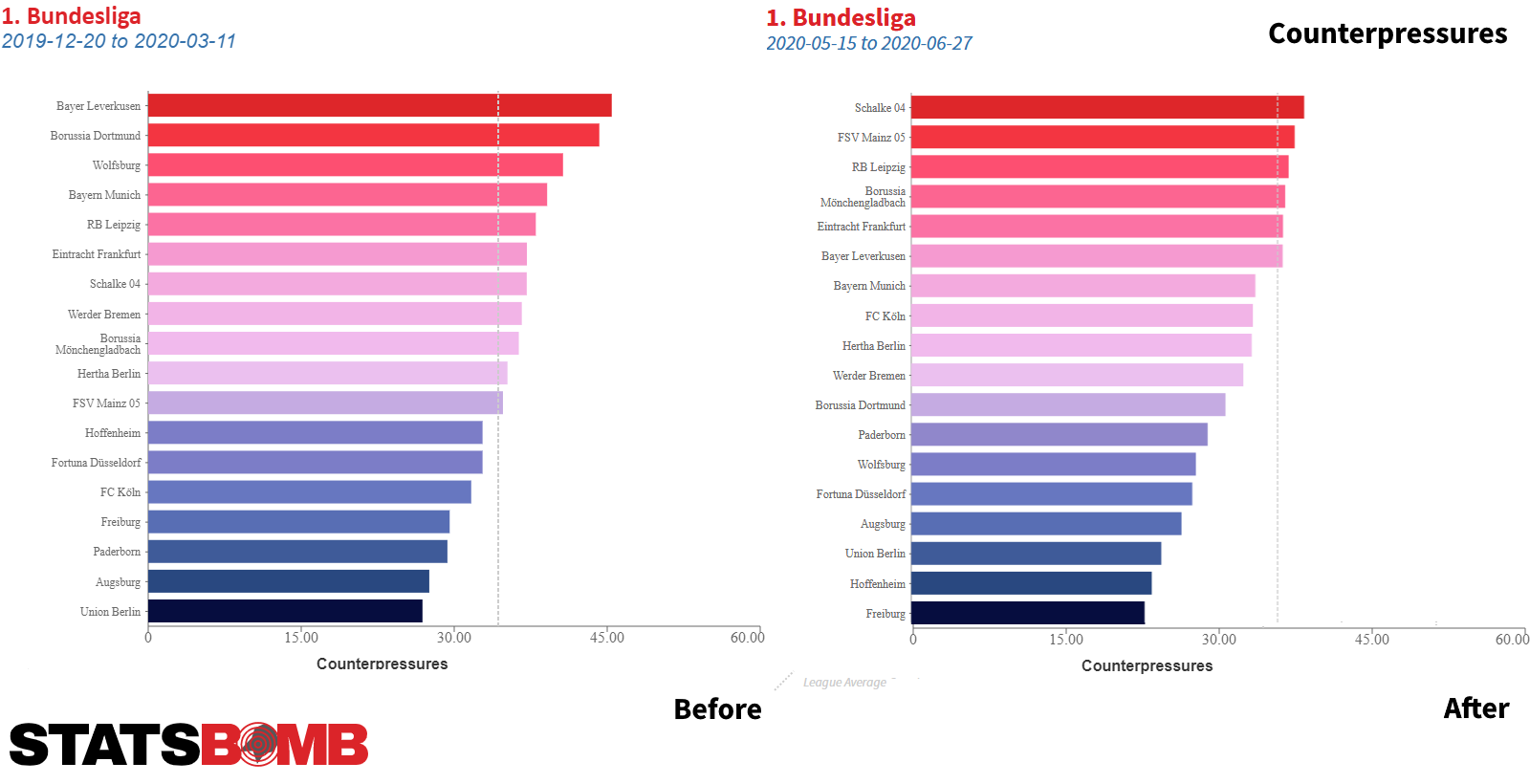

The number of counterpressures across the entire pitch also declined, falling from around 35 to 30 per team per match. Borussia Monchengladbach were outstanding in this category post-break, while Dortmund and Wolfsburg were less active immediately after turnovers.

There are a few factors that contribute to these numbers, most importantly the unparalleled circumstances during and shortly after the break. Teams were not able to train as hard as they would have liked to for a couple of weeks, because close contact between players was not allowed. Hertha’s Bruno Labbadia and a few other head coaches stated how they could not practise any kind of intense pressing or just intense actions in general which hindered plans to bring their teams into a state where they could replicate or improve the effectiveness of pressing.

Moreover, the overall fitness level was likely below par when the Bundesliga returned on 16 May, but the tracking data provided through the Bundesliga indicated that teams were only running less and made fewer sprints on the first matchday post-break, and as time moved on, the numbers quickly approached pre-Corona levels.

No tactical changes

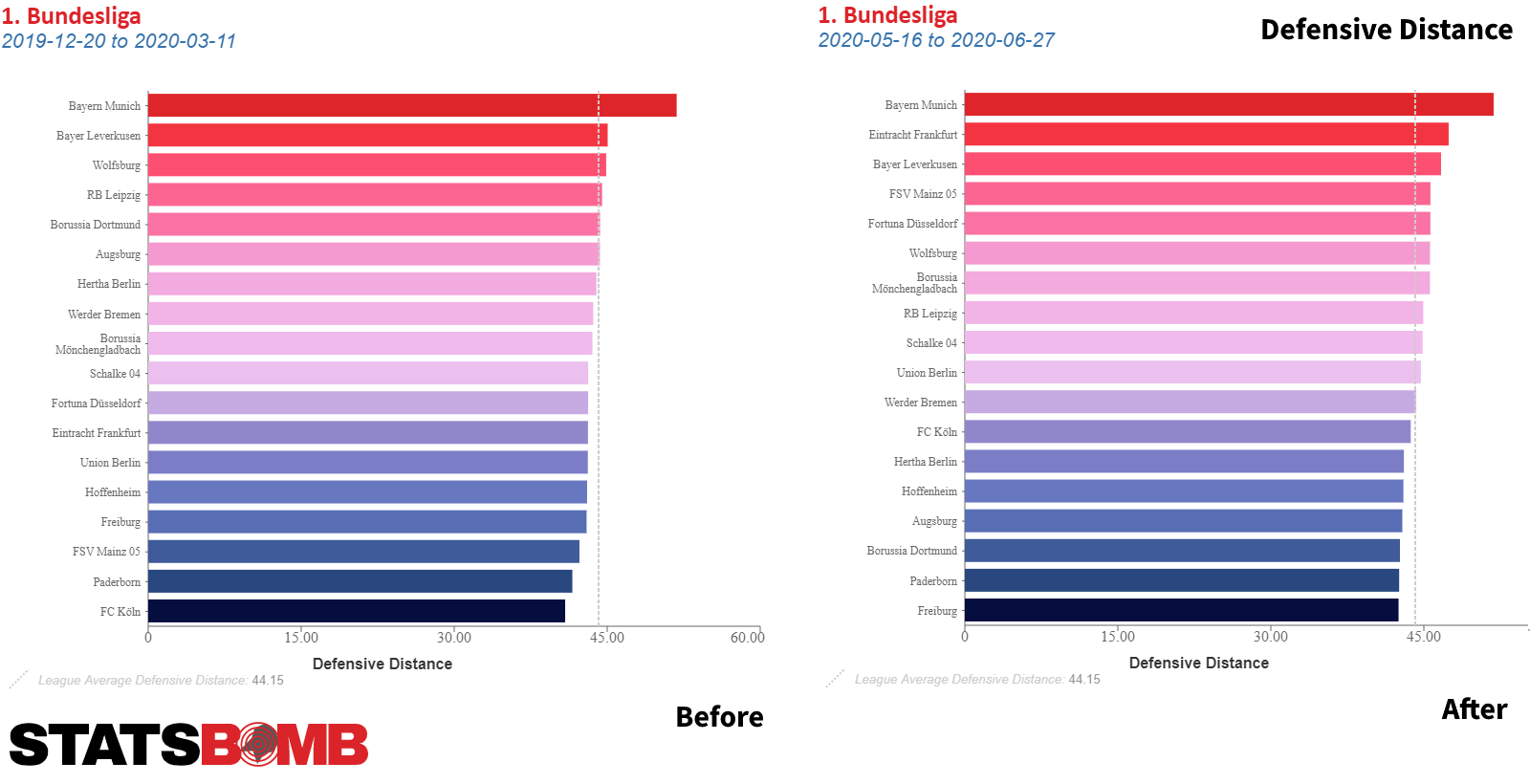

An instinctive response to these stats could be that coaches just adjusted the tactical setup of their teams to pay tribute to the circumstances. They accepted that their teams could not play such a high or even midfield press throughout the entirety of the match and instead settle for a more cautious style with a deeper back line and a more compact structure that would rely less on defensive actions and instead defend space more effectively.

However, the defensive distance, meaning the average distance from a team’s own goal from which they make defensive actions, remained almost the same, with a per-team average of 43.9 metres before and 44.9 metres after the break. It wasn't the case that suddenly a good portion of the league was sitting deep, hoping to keep opponents away from the goal. We also didn’t see a wave of tactical changes, as most coaches stuck to what they did before the break in terms of basic formations and the structures in all game phases.

Higher xG

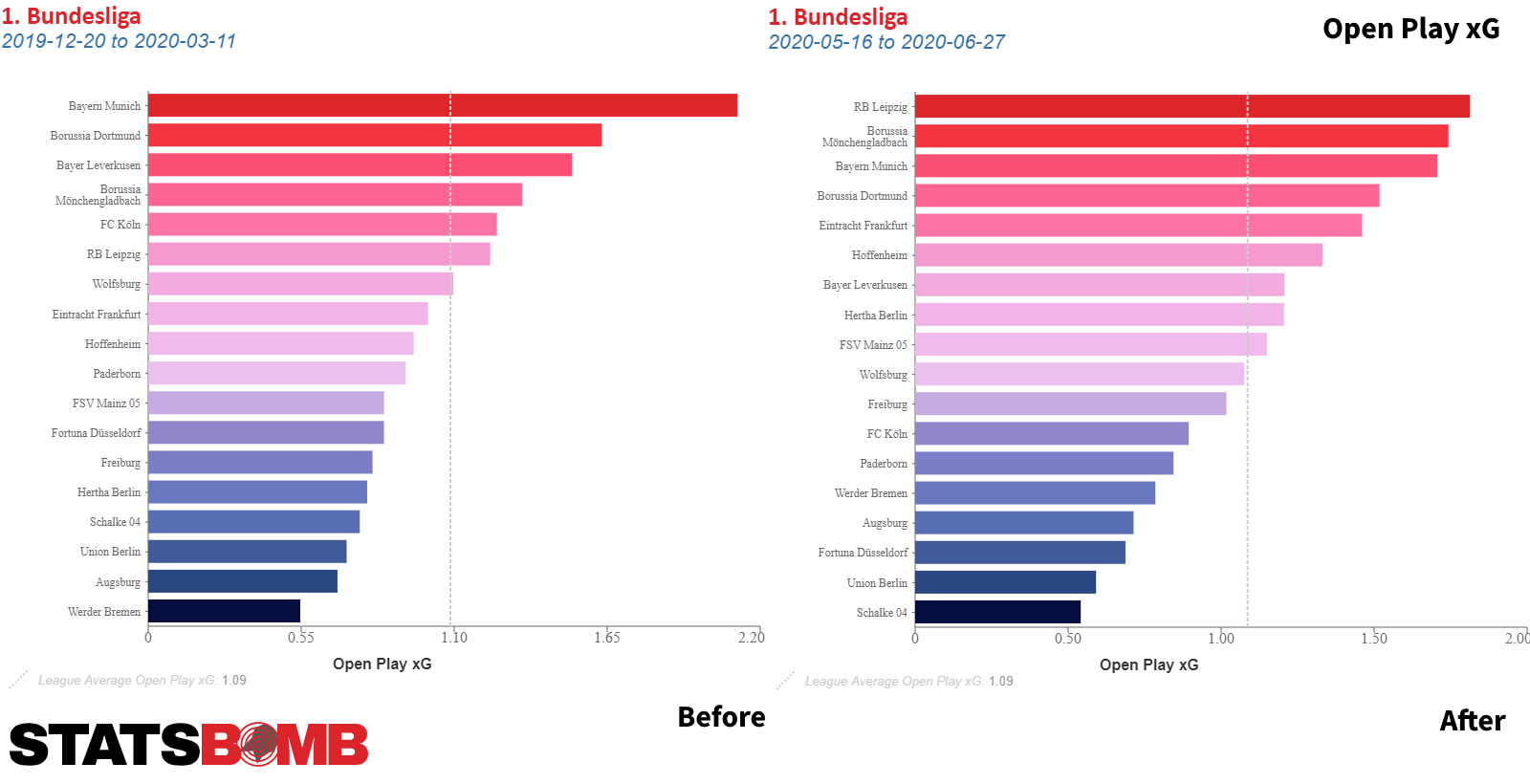

Less pressing coupled with no significant tactical changes could logically be considered to indicate a higher probability of scoring. Interestingly, on average, we saw fewer dribble attempts (17.3 compared to 18.3 per team per match) and fewer passes inside the box (2.4 compared to 2.7 before) but with a fairer distribution across the league. This indicates that it was easier for most of the teams to get close to the goal without having to rely on attacking actions that require outstanding individual skills. Instead, it was due to the declining resistance of opponents that teams were simply able to advance more easily.

The open play xG rose from an average of 1.06 to 1.13 per team per match. The average amount of shots per team per match, however, dropped from 13.12 to 12.32, with fewer shots resulting from a high press (3.0 to 2.5) and through counterattacks (1.3 to 1.1).

Overall, the attacking output did not increase, even though the decline in defensive intensity could have facilitated the output. What happened in the past few weeks was that there were fewer interactions between players, particularly in one-on-one duels, which allowed teams to play their way through defensive structures facing less resistance than usual. If the declining defensive resistance was caused from a lack of fans inspiring players to get physical, pressure opponents, and generate turnovers is just one factor in play during this period and is therefore up to debate, and a hypothesis that can perhaps never effectively be tested.