I intend in this article to squeeze one last drop of juice from the desiccated lemon that is expected goals. xG has always served strikers well. xA takes a step back and helps credit creative players that make key passes. But what of the humble pre-assist? And indeed the pre-pre-pre-assist? Do they not deserve a slice of the xG pie? By looking at possession chains, and the xG of shots that result from them, we can begin to credit players for the attacking contributions they make outside of shots and assists. It’s my hope that it can sit alongside xG and xA as a basic, straightforward metric to reveal the contributions of of players involved in the earlier stages of attacking moves, such as deep lying playmakers, or creative centre-backs. We originally created this metric as a placeholder for our expected possession value model, giving us a simple way to highlight attacking contributions in our pass maps. But in the end we liked the numbers and thought it was straightforward enough that it was worth making public in and of itself.

Calculating xGC

Ted has already dubbed this xGChain, because it’s got xG and possession chains in it. I originally called in ‘xG involvement’ or ‘xG contribution’ because I’m boring. From hereon in I will refer to it as ‘xGC’, perhaps you can come up with a better name. Whatever you call it, it’s dead simple:

- Find all the possessions each player is involved in.

- Find all the shots within those possessions.

- Sum their xG (you might take the highest xG per possession, or you might treat the shots as dependent events, whatever floats your boat).

- Assign that sum to each player, however involved they were.

Any on the ball action will do, we’re not fussed, whether you make the first pass in a 30-pass buildup, or take the final shot yourself, you’re getting just as much credit as anyone else in that move.

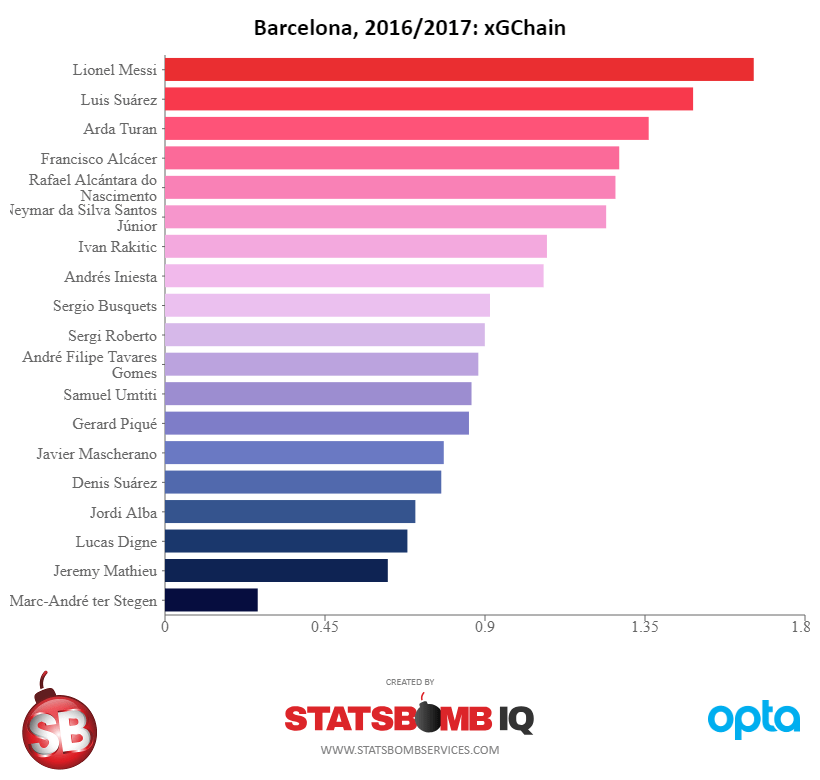

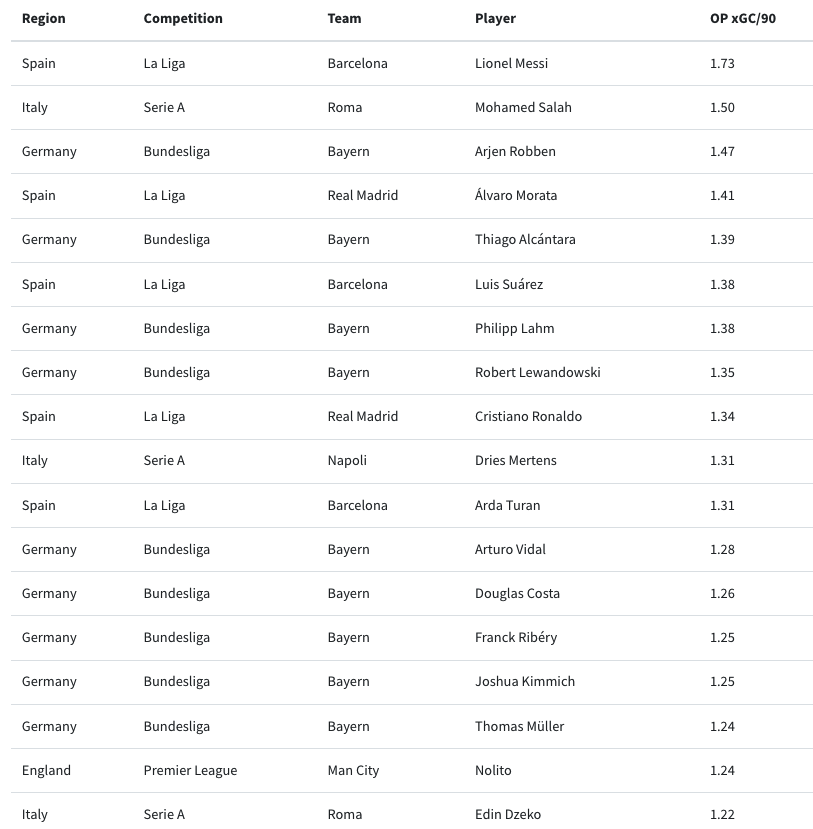

Top 20 by xGC/90

Taking a player’s xGC for a season and per-ninetifying it yields their xGC/90. Usually the players that will stand out in xGC/90 are going to be strikers, or those assisting them – they’re more likely to be involved in moves that lead to shots, after all. But it still gives you a slightly more holistic view of attacking contribution than arbitrarily cutting off at shots and assists. Here’s the top 20 in 16/17 with 600+ minutes:

These are pretty much the usual suspects, but you’ll note that we’re picking up players like Philipp Lahm, heavily involved in buildup play but not necessarily known for goals and assists.

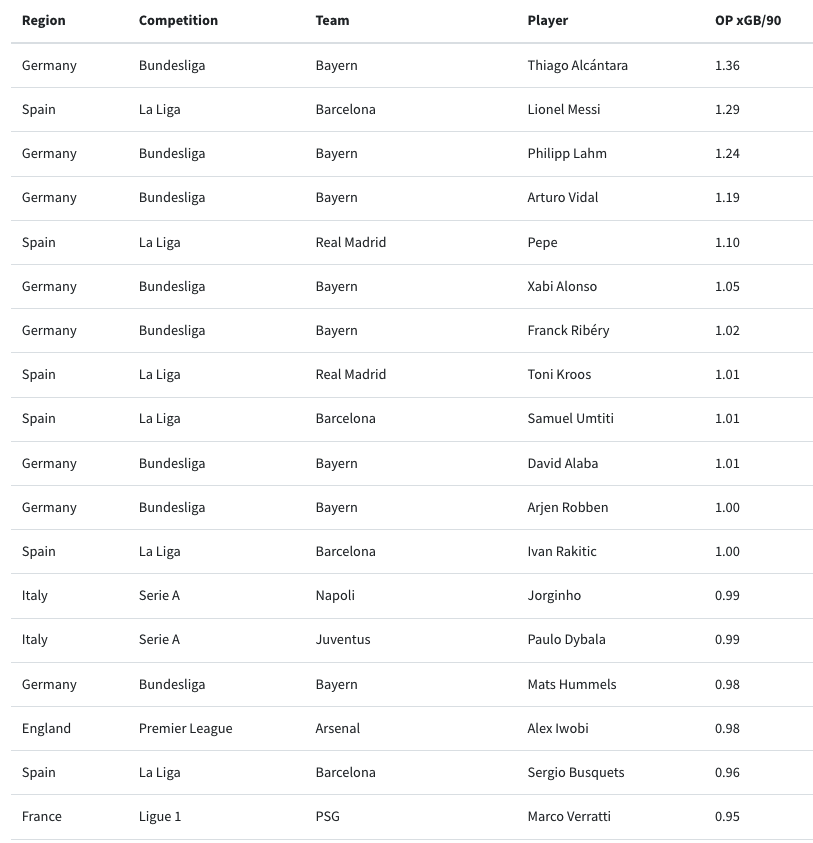

Top 20 by xGBuildup/90

You’ll note, however, that for a lot of players, the values are still dominated by xG from shots and xA from assists. You get a little extra credit for your buildup play, and some unexpected players are still able to shine through. But the fun starts when exclude shots and assists from the possession chains, so we can concentrate just on buildup play. It’s okay if you ultimately make the assist or shot yourself, but you also have to be involved in the earlier parts of the move to get credit. I originally called this pre-xGC (pre as in pre-assist, you see), but the world knows it now as xGBuildup and it yields quite a fun list this season:

Messi still appears because he’s a freak, but we’ve also got a motley crew of midfielders and defenders, many of whose contributions to attacking play are easily lost when looking at mere xG and xA (or indeed raw goals and assists).

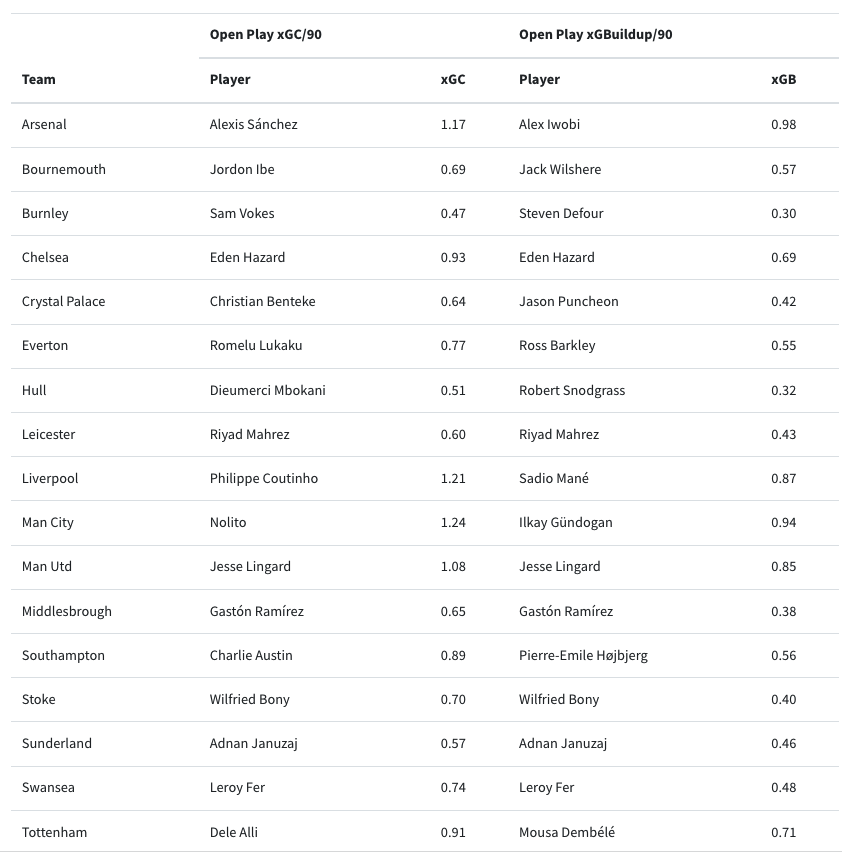

EPL Team Highlights

To get a feel for the metric, here’s the top players by xGC and xGBuildup for each EPL team this season (16-17):

Again we’re surfacing players like Dembélé who are often integral to buildup play, but don’t get much credit in the public attacking metrics beyond passing completion stats.

Team Balance

Now that we have a rough metric for attacking contribution, one thing we can do is look at teams that are more or less balanced. There is some indication that teams that are more balanced are more successful than those overly-reliant on a few players.

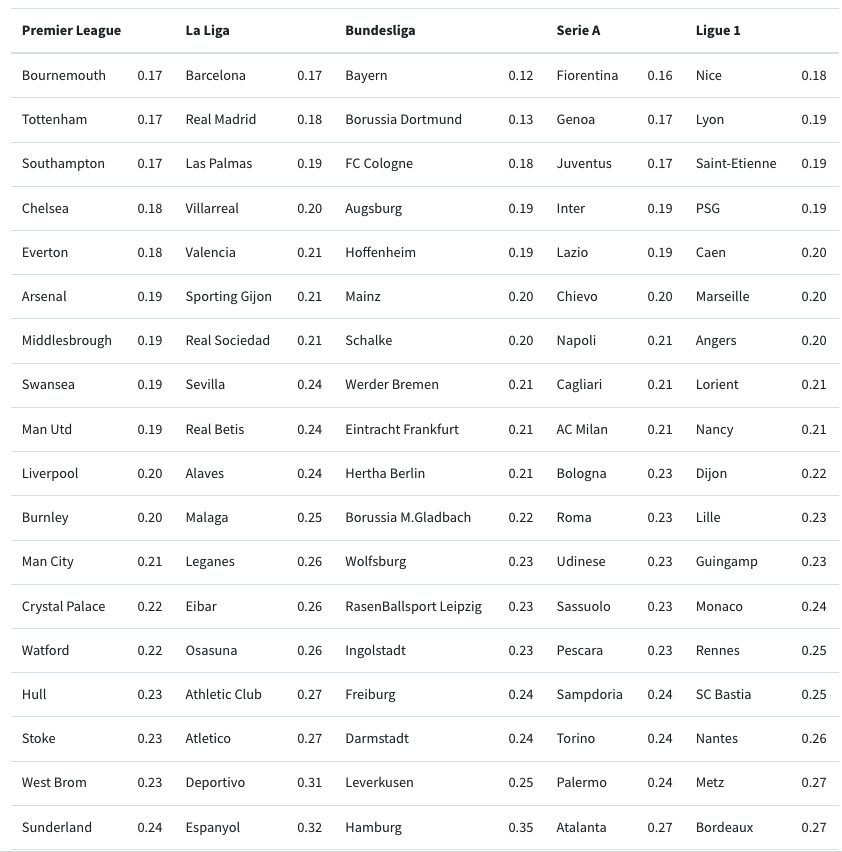

To look into this, I’ve calculated Gini coefficients for teams over their open play xGC/90 values, for players with 600+ mins. The higher the value, the more imbalanced their attacking contributions – a value of 1.0 would mean a team generates all its xG through one player, acting completely alone, a value of 0.0 would mean a team involving all of its players in every attack (for the exact same number of minutes).

West Ham’s 3-0 win over Crystal Palace may have eased fears they’re a one man team, with Dmitri Payet trying to force a move away. But they are still more reliant on a few key players than any other team in the EPL. Mark Noble and Michael Antonio are the other two players taking up the bulk of attacking responsibility, and time will tell if the rest of the squad can step up. Leverkusen are another unbalanced team facing some risks with Julian Brandt and Chicarito likely to move on soon.

These numbers don’t necessarily tell us a lot about underlying performance – Leicester won the league with a coefficient of 0.28, and RB Leipzig are having a huge impact in the Bundesliga despite being bottom half for their offensive balance. But for squad planning purposes, this can act as an early warning system if your team is overly-reliant on a few players in attack.

Conclusion

xGChain is a simple, flexible metric that exposes aspects of attacking play omitted by existing metrics. It’s not a replacement for a proper non-shots model, and it shouldn’t be read as a composite rating for a player’s attacking skill – it’s an evolutionary step that builds on existing models. In the coming days we’ll show some of the useful stuff we’ve built on top of it, including our new xGC-based pass maps, as well as highlighting some of the more interesting players and games we’ve found in the numbers.