In the 2023/24 Premier League season, there were an average of ∼35 throw-ins per game. Roughly 25% of them were in the throwing team’s defensive third, and the remaining 75% were more or less evenly shared between middle and attacking thirds.

Although these numbers naturally fluctuate slightly depending on the competition and season that you consider, few fall outside the 35-45 per game range.

That’s around 20 throw-ins per team, per game. In a sport riddled with randomness and chaos, throw-ins (like all set pieces) are a chance to wrestle back some control, once every 5 minutes, on average.

If I haven’t lost you already, don’t worry, this isn’t another StatsBomb piece professing the merits of set pieces. Those who’ve tread these boards before me have already done that job - and somewhat influentially, I may add. Instead I strive to give some insight into how you can measure the different effects of throw-ins, and how you can use that information in next opposition and own-team analysis - and perhaps more pertinently, what success actually is when it comes to throw-ins.

What is success?

Let’s start with that final point. Before we can begin to measure success, we first have to define success. Not every team wishes to create a direct threat from their throw-ins. Some will put a greater emphasis on retaining possession. Others, particularly for throws originating in their own half, may primarily want to regain some territory. Perhaps a switch-of-play is your primary objective, or maybe you want to move the ball into the half space areas.

Success is subjective in most contexts -- in relation to throw-ins, I think it is particularly so. Perhaps that’s why they are often treated with such relative contempt in football.

In this article we will look at a variety of ideas and methods for how you can measure the success and effectiveness of throw-ins. We’ll look at xG, OBV, the ability to retain possession and also finding space to receive the ball, and we’ll analyse both team and player traits within these frameworks.

xG per Throw

Using xG is a common and logical measure of throw-in success. And I’m not here to knock its merits. But it can be skewed by one or two events (especially when sample sizes are smaller), and also relies on a complimentary skill of ‘getting a shot off’ - you can do a lot of good work from your throw-in, but if there is no shot at the end of it, then you’re not getting any credit here.

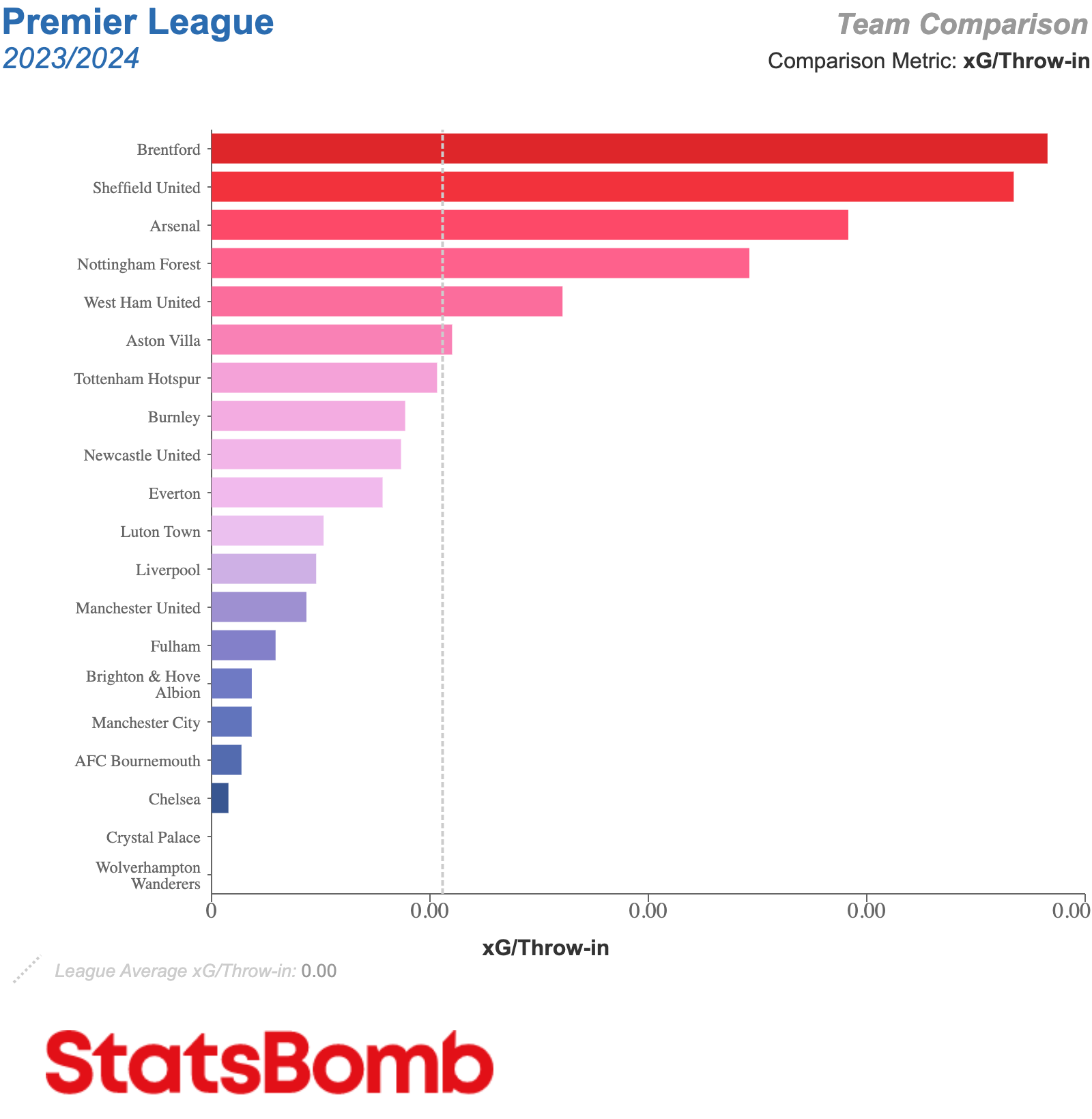

The below highlights Brentford and Sheffield United as being the most threatening in the 2023/24 Premier League, in terms of xG created from passages of play following a throw-in, and also shows Wolves, Palace and Chelsea as teams creating next to nothing.

If your primary goal is to directly create chances from throw-ins, then you may well be happy with this as your measure of success. In which case, thanks for reading….

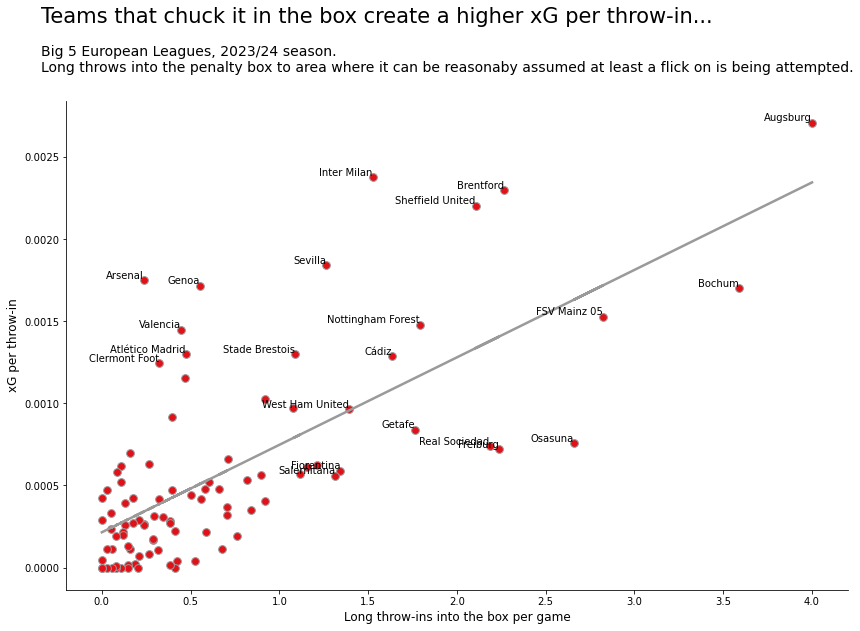

However, there’s also an unnerving trend of xG being linked to the ability and accompanied willingness to chuck it into the mixer.

Obviously if you have the tools at your disposal then there’s no shame in getting the ball directly into the most dangerous of danger zones - in fact if you’re not doing so then the above tentatively suggests you’re actively leaving something on the table. But if you don’t have that skill set at your disposal, it doesn’t mean you’re objectively bad at throw-ins. There is also an artistic element to maximising the effectiveness of these restarts, so decoupling from the rawness of being able to throw the ball far has some value.

To that point, interesting here are the likes of Arsenal, Genoa, Valencia and other named teams in that left side area, who are each in the upper quartile of teams by xG per throw-in, but relatively rarely execute long throws into the heart of the penalty box.

OBV

In order to remove the requirement to generate a shot within the throw-in phase of play (i.e. an xG value) to achieve some recognition, we can instead look at On-Ball Value (OBV).

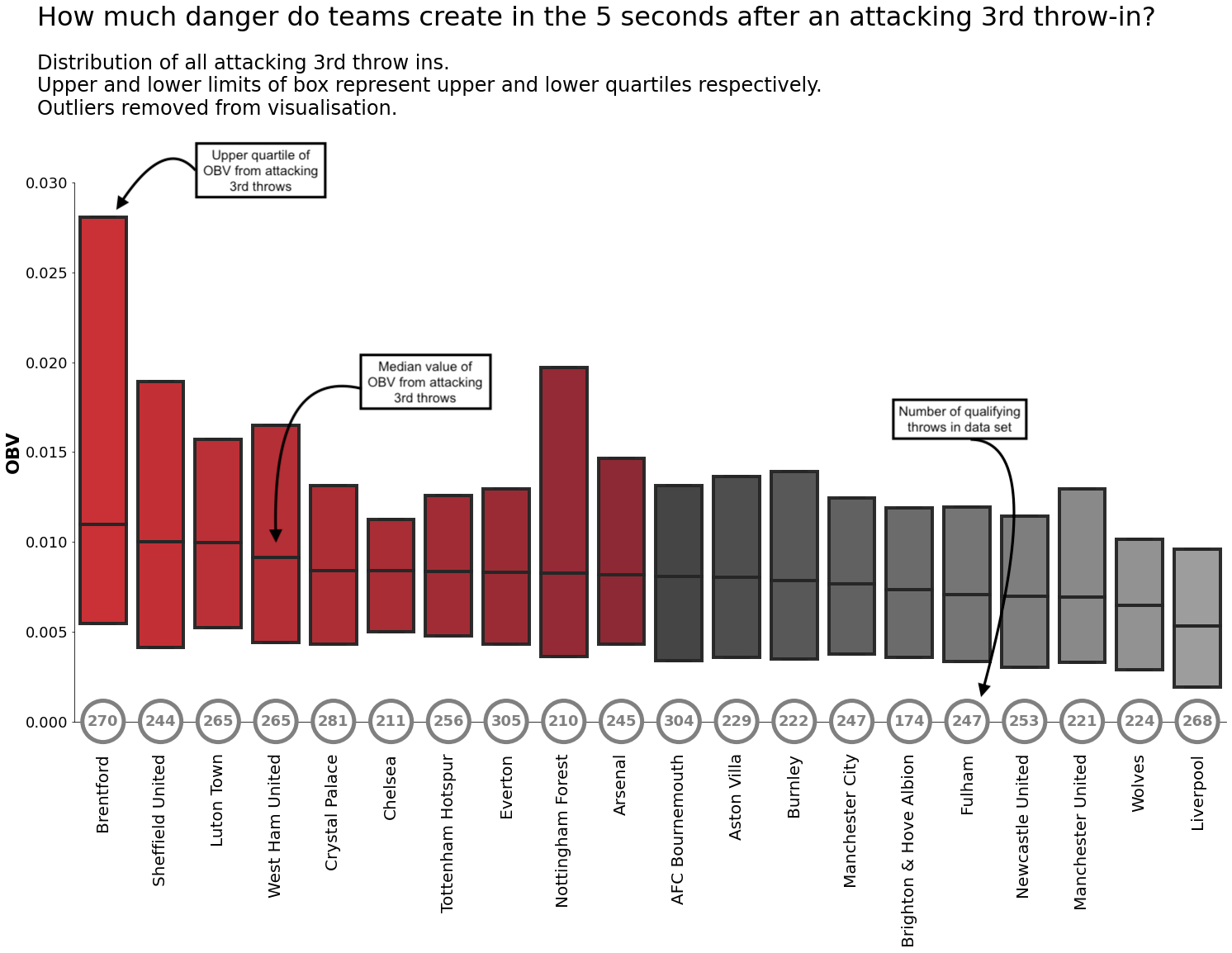

There are numerous ways to approach this, but my chosen method is to calculate the difference between the OBV value of the throw-in and the highest OBV end state of any action in the subsequent 5-seconds.

By doing this, we capture the biggest increase in your chance of scoring within the subsequent passage of play, even if you subsequently regress into a less threatening state, and we’re also not discounting scenarios where a team may momentarily lose possession then regain it. Admittedly, the 5-second timeframe is slightly arbitrary, but it falls in line with the measurement used for metrics such as Pressure Regains and High Press Shots, and it feels like a fairly reasonable cut off for when any team’s advantage (or disadvantage) from a throw-in set up might have ended. Furthermore, after looking at a few leagues and adjusting the cut-off by 2-3 seconds either side, the differences in rankings were arbitrary. 5 seconds it is.

The results below are ordered by the median OBV value of all attacking 3rd throw-ins, and the top and bottom of the bars represent upper and lower quartiles. Numbers inside the circle are a count of the number of throws being considered.

Brentford and Sheffield United still come out on top, as they do with xG - and this is likely still somewhat weighted to the long-throw into the box traits - but there’s also a clear top-heavy nature to Brentford’s distribution that suggests there’s something a little more going on there. Nottingham Forest are an interesting case too - overall they‘re middle of the pack, but they clearly possess a threat when things click.

Luton, Palace and Chelsea also feature much more prominently here than they do on the xG measure; is there a disconnect between moving the ball into dangerous areas, but not getting a shot on goal?

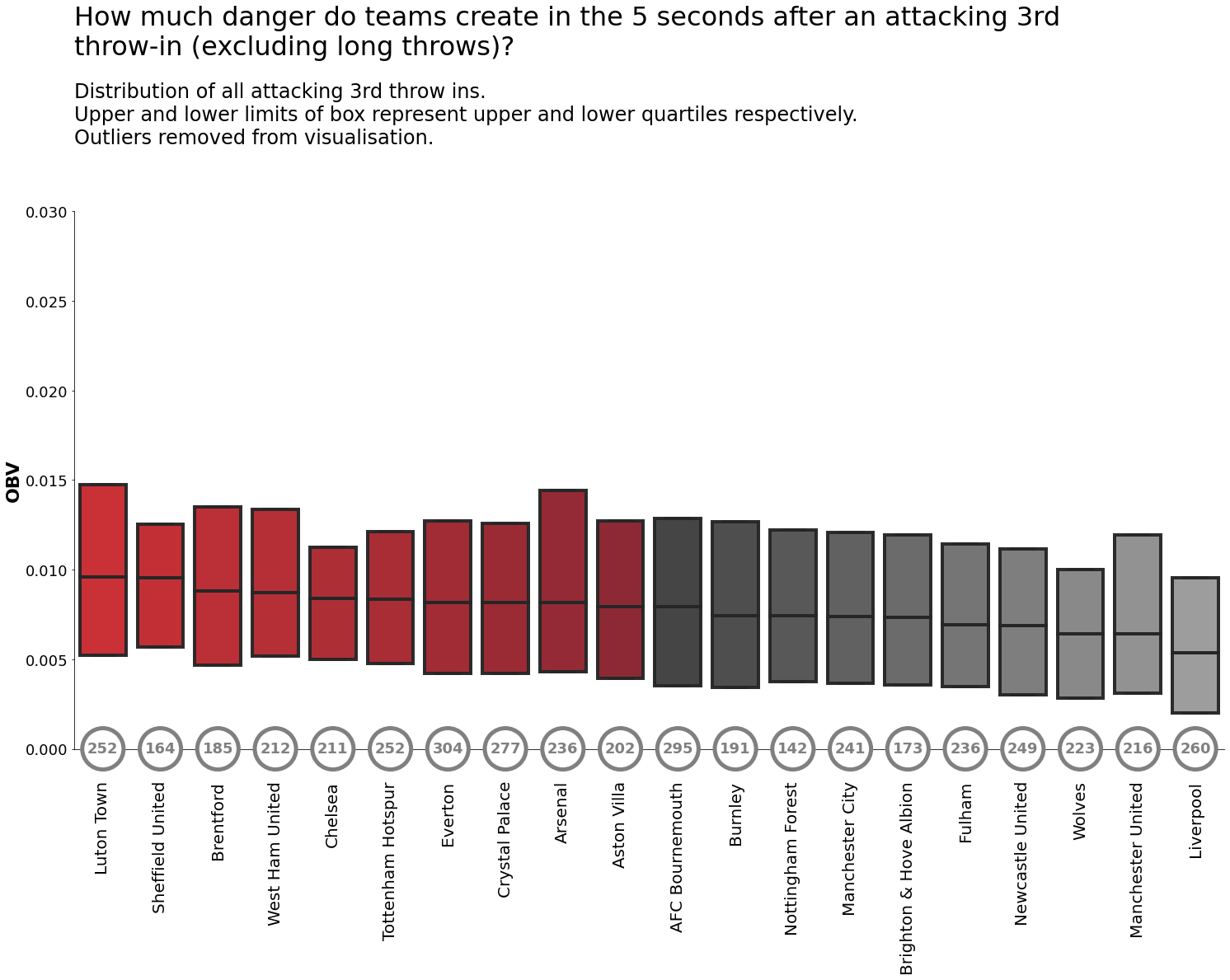

And then high-possession (and generally stronger) teams in the league like Liverpool, Man City and Brighton are each struggling to make an impact on this metric. This point stands even when you remove long throws from the equation.

Although the differences are less pronounced here, let’s acknowledge that both Sheffield United and Brentford are not simply long-throw merchants. And yet another tip of the hat to Luton and Crystal Palace - further analysis would be required, but there’s an inclination that they may be creating crosses into the box shortly after throws, and that is generating the higher OBV values.

Possession length

It would be remiss to suggest that because Liverpool, Man City and Brighton don’t rank well for xG or OBV from throw-ins that they are objectively bad in this area - you don’t gain the reputation of Jurgen Klopp or Pep Guardiola by leaving something on the table - so they must be doing something else.

And sure enough, that shakes out in the observations of how long teams retain possession for after an attacking throw-in. City, Liverpool and Brighton make up the top 3 for median time of possession retained from attacking 3rd throws.

Of course we need to consider the overall ability of these groups of players to retain possession and can’t attribute a significant part of these results to what they do at the point of the throw-in (which is why I won’t dwell on these results for too long), but there is some evidence here that these teams put a greater emphasis on retaining control of the ball than creating a direct threat from restarts, and it at least partly explains why they don’t feature prominently in OBV and xG calculations.

Into the mixer

Circling back around to look at those throw-ins that go long and into the heart of the penalty box…

First of all, it’s obviously worth noting that just because you can do something, doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to do it all the time. But there’s a clear and strong trend of teams that can throw it further, putting it into the mixer more often.

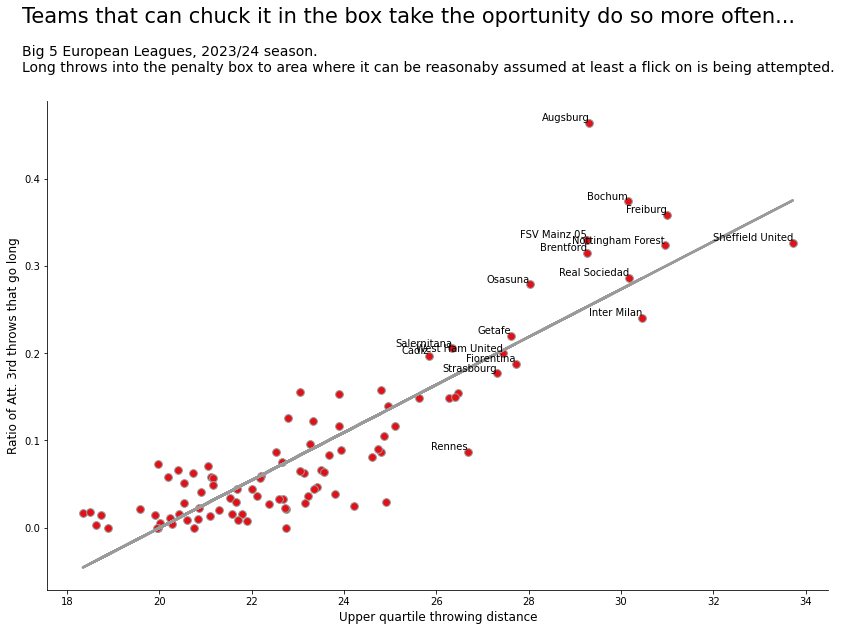

The below compares the ratio of attacking 3rd throw-ins that are chucked long and into the heart of the penalty box, compared to the (upper quartile) distance of their throws.

Note, I’ve chosen to use the upper quartile of measurement for distance as a proxy for how far a team can throw the ball rather than the maximum distance. This is because the maximum tends to throw up a few anomalies where everyone misses the ball and the distance is then recorded as the point where the first touch occurs, or the ball goes out of play. Also, if a team has a long thrower in their team, but never uses him in that respect, then it’s also not picked up here.

Augsburg out there really trying to maximise their long-throw assets, choosing to throw it into the box for almost 50% of their attacking 3rd throws. Rennes, on the other hand, perhaps not making the most of their capacity to launch the ball from the sidelines.

Winning first contacts

Throwing the ball into the box tends to naturally generate some chaos and opportunities will come on occasion regardless of who wins the first contact. However, it’s reasonable to assume that winning the first touch - whether that be a flick on, a direct shot, or something else - is desirable, in so much that it can help you to direct the chaos.

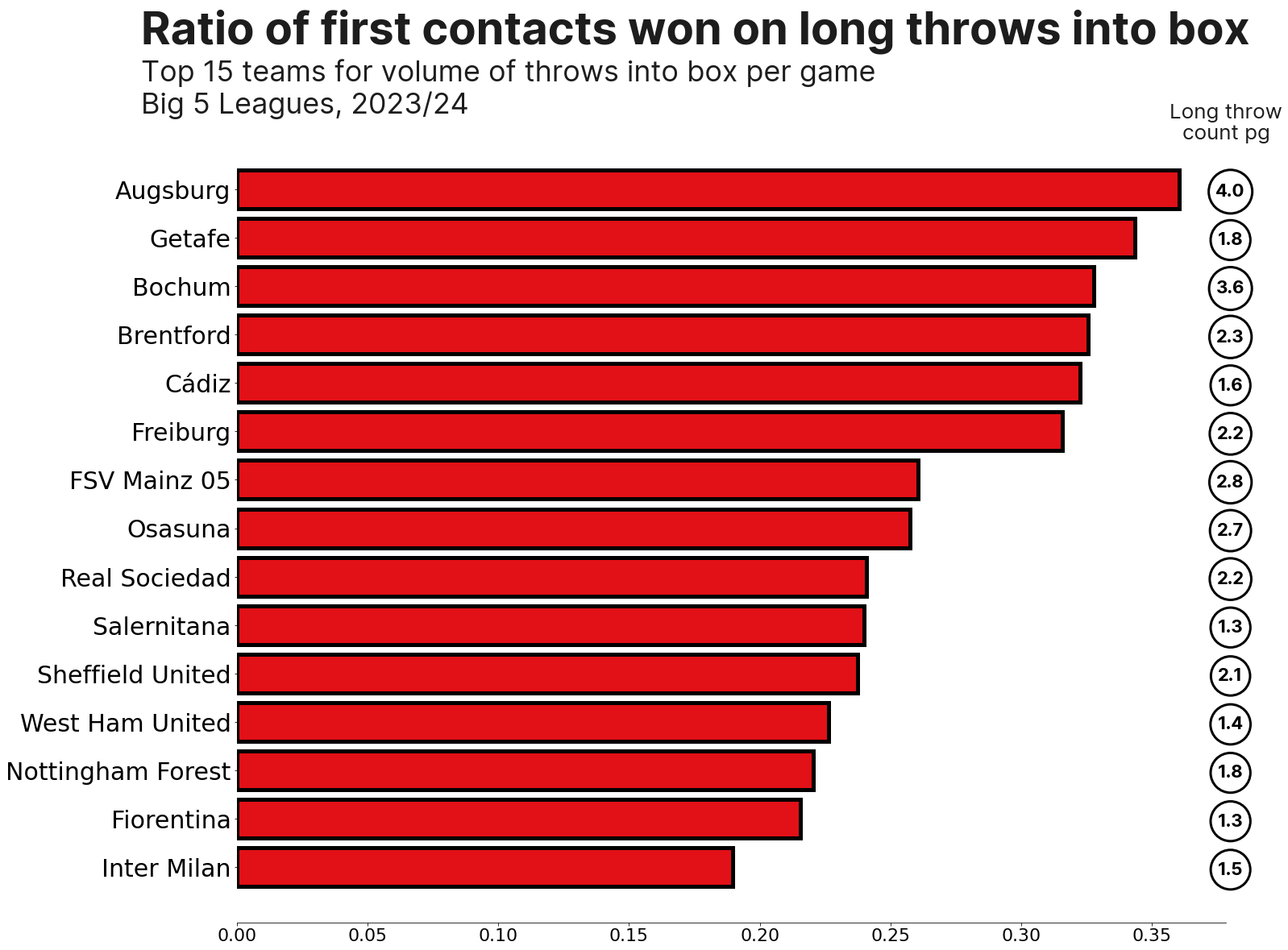

So, of those that throw the ball into the box most often, who wins the first contact most often?

Augsburg and Bochum are interesting, stand-out cases here - they regularly throw it into the box AND are very good at winning first contacts. Brentford’s proficiency for winning first contacts is also telling and undoubtedly linked to their reputation of being a potent threat from attacking throw-ins.

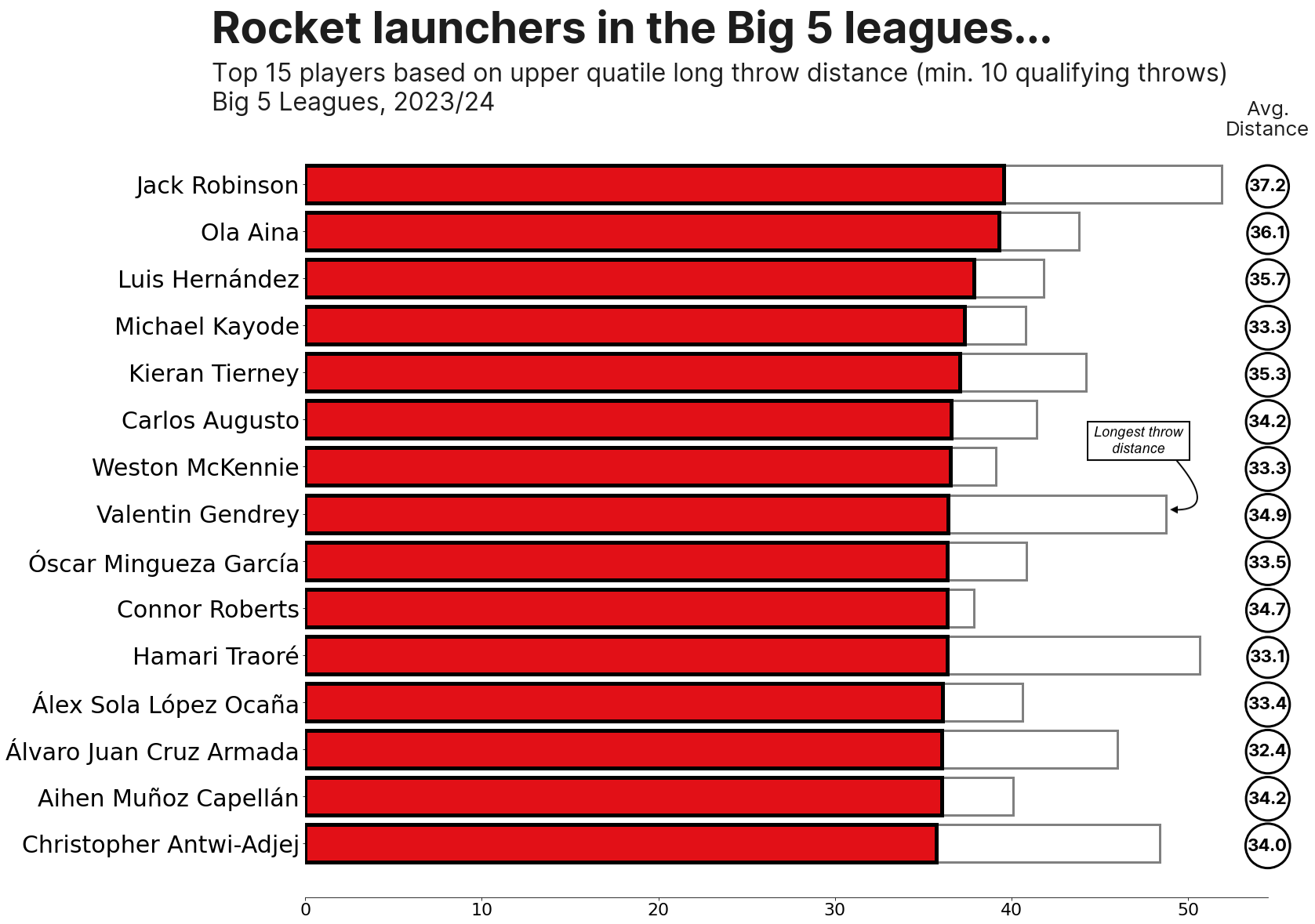

And for the final word on the big throws into the box, a quick look at who the rocket launchers of these so-called hand-corners are. For the same reasons outlined above, I’ve focussed on the upper quartile distances of long throws (short throws are discounted here), but I’ve also added in the distance of the longest throw from each individual because… well, err, it’s fun to see.

Sheffield United’s Jack Robinson and Nottingham Forest’s Ola Aina lead the way, with Robinson’s numbers for both longest and average also looking particularly strong.

Kieran Tierney’s position on the list proposes a motion that throwing the ball far is not all about brawn, and there’s a suggestion that Fiorentina, Inter and Lecce should be making more of their respective assets in Michael Kayode (17 throws), Carlos Augusto (12) and Valentin Gendrey (17), who each only unveil their hand-corners relatively few times.

Creating Space

When it comes to throw-ins, the inverse of launching it into the box is the shorter, more accurate throw. If you chose to take this type of throw in then you’re mainly going to be looking for one of two things; either a ball recipient that is strong and physical enough to hold off opponents, or a ball recipient in space. The latter tends to require either reacting quickly to the scenario or some sort of emphasis on off-the-ball movement, and, perish the thought, potentially even a co-ordinated throw-in routine or two.

Event data can’t identify the off-ball movement that leads to a player being found in space, but it’s not unreasonable to assume that teams who are regularly finding teammates in space, may be doing something deliberate to generate that space - a pointer towards analysing video in more detail.

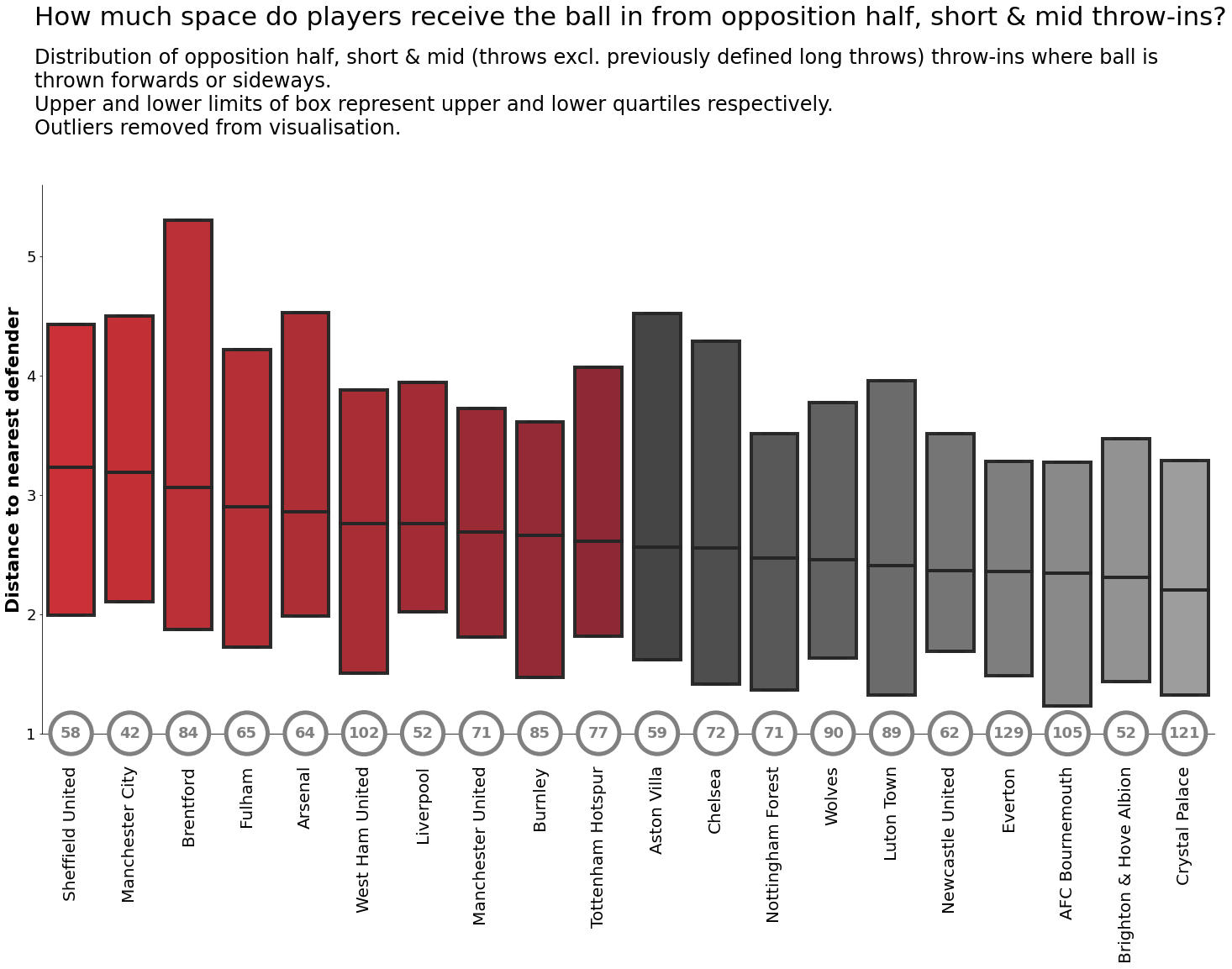

The below looks at the distribution of space that the ball recipient is found in when receiving the ball from short- or mid-length throw-ins (effectively anything that isn’t included in the previously defined long-throws) taken in the opposition half, but also excludes any throws that are backwards - my theory here being that when throwing the ball backwards, you’re often given the space to receive by the opposition, and I’m not particularly interested in measuring this.

Notable here is that both Sheffield United and Brentford feature prominently. Perhaps this is partly a consequence of opponents being wary of the long-throw threat, packing the box more than they would normally, and the throwing team then taking advantage of space that has been allowed. In addition, Brentford again have a high upper range, which further enhances their reputation as throw-in innovators (throw-innovators? - sorry).

At the opposite end of the scale Brighton are an interesting case; we’ve already seen that they create very little xG or OBV (in the subsequent 5 seconds) from throw-ins, and although we’ve seen they are capable of retaining possession, this does tie in with Roberto de Zerbi’s known indifference to training set pieces.

Now that we know which teams create the most space, how about looking at where they create that space?

Interestingly, both Manchester City and Arsenal create a lot of their space in the corners of the pitch - given their all-round team qualities, perhaps opponents are willing to give them space in these areas in exchange for keeping it tight in more threatening zones.

Brentford and Fulham are notably more adept at creating space to receive the ball down the right side, while Sheffield United’s space tends to come deeper - backing up our theory that this is a response to opponents being somewhat wary of the long-throw threat that they possess.

Finally, let’s have a quick glance at the players within teams that are adept at finding space to receive the ball.

Note Mbuemo’s ability to regularly find larger pockets of space that ties in with Brentford’s right-side proficiency. Gustavo Hamer stands out as the Sheffield United midfielder that is the one regularly finding the mid-range pockets of space in the midfield area. And a nod to Will Hughes who has a big upside on his range of space, despite playing in a Crystal Palace side that has the lowest median when measured by team.

In Conclusion

Throw-ins are rarely sexy, in fact they’re undoubtedly the ugly sister of the set-piece family - yes, even goal kicks are more glamorous these days. But it’s for that reason that there is an edge to exploit if teams opt to do so.

Without the context of knowing what the aim is, it’s difficult to explicitly say that any one team is best in class at something as nuanced as throw-ins. However, it’s fairly evident that Brentford are doing something over and above what others are in the Premier League when it comes to their attacking throw-ins. And that Arsenal adopt a more varied approach than their peers at the top end of the table.

All that said, the above is not an attempt to highlight one particular team or method. Instead I hope it serves as some sort of pointer to the myriad of ways in which you can measure and analyse not just throw-ins, but any of the finer details of the game.

Of course everything that happens on a football pitch should ultimately be an attempt to increase your chance creation metrics, or suppress those of the opposition, but how you get to those end goals is a matter of choice. And I’m a big believer that in sport, anything that you choose to do should be monitored, analysed and measured, where possible.