The Premier League has transformed from a very good football league into one of the world’s greatest soap operas, and perhaps my favorite storyline right now is the struggle of Pep Guardiola.

- Take the world’s greatest current manager.

- Add him to one of the world’s richest teams.

- Profit.

Before the season, most people thought it would be that simple. Halfway through the year, it is clear it has been anything but. The question is why? Pep didn’t struggle like this at Barcelona, nor at Bayern Munich. What makes Manchester City – just two seasons removed from the title when he took over – so much harder? For the answer to this question, I want to briefly cast back to some stuff written at the start of StatsBomb’s existence in 2013 by myself and Benjamin Pugsley. That summer City recruited Fernandinho, Jesus Navas, Stevan Jovetic, and Alvaro Negredo at the top end of the scale, aged 28, 27, 23, and 27 respectively. The problem we flagged up at the time was that these were clearly “win now” transfers that would have a stonking replacement cost down the road. You can’t sign guys in their late 20s and expect them to contribute at the same level as players in their prime at the end of 4- and 5-year contracts. It just doesn’t happen. Add in 32-year-old Martin DeMichelis for salt and City had signed fairly old. The next summer saw the arrival of Mangala, Fernando, Willy Caballero, and Bacary Sagna. Now Mangala was 23, but ended up being a disaster. This happens, especially with center backs. Fernando was 26 and has hardly contributed at a level commensurate with his fee. Caballero is a backup GK, and Arsenal fans will tell you that as much as they loved Sagna, he was already approaching washed up as a two-way fullback when City signed him at age 31. In his last season in North London, you could have Sagna attack. Or you could have him defend. Do not expect both. Two years, lots of fees, and no players in their prime that stuck. This is a problem for a club that wants to contend for titles every year. Last summer, City spent about £150M on Sterling, De Bruyne, and Otamendi to start digging out of the mess, and all three have proven to be good/great additions. Unfortunately, this equates to “normal” turnover spending for a super club. It didn’t improve the spine much, nor solve the growing geriatric issue. Fast forward to this summer, and the great master arrives along with John Stones, Leroy Sane, Nolito, Gundogan, and Claudio Bravo. Nolito and Bravo are 29 and 33, and neither one of them is a fullback. Gundogan is a world class talent and midfielding brain packed into a Mr. Glass body. Sane provides good depth and youth, but probably a year away from being good, and John Stones is a center back project that Pep desperately needs to succeed. The point of all this is that yes, Pep’s system might be the most fundamentally superior tactical system we have seen in modern football. And yes, Pep Guardiola is still a goddamned Footballing Jesus. But even Jesus was going to have a tough time resurrecting this squad and romping the league this season because of the issues created by years of ineffective squad planning before he ever got there. And all of that was before the entire league chose to collectively get their shit together on the manager front, giving the Premier League probably the greatest collection of coaching talent it has ever had at one time. City might have the best manager in England, but they could spend £200M in January and still need to stump up more in the summer in order to have the best squad in the league. It is great to see Guardiola struggle, and try to adjust his tactics to both the league and his squad at the same time. That very struggle has not only created a great story for this season, but it’s also enhanced the reputation of the Premier League by proving to be a tougher title to take than anything Pep has faced in recent times. Young Rash and Tam Tam I was asked this week on Twitter whether I would pick Marcus Rashford or Tammy Abraham as the bigger talent. This came out of a broader discussion on what “the analytics world” thought of Rashford this summer, after a fiery debut season. My point then bears repeating: there is no such thing as “the analytics world.” There is no monolith of opinion with regard to stats and football. There is a loosely-connected community of people who work with stats, but that’s about it. The site you are reading this on right now is not called TedBomb, and even here on StatsBomb you will see differing opinions and analysis of the exact same data by different writers. Lumping all analysts into a group sells the great work everyone does short in the same way lumping all journalists into one misguided, monolithic opinion group would. We are all unique snowflakes, dahling.

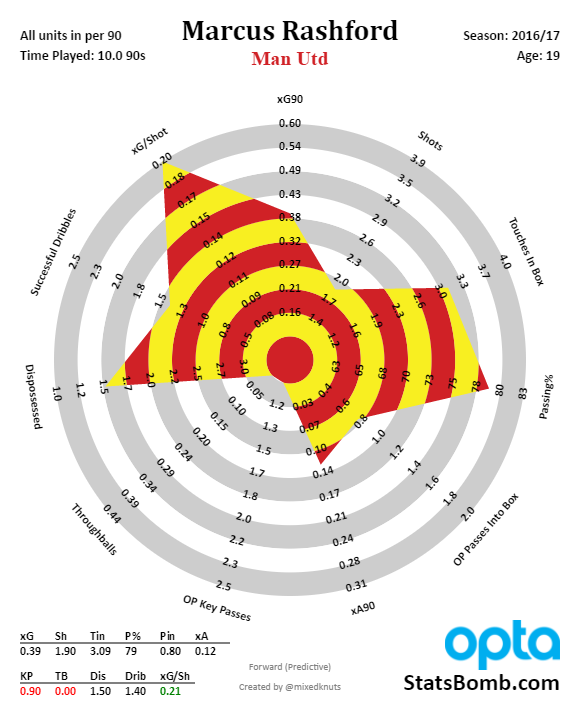

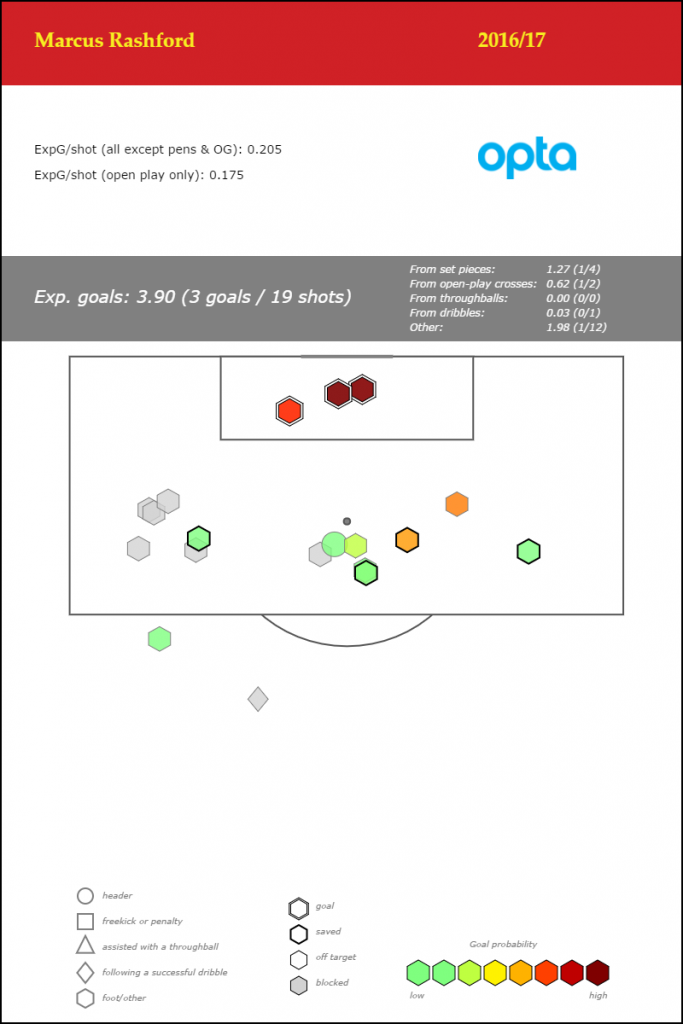

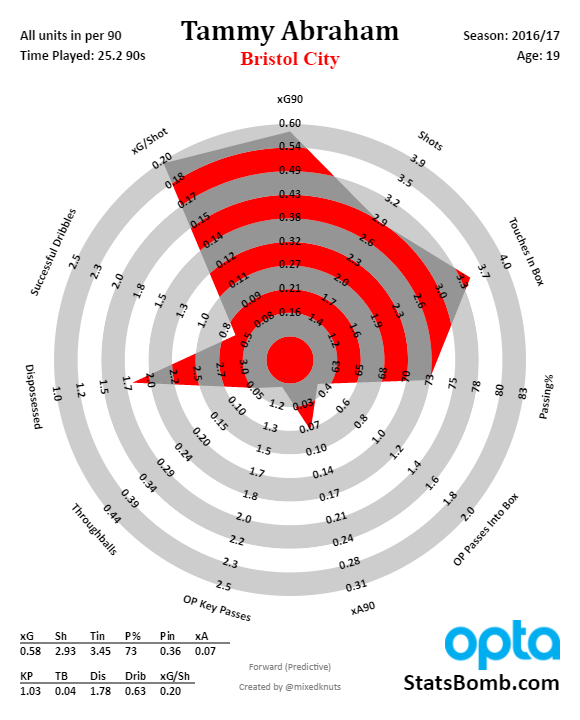

My opinion from this summer on what Rashford was and what he could be is largely unchanged. The fact that he is scoring goals regularly in the Premier League at his age is notable by itself. Add to that a serious commitment to run at defenders this year and a bit more creative passing, and he looks like one of the best prospects to come out of Manchester in ages. He’s clearly still learning, but also good enough to start for most teams in the league right now, either as a center forward or as a wide forward. Tammy Abraham may be a less common household name right now, but he has been lighting up the Championship at Bristol City this year in his first season of senior football. The Chelsea loanee is only 19.

My opinion from this summer on what Rashford was and what he could be is largely unchanged. The fact that he is scoring goals regularly in the Premier League at his age is notable by itself. Add to that a serious commitment to run at defenders this year and a bit more creative passing, and he looks like one of the best prospects to come out of Manchester in ages. He’s clearly still learning, but also good enough to start for most teams in the league right now, either as a center forward or as a wide forward. Tammy Abraham may be a less common household name right now, but he has been lighting up the Championship at Bristol City this year in his first season of senior football. The Chelsea loanee is only 19.

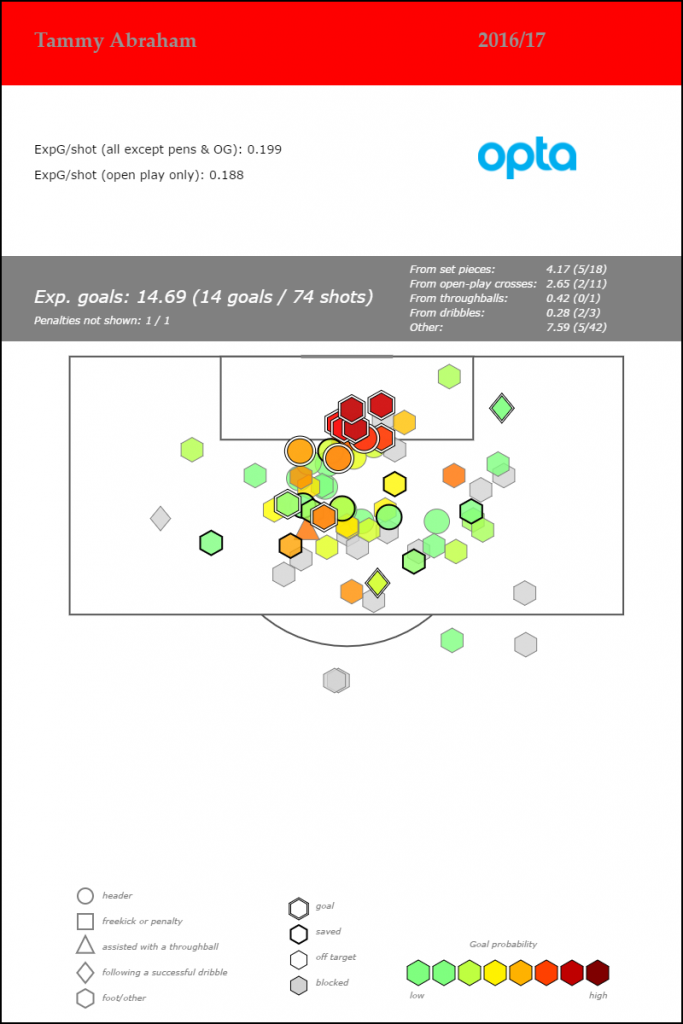

This is extremely unusual for a young forward, and looking backward one of the most similar profiles I can find at this age is another Chelsea loanee: Romelu Lukaku. Yes, Lukaku’s season came against Premier League competition and TamTam’s is in the Championship, but Lukaku certainly looked a bit more physically mature when he did it while Tammy still has some teenager left on those lanky bones. Back in February, my group at Brentford produced a list of young forwards that we thought would contribute to our club this season, and Abraham was at the very top of that list*. He is a breathtaking talent who is producing incredible numbers without being surrounded by particularly good teammates at Bristol City. So you know I'm legit on this, here's a tweet from the first day of the season in August.

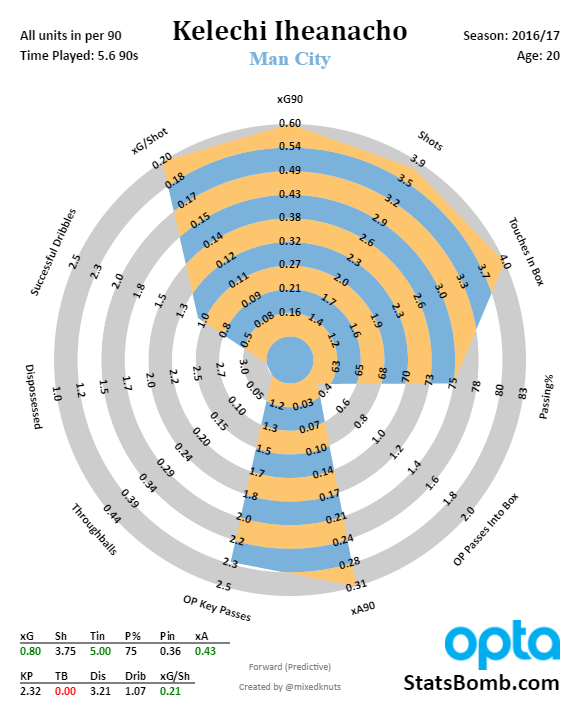

This is extremely unusual for a young forward, and looking backward one of the most similar profiles I can find at this age is another Chelsea loanee: Romelu Lukaku. Yes, Lukaku’s season came against Premier League competition and TamTam’s is in the Championship, but Lukaku certainly looked a bit more physically mature when he did it while Tammy still has some teenager left on those lanky bones. Back in February, my group at Brentford produced a list of young forwards that we thought would contribute to our club this season, and Abraham was at the very top of that list*. He is a breathtaking talent who is producing incredible numbers without being surrounded by particularly good teammates at Bristol City. So you know I'm legit on this, here's a tweet from the first day of the season in August.  (* The previous season we flagged up Sergi Canos and John Swift as good loanees, both of whom were excellent contributors, so pretty happy with the process there.) Anyway, back to the actual question: say for the next five seasons would you rather have Rashford or Abraham? The statistician in me leans Rashford. Obviously he’s performing against better competition, and the success he is having as a wide forward at his age is more rare and unusual than Abraham’s profile. Yung Rash is the real deal already, and who knows how high his ceiling is? The scout in me leans Abraham. He’s killing it week in and week out, in a very physical league, without the help of United’s amazing squad around him. His passing as a CF is probably better than average, and he has pace, strength, and surprising technical ability for a player his size. He’ll be in the Premier League next season and will likely not look at all out of place. Both of these guys are part of the English National Team setup, and England is absolutely spoiled for choice at the attacking positions for what looks like a decade to come. Oh, and before we change topics, Kelechi Iheanacho at City still looks really special.

(* The previous season we flagged up Sergi Canos and John Swift as good loanees, both of whom were excellent contributors, so pretty happy with the process there.) Anyway, back to the actual question: say for the next five seasons would you rather have Rashford or Abraham? The statistician in me leans Rashford. Obviously he’s performing against better competition, and the success he is having as a wide forward at his age is more rare and unusual than Abraham’s profile. Yung Rash is the real deal already, and who knows how high his ceiling is? The scout in me leans Abraham. He’s killing it week in and week out, in a very physical league, without the help of United’s amazing squad around him. His passing as a CF is probably better than average, and he has pace, strength, and surprising technical ability for a player his size. He’ll be in the Premier League next season and will likely not look at all out of place. Both of these guys are part of the English National Team setup, and England is absolutely spoiled for choice at the attacking positions for what looks like a decade to come. Oh, and before we change topics, Kelechi Iheanacho at City still looks really special.

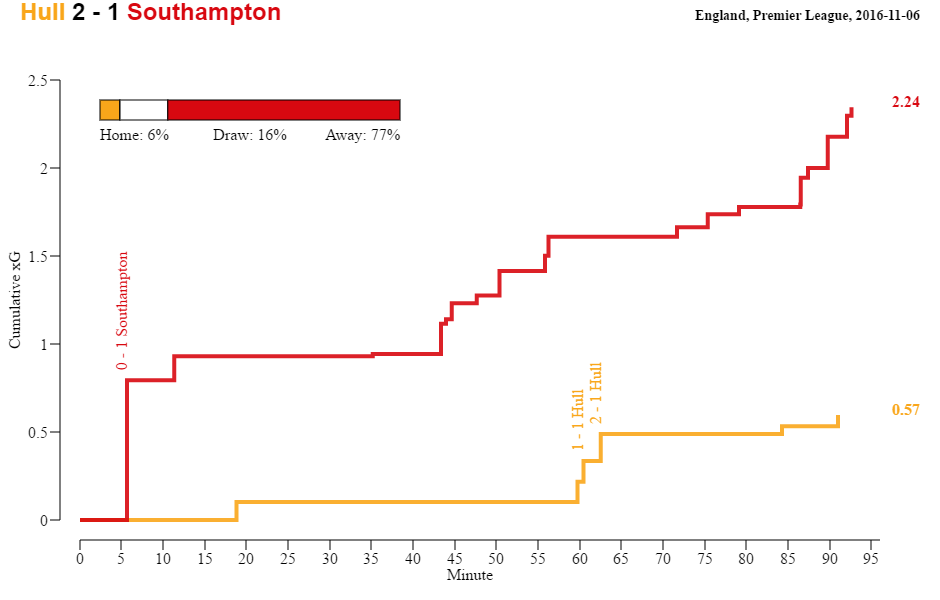

The Premier League Cliff Some years the relegation battle is all we have left for excitement by the end of the season. Others, it’s the race for the final Champions League spot. Once a generation you might get "AGUEROOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!" This year, the entire table seems to be in motion every single week, but I find the bottom of the table particularly intriguing. Two early, improbable wins disguised it for a while, but Hull have been the worst team in the league since the start. They have a squad stuck between Championship and Premier League calibre and though they were probably improving a bit in recent months, they still hadn’t beaten anyone since *scrolls through fixture list* *still scrolling* Uh… Jesus, November 6th against Southampton. Even that was *ahem* a bit fortunate.

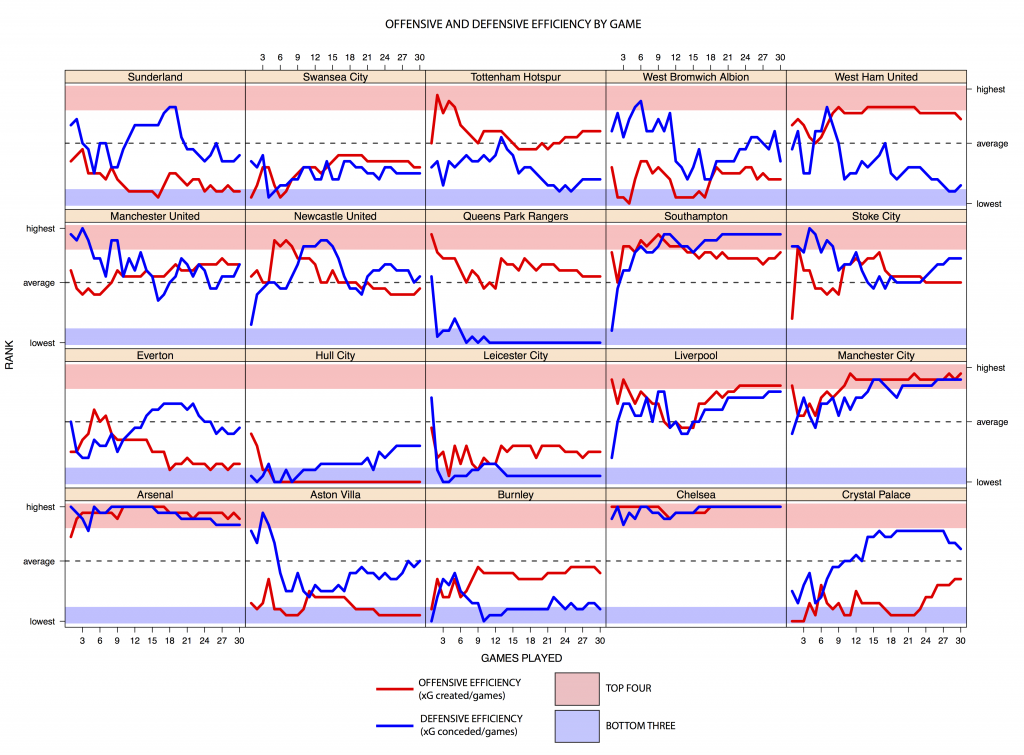

The Premier League Cliff Some years the relegation battle is all we have left for excitement by the end of the season. Others, it’s the race for the final Champions League spot. Once a generation you might get "AGUEROOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!" This year, the entire table seems to be in motion every single week, but I find the bottom of the table particularly intriguing. Two early, improbable wins disguised it for a while, but Hull have been the worst team in the league since the start. They have a squad stuck between Championship and Premier League calibre and though they were probably improving a bit in recent months, they still hadn’t beaten anyone since *scrolls through fixture list* *still scrolling* Uh… Jesus, November 6th against Southampton. Even that was *ahem* a bit fortunate.  So yeah, change was needed and Hull went way off the beaten path to hire former Sporting Lisbon and Olympiakos boss Marco Silva. I like this appointment for lots of reasons, not least that it should give them an actual chance to survive pending additional recruitment this month, and it doesn't recycle old names. They are 4 points off safety with 18 games left. It’s an ask, but I am saying there's a chance. Moving up the table, we have The Swansea Debacle. A club that can’t stop shooting themselves in the foot has named Paul Clement as a perfectly reasonable head coaching appointment that also gives them a shot at survival. Like Hull, their squad is also a mixed bag of talent, with two solid forwards, some decent pieces dotted around the pitch, and yet huge need for upgrades in about five positions. Like we discussed above with Manchester City, if you recruit poorly for a couple of seasons in a row, you will eventually pay a price. Swansea’s Premier League dreams will live or die on Clement’s ability to solidify the defense while still allowing them to create enough goals to get 3 points on a regular basis. One simple barometer of doom that I discovered a couple of seasons ago is the 16 Shots Rule. If your club is giving up 16 shots or more a game, you have a strong probability of being relegated. Burnley are defying this metric this season because Sean Dyche has somehow crafted a Jekyll and Hyde tactical team who are surprisingly good at home – 5th best in the league right now with 22 points - while being the worst team in the league on the road. Their home return means they are almost certainly safe this year, and if Dyche can figure out how to bring similar output to Burnley’s road performances, they may become mainstays in the PL, at which point the media will suddenly appreciate him more and begin referring to him as Dutch tactical mastermind Jan Dijks. (Shout out to @noverheul for the nickname.) The doom clock doth toll, and it tolls for Sunderland. David Moyes's team are giving up nearly 19 shots a game, and circling the Premier League toilet bowl, waiting to be flushed. We know Moyes’s Everton teams were difficult to beat, but Sunderland are tied for most losses in the league with 13. Something is clearly lacking at the Stadium of Light beyond funds for additional transfers. That said, given Moyes's history, it’s tough to completely rule them out either. Directly above Sunderland, one point away from being flushable, are Crystal Palace. The complicated reign of Alan Pardew is now over, and The Great Allardici has been tasked with his usual magic act of keeping a struggling club up. Their underlying metrics were actually pretty good even before Pardew was sacked, but the table position is precarious enough that a bad run will cause normally sweaty Big Sam to look like he’s managing in a sauna. Who doesn’t want to see that? Finally we get to the clubs that appear in relative safety. Aitor Karanka’s Middlesboro are dreadfully boring to watch, but are also 4 points plus strong goal difference away from the drop. They could get sucked down to the bottom, but it would take a strong final 18 matches from two clubs below them to cause any real trouble. Every other club from Leicester on up should surely fight on for another season and another massive injection of TV money. Maybe it’s just me, but I’m kind of looking forward to the relegation run-in of nearly competent teams desperately hanging on for another year. It's SCRABBLING FOR SAFETY SUNDAY, AND IT'S LIVE... Random xGChain Trivia I teased a new metric that Thom Lawrence has developed for StatsBomb Services on the podcast this week. I’m not going to steal Thom’s thunder – he will write about it in detail next week, and then I will follow-up with more analysis after, but I am going to provide random historic trivia with absolutely zero explanation right now. I will say that we’re currently breaking it into xGChain/90 and what I refer to as xGChain Residual, but Thom may end up calling Pre-xGCh**. Either way, please enjoy.

So yeah, change was needed and Hull went way off the beaten path to hire former Sporting Lisbon and Olympiakos boss Marco Silva. I like this appointment for lots of reasons, not least that it should give them an actual chance to survive pending additional recruitment this month, and it doesn't recycle old names. They are 4 points off safety with 18 games left. It’s an ask, but I am saying there's a chance. Moving up the table, we have The Swansea Debacle. A club that can’t stop shooting themselves in the foot has named Paul Clement as a perfectly reasonable head coaching appointment that also gives them a shot at survival. Like Hull, their squad is also a mixed bag of talent, with two solid forwards, some decent pieces dotted around the pitch, and yet huge need for upgrades in about five positions. Like we discussed above with Manchester City, if you recruit poorly for a couple of seasons in a row, you will eventually pay a price. Swansea’s Premier League dreams will live or die on Clement’s ability to solidify the defense while still allowing them to create enough goals to get 3 points on a regular basis. One simple barometer of doom that I discovered a couple of seasons ago is the 16 Shots Rule. If your club is giving up 16 shots or more a game, you have a strong probability of being relegated. Burnley are defying this metric this season because Sean Dyche has somehow crafted a Jekyll and Hyde tactical team who are surprisingly good at home – 5th best in the league right now with 22 points - while being the worst team in the league on the road. Their home return means they are almost certainly safe this year, and if Dyche can figure out how to bring similar output to Burnley’s road performances, they may become mainstays in the PL, at which point the media will suddenly appreciate him more and begin referring to him as Dutch tactical mastermind Jan Dijks. (Shout out to @noverheul for the nickname.) The doom clock doth toll, and it tolls for Sunderland. David Moyes's team are giving up nearly 19 shots a game, and circling the Premier League toilet bowl, waiting to be flushed. We know Moyes’s Everton teams were difficult to beat, but Sunderland are tied for most losses in the league with 13. Something is clearly lacking at the Stadium of Light beyond funds for additional transfers. That said, given Moyes's history, it’s tough to completely rule them out either. Directly above Sunderland, one point away from being flushable, are Crystal Palace. The complicated reign of Alan Pardew is now over, and The Great Allardici has been tasked with his usual magic act of keeping a struggling club up. Their underlying metrics were actually pretty good even before Pardew was sacked, but the table position is precarious enough that a bad run will cause normally sweaty Big Sam to look like he’s managing in a sauna. Who doesn’t want to see that? Finally we get to the clubs that appear in relative safety. Aitor Karanka’s Middlesboro are dreadfully boring to watch, but are also 4 points plus strong goal difference away from the drop. They could get sucked down to the bottom, but it would take a strong final 18 matches from two clubs below them to cause any real trouble. Every other club from Leicester on up should surely fight on for another season and another massive injection of TV money. Maybe it’s just me, but I’m kind of looking forward to the relegation run-in of nearly competent teams desperately hanging on for another year. It's SCRABBLING FOR SAFETY SUNDAY, AND IT'S LIVE... Random xGChain Trivia I teased a new metric that Thom Lawrence has developed for StatsBomb Services on the podcast this week. I’m not going to steal Thom’s thunder – he will write about it in detail next week, and then I will follow-up with more analysis after, but I am going to provide random historic trivia with absolutely zero explanation right now. I will say that we’re currently breaking it into xGChain/90 and what I refer to as xGChain Residual, but Thom may end up calling Pre-xGCh**. Either way, please enjoy.

- Arsenal’s highest xGChain player in 14-15 was Santi Cazorla. He was also Arsenal’s highest player in 15-16. Pretty interesting, given their struggles without him.

- I knew Atletico Madrid’s Angel Correa was good, but he has the top xGCh value for them so far this season, above Gameiro and well ahead of Antoine Griezmann.

- Neymar actually had the highest xGChain/90 at Barcelona last season, and not Lionel Messi.

- Xavi 10-11 has the highest residual xGChain score in the data followed closely by Jerome Boateng at Bayern last in 15-16. Yes, a center back.

- The highest non-Bayern, non-Barcelona players in residual xGChain values are Ozil at Real Madrid in 12-13, Cazorla at Arsenal last season, and Gundogan at Dortmund also in 15-16.

Oh, and back when I first started toying with Manager Fingerprints in 2013, I described Mark Hughes as a bang average Premier League manager. Stoke are currently 11th in the table, having finished 9th, 9th, and well... 9th in the previous three seasons. Some times "average" really is a bit of a compliment. Have a good weekend! --Ted Knutson @mixedknuts mixedknuts@gmail.com ** If you want to complain about names, feel free to develop your own metrics instead 😀

In the 69th minute of the most important derby in English football (that's still the case right?) Manchester United lead Liverpool 1-0 with the game obviously still very much open. An average team in Liverpool’s position would still expect to draw or win the game about 21% of the time, not ideal but nowhere near a lost cause.

With United on the attack and the ball in the final third Carrick plays a weighted ball through to Ander Herrera who latches onto it on the edge of the penalty area. Right here Gomez has a decision to make, he can accept that his positioning wasn't great but just try and track Herrera as quickly as possible, or he can try and redeem himself with a last-ditch tackle near the byline.

Unfortunately for Liverpool Gomez attempted to make up for his poor positional play with a rash tackle on Herrera, fouling him in the process, and greatly diminishing Liverpool's chances of getting anything from the game. It's alright saying it was a stupid decision to dive in with hindsight, but let's try and put a value on the decision Gomez made.

Say there are two different options for a defender in this position, he can either:

- Act aggressively - Attempt to win the ball, or block the ball by sliding in.

- Act conservatively - Stay on his feet and apply as much pressure to the forward as possible without possibility of fouling.

We can have a look at the possible outcomes for each scenario and try and evaluate the value of each action. We're going to define value as the probability of a team scoring from a certain event, adjusting for the possibility of the opposition scoring as a result of the event's outcome when possible.

Aggressive defending: Going to try and split this up into 2:

- Value of a penalty

- Value of every other possible situation

Value of a penalty

- Penalty given away- in the past 15 years in EPL 80% of penalties have been scored so

Value of a penalty = 0.8

Value of other situations

- Player shoots - Shot conversion from wide penalty areas are converted about 5.6% of the time , more pressure probably reduces this probability, especially if the block rate is higher, so let's say 4-5%

- Player crosses - Let's assume high pressure on cross makes cross more difficult. A cross inside the box is converted about 5% of the time but let’s be generous and say pressure causes value to be about 4%

- Player is tackled before he takes an offensive action - Three things could happen here

- Tackle goes for a corner - 3%

- Offense retains possession - about 2-3%

- Defense obtains possession - 0%

I'm going to assume they all happen at a similar rate and take the average of these at 2% I haven’t got data on the probability that each of these events occur but they're all within range of a value around 2-5%. Based on what seems right, just from a spectators standpoint, I'm going to assume again that these all occur at a similar rate and just find the average to get a value of 3.5%. Obviously I'm making pretty loose assumptions but I'll show why this isn't too important in this particular situation later.

Value of everything else = 0.035

Conservative defending If a defender is conservative the possible outcomes are:

- Player shoots - Shots from this area are converted about 5.6% of the time, let's say 7% when not pressured.

- Player crosses – Crosses in the box are usually converted at about 5% similar to shots from this area, let’s assume slightly more and again say 7% in box when not as pressured

Value of conservative play = 0.07

Since both possible outcomes have about the same chance of conversion the total value is equal to the conversion rate. We are assuming that being conservative makes the opposition twice as likely to score compared to when defending aggressively, I’d like to think this is an assumption which , if biased, is favoured towards aggressive defending.

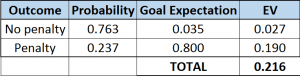

Expected Value

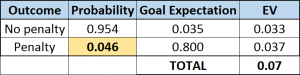

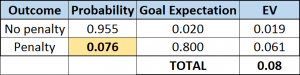

Okay then let’s do some math. The expected value of each decision is the number of goals the opposition would expect to score given a certain defensive strategy. In this instance (defending) we would want the lowest number possible. So the expected value of playing aggressively is p(0.8) + q(0.035) where "p" is the probability of giving away a penalty, “q” the probability of not giving away a penalty, and therefore p+q=1. The expected value of playing conservatively is 0.07.

From an expected value point of view it only makes sense to defend aggressively if p(0.8)+q(0.035)<0.07, or the chance of the opposition scoring is less than 7%. It turns out that this is only true if “q” (probability of giving up a penalty) is less than 4.6% which seems extremely low. Even if we assume aggressive defending decreases the value of attacking play to 2%, whilst reserved play increases it to 8% you’d need to have a less than 7.6% chance of conceding a penalty in order for being aggressive to make sense. So even when scoring is 4 times more likely when being conservative (which seems pretty extreme), you’d need to be very confident of not fouling in order for this to make sense

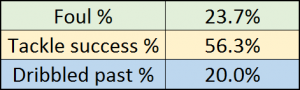

To endeavour to find an approximate value for the proportion of tackles that end up as fouls I decided to collect data for tackles attempted, tackles made, and fouls for premier league defenders over the 2014/15 Premier League season. Now not every foul made is during a tackle, although a foul is an indicator of aggressive defensive play so I decided to include all fouls. With these assumptions I calculated proportion of fouls as.

Foul% = Fouls / (Fouls + Tackles attempted)

This worked out as 23.7% for Premier league defenders last year, Tackle success rate was 56.3% and defenders were dribbled past without committing a foul 20% of the time. From this it’s quite obvious to conclude that defenders should probably never be aggressive in the wide areas of the penalty area since the value of a penalty is far too high to make it worth risking a foul.

Even if you take into consideration referees swallowing the whistle, meaning refereeing calls are usually given less frequently in high leverage situations or in this case fouls in penalty area, it still doesn't make sense. In order for the foul percentage to fall from 23.7% to less than 7.7% there's got to be some serious whistle swallowing going on. If we go back to our original expected values of 0.8, 0.035, and 0.07, and assume the probability of a foul to be 23.7% we can work out the expected number of goals this would cost a team.

You can see from the table that attempting a tackle in the wide areas of the penalty box on average costs the team 0.146 goals (0.216 - 0.07 = 0.146), which may not sound much, but that’s about half of the goal advantage that an average team playing at home has over the away team.

Managers should be telling their defenders not to dive in or stick a leg out when opposing players are in the wide areas of the penalty box as it never seems to be worth the risk. I think the reason many defenders are too aggressive in this situation is that since defending is reactive compared to attacking being proactive, defenders may feel they need to be risk-seeking in order to make an impact, and in this case it isn't the optimal choice.

It's quite strange that this is the case because teams are usually too risk averse, although maybe attackers are risk averse and defenders are risk seeking, but the proactive attackers have more influence on the game overall, just spitballing but it's an interesting discussion. Just as I was writing this a perfect example of reckless decision making popped up on my twitter feed from the Barcelona vs Rayo Vallecano game, although I'm not even sure if you can class this as decision making.

There are many other situations like this where decision making can be analysed based on expected value and although this may seem like an obvious one from a spectators standpoint defenders still play aggressively in the wide sections of the penalty area. More accurate data will be needed for decisions less obvious than this one but it can still be done and can inform teams where they are losing goals based on decision making. If a team can save themselves .15 goals a game based on simple decisions like this they would save themselves 5.7 goals over the course of the season. In the end that really could be the difference between the club having a successful year and an unsuccessful one.

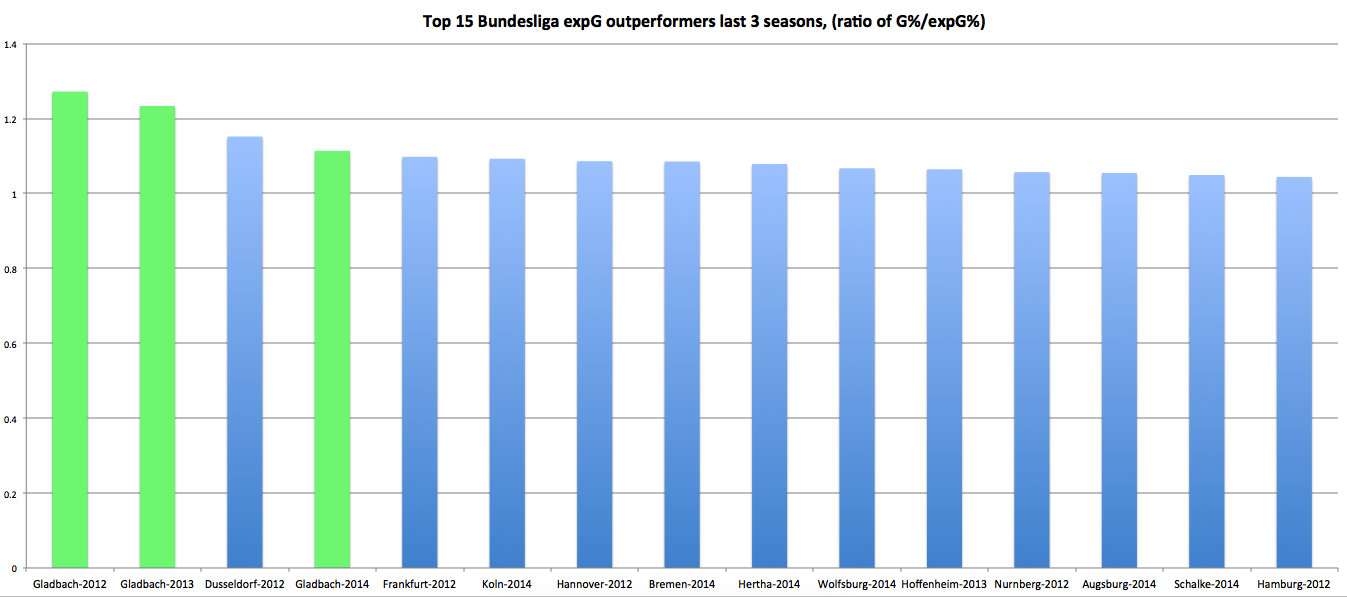

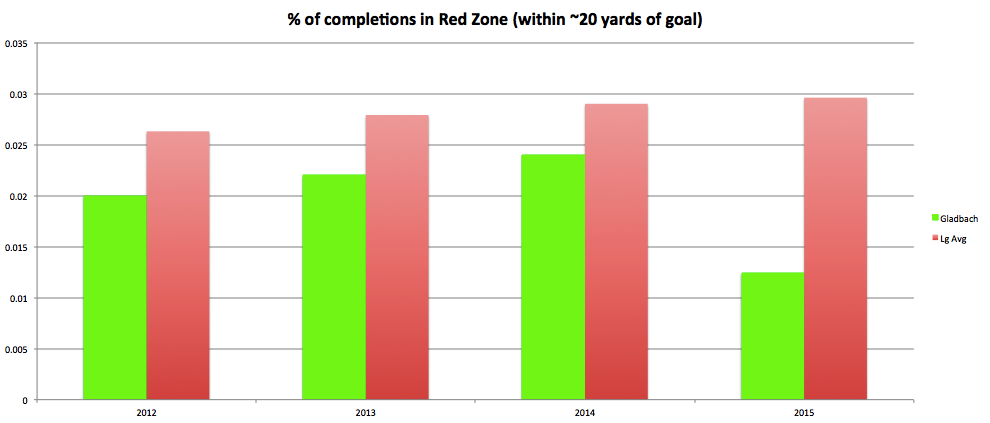

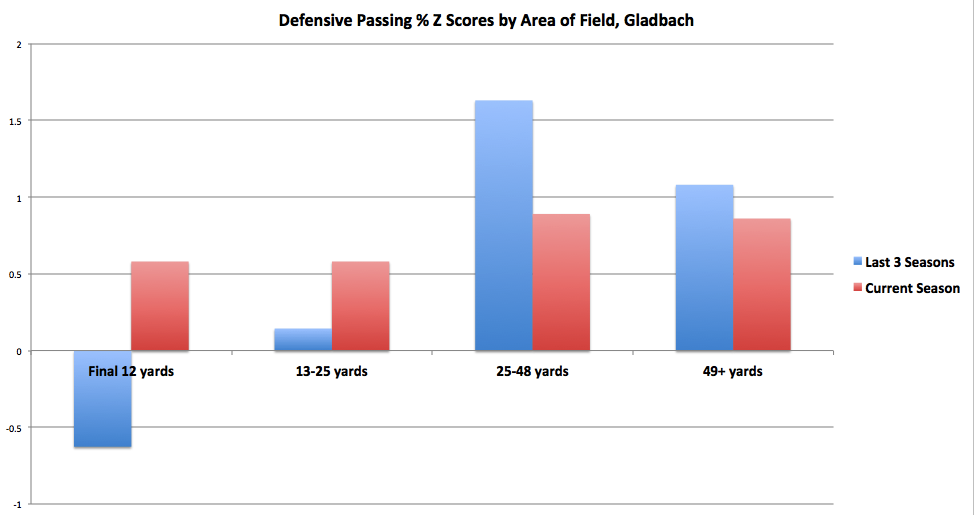

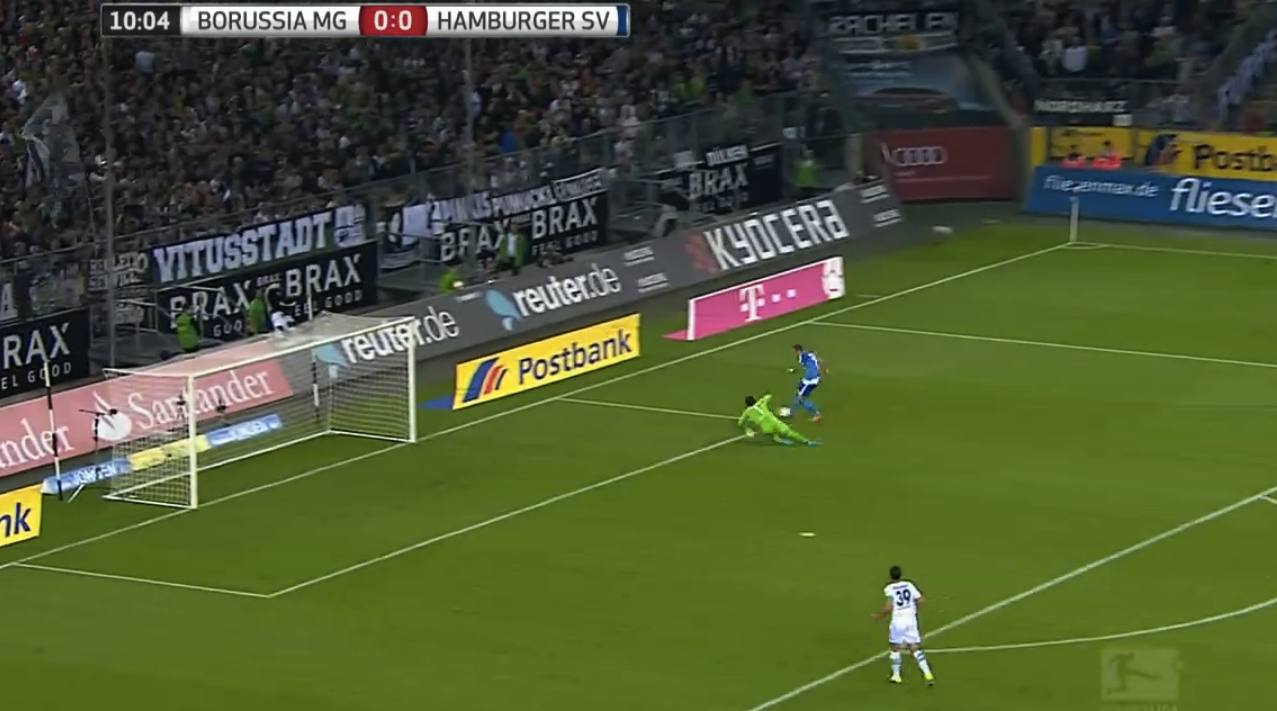

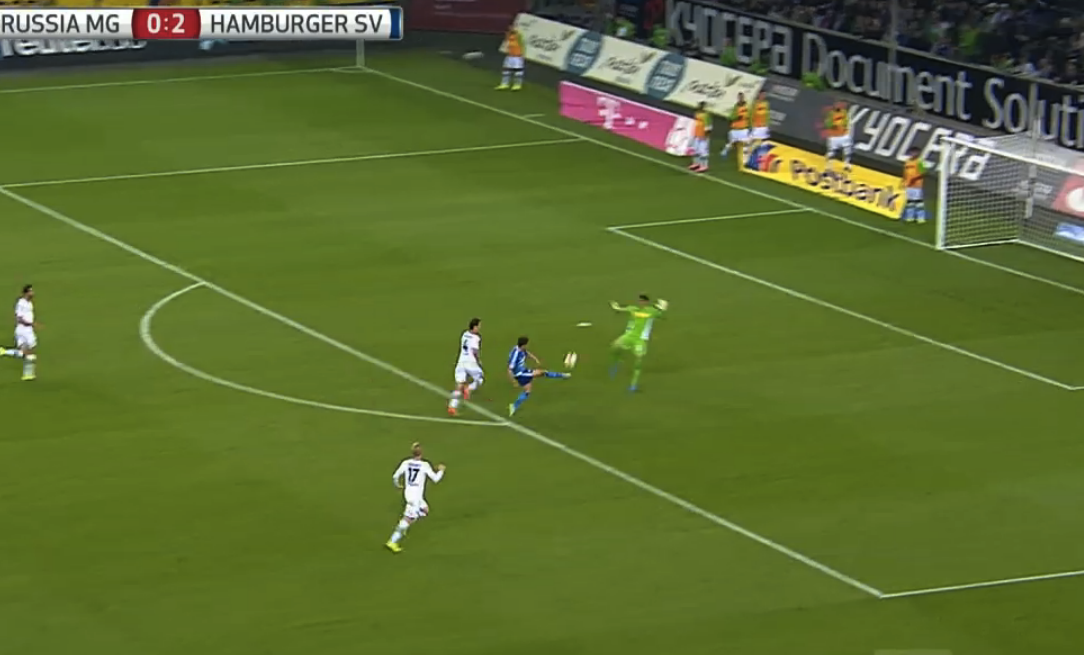

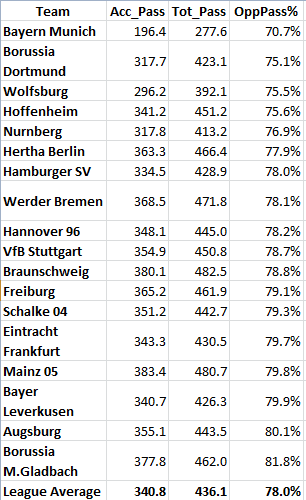

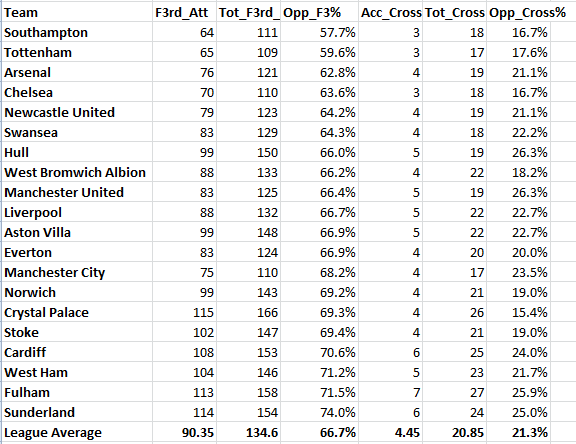

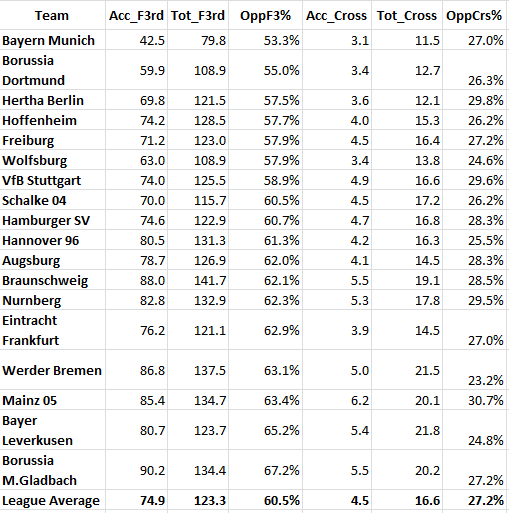

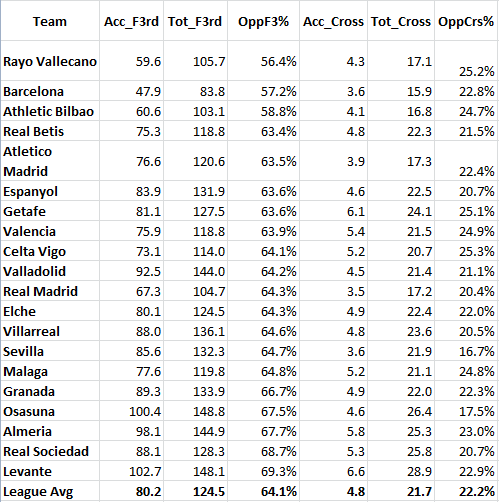

Gladbach were the hot topic around the soccer stat Twittersphere last Friday as they were hammered by generally woeful Hamburg. This dropped the Foals to 4 games, 0 points, 2 goals for, 11 goals against and very much in last place in the Bundesliga. First some context as to why this blew up: Gladbach have had 3 very good seasons in succession despite posting average-to-really bad xG numbers. This chart should help tell the story.

Gladbach were the hot topic around the soccer stat Twittersphere last Friday as they were hammered by generally woeful Hamburg. This dropped the Foals to 4 games, 0 points, 2 goals for, 11 goals against and very much in last place in the Bundesliga. First some context as to why this blew up: Gladbach have had 3 very good seasons in succession despite posting average-to-really bad xG numbers. This chart should help tell the story.  They had 3 of the 4 largest xGR outperformances in the past 3 seasons in Germany. I made the case in this article that they weren’t just a below-average team getting incredibly lucky, they were actually a good team being shorted by a model that didn’t cover what they did very well (mainly pressure opponents while shooting and then last season using a patient, multiple attack to get higher quality shots). The debate on twitter featured two StatsBomb legends coming out and basically saying Gladbach cannot beat xG long-term. Ben Pugsley said “Given enough time….barely any team is special” and Colin Trainor said it would be normal for some team to overperform xG 3 straight years given enough trials, which is true enough. Michael Caley hinted he thought the tactic had been collectively found out and that certain tactics could beat xG for a little bit before falling back to their underlying shot numbers. The 3-year run was over. In general the tone seemed to be, well this team has been lucky for so long, that now it is evening out. The insinuation being their true talent level during past seasons was reflected by the xG models and not the results on the field. I think in general this is a dangerous assumption to make and disagree in this case as well.

They had 3 of the 4 largest xGR outperformances in the past 3 seasons in Germany. I made the case in this article that they weren’t just a below-average team getting incredibly lucky, they were actually a good team being shorted by a model that didn’t cover what they did very well (mainly pressure opponents while shooting and then last season using a patient, multiple attack to get higher quality shots). The debate on twitter featured two StatsBomb legends coming out and basically saying Gladbach cannot beat xG long-term. Ben Pugsley said “Given enough time….barely any team is special” and Colin Trainor said it would be normal for some team to overperform xG 3 straight years given enough trials, which is true enough. Michael Caley hinted he thought the tactic had been collectively found out and that certain tactics could beat xG for a little bit before falling back to their underlying shot numbers. The 3-year run was over. In general the tone seemed to be, well this team has been lucky for so long, that now it is evening out. The insinuation being their true talent level during past seasons was reflected by the xG models and not the results on the field. I think in general this is a dangerous assumption to make and disagree in this case as well.

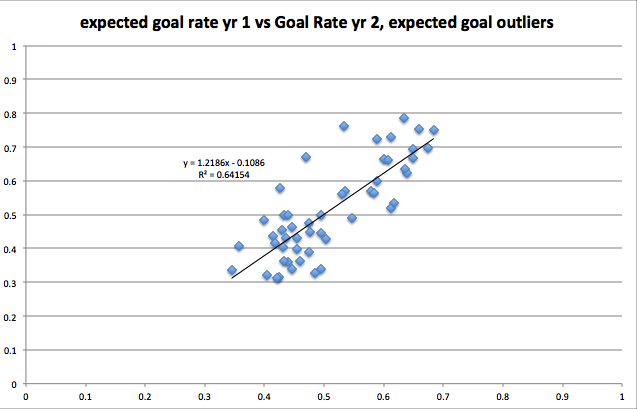

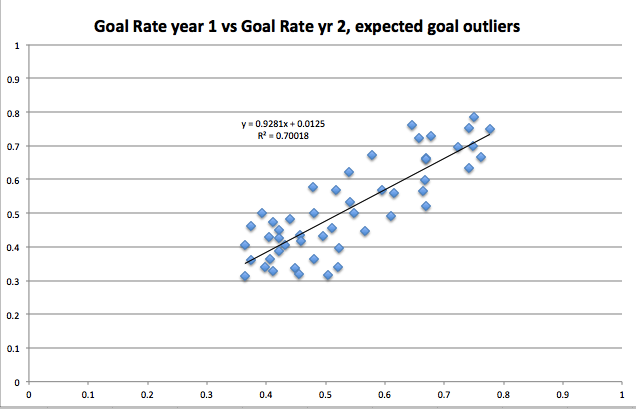

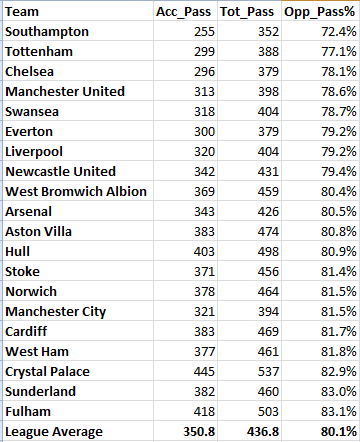

xG hasn't nailed enough outliers for me to be confident in proclaiming teams drastically lucky or unlucky based only on xG rate. I disagree with Colin and Ben, both of whom I have great respect for. I do so knowing I might be wrong and willing to engage with anyone who wants to bring their case in the comments or on twitter. Let me lay my case out first. I don’t think this is a team simply playing as well as they always have been and midnight has finally struck. There are clear indicators that this year, the performance is significantly worse compared to years past. So even though it’s been 5 games*, I took a look at what has changed for Gladbach. *For me, 5 games is plenty to look at trends of how a team possesses and defends passes. Passing stats stabilize a lot quicker than shooting stats, so they can reveal trends quicker than shots/goals. If 1000 player minutes is enough to start making judgement calls on some player shot metrics, team pass metrics have now had nearly 5000 player minutes so should be able to tell us something. Offense

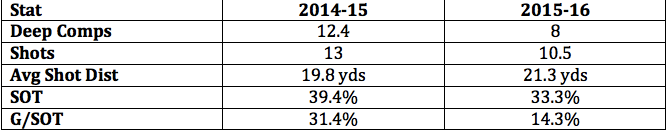

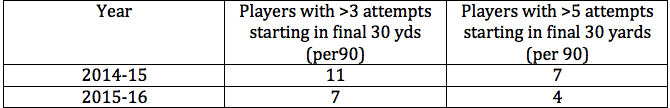

xG hasn't nailed enough outliers for me to be confident in proclaiming teams drastically lucky or unlucky based only on xG rate. I disagree with Colin and Ben, both of whom I have great respect for. I do so knowing I might be wrong and willing to engage with anyone who wants to bring their case in the comments or on twitter. Let me lay my case out first. I don’t think this is a team simply playing as well as they always have been and midnight has finally struck. There are clear indicators that this year, the performance is significantly worse compared to years past. So even though it’s been 5 games*, I took a look at what has changed for Gladbach. *For me, 5 games is plenty to look at trends of how a team possesses and defends passes. Passing stats stabilize a lot quicker than shooting stats, so they can reveal trends quicker than shots/goals. If 1000 player minutes is enough to start making judgement calls on some player shot metrics, team pass metrics have now had nearly 5000 player minutes so should be able to tell us something. Offense  The raw numbers show the offense is clearly worse, but some digging shows things are acutally even worse than a 2.5 drop in shots seems on the surface. Last year they were the best team in the Bundesliga when it came to completing passes in dangerous areas. They were 2 standard deviations above average in deep areas. This year that is not close to the case. Let's see why. They can’t get up the field A league worst 1.2% of Gladbach’s completions come in the Red Zone (within ~20 yards of opp goal). The league average is 3% and the Foals rate would easily be the worst single-season rate in the last 4 seasons in the Bundesliga if they keep it up.

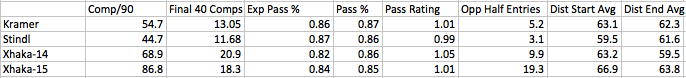

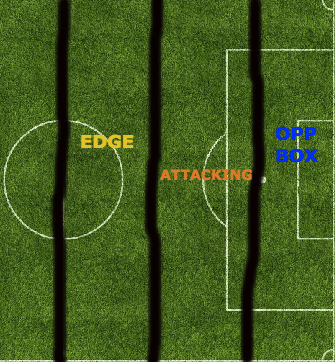

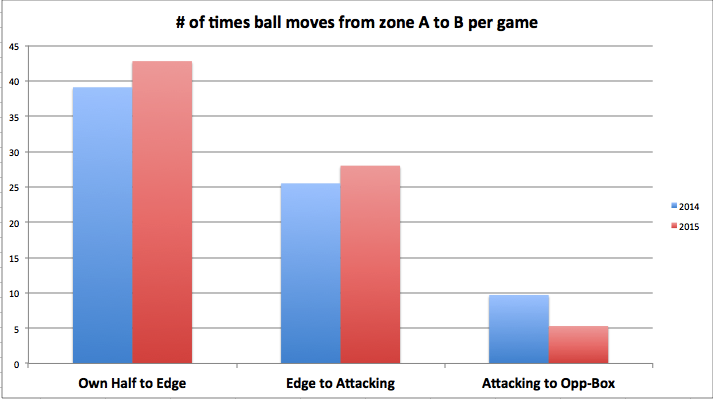

The raw numbers show the offense is clearly worse, but some digging shows things are acutally even worse than a 2.5 drop in shots seems on the surface. Last year they were the best team in the Bundesliga when it came to completing passes in dangerous areas. They were 2 standard deviations above average in deep areas. This year that is not close to the case. Let's see why. They can’t get up the field A league worst 1.2% of Gladbach’s completions come in the Red Zone (within ~20 yards of opp goal). The league average is 3% and the Foals rate would easily be the worst single-season rate in the last 4 seasons in the Bundesliga if they keep it up.  The problem intensified vs Sevilla as they had just 4 of their 353 completions in the Red Zone (1.1%). These completions are coming as a result of much longer passes as well. Last year their average pass distance for a Red Zone completion was the 2nd shortest in the Bundesliga at 14.1 yards, this year so far it has been the 3rd longest (behind only Ingolstadt and Darmstadt) at 21.6 yards. An increase of nearly 7 yards makes a significant difference in the amount of attempts you can expect to complete. So we see the problem, but where does it originate on the pitch? The Dortmund and Sevilla games were the largest hammerings and it seemed they couldn’t get out of their own half so I thought maybe they are just getting stuck close to their own goal. My eye test was not correct (a disappointingly common occurrence): Gladbach have moved into the opposition half slightly more often compared to last year. One possible problem this far from goal is that Xhaka has had to do way more offensive work in total and starts his work closer to goal as Stindl hasn’t quite replaced Kramer’s offensive production. Being so focused on one player to move the ball upfield doesn’t seem like it’s a great tendency for a team to have.

The problem intensified vs Sevilla as they had just 4 of their 353 completions in the Red Zone (1.1%). These completions are coming as a result of much longer passes as well. Last year their average pass distance for a Red Zone completion was the 2nd shortest in the Bundesliga at 14.1 yards, this year so far it has been the 3rd longest (behind only Ingolstadt and Darmstadt) at 21.6 yards. An increase of nearly 7 yards makes a significant difference in the amount of attempts you can expect to complete. So we see the problem, but where does it originate on the pitch? The Dortmund and Sevilla games were the largest hammerings and it seemed they couldn’t get out of their own half so I thought maybe they are just getting stuck close to their own goal. My eye test was not correct (a disappointingly common occurrence): Gladbach have moved into the opposition half slightly more often compared to last year. One possible problem this far from goal is that Xhaka has had to do way more offensive work in total and starts his work closer to goal as Stindl hasn’t quite replaced Kramer’s offensive production. Being so focused on one player to move the ball upfield doesn’t seem like it’s a great tendency for a team to have.

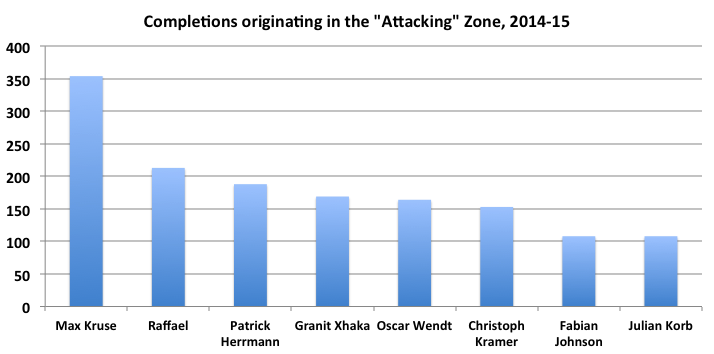

The big problem comes making the final leap, from the “attacking” area into the “opp box” area. Last year nearly twice as many completions were played into this area. It’s not a one-man problem when you see such a huge fall but the Max Kruse-sized hole shows up big-time here.

The big problem comes making the final leap, from the “attacking” area into the “opp box” area. Last year nearly twice as many completions were played into this area. It’s not a one-man problem when you see such a huge fall but the Max Kruse-sized hole shows up big-time here.  Losing Kruse meant when Gladbach gets deep this year they need to rely on players who were not as good a passer as Kruse was like Hazard, Traore and Hahn (who graded atrociously last season). Now the ball gets close but doesn’t get into a dangerous area as often. No one has increased their load to pick up the slack. When you can’t get the ball deep, you can’t get the number of options needed forward that allows you to have a multifaceted attack. If you want to get open shots playing at a deliberate pace, it’s not going to happen as often with hoofing long balls to a single striker. Gladbach aren’t getting as many different players up the field. Players like Xhaka, Patrick Herrmann, and Raffael are simply possessing the ball much less close to goal.

Losing Kruse meant when Gladbach gets deep this year they need to rely on players who were not as good a passer as Kruse was like Hazard, Traore and Hahn (who graded atrociously last season). Now the ball gets close but doesn’t get into a dangerous area as often. No one has increased their load to pick up the slack. When you can’t get the ball deep, you can’t get the number of options needed forward that allows you to have a multifaceted attack. If you want to get open shots playing at a deliberate pace, it’s not going to happen as often with hoofing long balls to a single striker. Gladbach aren’t getting as many different players up the field. Players like Xhaka, Patrick Herrmann, and Raffael are simply possessing the ball much less close to goal.  attempts here refers to passes Their extremely patient approach (.77 shots per pass attempt inside 20 yards last year) isn’t effective when you can’t get players forward and have the ball for long periods deep in opponent territory. They are now taking 1.13 shots per pass attempt, well above the league average. Defense

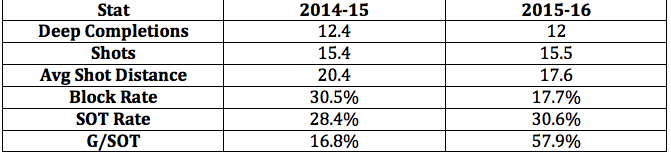

attempts here refers to passes Their extremely patient approach (.77 shots per pass attempt inside 20 yards last year) isn’t effective when you can’t get players forward and have the ball for long periods deep in opponent territory. They are now taking 1.13 shots per pass attempt, well above the league average. Defense  Here the raw numbers look essentially similar but the block rate and distance per shot are certainly worrying. So what’s changed on defense? Worse closer to goal In my piece on them last year, I concluded that their strategy of conceding the middle of the pitch and focusing on congesting their own box led to forcing opponents into more harried shots than normal and cutting off passing lanes that could lead to a better shot. This is seen by the “Last 3 Seasons” bars in the chart below. Also in that chart, you see that there is no such effect this season. Essentially the Gladbach defense is basically as good stopping passes near the goal as they are the rest of the field, which makes it hard to conclude they are getting good pressure on shooters.

Here the raw numbers look essentially similar but the block rate and distance per shot are certainly worrying. So what’s changed on defense? Worse closer to goal In my piece on them last year, I concluded that their strategy of conceding the middle of the pitch and focusing on congesting their own box led to forcing opponents into more harried shots than normal and cutting off passing lanes that could lead to a better shot. This is seen by the “Last 3 Seasons” bars in the chart below. Also in that chart, you see that there is no such effect this season. Essentially the Gladbach defense is basically as good stopping passes near the goal as they are the rest of the field, which makes it hard to conclude they are getting good pressure on shooters.  (Final 12 and 13-25 are combined in this season to get a reasonable sample size) The Film Room After inferring decreasing close-to-goal pressure from these passing numbers, I wanted to check with my own eyes. I watched film of every shot from the 5 games so far this season to count Gladbach defenders in the box. I then did the same with the equivalent fixtures from last year (except subbing in Hertha for Hamburg and missing a few shots in the Mainz/Dortmund games, shots that weren’t important enough to make a thorough highlight reel). The clear-cut chances stood out in a big way. Last season in 33 charted open-play, in-box shots, zero came when Gladbach had fewer than 3 defenders inside the box. This season in 45 shots, 6 have already come with fewer than 3 defenders. 3 of those shots have been converted into goals.

(Final 12 and 13-25 are combined in this season to get a reasonable sample size) The Film Room After inferring decreasing close-to-goal pressure from these passing numbers, I wanted to check with my own eyes. I watched film of every shot from the 5 games so far this season to count Gladbach defenders in the box. I then did the same with the equivalent fixtures from last year (except subbing in Hertha for Hamburg and missing a few shots in the Mainz/Dortmund games, shots that weren’t important enough to make a thorough highlight reel). The clear-cut chances stood out in a big way. Last season in 33 charted open-play, in-box shots, zero came when Gladbach had fewer than 3 defenders inside the box. This season in 45 shots, 6 have already come with fewer than 3 defenders. 3 of those shots have been converted into goals.

There were zero shots like this last season in the sample. It’s clear that the pressure they have always applied in the final 25 yards, increasing the closer you get to goal, is simply not there so far this season. Teams are passing very well in these areas and have broken through over once a game to take a shot against a basically abandoned box. Those are things that simply never happened last season. Now teams can spend more time picking and choosing their shots, which will certainly increase the chances of a goal. So while their raw shot numbers look about the same, under the surface there are massive problems. There are no individual defensive metrics I feel comfortable enough to divvy out the blame on this one. I will say losing Kramer, a sometime starter on the German national team cannot have helped. Fabian Johnson was injured in the opener and hasn’t returned. Maybe most importantly Martin Stranzl and Alvaro Dominguez, center-backs who started 41 combined games last season have both been out injured with Stranzl just returning for the last game. Replacing them have been mainly kids (19 and 20 year old started at center back vs Dortmund). That’s 4 key players from last years defense who have played 2 combined games this year. I don’t know how much that hurts, but it certainly is imaginable that a system like this is hard to simply plug and play at 4 key defensive positions. Conclusions Maybe Gladbach just didn't have enough talent to withstand the loss of stars like Max Kruse and Christoph Kramer. Maybe those two are way better than most people thought. Maybe this style of football is very precarious and when you downgrade certain parts, it all falls apart more quickly than other, more normal styles. Maybe things will totally turn around over the next two months. Any of those might be true. I can't say for sure, but what I do think is there has been enough in these 5 games to say Gladbach are playing much worse than they did last season. We aren't seeing a continued true talent level from last season with the only change being a correction in the luck category, there has been a significant performance drop. I certainly don't think I have completely explained everything about this drop above, soccer is much too complex a game to have supreme confidence about basically anything, much less something like this after just 5 games. Their performance will certainly change going forward but conclusions about xG in previous seasons should not be drawn from this team right now. They are not doing the things that pointed to xG outperformance. Gladbach were the team that kind of re-focused my energies away from fine-tuning a xG model and more toward looking at how teams pass and play on the entire field. Even if in a few months it turns out that proof emerges that xG was absolutely correct all along, I don't regret shifting focus. I have a clearer picture in my head of how Gladbach from looking deeper into passing stats, and I hope you do as well. Expected goals is a great stat and I love seeing the xG table compared to the regular table, but it's not always infallible and even when it turns out correct it's best use might be as a starting point to further investigation. I feel comfortable saying Gladbach over the past three years have shown us weaknesses in xG models and that's exciting to me. It means we haven't really solved how teams become good. The wide, wonderful world of excel spreadsheets, R consoles, and Tableau maps still has much to reveal.

There were zero shots like this last season in the sample. It’s clear that the pressure they have always applied in the final 25 yards, increasing the closer you get to goal, is simply not there so far this season. Teams are passing very well in these areas and have broken through over once a game to take a shot against a basically abandoned box. Those are things that simply never happened last season. Now teams can spend more time picking and choosing their shots, which will certainly increase the chances of a goal. So while their raw shot numbers look about the same, under the surface there are massive problems. There are no individual defensive metrics I feel comfortable enough to divvy out the blame on this one. I will say losing Kramer, a sometime starter on the German national team cannot have helped. Fabian Johnson was injured in the opener and hasn’t returned. Maybe most importantly Martin Stranzl and Alvaro Dominguez, center-backs who started 41 combined games last season have both been out injured with Stranzl just returning for the last game. Replacing them have been mainly kids (19 and 20 year old started at center back vs Dortmund). That’s 4 key players from last years defense who have played 2 combined games this year. I don’t know how much that hurts, but it certainly is imaginable that a system like this is hard to simply plug and play at 4 key defensive positions. Conclusions Maybe Gladbach just didn't have enough talent to withstand the loss of stars like Max Kruse and Christoph Kramer. Maybe those two are way better than most people thought. Maybe this style of football is very precarious and when you downgrade certain parts, it all falls apart more quickly than other, more normal styles. Maybe things will totally turn around over the next two months. Any of those might be true. I can't say for sure, but what I do think is there has been enough in these 5 games to say Gladbach are playing much worse than they did last season. We aren't seeing a continued true talent level from last season with the only change being a correction in the luck category, there has been a significant performance drop. I certainly don't think I have completely explained everything about this drop above, soccer is much too complex a game to have supreme confidence about basically anything, much less something like this after just 5 games. Their performance will certainly change going forward but conclusions about xG in previous seasons should not be drawn from this team right now. They are not doing the things that pointed to xG outperformance. Gladbach were the team that kind of re-focused my energies away from fine-tuning a xG model and more toward looking at how teams pass and play on the entire field. Even if in a few months it turns out that proof emerges that xG was absolutely correct all along, I don't regret shifting focus. I have a clearer picture in my head of how Gladbach from looking deeper into passing stats, and I hope you do as well. Expected goals is a great stat and I love seeing the xG table compared to the regular table, but it's not always infallible and even when it turns out correct it's best use might be as a starting point to further investigation. I feel comfortable saying Gladbach over the past three years have shown us weaknesses in xG models and that's exciting to me. It means we haven't really solved how teams become good. The wide, wonderful world of excel spreadsheets, R consoles, and Tableau maps still has much to reveal.

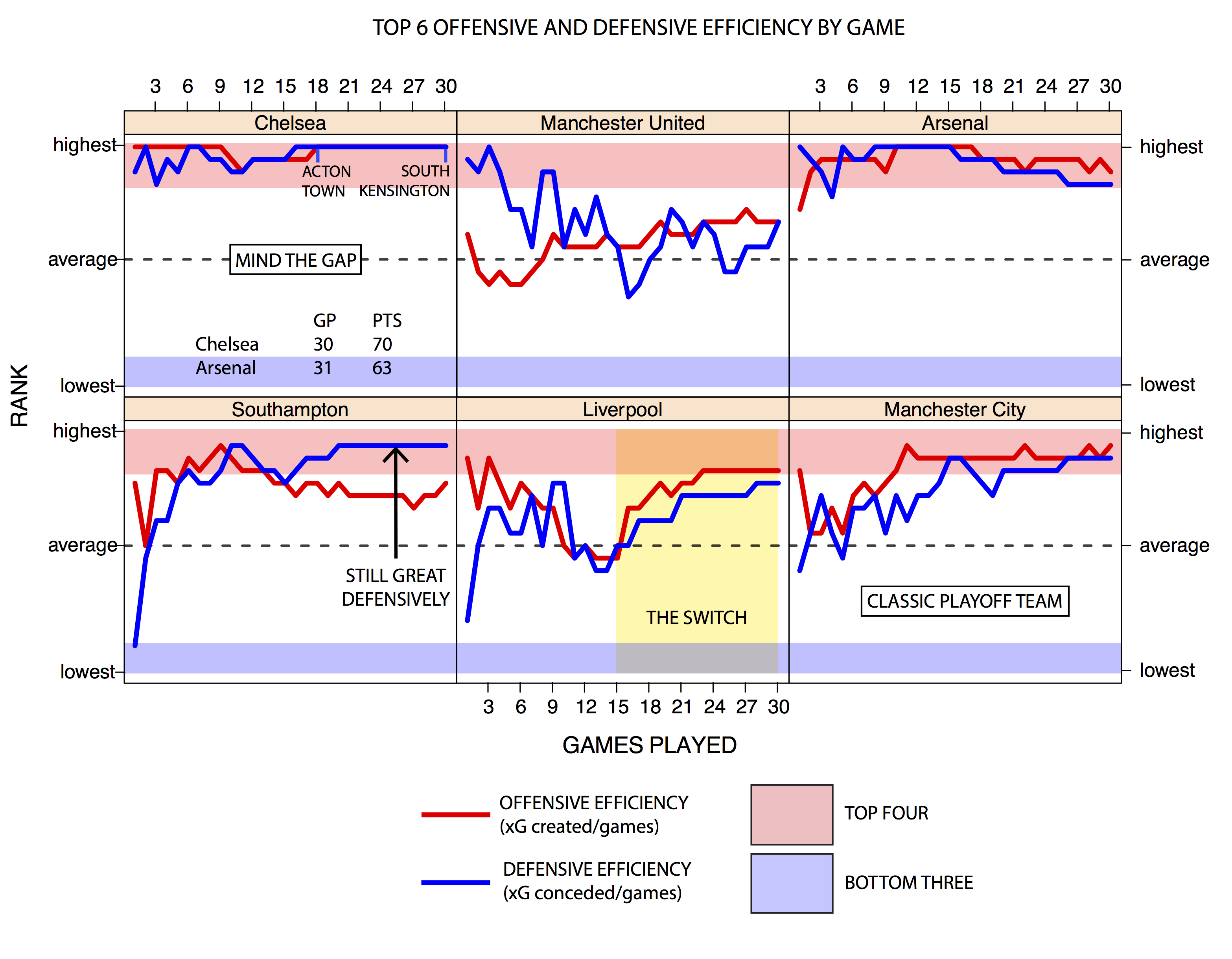

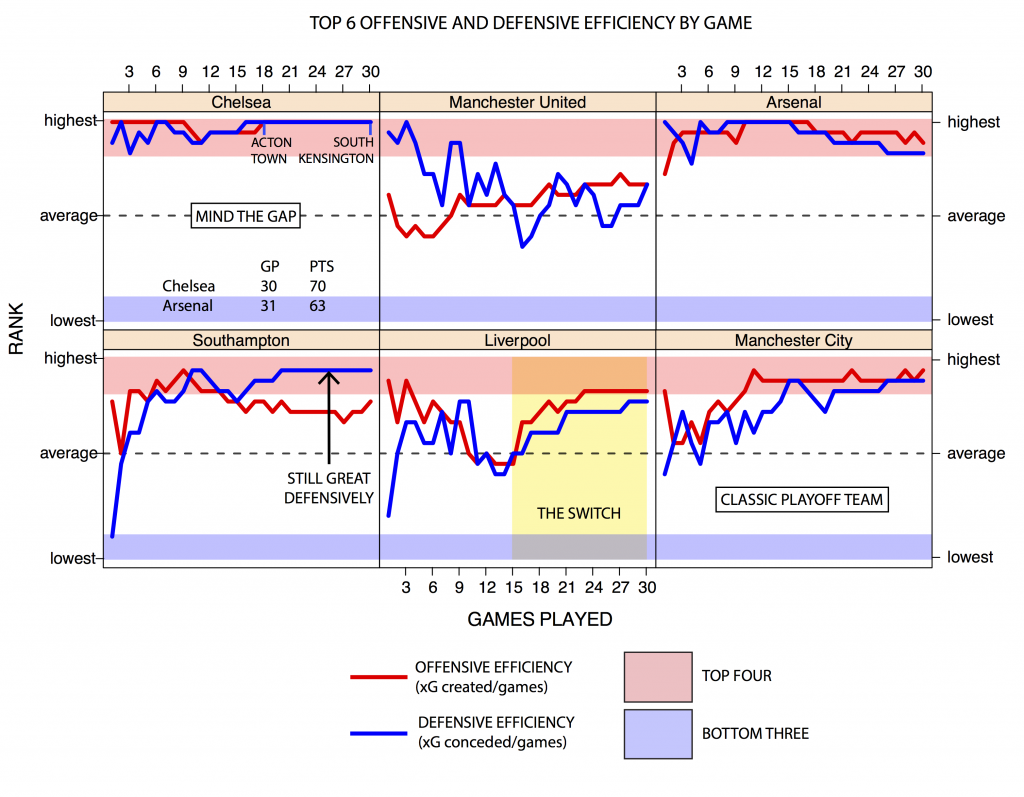

As was the case last time, these are offensive and defensive efficiency rankings for the Premier League teams. I’m defining offensive efficiency as xG created, divided by number of games played. So for example, if Man United created 10 xG in 5 games, its offensive efficiency would be 2.0 xG per game. Defensive efficiency is similar, but uses xG conceded instead of xG created. I’ve posted the big xG chart that ranks all the Premier League teams at the bottom, but for today, I’d like to focus on the best six teams of season so far. Thanks again to Michael Caley for providing me data from his ExpG model. So there you go. If you have any questions about my definitions or other things, please feel free to hit me up in the comments section.  Green Shoots Losses to Arsenal and Man United may have slowed Liverpool’s roll, but Brendan Rodgers’ side has re-established itself as a serious force after a sticky start to post-Suarez life. As has been well documented, Brendan Rodgers made a tactical switch mid-season by shifting the creative burden to Philippe Coutinho in a playmaking role behind the striker. I’ll leave the curation of a more detailed narrative to Michaels Caley and Cox, but since Coutinho’s Arrival (yes, capital ‘A’), the Reds’ offense has developed into the shifting, cutting monster that we all hoped was still possible after the Suarez transfer. Liverpool has gone from a middle of the pack offensive efficiency of 1.22 ExpG/game, to a dazzling 1.69 ExpG/game, which comes in just below Chelsea’s league-best mark. You can cut that with all the qualifiers you want, but allow me one of my own - that’s without a fully fit Daniel Sturridge, who was one of the 10 best players in the league last season. The efficiency chart also shows that Liverpool have improved defensively since ‘The Switch”. The change isn’t quite as dramatic as what happened on the offensive end, but the Reds have squirmed their way to respectability. At 1.06 xG conceded/game, they are the midpoint between elite and league average. It will be interesting to see whether Fenway Sports Group (FSG) will delve into the transfer market to bring in some more talent on the defensive end. Lucas is good, but struggles with injuries each season. Emre Can is a talented footballer who has played well at

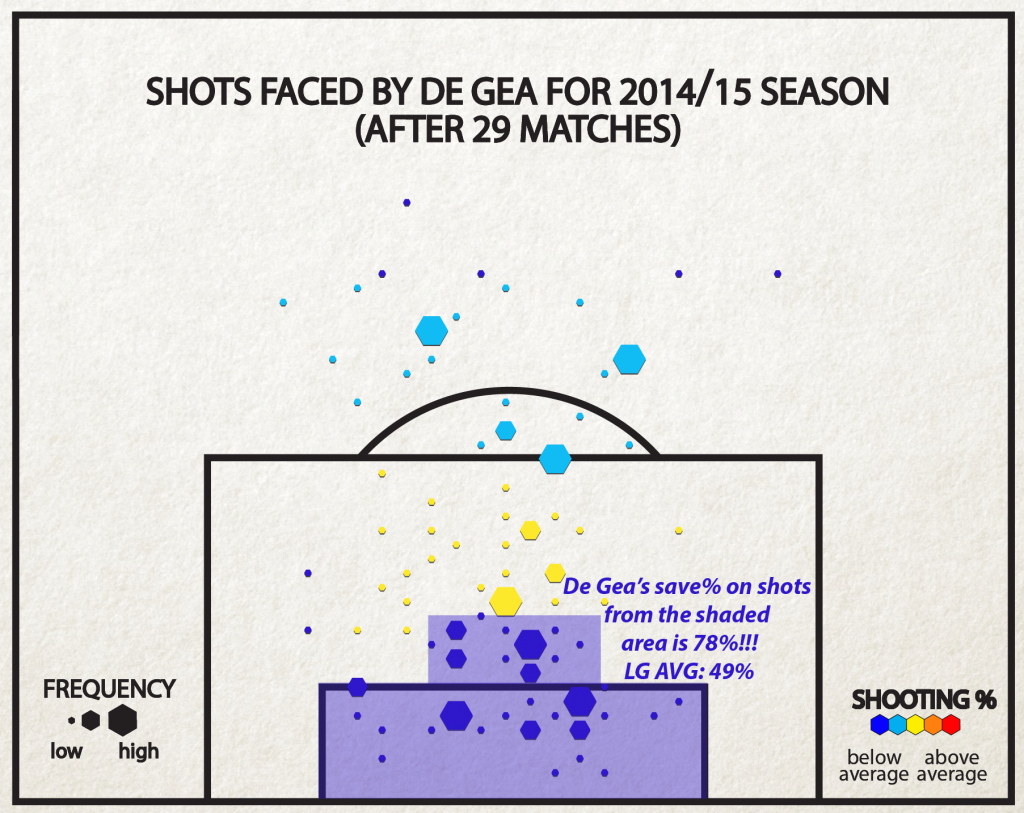

Green Shoots Losses to Arsenal and Man United may have slowed Liverpool’s roll, but Brendan Rodgers’ side has re-established itself as a serious force after a sticky start to post-Suarez life. As has been well documented, Brendan Rodgers made a tactical switch mid-season by shifting the creative burden to Philippe Coutinho in a playmaking role behind the striker. I’ll leave the curation of a more detailed narrative to Michaels Caley and Cox, but since Coutinho’s Arrival (yes, capital ‘A’), the Reds’ offense has developed into the shifting, cutting monster that we all hoped was still possible after the Suarez transfer. Liverpool has gone from a middle of the pack offensive efficiency of 1.22 ExpG/game, to a dazzling 1.69 ExpG/game, which comes in just below Chelsea’s league-best mark. You can cut that with all the qualifiers you want, but allow me one of my own - that’s without a fully fit Daniel Sturridge, who was one of the 10 best players in the league last season. The efficiency chart also shows that Liverpool have improved defensively since ‘The Switch”. The change isn’t quite as dramatic as what happened on the offensive end, but the Reds have squirmed their way to respectability. At 1.06 xG conceded/game, they are the midpoint between elite and league average. It will be interesting to see whether Fenway Sports Group (FSG) will delve into the transfer market to bring in some more talent on the defensive end. Lucas is good, but struggles with injuries each season. Emre Can is a talented footballer who has played well at left right back, but he got found out against Man United and might be better suited to a midfield role in the long term. There’s work to do, but this team is young, solid on both sides of the ball and has plenty of room to improve. It took a while, but this team has adjusted to life without Suarez and the future looks a lot rosier than it did even a few months ago. That’s why all this Sterling contract stuff sounds like hot air. FSG may have played hardball with Manny Ramirez back in the day, but this isn’t baseball. Football is just different, it’s a team sport and losing your most important player, which is what Raheem Sterling has become for Liverpool, will affect every facet of your team’s play. John Henry has recent, firsthand experience of what that’s like. This season’s reboot cost Liverpool Stevie G’s last chance at a title, Champion’s League qualification and years of Brendan Rodgers’ life! Why oh why would Henry have any interest in doing the same thing next season? King Louis It’s news to no one but your auntie, that Louis van Gaal and Ronald Koeman don’t like each other. This season, Koeman had the chance to deliver a body blow to his fellow Dutchman’s career, but he appears to have missed his opportunity. Think about it for a second. Last summer, van Gaal steered an unfancied Dutch team deep into the World Cup knockout stages. It was great news for the Oranje, but terrible news for the Red Devils, since it meant that Van Gaal took charge at the tail end of the preparation stages for the new season. He inherited a team that wasn’t so much ‘broken’ as not yet constructed. If you imagine Jose Mourinho starting this season at the head of a mutant crew sailing the Black Pearl, then spare a thought for Van Gaal who turned up at the docks ready to set sail, only to find a feverish Ed Woodward pointing excitedly at a bathtub filled with stacks of marginally different, mahogany Captains’ Wheels. By the time King Louis realized what he was working with, the only players available were overpriced and didn’t really fit into the scheme he intended on implementing. So he bought them anyway. For almost the entire season, Southampton has been a better team than Man United. The Saints pair elite defensive efficiency (0.96 xG conceded/game) with above average offensive performance (1.46 xG created/game). That’s good for an xG differential of 0.50 xG/game (1.46 – 0.96), or more than double Man United’s current xG differential of 0.21 xG/game. What we’ve seen unfold over the course this Man United season wasn’t a coaching masterclass, but a testament to the value of top class strikers and goalkeepers. Overtraining led to an injury crisis of biblical proportions and inflexible tactics meant long spells on the bench for some of the team’s most talented players. All season, Van Gaal’s team has been little more than above average on both sides of the ball. Yet with 7 games left, Man United sit comfortably among the Champion’s League places thanks to a sky high PDO (still the highest in the league according to @ObjectiveFooty’s ‘Main Table’). Despite the pedigree of some of their players, the Red Devils are rather Pulisian in the way they try to muck things up. Just like Pulis’ teams, they slow the game down; they don’t mind trading in attacking opportunities for solidity on the defensive end. This tactic works for Pulis, because his teams are usually underdogs. Slowing the pace down condenses the game, and a shorter game means a greater chance of a random outcome (e.g. that the lesser team gets a result). It works for Van Gaal because he’s willing to bet that in a game of few opportunities, his strikers and his goalkeeper will be more clinical in taking their chances than yours. And that is exactly what has happened. Wayne Rooney and Co. have scored 36.9% (again from @ObjectiveFooty) of their shots on target. That’s the best team scoring percentage in the league. Also best in the league is David de Gea’s 75.0% save rate. That’s impressive on it’s own, but things get really crazy when you look at where he’s saving shots from.  Shots on target from the shaded area are normally scored at a 51% clip, yet Man United’s opponents are converting these shots at a meager 22% (6 of 27). A league average keeper could reasonably be expected to concede 13 goals on that many shots from these areas – De Gea has conceded only 6. Clearly this is unsustainable; his save% from these areas close to goal is better than his save% from the other less dangerous areas. But it may not matter… Van Gaal’s men are 8 points clear of the chasing pack and look like a better side each passing week. This summer, King Louis will spend again, but this time, he’ll have time to pick his targets and an uncluttered offseason to mold his team’s identity. Had Southampton managed to clinch a Champions’ League spot, it might have been curtains for Van Gaal, as ownership grew skittish over the terms of team’s lucrative shirt sponsorship. Instead, it’s Koeman looking for answers ahead of Morgan Schneiderlein’s probable departure and, God forbid, the potential burden of Europa League qualification.

Shots on target from the shaded area are normally scored at a 51% clip, yet Man United’s opponents are converting these shots at a meager 22% (6 of 27). A league average keeper could reasonably be expected to concede 13 goals on that many shots from these areas – De Gea has conceded only 6. Clearly this is unsustainable; his save% from these areas close to goal is better than his save% from the other less dangerous areas. But it may not matter… Van Gaal’s men are 8 points clear of the chasing pack and look like a better side each passing week. This summer, King Louis will spend again, but this time, he’ll have time to pick his targets and an uncluttered offseason to mold his team’s identity. Had Southampton managed to clinch a Champions’ League spot, it might have been curtains for Van Gaal, as ownership grew skittish over the terms of team’s lucrative shirt sponsorship. Instead, it’s Koeman looking for answers ahead of Morgan Schneiderlein’s probable departure and, God forbid, the potential burden of Europa League qualification.

The Past is a Foreign Country; That’s Why It’s So Easy to Critique

When the facts have seeped out, when you’ve had time to think things through, it's all so obvious: Germany had the best, deepest squad in the tournament; Luis Suarez can make any manager look like a genius; and "c'mon, you never realised he was on 'roids?".

Haha! Totally joking about that last one... Totally. #GTL.

But some things defy explanation, they just sit there as you examine them, laughing back. Some things are like Manchester United’s final season under Alex Ferguson.

Okay, maybe I’m overstating it a little, but that 2012/13 season is a puzzle.

United cruised to the title, closing things out at Villa Park with a couple games to spare. RVP, Shrek and the Buoys clubbed together to score 82 goals in 38 games, gifting Alex Ferguson his 13th and final Premier League title.

So far, so good.

What's odd is that United posted the stats profile of a good, but certainly not great, team. Total Shot Ratio (TSR), usually a pretty good indicator of quality, ranked United in 8th place for the 12/13 season, sandwiched between Southampton and Newcastle. On its own that's not a game-changer, after all, TSR would have put Spurs atop the league that same season. But even Expected Goals (ExpG) models, which take into account more complex shot data like distance from goal and where the pass prior to the shot was played from were are flummoxed by how this version of United so drastically outperformed expectations.

Whatever Remains, However Improbable, Must Be the Truth?

That, apparently, is the opinion of Dan Altman.

"I computed the probabilities for the 2012-13 season... For Manchester United, the difference between expected goals and actual goals was sixteen. Without those sixteen goals, Manchester United probably would have finished fifth instead of first."

That's a quote from Altman's latest piece in the New Yorker on the same topic, in which he uses his bespoke shots model to break down exactly how United overachieved offensively.

His conclusion? Multi-dimensional luck (more or less)[1].

Luck on penalties and own goals. Luck on free-kicks and corners. And then some more luck converting chances in open play. He says that if you ran the season back in his shots model, United would be extraordinarily unlikely to score such a high number of goals again. In which case, the team probably wouldn’t have won the title, in which case, Alex Ferguson might not have been quite so quick to retire, in which case the world would be short a great wordsmith, (and Davey Moyes wouldn’t be aging in dog years).

Altman’s points are pretty convincing, especially in the light of how much United have struggled since then, but even he admits that the odds of this level of over-performance are pretty fracking long.

Which is why there might be a different answer. I’m not saying he’s wrong, but I think there’s an explanation that demands shorter odds.

Just In Case, Here’s What We’re Looking At

Usually, when I'm looking for an answer, it helps to take things down from the abstract clouds of ExpG models and put them into a form that’s more easy to understand.

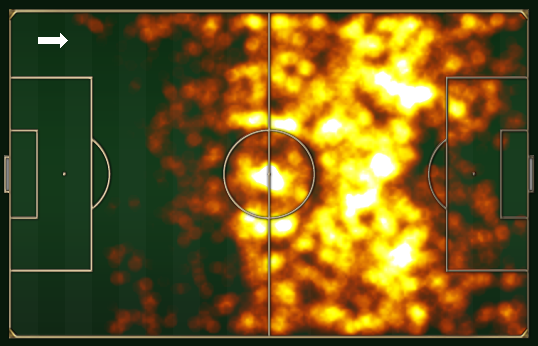

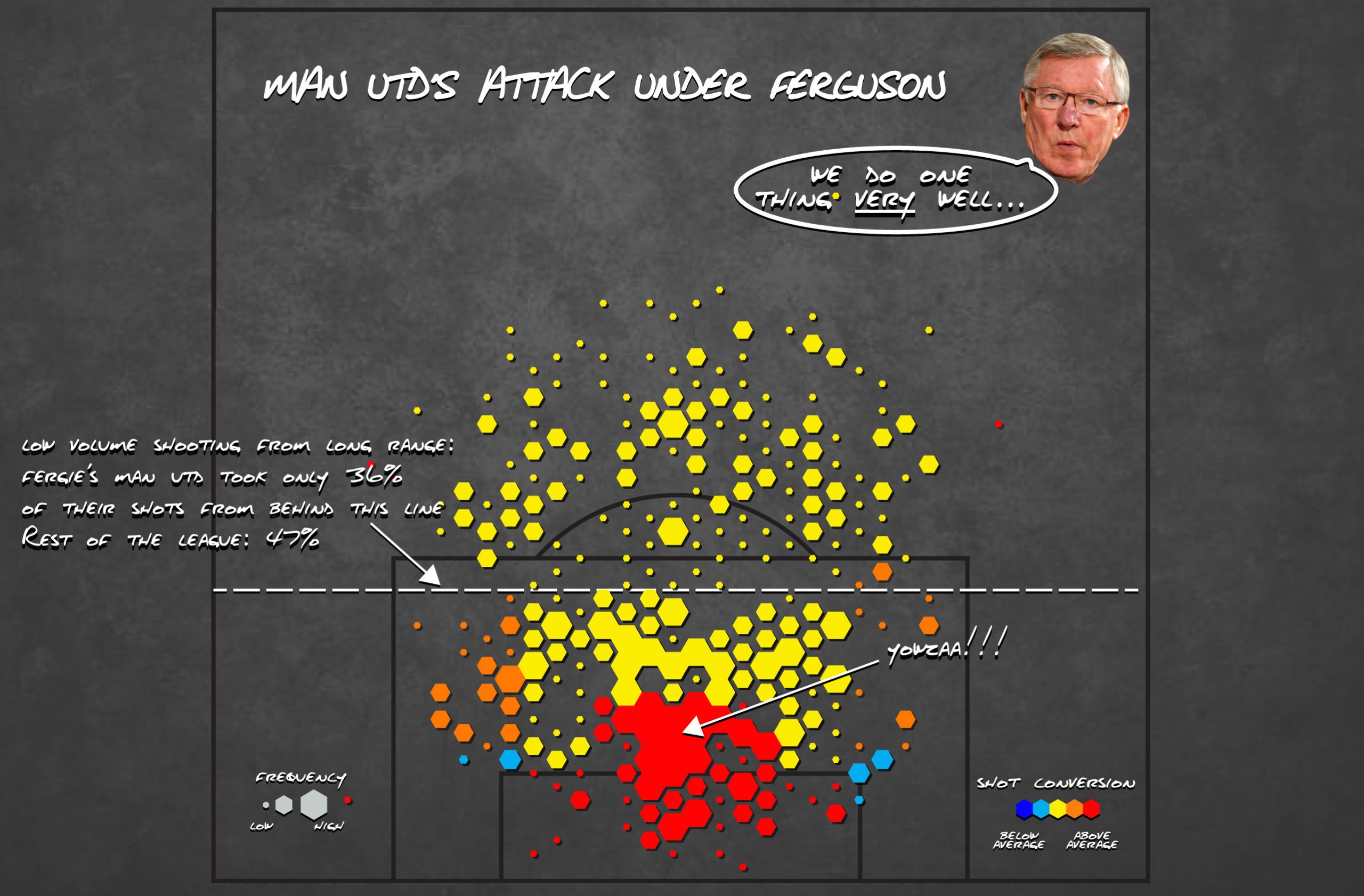

Here’s Man United’s shot chart from the 2012/13 season.

One thing is probably going to stick out to you - that big red clump with the YOWZA!!! annotation (or maybe you're a data hipster, in which case you're probably into the five light-blue hexs). When Altman says Man United overachieved their expected goal output, this is why. In Fergie’s last season, Man United took the juiciest shots in the game (close to and directly in front of goal) and squeezed, and squeezed, and squeezed some more. The shots in that bright red area were converted at roughly 13% above what you would expect the average Joe (Allen) to do with the same opportunities. By my calculations, based on the number of shots, that's worth somewhere between 17-18 goals over the course of the season.

(I swear I'm not making this up...)

Now, Marco Van Basten’s one hell of goal-scorer, but a) He retired in 1995, and b) He never played for United. Robin Van Persie did, but he's just one (non-superhuman) dude, and he didn’t take ALL of those shots…

At any rate, other than that one scorching zone, United are surprisingly average finishers – a couple points stronger on the wings, but nothing to write home about[2].

Hmmm…

You have to say, it doesn’t look completely random. It’s not like United are lights out from a bunch of unconnected areas. This is a team that is PHENOMENAL at scoring in one area.

Why? Well if you want answers this morning, you’re shit out of luck. I’m tired and I’m looking forward to the latest episode of Serial.

Tune in for part two tomorrow.

[1] I’m shortchanging Altman a little bit here. He also talks about things like RVP's finishing quality, but you can read it yourself, ‘cause, you know, the Internet.

[2] Interestingly, this version of United doesn’t shoot a lot from distance, which probably goes some way to explaining the low TSR numbers, if not the ExpG anomolies.

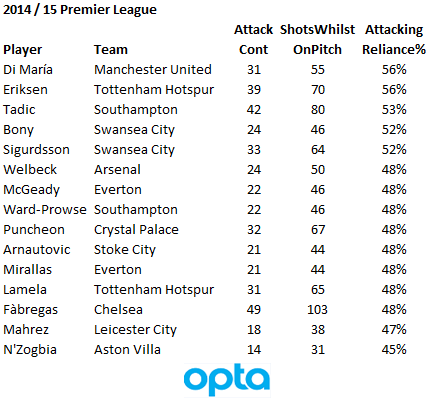

Short version: Angel Di María is the player that his club have relied upon most for his attacking contribution so far in this Premier League season.

Long version: Please read on

Many years ago the only individual player performance stats that we had access to were goal scoring records. Then someone decided it would be a neat idea to give credit to other attacking players and we began to also record the assists, ie the player that set up the goal. These stats are great, but as only approximately one in every ten shots is scored we inevitably lost a lot of detail as these performance counting stats only included the sample of shots that were scored. Why should the final shot from the striker influence whether or not the creative midfielder was awarded the assist or not for his through ball? To a large degree, the actual finish was outside of his control after all.

In relatively recent times things have improved for those that like to count things. Thanks to Opta (other brands may also be available) we now have a proliferation of sites that list the total number of shots and key passes that players make during each individual game and also cumulatively across a season. By stepping back one level from the old goal and assists metrics we can now credit players for their attacking output, regardless of the outcome of the final shot.

We know that not all shots are created equally, but given that there is a certain level of randomness in whether or not any individual shot actually results in a goal this increased level of transparency of individual attacking contribution can only be a good thing.

However, if we wish to accurately measure Attacking Contribution why stop at just the shot and the key pass? Doing so means that the player that played the penultimate pass gets no recognition at all, at least as far as the stats are concerned, and what about the player that made the pass preceding that?

Attacking Movements

Using detailed Opta event data I can join together the sequence of events for each shot that was taken and I can map out the complete attacking movement. These moves range in length from zero passes before the shot to the 51 event attacking move that Tottenham achieved against QPR earlier this season; a move that ended in a Nacer Chadli goal.

Using the information derived from these moves I want to have a go at creating a more comprehensive Attacking Contribution metric. This metric will go farther than counting just shots and key passes and can help us objectively measure the attacking importance of any individual player to their team. We have no need to just award “attacking points” to the shooter and the maker of the final pass. As with most of these metrics we’ll start with undertaking attacking analysis, as inevitably trying to analyse defensive contribution will be a much more difficult piece of work.

Data Rules

I needed to decide on a cut-off point in determining which actions to count in my Attacking Contribution metric. Although I want to go farther back in the chain than the guy who made the final pass, it is a tough sell to suggest that the player who made the 10th last pass in the move should receive credit for his part in the move. It’s an arbitrary cut-off but I decided to permit the final four attacking events in a move to contribute towards Attacking Contribution; this allows for the shot plus the previous three attacking events (pass, take-on or ball recovery).

For this measure I didn’t want to place different weightings on the extent of the involvement in any given attacking move. Very simply, if a player was involved in the final four attacking events in a move that led to a shot then they were awarded an Attacking Contribution. It is obviously possible for a player to be involved more than once in a move, ie they play a one two before taking the shot, but each player was only awarded one Attacking Contribution per move. After all, I simply want to measure how many moves each player could be said to have been involved in.

I am conscious that this analysis can only use the data that I have access to. Although the Opta event data is very detailed it only covers “on the ball” actions, which will be fine for 95% of this analysis. However, it will be unaware of the player that made the step over that sent the defender the wrong way or the supporting forward who made the unselfish run to pull the defenders out of their shape. I don’t imagine that these “oversights” will significantly impact on the findings in this analysis but I wanted to address that point now.

The premise of this metric is that it shouldn't just be the shooter and the player that makes the final pass that receives Attacking Contribution credit, as is currently the case.

This post will serve as an introduction to my Attacking Contribution method; I have a few ideas related to this metric that I would like to tease out and analyse in the near future but I’ve got to start somewhere and I’ll keep the numbers in this piece fairly simple.

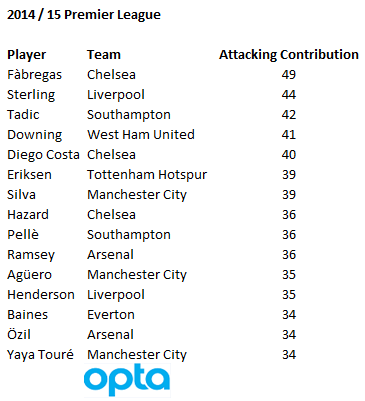

2014 Premier League Attacking Contribution

As a means of illustrating and working through this metric let’s look at the first seven games of the 2014/15 Barclays Premier League.

Here are the 15 players that have had the greatest Attacking Contribution in absolute terms:

With 22 key passes and 7 assists it’ll not surprise anyone to see that Cesc Fabregas has been the player that has had the highest Attacking Contribution during the opening seven game weeks of this new season. By looking at the total number of minutes that each player has played we can convert these values to Attacking Contributions per90, this method of normalisation means we can easily compare players regardless of time spent on the pitch. However, I'm not going to dwell on this aspect right now.

What I do want to spend some time on is describing how I see this metric being most useful: Which player contributes most to their teams’ shots?

Attacking Reliance

To assess the attacking impact that a player has I looked at their individual Attacking Contribution numbers as a proportion of the total shots that their team had while they were on the pitch. By doing this I’m not actually trying to measure the effect that a player has on their team’s attacking output, ie if the player was missing I’m not suggesting that his team would see their shots total drop by x shots. Instead, I am quantifying the proportion of shots a team takes that goes through the player, in other words it looks at to what extent a team relies on a player. How much of a team’s attacking game revolves around player X or player Y?

In this analysis I used a cut-off of 50% of minutes - a player has needed to be on the pitch for at least 315 minutes so far this season.

By dividing a player’s Attacking Contribution by the number of shots his team took whilst he was on the pitch I then arrive at an Attacking Reliance %. This Attacking Reliance percentage informs us of the proportion of attacks that the player is involved in (as defined by the final four attacking events of the move) or how much their team has relied on them in an attacking sense. The table in descending order of Attacking Reliance% currently appears as:

Now we get a different looking table, and one that seems to make sense. Fabregas has the highest absolute Attacking Contribution value, but despite his sublime performances Chelsea have had a sufficient volume of shots for them not to be overly reliant on the Spaniard.

High Reliance Players

We can see that even though he has only been with Man United for a very short period of time Angel Di Maria is having a hugely important contribution to their attacking output with an Attacking Reliance figure of 56%. Compare that with United’s other big name signing / loanee Falcao; even if I set aside the 50% minutes rule in this data set he still wouldn’t appear in this list. The Colombian striker has been involved in just 40% of United’s attacking moves. Given his price tag he’ll want to be quickly increasing that value.

The reliance that United has had on Di Maria is the highest in the league, just pipping Christian Eriksen who himself posts a rounded Attacking Reliance value of 56%. Despite struggling and appearing to be out of favour for large parts of his first year as a Tottenham player, the Danish attacking midfielder is now showing everyone his true worth. In fairness, it’s worth pointing out that some analysts were ahead of the curve on his ability.

Ted concluded that piece with “This might be controversial, but based on the rarity of that type of performance and how he’s performed over his career, Christian Eriksen is quite possibly one of the best attacking passers in the Premier League already”.

Although Graziano Pelle has received the majority of the plaudits down on the South coast it is interesting to see that Dusan Tadic actually has had a greater involvement in Southampton’s attacking moves than the Italian striker. In fact, even James Ward-Prowse has a higher Attacking Reliance value than Pelle, who for the record has posted a value of 42%.

Swansea’s twin attacking threat of Gylfi Sigurdsson and Bony complete the list of players that posted an Attacking Reliance value of greater than 50%. So all a team has to do to stop Swansea is to stop Gyfli and Bony. Why did no one say that before? (insert sarcastic emoticon)

It is unusual for a team to have two players with such high Reliance values, but obviously these things happen so early in the season with a team that has had the second lowest number of shots in the league. In North London, Danny Welbeck will be pleased with his start to life as an Arsenal player with his involvement in 48% of Arsenal’s shots that have occurred while he has been on the pitch.

One other player that is worth mentioning is Riyad Mahrez of Leicester. He has played just shy of 400 minutes this season, but more shots have gone through him while he has been on the pitch than any of the other Leicester players, including better known players such as Jamie Vardy and Leonardo Ulloa.

Wrap-up

An Attacking Reliance figure for any individual player of 50% is massive, at least in Premier League terms. Over the last four full seasons only eight players achieved a value of this scale over the full 38 game season (and no, I’m not going to name them today, remember I said this was just an introductory article to the concept).

I’ve said it many times before, but one of the aims of my analytical work is to be able to objectively measure what our eyes see. In this regard, analytics won’t always provide ground breaking findings but it will allow us to quantifiably assess certain impacts, which may in turn, be used as inputs in subsequent applied research. This introductory analysis falls into this category.

In future articles I intend to undertake further analysis so we can see if we can learn anything more from Attacking Reliance figures.

Does a high reliance on individual players effect how successful a team is?

Does it matter if players with a high Attacking Reliance value leave the club?

Do we even have enough examples to be able to test this?

At this stage I don't have the answers to the above questions, but I hope that’ll change in the near future.

Most everyone reading this will be aware of the Player Radars that Ted has been producing, both here and on his Twitter feed, over the last 6 months. The radars are a great way to get a feel for a player simply by using a dozen high level stats and it also allows you to get a grasp for the likely attributes of a player even if you have never seen them playing before.

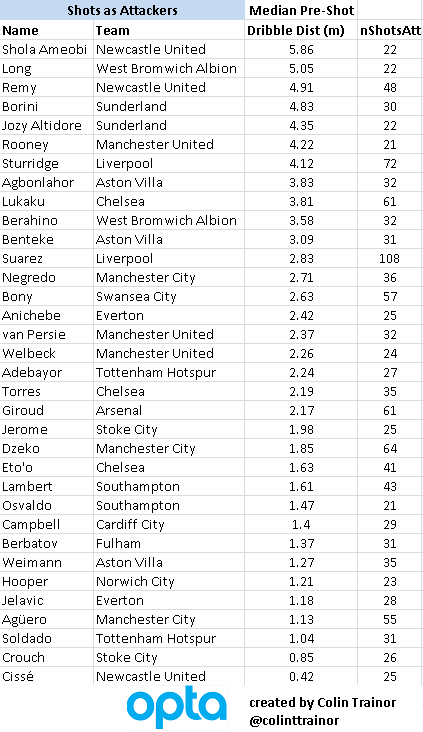

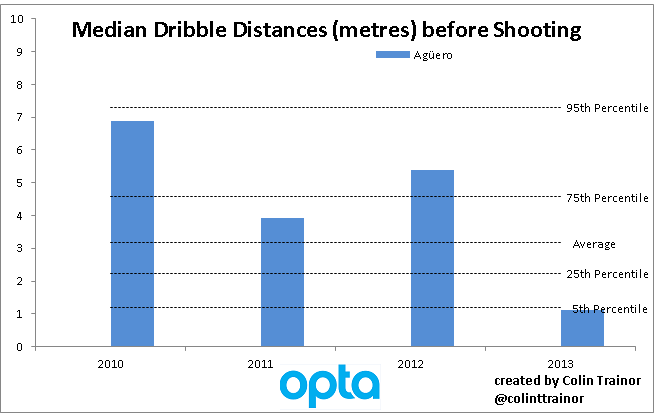

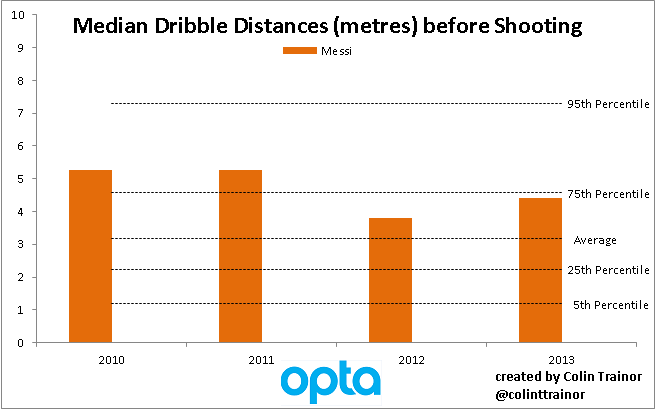

How to distinguish different types of strikers?

Data can be, and I’m quite sure is being, used to help filter the number of potential forwards that a club may be interested in. The data that is easiest to gain access to is the widely published totals like number of shots and conversion rates; or other outcome orientated metrics. Of course, I am a big fan of these “counting metrics”, but I believe it is also possible to understand certain stylistic traits of players from the detail event data that Opta collects. As well as helping inform the football fan, this information could also form part of a club’s recruitment and initial selection process, thus narrowing down the potential number of acquisition targets before a scout has even personally laid eyes on the player in question.

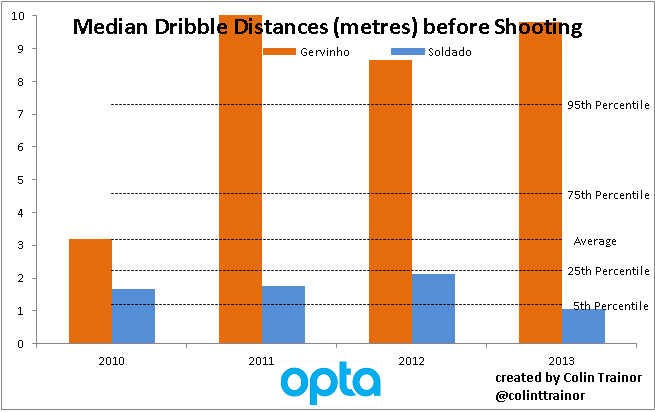

What stylistic metrics could we use? 1 - Expected Goal values