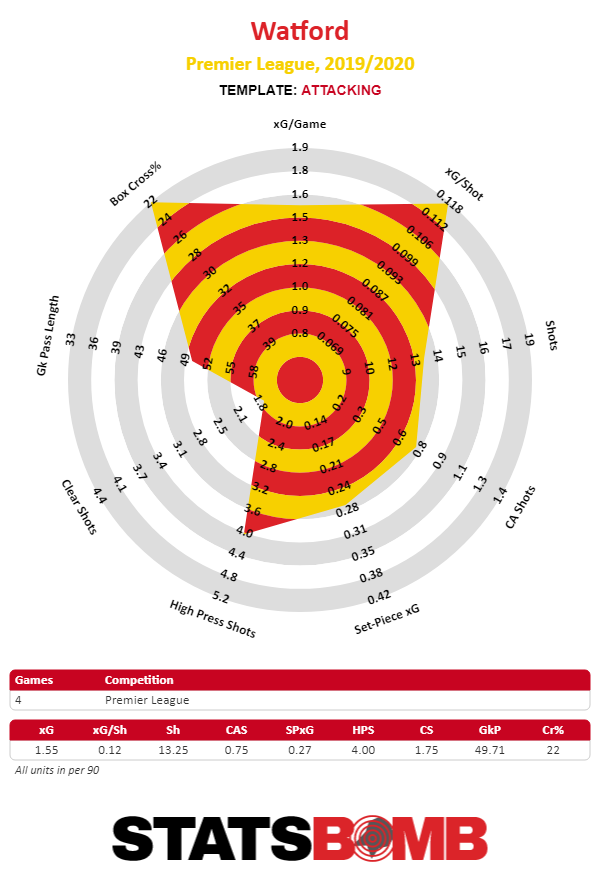

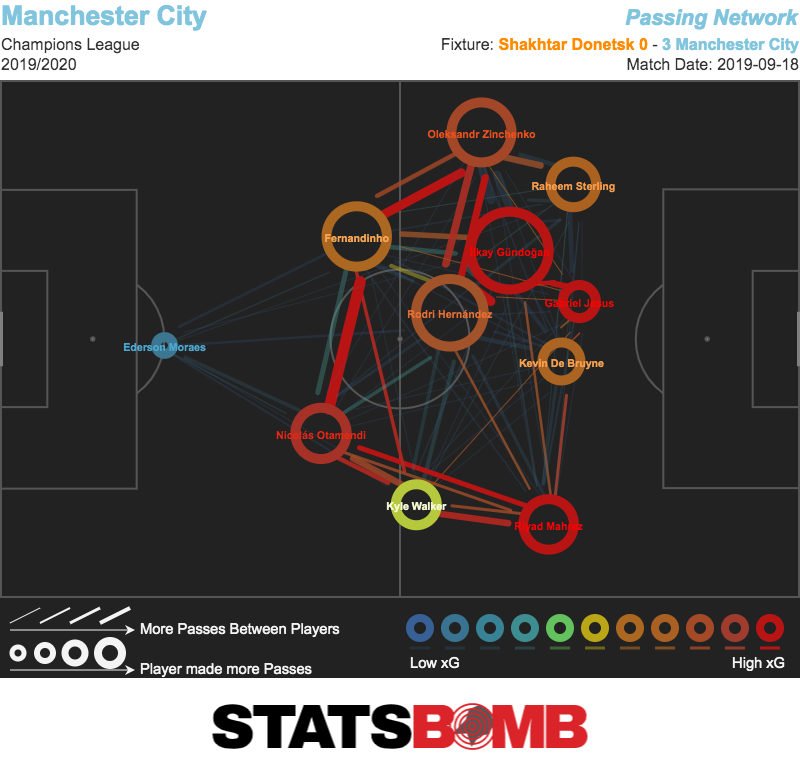

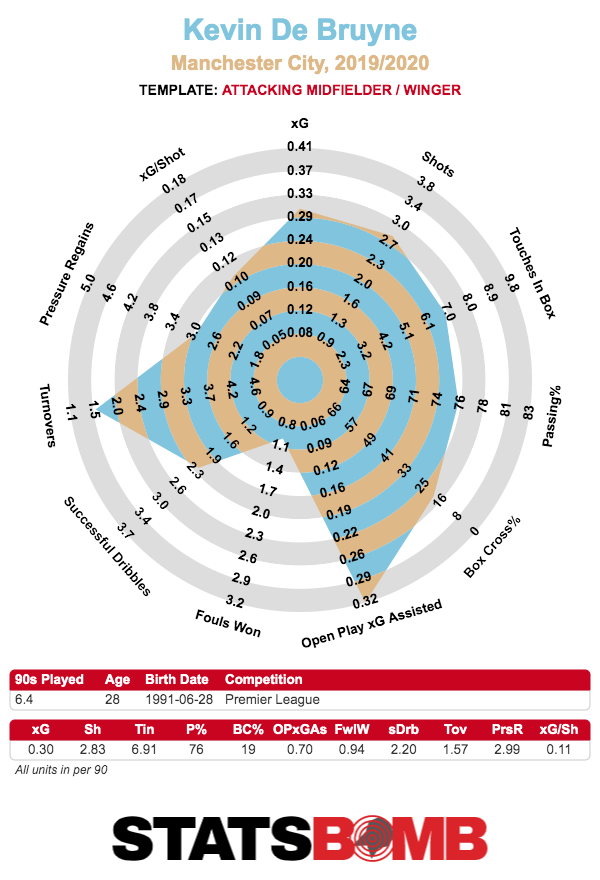

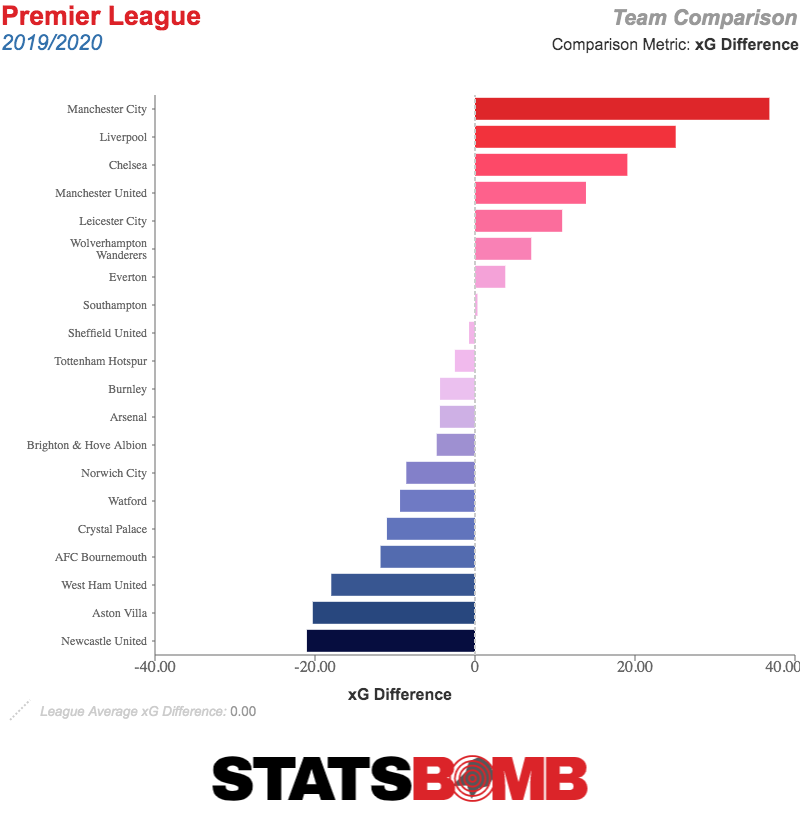

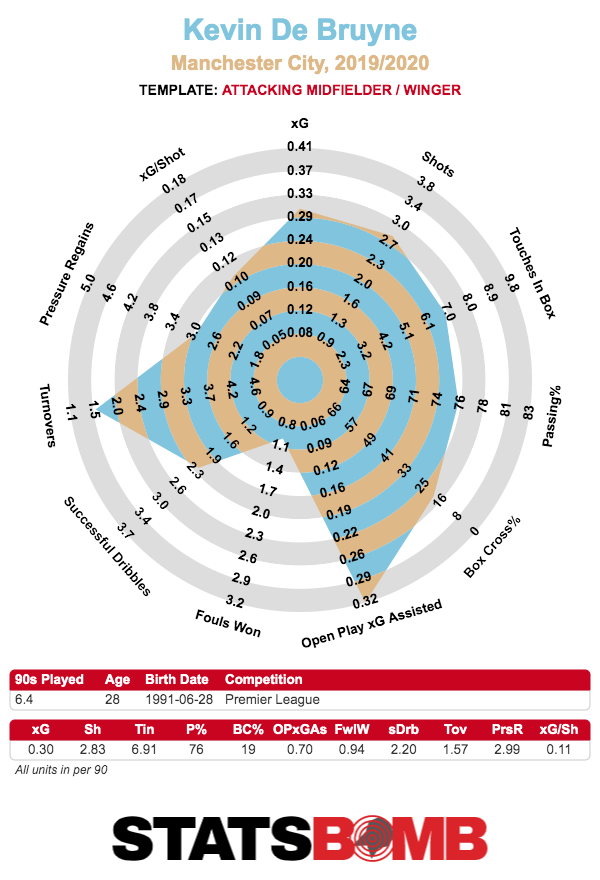

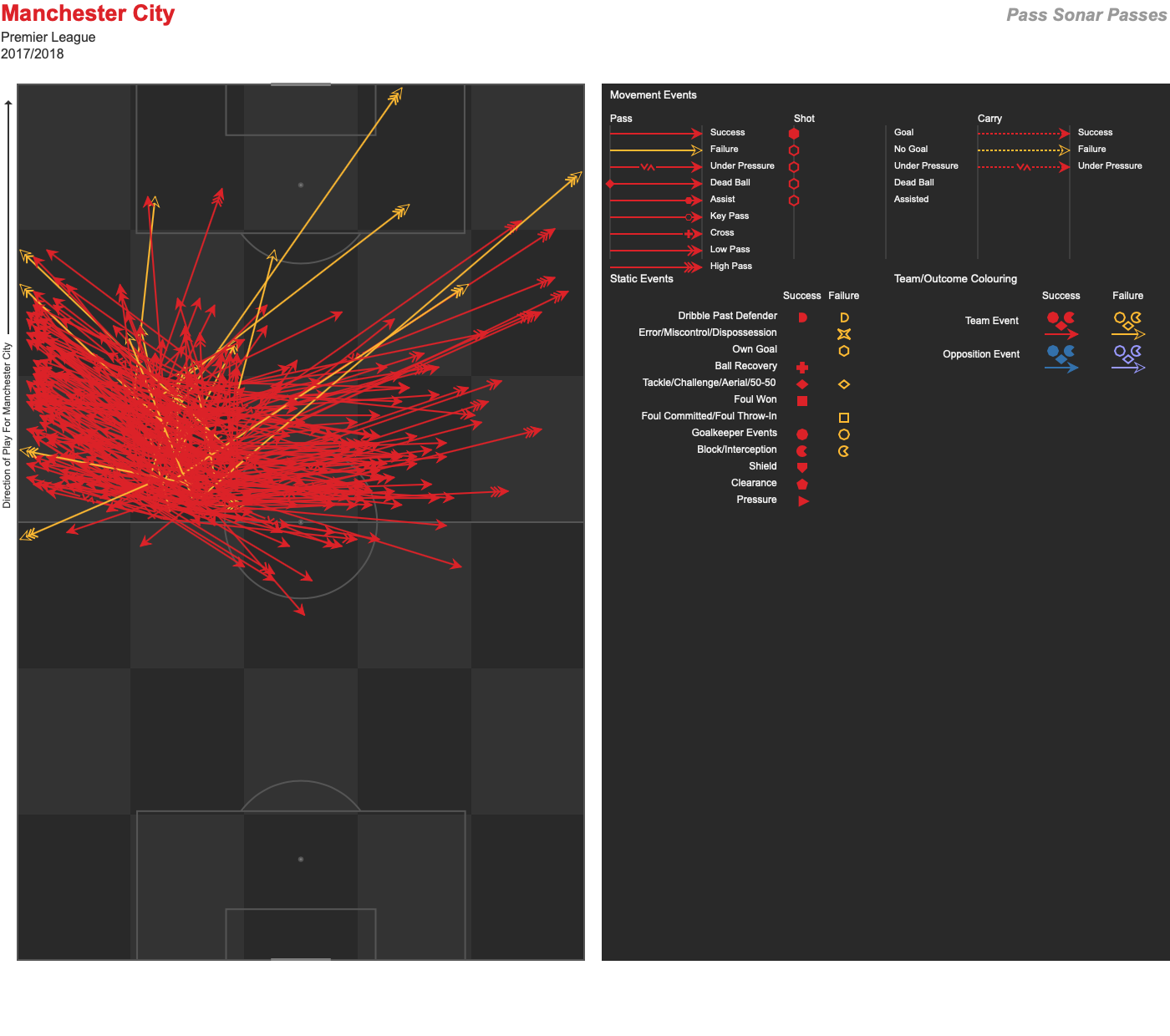

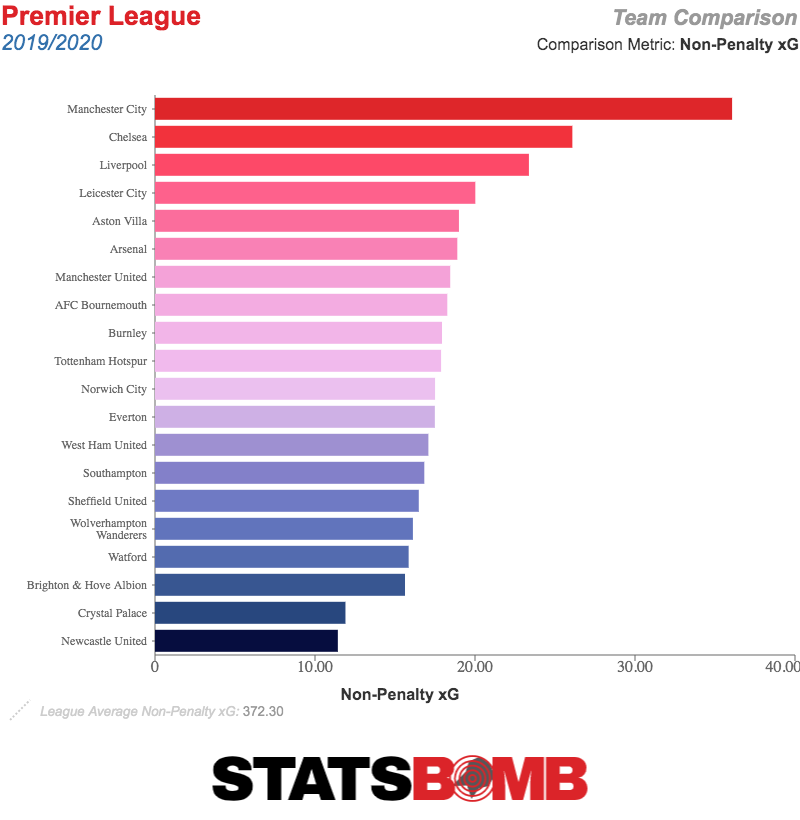

Are there real problems here? For the previous two years, Manchester City have been as close to perfect as we have ever seen in the Premier League. 198 points, 201 goals scored, 50 conceded across 76 games is as good as it’s ever been in England’s top flight. This is the pinnacle. So it’s perhaps inevitable that even a minor dip in performance gets scrutinised to death. But, nevertheless, scrutinise we shall, and there are real concerns about this City side that did not exist in previous years. On the attacking end, it looks fine. More than fine, in fact. The 2.87 expected goals per game is better than ever. While in previous years things were more balanced, it seems as though Pep Guardiola has tweaked his system to really allow Kevin De Bruyne to do his thing. With David Silva at age 33 becoming more of a rotation option than one of the first names on the teamsheet, City have experimented with pushing De Bruyne into a more advanced role as a number ten in which he, at times, seems to be pushed up right alongside the striker. Against Shakhtar Donetsk, for example, the passmap shows him just as advanced as Gabriel Jesus, with City really looking like a 4-2-4 in possession.  The one significant time Guardiola employed this tactic in his career was a stretch in in early 2010, when he was attempting to move Lionel Messi into a more central role but still felt the need for a “proper” striker, with Messi fielded as a number ten who could take up centre forward positions. That De Bruyne has been given a role once created for Messi is obviously a great credit to the Belgian, and he’s really thriving in it. He might be touching the ball in very advanced areas, but he’s still unquestionably a playmaker, and his 0.7 open play xG assisted per 90 is defying all known logic. On these grounds, it’s forgivable that City’s attack stuttered against Wolves when everything has been funnelled towards one man who wasn’t available.

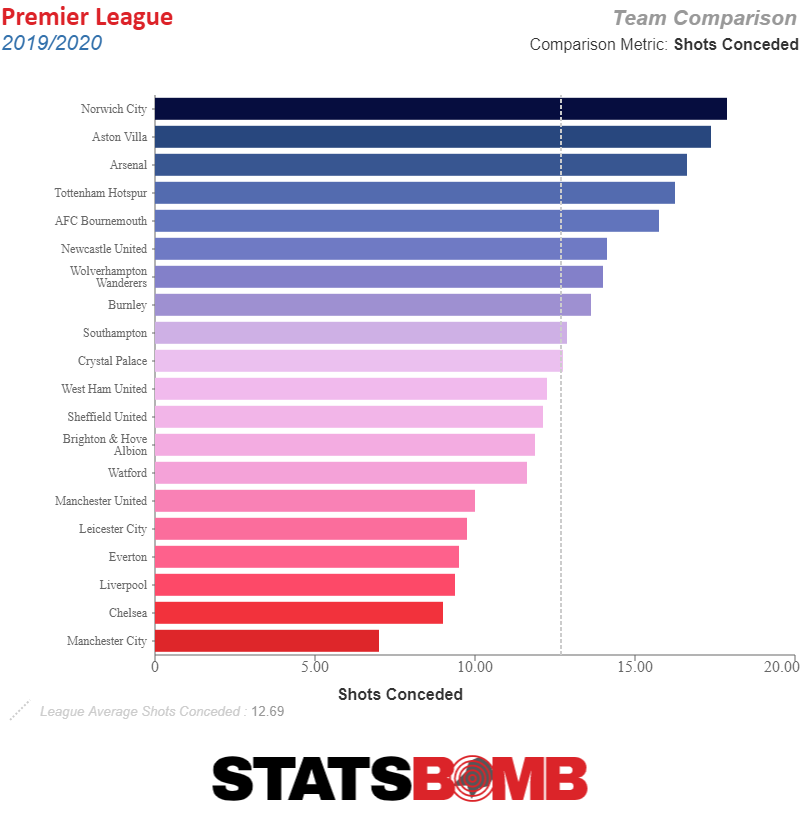

The one significant time Guardiola employed this tactic in his career was a stretch in in early 2010, when he was attempting to move Lionel Messi into a more central role but still felt the need for a “proper” striker, with Messi fielded as a number ten who could take up centre forward positions. That De Bruyne has been given a role once created for Messi is obviously a great credit to the Belgian, and he’s really thriving in it. He might be touching the ball in very advanced areas, but he’s still unquestionably a playmaker, and his 0.7 open play xG assisted per 90 is defying all known logic. On these grounds, it’s forgivable that City’s attack stuttered against Wolves when everything has been funnelled towards one man who wasn’t available.  It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that the real concerns, however, are on the defensive side. Nine goals conceded in eight matches is obviously a sharp rise from the 0.6 goals against per game of last season, but is it just a weird finishing run? When looking at the raw shot counts, it seems that way. City are allowing seven shots against per game, just a fraction worse than last season’s 6.29 and still, as usual, the best in the league.

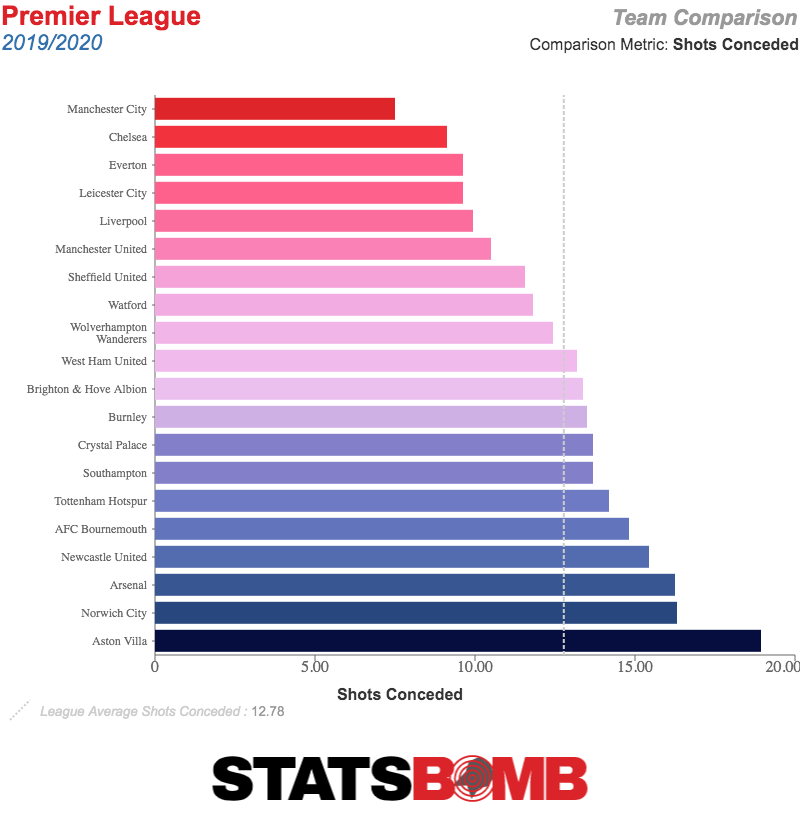

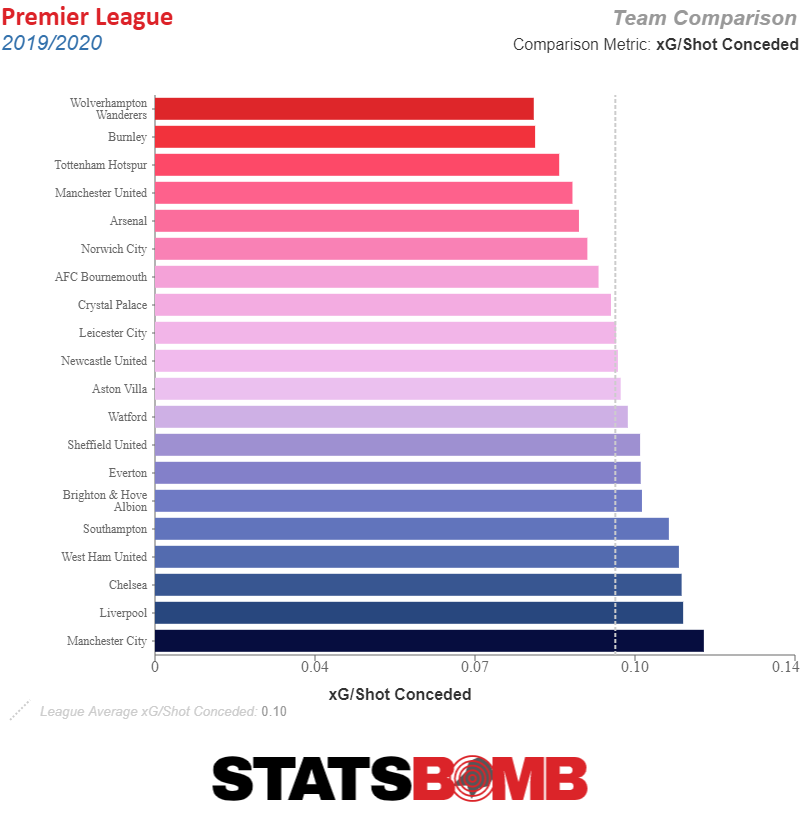

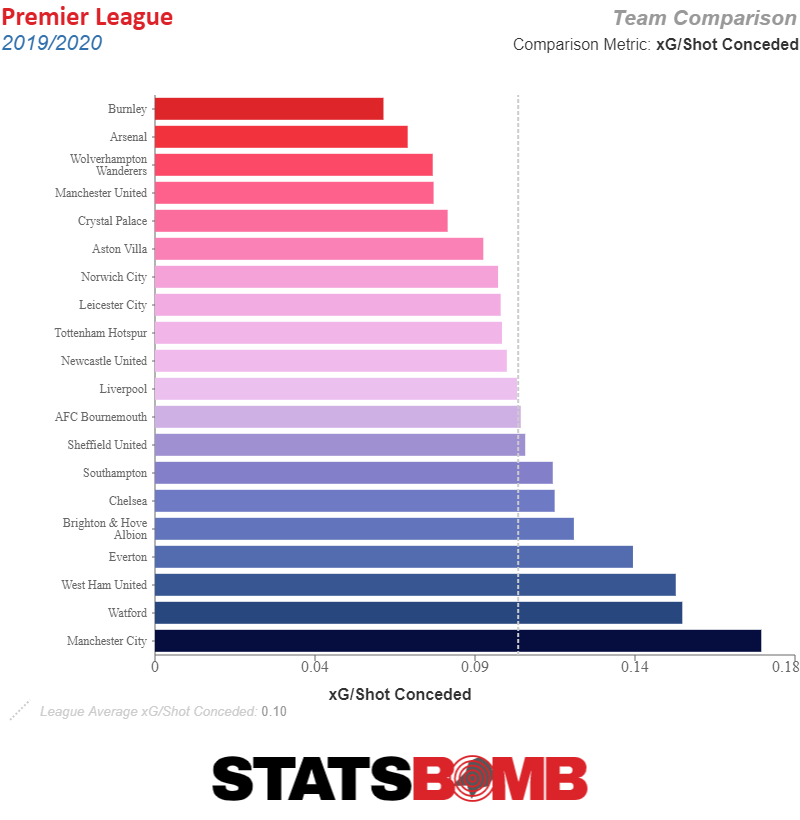

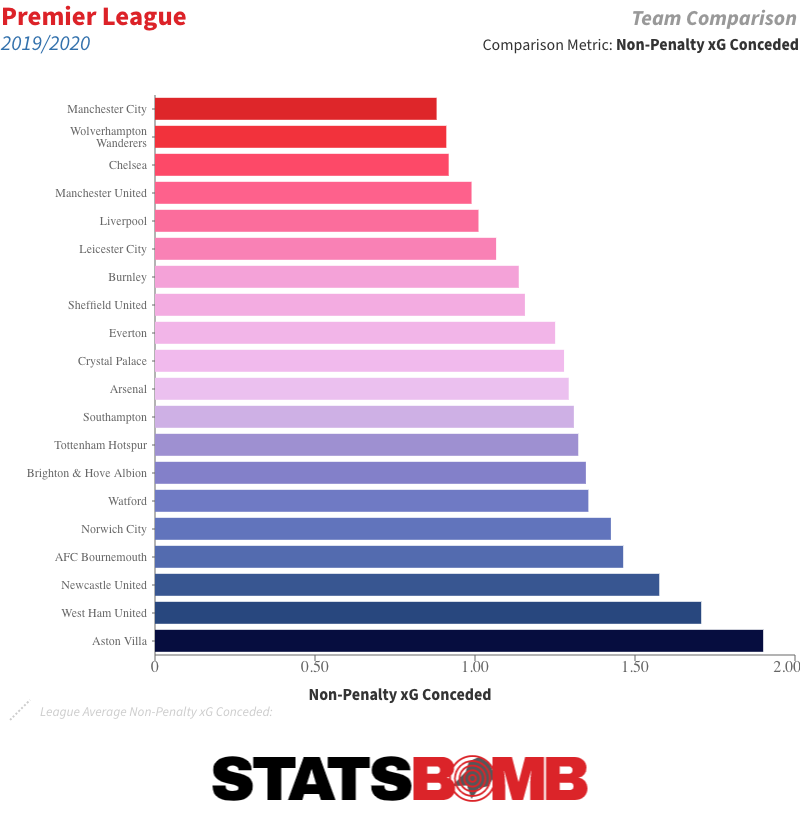

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that the real concerns, however, are on the defensive side. Nine goals conceded in eight matches is obviously a sharp rise from the 0.6 goals against per game of last season, but is it just a weird finishing run? When looking at the raw shot counts, it seems that way. City are allowing seven shots against per game, just a fraction worse than last season’s 6.29 and still, as usual, the best in the league.  Of course shot volume doesn’t tell the whole story. The reason we have expected goals models is to find the outstanding cases where shot quality is playing a decisive role. And here’s where things get worrying. Last season, City had an xG per shot conceded of 0.09, around league average. This isn’t how a side that presses the ball as high up the pitch as City would typically operate. The point of a high press is that you limit the number of shots your opponent is able to take. The risk, though, is that once the opposition breaks your press, you’re badly exposed, and they can carve out an excellent scoring opportunity. That this team could press opponents so hard to concede the fewest shots in the league while also making sure those shots were only of middling quality seemed like genuine magic. And this is where we find the leak. City’s xG per shot conceded this season is 0.17, nearly double that of last year and the worst in the Premier League.

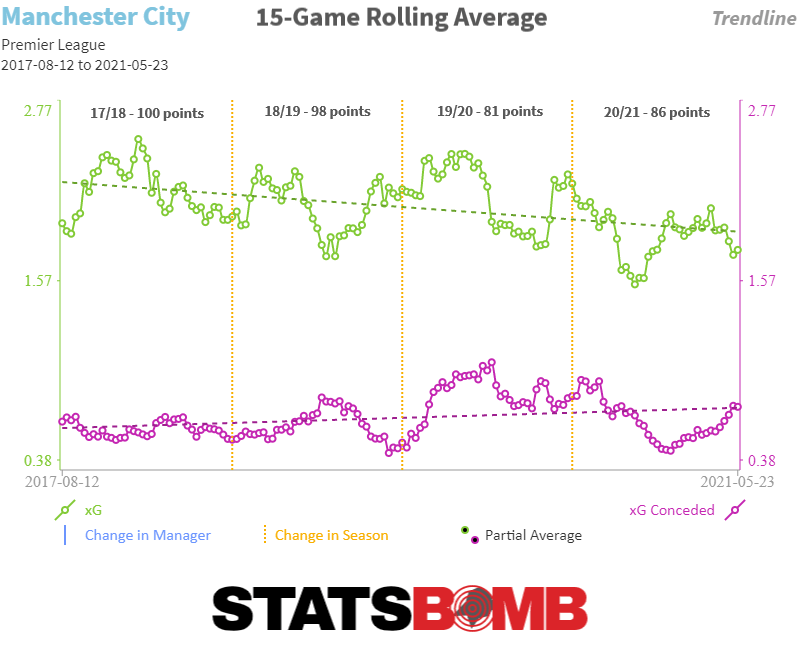

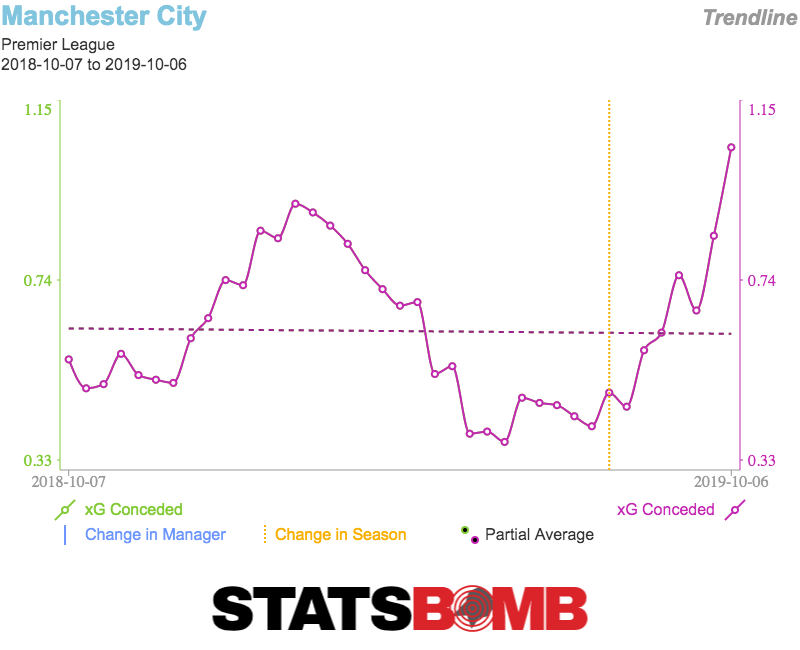

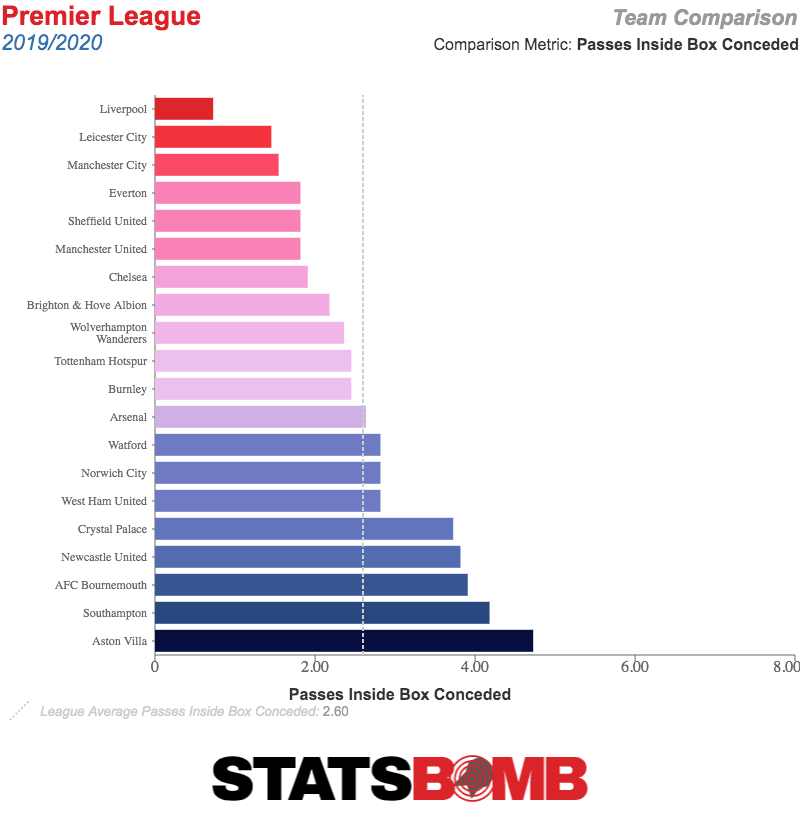

Of course shot volume doesn’t tell the whole story. The reason we have expected goals models is to find the outstanding cases where shot quality is playing a decisive role. And here’s where things get worrying. Last season, City had an xG per shot conceded of 0.09, around league average. This isn’t how a side that presses the ball as high up the pitch as City would typically operate. The point of a high press is that you limit the number of shots your opponent is able to take. The risk, though, is that once the opposition breaks your press, you’re badly exposed, and they can carve out an excellent scoring opportunity. That this team could press opponents so hard to concede the fewest shots in the league while also making sure those shots were only of middling quality seemed like genuine magic. And this is where we find the leak. City’s xG per shot conceded this season is 0.17, nearly double that of last year and the worst in the Premier League.  City concede the second fewest deep completions in the league and the second fewest opponent passes inside their own box. Teams still find it awfully difficult to get the ball up the pitch against Guardiola’s side and generate shots. But, once they do work it into dangerous areas, it seems to be easier than ever to turn those situations into good chances. They are about level in terms of goals conceded vs expected, having let in nine against an xG of 9.74. But this looks worse when you factor in post-shot information. City have needed Ederson to bail them out at times and he is delivering, saving nearly two goals more than expected on the post-shot model. Most likely, this just means that opposing players have happened to strike the ball well and Ederson stepped up to the plate. But it might be conceivable that the chances City are conceding could be of even higher quality than the pre-shot model thinks, and the post-shot data is picking up on something that’s happening. It’s not an accident that City have the defensive issues one would expect of a high pressing side with some problems. When looking at the team’s defensive distance, the average location up the pitch where they attempt a defensive action, it shows that City are pressing higher than ever. In fact, City have been gradually defending further and further up the pitch for the past twelve months.

City concede the second fewest deep completions in the league and the second fewest opponent passes inside their own box. Teams still find it awfully difficult to get the ball up the pitch against Guardiola’s side and generate shots. But, once they do work it into dangerous areas, it seems to be easier than ever to turn those situations into good chances. They are about level in terms of goals conceded vs expected, having let in nine against an xG of 9.74. But this looks worse when you factor in post-shot information. City have needed Ederson to bail them out at times and he is delivering, saving nearly two goals more than expected on the post-shot model. Most likely, this just means that opposing players have happened to strike the ball well and Ederson stepped up to the plate. But it might be conceivable that the chances City are conceding could be of even higher quality than the pre-shot model thinks, and the post-shot data is picking up on something that’s happening. It’s not an accident that City have the defensive issues one would expect of a high pressing side with some problems. When looking at the team’s defensive distance, the average location up the pitch where they attempt a defensive action, it shows that City are pressing higher than ever. In fact, City have been gradually defending further and further up the pitch for the past twelve months.  This wasn’t causing the side defensive issues until very recently. Perhaps they recently took it a little too far and the dam broke, or perhaps the issue lies somewhere else.

This wasn’t causing the side defensive issues until very recently. Perhaps they recently took it a little too far and the dam broke, or perhaps the issue lies somewhere else.  So the question comes to personnel. The one significant arrival to the team (sorry, João Cancelo, but you’re going to have to play more football before you count here) was Rodri as the “Fernandinho replacement”. Purely in terms of defensive output, there doesn’t seem to be an issue here.

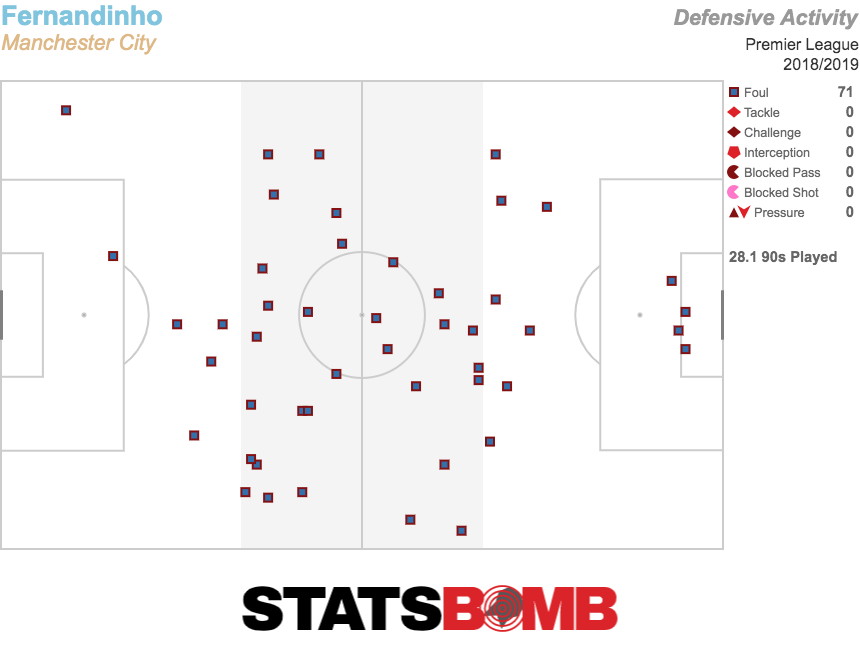

So the question comes to personnel. The one significant arrival to the team (sorry, João Cancelo, but you’re going to have to play more football before you count here) was Rodri as the “Fernandinho replacement”. Purely in terms of defensive output, there doesn’t seem to be an issue here.  The dirty little not-so-secret about Fernandinho’s role for City has always been his tactical fouling, and purely in the numbers, it seems fine here. Rodri is making 2.82 fouls per 90, more than Fernandinho’s rate of 2.52 last season. But there are some differences we can observe in location. These are all of the Brazilian’s fouls last year. The obvious thing that stands out is that the vast majority were in the middle third of the pitch, with a good chunk in the opposition’s final third, and relatively few in his own defensive third.

The dirty little not-so-secret about Fernandinho’s role for City has always been his tactical fouling, and purely in the numbers, it seems fine here. Rodri is making 2.82 fouls per 90, more than Fernandinho’s rate of 2.52 last season. But there are some differences we can observe in location. These are all of the Brazilian’s fouls last year. The obvious thing that stands out is that the vast majority were in the middle third of the pitch, with a good chunk in the opposition’s final third, and relatively few in his own defensive third.  Now here are Rodri’s this season. Despite playing only a fraction of the minutes, he’s nearly made as many fouls in his own defensive third as Fernandinho did in all of last year. Are these “tactical” fouls, or simply fouls that you don’t want to give away? It’s not obvious.

Now here are Rodri’s this season. Despite playing only a fraction of the minutes, he’s nearly made as many fouls in his own defensive third as Fernandinho did in all of last year. Are these “tactical” fouls, or simply fouls that you don’t want to give away? It’s not obvious.  One thing Rodri perhaps lacks in the role is mobility. This might be part of Guardiola’s thinking in the new shape, putting Ilkay Gündoğan alongside the Spaniard in a double pivot, giving him some assistance and lessening the size of the area in which he needs to offer defensive cover. It’s not clear what exactly Gündoğan is offering in this regard. He isn’t a particularly aggressive ball winner. He’s not a tactical fouler, making less than one foul per 90. And he’s not especially adventurous in his passing. If adding him into a double pivot clearly isn’t making the side more stable, what is the point of him being there?

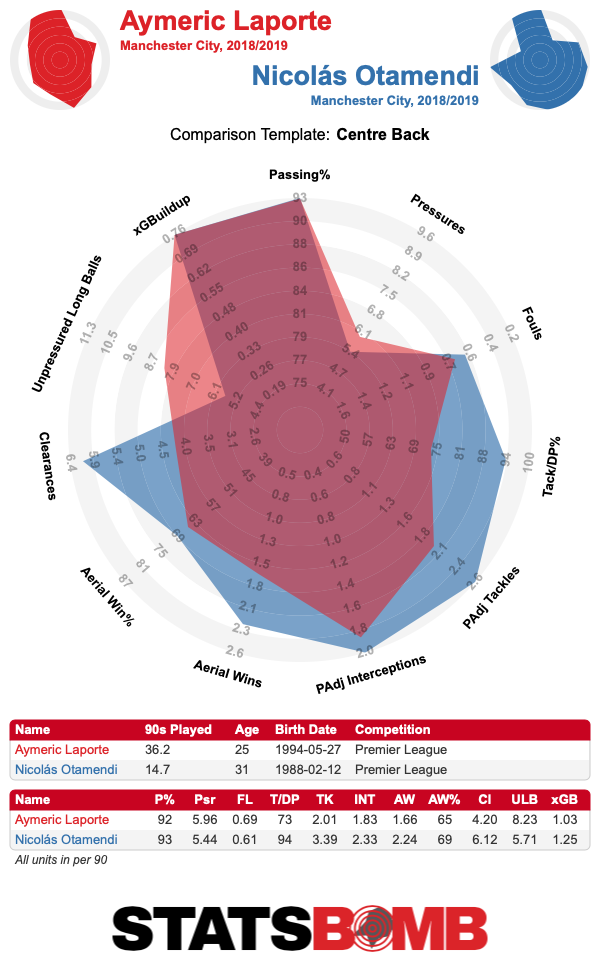

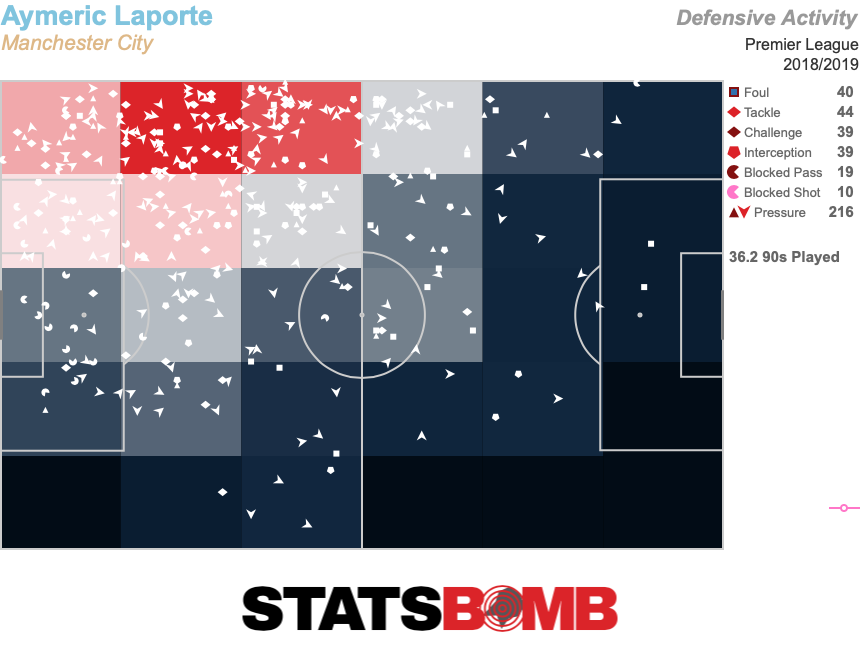

One thing Rodri perhaps lacks in the role is mobility. This might be part of Guardiola’s thinking in the new shape, putting Ilkay Gündoğan alongside the Spaniard in a double pivot, giving him some assistance and lessening the size of the area in which he needs to offer defensive cover. It’s not clear what exactly Gündoğan is offering in this regard. He isn’t a particularly aggressive ball winner. He’s not a tactical fouler, making less than one foul per 90. And he’s not especially adventurous in his passing. If adding him into a double pivot clearly isn’t making the side more stable, what is the point of him being there?  Obviously the other significant issue is Aymeric Laporte’s injury. It’s worth mentioning that City were not without defensive concern before then. Laporte played the full 90 minutes away at Bournemouth in a game where City conceded 1.63 xG from 10 shots. But it also seems fairly indisputable that the current pairing of Nicolás Otamendi and no-longer-midfielder Fernandinho are not fully capable of doing what is being asked of them. The issue is probably being magnified by what’s in front of them. It often felt like City’s pressing structure was so good, so complete, that you could play anyone at centre back and they’d have so little to do that it wouldn’t matter. The defensive injuries have come at the worst possible time for City in that the centre backs are being asked to do more decisive defending than ever. They’re not delivering on that front. All things considered, City are still a very good football team. Their xG difference per game of +1.86 is still comfortably the best in the Premier League, though it’s down to a hugely dominant attack overpowering the ninth best defence. The manager is, you know, not bad at his job. Liverpool have issues of their own. If the season reset to zero tomorrow, City would still be the clear favourites. An eight point gap is a real thing, though. For City to bridge it, they need to start playing their best football again as soon as possible. If these issues drag into the winter months, then things could become very difficult for the blue side of Manchester.

Obviously the other significant issue is Aymeric Laporte’s injury. It’s worth mentioning that City were not without defensive concern before then. Laporte played the full 90 minutes away at Bournemouth in a game where City conceded 1.63 xG from 10 shots. But it also seems fairly indisputable that the current pairing of Nicolás Otamendi and no-longer-midfielder Fernandinho are not fully capable of doing what is being asked of them. The issue is probably being magnified by what’s in front of them. It often felt like City’s pressing structure was so good, so complete, that you could play anyone at centre back and they’d have so little to do that it wouldn’t matter. The defensive injuries have come at the worst possible time for City in that the centre backs are being asked to do more decisive defending than ever. They’re not delivering on that front. All things considered, City are still a very good football team. Their xG difference per game of +1.86 is still comfortably the best in the Premier League, though it’s down to a hugely dominant attack overpowering the ninth best defence. The manager is, you know, not bad at his job. Liverpool have issues of their own. If the season reset to zero tomorrow, City would still be the clear favourites. An eight point gap is a real thing, though. For City to bridge it, they need to start playing their best football again as soon as possible. If these issues drag into the winter months, then things could become very difficult for the blue side of Manchester.

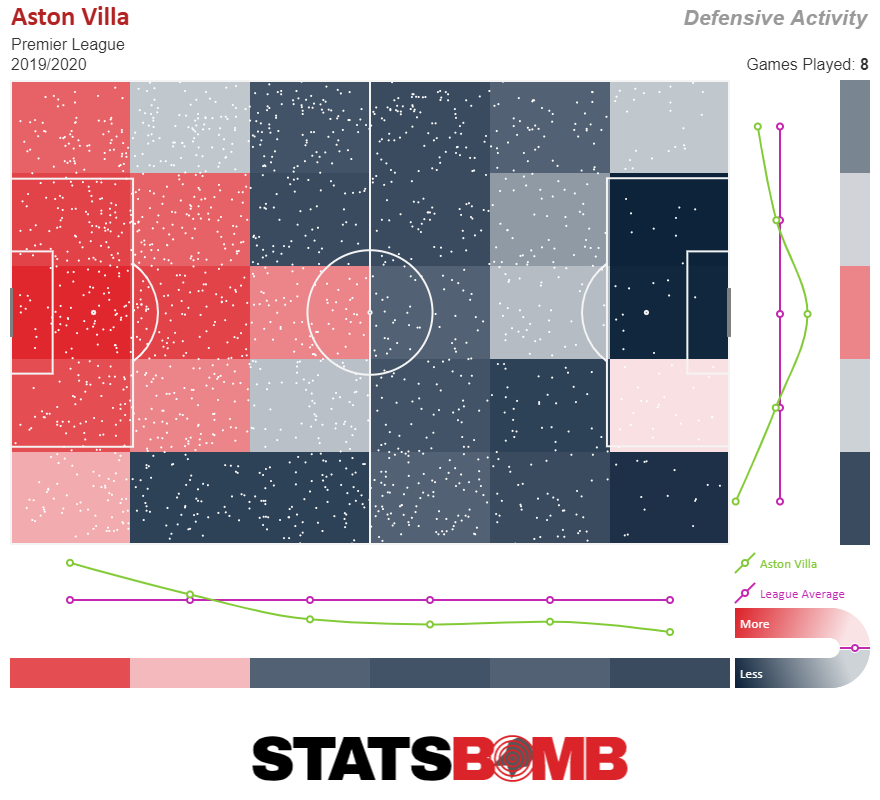

Aston Villa have made a surprisingly strong start to the season. It's not so much their position in the league table, they're 15th, but only one point above the relegation zone. Rather, the eye opening number is the fact that eight games into a season where the newly promoted team was expected to struggle, they've actually scored one more goal than they've conceded. Sadly for Villa, the xG numbers don't exactly back up their goal scoring record.

Specifically on the defensive side of the ball Villa have struggled with a case of the Arsenals. They give up a lot of shots:

And while the quality of those shots are generally low, they aren't on average low enough to make up for the extremely high volume.

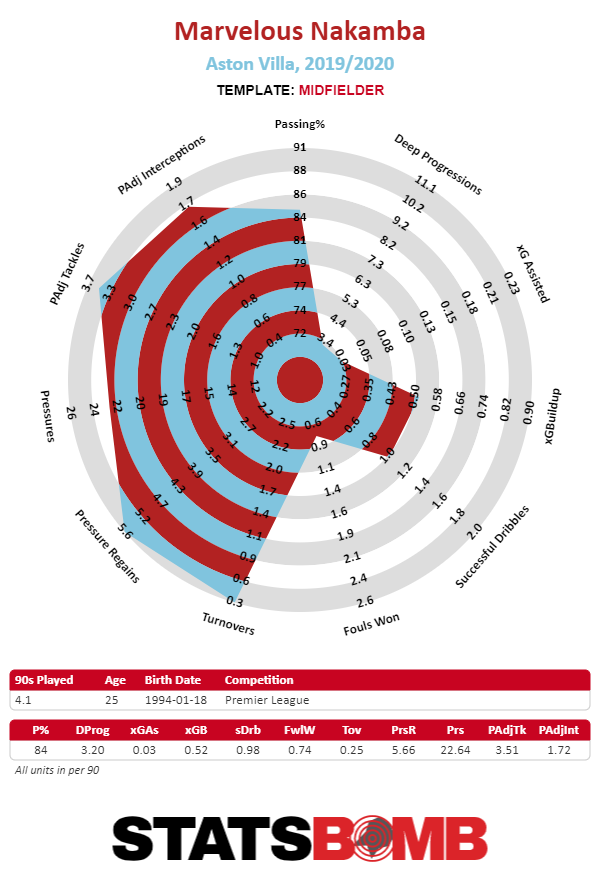

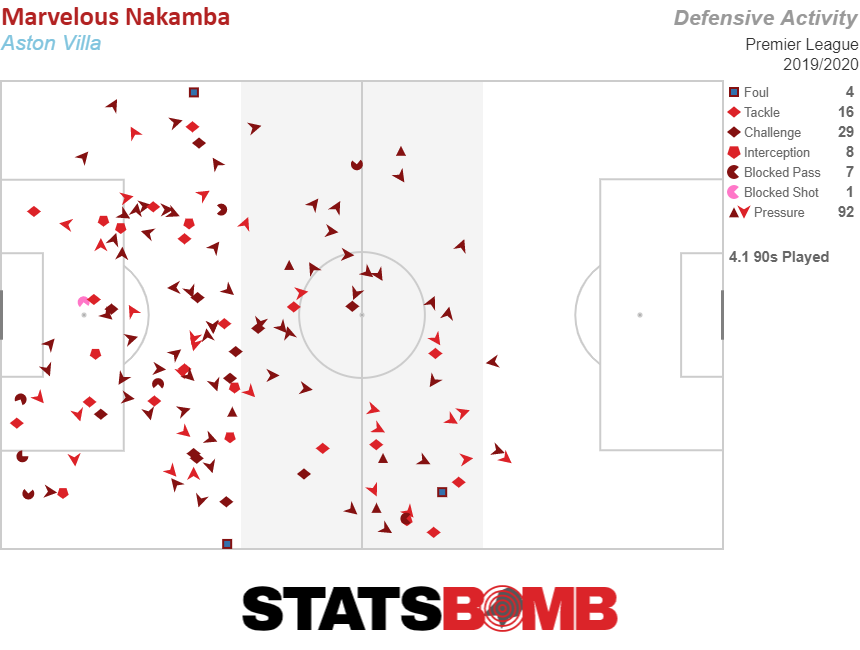

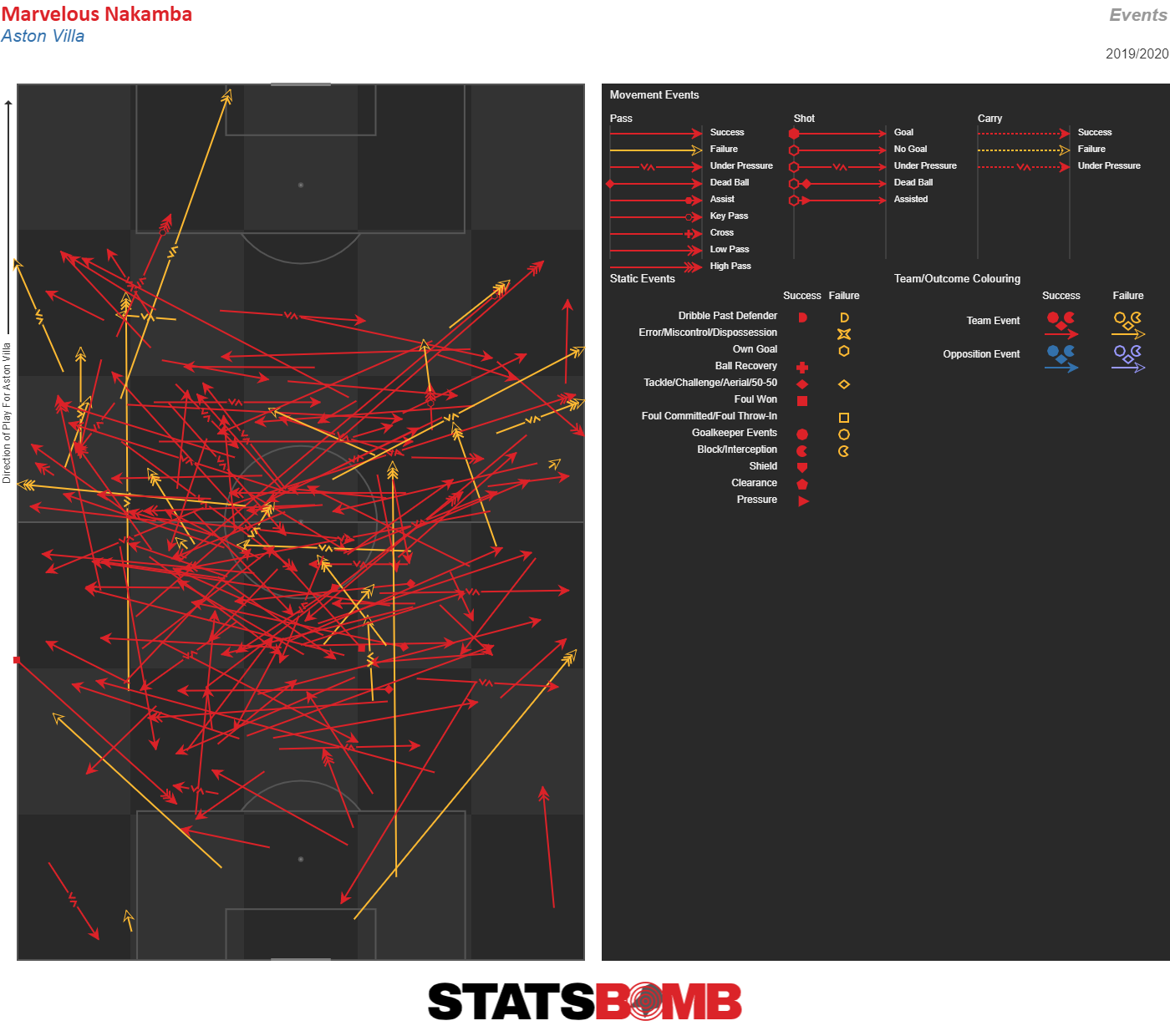

Nowhere is it as clear just how overwhelmed this Villa defense is than in the numbers of Marvelous Nakamba. The poor guy really is doing the most defensive work he can.

Nowhere will you find a clearer statistical example of a midfielder shielding his defenders than what he does. He just sits in the middle of the field and breaks up play after play after play in front of his own penalty area.

The problem for Villa is that it sure seems like their defensive midfielder is their first line of defense. The side simply offers zero opposition until the ball is sitting in Nakamba's lap.

Villa's surprisingly lively attack has received a lot of praise, especially after hanging five goals on Norwich last weekend. And it should. It's no small thing for a newly promoted team to be a Premier League average attack after eight matches. But it's coming at a cost. And the brunt of that cost is being born by Nakamba.

That's not to say, that Villa's defensive midfielder is perfect, or maybe even above average. His numbers in possession are truly terrible. He does very little to move the ball up the field, and despite his relatively unambitious passing, his pass completion percentage is only 84.5%.

Nakamba is as pure a defensive midfielder as you'll find in the Premier League. His job is to shield the back line and win the ball. On Aston Villa, that's a near impossible task. Villa is a classic case of a team that's putting its defensive personnel in a position to fail. Nakamba is performing admirably despite that. If Villa continue to play this way, and manage to remain in the Premier League it's going to look ugly defensively all year long. If it works, it'll just barely work, but if it weren't for Nakamba it would probably have no shot of working at all.

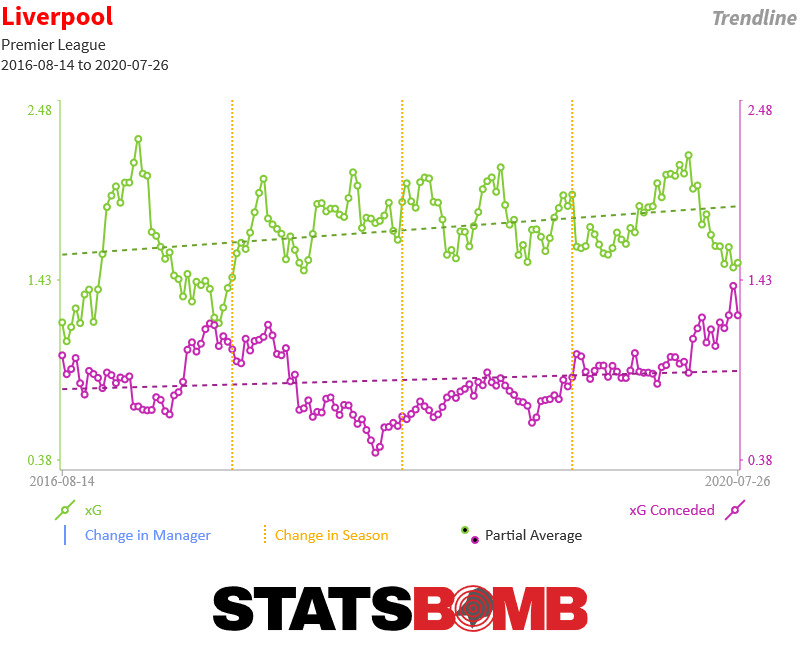

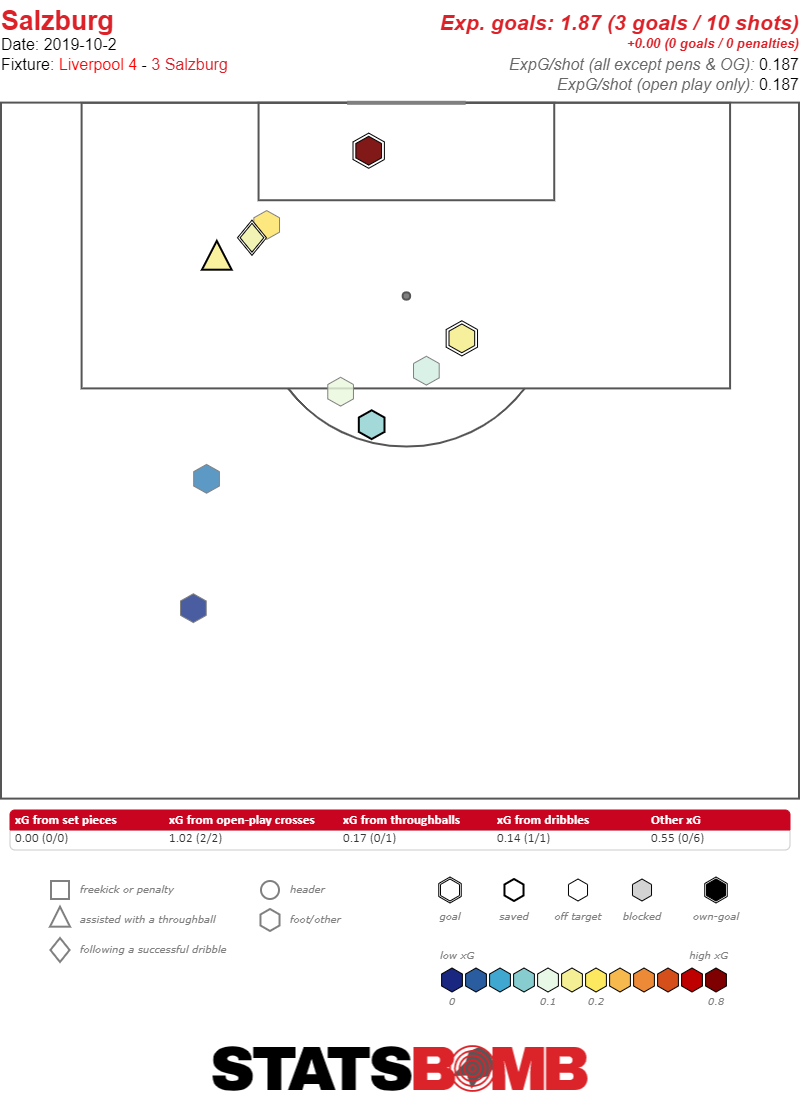

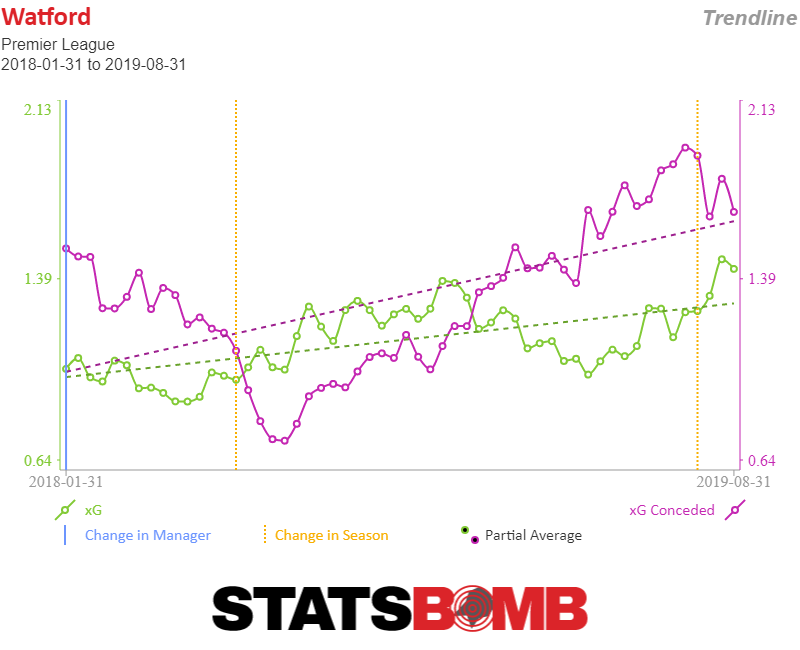

There’s an attacker in England who, after two seasons of utter dominance, has fallen down to Earth with good but not great production. His team’s record remains surprisingly strong, but underneath the hood, their expected goals record belies a team not actually at the station they expected to be, lucky to be above their rivals in the table. I’m talking, of course, about Mo Salah and Liverpool. It’s hard to complain about a team that has taken 21 of 21 points in the league and a guy who has three non-penalty goals and three assists in seven league matches, but the statistical record is flashing some warning signs. In 2017-2018, Salah came into the Premier League and set the world on fire. He took four shots per game, and racked up buckets of high quality chances, dribbling past would be defenders with aplomb, leaving them on the ground, and firing shots from the center of the box. His 0.6 expected goals per 90 minutes and 0.2 open play expected goals assisted per 90 led him to a Premier League Player of the Year. Last season, he came back to earth but was still excellent, with 0.4 xG per 90 and 0.22 open play xG assisted per 90. This season though? Through seven league matches Salah has just 0.37 xG per 90 and 0.05 xG assisted per 90. He’s still getting tons of touches in the box, more than last year in fact. But Salah is completing just 30% of his passes in the box or into the box to teammates, as compared to almost 50% last year. He’s also taken just a single shot with his feet within nine yards of goal this season. He had 29 such shots over the past two seasons combined. Perhaps that will change, but he does look somewhat less explosive than he did the last couple years, not turning the corner in the box with the same gusto. Two seasons of 4500 minutes plus playing in international tournaments may be taking its toll. Interestingly, the attack remains near last year's heights. Roberto Firmino and Sadio Mane have been excellent. While the team is not creating from open play like it did two seasons ago, they are finding more goals from set pieces. With the team treading water offensively, Liverpool’s xGD is a far cry from the heights of last season, and quite frankly, the second half of last season is a far cry from the first half:  As we saw against Salzburg, it is the defense that is struggling in particular, shipping significantly more high quality chances than it did last season.

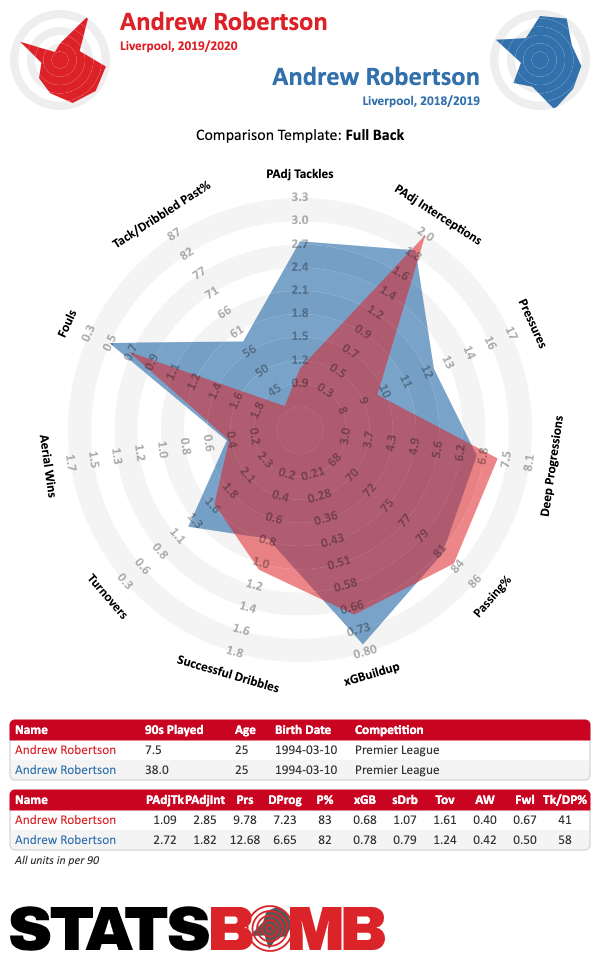

As we saw against Salzburg, it is the defense that is struggling in particular, shipping significantly more high quality chances than it did last season.  Perhaps the defense is struggling because the defenders are being asked to do too much in attack. Klopp played Andrew Robertson over 4500 minutes last season, rarely rotating his hyper-athletic left back who also was one of the team’s major creative engines. The wear on Robertson appears to be showing, with Robbo getting beaten much more consistently this season.

Perhaps the defense is struggling because the defenders are being asked to do too much in attack. Klopp played Andrew Robertson over 4500 minutes last season, rarely rotating his hyper-athletic left back who also was one of the team’s major creative engines. The wear on Robertson appears to be showing, with Robbo getting beaten much more consistently this season.  Trent Alexander-Arnold who also played a huge number of minutes at such a demanding position is also struggling to meet last year’s heights and is also one of Liverpool’s key creators. Last season and this season Liverpool got much of its creative output from its two fullbacks, but have perhaps ramped up their intensity even higher as a result of the midfield’s lack of ball progression. Alexander-Arnold and Robertson are combining for over 5.5 touches in the box so far this season, up significantly from about 4 combined last season. Robertson has even more deep progressions this year than last, one of his few increases in output. Robertson’s charging run into the box for a goal against Salzburg was a wonderful piece of skill, but also perhaps indicative of a team that has turned to its fullbacks to do too much, especially given that in the same move he was the player to advance the ball into the opposition half from his own defensive zone. Even so, last year Liverpool asked a lot of its fullbacks and were rock solid defensively. Teams do seem to be exploiting the space left by Alexander-Arnold more ruthlessly. The number of successful passes into areas he nominally would be controlling have increased significantly on a per 90 basis this season. But perhaps the other major change has been the loss of Alisson to start the season. Alisson is significantly more aggressive off his line than Adrian.

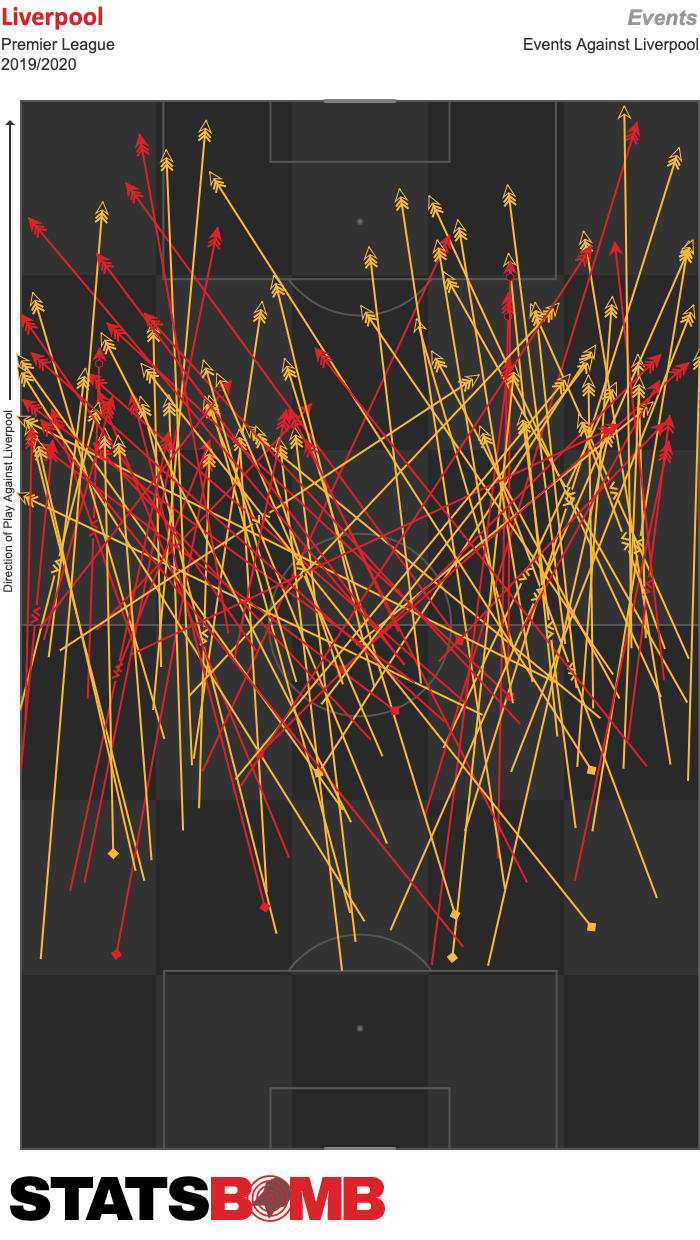

Trent Alexander-Arnold who also played a huge number of minutes at such a demanding position is also struggling to meet last year’s heights and is also one of Liverpool’s key creators. Last season and this season Liverpool got much of its creative output from its two fullbacks, but have perhaps ramped up their intensity even higher as a result of the midfield’s lack of ball progression. Alexander-Arnold and Robertson are combining for over 5.5 touches in the box so far this season, up significantly from about 4 combined last season. Robertson has even more deep progressions this year than last, one of his few increases in output. Robertson’s charging run into the box for a goal against Salzburg was a wonderful piece of skill, but also perhaps indicative of a team that has turned to its fullbacks to do too much, especially given that in the same move he was the player to advance the ball into the opposition half from his own defensive zone. Even so, last year Liverpool asked a lot of its fullbacks and were rock solid defensively. Teams do seem to be exploiting the space left by Alexander-Arnold more ruthlessly. The number of successful passes into areas he nominally would be controlling have increased significantly on a per 90 basis this season. But perhaps the other major change has been the loss of Alisson to start the season. Alisson is significantly more aggressive off his line than Adrian.  While Virgil Van Dijk can do almost everything, perhaps he cannot cover for two fullbacks and a less aggressive keeper. Looking at the radars of the two keepers, you can see that Alisson’s “GK Aggressive Distance” - where he makes tackles, interceptions, etc. - is much farther off the line than Adrian, who has otherwise filled in quite admirably. Liverpool’s high line, and very high fullbacks, have survived because Van Dijk is so good at filling in space, but also because their goalkeeper was perhaps also good at protecting the team from dangerous long balls into space. Using Statsbomb’s IQ tactics we can look at how well teams are completing passes against Liverpool that start from above the box in their own half and go into the final third. Last season teams completed 29% of such passes and completed 4.6 such passes per match. So far those numbers are 39% and 6.3.

While Virgil Van Dijk can do almost everything, perhaps he cannot cover for two fullbacks and a less aggressive keeper. Looking at the radars of the two keepers, you can see that Alisson’s “GK Aggressive Distance” - where he makes tackles, interceptions, etc. - is much farther off the line than Adrian, who has otherwise filled in quite admirably. Liverpool’s high line, and very high fullbacks, have survived because Van Dijk is so good at filling in space, but also because their goalkeeper was perhaps also good at protecting the team from dangerous long balls into space. Using Statsbomb’s IQ tactics we can look at how well teams are completing passes against Liverpool that start from above the box in their own half and go into the final third. Last season teams completed 29% of such passes and completed 4.6 such passes per match. So far those numbers are 39% and 6.3.  Simpler explanations for Liverpool’s statistical (though otherwise non-existent) struggles may also suffice. Seven matches is a small sample size. Virgil Van Dijk could have experienced a career year at 27 and still be great, just not superhuman this season. Of course, Liverpool may well start producing at last year’s levels again soon. Still, it’s important not to get fooled by the record and to see that maybe there are some cracks in what otherwise seems like an unstoppable juggernaut.

Simpler explanations for Liverpool’s statistical (though otherwise non-existent) struggles may also suffice. Seven matches is a small sample size. Virgil Van Dijk could have experienced a career year at 27 and still be great, just not superhuman this season. Of course, Liverpool may well start producing at last year’s levels again soon. Still, it’s important not to get fooled by the record and to see that maybe there are some cracks in what otherwise seems like an unstoppable juggernaut.

There are a lot of players in the Premier League. Generally speaking, to reach the top flight of English football, most of them are quite good. We're quite used to generalised qualities at this point. Fullbacks who can overlap, inverted wingers who can cut inside and shoot, defensive midfielders who can win the ball back aggressively. But there are some players who just do things differently to everyone else. This might not necessarily be a positive or negative thing, but here are six individuals who have statistically stood out as unusual so far this season.

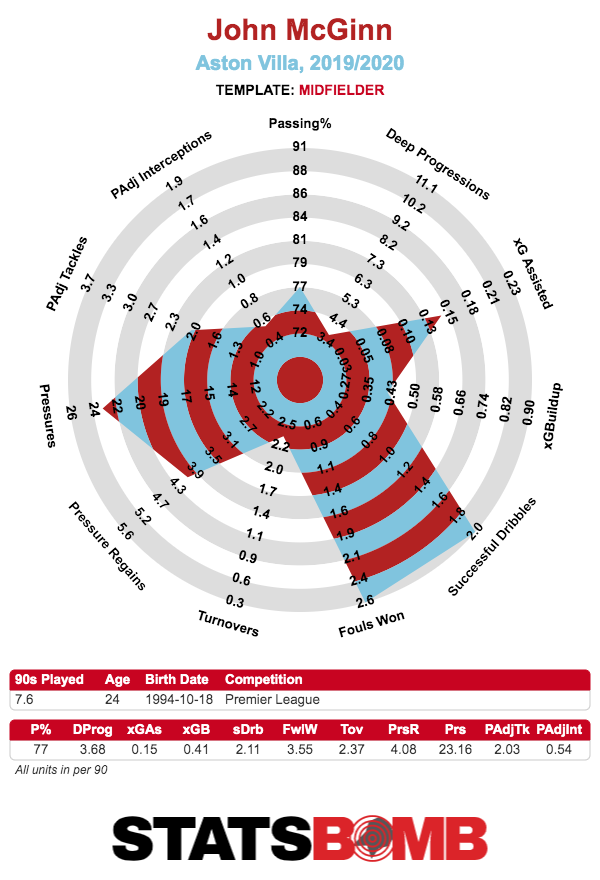

John McGinn

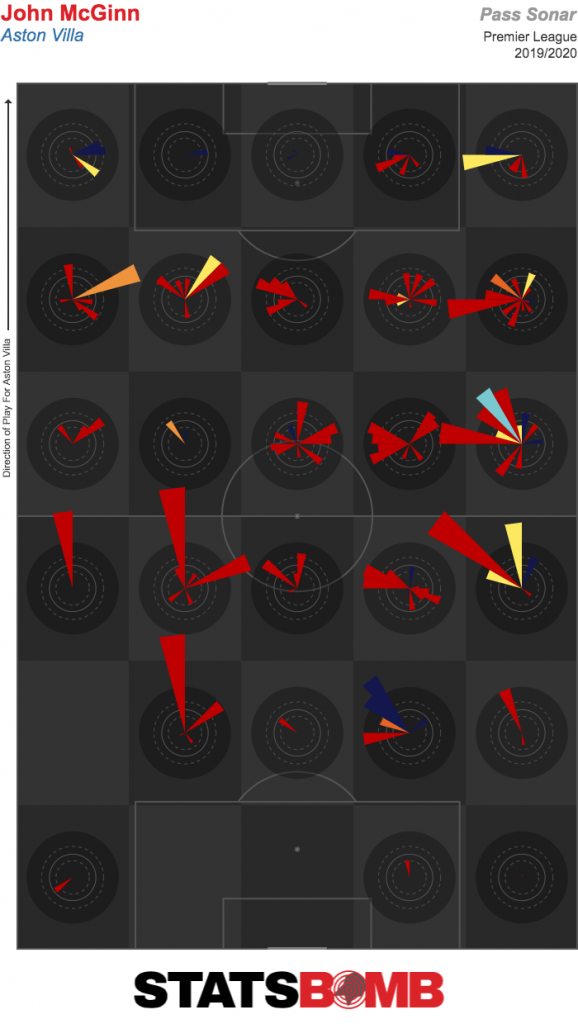

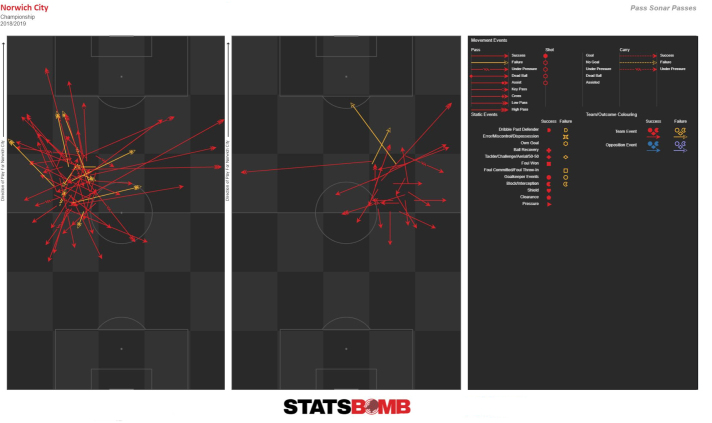

Of all the players to feature in central midfield this season, only three, Ross Barkley, Tanguy Ndombele and Kevin De Bruyne (interpreting “central midfield” loosely here), have made more successful dribbles per 90 than John McGinn. Only McGinn’s Villa teammate Jack Grealish has won more fouls per 90 than the Scotland international. So we know what it is that he does. But on the other side, no central midfielder is making fewer passes per 90 than McGinn. This is someone who seems to choose to dribble and thus draw fouls over passing the ball at every possible opportunity.  When McGinn does pass the ball, he isn’t shy about pinging it, with the seventh longest average pass length of any central midfielder. It’s clear in his sonar just how direct he’s willing to go.

When McGinn does pass the ball, he isn’t shy about pinging it, with the seventh longest average pass length of any central midfielder. It’s clear in his sonar just how direct he’s willing to go.  Or alternatively, he’ll carry it, with the third longest carry length in the position. He’ll do anything except the obvious option of keeping it simple and making a pass. This might be because he’s playing with Grealish, natural playmaker extraordinaire. It could simply be that it’s just his natural game. His application and desire to run is the kind of thing that catches the eye of fans, especially in the UK, and it’s hard to argue he’s not a useful player for Villa. He does have this very obvious, somewhat bizarre limit, and Dean Smith needs to construct his side accordingly for it. Unfortunately for McGinn, one would imagine these limitations make the bottom half of the Premier League his ceiling, with a better side that dominates possession unlikely to want to have to tweak the midfield balance to fit him in. For now, though, Villa fans should enjoy the things he does and worry not about his lack of passing.

Or alternatively, he’ll carry it, with the third longest carry length in the position. He’ll do anything except the obvious option of keeping it simple and making a pass. This might be because he’s playing with Grealish, natural playmaker extraordinaire. It could simply be that it’s just his natural game. His application and desire to run is the kind of thing that catches the eye of fans, especially in the UK, and it’s hard to argue he’s not a useful player for Villa. He does have this very obvious, somewhat bizarre limit, and Dean Smith needs to construct his side accordingly for it. Unfortunately for McGinn, one would imagine these limitations make the bottom half of the Premier League his ceiling, with a better side that dominates possession unlikely to want to have to tweak the midfield balance to fit him in. For now, though, Villa fans should enjoy the things he does and worry not about his lack of passing.

Ryan Fredericks

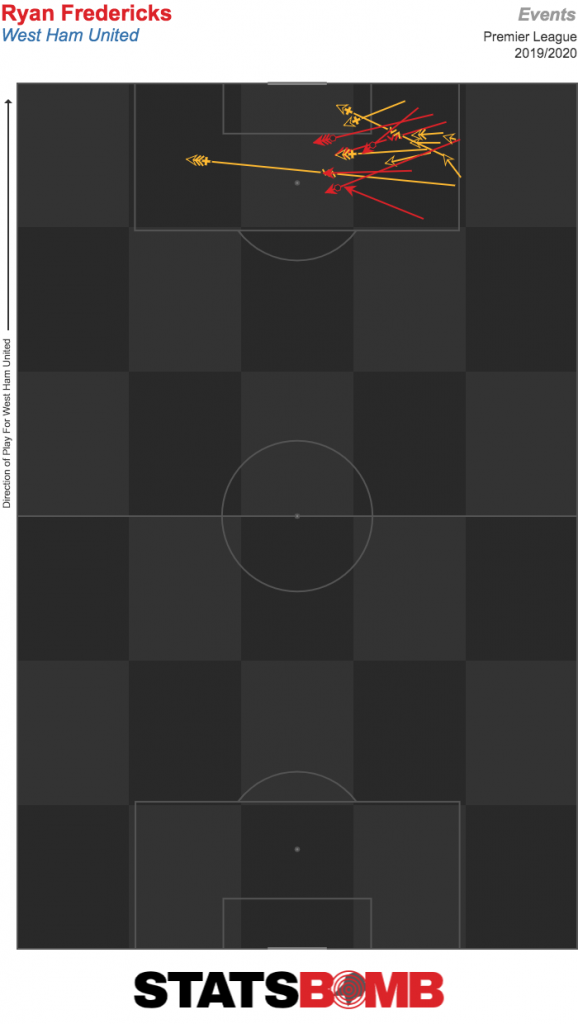

Mohamed Salah has attempted 18 passes inside the box so far this season. That’s the most of any player in the division. Wilfried Zaha and Jamie Vardy are next up with 17 and 13 each. If I told you the next player was a fullback, you might think of Liverpool’s pair of Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold, or possibly someone like Oleksandr Zinchenko. You probably wouldn’t expect it to be someone who featured so irregularly for West Ham last season.  Ryan Fredericks looks a fairly average right back by most other measures. He’s not a hugely active defender, and he’s not progressing the ball up the pitch that well until it gets into the box. The player this is somewhat reminiscent of is Sead Kolasinac. Last season, Kolasinac consistently put up incredible creative numbers by getting forward and delivering cut backs to Arsenal’s talented attack. Fredericks isn’t creating at such a rate yet, but the potential seems to be there. Of course, the other side of Kolasinac was his inability to cover such ground that he could provide a threat in the final third without leaving his side horribly exposed. That Arsenal felt the need to buy Kieran Tierney shows just how little Kolasinac’s unusual skills were seen as helpful in the end. Fredericks may have the advantage here of being a much better athlete. He has the speed to cover much more ground than Kolasinac, to get into the box and still potentially recover defensively if the Hammers get caught out. We’re dealing with a small sample size here, and this is something that could easily drift away as the season goes on, especially if Manuel Pellegrini wants to tighten things up at the back. But Fredericks might have the toolkit to be a very interesting, very adventurous right back who can be an important cog in West Ham’s attack.

Ryan Fredericks looks a fairly average right back by most other measures. He’s not a hugely active defender, and he’s not progressing the ball up the pitch that well until it gets into the box. The player this is somewhat reminiscent of is Sead Kolasinac. Last season, Kolasinac consistently put up incredible creative numbers by getting forward and delivering cut backs to Arsenal’s talented attack. Fredericks isn’t creating at such a rate yet, but the potential seems to be there. Of course, the other side of Kolasinac was his inability to cover such ground that he could provide a threat in the final third without leaving his side horribly exposed. That Arsenal felt the need to buy Kieran Tierney shows just how little Kolasinac’s unusual skills were seen as helpful in the end. Fredericks may have the advantage here of being a much better athlete. He has the speed to cover much more ground than Kolasinac, to get into the box and still potentially recover defensively if the Hammers get caught out. We’re dealing with a small sample size here, and this is something that could easily drift away as the season goes on, especially if Manuel Pellegrini wants to tighten things up at the back. But Fredericks might have the toolkit to be a very interesting, very adventurous right back who can be an important cog in West Ham’s attack.

Dan Burn

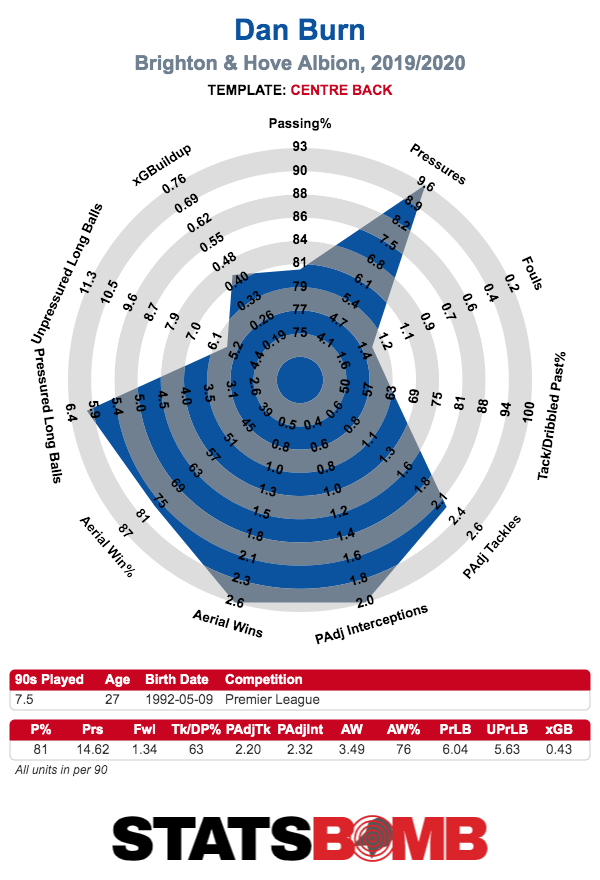

When Graham Potter arrived at Brighton, the expectation was that he would change the style of football. The attacking emphasis would be greater, he’d move to a system with three at the back, and defenders previously accustomed to hoofing it would be asked to play more football. The assumption was that new signing Adam Webster, a centre back extremely comfortable taking risks, would be the poster boy for this shift. It was not expected that Potter would make Dan Burn the key player in his new defensive system.  If you’re moving to a back three, having a left footed defender like Burn is always a bonus, especially when he even played occasional left back minutes at Wigan. What we’re seeing so far from Burn is someone extremely comfortable moving forward. While we’re dealing with small sample sizes here, no other centre back in the league gets close to his 0.8 open play passes into the box per 90. Similarly, he leads the division’s centre backs in open play passes in the final third per 90. And it doesn’t stop with his passing range, also posting the most frequent attempted dribbles, though with fully half of them not coming off, he should probably slow down on that front. The wide centre back roles in a back three can often be slightly strange hybrid positions, neither centre back nor full back. Perhaps unexpectedly, Burn is interpreting the role in a particularly expansive manner.

If you’re moving to a back three, having a left footed defender like Burn is always a bonus, especially when he even played occasional left back minutes at Wigan. What we’re seeing so far from Burn is someone extremely comfortable moving forward. While we’re dealing with small sample sizes here, no other centre back in the league gets close to his 0.8 open play passes into the box per 90. Similarly, he leads the division’s centre backs in open play passes in the final third per 90. And it doesn’t stop with his passing range, also posting the most frequent attempted dribbles, though with fully half of them not coming off, he should probably slow down on that front. The wide centre back roles in a back three can often be slightly strange hybrid positions, neither centre back nor full back. Perhaps unexpectedly, Burn is interpreting the role in a particularly expansive manner.

Moritz Leitner

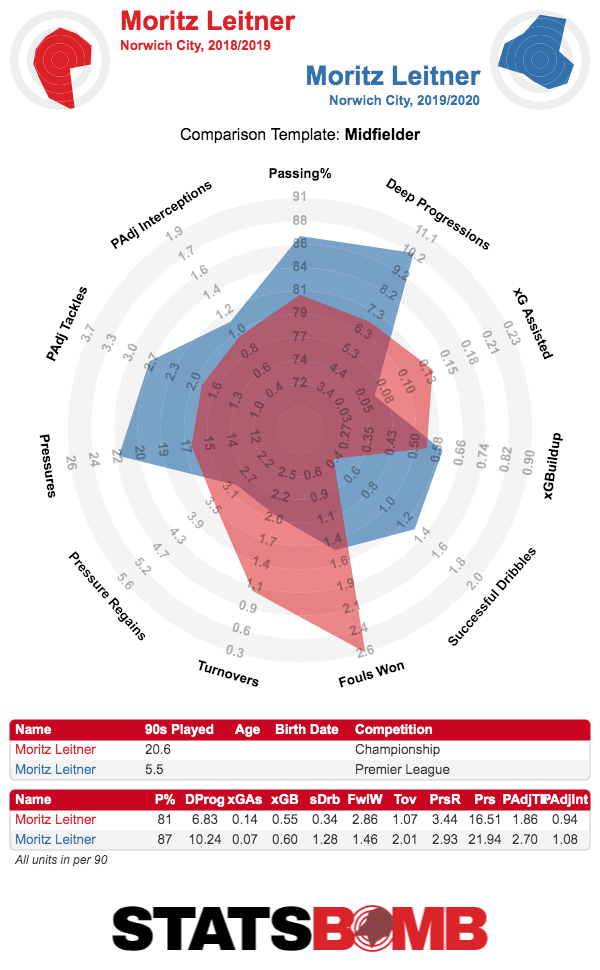

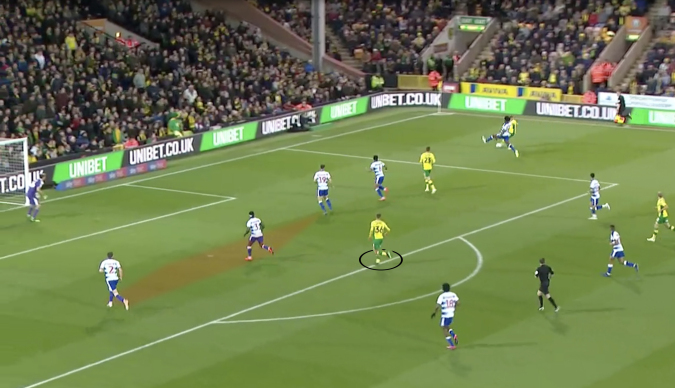

So you’re a promoted side that decides to stick with your progressive brand of football in the Premier League. You’ve also decided to keep the budget down and avoid splashing out on expensive signings. What you need is one of your central midfielders to really step up and progress the ball at an even better rate than last season, while at the same time working harder defensively than before.  After failing to make the grade at Borussia Dortmund before bouncing around Stuttgart, Lazio and Augsburg, Moritz Leitner has become the hard working creative central midfielder that makes Norwich tick. In the entire league, only Harry Winks is putting up more deep progressions per 90 than the German. Aymeric Laporte and Robertson are the only players with more carries per 90 than Leitner. And even after the ball is worked into the final third, he’s still among the top 20 players for passes within that zone. For a team with only 50% possession. Norwich are more an interesting team this season than they are good, with the side needing to hope their fourth worst expected goal difference in the league will be enough to see them right. When they work the ball into dangerous areas, though, they’re a delight to watch, and Leitner is absolutely a key player in making those situations happen.

After failing to make the grade at Borussia Dortmund before bouncing around Stuttgart, Lazio and Augsburg, Moritz Leitner has become the hard working creative central midfielder that makes Norwich tick. In the entire league, only Harry Winks is putting up more deep progressions per 90 than the German. Aymeric Laporte and Robertson are the only players with more carries per 90 than Leitner. And even after the ball is worked into the final third, he’s still among the top 20 players for passes within that zone. For a team with only 50% possession. Norwich are more an interesting team this season than they are good, with the side needing to hope their fourth worst expected goal difference in the league will be enough to see them right. When they work the ball into dangerous areas, though, they’re a delight to watch, and Leitner is absolutely a key player in making those situations happen.

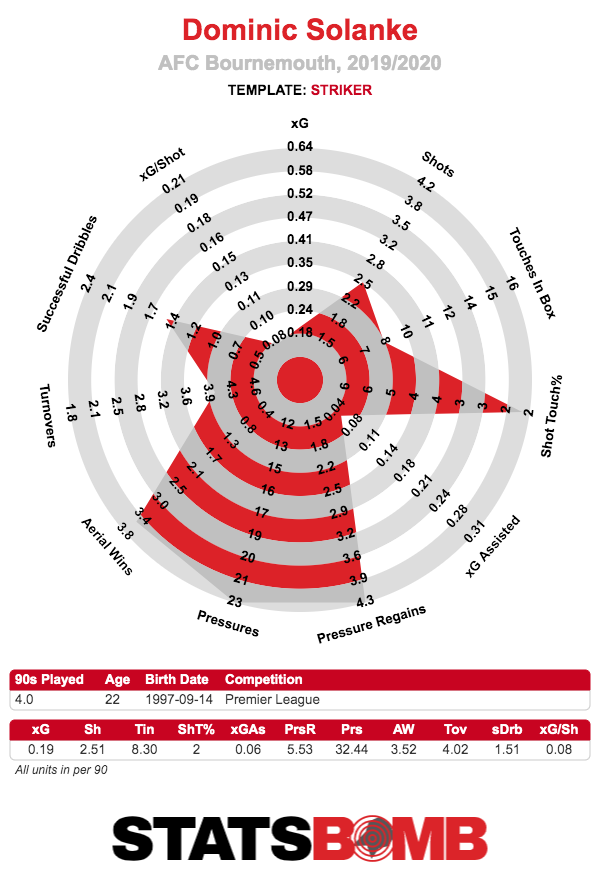

Dominic Solanke

Let’s not beat around the bush here: Dominic Solanke has been bad at scoring goals. And this isn’t even a situation similar to his time at Liverpool where he just wasn’t finishing good chances. His 0.19 xG per 90 is nothing other than poor, especially compared to what his teammate Callum Wilson is doing. But that’s not the end of the story for Solanke. Only two players in the Premier League are managing more pressures per 90 than the Bournemouth man. What’s more, no striker (if we discount Wilfried Zaha and Gerard Deulofeu on the grounds that they are not really strikers) is making more deep progressions per 90 than Solanke. He’s working hard for the team by closing down opponents, then receiving the ball in deep areas to progress it forward. While playing as a striker.  Does it matter that he’s not scoring more? In terms of public perception it seems to. Solanke will be “shit until he scores loads” in the court of public opinion. But in terms of Bournemouth’s system, it’s not obvious that this is a problem. Playing in a front two with Wilson, the more important role is to ensure that the strikers do not become isolated or the midfield gets exposed. Solanke is ideal for this, and should be able to do the role at a higher level than Joshua King.

Does it matter that he’s not scoring more? In terms of public perception it seems to. Solanke will be “shit until he scores loads” in the court of public opinion. But in terms of Bournemouth’s system, it’s not obvious that this is a problem. Playing in a front two with Wilson, the more important role is to ensure that the strikers do not become isolated or the midfield gets exposed. Solanke is ideal for this, and should be able to do the role at a higher level than Joshua King.

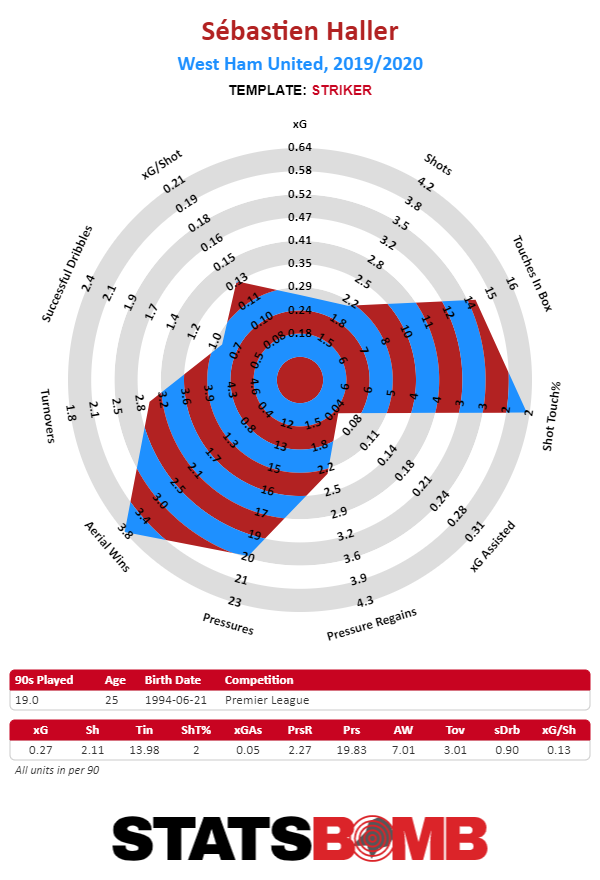

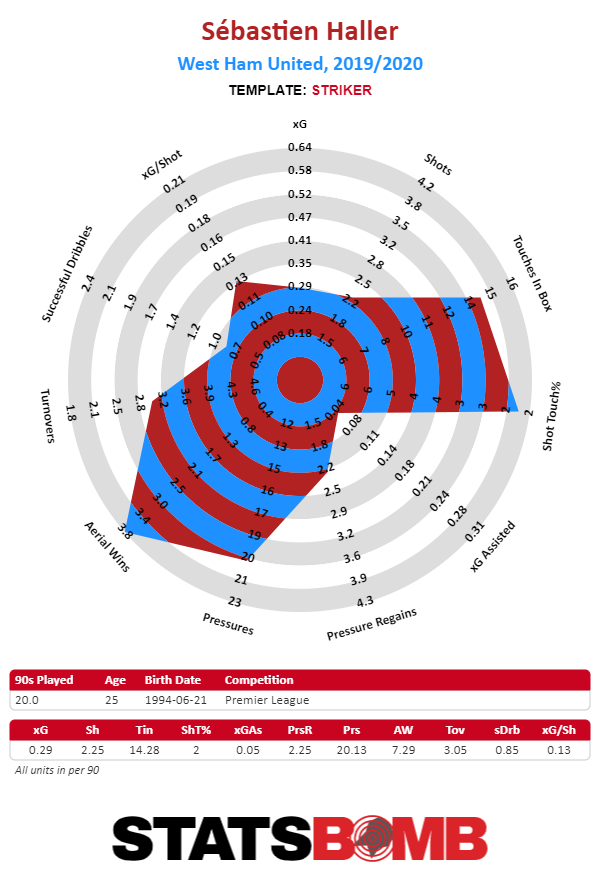

Sebastien Haller

Ok, but what if someone was doing a lot of the things Solanke offers, while also scoring goals? Meet Sebastien Haller.  No striker (again, discounting Deulofeu because he isn’t one) is making more open play passes per 90 than Haller. Only Solanke is putting up more deep progressions. He’s exerting a very respectable 20.11 pressures per 90. His shot volume is on the low side, but when he gets them, boy does he get some good ones.

No striker (again, discounting Deulofeu because he isn’t one) is making more open play passes per 90 than Haller. Only Solanke is putting up more deep progressions. He’s exerting a very respectable 20.11 pressures per 90. His shot volume is on the low side, but when he gets them, boy does he get some good ones.  Haller combines the all round play of a striker who typically wouldn’t score a lot of goals with the shot profile of a pure poacher. It’s a fascinating package of skills and West Ham can consider themselves to have a real gem here.

Haller combines the all round play of a striker who typically wouldn’t score a lot of goals with the shot profile of a pure poacher. It’s a fascinating package of skills and West Ham can consider themselves to have a real gem here.

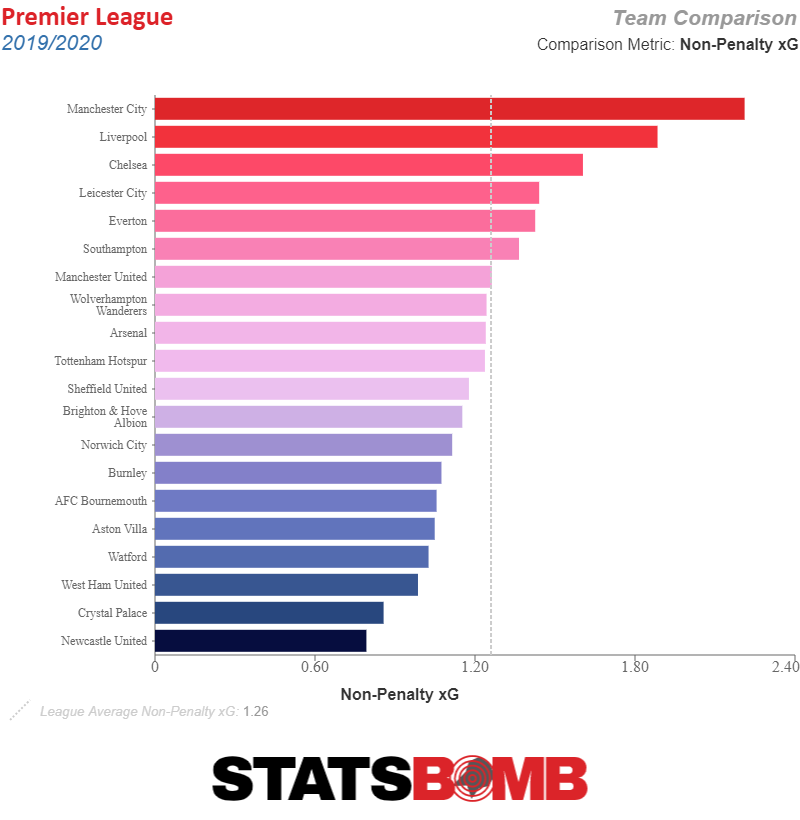

If any football club knows about breaking the hegemony of the top sides, it’s Leicester. Cast your minds back to the ancient days of summer 2019. Things were simpler back then. The days were longer. The weather was warmer. There was a consensus about an emerging “chasing pack” of teams capable of challenging the Premier League’s top six. Wolves, Everton, Leicester and West Ham were all seen as having a real chance of breaking in. Some even put Watford among that group. Cut to late September and we’ve seen some differences in fortunes. Wolves and Watford sit at 19th and 20th in the table. They’re both capable of turning things, but a midtable finish would look like a positive right now. Everton also look like they can shake off some early season rust, but it does seem as though there are concerns in that side. West Ham find themselves with an impressive 11 points, but there are concerns in the numbers. Their 10.70 expected goals conceded is the second worst in the division, while 7.51 xG on the attacking side is only league average. The Hammers should be pleased with their start, but it feels like their midfield solidity questions have not been answered satisfactorily. So that leaves us with Leicester. The Foxes find themselves third in the table and the thing to note is that they haven’t had a gentle schedule. The club have already faced three of the “official” top six, with a very reasonable four points from those games. A tough start to the season obviously necessitates a more defensive minded approach, and Leicester have defended very well so far. Things have gone their way a touch, but their 5.35 xG conceded is currently the fourth best in the league.  Of course, there have been payoffs at the other end, with Leicester’s 6.46 xG on the attacking side looking below average, though this has a chance to shift when the fixture list eases up.

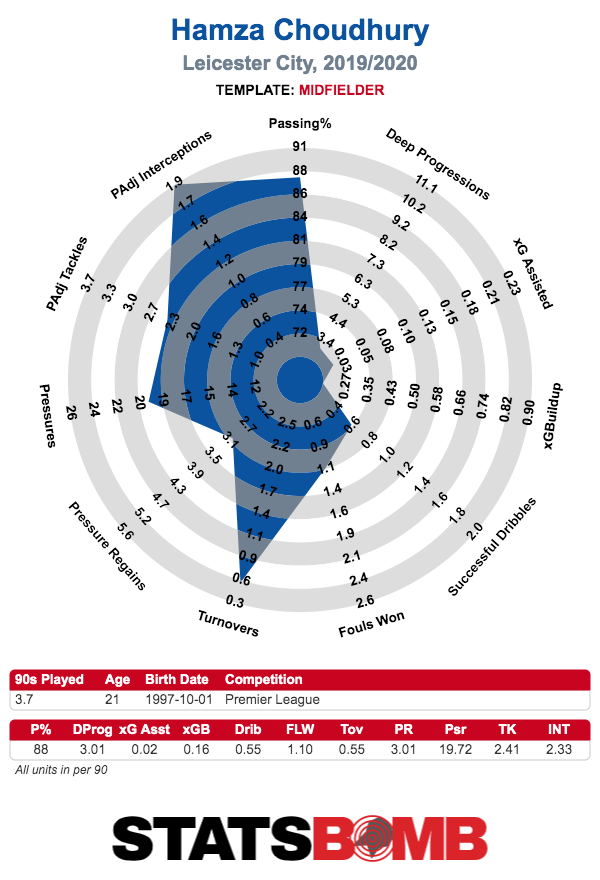

Of course, there have been payoffs at the other end, with Leicester’s 6.46 xG on the attacking side looking below average, though this has a chance to shift when the fixture list eases up.  This feels like a conscious choice on the part of manager Brendan Rodgers. While the image of the Northern Irishman for many is of the high scoring, high conceding Liverpool side of 2013/14, he is ultimately a chameleon, borrowing tactics from elsewhere and implementing them quickly before other sides catch on and find solutions. While much of Leicester’s most exciting football has come with James Maddison and Youri Tielemans playing in front of Wilfried Ndidi in a midfield three, Rodgers has opted to shift Maddison wide this year and add the extra solidity of Hamza Choudhury for four of this year’s six games. Choudhury is a solid defender, but his threat on the ball remains extremely limited and he thus mostly opts to simply recycle possession.

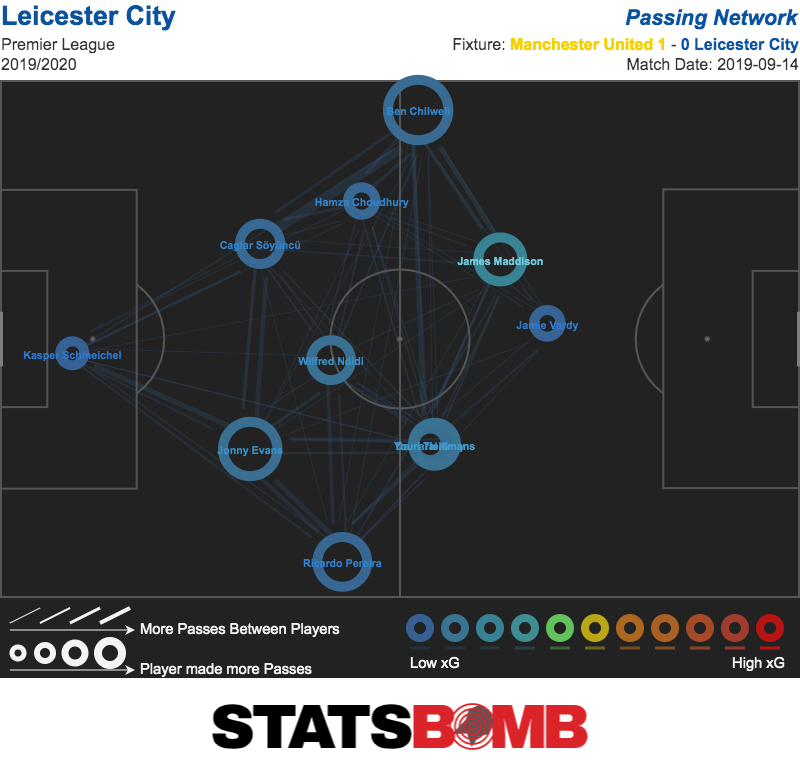

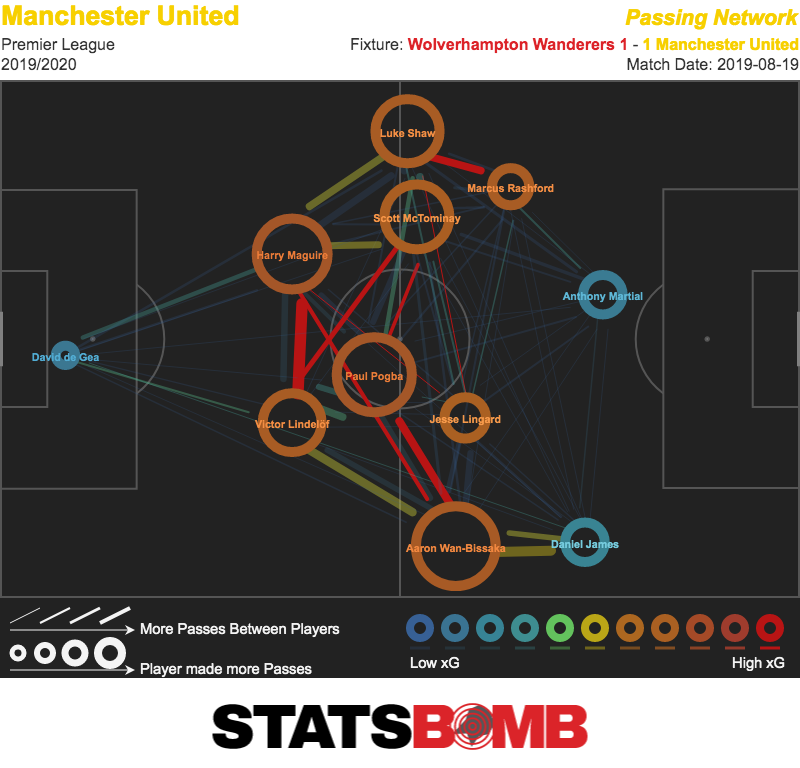

This feels like a conscious choice on the part of manager Brendan Rodgers. While the image of the Northern Irishman for many is of the high scoring, high conceding Liverpool side of 2013/14, he is ultimately a chameleon, borrowing tactics from elsewhere and implementing them quickly before other sides catch on and find solutions. While much of Leicester’s most exciting football has come with James Maddison and Youri Tielemans playing in front of Wilfried Ndidi in a midfield three, Rodgers has opted to shift Maddison wide this year and add the extra solidity of Hamza Choudhury for four of this year’s six games. Choudhury is a solid defender, but his threat on the ball remains extremely limited and he thus mostly opts to simply recycle possession.  Rodgers’ solution to this has been to instruct Choudhury to move to a left sided role while in possession, with Maddison moving in to become a number ten. This obviously allows Maddison to become much more involved in the attacking phase while minimising the number of times Choudhury has to touch the ball. The passmap against Manchester United shows it well, with Choudhury taking touches in much wider areas despite nominally playing a more central role than Maddison.

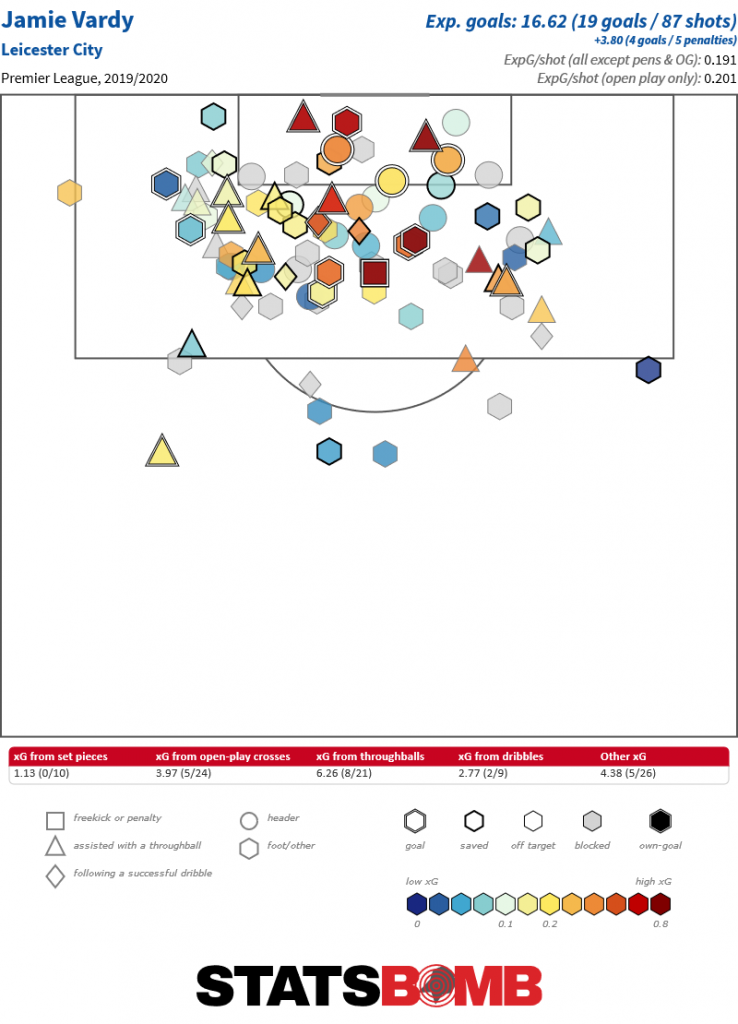

Rodgers’ solution to this has been to instruct Choudhury to move to a left sided role while in possession, with Maddison moving in to become a number ten. This obviously allows Maddison to become much more involved in the attacking phase while minimising the number of times Choudhury has to touch the ball. The passmap against Manchester United shows it well, with Choudhury taking touches in much wider areas despite nominally playing a more central role than Maddison.  It’s not obvious whether this fixes the problem or simply moves it around. Yes, it ensures Maddison is the most involved creator, but it means Leicester essentially sacrifice any attacking threat from a left winger to do so. When Maddison or Tielemans receive the ball as the team is attacking, they now only have two obvious outlets making runs into the box: Jamie Vardy or whoever is playing on the right wing. In terms of Vardy, the past year or so has shown him continue to defy father time and produce a good volume of shots in dangerous locations. That hasn’t happened as much this year (his xG per 90 is an underwhelming 0.25), but it can perhaps be excused due to Leicester’s generally defensive approach. When looking at his shot map, the thing that stands out is just how many of his chances are still from through balls. It would be hard to do that if he had physically declined in a big way.

It’s not obvious whether this fixes the problem or simply moves it around. Yes, it ensures Maddison is the most involved creator, but it means Leicester essentially sacrifice any attacking threat from a left winger to do so. When Maddison or Tielemans receive the ball as the team is attacking, they now only have two obvious outlets making runs into the box: Jamie Vardy or whoever is playing on the right wing. In terms of Vardy, the past year or so has shown him continue to defy father time and produce a good volume of shots in dangerous locations. That hasn’t happened as much this year (his xG per 90 is an underwhelming 0.25), but it can perhaps be excused due to Leicester’s generally defensive approach. When looking at his shot map, the thing that stands out is just how many of his chances are still from through balls. It would be hard to do that if he had physically declined in a big way.  And Leicester need him to make those runs to receive through balls, because they’re not getting a lot from the right. Ayoze Perez has been played there most frequently, and it’s fair to say he’s not interpreting the role in the most exciting way. He’s taken all of five shots so far for just 0.3 expected goals, but you can’t say he’s not working hard. It takes the midfield radar to show just how much effort he’s putting in on the defensive side:

And Leicester need him to make those runs to receive through balls, because they’re not getting a lot from the right. Ayoze Perez has been played there most frequently, and it’s fair to say he’s not interpreting the role in the most exciting way. He’s taken all of five shots so far for just 0.3 expected goals, but you can’t say he’s not working hard. It takes the midfield radar to show just how much effort he’s putting in on the defensive side:  For whatever reason, Rodgers made the decision to concentrate on defensive stoutness in the opening part of the season. But some hope has come recently for a more progressive football. Leicester returned to starting Maddison and Tielemans as free eights in the win against Tottenham, with Harvey Barnes and Perez wide. The passmap below shows how willing Maddison and Tielemans were to push up, making it a genuine 4-1-4-1 in possession.

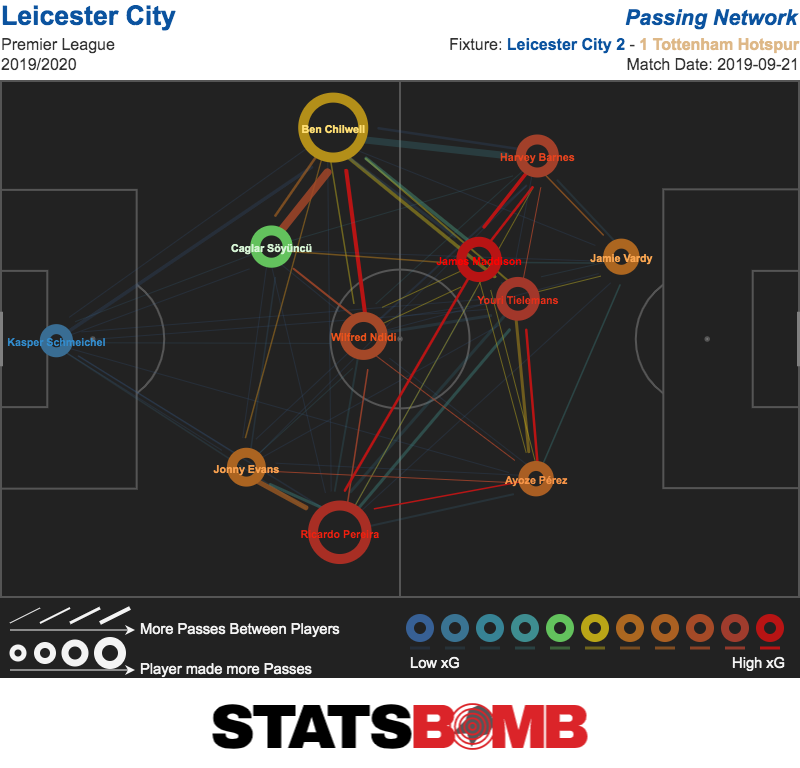

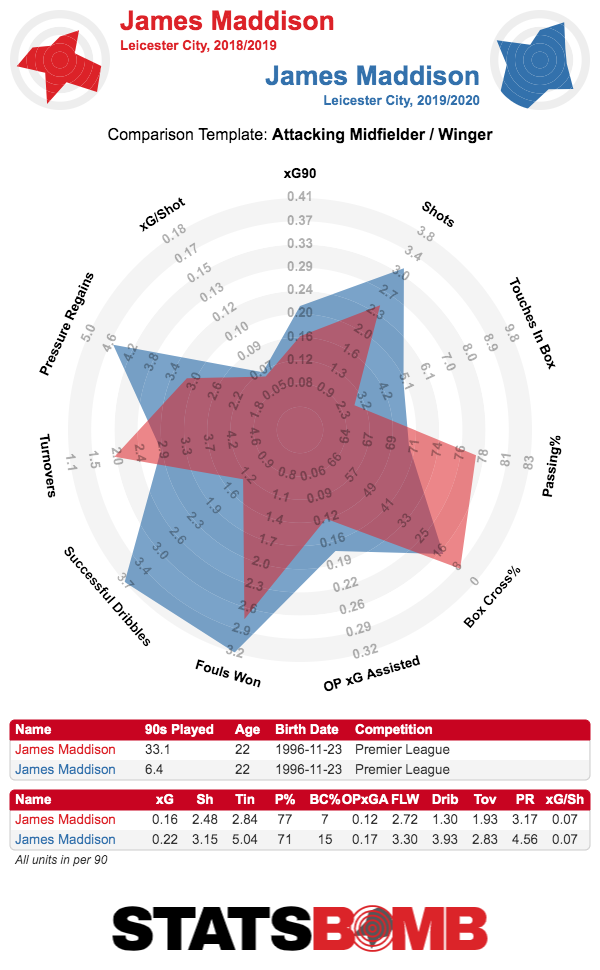

For whatever reason, Rodgers made the decision to concentrate on defensive stoutness in the opening part of the season. But some hope has come recently for a more progressive football. Leicester returned to starting Maddison and Tielemans as free eights in the win against Tottenham, with Harvey Barnes and Perez wide. The passmap below shows how willing Maddison and Tielemans were to push up, making it a genuine 4-1-4-1 in possession.  That Rodgers was willing to role this out against a “big” team like Tottenham shows a bravery that has been lacking previously this season. That it worked should hopefully encourage him to do it again. The Tielemans/Maddison axis has been a real positive of Rodgers’ time at the King Power Stadium, and it would be frustrating to see Choudhury continually shoehorned in. Maddison in particular looks like he’s on the cusp of a breakout season. There are still questions about his tactical role, and it feels like Rodgers is more likely to encourage him to flourish than try to teach him a stricter positional understanding. This could hurt him later in his career (see: Coutinho, Philippe), but for now, it’s hard to deny that he’s awfully exciting to watch in full flight. When looking at his profile compared to last season, it definitely seems like he's enjoying the freedom.

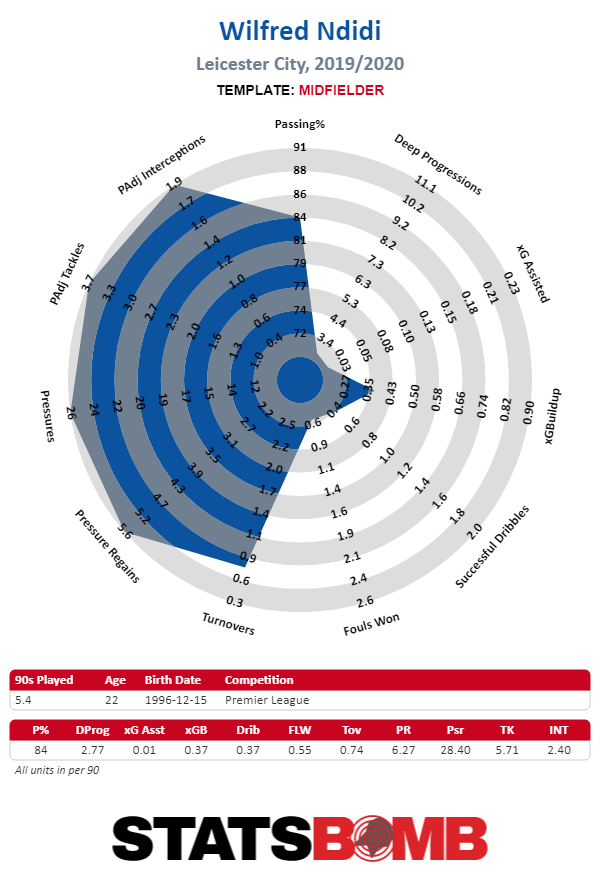

That Rodgers was willing to role this out against a “big” team like Tottenham shows a bravery that has been lacking previously this season. That it worked should hopefully encourage him to do it again. The Tielemans/Maddison axis has been a real positive of Rodgers’ time at the King Power Stadium, and it would be frustrating to see Choudhury continually shoehorned in. Maddison in particular looks like he’s on the cusp of a breakout season. There are still questions about his tactical role, and it feels like Rodgers is more likely to encourage him to flourish than try to teach him a stricter positional understanding. This could hurt him later in his career (see: Coutinho, Philippe), but for now, it’s hard to deny that he’s awfully exciting to watch in full flight. When looking at his profile compared to last season, it definitely seems like he's enjoying the freedom.  And the reason Leicester are able to compensate for Maddison’s chaotic nature, even when Choudhury isn’t on the pitch, is just how much work Ndidi manages to get through. He knows what his job is in this team. He does it. A lot. There’s not much more to it than that.

And the reason Leicester are able to compensate for Maddison’s chaotic nature, even when Choudhury isn’t on the pitch, is just how much work Ndidi manages to get through. He knows what his job is in this team. He does it. A lot. There’s not much more to it than that.  The biggest question for Leicester is whether Rodgers will trust Ndidi to just do his thing here. We haven’t seen a lot of new signing Dennis Praet yet, but it seems like the idea is for him to play the Choudhury role with a little more threat on the ball, and that would be a shame. On the attacking side of the ball, Leicester have the balance right with two central creators in Maddison and Tielemans, and two direct running wide players either side of Vardy. Swapping out a runner for a more patient central midfielder like Praet or Choudhury can make the side too slow in the build up, and lead to periods of stale possession. This is a fine option in certain situations, but shouldn’t be the primary tactic. Rodgers is a fidgety manager. Every time he seems to have settled on something, even something that’s working really well, he gets bored and changes it. He came up with a core shape straight away at the King Power, but has subsequently tweaked it to add more midfield solidity. It’s a strange tradeoff that seems to play against the strengths of the side. As the season goes on, he will certainly play around with the system some more, but this could be a positive for Leicester. He’s built himself a flexible squad of players who can fill a variety of roles, and it’s likely we’ll see all manner of formations this year. Rodgers’ methods tend to maximise players’ output for the first year or two before he starts to run out of solutions, so that would suggest this year is the window for Leicester. It would only take one of Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea or Tottenham to fail to solve any of their problems and have a poor season for a top six spot to really open up. That, combined with Leicester keeping it together, would be the recipe for a very successful season for the Foxes.

The biggest question for Leicester is whether Rodgers will trust Ndidi to just do his thing here. We haven’t seen a lot of new signing Dennis Praet yet, but it seems like the idea is for him to play the Choudhury role with a little more threat on the ball, and that would be a shame. On the attacking side of the ball, Leicester have the balance right with two central creators in Maddison and Tielemans, and two direct running wide players either side of Vardy. Swapping out a runner for a more patient central midfielder like Praet or Choudhury can make the side too slow in the build up, and lead to periods of stale possession. This is a fine option in certain situations, but shouldn’t be the primary tactic. Rodgers is a fidgety manager. Every time he seems to have settled on something, even something that’s working really well, he gets bored and changes it. He came up with a core shape straight away at the King Power, but has subsequently tweaked it to add more midfield solidity. It’s a strange tradeoff that seems to play against the strengths of the side. As the season goes on, he will certainly play around with the system some more, but this could be a positive for Leicester. He’s built himself a flexible squad of players who can fill a variety of roles, and it’s likely we’ll see all manner of formations this year. Rodgers’ methods tend to maximise players’ output for the first year or two before he starts to run out of solutions, so that would suggest this year is the window for Leicester. It would only take one of Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea or Tottenham to fail to solve any of their problems and have a poor season for a top six spot to really open up. That, combined with Leicester keeping it together, would be the recipe for a very successful season for the Foxes.

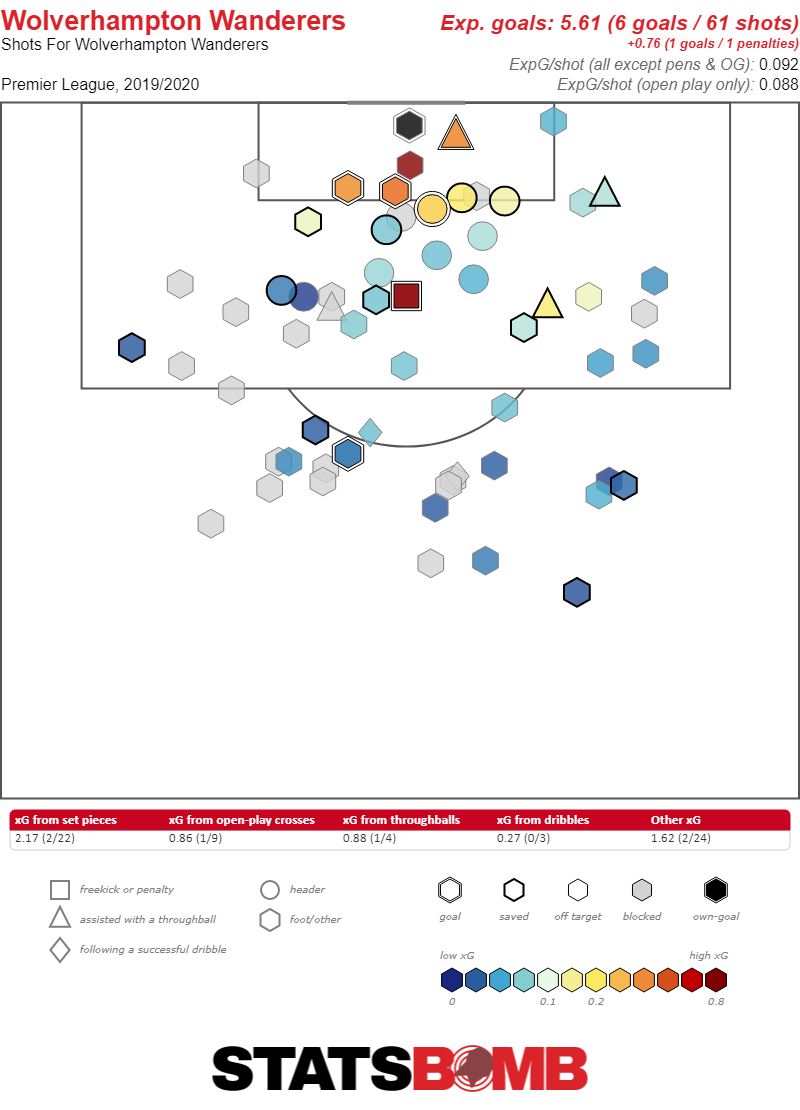

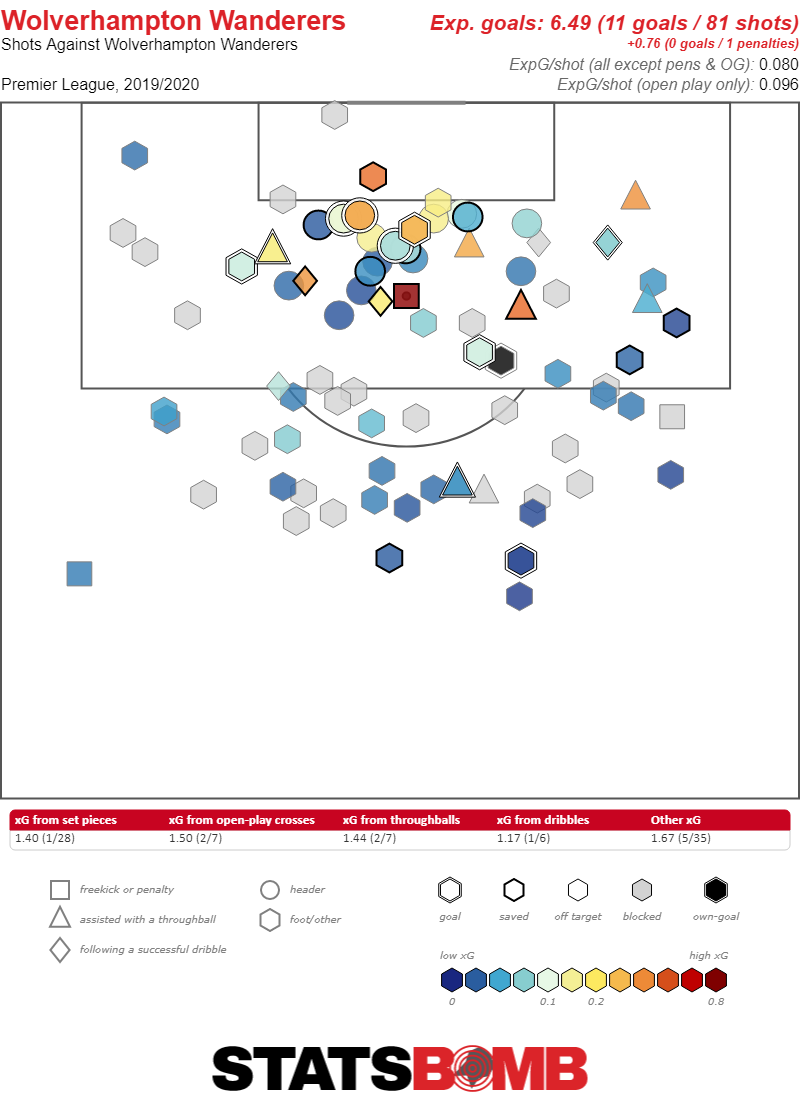

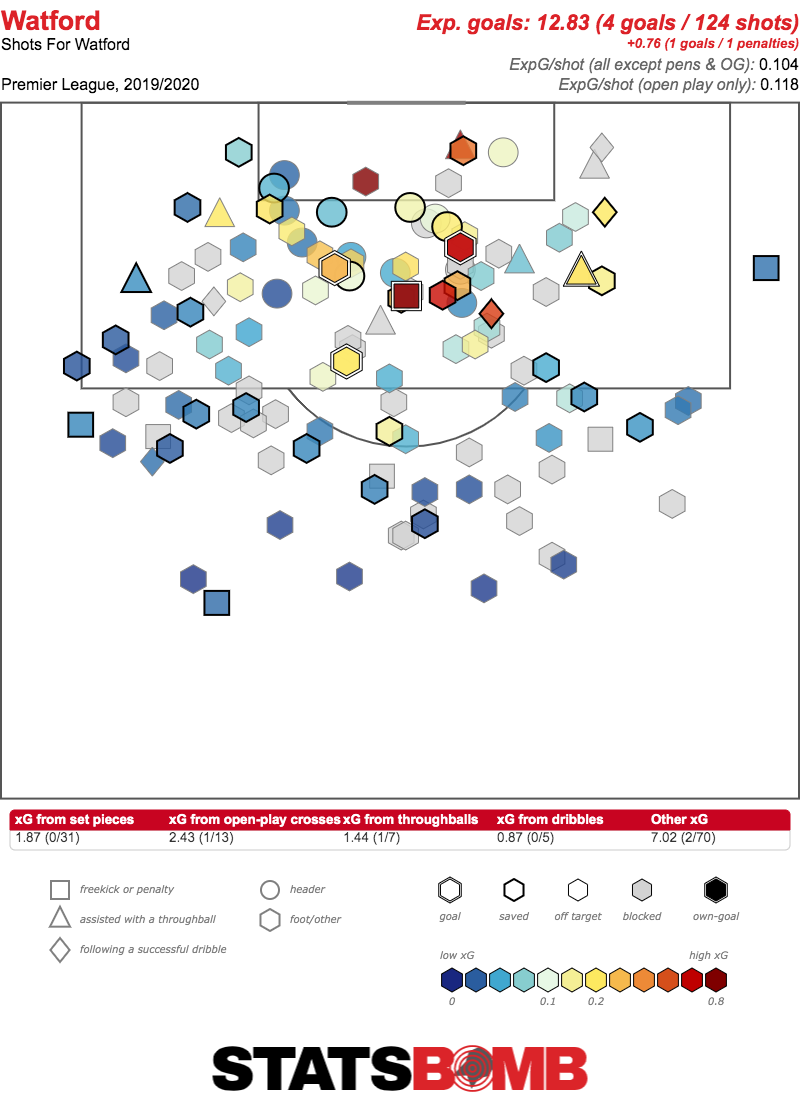

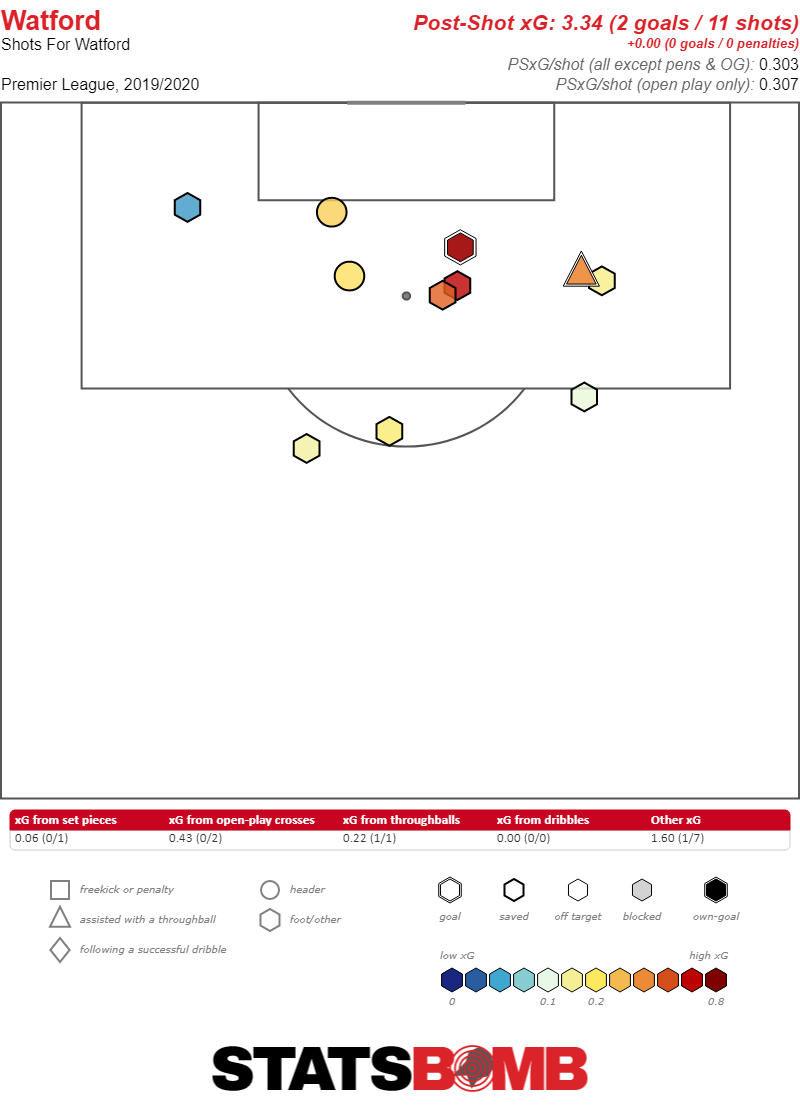

Things are not great in Wolverhampton. Wolves sit second to the last in the table, one of only two teams without a victory. Only fellow winless side Watford are preventing them from sitting in dead last. This was a team that finished seventh best last season, with numbers that were arguably better than that. So what’s going on? Is it time for Wolves to panic? The first place to look, as always, is at the expected goals. There’s some good news here for Wolves. In attack they’re basically running at xG with six goals for against 5.61 xG (plus a penalty).  On the defensive side of the ball is where the good news is. Sure they’ve given up 11 goals, but only 6.49 expected goals. That’s exactly the kind of performance you’d expect to see turn around without doing too much of anything different.

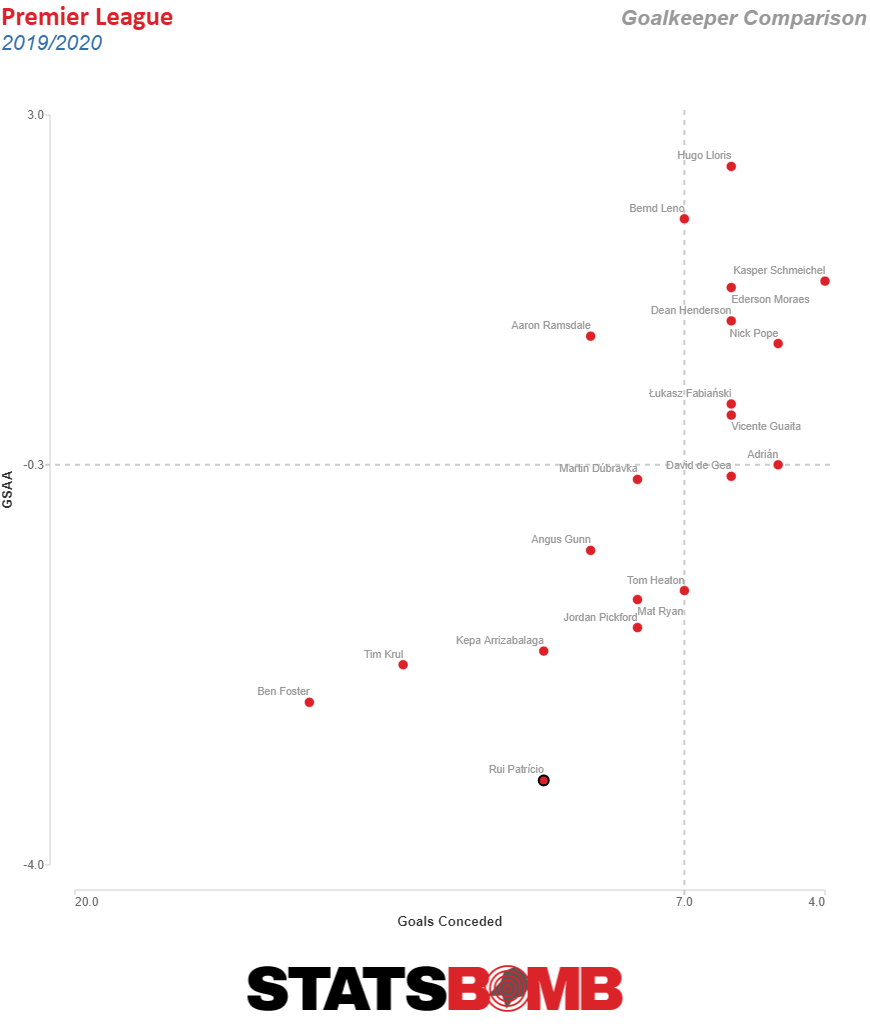

On the defensive side of the ball is where the good news is. Sure they’ve given up 11 goals, but only 6.49 expected goals. That’s exactly the kind of performance you’d expect to see turn around without doing too much of anything different.  Specifically all of that extra conceding seems like it’s down mostly to keeper So far this season he has the worst goals saved above average % of any regular starting keeper in the Premier League. He’s only saved 50% of the shots he’s faced while his expected average giving those shots is 66.1%. That’s really bad! Patricio’s -16.1 GSAA% is significantly behind Everton’s Jordan Pickford at -9.9% and Chelsea’s Kepa Arrizabalaga’s -9.1%.

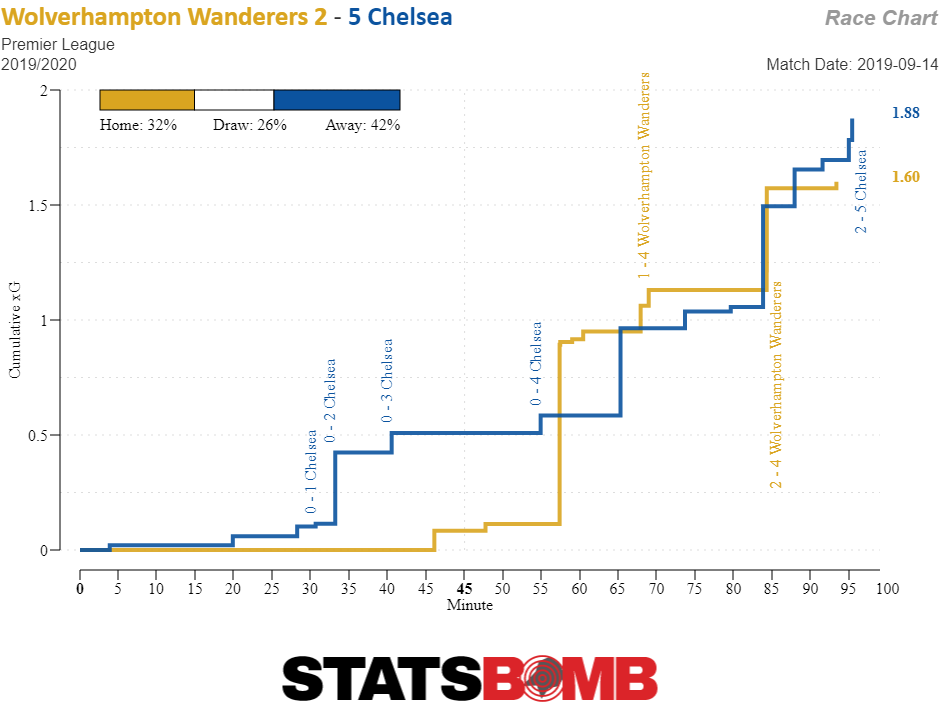

Specifically all of that extra conceding seems like it’s down mostly to keeper So far this season he has the worst goals saved above average % of any regular starting keeper in the Premier League. He’s only saved 50% of the shots he’s faced while his expected average giving those shots is 66.1%. That’s really bad! Patricio’s -16.1 GSAA% is significantly behind Everton’s Jordan Pickford at -9.9% and Chelsea’s Kepa Arrizabalaga’s -9.1%.  Encouragingly for Wolves, last year Patricio’s was almost exactly flat against expectation. He saved 71% of shots and was expected to save 71.1%. So this horrible form will probably work itself out. They don’t need him to be great this season, they just need him to be fine. So far, he hasn’t been, but there’s not a ton of reason to suspect he won’t be going forward. So that’s the good news. Here’s the bad news. Even adjusting for the unexpected defensive lapses, Wolves haven’t been nearly as good as last season. Last season StatsBomb had their xG difference at 0.28 per match, virtually tied with Spurs for the fourth best in the Premier League. This season, so far it’s dropped to -0.16. That’s not nearly bad enough to be where they are in the table, but it’s not in any way remarkable. It’s just outside the top half of the table (and interestingly enough again virtually tied with Spurs). That difference amounts to almost half a goal per match, or just under three goals in six games. For a team that’s drawn four times and lost another match by a single goal, that’s a massive difference. Their sixth match, a 2-5 home defeat to Chelsea was one of the wilder mostly balanced xG matches you will find.

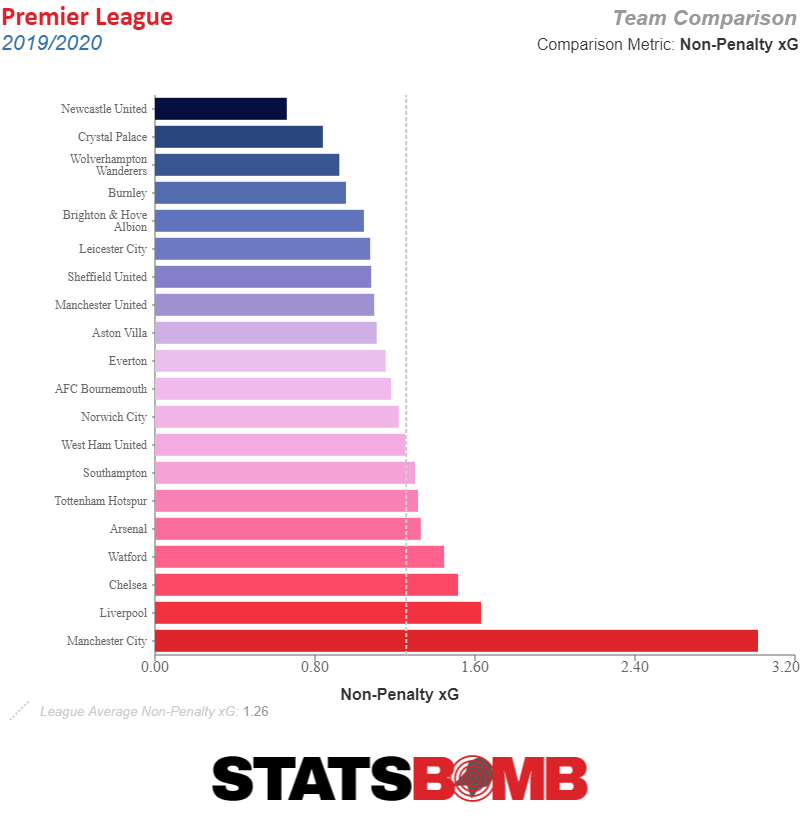

Encouragingly for Wolves, last year Patricio’s was almost exactly flat against expectation. He saved 71% of shots and was expected to save 71.1%. So this horrible form will probably work itself out. They don’t need him to be great this season, they just need him to be fine. So far, he hasn’t been, but there’s not a ton of reason to suspect he won’t be going forward. So that’s the good news. Here’s the bad news. Even adjusting for the unexpected defensive lapses, Wolves haven’t been nearly as good as last season. Last season StatsBomb had their xG difference at 0.28 per match, virtually tied with Spurs for the fourth best in the Premier League. This season, so far it’s dropped to -0.16. That’s not nearly bad enough to be where they are in the table, but it’s not in any way remarkable. It’s just outside the top half of the table (and interestingly enough again virtually tied with Spurs). That difference amounts to almost half a goal per match, or just under three goals in six games. For a team that’s drawn four times and lost another match by a single goal, that’s a massive difference. Their sixth match, a 2-5 home defeat to Chelsea was one of the wilder mostly balanced xG matches you will find.  Last season Wolves were a great defensive team. They were one of only four teams to concede fewer than one xG per match (0.91). They were also a decent attacking side. They accumulated 1.19 xG per match, which is nothing to write home about but landed them exactly in the middle of the league. This year they’re just worse on both sides of the ball. This year their defense is average, at 1.09 xG conceded, which trails eight other teams and their attack, well their attack at 0.92 xG per match is simply an utter mess.

Last season Wolves were a great defensive team. They were one of only four teams to concede fewer than one xG per match (0.91). They were also a decent attacking side. They accumulated 1.19 xG per match, which is nothing to write home about but landed them exactly in the middle of the league. This year they’re just worse on both sides of the ball. This year their defense is average, at 1.09 xG conceded, which trails eight other teams and their attack, well their attack at 0.92 xG per match is simply an utter mess.  Then there’s a matter of the schedule. They’ve played a relatively difficult set of six games so far, facing Leicester City away, Manchester United at home and Chelsea at home. Though given the sides early season aspirations those were all games they’d be expected to compete in and taking only two points is minorly disappointing. That said, if they’d taken more than two points from Burnley at home, Everton away, and Palace away nobody would have much noticed the struggles against the top teams. If Wolves had taken six points from the easy half of their schedule they’d currently be tied with the six teams sitting in seventh through 12th place. Instead they’re beginning a fledgling fight against relegation. The next month remains pretty easy for Wolves. Before the end of October the side will face fellow relegation battlers Watford at home and Newcastle away, as well as hosting Southampton (currently in 13th place). Just ignore that they fourth match in that stretch of time is against Manchester City. It’s possible that with a handful of strong performances Wolves numbers will improve, and their results will follow (especially if that is combined with their luck turning). Another month of struggling though, and the discussion slips from having a minorly disappointing season to a real relegation battle. There are, as there always are, all sorts of possible reasons for the poor start. There’s the added burden of Europa League, especially on a squad that was fairly short to begin with and didn’t add much depth this summer. Even minor rotation for a team exceptionally used to a fixed starting 11 can be disruptive. Wolves have been starting bit players from last year like Morgan Gibbs-White and giving super sub Adama Traoré starts at wingback. It’s also possible their numbers are being impacted by playing from behind so much. They’ve conceded first in five of their six matches (and the sixth was the 0-0 opening day draw against Leicester). For a team built to defend, the fact that they’ve been forced to chase the game so often might be dragging their numbers down (one might for example imagine a world where they have improved numbers because several of their draws came from late, lucky equalizers rather than what actually happened where they scored late themselves). This again is the kind of factor that generally, although not always, evens itself out as the season progresses. The bottom line for Wolves is that there is no reason to panic. The team’s defense is its calling card, and that defense has been pretty unlucky so far this season. It will likely improve as the season goes on, just by dint of getting out from whatever soccer god cloud is currently raining goals on them nonstop. That should be enough to turn them into a somewhat below average team that’s safe from relegation. After last year, however, that shouldn’t be enough for Wolves. This side was genuinely impressive last season, and they’ve come out of the gate this year looking genuinely average. Whether it’s Europa League or something else, Wolves have taken a step backwards. The fact that it won’t likely cost them relegation doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be disappointing. This was a team on a meteoric trajectory. Without some sharp improvements over the next month, they’re now overwhelmingly likely to be just another midtable side.

Then there’s a matter of the schedule. They’ve played a relatively difficult set of six games so far, facing Leicester City away, Manchester United at home and Chelsea at home. Though given the sides early season aspirations those were all games they’d be expected to compete in and taking only two points is minorly disappointing. That said, if they’d taken more than two points from Burnley at home, Everton away, and Palace away nobody would have much noticed the struggles against the top teams. If Wolves had taken six points from the easy half of their schedule they’d currently be tied with the six teams sitting in seventh through 12th place. Instead they’re beginning a fledgling fight against relegation. The next month remains pretty easy for Wolves. Before the end of October the side will face fellow relegation battlers Watford at home and Newcastle away, as well as hosting Southampton (currently in 13th place). Just ignore that they fourth match in that stretch of time is against Manchester City. It’s possible that with a handful of strong performances Wolves numbers will improve, and their results will follow (especially if that is combined with their luck turning). Another month of struggling though, and the discussion slips from having a minorly disappointing season to a real relegation battle. There are, as there always are, all sorts of possible reasons for the poor start. There’s the added burden of Europa League, especially on a squad that was fairly short to begin with and didn’t add much depth this summer. Even minor rotation for a team exceptionally used to a fixed starting 11 can be disruptive. Wolves have been starting bit players from last year like Morgan Gibbs-White and giving super sub Adama Traoré starts at wingback. It’s also possible their numbers are being impacted by playing from behind so much. They’ve conceded first in five of their six matches (and the sixth was the 0-0 opening day draw against Leicester). For a team built to defend, the fact that they’ve been forced to chase the game so often might be dragging their numbers down (one might for example imagine a world where they have improved numbers because several of their draws came from late, lucky equalizers rather than what actually happened where they scored late themselves). This again is the kind of factor that generally, although not always, evens itself out as the season progresses. The bottom line for Wolves is that there is no reason to panic. The team’s defense is its calling card, and that defense has been pretty unlucky so far this season. It will likely improve as the season goes on, just by dint of getting out from whatever soccer god cloud is currently raining goals on them nonstop. That should be enough to turn them into a somewhat below average team that’s safe from relegation. After last year, however, that shouldn’t be enough for Wolves. This side was genuinely impressive last season, and they’ve come out of the gate this year looking genuinely average. Whether it’s Europa League or something else, Wolves have taken a step backwards. The fact that it won’t likely cost them relegation doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be disappointing. This was a team on a meteoric trajectory. Without some sharp improvements over the next month, they’re now overwhelmingly likely to be just another midtable side.

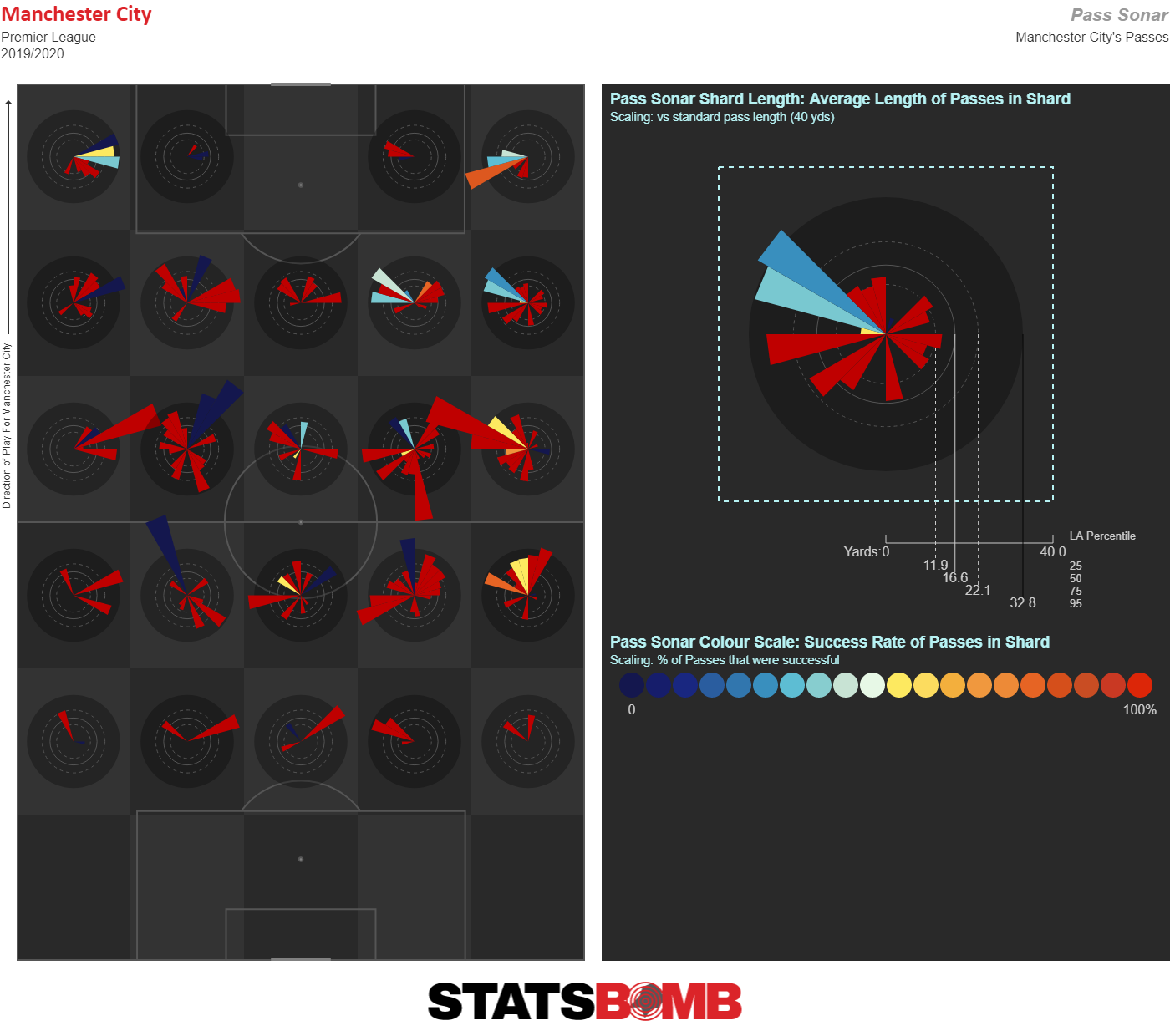

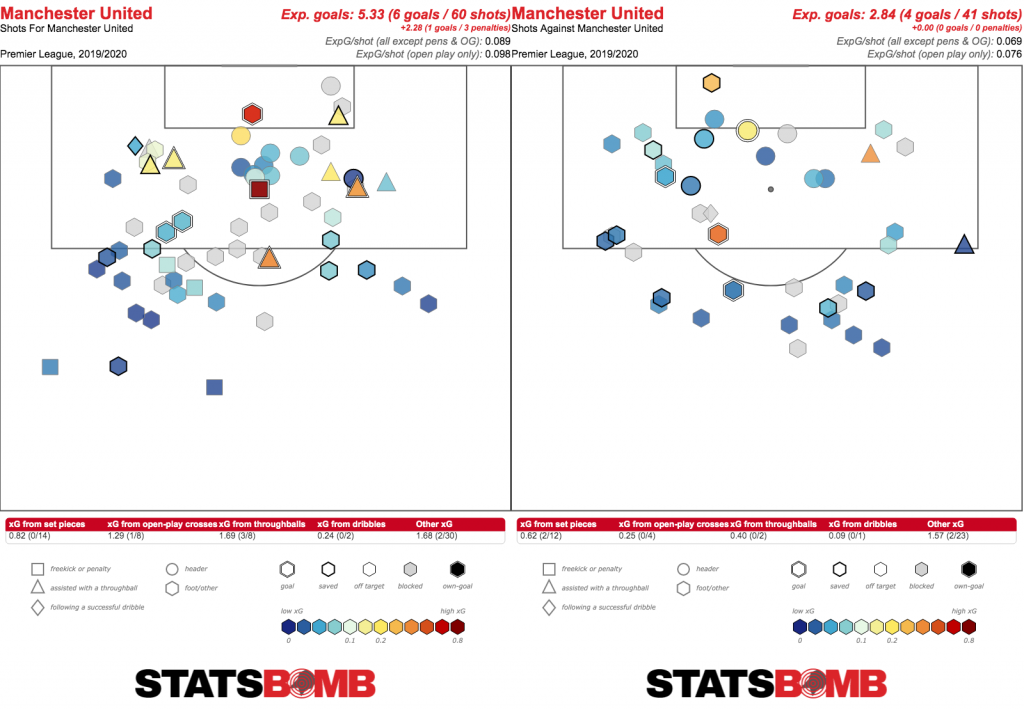

Pep Guardiola has a way of creating attacking patterns that are easy to predict, but almost impossible to stop.

At all his clubs Guardiola has devised schemes in the final third that his teams keep repeating, and that keep coming off. At Barcelona, especially in the early days, Lionel Messi would keep dragging the left-back inside and leave space for Dani Alves to attack, often set up by a floating Xavi diagonal pass. At Bayern Munich, Guardiola moved full-backs Philipp Lahm and David Alaba inside to control the game. These moves accentuated the qualities of the key players, created numerical overloads in crucial areas and enabled Guardiola to move his best players into the centre. At Manchester City the Catalan has achieved the same by using Kevin De Bruyne as a central midfielder.

By now the two have worked together for three years, and so most know how De Bruyne moves, yet he seems more dangerous than ever. In six league games he has scored two goals and notched seven assists. Few will be surprised to see him top the Premier League list for open-play key passes and passes into the box per 90 minutes, but his expected assists rate from open play is striking even by his standards: his average is 0.73. The next on the list in the league is Mahrez, with 0.44. The radar below fails to do De Bruyne justice: the scale of his creativity is literally off the charts.

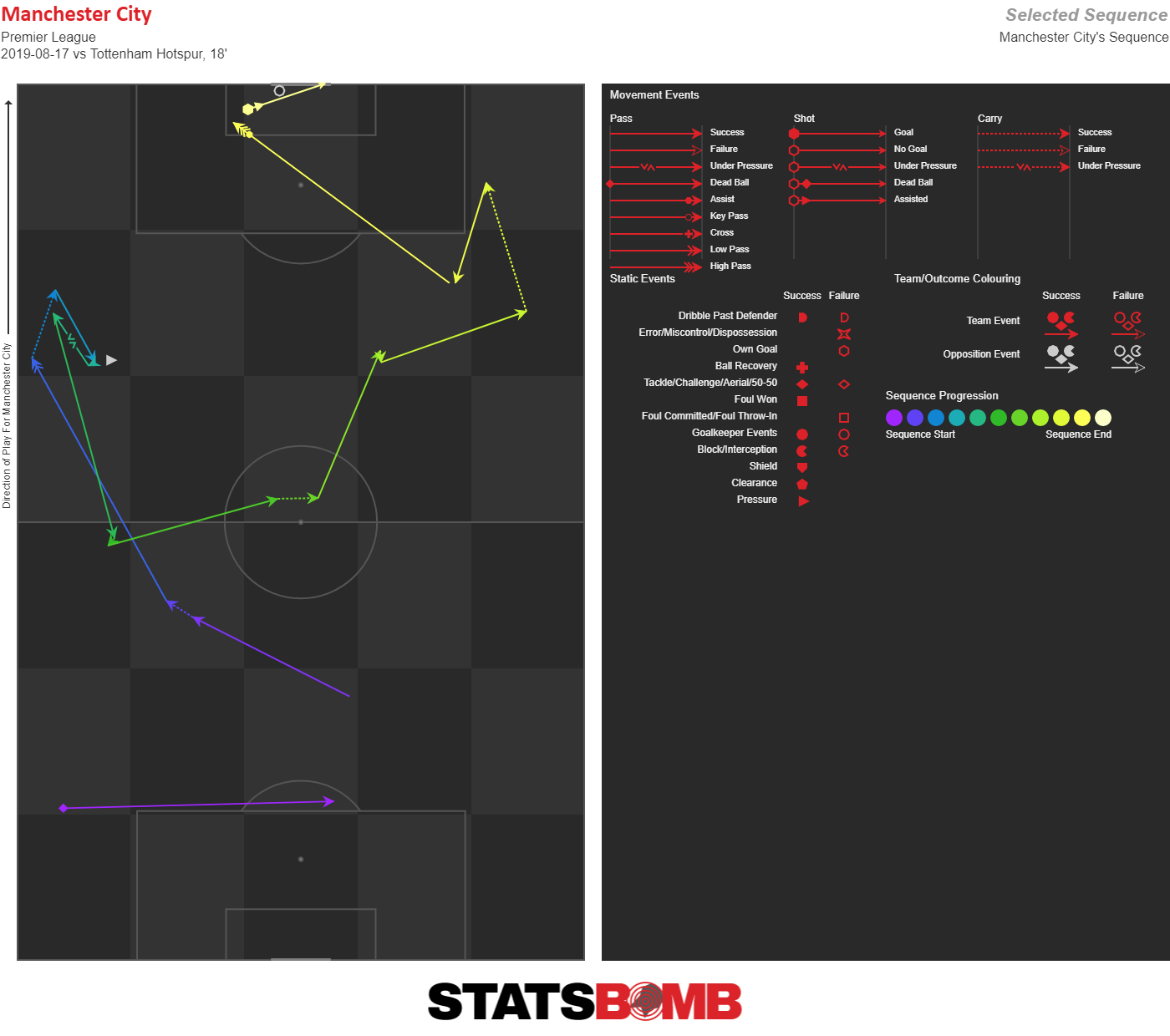

Part of what makes De Bruyne hard to stop is that Guardiola has put a player with such extreme attacking qualities in a conservative staring position. Most teams facing City will ask a central midfielder to track De Bruyne. When De Bruyne then moves out wide, it takes an unusually alert and rapid player to track him, and it’s likely to mean trouble for most players not named N’Golo Kanté. Even if the central midfielder does track De Bruyne, the rest of the team can be dragged out shape. On Saturday the way in which De Bruyne drifted out wide was representative of his movement so far this season.

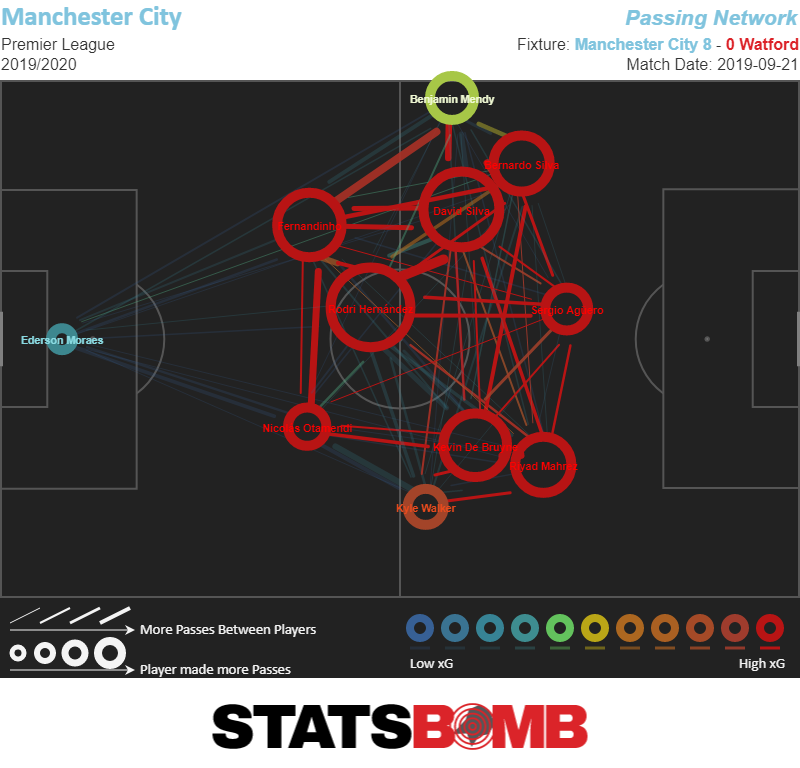

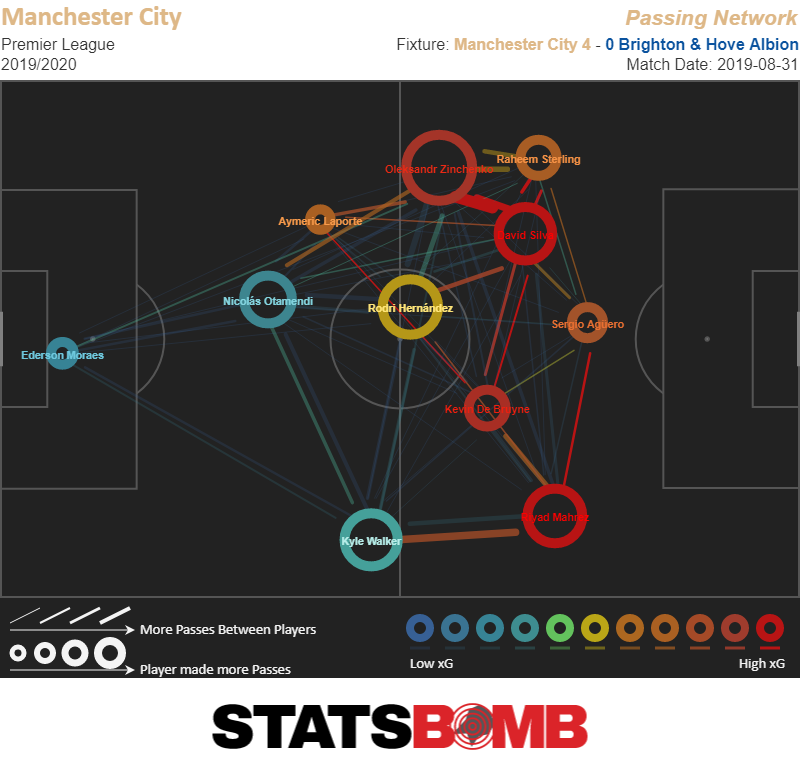

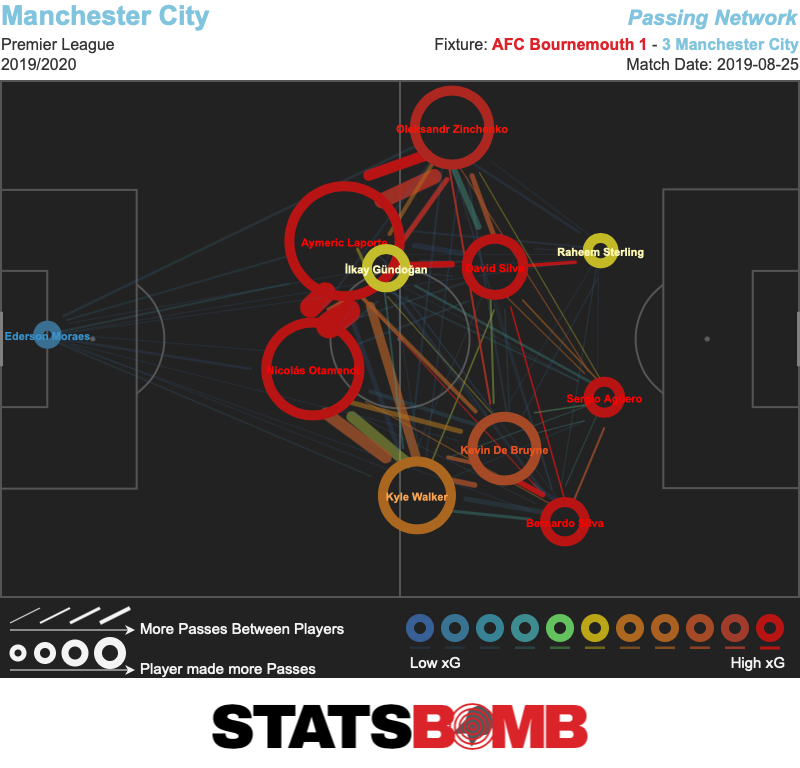

The graphic shows the tactical harmony with which Guardiola has set up his team. City tend to move slightly towards the left, because they build more of their attacks down that side: last season Oleksandr Zinchenko averaged 92.4 passes per 90, Kyle Walker 77.4. Some reasons might be that Aymeric Laporte, the most gifted centre back, plays on that side, and that David Silva is a master at linking up in small spaces, as opposed to De Bruyne, whose longer legs need more space. Look closely at the map above and you see that Rodri sends the ball far more often to Silva than to De Bruyne. The same happened the previous game in which De Bruyne started, at home to Brighton, even though he played in an unusually central role here. In total Rodri has sent 38 passes to Silva and 24 to De Bruyne this season.

Thus, it will surprise nobody that Silva has played more passes per 90 this season (69.2) than De Bruyne (56.3). Not only does it exploit Silva’s nimble feet and clever movement in small spaces, but it opens up more space for De Bruyne once the ball is shifted to the right. The trigger will often be a diagonal pass, and before the opposition have managed to move their team across, De Bruyne will have made a run or a decisive cross.

Meanwhile Silva will join the striker and the left winger in moving into the centre, anticipating the delivery from wide, which is part of the reason why Silva has nearly twice as many touches in the box per 90 (11.96) as De Bruyne (6.11). On Saturday all these factors came together in the opening goal: City started the attack on the left, then switched the ball over to De Bruyne, who swung in a cross for Silva who scored from close range.

Whenever the ball reaches De Bruyne on the right, City tend to follow a small number of specific patterns. One is the deep cross, as with Silva’s goal. If the precision of these crosses is astonishing, the timing of the runs is too. There was another big chance in the first half against Watford that came when Fernandinho floated a diagonal pass to Bernardo Silva, who was making a rare appearance on the right. As the ball traveled towards Bernardo, De Bruyne was already positioning himself in order to receive the support pass.

At the very moment that Bernardo sent the ball back to De Bruyne, on the edge of the box, Sergio Agüero darted towards the far post, certain that De Bruyne would 1) whip the ball in first time and 2) place it right on his head. Of course De Bruyne did so, and Agüero should have scored with his close-range header. Though Watford had three defenders well-positioned in the box, the speed and timing of the move made it difficult for any of them to track Agüero.

Earlier this season, when City drew 2-2 at home against Tottenham, City scored with this move, only with Sterling popping up at the far post instead of Agüero. The rest was identical: City move the ball from the left to the right, Bernardo then passed it back to De Bruyne, who swung in a cross from the edge of the box towards the far post.

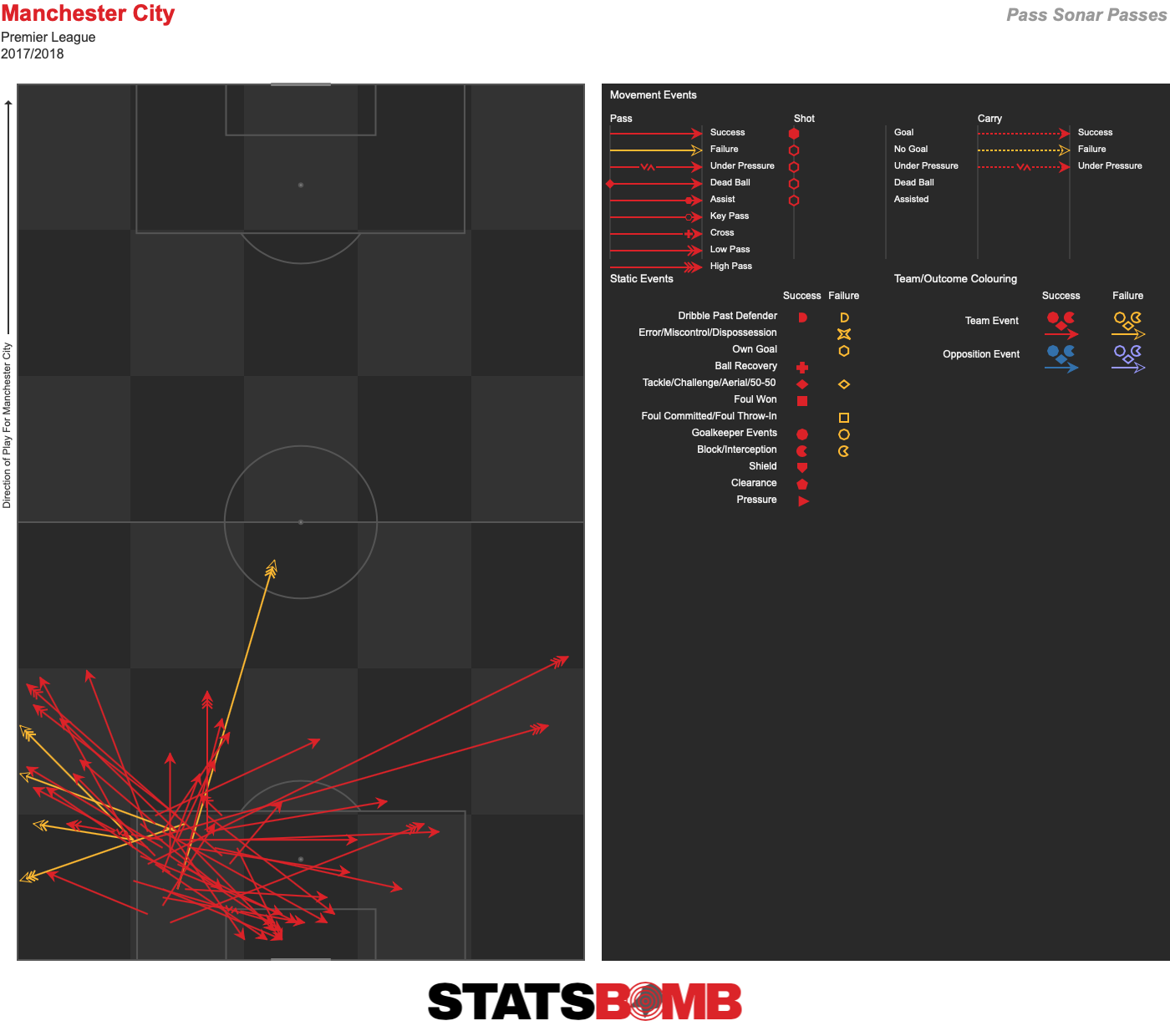

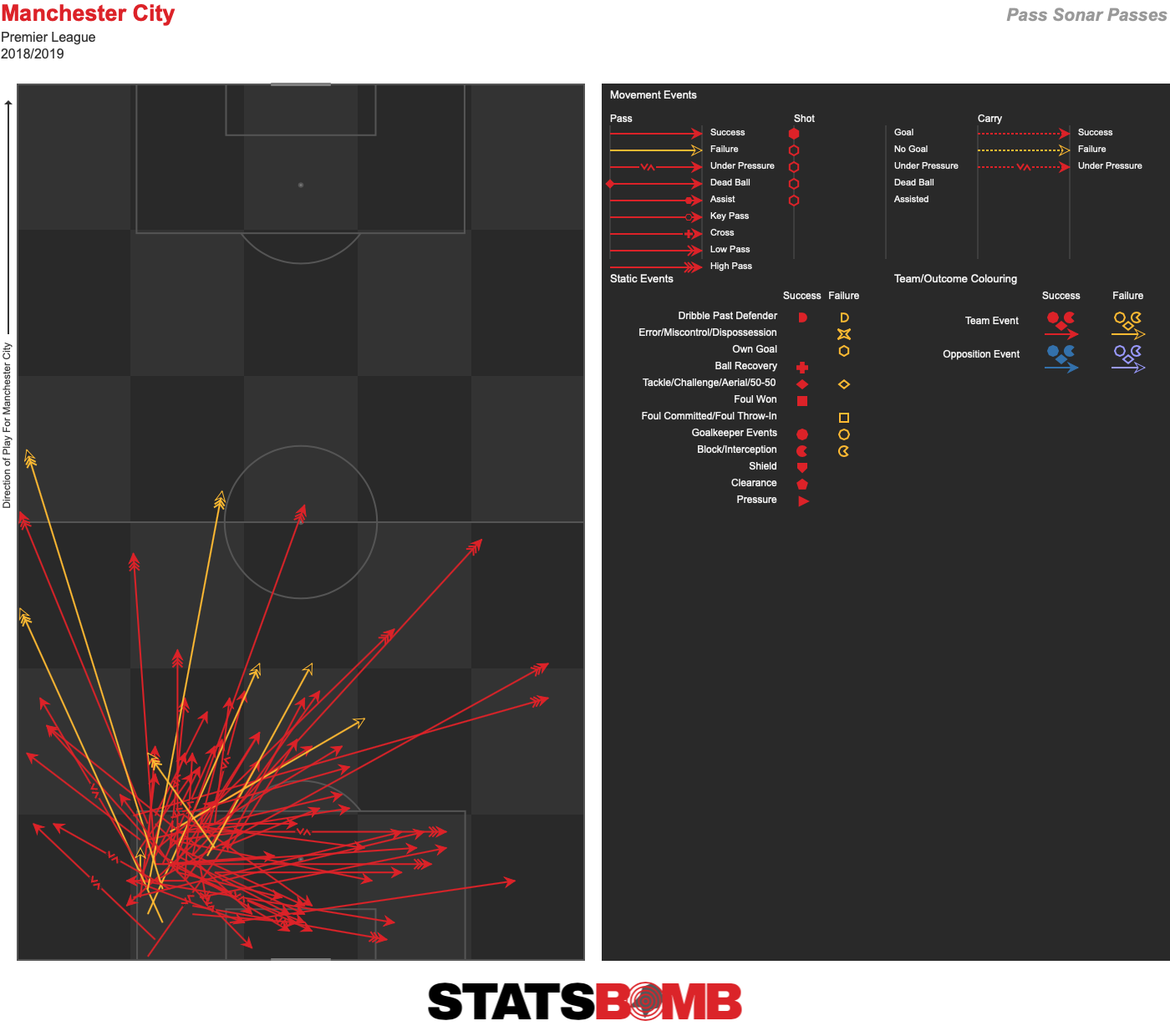

These moves are not only hard to stop because City can pull them off blindfolded; they also originate from areas that would otherwise be fairly harmless. Against most teams the alarm bells are hardly ringing if a midfielder has the ball out wide on 30 yards, yet with De Bruyne this is lethal, and City keep exploiting it. His passing sonar shows how direct his distribution is outside the box.

Beyond the deep cross De Bruyne also makes runs in behind the defence, such as when he assisted Bernardo in the second half on Saturday. Again this is a well-rehearsed move, and there are plenty of other examples. Typically the right winger will get the ball by the touchline, then find De Bruyne, who has moved in behind the left-back too quickly for any central midfielders to follow him. Since both Bernardo and Mahrez are left-footed, they can make this pass to De Bruyne with ease.

On Saturday it was Mahrez who played this pass, enabling De Bruyne to fire a low cross towards the far post. Here Raheem Sterling tends to produce a tap-in. That the player who appeared in this zone on Saturday was his direct replacement, Bernardo, shows how deeply Guardiola has drilled these patterns into the team. So how do you stop De Bruyne? There are few obvious answers. You can try to press high and shut off the supply, but good luck doing that against City. If you want to sit deep and keep the lines close together, you need centre backs who can deal with the deep crosses. Perhaps the best way is to use a back three, so that the left-sided centre-back can pick up De Bruyne’s runs.

Coincidentally or not, the only coach who has beaten Guardiola’s City in a league game at the Etihad in which De Bruyne has started is Antonio Conte, who set Chelsea up in a 5-4-1. In any case, Conte is gone and De Bruyne looks certain to be a menacing presence throughout the season. That City’s rivals know what’s coming is unlikely to be of much consolation.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association

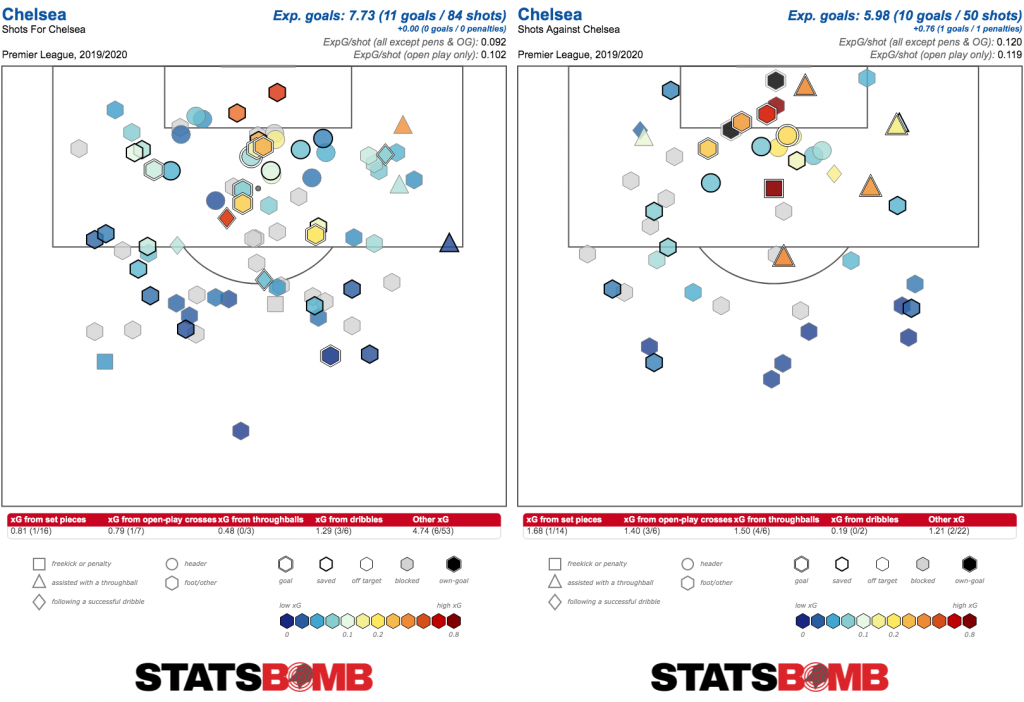

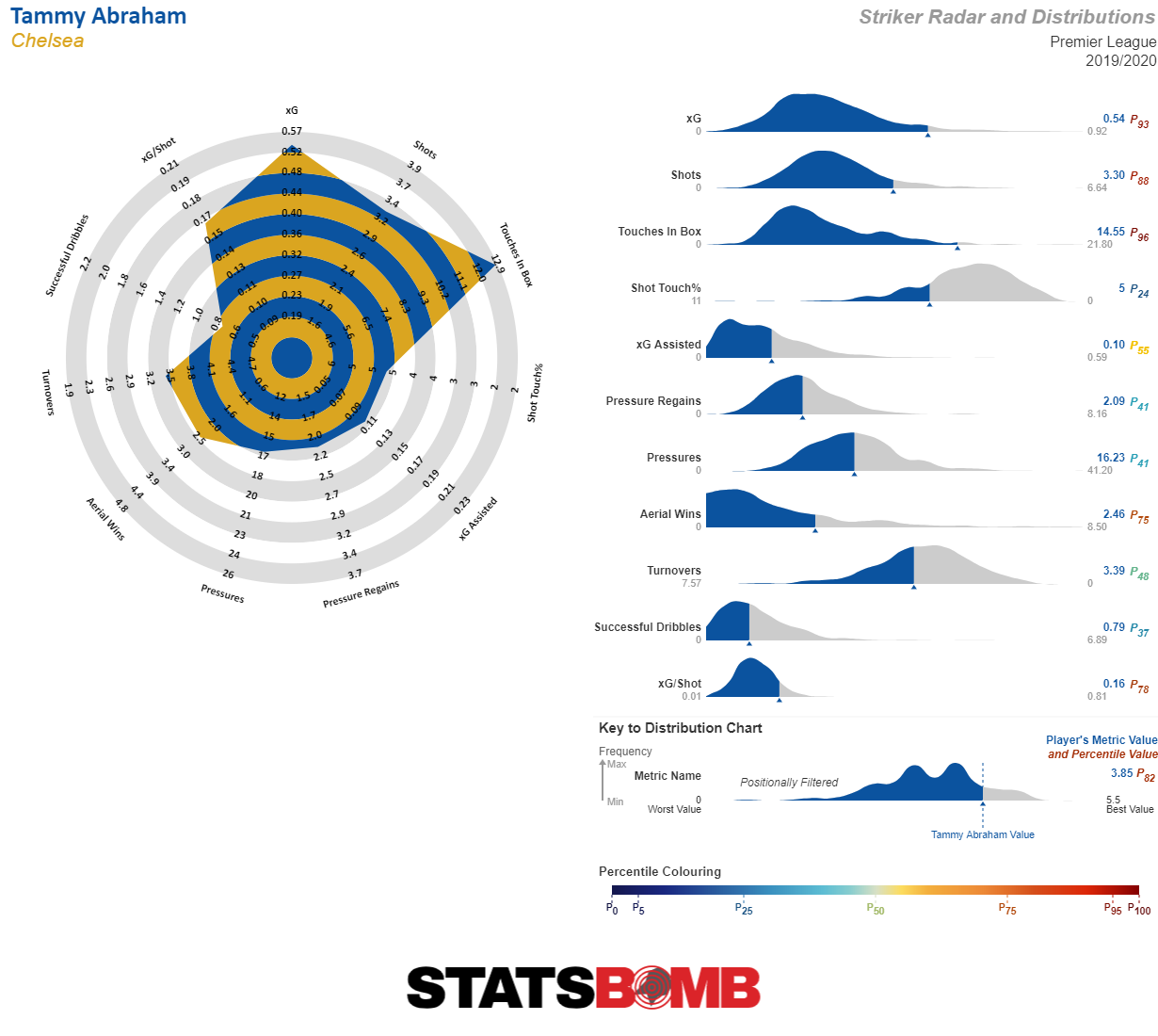

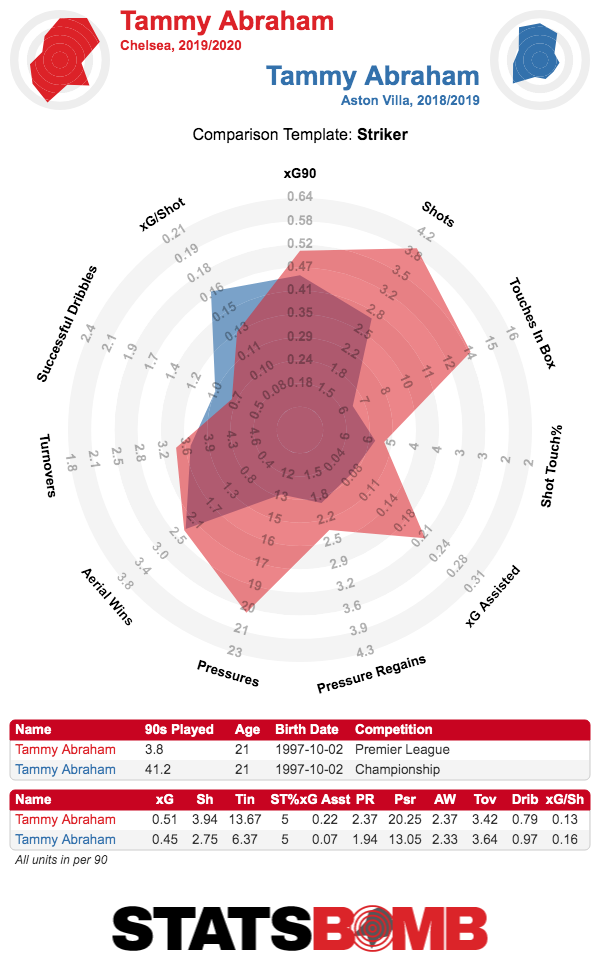

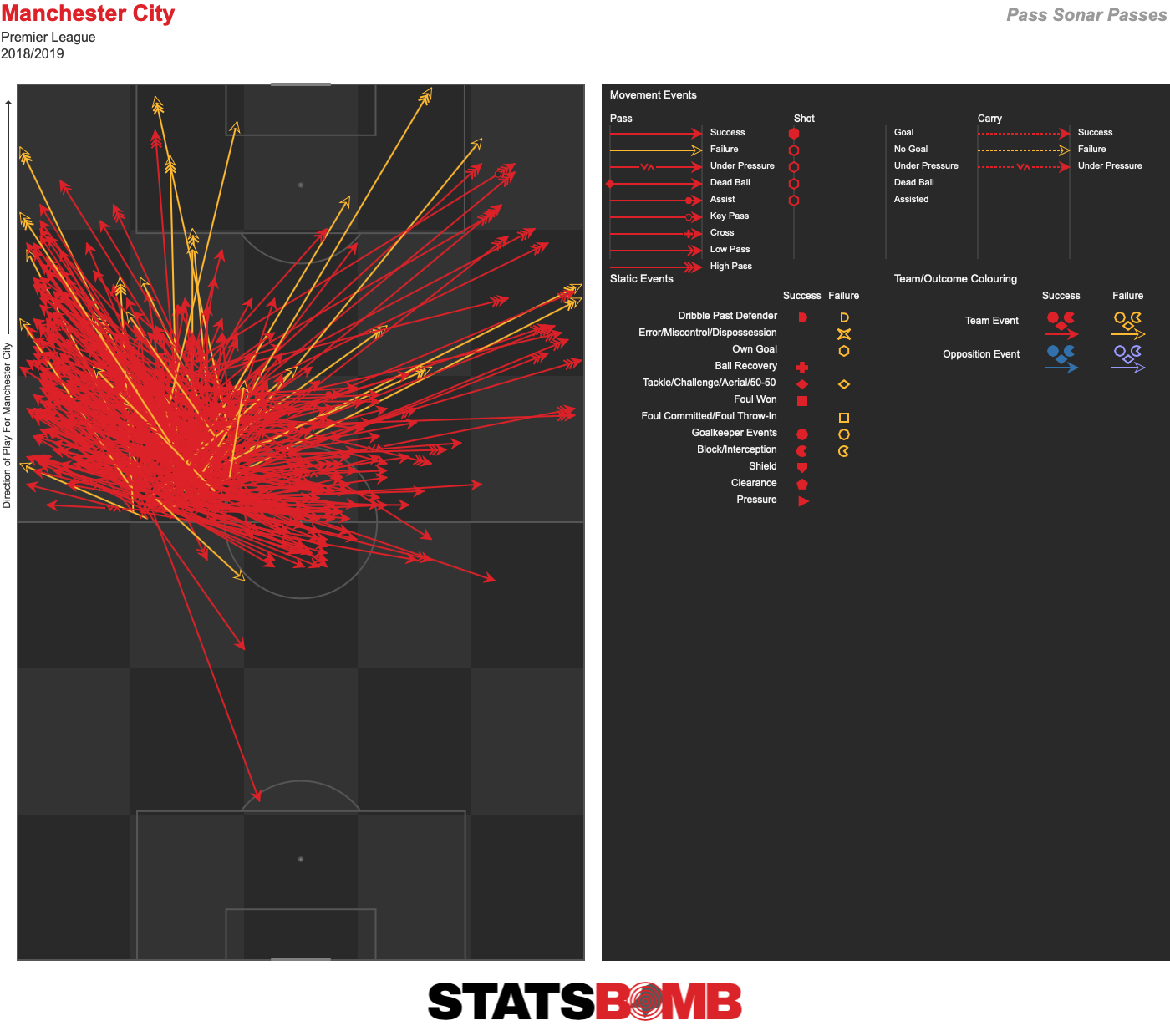

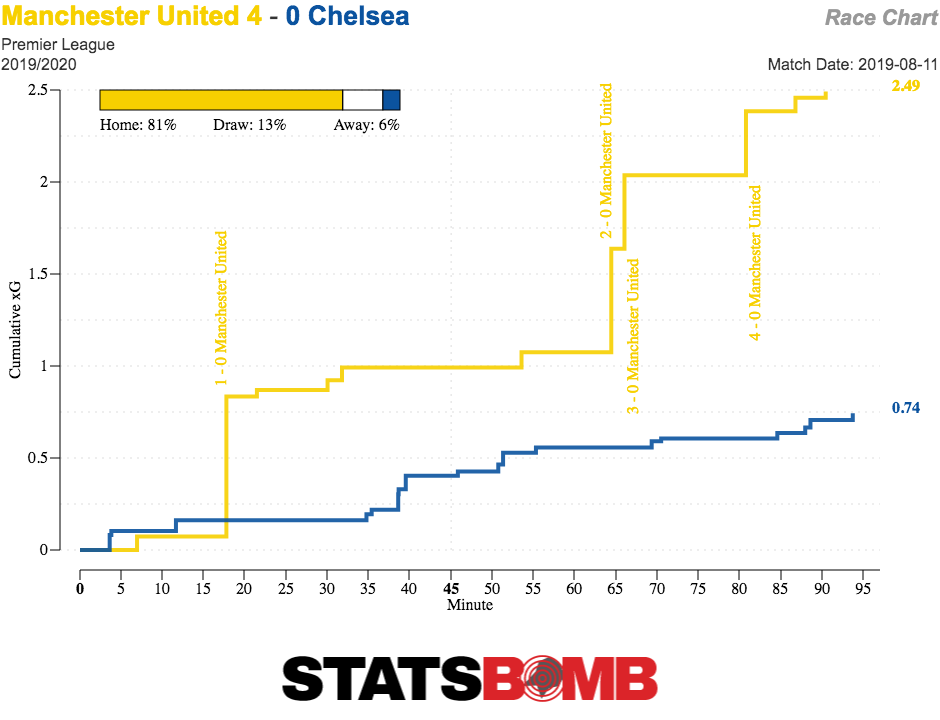

It’s the thing everyone has been asking top Premier League sides to do for years, and Chelsea have done it. “Play the kids, that 30 year old is over the hill”. “Give young English players chances”. “Stop making expensive signings when you’ve already got a young player who can come in”. The top six have all received these kinds of comments, but none more than Chelsea. And it’s not hard to see why. Look at the England youth squads in recent years and the Blues produce many more players than any other club. The Chelsea academy is a machine, sucking up so much talent from London and the South East and churning out excellent young footballers. Of course, everyone loves saying it until it actually happens. At which point people remember that young players are youthful and inexperienced. Frank Lampard’s early steps as Chelsea manager have seen exactly the kind of blend of enthusiastic fun and questionable defensive errors anyone would expect from a team in this kind of situation. The expected goals tell a story. Overall, Chelsea are landing about where you’d expect, but through wild overperformance on the attacking end and underperformance defensively.  Is this genuinely evidence of what the team is doing or just one of those things that we shouldn’t expect to continue? That remains to be seen. This team does have something of the feel of Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool in 2016/17, who seemed to be wide open in a way that the xG models couldn’t quite grasp. The very high xG per shot conceded suggests there might be something happening here. But it is, of course, entirely possible that this is nothing and we will see a more normal finishing rate at both ends going forward. On the attacking side, all the talk has been about the kids. It’s a nice stat that all of Chelsea’s goals this season have been scored by academy graduates, even if the numbers paint this as somewhat unlikely (“the rest” have taken a combined xG of 3.92 without yet finding the back of the net). One could only describe Tammy Abraham’s current form as on fire, sitting as the joint top scorer in the Premier League with seven. The negative takeaway is that he’s overperforming xG by a fairly comical margin and yes, he will slow down a bit. He’s not going to score a goal every 49 minutes. But even so, he’s still getting a decent number of shots away in good positions. It doesn’t look like there have been any issues in transferring his Championship form to the top flight.

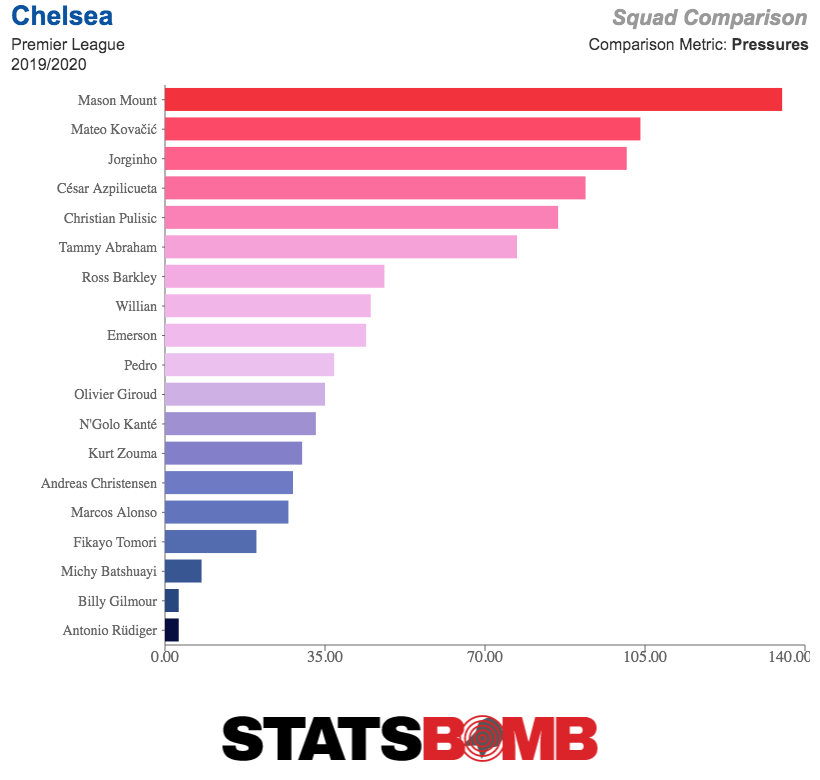

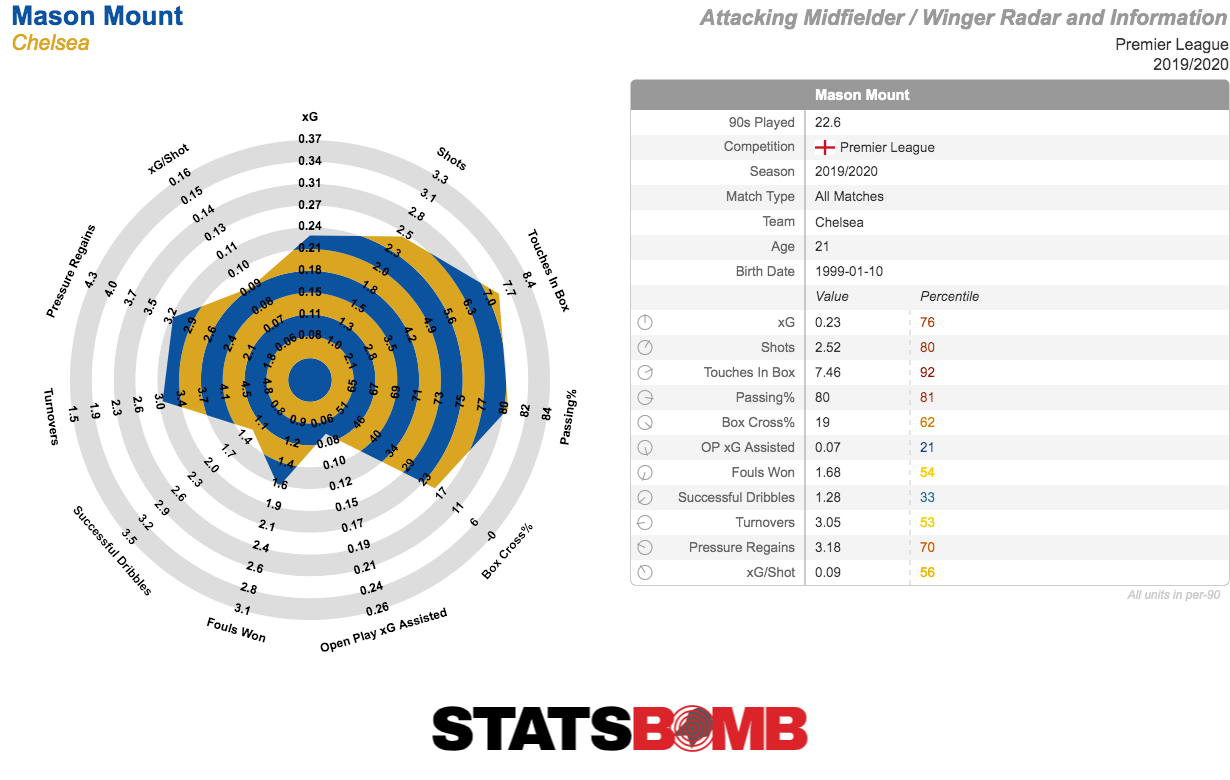

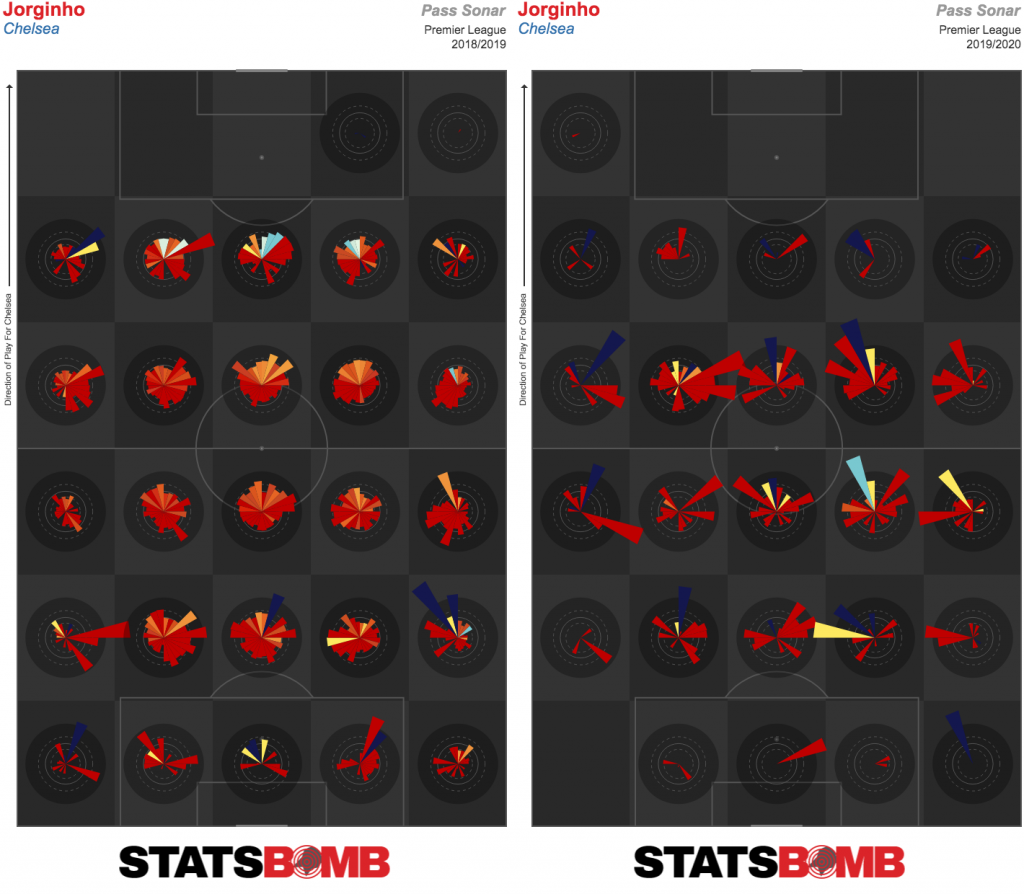

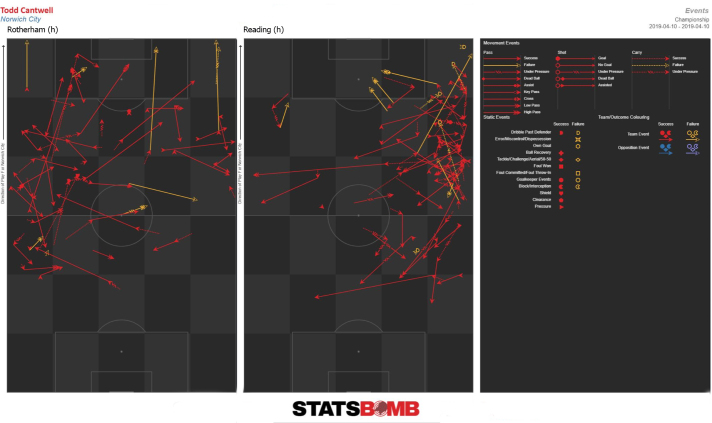

Is this genuinely evidence of what the team is doing or just one of those things that we shouldn’t expect to continue? That remains to be seen. This team does have something of the feel of Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool in 2016/17, who seemed to be wide open in a way that the xG models couldn’t quite grasp. The very high xG per shot conceded suggests there might be something happening here. But it is, of course, entirely possible that this is nothing and we will see a more normal finishing rate at both ends going forward. On the attacking side, all the talk has been about the kids. It’s a nice stat that all of Chelsea’s goals this season have been scored by academy graduates, even if the numbers paint this as somewhat unlikely (“the rest” have taken a combined xG of 3.92 without yet finding the back of the net). One could only describe Tammy Abraham’s current form as on fire, sitting as the joint top scorer in the Premier League with seven. The negative takeaway is that he’s overperforming xG by a fairly comical margin and yes, he will slow down a bit. He’s not going to score a goal every 49 minutes. But even so, he’s still getting a decent number of shots away in good positions. It doesn’t look like there have been any issues in transferring his Championship form to the top flight.  There are positives to take from his all round game as well. It’s fairly obvious from his height that he should be useful in the air and he’s done fine there, even if Lampard’s Chelsea aren’t really a “long ball” team. His link-up play to the eye has also looked much more positive than expected. It was always going to be a concern for Chelsea in possession that they lacked an obvious creator in the final third with Eden Hazard’s departure. Christian Pulisic, Mason Mount, Pedro and to a lesser degree Willian and Ross Barkley are all more adept at running into space than receiving the ball to feet and progressing the ball. If Abraham had merely operated as a poacher, this would have made things much worse, but he’s been willing to involve himself. Shots are taking up a smaller percentage of his total touches than last season. He’s taking more than twice as many touches inside the box as he did on loan at Villa, and his involvement outside the box has increased as well. Lampard is seemingly asking him to be a much more complete striker than in his past seasons, and he looks to be thriving at it. If this is Abraham’s trial to see if he can answer the long term centre forward issue at Chelsea, he’s done nothing to suggest he isn’t the solution.