Diego Maradona was one of the most visceral footballers in the history of the game, a player who constantly fed off his emotions and inspired in others a quasi-religious devotion.

So to some it may seem an act of sacrilege to drag Maradona into the world of expected goals, deep progressions and pressure actions, but that is exactly what we are doing for this second historical data release of our 10th anniversary celebrations.

Last week, we published free event data for 10 Johan Cruyff matches. Today, we are releasing 10 matches from the career of Diego Maradona, for Argentina, Barcelona, Boca Juniors and Napoli, spanning from 1979 through to his retirement in 1997.

Those who are anxious to dig straight into the data can find the access details at the bottom of the page, but for those who’d like to add a bit of context to their explorations, here is an analysis of the matches included.

The Young Maradona

Maradona made his debut for Argentinos Juniors in 1976, 10 days before his 16th birthday, and in the years that followed quickly established himself as one of the most exciting young players in the world.

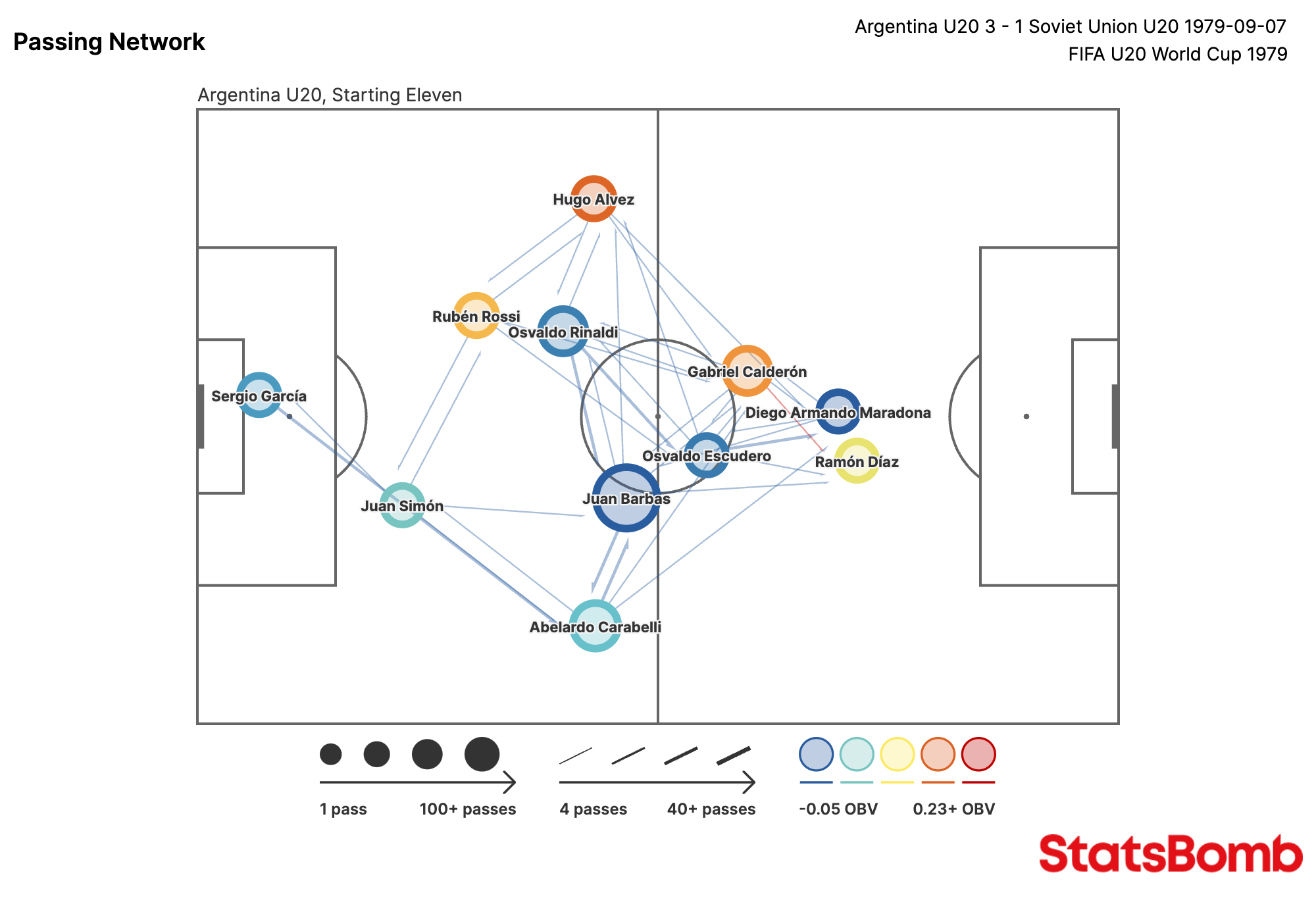

The first match in our dataset is the final of the 1979 FIFA World Youth Championship (now the Under-20 World Cup) between Argentina and the Soviet Union.

Argentina had won all five of their previous matches and were the favourites for the final, not least because of their potent strike partnership of Maradona and Ramón Díaz.

And a strike partnership it really was. Maradona was pushed right up alongside Díaz in a front two.

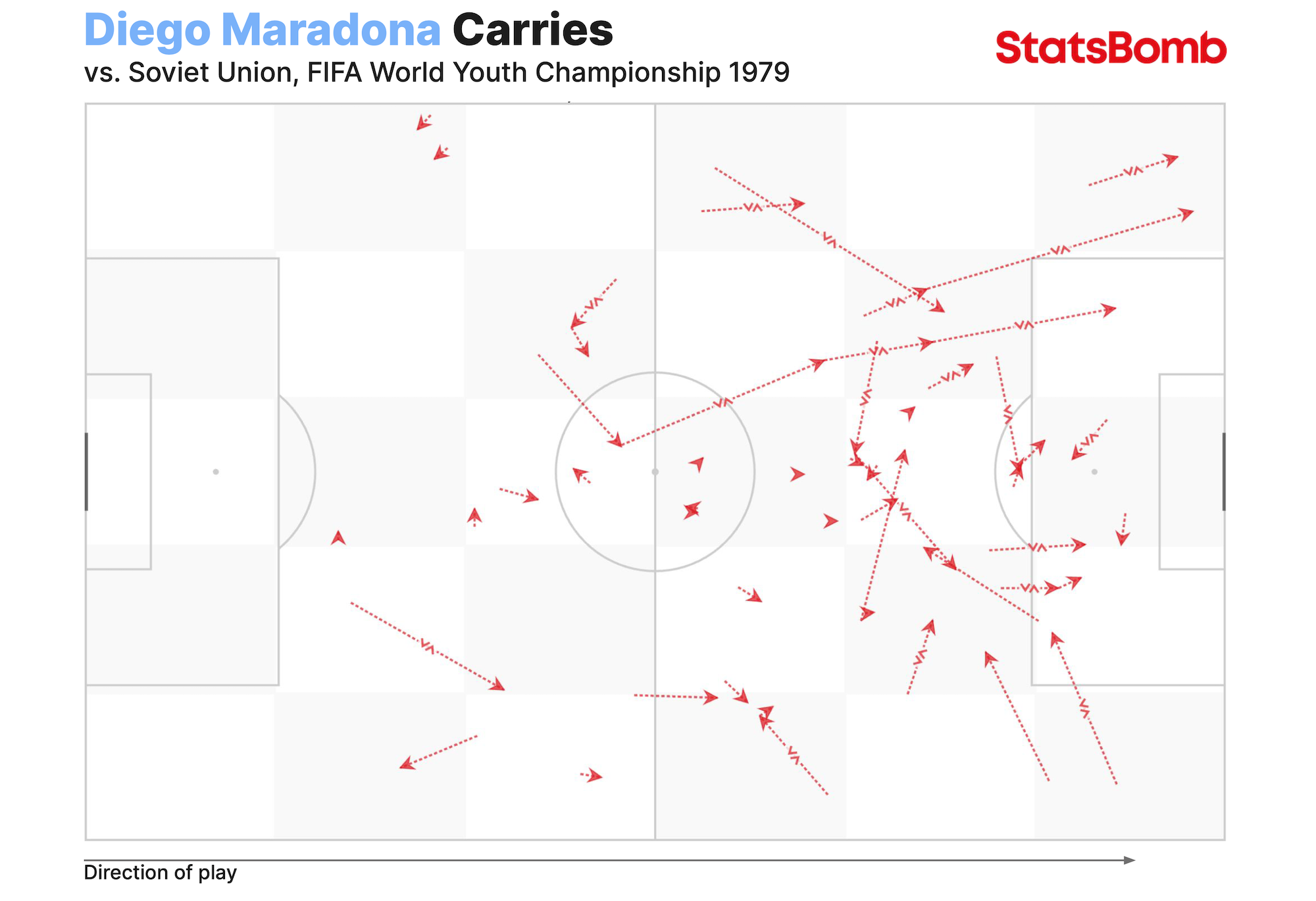

But even though he took more shots (6) than any of his teammates, it was his incisive carries that provided most value to the team.

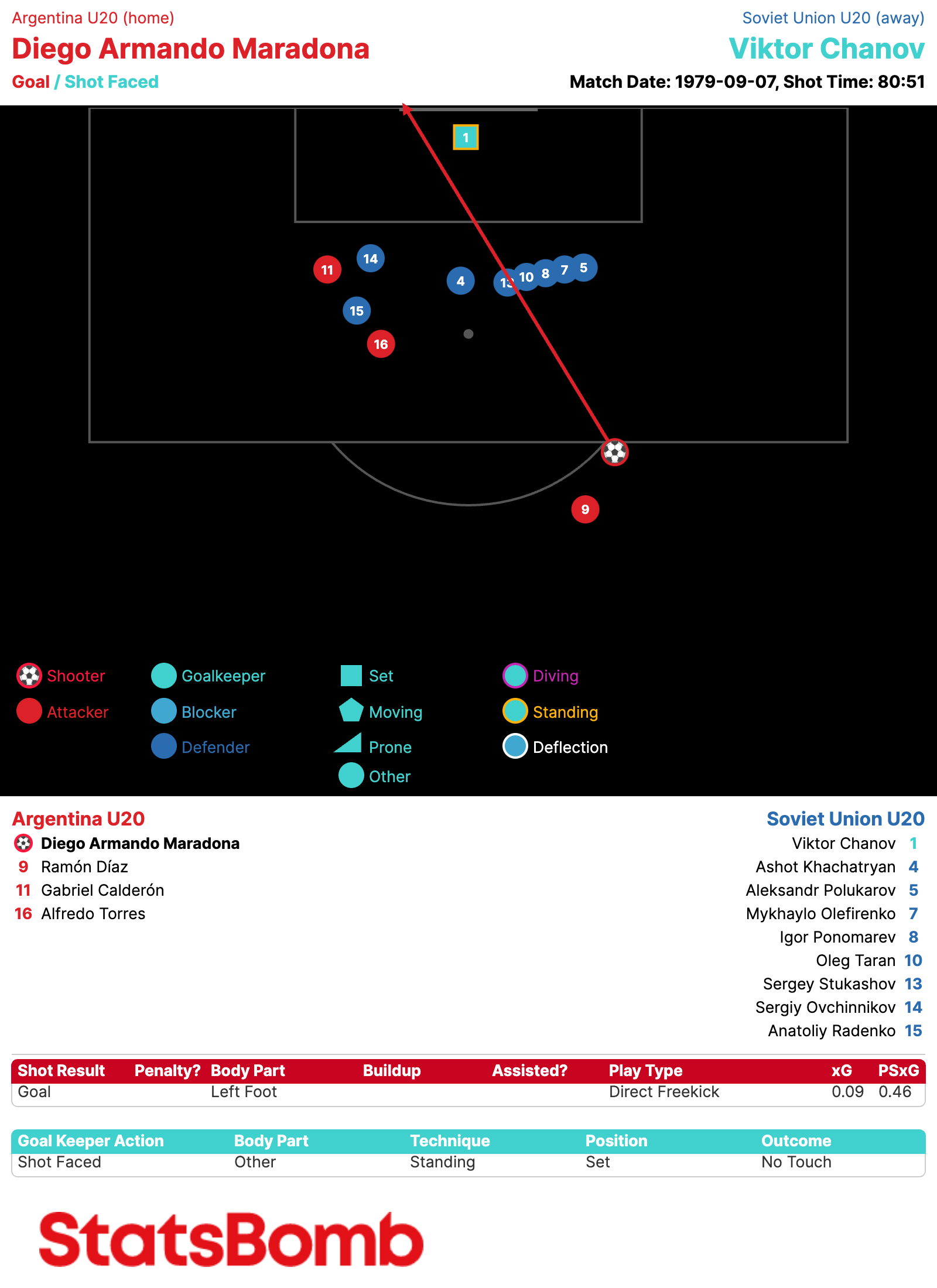

The Soviet Union upset the odds by taking the lead in the 52nd minute, but Argentina levelled things up from the penalty spot a quarter-hour later before goals from Díaz and Maradona fired them to Maradona’s first international trophy.

His was a powerful free-kick from the edge of the area:

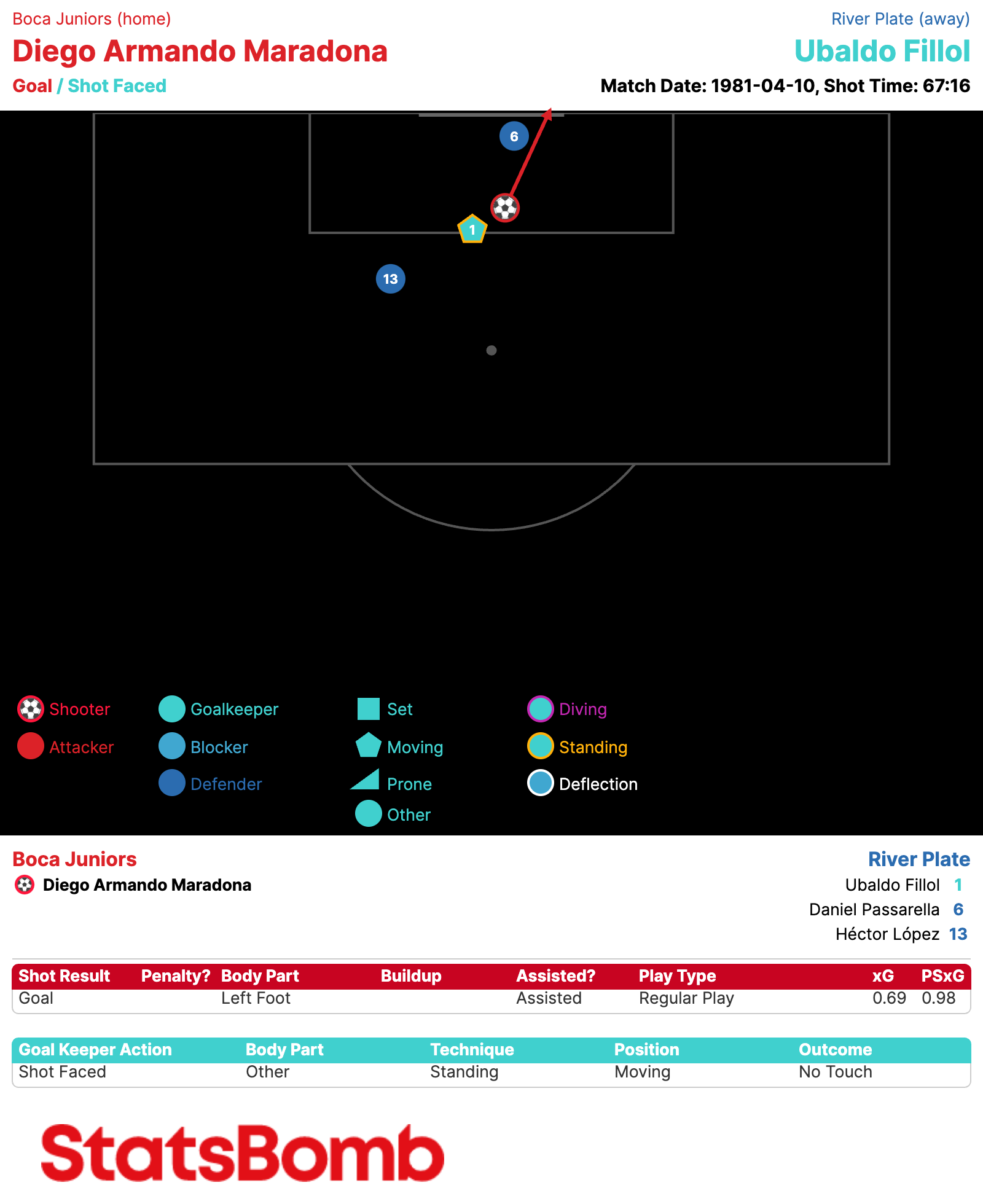

The second match in the dataset is the Torneo Metropolitano 1981 encounter between Boca Juniors and River Plate, the first superclásico of Maradona’s career. He spent a year and a half at Boca, winning that Metropolitano along the way, before leaving for Barcelona after the 1982 World Cup.

This Maradona is much closer in playing style to the version that would dominate the mid-eighties. He is involved all over the pitch, with a key role in both ball progression and the creation and taking of shots.

Maradona played a big part in the first goal, scored by Miguel Ángel Brindisi, and after Brindisi had doubled Boca’s lead, he appeared again with a dose of potrero cheek.

As Maradona brought down a high ball inside the area, the River goalkeeper Ubaldo Fillol saw an opportunity to advance and close the angle. Instead, Maradona used that momentum against him, nipping inside with a deft touch and then baiting the recovering defender Alberto Tarantini to make a move before rolling the ball calmly into the corner.

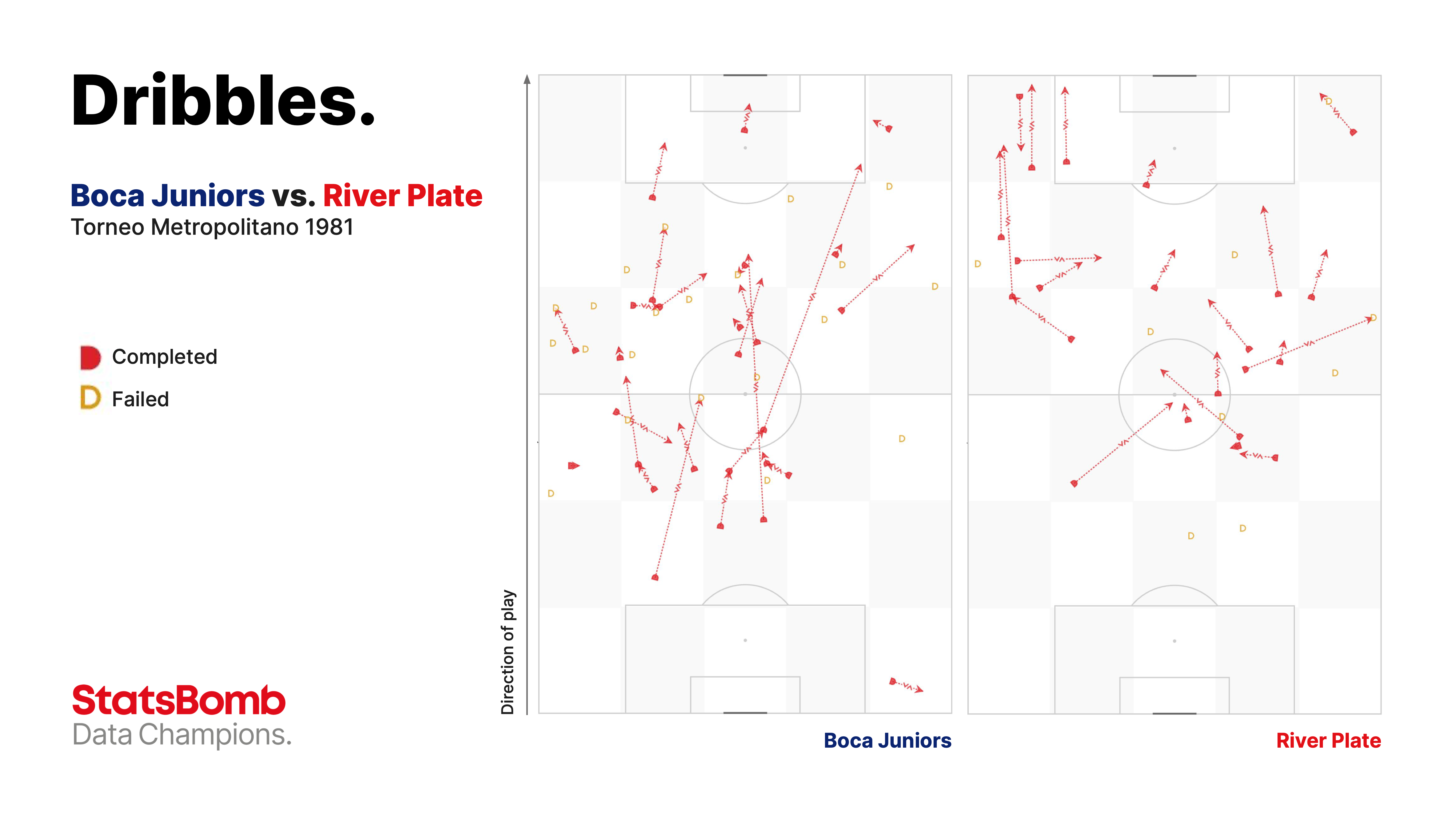

Fillol wasn’t the only River player to fall for a Maradona feint. Boca’s number 10 completed 11 dribbles over the course of the match. River couldn’t find a way of stopping him or, better said, a legal means of doing so. He was fouled nine times (including twice each by Tarantini and Daniel Passarella), more often than in any other match in this dataset.

Another thing that stands out from this encounter is just how many dribbles there were: 79 attempted (48 by Boca; 31 by River) and 49 completed (27 by Boca; 22 by River). For comparison purposes, no match in the current season of the Liga Profesional, Argentina’s top flight, has seen more than 64 attempted or 38 completed dribbles.

The last match in this dataset that takes place before Maradona’s coronation at the 1986 World Cup is the 1983 Copa del Rey final between Barcelona and Real Madrid.

In 1982, Barcelona paid a world record fee for Maradona but between various injuries and illnesses he was rarely able to show his best in the Catalan capital.

His compatriot César Luis Menotti is his coach in this match, as he was for the World Youth Championship final against the Soviet Union, and at the 1982 World Cup.

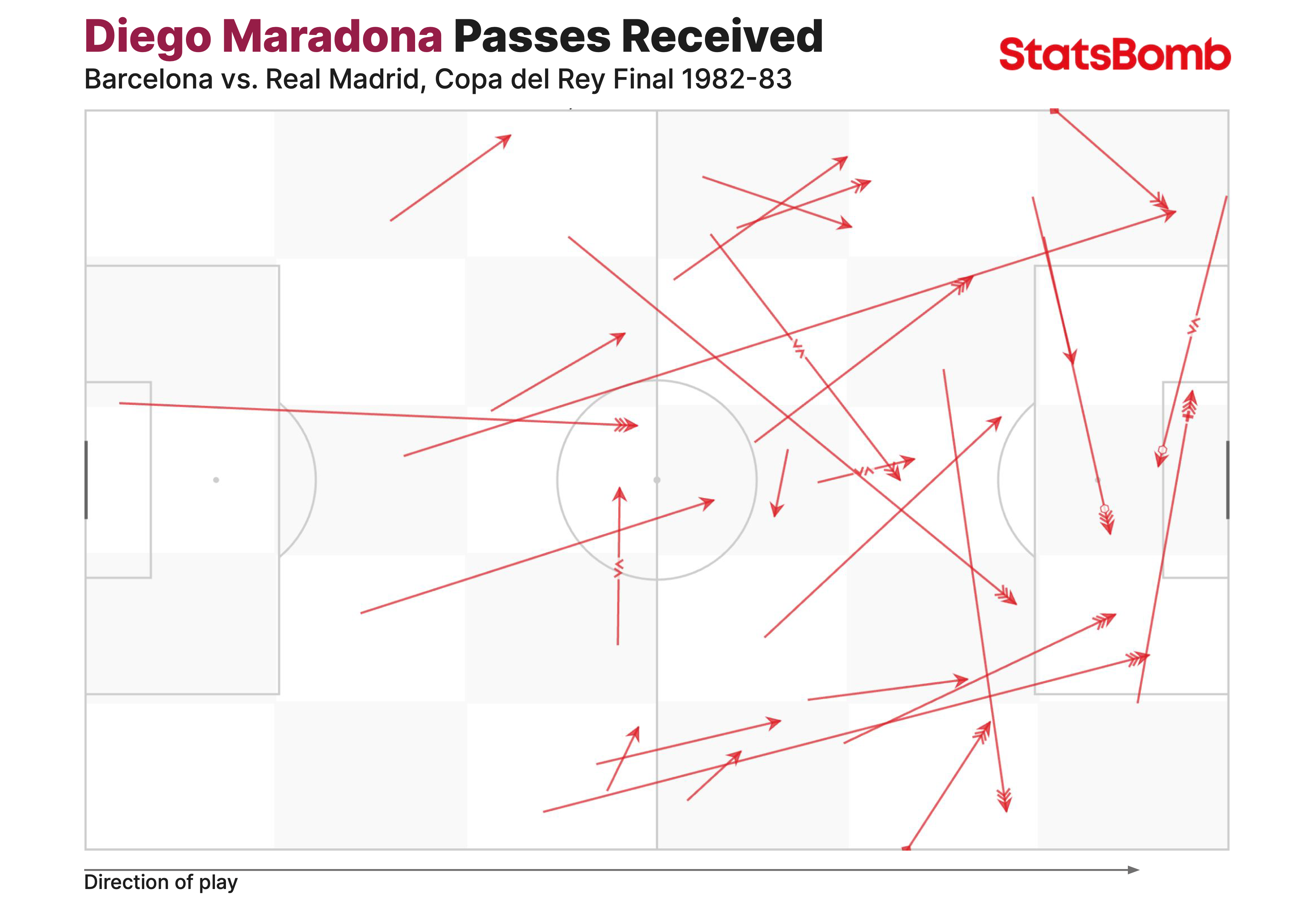

Menotti seemed to like positioning Maradona very high up the pitch, almost always as the furthest forward of the attackers, and that preference is clear here. Sixty nine percent of the passes Maradona received were in the final third, by far the highest percentage of any match in the dataset.

Despite the aggressive challenges and fouls he suffered at the hands of the Real Madrid players (José Antonio Camacho’s first-half scything slide is a particular standout), Maradona was very active in Barcelona’s play. He played an important part in the opening goal, receiving an excellent long pass from Bernd Schuster, Barcelona’s midfield orchestrator, turning inside a defender and laying the ball off for Victor Muñoz to finish crisply into the corner.

Santillana levelled the scores early into the second half after a glaring error from the Barcelona defender Gerardo Miranda, but undeterred Barça came again, finally scoring the cup-winning goal in injury time. It is a goal that has secured a place in Spanish footballing folklore. Julio Alberto skips past his marker and hangs up a cross to the far post that is met by the head of the flying Marcos Alonso (father of the current Barcelona and ex-Chelsea defender), who manages to direct it back across goal and in.

It was one of the two cups that Maradona won at Barcelona, the other being the short-lived Copa de la Liga, also in 1983 and also against Real Madrid.

The 1986 World Cup

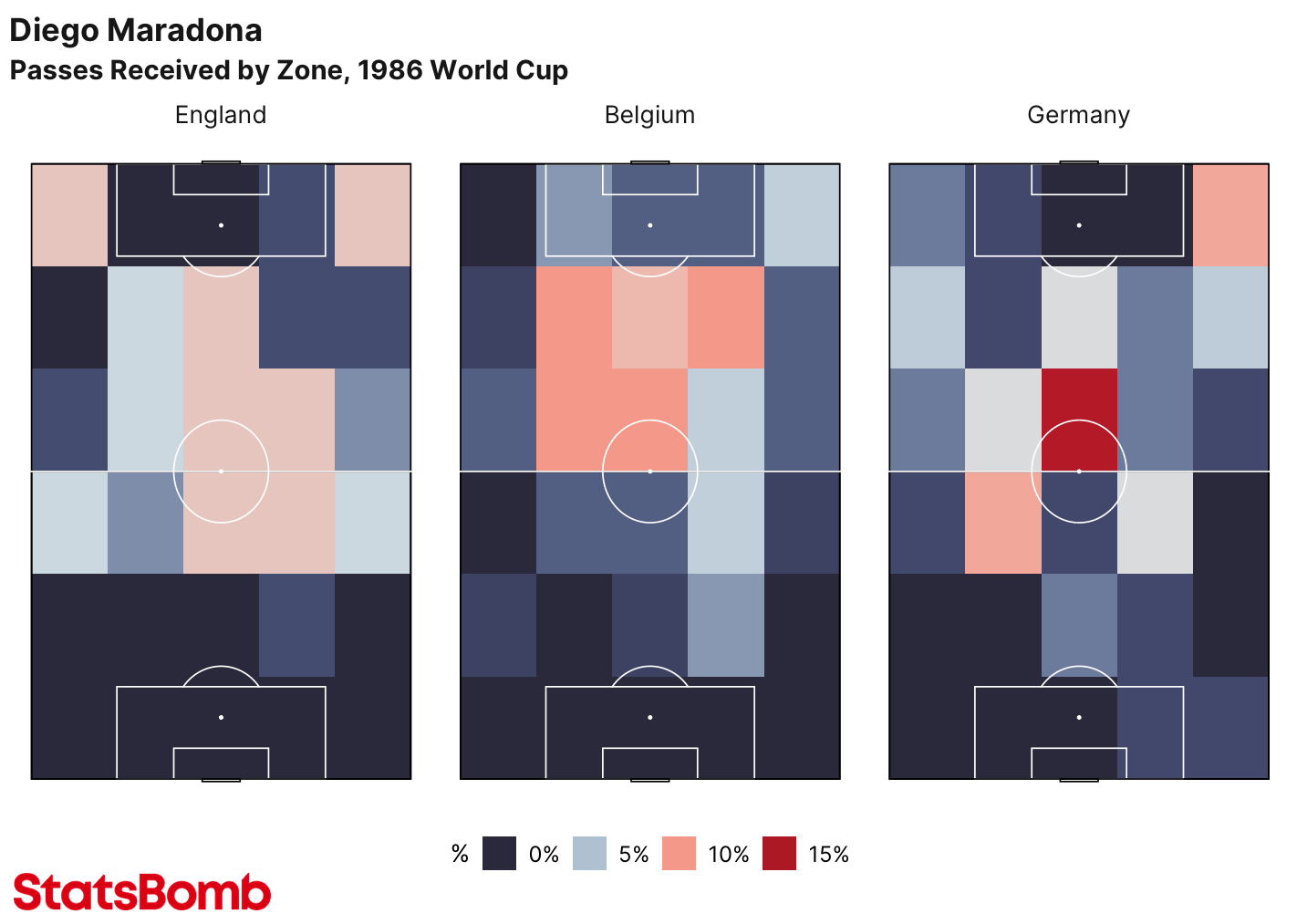

Diego Maradona was 25 years old at the 1986 World Cup and it is the tournament at which he established himself as the best player in the world. This dataset includes three matches from that World Cup: the quarter-final against England, the semi-final against Belgium and the final against Germany.

After progressing from the group stage and then seeing off Uruguay in the last 16, coach Carlos Bilardo elected to shift to a 3-5-1-1 formation for the final stages of the tournament, an approach he had trialled in earlier friendlies. It was a system designed to provide his star player with the framework he needed to carry Argentina to glory.

In the three matches included here, Maradona made a direct contribution (taking the shot/scoring the goal or providing the key pass or assist) to 71.42% of Argentina’s goals, 68.18% of their shots and 76.35% of their expected goals (xG).

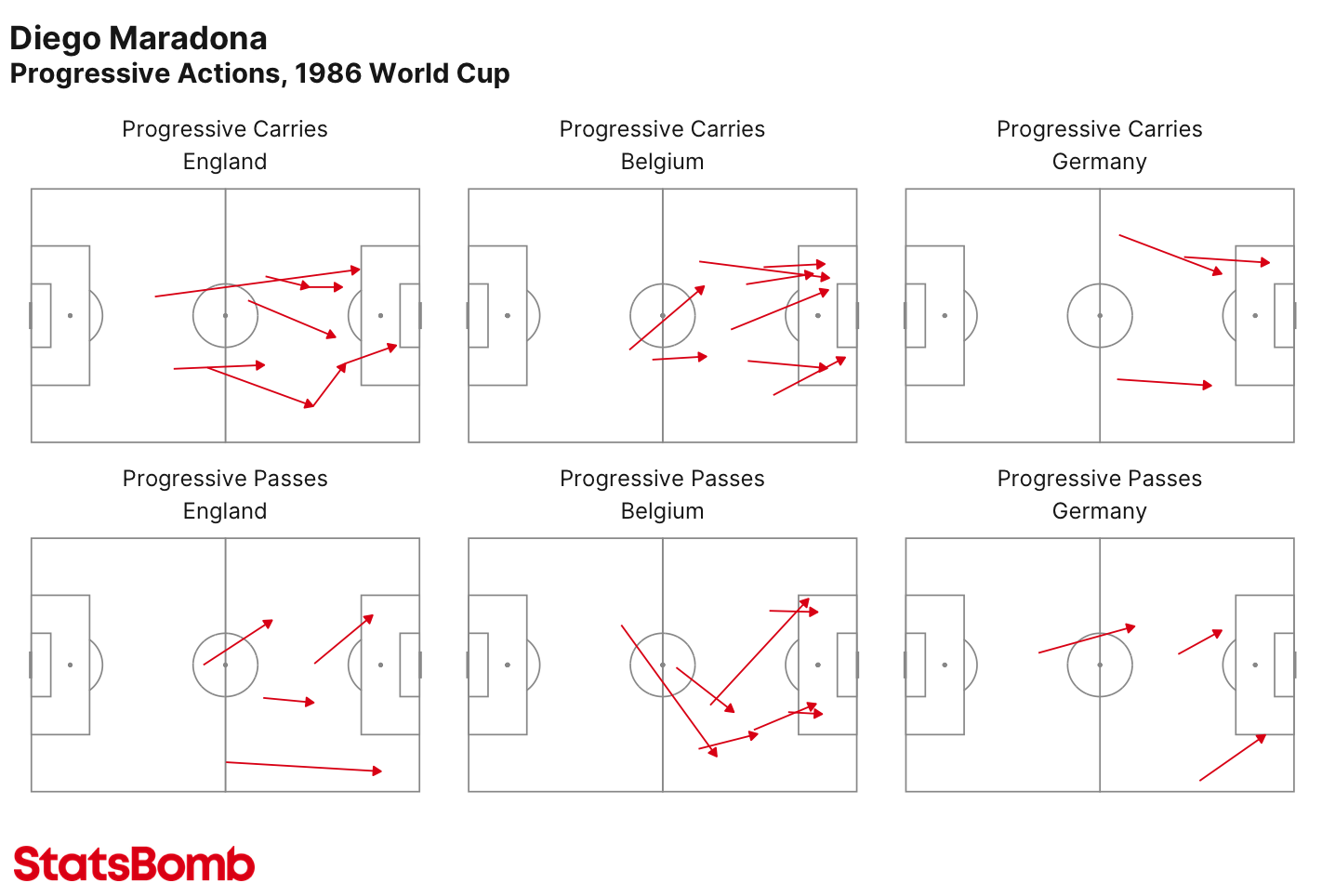

Not only that, but he was also the Argentina player who completed the most progressive actions (passes or carries that advance the ball at least 25% closer to the opposition goal): 33.

After his standout performances against England…

…and Belgium, it was little surprise that Germany came up with a specific plan to limit his influence. From the first minute of the final, Lothar Matthäus followed him like a hawk.

“We knew they were going to man-mark Diego, so he would have to move around a lot and try and appear by surprise,” Bilardo said years later, and there is some evidence that Maradona had to vary his positioning more against Germany than he had in the two previous matches. He moved out wide more often and saw less of the ball in the centre of the pitch.

Matthäus had already done an excellent marking job on Michel Platini in the semi-final against France, and Maradona would later say that he was the most effective marker he ever faced. He was certainly able to limit Maradona’s influence:

- England: 12 progressive actions, 2 goals, 7 shots and 6 key passes

- Belgium: 15 progressive actions, 2 goals, 6 shots and 6 key passes

- Germany: 6 progressive actions, 0 goals, 1 assist, 4 shots and 1 key pass

But even though Maradona was less involved in their play, Argentina were still able to establish a two-goal lead before the hour mark. José Luis Brown opened the scoring with a towering header, pushing up off Maradona’s back, from a Jorge Burruchaga free-kick and then, just after the interval, Maradona flicked a nice pass around the corner to Héctor Enrique (second to Maradona in terms of progressive actions over these three matches) to set the attack in motion that led to the second, scored by Jorge Valdano.

It seemed like the trophy was won but Germany weren’t ready to give up just yet. They struck back with two goals in eight minutes, both from flicked-on corners, to level things up with less than 10 minutes to play.

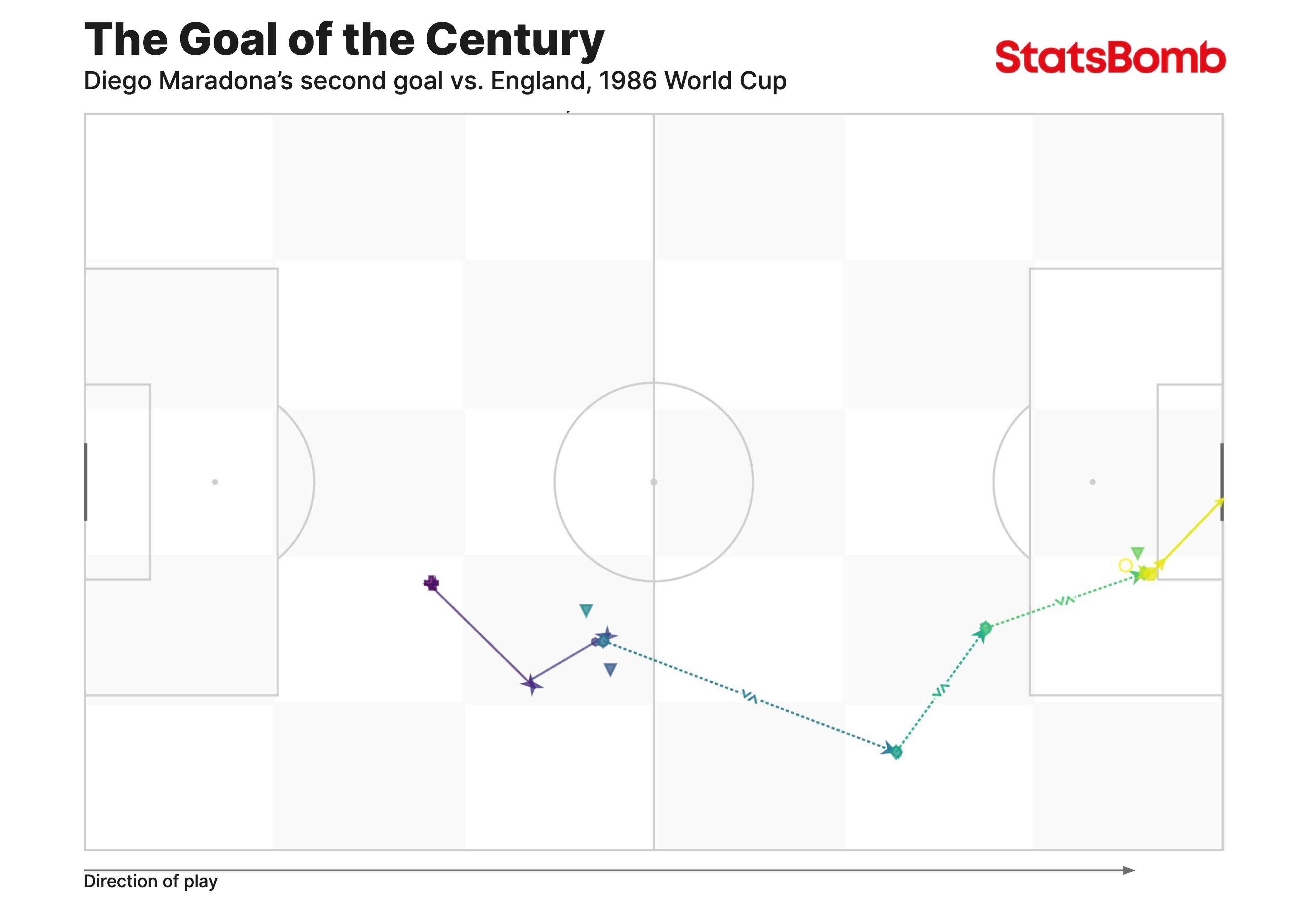

The tide of the match appeared to have shifted but then, just when it mattered most, Maradona appeared in the centre of the pitch to slip a neat pass through to the run of Burruchaga, who raced into the area and finished low to win Argentina the famous trophy.

Maradona was named player of the tournament, with nearly four times the number of votes of the second-placed player, Germany goalkeeper Toni Schumacher.

The Glory Years in Naples

Maradona signed for Napoli in 1984 after his frustrating spell at Barcelona and in the seven years that followed would become an idol of the Neapolitan people by taking Napoli to the first (and until last season, only) two league titles in their history, in addition to triumphs in the Coppa Italia and the UEFA Cup.

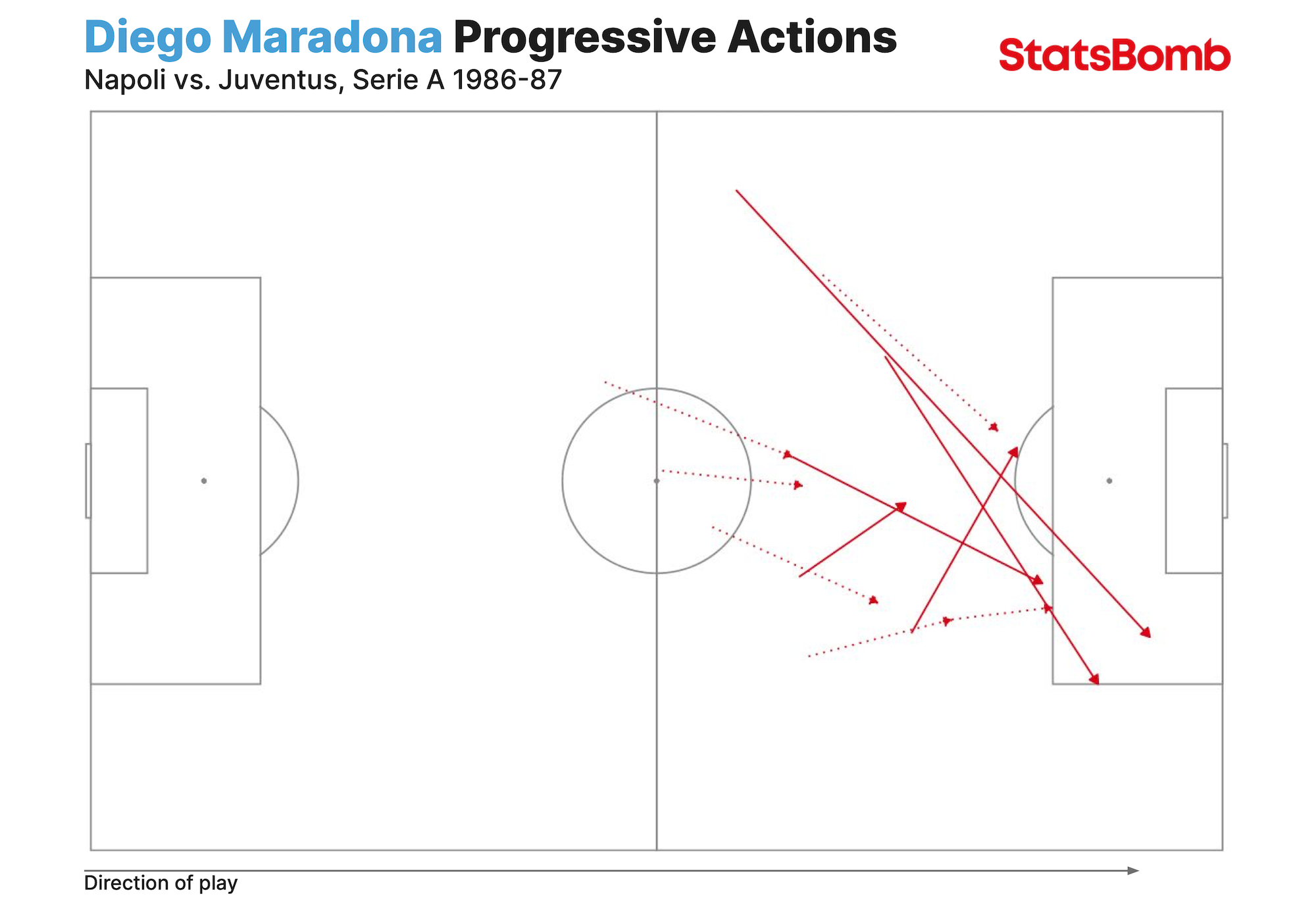

The first of the two matches from this era included in the dataset is the Serie A encounter between Juventus and Napoli in November 1986. Juventus were the reigning champions; Napoli, the new pretenders to their crown.

Maradona didn’t score or assist in this match but he is clearly the same Maradona that we saw at the World Cup. He led the team in progressive actions (11), while the sum of his four shots and four key passes made him the primary direct contributor to shots.

Napoli won 3-1 in a season in which they would claim their first-ever Serie A title.

Three years later, the club reached the UEFA Cup final, defeating strong teams like Juventus and Bayern Munich along the way. Stuttgart were their opponents in the final, and this dataset includes the first leg in the Stadio San Paolo.

The Maradona in this match is different to the mid-eighties version. He is more static, carrying out most of his work in the final third and handing over responsibility for ball progression to the passes of Alessandro Renica and Fernando De Napoli and the ball carrying of Alemão and Careca.

In open play, he only took one shot and set up one chance, but even so he was the most decisive player in terms of the scoreboard. He won and converted the penalty with which Napoli equalised in the 68th minute and then, in the closing stages, produced a lovely touch inside the area to skip past a defender and set up Careca to score the goal that gave Napoli a narrow lead ahead of the return leg.

Two weeks later, Napoli and Maradona lifted their first continental trophy after a 3-3 draw in Stuttgart.

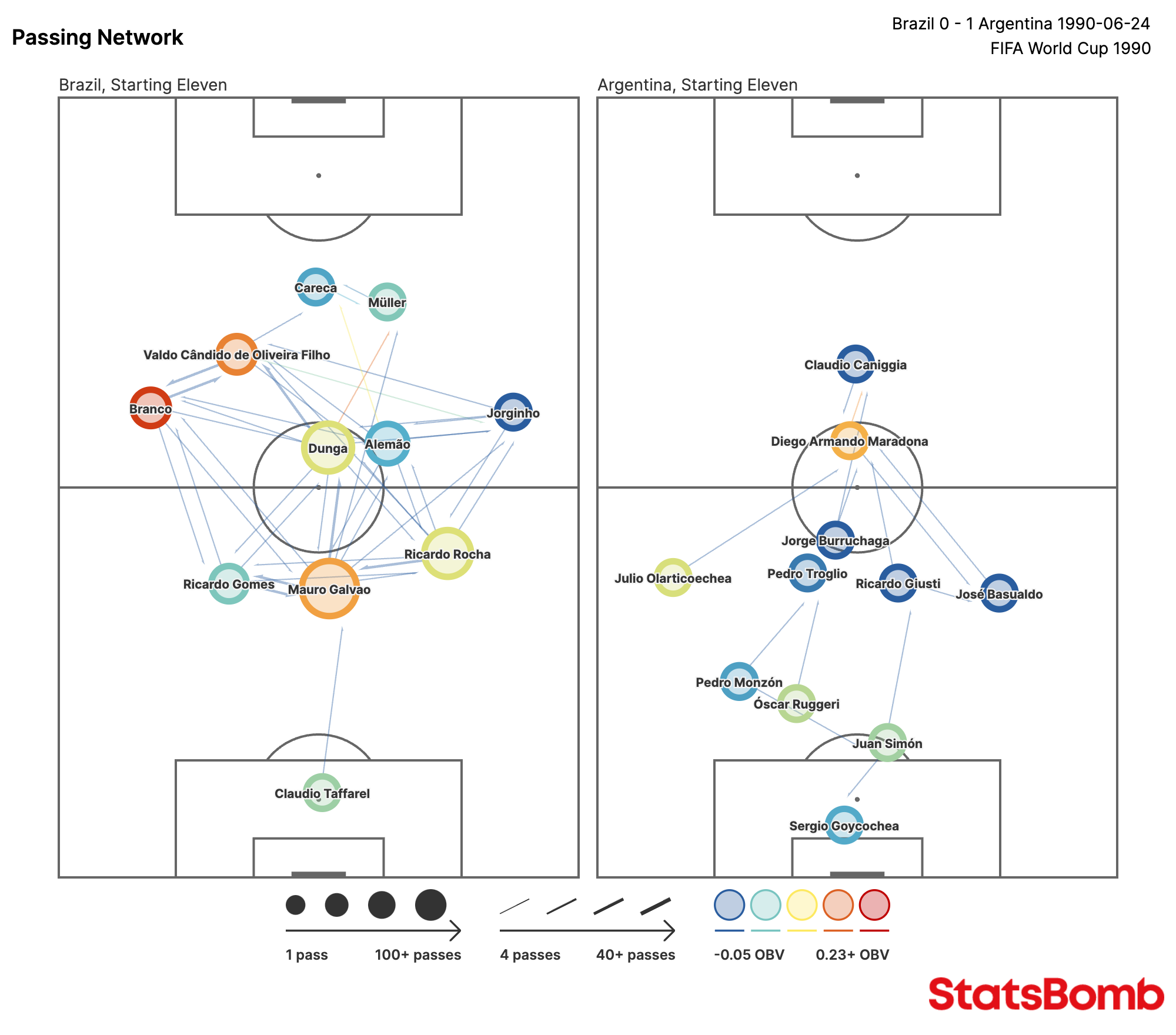

1990 World Cup: Argentina vs. Brazil

Despite being warmly remembered in England for the country’s strong run to the final four, Gazza’s tears and the emotional strains of Nessun Dorma, the 1990 World Cup was generally thought to be a thoroughly ugly spectacle, one that would fairly swiftly lead to various changes in the rulebook in a bid to improve the attractiveness of the game.

Argentina returned with the same coach and system as in 1986. They again reached the final, this time losing to Germany, but never played with the same clarity they had achieved in Mexico four years earlier.

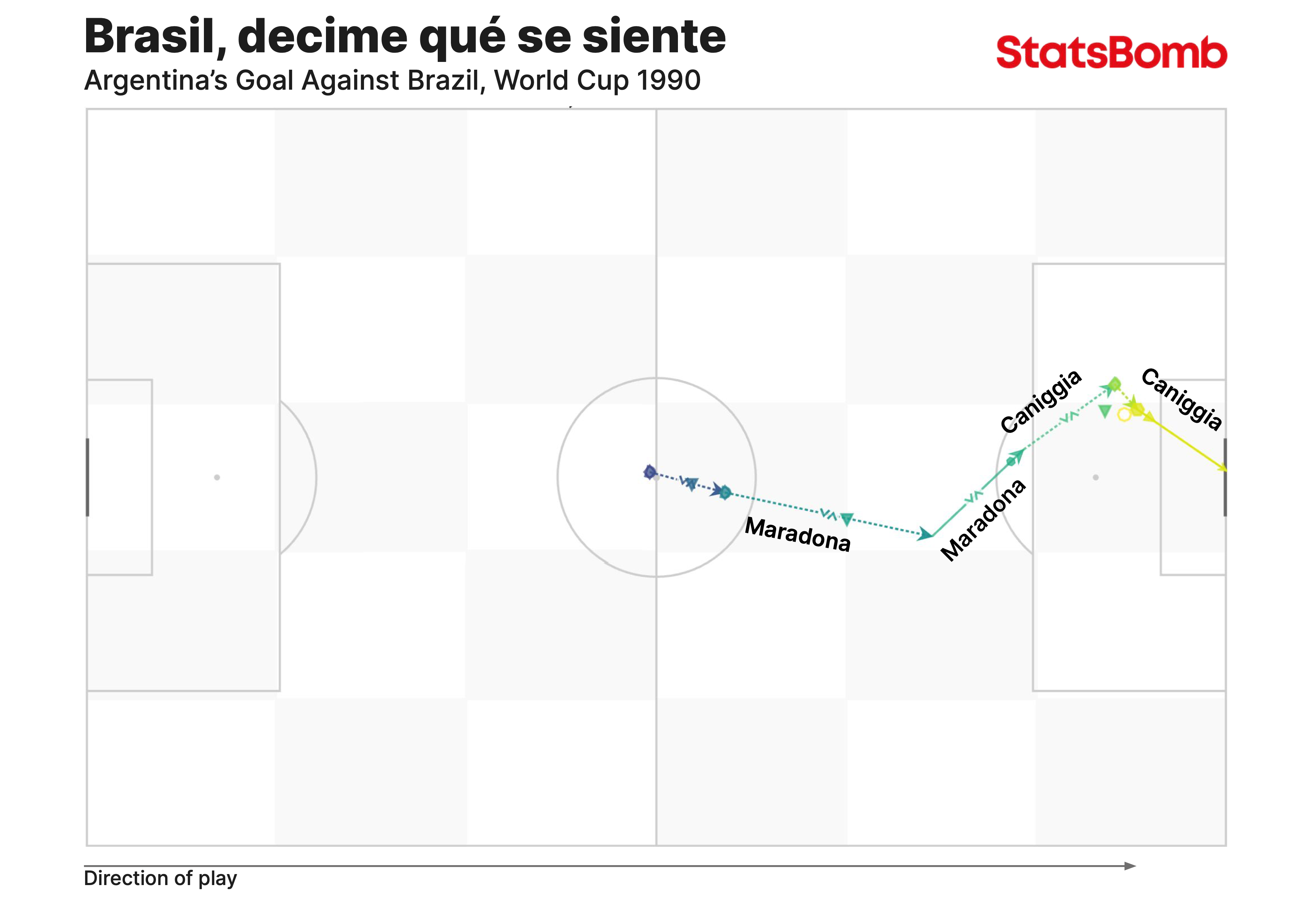

Maradona wasn’t quite the same player either but he still retained the ability to decide matches by himself, as he proved in the round of 16 against Brazil, Argentina’s eternal rival.

It was a match that the Brazilians dominated, particularly in the first half (nine shots to two; 1.02 xG to 0.09) against an Argentinian side short on ideas. There was a clear pattern to their play: when they weren’t giving the ball to Brazil, they gave it to Maradona.

In the end that "tactic" proved a good one:

So good it inspired a song.

The Final Match: River Plate vs. Boca Juniors, 25/10/1997

Between the match against Brazil in 1990 and this one, the last of his career, seven years later, Maradona had (deep breath): twice been banned for drug-taking (once recreational; once performance-enhancing); spent a season at Sevilla; played a handful of matches for Newell’s Old Boys and a pair of World Cup matches for Argentina; coached, without much success, both Textil Mandiyú and Racing Club; and finally, returned to Boca Juniors.

A superclásico represented the perfect stage for his sendoff.

And to complete the circle of this dataset, before the match he scuttled over to the River Plate bench to shake hands with their coach: Ramón Díaz.

Maradona was 37 years old at this point and not much for running. He spent most of the 45 minutes he played stationed around the centre circle. Just 17% of the passes he received were inside the final third, 10 percentage points below any other match in this dataset.

He produced a few nice touches, a couple of well-executed passes and one weak right-footed shot on goal (the only right-footed shot in this dataset) before being substituted at the interval.

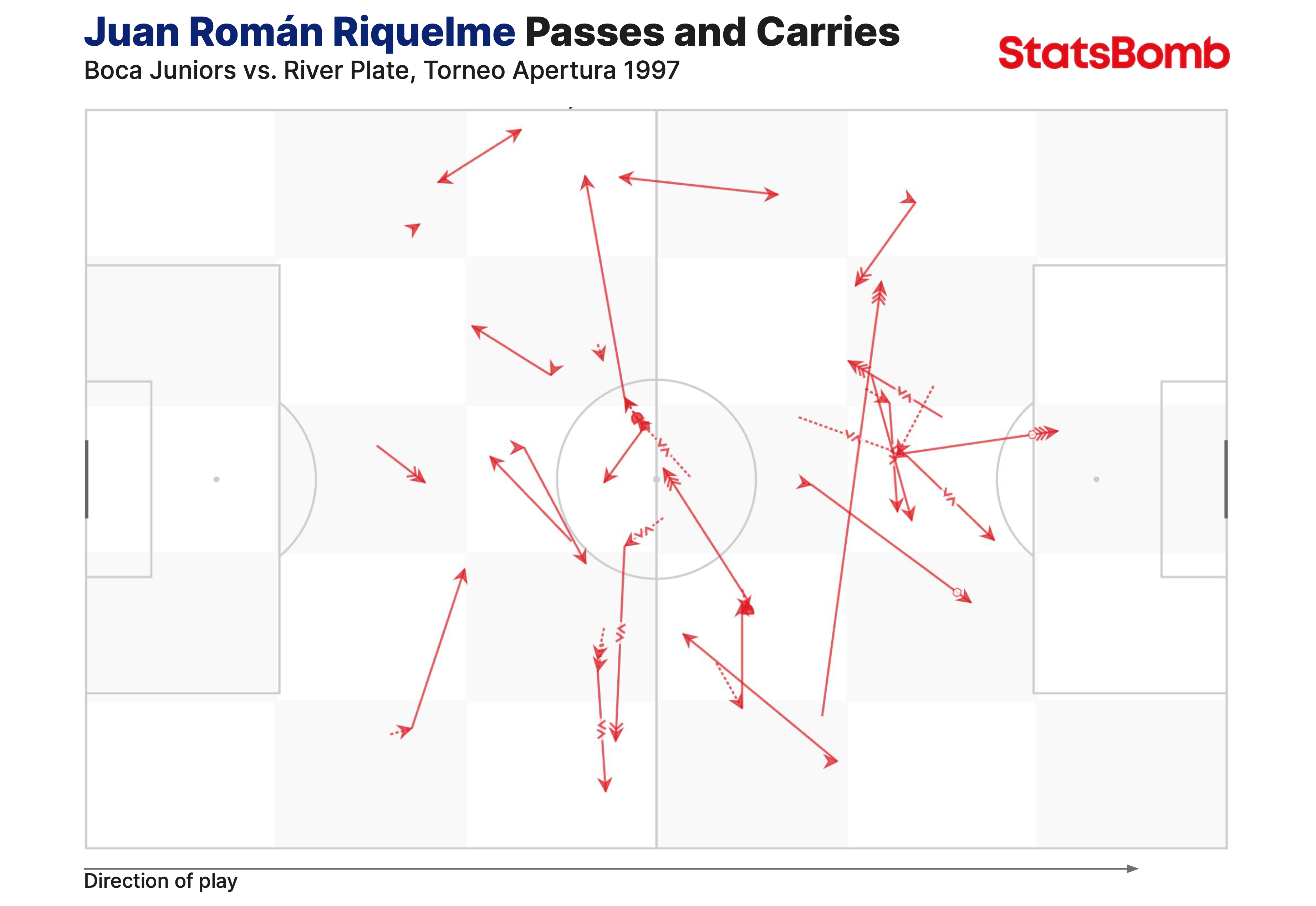

He was replaced, at his express wish, by a 19-year-old footballer that many viewed as his potential successor, a player who in time would become the most successful number 10 in Boca’s history: one Juan Román Riquelme.

And so you can all enjoy 45 minutes of free data of one of the most unique footballers of the last 30 years.

Boca won an even match 2-1 with goals from Julio César Toresani and Martín Palermo (already sporting his famous bleached blonde hair), but Maradona’s summary is probably more descriptive: “Boca played like Boca and River were River,” he said. “They played well in the first half but then they got caught with their pants down.”

A question: How left-footed was Diego Maradona?

Across the 10 matches, Maradona made 83% of his passes with his left foot and took 97% of his foot shots with it.

For comparison purposes, over the last five seasons, Lionel Messi has made between 89% and 92% of his passes with his left foot and taken between 86% and 93% of his foot shots with it.

To summarise: Maradona was less reliant on his left foot than Messi when passing but more reliant on his left foot when shooting.

Accessing the Diego Maradona Data

As the Maradona dataset is drawn from various competitions and seasons, the easiest way to pull the data is via the match IDs.

Python

ids = [3889115, 3889082, 3888787, 3750191, 3889148, 3889149, 3793185, 3888721, 3887188, 3889182]

events = []

for n in ids:

match_events = sb.events(match_id = n)

events.append(match_events)

events=pd.concat(events)

If you get an IndentationError when running the code, use the tab key to indent the two lines of code that start with match_events and events.append. When you rerun the code, it should work.

R

Comps <- FreeCompetitions()

maradona_matches <-FreeMatches(Comps) %>%

filter(match_id %in% c ('3889115', '3889082', '3888787', '3750191', '3889148', '3889149', '3793185', '3888721', '3887188', '3889182'))

events <- free_allevents(MatchesDF = maradona_matches, Parallel = T)

events = allclean(events)

events<-merge(events, maradona_matches, by="match_id")

events = get.opposingteam(events)

As always, if you use our data in any work you share publicly, please credit StatsBomb as the source (our logos can be found in our Media Pack).

*Please note that there were missing minutes from the video for a small selection matches. Subsequently, there are some games where the halves are slightly shorter than 45 minutes.

We hope you enjoy the data and we’ll be back soon with the third and final icon.