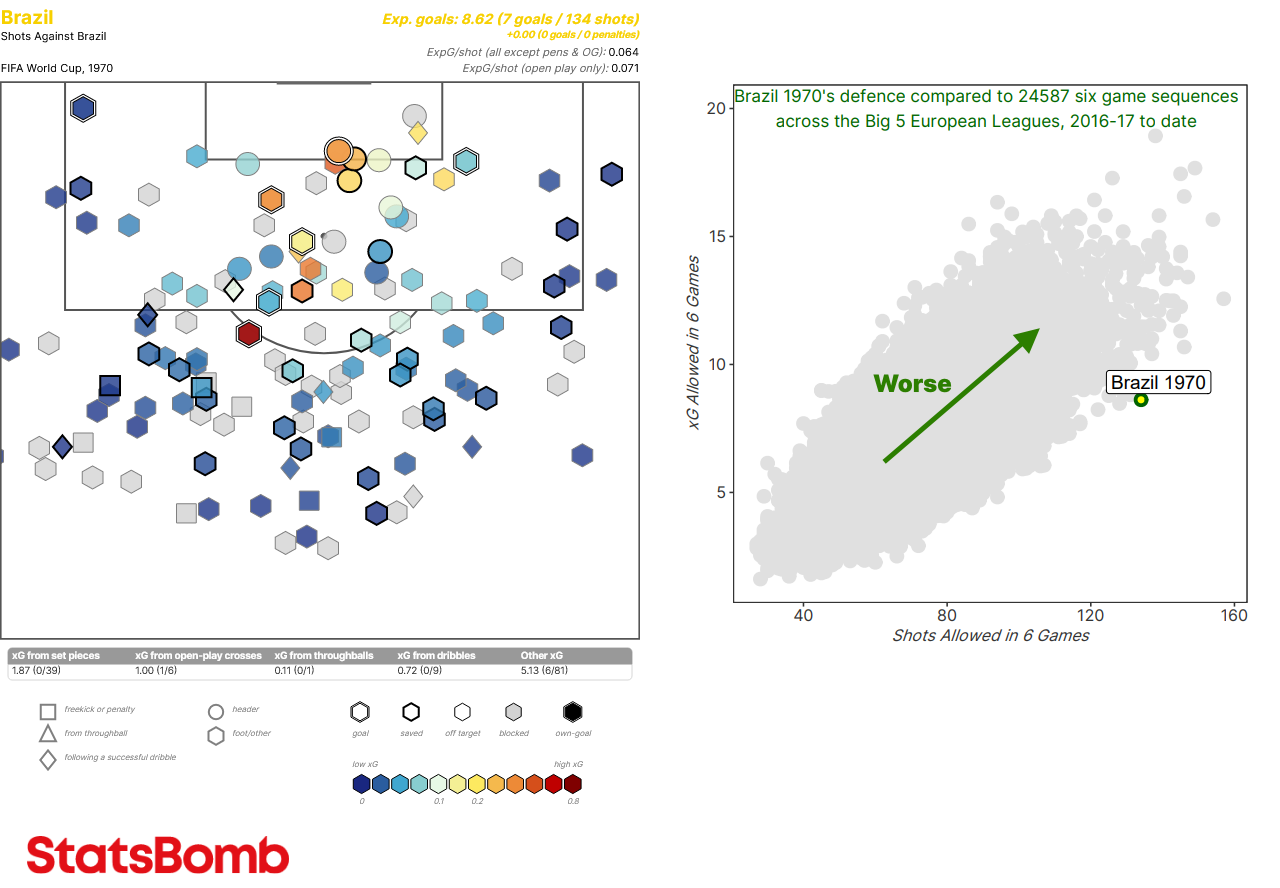

A couple of weeks ago, we announced the StatsBomb Icons series - our look back at some of the best players to have ever played the game through the lens of our data, with the data also released for free to the public to perform their own analysis. We started with Johan Cruyff, followed by Diego Maradona. Today, we analyse Pelé.

It is hard to write about Pelé in a way that adds something new or does justice to his legend, but adding data elements to historical games allows us to further quantify the his influence in some of his most feted games over and above the basic but eternal footballing currency of goals and assists. Really though, it's just good fun.

This is the final release of the three-part Icons series released this summer, with complete StatsBomb event data for each Icon made available for public analysis on our GitHub page:

1. Johan Cruyff

3. Pelé

The games we have collected offer not only a glimpse of Pelé but also the assorted cast that surrounded him; from Garrincha, Vavá and Didi in 1958 and 1962, to Jairzinho, Rivelino and Tostao in 1970. There's also his final official competitive game for the New York Cosmos where Franz Beckenbauer, Giorgio Chinaglia and his former Brazilian team-mate Carlos Alberto joined him to win the 1977 Soccer Bowl.

We'll explain how to access the data at the bottom of this article, but first, we've analysed the data ourselves to see what we can learn about one of the greatest footballers to have ever played the game.

Analysing Pelé

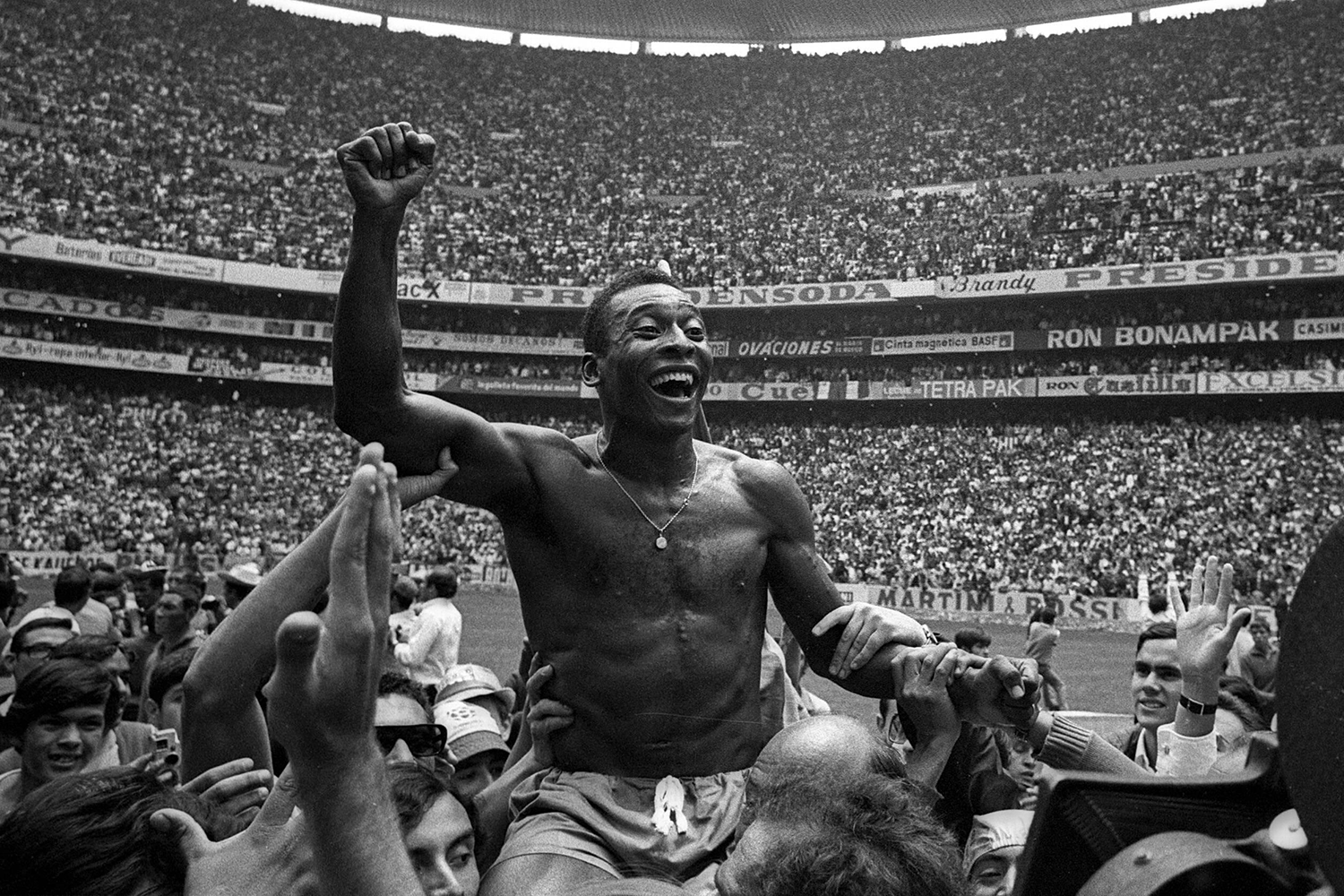

The 1958 World Cup

Pelé's career existed before the 1958 World Cup and after the 1970 version, but those two tournaments cemented his legacy more than anything else. In 1958, a 17 year old took the tournament by storm in a manner that no young player has since replicated. With six goals - all in the knock out stages of the tournament- Pelé was an instant superstar, and already a World Champion. Our dataset provides the last two games, the semi-final against France and the final against Sweden, in which Brazil won each game 5-2 with Pelé scoring half of Brazil's goals.

Here's Pelé's shot map for those two games; remember this is the work of a 17 year old in two of the most important matches conceivable:

The 1962 World Cup

Pelé participated in four World Cups, but injuries intervened in the second (1962, Brazil won) and third (1966, Brazil did not win). He played only one game in 1962 but scored a memorable solo goal against Mexico single-handedly driving from an unthreatening position on the right flank, beating a slew of players with speed, agility and power before dispatching a low left footed shot into the far corner. At 21, Pelé was widely regarded as the best player in the world, and within this one game took 12 shots (with an expected goal value of 1.01) and created a further eight chances for teammates. Football was different back then, with higher shot volumes and less interest in shot location than the modern game, but even so, such extensive volume of contribution is notable. This glimpse also implies that a fit and firing Pelé missing out on a full World Cup at both aged 21 and 25 was something of a raw deal for himself, Brazil and fans alike. Fortunately, he returned for one more shot at the Jules Rimet Trophy in 1970 with success offering the chance of a unique hat-trick of titles.

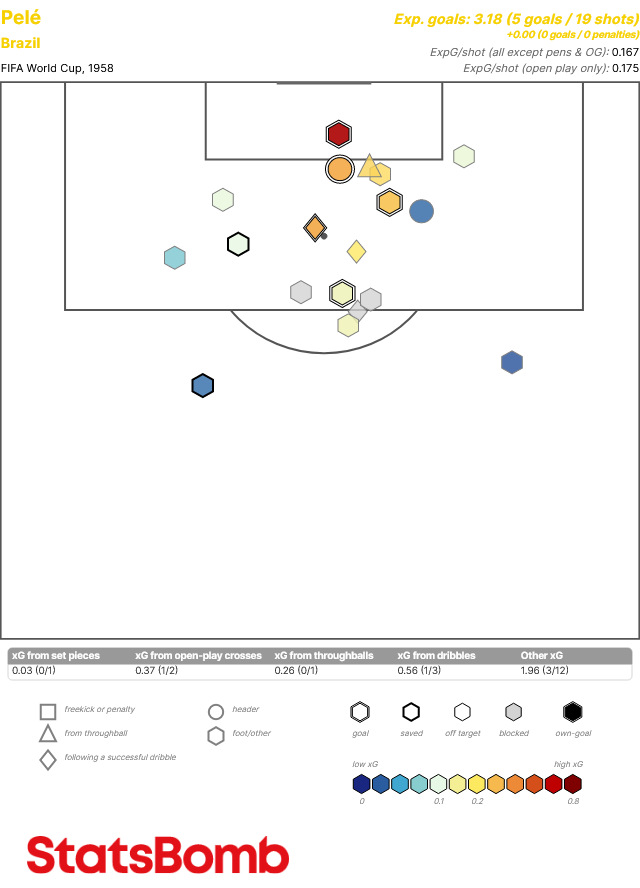

The 1970 World Cup

Relentless power shooting and wildly high shot volumes at both ends are not the first things that come to mind when considering Brazil's 1970 World Cup winning side, but an initial look at the data followed by a trip to the video archives then a return to the data certainly backs up that perception. Brazil won this World Cup at a canter scoring three or four goals in every game aside from a 1-0 victory against then reigning champions, England. But this team needed to have this attacking strength, as at the other end they routinely gave up a phenomenal volume of shots. Let's look at the attack first.

In their six games Brazil took, respectively, 29-20-22-30-23-27 shots, an average of 25 per game, with a mid level xG per shot of around 0.105. They scored 19 goals ahead of an xG of around 15, but when factored against the modern game, that shot volume is super high - across the last six seasons in the big five European leagues only one team, Bayern Munich in late August 2022 has matched that total of 151 shots in a six game streak and no team has exceeded it, see here:

Very much a two tier shooting strategy here: ding it from range or/ find forwards deep in the box and close to goal. The almost complete absence shots from mid range is notable. Brazil were not shy to shoot on sight and as stated, so much of this was hard hit, power shooting. In scoring three times from the edge of the box and beyond and a consistent danger from free kicks, Rivelino was the primary danger from distance:

That's six shots per game from an attacking midfielder, something Bruno Fernandes can only dream his manager would encourage him to attempt, and enough to lead the team and Rivelino's sharp finishing enabled him to double his expected goals. Pelé himself was attempting over five shots per game, Tostao more than three. The team was clearly orientated into two parts: the attack, and those that were not the attack: Pelé, Tostao, Rivelino and Jairzinho were responsible for 89% of the team's expected goals (13.3/14.9) and all the team's goals until Clodoaldo scored in the semi-final against Uruguay and Gerson and Carlos Alberto notched in the final.

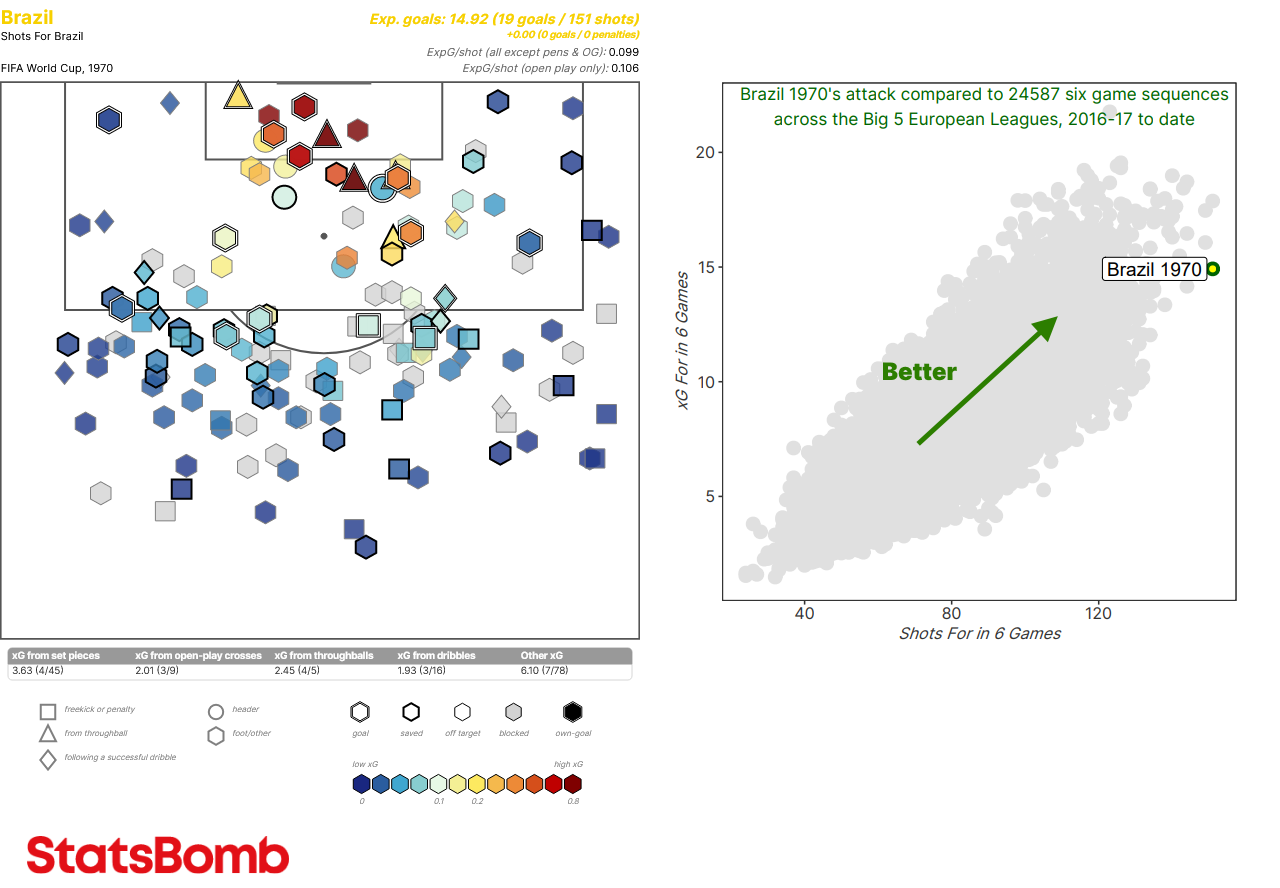

This rampant shooting was counteracted by the same strategy deployed by every opponent, but with less success. Brazil were able to limit the overall shot quality of their opponents but not the volume of shots their goalkeeper Felix was facing. Indeed, across the six games they allowed 32-21-18-19-18-26 shots for an average of 22.3 per game:

As the shot map shows, despite the volume, the quality was not high. Opponents scarcely got in behind Brazil, but did pepper the goal from range. The right hand chart shows how scarce such shot concession is in the modern game. Across close to 25,000 six game sequences between 2016-17 and today in the big five leagues, by way of comparison, Brazil's defence allowed shots at a rate that ranked 44th most. Strategies around shot suppression were comparatively alien 50 years ago.

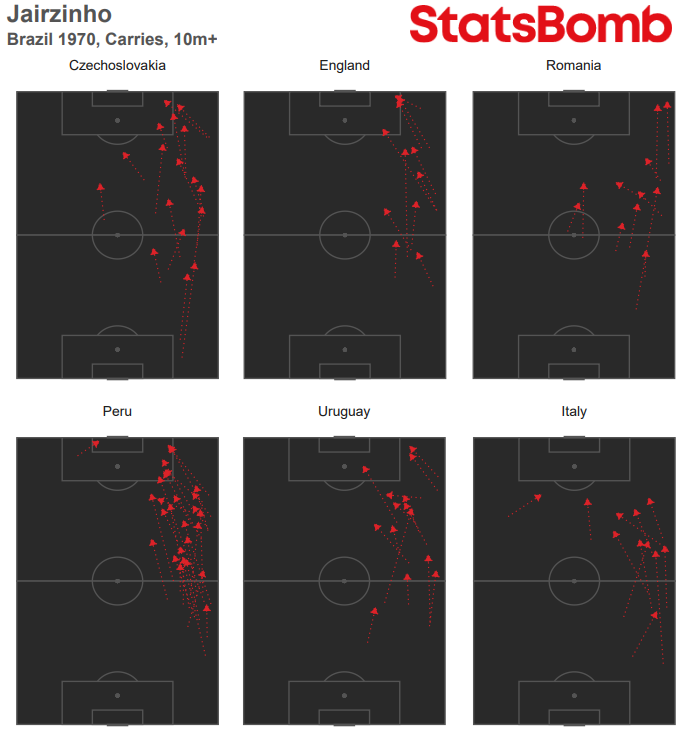

Understanding Pelé's role in Brazil's attack is most usefully rendered if we understand the specific elements that Jairzinho, Rivelino and Tostao offered. As mentioned, the vast majority of the team's attacking output came via these four players, and so did the makings, with a generous nod to Gérson's ability to create chances in the games he featured in. Jairzinho was a ball carrier of great speed and skill; he completed over 70% of more than 10 attempts per game to beat an opponent via dribble, and carried the ball huge distances down the right flank in every game, as we can see here:

He scored seven times in this World Cup but all but two were within hailing distance of the six yard box, so elite ball carrying, deep runs into the box and finishing pretty much covers the core of his input. Rivelino added to his shooting threat from long range with decent ball carrying, albeit not quite at Jairzinho's level (two thirds of his 6.5 dribbles attempted per game were completed) and also a range of passing. In completing more than six designated "long balls" per game, he led the team. Tostao operated high up the pitch alongside Pelé in one of the twin striker roles of Brazil's nominal 4-2-4 and shot frequently (3.6 per 90, 0.58 per 90) and linked play among his cohorts, he just did most things less frequently and less well than Pelé.

Pelé shot over five times per game in this tournament and scored four times. This came out at a shade under his team-leading 4.33 xG, but a look at some of the chances he missed sheds light on the range in his shooting:

Let's run through the numbered shots:

- (v Czechoslovakia) Rivelino hammers a low ball across the box, a slight deflection takes the ball straight to Pelé, who with the goal completely open has no time to adjust and fires over - xG: 0.86, it's an open goal but the pace has impacted the probability

- (v Italy) Jairzinho feeds Carlos Alberto who is motoring at full speed on the overlap, he hammers the ball across the six yard box taking out the entire defence and goalkeeper, Pelé at full stretch can't steer it home at the far post - xG: 0.79, but at full stretch it's a harder chance

- (v England) One of the most famous sequences in football history: Carlos Alberto plays a perfect 50 yard ball that beats England's defence and lands in Jairzinho's stride. With one touch to get to the goalline, the winger loops a fast cross to Pelé who is 10 yards out in line with the far post. Pelé heads the ball with power and precision towards the bottom corner of Gordon Banks' goal. Banks, scrambling low to his right and diving backwards deflects the ball up and over the crossbar - xG: 0.09, headers are hard

- (v Uruguay) The most famous dummy in football history. Tostao, in space, drives through midfield before spotting Pelé's run. His left-to-right throughball entices Uruguay goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz out from goal to stare down the oncoming Pelé, who beats Mazurkiewicz to the ball, then makes no touch, flummoxing the goalkeeper who misses everything. Pelé curves his run to fetch the ball towards the right of the box and has an empty net to swivel his shot towards and fill. Falling away on impact, his shot beats returning and desperate defenders, before bouncing past the far post - xG: 0.24, ultimately the shot is from quite wide

- (v Peru) Three minutes in, Gerson loops a ball towards Pelé who is lurking 30 yards out. With three defenders in close attention, Pelé controls with his knee and advances on the box before slotting a right footed shot past the goalkeeper. It bounces off the inside of the near post and across goal. Pelé hunts down the ball as it spins off past the other post and taking out three defenders with one move, backheels it to Tostao, who blazes over under pressure - xG: 0.41, he's done everything but score

- (v Czechoslovakia) Pelé faces a loose ball in his own half and rolling into the centre circle. Spotting an opportunity with Czech goalkeeper Ivo Viktor off his line he launches a Hail Mary of a shot, that sees Viktor turn to run back towards goal and watch it whistle past the top corner into touch - xG: 0.004, it's hard to score from your own half

- (v Uruguay) Mazurkiewicz fluffs his goal kick which goes straight to Pelé 35 yards out. He returns it instantly with some vigour straight back to Mazurkiewicz who claims - xG: 0.01, xG does not allow for audaciousness

- (v Peru) Pelé drives through into the final third and unleashes a powerful shot that goalkeeper Luis Rubiños can only parry onto his right hand post, before returning to collect - xG 0.04

When a player has a highlight reel of misses, yet was still the team's most important player and that team won the World Cup, well, that's special.

Pelé the creator should not be overlooked. He created over four chances per game for his teammates, with a huge xG Assisted value of 0.63 per 90 and directly assisted four goals. By examining his key pass chart we can see the deftness of Pelé's play. There are very few longer passes or crosses and most of these passes are in tough central areas; often Pelé had done the work to create the space for the shot and the set-up was the last thing required of him:

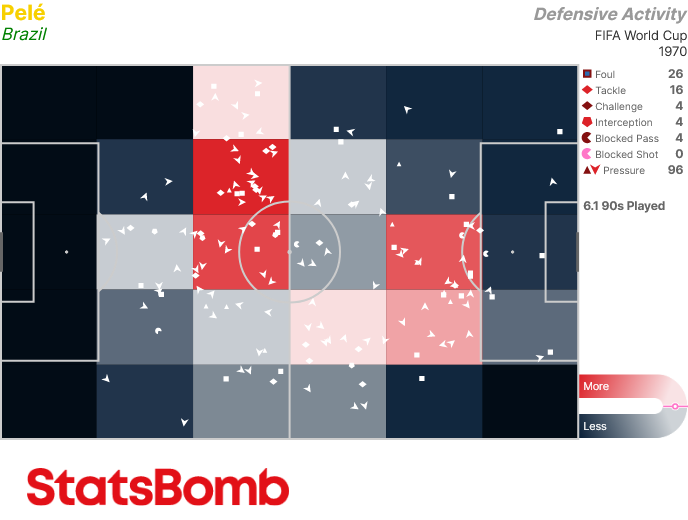

Nor should Pelé the defender be overlooked: for Brazil, only Clodoaldo exceeded Pelé's 2.6 successful tackles per 90 and his 15.5 pressures per 90 and we can see from this chart: the centre of the pitch was Pelé's domain:

Pelé was perfect to star in the first World Cup of the colour television era and he and his team won praise the world over as the beautiful game became more vibrant than ever before. His career continued for another seven years though, four more with his club team Santos, before a trailblazing entry to the United States and New York Cosmos, from which his and our last game is derived.

1977: The Final Appearance

Pelé played his final competitive match on 28th August 1977 as New York Cosmos overcame Seattle Sounders to win the 1977 Soccer Bowl. By this point Pelé had already retired once and left Santos in 1974, but lured out of retirement in 1975 he became a trailblazer for world stars finding a home in America's top league. His three seasons in New York were crowned by this victory, in a game which saw a similar hallmark to the other games we have reviewed - it involved 50 shots (26-24, Cosmos) and Cosmos won 2-1. To illustrate, below we have the pass network for the game, mainly to marvel at the luxury of a team fielding a spine of Carlos Alberto, Franz Beckenbauer and Pelé:

If you enjoyed this article, I highly recommend "The Boys From Brazil", a BBC documentary from the late 1980s that focused on the history of Brazil at the World Cup finishing in 1986. It is absolutely chock full of great Pelé moments and much more besides.

Accessing The Data

We've provided R (StatsBombR) and Python (StatsBombPy) packages to make working with the data a little easier, and published a 'Working With StatsBomb Data In R' introductory guide to support and accelerate the learning process.

As the Pelé dataset comes from multiple competitions and seasons, the easiest way to pull the data will be via the match IDs. Here's some sample code you can use to pull the data in both R and Python:

R

library(StatsBombR)

Comps <- FreeCompetitions()

Pele <- FreeMatches(Comps) %>%

filter(match_id %in% c("3888705", "3888704", "3888854", "3889218",

"3889217", "3888702", "3888701",

"3888700", "3888699", "3750234"))

events <-free_allevents(MatchesDF = Pele, Parallel = T)

events = allclean(events)

events<-merge(events, Pele, by="match_id")

events = get.opposingteam(events)

Python

ids = [3888705, 3888704, 3888854, 3889218, 3889217, 3888702, 3888701, 3888700, 3888699, 3750234]

events = []

for n in ids:

match_events = sb.events(match_id = n)

events.append(match_events)

events=pd.concat(events)

As always, if you use our data in any work you share publicly, please credit StatsBomb as the source (our logos can be found in our Media Pack).

*Please note that there were missing minutes from the video for a small selection matches. Subsequently, there are some games where the halves are slightly shorter than 45 minutes.

We look forward to seeing what you can do with the data.

The StatsBomb Team