If you asked football fans in the early years of this decade about the best midfielders in the world, the names you would most likely hear were Xavi, Andrés Iniesta and Andrea Pirlo. Xabi Alonso and Paul Scholes might not be too far behind.

What’s striking is just how associated they are with one specific attribute: passing. Xavi’s short passes in the middle third of the pitch were of such quality that, as his former manager Pep Guardiola described it, “he couldn’t lose the ball”. Pirlo turned the floated ball into the final third into an art form, while Alonso and Scholes (at least later in his career) excelled at the crossfield pass. Iniesta had a slightly different game, being a better dribbler and “changing the pace”, as Guardiola put it, but only in comparison to teammate Xavi would one claim that he was not a passing-focused player.

And as for today? There are still practitioners of the passing midfield game, but often with asterisks attached. Manchester City’s Kevin De Bruyne is certainly one of the most gifted passers around, but in a different way to previous Guardiola stars. “He is not a controller”, the Catalan manager claimed, but is instead “more dynamic, coming from behind, finishing, crossing, appearing here, then there, defending, attacking… less control and much more movement”. Fellow City midfielders David and Bernardo Silva are also wonderful technicians, but end up taking such advanced positions at times that there is a question over whether they should even be in this category.

The reigning Ballon d’Or winner Luka Modrić is a controller, but he does this through his dribbling ability and deceptively good work ethic without the ball as well as his superb passing talent. The most expensive midfielder in the world, Paul Pogba, also has a controlling passing range, but has such a wide range of skills that one could ask him to play any number of midfield roles. N’Golo Kanté, the only central midfielder to be named PFA Player of the Year in the past decade, is a great player for hugely different reasons. Perhaps only Toni Kroos fits the previous mould of passing controllers while sitting among the best midfielders in the world.

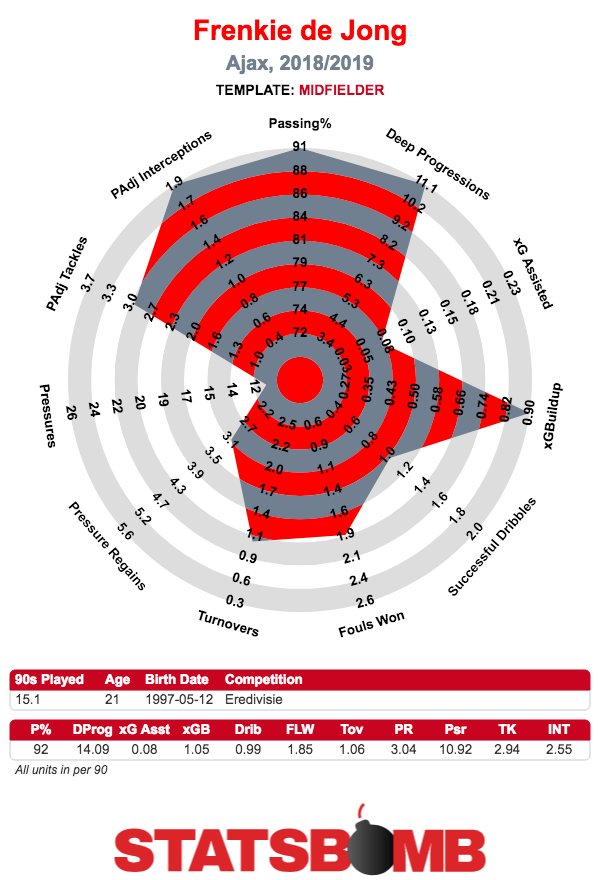

Looking ahead, Barcelona have just signed Frenkie de Jong to be the planned centrepiece of their midfield for the next decade. As Ryan O’Hanlon has noted at The Ringer, he is the future. What O’Hanlon means is that the game is becoming “much more frenetic”, and what is now needed is to “‘break the lines’ — i.e. dribble or pass through a band of attackers, a band of midfielders, and a band of defenders”, which De Jong does through “bombing dribbles and seam-splitting passes”. This marks a sharp contrast from the slower controlling passers we saw earlier in the decade. If Frenkie is the future, then Pirlo is the past.

Defense against the passing arts

In terms of how we got here, we have to look at clearly the most tactically significant side of the last decade: Guardiola’s Barcelona. In case you’ve been living under a rock, Guardiola’s team blended a possession focused, short passing style with the ball, hence the great emphasis on the “passing midfielders”, with an aggressive high press without it. Initially, the only tactical response teams had to this was to defend very deep and exploit space on the counter, done most famously by José Mourinho’s teams as well a Chelsea side looking to imitate the Portuguese manager’s approach with a number of his former players. Thus the view held by many at the time was that sides facing Barcelona must either sacrifice all ideas of good football and scrap with eleven men behind the ball for 90 minutes, or attempt to play their own game and suffer a noble defeat.

The first side to make a serious attempt to nullify Barcelona in a different way was in November 2011, when then Athletic Bilbao manager and high pressing advocate Marcelo Bielsa welcomed Guardiola’s men to the San Mamés stadium. Barcelona started the game with four passing midfielders: Xavi, Iniesta, Sergio Busquets, and Cesc Fàbregas, nominally playing the striker role. Athletic responded by not merely pressing high, but by doing so through two phases. As Michael Cox noted at the time, Bielsa instructed his players to “ Barcelona high up the pitch at goal-kicks and forced Víctor Valdés to kick the ball long” in the final third, while across the rest of the pitch in open play, the team played an outright man marking job. The strategy worked: not just were Athletic able to get a point against the best side ever to play football, but perhaps more symbolically, Xavi, the purest embodiment of the passing controller in midfield and typically the heartbeat of that Barcelona side’s build-up play, was taken off after 60 minutes for the much more direct Alexis Sánchez. Watching the game back all these years later, one of the most notable features is how hard Barcelona found it to move the ball forward through central areas. So often, Athletic were able to shut off Barcelona’s passing options. Bielsa had shown that, while Barcelona were great pressers themselves, they were not invulnerable to being pressed by opponents. Though the level of execution required was extremely high, a midfield heavily focused on passing could be pressed into submission.

La Liga was not the only league where pressing was becoming en vogue, of course. Over in Germany, “gegenpressing” (literally “counter pressing”, referring to pressing most aggressively in situations immediately after the ball has been lost) was taking the nation by storm, popularised by Ralf Rangnick and reaching dominance when Jürgen Klopp’s Borussia Dortmund won the Bundesliga title playing this way. This style involved some of the same principles as that advocated by Guardiola and Bielsa, but created something distinct. The emphasis is on not pressing constantly but in specific moments, the primary purpose being not to regain possession but rather to attack in fast transitions. “The best moment to conquer the ball is right after your own loss”, explained Klopp in 2012 (the quotes are in German, so apologies if anything has been lost in translation). “The opponent must first orient himself, look where he could play the ball. And pow, you’re already there”. The first thing this means is that the tempo of the attacking play is higher, meaning that a passing controller is often not just unnecessary but a detriment to the side, forcing the team to slow the game down. It also can cause significant problem for passing controllers on the opposing team. With the gegenpressing side easily able to press aggressively in the midfield, there can be a similar effect to what Bielsa achieved against Barcelona (albeit executed slightly differently), with the midfielder’s passing options shut off and the game played at a tempo difficult to dictate in. It’s notable that one of the few advocates of possession football in the Bundesliga during the rise of gegenpressing, Louis van Gaal at Bayern, struggled against Klopp’s Dortmund. In the last contest between the two in Germany, Dortmund were very fast to close down passing controller Bastian Schweinsteiger, forcing him to drop deeper and deeper and making him unable to influence the game. Klopp’s side won the game 3-1, and this style of football was on its way to dominance.

Press resistance is not futile

If the passing controller was no longer the best ticket to success, alternate strategies had to be developed. It was something that Pep Guardiola spent a long time trying to solve at Bayern, as he still wanted to build his midfield around Alonso. The now famous tactic of having full backs move inside to become additional central midfielders was certainly a part of this, lessening the load for Alonso while their flexible hybrid positions made them more difficult to press. But there was also a sense of a new view on the midfield role when he signed Arturo Vidal, a much more energetic, physical player than one could ever imagine his Barcelona side fielding (that Vidal himself now plays at the Camp Nou is an irony surely not lost on anyone, with even the spiritual home of passing football adjusting). Now at Manchester City, Guardiola doesn’t even play with a passing controller at all, with Fernandinho a more defensively focused holding player whose passing skills in transition allow those in front of him to move into attacking roles more frequently.

Elsewhere, a new kind of midfielder emerged, one who could move the ball through midfield while being able to withstand the pressure. The obvious player who typifies this is Mousa Dembélé. Starting his career in his native Belgium and really emerging in the Netherlands at Van Gaal’s AZ Alkmaar, the first part of his career was in an advanced role. His most notable skill is being able to dribble under pressure without losing the ball, and at that time, the areas of the pitch where one dribbles were out wide or in the final third. For a possession football advocate in this era, even one as tactically astute as Van Gaal, central midfield was not where you used Dembélé’s skillset.

After being used to mixed effect by various managers in England, Dembélé’s career hit another gear under Mauricio Pochettino. After having problems with the double pivot of Nabil Bentaleb and Ryan Mason in the Argentine’s first season in charge, Dembélé took up a starting role in midfield alongside Eric Dier and became an integral piece in the side. Dembélé in this role defined press-resistance. It became nearly impossible to win the ball from him, so comfortable was he at shirking attempts to challenge him, maintaining calm at all times under pressure. His combination of technique and physical attributes made him perhaps essentially impossible to press out of the game in his peak years. He evoked Guardiola’s claim that Xavi “couldn’t lose the ball”, but in an entirely different way. While inferior in other ways, it’s hard to imagine Bielsa’s Athletic side pressing Dembélé out of the game. The controller was reborn, now as a player who could dictate the game by withstanding opposition pressure and moving the ball forward nonetheless.

Though none have yet managed it quite as well as the Belgian, football has started to look for other Dembélé-like players. Gini Wijnaldum at Liverpool is an obvious example. Wijnaldum certainly isn’t as good a player as Dembélé, often taking risk-averse options and seemingly choosing not to take advantage of his natural dribbling talent. But, like the Belgian, he has a talent for evading pressure and remaining invulnerable to attempts to force him out of the game.

Another similarity is that both spent the earlier part of their careers higher up the pitch, often out wide, but have now been reinvented as central midfielders in an era where press-resistance is so necessary. Also at Liverpool, though still in a slightly more advanced role, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain has seen a similar evolution. A central midfielder in his youth career, his time at Arsenal saw Arsène Wenger generally field him out wide. Klopp, now of course at Liverpool, has found more value in Oxlade-Chamberlain when playing in central areas, with the Englishman an ideal player both to trigger his “gegenpress as playmaker” approach, and able to use his strength and dribbling ability to withstand pressure. It’s hard to imagine Oxlade-Chamberlain thriving as a central midfielder at a top European side in 2012, but evolving trends in football have made his skillset more valuable.

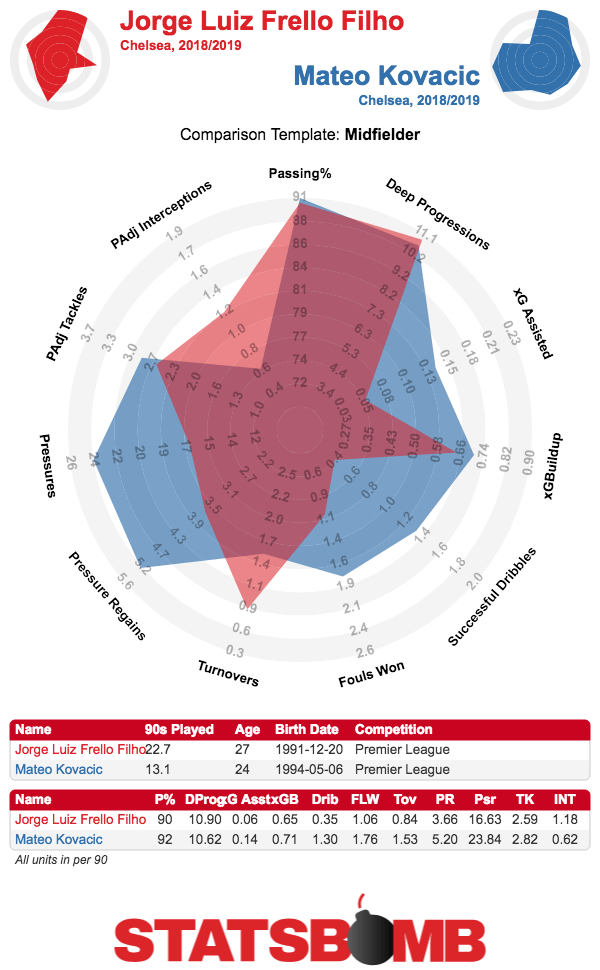

Just as there are winners to a new style taking hold, there are losers. Jorginho was signed by Chelsea to be the heartbeat of the Maurizio Sarri revolution, a true passing controller as the deepest midfielder in a possession focused 4-3-3. And he’s doing plenty of the thing he was signed for, finding himself third in the Premier League this season in deep progressions per 90 (and it’s worth noting that the top two both play for Manchester City, who dominate the stat). What he hasn’t been able to do, however, is evade pressure. Dele Alli was able to nullify him when Chelsea went to Wembley in the league this season in a way not dissimilar to Bielsa’s man marking approach on Barcelona, and his worst performances have come when sides have deliberately targeted him.

He seemingly doesn’t have an answer to being pressed. If Jorginho had been at his peak in 2012, he’d have likely been regarded as one of the best midfielders in world football. In 2019, he seems too easy to nullify. It’s understandable that some Chelsea fans are advocating for Mateo Kovačić, a much better dribbler and a more robust, press-resistant player, to start in his place. Jorginho’s struggles this season do not mean that he will never be a success at Chelsea, but there will have to be a tactical solution that avoids it being so simple to limit what he can do.

And so we come to Frenkie. Arriving at the once home of the passing controllers, De Jong has the potential to become the pinnacle of this new press-resistant style of midfielder. Of course, tactics come in and out of fashion all the time. The dominance of pressing may wane in the years to come, and the most useful skill a midfielder needs may be the ability to make incisive passes that break open a deep defence. De Jong may have to adapt to a different style of game when he reaches his late twenties. There is no way of telling the future. What is clear, though, is that having a strategy and the right players capable of dealing with being pressed in midfield is a must for any top side.