Less than two weeks on from the conclusion of the 2023/24 domestic season, this has already been one of the more fascinating managerial marketplaces in recent memory. Not only are many of the elite teams in European football making changes, but we’re also seeing what feels like the realisation of a shift in mindset for the types of managers that are being sought.

Vincent Kompany to Bayern Munich, Enzo Maresca to Chelsea, Fabian Hürzeler to Brighton, Kieran McKenna being linked with numerous vacancies higher up the food chain… top European clubs now seem to be putting more emphasis on identifying managers that can deliver a certain style of play over those that have already achieved results on the biggest of stages.

It’s a trend that I believe somewhat prompted Jose Mourinho’s post-Champions League final comments about Carlo Ancelotti: "He's not a social media coach, he's a proper coach. He comes from the meritocracy. Go to his office and see how many medals (he's won)."

"Ask the Real Madrid players what they think about the ball possession Man City had or this final's first half. They put the trophies above their philosophy."

Of course Ancelotti is one of the elite managers in football history, there is no disputing that, and I understand the point Mourinho is trying to make. But I also think that he’s been quite opportunistic and chosen an edge case to push forward his agenda. Few clubs in world football have the luxury of being able to assemble a squad from the top 0.1% of talent available, as Real Madrid do. And if you don’t, then you need to recruit both players and managers to fit an overarching game model that allows for succession planning and future-proofing your club.

The merits of recruiting to a game model have been discussed at length elsewhere. I don’t wish to fight that fight in this piece. What I do want to do is show that style is measurable. Data can play a big part in the process of identifying a high-quality manager, but perhaps it is most effective in giving pointers towards a manager’s style of play.

Quality matters

What we mean when we talk about quality in this context is, broadly speaking, a manager’s ability to win football matches. This is what Mourinho was referring to when he talked about putting trophies above a philosophy. After all, success on the field of play is, for the most part, the number one priority for all football clubs.

However, because results are so intrinsically linked to the quality of players available, it’s rarely straightforward to separate the two. So assessing a manager’s ability to win games is not as easy as we’d like.

You can do some work comparing squad budgets to league performance and get a proxy for those that are overperforming expectations. Or you could also try to create some sort of player-quality model and use this to compare expected and actual performance, but these sorts of models are expensive (in terms of manpower) to create, fragile at best when you do so, and ultimately unrealistic for most football clubs.

All that said, there is still some basic analysis that we can, and certainly should, carry out.

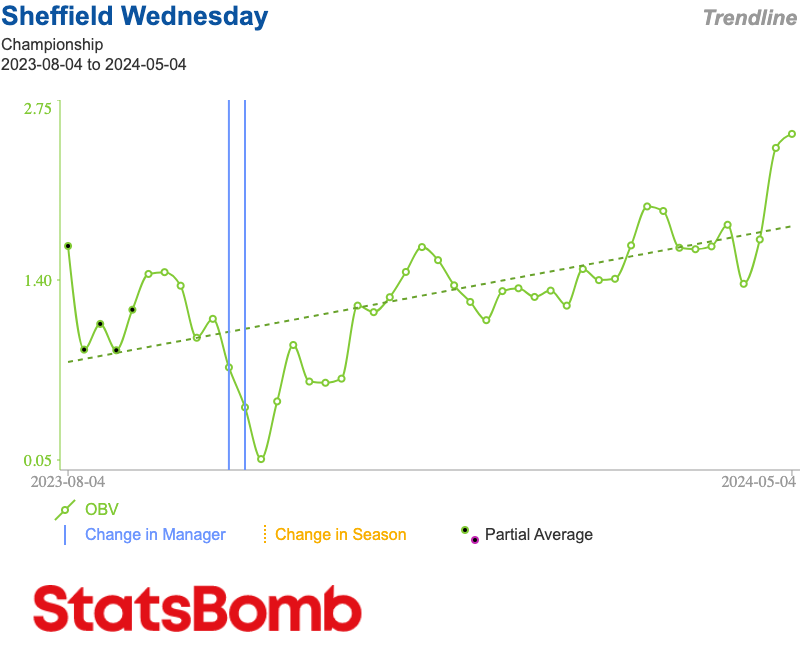

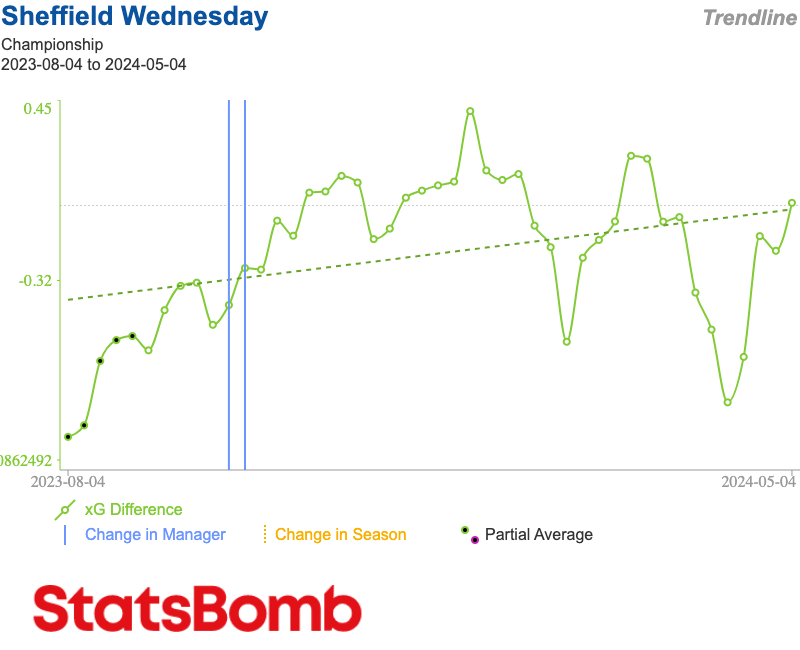

Comparing the expected goal (xG) difference of a team in the period before and after a manager arrives at a club gives some indication of the impact they’ve had on what is likely to be a similar group of players (note: sample size is important here, and we should also be conscious of the impacts of the strength of schedule on either side of the line).

For example, we can look at Sheffield Wednesday and the periods before and after their managerial change in October 2023 and identify a clear uplift in the xG Difference after Danny Röhl’s arrival at Hillsborough. Because we also know that the playing staff is largely unchanged from before and after the managerial switch, we can give some credit to the new manager.

xG Difference is a good measure of chance creation versus chance concession, and a strong starting point for identifying overall team quality.

There are other standard metrics that we can use here to assess performance levels. OBV - to help analyse quality of play that may not result in a shot on goal, and therefore won’t be picked up in the xG numbers - and Deep Completions - as a proxy towards how much control a team has in the final third - are just two further examples.

Style and substance

Where we can analyse data in more depth, however, is in relation to a manager’s style of play.

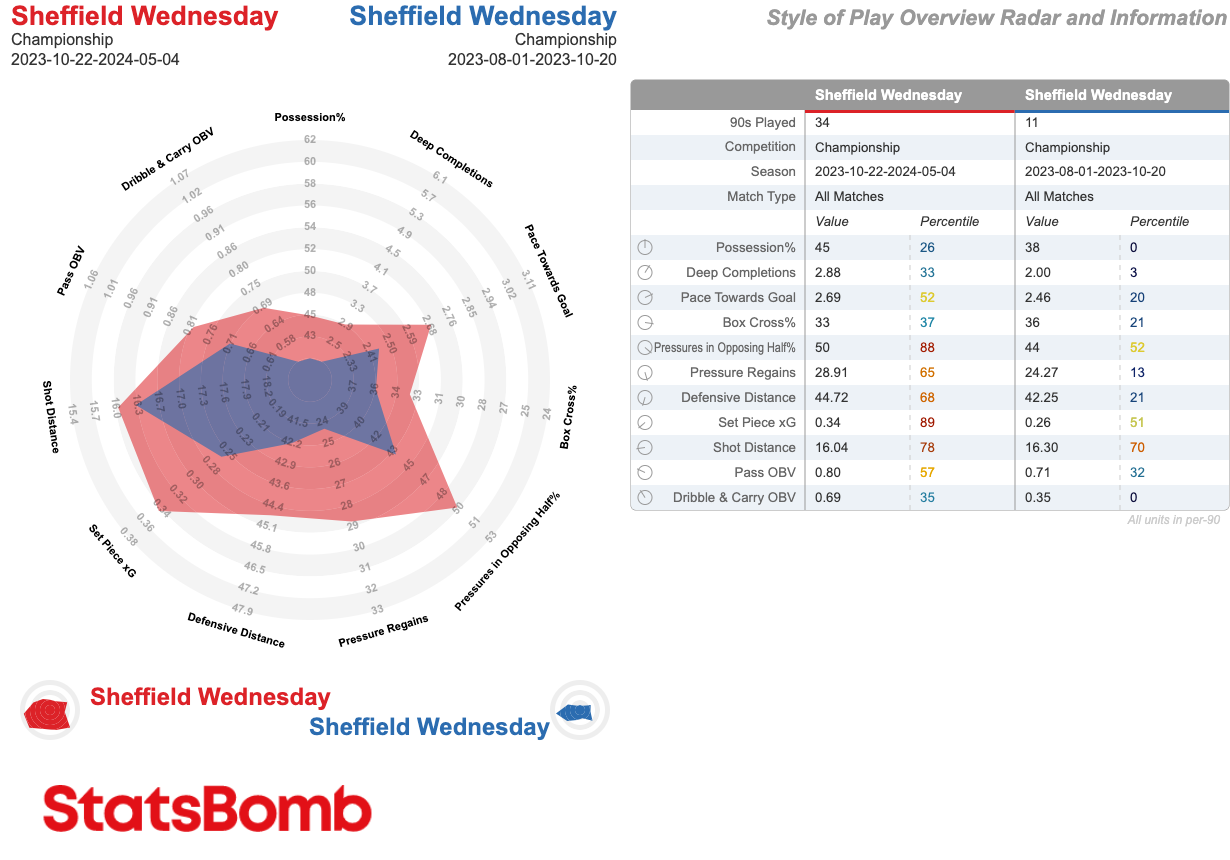

We can get a quick insight into this using the StatsBomb IQ platform by comparing some team style metrics (filtered to periods where a specific manager has been in charge) and comparing the two.

I have no insight into the style of play that Sheffield Wednesday want to implement, or even if they have a particularly focussed game model. But I can see that as a manager, Röhl has successfully converted his team into one that defends higher up the pitch (Defensive Distance), presses more aggressively in opposition territory (Pressures in Opposing Half %), has better control of the ball - both in the final third (Deep Completions) and overall (Possession%) - and transitions more quickly (Pace Towards Goal).

That isn’t to say that Röhl’s chosen style of play is the only way to improve results, but in the process of identifying and hiring a new manager it is at least useful information to have when looking for a custodian to take the club forward both for the medium- and long-term vision.

With this high level overview, we can then look to get a bit more nuanced in our analysis of metrics that our club particularly cares about.

The current in vogue style of play in football involves high pressing and intensity out of possession, and some form of possession-based, playing-out-from-the-back when with the ball. These things are cyclical and at some point the stylistic metrics that are most important will change, but for the purposes of this piece I will look at metrics related to the things that seemingly matter most right now.

Passing style

Pass length

We can decipher quite a lot about a team’s style of play by simply looking at the verticality (how far they advance the ball forwards) of passes from specific areas of the pitch.

Dyche-ball is what Dyche-ball does. Also no surprises with the likes of Manchester City and Brighton.

As with most analysis, the devil is in the detail, however. Oliver Glasner’s Crystal Palace are the second most direct team from the defensive third, but slot in at around mid-table when looking at passes from the middle third of the pitch. On the flip side, Ange Postecoglu’s Tottenham team have second shortest verticality of passes from the defensive third, but are more direct than nine other Premier League teams when it comes to the average length of middle third passes.

Defensive third build up - Pass clusters

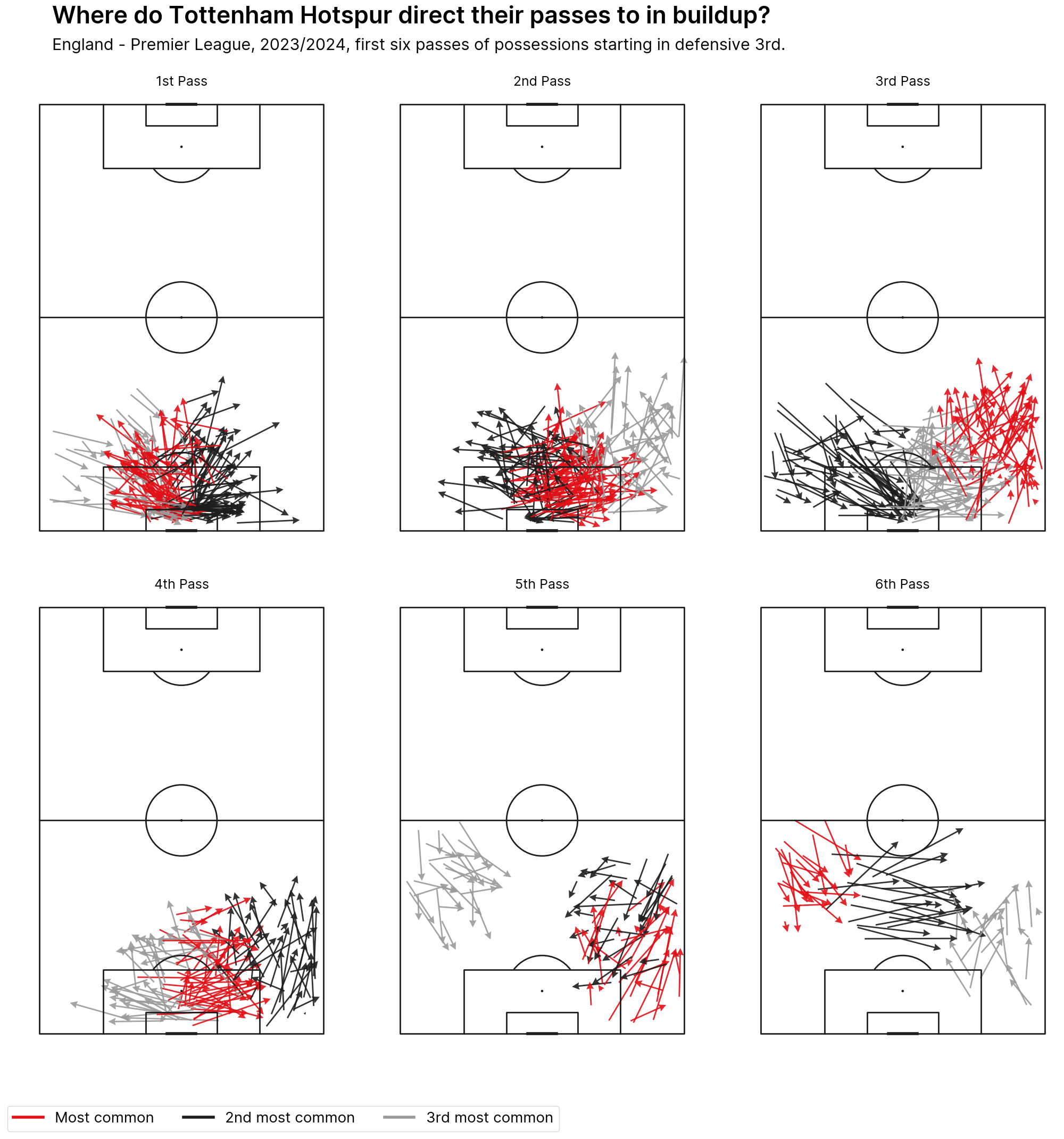

We can get even more refined with our analysis of what happens in specific areas of the pitch by identifying and analysing common pass clusters.

The below takes a closer look at what it is that Spurs do most often with their passes in the build-up phase by looking at most common pass clusters of possessions that begin in the defensive third. This level of analysis can help us to ensure there is nothing significant that is being lost in the aggregates.

In this instance we can see a strong trend of shorter passes that are contained within their own half, as well as a tendency to make more progressive passes up the touchline on the right side. Analysis of some teams may reveal a more varied approach that could get lost in the averages.

Player involvement per possession

If your club’s game model involves playing out from the back, and you have spent time and money assembling ball-playing centre backs, then you’re going to want a manager that involves their centre backs in possessions.

Or maybe your club has got a prized asset who plays on the wing that you want to develop and showcase their ball carrying/dribbling skills, in that case you’re going to want a manager that regularly asks his wingers to carry the ball when in possession.

In this example, I’ve looked at teams from Europe’s 'Big 5' leagues collectively, and highlighted one that makes particular use of their CBs - Sebastian Hoeneß’s Stuttgart - and another that heavily involves their attacking midfielders and wingers in possessions - Manuel Pellegrini’s Real Betis.

Out of possession

We can use out-of-the-box counting metrics such as Pressures, Pressures in the Opposition Half, and Counterpressures to get a good indication of a team’s pressing intentions. Pressure Regains will also help to indicate whether or not a team is generating possession turnovers from their out-of-possession actions. However, ball dominant teams may not show up in these metrics: if you have the majority of the ball, then your opportunities to show your out-of-possession qualities are minimised.

Pressing effectiveness

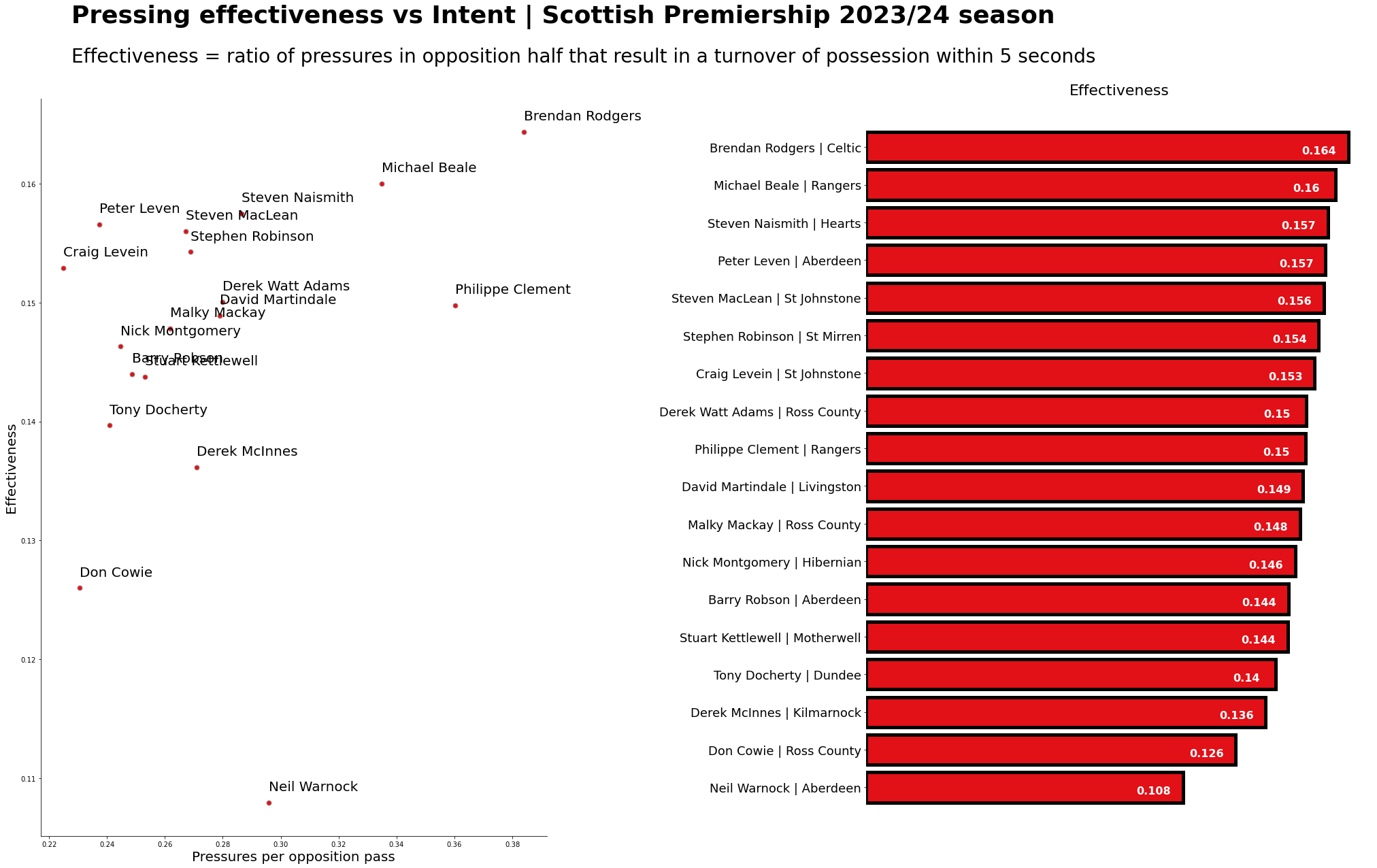

With some minor manipulation of the data we can get a proxy for pressing effectiveness by looking at how often a pressure in the opposition half results in a turnover in possession within five seconds (a Pressure Regain). And then also do some basic possession adjustment (pressures per opposition pass, in their half) to get an idea of intent.

Comparing the two then gives a slightly more detailed overview of a manager/team’s pressing qualities.

If you want a manager that can coach an effective press, then the suggestion here is that Neil Warnock is definitely not your man.

But if you want someone that can be both aggressive and effective then Brendan Rodgers ticks both boxes.

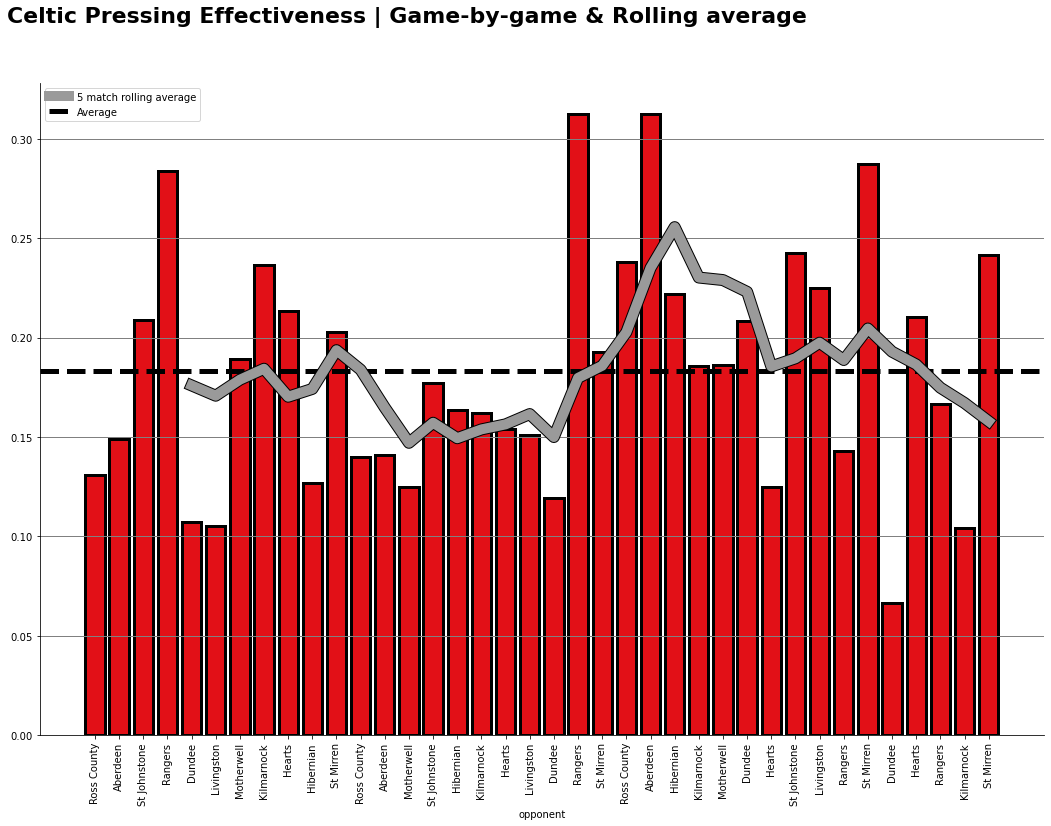

We may also want to dig even deeper once we’ve identified what we believe to be a good pressing team/manager, and break it down by game or period of the season and see if there are any further takeaways.

Games between Celtic and Rangers are always pivotal in the Scottish Premiership and it’s interesting that two of Celtic’s best pressing games (as measured by this bespoke Pressing Effectiveness metric) are against their Glasgow rivals. There’s also a notable uptick around the midpoint of the season - why might this be? Did the manager change something that we can identify with further scrutiny of video? Or perhaps key personnel returned to the side? Reality is that it’s probably a mixture of reasons, including being knocked out of the Champions League and the consequential relaxation of their fixture schedule in conjunction with some attempts to best manage loads in the early part of the campaign.

Summary

That final point is probably the most pertinent. Data won’t give you all of the answers, in fact it often raises more questions. It will not tell you which manager to hire, just as it won’t tell you which players to sign. But it most certainly can steer you in the right direction.

The best managers are flexible. They can and will adapt what they do and how their teams play. And just because a coach hasn’t previously shown signs of playing a certain style doesn’t mean that they can’t in the future. But if you want your team to play with an aggressive and effective high press, for example, then knowing which managers have coached teams that press aggressively and effectively is most certainly useful information to have.

The meritocracy does not exist in isolation from a well-thought-out and carefully executed longer-term vision. In fact, when it comes to well-run football clubs, the two are simpatico and profiling your club’s next manager’s preferred style of play is becoming increasingly prevalent.