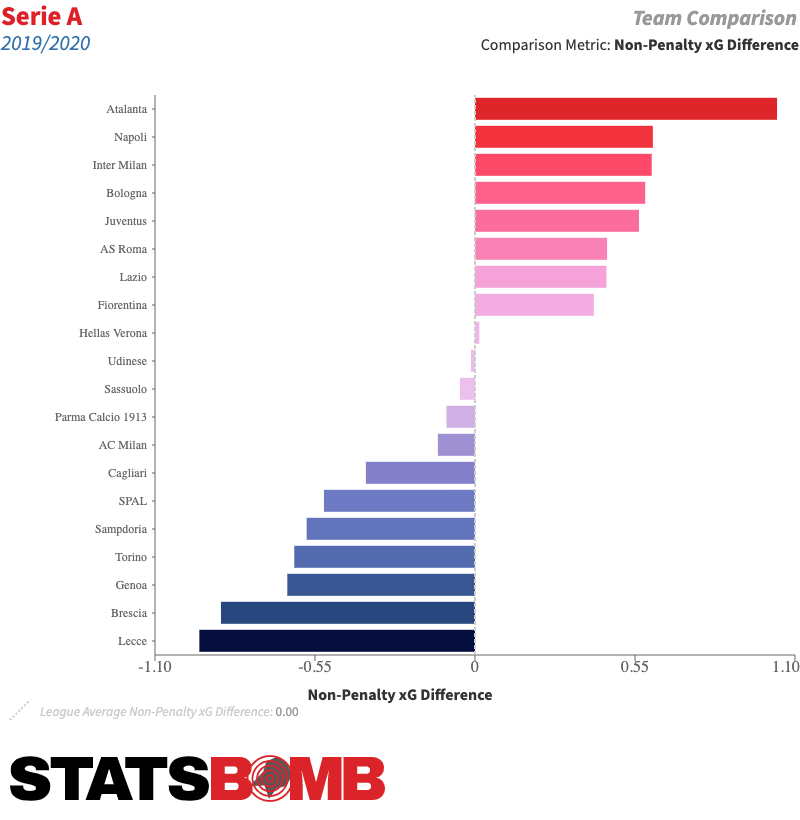

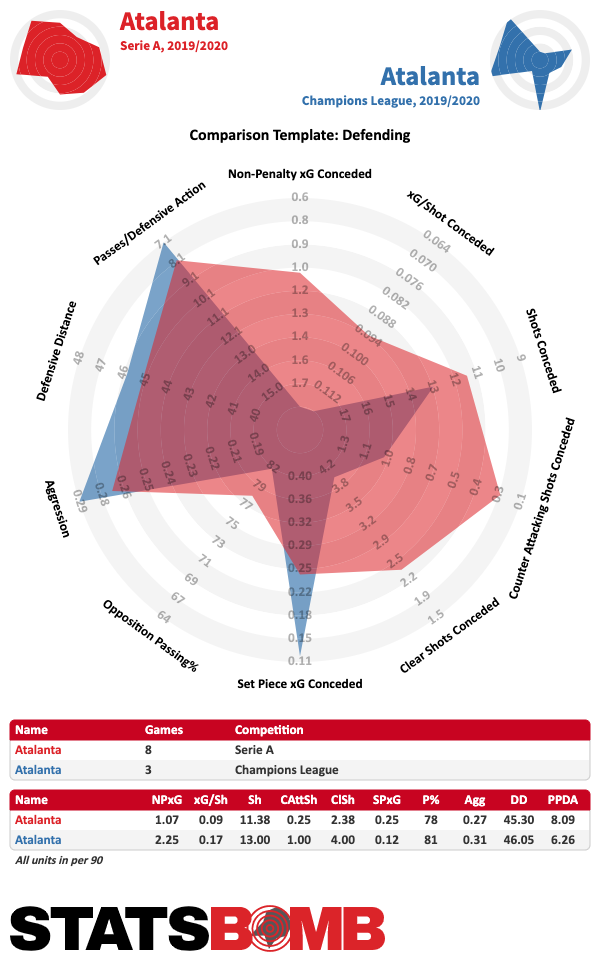

A version of this article can also be found in Italian at l'Ultimo Uomo Three games, three defeats, two goals scored, 11 conceded: Atalanta's debut in the Champions League could not have been worse. Gian Piero Gasperini's team had already jeopardized its chances of entering the round of 16 with the disastrous 4-0 suffered at the hands of Dinamo Zagreb. That was followed by a last minute1-2 home defeat against Shakhtar Donetsk, a result which does not entirely do justice to what was a good performance from the Nerazzurri. Tuesday’s 5-1 debacle at Etihad Stadium could be the final blow for a team that was considered to be the second strongest in the group, behind Guardiola's Manchester City. It's disappointing for last season's third-place finishers in Serie A. Despite the offers for their many high-quality players, however, Atalanta's roster was not raided during the summer. The Bergamo club is not a one-season-wonder: the management established a consolidated growth strategy with manager Gasperini at its center and the team was even reinforced during the transfer campaign, especially with the arrivals of Ruslan Malinovskyi and Luis Muriel. Things are going reasonably well in the Serie A and Atalanta are third in the standings ahead of Napoli, thanks to the best attack in the league (21 goals so far). Looking at their numbers in more detail they look even stronger: the “Goddess” is by far the team with the most expected goals generated (2.11 xG per match), ironically a figure lower only than that of Manchester City in all Europe.  In fact, only Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain and Bayern Munich have a greater xG difference in the big 5 than the Nerazzurri (+1.04 xG per game). Atalanta is a real offensive force and their games are the most exciting in the league. There are matches in which Papu Gomez and his teammates seem to be able to bend the resistance of any defense and get into the box with a snap of their fingers. The problem is, as Guardiola reminded us, that the team that was annihilated by Sergio Agüero and Raheem Sterling is the same team one that, on Saturday after the first half, were winning 3-0 at the Stadio Olimpico against Lazio and then conceded a disputed 3-3 comeback from the Biancocelesti. In the Champions League, the team led by Gasperini has simply not been as dominant. Luck and variance surely played their part: they've scored just one open play goals so far out of 4.09 xG. At the same time, they conceded 10 non-penalty goals from 6.97 xG. The side's average xG generated per game is down to 1.31, better than Napoli (1.28 xG) and Inter (1.08 xG), but not up to the level of their domestic league standards. That is still a competitive number, but the amount of xG they've allowed is terrible. Atalanta is the fourth-worst team in the competition with 2.25 xG conceded per match. A figure more than twice the amount allowed in the Serie A, where they are much better than the average at 1.07 xG conceded per game.

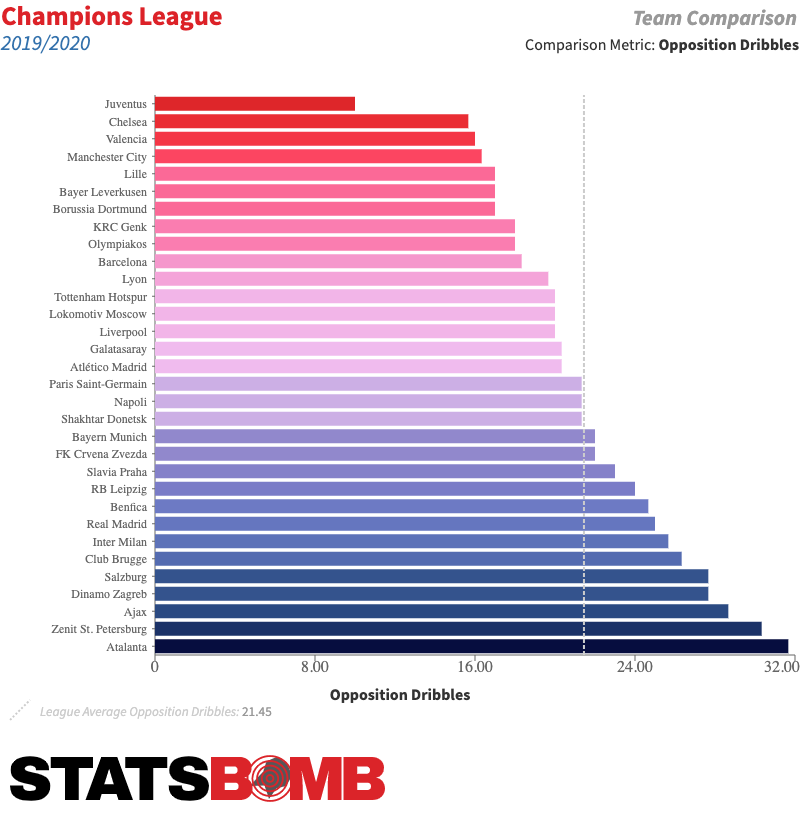

In fact, only Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain and Bayern Munich have a greater xG difference in the big 5 than the Nerazzurri (+1.04 xG per game). Atalanta is a real offensive force and their games are the most exciting in the league. There are matches in which Papu Gomez and his teammates seem to be able to bend the resistance of any defense and get into the box with a snap of their fingers. The problem is, as Guardiola reminded us, that the team that was annihilated by Sergio Agüero and Raheem Sterling is the same team one that, on Saturday after the first half, were winning 3-0 at the Stadio Olimpico against Lazio and then conceded a disputed 3-3 comeback from the Biancocelesti. In the Champions League, the team led by Gasperini has simply not been as dominant. Luck and variance surely played their part: they've scored just one open play goals so far out of 4.09 xG. At the same time, they conceded 10 non-penalty goals from 6.97 xG. The side's average xG generated per game is down to 1.31, better than Napoli (1.28 xG) and Inter (1.08 xG), but not up to the level of their domestic league standards. That is still a competitive number, but the amount of xG they've allowed is terrible. Atalanta is the fourth-worst team in the competition with 2.25 xG conceded per match. A figure more than twice the amount allowed in the Serie A, where they are much better than the average at 1.07 xG conceded per game.  But how do you explain such an important drop in performance between Italian and European games? Is it the Champions League anthem that makes the legs of Atalanta players shake? Or is there such a difference in level between Serie A and the Champions League that the third strongest force in Italy can only be the sacrificial lamb of the group? Indeed, there is a significant gap between Juventus and the other Italian teams and the European experience of Gasperini's men is limited. But the last time Atalanta made landfall in England before the Etihad’s match, they won 5-1 at Goodison Park against Everton in the Europa League 2017-18. In Italy, much has been written about how Atalanta has not managed to maintain the same intensity as in Serie A games, simply because they played teams able to compete with them in this respect. But this is far from being confirmed by the data. Indeed, the Nerazzurri have the lowest PPDA in the CL (6.26), recorded 30 more pressures on average than in their Serie matches and they also defended slightly further from their goal. They also have the third-best aggression coefficient of the tournament at 0.31, a metric that measure what proportion of an opponent's passes are aggressively pressed. There are surely multiple concurrent factors, but there is a clear tactical motive at the root of Atalanta's struggles. Dribbles. Anyone who watches Serie A games, even if distractedly, knows that Gasperini uses man-to-man marking, especially during the pressing phase. Man marking creates a series of individual duels along the entire field. If an opponent manages to get free on an individual level, that can be the basis to unbalance Atalanta’s whole structure. By adopting a flexible marking system, the Nerazzurri can still adapt switching off players from one another. But every time a defender is dribbled the situation has the potential to become catastrophic. And in the Champions League, the Nerazzurri have been dribbled a ton of times. You don’t need to be a tactical genius like Pep is to analyze Tuesday’s game like he did “When we could get in the last third, it is man to man and if you win a duel you have an opportunity”. League rivals have understood that dribbling is a key weapon against Atalanta, which is the team with the highest opposition dribbles attempted in the Serie A (22.88 per game). Dinamo Zagreb, Shakhtar Donetsk, and Manchester City have adopted the same strategy by trying even more dribbles (31.67 on average, naturally the most in the tournament).

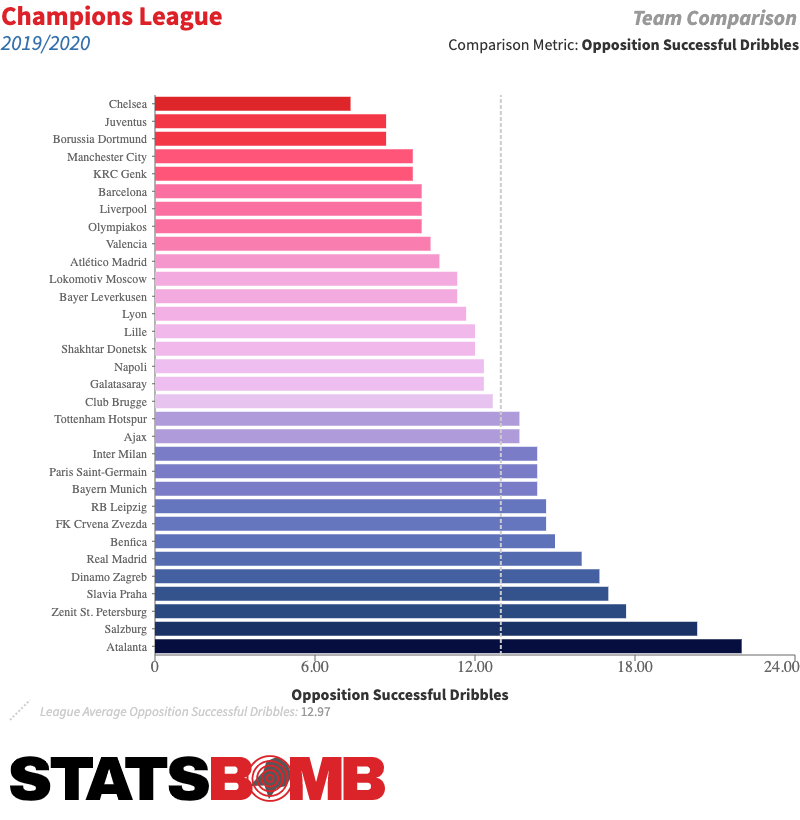

But how do you explain such an important drop in performance between Italian and European games? Is it the Champions League anthem that makes the legs of Atalanta players shake? Or is there such a difference in level between Serie A and the Champions League that the third strongest force in Italy can only be the sacrificial lamb of the group? Indeed, there is a significant gap between Juventus and the other Italian teams and the European experience of Gasperini's men is limited. But the last time Atalanta made landfall in England before the Etihad’s match, they won 5-1 at Goodison Park against Everton in the Europa League 2017-18. In Italy, much has been written about how Atalanta has not managed to maintain the same intensity as in Serie A games, simply because they played teams able to compete with them in this respect. But this is far from being confirmed by the data. Indeed, the Nerazzurri have the lowest PPDA in the CL (6.26), recorded 30 more pressures on average than in their Serie matches and they also defended slightly further from their goal. They also have the third-best aggression coefficient of the tournament at 0.31, a metric that measure what proportion of an opponent's passes are aggressively pressed. There are surely multiple concurrent factors, but there is a clear tactical motive at the root of Atalanta's struggles. Dribbles. Anyone who watches Serie A games, even if distractedly, knows that Gasperini uses man-to-man marking, especially during the pressing phase. Man marking creates a series of individual duels along the entire field. If an opponent manages to get free on an individual level, that can be the basis to unbalance Atalanta’s whole structure. By adopting a flexible marking system, the Nerazzurri can still adapt switching off players from one another. But every time a defender is dribbled the situation has the potential to become catastrophic. And in the Champions League, the Nerazzurri have been dribbled a ton of times. You don’t need to be a tactical genius like Pep is to analyze Tuesday’s game like he did “When we could get in the last third, it is man to man and if you win a duel you have an opportunity”. League rivals have understood that dribbling is a key weapon against Atalanta, which is the team with the highest opposition dribbles attempted in the Serie A (22.88 per game). Dinamo Zagreb, Shakhtar Donetsk, and Manchester City have adopted the same strategy by trying even more dribbles (31.67 on average, naturally the most in the tournament).  Atalanta manages to contain the opposing dribblers in the league where they have the second-best opposition dribble percentage (55%), but in the Champions League they have been posed against top-class dribblers and the percentage has inevitably risen to 69%, for 27th in the tournament. With a higher volume of attempts completed at a higher rate, the number of successful dribbles inevitably rises from 12.5 opposition successful dribbles per game in the Serie A, to almost twice the amount in the Champions League (22.0). Obviously, Atalanta is the worst team in the tournament in this statistic.

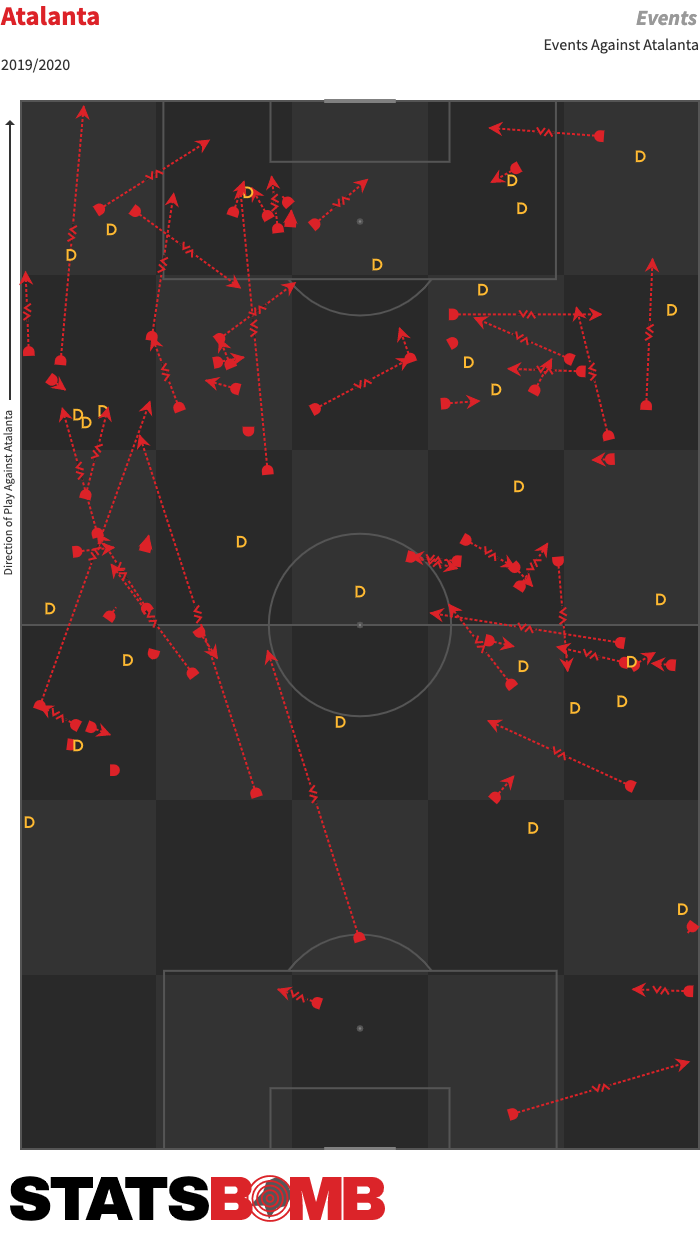

Atalanta manages to contain the opposing dribblers in the league where they have the second-best opposition dribble percentage (55%), but in the Champions League they have been posed against top-class dribblers and the percentage has inevitably risen to 69%, for 27th in the tournament. With a higher volume of attempts completed at a higher rate, the number of successful dribbles inevitably rises from 12.5 opposition successful dribbles per game in the Serie A, to almost twice the amount in the Champions League (22.0). Obviously, Atalanta is the worst team in the tournament in this statistic.  In just three games, nine players have completed at least three dribbles against Atalanta. Bruno Petkovic (10! dribbles), Dani Olmo (9!) and Arijan Ademi (4) for Dinamo Zagreb, Marlos (6) and Junior Moraes (3) for Shakhtar, Kevin De Bruyne (5), Raheem Sterling (5), Phil Foden (3) and Kyle Walker (3) for Man City. You can see a chart of all the dribbles allowed by the Italians, highlighting how a high number of dribbles have happened in highly valuable zones, where a lost individual duel could pose an enormous pressure on the defense.

In just three games, nine players have completed at least three dribbles against Atalanta. Bruno Petkovic (10! dribbles), Dani Olmo (9!) and Arijan Ademi (4) for Dinamo Zagreb, Marlos (6) and Junior Moraes (3) for Shakhtar, Kevin De Bruyne (5), Raheem Sterling (5), Phil Foden (3) and Kyle Walker (3) for Man City. You can see a chart of all the dribbles allowed by the Italians, highlighting how a high number of dribbles have happened in highly valuable zones, where a lost individual duel could pose an enormous pressure on the defense.  Even reviewing the 11 goals conceded by Atalanta, goals that often came from inside the 6-yard box, one often notices how opponents avoid man-marking or dribble an opponent in the build-up for the shot. One of Gasperini's team strengths has been exposed to the point of becoming their main weakness. Not all clubs can deploy multiple high-level dribblers, but it is not to be excluded that we will see more and more teams use dribbling, even in an exaggerated fashion, against Atalanta which will have to find effective counter moves as soon as possible if they want to consolidate their status in high-level European football.

Even reviewing the 11 goals conceded by Atalanta, goals that often came from inside the 6-yard box, one often notices how opponents avoid man-marking or dribble an opponent in the build-up for the shot. One of Gasperini's team strengths has been exposed to the point of becoming their main weakness. Not all clubs can deploy multiple high-level dribblers, but it is not to be excluded that we will see more and more teams use dribbling, even in an exaggerated fashion, against Atalanta which will have to find effective counter moves as soon as possible if they want to consolidate their status in high-level European football.

2019

What went wrong for Atalanta in the Champions League?

By admin

|

October 25, 2019