All sports are defined by their objectives and the constraints within which those objectives can be achieved.

In football, the objective is to score more goals than your opponent. Ergo, every decision taken or action carried out on a football pitch should be (and almost exclusively is) an attempt to increase your own team’s chances of scoring a goal and/or decreasing your opponent’s chances of scoring a goal. Usually there are a subset of micro decisions and executions that contribute to the success of any of these given actions, but the end goal remains constant.

How a team/manager sets about achieving those objectives is the fun part, which brings me on to the focal point of this blog post: Route One/Direct/Long Ball football.

My intention in the coming paragraphs is to analyse the effectiveness of teams in implementing a long ball strategy, i.e. are they improving their own chances of scoring goals, and/or decreasing their opponent’s chances of scoring goals, and to try and identify traits that contribute to those outcomes. As I have mentioned in previous blog posts, I’ve very little skin in the game for professing what is the ‘right’ way of doing things on a football pitch (take that shot from outside the box, for all I care), but I do strongly believe that if you’re doing something then you should measure whether it is effective in achieving your end goals. And then if it’s not, do something about it.

*pause for profound philosophical thinking.*

Before we progress, if we’re going to talk about long balls, then we need to define what a 'Long Ball' is. Likewise, 'Meaningful Possession' which I will also use. Outside of this writing these are not gospel, and there are admittedly some subjective boundaries used - I ain't no data scientist - but you’ve got to make some decisions somewhere, so here we are.

Long Ball

- An open-play pass

- Originating in the defensive or middle 3rd of the pitch

- That ends in the attacking 3rd of the pitch

- Has a vertical distance of greater than or equal to 40 (pseudo) yards

- Is a ‘High Pass’

- Is not a cross, and

- Is not pressured (for the purposes of this I want to capture when teams choose to go long, rather than when they are forced to go long)

Meaningful Possession

- Any of the below occurring within 10 seconds of the Long Ball;

- A completed pass (with the feet) originating in the final 3rd of the pitch (N.B. I’ve used footed passes only to ignore ‘completed passes’ that come from the original flick on of the long ball, or such like)

- A carry or dribble of distance greater than or equal to 5 (pseudo) yards originating in the final 3rd of the pitch

- A shot.

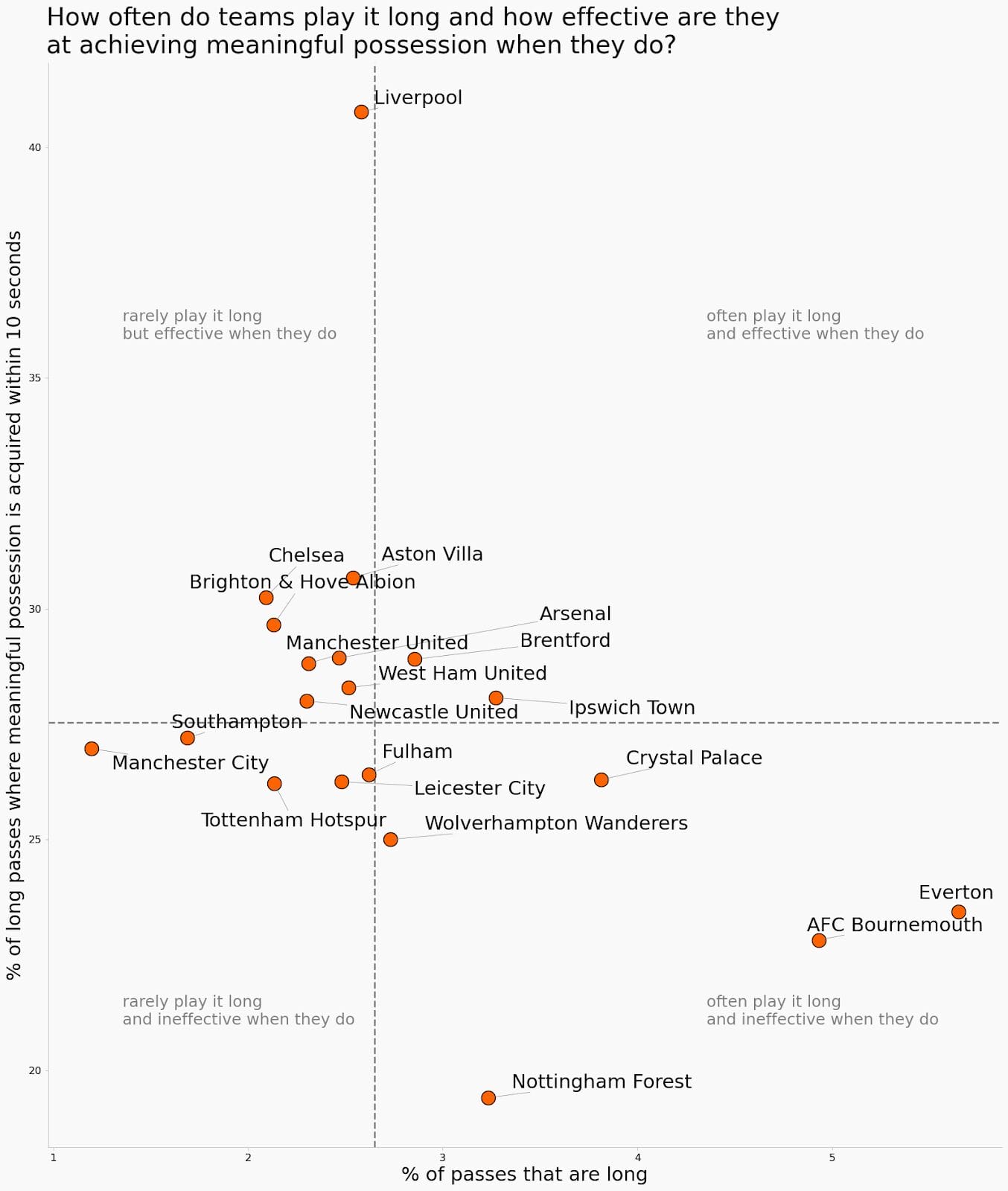

With that defined, here’s a snapshot of Premier League outputs for the season up to 17th January 2025 (before David Moyes’ first game in charge at Everton), which will serve as a starting point for my analysis.

Some takeaways;

- Liverpool are fairly middle of the road for the league in how often they choose to go long, but when they do go long they are extremely effective in gaining Meaningful Possession

- Everton and Bournemouth go long more often than most relative to the amount of possession they have, but are ineffective in attaining Meaningful Possession when they do

- Forest are extremely ineffective when they go long (evidence that this is in no way a barometer for overall success), but don’t do it as often

- Manchester City and Southampton rarely ever go long (where would we be without data driven insights!?).

It’s worth acknowledging at this point that even those teams highlighted as being more enamoured to a long ball are only playing this type of pass around 5% - 6% of the time. There’s a heck of a lot more going on in a game.

What’s long but a second ball devotion?

“Winning the second balls” is an idiom that is generally associated with managers of a certain vintage, largely because of its association with the long ball game and a bygone era. But they don’t really mean winning the second ball, specifically, or at least that’s not always where the pay off from long balls comes from. What is meant is gaining Meaningful Possession (either as I have defined it above, or some other denotation) within a reasonable timeframe of the long ball pass.

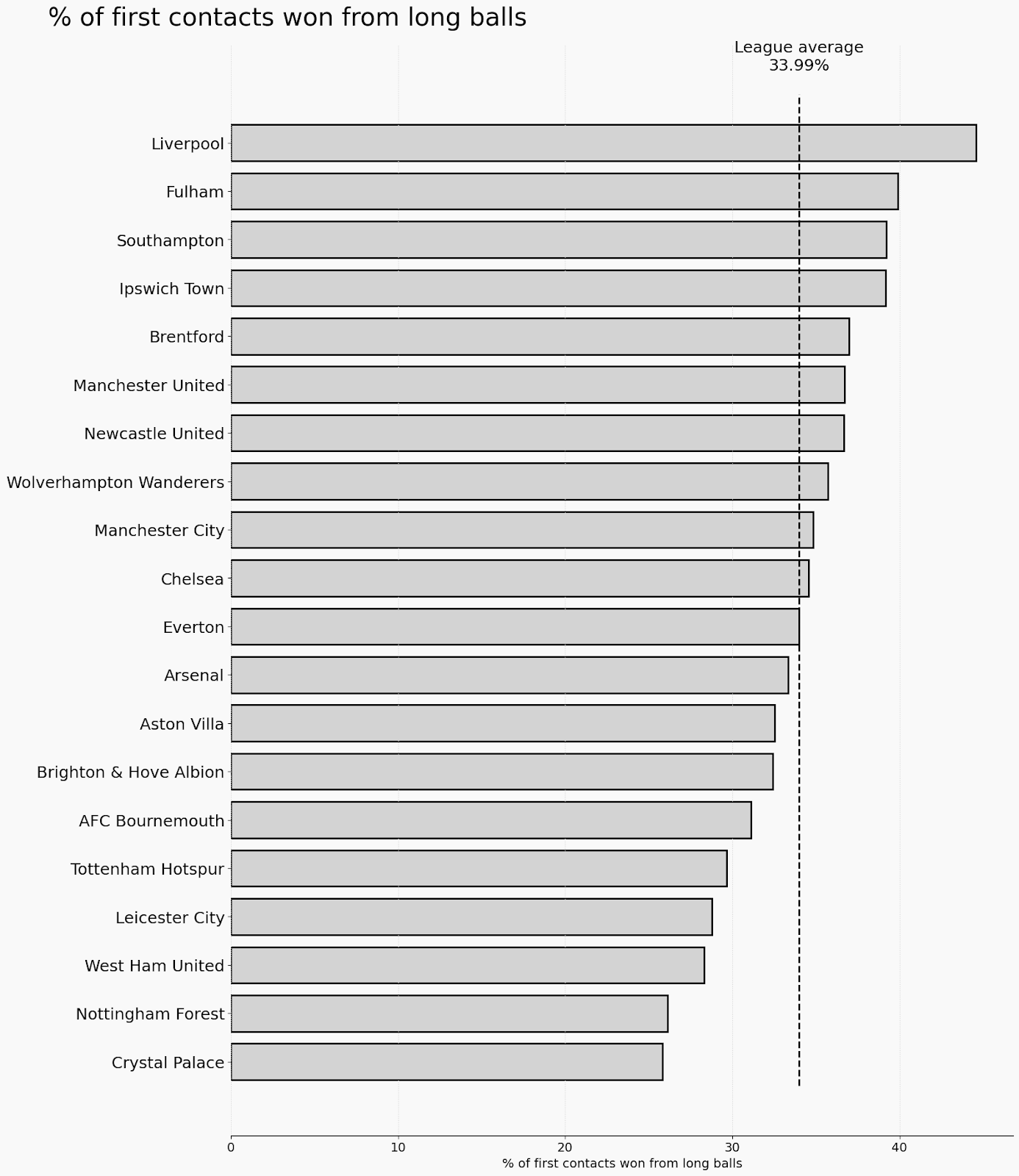

But let’s look at the first balls first. When a ball is played long, how important is it that first contact is won? (Note that first contact here isn’t necessarily an aerial duel, some of these long balls will be into feet.)

In the Premier League last season (2023/24), around 63% of first contacts won resulted in Meaningful Possession. This season so far (2024/25), that number is ~64%. It naturally varies from competition to competition, but generally it falls in the range of ~55% to ~65% for most of the recent seasons across the Big 5 European leagues plus the English Championship.

When first contact is not won, Meaningful Possession retained drops to ~10%.

Clearly, winning the first contact is hugely important. But it’s also not the golden ticket… even when a first contact is won, on average, teams are not acquiring Meaningful Possession around 40% of the time. Second balls are indeed important, and almost just as much as first balls. I guess maybe the luddites knew a thing or two about the game after all.

So, if we hypothesise that Liverpool are the gold standard here, then it should stand to reason that they are good at winning the first contact from long balls, right? Correct.

Liverpool win first contacts on Long Balls at a rate of 44%, compared to the league average of 34%. By now you’ll likely be starting to wrestle with the notion that a Long Ball can look very different for different teams, and that it’s not always a hoof up to a big number 9 as perhaps is sometimes surmised when the term is first mooted. Maybe the term Long Pass would be more appropriate, but more on that later.

Moving on to the second balls, this is where we can really start to paint ourselves a picture of what differentiates some teams through the Long Ball lens.

Not only do Liverpool win a lot of first contacts on their long balls, but they also acquire meaningful possession at a notably above average rate for the league both when first contact is won and also when it isn’t.

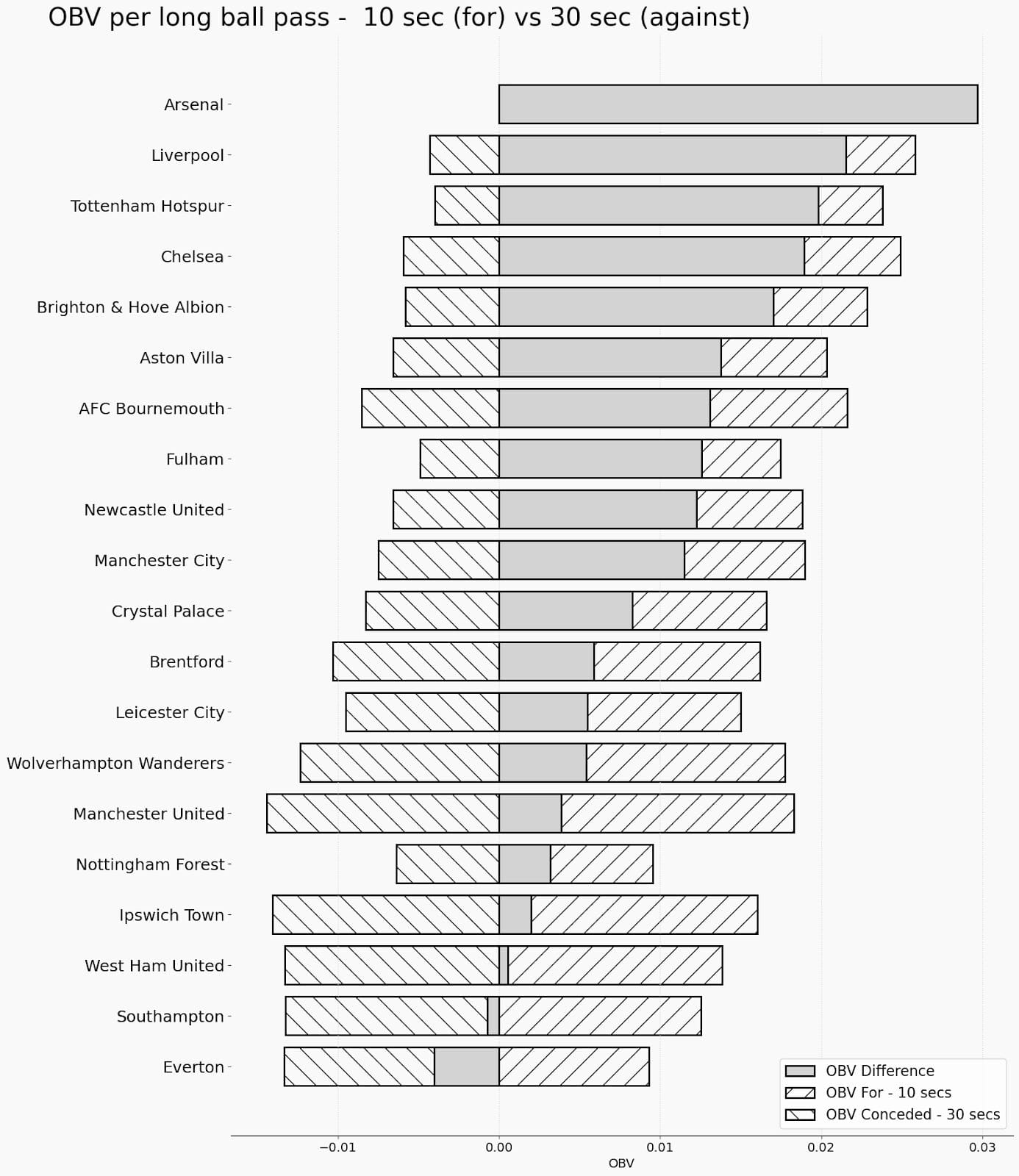

Who needs a transition when a transition can be conceded?

As I alluded to in the opening gambit of this piece, decisions taken and actions carried out on a football pitch aren’t always purely with the intent of increasing your own team’s chances of scoring. And perhaps that's particularly relevant in the case of long balls, where moving the ball to the final third of the pitch gains significant territory and gives some respite to your defence. Or at least that is the theory.

We can get a proxy towards measuring this pay off by calculating the OBV Difference (i.e. OBV For minus OBV Conceded) in the phases after the long ball.

Here I’ve used the 10 second period after the long ball to measure OBV For - keeping it consistent with our Meaningful Possession definition - and opted for the 30 second period after the long ball to measure OBV Conceded - allowing a reasonable amount of time for play to shift from one end of the pitch to the other.

Admittedly using 30 seconds as the cut off point is a little subjective, however, when calculations are run for slightly different timeframes, the ordering of the teams below remain largely the same.

The results are an indication of the offensive effectiveness of long balls, relative to how well teams are setting up in behind the long ball so as to avoid having pressure coming back on them in the immediate aftermath.

So we have Arsenal at the top of the pile - they create the most threat going forwards, and in fact also force their opposition into a net negative in the subsequent 30 seconds - followed by Liverpool.

Other notable observations include;

- Bournemouth, who despite scoring lowly for meaningful possession are in the upper echelons of the league for threat created and don’t give up too much coming back the other way. Being the best ranked team in the league for Pressure Regains certainly helps here

- West Ham and Southampton who essentially net out anything they gain by giving it up in the opposite direction (at least in the case of Southampton we know it’s not a tactic they deploy often)

- Manchester United with the worst OBV Conceded per pass - a validation of sorts for this metric, given how poorly organised they’ve looked behind the ball at times this season

- Everton, who are the only team in the league with a discernible deficit on this metric - translated as they don’t generate much threat from playing the ball long, and are giving up a chunk when it comes back at them.

But whatever the reason…

Now that we have a casual awareness of who is good and who is bad at long balls, let’s try to get a grasp of why that might be.

Understanding a little more about what teams are doing with the ball when they acquire Meaningful Possession offers some indicators. The below shows how many Passes, Shots and Carries each team makes, on average, in the 10 second period after a long ball, with the results normalised against the league average.

- Arsenal (0.08 shots per Long Ball Pass) and Liverpool (0.34 Passes and 0.36 Carries per Long Ball pass) pop for slightly different reasons, but are each way above the league average for two of the three measurements

- Everton are notably below average on shots generated and ball carries

- Bournemouth are at least around the league average for shots generated - which might explain part of the reason why they outperform Everton so dramatically in the OBV differential, despite being similar for meaningful possession. Getting your shots off matters.

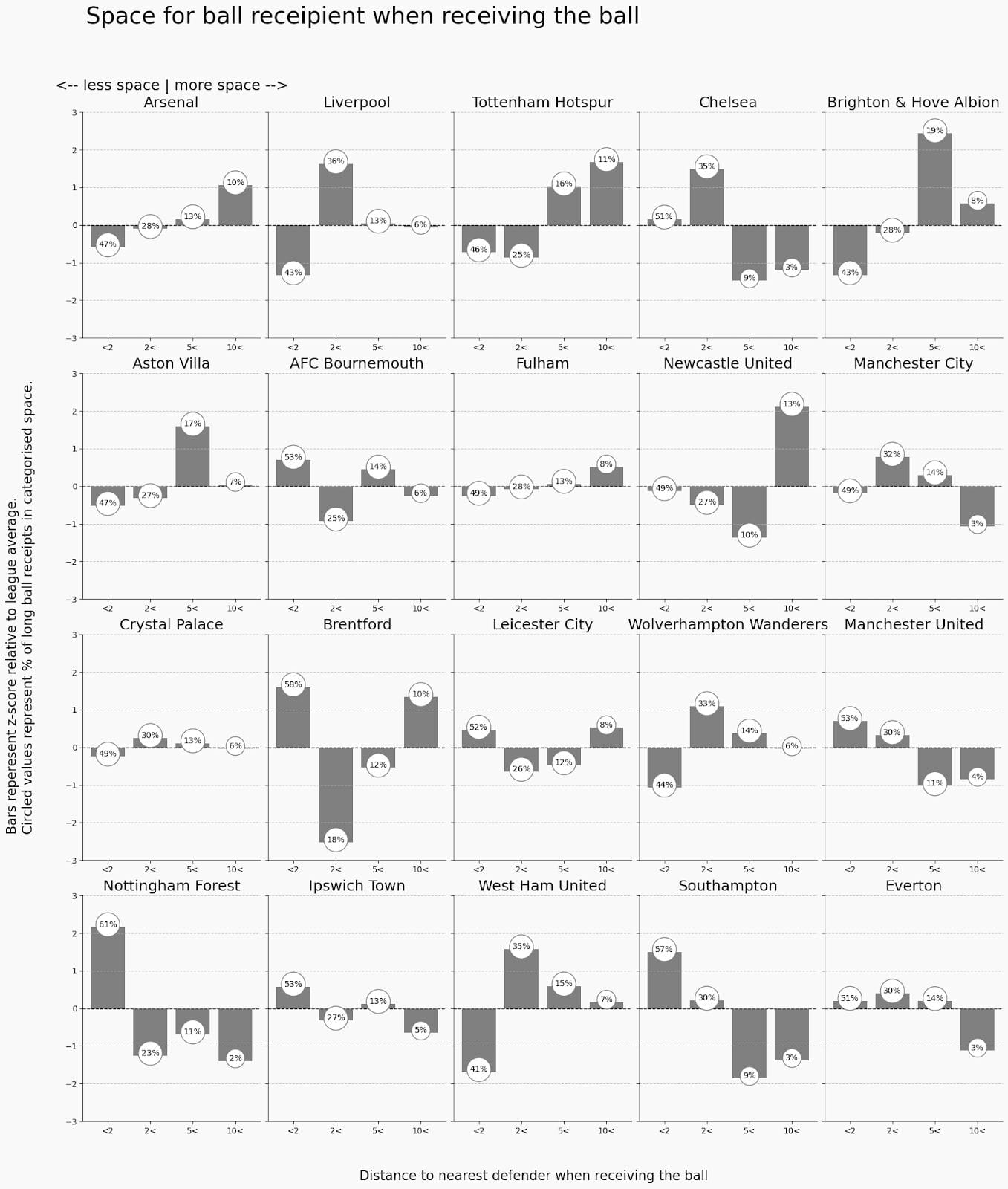

Next, let’s take a closer look at the circumstances in which players for each team are receiving the ball. To do this we can use information on the whereabouts of the nearest defender to the ball recipient, as a proxy for the time and space they will have on the ball.

Again we can see reasons why Arsenal and Liverpool are leading the way - notably below average for percentage of ball receipts in less than 2m space (47% and 43% respectively), and above average or at average on gauges for more space (10% of Arsenal’s Long Balls are received by a player in 10 yards or more space).

This also shines some light on why Spurs, Brighton and Villa perform well - each of them being substantially above average for the percentage of times players receive the ball in greater than 5m and greater than 10m of space. Chelsea remain a bit of a *shrug* at this point.

What about where on the pitch these long balls are delivered to, I hear you ask…

I was anticipating something a little more revealing; I expected some correlation between success and the volume of balls played into wide areas - on the assumption that playing into more congested, central areas would make it more difficult to win first contact.

Perhaps there is something in the better teams being more varied in their approaches, less predictable. But maybe, coupled with the below, the absence of any obvious pattern is the real takeaway here.

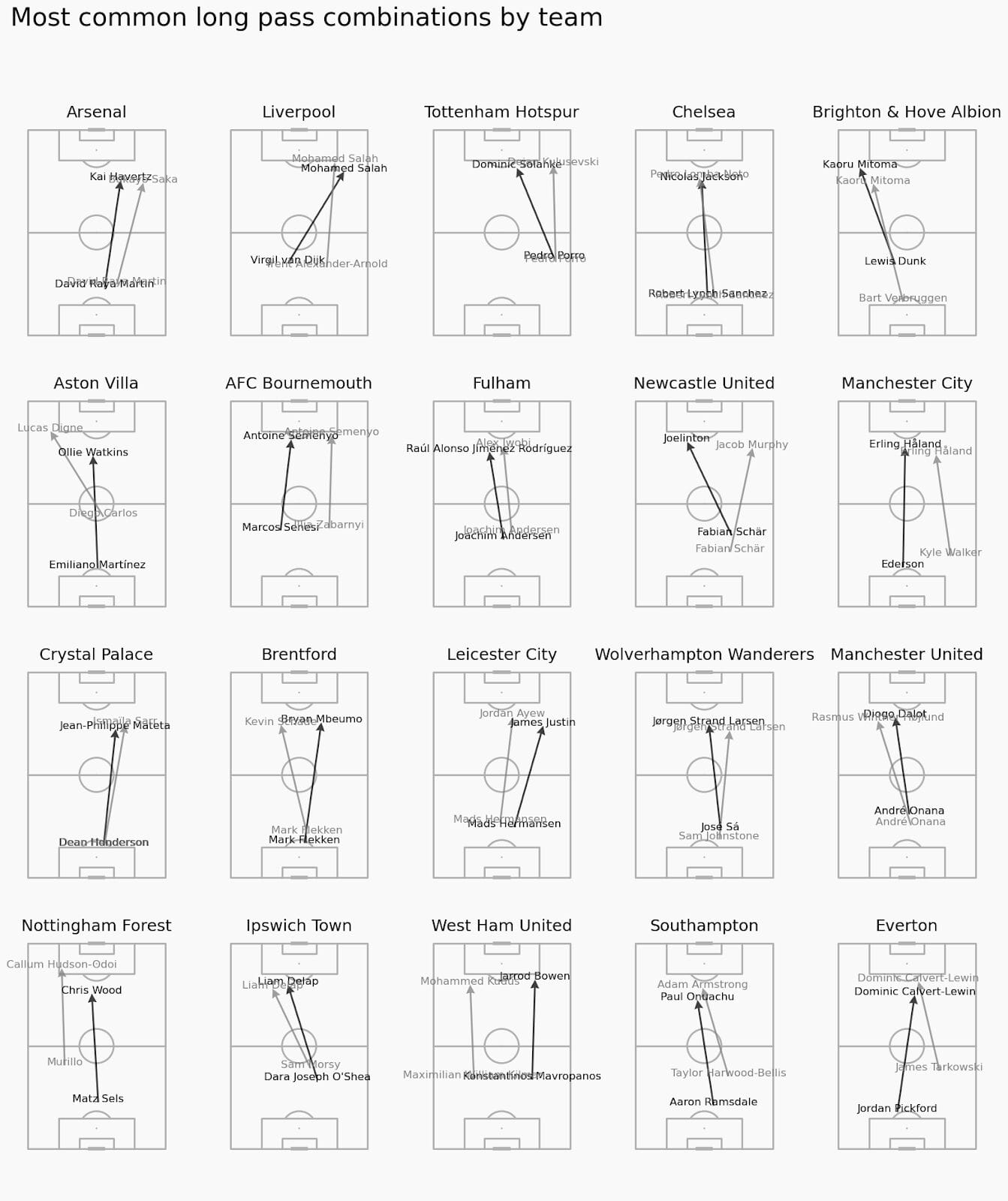

A closer inspection of the types of passes being played and the personnel involved for each team does reveal some insight. So perhaps it’s not the where, but the who and the how, that matters.

The majority of teams toward the top end of the spectrum are playing either a diagonal ball, or one up the touchline (Liverpool notably do both), whereas those at the other end of the scale are playing a lot of vertical passes up the gut of the opposition.

There’s also something to be said about the types of players that are getting on the end of the passes. At the top end you’ve got the likes of Salah, Saka, Mitoma and Semenyo (another nod to what differentiates Bournemouth from Everton), all dribbly-ball-carrier player types, then at the lower end of the spectrum you’ve the likes of Calvert-Lewin, Adam Armstrong, Chris Wood and Højlund certainly not dribbly-ball-carriers.

Having a Trent or Van Dijk to play those passes also helps.

Which is also a nod to the variety of Long Ball types that we talked about earlier… Saka, Salah, etc aren’t going up and winning a lot of these long balls in the air, Calvert-Lewin et al most likely are. Long Passes definitely feels like a more appropriate term to use.

I do it for Long

When I first started poking at long balls in the data, I wasn’t expecting to find anything revolutionary, but had hoped it would lead me down some potentially interesting rabbit holes. And I think that’s pretty much where I’ve landed.

We’ve concluded that winning the first contact from a long ball is extremely important, but then so is winning the second ball.

Generating shots, passes and ball carries at an above average rate helps, as does delivering the ball to teammates in space. Nothing revolutionary there.

Play it to wide areas or central areas, it doesn’t really matter. But do try and avoid vertical passes into central areas, and it helps if you can get a dribbly-ball-carrier on the end of your passes.

As I noted early on in the piece, with even the most direct teams in the Premier League only playing long balls around 6% of the time, they aren’t necessarily a definitive aspect of the game. Forest being the worst performers by measure of Meaningful Possession acquired from long balls, yet sitting pretty in the top 4 of the league table is testament to that.

We also have Arsenal and Liverpool as the two top performers by OBV Difference, yet neither team would, by any measure, be described as a long ball team. Given that we are talking about probably the best two teams in the league (by most unbiased subjective opinions and many objective measurements) it highlights that to be successful in the modern game, it helps to be multifaceted. And not only are they the top two sides for creating threat from Long Balls, they’re also amongst the best for abating the opposition if the ball comes back in the opposite direction.

And what of Sean Dyche’s Everton? A team that have opted to play it long more often than any other side in the Premier League (both in terms of raw volume and when adjusted to percentage of total passes), but had the worst OBV Differential per long ball pass - creating the lowest OBV For and conceding the 3rd highest OBV Against. There are many ways to skin a cat, but if you’re going to use a knife then at least make sure the knife is sharp.

Long balls are undoubtedly less common in elite football than they were in the past. But they aren’t going anywhere, either as a means to clear your lines and reset your shape, or a direct attempt to try to create a goal for yourself. And if you’re going to be a good team, then being good at even the unfashionable aspects of the game will help.