Earlier this year, on our Spanish website, I analysed sequences of play in La Liga in which a line-breaking pass was immediately followed by another progressive action, be that a pass or a carry. I was intrigued by the idea of line-breaking passes acting as an accelerator for an attack, and wanted to see how often that was the case and how much it varied by team.

That analysis produced some clear profiles that were more or less replicated when I had a look at the numbers for the Premier League. But in playing around with the code across some other competitions, I came across some interesting quirks in one particular league that seemed worthy of further analysis. That league was the Bundesliga.

Firstly, there were significantly less line-breaking passes in the Bundesliga last season than in either La Liga or the Premier League. The team average in those leagues was 40 or more completed line-breaking passes per match; in the Bundesliga, it was less than 25.

Secondly, there were no examples of teams who both completed a high number of line-breaking passes and also converted a good percentage of those into subsequent progressive actions. A profile that encompassed teams like Arsenal, Barcelona, Chelsea, Liverpool and Real Madrid just didn’t exist in the Bundesliga.

Finally, the focus of this analysis: the evident differences between the league’s top-three finishers, Bayer Leverkusen, VfB Stuttgart and Bayern Munich, despite some clear similarities in their other passing and territorial data.

Before we get into the analysis, some quick definitions:

- Line-breaking pass: completed passes that advance the ball at least 10% closer to the opposition goal and that intersect a pair of defenders in close proximity (x-axis) or pass behind the defensive line (y-axis)

- Progressive action: a pass or carry that advances the ball at least 25% closer to the opposition goal

Okay, we begin:

Immediately, we can see that the top three teams each used line-breaking passes in very different ways. From left to right on the graph:

- VfB Stuttgart: high number of line-breaking passes; few subsequent progressive actions

- Bayer Leverkusen: high number of line-breaking passes; average proportion of subsequent progressive actions

- Bayern Munich: average number of line-breaking passes; league-high percentage of subsequent progressive actions

In a league in which the large majority of teams are clustered in one corner of the graph, those three (and FC Köln) really stand out.

If we break the numbers down by pitch zones, we can get a clearer idea of the differences between them:

Stuttgart hovered around or below their pitch-wide average of 9.7% in the large majority of the first two-thirds of the pitch. That chimes with their overall profile that sits somewhere between those of Brighton and Las Palmas as teams who, at times, and to varying degrees, use possession as a form of control more than as a means of advancing the ball into attacking areas. Teams who even when they break a line are content to recycle possession and start over if they don’t fancy the risk/reward ratio of a subsequent forward option.

They did, though, come alive a bit along the attacking midfield line, with Chris Führich and Deniz Undav amongst the most regular ball progressors from that zone after receiving a line-breaking pass.

It is also worth noting that while Stuttgart were one of the Bundesliga teams who least often combined a line-breaking pass with a subsequent progressive action on a proportional basis, in absolute terms they were third to only Leverkusen and Bayern. And they were also third to those same two teams in terms of shots, goals and expected goals (xG) generated from possessions that included one of these line-breaking pass to progressive action chains.

It appears to have been a stylistic choice by coach Sebastian Hoeneß rather than a weakness in their approach.

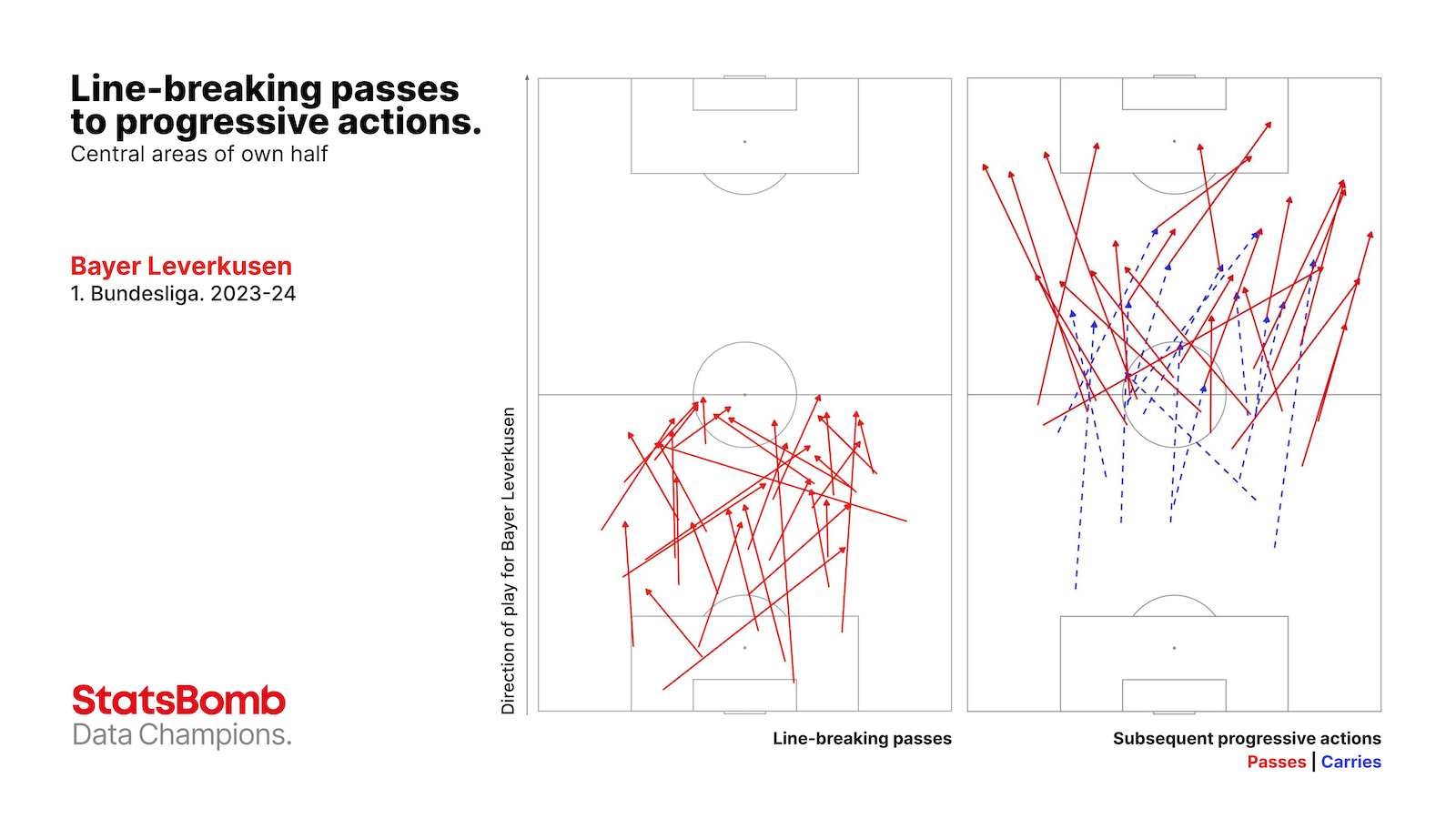

The first thing that stands out about Xabi Alonso’s champion Bayer Leverkusen side is their ability to progress the ball after breaking lines in central areas of their own half. They lured opponents in with short passing from the back, broke the first line and then accelerated upfield.

Note: this graphic only plots subsequent progressive actions: carries, passes and progressive carries immediately followed by a progressive pass. Any carries between receiving the ball and making a pass that aren’t classified as progressive are not included, so line-breaking pass end locations and subsequent action start points won’t always line up perfectly.

Eleven of these actions were part of possessions that led to shots; five of them resulted in goals.

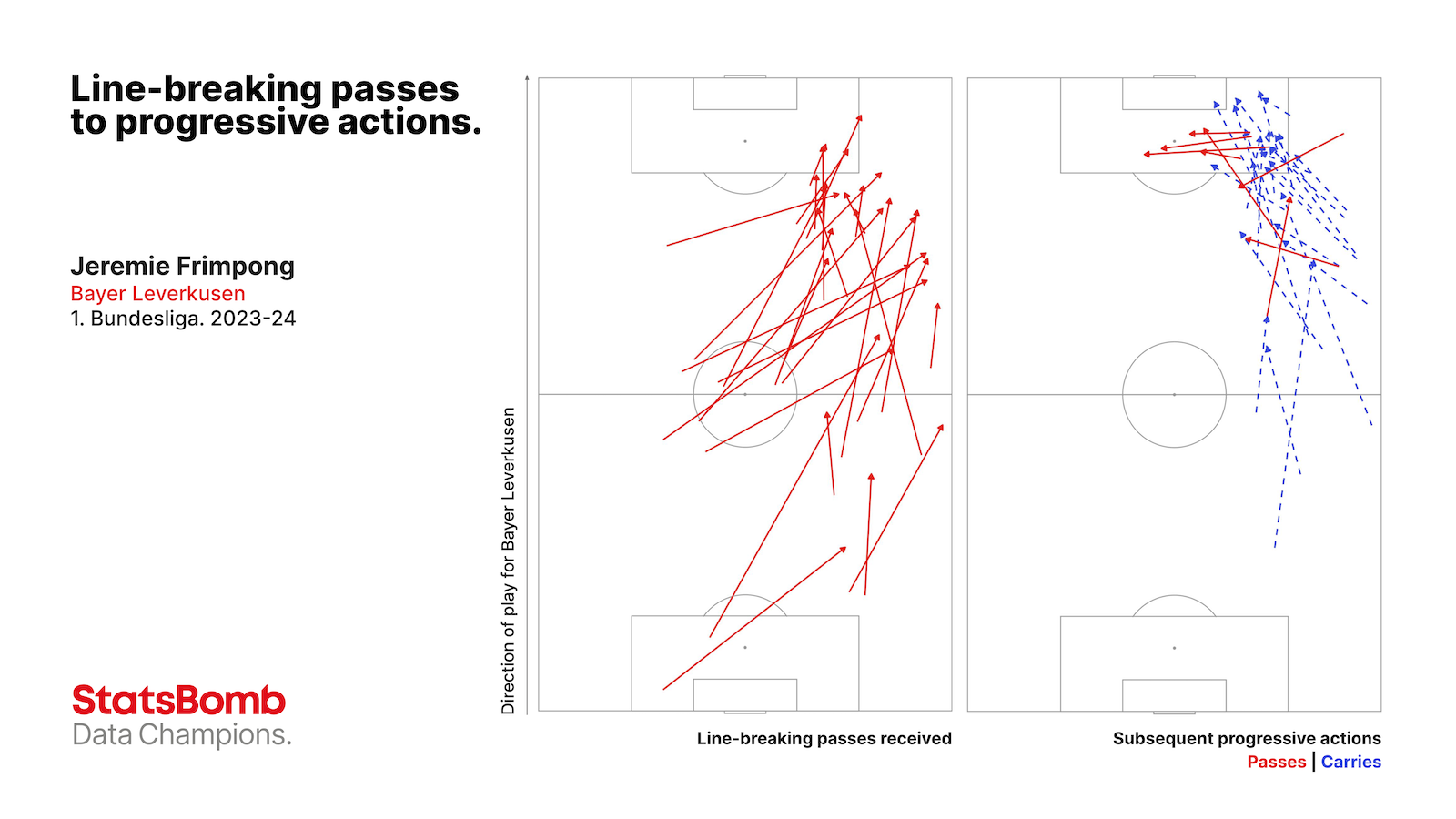

Further upfield, the right flank was clearly a zone from which Leverkusen were easily able to progress the ball after breaking an opposition line.

Florian Wirtz popped up there on occasion, but it was primarily the preserve of Jeremie Frimpong, the right wing-back. Overall, Frimpong was by far the most vertical of Leverkusen’s players after receiving a line-breaking pass, producing a subsequent progressive action 26% of the time.

Leverkusen weren’t able to progress through the central areas of the attacking half as easily but that wasn’t a major impediment to creating danger. The sheer volume of line-breaking passes they were able to complete in those high-value central areas meant that although proportionally they weren’t able to advance as often as other teams, in absolute terms no team did so more often: 78 times.

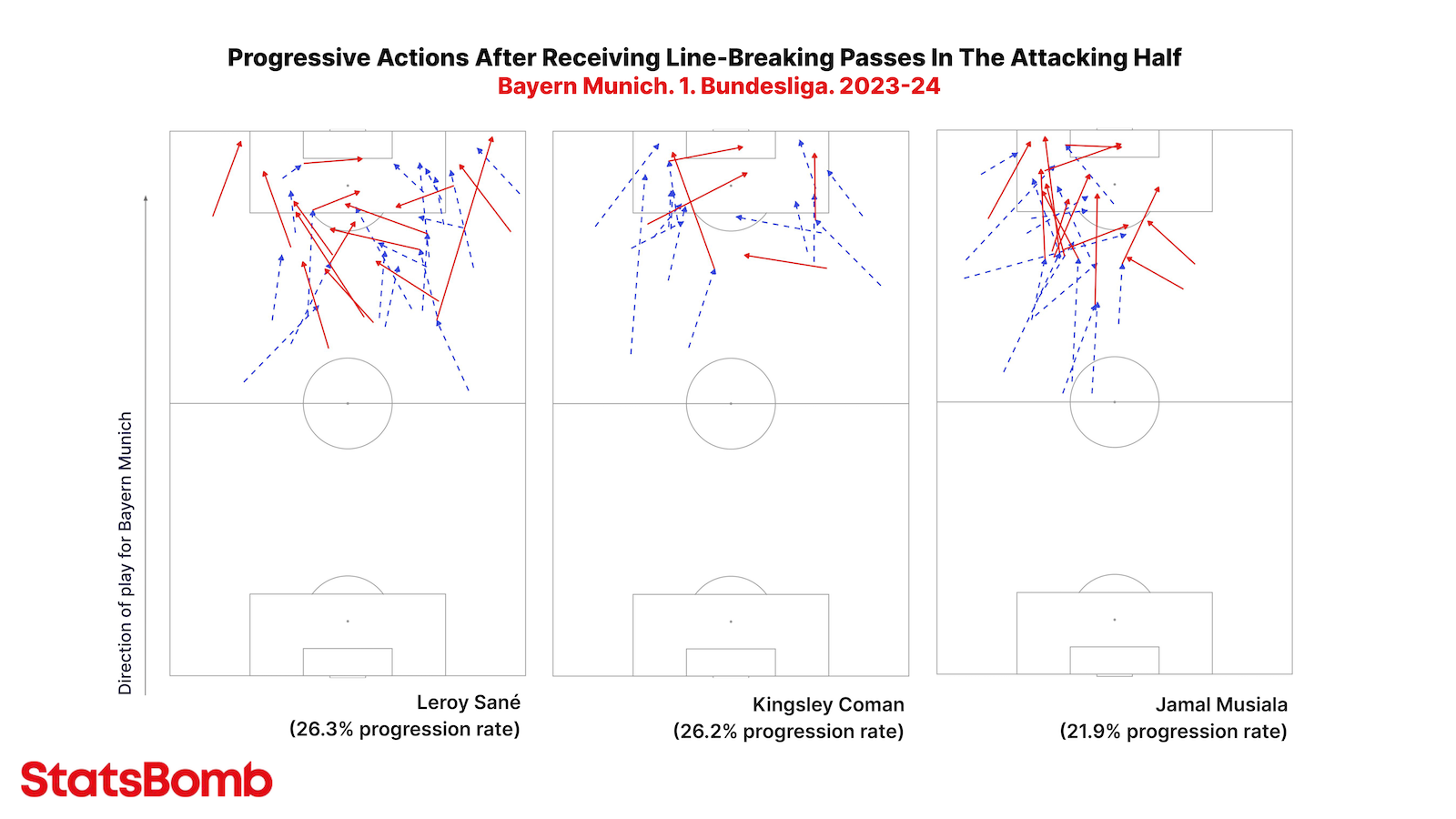

That Bayern Munich had only four less of those subsequent progressions despite completing less than half as many line-breaking passes to the zone (333 vs. 756) gives an indication of just how vertical they were there after breaking an opposition line. In those central attacking areas, over 22% of their line-breaking passes were followed by a subsequent progressive action, three percentage points more than any other team.

Kingsley Coman, Leroy Sané and Jamal Musiala were the main ball progressors from the zone, something that also extended across the entire attacking half, where Bayern were once again the team who most often chained a line-breaking pass with a subsequent progressive action: 19.5% of the time.

Those three players, all quick and vertical, were key to Thomas Tuchel’s team converting a low line-breaking pass volume into a high number of subsequent progressive actions and dangerous attacks. While Leverkusen were the team who scored most goals, 20, from possessions featuring a line-breaking pass to progressive action chain, Bayern were the team who generated most shots (84) and xG (16.39), and they also scored a league-second-best 14 goals.

Leverkusen, Bayern and Stuttgart were not only the top three teams in the Bundesliga last season, but also those with most possession, the best pass completion rates and the most final-third and box entries. That is to say, the league’s dominant teams in both ball and territory.

It was, therefore, surprising to see such differences between them in terms of these line-breaking pass to progressive action chains, differences that have hopefully helped to elucidate some of the subtleties of their respective styles and open up pathways for future analysis.