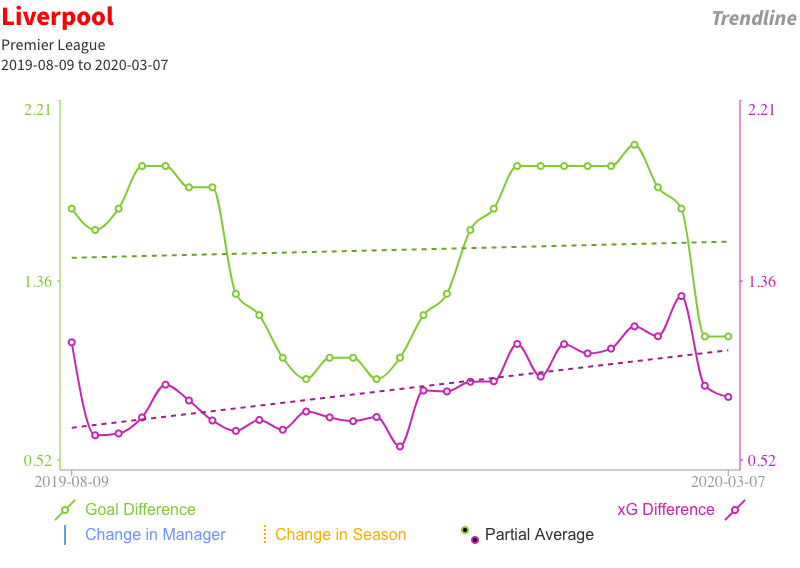

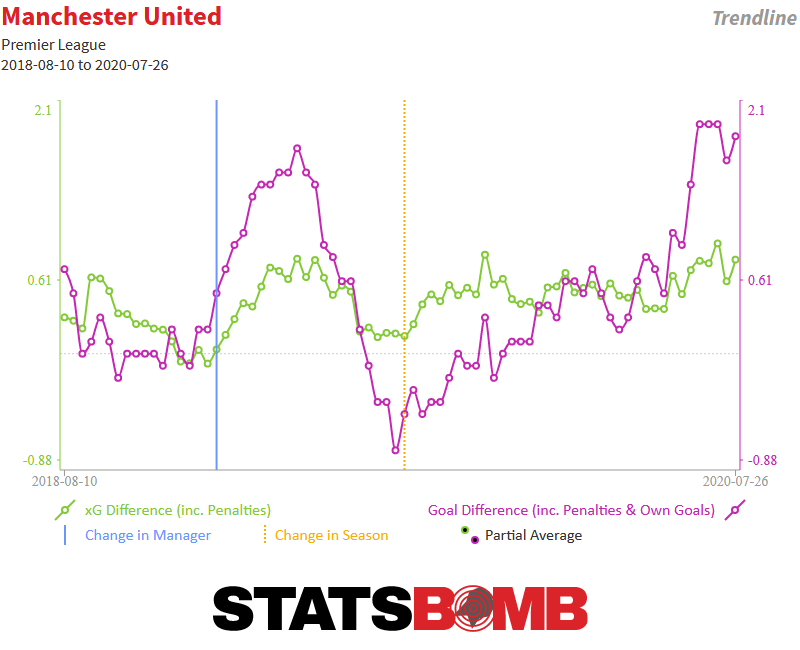

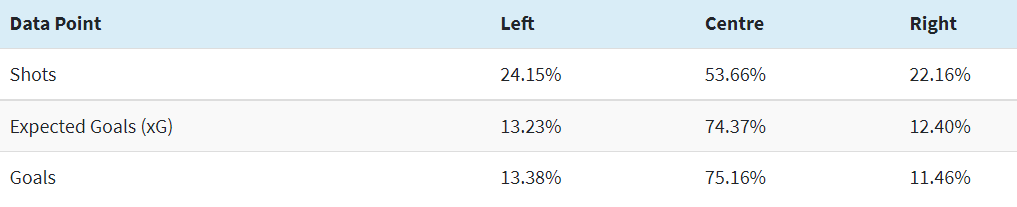

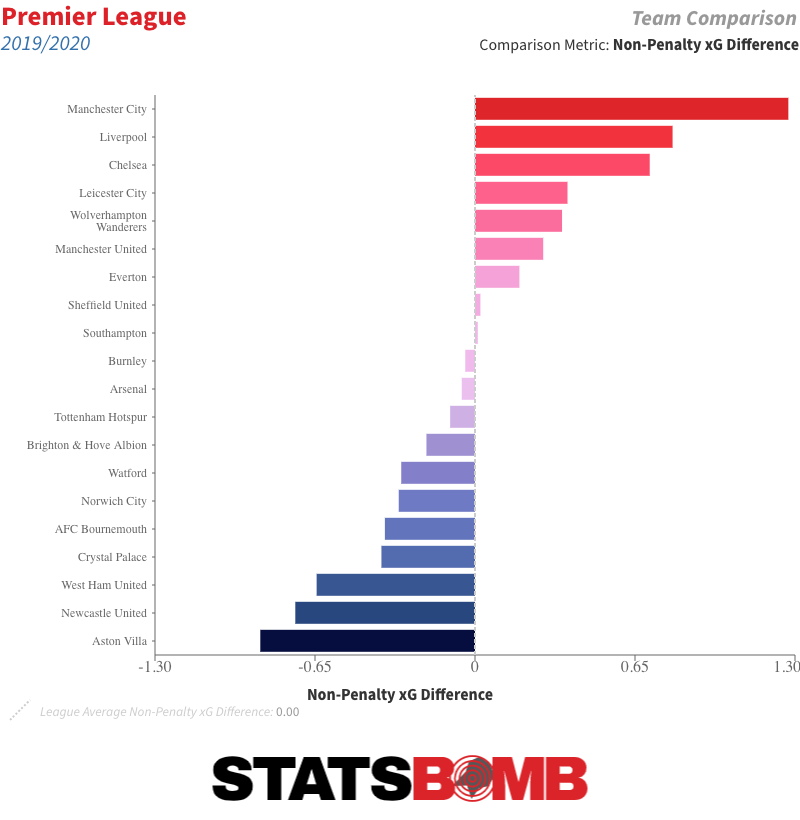

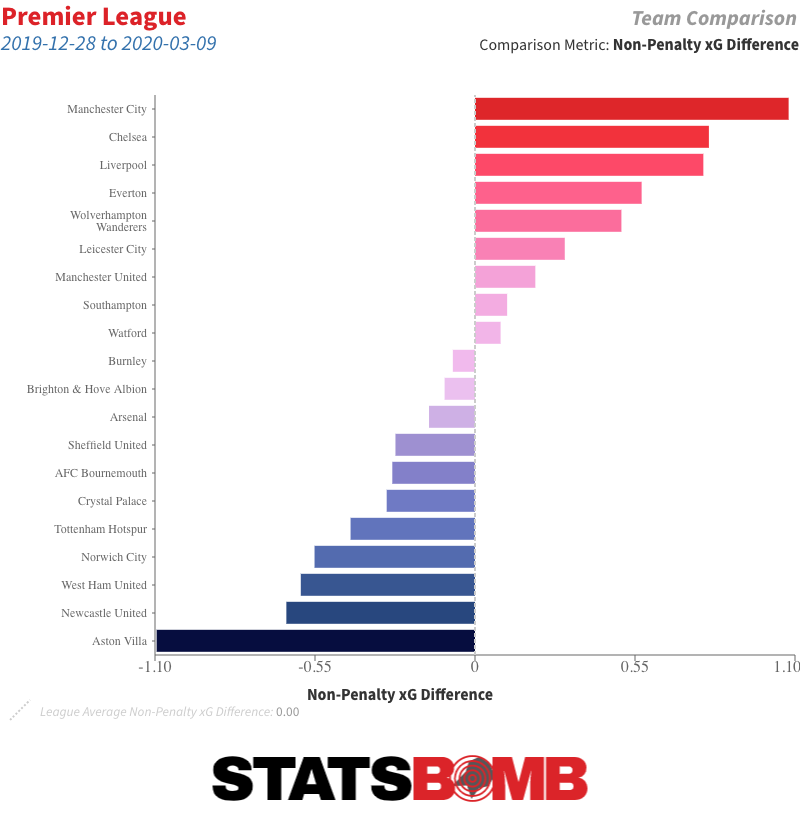

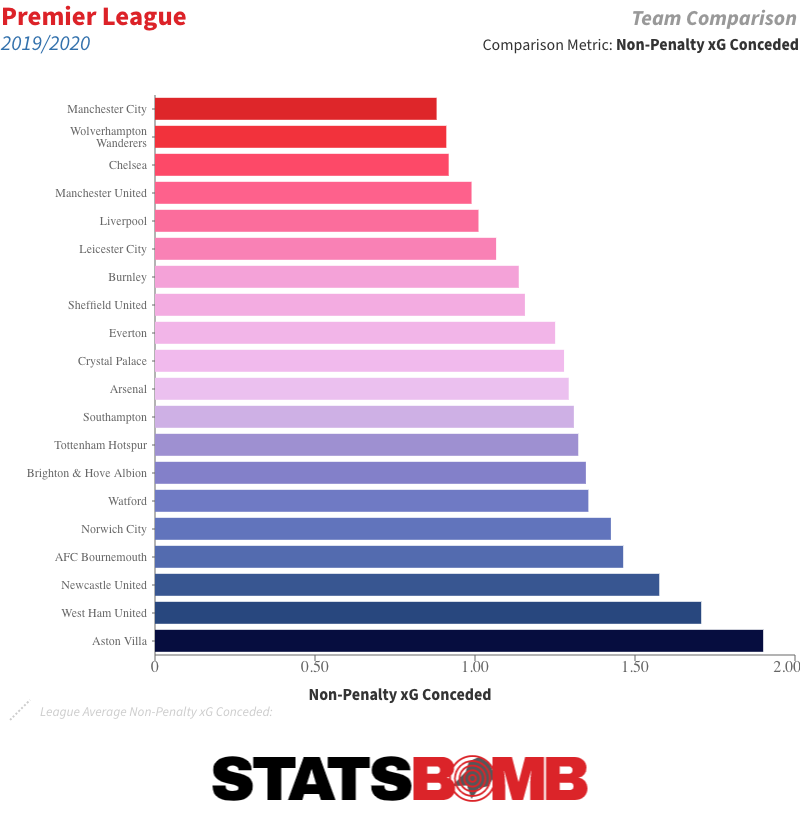

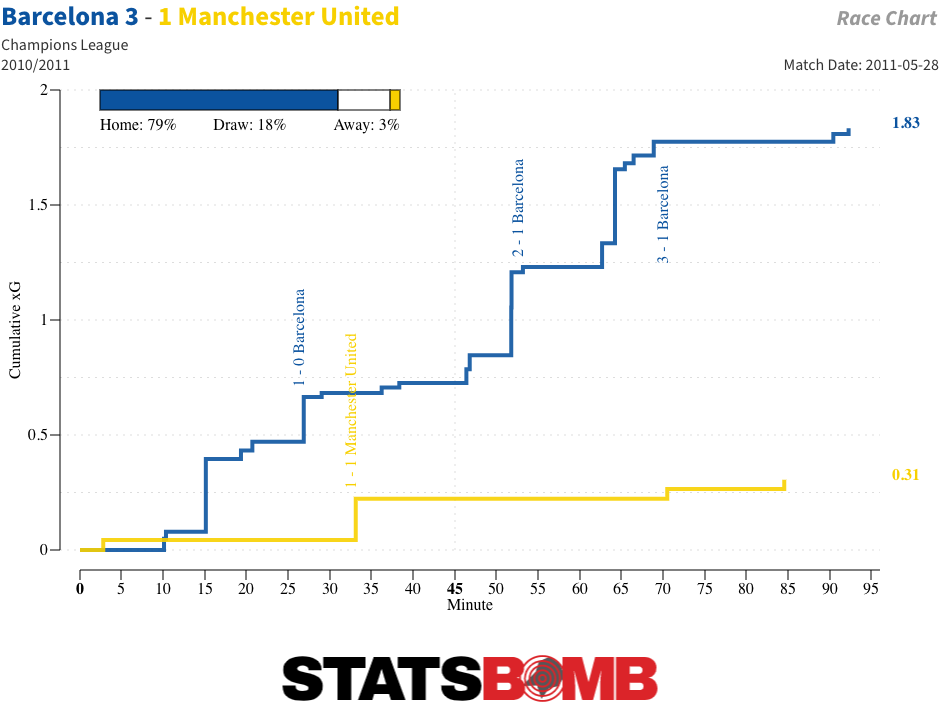

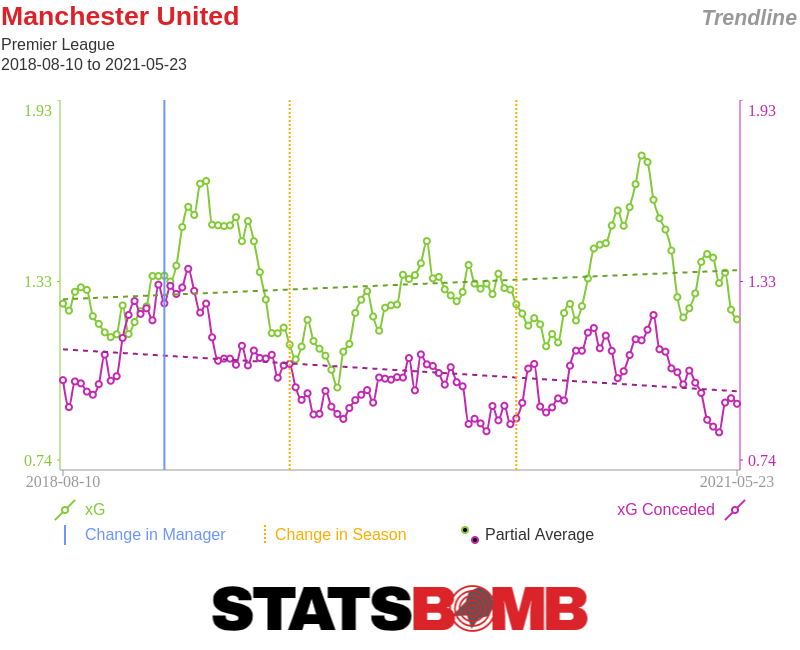

Are the good times back? Ole Gunnar Solskjær is closing in on two years in the Manchester United hotseat and there’s a creeping realisation that the longer he’s been there the better things have got. That’s not to say that the journey to this point has been smooth or linear, or that the actual tangible on-pitch improvement is impossible to deny. It’s more subtle than that. When United are good, they can be very good. On paper, they have an array of attacking talent that few can match in Anthony Martial, Bruno Fernandes, Paul Pogba, Marcus Rashford and now Mason Greenwood. In defence, they were only a clip behind Liverpool and Manchester City last season and their expected metrics there were very solid. The recruitment of Fernandes in late January became a clear stake in the ground. While significantly more erratic prior to his arrival, United were unbeaten in the league from that moment onwards (fourteen games) and only lost their first match since his arrival at the club in the FA Cup semi-final in July against Chelsea. The familiar sight of Fernandes finishing a penalty occurred seven times in his first few months at the club, his technique and cool head benefiting from a team that won spot kicks at a high pace throughout the season, often thanks to the slaloming skills of Rashford, Pogba and others. But the first half of the season was less encouraging, with an odd mix of good results against strong teams and bad results against weaker sides. The consistent later form coincided with a more stable first eleven, and a kind post-Covid fixture list was the perfect environment for Pogba to return to and for Greenwood to show a finishing run exceeding that of Rashford’s own emergence four years ago. One of the odd characteristics of Solskjær's reign is how metrics and outcomes have deviated so wildly. It seemed illogical to exclude penalties from this chart (just this once!) since they were such a feature of the 2019-20 season, but it shows expected goal difference and actual goal difference across his whole tenure and how rarely the twain shall meet:  Translation? Expected metrics have slowly crept upwards over time, kinda, actual goal outcomes look more like a heart monitor. This tendency towards wild deviations has actually caused narratives to become slightly faulty. The blast of finishing and run of penalties while Fernandes has been at the club gives the impression that United's attack is their strength, when actually the opposite is likely true--the defence is their bedrock and has been for some while:

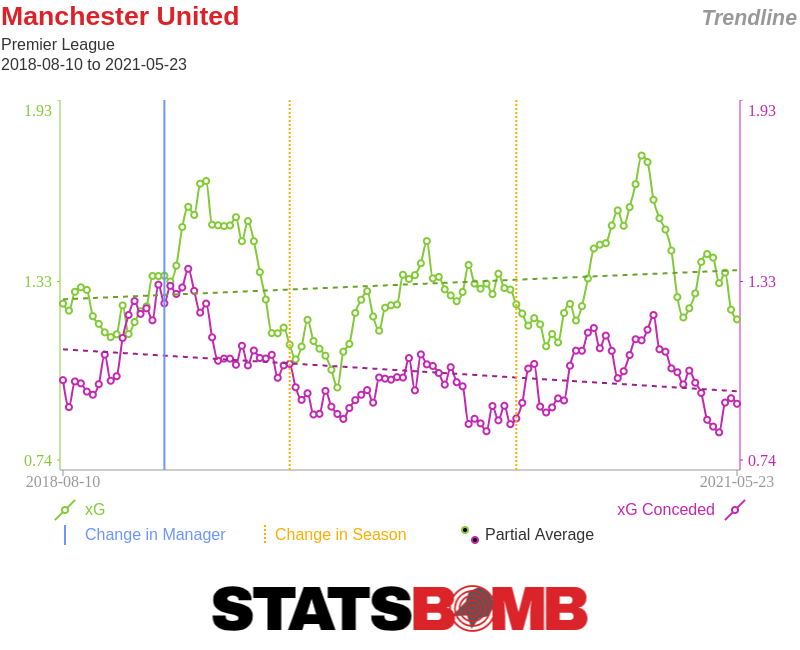

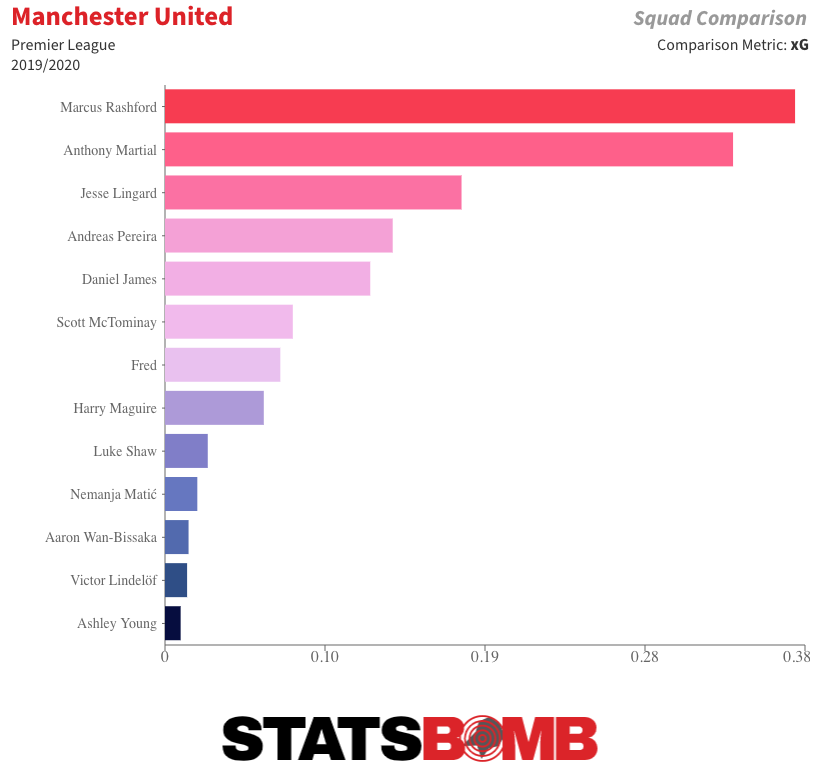

Translation? Expected metrics have slowly crept upwards over time, kinda, actual goal outcomes look more like a heart monitor. This tendency towards wild deviations has actually caused narratives to become slightly faulty. The blast of finishing and run of penalties while Fernandes has been at the club gives the impression that United's attack is their strength, when actually the opposite is likely true--the defence is their bedrock and has been for some while:  A season long expected goal against value of around 0.9 per game is in the ballpark of their rivals--including Manchester City and Liverpool. A season long expected goal for value of 1.3 per game parks then between Southampton and Everton. If this team has designs of winning enough games to point upwards out of the island of third to fourth, it will first and foremost need to get better in attack. How can this be achieved? The front five United fielded during their unbeaten run are a blend of dual purpose longer range shooters and creators (Pogba and Fernandes), shooters (Rashford and Greenwood) and a player with long term finishing prowess who has seen creativity drop off as he's been empowered into a centre forward role (Martial). It's likely that carrying Rashford, Greenwood and Martial (in this role) damages the ability for this team to create a high volume of chances. As we saw towards the end of the season, if Fernandes is quiet, United can really drift and lack incisive creativity. The depth in this area of the pitch is not ideal too with the likes of Jesse Lingard, Juan Mata or Andreas Pereira more sporadic and limited influences. The ship has sailed, but ironically, the profile provided by Alexis Sánchez, or at least a younger more virile version of him, would fit well into this set-up. Somewhere, United's balance of shooting and creativity needs to skew towards the latter. It's what makes the [potential] signing of Donny van de Beek ostensibly curious, as it's quite hard to directly envisage which of United's current attackers or midfielders he will likely replace, or specifically how he'd fit into midfield given how little he tends to contribute towards general buildup. Of course, as more required depth, he's entirely fine, but there's not an obvious way to get Van de Beek into a starting lineup that include Martial, Rashford and Greenwood unless you're entirely throwing caution to the wind and giving midfield a complete pass. This then undermines your already solid defence and puts a heck of a lot onto Pogba and/or Fernandes. This isn't Garth Crooks' team of the week; the Matic/Fred role can't just be abandoned. But at least this problem exists. Yes, the squad needs more depth and the drop off should injury hit any key starter is severe but the outright Manchester United first XI nearly picks itself, something that hasn't always been the case in the post-Ferguson era. To be more generally positive though, in Greenwood and his breakthrough, another fine talent looks to have been unearthed but this has slightly deflected focus on the development of Rashford. Of the attacking unit, his form was perhaps the least impressive post-lockdown, but now in a more settled left sided position, on aggregate his progression is tangible:

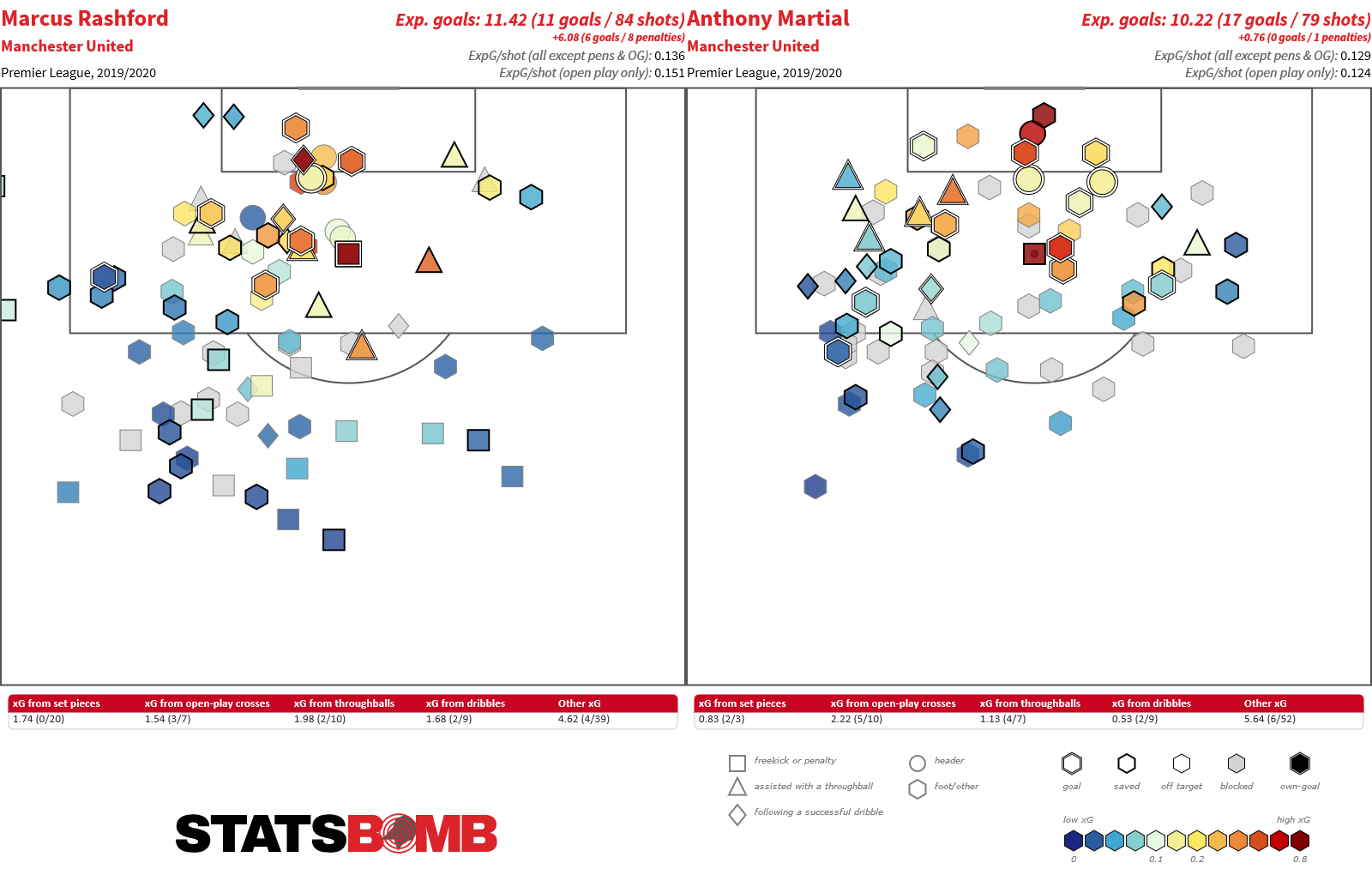

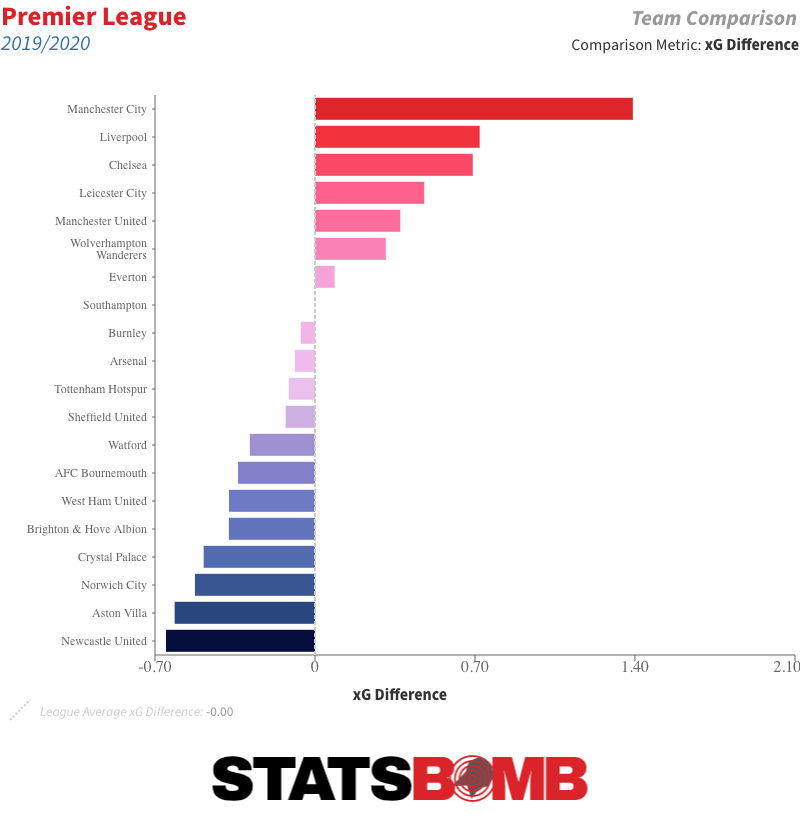

A season long expected goal against value of around 0.9 per game is in the ballpark of their rivals--including Manchester City and Liverpool. A season long expected goal for value of 1.3 per game parks then between Southampton and Everton. If this team has designs of winning enough games to point upwards out of the island of third to fourth, it will first and foremost need to get better in attack. How can this be achieved? The front five United fielded during their unbeaten run are a blend of dual purpose longer range shooters and creators (Pogba and Fernandes), shooters (Rashford and Greenwood) and a player with long term finishing prowess who has seen creativity drop off as he's been empowered into a centre forward role (Martial). It's likely that carrying Rashford, Greenwood and Martial (in this role) damages the ability for this team to create a high volume of chances. As we saw towards the end of the season, if Fernandes is quiet, United can really drift and lack incisive creativity. The depth in this area of the pitch is not ideal too with the likes of Jesse Lingard, Juan Mata or Andreas Pereira more sporadic and limited influences. The ship has sailed, but ironically, the profile provided by Alexis Sánchez, or at least a younger more virile version of him, would fit well into this set-up. Somewhere, United's balance of shooting and creativity needs to skew towards the latter. It's what makes the [potential] signing of Donny van de Beek ostensibly curious, as it's quite hard to directly envisage which of United's current attackers or midfielders he will likely replace, or specifically how he'd fit into midfield given how little he tends to contribute towards general buildup. Of course, as more required depth, he's entirely fine, but there's not an obvious way to get Van de Beek into a starting lineup that include Martial, Rashford and Greenwood unless you're entirely throwing caution to the wind and giving midfield a complete pass. This then undermines your already solid defence and puts a heck of a lot onto Pogba and/or Fernandes. This isn't Garth Crooks' team of the week; the Matic/Fred role can't just be abandoned. But at least this problem exists. Yes, the squad needs more depth and the drop off should injury hit any key starter is severe but the outright Manchester United first XI nearly picks itself, something that hasn't always been the case in the post-Ferguson era. To be more generally positive though, in Greenwood and his breakthrough, another fine talent looks to have been unearthed but this has slightly deflected focus on the development of Rashford. Of the attacking unit, his form was perhaps the least impressive post-lockdown, but now in a more settled left sided position, on aggregate his progression is tangible:  He still likes a dip from range, but has shown ever greater ability to get into good quality finishing positions, and at 22 years old, can't be far off the finished article as a player. Martial too appeared to prosper given the centre forward position. His 17 goals from an expected 10 was a welcome boost, but only continues a theme: few players are over their xG every season, but he has been for his entire time at United, albeit not to this degree before:

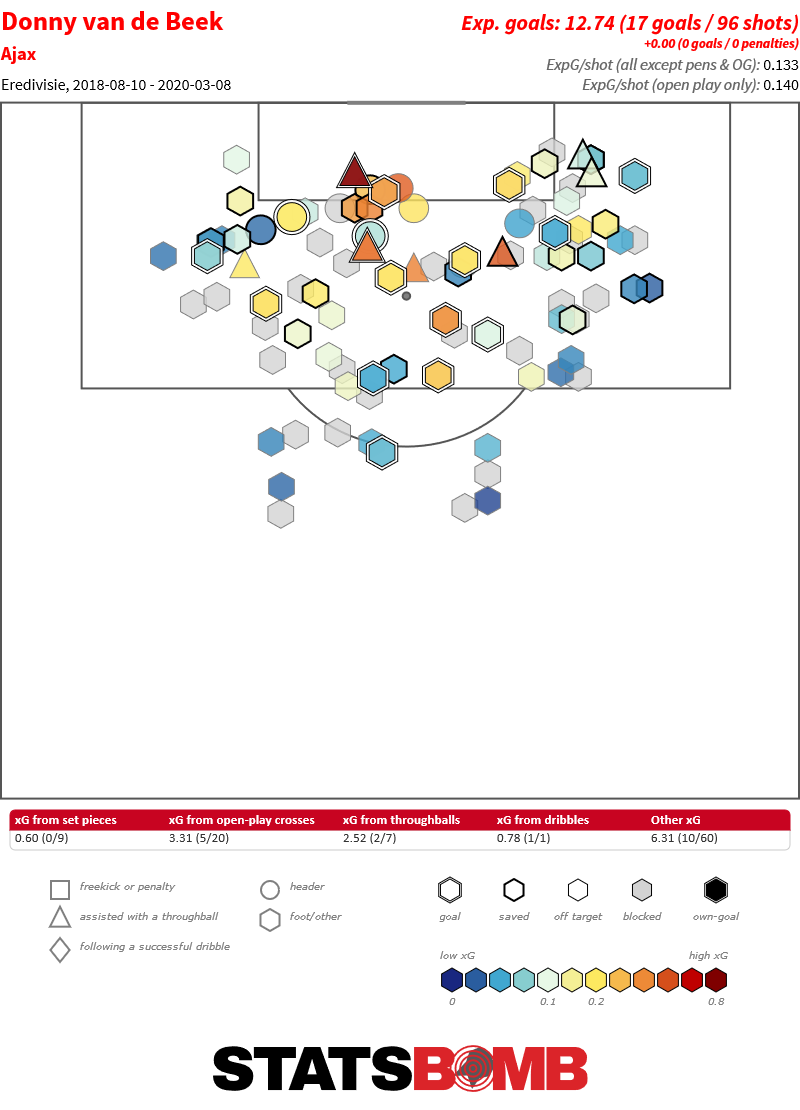

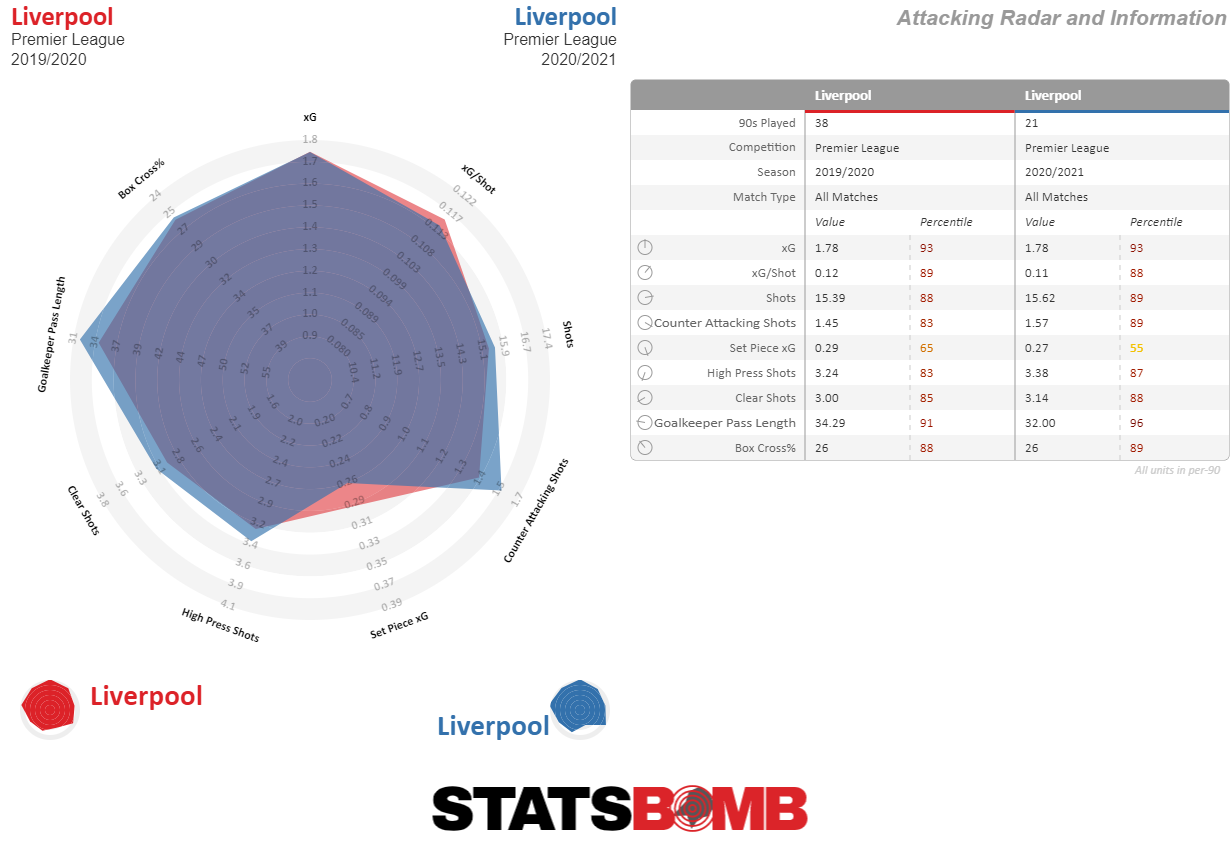

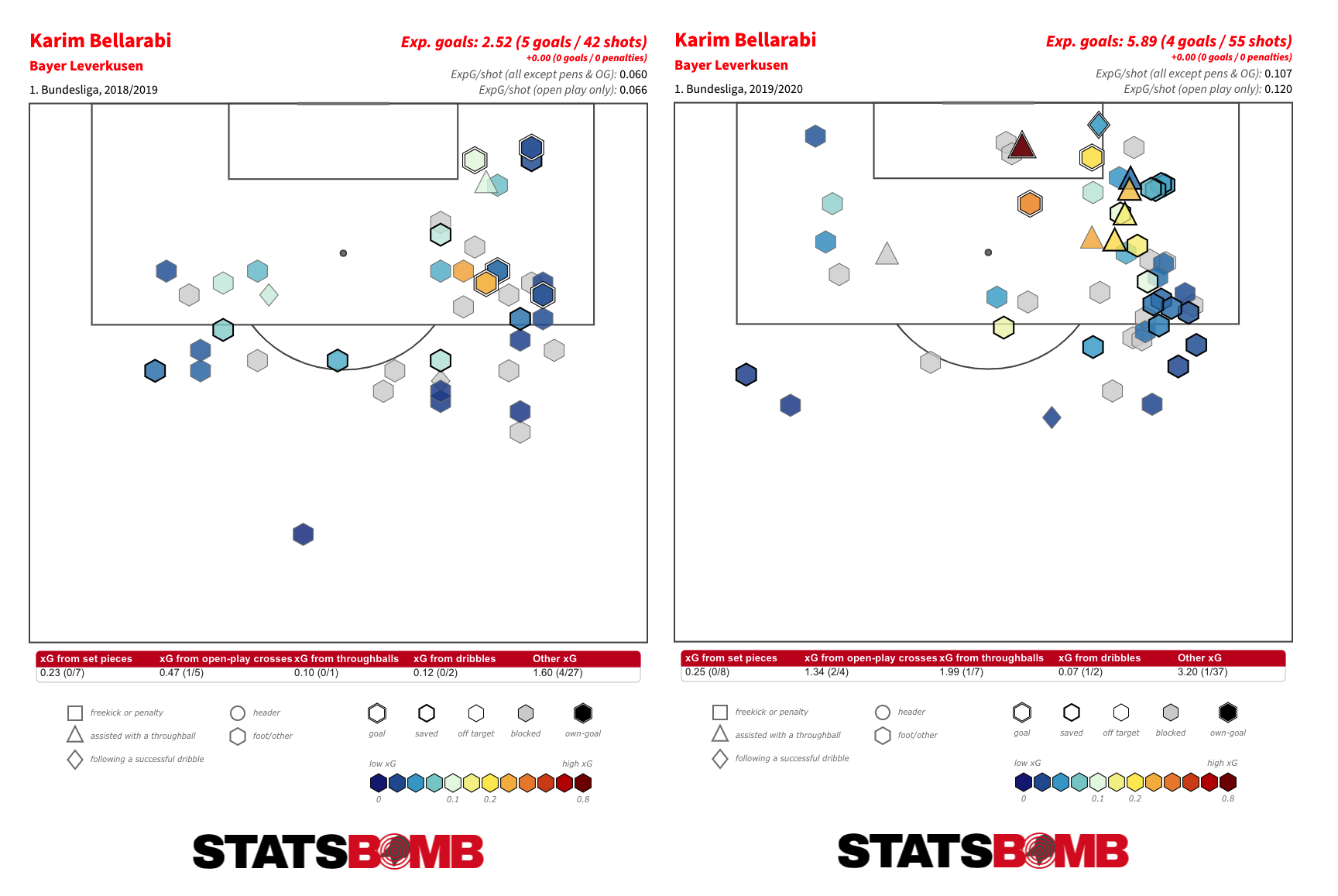

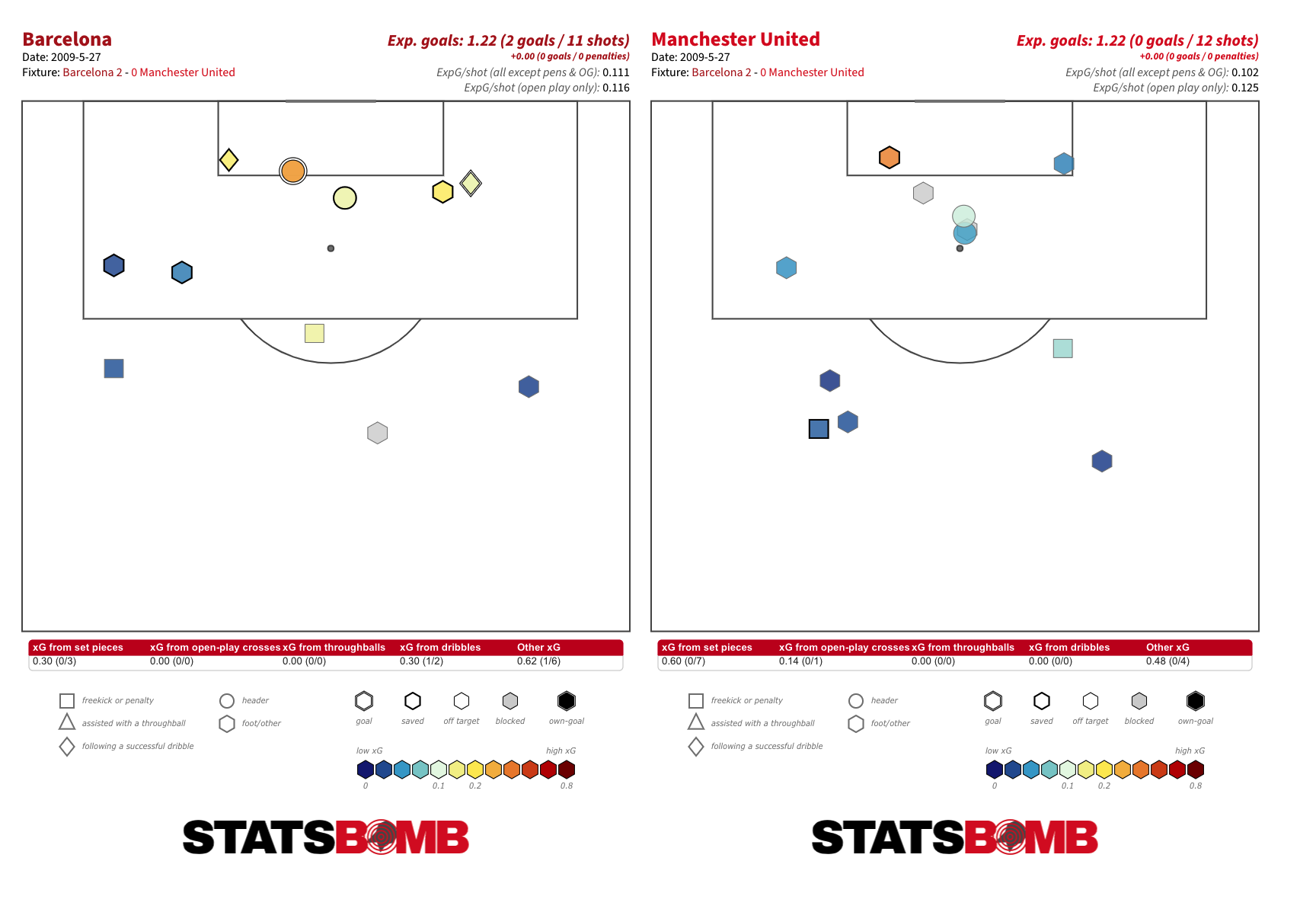

He still likes a dip from range, but has shown ever greater ability to get into good quality finishing positions, and at 22 years old, can't be far off the finished article as a player. Martial too appeared to prosper given the centre forward position. His 17 goals from an expected 10 was a welcome boost, but only continues a theme: few players are over their xG every season, but he has been for his entire time at United, albeit not to this degree before:  If we turn to the new man, Van de Beek, his main qualities can be seen inside the box too. He looks to be a good quality finisher, as we can see from two seasons of Eredivisie shots here:

If we turn to the new man, Van de Beek, his main qualities can be seen inside the box too. He looks to be a good quality finisher, as we can see from two seasons of Eredivisie shots here:  He's predominantly right footed, but there's some left foot and head in there too. We reviewed him for our Pro-Scouting project and our executive summary was as follows: Strengths ● Exceptional off-ball movement in and around the penalty area. ● Goalscoring and chance creation numbers outstanding. ● Positionally versatile, can play as central or attacking midfielder. Weaknesses ● Little involvement in build-up. ● Limited defensive output. Summary Donny van de Beek is world-class within his role. He is an exceptional goalscorer from midfield and combines that with great chance creation numbers. However, his involvement in other areas of the game is limited. It is unclear whether or not this profile is enough for clubs at the very highest level, to which he is often linked. Current: Europa League top 5 leagues Potential: Champions League level, in a very defined role. Transfer Potential ● Ajax do not sell cheap, transfer fee likely to be upwards of 40m. My sense here is that the best of Van de Beek may come later in his contract if United continue to build and recruit well, and he's able to fulfil a specific role, but goals and assists from midfield win friends and can cover sins, so he may well come out ahead regardless. With a deal for Jadon Sancho seemingly receding in likelihood and Lionel Messi yet to be sighted in Lancashire, that's it so far for United. The one position that needs no attention is goalkeeper with David De Gea likely to continue despite a less than stellar 2019-20 and Dean Henderson's future slightly uncertain. He won't be returning to Sheffield United, but is plenty good enough to continue as a Premier League number one for someone. Could there be more depth in defence? The work done last summer in acquiring Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Harry Maguire locked down two positions and Luke Shaw has staged something of a renaissance to claim left-back. Victor Lindelöf has nailed down the other starting role across the last two seasons, and again it feels like a question of whether the assorted depth that exists can cover sufficiently, or whether new blood is needed. It would be great to see Eric Bailly or Phil Jones find a run of form and fitness but those eternal question marks mean another centre back would be nice, while Brandon Williams was a successful find last season and can cover both defensive flanks as required. United's whole line up does feel one key injury away from sticking plasters in most positions so another defender and midfield option would tidily round out the summer. Projection Manchester United have a curious schedule to start. They don't face an away trip to a team that finished in the top half last season until week 12 and Sheffield United on December 15th. Of course this means a bunch of better rated teams visiting Old Trafford early on, including Manchester City, Tottenham, Arsenal and Chelsea, from which they got 10/12 points in the corresponding 2019-20 fixtures. A few things will probably happen:

He's predominantly right footed, but there's some left foot and head in there too. We reviewed him for our Pro-Scouting project and our executive summary was as follows: Strengths ● Exceptional off-ball movement in and around the penalty area. ● Goalscoring and chance creation numbers outstanding. ● Positionally versatile, can play as central or attacking midfielder. Weaknesses ● Little involvement in build-up. ● Limited defensive output. Summary Donny van de Beek is world-class within his role. He is an exceptional goalscorer from midfield and combines that with great chance creation numbers. However, his involvement in other areas of the game is limited. It is unclear whether or not this profile is enough for clubs at the very highest level, to which he is often linked. Current: Europa League top 5 leagues Potential: Champions League level, in a very defined role. Transfer Potential ● Ajax do not sell cheap, transfer fee likely to be upwards of 40m. My sense here is that the best of Van de Beek may come later in his contract if United continue to build and recruit well, and he's able to fulfil a specific role, but goals and assists from midfield win friends and can cover sins, so he may well come out ahead regardless. With a deal for Jadon Sancho seemingly receding in likelihood and Lionel Messi yet to be sighted in Lancashire, that's it so far for United. The one position that needs no attention is goalkeeper with David De Gea likely to continue despite a less than stellar 2019-20 and Dean Henderson's future slightly uncertain. He won't be returning to Sheffield United, but is plenty good enough to continue as a Premier League number one for someone. Could there be more depth in defence? The work done last summer in acquiring Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Harry Maguire locked down two positions and Luke Shaw has staged something of a renaissance to claim left-back. Victor Lindelöf has nailed down the other starting role across the last two seasons, and again it feels like a question of whether the assorted depth that exists can cover sufficiently, or whether new blood is needed. It would be great to see Eric Bailly or Phil Jones find a run of form and fitness but those eternal question marks mean another centre back would be nice, while Brandon Williams was a successful find last season and can cover both defensive flanks as required. United's whole line up does feel one key injury away from sticking plasters in most positions so another defender and midfield option would tidily round out the summer. Projection Manchester United have a curious schedule to start. They don't face an away trip to a team that finished in the top half last season until week 12 and Sheffield United on December 15th. Of course this means a bunch of better rated teams visiting Old Trafford early on, including Manchester City, Tottenham, Arsenal and Chelsea, from which they got 10/12 points in the corresponding 2019-20 fixtures. A few things will probably happen:

- Greenwood's finishing will cool off. He looks a rare talent, but will not often in his career score 10 goals for every 3.7 xG he generates as he did in the league last season

- Penalty returns will reduce. United had a +11 balance (albeit they missed four meaning +7 in goals). Next best in the Premier League across four seasons is +8. They do win a lot of penalties and may continue to do so, but in all likelihood, the gap shrinks between won and conceded.

- The defence will not allow five goals from the next 145 shots (and 12.6 xG) as it did during the 14 game unbeaten run. This equates to opposition finishing at 3.4% which is about as low as when Leicester experienced a wild and unsustainable opponent finishing run, that ultimately powered their title charge in 2015-16. Across the whole season, United's defence was close to its xG, but short term mega-skews should not be misinterpreted as legitimate form changes. The defence is good regardless, just not this good.

Elsewhere, it's hard to pull apart the numbers and categorically conclude this team is moving onwards and upwards quickly. A further comfortable top four finish, with a boost underneath in the stats would probably again represent progress. It's easy to forget the difficulties that this team faced during the first half of 2019-20 and how different it looked then compared to later. Perhaps the two cup defeats were emblematic of the status this United team has reached: nearly there but not quite. Again though the foundation feels a lot more sturdy than it did twelve months ago, and were the board to reach out and make another signing that had the potential to impact as much as Fernandes has, accelerating to better outcomes is achievable. In Solskjær, United may not have a manager driven by an emphatic football philosophy, but they may have one who is able to continue this incremental build towards a stable, strong, talented and competitive team.

If you're a club, media or gambling entity and want to know more about what StatsBomb can do for you, please contact us at Sales@StatsBomb.com We also provide education in this area, so if this taste of football analytics sparked interest, check out our Introduction to Football Analytics course Follow us on twitter in English and Spanish and also on LinkedIn

Crystal Palace were a popular pick to struggle in 2019-20, but crafty veteran Roy Hodgson oversaw a mid-table finish with few wider worries.

Once the league settled down they were never higher than seventh or lower than their finishing position of fourteenth. However, despite all but securing safety in a pre-pandemic world (the hiatus started when they were on 39 points) their form in the short summer recall was dismal (1-1-7). It’s always hard to evaluate a team with little obvious reason to max out performance, but these games were closer to the relatively poor metrics that Palace had put up through to March.

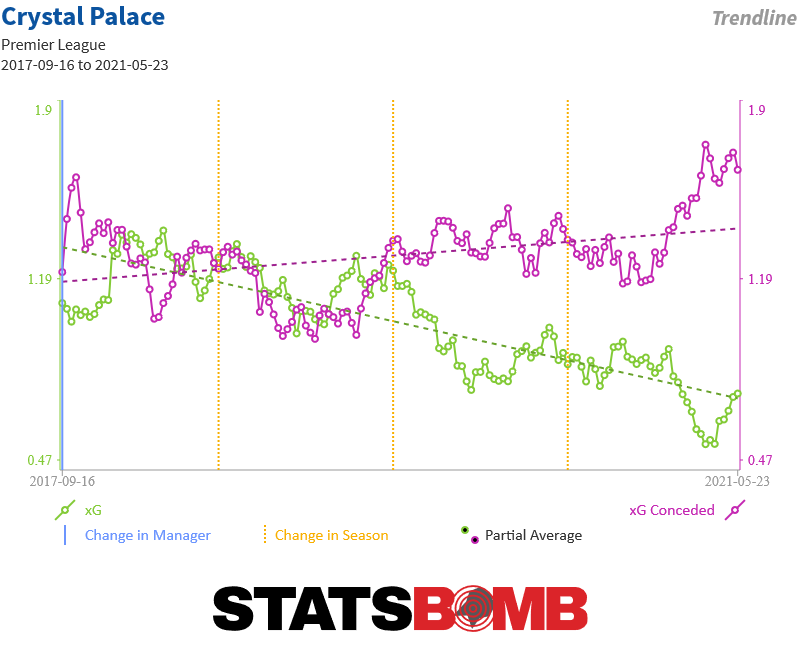

Year on year, this decline was real. While 2018-19’s twelfth placed finish had not foretold doom for this aging squad--it was backed up by tenth placed, borderline par expected goal output--pre-Covid 2019-20 was different. A -0.41 xG per game stat line ranked 17th and the decline was all inhabited within the attack. The team went backwards from twelve shots a game the season before to under ten; at that stage a league worst total. And then, upon restarting, the performances started to match the numbers. When looking at the last two seasons (shown here in the trendlines) we can clearly see how the metrics were okay in 2018-19 and distinctly-not-okay in 2019-20. This is a huge red flag.

Hodgson had been well aware of his team’s potential failings, stating in September that:

“We'd like to score more but we've not been a prolific goalscoring team in these two years”.

This was a comment based on seasons scoring 45 and 51 goals. In 2019-20 they notched just 31, the lowest total in their entire history. Defence may be the priority for Roy, but usually when your attack is underperforming like this you run the risk of landing in a relegation battle. That this didn’t happen here feels like a stroke of fortune that should be recognised as such ahead of this new season. Palace got tangibly worse and somehow never had to face the music. Intriguingly, Pandemic Season One 2019-20, saw “footballing” teams like Norwich and Bournemouth relegated while Aston Villa and for half a season West Ham were also football first, results later and struggled. It doesn’t always play out this way though, and importantly, Palace's age factor won't fail to kick in forever.

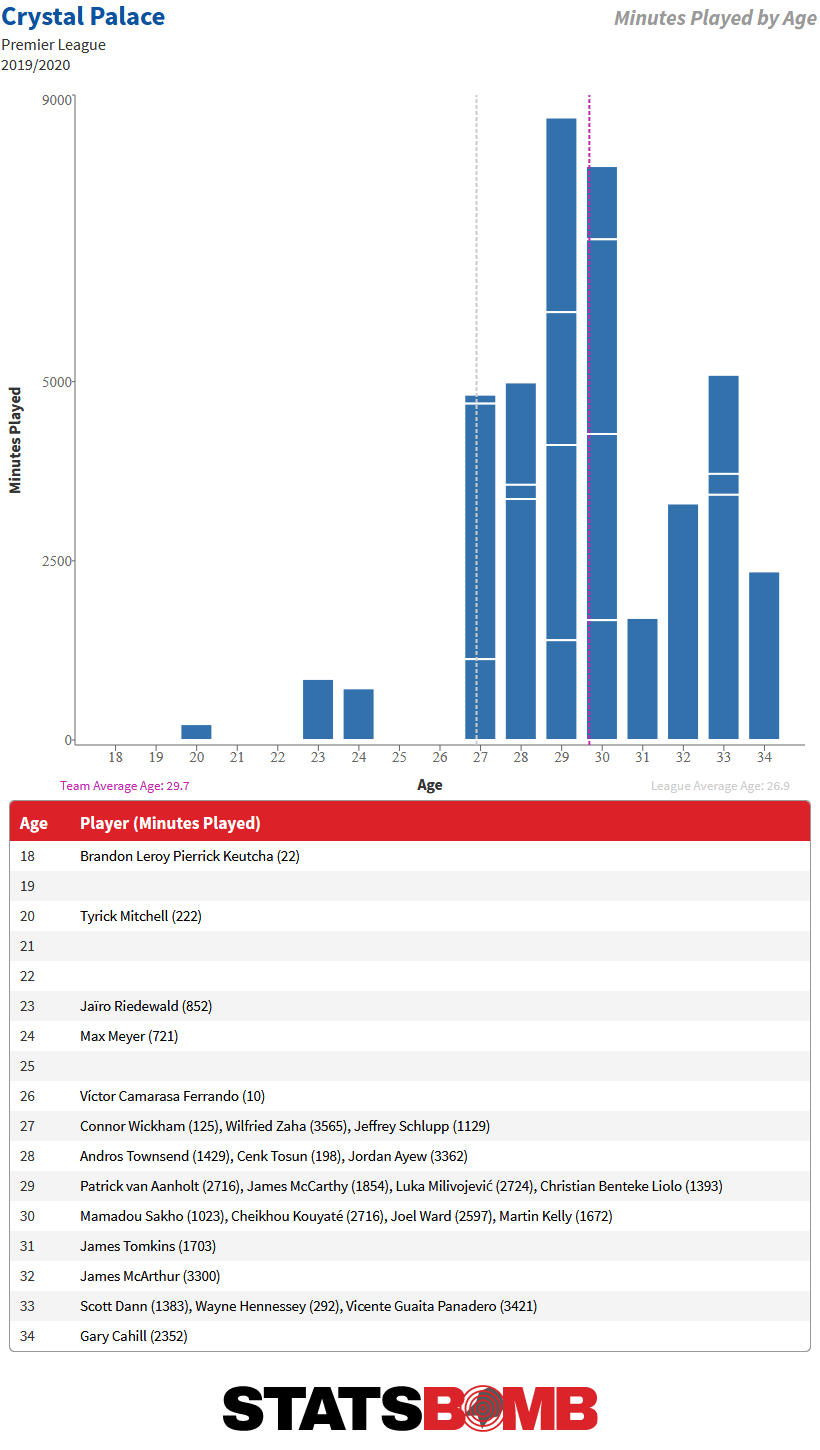

This is the oldest team in the league by some margin. Their average age last season was pushing 30 in a division where 27 is normal. No player under the age of 26 played any significant minutes at all. This was the main factor that provoked pessimism ahead of 2019-20, but now with declining metrics on top of that plus another year, it’s hard to project this team positively:

Goalkeeper Vicente Guaita was a difference maker in 2019-20. We had him ranked third in the Premier League for how active he was in making claims, behind Nick Pope and Alex McCarthy, while for shot stopping only Hugo Lloris and Emiliano Martinez (who had a fine pro-rata run in the late season) were ahead of him. Before arriving in England he was decent for Getafe, and no worse than average in 2018-19 for Palace, so despite age, has scoped out as a fairly positive contributor over a reasonable period of time. As ever though, maintaining hope that your goalkeeper is above average is a function of limited utility to pin hopes upon.

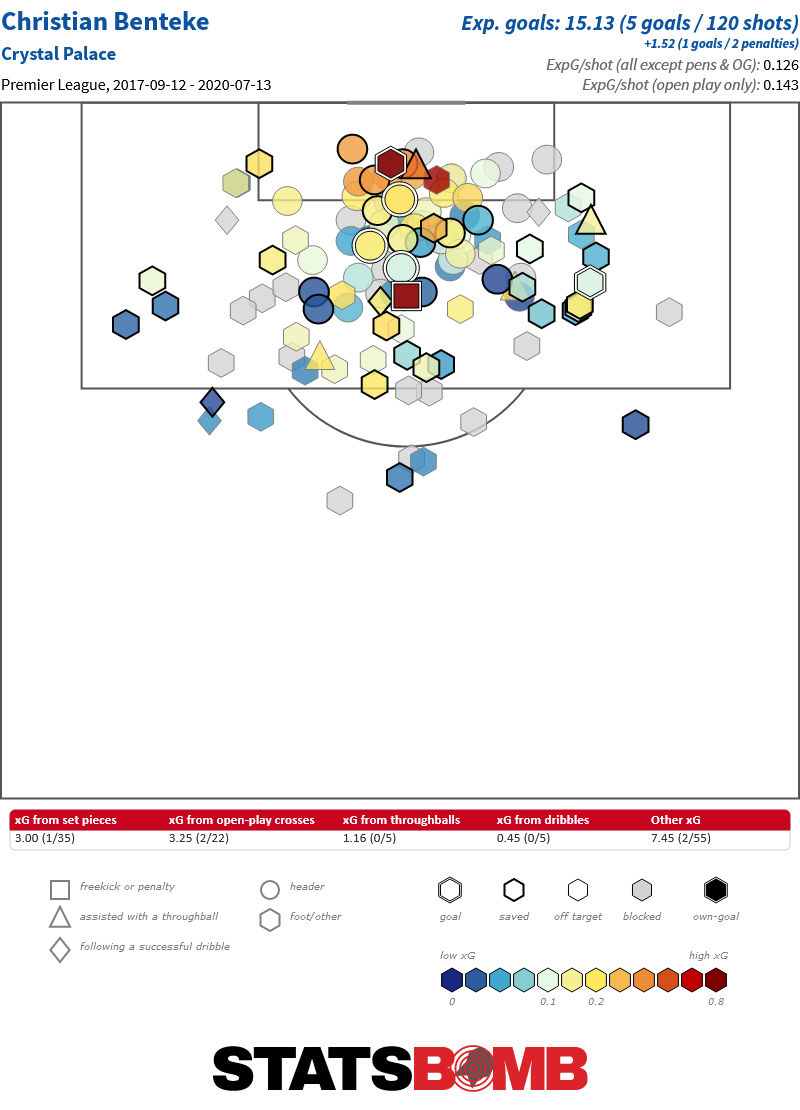

You know what you get with Wilfried Zaha. High volume dribbling, a shot map that eschews a central vortex, turnovers, fouls won and a ceiling that probably explains why the oft mooted big move has never quite materialised. His 2018-19 season saw ten goals, but only four of those were from his main shooting zone; fairly wide on his flank. He continued to shoot from there regularly in 2019-20 but notched just twice from out wide and four times overall while seven total goal contributions was around half his previous two seasons. All his expected contributions mirrored this and declined to their lowest levels since 2016-17 and it's hard to isolate the chicken from the egg. Zaha wasn't particularly good, but nor were any of his attacking teammates. Christian Benteke continues to be an unfortunate poster boy for expected goal variance. This time round his two non-penalty goals came from an expectation of over four. Interestingly, his scoring woes inhabit precisely Roy Hodgson's tenure. The season or so prior to his arrival Benteke was around par--13 goals from 13 xG. Ever since, for three long seasons, it's been hard graft for little reward:

Jordan Ayew scored nine league goals and remains one of the hardest working forwards around. He ranked second for pressure events and fifth for counterpressures among strikers in the division but eighth and 26th for the volume of team regains recorded as a result of them. He's putting the legwork in, but the team doesn't quite push up enough to enact rewards from that. Only two players broached over a quarter of a goal a game contribution for combined goals and assists, Ayew and er... Jeff Schlupp. Only Benteke exceeded the same rate for expected values but under shot by half, and only he again contributed to more than two and a half shots and key passes per game. Whichever way you look at Palace, either in possession or out of it, their attackers ploughed lonely furrows and scarcely clicked.

With the window likely closing on a sizeable windfall for Zaha, team investment may miss a shot in the arm that could have helped from his departure. They simply have to get younger this window and their first two ventures into the transfer market do finally reflect that as do Hodgson's recent comments:

"We are assembling the pieces of our jigsaw with regard to bringing in some fresh, young players to our squad who will provide the quality and energy we have highlighted as being necessary for us to take the next steps forward."

Firstly, Nathan Ferguson arrived for an as yet undecided fee from West Brom. A versatile defender, he instantly injects youth and promise in to the line up but at 19 years old, ideas towards contribution this season should probably be tempered.

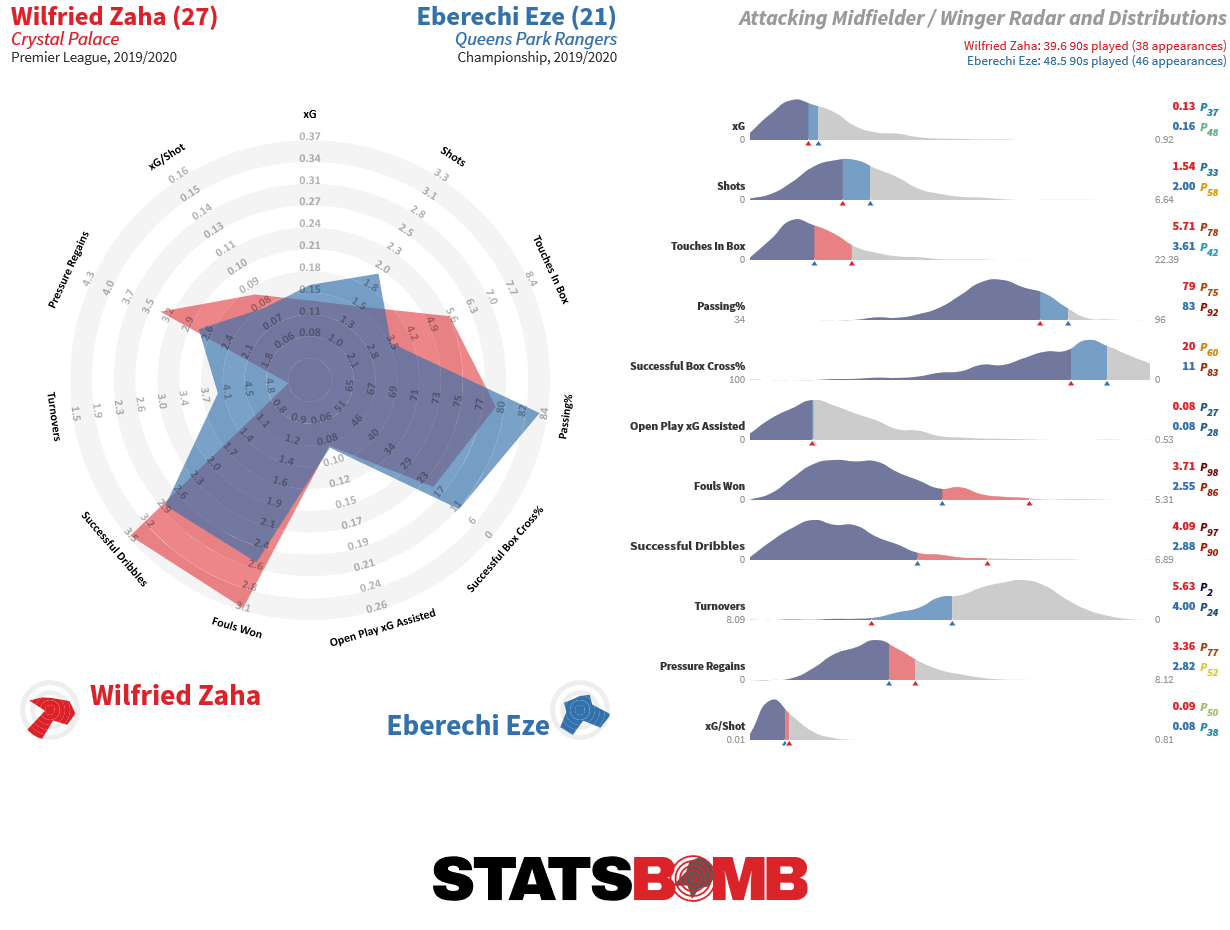

More exciting is the arrival of Eberechi Eze from QPR, for what could be a decent fee, somewhere south of £20m. The Londoner's breakout season saw him notch 14 goals and 7 assists from varied attacking and midfield positions and regularly show up in highlight reels. He is positionally versatile, but frequently occupied the left side--much like Zaha has. How will the attackers all fit together? Zaha did spend time coming from the right in 2019-20 and specifically up front in 2018-19 so it's possible that whoever isn't the left sided starter of the two will find themselves filling different roles in different games, depending on other selection choices (mixing with some combination of one or more of Andros Townsend, Benteke and Ayew too). I'm not going to profess to having seen much of Eze--there's only so much time in the world, even in lockdown--but ideas around why he may have appealed to the Palace dealmakers aren't too far from home. He looks to be slightly more secure on the ball, which is an intriguing boost for an ostensibly flair player and having just turned 22, it's hard not to see his best years as imminent:

Even then, there is a cautionary side of "what next?" for Eze. A headline of 14 goals and 7 assists look great, but he started every game last season, and once you do the maths, it squares off at around 0.35 goals or assists per game, ahead of an expectation below 0.3. His passing threat is boosted by his set-piece contributions which is both great (useful players to have!) and cautionary (his xG Assisted numbers aren't huge, and shrunk just to open play, er... shrink). He looks fairly pressure resistant too which may help him gel into the side, but he is joining the league's worst attack.

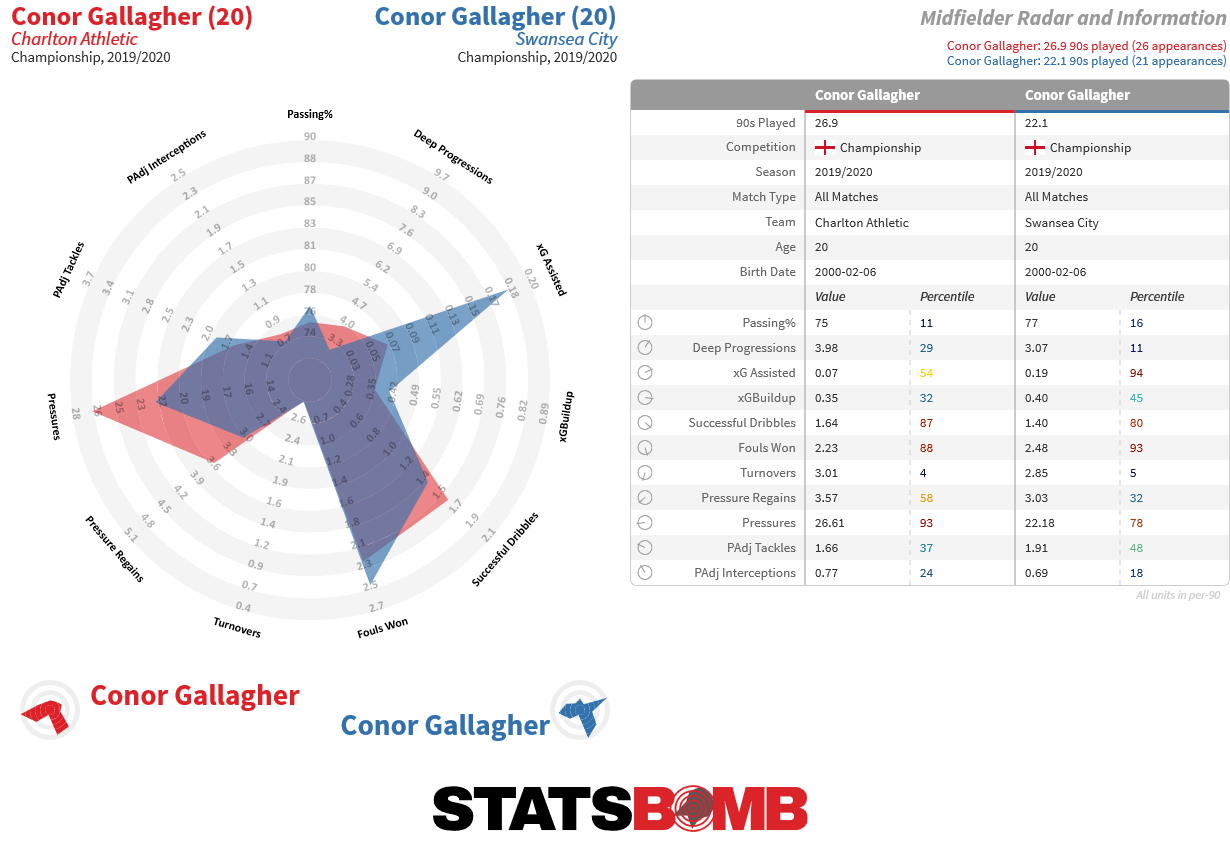

Also likely to arrive is Chelsea loanee Conor Gallagher fresh off a split season with Charlton then Swansea in the Championship. His differing impact across the two tenures are a great example of why data evaluation is only part of any kind of player evaluation. Gallagher's comments here:

"I think at Swansea they have more of the ball than Charlton did, and he [manager Steve Cooper] gave me a chance to create more chances and I think that's why I've got a number of assists for Swansea." are reflected tidily in the numbers:

A hard-working youngster, without understanding his more withdrawn role at Charlton, it could be easy to believe he wasn't capable of being an attacking contributor, but empowered at Swansea and pushed more frequently into a central attacking midfield role, passes into the box from open play increased, his throughball rate rose, chances created came and assists followed. He's got genuine ability in front of the box, and there's just enough about him and Eze to wonder if Hodgson is looking at a change of tack and getting a rare central creator into his side.

All evidence is that Eze and Gallagher are talented players, but they could bring their best game, and still find it hard to shine in this team. They will hopefully get ample chance to prove their promise but if the season gets gritty, will Hodgson bunker down?

Projection The gambling community is understandably well aware of the risks surrounding Palace's near term potential and Sporting Index opened up with a sub-40 point, fifth worst projection. Palace have averaged below a point a game in 2020, and won four from 18 in that period. The trending is wrong and it will take distinct and real change to the team's metrics to give them a chance of steering clear of a relegation battle. Hodgson has been in the game long enough to see the warning signs and in most Premier League seasons there are double the amount of teams that perform at a level to put themselves into the relegation mix, so he may like the chances of winning a coin flip. But planning and execution of strategy are what limit risks such as this, and having been reactive rather than proactive in turning over their squad it could well be tough for the club. Offered seventeenth today, you'd have to take it.

If you're a club, media or gambling entity and want to know more about what StatsBomb can do for you, please contact us at Sales@StatsBomb.com We also provide education in this area, so if this taste of football analytics sparked interest, check out our Introduction to Football Analytics course Follow us on twitter in English and Spanish and also on LinkedIn

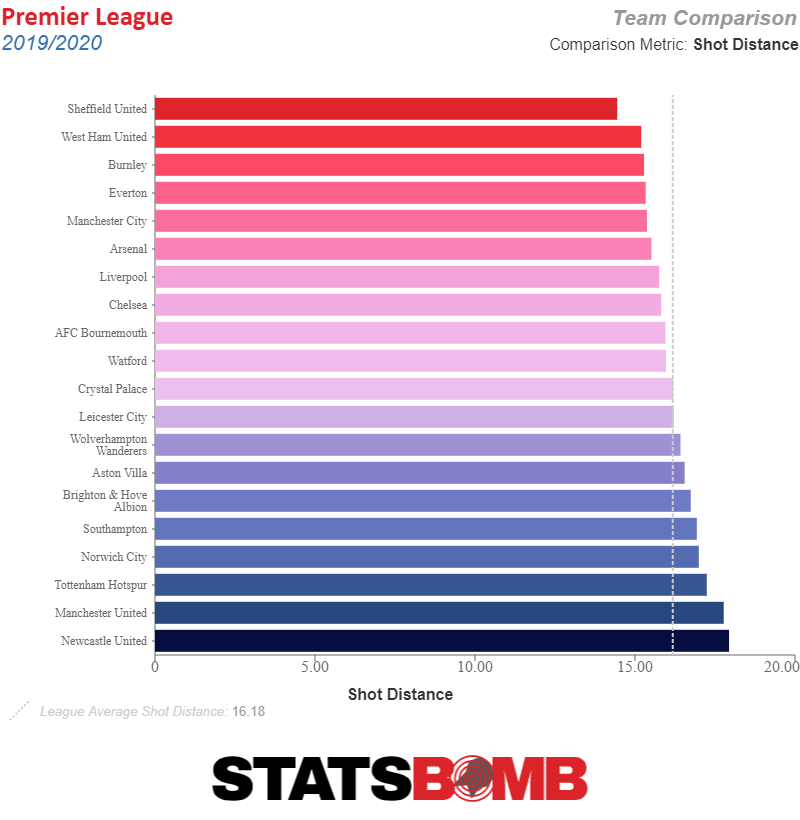

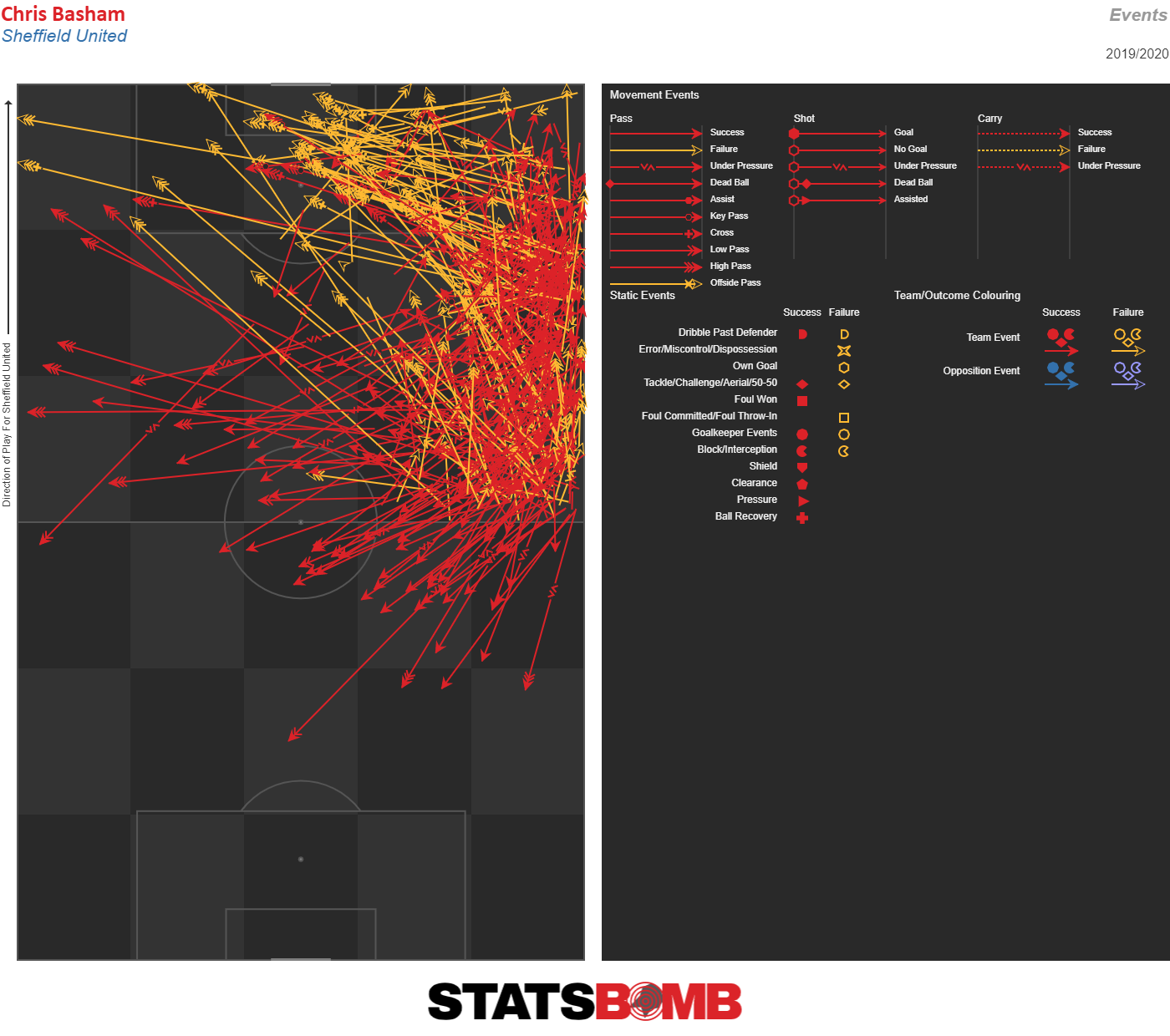

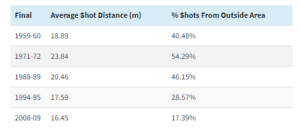

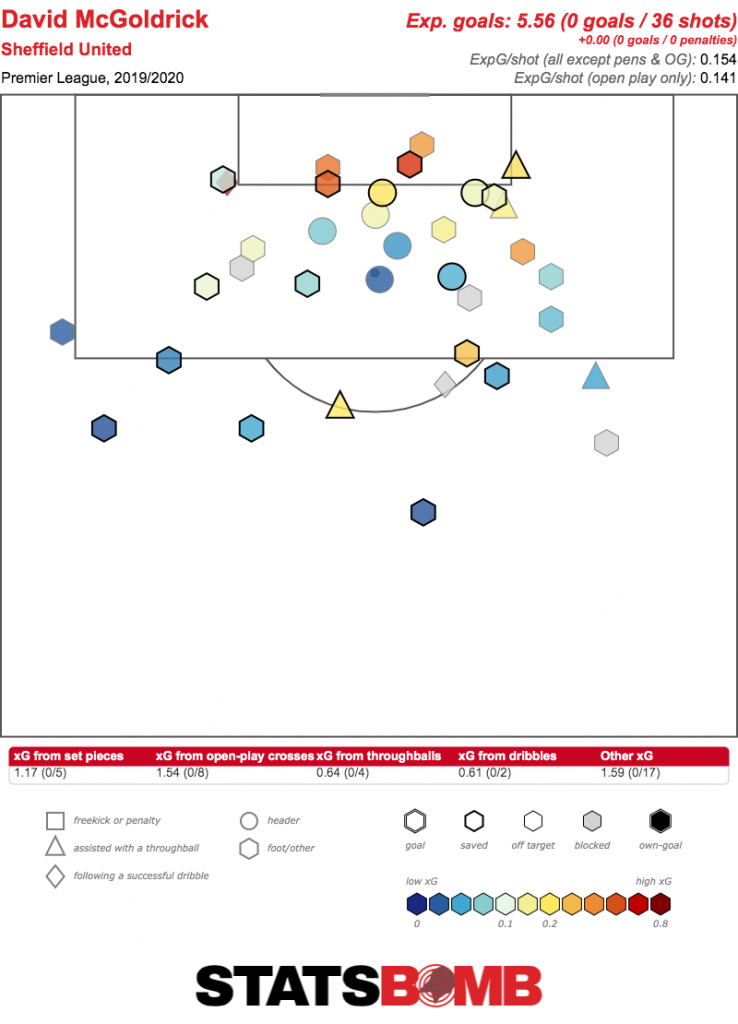

It was 12 months ago that we at StatsBomb proclaimed, to many a raised eyebrow and sanity check, that this newly-promoted Sheffield United side had every capability of mounting an instant challenge for a European place. Just kidding. Of course we didn’t. Nobody did. Even the most optimistic disciples of Chris Wilder and Alan Knill’s managerial abilities - A.K.A Blades supporters - would’ve scoffed at any suggestion they were about to fall just short of a top-seven finish in their return to the top flight, and yet at the same time maybe they wouldn’t have held much disbelief after all. Another season of overachievement would only be following the trend at this point, such has been the rapid and sustained ascent under their four years of management. Only a post-lockdown dip put paid to their European hopes but a 9th placed finish in your first top flight season since 2007 on comfortably the lowest budget in the division? Fans would bite your hand off and probably take a bit of arm and torso too, though it’s easy to imagine the relentlessly ambitious Wilder curling a lip at the idea of a late season dip in form, despite acknowledging prior to June’s fixture vs Manchester United that this was “A Ford Fiesta against a Ferrari”. Relegation favourites in pre-season, Sheffield United not only survived, they thrived. Of course, Wilder and Knill are responsible for setting the team up in the way that has generated this level of success, but the players take full credit for their execution of the game plan as well. The most commonly used ‘back 9’ in United’s 3-5-2 shape, i.e. all but the two forwards, each played 75% or more of the available minutes in the league. Not only was the team selection incredibly consistent, but every single one of the nine had played for the Blades in the Championship the season before. It shouldn’t go unsaid that the post-lockdown drop off coincided with a couple of injuries to members of the Reliable Nine, which only speaks to the necessity that each player knows and understands not only their role in the team but also those of their teammates in order for the sum to be greater than its parts. As much as was rightly made of the tactical novelty and innovation within the side going into and during the season, in the end it didn’t necessarily make for entertaining viewing for the goal-hungry neutral. The promotion-winning 3-4-1-2 shape was adapted to a more compact 3-5-2; personnel wise it saw the creative-but-slight Mark Duffy replaced by the three-lunged John Lundstram. The product was more suited to coping with the higher quality of opposition but games involving the Blades saw just 78 goals at an average of 2.05 per game – a Premier League low. It was a tweak to the system rather than an overhaul, the same principles of play remained: telepathic rotations and combination play, a focus on wide overloads, and a desire to create quality rather than quantity. Just like their Championship promotion season, Sheffield United again had the closest average Shot Distance in the league in 2019/20, whilst their xG/shot – the average expected conversion rate of their shots – was in esteemed company, bettered only by Man City and Arsenal and even a touch better than Liverpool’s.  Having a laser-focus on creating quality opportunities negated the fact that they actually took the fewest shots in the league, only adding to the novelty of the Blades’ methods – creating fewer shots than all three relegated sides and the rest is not something you’d associate with a team pushing for European qualification but, unusual though it may be, it did the job. The reason for this ‘low volume / high quality’ aspect of their attacking play is their propensity for crossing both from deep and through combinations to get to the byline. Tough passes to execute but often leading to chances from central areas and close to goal when they did connect. Their wing play and crossing approach was ably supported, of course, by – get your klaxons ready people – the overlapping centre backs. Player of the year Chris Basham’s performances have led to the Bramall Lane stands christening his position the ‘Basham role’, and his pass map from right and central areas in the opposition half highlight how often he got forward to add extra numbers to United’s play in the attacking phase.

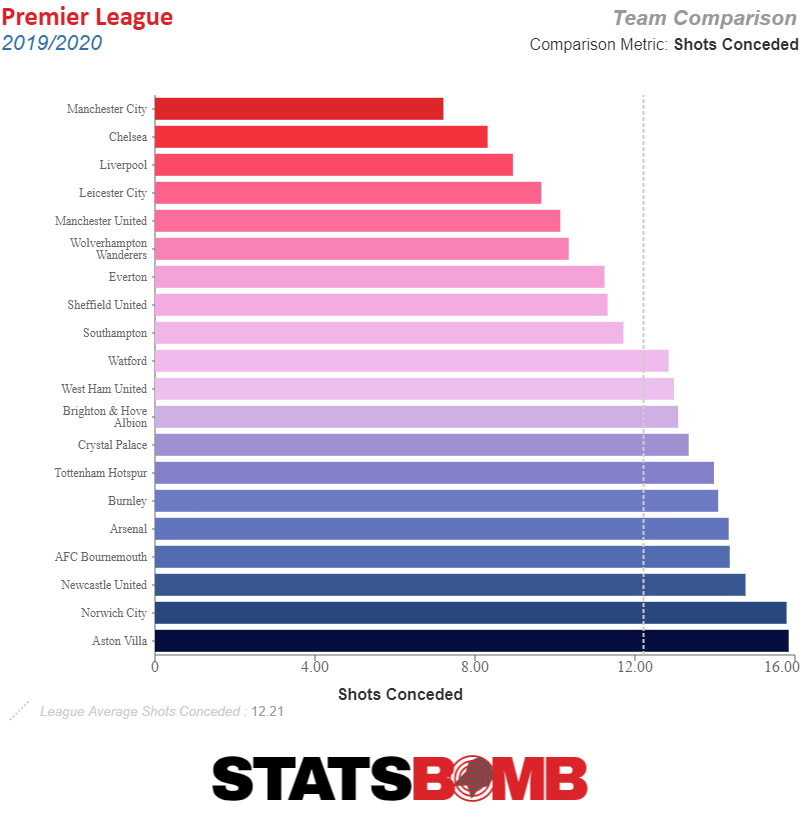

Having a laser-focus on creating quality opportunities negated the fact that they actually took the fewest shots in the league, only adding to the novelty of the Blades’ methods – creating fewer shots than all three relegated sides and the rest is not something you’d associate with a team pushing for European qualification but, unusual though it may be, it did the job. The reason for this ‘low volume / high quality’ aspect of their attacking play is their propensity for crossing both from deep and through combinations to get to the byline. Tough passes to execute but often leading to chances from central areas and close to goal when they did connect. Their wing play and crossing approach was ably supported, of course, by – get your klaxons ready people – the overlapping centre backs. Player of the year Chris Basham’s performances have led to the Bramall Lane stands christening his position the ‘Basham role’, and his pass map from right and central areas in the opposition half highlight how often he got forward to add extra numbers to United’s play in the attacking phase.  Of course, there’s little reason to focus on their attacking play when it’s the defence that powered the Blades to their lofty finish. Conceding just 39 goals as a newly promoted team, a number bettered only by the eventual top three, takes some doing. Creating openings did not come easy to their opponents, even the “Ferraris”: games against Chelsea, Spurs and Arsenal returned three wins, three draws, no defeats. Three elements forged this Steel City defence. The first was limiting the opportunities their opposition were able to generate, with the sheer number of bodies United would have in the centre of the park both in the defensive and the midfield lines often doing a fine job of congesting that area and forcing the opposition to look for openings elsewhere – the 11.32 shots conceded per game was 8th fewest. Of the sides that had a better record, only Everton finished below them.

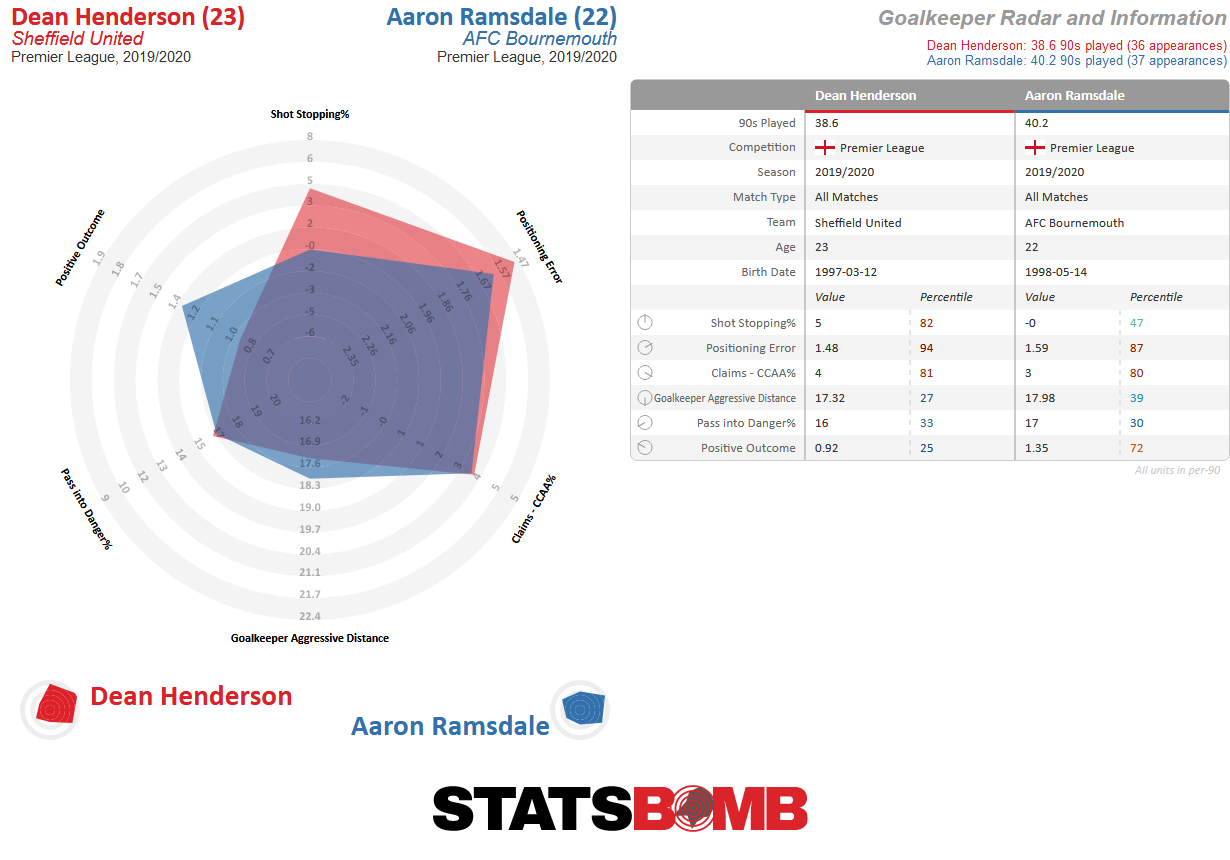

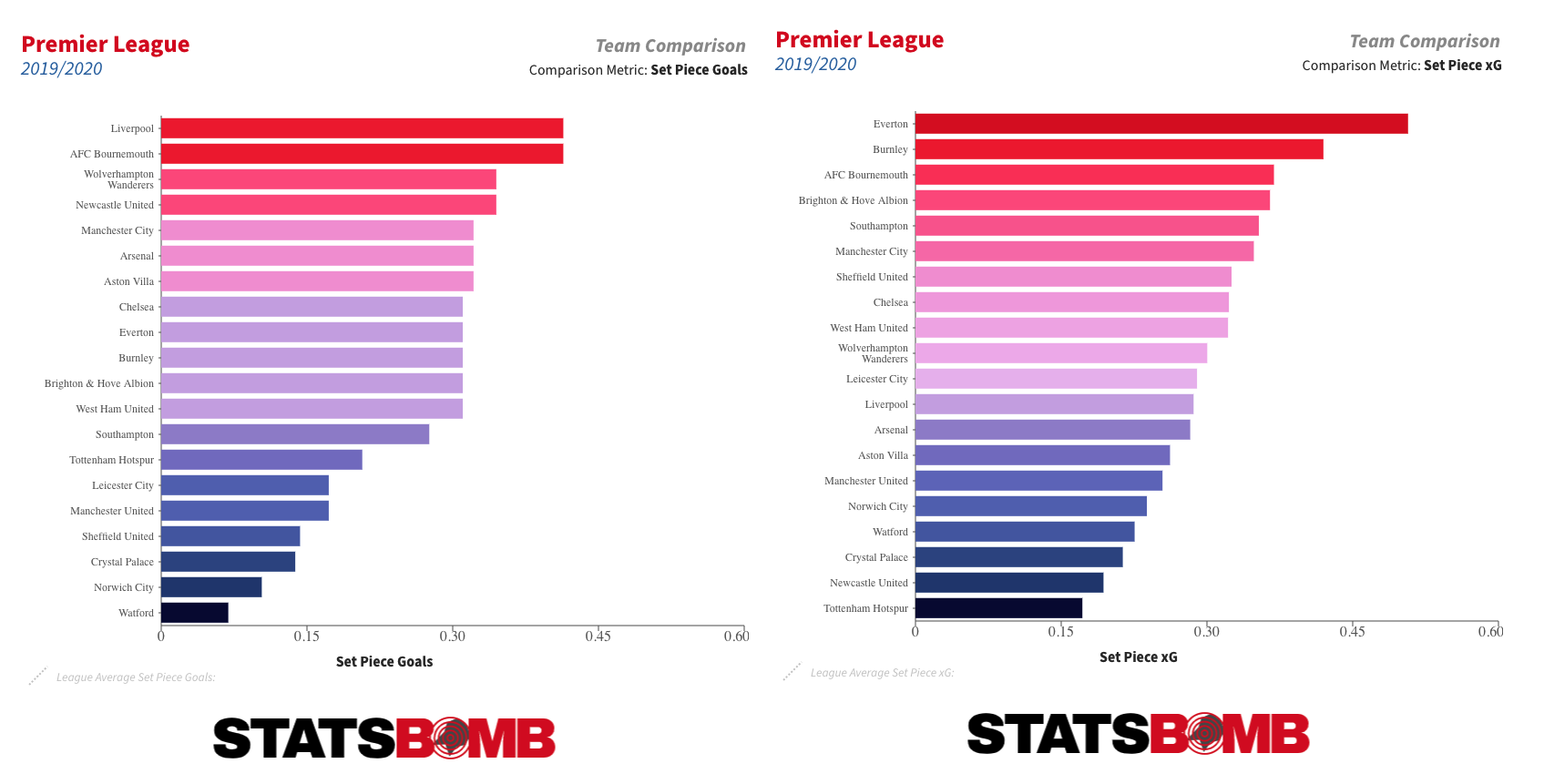

Of course, there’s little reason to focus on their attacking play when it’s the defence that powered the Blades to their lofty finish. Conceding just 39 goals as a newly promoted team, a number bettered only by the eventual top three, takes some doing. Creating openings did not come easy to their opponents, even the “Ferraris”: games against Chelsea, Spurs and Arsenal returned three wins, three draws, no defeats. Three elements forged this Steel City defence. The first was limiting the opportunities their opposition were able to generate, with the sheer number of bodies United would have in the centre of the park both in the defensive and the midfield lines often doing a fine job of congesting that area and forcing the opposition to look for openings elsewhere – the 11.32 shots conceded per game was 8th fewest. Of the sides that had a better record, only Everton finished below them.  The second element? Dean Henderson. When their opponents did generate a shot, they often found the Manchester United loanee in the sort of form that catapulted him into immediate England contention, earning him a first senior callup in October. Henderson particularly excelled in the old-fashioned arts of goalkeeping: taking pressure off the defence by claiming crosses and making saves that you shouldn’t necessarily expect him to make. Lastly, the Blades performed well on set play’s once again, though this time the acclaim comes on the defensive end, tying with Leicester for the fewest set play goals conceded with 6. When combined, these elements made for a stubborn defence that gave United a reasonable chance of taking a result from virtually every game they played in the 2019/20 season. Unfortunately, Henderson’s form was too good for the decision makers at Old Trafford to ignore and he looks set to compete with David De Gea for the #1 jersey there in 2020/21. Wilder and his recruitment team moved quickly to replace him, spending £18.5 million on bringing Aaron Ramsdale in from relegated Bournemouth. Not far behind Henderson in the England pecking order, Ramsdale will be hoping he can follow in his predecessor’s footsteps and comes with decent pedigree and an upwardly mobile trajectory mirroring that of his new club; capped 26 times in England’s age group squads and also comes in on the back of winning Young Player of the Year at AFC Wimbledon in 2018/19 and Supporters Player of the Year at Bournemouth in 2019/20.

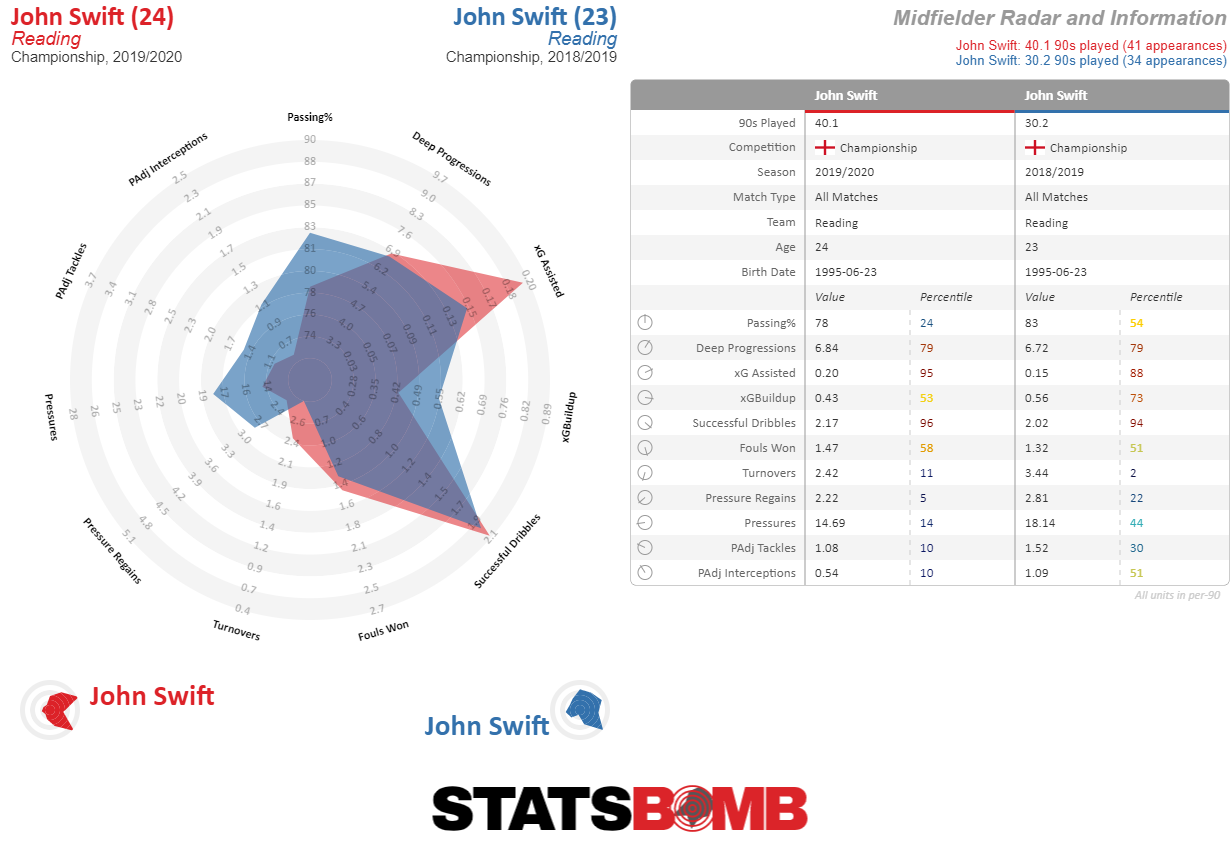

The second element? Dean Henderson. When their opponents did generate a shot, they often found the Manchester United loanee in the sort of form that catapulted him into immediate England contention, earning him a first senior callup in October. Henderson particularly excelled in the old-fashioned arts of goalkeeping: taking pressure off the defence by claiming crosses and making saves that you shouldn’t necessarily expect him to make. Lastly, the Blades performed well on set play’s once again, though this time the acclaim comes on the defensive end, tying with Leicester for the fewest set play goals conceded with 6. When combined, these elements made for a stubborn defence that gave United a reasonable chance of taking a result from virtually every game they played in the 2019/20 season. Unfortunately, Henderson’s form was too good for the decision makers at Old Trafford to ignore and he looks set to compete with David De Gea for the #1 jersey there in 2020/21. Wilder and his recruitment team moved quickly to replace him, spending £18.5 million on bringing Aaron Ramsdale in from relegated Bournemouth. Not far behind Henderson in the England pecking order, Ramsdale will be hoping he can follow in his predecessor’s footsteps and comes with decent pedigree and an upwardly mobile trajectory mirroring that of his new club; capped 26 times in England’s age group squads and also comes in on the back of winning Young Player of the Year at AFC Wimbledon in 2018/19 and Supporters Player of the Year at Bournemouth in 2019/20.  To date, only Wes Foderingham as a backup ‘keeper has followed Ramsdale through the door, but it’s clear that the Blades will be targeting a bit more quality in the middle and top end of the pitch in order to enhance their attacking output. Links with Matty Cash who had an impressive season for Nottingham Forest make sense – the winger-turned-right-back would provide quality in the final third, though the intensity of those links seem to have died down in recent weeks. A deal for Reading’s John Swift would also add some much-needed creativity to the Blades midfield line and could make the difference in games when they’re on top and in search of a breakthrough. Swift’s last two seasons in the Championship have seen him regularly demonstrate his creative capabilities, but he also has a dribbling ability that has been missing from Sheffield United’s arsenal in the last couple of seasons.

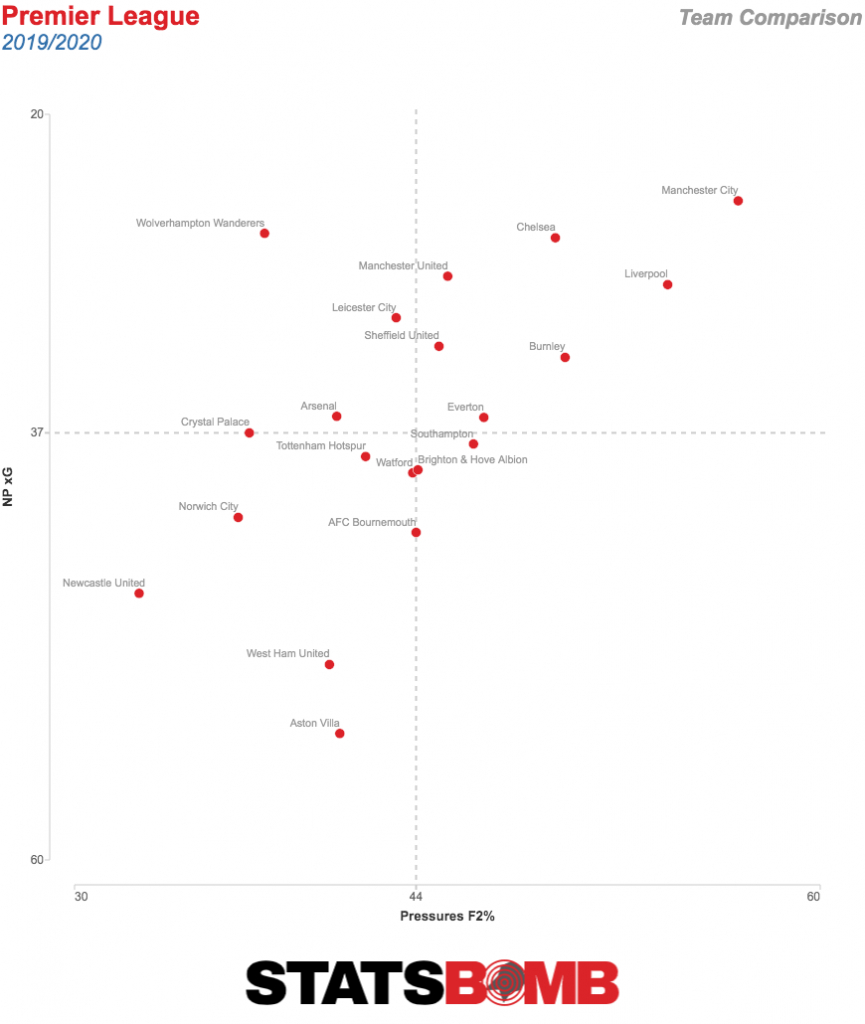

To date, only Wes Foderingham as a backup ‘keeper has followed Ramsdale through the door, but it’s clear that the Blades will be targeting a bit more quality in the middle and top end of the pitch in order to enhance their attacking output. Links with Matty Cash who had an impressive season for Nottingham Forest make sense – the winger-turned-right-back would provide quality in the final third, though the intensity of those links seem to have died down in recent weeks. A deal for Reading’s John Swift would also add some much-needed creativity to the Blades midfield line and could make the difference in games when they’re on top and in search of a breakthrough. Swift’s last two seasons in the Championship have seen him regularly demonstrate his creative capabilities, but he also has a dribbling ability that has been missing from Sheffield United’s arsenal in the last couple of seasons.  A refresh will also be needed up top soon, if not now. Despite his well-documented finishing issues, David McGoldrick remains a key cog in the Sheffield United frontline for his all-round play but at 32 will need more help and sooner rather than later. Oli McBurnie will be hoping to improve his goal output despite a reasonable first season in red-and-white overall, whilst Lys Mousset sneakily finished the season with 0.67 Goals+Assists per 90 minutes played, but lacked the fanfare due to rarely being able to get on the pitch and lacking the same contribution in other areas of the game that McGoldrick and McBurnie are able to make. Billy Sharp can always be counted on to poach goals but, at 34, isn’t likely to see an increase on the 1134 minutes he played in 2019/20. You can’t help but wonder what would now represent a season of over or underachievement for United given expectation levels are having to realign themselves once again. There’s no two ways about it, the element of surprise has gone and the opposition will know what to expect from them this time around, whilst conceding the 4th-fewest goals in the league will be a tough act to repeat. That said, Wilder will be expecting his attacking players to make a larger contribution to compensate for that and it’s likely that he’ll be challenging his players to go and repeat their achievements now they’ve already proven that it can be done. Repeating or improving on the 9th place finish will undoubtedly be a challenge but you sense that failing to do so may not represent a step backwards for this side anyway. A season of further consolidation may just be the springboard United need in order to hurl themselves through another glass ceiling further down the line.

A refresh will also be needed up top soon, if not now. Despite his well-documented finishing issues, David McGoldrick remains a key cog in the Sheffield United frontline for his all-round play but at 32 will need more help and sooner rather than later. Oli McBurnie will be hoping to improve his goal output despite a reasonable first season in red-and-white overall, whilst Lys Mousset sneakily finished the season with 0.67 Goals+Assists per 90 minutes played, but lacked the fanfare due to rarely being able to get on the pitch and lacking the same contribution in other areas of the game that McGoldrick and McBurnie are able to make. Billy Sharp can always be counted on to poach goals but, at 34, isn’t likely to see an increase on the 1134 minutes he played in 2019/20. You can’t help but wonder what would now represent a season of over or underachievement for United given expectation levels are having to realign themselves once again. There’s no two ways about it, the element of surprise has gone and the opposition will know what to expect from them this time around, whilst conceding the 4th-fewest goals in the league will be a tough act to repeat. That said, Wilder will be expecting his attacking players to make a larger contribution to compensate for that and it’s likely that he’ll be challenging his players to go and repeat their achievements now they’ve already proven that it can be done. Repeating or improving on the 9th place finish will undoubtedly be a challenge but you sense that failing to do so may not represent a step backwards for this side anyway. A season of further consolidation may just be the springboard United need in order to hurl themselves through another glass ceiling further down the line.

If you're a club, media or gambling entity and want to know more about what StatsBomb can do for you, please contact us at Sales@StatsBomb.com We also provide education in this area, so if this taste of football analytics sparked interest, check out our Introduction to Football Analytics course Follow us on twitter in English and Spanish and also on LinkedIn

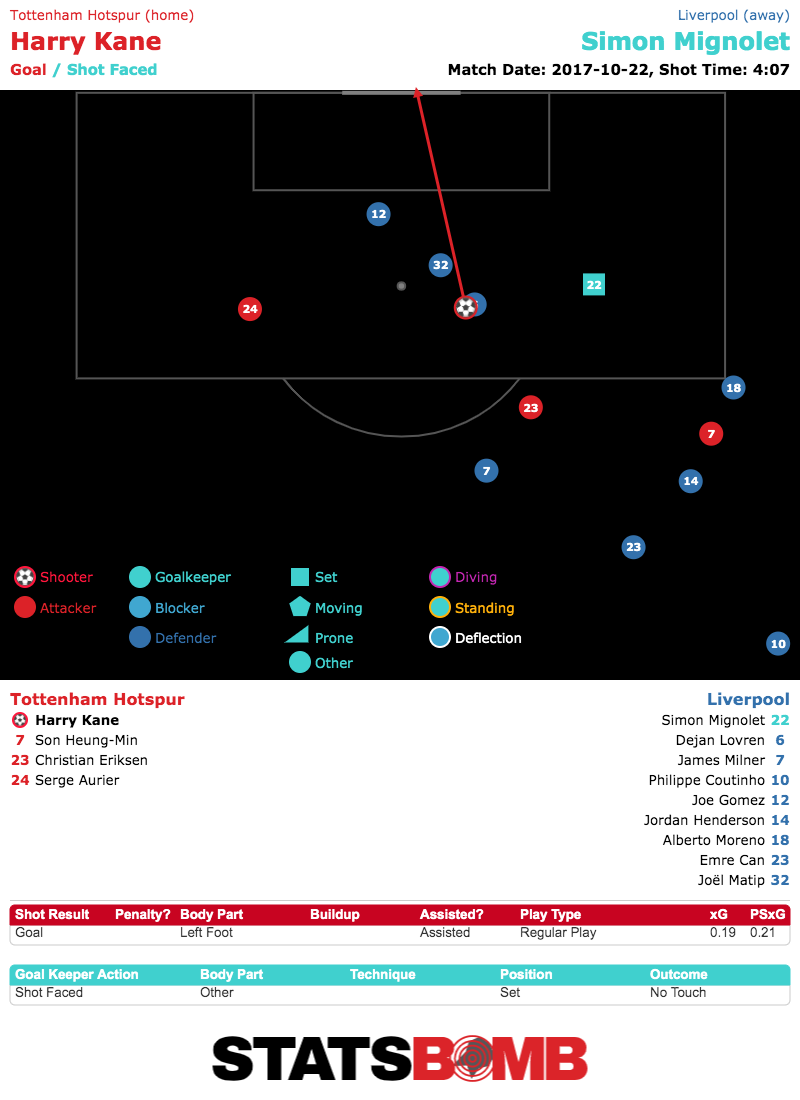

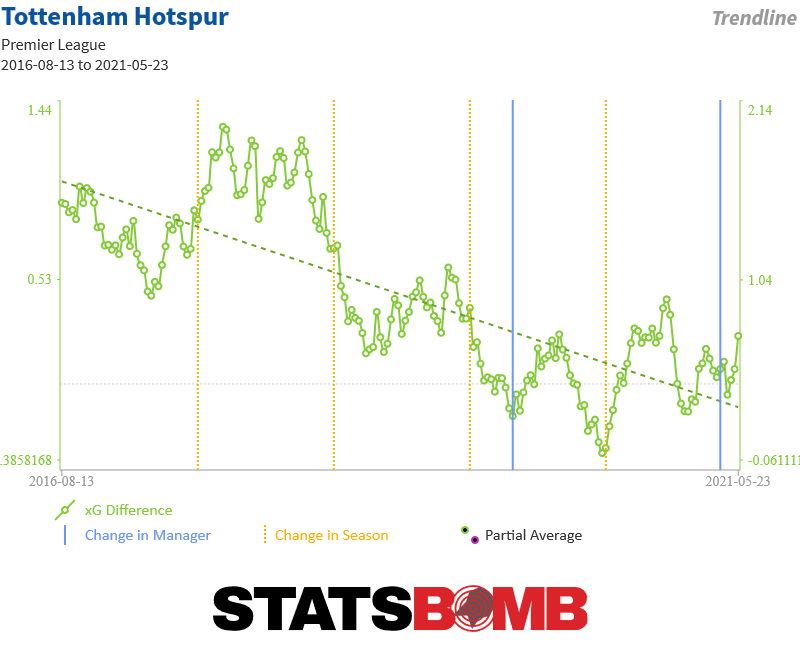

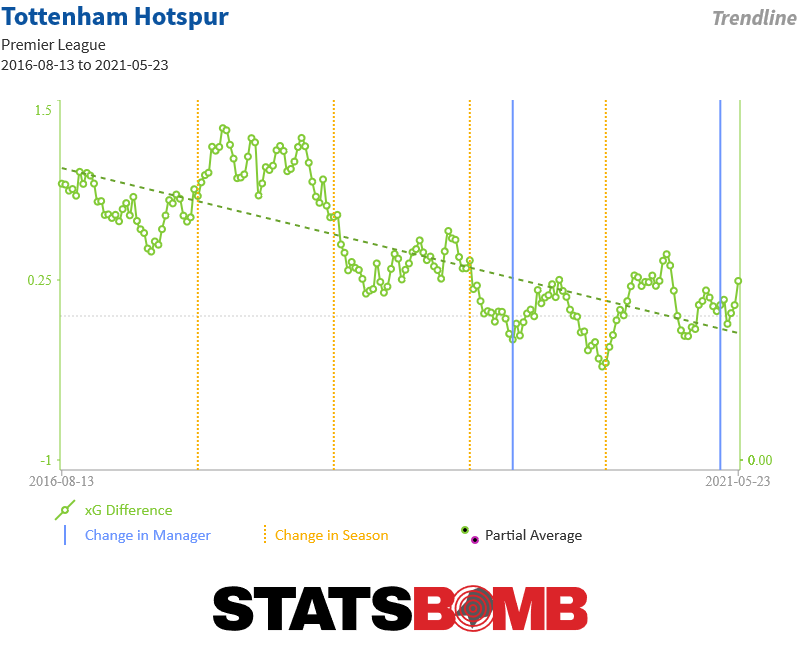

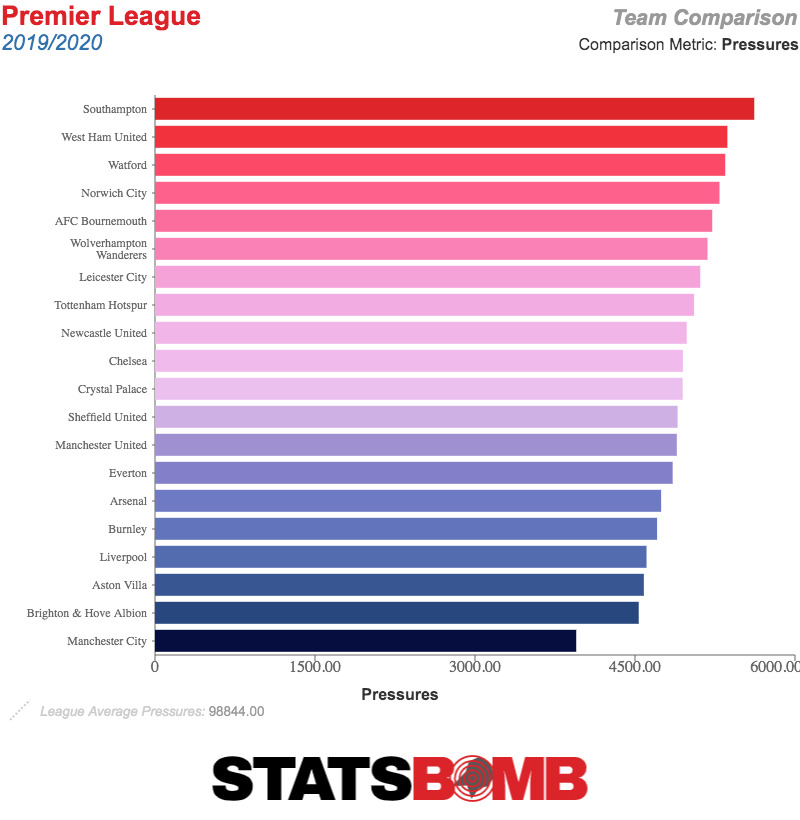

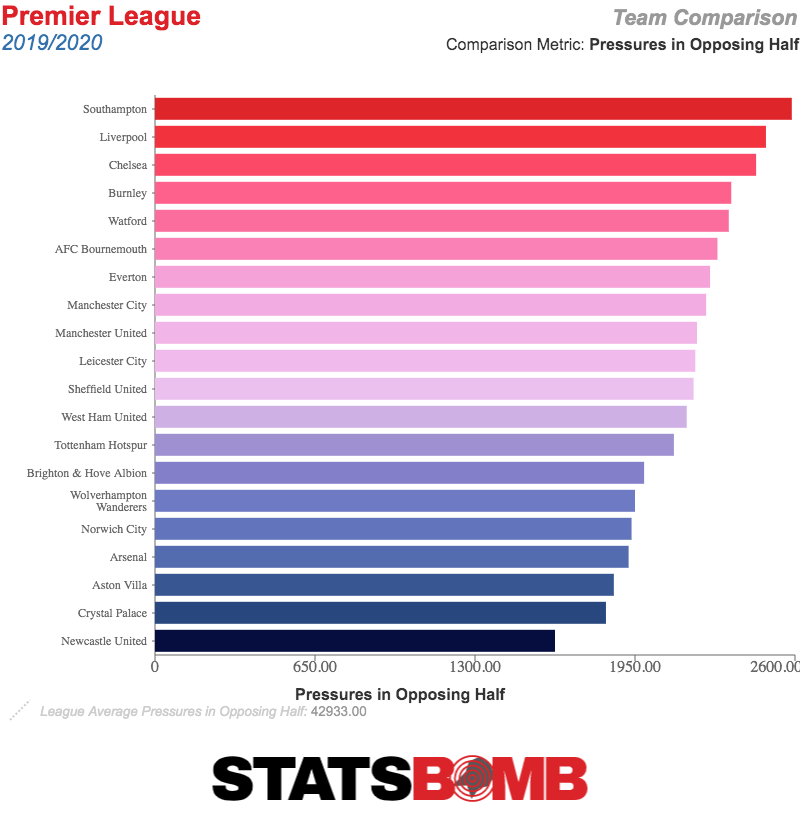

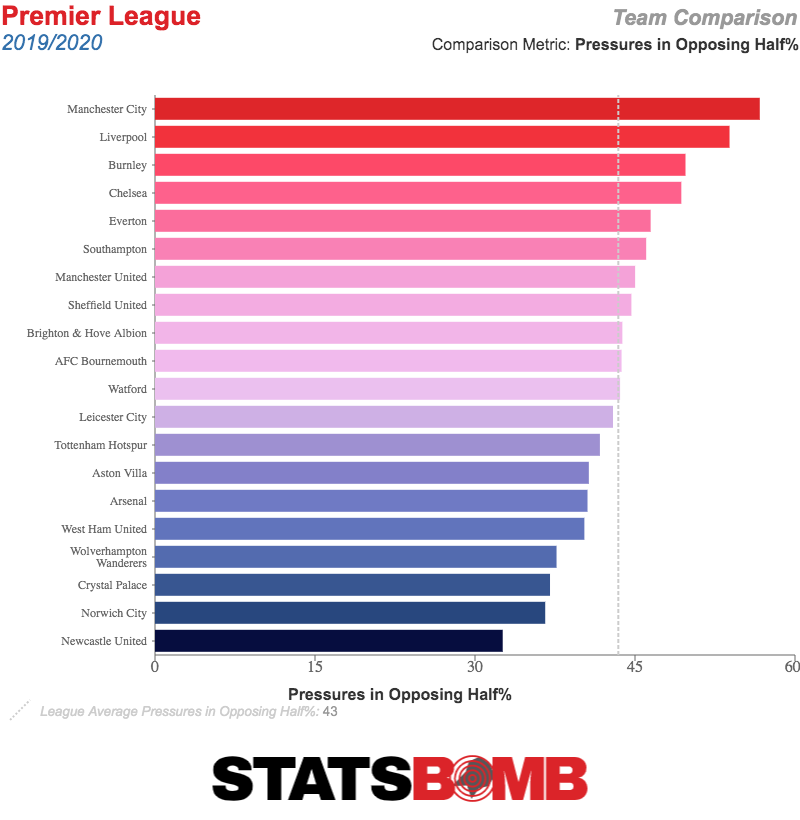

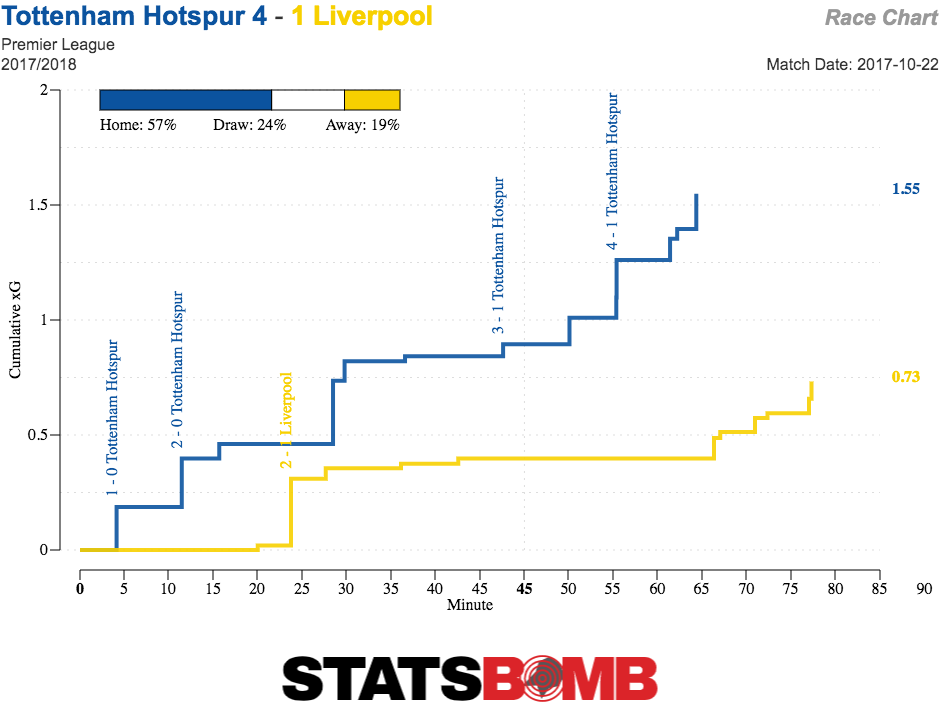

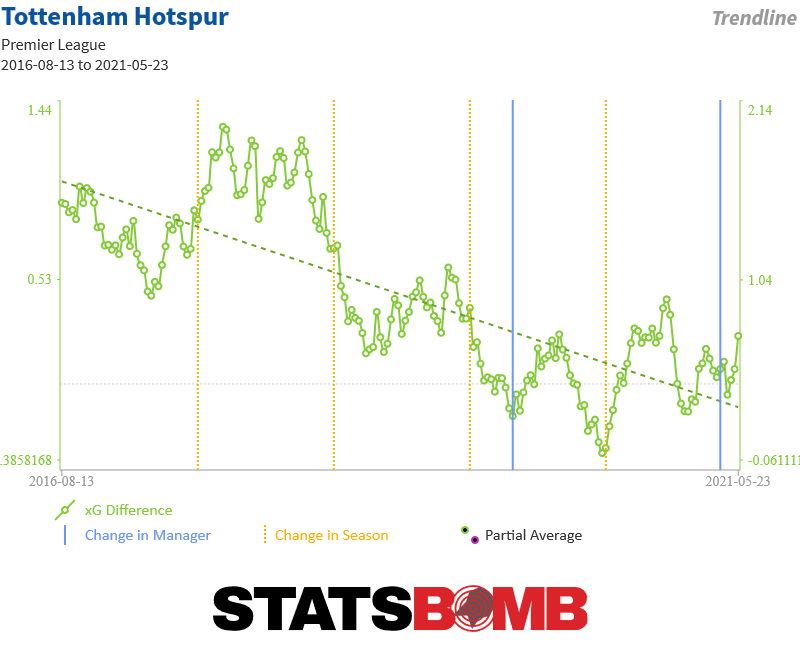

Ahead of 2019-20, on the surface, it was relatively easy to be positive about the future for Tottenham. Fresh from another top four finish and a memorable run to the Champions League final, the club had finally secured the future of its midfield by acquiring Giovani Lo Celso on a loan-to-buy deal from Real Betis while Tanguy Ndombélé had arrived for a large fee from Lyon. Sure, the club had no rotation for Harry Kane and their metrics had been declining alarmingly for 18 months, but what could go wrong? A TV show was even commissioned!  Well, the first thing that went wrong was that the metrics got worse. The second thing that went wrong was the results were terrible. The third thing that went wrong was Mauricio Pochettino was fired. Really, this was all just one large thing that engulfed the club in a manner befitting of a 22-minute segment in a documentary. There was no way around it though, Tottenham had three wins from twelve in the league, had deserved no more from their performances and had been annihilated 7-2 in the Champions League by a promising German side, Bayern Munich. Enter Mourinho. On the surface the 26 league games Mourinho has overseen have been just about good enough. Tottenham got 45 points (65 point pace) which ranked fourth and their goal difference of +13 ranked fourth too. What that conceals is that Mourinho’s tenure has already been through three distinct acts, and the main hope for fans is that the most recent of those acts involved winning more frequently than not. It's also challenging to get used to a Tottenham team that plays very different football to that of the best of Pochettino--and by the time of his departure, despite the Champions League run, that best was a long time passed. Act 1: Duration: 8 games in 2019 Results: 5-1-2 GD: +6 xG: +5 Note: xG Against at 0.65 per game is best in the league The start for Mourinho was promising but didn't come without disappointments. Defeats against his two former clubs, Manchester United (2-1 at Old Trafford in a low event game decided by a Marcus Rashford penalty) and Chelsea (2-0 at home, a Willian penalty sealing the deal soon after renowned hatchet man Son Heung-min was sent off) were classics in the "create nothing, try not to lose" Mourinho canon. Elsewhere the team won five from six before the turn of the new year and certain metrics shone brightly; in defence, the team was giving up very few shots, specifically in good, central dangerous locations. Occasional penalties apart, Tottenham were repelling all. Yes, the schedule was quite kind, but there was a win over Wolves in there too alongside more straightforward victories against lower ranked teams such as Burnley, West Ham, Brighton and Bournemouth. Something to build on? Act 2: Duration: 9 games in a world gradually learning about coronaviruses Results: 3-2-4 GD: +0 xG: -5 Note: xG Against at 1.82 per game is second worst in the whole league The second act was not-so-good. In fact it was downright bad. The schedule bit a little with defeats against Southampton (1-0, created nothing), Liverpool (1-0, played surprisingly well, at least in the second half), Chelsea (again 2-1, this time created nothing, deserved nothing) and Wolves (3-2, overpowered late on, gave it away). There was also a 2-0 win against Manchester City which was as equally improbable as the 2-2 draw earlier in the season at the Etihad. In both games City did enough to win multiple games but somehow couldn't get anything to stick. But the underlying concern came in the same form that had looked so promising weeks before. The defence faltered horribly, moving from league best to nearly league worst and in every one of these nine games Tottenham allowed xG worth between 1.4 to 3.7 per game. They didn't have a single defensively secure game all through and were averaging 16 shots per game against. Really grim stuff. Tottenham also departed the Champions League after being significantly worse than RB Leipzig and lost in the FA Cup on penalties to Norwich, the kind of result that is hard to explain away when you know, deep down, the manager would like to nab a trophy and quick. When the curtains came down on football, they had lost five out of six, and were limping along having been left weakened by injuries to key men such as Kane and Son. Act 3: Duration: 9 games, summer is here and so is your Premier League finale Results: 5-3-1 GD: +7 xG: -2 Note: xG For is 15th, xG Against is 6th Turns out a three month break does wonders for the health of a squad! With Kane and Son back fit, the back end of 2019-20 held a degree of promise. Results were generally good. Performances were... less so. The 0-0 with Bournemouth was about as poorly as Tottenham have played in memory, with the Sheffield United defeat not far behind. Tottenham's attack created very little during this spell: in six of nine games the took ten or fewer shots or failed to create more than one expected goal. To brazenly defy expected goals they also took the lead three times via an own goal. The only game in which the result happily matched expectation was the 2-1 derby win over Arsenal. The defence was sturdier--in four of nine games the expected goals allowed was less than one--and in two further games it was just a shade over. Overall, it's impossible to be analytically inclined and generally happy with how performances have developed across the Mourinho reign, but the better post-break results certainly eased pressure that had been building, even this quickly into his tenure. Style Undoubtedly the style of play is very different. After five hard years, the Pochettino press had already somewhat waned a deal of time before his departure:

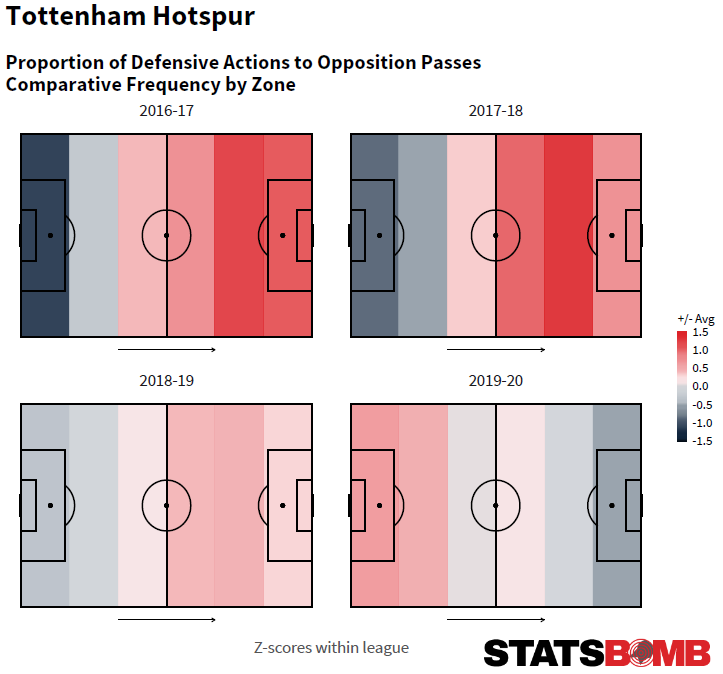

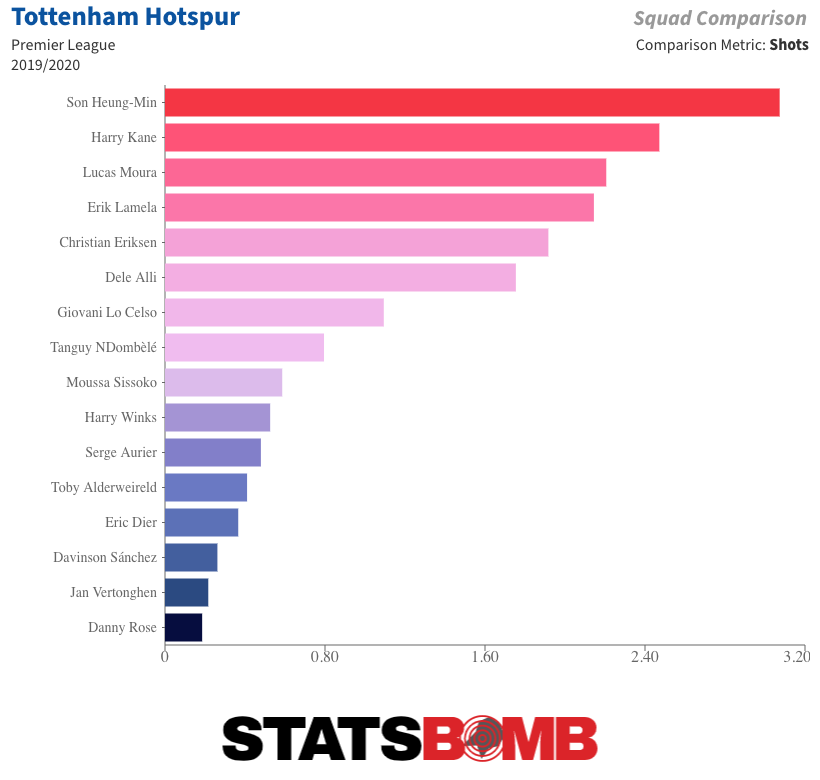

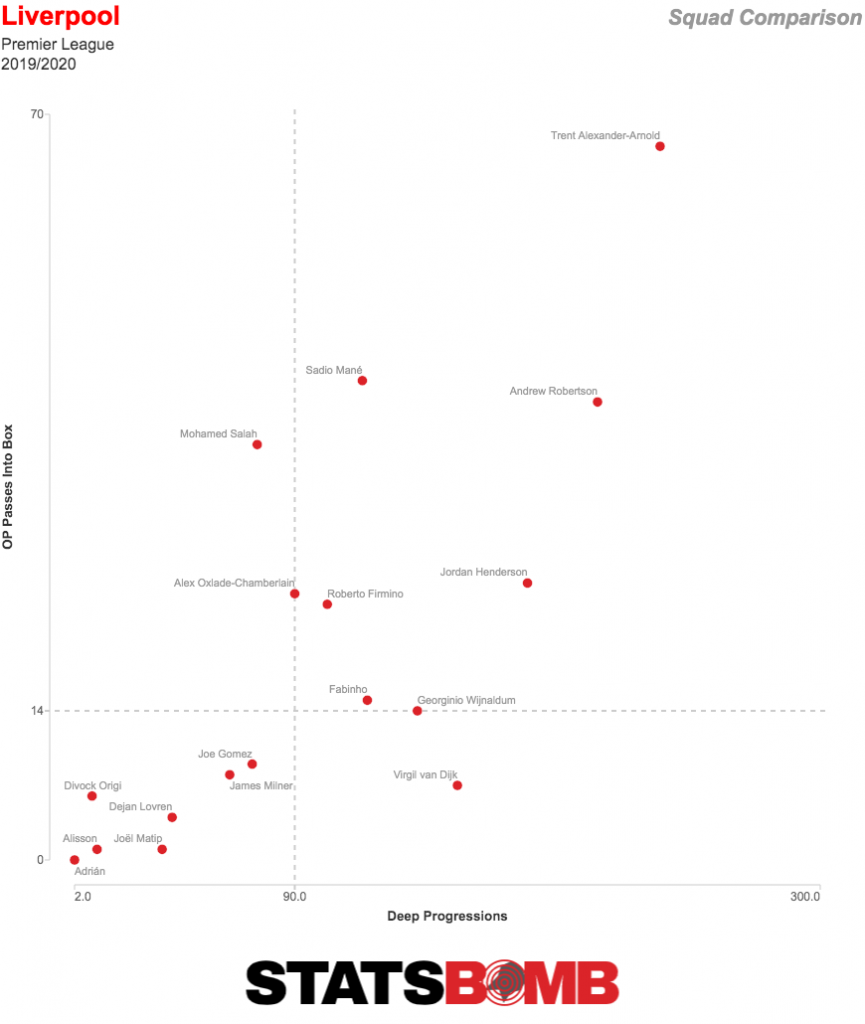

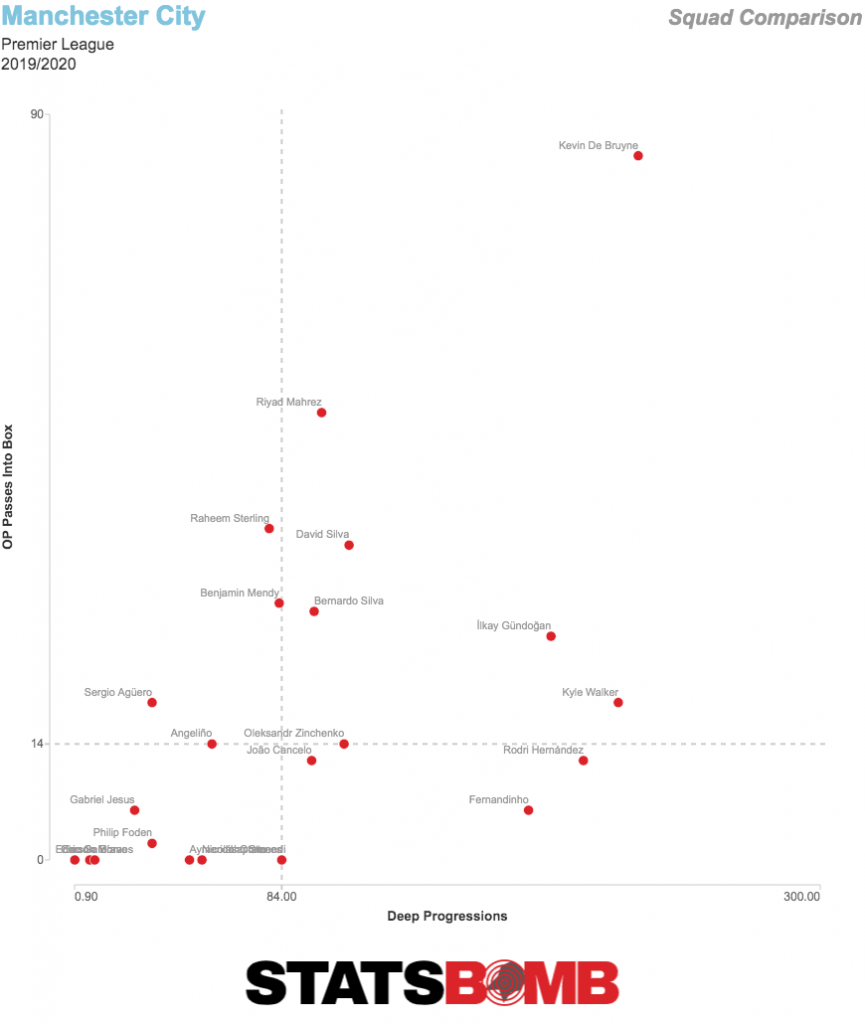

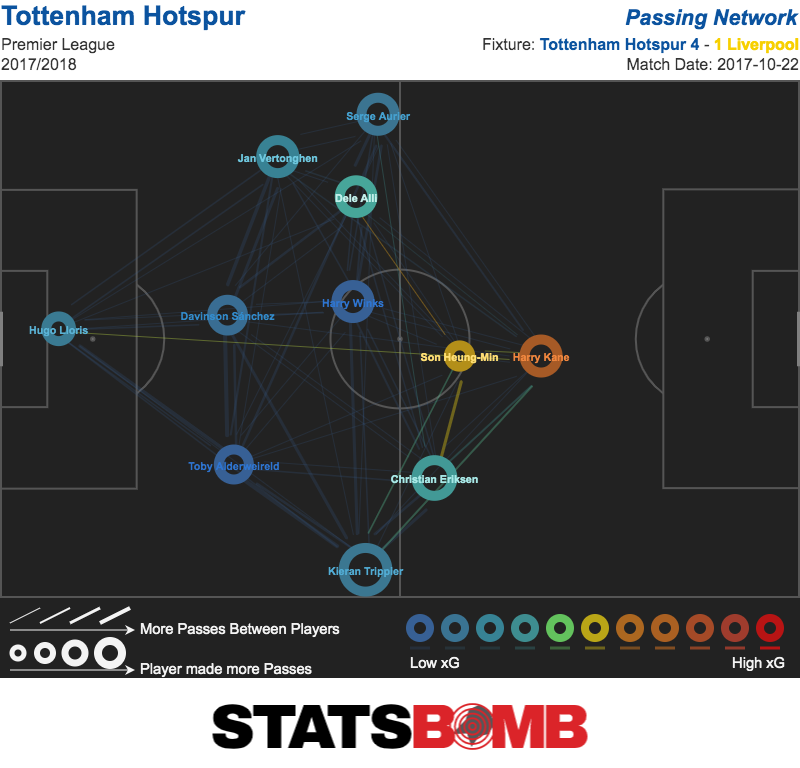

Well, the first thing that went wrong was that the metrics got worse. The second thing that went wrong was the results were terrible. The third thing that went wrong was Mauricio Pochettino was fired. Really, this was all just one large thing that engulfed the club in a manner befitting of a 22-minute segment in a documentary. There was no way around it though, Tottenham had three wins from twelve in the league, had deserved no more from their performances and had been annihilated 7-2 in the Champions League by a promising German side, Bayern Munich. Enter Mourinho. On the surface the 26 league games Mourinho has overseen have been just about good enough. Tottenham got 45 points (65 point pace) which ranked fourth and their goal difference of +13 ranked fourth too. What that conceals is that Mourinho’s tenure has already been through three distinct acts, and the main hope for fans is that the most recent of those acts involved winning more frequently than not. It's also challenging to get used to a Tottenham team that plays very different football to that of the best of Pochettino--and by the time of his departure, despite the Champions League run, that best was a long time passed. Act 1: Duration: 8 games in 2019 Results: 5-1-2 GD: +6 xG: +5 Note: xG Against at 0.65 per game is best in the league The start for Mourinho was promising but didn't come without disappointments. Defeats against his two former clubs, Manchester United (2-1 at Old Trafford in a low event game decided by a Marcus Rashford penalty) and Chelsea (2-0 at home, a Willian penalty sealing the deal soon after renowned hatchet man Son Heung-min was sent off) were classics in the "create nothing, try not to lose" Mourinho canon. Elsewhere the team won five from six before the turn of the new year and certain metrics shone brightly; in defence, the team was giving up very few shots, specifically in good, central dangerous locations. Occasional penalties apart, Tottenham were repelling all. Yes, the schedule was quite kind, but there was a win over Wolves in there too alongside more straightforward victories against lower ranked teams such as Burnley, West Ham, Brighton and Bournemouth. Something to build on? Act 2: Duration: 9 games in a world gradually learning about coronaviruses Results: 3-2-4 GD: +0 xG: -5 Note: xG Against at 1.82 per game is second worst in the whole league The second act was not-so-good. In fact it was downright bad. The schedule bit a little with defeats against Southampton (1-0, created nothing), Liverpool (1-0, played surprisingly well, at least in the second half), Chelsea (again 2-1, this time created nothing, deserved nothing) and Wolves (3-2, overpowered late on, gave it away). There was also a 2-0 win against Manchester City which was as equally improbable as the 2-2 draw earlier in the season at the Etihad. In both games City did enough to win multiple games but somehow couldn't get anything to stick. But the underlying concern came in the same form that had looked so promising weeks before. The defence faltered horribly, moving from league best to nearly league worst and in every one of these nine games Tottenham allowed xG worth between 1.4 to 3.7 per game. They didn't have a single defensively secure game all through and were averaging 16 shots per game against. Really grim stuff. Tottenham also departed the Champions League after being significantly worse than RB Leipzig and lost in the FA Cup on penalties to Norwich, the kind of result that is hard to explain away when you know, deep down, the manager would like to nab a trophy and quick. When the curtains came down on football, they had lost five out of six, and were limping along having been left weakened by injuries to key men such as Kane and Son. Act 3: Duration: 9 games, summer is here and so is your Premier League finale Results: 5-3-1 GD: +7 xG: -2 Note: xG For is 15th, xG Against is 6th Turns out a three month break does wonders for the health of a squad! With Kane and Son back fit, the back end of 2019-20 held a degree of promise. Results were generally good. Performances were... less so. The 0-0 with Bournemouth was about as poorly as Tottenham have played in memory, with the Sheffield United defeat not far behind. Tottenham's attack created very little during this spell: in six of nine games the took ten or fewer shots or failed to create more than one expected goal. To brazenly defy expected goals they also took the lead three times via an own goal. The only game in which the result happily matched expectation was the 2-1 derby win over Arsenal. The defence was sturdier--in four of nine games the expected goals allowed was less than one--and in two further games it was just a shade over. Overall, it's impossible to be analytically inclined and generally happy with how performances have developed across the Mourinho reign, but the better post-break results certainly eased pressure that had been building, even this quickly into his tenure. Style Undoubtedly the style of play is very different. After five hard years, the Pochettino press had already somewhat waned a deal of time before his departure:  Despite clear mentions of pressing in the Amazon documentary, it doesn't really come out in the metrics. Tottenham may still work hard, but not as high up the pitch as before. The signing of Steven Bergwijn defines what Mourinho wants from his non-Kane attackers. Quick and able to stretch defences especially on the break, Bergwijn's talents categorise neatly alongside Lucas Moura and Son. Midfield has been a problem for Tottenham for a number of seasons, and Mourinho's solution was somewhat creative: try to bypass it.

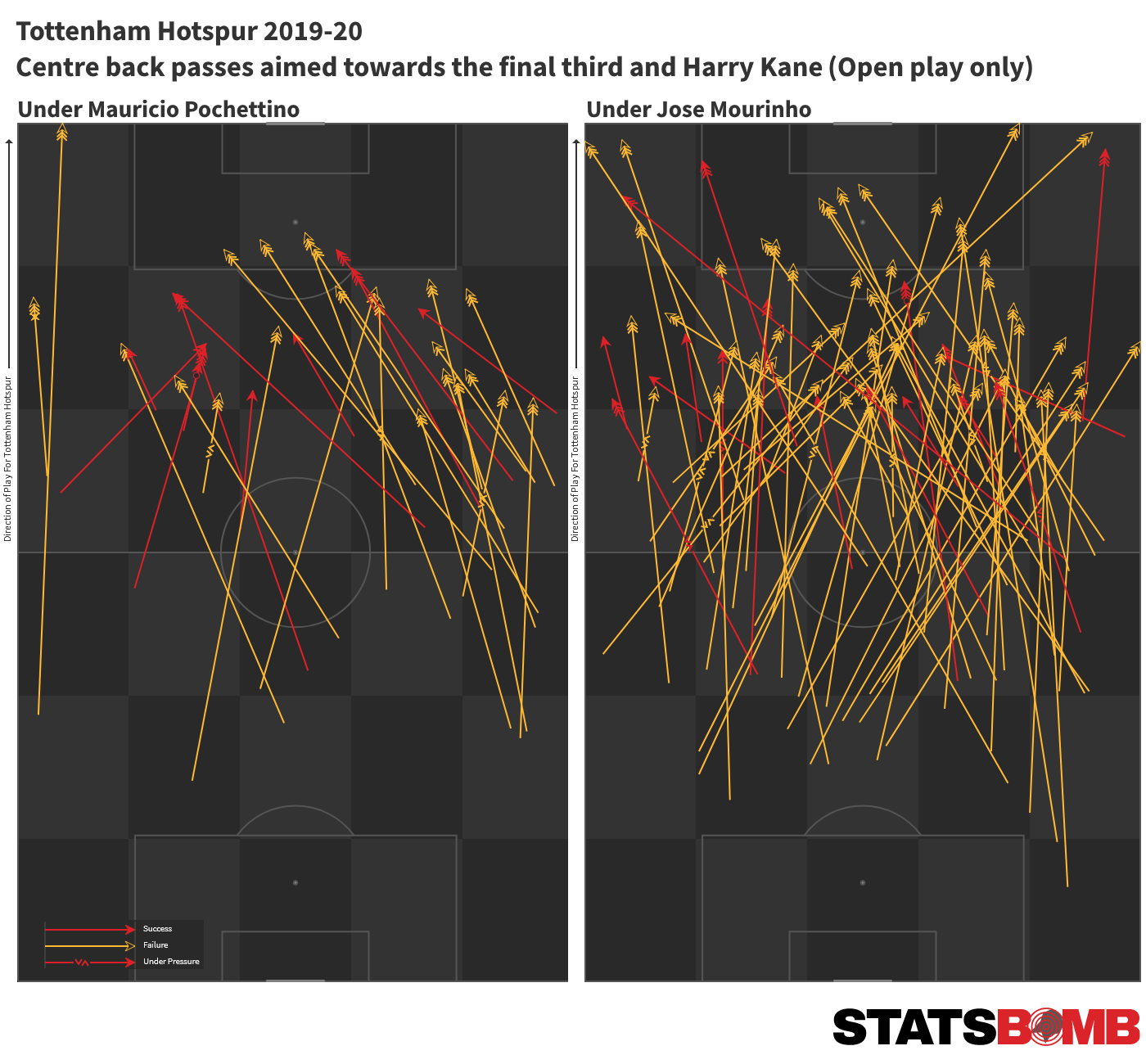

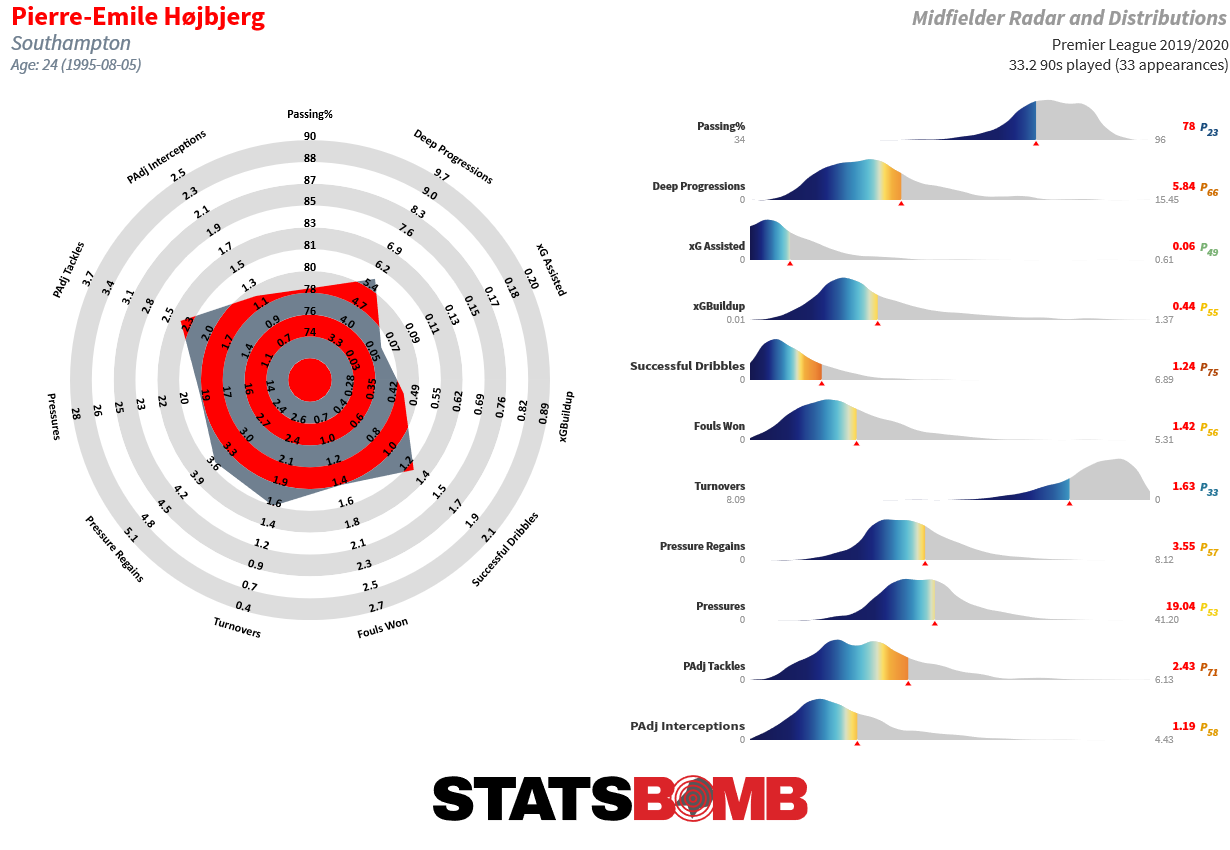

Despite clear mentions of pressing in the Amazon documentary, it doesn't really come out in the metrics. Tottenham may still work hard, but not as high up the pitch as before. The signing of Steven Bergwijn defines what Mourinho wants from his non-Kane attackers. Quick and able to stretch defences especially on the break, Bergwijn's talents categorise neatly alongside Lucas Moura and Son. Midfield has been a problem for Tottenham for a number of seasons, and Mourinho's solution was somewhat creative: try to bypass it.  The change here from the steadier possession game deployed by Pochettino to a more direct targeted passing system was notable. The graphic shows balls aimed at Kane from centre backs in open play, and this type of pass went from three per game under Pochettino with a huge skew towards Alderweireld (over two-thirds of these passes were from him) to over five per game under Mourinho, with all the centre backs looking for this ball. The other attackers saw a similar uptick in receiving targeted long passes too, with Son, Lucas and eventually Bergwijn under Mourinho combining to receive nearly six of these passes per game up from three, and again a large skew away from just Alderweireld towards all centre backs. Both goalkeepers looked for similar out balls too, with a large rise in any keeper clearance (dead ball or otherwise) aimed at the forwards. This is also where the signing of Matt Doherty is interesting, as he's shown himself to be well capable in competing for long, high balls and taking up an advanced position -- Serge Aurier already takes up similar roles but hasn't the aerial prowess to dominate opposing full backs. Doherty may well be able to do this and provide flicks and nod downs, to help release Tottenham's speedy forwards. It's not total football, but it could well be part of the Mourinho plan. Personnel The eternal dance at Tottenham between Chairman Daniel Levy and incumbent managers regarding player acquisition appears so far to not be taking place with Mourinho. Players that have been recruited are not wildly expensive or apparently indulgent and may well be better than the raw detail suggests. The talent within the Tottenham squad is impossible to deny, from World Cup winner Hugo Lloris in goal right through to Kane up front. But supporting roles have waned over time, and the signings of Pierre-Emile Højbjerg and Doherty in particular, appear to show the intent to solidify key positions to perhaps allow the gifted attackers to flourish. There are distinct "do everything, but just a bit" vibes to Højbjerg's metrics in particular, but perhaps that's what this team needs: consistency and stability.

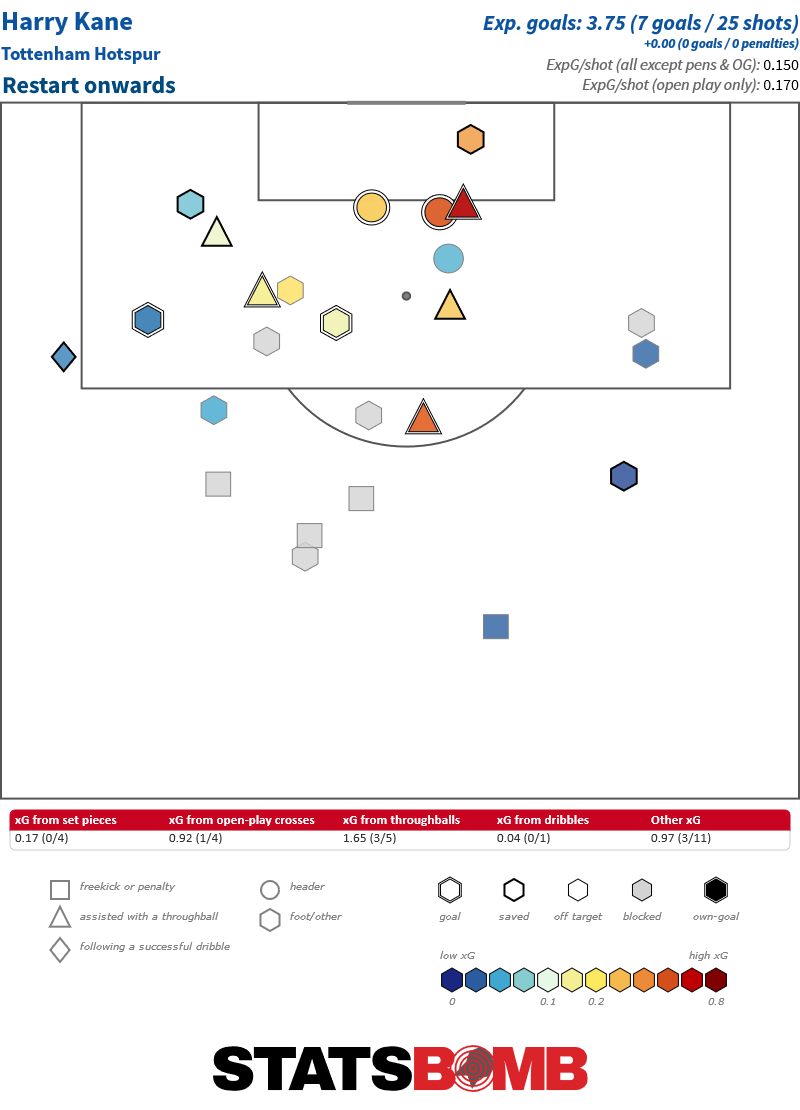

The change here from the steadier possession game deployed by Pochettino to a more direct targeted passing system was notable. The graphic shows balls aimed at Kane from centre backs in open play, and this type of pass went from three per game under Pochettino with a huge skew towards Alderweireld (over two-thirds of these passes were from him) to over five per game under Mourinho, with all the centre backs looking for this ball. The other attackers saw a similar uptick in receiving targeted long passes too, with Son, Lucas and eventually Bergwijn under Mourinho combining to receive nearly six of these passes per game up from three, and again a large skew away from just Alderweireld towards all centre backs. Both goalkeepers looked for similar out balls too, with a large rise in any keeper clearance (dead ball or otherwise) aimed at the forwards. This is also where the signing of Matt Doherty is interesting, as he's shown himself to be well capable in competing for long, high balls and taking up an advanced position -- Serge Aurier already takes up similar roles but hasn't the aerial prowess to dominate opposing full backs. Doherty may well be able to do this and provide flicks and nod downs, to help release Tottenham's speedy forwards. It's not total football, but it could well be part of the Mourinho plan. Personnel The eternal dance at Tottenham between Chairman Daniel Levy and incumbent managers regarding player acquisition appears so far to not be taking place with Mourinho. Players that have been recruited are not wildly expensive or apparently indulgent and may well be better than the raw detail suggests. The talent within the Tottenham squad is impossible to deny, from World Cup winner Hugo Lloris in goal right through to Kane up front. But supporting roles have waned over time, and the signings of Pierre-Emile Højbjerg and Doherty in particular, appear to show the intent to solidify key positions to perhaps allow the gifted attackers to flourish. There are distinct "do everything, but just a bit" vibes to Højbjerg's metrics in particular, but perhaps that's what this team needs: consistency and stability.  Will it work? Getting Højbjerg in as a likely guaranteed starter means we're unlikely to see Harry Winks and Moussa Sissoko start many games together with Giovani Lo Celso already the passing heartbeat of the side picked ahead of them. Doherty's arrival allows Aurier to depart and locks down one position. The attacking midfield band is rich with Dele Alli, Bergwijn, Moura, Son and Erik Lamela competing for a maximum of three positions. What of Tanguy Ndombélé? I'll plead the fifth, thanks. It's possible that the Frenchman's inability to nail down a starting place is indicative of the slightly altered transfer focus, as his signing combined with an investment in Jack Clarke and Ryan Sessegnon that is a long way off bearing fruit means £100m of summer 2019 purchases are not yet directly impacting the first team. Doherty and Højbjerg scope out at around £30m (and books are balancing a little more once Kyle Walker-Peters' departure is factored in) and will likely play every week. Getting purchases into the team and contributing counts for a lot. There are noises that more players could arrive, most notably a rotational striker, but in Covid-19 world, it's likely to be more book-balancing than big purchases, so it also depends who is on the outs. With football finishing only a month ago, we have fresh answers to long term questions. Whether Kane could refind something near to his best form after a six month break to recover from his latest injury appeared to be answered in the affirmative by a tidy finishing streak. To the casual eye he looked more dynamic than before, and whatever the truth is of his long term mobility and the impact of injuries on him, the work that he's put into his finishing over the course of many years will likely carry him well into his latter career. It's also possible that there's a bias generated in seeing him score three goals from five throughball shots as it's never been an area in which he's been wildly prolific (10 goals from 31 such shots in the league across the previous four seasons). Still: at 2.5 shots per 90, albeit for a ten shot a game team, he needs the finishing to stay sharp to get the totals up and mini runs such as this will not persist long term:

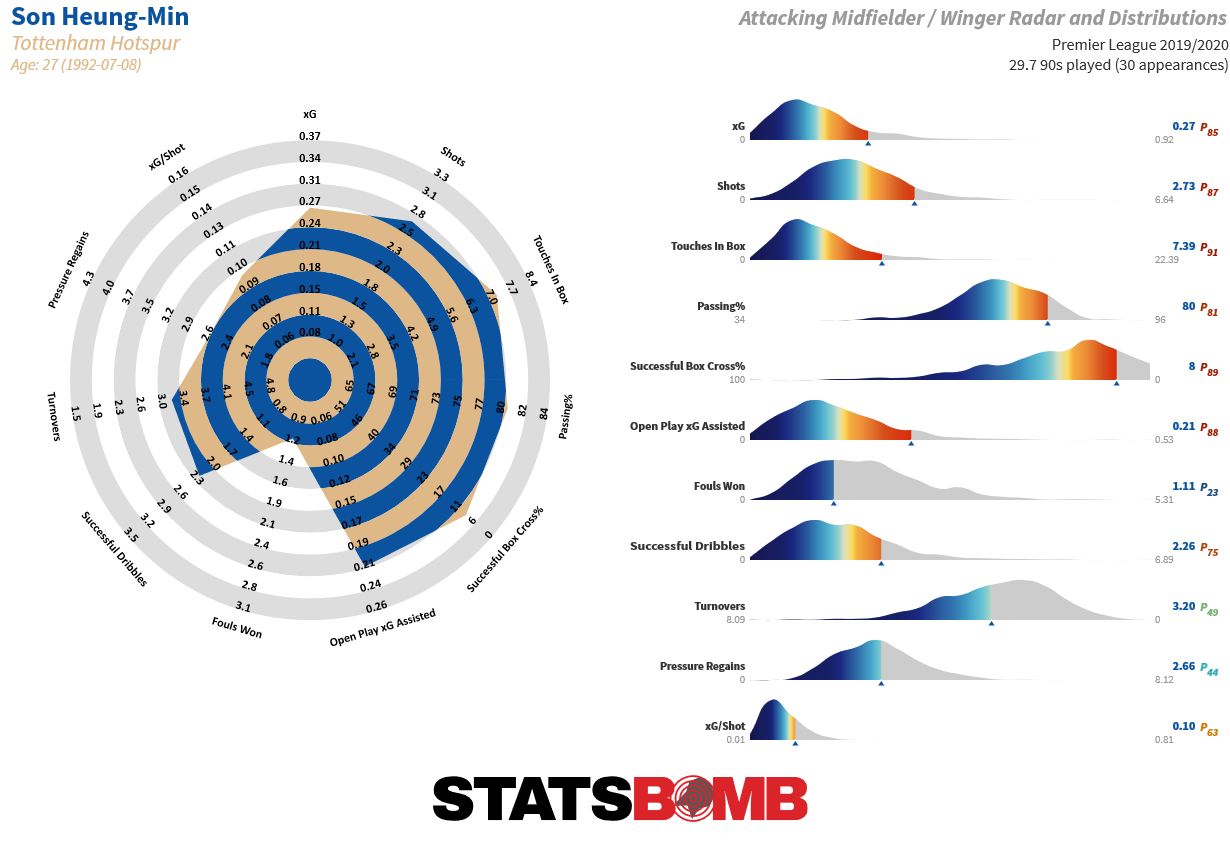

Will it work? Getting Højbjerg in as a likely guaranteed starter means we're unlikely to see Harry Winks and Moussa Sissoko start many games together with Giovani Lo Celso already the passing heartbeat of the side picked ahead of them. Doherty's arrival allows Aurier to depart and locks down one position. The attacking midfield band is rich with Dele Alli, Bergwijn, Moura, Son and Erik Lamela competing for a maximum of three positions. What of Tanguy Ndombélé? I'll plead the fifth, thanks. It's possible that the Frenchman's inability to nail down a starting place is indicative of the slightly altered transfer focus, as his signing combined with an investment in Jack Clarke and Ryan Sessegnon that is a long way off bearing fruit means £100m of summer 2019 purchases are not yet directly impacting the first team. Doherty and Højbjerg scope out at around £30m (and books are balancing a little more once Kyle Walker-Peters' departure is factored in) and will likely play every week. Getting purchases into the team and contributing counts for a lot. There are noises that more players could arrive, most notably a rotational striker, but in Covid-19 world, it's likely to be more book-balancing than big purchases, so it also depends who is on the outs. With football finishing only a month ago, we have fresh answers to long term questions. Whether Kane could refind something near to his best form after a six month break to recover from his latest injury appeared to be answered in the affirmative by a tidy finishing streak. To the casual eye he looked more dynamic than before, and whatever the truth is of his long term mobility and the impact of injuries on him, the work that he's put into his finishing over the course of many years will likely carry him well into his latter career. It's also possible that there's a bias generated in seeing him score three goals from five throughball shots as it's never been an area in which he's been wildly prolific (10 goals from 31 such shots in the league across the previous four seasons). Still: at 2.5 shots per 90, albeit for a ten shot a game team, he needs the finishing to stay sharp to get the totals up and mini runs such as this will not persist long term:  As important is the form of Son. A beacon of consistency in the aggregate throughout the good times, and not-so-good times, he has now registered four consecutive seasons oscillating close to a combined 0.7 per 90 for goals and assists, most usually ahead of expectation thanks to his versatile finishing. He can blow hot and cold at times from week to week, but when on-song, is as devastating an attacking midfielder as there is in the league:

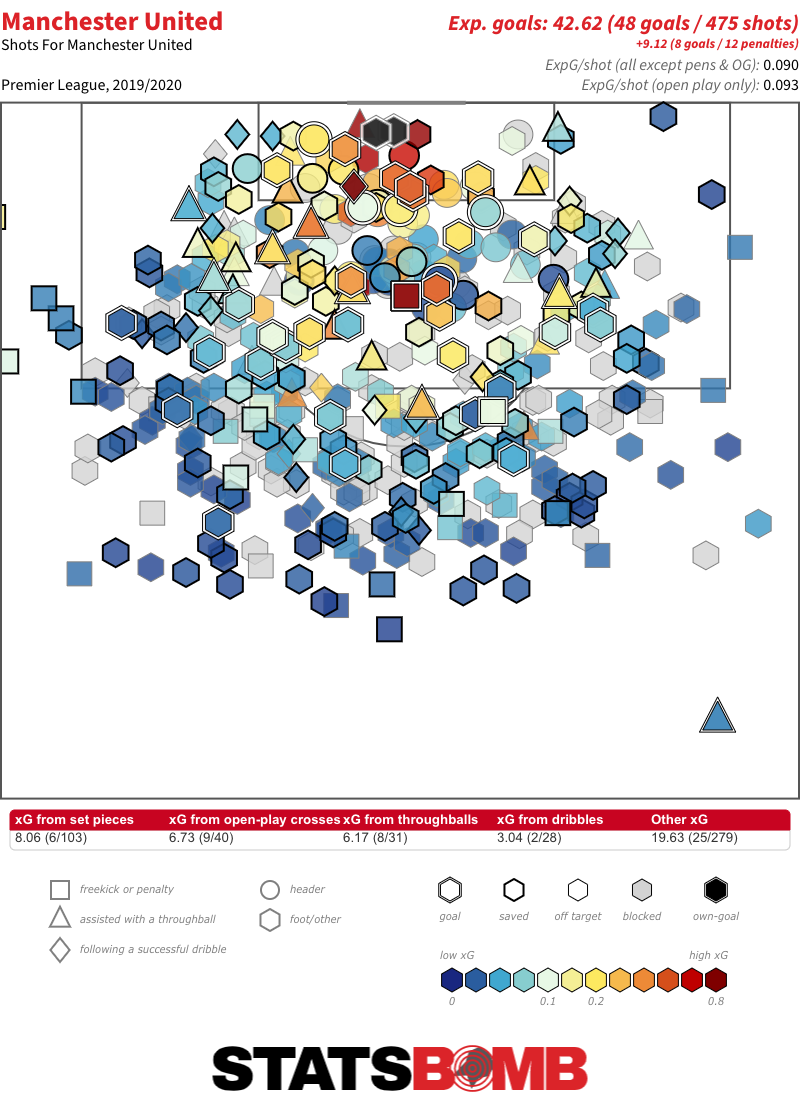

As important is the form of Son. A beacon of consistency in the aggregate throughout the good times, and not-so-good times, he has now registered four consecutive seasons oscillating close to a combined 0.7 per 90 for goals and assists, most usually ahead of expectation thanks to his versatile finishing. He can blow hot and cold at times from week to week, but when on-song, is as devastating an attacking midfielder as there is in the league:  Projection Everything from a metric perspective at Tottenham has pointed downwards since the end of 2017-18, so the first thing to try and do is reverse that slide. Can Mourinho do that? His Zlatan-powered first Manchester United season was a legitimately dominant shooting team with a finishing problem, so there's a blueprint to get to a position of strength. The following season United finished second with 81 points despite less impressive metrics and season three is a well worn trail now. It's just about possible to give the benefit of the doubt and offer a pass for 2019-20 given weird circumstances and a mid-season appointment, but Tottenham will need to start well to keep any goodwill in the tank, and the Amazon documentary is dropping and building a whole new set of memes and storylines just as this season emerges. It's the Jose Mourinho Show again, and he needs to show he can still provide an above average return for his salary. Mourinho-era metrics don't yet offer solid encouragement, given how variable they have been. Teams with minus expected goal differences and minus shot counts simply don't earn high league positions in this league. The Sporting Index projection has Arsenal and Tottenham in the fifth and sixth slots, but no more than a result or two from below and significantly further away from Chelsea and Manchester United in the backend of the top four. Somewhere in the top four does represent the very best outcome, and a plan realised, but it is not the most likely outcome at all. However, if Tottenham can improve metrics and somehow stay in range of such an outcome deep into the season, all good, if not, then the Mourinho project may founder ahead of any expected three year timeline.

Projection Everything from a metric perspective at Tottenham has pointed downwards since the end of 2017-18, so the first thing to try and do is reverse that slide. Can Mourinho do that? His Zlatan-powered first Manchester United season was a legitimately dominant shooting team with a finishing problem, so there's a blueprint to get to a position of strength. The following season United finished second with 81 points despite less impressive metrics and season three is a well worn trail now. It's just about possible to give the benefit of the doubt and offer a pass for 2019-20 given weird circumstances and a mid-season appointment, but Tottenham will need to start well to keep any goodwill in the tank, and the Amazon documentary is dropping and building a whole new set of memes and storylines just as this season emerges. It's the Jose Mourinho Show again, and he needs to show he can still provide an above average return for his salary. Mourinho-era metrics don't yet offer solid encouragement, given how variable they have been. Teams with minus expected goal differences and minus shot counts simply don't earn high league positions in this league. The Sporting Index projection has Arsenal and Tottenham in the fifth and sixth slots, but no more than a result or two from below and significantly further away from Chelsea and Manchester United in the backend of the top four. Somewhere in the top four does represent the very best outcome, and a plan realised, but it is not the most likely outcome at all. However, if Tottenham can improve metrics and somehow stay in range of such an outcome deep into the season, all good, if not, then the Mourinho project may founder ahead of any expected three year timeline.

If you're a club, media or gambling entity and want to know more about what StatsBomb can do for you, please contact us at Sales@StatsBomb.com We also provide education in this area, so if this taste of football analytics sparked interest, check out our Introduction to Football Analytics course Follow us on twitter in English and Spanish and also on LinkedIn

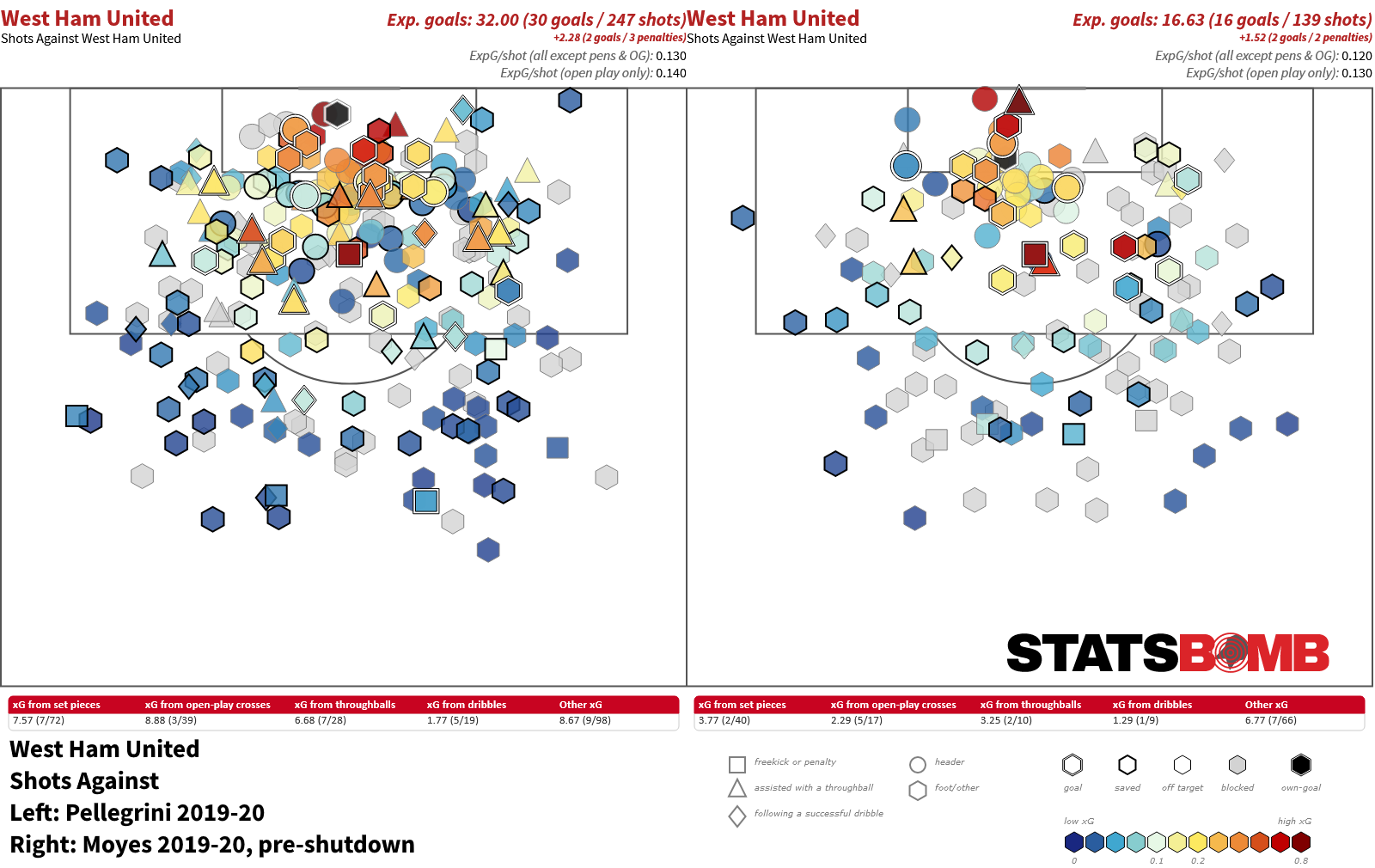

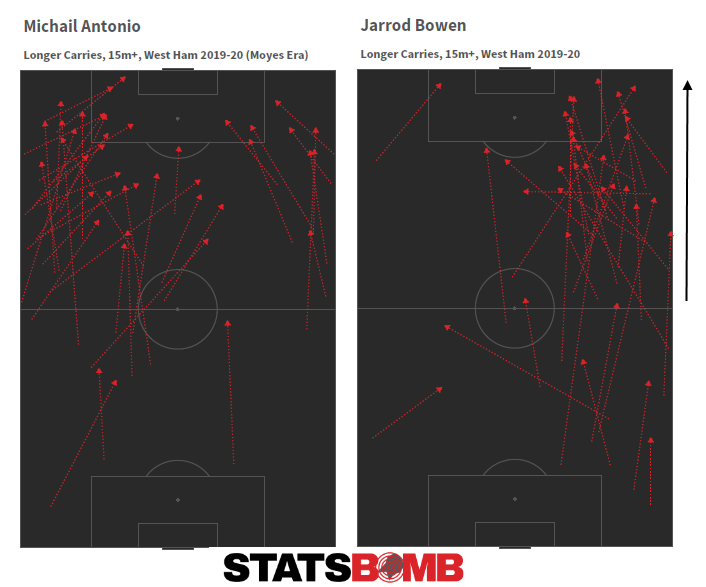

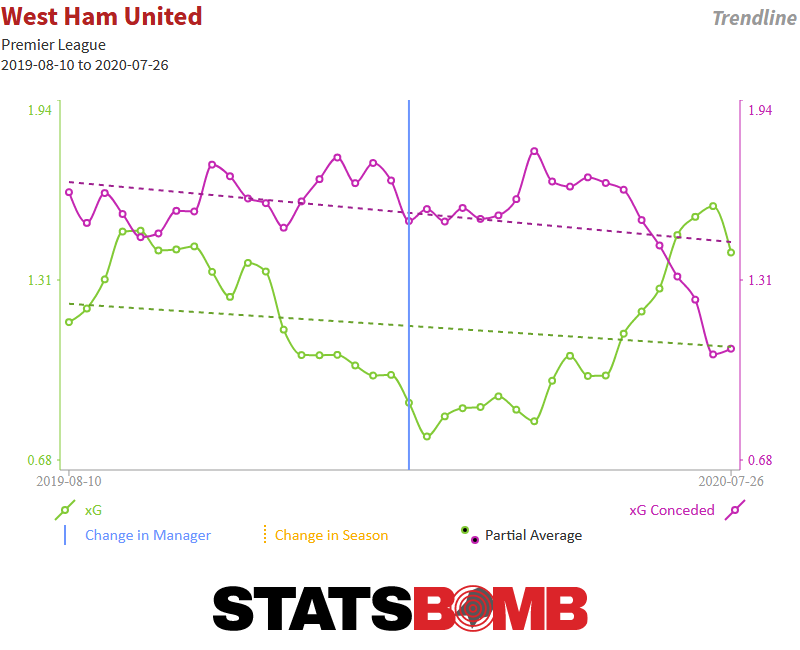

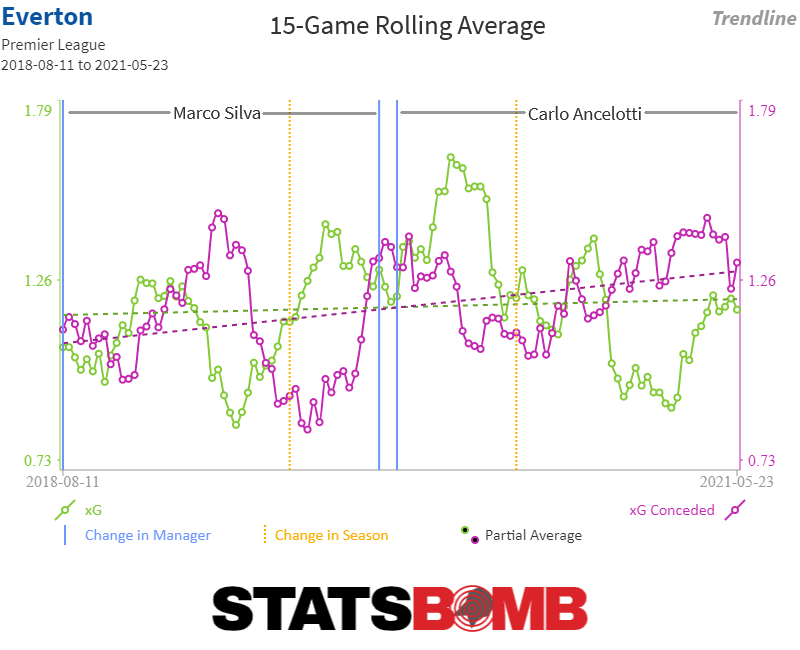

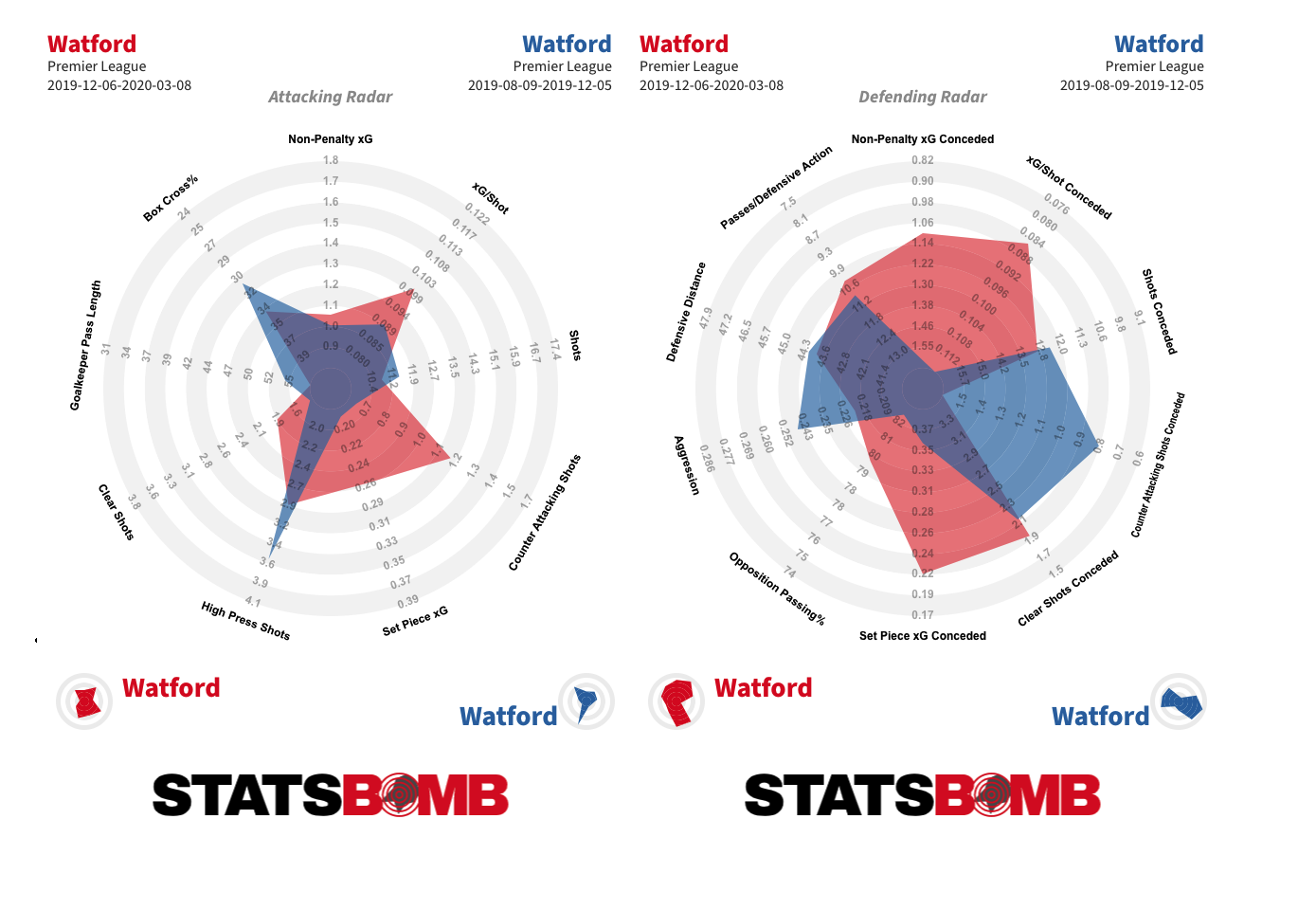

In 2016-17, West Ham finished 11th with 45 points with below par metrics that roughly merited their points haul. By the start of the following November, Slaven Bilić had steered them downwards to 18th with bad metrics and a worse goal difference. He promptly exited and David Moyes was hired. Moyes did nothing for the underlying metrics (they were fairly stable at -0.5 xG per game across both managers) but eked out just enough from his team to keep them up. Moyes may have felt some displeasure at not being handed a longer tenure at that point but objectively, despite fulfilling the first remit of keeping the team in the Premier League, only a very charitable-minded review could say that he had improved his team. Mauricio Pellegrini was hired instead. In 2018-19, West Ham finished 10th with 52 points with below par metrics that did not merit their points haul. By end of the following December, Manuel Pellegrini had steered them downwards to 17th with a bad goal difference and worse metrics. He promptly exited and David Moyes was hired. Moyes did nothing for the underlying metrics (they were fairly stable at -0.6 xG per game across both managers) then the world fell apart, everyone stopped playing football and stayed in the house for three months. Pellegrini’s main issue had been a horribly open defence: the value of the shots they were giving up was higher than any other team in the league (0.13 xG/shot) and Moyes, ever the pragmatist, set about shutting that down. In the ten games before the suspension of play, West Ham recorded the lowest PPDA (pass per defensive action) value in the league (16.2). They had the deepest average defensive distance (39.8m). They were the least aggressive pressers of opponent ball receipts (19%). They had less of the ball than any other team. Translation for all that? They sat off. It had barely any effect though, as opponent shot quality remained high (0.12 xG/shot). Under either manager opponents could get nice and deep into the penalty box and grab good shots:  It’s an open question what may have happened to West Ham’s season had the viral intervention not occurred. The team were in sixteenth on 27 points, level with Watford and Bournemouth in seventeenth and eighteenth and with nine games left to rescue themselves from possible relegation. It's also an open question as to how reliable the form is of this concentrated post-lockdown period. Oddly, since leaving Everton and starting at Manchester United, Moyes has had four further managerial tenures, and apart from the summer of 2015 while in charge of Real Sociedad, the Covid break has been the only time he has had an extended period as a manager outside the grind of regular in season games. And given three months to prepare, Moyes managed to hit upon something that worked. The initial Moyes period did have the misfortune of some schedule stacking--they faced Liverpool twice, and Manchester City-- so there is room for some caution when considering the apparent improvement the team made, but he chopped and changed his formations in that early run, and post-lockdown stuck with a 4-2-3-1. As the season wound up, his starting eleven became more consistent too: Łukasz Fabiański in goal, a back four of Ryan Fredricks, Issa Diop, Angelo Ogbonna, Aaron Cresswell, Declan Rice and Tomáš Souček sitting, Pablo Fornals or Manuel Lanzini left, Jarrod Bowen right, Mark Noble's aging legs parked upfield as an attacking midfielder, at least in name, and Michail Antonio up front. This left a selection of expensive potential game-changers often manning the bench. Sébastien Haller, Andriy Yarmolenko and Felipe Anderson's combined cost was around £100m and they watched a good deal of football in those final weeks, occasionally, pitching in late on in games. The players that benefited most from Moyes' June reboot were the two January signings, Bowen and Souček and converted striker Antonio. Souček is a fascinating player for a central midfielder as despite many column inches being spent on the possibility of his midfield partner Rice becoming a centre back, at least from a data perspective he looks to have more centre back aligned tools. No central midfielder in the league got anywhere near his 5.1 aerial wins per 90 (next best was Phillip Billing at 3.4). He's also useful at the other end of the pitch as a goal threat in open play and from set-pieces having scored 30 goals in his last two seasons at Slavia Prague. He's added three more since arriving in England. He's a curious passer for a defensive midfielder too. Keeping the ball on the deck and playing short, he's just about secure enough (he completed over 90% of passes, still less than Rice's 95%) but as soon as he puts the ball forward and in the air it drops to 40% (down from 60% at Slavia). Quick analysis suggests that quite a lot of these failed attempts are out balls aimed at Antonio or Bowen, and Rice scopes out better at those too. Add Noble into the mix, who nominally played in the middle of the attacking midfield band as the season drew to a close, but effectively sat a lot closer to the other two defensive midfielders, and we see a clear strategy--find Antonio or Bowen if you can--that is effective only sporadically. Just 28% of high and longer passes from their own half forward and into the opponent half are finding their intended target. All this feeds into the idea of what you can get from Bowen and Antonio. Each is effective at carrying the ball deep into opposition territory (as is Felipe Anderson, moreso even, across the whole season, he ranks second behind Adama Traoré for these long carries) and are a danger to the opponent's goal:

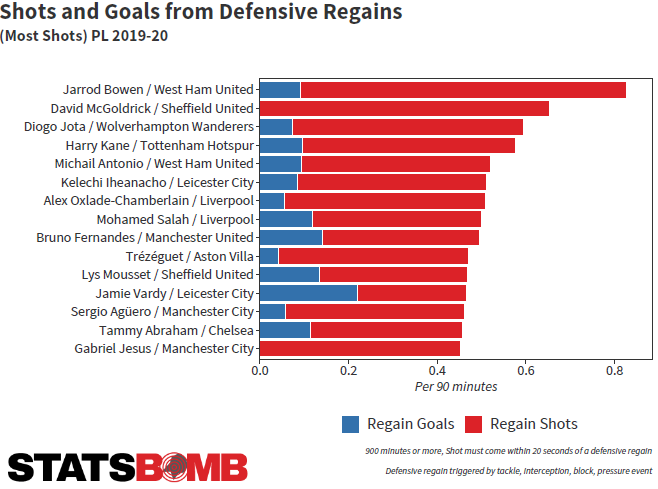

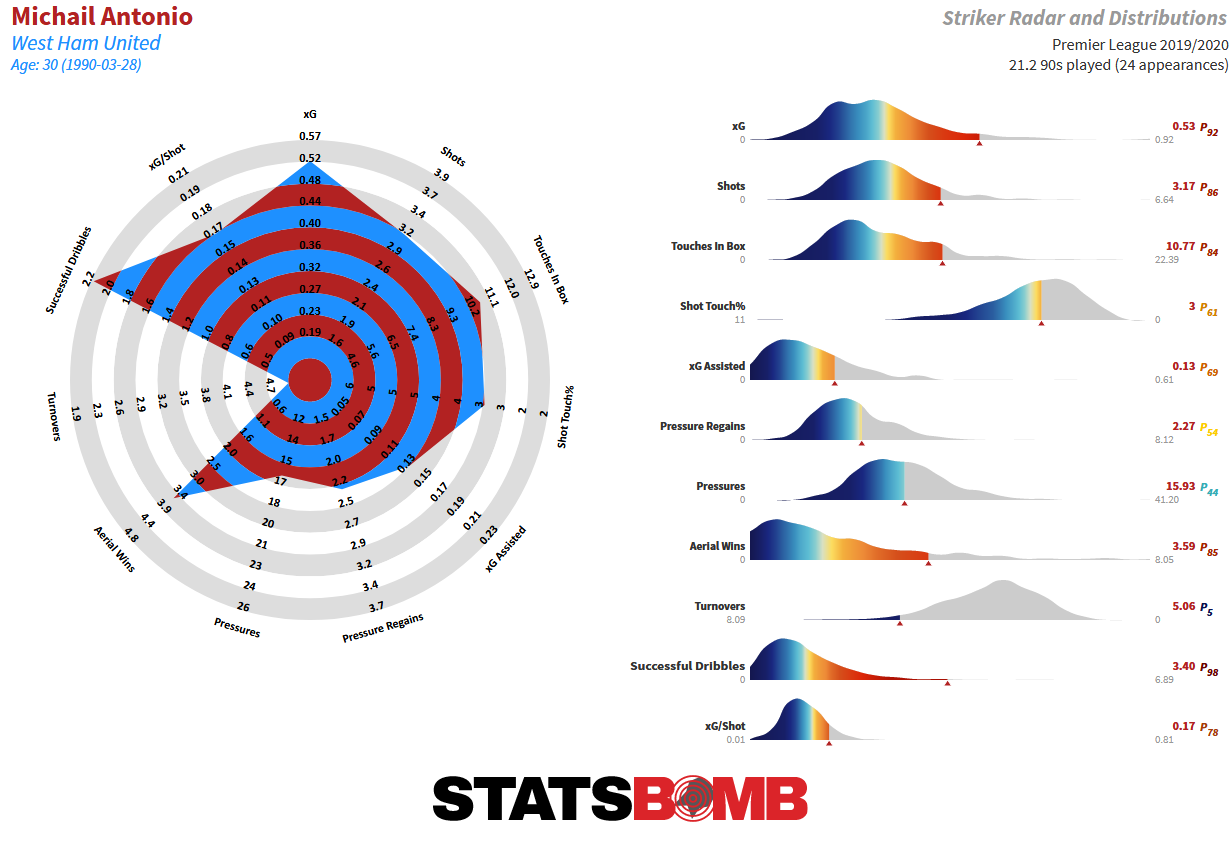

It’s an open question what may have happened to West Ham’s season had the viral intervention not occurred. The team were in sixteenth on 27 points, level with Watford and Bournemouth in seventeenth and eighteenth and with nine games left to rescue themselves from possible relegation. It's also an open question as to how reliable the form is of this concentrated post-lockdown period. Oddly, since leaving Everton and starting at Manchester United, Moyes has had four further managerial tenures, and apart from the summer of 2015 while in charge of Real Sociedad, the Covid break has been the only time he has had an extended period as a manager outside the grind of regular in season games. And given three months to prepare, Moyes managed to hit upon something that worked. The initial Moyes period did have the misfortune of some schedule stacking--they faced Liverpool twice, and Manchester City-- so there is room for some caution when considering the apparent improvement the team made, but he chopped and changed his formations in that early run, and post-lockdown stuck with a 4-2-3-1. As the season wound up, his starting eleven became more consistent too: Łukasz Fabiański in goal, a back four of Ryan Fredricks, Issa Diop, Angelo Ogbonna, Aaron Cresswell, Declan Rice and Tomáš Souček sitting, Pablo Fornals or Manuel Lanzini left, Jarrod Bowen right, Mark Noble's aging legs parked upfield as an attacking midfielder, at least in name, and Michail Antonio up front. This left a selection of expensive potential game-changers often manning the bench. Sébastien Haller, Andriy Yarmolenko and Felipe Anderson's combined cost was around £100m and they watched a good deal of football in those final weeks, occasionally, pitching in late on in games. The players that benefited most from Moyes' June reboot were the two January signings, Bowen and Souček and converted striker Antonio. Souček is a fascinating player for a central midfielder as despite many column inches being spent on the possibility of his midfield partner Rice becoming a centre back, at least from a data perspective he looks to have more centre back aligned tools. No central midfielder in the league got anywhere near his 5.1 aerial wins per 90 (next best was Phillip Billing at 3.4). He's also useful at the other end of the pitch as a goal threat in open play and from set-pieces having scored 30 goals in his last two seasons at Slavia Prague. He's added three more since arriving in England. He's a curious passer for a defensive midfielder too. Keeping the ball on the deck and playing short, he's just about secure enough (he completed over 90% of passes, still less than Rice's 95%) but as soon as he puts the ball forward and in the air it drops to 40% (down from 60% at Slavia). Quick analysis suggests that quite a lot of these failed attempts are out balls aimed at Antonio or Bowen, and Rice scopes out better at those too. Add Noble into the mix, who nominally played in the middle of the attacking midfield band as the season drew to a close, but effectively sat a lot closer to the other two defensive midfielders, and we see a clear strategy--find Antonio or Bowen if you can--that is effective only sporadically. Just 28% of high and longer passes from their own half forward and into the opponent half are finding their intended target. All this feeds into the idea of what you can get from Bowen and Antonio. Each is effective at carrying the ball deep into opposition territory (as is Felipe Anderson, moreso even, across the whole season, he ranks second behind Adama Traoré for these long carries) and are a danger to the opponent's goal:  Once they have the ball, there's a good chance you'll see a shot at the end of it. One of Bowen's known weaknesses is shot selection, but from enforced turnovers, his rate of getting shots (any kind) leads the league, with Antonio not that far behind: