It’s the most wonderful time of the (every fourth) year. It’s World Cup season folks. The footballing extravaganza that needs no introduction. Every four years die-hard fans and casuals alike join together to scream their heads off and root for teams they can barely find on a map and players who they claim they’d take a bullet for despite still not knowing quite how to pronounce their name. It’s great. That same specialness also makes the World Cup incredibly challenging for analytics. Most good analysis basically boils down to problem solving. How can we use the tools at our disposal to answer questions? What happens when we hit roadblocks along the way? How can we work around those? Can we use the tools we have? Can we build new tools? Is there a way to create shortcuts to a reasonable answer while also putting in the work to establish best practices for later? What new, unrelated questions arise that we will also have to work on answering? International football raises a whole host of problems to be solved that the club game simply doesn’t have. There are so few games, spread out over such a long time horizon that accurately gathering and applying specific information is next to impossible. By the time international teams have played enough games to say anything definitive about them, the players on the field have changed completely.

France: A Model of Changing Consistency

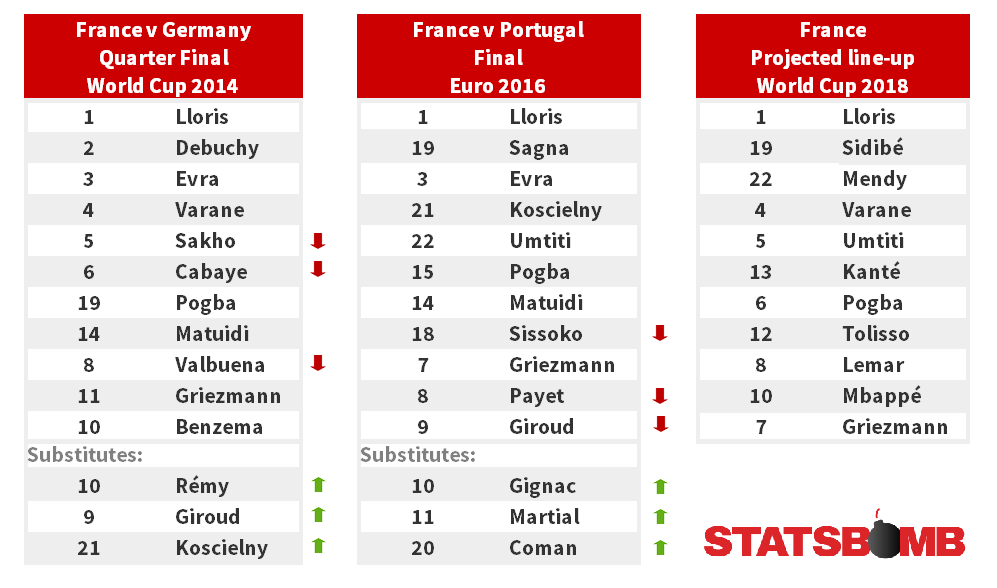

France is a good example of this. They seem like a team that has been relatively stable over the last World Cup cycle. Their manager has remained consistent. Didier Deschamps, for better or worse, has managed the squad for going on six years now. Their results have largely been good and getting better. After a promising group stage at the 2014 World Cup they lost in the quarterfinals to Germany. They followed that up by reaching the finals of the 2016 Euros at home. Now, they’re one of the favorites in Russia. Bookies place them only behind Brazil, Germany and Spain. France’s progress seems extremely tortoise like, taking slow, steady steps up the international ladder. Then you look at their lineups. This is how France lined up in their last game in the 2014 World Cup, their last game of the Euros, and a projected opening lineup for this World Cup. There’s a lot of change there.  Of the starting 11, only Paul Pogba, Antoine Griezmann and Hugo Lloris are constants. It’s also possible to make the argument Blaise Matuidi will start this time around, but at the same time the only reason Griezmann started in 2014 was that Franck Ribery was hurt in the run-up to the Cup. Additionally none of the three subs who appeared in the final two years ago are on this squad. A full three quarters of the back line has changed. Samuel Umtiti is the only holdover. Four starters from two years ago, Bacaray Sagna, Patrice Evra, Moussa Sissoko and Dmitri Payet aren’t even on the squad. That’s not unreasonable. Sagna and Evra were old, even in 2016. Sissoko wasn’t very good then, and he’s still not very good now, and Payet is hurt or he certainly would have been in Russia. But it’s still a lot of turnover. Looking at it from a squad wide standpoint, only ten players played both in 2016 and made the current squad. Only five players were members of the 23 man squad in 2014, 2016 and 2018. This isn’t an issue limited to France either. Germany has only twelve holdovers from their squad two years ago. Eight players, so roughly a third of the team, have played in all three tournaments. Spain, the paragon of consistency over the years has only ten players in their squad from two years ago and nine that played in all three tournaments. This is just kind of how the international game works. This shouldn’t be surprising of course, football is a game that’s constantly in motion. Four years ago Liverpool were coming off a miracle second place season and contemplating life without their megastar Luis Suarez. This year they reached the Champions League final without Suarez, and the three other biggest attacking forces from the 2013/14 team, Raheem Sterling, Philippe Coutinho, and Daniel Sturridge. Things change fast.

Of the starting 11, only Paul Pogba, Antoine Griezmann and Hugo Lloris are constants. It’s also possible to make the argument Blaise Matuidi will start this time around, but at the same time the only reason Griezmann started in 2014 was that Franck Ribery was hurt in the run-up to the Cup. Additionally none of the three subs who appeared in the final two years ago are on this squad. A full three quarters of the back line has changed. Samuel Umtiti is the only holdover. Four starters from two years ago, Bacaray Sagna, Patrice Evra, Moussa Sissoko and Dmitri Payet aren’t even on the squad. That’s not unreasonable. Sagna and Evra were old, even in 2016. Sissoko wasn’t very good then, and he’s still not very good now, and Payet is hurt or he certainly would have been in Russia. But it’s still a lot of turnover. Looking at it from a squad wide standpoint, only ten players played both in 2016 and made the current squad. Only five players were members of the 23 man squad in 2014, 2016 and 2018. This isn’t an issue limited to France either. Germany has only twelve holdovers from their squad two years ago. Eight players, so roughly a third of the team, have played in all three tournaments. Spain, the paragon of consistency over the years has only ten players in their squad from two years ago and nine that played in all three tournaments. This is just kind of how the international game works. This shouldn’t be surprising of course, football is a game that’s constantly in motion. Four years ago Liverpool were coming off a miracle second place season and contemplating life without their megastar Luis Suarez. This year they reached the Champions League final without Suarez, and the three other biggest attacking forces from the 2013/14 team, Raheem Sterling, Philippe Coutinho, and Daniel Sturridge. Things change fast.

So Few Games, So Much Time

In the club game there are plenty of games to analyze. Things might always be changing, but games are also always being played. It’s just harder in international competition. There are only so many important matches to consider. Qualifying matches are often against extremely weak opposition. How much information does beating San Marino by six goals instead of eight really tell us? Especially when the players who play in those matches may, in fact, be drastically different than the ones who end up suiting up for a major tournament. How seriously should we consider the recent (and not so recent) records of teams when we look at how they’ll do this time around? The short answer is that it’s still useful. The longer answer is that measuring international team performance is something slightly different than measuring club team performance, and it’s important to understand the distinctions. Evaluating national teams, over years and years of performances is mostly about establishing what their baseline talent levels are. Nations, of course, can become more or less talented over the years, but usually those changes will be gradual. Using some form of ELO system (usually modified with some special bells and whistles) allows for a broad look at national team results that gives a pretty accurate view of their talent level. This has lots of advantages. Lots of player variation on squads comes down to injury. Players like Rafael Varane, Diego Costa or Mario Gomez were all regulars for their national set up while missing one of the last three major tournaments due to injury. While that might have changed how strong those respective teams were at those tournaments, it didn’t change the overall outlook for those nations going forward. Additionally, even in a player’s absence, a decent rating system understands that their likely replacement won’t be much worse. Dmitri Payet got hurt just before the World Cup, but Florian Thauvin is a similarly talented replacement. After 2014 Philipp Lahm retired. Somewhat miraculously, Germany hasn’t missed a beat as Johsua Kimmich has stepped right in. A team’s talent pool is larger than the 23 players it brings to any given tournament. Long term rating systems capture the talent level of the pool fairly well and create an accurate stable picture. The problem is that tournaments are snapshots, not long term averages. If Neymar isn’t at 100 percent this tournament it will matter a great deal for Brazil’s chances of walking away with the trophy. It won’t, and shouldn’t, matter very much for how good a team Brazil is going forward, but that will be cold comfort if they get eliminated in the quarterfinals. Neymar is a giant super star, so that dynamic is obvious. What’s less obvious is finding players who don’t stand out quite so clearly, but are similarly crucial to their team’s success. It’s simply very hard to tell, given the limited nature of international play, exactly which players are unreplaceable. During a league season even a five game sample can give a lot of relevant data as to what's changing on a team. By the time a team has played five games at the World Cup they'll be in the semifinals. Small sample sizes are an intractable problem. Analyzing the club game gives managers, pundits and fans the option of simply waiting for more data to come in. By the time you get more data in the international game the your infant will be heading off to kindergarten. ELO based systems are great, and they're perfect for providing a set of priors to base analysis of a major international tournament on. But, it’s important to do guess work from there, and subjectively try to separate the bounces of the ball from the real systemic issues quickly. Otherwise by the time the problem gets diagnosed the team will be on the plane home. The World Cup is an amazing tournament. Its resistance to precise analytics is part of the charm. (Header image courtesy of the Press Association)