England are into a World Cup semi final for the first time in 28 years and got there on the back of one specific method of attacking.

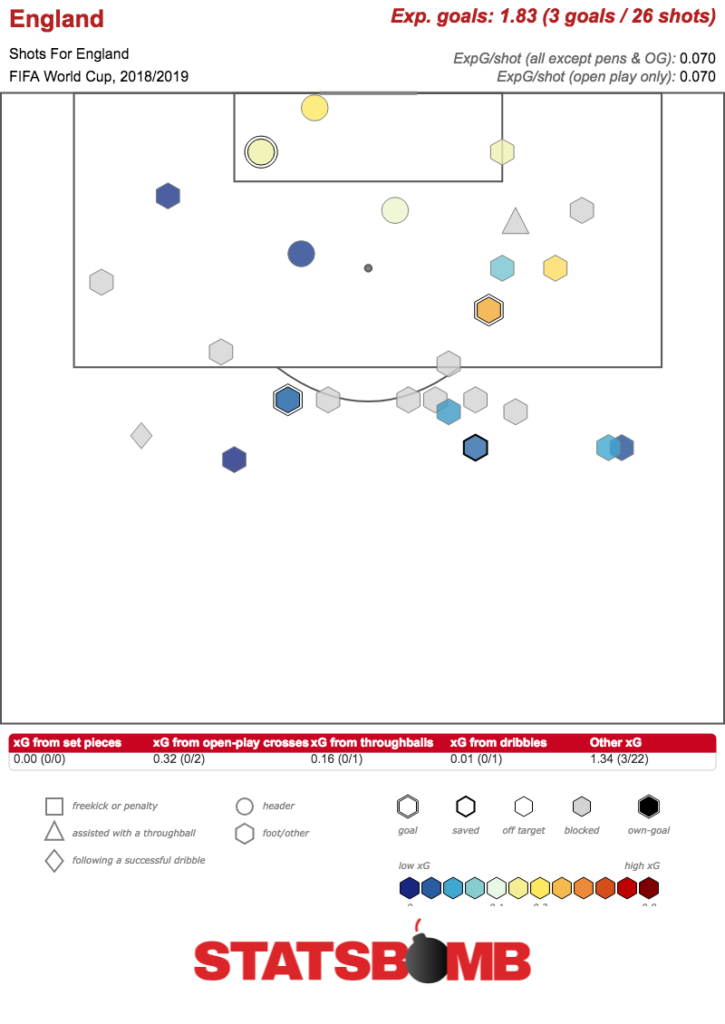

Set pieces have been the order of the day, and have proven a very effective tool in getting England to the semifinals, scoring five goals over five games from this route (not including penalties). An expected goals value of 4.59 suggests that there’s a good deal of repeatability about this, too. Nonetheless, the strong work done in this aspect of the game is covering up the lack of firepower in open play. Across five games now, England have created a grand total of 1.83 expected goals in open play. That’s about 0.32 xG per 90 minutes.

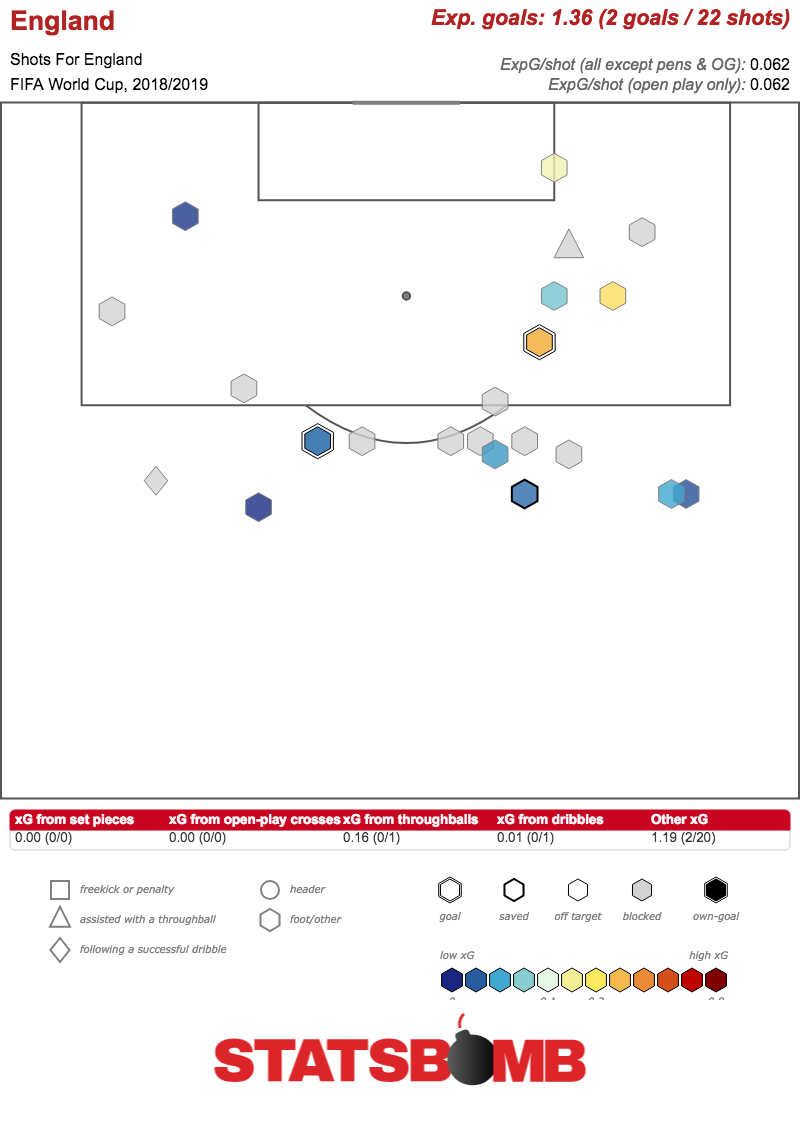

Worse still, most of the better chances here are from open headers. This makes a degree of sense, since part of the routines worked on for set pieces probably also have some effectiveness in the rest of the game. Still, if we restrict the xG only to open play shots without headers, we’re left with this map of sadness.

The first thing to catch the eye here is the complete void of nothing in the centre of the box, right in front of the goalmouth. To add an extra dose of frustration, the highest value shot here is Harry Kane’s third goal against Panama, which was an entirely unintentional touch he knew nothing about. Take the 0.31 xG from that out and we’re left with 1.05 expected goals, or 0.18 xG per 90.

As in, on average StatsBomb’s model would expect to see England score a goal from feet in open play once every five games.

Clearly there are some questions to be asked about how this happened.

One problem is a lack of creative passing. Of the players to have started the majority of England’s games at this World Cup, Kieran Trippier has generally been seen as the most creative. This is backed up by him managing the most open play passes into the box per 90 minutes, at 1.57. Yet this is lower than the 2.12 passes into the box per 90 he averaged in the Premier League this season, despite playing with more dominant creative outlets at Spurs such as Christian Eriksen.

This is a trend throughout the England team. The first choice front six (Trippier, Ashley Young, Dele Alli, Jesse Lingard, Raheem Sterling and Kane) generate a combined 8.45 open play passes into the box per 90. In the World Cup, this figure has fallen to 6.16. This is despite not having a dedicated playmaker such as Kevin de Bruyne or the aforementioned Eriksen at international level. In theory, these players should be playing the ball into the box more than in the Premier League, but that’s not taking place in reality.

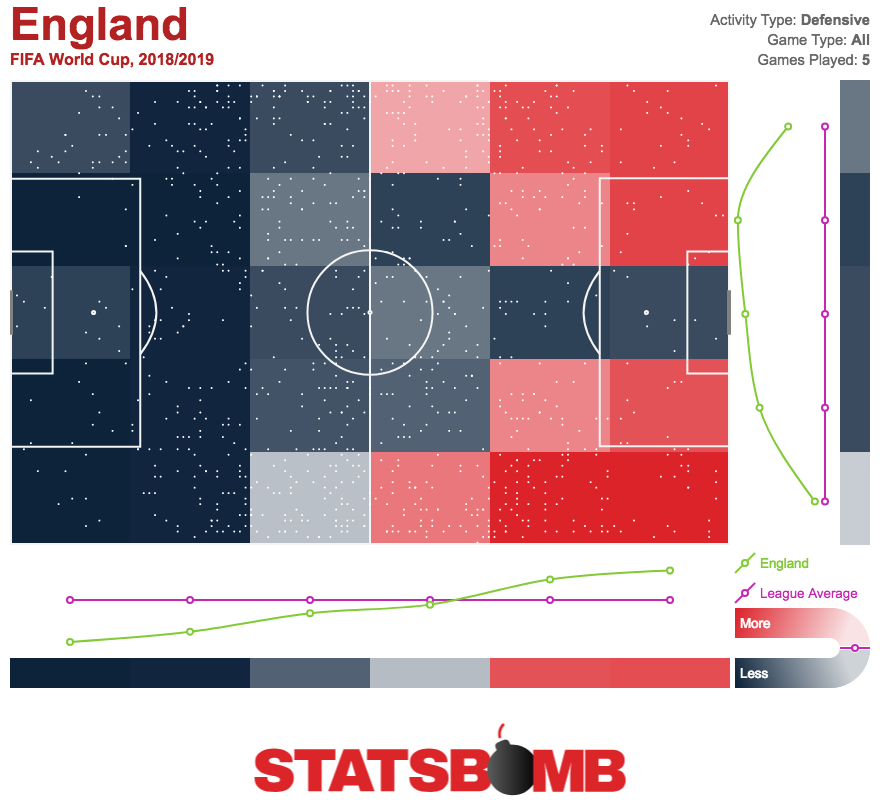

And it’s not as though England are not active in dangerous areas of the pitch. When looking at a defensive activity map, the immediate thing one notices is how aggressive the side are in the opposition’s half.

Teams that press a lot in high areas of the pitch usually tend to be very effective in generating shots in open play. “No playmaker in the world can be as good as a good counter-pressing situation”, as Jürgen Klopp has been known to say. And yet England aren’t really attempting to do this at all. To understand this, it is important to consider different reasons for a side to press.

England are not attempting a Liverpool-esque counter press for the purpose of attacking a team quickly in their own half, while the opposition defence is in an awkward shape. That approach, advocated by German coaches such as Ralf Rangnick and Roger Schmidt, has not been adopted, perhaps because it has a high level of difficulty or the players are just unsuited. Instead what we’re seeing is pressing primarily for defensive purposes. The players are aggressive in forcing the opposition to make suboptimal choices, or to give away the ball completely, but then look to be more patient in possession themselves. If the aim of this press is to restrict good chances conceded, it’s hard to argue with the results too much.

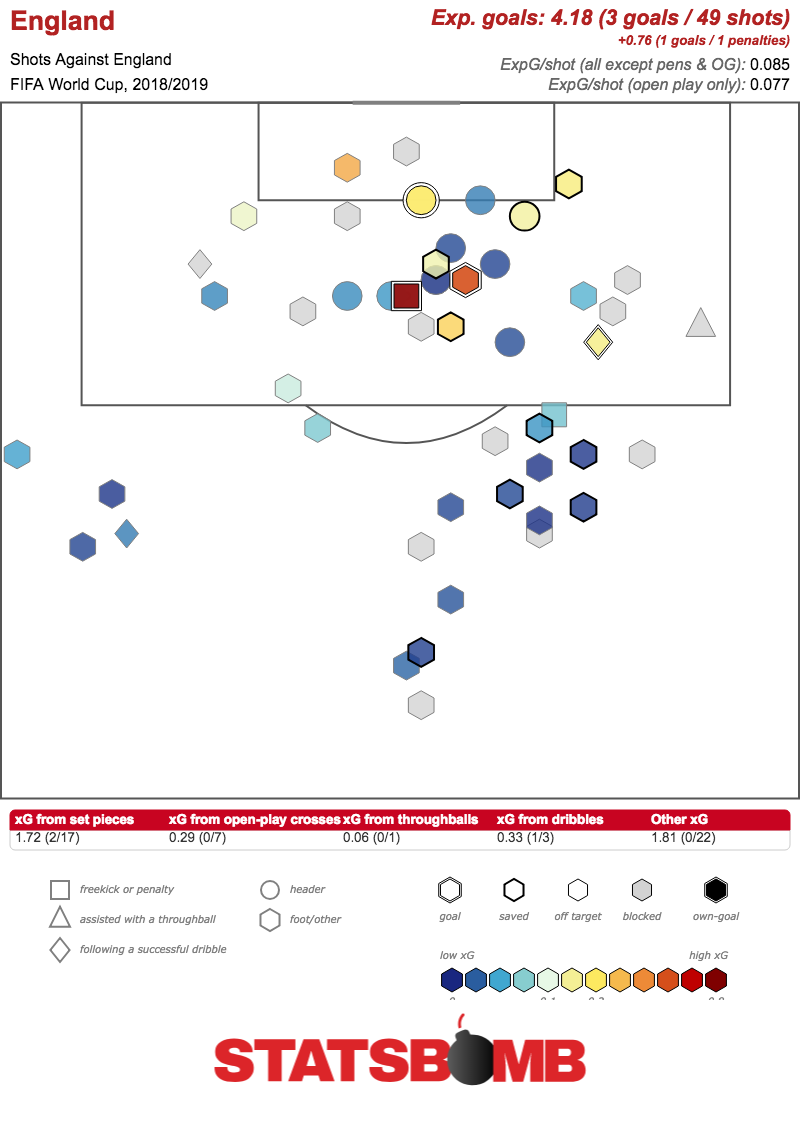

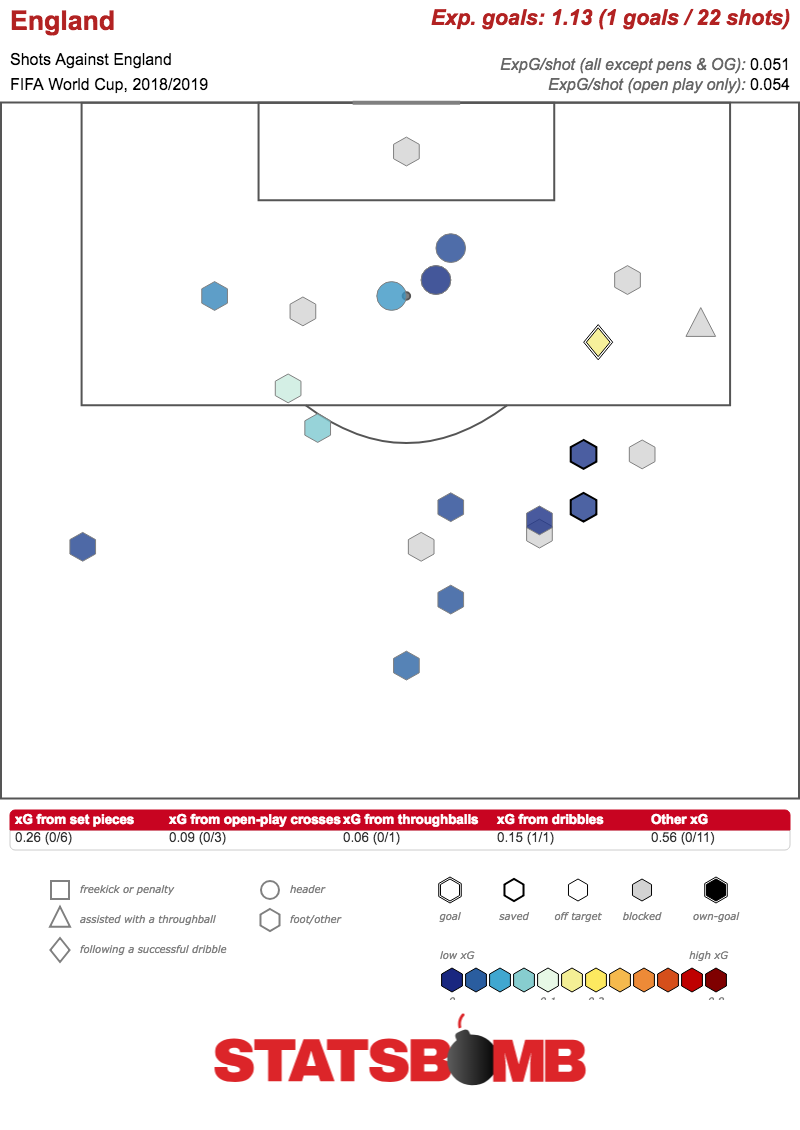

4.18 expected goals conceded across five games so far, or just 0.73 xG against per 90. Any way one looks at it, that’s solid. Interestingly, a lot of these shots have been conceded while the team is in a winning position, perhaps owing to a dip in concentration or the opposition being more forceful in pushing for an equaliser. When looking at simply the chances conceded while the side is drawing, we get this:

Just 1.13 expected goals conceded when the games are level. England have so far played 248 minutes of football while drawing, so that comes out at 0.41 xG per 90 conceded at this game state. While there are still concerns to be had over mistakes when England are ahead, it’s clear that it’s very hard to score against this team when on even footing.

This is much closer to the kind of pressing strategy deployed by Mauricio Pochettino than it is to Jürgen Klopp’s attack through defense. Pochettino’s Tottenham side tend to press aggressively as a defensive strategy, while the attacking side of things is about grinding the opposition down with a range of different shots. With Harry Kane, Dele Alli and Kieran Trippier all important cogs in the attacking side of that Spurs team, it makes sense that England would go for a similar approach.

Pochettino, however, has a greater range of tools in order to unlock a defence. Christian Eriksen can use his excellent creative passing, Mousa Dembélé can move the ball through midfield with his excellent dribbling, and even centre backs Jan Vertonghen, Toby Alderweireld and Davinson Sánchez can open up the game. England do not have the same kind of options. Jesse Lingard, like Alli, is primarily useful in terms of making runs into space without the ball. Jordan Henderson in defensive midfield is a slightly underrated passer, but still primarily valuable for his energy. The back three are all comfortable on the ball but not nearly as adept as the Tottenham trio. Really, only Raheem Sterling is someone who can easily offer significant ball progression in this side, and has done so a fair amount, but one man can’t do it all.

The obvious question to ask is why England manager Gareth Southgate decided to structure his side this way with obvious holes in terms of personnel. The most straightforward reason is that there are a number of players in the squad who already play for Tottenham, and several more who play in slightly but not dramatically different pressing systems at Manchester City and Liverpool. With the lack of time and coaching talent generally found at international level, if you can get a complex system half right you’re already ahead of the curve.

What’s more, as Rafa Benítez says, football is a “short blanket”. You cannot cover everything, and be effective in every aspect of play. Encourage Dele Alli and Jesse Lingard to take more advanced roles running into the box more frequently, and one risks exposing Jordan Henderson’s cover of the back three. This is all the more acute in international tournaments, where time is in short supply. If Southgate had opted to spend more of his coaching hours working on attacking patterns, some of the defensive work would have inevitably become less rehearsed and more disorganised.

All of this might be why England are so focused on set pieces as a tool to score goals. Aside from the delivery, this is less reliant on technique and creative passing. It is also likely easier to rehearse in a short space of time than some of the best attacking moves we see at club level, the type that make it seem as though the players have an almost telepathic understanding with each other.

What’s more, the requirements for knockout football are different than that of a 38 game league season. A World Cup winning side will play just seven games on their way to the trophy, and losing any one of the last four is obviously a guarantee of failure. As we saw with Portugal in Euro 2016, keeping things very low scoring in the knockout stages can be as effective a route as any, especially for a side not blessed with a number of great creative players. If England had any intention of a different approach, the time to use it would have been in the group stages.

It is entirely possible that this team will lose to Croatia primarily because of an inability to create chances in open play. Perhaps it won’t be, but then in the final against France, England will have a lot possession with an inability to turn it into shots. It’s not obvious, though, that a more expansive approach that solves these problems would increase the chance of winning the World Cup. While it may have some flaws, England have probably given themselves the best platform to achieve their first title in this tournament in 52 years.

Header image courtesy of the Press Association