The 2018–19 season initially looked like another season in which Monaco's expertise would navigate another summer of key departures. Getting over £90 million for Thomas Lemar and Fabinho looked to have been another example of getting close to full value on players who were good but not necessarily great. That money was used in a very typical Monaco fashion: taking numerous cracks on young players like Aleksandr Golovin, Benjamin Henrichs, Willem Geubbels, and Samuel Grandsir and hoping enough of them pan out. In Leonardo Jardim, Monaco could feel confident knowing they had a manager who's had experience dealing with squad turnover and giving minutes to young talents, so the club could be confident they would still remain in one of the Champions League qualification spots during the transition.

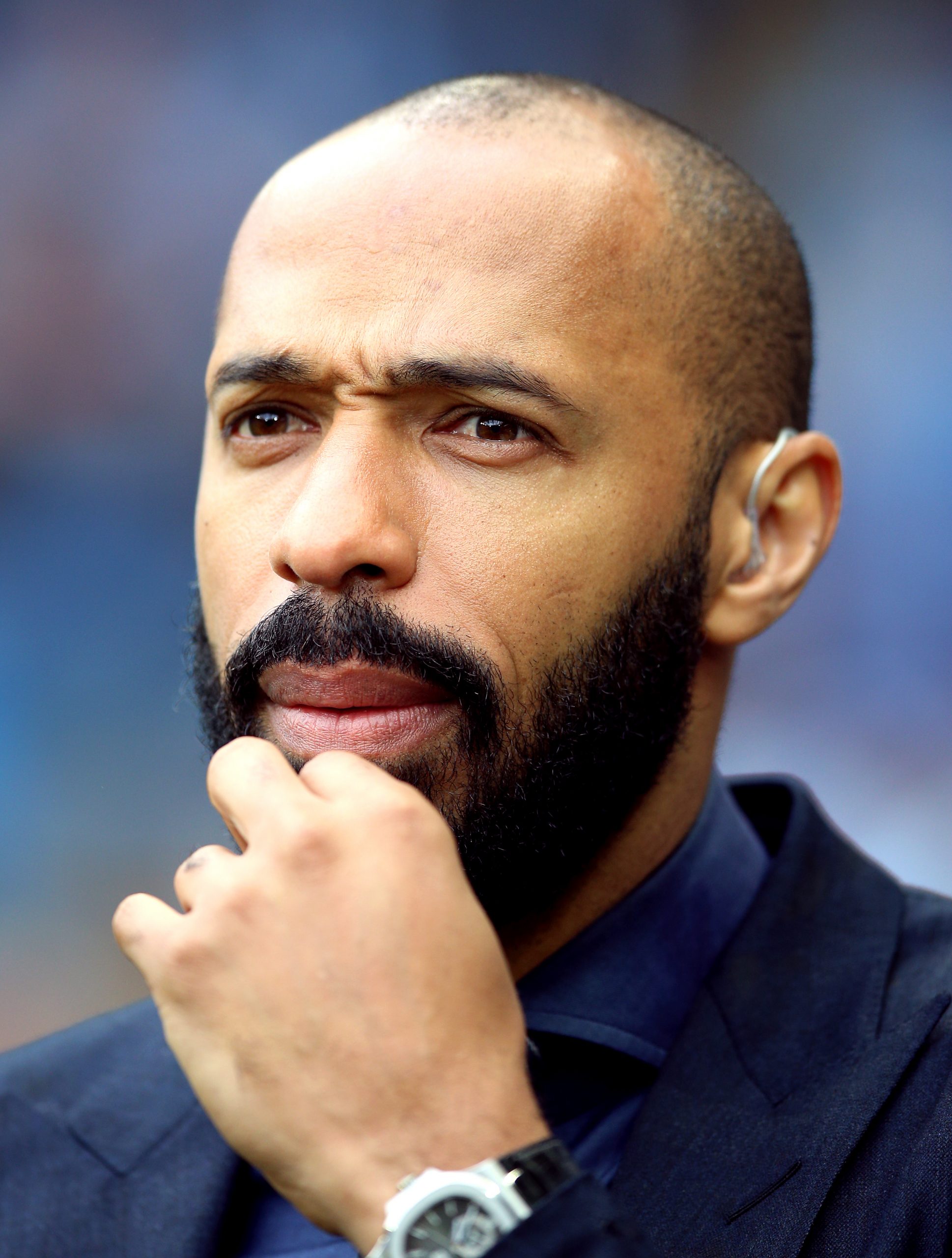

Except, that hasn't been the case this season. The exact opposite has occurred. Monaco sit in 18th place through nine games, a full 10 points off of third. That last part is crucial because what's allowed Monaco to perform well in the transfer market over the years has been their ability to consistently qualify for the CL. Without CL football, their bargaining position is weakened. It was fair to be skeptical that Monaco could once again have a summer of upheaval and finish in the top three by spring, though even the most pessimistic of projections wouldn’t have pegged them to have such a rough start to the season. And in fact, Monaco's struggles are happening in part because they are failing to achieve the levels expected goals suggest they should be at.

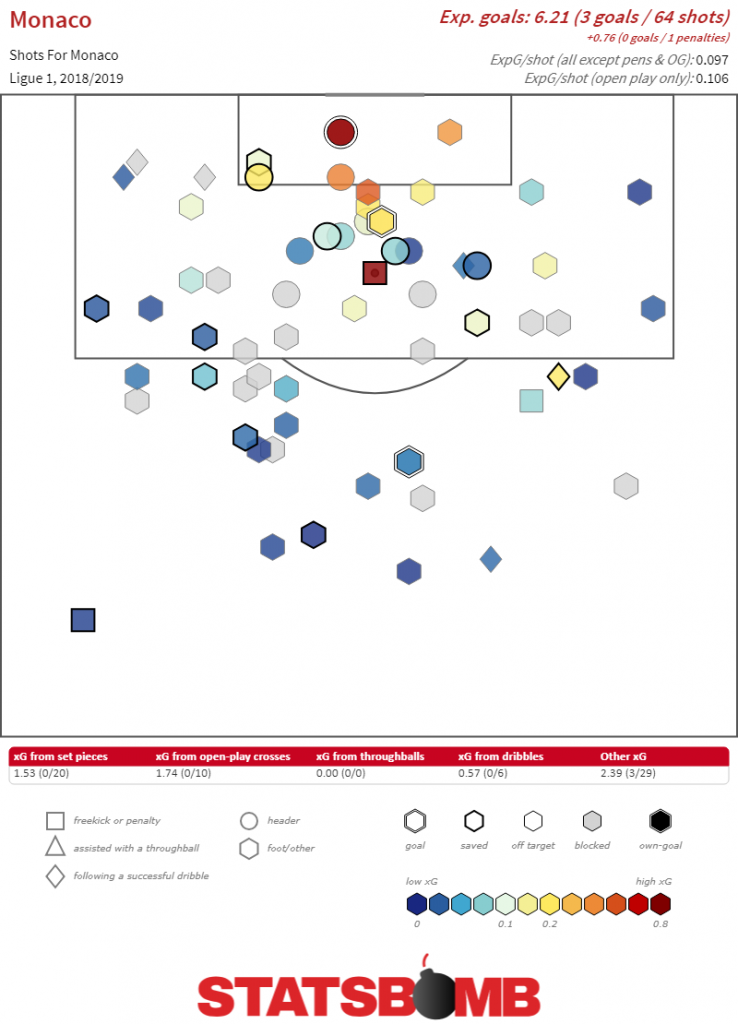

Monaco have probably been unlucky to have a -4 goal differential, it's also true that their performance while at an even game state has not been good. One of the great things about Monaco over the past couple of seasons, especially in 2016–17, was their ability to dictate play relatively well while the game was tied and then pile up the score once they went ahead. A one goal lead would turn to two, two would turn to three and it’s a wrap. When you’re not even breaking a 50% share both in shot quantity and quality, it’s makes it harder to break games open.

Monaco this season is a team that is still searching for that level of cohesiveness that top sides usually have. This isn't surprising when you consider that the starting XI has been constantly tinkered with through the first two months. A remarkable 22 players have already logged over 150 minutes in Ligue 1 this season. While it's optimal to have some squad rotation in place when dealing with the rigors of domestic and continental football, having that many players be part of the rotation is a sign that you're throwing stuff at the wall and hoping something sticks.

Monaco's ability to play from the back has been hit or miss. When teams have largely remained discipline in closing the passing lanes into the central midfield by angling their bodies while sprinting to press one of the center backs, Monaco have had to resort to going long as a counter. Once this happens, you'll see switches in position where one player goes deep and a teammate tries to find space behind the defense. At its best, it can cause confusion for the opposition and create openings for the most forward player of the two to run into open space.

Even during scenarios in which Monaco have no problems progressing the ball through the middle of the pitch, the team is still missing that little bits of tactical automation that can turn the screws in their favor. Kamil Glik makes a nice pass through the middle into Moussa Sylla and lays it off to Radamel Falcao. There’s a small window where Adama Traoré has the opportunity to make an off-ball run that could bend the defense in his favor or for someone else but he doesn’t choose to take it. Instead, it just ends up with a low efficiency shot from Antonio Barreca.

Once the ball isin or near the final third, Monaco often have a player dart into the wide areas to try and drag his marker with him. The man on the ball can try and beat his opposition marker off the dribble and then commit other defenders to him so passing options into the box could be open for the likes of Falcao and Moussa Sylla, or try some quick combination. The downside of such a strategy is that there's a lot of responsibility placed on the man in possession to either win his individual duel because there's really no one in the halfspace area to help him out.

A crucial aspect in Monaco's attack that has declined from years past has been their ability to strike fear during transition play. At their best, Monaco were able to gather the ball near midfield, have fullbacks Benjamin Mendy and Djribil Sidibe make aggressive overlapping runs and either create cutbacks for players arriving late into the penalty box or hit low crosses to the feet of Falcao or Kylian Mbappe near the six yard box. That hasn't really been the case this season as their transitions from defensive actions has lacked that same level of dynamism. Even when the fullbacks join in the attack, they haven't been able to connect on those low crosses that create the high value shots that teams look for.

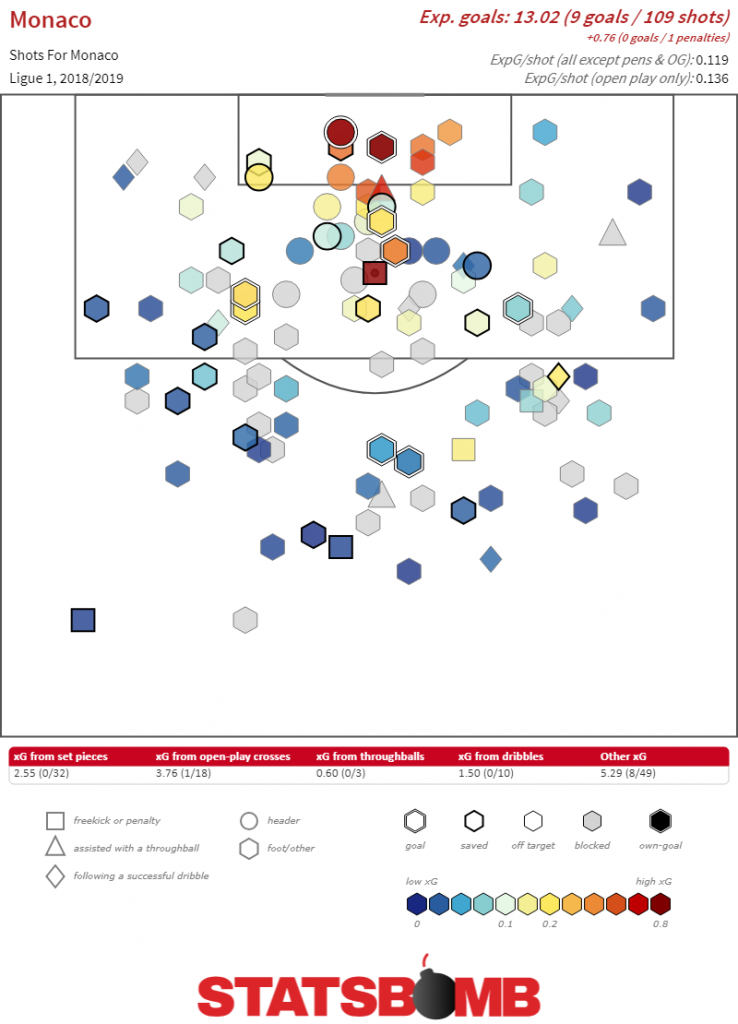

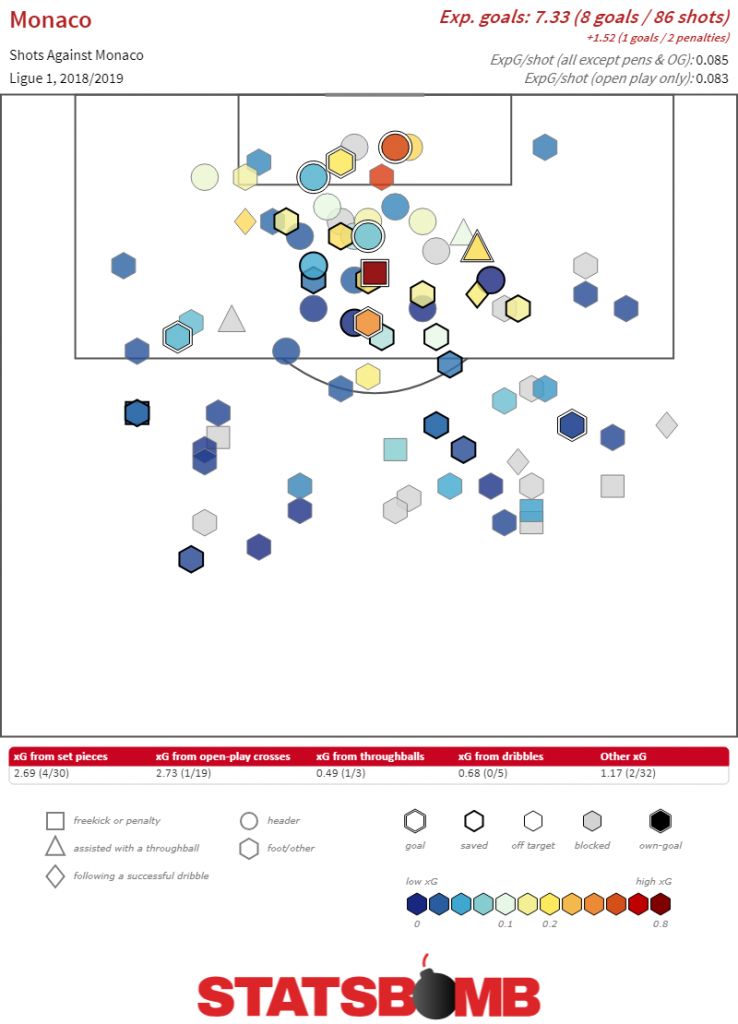

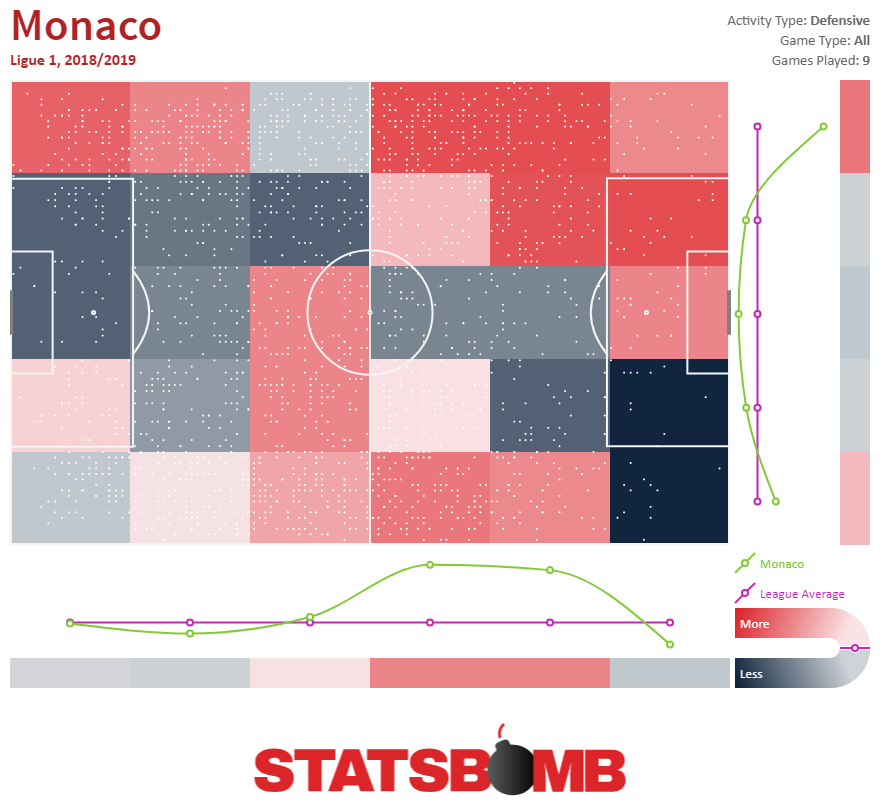

Faced with those issues, Monaco's defense would have to be near elite to make up for their attacking deficiencies. Monaco's defense has been better than their goals against record would indicate, but not good enough to balance their woes going forward. The good news is that they're only giving an xG per shot of just over 0.08 in open play, which is around the mark you would hope for from a solid defense. Monaco defend in a shape resembling a 4-4-2, whether they're applying pressure higher up the pitch or defending in a mid-block. When a switch of play occurs, the wide player closest to the ball applies pressure and force a pass back to the CB, which in turn triggers the forward to press the center back and eventually force the ball back to the goalkeeper for a punt. Monaco can do this rotation solidly, and it explains why they have a large intensity of defensive actions in the wide areas.

In the range of possible outcomes for Monaco's 2018-19 season, what's happened through nine games would rank in the bottom 10 percent. It's fair to point out that one of the drawbacks of constantly retooling with younger talents is that there will be down year(s) where you’re working with a talent base that might not quite be ready for primebtime. While I'm quite partial to how Monaco have operated and leveraging their security as a top side in Ligue 1 to aggressively hunt for star talents, even going as far as to spending ample amounts of money on teenagers like Pietro Pellegri and Willem Geubbels, the downside of such an approach is that you’re susceptible to below average seasons.

In the range of possible outcomes for Monaco's 2018-19 season, what's happened through nine games would rank in the bottom 10 percent. It's fair to point out that one of the drawbacks of constantly retooling with younger talents is that there will be down year(s) where you’re working with a talent base that might not quite be ready for primebtime. While I'm quite partial to how Monaco have operated and leveraging their security as a top side in Ligue 1 to aggressively hunt for star talents, even going as far as to spending ample amounts of money on teenagers like Pietro Pellegri and Willem Geubbels, the downside of such an approach is that you’re susceptible to below average seasons.

None of those mitigating factors were enough to save Jardim's job as manager of Monaco. I’m of the belief that there are only a few managers who are clear outliers, either good or bad, while most are bunched in the middle and rank somewhere between slight positives and slight negatives. It’s fair to conclude that Jardim ranks as a net positive manager and perhaps could be considered someone who is an outlier on the positive end. Despite the variance that benefited his clubs over the past two years, the seamless transition from the 2014–15 iteration that relied on compact defensiveness and opportunistic transitions to the aesthetically pleasing football they’ve played in recent seasons was quite impressive, especially considering this was all done while having to deal with constant turnover in the squad. That isn’t an easy feat at all and it's a credit to Jardim that he helped make the Monaco project work as well as it has. How much of a net positive Jardim is as a manager is where things get more interesting. More than anything, it comes down to how much you believe he’s someone like Lucien Favre, where there's constant positive variance outperforming shot and expected points models season after season. His Monaco sides from 2014–16 performed like the 3rd or 4th best team in the league and finished 3rd in both seasons, while the last two were about as outlier-y as outliers can be.

Thierry Henry is taking over for Jardim. Outside his stint as an assistant for the Belgium national team and his constant use of the word "freedom" while working for Sky Sports, we don't know anything about his capabilities as a manager. That cuts both ways: while there'll be an inherent skepticism of a first time manager taking the reigns of a major club like Monaco, maybe Henry turns out to be someone who's just good at his job. I lean more towards the skeptical end of the spectrum, particularly given that he's coming in during the season to a team that's in a rut, but it's possible that Henry has a smoother transition into the managerial role than most of us are giving him credit for. I still believe there's more than enough talent for Monaco to steady the ship and not have to worry about being in the relegation zone 5-10 games from now, though having to make up the gap between themselves and the Champions League spots might be too hard of a task to accomplish. There's been a few bright spots: Benjamin Henrichs has performed ably in the minutes he's played at fullback, Youssef Aït Bennasser continues to be an intriguing midfielder, and Moussa Sylla has had his moments as an 18 year old attacking prospect in a major European league. Monaco's overall numbers are better than your typical 18th place team, but it's clear that there's been a deterioration in performance once you dig a little deeper. For a first gig, Thierry Henry has got himself into a tricky situation with a mishmash of talent that's nowhere near close to firing on all cylinders. Whether Henry's the guy to turn Monaco's fortunes around or he's biting off more than he can chew is anyone's guess.

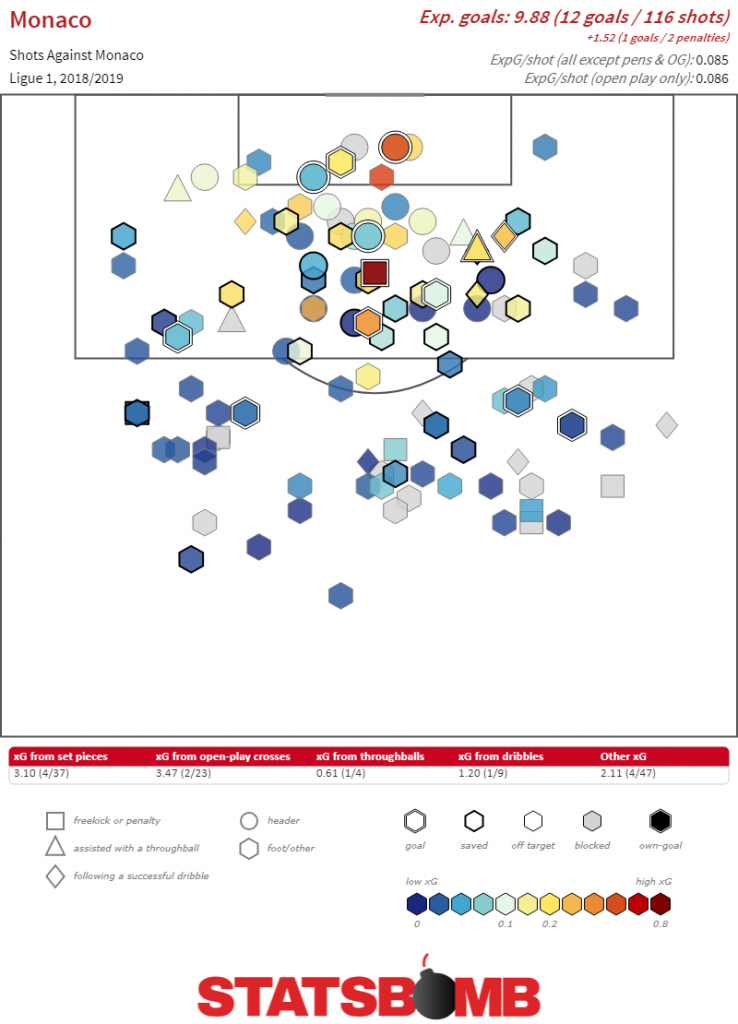

Header image courtesy of the Press Association