For starters, the perfect answer to the headline above can be found in a single passage of play.

Spool back to the second Norwich goal in their 3-2 win over Manchester City on Saturday and you see a string of errors in the absence of Aymeric Laporte, the commanding center back who has been ruled out with a knee injury until early next year.

As Norwich break forward Nicolás Otamendi pushes up on Marco Stiepermann, only to let him escape and turn. While Stiepermann looks for Teemu Pukki, John Stones steps up and appeals for offside, unaware that Kyle Walker is playing Pukki on by tracking Todd Cantwell. After Stiepermann plays through Pukki, you are left wondering whether a defender younger than the 31-year-old Otamendi might have caught the striker, or at least put him under pressure. In any case Pukki sets up Cantwell for a tap-in. That's followed by a second-half encore in which Otamendi loses the ball by his own box and gifts Norwich another goal. This is evidently what happens when Stones and Otamendi play. This is how much City will miss Laporte.

While anecdotes are nice, its important to look at trends over a longer stretch of time to figure out how representative Saturday's disaster is of how much Laporte will be missed. City will miss him. Guardiola says he is the best left-sided central defender in Europe. The only two natural replacements, Stones and Otamendi, did play well in 2017/18, particularly Otamendi, whom Guardiola called “superman”. Yet this week Sky Sports ran a graphic of the main five central defensive duos under Guardiola. Four of them had conceded between 0.5 and 0.7 goals per league game. The exception was Stones and Otamendi, who had averaged 1.1.

While Stones has his critics, the coming months will direct the spotlight at Otamendi, who plays on the left where Laporte belongs. By most accounts Otamendi would have dropped out had Laporte been fit. Stones played far more than both Otamendi and Vincent Kompany last season, and has started the games this season when available. Otamendi reportedly wanted to leave in summer, but nobody could (or wanted to) meet his wage demands.

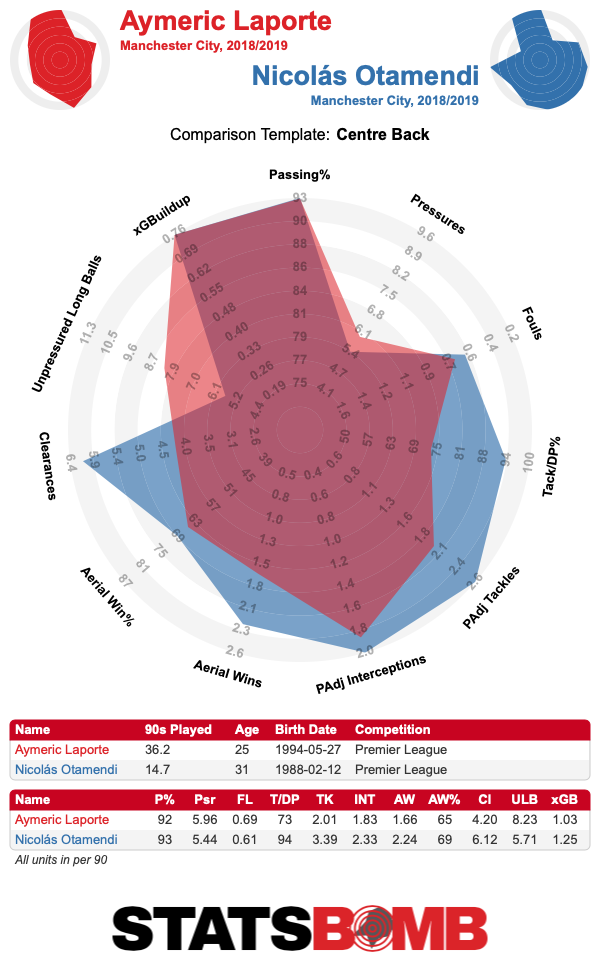

As such it makes sense to focus on what Laporte has that Otamendi lacks, and vice versa. If Laporte appears to be better in all departments, the stats disagree. Unlike Laporte, Otamendi was not dispossessed once in the league last season. Otamendi was the City outfield player with the highest tackles success (94%), a rate far better than Laporte (73%). In fact the radars for last season portray Otamendi as a formidable battler who outperforms Laporte both in terms of the frequency with which he goes into duels and the rate at which he wins them.

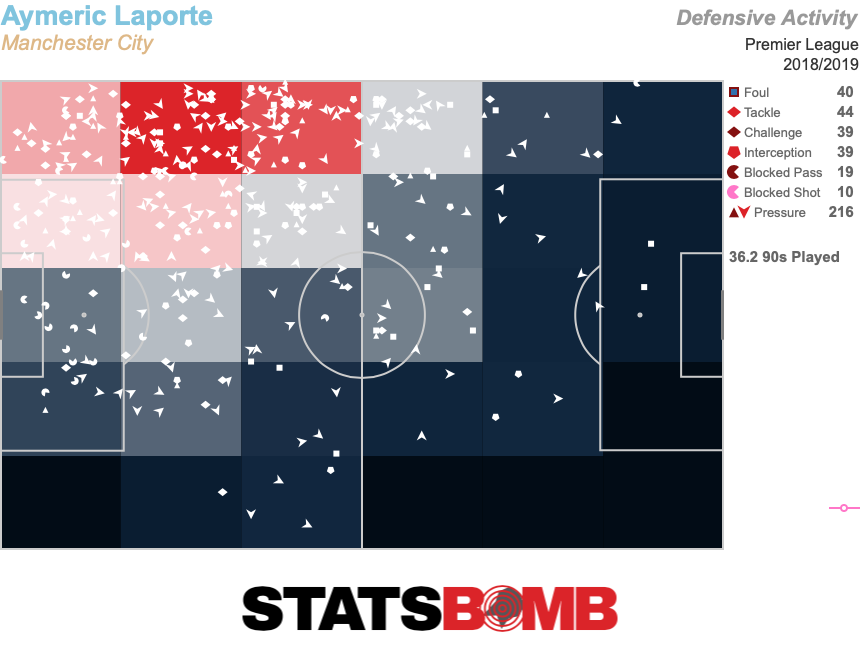

Some factors, however, escape the radars. As a more aggressive defender, Otamendi can be prone to rush into challenges. Laporte tends to be cooler and more calculated, and might take out extra depth rather than charge towards the ball. Stats struggle to measure positioning, but the fact that Laporte, 25, would be likely to outpace Otamendi will affect how City defend. Looking at Laporte’s defensive actions last season, you see how often he moves out wide (even considering the handful of minutes he played at leftback), perhaps as a result of the high line inviting forwards to seek the space between the full-backs. In any case such situations tend to put center backs in one-on-ones, where Laporte will be more comfortable than Otamendi.

The comparison between the two gets starker when we turn to build-up play. That Laporte is left-footed gives him an advantage. “Because he is left-footed playing on the left side he gives us an alternative for the build-up, quicker and faster than the other ones who are right-footed,” Guardiola said nearly a year ago. “When you receive to go to the right, you have to go inside, because you want to go to the right foot. With the right foot, it is a little bit more complicated.” This is classic Guardiola, obsessing about body shape and the milliseconds you can shave off the build-up play by having a certain type of defender.

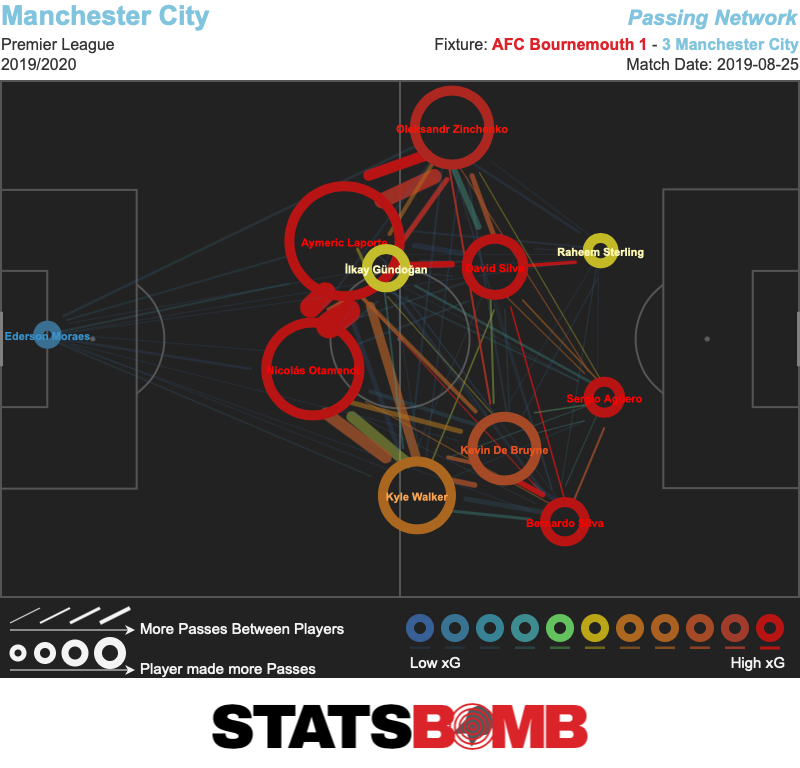

A big part of the City build-up is provoking the opponent by carrying the ball forward. The center backs can move it upfield if unpressured, forcing deep-lying opponents to commit players and perhaps leaving others free. This task often befalls Laporte. Last season he made 9.86 deep progressions per 90 minutes, far more than Otamendi (6.39) as well as Stones (5.41). This is one of the aspects in which his absence will be felt. As for distribution, Laporte again wields a lot of influence. In his most recent full game, the 3-1 win at Bournemouth, he was more involved than Otamendi and played further upfield, as seen in the graphic below. Whereas Otamendi connects with Walker and Kevin De Bruyne, Laporte varies his passing more: some zip to the feet of David Silva, others float across to De Bruyne, and a few even find Sergio Agüero.

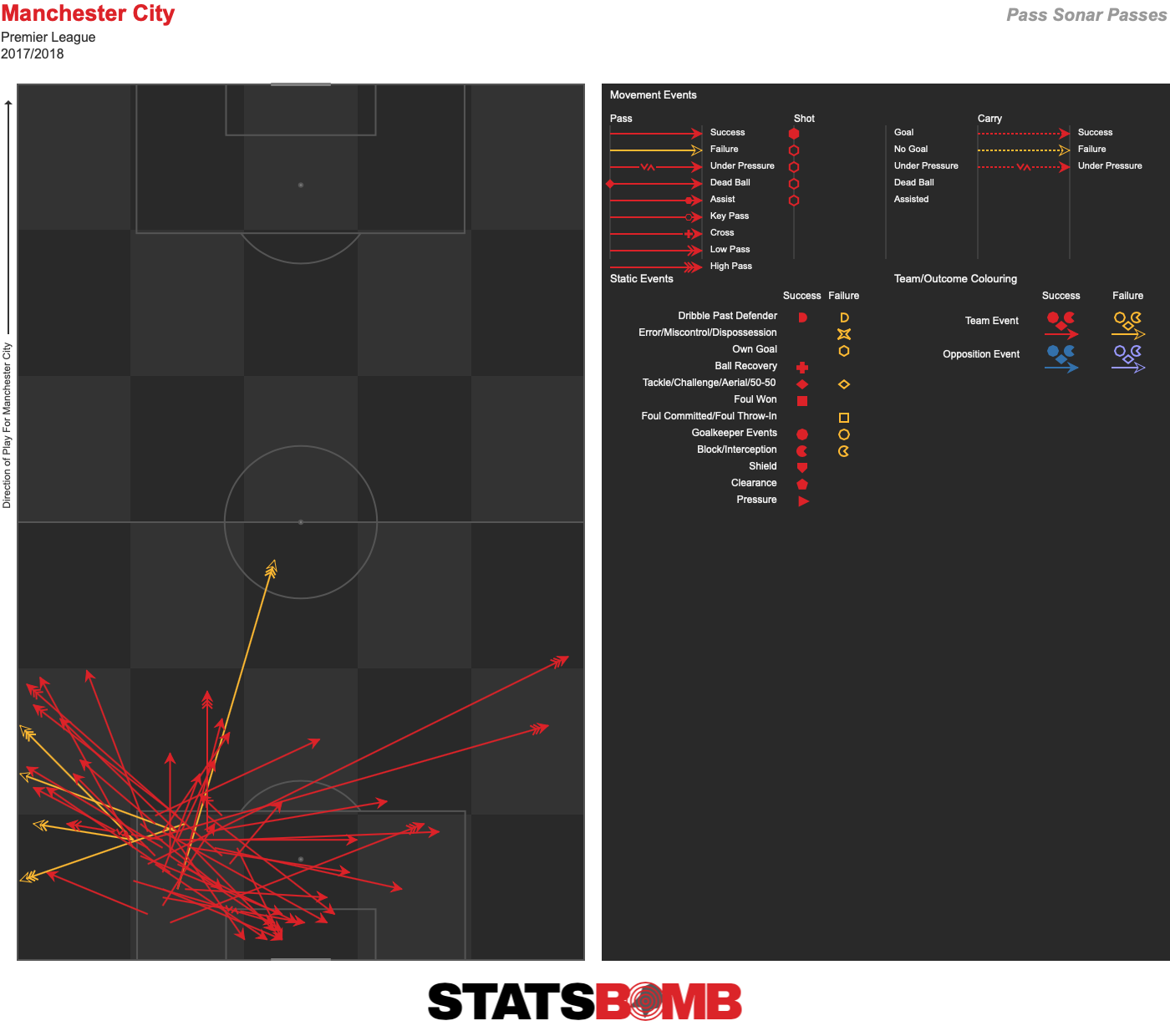

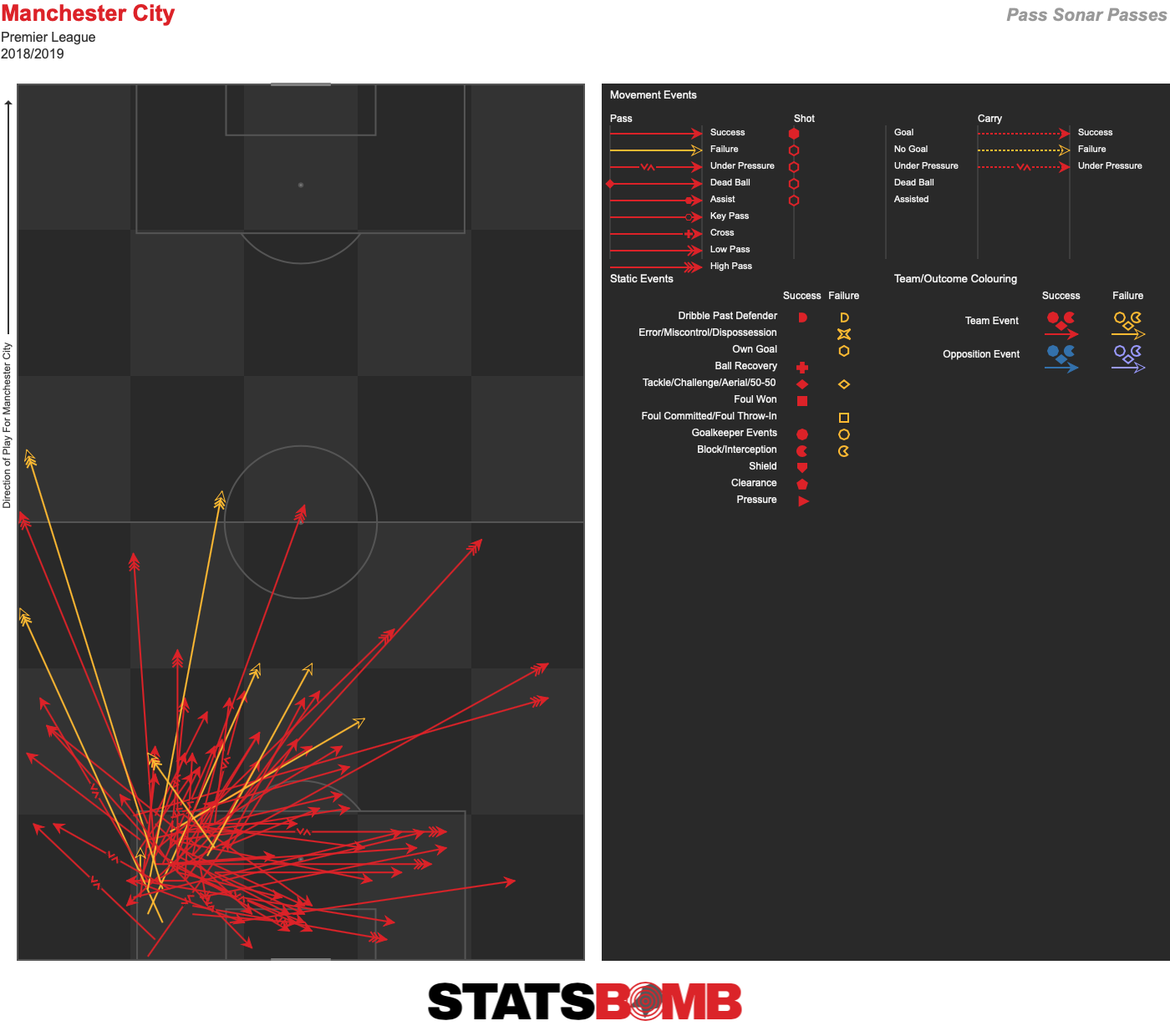

If we look at the distribution from key areas last season, the contrast becomes even greater. The graphic below shows how Otamendi passed the ball from the left side of his own box; almost the same place where he lost the ball at Norwich. Knowing what to do here is likely to be even more important this season, since centre-backs are allowed to get the ball inside the box directly from goal kicks. In this case, Otamendi seems to play straightforward passes, save for a couple of diagonals to the right. A concern, however, is the four passes that go out of touch across the left touchline.

What about Laporte? The difference is significant. There seem to be no simple passes put right out of touch. Several times he finds teammates with long passes that land near the halfway line. The short and medium-range passes are also more progressive and varied.

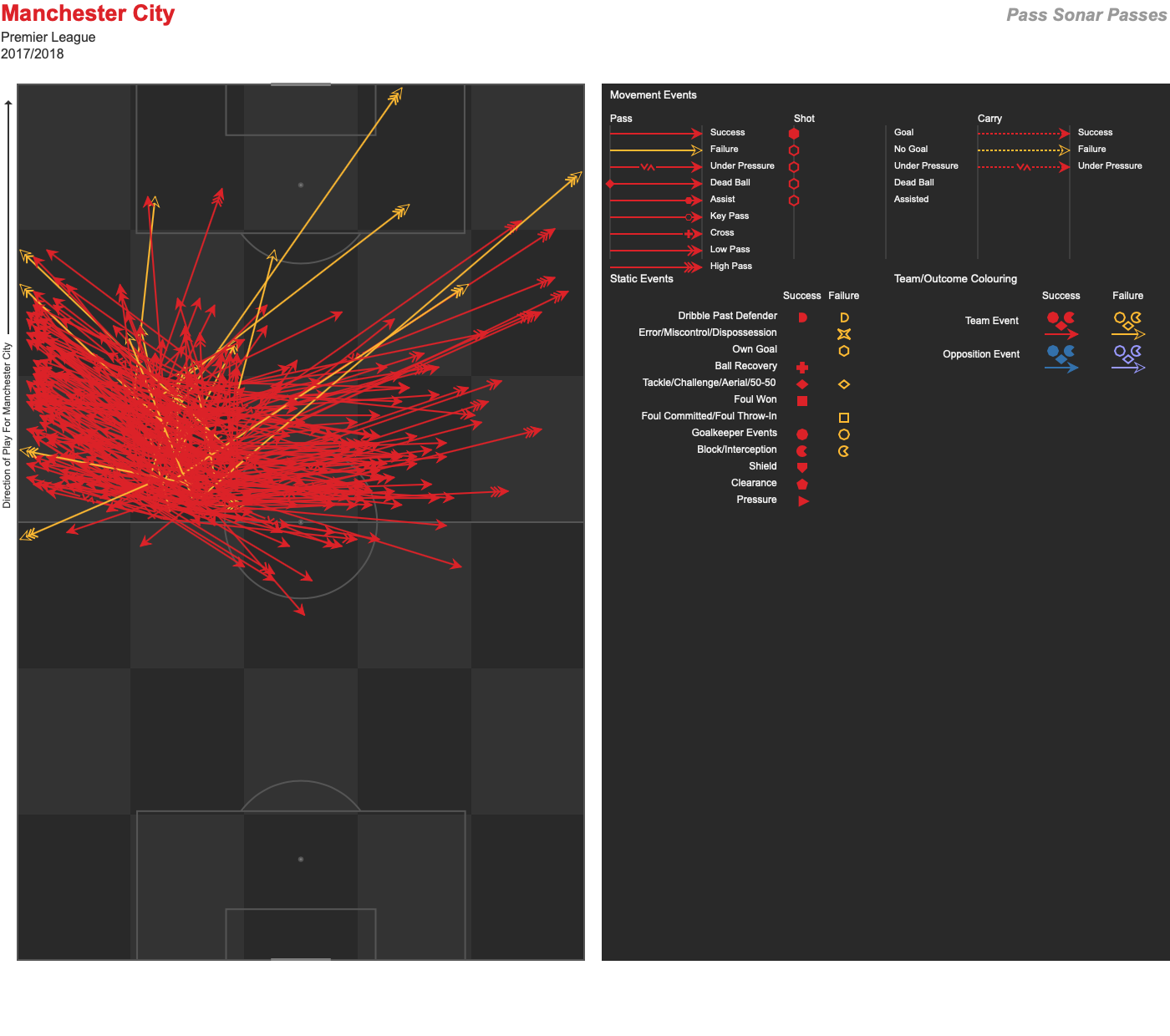

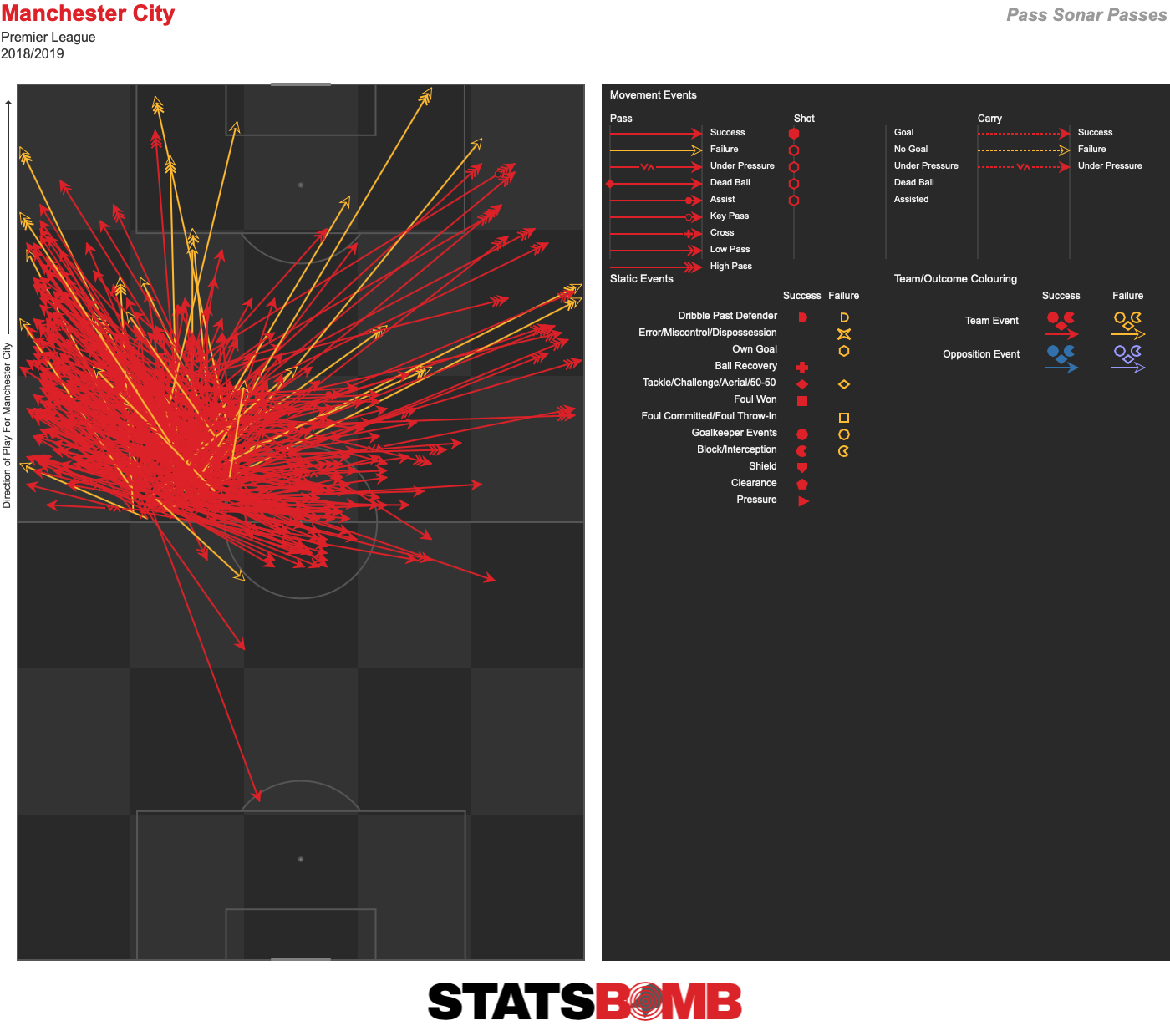

Then we go to another phase of the distribution phase: opening up deep-lying teams. The graphic below shows Otamendi’s passing from the left side just inside the opposite half. Again the distribution seems to be decent but unspectacular. There are a few diagonals, a couple of forward passes, but he mostly moves the ball sideways.

With Laporte it’s a different story. There are about twice as many diagonals to the right wing. The shorter passes set teammates up in more advanced positions. Look closer and you see that more of his arrows reach the zone just outside the box. About a dozen land inside or level with the penalty box. The statistical basis for this observation can be found in the radars: Laporte completed 8.23 unpressured long balls per 90 minutes last season, whereas Otamendi managed 5.71.

It is hard to say how these contrasts will affect City’s points total. Otamendi and Stones are better than what they showed at Norwich, and perhaps some of their discomfort came from having grown unaccustomed to playing without Laporte, who has played almost every minute over the last year. Given time on the training ground Guardiola can adjust the defensive mechanisms to make up for the pace lost through Laporte. If worst comes to worst Fernandinho can step in. What none of these players can do, however, is compensate for the playmaking element that Laporte brings, and that might be what worries Guardiola the most.