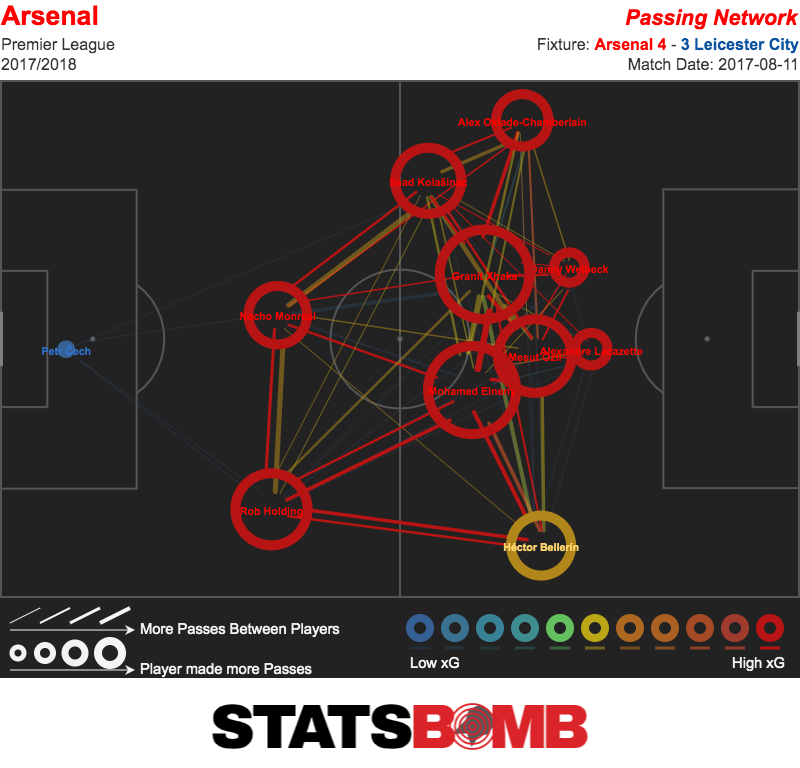

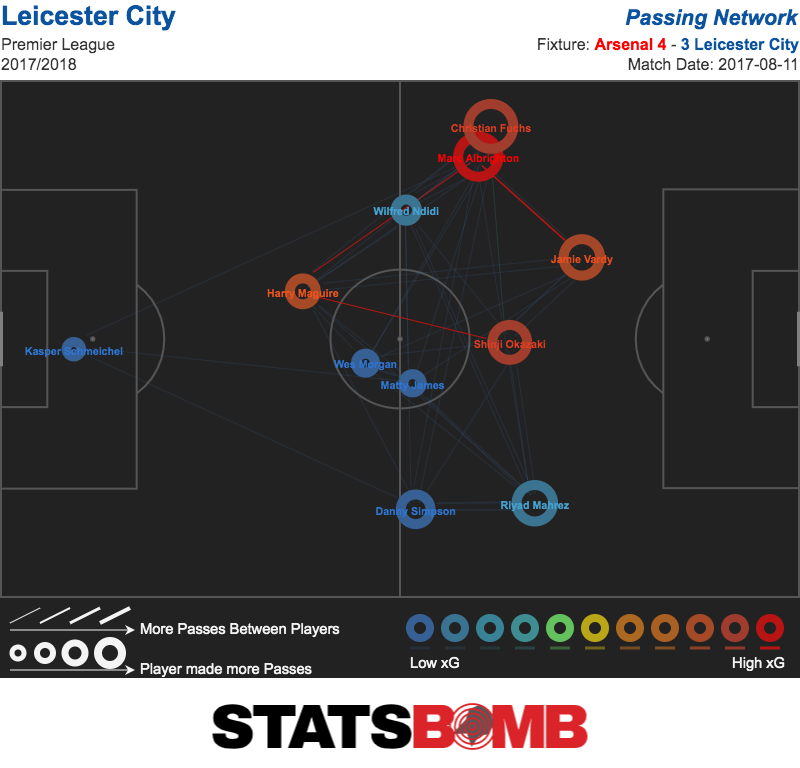

With football suspended for the foreseeable future, in the coming weeks this column will take a look at matches from past years. First up is a thrilling season opener that defined the end of two clubs’ most iconic eras. Two and a half years is an awfully long time in football. Take this game as an example. Of the 28 players involved over 90 minutes, only eight still regularly play for Arsenal or Leicester City. The game was won by Arsène Wenger bringing on Aaron Ramsey, Olivier Giroud and Theo Walcott. Craig Shakespeare didn’t know how best to adjust after he substituted Shinji Okazaki. Doesn’t that feel like forever ago? This was at the height of Wenger’s very sudden and surprising switch to the 3-4-3 system. The Frenchman was so often an innovator, thinking about the game differently to others and finding new solutions to his team's problems, that this felt totally out of character. The logic behind the switch seemed to be that Antonio Conte’s Chelsea had just won the league playing in that shape, and everyone else was flirting with it, so it might be worth a go? They were certainly committed. The first half pass map below shows wing backs Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and Héctor Bellerín pushed right up. Sead Kolašinac is a little more advanced than the other centre backs, but he’s still very much part of a back three.  For Leicester, the pass map is a little less illuminating because they had few spells of sustained possession, so you’ll have to take my word for it. They played the classic title-winning Leicester setup, with a small tweak. The side set up with their conventional back four, though Harry Maguire had replaced Robert Huth by this point. Wilfried Ndidi and (in a rare outing) Matty James replaced N’Golo Kanté and Danny Drinkwater in central midfield, but the idea was the same. Riyad Mahrez and Marc Albrighton were both tucked in as wide midfielders, with Mahrez obviously the one with licence to attack. The change here is that Okazaki often pushed right up alongside Jamie Vardy. Presumably Shakespeare felt Arsenal’s back three of Rob Holding, Nacho Monreal and Kolašinac wasn't exactly secure and could be exploited by two genuine strikers. He was right.

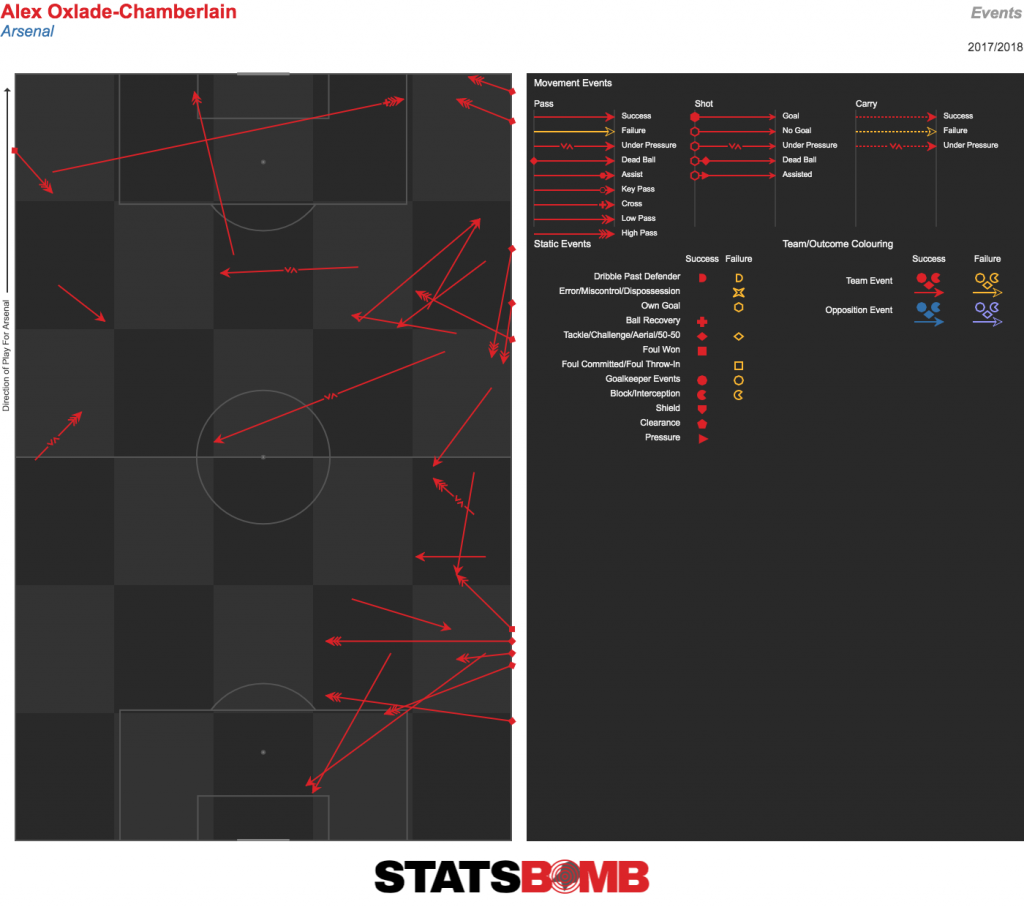

For Leicester, the pass map is a little less illuminating because they had few spells of sustained possession, so you’ll have to take my word for it. They played the classic title-winning Leicester setup, with a small tweak. The side set up with their conventional back four, though Harry Maguire had replaced Robert Huth by this point. Wilfried Ndidi and (in a rare outing) Matty James replaced N’Golo Kanté and Danny Drinkwater in central midfield, but the idea was the same. Riyad Mahrez and Marc Albrighton were both tucked in as wide midfielders, with Mahrez obviously the one with licence to attack. The change here is that Okazaki often pushed right up alongside Jamie Vardy. Presumably Shakespeare felt Arsenal’s back three of Rob Holding, Nacho Monreal and Kolašinac wasn't exactly secure and could be exploited by two genuine strikers. He was right.  From an Arsenal perspective, the biggest story of the match was quintessentially Wenger. It’s no secret that his sides weren’t exactly tactically structured, and he allowed his players a lot of freedom to make their own choices during games rather than strictly cohere to a system. The good side of this was evident, with Arsenal involving themselves in several intricate exchanges of play, best exemplified by Danny Welbeck’s 47th-minute equaliser. But they didn’t really have a clear idea of how to break down Leicester’s deep block. Their shape was actually a good fit for this game. With Leicester in their narrow 4-4-2, Arsenal could theoretically keep the two wingbacks very wide to stretch the play without having a numerical disadvantage in midfield. But Wenger’s players never really held consistent positions. Oxlade-Chamberlain at left wing back had the chance to be a real outlet, staying wide and offering crossfield passes as well as crossing opportunities, opening up space as Leicester’s compact shape deals with him. But his natural instinct is to come inside and involve himself in central areas. A big part of why he left Arsenal was to play in central midfield rather than being shunted out to left wing back in games like this, and watching him here it's clear he felt he could do more damage if he drifted into that role. But perhaps he was just too right-footed to really do a job staying wide on the left. The graphic below shows his successful left footed passes in the game. He actually used that foot more late on, when he was moved to right back, than in the majority of the time when he was actually on the left flank. You’d never know what position he was playing from this. He’s a huge downgrade on Oxlade-Chamberlain in a lot of ways, but I can’t help but feel Wenger had to start the very left-footed Kolašinac in that role, perhaps with Shkodran Mustafi coming in at centre back. It would be worse in terms of player ability, but it would at least allow them to create real width on that side.

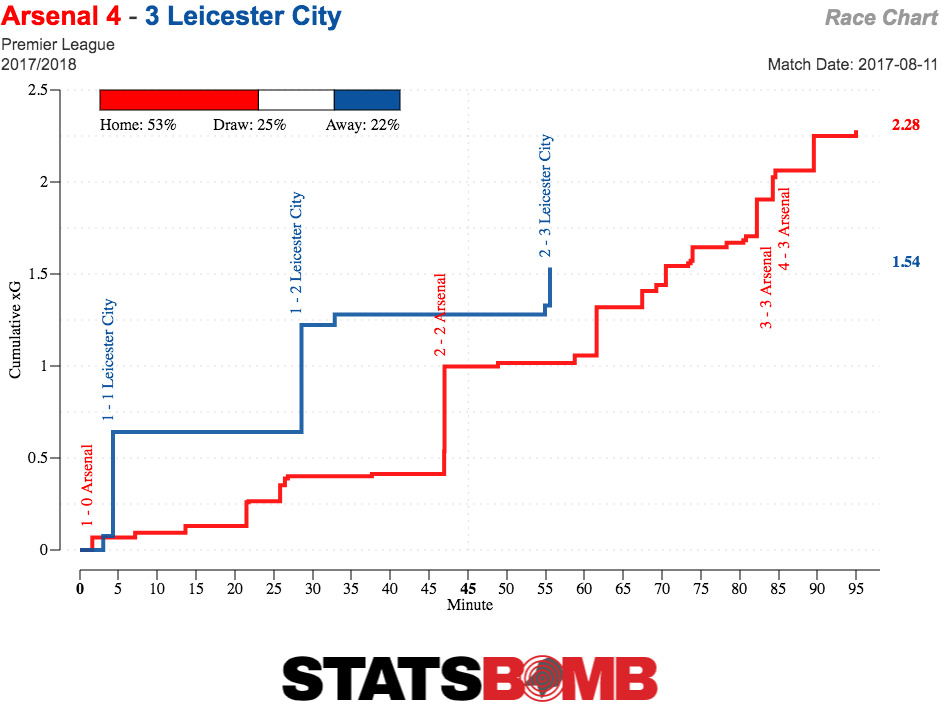

From an Arsenal perspective, the biggest story of the match was quintessentially Wenger. It’s no secret that his sides weren’t exactly tactically structured, and he allowed his players a lot of freedom to make their own choices during games rather than strictly cohere to a system. The good side of this was evident, with Arsenal involving themselves in several intricate exchanges of play, best exemplified by Danny Welbeck’s 47th-minute equaliser. But they didn’t really have a clear idea of how to break down Leicester’s deep block. Their shape was actually a good fit for this game. With Leicester in their narrow 4-4-2, Arsenal could theoretically keep the two wingbacks very wide to stretch the play without having a numerical disadvantage in midfield. But Wenger’s players never really held consistent positions. Oxlade-Chamberlain at left wing back had the chance to be a real outlet, staying wide and offering crossfield passes as well as crossing opportunities, opening up space as Leicester’s compact shape deals with him. But his natural instinct is to come inside and involve himself in central areas. A big part of why he left Arsenal was to play in central midfield rather than being shunted out to left wing back in games like this, and watching him here it's clear he felt he could do more damage if he drifted into that role. But perhaps he was just too right-footed to really do a job staying wide on the left. The graphic below shows his successful left footed passes in the game. He actually used that foot more late on, when he was moved to right back, than in the majority of the time when he was actually on the left flank. You’d never know what position he was playing from this. He’s a huge downgrade on Oxlade-Chamberlain in a lot of ways, but I can’t help but feel Wenger had to start the very left-footed Kolašinac in that role, perhaps with Shkodran Mustafi coming in at centre back. It would be worse in terms of player ability, but it would at least allow them to create real width on that side.  Leicester, on the other hand, knew exactly what they wanted to do. The Shakespeare era was about getting back to basics, sticking with the deep-defending, counter-attacking 4-4-2 that served them so well in 2015–16. The plan was to keep a compact shape without the ball, then use Vardy’s pace on the counter with it. We've seen them do this a million times. The problem is that they just weren’t anywhere near as good at it by this point. James and Ndidi didn’t hold disciplined positions as Drinkwater and Kanté once did. The shape of the side rarely seemed well drilled. Arsenal were easily able to get the ball up the pitch in transition moments, which didn’t happen nearly as often when Leicester were at their best. Thus the pattern of the game was of Arsenal not having a plan to break down the deep block, but the deep block being so poorly organised that it didn’t matter. It’s a huge understatement to say substitutions played a role in this game. Both sides made three, and all came after an hour. To understand how much of a shift occurred, look at when Leicester stopped taking shots on the race chart.

Leicester, on the other hand, knew exactly what they wanted to do. The Shakespeare era was about getting back to basics, sticking with the deep-defending, counter-attacking 4-4-2 that served them so well in 2015–16. The plan was to keep a compact shape without the ball, then use Vardy’s pace on the counter with it. We've seen them do this a million times. The problem is that they just weren’t anywhere near as good at it by this point. James and Ndidi didn’t hold disciplined positions as Drinkwater and Kanté once did. The shape of the side rarely seemed well drilled. Arsenal were easily able to get the ball up the pitch in transition moments, which didn’t happen nearly as often when Leicester were at their best. Thus the pattern of the game was of Arsenal not having a plan to break down the deep block, but the deep block being so poorly organised that it didn’t matter. It’s a huge understatement to say substitutions played a role in this game. Both sides made three, and all came after an hour. To understand how much of a shift occurred, look at when Leicester stopped taking shots on the race chart.  With Leicester winning 3–2 Shakespeare initially looked to tighten things up in midfield by bringing on Daniel Amartey for Okazaki. He undid this plan less than ten minutes later, substituting James for Kelechi Iheanacho. He had a chance to slow the game down and solidify the win, but chose not to take it. Wenger, meanwhile, was much more proactive about changing his system. He switched to a back four (a very makeshift one, granted), with Granit Xhaka and Aaron Ramsey as a double pivot, Alexandre Lacazette out to the left wing, Walcott on the right and Mesut Özil behind Giroud. This is much more classic late-era Wenger. Being able to get the ball directly to Giroud, with Ramsey making runs into the box from midfield, worked a treat, though it would have cost them significantly had Leicester not been so poor late on. It might be Wenger in a nutshell: He didn’t have a clear tactical plan, but he stumbled onto something that worked. As is often the case with high-scoring fixtures, this wasn’t a great game in terms of the sides’ tactics. And neither manager lasted much longer. Shakespeare didn’t really develop a plan for Leicester beyond “stick what worked before, but worse”. His replacement, Claude Puel, was forgotten about five minutes after he left, but he did at least bring a fresh pair of eyes to evaluate the squad rather than trying to recreate hazy memories of the miraculous title-winning season. Of course, Wenger left at the end of the season to make way for Unai Emery. The Spaniard tried to give Arsenal a clearer plan in games, but he was so insistent on tweaking it for the opposition that the players never seemed to know exactly what they were supposed to be doing. Wenger’s model of allowing the players more freedom to express themselves was at least a philosophy, and watching this game I was struck by how much more enjoyable this Arsenal team were than what’s come since. I doubt Wenger could have ever turned things around. If he were managing Arsenal today, the lack of structure in possession against deep blocks would be a real issue. But this was an Arsenal team that were genuinely fun to watch despite their shortcomings, and a Leicester that still had some of their most famous identity.

With Leicester winning 3–2 Shakespeare initially looked to tighten things up in midfield by bringing on Daniel Amartey for Okazaki. He undid this plan less than ten minutes later, substituting James for Kelechi Iheanacho. He had a chance to slow the game down and solidify the win, but chose not to take it. Wenger, meanwhile, was much more proactive about changing his system. He switched to a back four (a very makeshift one, granted), with Granit Xhaka and Aaron Ramsey as a double pivot, Alexandre Lacazette out to the left wing, Walcott on the right and Mesut Özil behind Giroud. This is much more classic late-era Wenger. Being able to get the ball directly to Giroud, with Ramsey making runs into the box from midfield, worked a treat, though it would have cost them significantly had Leicester not been so poor late on. It might be Wenger in a nutshell: He didn’t have a clear tactical plan, but he stumbled onto something that worked. As is often the case with high-scoring fixtures, this wasn’t a great game in terms of the sides’ tactics. And neither manager lasted much longer. Shakespeare didn’t really develop a plan for Leicester beyond “stick what worked before, but worse”. His replacement, Claude Puel, was forgotten about five minutes after he left, but he did at least bring a fresh pair of eyes to evaluate the squad rather than trying to recreate hazy memories of the miraculous title-winning season. Of course, Wenger left at the end of the season to make way for Unai Emery. The Spaniard tried to give Arsenal a clearer plan in games, but he was so insistent on tweaking it for the opposition that the players never seemed to know exactly what they were supposed to be doing. Wenger’s model of allowing the players more freedom to express themselves was at least a philosophy, and watching this game I was struck by how much more enjoyable this Arsenal team were than what’s come since. I doubt Wenger could have ever turned things around. If he were managing Arsenal today, the lack of structure in possession against deep blocks would be a real issue. But this was an Arsenal team that were genuinely fun to watch despite their shortcomings, and a Leicester that still had some of their most famous identity.

2020

Classic Game Rewind: Arsenal 4–3 Leicester City, August 2017

By admin

|

March 18, 2020