The suspension of modern football has given us time to go back and collect data from some older matches. Amongst other things, it can be used to look at some the game’s greats from a different perspective. Diego Maradona certainly fits into that group. Some will no doubt consider it sacrilegious to wrestle a player who inspires such a viscerally emotional response into the realm of expected goals, deep progressions and pressure events, but here we are. What can we glean from the limited five-match sample we have in our system?

A Battle in the Bernabéu

The first Maradona match we have collected is the infamous 1984 Copa del Rey final between Athletic Club and his Barcelona side. This isn’t really early stage Maradona. He was eight years into a career that had begun at 15 at Argentinos Juniors, and that had already yielded a league title at Boca Juniors, a starting role at the 1982 World Cup and a world-record move to Spain. It is, though, before what is generally considered to be his true peak.

That may partly be for reasons of circumstance. There were some highs for Maradona in his two-year spell at Barcelona. He had provided the assist for the opening goal in a lively performance in their victory over Real Madrid in the previous year’s final, and earned applause for a cheeky pause before finishing against the same opponents away in the league. But illness and injury prevented him from ever building up much rhythm.

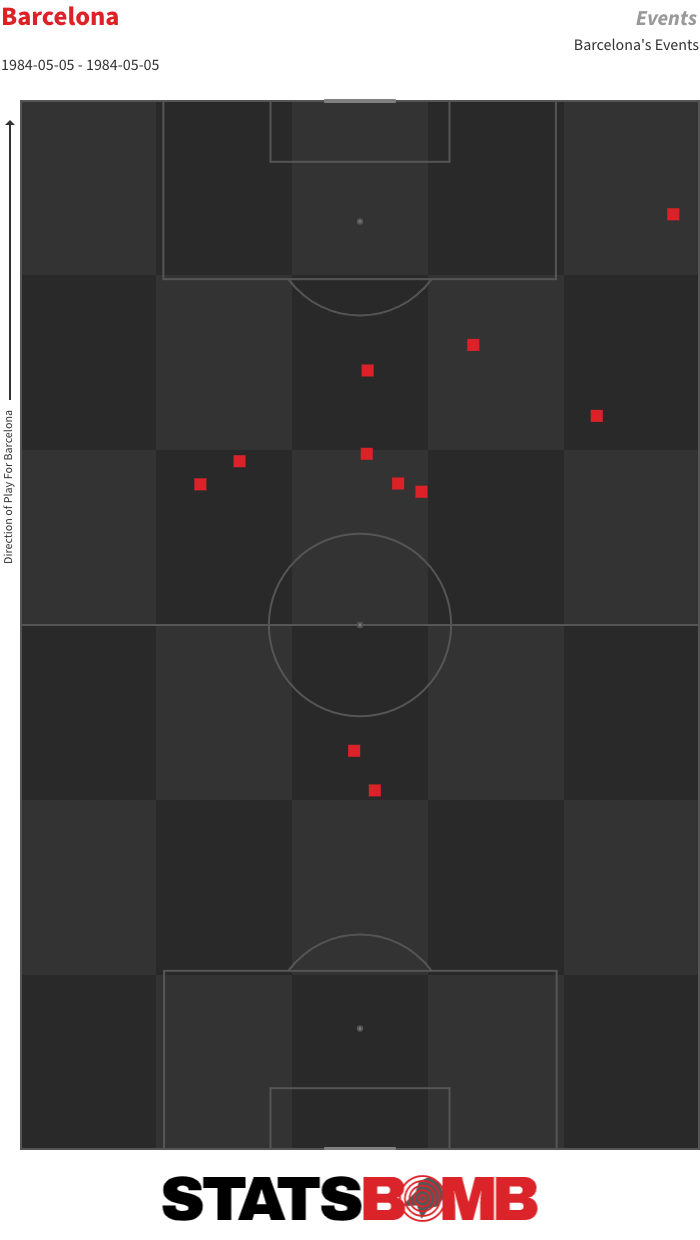

It is no wonder he struggled with injuries when you see the punishment he endured in this match. Eight months earlier he had been on the receiving end of a brutal sliding foul from Athletic’s Andoni Goikoetxea that had kept him out of action for three months. The challenges were similarly rough in this one. Even in the context of a generally ill-tempered encounter, with 32 fouls committed by Athletic and 21 by Barcelona (as a basis of comparison, there were just 30 fouls in total when the sides met in the quarter-final of the 2019/20 competition), Maradona seemed to be singled out. He was fouled nearly three times as often as any of his teammates. Eleven times in total.

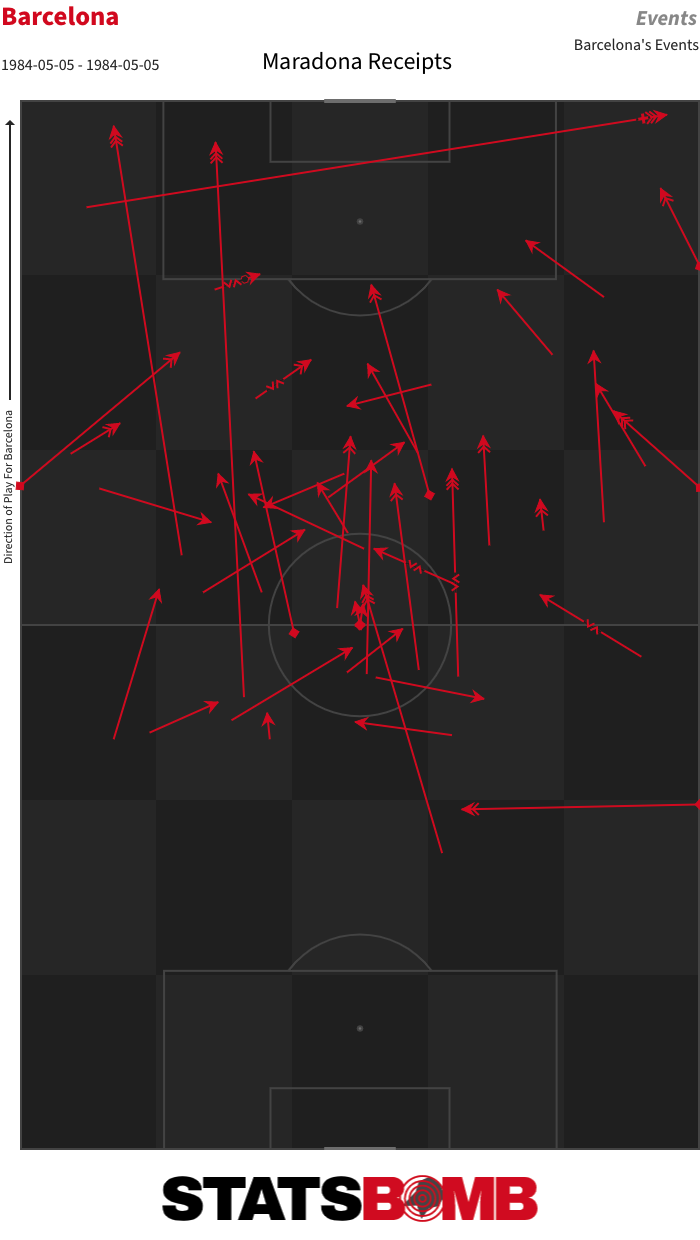

The majority of those came as he received with his back to goal, most of them courtesy of the close and aggressive marking of Iñigo Liceranzu, whose litany of fouls were all at least booking worthy in their own right by modern standards. Not to mention his other unpunished hacks as play moved on. In a way, Maradona had the misfortune of being caught in a transitory period between the even rougher defending Pelé et al often had to contend with in the 1960s and the incredible fitness and preparation advances of the modern era.

In his time, players were becoming more athletic and spaces on the pitch were reducing, but refereeing wasn’t yet as stringent as it would later become. The decision of coach and compatriot César Luis Menotti to field him as a lone central striker does him no favours. It was an idea Menotti also used at the 1982 World Cup, and which there too left Maradona at the mercy of opposing defenders when he received with his back to goal. He spends much of this match either being fouled or trying to engineer first-time layoffs to teammates as he hops up to avoid swiping legs.

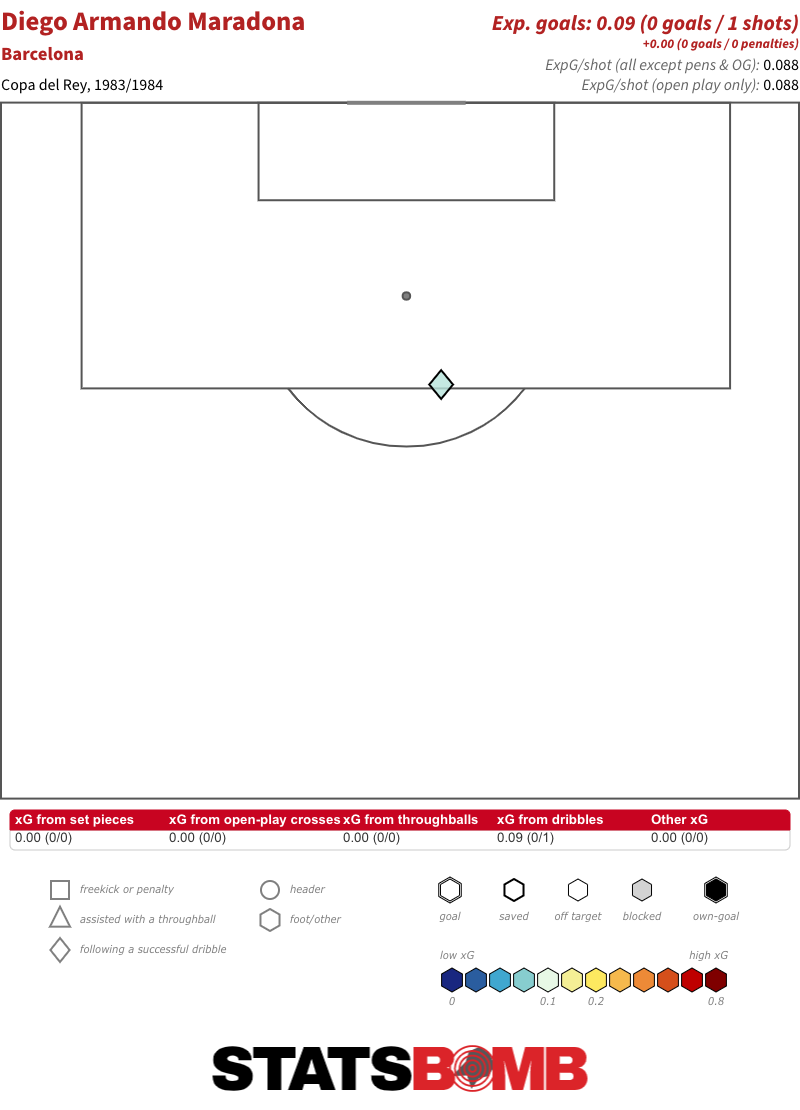

Barcelona struggle to make much attacking progress. Despite Bernd Schuster’s constant probing, including nine attempts to link directly with Maradona, they are just unable to pierce the defence of an Athletic side who won the league and cup double this season. Maradona musters just one shot and one key pass.

Bogged down by the system and circumstances, frustrated at his inability to influence the outcome, Maradona snaps at the final whistle, kicking off an ugly brawl that contributed heavily to the early termination of his relationship with Barcelona.

Peak Maradona

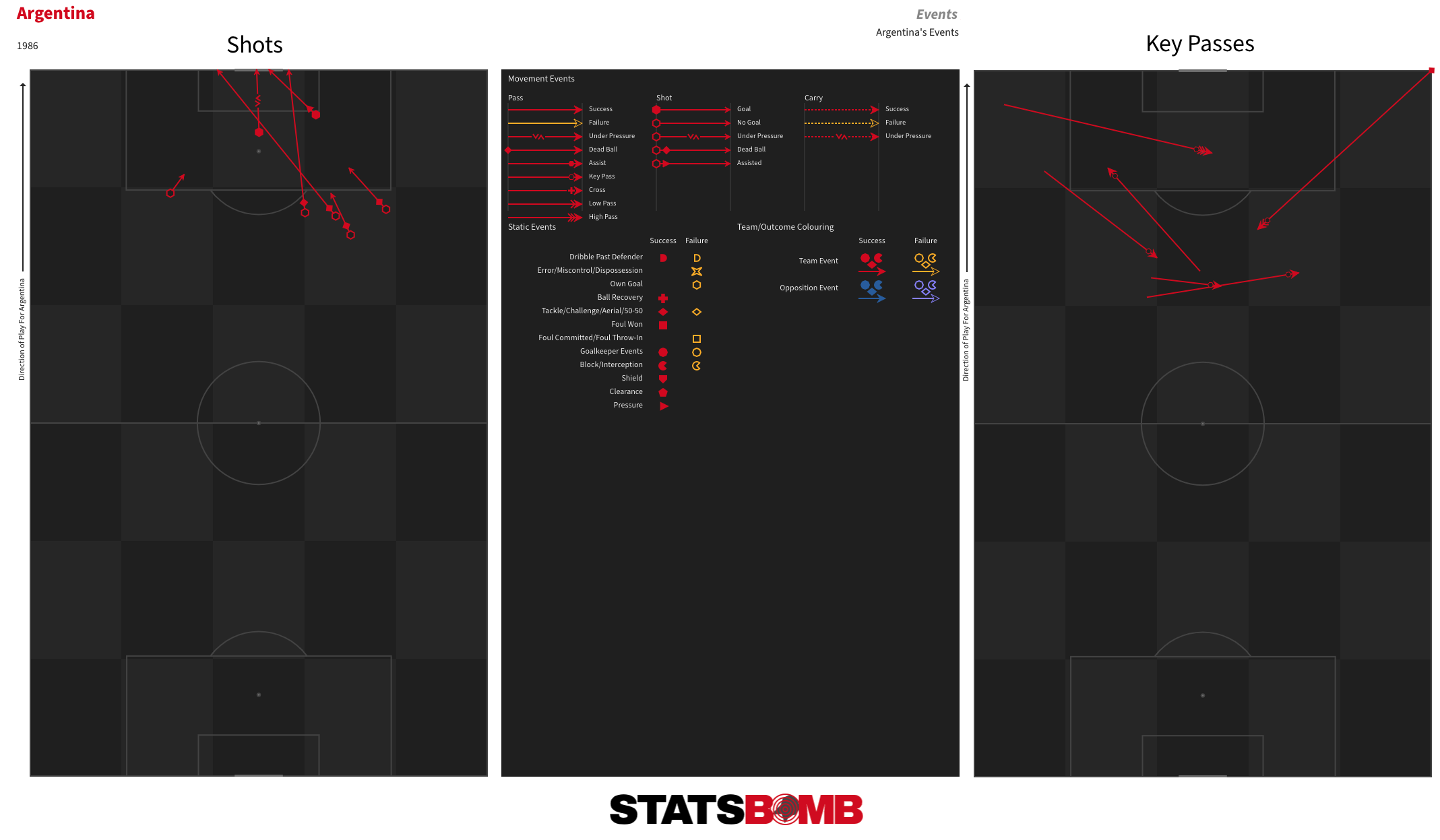

Perhaps no match epitomises peak-era Maradona more than Argentina’s 2-1 win over England in the quarter-final of the 1986 World Cup. Everything is there: the deceit, the trickery and above all, the outright brilliance. The narrative around Argentina’s triumph in this tournament has often been that Maradona dragged an otherwise ordinary team to victory. In the attacking sphere, at least, he certainly had an outsize influence. He scored or assisted nearly three-quarters of Argentina’s goals, and his dominance of their offensive output is clear in this match. Argentina had 15 shots, 13 of which were taken or assisted by Maradona.

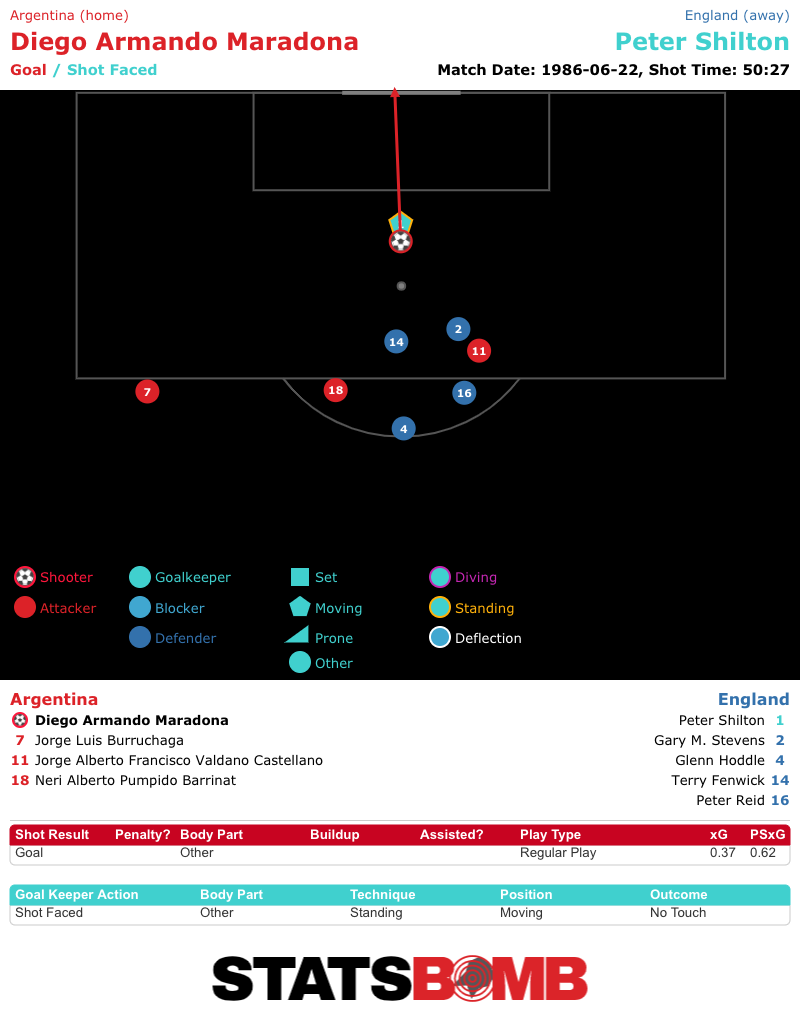

Of course, he also scored the two goals that led them to victory. The first... well, you probably know how that went down. Notice the body part: Other.

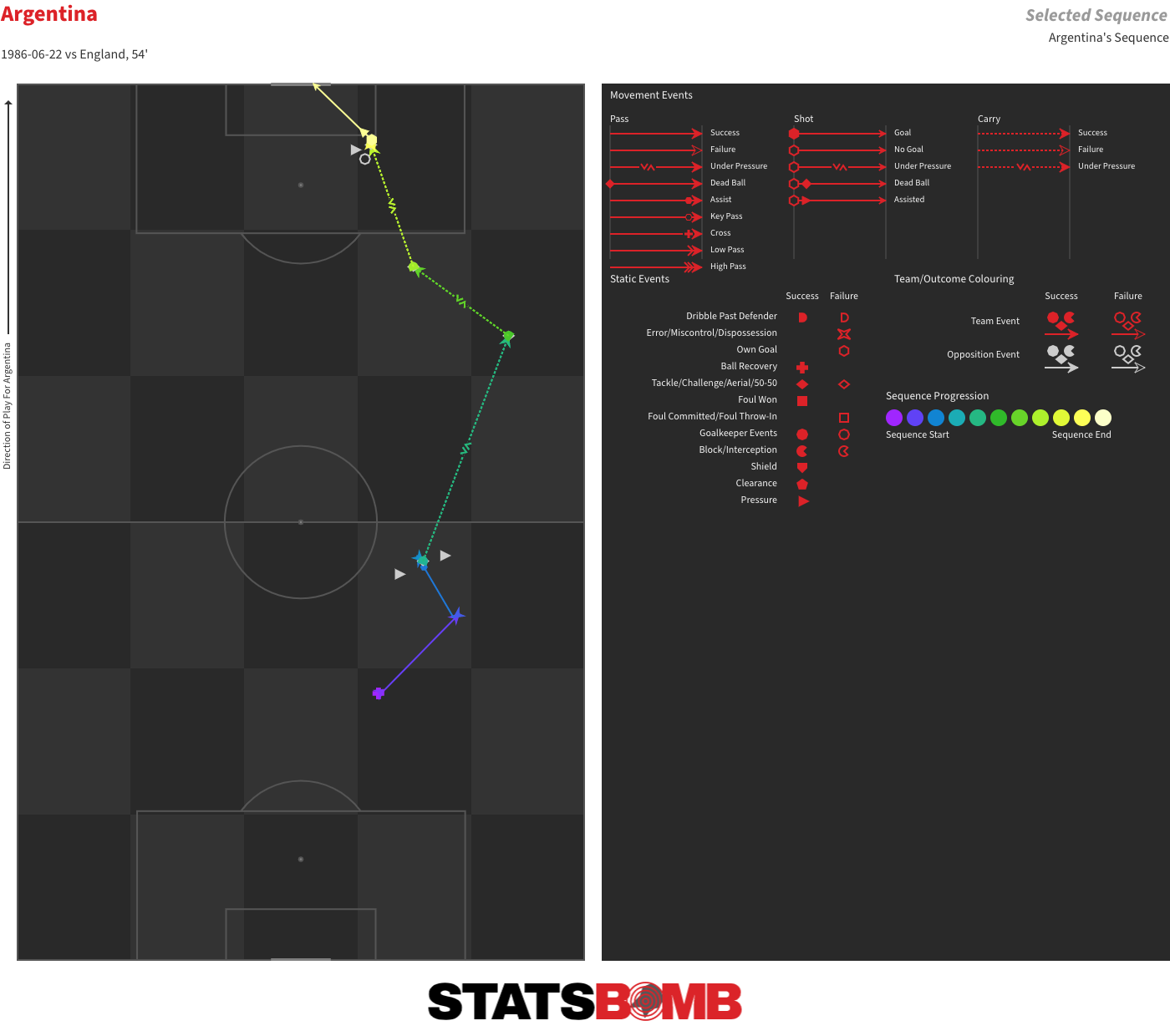

His second was one of the finest goals in the history of the sport.

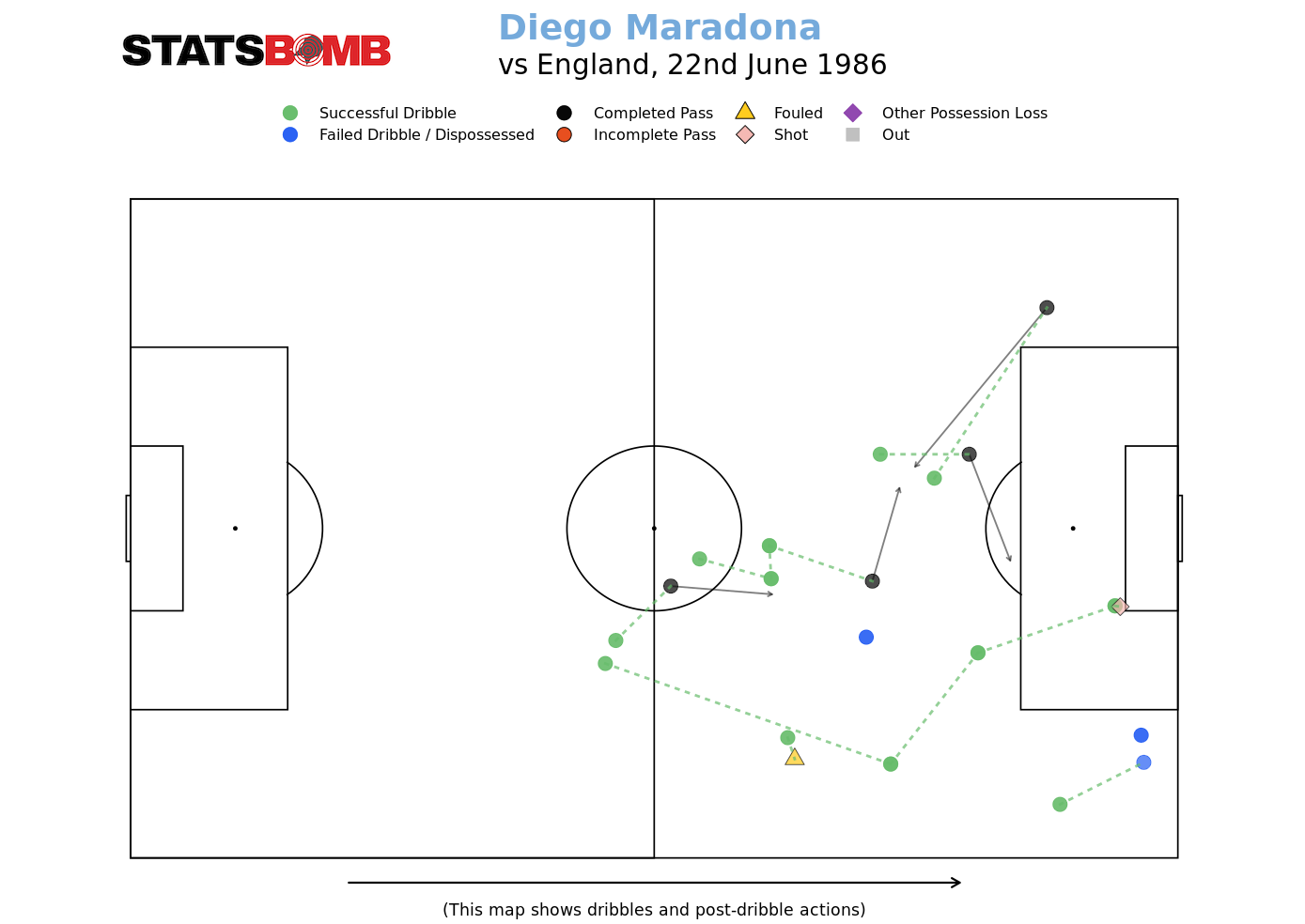

Maradona completed more successful dribbles (four) on the run leading to that goal than over 95% of current-day, big-five-league attacking midfielders and wingers do over the course of a full 90 minutes. On the day, he completed 12 of his 14 attempted dribbles. Whenever he picked up the ball and ran with it, England were unable to stop him.

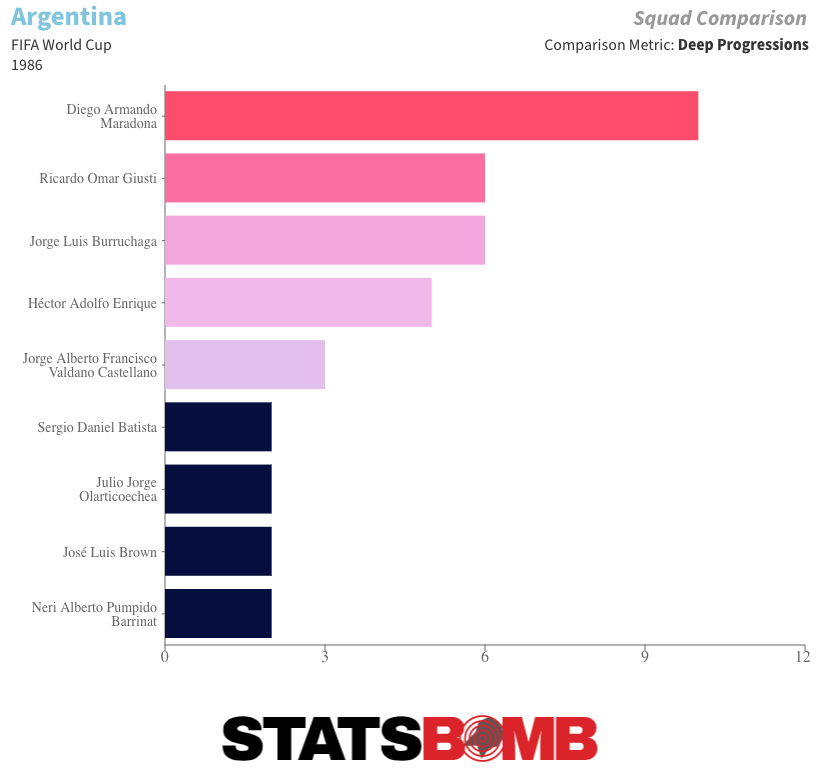

Maradona was relentlessly positive throughout, consistently seeking to move forward off the pass, dribble or carry. Not only did he provide pretty much all of Argentina’s attacking output, he was also the player who most often moved the ball into the final third.

There were some good players on this Argentina team, many of whom were successful at a continental level in South America or had already or would soon earn moves to Europe. Coach Carlos Bilardo also introduced a neat formational quirk, switching to a 3-5-1-1 shape he had previously experimented with for the final three matches of the tournament.

This will, though, always be remembered as Maradona’s World Cup. From the data we have available from this match, it is difficult to argue against the idea that he took on a greater than normal level of responsibility in this team -- a level of responsibility that is almost impossible to replicate in the hyper-active modern game. The second match in our system that falls within Maradona’s peak is the second leg of Napoli’s triumph over Atalanta in the final of the 1986/87 Coppa Italia -- one that confirmed their domestic double that season.

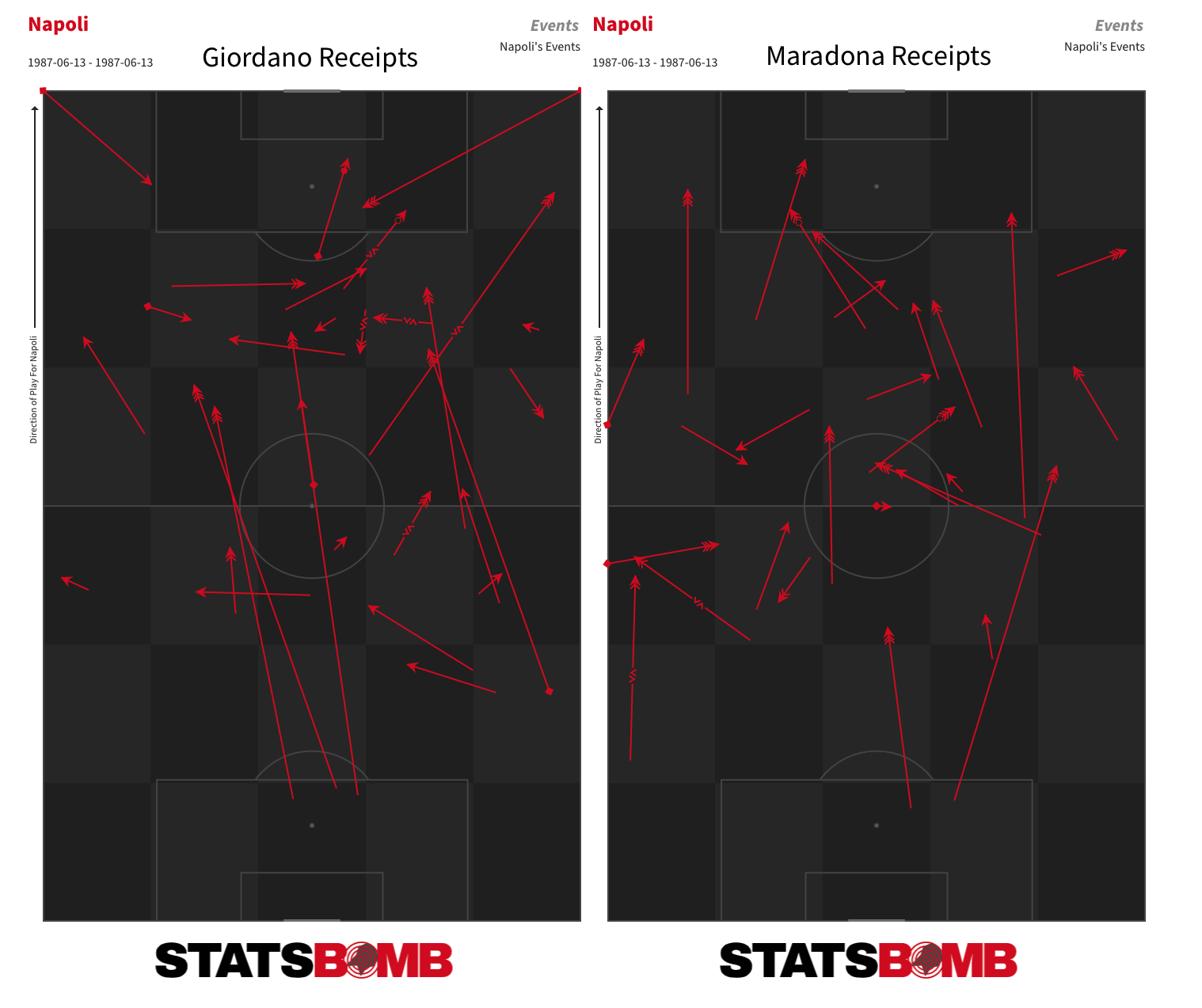

This is probably less representative than the England match. Napoli were already 3-0 up from the first leg, so there was little need for him to so aggressively carry the team on his back. Again, though, as with Jorge Valdano and Argentina, he benefits from having another forward alongside and ahead of him to act as both a primary reference point and an upfield runner. The large majority of the long central passes are aimed up to Bruno Giordano. The longer balls Maradona receives are into the channels, and he otherwise involves himself where he fancies, instead of being limited to a fixed starting point.

Mature Maradona

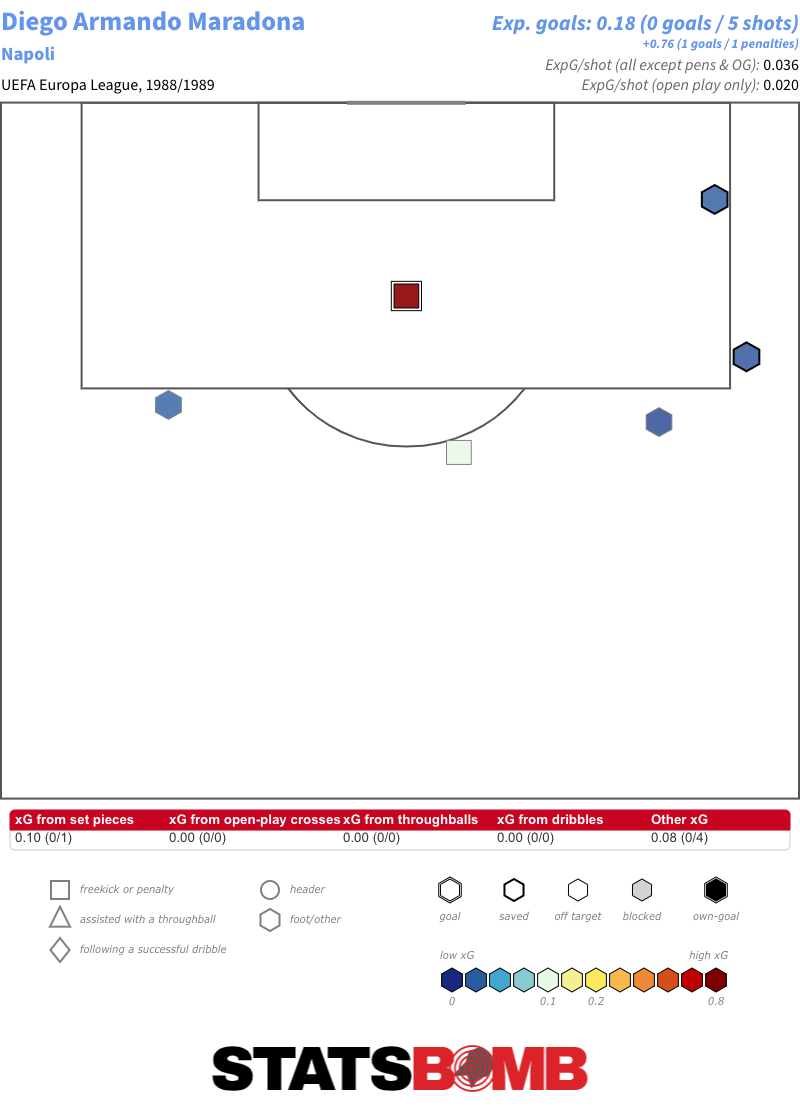

The final two matches we have recorded are both from Napoli’s successful campaign in the 1989 UEFA Cup: the 3-0 win over Juventus in the second leg of their quarter-final and the 2-0 victory over Bayern Munich in the first of their semi-final. Maradona is only 28 at this point but arguably just 18 or so months away from the end of his serious top-level career.

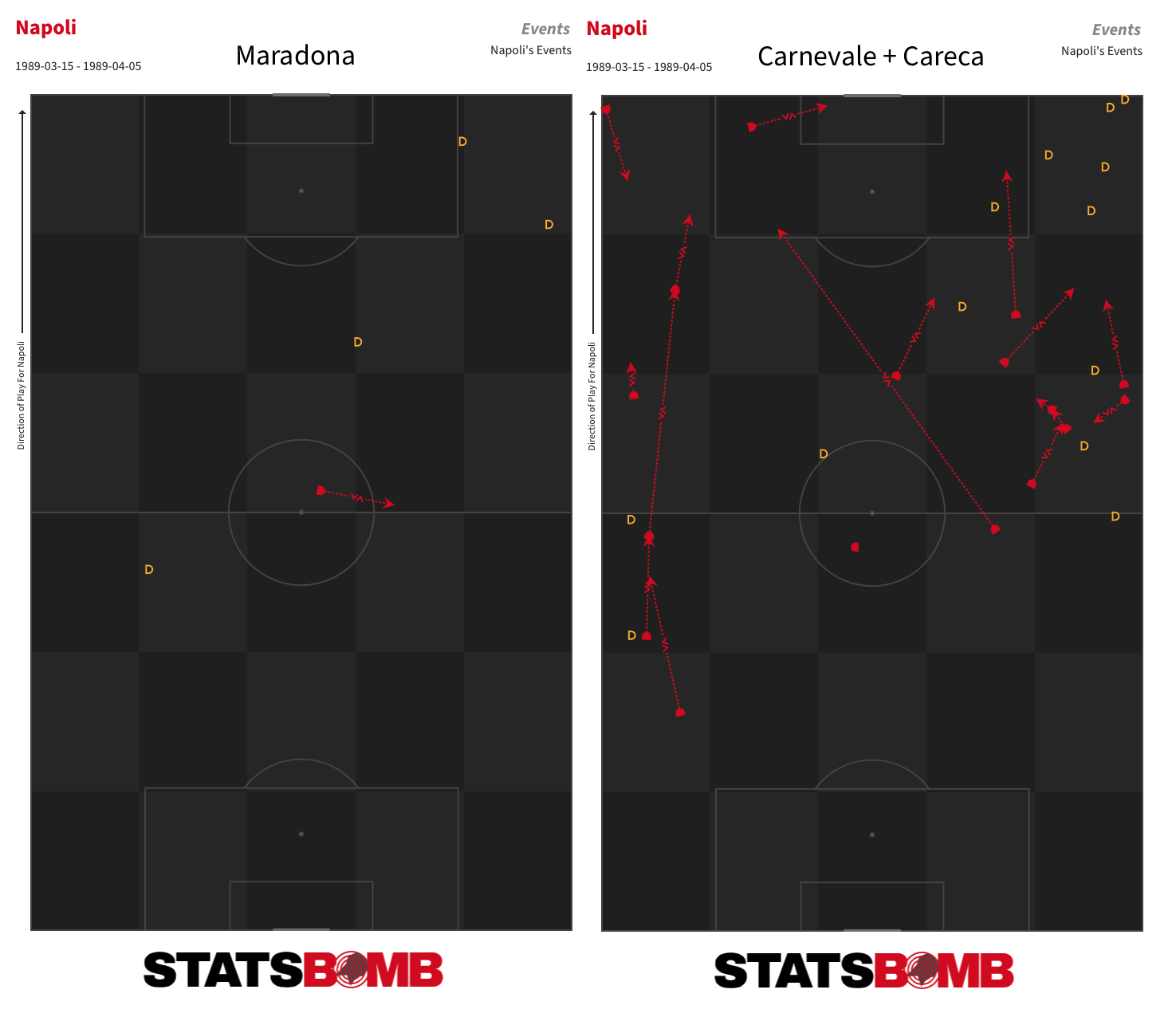

They display a Maradona who is still decisive but in a different way. He is much less reliant on his dribbling. After 12 attempted dribbles and seven successful ones for Barcelona against Athletic in 1984 and his bumper load against England two years later, he attempts only five dribbles and completes just one in these two matches in 1989. Andrea Carnevale and Careca do the majority of the dribbling on this Napoli side.

That isn’t to say that Maradona wasn’t still capable of game-changing dribbles, as his solo run to set up Claudio Cannigia for Argentina’s late winner against Brazil in the last 16 of the following year’s World Cup would attest, but he had certainly begun to ration them.

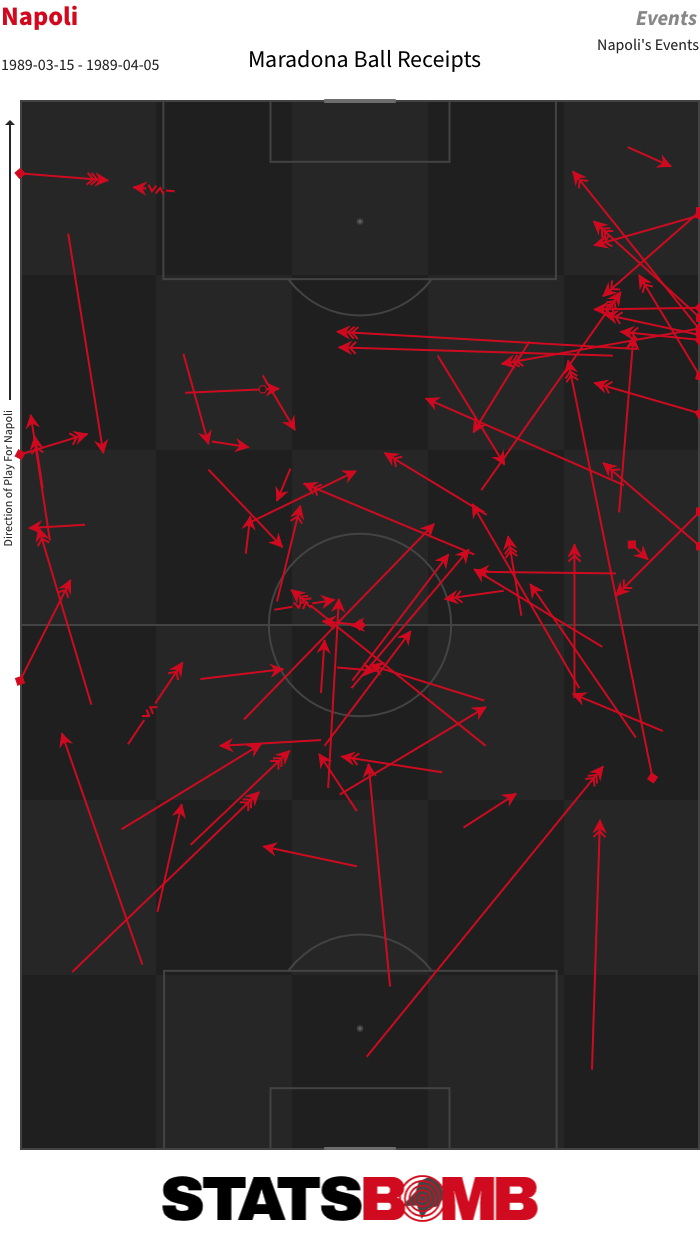

This later stage Maradona is much more likely to combine with teammates to advance upfield. Across 1984 and 1986 his ratio of passes to dribbles and carries fell in a range between 32 and 34%; across these two 1989 matches, it has increased significantly to 51.03%. He receives the ball more frequently in deeper areas.

We see a Maradona whose output has tilted towards ball progression and chance creation. No one moves the ball into the final third more often or creates more chances for teammates than he does over these two matches. While he does take five non-penalty shots, joint second on the team, they are all from speculative positions, and he only twice touches the ball inside the penalty area over the course of the two matches.

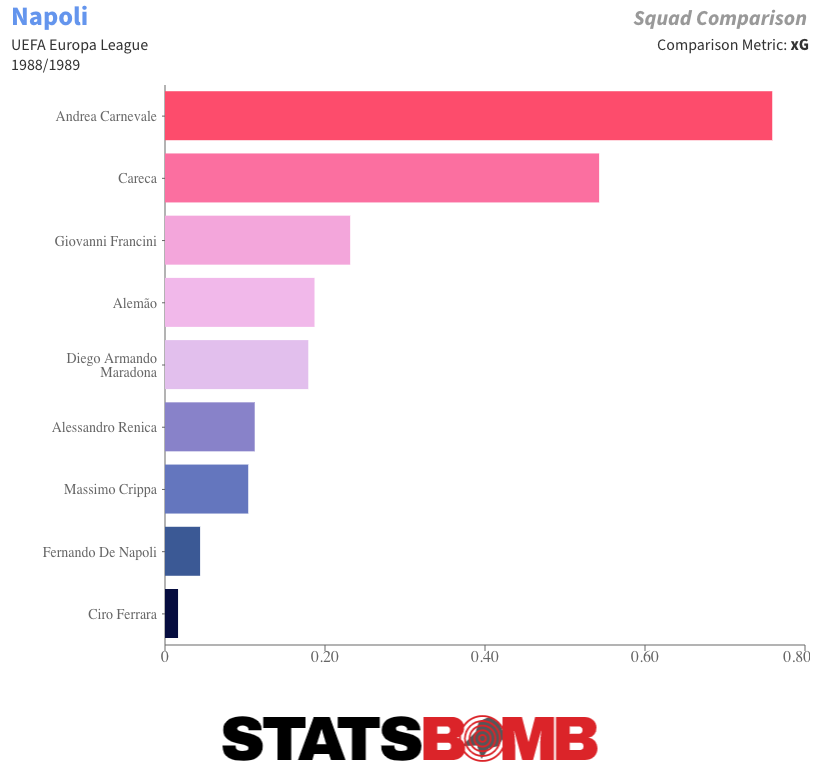

Careca and Carnevale both accumulate far higher expected goals (xG) totals.

Maradona had been the club’s top scorer in each of his first four seasons at Napoli. In this campaign, Careca took that honour, with more than double Maradona’s total, while Carnevale also scored four more than Maradona’s sum of nine. It is, though, worth mentioning that the following season, in which Napoli claimed their second and last league title with Maradona, he returned to the top of the scoring charts.