Our analysis of the evolution of Lionel Messi continues with another Clásico, two years down the line from the first. We are again joined by Álex Delmás, ex-footballer, analyst for Barça TV and La Vanguardia newspaper, and the author of the book Messi Táctico. Thanks to our Messi Data Biography we have data for all league matches involving Messi since his debut in 2004.

For this series, Álex has picked out three significant matches in Messi’s evolution as a footballer. Last time out, we analysed Messi’s first iteration in the context of the March 2007 Clásico at the Camp Nou. This time around, we are at the Santiago Bernabeu for Barcelona’s famous 6-2 victory in May 2009.

Nick Dorrington (ND) (editor of StatsBomb’s Spanish-language site): Hi Alex. Can you tell me why you picked this match?

Álex Delmás (AD): It is the match that changed Messi’s footballing life. In this match, Pep Guardiola hit upon a brainwave and positioned Messi centrally as a false nine for the first time, a move that elevated Messi’s football to an unmatchable level. He went from being one of the best players in the world to the undisputed best. To top things off, the collective performance in this match is absolutely brilliant. I sincerely think that it is one of the most tactically rich matches in the history of our sport.

ND: The term false nine now seems to form part of the standard football lexicon, but for those who don’t know what it means, could you give us an overview of what a false nine is and which systems it functions best in?

AD: In the false nine role, the player initially lines up as a centre forward, a nine, but doesn’t fulfil the functions that we’d expect of a player in that position. They start off in the centre forward position, but drop back from there as play evolves to act as an attacking midfielder. The role is strongly associated with a 4-3-3 or 3-4-3 system. It has to be utilised in a system with three forwards. At least in my opinion, it is impossible to correctly implement the role of a false nine without wide forwards on each side to pin back the opposition full-backs.

ND: It is worth mentioning that the idea of a free nine, a number nine who drops back to involve himself in the construction of play, wasn’t a new one. Contemporary reports describe the play of centre forwards like Adolfo Pedernera, Nándor Hidekuti or even Alfredo di Stefano in a way that suggests that in the present day we might describe them as false nines. And didn’t Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona side, the Dream Team, often play with Michael Laudrup in a very similar role?

AD: I haven’t ever seen the others you mentioned play, but I did watch the Dream Team and it is true that Cruyff’s side often played with Laudrup as a false nine, and with good results too. In fact, in the 1992 European Cup final at Wembley, the team started with Laudrup as a false nine. Once Romario arrived that variation disappeared or was at least used very sparingly thereafter.

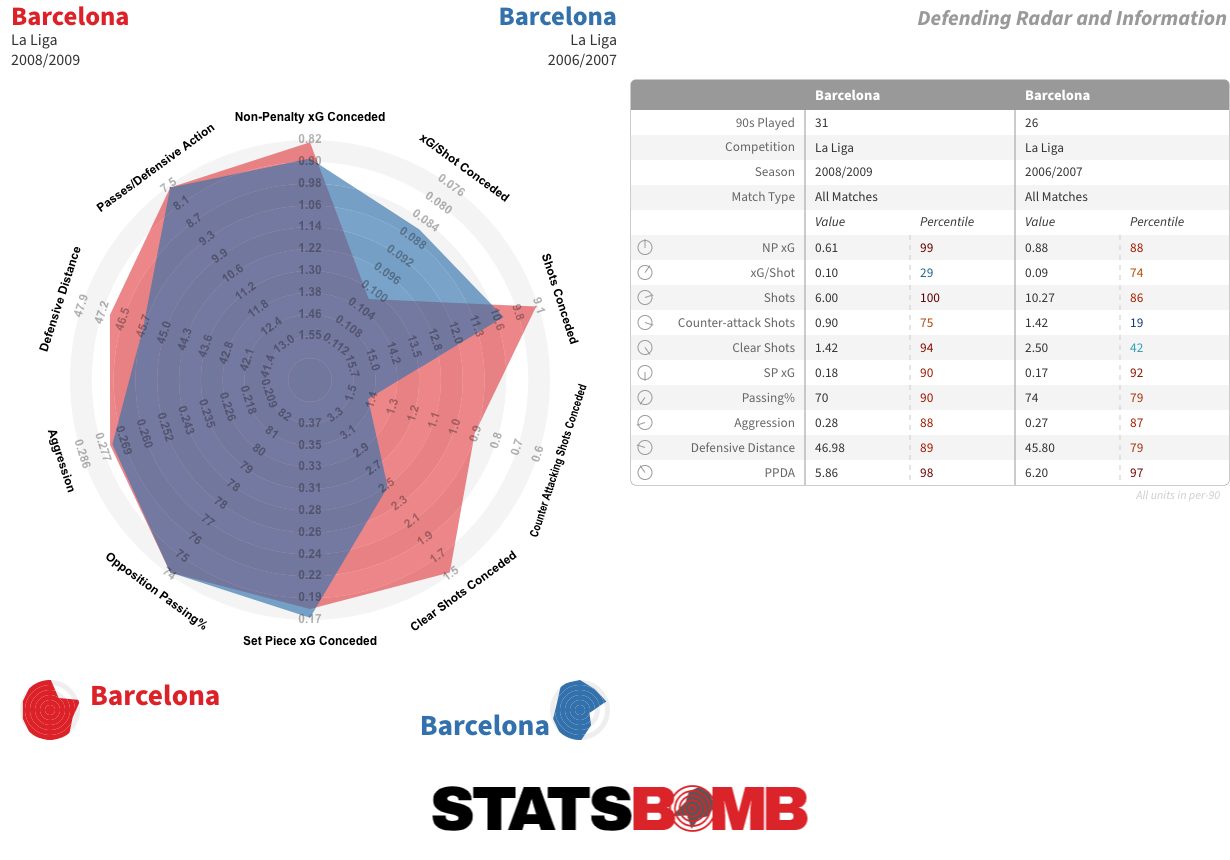

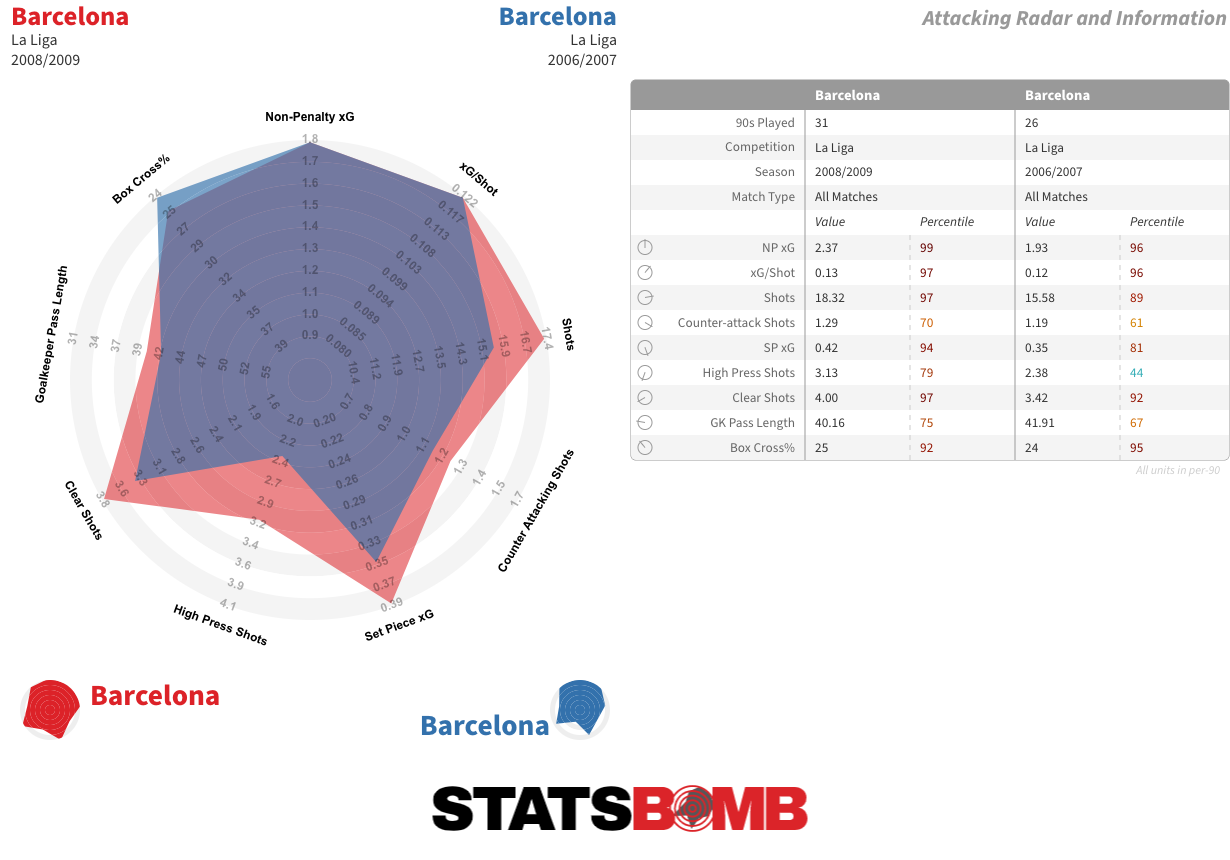

ND: Before we talk about how Messi functioned in that role, let’s first talk about the differences between the Barcelona of Frank Rijkaard that we analysed in part one of this series and this version, with Guardiola as head coach. The data tells us that this 2008-09 Barcelona side defended higher up and slightly more proactively than the 2006-07 team. Incredibly, they only gave up an average of six shots per match, four less than the 2006-07 team and less than any other Barcelona side in our database.

In attack, they took over three more shots per match than the Rijkaard team and did so from better average positions.

This Barça, who won the treble of La Liga, the Copa del Rey and the Champions League, has the best expected goal difference (xGD) of any Barcelona team in our database. Another treble-winning outfit, the 2014-15 side, stands second by that measure. Can you add anything else from a tactical standpoint?

AD: For me, they are a historic team. Of all the teams I’ve seen, they are the one who did most things well. It is true that football is for the footballers, and in this team there was such an accumulation of talent that they were nearly unstoppable. But there were also a lot of tactical details, many of them revolutionary. Guardiola implemented new ideas and perfected pre-existing ones. Perhaps the most valuable thing about this team is that they demonstrated that in football everything is related. That attacking and defending go hand in hand, and that if you attack well in an organised fashion it requires less effort to defend effectively thereafter. This Barcelona side perfectly applied the principles of positional play (juego de posición). They were a team who occupied space in a very rational manner and that made it easier for them to construct attacks.

ND: We are going a little bit off course here but could you explain, in simple terms, what positional play is and how it functions?

AD: In reality, we’d need a whole article to explain it properly! To put it in basic terms: in positional play, the positioning of every player has an effect on the team’s collective play. All of the players know exactly where they should position themselves, and they respect that positioning for the good of the team. For example, the wide forwards have to stay out wide even if they don’t receive the ball because their mere presence there widens the scope of the attack and pins down an opponent.

ND: That last point is something we clearly see in this match.

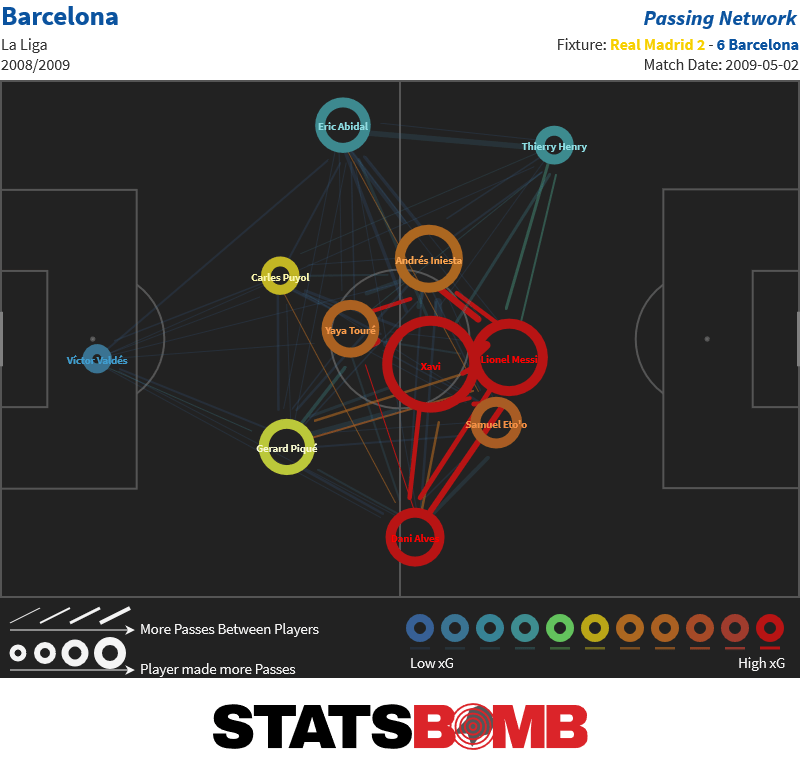

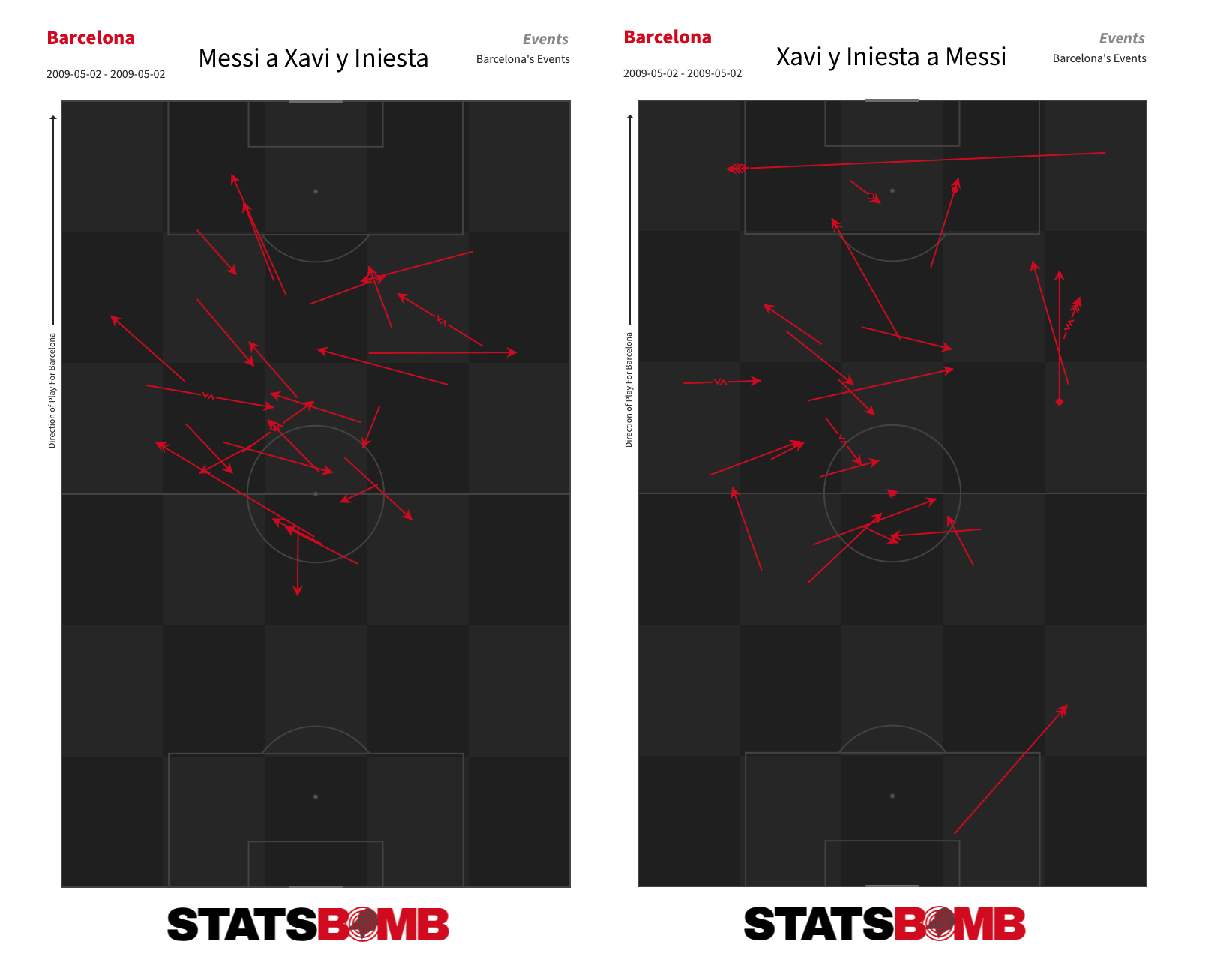

AD: Yes. Guardiola’s game plan was based around it, in fact. He positioned Messi as a false nine so that he could drop off to receive between the lines, and then instructed the two wide forwards, Thierry Henry and Samuel Eto’o, to consistently make runs in behind from the flanks. The pass map for this match shows just that. We can see that Messi is very close to Xavi and Iniesta in the centre, while Henry holds a very high and wide position on the left.

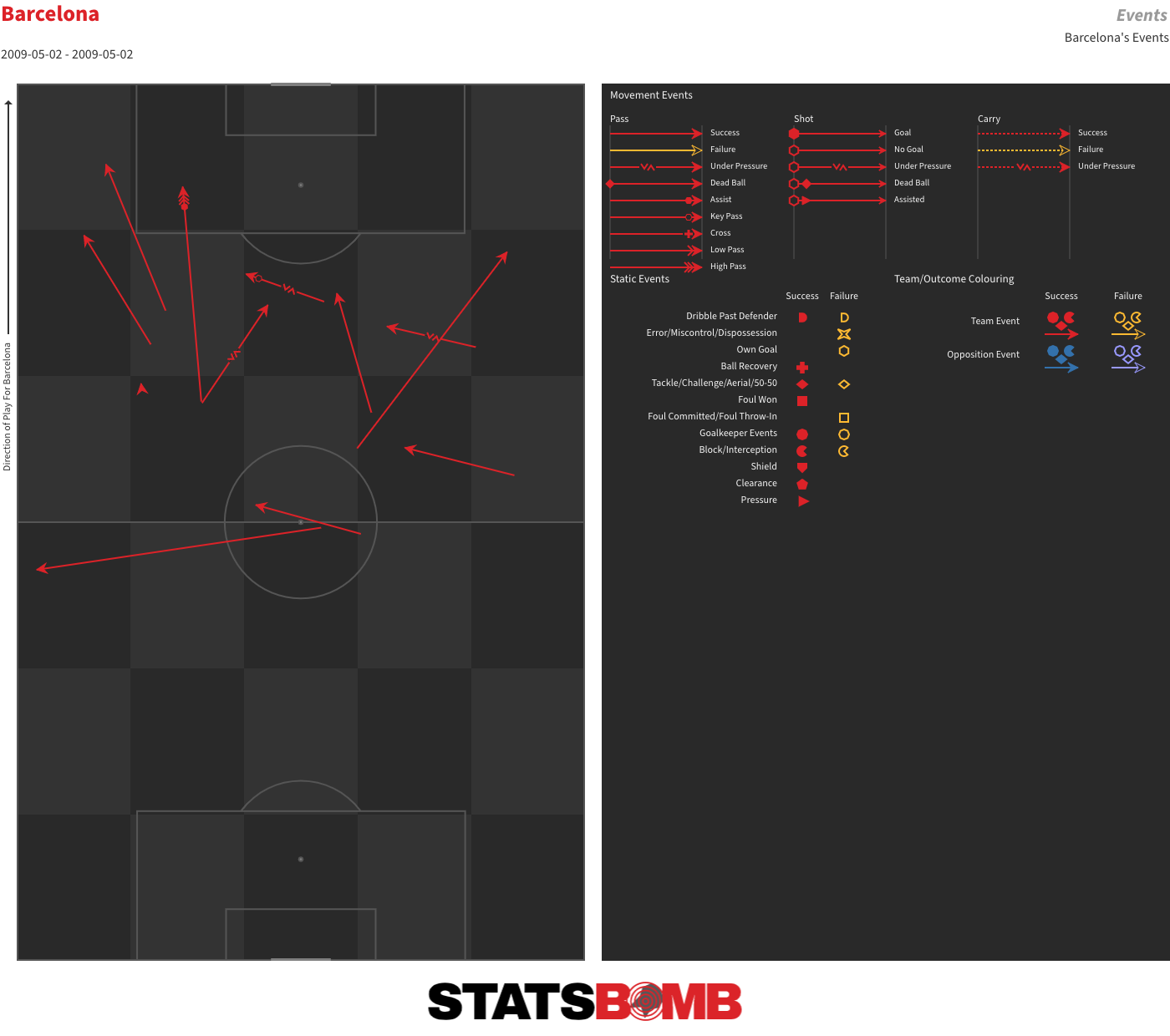

That created a problem for the Madrid defence, who couldn’t work out how to position themselves to defend Barcelona’s attacks. This map of passes from Messi to Henry and Eto’o shows this game plan in action. He played 12 passes to the pair of them: six of those were into space, four went diagonally forward and only one went backwards.

ND: Messi started the match in his normal position at that time as a wide forward on the right. But seven minutes in...

...he switched positions with Eto’o to move into the centre. A couple of minutes later, we see the first incisive move with Messi participating in central areas. Shortly thereafter, he provides the assist for the first Barcelona goal with a nice clipped pass to Henry. In addition to his connection with the two wide forwards, it is the relationship between between Messi and Xavi and Iniesta that allows this system to function at such a high level. When the three of them combined, and they did so often, Madrid just couldn’t get the ball off them. Many of Barcelona’s most dangerous attacks arose from combination play between them.

It seemed to me that there was a little bit of naivety in the way Madrid approached this match. This season, only three teams defended higher up against Barça than Madrid did in this match (José Luis Mendilibar’s Valladolid did so both home and away) and all of them attempted to break up Barça’s passing chains more frequently than Madrid did. There was insufficient pressure on the ball in midfield and a lot of space in behind their defence. With that said, what could any opposing team do when Barça positioned Xavi, Iniesta and Messi in close quarters? If you sat off them, you gave Xavi and Iniesta time and space to pick out incisive passes to the wide forwards or the full-backs; if you engaged them, they would just work the ball around to advance dangerously through the centre.

AD: That is why it was so difficult to deal with them. The best way to do so would be to prevent the ball getting to them. There are two ways of doing that. The first is to press very well high up the pitch and stop the team from moving the ball through the centre. Force them to go long. The other is to have numerical superiority in the centre of the pitch so that there is always pressure on the ball and you still have help on hand. Obviously, if any of those players receive the ball with time and space to pick their pass... Maybe the best approach is to drop back and defend your area. But even then, talent like that normally finds a way of creating chances.

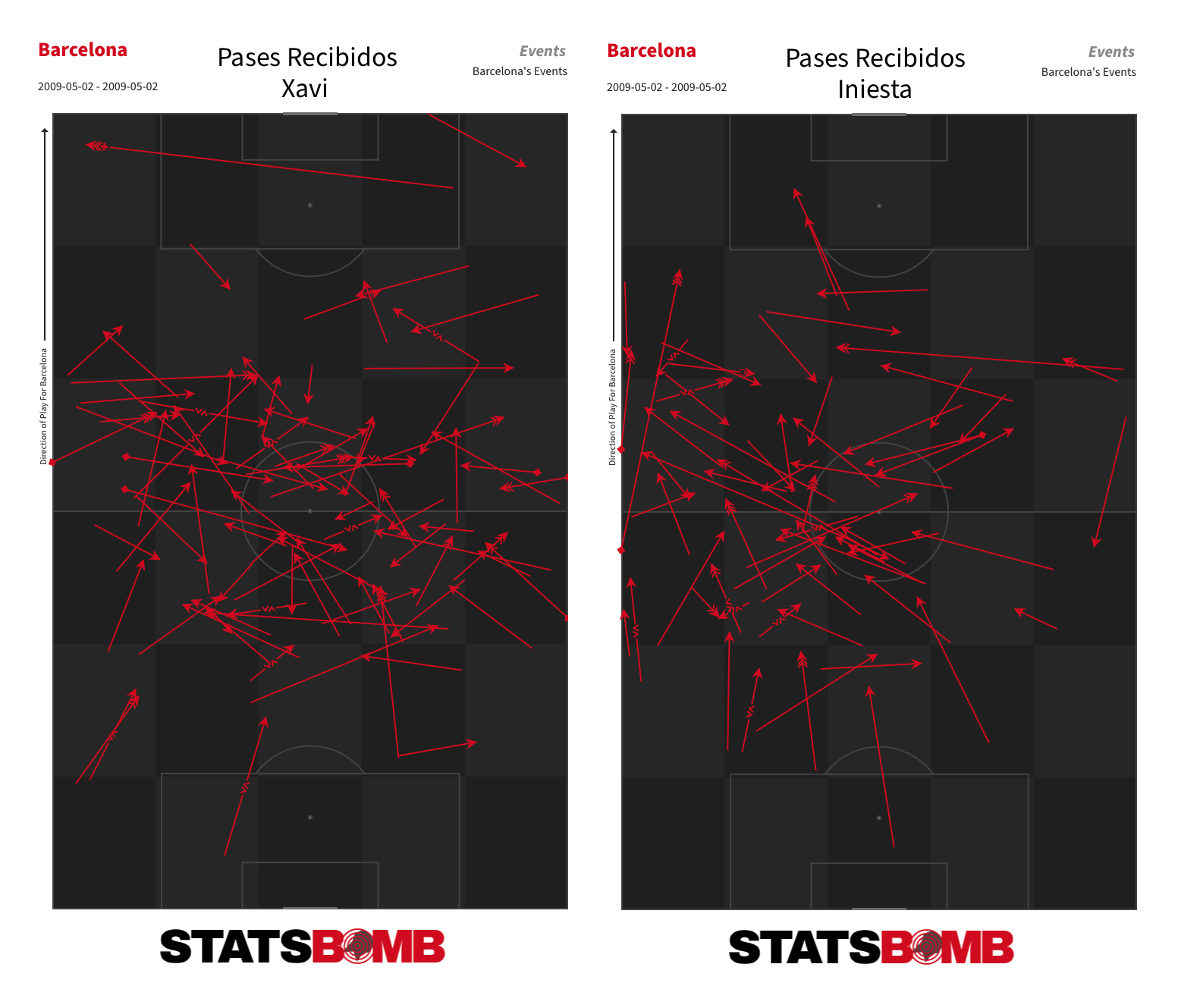

ND: It is also worth mentioning the varied movements of Xavi and Iniesta. Sometimes it is Xavi who positions himself between the lines and Iniesta who drops back to receive in deeper areas. Normally, it is Xavi on the right and Iniesta on the left, but sometimes they switch.

Was this variety of movement a regular thing in Guardiola’s Barcelona?

AD: It was a regular thing because one of the basic objectives of Guardiola’s Barcelona was to constantly create passing lanes. And passing lanes are created with constant movement. Saying that, while it is true that you can find moments in which one of them is ahead of the other, the general rule was that Xavi was the one who dropped back to receive the ball, while Iniesta positioned himself higher up. Xavi was better at initiating and creating play. Although Iniesta also had the ability to create without losing the ball, one of his best qualities was his ability to break lines off the dribble, something that was more decisive in the attacking zone.

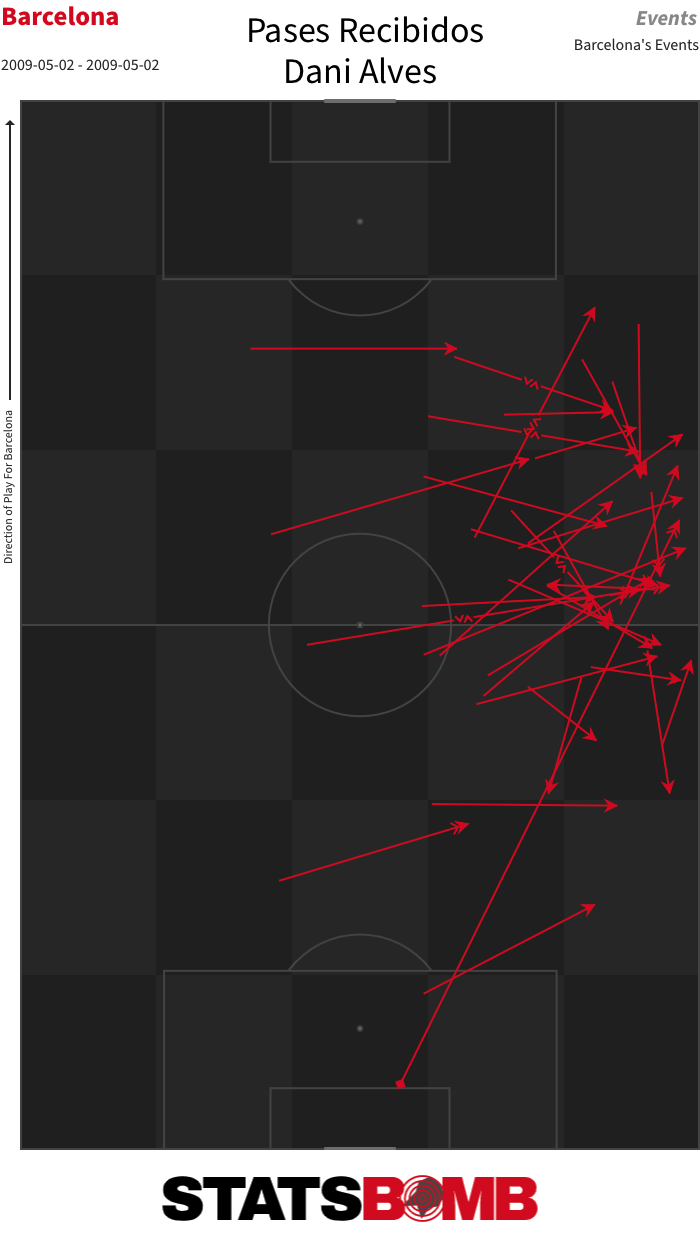

ND: Do you want to talk about the role of Dani Alves in this match? At this time, we were used to seeing him flying forward down the right to provide width as Messi moved infield. He appears in a relatively high and wide position in the majority of Barcelona’s pass maps for this season. But he has a more varied role in this match.

AD: Yes. Alves interpreted very well when and where to appear. He moved wide to spread the pitch when necessary but he also tucked in at times to provide a passing lane.

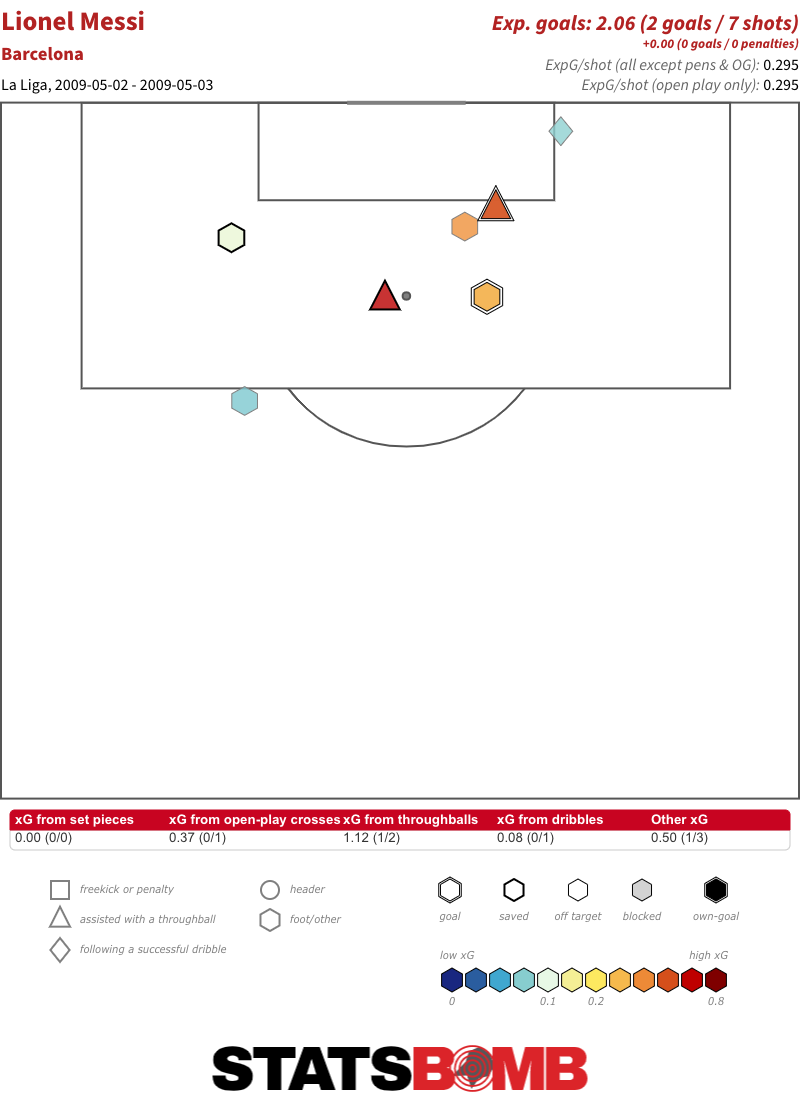

ND: Messi dominated this match. Two goals and an assist. Seven shots and three key passes, with the majority of those shots coming from central positions inside the area.

In that sense, this match functioned as a preview of the exceptional goalscorer that Messi would become in the years that followed. After 20 non-penalty goals this season, he scored 33 in 2009-10, 27 in 2010-11 and then 40 in 2011-12.

Even before this match, Messi was starting to appear in central areas with greater frequency than in the previous campaigns.

This was the first season in his career in which he averaged over a goal or assist per 90 minutes. Was a move to a more central starting position the next natural step in his development?

AD: Without a doubt. His development as a footballer was gradually pushing him towards a central position. He was becoming increasingly important to the team and showing his true self. In youth football, he was used to playing as an attacking midfielder with freedom of movement, so this was the natural evolution of that. Even still, this day changed his footballing life. Before this match, he had always had a positional responsibility related to his position on the right flank. From this day on, all of the team’s movements were centred around him. He was given total freedom. That resulted in a very evident increase in his influence over matches.

ND: During this period of Messi’s career, with Guardiola as his coach, there seemed to be a perfect balance between his almost limitless ability and the collective functioning of the team. The best player in the world playing in the world’s best team at the time. There was a synergy there that didn’t exist previously, and as we will see in the third and final part of this series, that doesn’t exist in the present day.

AD: I think this match is one that should form part of football history. I think that with time people will attach even more importance to it. It marks the point when the best footballer in the world was sublimated into a team who had completely sublimated the concepts of positional play. This match acts as a perfect manual in terms of how to form a game plan and carry it out in function of the response of your opponent. The focus is on two opposing concepts: combination play between the lines with the numerical superiority provided by Messi, and the threat in behind provided by the wide forwards. Barcelona chose one or the other in accordance with the actions of Madrid’s players. More often than not, the most productive one.