Pressure does funny things to people.

It can make or break matches, or careers, and manifests in different ways to different people. Sometimes it’s tell-tale, a placing, and re-placing, and re-placing, and re-placing of a ball on a penalty spot. You don’t even need to see missed spot-kick, much less the row of the crowd it lands in, to know the pressure that had been wracking the taker’s body.

Football teams, an ecosystem of individuals with their own triggers and quirks, are just as susceptible. Curiously, some of the most susceptible teams at the World Cup might still be in the competition.

Part of StatsBomb’s data is collecting when a player pressures their opponent (and, of course, when a player is under pressure). Being put under pressure can force poor passes, miscontrols, or being dispossessed, and nowhere is it more dangerous to lose possession in this way than in your own half.

There are some teams who stay cool in this current French heatwave: the United States have been the second-safest team under pressure in their own half in the tournament. They've only given up the ball in 12% of the times they’ve been pressured here, behind only Japan, who were narrowly dispatched by the Netherlands.

While most of the 16 teams who reached the knock-out rounds were the most pressure-resistant in the tournament, this isn’t always the case. In fact, Germany, who'll face Sweden on Saturday, have one of the worst rates of all 24 teams who were in France this summer, with the stereotypically efficient nation giving away possession 26.2% of the time when they’ve been pressured in their own half.

That quarter-final could be one to make a point of watching, because the Swedes are also the wrong side of the tournament average. The United States will be cheered by the fact that their opponents in the quarter-final-that-deserves-to-be-the-final, France, are also vulnerable to pressure. They fluff their lines a worse-than-average 19% of the time that they're pressured in their own half.

Should we expect to see an all out press from the US, then? Americans of a more nervy disposition might fear that France – who undeniably have a strong attack, bolstered even further by a home crowd as partisan to their own team as they’ve been fierce boo-ers of teams they take against – will tear them apart if an American high press is tried and failed.

This fear might be justified, but France’s attackers are a collection of the most prone to miscontrolling the ball. Valérie Gauvin has fumbled the ball on nearly 17% of the times she’s received it, the worst rate in the tournament of players who’ve been given the ball 20 times or more. And, in Kadidiatou Diani and Delphine Cascarino, Les Bleues have two more of the bottom five, both making miscontrols 11% of the time they receive the ball.

Perhaps this is a symptom of gaining the ball high up the pitch more often than other players in the tournament – the United States’ Rose Lavelle and Tobin Heath also have relatively poor rates for this – but the combination of French jitteriness under pressure in their own half and inconsistent control of several forwards is a combination that perhaps merit a roll of the dice.

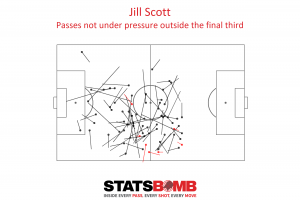

They might think differently if they were coming up against England’s Jill Scott, however. When she’s not under pressure, Scott – a tall and tireless box-to-box midfielder – has fairly conservative passing tastes outside of the final third.

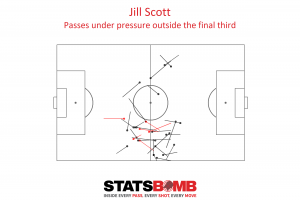

Just 12% of these passes are aimed towards goal, which is a large part of why they have a completion rate of 89%. Safe, but unexciting. But Scott comes alive when people apply pressure to her, the proportion of passes aimed towards goal shooting right up to 44%.

At 6’1”, towering over most players on the pitch, Scott’s more than able enough to hold off much of the pressure she’s put under, roll it, and turn to go on the attack. She might be one of the few players that it’s worth taking it a little easier with rather than getting in her face.

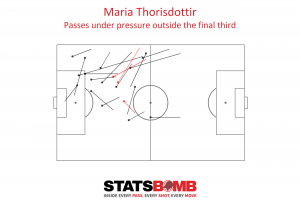

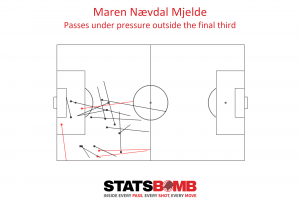

If that’s the advice for Norway, then their quarter-final opponents England can get some in the pass maps of the two Norwegian centre-backs when they’re under pressure.

English players should know Maren Mjelde and Maria Thorisdottir fairly well given that both have been at Chelsea for the past few years. At the World Cup, Thorisdottir generally goes to the left-back:

While Mjelde seems to be more of a fan of a more vertical ball towards goal.

If she goes square, the plan could be to keep Thorisdottir on her left foot and pressure her into a quick pass out to the left-back, and have a player ready to pounce on them. If Mjelde doesn’t look square, England’s midfield should be creeping up and ready to nick the ball away from Norway’s deeper midfielders.

This is the point at which pressure will start to tell. The round of 16 tested some teams who, quite frankly, needed it (looking at you, United States), but with the final now just ten days away it all starts to feel more real.

A win here, and you’re in the semi-final; a mistake, and you might not be. How the teams, and their ecosystems of players, react to this will be both telling and vitally important.