Apparently it’s “finishing skill” season. The debate happens every year, more or less, usually precipitated by an incredible run of goals by somebody or other.

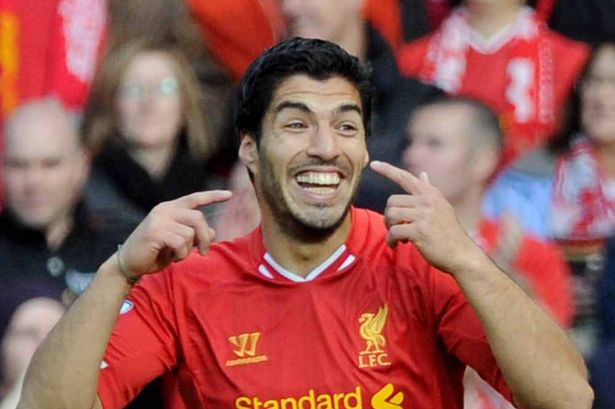

This year, obviously it’s Luis Suarez who has spurred the discussion (including some particularly long and heated ones between me and @SimonGleave…sorry everybody).

In general the debate boils down to three specific questions: What is finishing skill? Does it exist at all? Even if it does exist, does it matter? So, let’s wade into the murk shall we.

Defining the terms of this discussion is actually a pretty tricky enterprise. Arguments generally start over a player’s conversion percentage, or goals vs. expected goals ratio, and devolve fairly quickly, often times into people talking at cross purposes.

So, let’s look at two possible definitions on opposite sides of the spectrum. What if we defined “finishing ability” as the simplest most basic moment of ball hitting foot and ball flying into the net (or into row z).

If we define it that way, it means we are controlling for absolutely everything else on the football field. When we deal in expected goals, we’ve already started this process, since that involves controlling for shot location, shot type, probably pass type, and some other things depending on the model (an important note, the vast majority of a shot’s chances of going in the net are due to its distance from the net, everything else that we’re talking about here is much much less important when it comes to impacting a shot’s chance of succeeding. I’ll come back to this point later).

We can go beyond that though, at least in this theoretical world I’m operating in. We could control for dominant foot, we could control for what part of the foot the shot was taken with, we could control for whether the player was on or off balance, the speed with which the ball was moving when struck, the speed with which the player was moving when he struck the ball, etc. etc. You guys can all come up with your own examples. So, controlling for all of those other factors leaves us with a narrow definition of finishing skill. That’s fine, and given that definition it makes sense that perhaps there would be little to no difference between players, especially between players playing the forward position at an elite level. But now let’s go back to the initial question.

If a player is shooting well above, or below average levels after accounting for shot location can we simply say it’s down to natural variation because players all have the same finishing skill? There’s a little bit of a problem here because we have a whole set of skills which we both aren’t including in our definition of “finishing skills” but which also aren’t accounted for by any models which we’re using. So, by asserting that it’s simple variation because players all have the same finishing skill, we’re either asserting that those skills don’t impact shooting results at all, or we’re asserting that their impact on shooting outcomes is dwarfed by the random variation that arises from the very act of kicking. Is that true? I don’t know.

But I do know that the more narrowly we define finishing skill the harder the argument is to make that the fact that it’s constant (if it is) among players is the reason for variance in performance. I’m just simply not comfortable writing off a whole set of variables we know nothing about and assuming they are unimportant to outcomes without proof.

Okay, but what if we defined “finishing skill” more broadly. Instead of trying to zero down to that exact moment of foot to ball, what if we just loosely defined finishing skill as, “the ability to score more goals than an expected goal model would predict.”

Well for starters, thanks to @MCofA we do have some evidence that in very very large samples some players can outperform expected goals. So, it’s there, but it’s very very hard to do and equally hard to spot.

But, just like with the narrower definition, it’s worth saying explicitly what this means. What we’re saying is that taking into account all of these, let’s call them sub-skills, that go into finishing and players still more or less show no ability to improve. Why is that? Well, one possibility is that all of these sub-skills are as random as narrowly defined finishing skill.

Saying that though, is basically saying that every attacking player is exactly the same and differences are due solely to randomness.

Subjectively I’m not comfortable with the implications of that argument, since it would mean things like Arjen Robben’s left foot is as good as as Cristiano Ronaldo’s or Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Olivier Giroud both hit the ball with the same velocity, and differences are solely down to randomness. Again, it’s a defensible position because we don’t have the data that conclusively proves these differences yet, but it’s not territory I’d be willing to stake out.

Rather, I’d say, these sub-skills vary greatly in terms of both a player’s ability to control them, and their ultimate importance in finishing. Some things will be well within a player’s control and some will largely vary due to luck. And then on top of that a player’s decision making layers in the frequency with which various skills come into play (how often does player X shoot with his weak foot, as opposed to how good is that weak foot when he shoots).

Put all that together and you have an equation with so many variables that it’s next to impossible to be good enough at enough stuff to actually move the finishing needle. This isn’t exactly news. It’s just another way of saying, finishing involves a diverse skill set, is really hard and has lots of luck involved. Pretty much the same as it ever was. All of which is fine and good, but leaves the third question unanswered.

Does any of this matter? At best, finishing skill when we define it loosely is really difficult to spot, and we can’t see it in players season to season, so it doesn’t really matter much for scouting, so why bother writing this many words about it at all? I mean who cares if Johnny Soccerboy only scores farpost curlers with his weaker foot at 4% and Clive Footielad does it at 14%. Remember, shot conversion overwhelmingly depends on location, this stuff is exceedingly small potatoes by comparison. It doesn’t impact things enough to make a difference.

Working with our two definitions of finishing skill we can look at it this way. Define it narrowly and we can ignore it. Players may have uniform skill, but that skill is fairly minor when it comes to examining all the things that go into shooting (this is a point I’d certainly be willing to change my mind on if data proved otherwise) or it encompasses lots of factors. In that case, when we define finishing skill as an amalgamation of all of these factors, we can see differences. Those differences, however, lie in how players finish, not in how often.

That’s important, because it allows us to understand that the way players shoot can differ, even if the end conversion percentage doesn’t much. It gives us a number of options for further examining football, shooting, and team construction. Perhaps the most severe limitation right now is that the differences in the level of finishing, even when accounting for location, are so small compared to the number of shots players take in a season that it is impossible to differentiate between a player who might finish at 13% (location adjusted) and one who finishes at 17%.

There’s not disagreement on which player you want on your team, just that it’s impossible to look through all the variance to definitively find those players. But, what if instead of looking at players we could look at various skill-sets and see if they reliably over large samples provided better adjusted finishing rates. A cross sport example to make my point: a defensive specialist in basketball is often times a detriment to have on the court, but a defensive specialist who can also shoot a three-point shot from the corner is worth his weight in gold. Skill combinations.

Examining which possible combinations are reliably above average and then either recruiting to them, or developing players in them is a possible way to envision teams getting beyond the sample size barrier. From an analytics standpoint not dismissing finishing skill is hugely important. That’s because the ways in which a player shoots, what he may or may not be good at, how he decides to balance his varying shooting options partially define the set of shots he takes.

And when we talk about defining the set of shots a player takes, we are now moving beyond the realm of goals, and to the realm of expected goals. It’s easy to see how on one side of the coin shot selection defines conversion percentages, and so counts as part of what we consider finishing skills, but it also plays a huge part in establishing expected goals. Obviously a shot not taken has no ExpG value, and equally obviously what shots a player takes are defined by a number of factors, all of which could also be filed under finishing skill. I vehemently believe that understanding the specifics of how and when players shoot is important.

Given how complicated a sport football is, and how rare goal scoring events are in general, we’d never know decisively just by looking at outputs if players managed to increase their conversion percentages, or even teams for that matter. That doesn’t mean that those margins aren’t important, and it certainly doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. It simply means that to find them we may need to start systematically looking at inputs instead.

And it’s those inputs which make up finishing skill. It seems like to insist on finishing being completely luck you have to take one of two stances.

One define it so narrowly that you then leave yourself lots of work to do to prove that variance from finishing skill impacts statistics at all (as opposed to variance from other factors relating to shooting), or if you define it more broadly, insist that differences between player shooting events, both how often they score, and the specifics of the shots they take, are a result of pure variance, an insistence that both shot result and shot type are due to variance. There’s so much we don’t know about the sport. It seems a shame to dismiss a whole area of study, just because it isn’t clearly reflected in the data we currently track. Who knows what we might find.