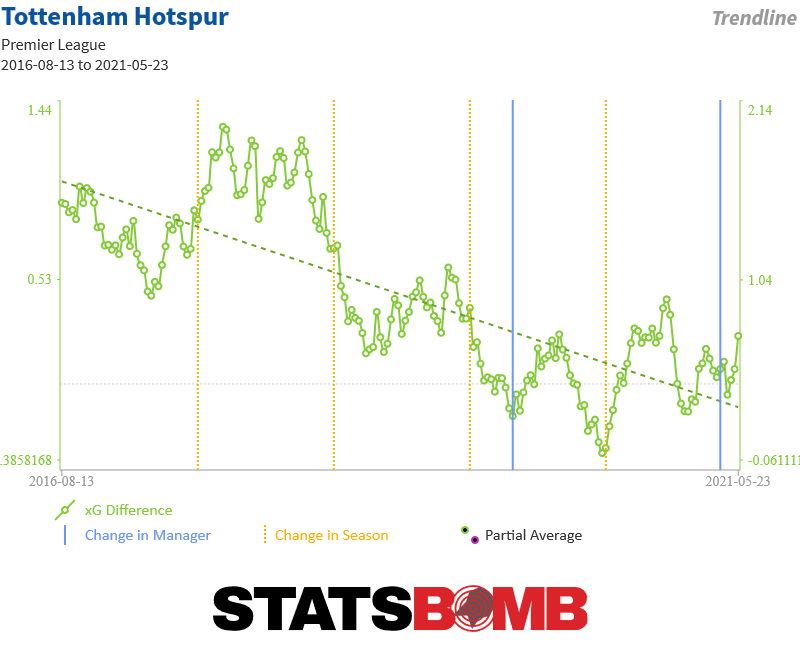

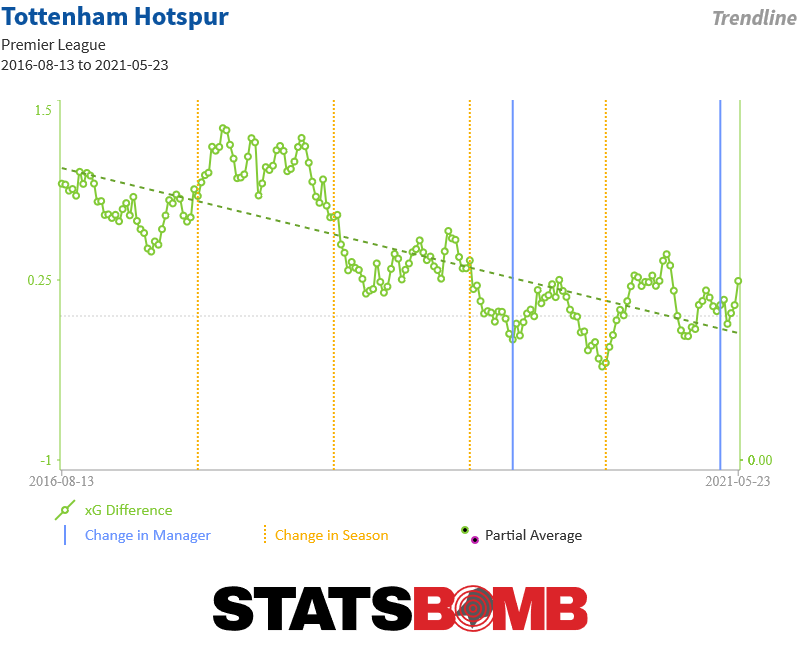

It was as shocking as it was decisive. Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy told Mauricio Pochettino to take his energía universal back to Argentina. In its place came an entirely different kind of energy, a unique electricity that surrounds José Mourinho. The change is indisputably a masterstroke, if the club's only concerns are drama and narrative. It certainly will bring about quite a culture shift in North London. But will it work to help Tottenham’s stated aim of winning more football matches? The most obvious thing to note is that Mourinho is not inheriting a side playing particularly well. Everyone is aware of this, but the problems at Spurs have persisted for longer than most realise. When looking at the expected goals trendlines, what’s obvious is that the side stopped being able to dominate in terms of creating and preventing good chances around April 2018. Pochettino’s side were able to outrun the xG for the best part of a year, but the results caught up with the numbers eventually.  Another oft-noted factor is that Spurs aren’t able to press in the same way they once did, which is again visible in the numbers over a long period. The number of passes they allowed the opposition to make before attempting to win the ball back has gradually increased over this same period. They are no longer a pressing machine.

Another oft-noted factor is that Spurs aren’t able to press in the same way they once did, which is again visible in the numbers over a long period. The number of passes they allowed the opposition to make before attempting to win the ball back has gradually increased over this same period. They are no longer a pressing machine.  It feels unlikely this was a conscious choice Pochettino made, but that might be irrelevant now. The question is whether Mourinho sticks with this or turns a big dial that says “pressing” on it and looks back to the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium crowd for approval. The assumption from a basic reading of his career would be that he will not have this team press high, though he would argue this is unfair. He certainly perceives his own career as one in which he adapts his style to the talent available:

It feels unlikely this was a conscious choice Pochettino made, but that might be irrelevant now. The question is whether Mourinho sticks with this or turns a big dial that says “pressing” on it and looks back to the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium crowd for approval. The assumption from a basic reading of his career would be that he will not have this team press high, though he would argue this is unfair. He certainly perceives his own career as one in which he adapts his style to the talent available:

“You can compare my Porto team with Liverpool because the qualities of the players are there. It was my best team in defensive transition. We lose the ball, we bite like mad dogs and recover the ball after two seconds. In Real Madrid, I had my best team in direct counter attack because I had young [Ángel] Di María, young [Cristiano] Ronaldo, young [Gonzalo] Higuaín and young [Karim] Benzema. We killed everybody in offensive transitions. In Inter, I had my best team in a defensive low block. [With] people like [Marco] Materazzi, [Walter] Samuel, Lúcio, [Iván] Córdoba in the low block you can be there five hours and you don’t concede a goal. So players make teams play in certain ways.”

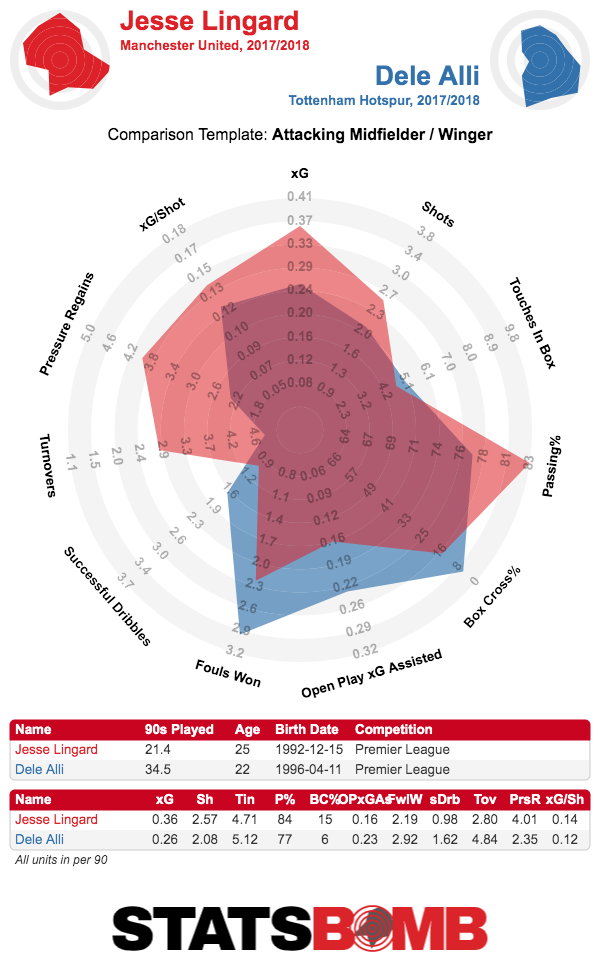

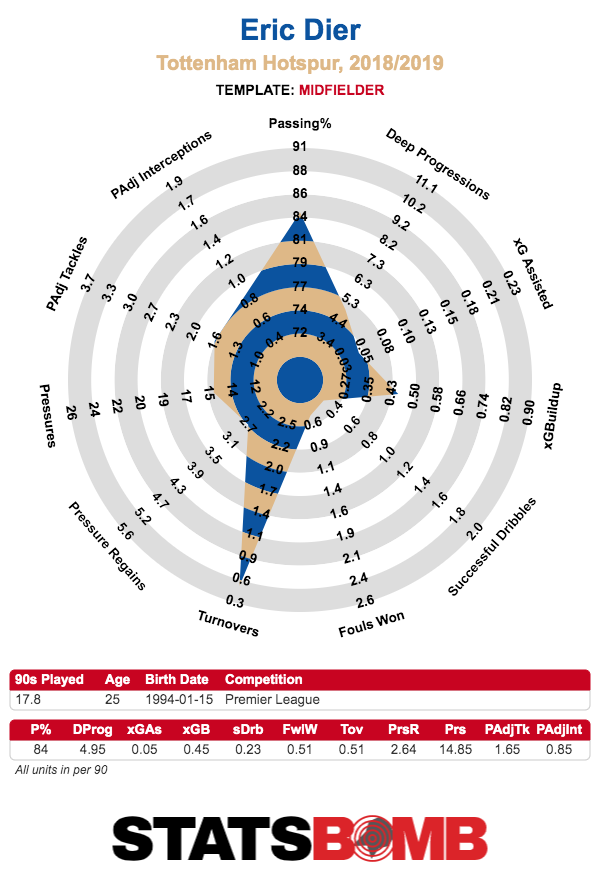

If we take Mourinho at his word, how will he adapt to these players? The intrigue begins with the centre backs. There are few doubts about the quality of Toby Alderweireld and Jan Vertonghen; the pair have been the best central defensive partnership in the Premier League in the last five years. What they are not are “low block” defenders of the type Mourinho had at Inter. With the odds of at least one of these two leaving in the summer, the new manager could conceivably reshape his defence around a centre back more adept at clearing the ball away in his own box, but for now, he must work with defenders accustomed to taking a higher line. Davinson Sánchez and Juan Foyth, the other options, are broadly of the same mould. This might mean we see a side closer to Porto than Inter, where Mourinho has the players available to play higher up the pitch. He generally likes to employ an aggressive pressing number ten; Dele Alli is natural fit. The Englishman led Spurs in pressures per 90 for the previous two seasons, while providing exactly the kind of dynamic runs into the box and ability to get goals that Mourinho wants in a number ten. Despite the number of problems that occurred during his time at Manchester United, Mourinho was able to really get the best out of Jesse Lingard, a player with a similar skillset but lesser ability than Alli. There is no reason to think this combination of player and manager won’t thrive.  Of the two games Tottenham have played under Mourinho, there have been few surprises. Harry Kane is unsurprisingly leading the line, and appears to be taking up positions on the shoulder of the defence more frequently. He has been caught offside a few times, but this might be a case of adapting to a slightly different role and learning to time his runs better. He opened the Mourinho era with three goals from four open play shots in two games, which I don’t need to tell you is not going to be sustainable. Enough has been written on Kane’s declining shot volume of the later Pochettino era, and it will take a larger sample before we can reassess him under Mourinho. Mourinho has always valued speed, so it’s unsurprising that Lucas Moura has these games on the right. The manager has a penchant for converting previously flakey wide players into disciplined workhorses, so presumably he will attempt to turn Lucas into this team’s Willian. Erik Lamela might be a more natural fit here defensively, he doesn’t have quite the same burst of pace as Lucas and seems less suited to direct counter attacking than Pochettino’s press and possess approach. On the other side, while at Chelsea and Real Madrid, Mourinho preferred his left-sided attacker to push up high, and Son Heung-min should have no issue fulfilling this duty. He doesn’t have the same majestic creativity and dribbling skills as Eden Hazard, but if you wanted a budget version of circa 2012 Ronaldo, Son is a good fit. The midfield is somewhat less inspiring. Eric Dier and Harry Winks appear to be the preferred double pivot for the time being, which creates limitations. Winks is undoubtedly a calm passer in the mould of Michael Carrick or Gareth Barry, but he primarily passes to the player who really progresses the ball, not the ball progressor himself. This is all well and good, but less so when playing next to Dier who, to put it politely, has a few weaknesses. There is hope that Mourinho might shake the once-useful Dier back into action, but considering his public acknowledgment that health issues have contributed to his poor form, this isn’t an easy problem to fix. His best form, it shouldn’t be forgotten, came when he played alongside Mousa Dembélé, who could control games through an inhuman ability to resist the press. Winks does not provide such skills.

Of the two games Tottenham have played under Mourinho, there have been few surprises. Harry Kane is unsurprisingly leading the line, and appears to be taking up positions on the shoulder of the defence more frequently. He has been caught offside a few times, but this might be a case of adapting to a slightly different role and learning to time his runs better. He opened the Mourinho era with three goals from four open play shots in two games, which I don’t need to tell you is not going to be sustainable. Enough has been written on Kane’s declining shot volume of the later Pochettino era, and it will take a larger sample before we can reassess him under Mourinho. Mourinho has always valued speed, so it’s unsurprising that Lucas Moura has these games on the right. The manager has a penchant for converting previously flakey wide players into disciplined workhorses, so presumably he will attempt to turn Lucas into this team’s Willian. Erik Lamela might be a more natural fit here defensively, he doesn’t have quite the same burst of pace as Lucas and seems less suited to direct counter attacking than Pochettino’s press and possess approach. On the other side, while at Chelsea and Real Madrid, Mourinho preferred his left-sided attacker to push up high, and Son Heung-min should have no issue fulfilling this duty. He doesn’t have the same majestic creativity and dribbling skills as Eden Hazard, but if you wanted a budget version of circa 2012 Ronaldo, Son is a good fit. The midfield is somewhat less inspiring. Eric Dier and Harry Winks appear to be the preferred double pivot for the time being, which creates limitations. Winks is undoubtedly a calm passer in the mould of Michael Carrick or Gareth Barry, but he primarily passes to the player who really progresses the ball, not the ball progressor himself. This is all well and good, but less so when playing next to Dier who, to put it politely, has a few weaknesses. There is hope that Mourinho might shake the once-useful Dier back into action, but considering his public acknowledgment that health issues have contributed to his poor form, this isn’t an easy problem to fix. His best form, it shouldn’t be forgotten, came when he played alongside Mousa Dembélé, who could control games through an inhuman ability to resist the press. Winks does not provide such skills.  Thus the lack of creative passing in what seems to be Mourinho’s first-choice side could be a real problem. Tanguy Ndombele, Giovani Lo Celso and Christian Eriksen could fit into this side but have thus far been confined to appearances off the bench. As Mourinho cares most about attacking through fast transitions, he might worry that these players could slow the tempo of the game he wants to play (though Ndombele would argue against this). There's a real concern that Mourinho’s side will not have a clear idea in possession and will be unable to create freely. You get what you get from Mourinho. A higher defensive line, a higher pressing version of the kind of fast counter attacking football he generally deploys. There will be games where he takes an extremely negative approach, but they won't be the norm. The team might have trouble breaking down sides in possession, a typical issue in primarily reactive football. With all of this, it should be expected that things improve in the short term at an absolute minimum. The big picture questions won’t become clear for another year.

Thus the lack of creative passing in what seems to be Mourinho’s first-choice side could be a real problem. Tanguy Ndombele, Giovani Lo Celso and Christian Eriksen could fit into this side but have thus far been confined to appearances off the bench. As Mourinho cares most about attacking through fast transitions, he might worry that these players could slow the tempo of the game he wants to play (though Ndombele would argue against this). There's a real concern that Mourinho’s side will not have a clear idea in possession and will be unable to create freely. You get what you get from Mourinho. A higher defensive line, a higher pressing version of the kind of fast counter attacking football he generally deploys. There will be games where he takes an extremely negative approach, but they won't be the norm. The team might have trouble breaking down sides in possession, a typical issue in primarily reactive football. With all of this, it should be expected that things improve in the short term at an absolute minimum. The big picture questions won’t become clear for another year.

Stats of Interest

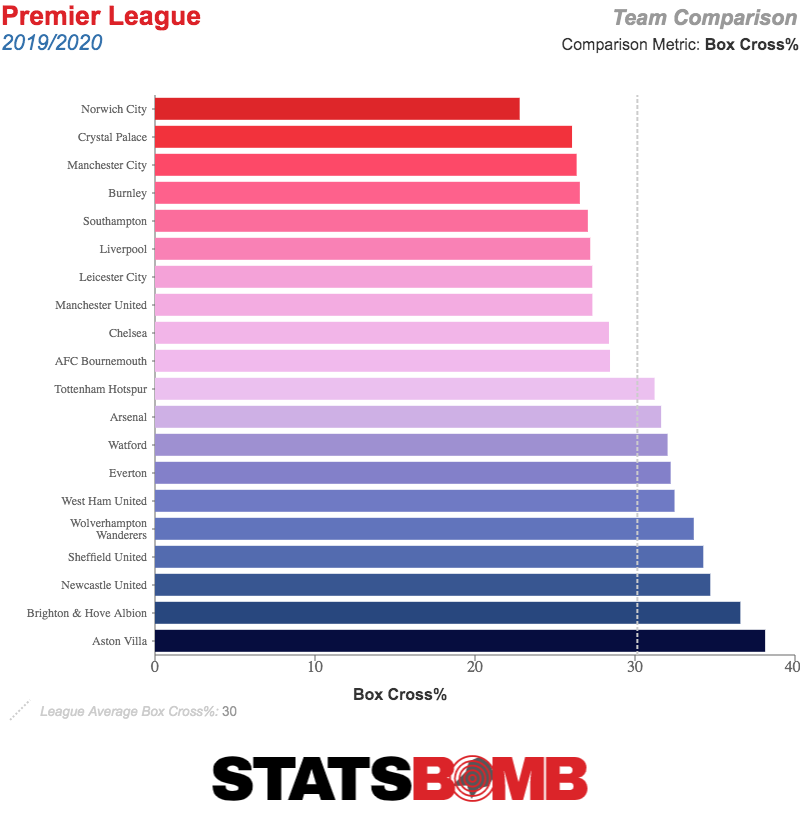

In Arsène Wenger's final season at the Emirates, 24% of Arsenal's passes into the box came from crosses, the lowest in the Premier League. In a stat that traditionally skews towards better sides (Pep Guardiola's Manchester City were a fraction behind), Arsenal came out top. This season, however, that figure is 32%. Not only is this a notable rise, but no other top-six team is relying on crosses to work the ball into the box as much as Unai Emery's. Arsenal just lack the imagination they once had in terms of moving the ball forward.  While some sides are embracing elaborate set-piece routines to find new edges, Chelsea isn't one of them. Frank Lampard's side have the lowest xG per set piece of any team in the league. Lampard admits that the Chelsea team he played in did not work on elaborate routines, believing just getting it into the area with players like Didier Drogba and John Terry was enough. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like that's enough now.

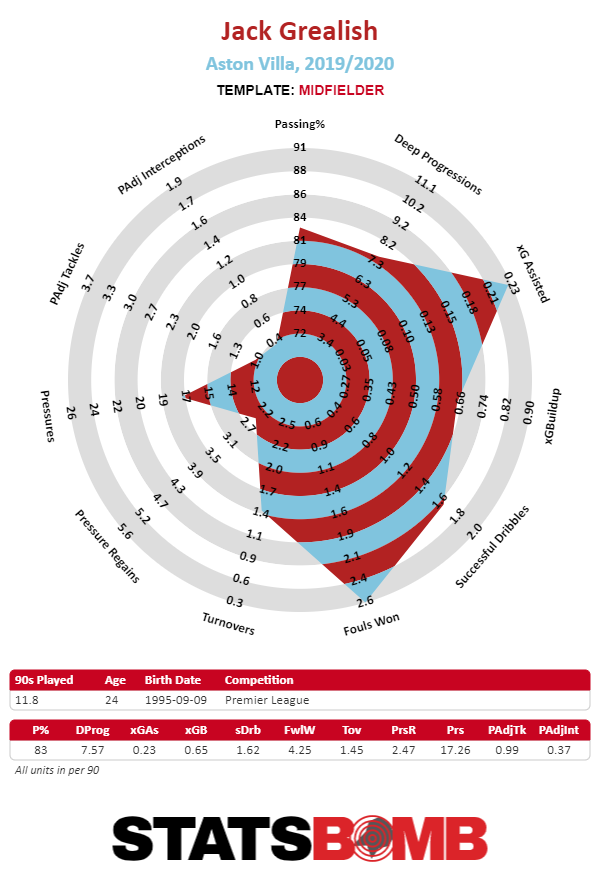

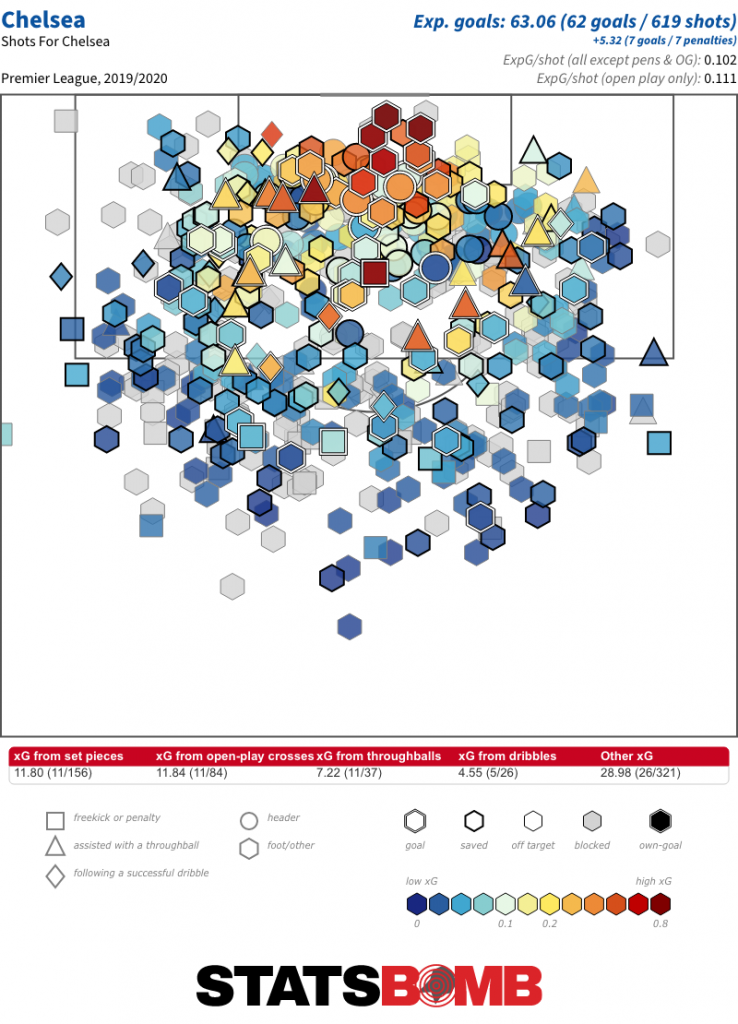

While some sides are embracing elaborate set-piece routines to find new edges, Chelsea isn't one of them. Frank Lampard's side have the lowest xG per set piece of any team in the league. Lampard admits that the Chelsea team he played in did not work on elaborate routines, believing just getting it into the area with players like Didier Drogba and John Terry was enough. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like that's enough now.  Jack Grealish is earning himself a fair bit of hype at the moment and the numbers indicate it's much deserved. Aston Villa's captain is completing the most open play passes into the box of any non-top-six player, while also winning more fouls than anyone else in the league. In Grealish, Villa have an excellent creator, whether he's playing on the left or in a central midfield role.

Jack Grealish is earning himself a fair bit of hype at the moment and the numbers indicate it's much deserved. Aston Villa's captain is completing the most open play passes into the box of any non-top-six player, while also winning more fouls than anyone else in the league. In Grealish, Villa have an excellent creator, whether he's playing on the left or in a central midfield role.