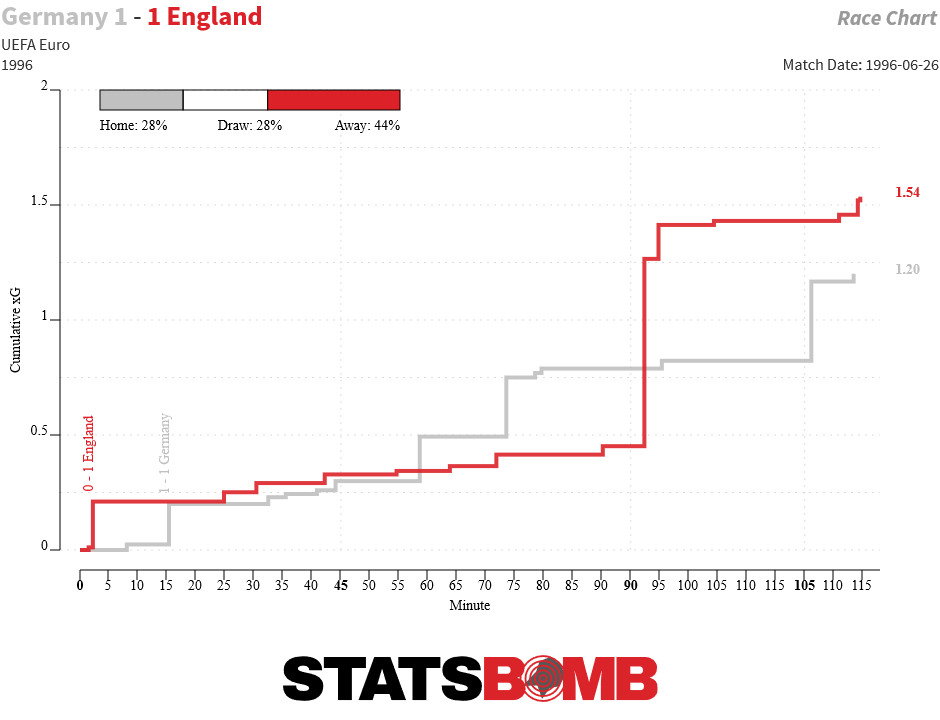

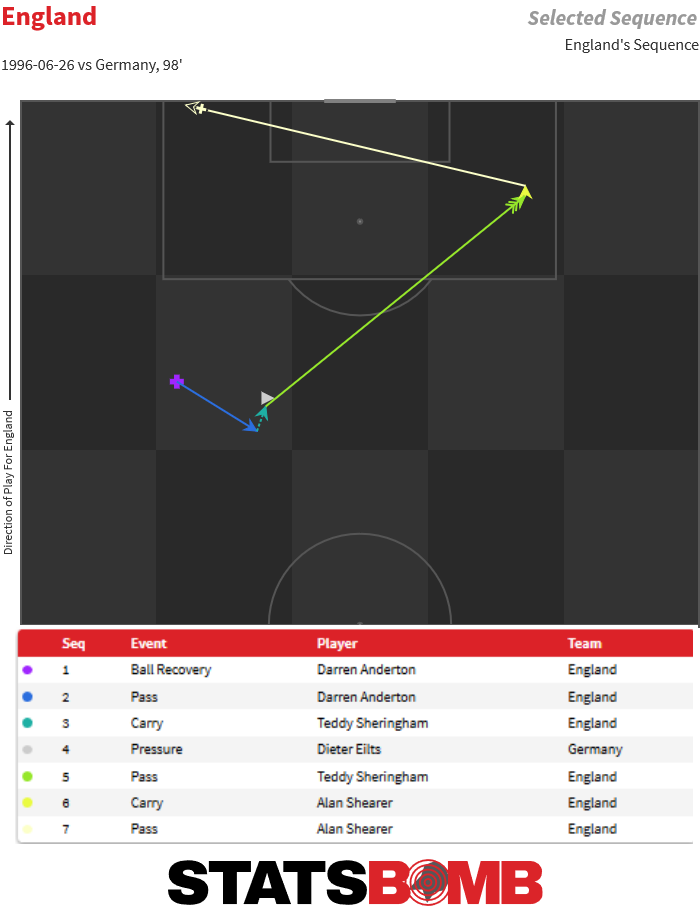

A penalty shoot out was required for England to get past Spain, and set-up a semi-final clash with old rivals Germany. ITV Sport continue to show these games and this is the fifth and final episode in our series, see parts one to four here: England 1 v 1 Switzerland England 2 v 0 Scotland England 4 v 1 Netherlands England 0 v 0 Spain So this was it. Germany again. Could England put away the memories of Turin in 1990 or were they to succumb once again to the relentless German appetite to win?  The game was as close as the final score suggested. Two early goals parked the sides at 1-1, a scoreline that persisted to the end of extra time. England had not one but two huge chances to win the game late on. Darren Anderton hit the post with the net gaping, as he tried to turn a ball that had trickily landed behind him, then famously Paul Gascoigne failed to connect with a cross that seemed easier to finish than not. No touch, no shot and therefore no mention in the sequence:

The game was as close as the final score suggested. Two early goals parked the sides at 1-1, a scoreline that persisted to the end of extra time. England had not one but two huge chances to win the game late on. Darren Anderton hit the post with the net gaping, as he tried to turn a ball that had trickily landed behind him, then famously Paul Gascoigne failed to connect with a cross that seemed easier to finish than not. No touch, no shot and therefore no mention in the sequence:

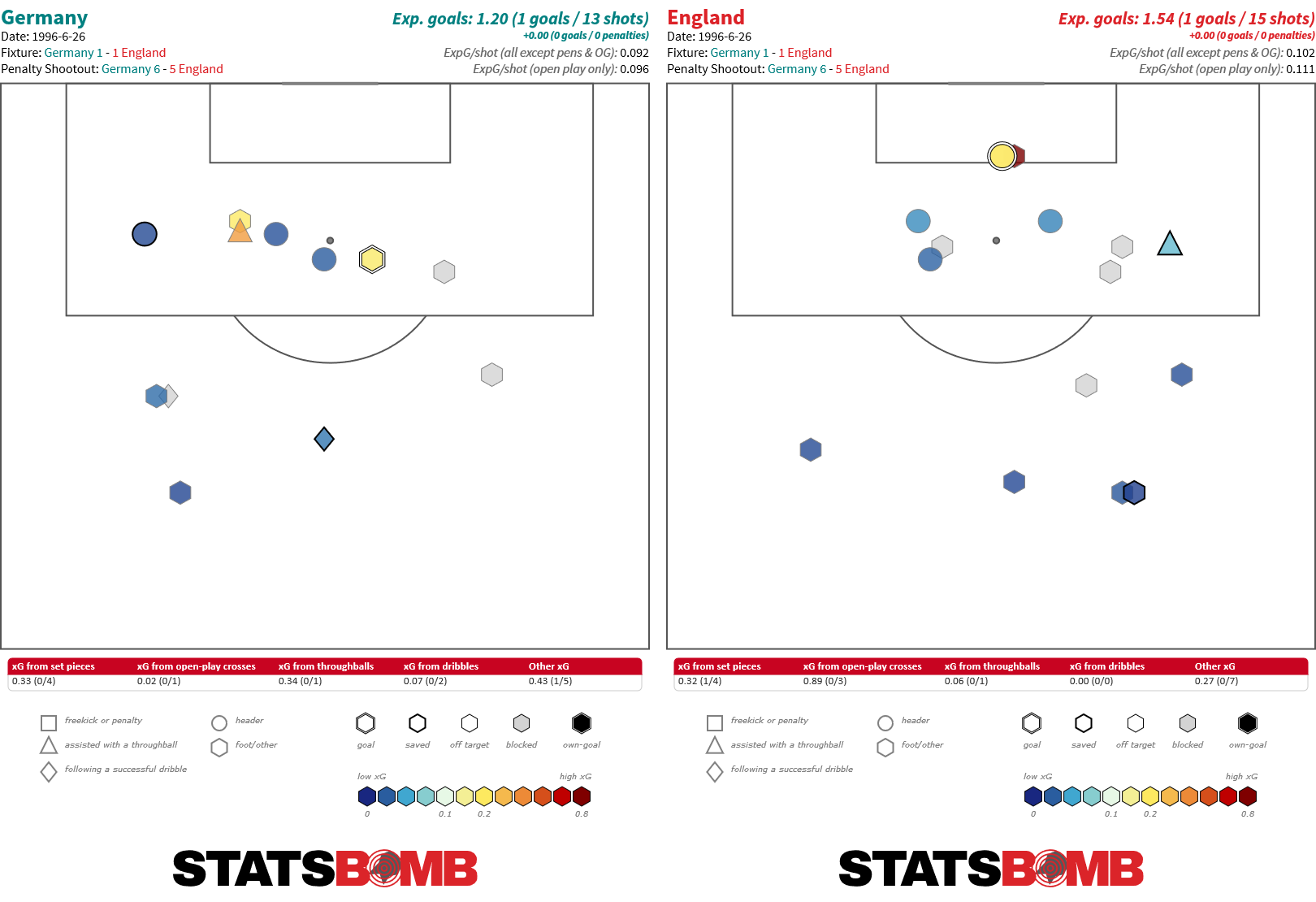

As we can see this was not a game of high quality chances. Apart from Anderton's miss, Alan Shearer's 3rd minute opener was the only shot significantly in advance of the penalty sport for either side. England once again tweaked their formation in this game, with three centre backs in a nominal 3-5-2 system, with wingers rather than traditional full backs placed in the wide slots:

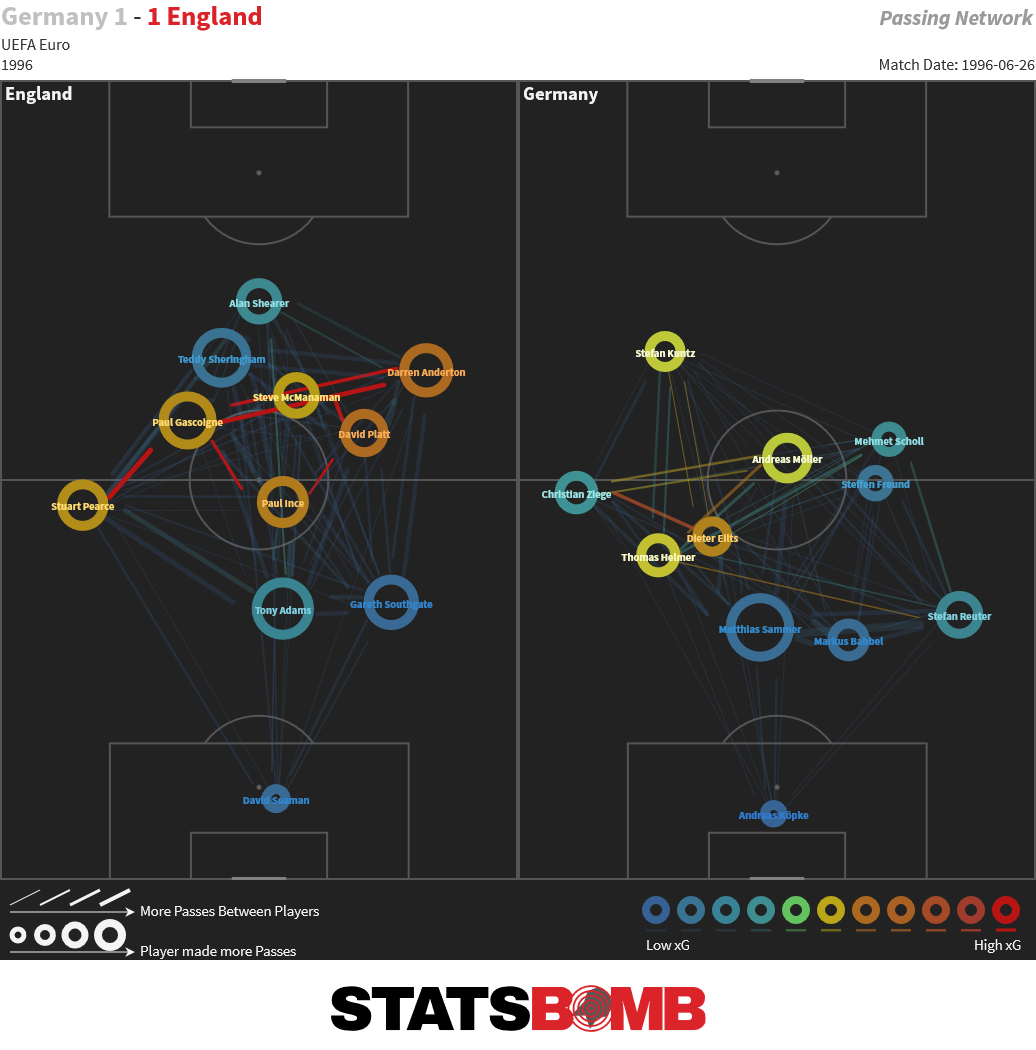

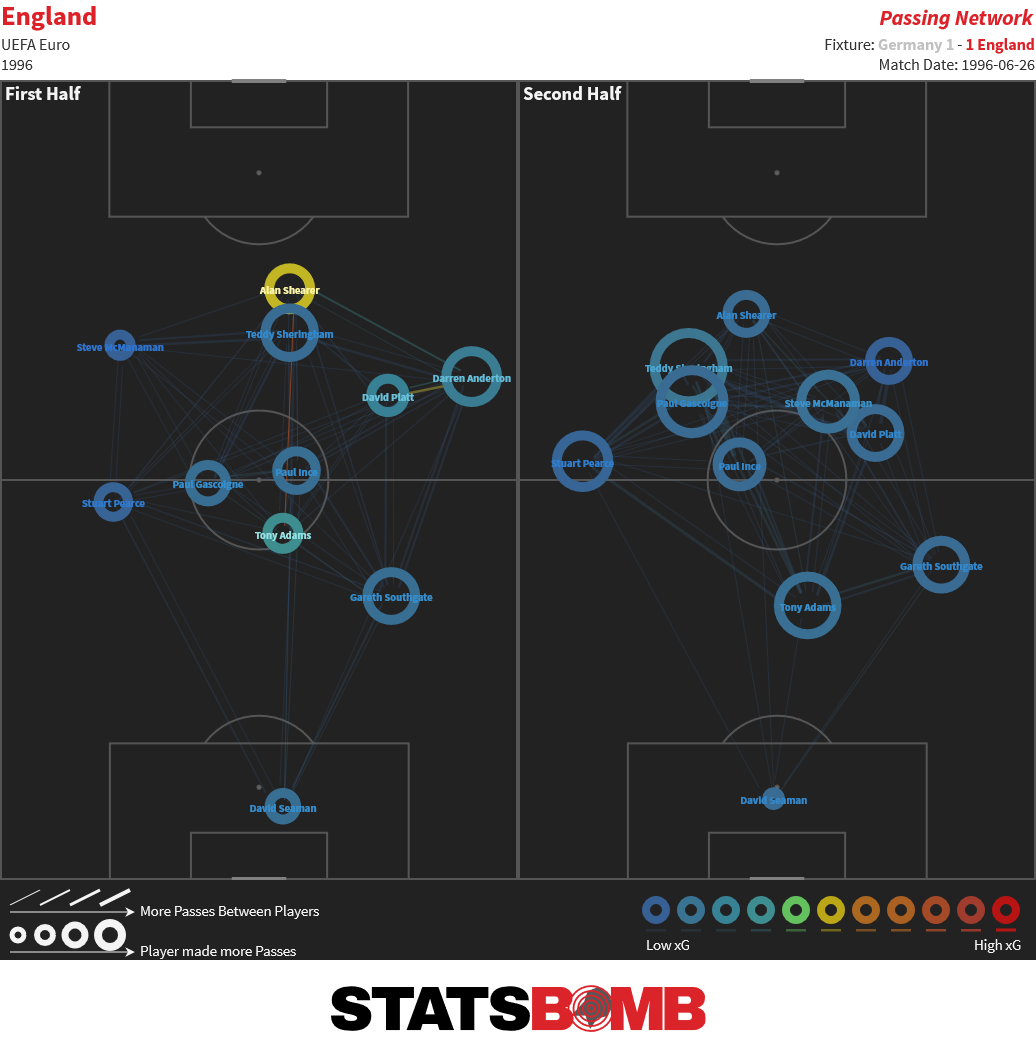

As we can see this was not a game of high quality chances. Apart from Anderton's miss, Alan Shearer's 3rd minute opener was the only shot significantly in advance of the penalty sport for either side. England once again tweaked their formation in this game, with three centre backs in a nominal 3-5-2 system, with wingers rather than traditional full backs placed in the wide slots:  Unusually England did not make a substitution during the whole game, which gives us a unique opportunity to compare the first and second half pass positions without the interruption of replacements:

Unusually England did not make a substitution during the whole game, which gives us a unique opportunity to compare the first and second half pass positions without the interruption of replacements:  Steve McManaman and Darren Anderton kept to their wings in the first half, but were far more flexible in the second half. Gascoigne too saw a change in role from half to half, as he moved forwards as the game went on. Territory wise, England had far the better of it. Six players attempted over twenty passes in Germany's final third, while no German player attempted more than fifteen at the opposite end. David Platt in particular was neat and tidy with 94% passing, while unusually for a forward, Teddy Sheringham got through the most volume; 75 passes in total. In the end though, they couldn't make it pay and the game went to penalties.

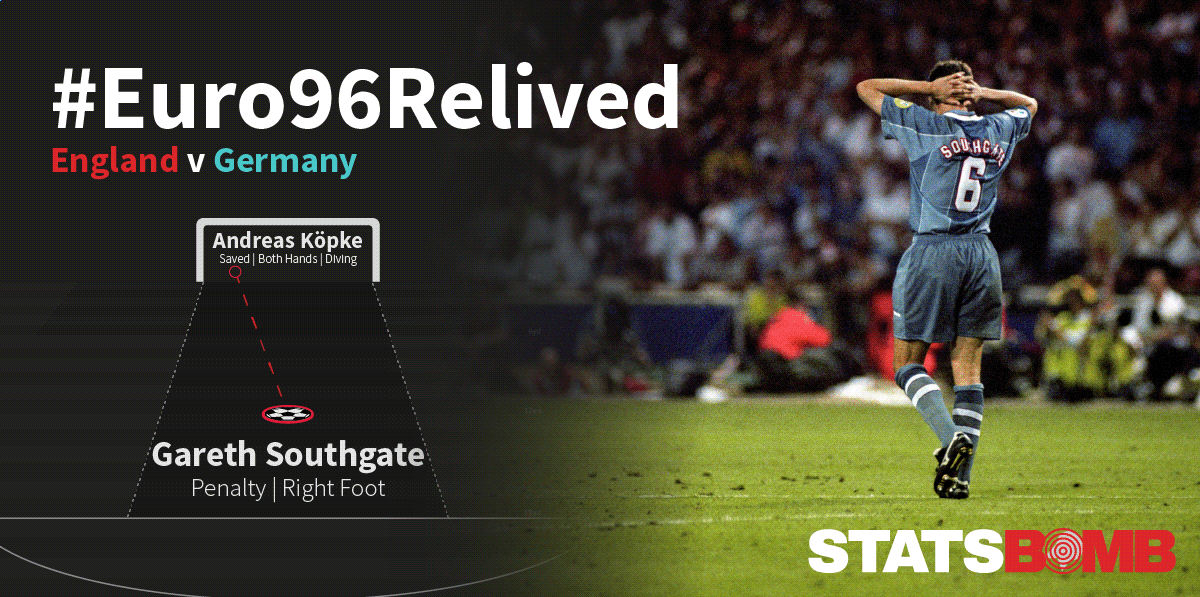

Steve McManaman and Darren Anderton kept to their wings in the first half, but were far more flexible in the second half. Gascoigne too saw a change in role from half to half, as he moved forwards as the game went on. Territory wise, England had far the better of it. Six players attempted over twenty passes in Germany's final third, while no German player attempted more than fifteen at the opposite end. David Platt in particular was neat and tidy with 94% passing, while unusually for a forward, Teddy Sheringham got through the most volume; 75 passes in total. In the end though, they couldn't make it pay and the game went to penalties.  Eleven penalties hit the back of the net before Gareth Southgate stepped up to take England's sixth, and missed. Once more it was not to be England's day, and the German team went on to the final, in which they conquered the Czech Republic to win the tournament.

Eleven penalties hit the back of the net before Gareth Southgate stepped up to take England's sixth, and missed. Once more it was not to be England's day, and the German team went on to the final, in which they conquered the Czech Republic to win the tournament.

If you enjoyed this look at Euro 1996 through a modern lens and want to learn more about how data can evaluate and describe football, you may enjoy our Introduction to Analytics course. Suitable for everyone from interested amateur right up to football professionals, it gives an accessible, fun and informative route into the world of data and football. Sign up here!

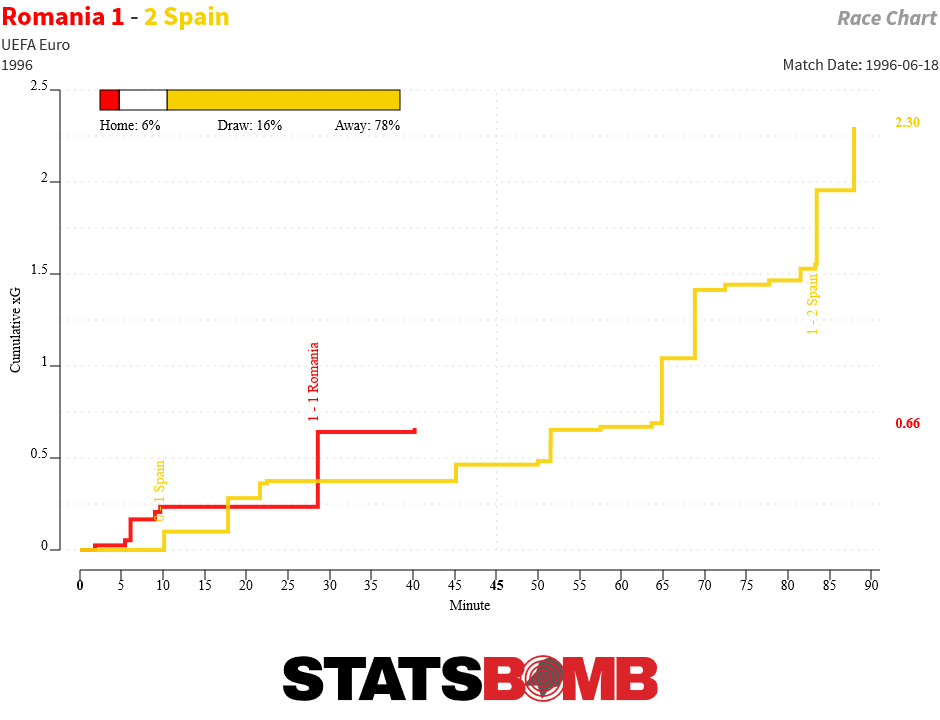

After a slow start to Euro 1996, England's 4-1 victory against the Dutch offered the promise of a deep run into the tournament. Next they faced a solid Spain side. ITV Sport continue to show these games and this is the fourth in our series, see parts one to three here: England 1 v 1 Switzerland England 2 v 0 Scotland England 4 v 1 Netherlands Spain had arrived in the quarter finals unbeaten in their group. They started off with two fairly quiet draws against Bulgaria and France, but came to life in their final game, much as England had, by beating the Romanians in a 2-1 victory that was more convincing than the scoreline suggested. Romania didn't even have a shot in the second half:  This game would be different though, up against an English team who top scored in the group stages. In the event the game was fairly cagey and even. Both team attempted around 600 passes and completed them at a percentage in the low 70s and while the shots were frequent, good chances were few:

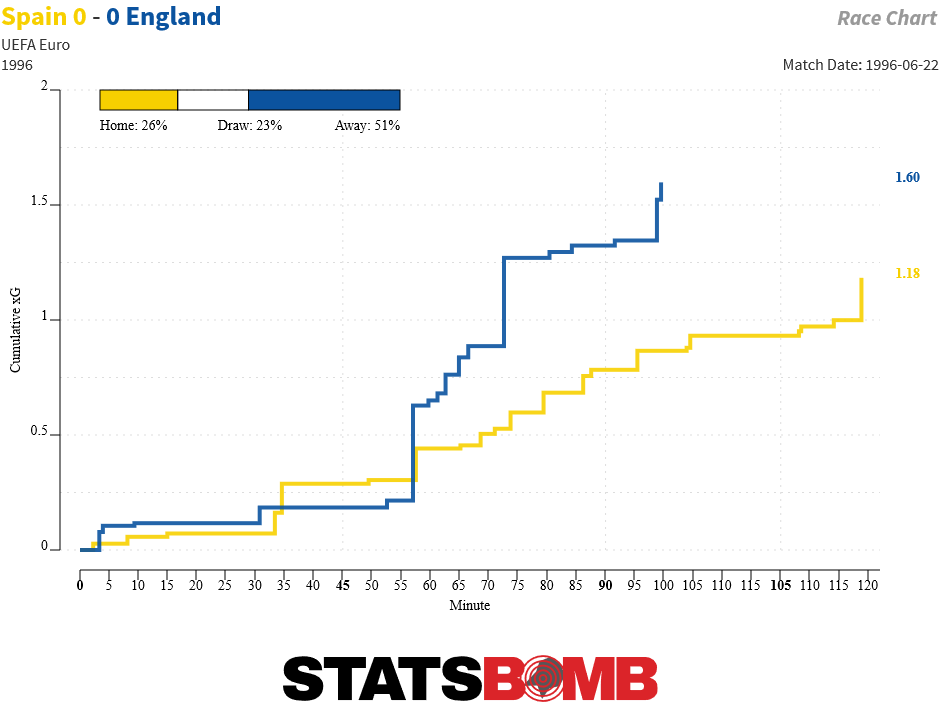

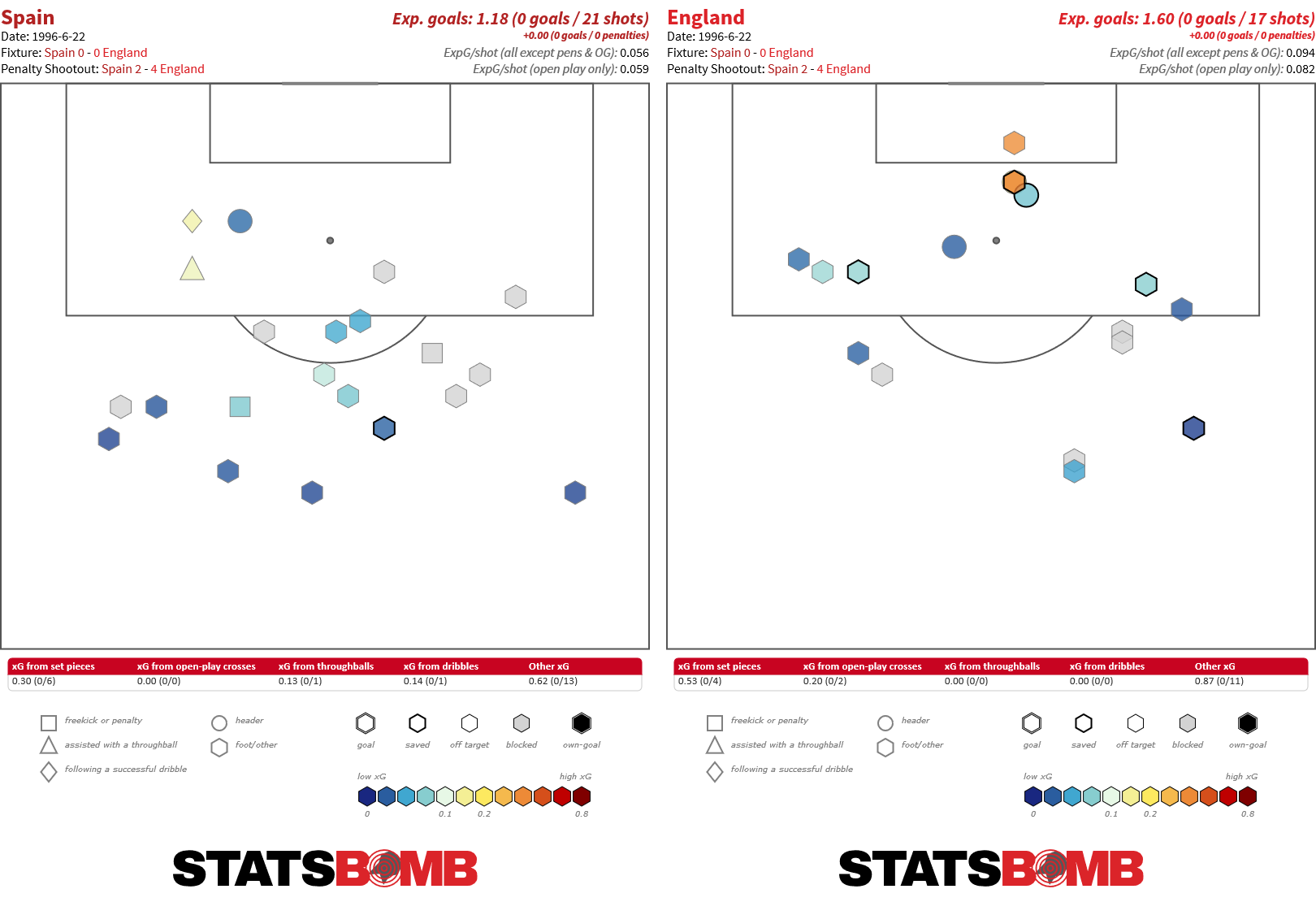

This game would be different though, up against an English team who top scored in the group stages. In the event the game was fairly cagey and even. Both team attempted around 600 passes and completed them at a percentage in the low 70s and while the shots were frequent, good chances were few:  Did England tire? Surely they didn't try and hold for penalties? Regardless they had no shots in the second half of extra time. Overall, Spain outshot England 21 to 17 but their shot quality and accuracy was poor; just one shot on target and a lot of efforts from long range:

Did England tire? Surely they didn't try and hold for penalties? Regardless they had no shots in the second half of extra time. Overall, Spain outshot England 21 to 17 but their shot quality and accuracy was poor; just one shot on target and a lot of efforts from long range:  And so penalties took centre stage, with memories of England's 1990 World Cup still fresh.

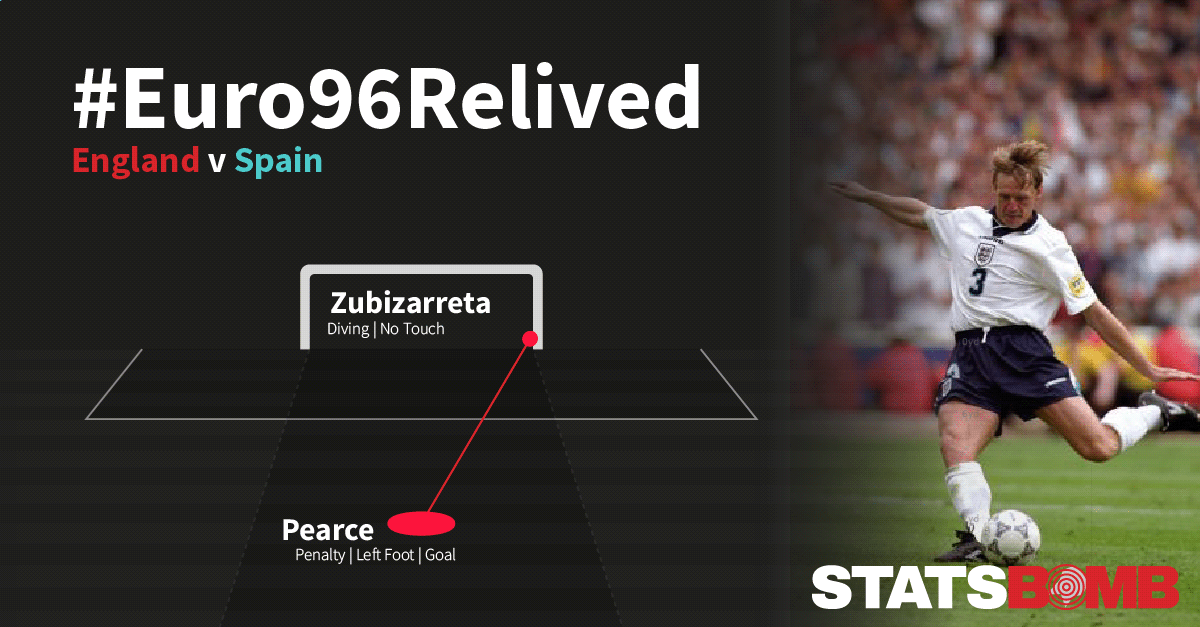

And so penalties took centre stage, with memories of England's 1990 World Cup still fresh.  Shearer scored with aplomb, Fernando Hierro--who had taken the most shots in the game-7-with no success, failed again as he crashed the ball against the bar. David Platt scored, as did Guillermo Amor. Stuart Pearce stepped up next, like Platt he'd taken a penalty against Germany six years before, however unlike Platt he'd missed. Time for redemption? A trademark powerful strike answered that question with a resounding "yes" and the Wembley crowd responded wildly. Alberto Belsué scored to temporarily quieten them, Paul Gascoigne scored to raise the noise levels once more. Lastly Miguel Ángel Nadal stepped up, put the ball to David Seaman's left and the keeper guessed correctly. The semi-finals and Germany beckoned for England.

Shearer scored with aplomb, Fernando Hierro--who had taken the most shots in the game-7-with no success, failed again as he crashed the ball against the bar. David Platt scored, as did Guillermo Amor. Stuart Pearce stepped up next, like Platt he'd taken a penalty against Germany six years before, however unlike Platt he'd missed. Time for redemption? A trademark powerful strike answered that question with a resounding "yes" and the Wembley crowd responded wildly. Alberto Belsué scored to temporarily quieten them, Paul Gascoigne scored to raise the noise levels once more. Lastly Miguel Ángel Nadal stepped up, put the ball to David Seaman's left and the keeper guessed correctly. The semi-finals and Germany beckoned for England.

If you enjoyed this look at Euro 1996 through a modern lens and want to learn more about how data can evaluate and describe football, you may enjoy our Introduction to Analytics course. Suitable for everyone from interested amateur right up to football professionals, it gives an accessible, fun and informative route into the world of data and football. Sign up here!

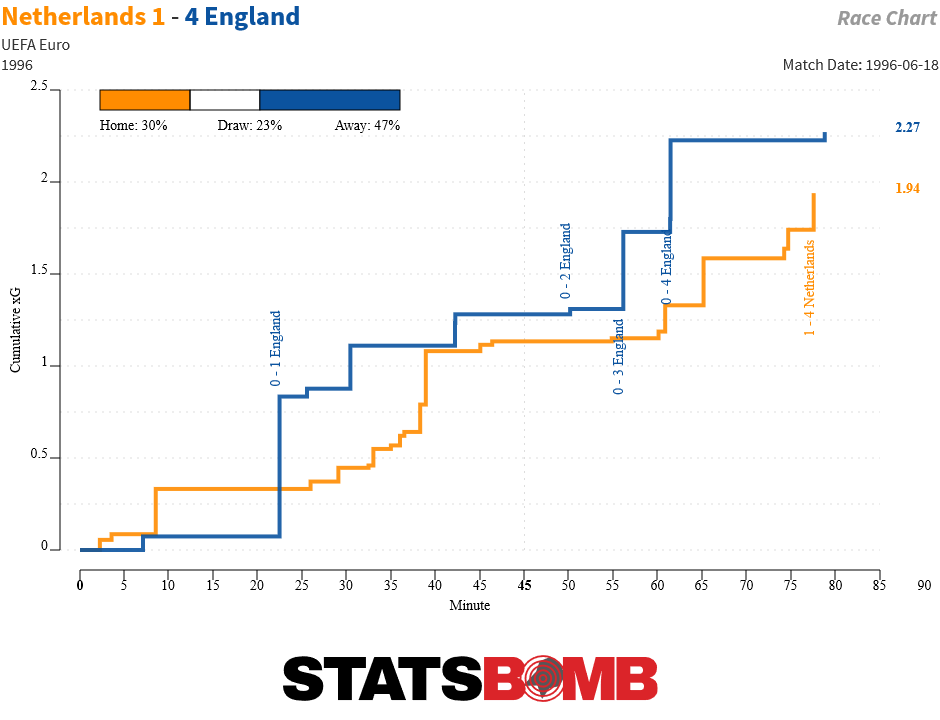

England marched into the quarter finals Euro 96 after a 4-1 destruction of the Netherlands, a game that was shown again on ITV Sport.

This is the third part of our series, see parts one and two here:

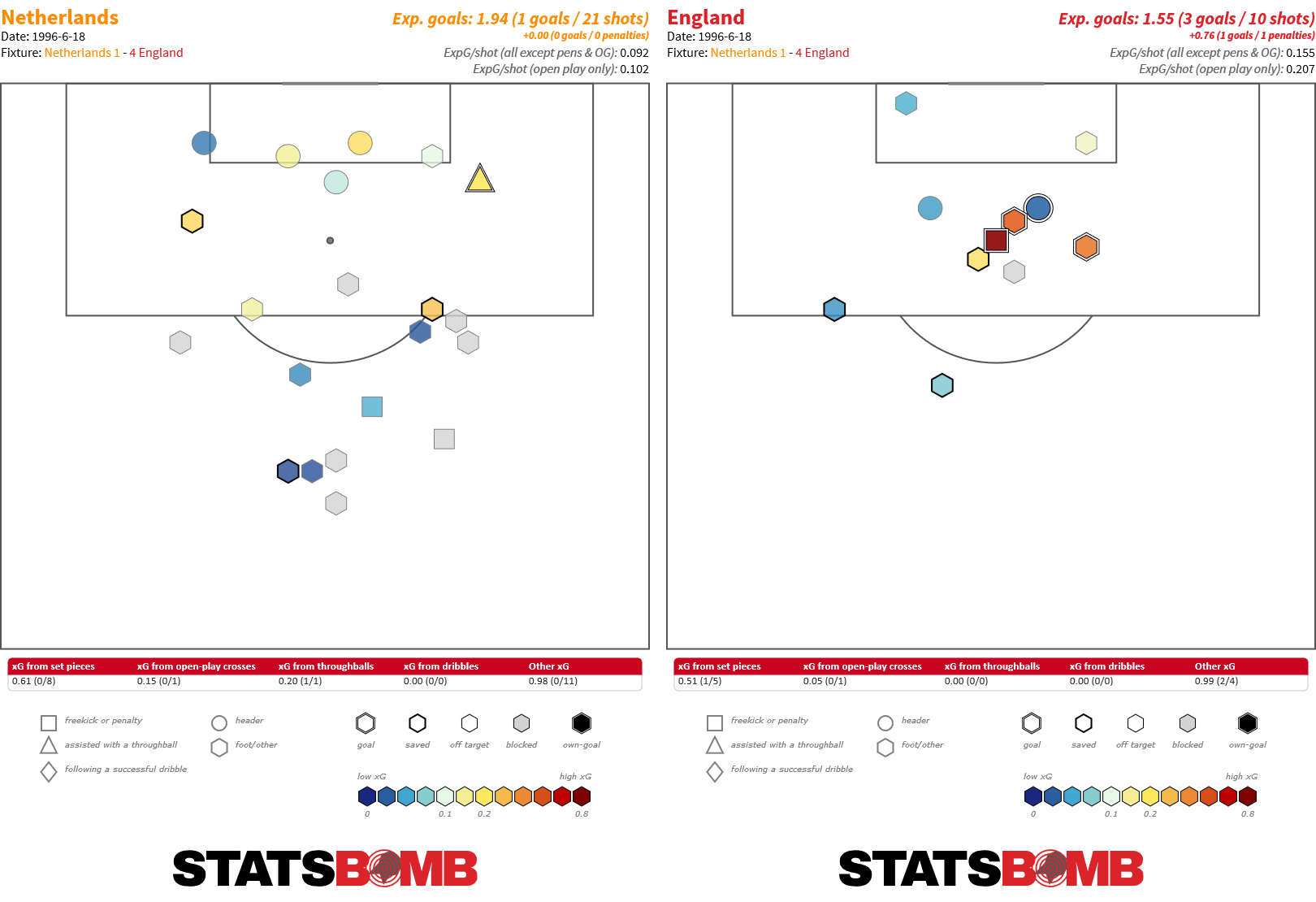

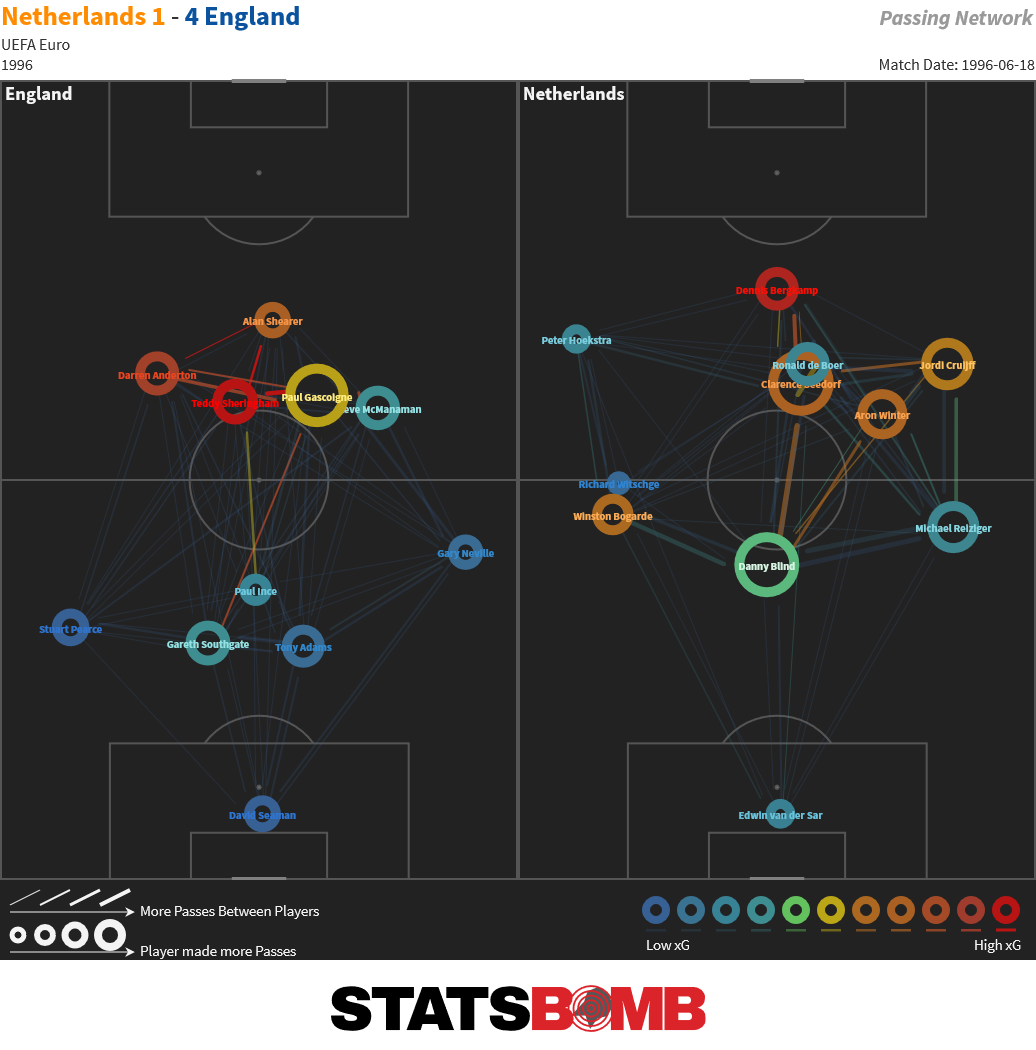

The main story of the game statistically was that England created and converted higher quality chances, while the Dutch struggled to turn shot volume into genuine goal threat:

After experimenting with formations against Scotland, England changed again, with a nominal 4-1-4-1, with a stark balance between attack and defence. We can see Paul Ince in ahead of the centre backs and the rest of the midfield and attack pushing up:

1-0 up at the half thanks to an Alan Shearer penalty, the goals came thick and fast for England in the second half.

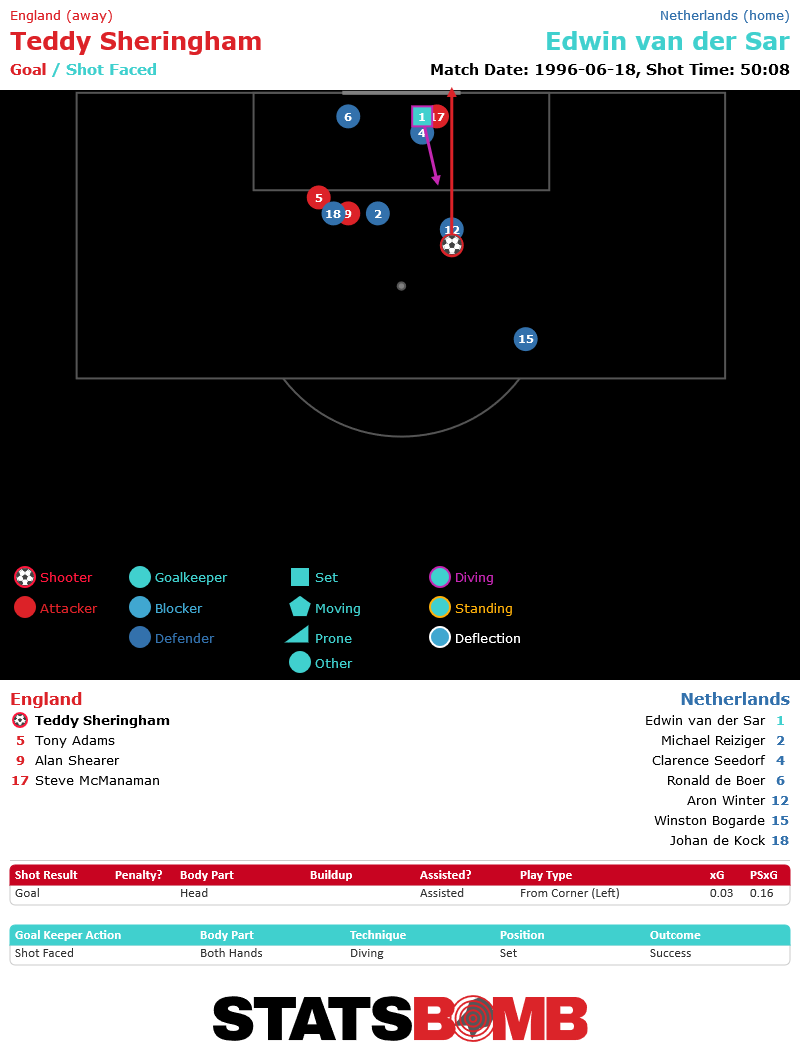

Firstly, Teddy Sheringham found the tiniest gap and headed in from Paul Gascoigne's corner. The difficulty to beat so many players and his man in a duel for the ball is reflected by the expected goal value of 0.03. This was a hard chance. No wonder he celebrated so gleefully.

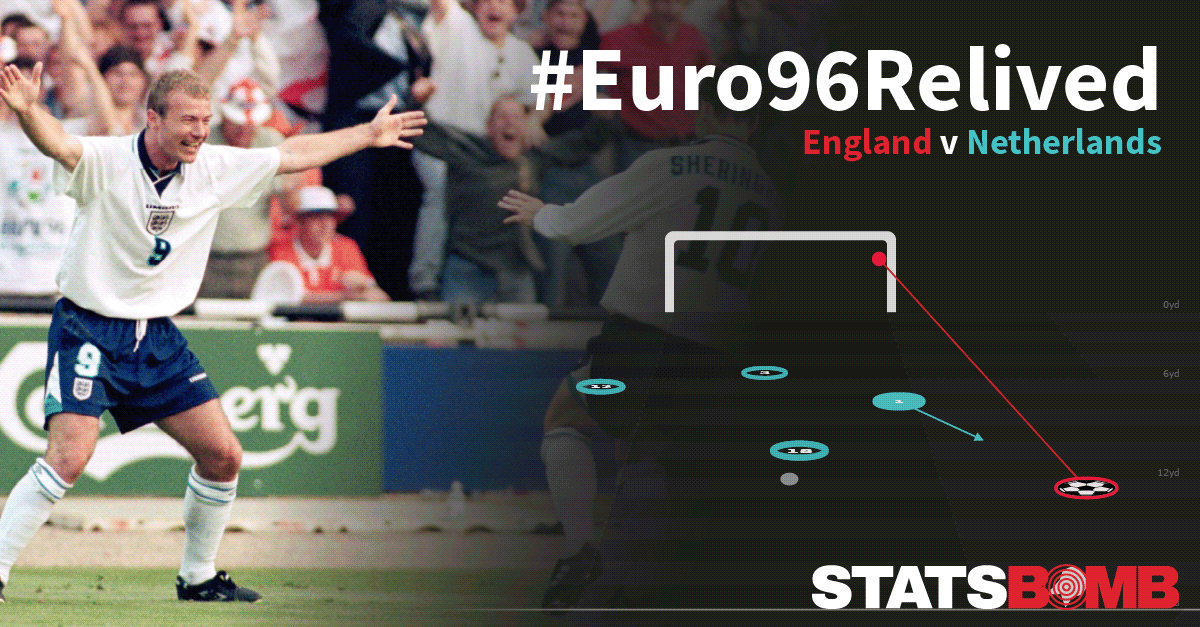

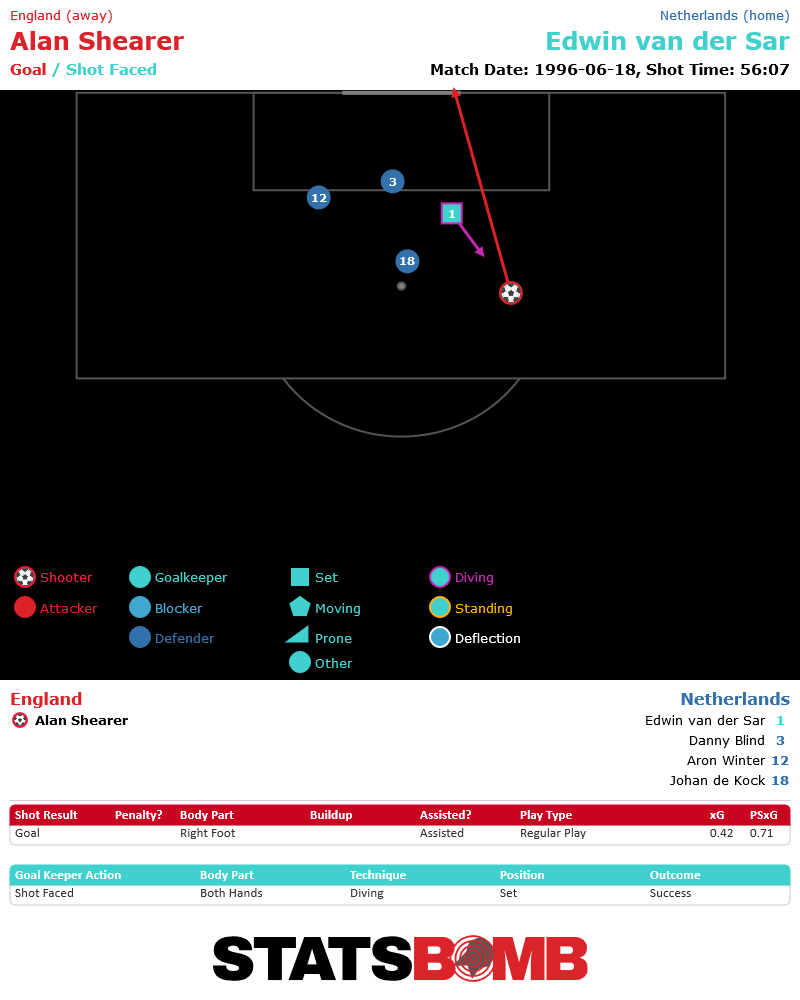

Then the most famous goal from the game, Shearer's back post finish after being teed up by Sheringham. Intriguingly, Sheringham has been quoted "if I shoot there I have a six out of ten chance of scoring" while if he rolls the ball to Shearer he has "an eight out of ten chance". Modelling probabilities via expected goals allows us to put real numbers onto this likelihood and we grade Shearer's chance at a shade over four out of ten (0.42)--that's still a great chance in terms of shot quality, but we suspect that a premium goalscorer such as Shearer would agree more with his teammate's assertion than our own.

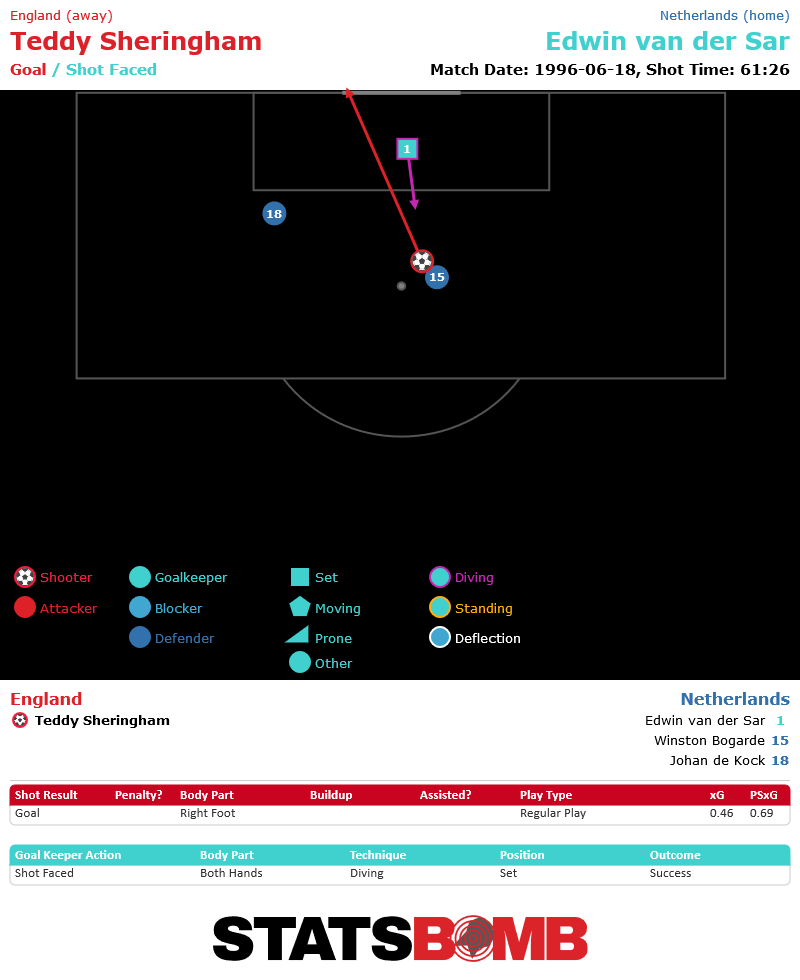

Sheringham's second goal made it 4-0 and came after the Dutch keeper Edwin van der Sar could only parry a long range shot from Darren Anderton. Outside of Shearer's penalty it was the best chance of the game grading out at 0.46:

Patrick Kluivert pulled one back late on to make the final score 4-1, but it was England's day. They topped the group and set up a meeting against Spain in the quarter finals.

Come back to see our review of that game on Saturday.

If you enjoyed this look at Euro 1996 through a modern lens and want to learn more about how data can evaluate and describe football, you may enjoy our Introduction to Analytics course.

Suitable for everyone from interested amateur right up to football professionals, it gives an accessible, fun and informative route into the world of data and football.

Our history of the European Cup continues with the 1995 final between Ajax and AC Milan. We are only six years on from the match we covered last time out, but there have been some significant changes in the meantime. The offside law has been altered, the back-pass rule has been introduced and the European Cup has been rebranded as the Champions League.

This is the fourth entry in this series looking at a final from each decade of the European Cup. We’ve already covered:

- 1960: Real Madrid 7 - 3 Eintracht Frankfurt

- 1972: Ajax 2 - 0 Inter Milan

- 1989 - AC Milan 4 - 0 Steaua Bucharest

This time around we have a contest between Louis van Gaal’s young Ajax team and an AC Milan side appearing in their third consecutive final, and their fifth in a seven-year stretch beginning with their victory in 1989 that yielded three triumphs. They were already well-acquainted, having met twice during the group stage, with Ajax victorious on both occasions.

Differing Styles, Similar Results

The last two finals we covered both featured winning teams who established territorial dominance with a high press. Both Ajax in 1972 and Milan in 1989 were able to pen their opponents in and seriously inhibit their ability to advance into dangerous positions. In contrast, this match was a much more even contest between differing yet equally valid approaches.

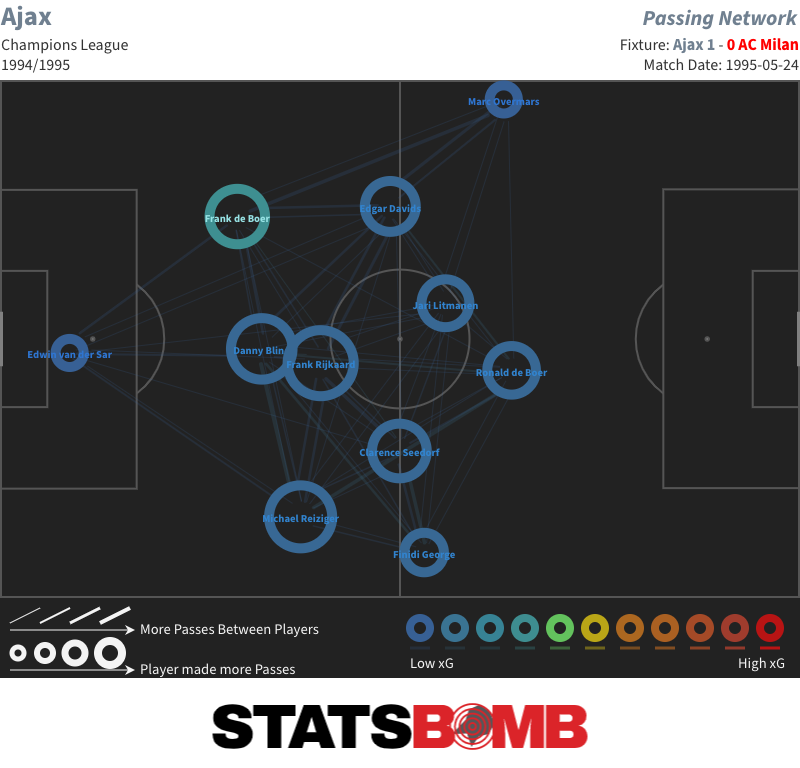

Ajax held the lion’s share of possession (61%) and sought to patiently construct play from the back with a ball progression scheme that was far more systemised than any we’ve seen in the previous finals in this series. Their 3-4-3 system with a diamond midfield provided a central column of reference points around whom the rest of the team could triangulate.

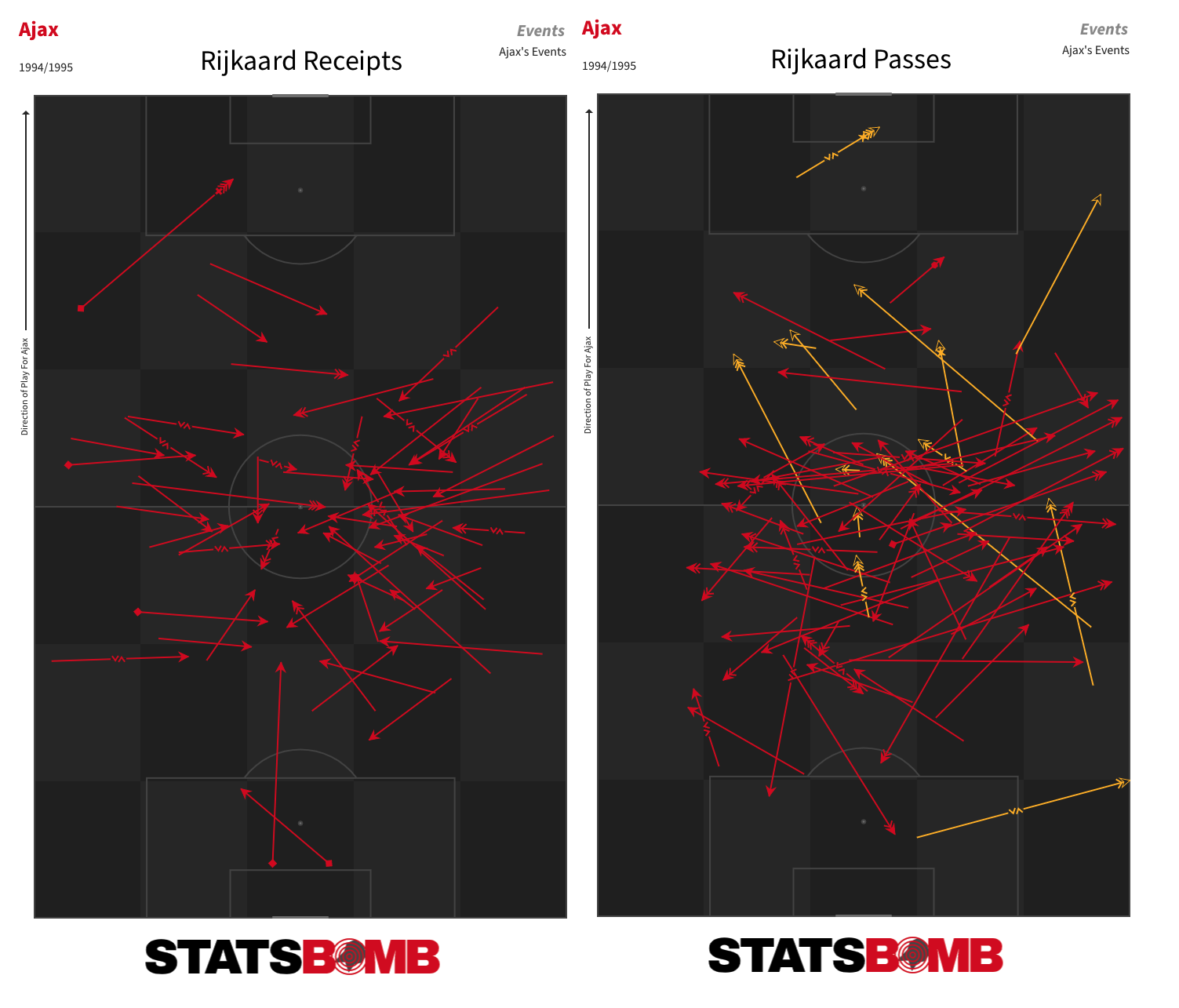

Danny Blind, Frank Rijkaard and (until he was moved back into midfield) Ronald de Boer frequently acted as pivots to change the angle of attack -- often with back-to-goal layoffs in the case of the latter-mentioned pair. Van Gaal’s side were highly methodical in working the ball from side-to-side in search of openings, and Rijkaard was the brains of the operation.

Blind and Rijkaard were the experienced figures in an otherwise young team. The remainder of the starting XI were all 25 or younger, while the two substitutes, Nwankwo Kanu and match-winner Patrick Kluivert, were both 18. Six of the starting XI, and seven of the 13 players used were academy graduates. This side provided the spine of the Netherlands teams who reached the semi-finals of both the 1998 World Cup and Euro 2000.

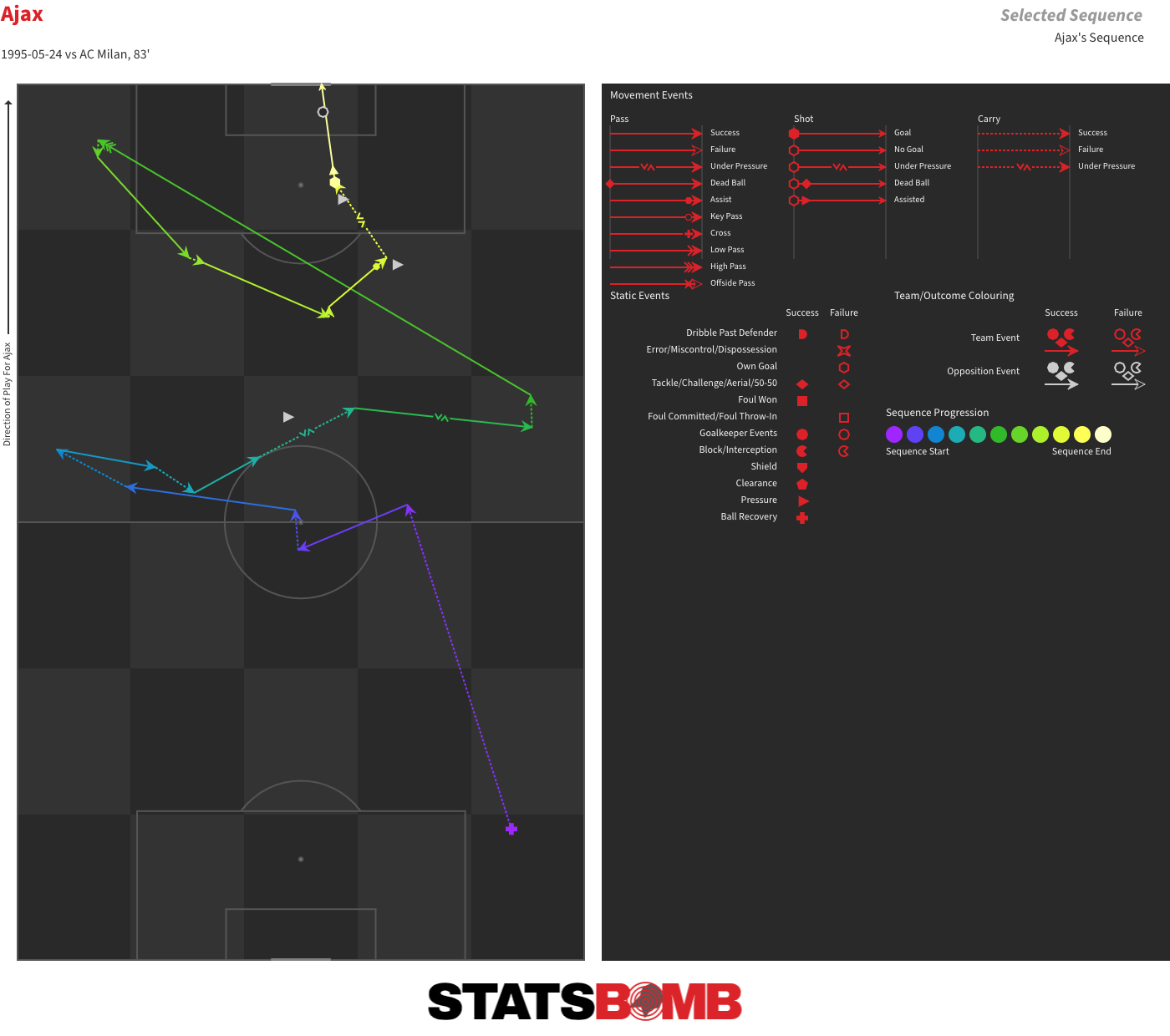

The degree to which Ajax’s ball use was structured was made clear by how quickly they paused counter-attacks to reset their positions once initial progress had been slowed.

That was exactly what happened on their winning goal. Ronald de Boer burst forward out of defence into midfield, only to halt as options ahead of him narrowed. From there, the ball was worked out to the left, across to the right, back to left, and from there into the centre, where Rijkaard found Kluivert to prod home from inside the area.

This Ajax side utilised possession as a means of control. They denied it to the opposition, and moved the ball in such a way as to leave themselves adequately positioned to win it back once lost. It was almost more of a defensive tool than an attacking one. Ajax kept eight clean sheets across their 11 matches in the 1994-95 competition, including four in their five knockout round matches. It was the same story the following year, when they lost on penalties to Juventus in the final after recording eight clean sheets in 10 matches to get there.

To a degree, Milan were content to allow Ajax the ball and then drop off to form a solid defensive block. They didn’t regularly contest possession chains and leaned on their experienced and well-organised backline to defend their area. Alessandro Costacurta, Franco Baresi and Paulo Maldini were still in place from the 1989 final.

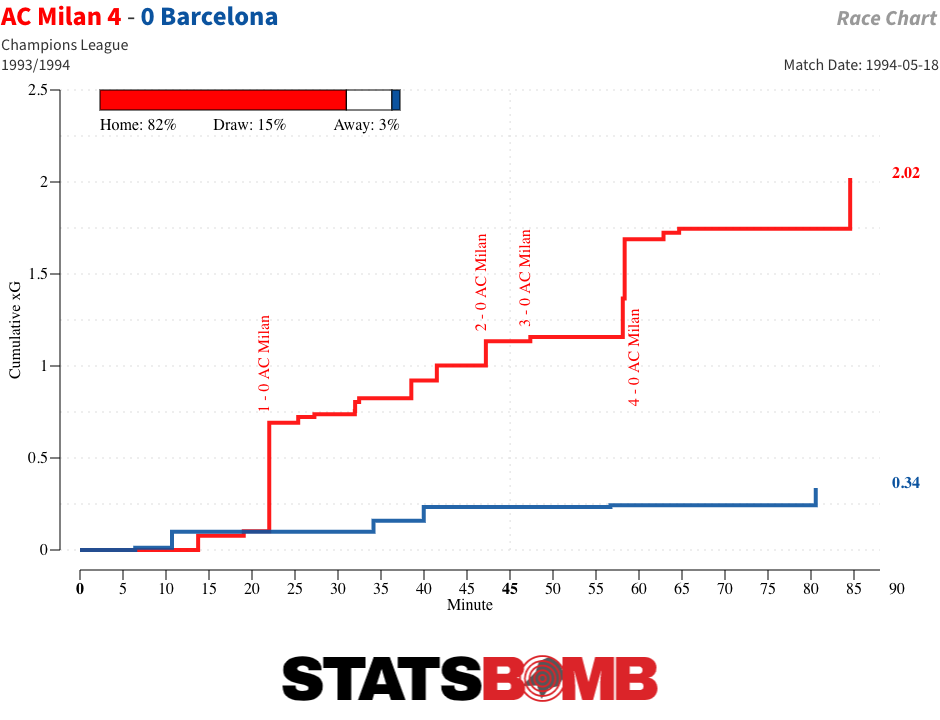

In total, they lined up together in four of the five finals Milan contested in this period. The only time they hadn’t was in the previous year’s final. With Costacurta and Baresi unavailable, Milan chose not to rely on defensive stability and instead took the game to Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona. The result was a convincing 4-0 victory.

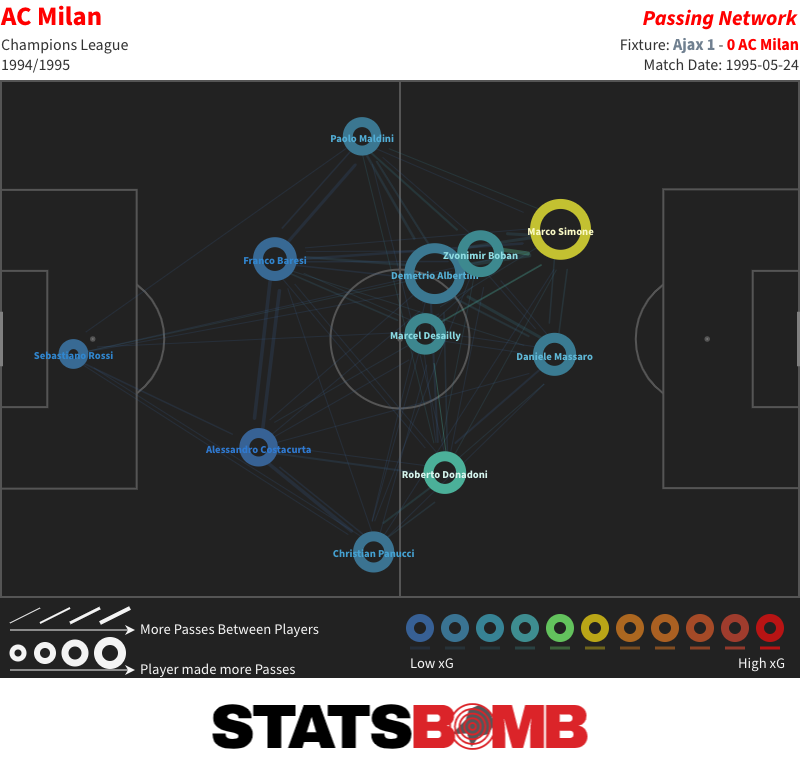

That didn’t seem to alter Fabio Capello’s underlying thinking. This late-era Milan side lacked the sheer offensive might of the earlier incarnations, and a cautious approach probably played better to their strengths. This was a much flatter 4-4-2 than the one we saw in the 1989 final, with only Zvonmir Boban’s movements infield from the left upsetting the symmetry.

Milan’s comfort in their game plan was illustrated by Capello’s level of inactivity on the sidelines. Van Gaal was by some distance the more animated of the two coaches, and there was a reminder that his dramatic reenactments of on-pitch incidents weren’t exclusive to his spell at Manchester United.

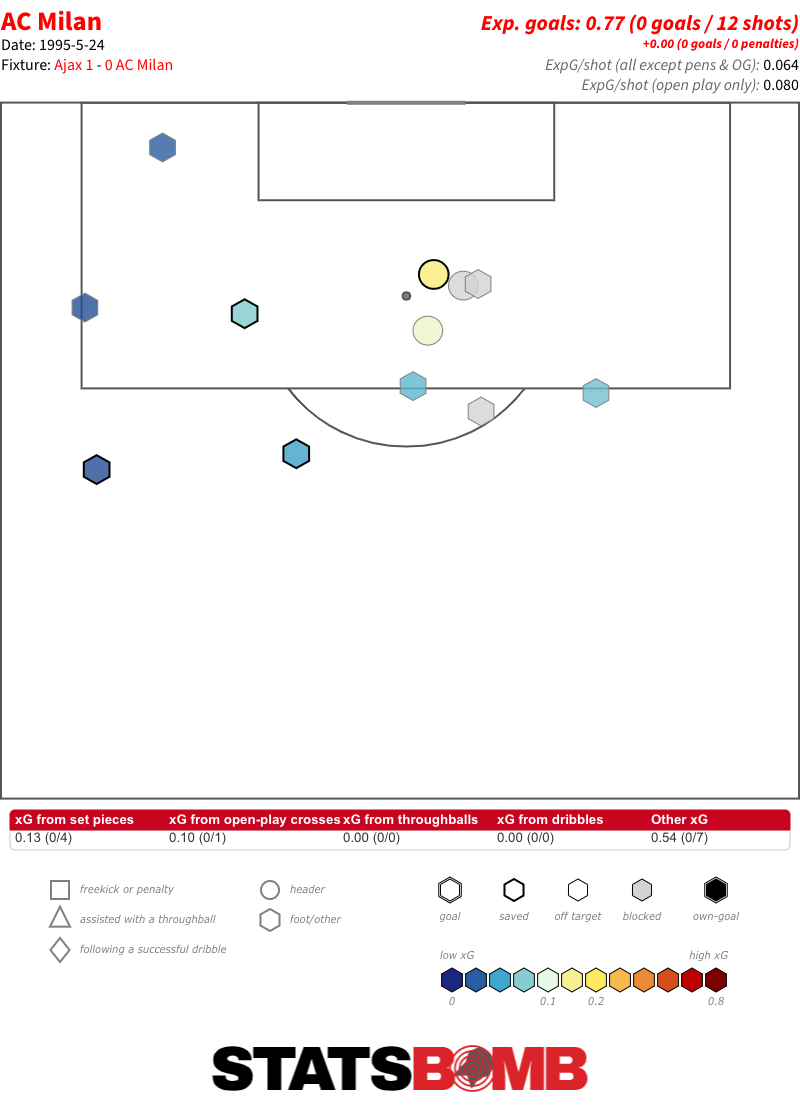

For much of the match, there was very little to separate the teams. Ajax moved the ball and moved the ball but struggled to penetrate. Marc Overmars completed just two of his 10 attempted dribbles from the left. Milan were much more direct in the way in which they moved forward, with longer balls through the centre and into the channels, but the majority of their efforts were just potshots.

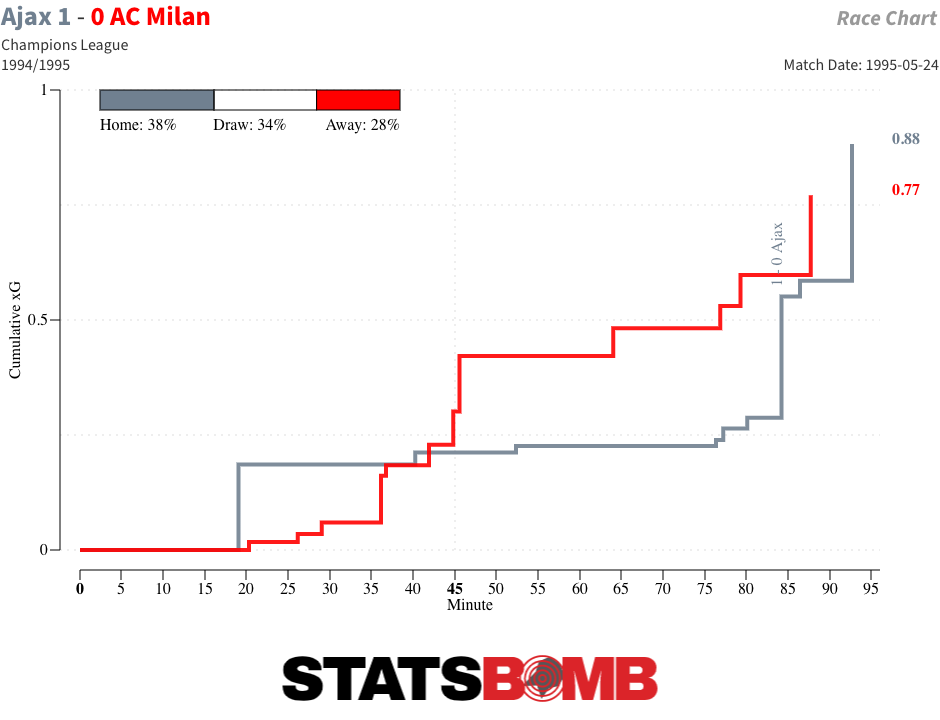

Neither team created all that much. The final shot tally of 21 was a full 14 less than in any of the previous three finals in this series. The xG sum of 1.65 was also the lowest so far. Ajax generated the clearest opportunity and took the spoils, but it was a match that could easily have gone either way.

Edwin Van der Sar

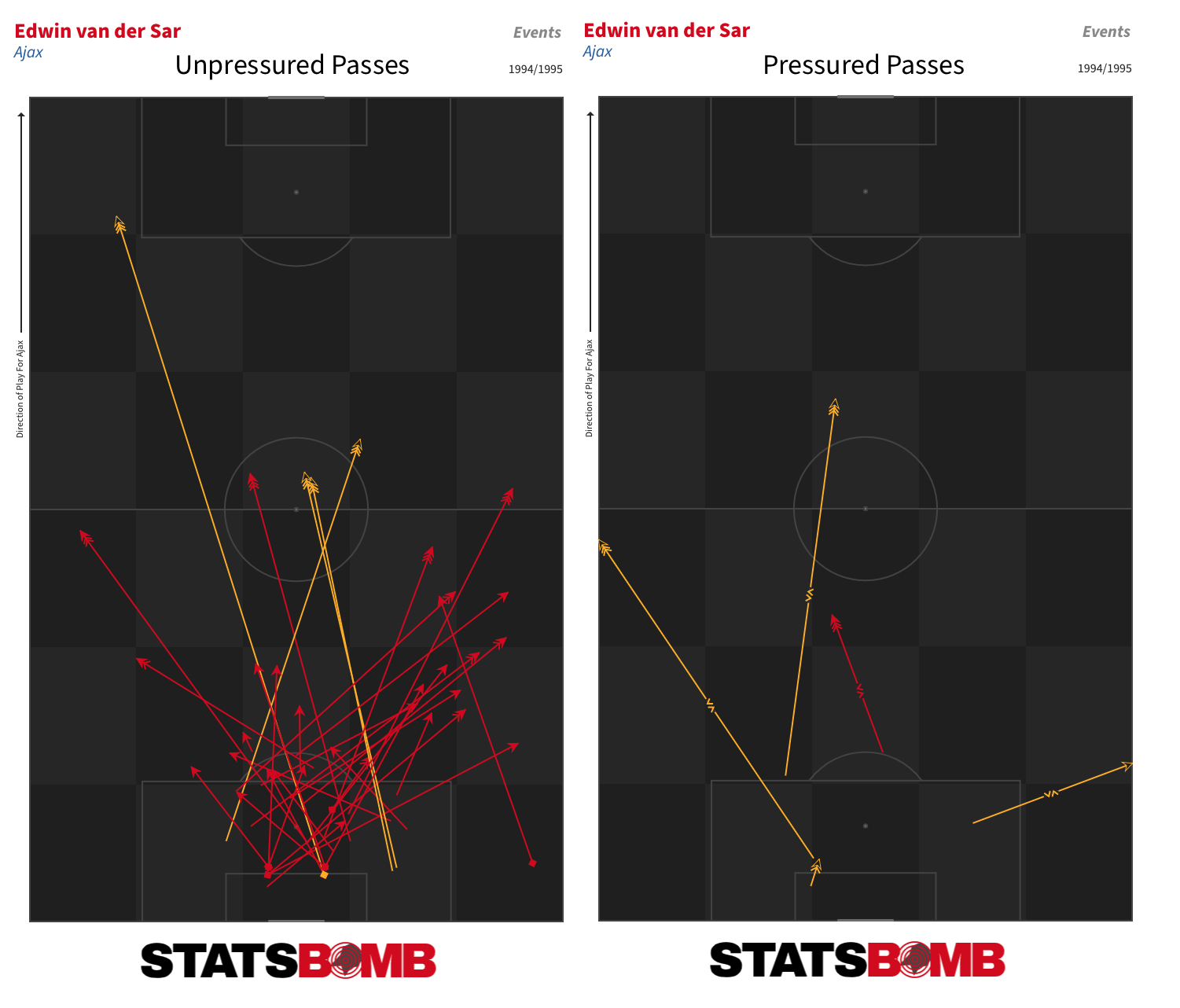

Edwin van der Sar was somewhat of an early template for the modern-day goalkeeper. He was certainly not the first custodian to show proficiency with the ball at his feet, but he was one of the most prominent examples of a goalkeeper with that skillset in the years directly following the outlawing of the back-pass in 1992.

That was evident here. He very rarely went long without reason, and while he wasn’t quite as slick in his execution as many of the goalkeepers of today, he was willing to take a touch to open up an angle for a pass or draw a degree of opposition pressure. There were a couple of awkward moments when he was directly pressed, but he otherwise used the ball in exactly the manner Ajax’s system required of him.

His completion rate of 79% was comparable to those of Alisson or Manuel Neuer in last season’s competition, but was also achieved with a longer average pass length. It’s worth noting, too, that a greater proportion of his passes were attempted under pressure. That completion rate dropped slightly over a larger sample size for the Netherlands at Euro 96 but was still within the range of some of the modern game’s most competent distributors.

Van der Sar was not the most aesthetically pleasing goalkeeper, never quite seeming to be in complete control of his lanky frame. He had at least a couple of particularly flappy moments in this match. But he enjoyed plenty of success over the course of his career and was an early indication of the direction in which his profession was heading.

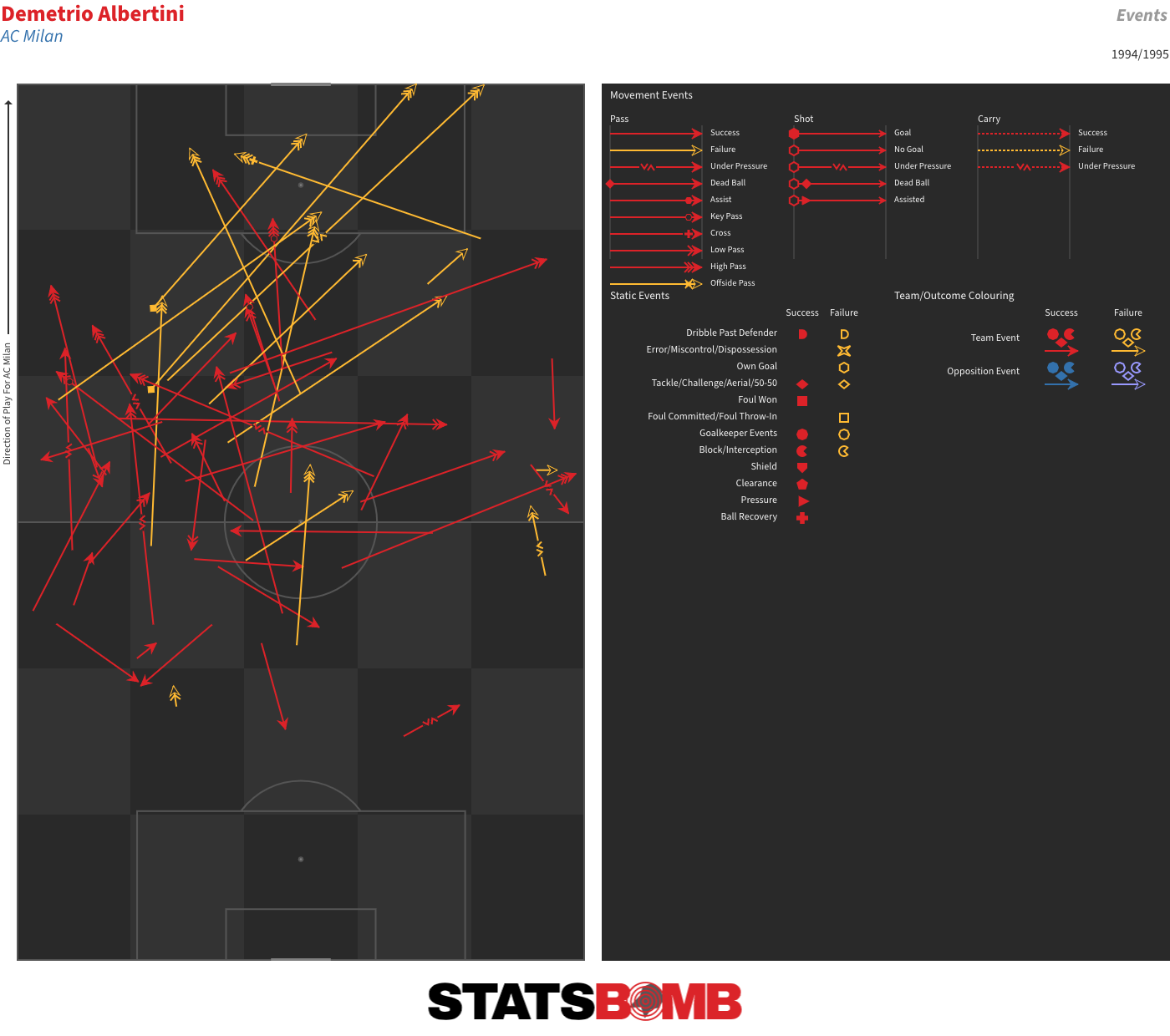

Demetrio Albertini

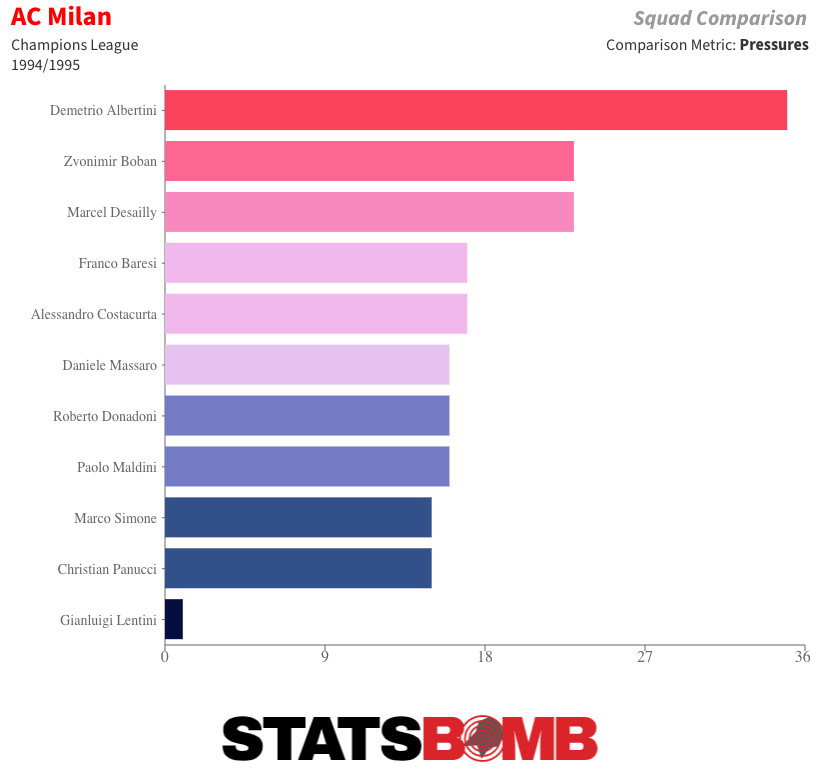

It is worth highlighting the importance of Demetrio Albertini to this Milan side. He was a consistently progressive passer in transition, the Milan player who most often moved the ball into the final third, and he also created more chances in open play (three) than any other player. His clipped pass into Daniele Massaro for one of the striker’s patented swivel shots just past the hour mark was particularly well-executed.

He also got through a ton of work off the ball, leading his team in interceptions, tackles and pressures.

Albertini had played alongside Rijkaard, his opposite number four, at Milan, and they would later join forces once more when Rijkaard, then head coach at Barcelona, signed him in 2005 to see out of the final few months of his career at the Camp Nou.

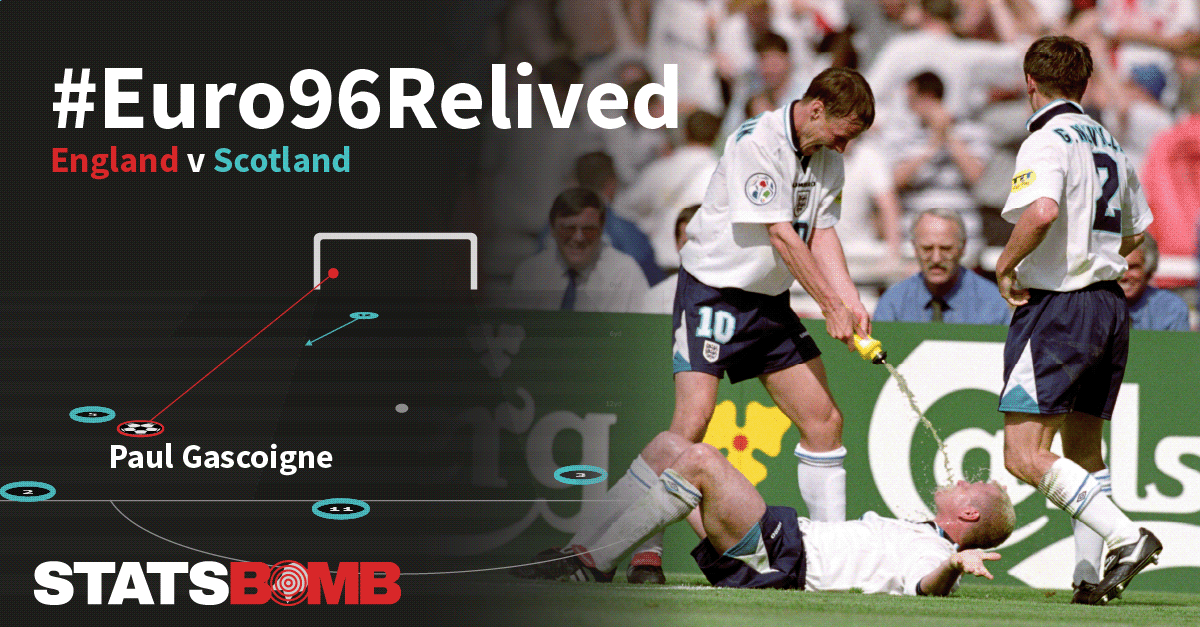

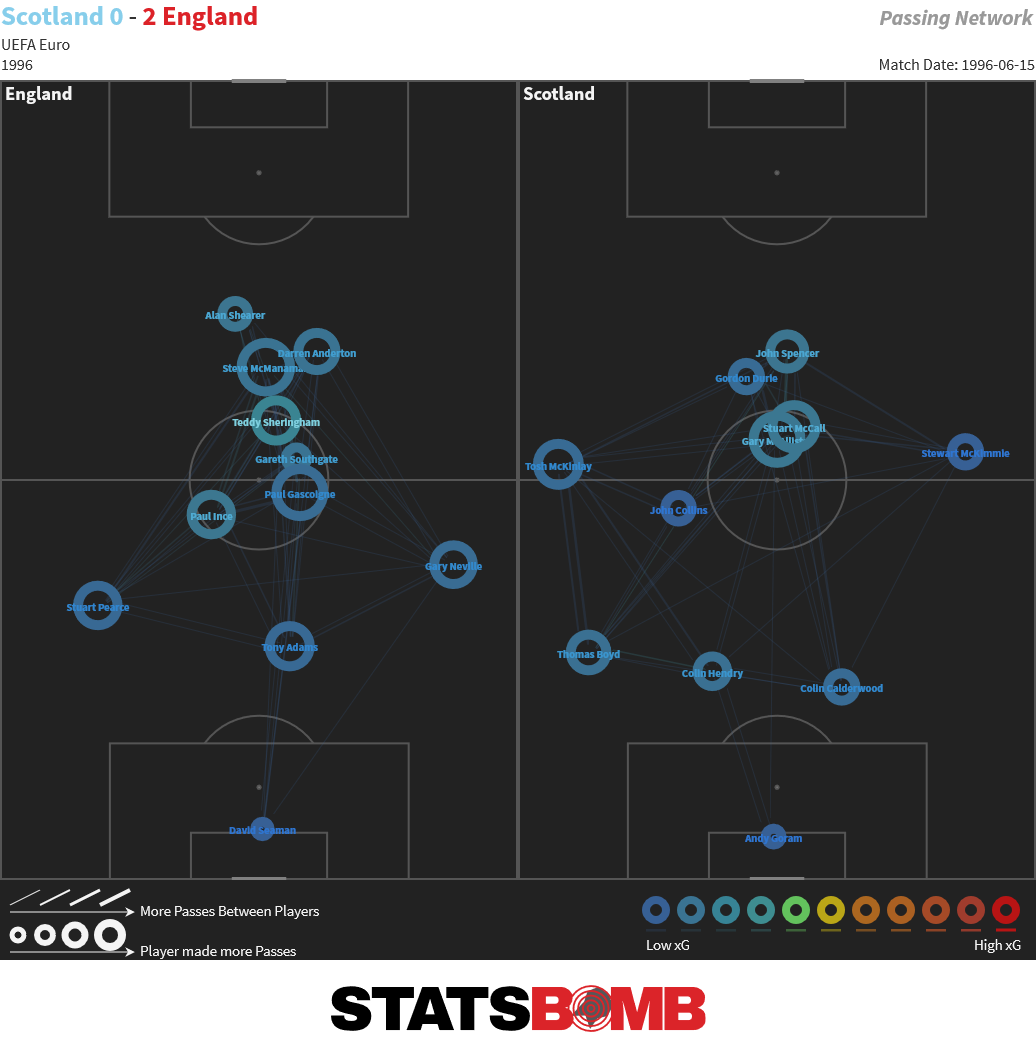

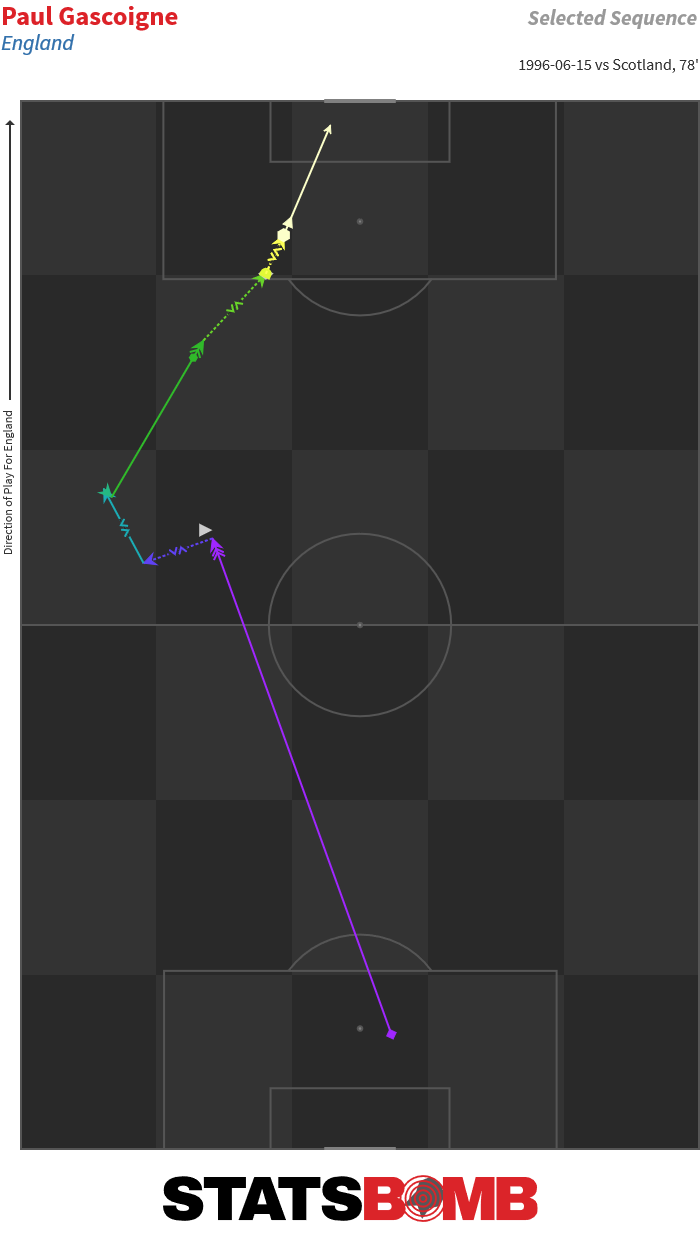

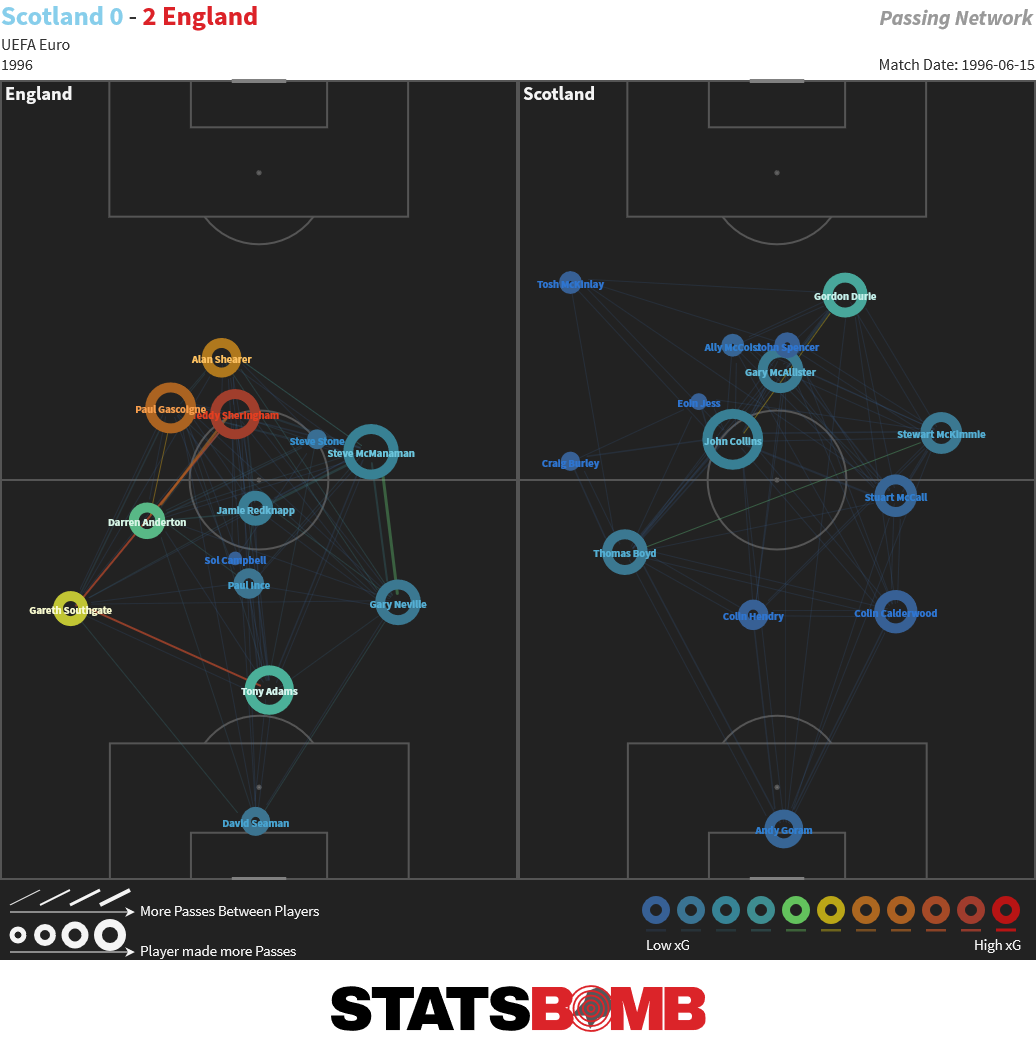

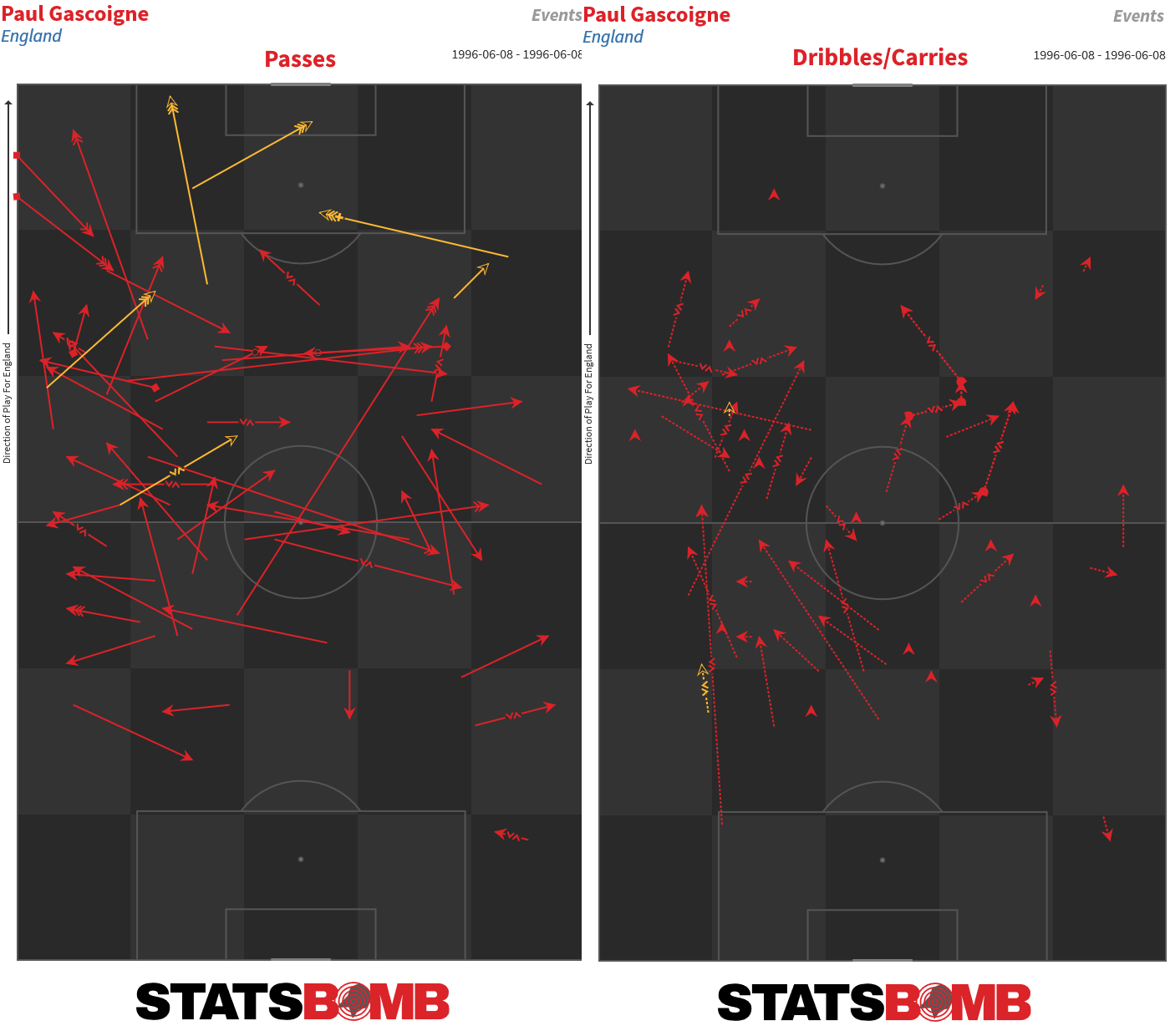

After a mediocre 1-1 draw against Switzerland, could England get back on the right track back in a familiar role as the "Auld Enemy" against Scotland? Terry Venables' 4-4-1-1 from the Switzerland game gave way to something a little different. With full backs Gary Neville and Stuart Pearce flanking Tony Adams in a back three, Gareth Southgate stepped into midfield alongside Paul Ince, with Paul Gascoigne tasked with being a central creative outlet. Teddy Sheringham continued working off Alan Shearer up front, while Darren Anderton and Steve McManaman rotated frequently between the wings. As such the first half pass networks appear congested; but this is merely a reflection of the positional flexibility the England team played with:

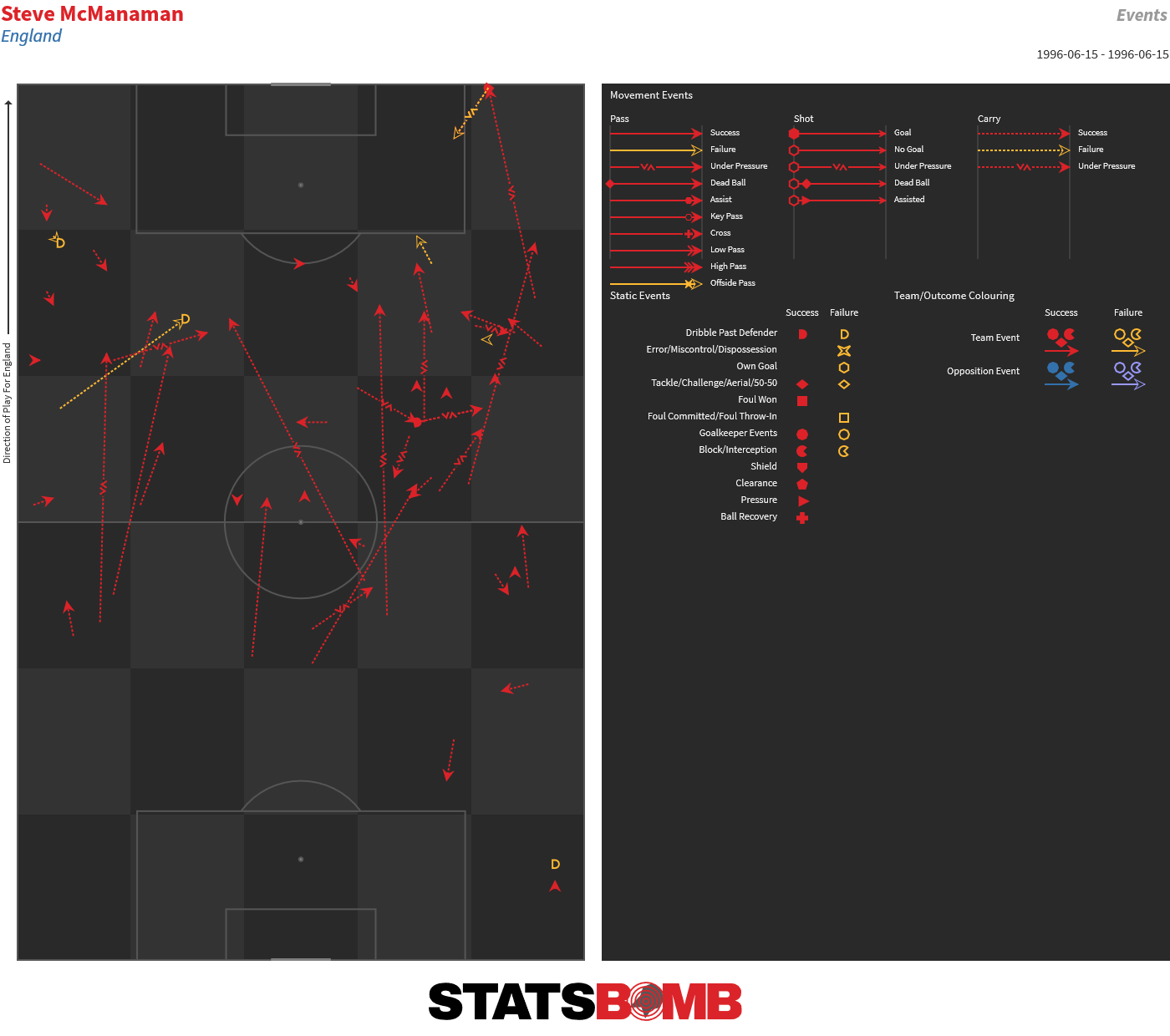

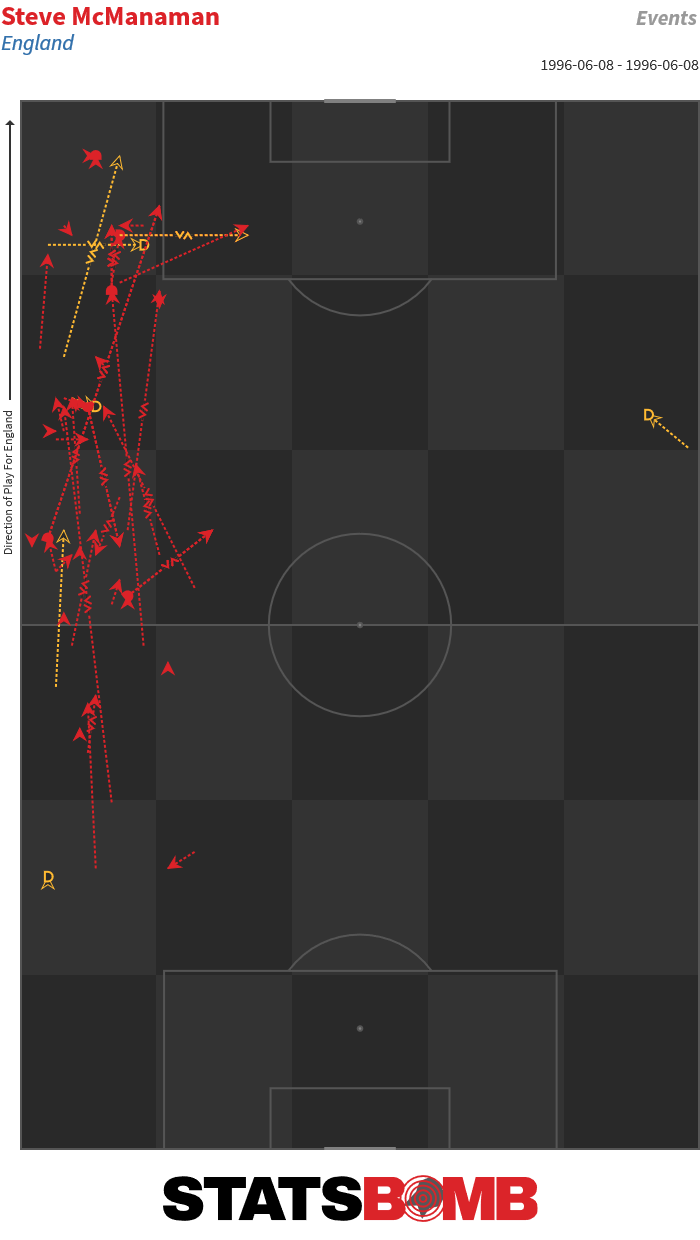

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

England made a key change at half-time, Jamie Redknapp came on for Stuart Pearce. This meant Southgate could move back to his more usual position in the back line, and Redknapp's passing range could allow England a little more control in the middle of the park. The opening minutes of the second half saw England come to the fore, Sheringham missed an open header deep inside the box and 2 minutes later they were rewarded when Shearer opened the scoring with a far post header from Neville's cross. However, it was Steve McManaman who set the tempo here, moments before freeing Neville to make that cross he'd advanced from halfway before whistling a left foot shot past the post. Indeed, McManaman's ball carrying was a notable plus again in this game, and he saw more of the ball (48 passes, 22 in the final third) than anyone else on the pitch with good retention (86% completion) for a wide player. Here we see how he carried the ball effectively, a series of long runs deep into Scotland's half.

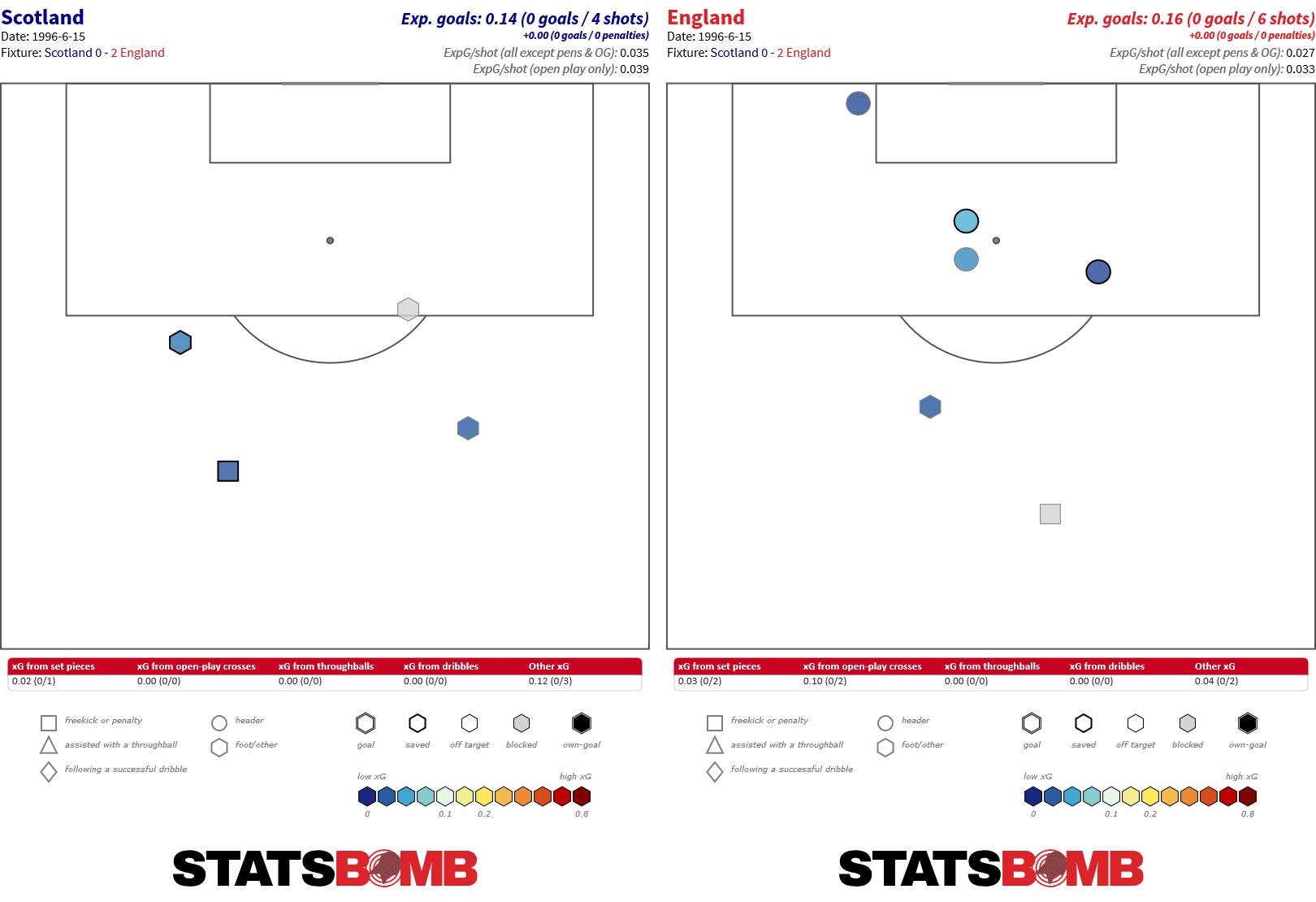

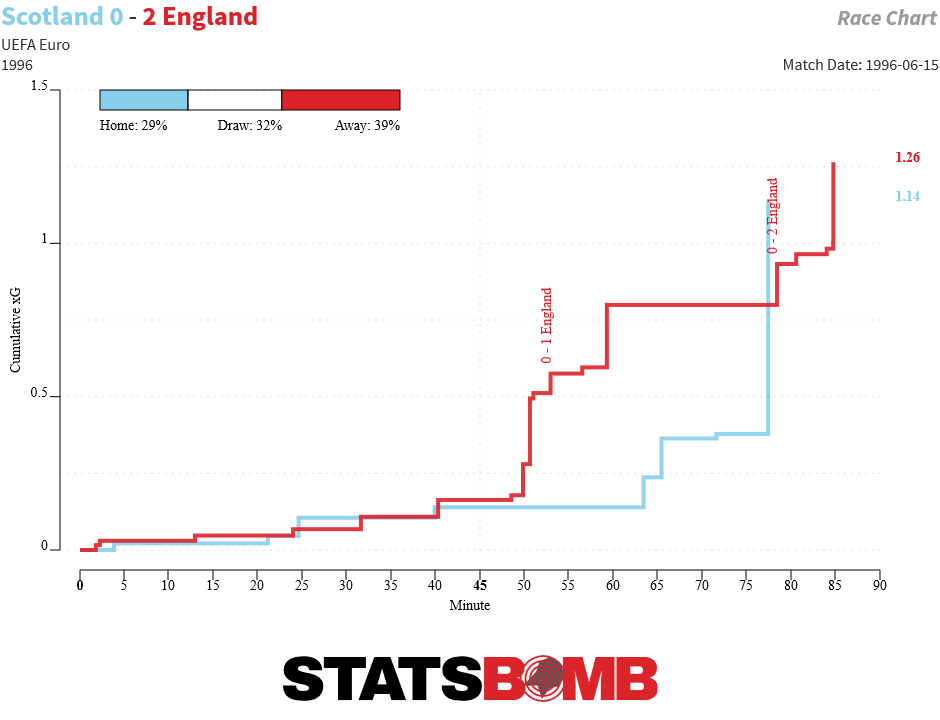

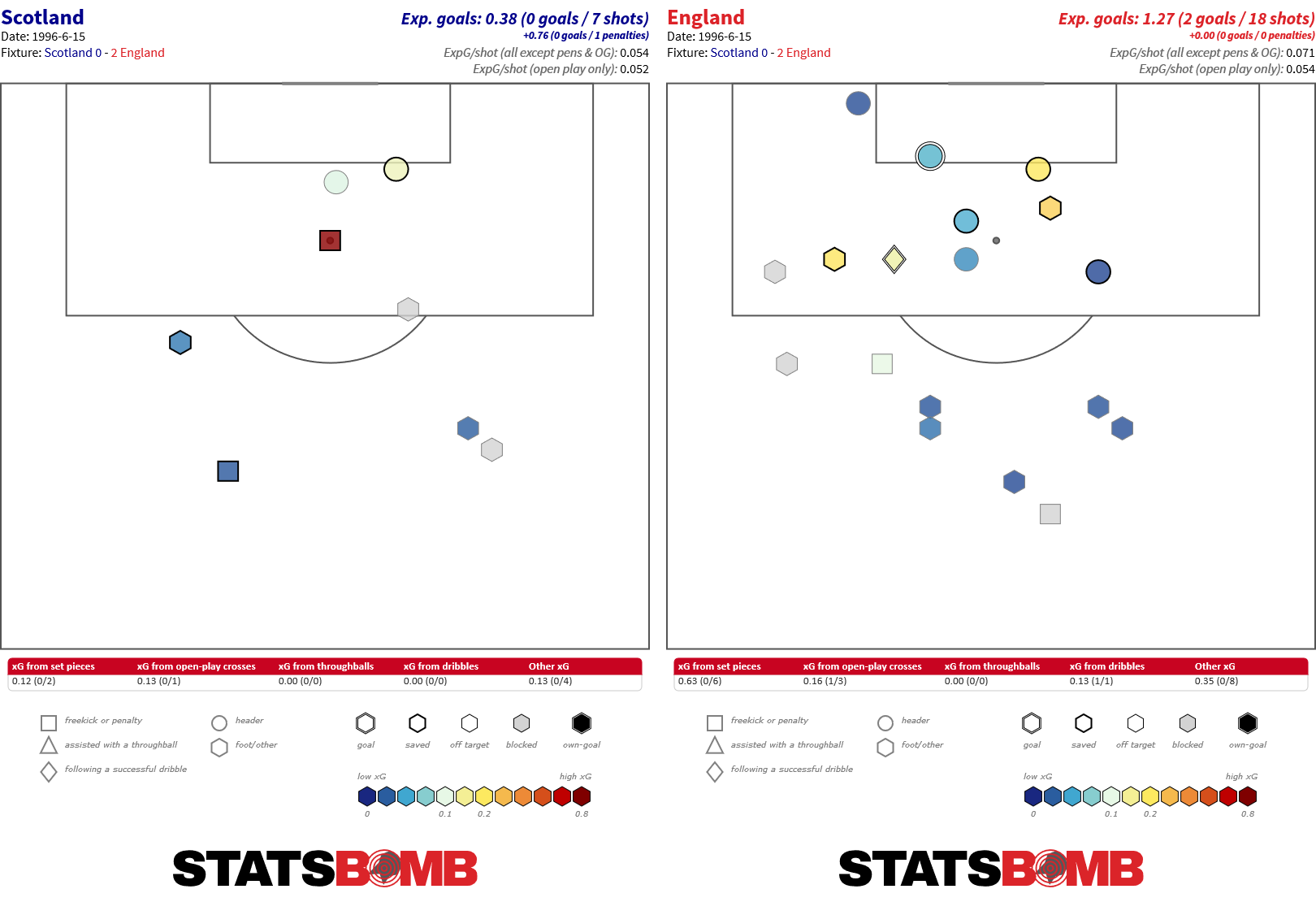

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

By the end of the game, England were good for their win. The penalty had been Scotland's only good quality chance in the game and England's shot count and expected goals were superior:

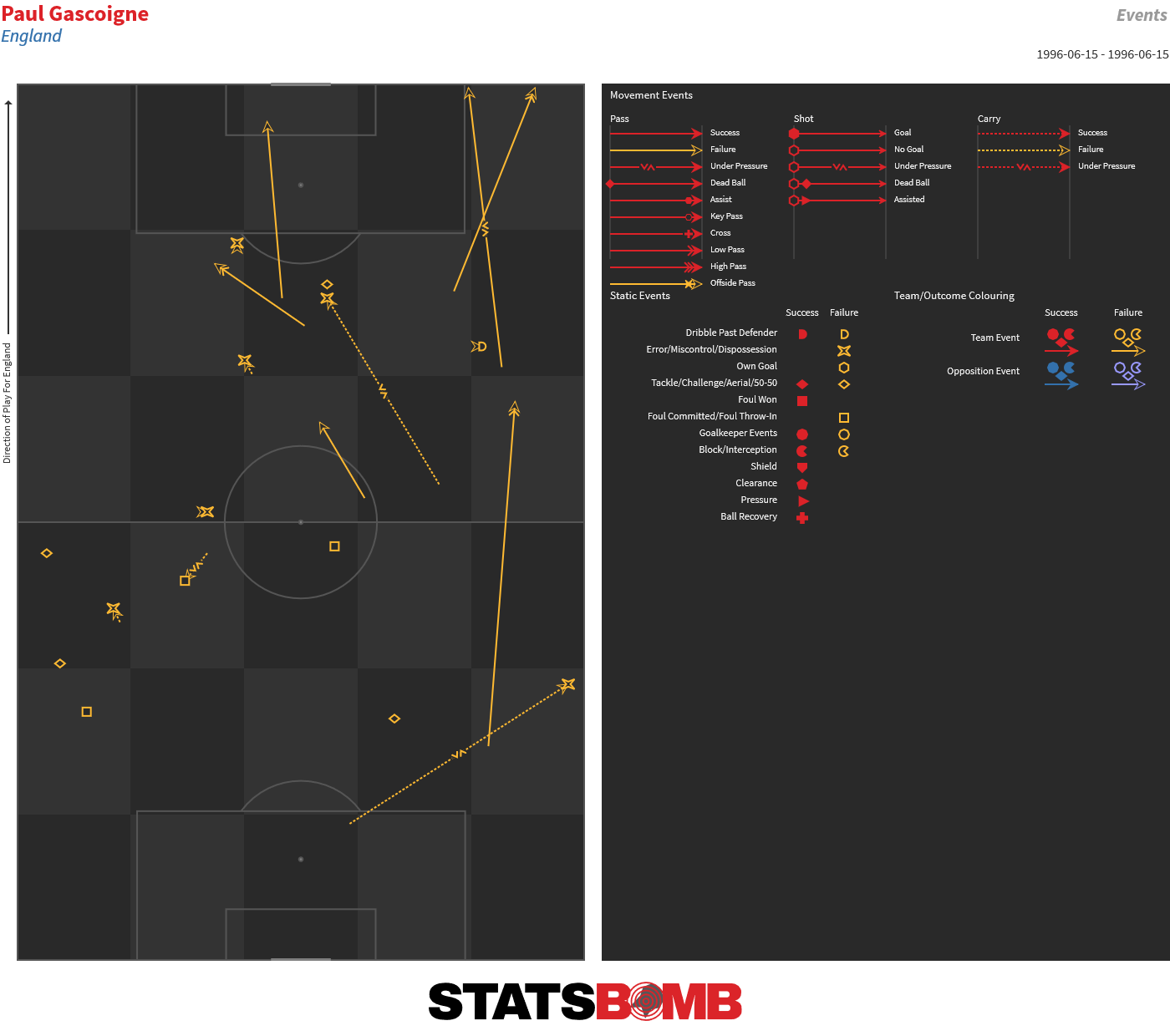

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch:

The change of personnel at half time appeared to be effective and the second half shape of the teams was more forward inclined for England than in the first half, Gascoigne especially found himself higher up the pitch and with Southgate back in the back line, the three central midfielders occupied distinct roles, while the wingers remained in more fixed roles with Anderton left and McManaman right. Scotland struggled to get real width high up the pitch:

If you enjoyed this look at Euro 1996 through a modern lens and want to learn more about how data can evaluate and describe football, you may enjoy our Introduction to Analytics course. Suitable for everyone from interested amateur right up to football professionals, it gives an accessible, fun and informative route into the world of data and football. Sign up here!

Euro 1996 relived through a modern lens. StatsBomb have collected Euro 1996 data and will be alongside England as this tournament progresses once again via ITV Sport.

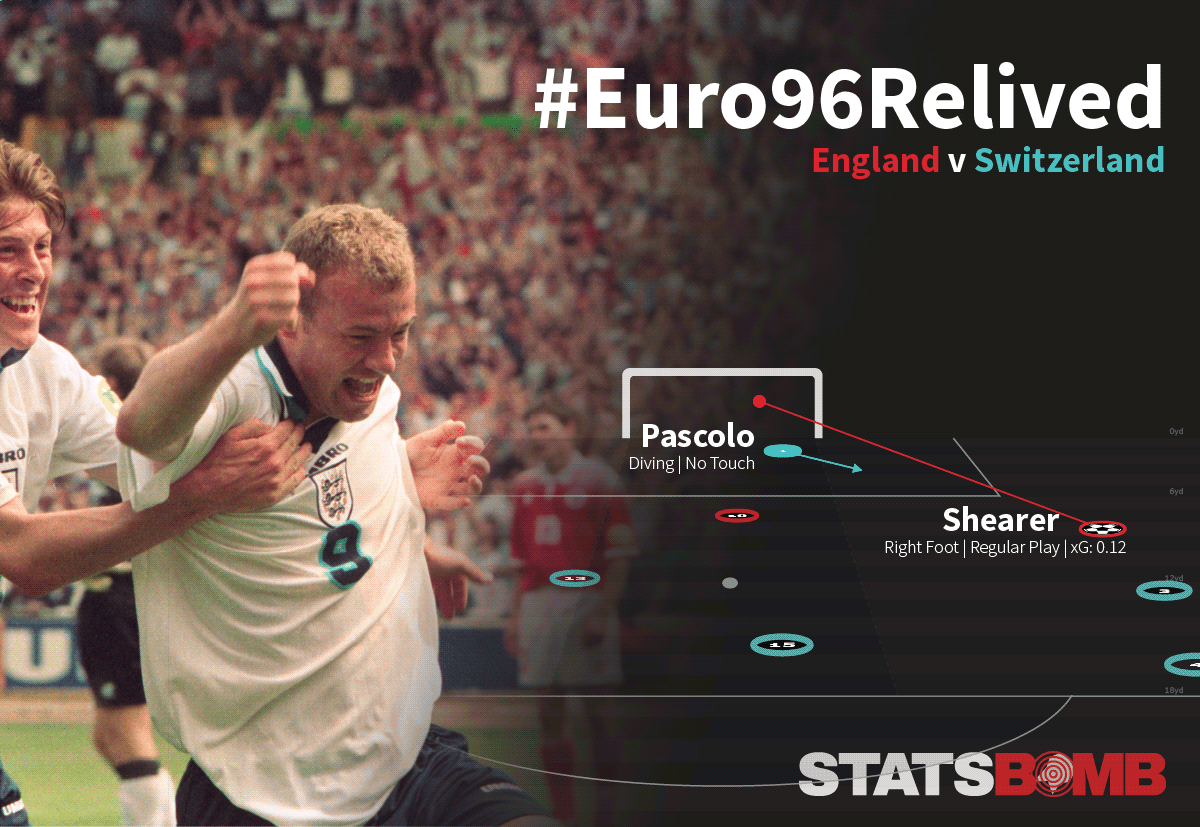

England got their Euro 1996 campaign started with an underwhelming 1-1 draw against Switzerland. Alan Shearer's thumping finish saw the hosts take a lead into half time, but they failed to create anything of note in the second half. The Swiss snatched a deserved draw late in the game after Kubilay Türkyilmaz dispatched a penalty given for a handball against Stuart Pearce.

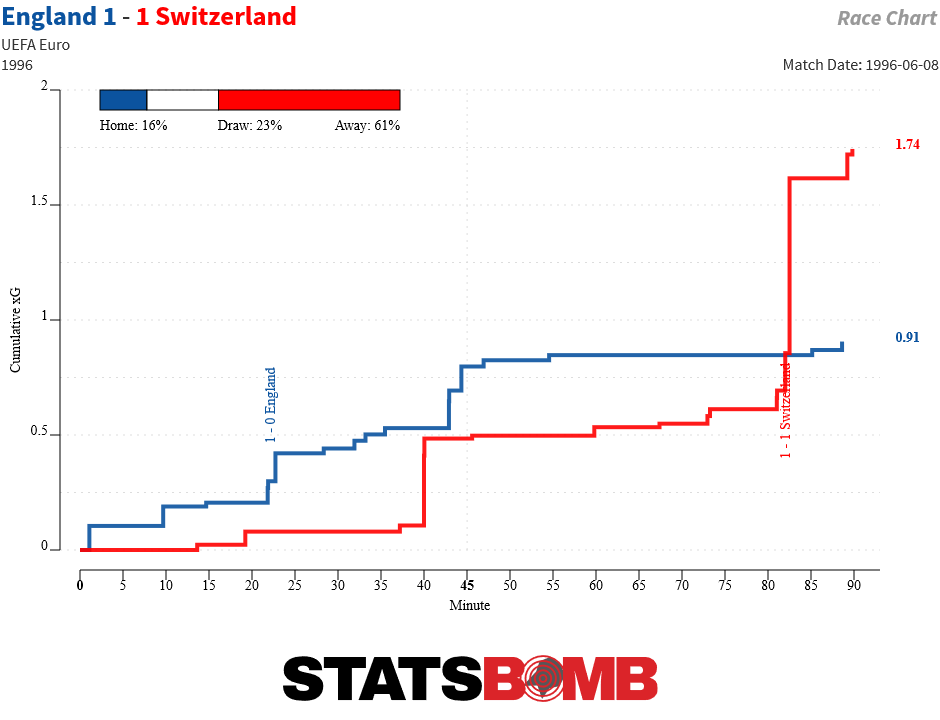

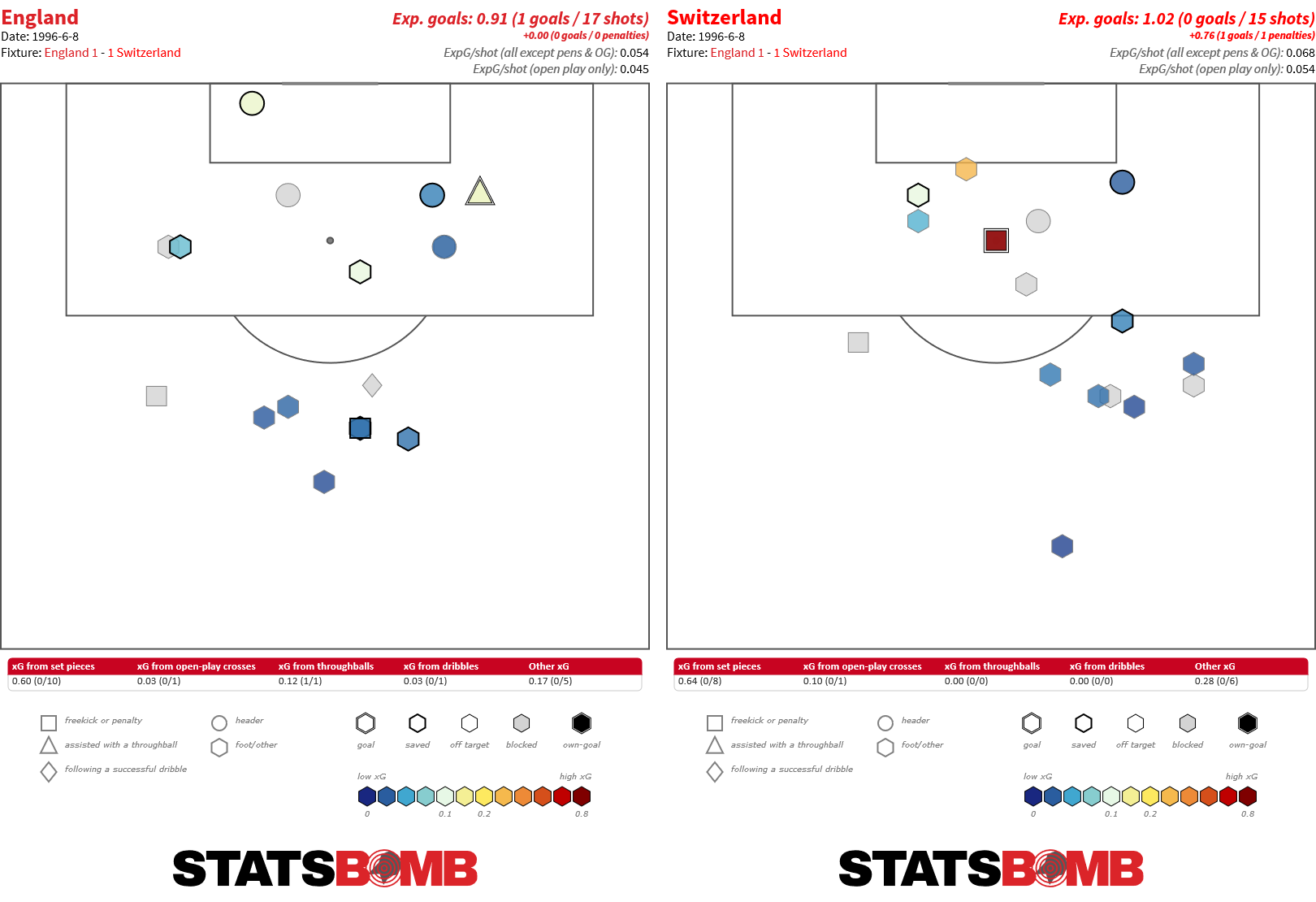

The penalty skewed the expected goals count towards the Swiss, but the game featured few high quality chances:

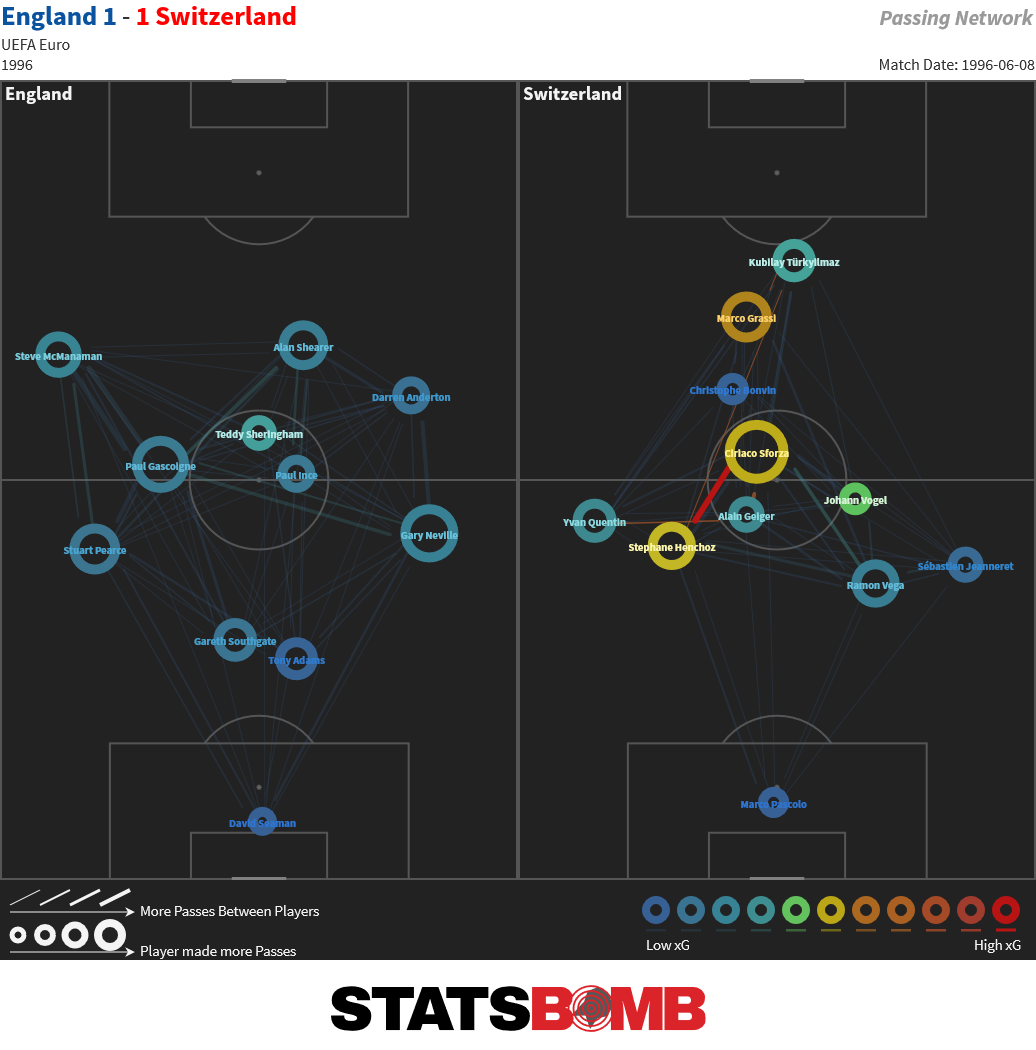

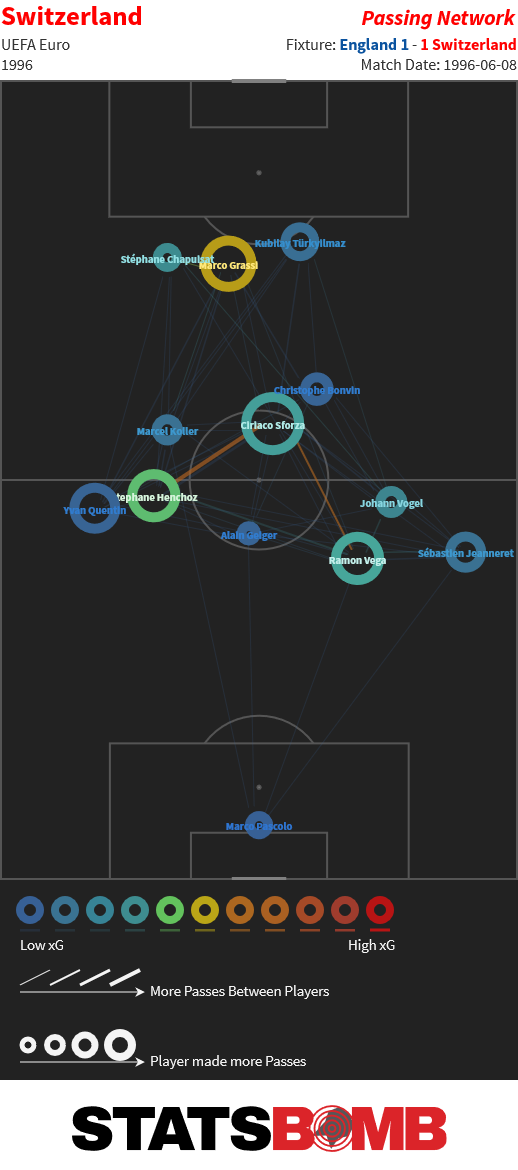

Via the pass network, England's formation resembled a 4-4-1-1 with wingers pushing high and Teddy Sheringham dropping off the front line to link play. For Switzerland it was more a game of two halves, with the second half seeing their front line push high up the pitch (substitutes included):

For England, Steve McManaman was a ready outlet in a disciplined role on the left flank and completed six of ten dribbles, reliably carrying the ball forward:

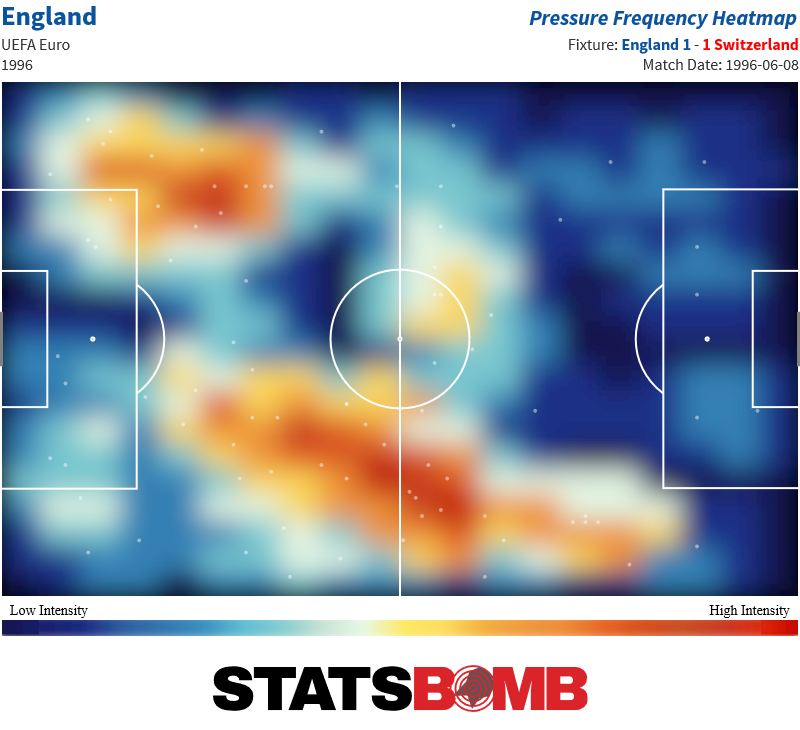

England manager Terry Venables noted his players tired as the match rolled on, and the shape of the game reflected that. England also recorded few pressure events throughout:

Paul Ince led the way with 13, Paul Gascoigne next with 10 while centre back Tony Adams hinted at the kind of front foot defending that he was renowned for with 9. For pass volume Ciriaco Sforza led the way for Switzerland with 55 attempted passes, 17 of which were in the final third, Gascoigne and the two English full backs saw the most of the ball for England, but neither side managed to contribute a good volume passes from open play into the box. Gascoigne had a limited influence on the game in the final third and was replaced in the 77th minute by David Platt. His main work was in buildup:

England face Scotland next with a win paramount to improve their chances of progressing.

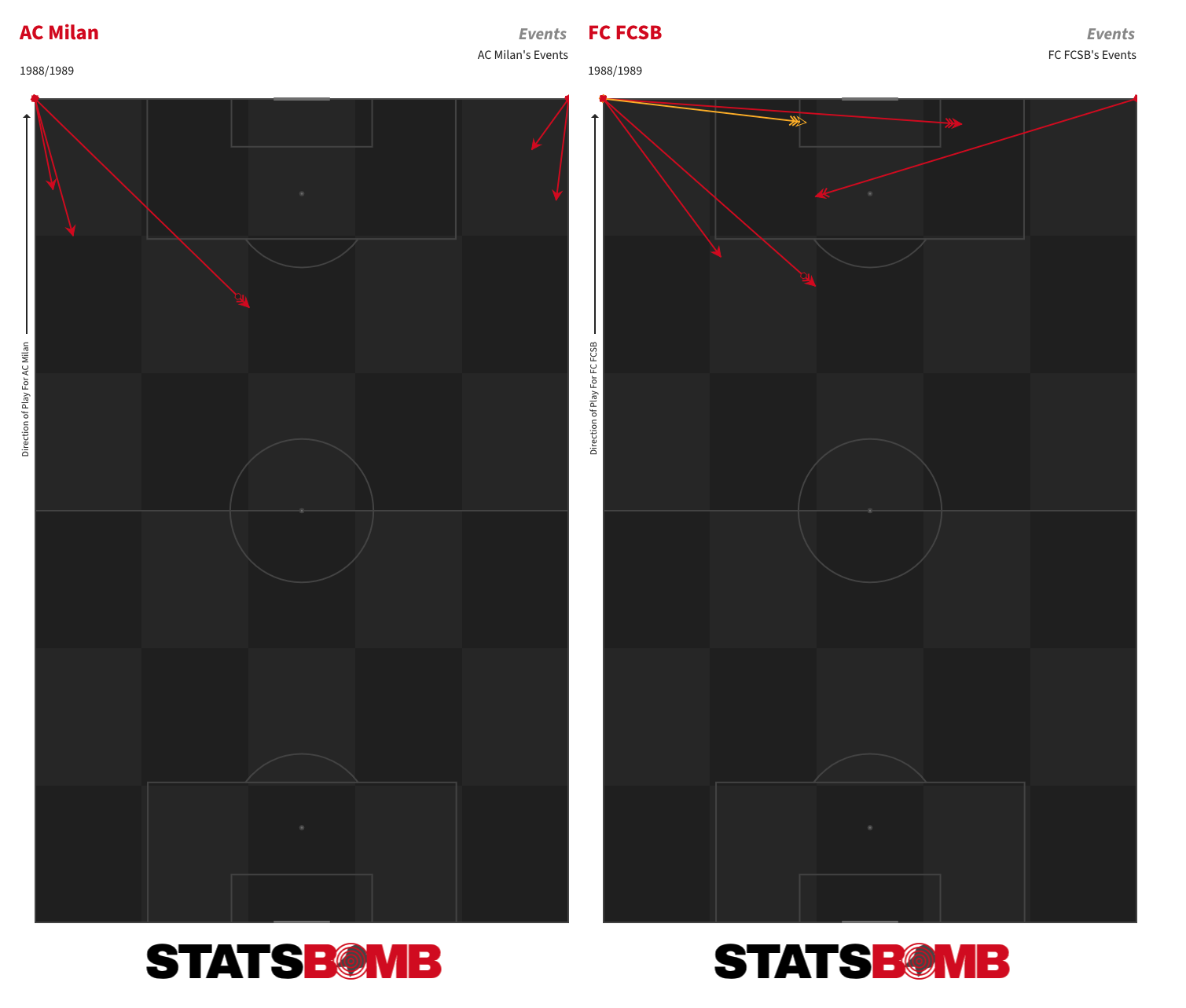

Next up on our journey through the history of the European Cup is the 1989 final between AC Milan and Steaua Bucharest.

In front of a largely partisan crowd at the Camp Nou in Barcelona, Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan secured the first of their two consecutive triumphs. In the first part of the series, we covered the dominant Real Madrid side of the early years of the competition in the context of their victory over Eintracht Frankfurt in 1960; last time out, we looked at a clash of styles in the 1972 final between Ajax and Inter Milan.

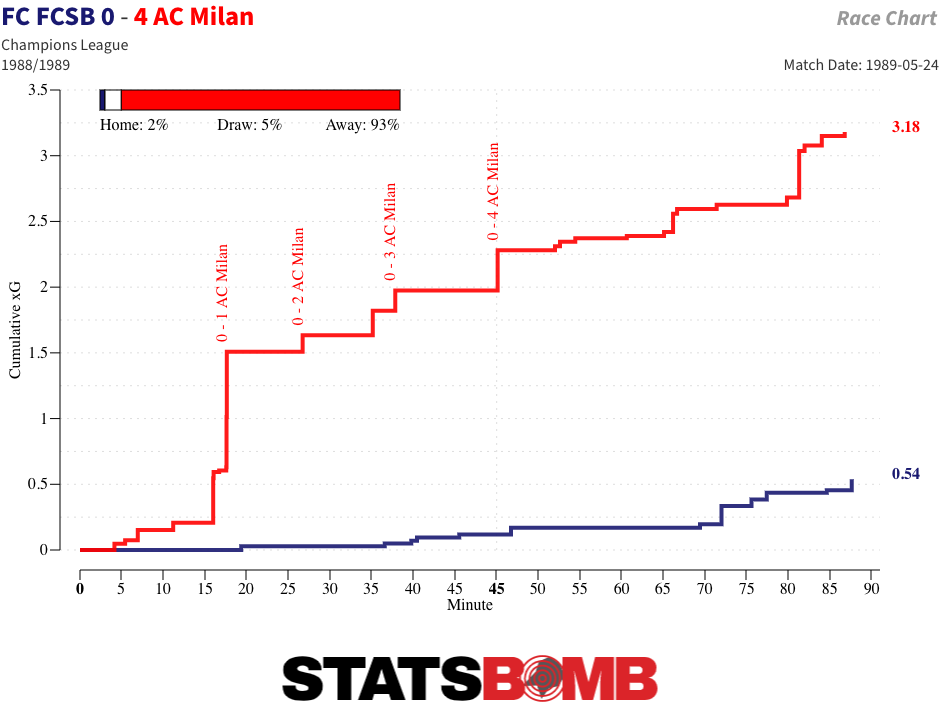

After three consecutive victories for that Ajax side followed by three for Bayern Munich, English teams then dominated the competition, winning it six times in a row between 1977 and 1982 and seven times in eight, including four for Liverpool, if that end date is extended to 1984. But in the five years prior to the 1989 final, from the last of Liverpool’s wins through to PSV Eindhoven’s triumph in 1988, teams from five different countries lifted the trophy. Milan Dominance This match didn’t last long as a genuine contest. Milan had already opened the scoring and taken 10 shots before Steaua even mustered their first attempt. By half-time, Milan had added two more goals. A fourth arrived in the opening minute of the second half.

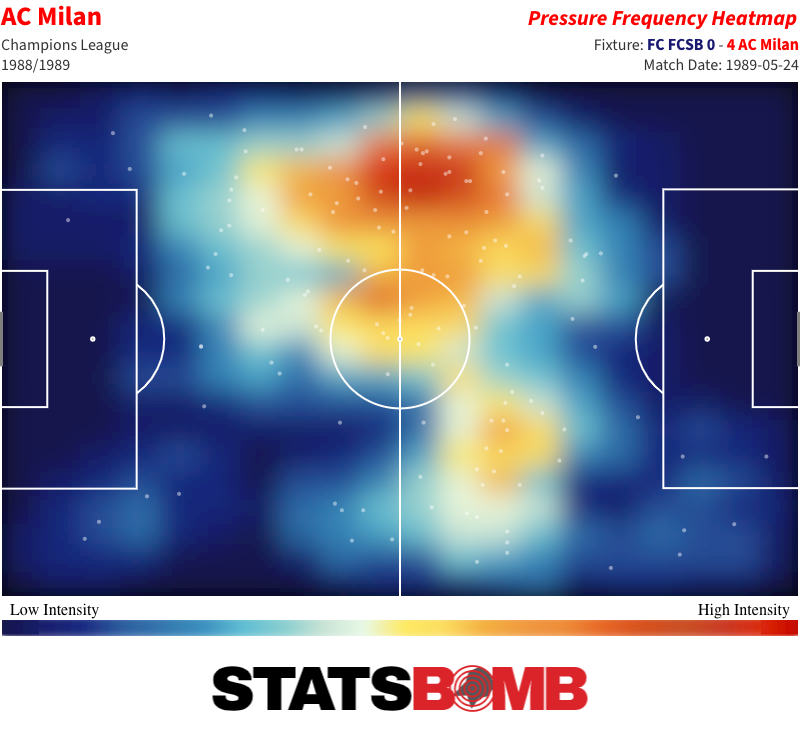

Milan pressed high -- their average defensive action was performed further away from their own goal than the average of any team in last season’s competition -- and kept Steaua at arms length. Their pressure heat map shows a distinct tilt towards the defensive left, primarily because Steaua consistently sought to work the ball out of defence to that side.

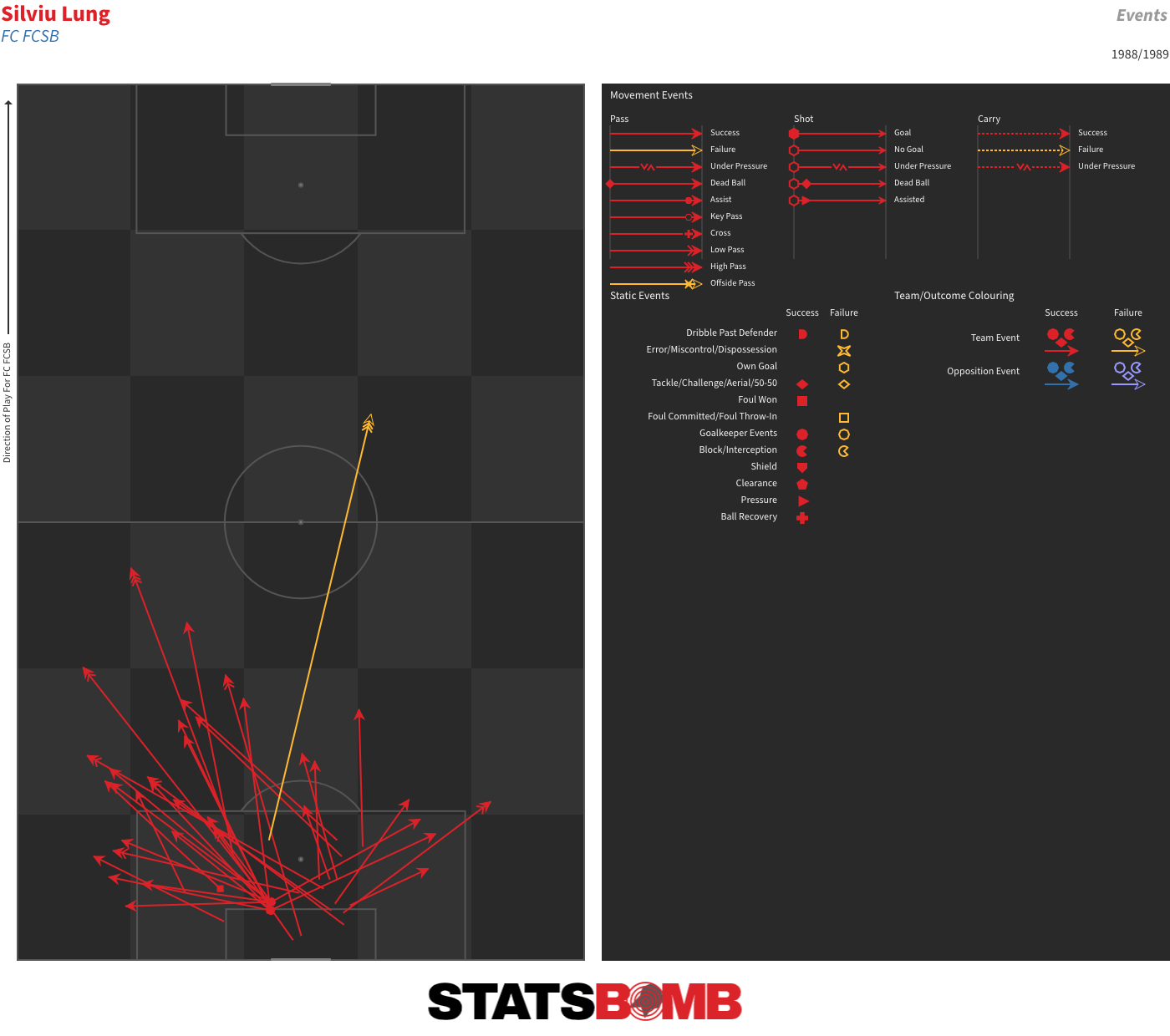

This was a very good Steaua team. They had averaged 2.75 goals per match on their way to the final, had reached the semi-finals a year earlier and were only three years removed from lifting the trophy in 1986. They had just wrapped up the fifth of five consecutive Romanian league titles, the latter three achieved without losing a single game. In that time, they put together a 104-match unbeaten run that remains a European club record. In this match, Steaua consistently tried to play out short from the back. Silviu Lung’s average pass length of 24.81 metres was far shorter than that of any goalkeeper in last season’s competition.

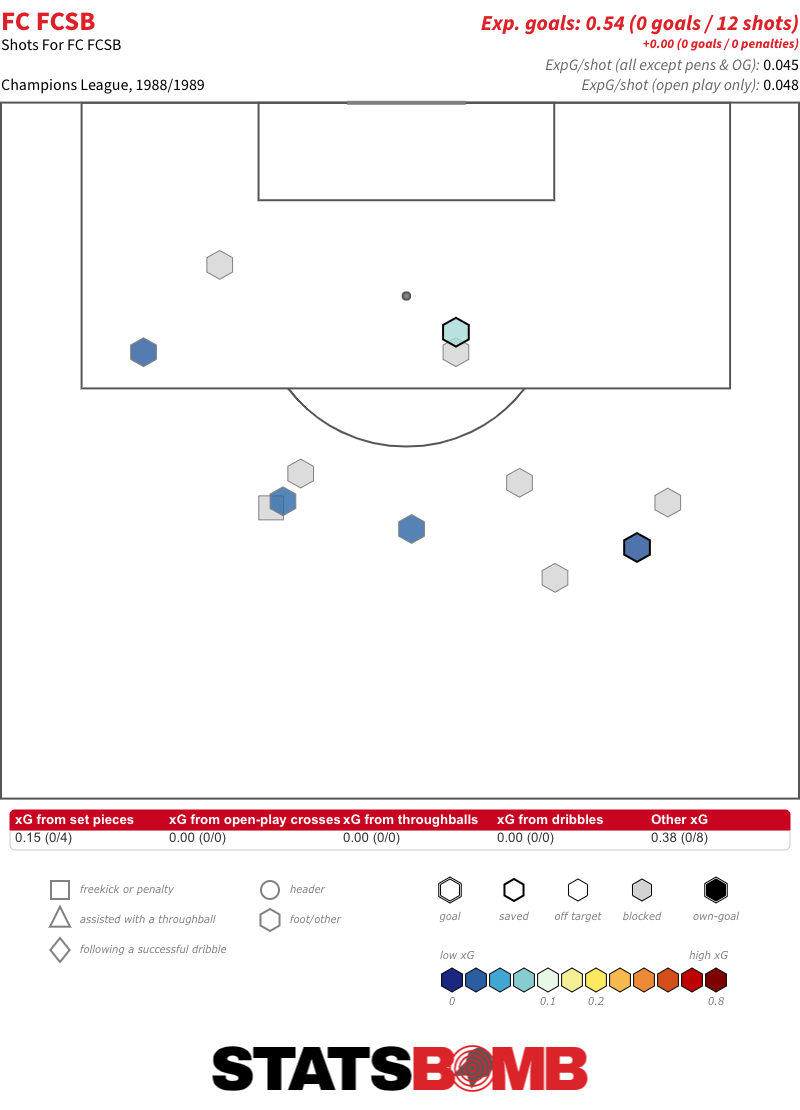

There were glimpses of their quality in some of the sequences in which they were able to work the ball around the Milan press and advance. Captain Tudorel Stoica showed himself to be a calm head under pressure. But they were unable to establish any sort of regular presence in attacking areas against a compact Milan side with a legendary defensive four of Mauro Tassotti, Alessandro Costacurta, Franco Baresi and Paolo Maldini. Only four of Steaua’s 12 shots were from in and around the area, and the best chance they created was a blocked 0.14 xG opportunity when the game was already long lost.

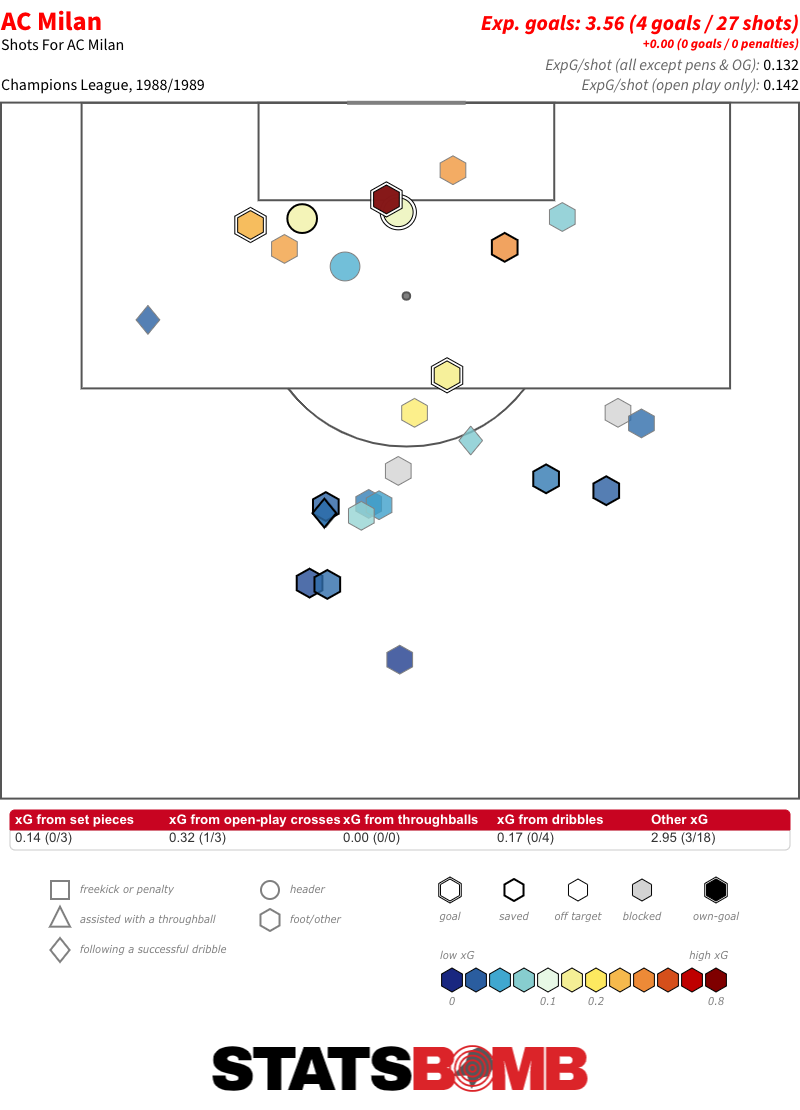

It is interesting to note that the two teams completed exactly the same number of passes (401) over the course of the 90 minutes. The difference lay in what they were able to do with them. While Steaua struggled to penetrate, Milan’s attacks were rapid and incisive. Fifteen of their 27 efforts on goal came directly after winning the ball back in opposition territory. Four or five is considered a lot these days. They created a good volume of high-quality shots.

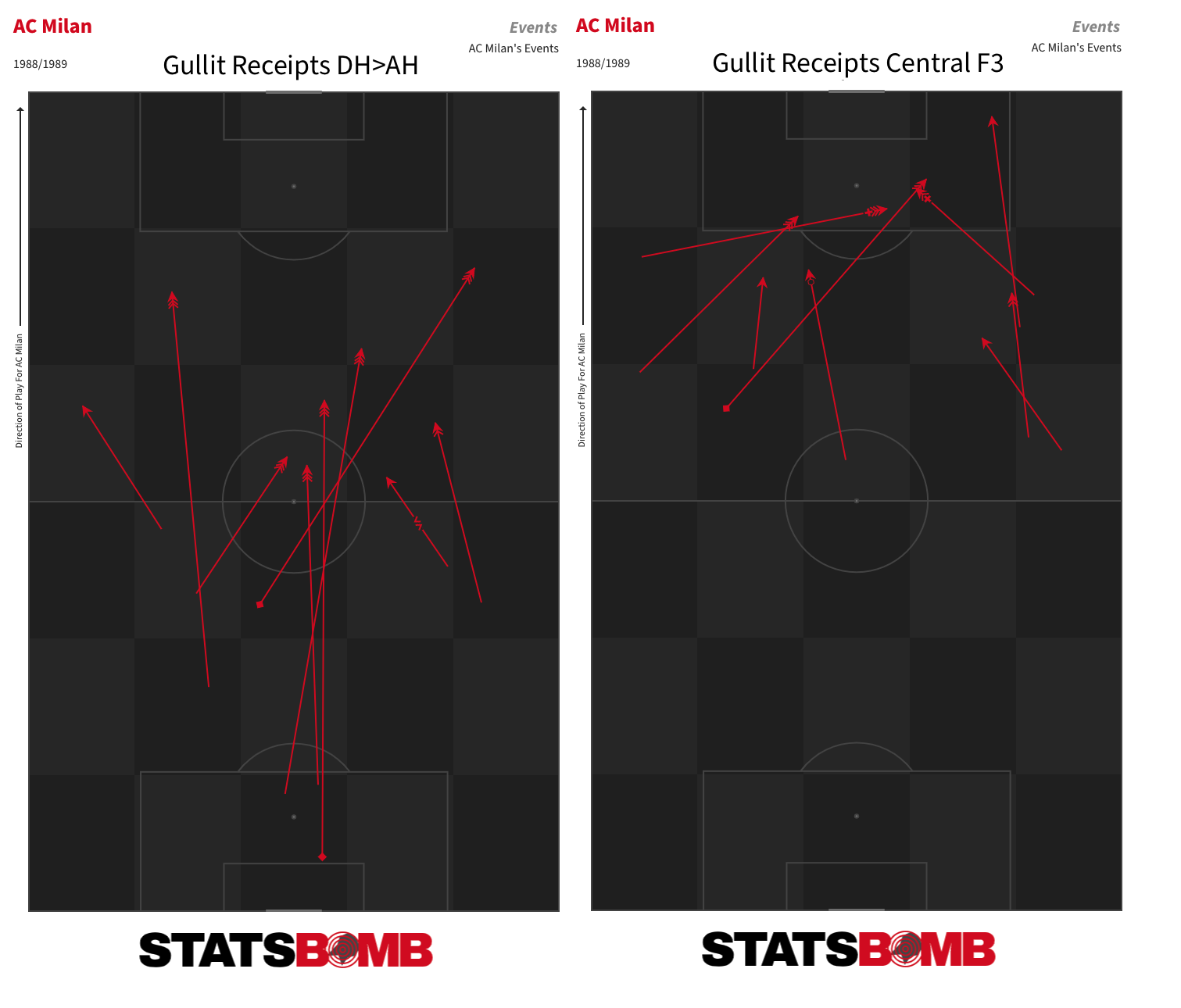

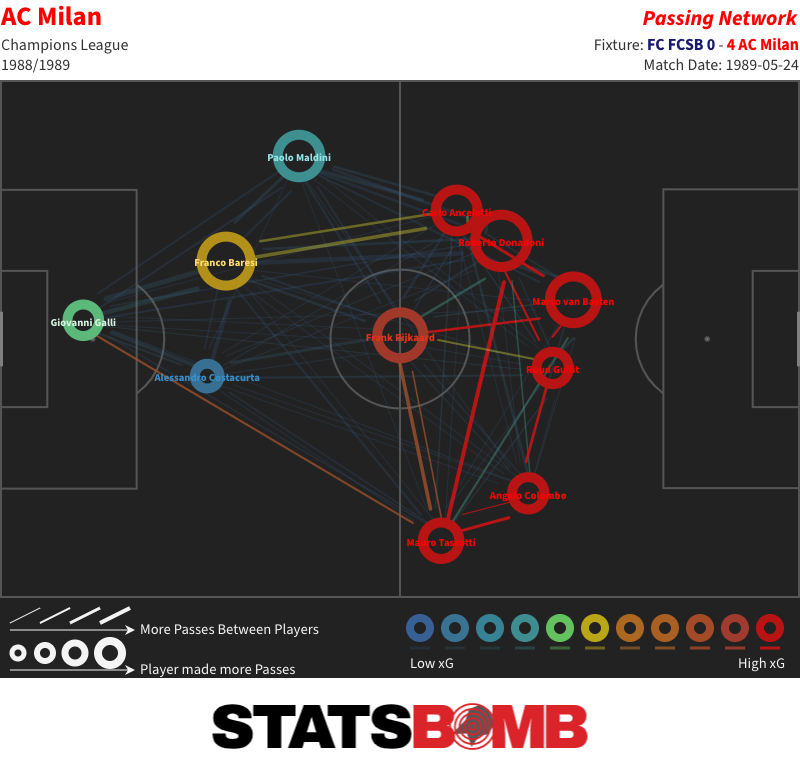

Two goals apiece from Marco van Basten and Ruud Gullit -- alongside Frank Rijkaard, the trio of Dutch internationals who helped power the side to their successes in this era -- won Milan the trophy. Gullit the Reference Point Milan were relatively direct in their use of the ball, with Gullit the primary reference point when advancing from the defensive half into opposition territory, and from there into central zones inside the final third.

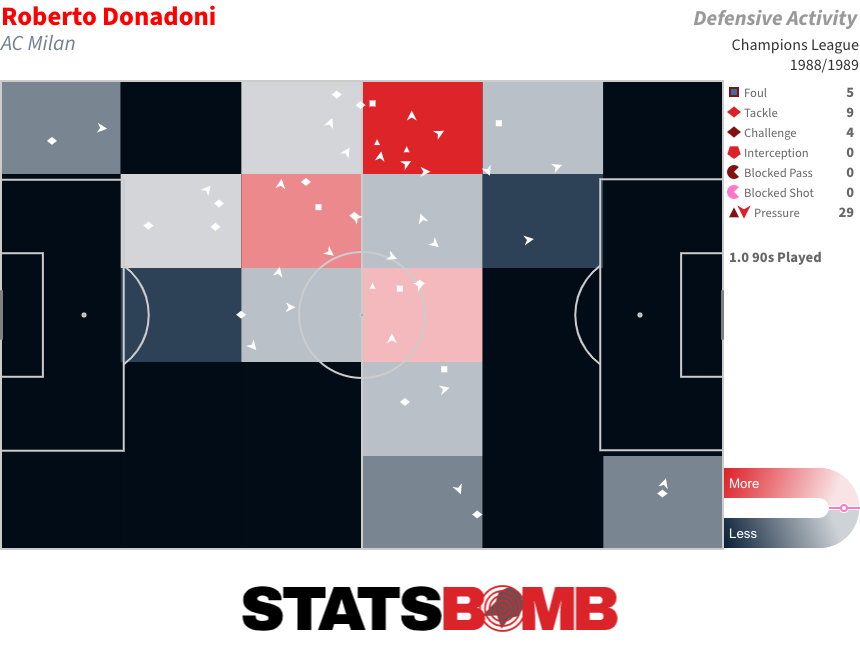

Gullit had a couple of inches on both of Steaua’s central defenders, and successfully received 11 head-height passes from teammates. Given the range of his abilities, he was far from a typical target-man, but he was certainly capable of fulfilling aspects of that role for his side. Donadoni and the Milan 4-4-2 Sacchi is famous for his use of a 4-4-2 formation, but this was far from a flat or boxy version of that alignment. For one, there was clear asymmetry amongst the two full-backs. Maldini largely hung back, while Tassotti advanced much higher down the right.

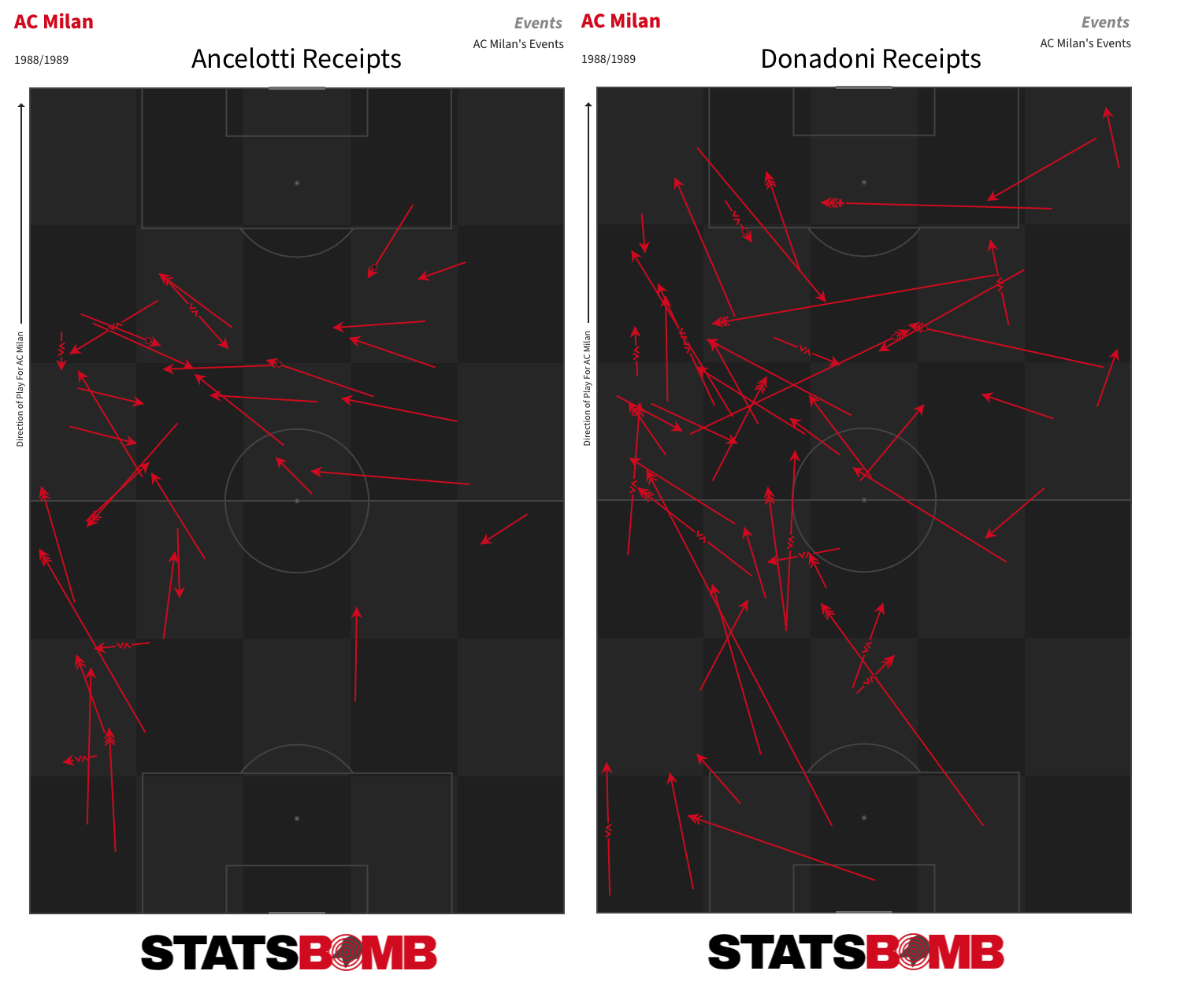

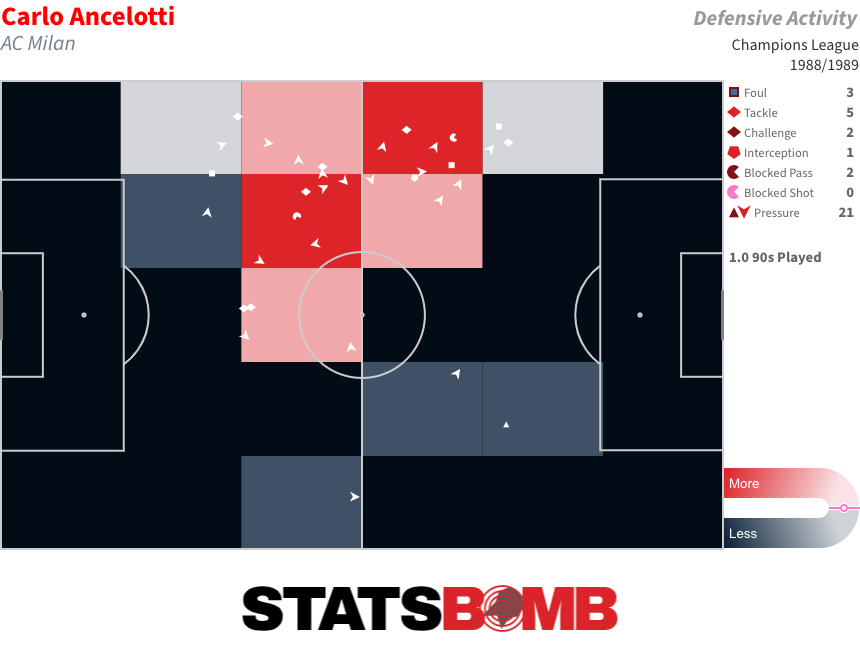

Interest was also provided by the positioning of Carlo Ancelotti and Roberto Donadoni, who overlapped a great deal from their respective nominal starting positions of central and left midfield. Their receipt maps show that they both spent a good amount of time in both wide and central areas, although it was Donadoni who more often joined up with the two forwards.

They also did much of their defensive work in similar areas, although Ancelotti did generally appear to be the wider positioned of the pair out of possession.

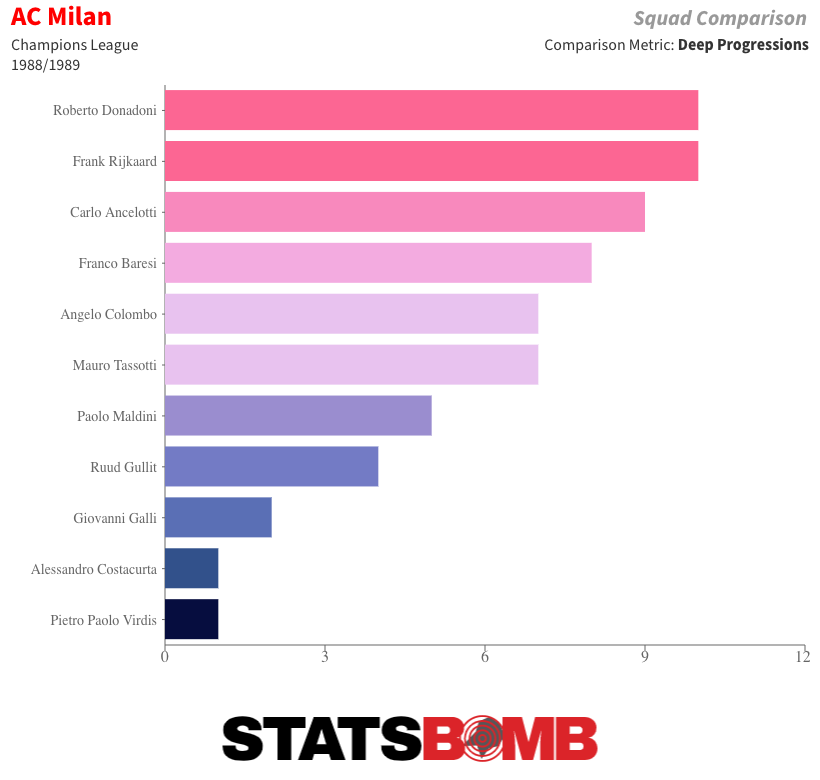

Donadoni may not have been the flashiest player, but he was an invaluable one. He got through a ton of work on both sides of the ball in this match. In defence, he led the team in pressures and tackles (including a couple of very nicely timed sliding ones); in attack, he set up seven chances, three more than any of his teammates, while he and Rijkaard were the two players who most often moved the ball into the final third.

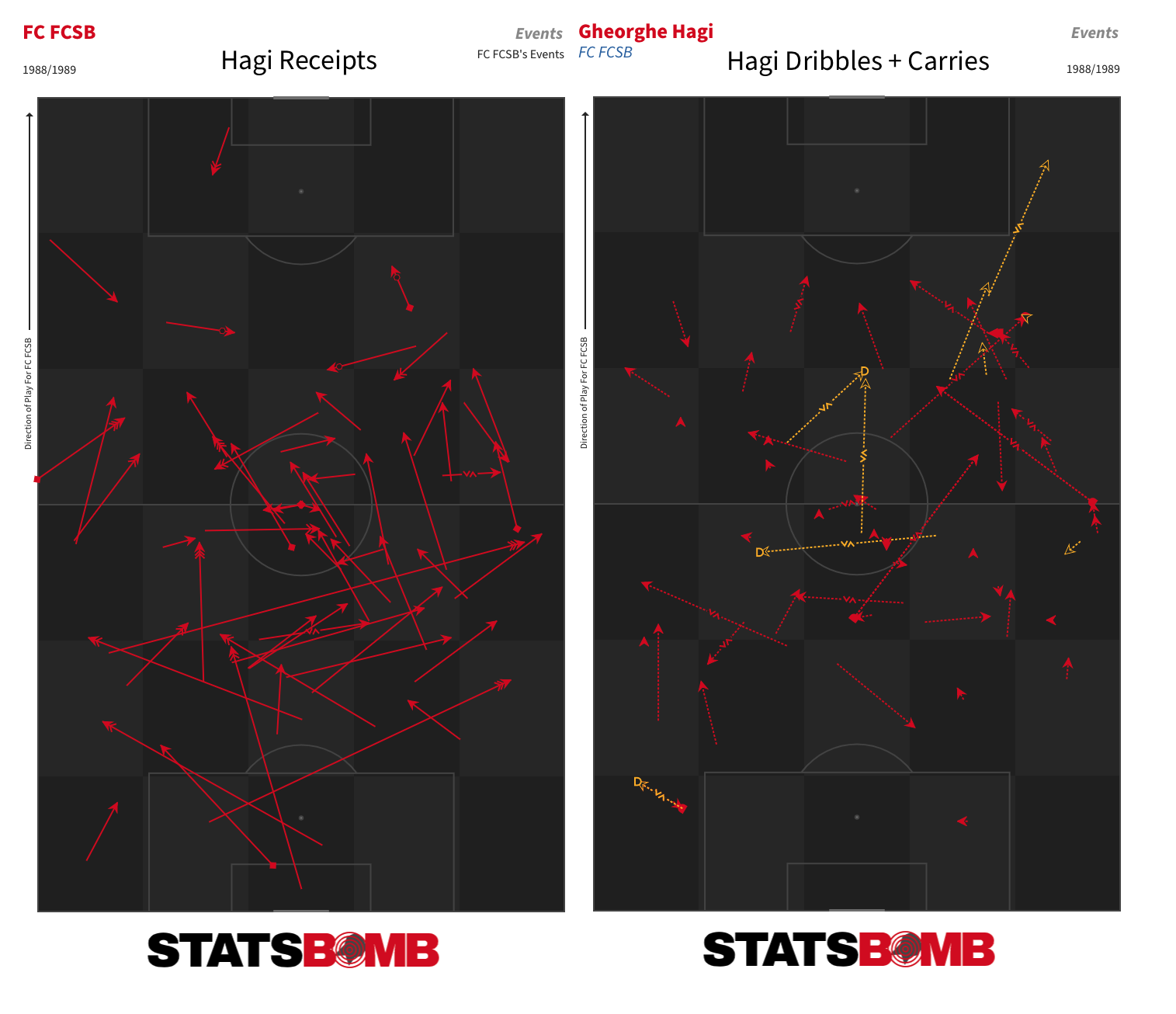

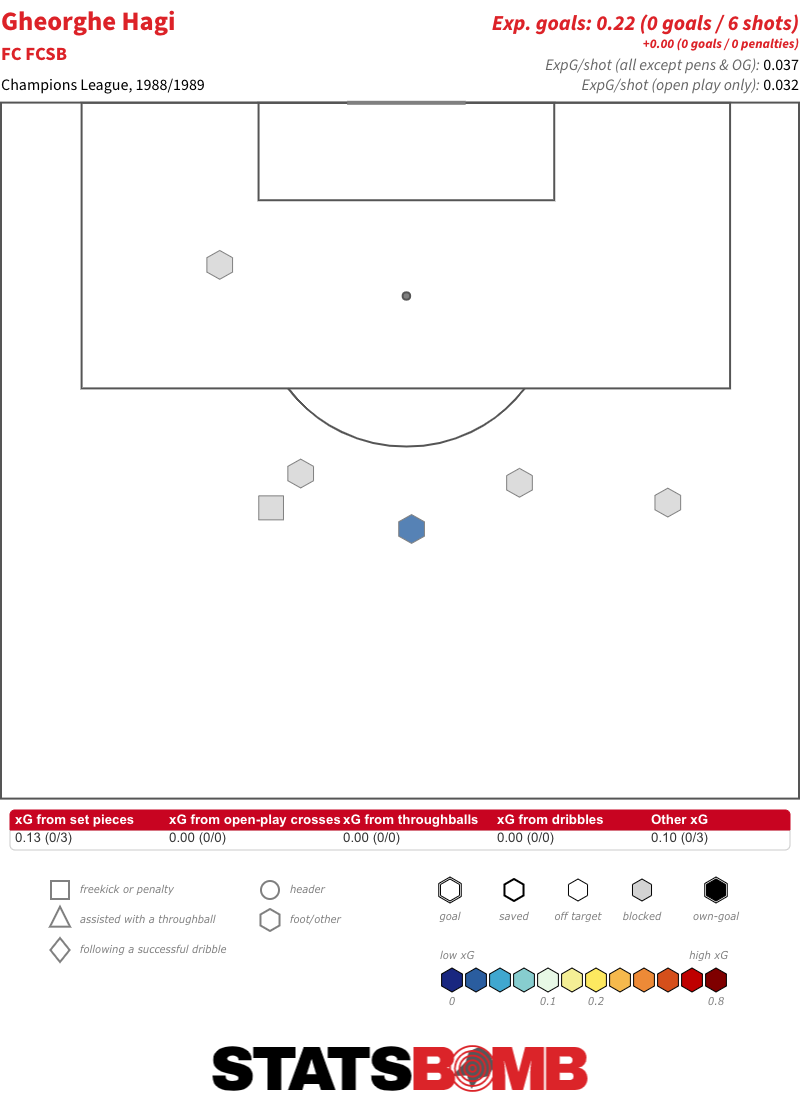

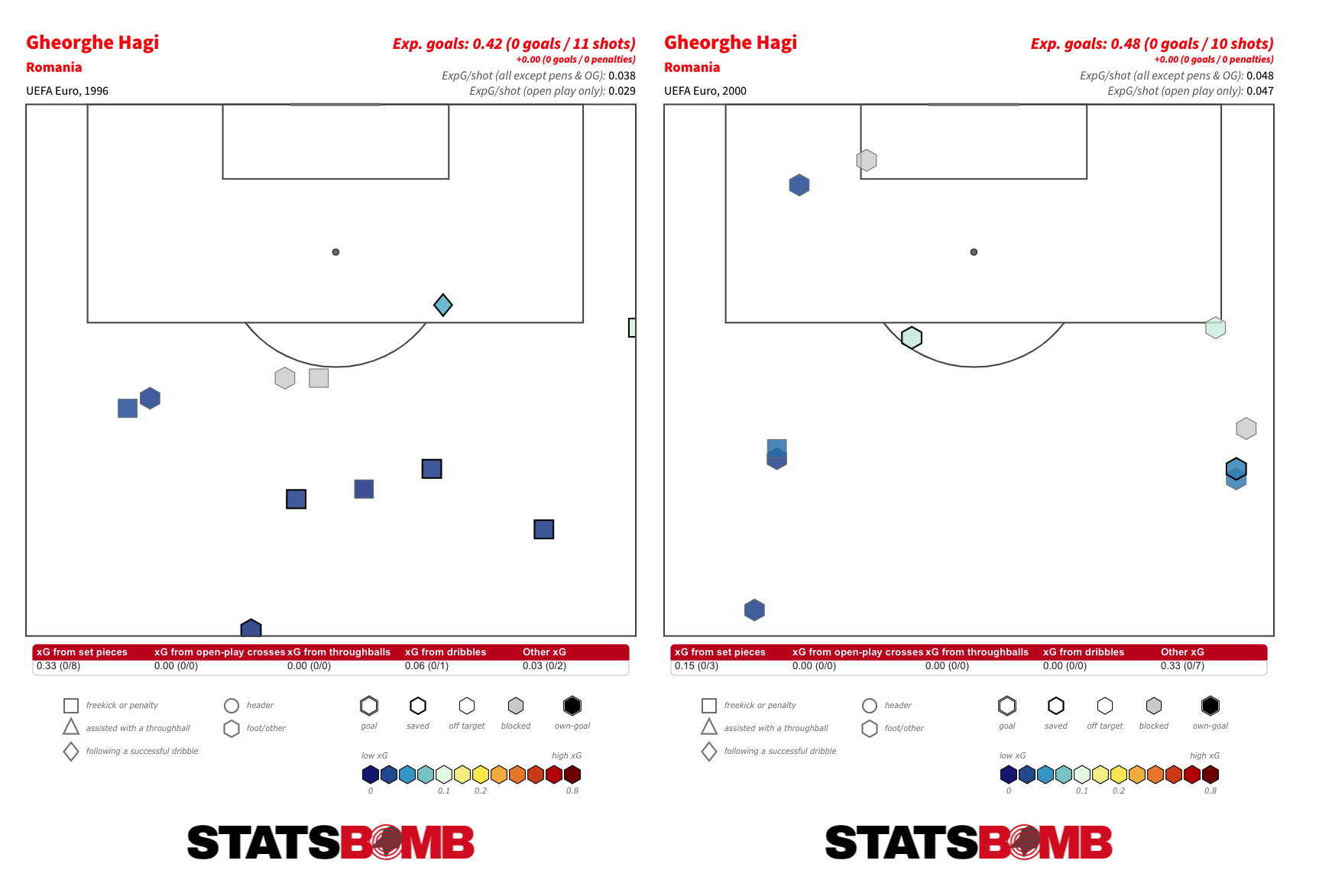

Hagi Gheorghe Hagi was the most recognisable name on the Steaua team sheet, and with the number 10 on his back, the one expected to carry the majority of the creative burden. Yet he struggled to effect the game. He dropped back into deeper areas to help advance the ball forward, primarily off dribbles and carries:

But he produced very little end product inside the final third. He didn’t set up a single chance for a teammate, and though he led his team in shots, they were all of low quality.

Hagi’s spectacular strikes in the saturated sunshine of USA 94’ are an enduring childhood memory, but it must be noted that they were the result of a consistently optimistic long-range shooter.

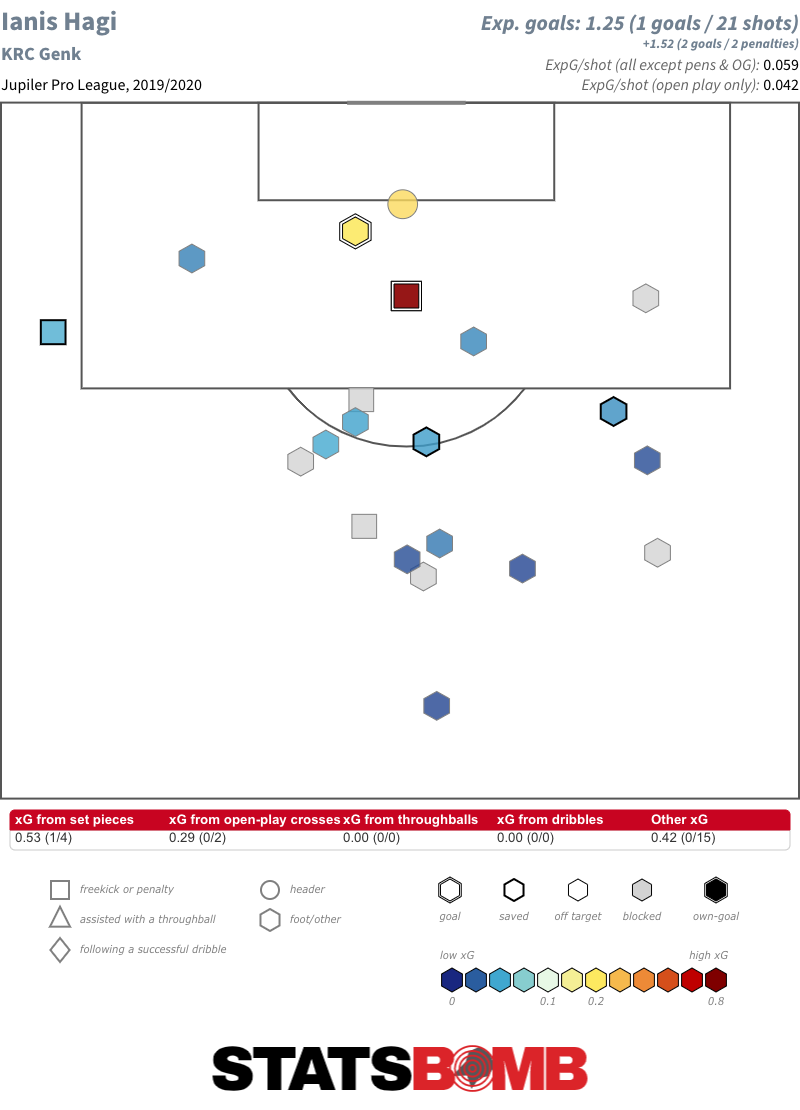

Nowadays that is normally coached out of a player, though not always. Check out his son, Ianis Hagi, now of Rangers. The fruit clearly doesn’t fall from the tree.

Corner Variations The previous two finals in this series featured just six short corners between them, and even then, one of Ajax’s two in the 1972 final was simply to keep the ball and run down the clock in second-half stoppage time. Most corners across those two matches were simply swung into the area. There was more variation in this match. Only two of the 10 corners (five apiece) were high deliveries into the area. Milan had twice scored from short corner routines in their 5-0 destruction of Real Madrid in the second leg of their semi-final and again went short in the final. Steaua, meanwhile, had one interesting routine that didn’t quite come off when a low delivery from the right was laid off just outside the ideal path of an incoming player.

Dribble Volume Remains High Just as in the previous two finals we’ve covered, the dribble count in this match was huge by modern standards. There was a slight reduction between 1960 and 1972, and there is again here, to 46 attempted and 29 completed, but it’s still far above the contemporary average.

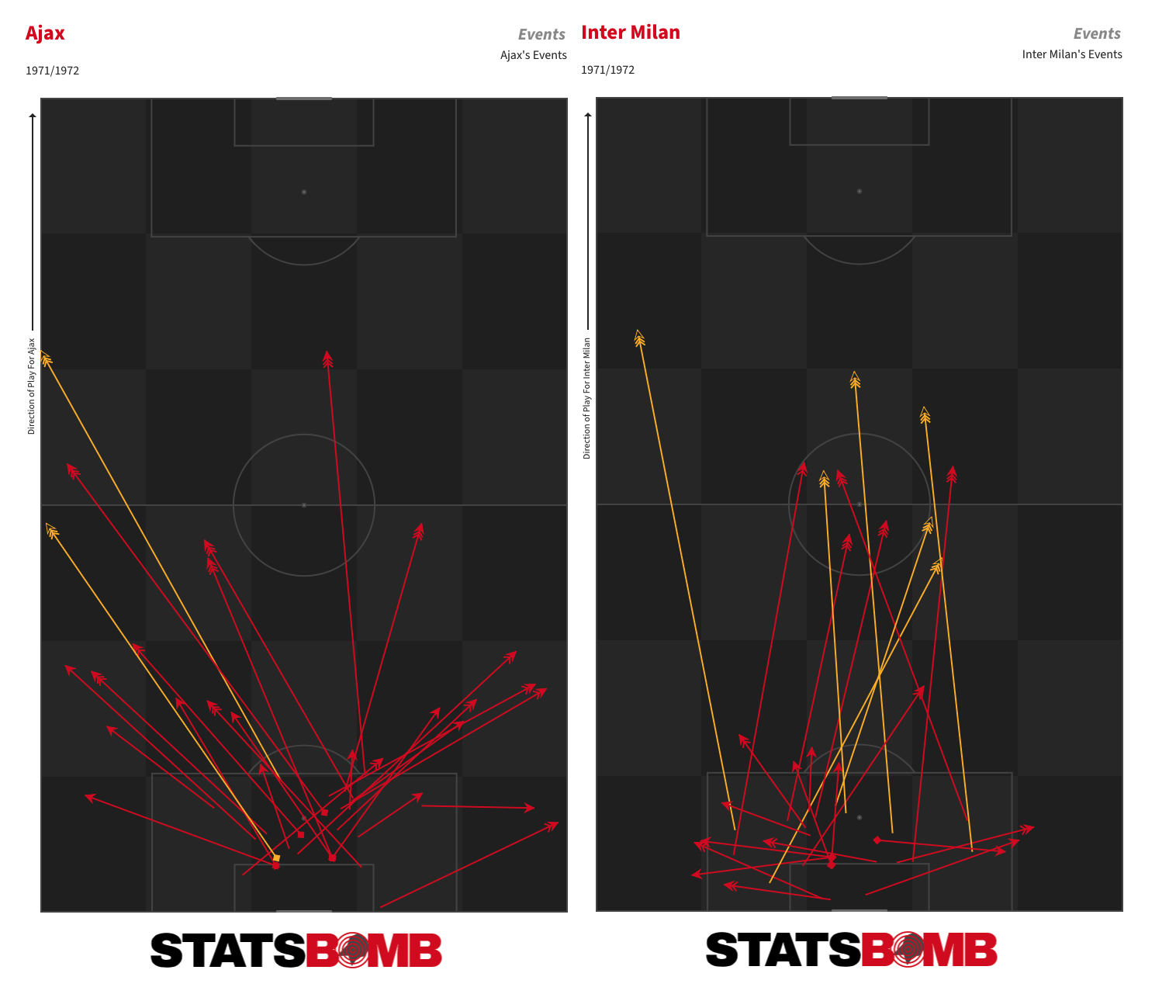

We continue our series on the history of the European Cup with a look at the 1972 final between Ajax and Inter Milan. Last week, we covered Real Madrid’s victory over Eintracht Frankfurt in 1960; over a decade on, much has changed.

Ajax are the competition holders following their success over Panathinaikos at Wembley in 1971, while Inter, two-time winners in the mid-1960s, are back in the tournament for the first time since their loss to Celtic in the final of 1967. Ajax’s 2-0 win here would be followed by a third consecutive triumph against Juventus in 1973.

The Ajax Revolution

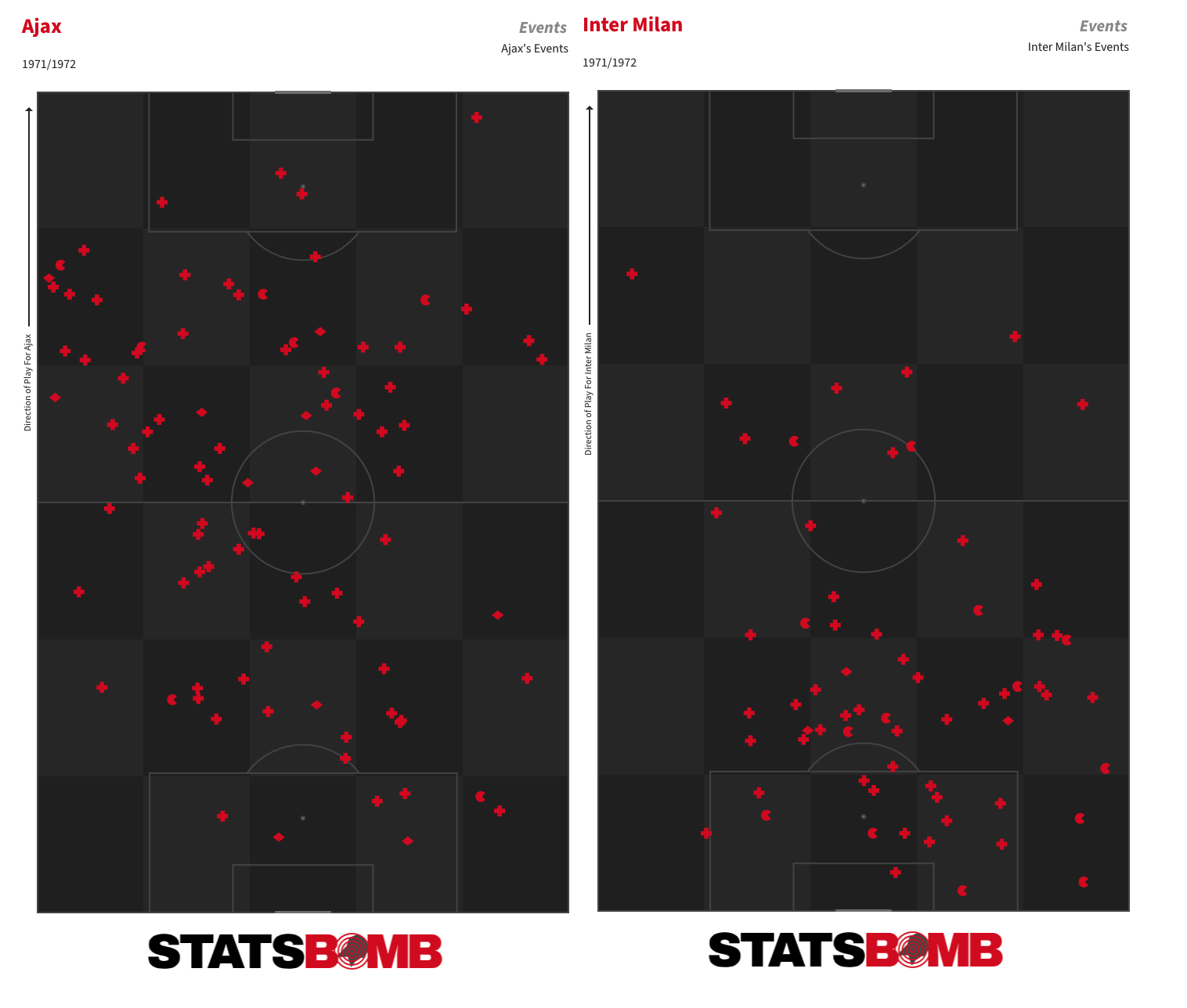

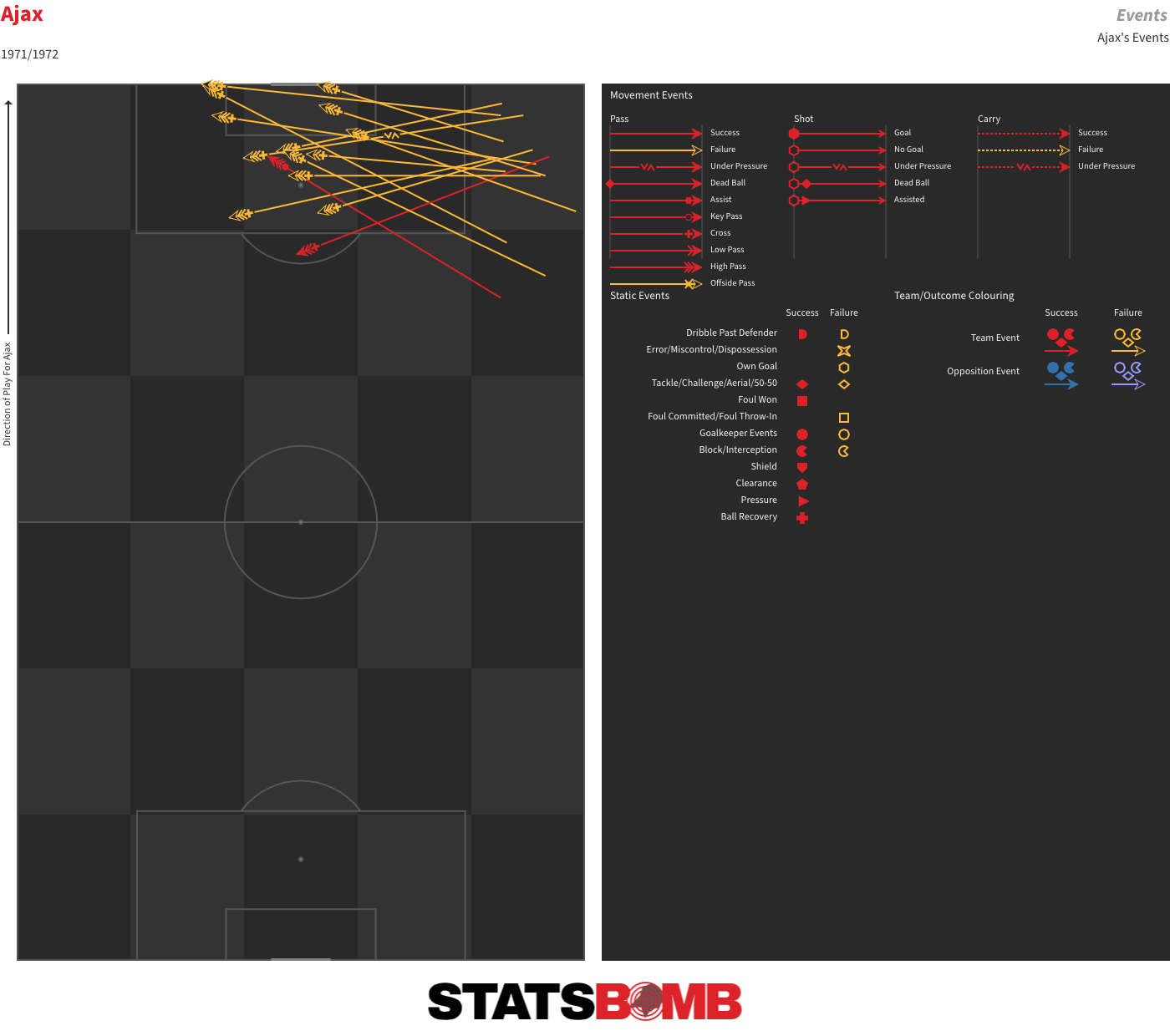

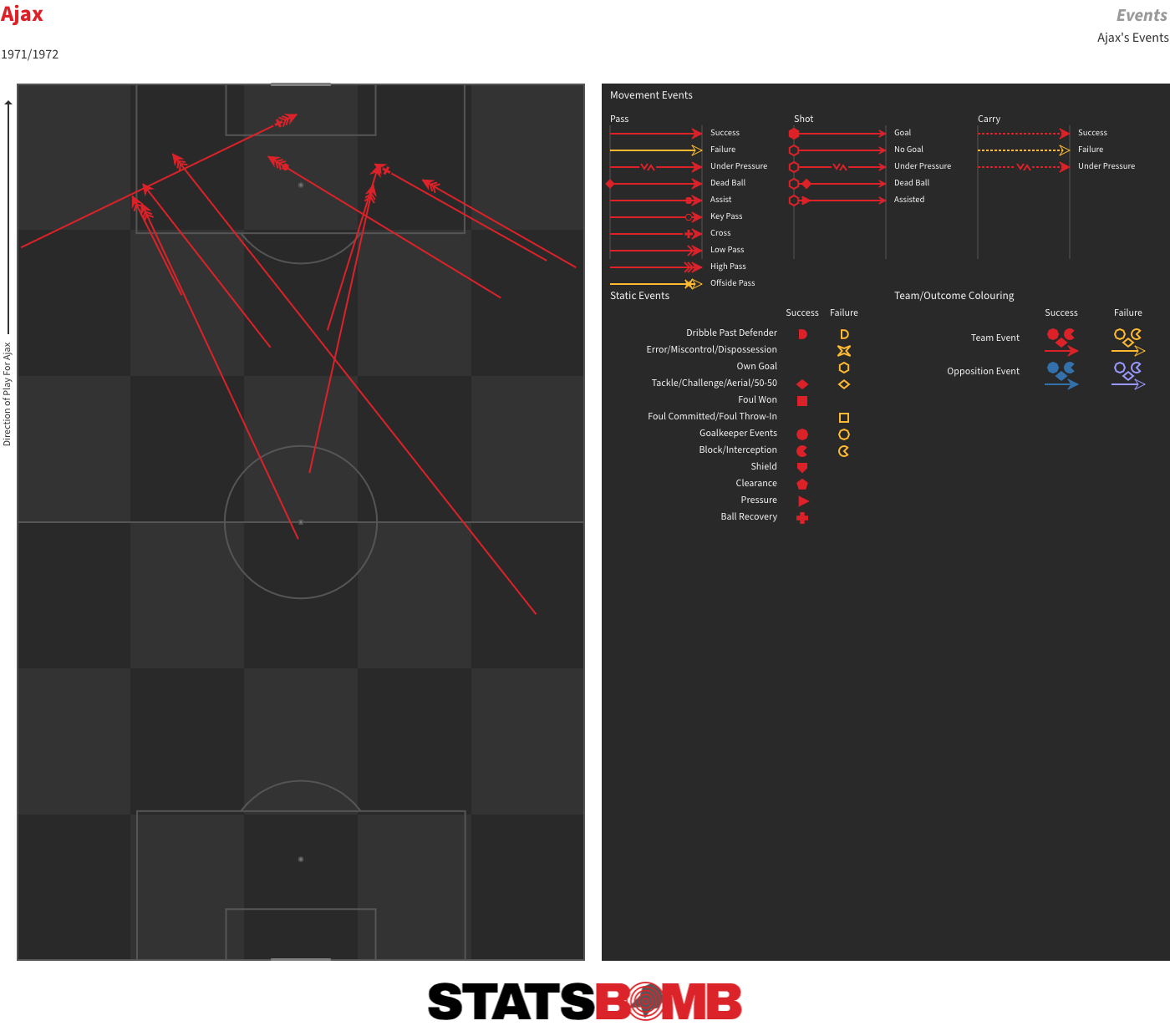

This match immediately feels more akin to the modern game than the 1960 final did. The formations are familiar: a 4-3-3 for Ajax and a 4-4-1-1/4-2-3-1 for Inter. Ajax are using squad numbers. Passing completion rates are up, there are less long balls, longer spells of possession and more attempts at collective play. The distribution of the two goalkeepers looks much more like that of their contemporary equivalents:

This Ajax side were the early prototype for the press and possess football of today. They regularly contested possession in opposition territory and when the ball was won, moved forward swiftly into shooting positions. The rhythm at which they played and their positional flexibility were unlike anything seen before, although it must be noted that Carlos Peucelle would later argue that River Plate’s La Máquina side of the 1940s were the first template for this style of play. There is some evidence that Rinus Michels, the Ajax coach who got the Total Football bandwagon rolling, was inspired by watching a Millonarios side that featured Adolfo Pedernera, the hub of that River team. It would, though, be fair to say that Ajax and the Dutch national team were its first proponents in a widely televised era.

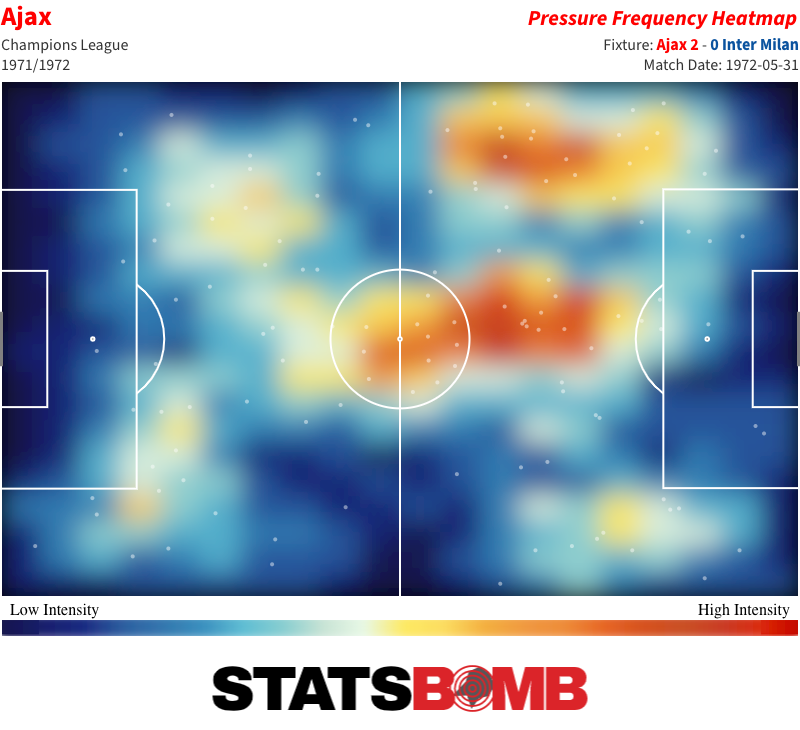

Ajax’s press in this match isn’t quite as aggressive and chaotic as that of the Netherlands at the 1974 World Cup, but they are still quick to close down, and they also step up swiftly to force offsides. When they lose the ball, it doesn’t usually take them long to regain it. They established clear territorial dominance, particularly during a first half in which Inter were penned in. The difference in the locations in which the two teams retrieved possession is striking:

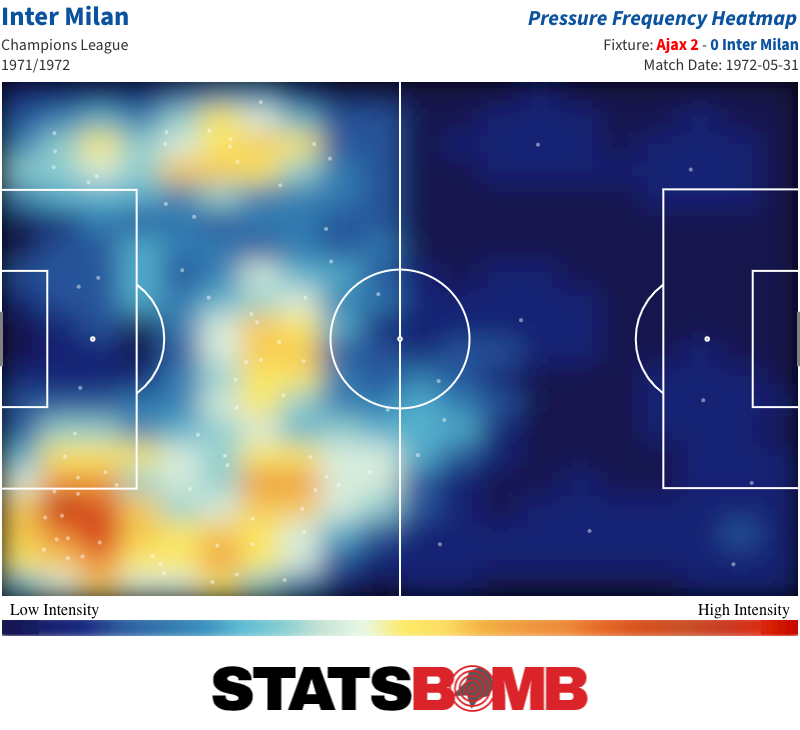

As are the match-long heatmaps of their pressure locations:

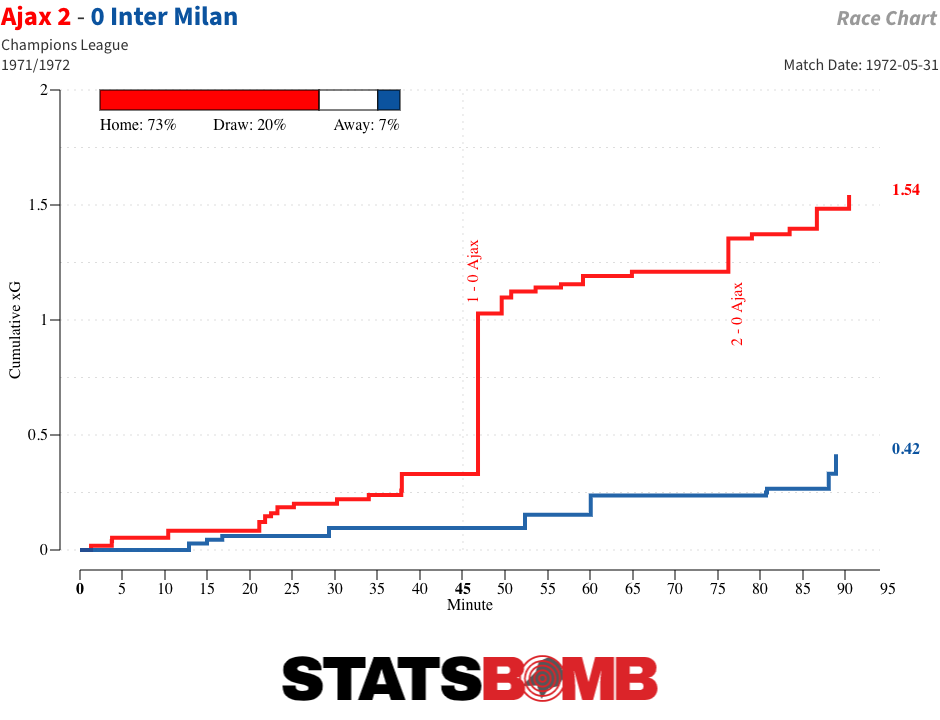

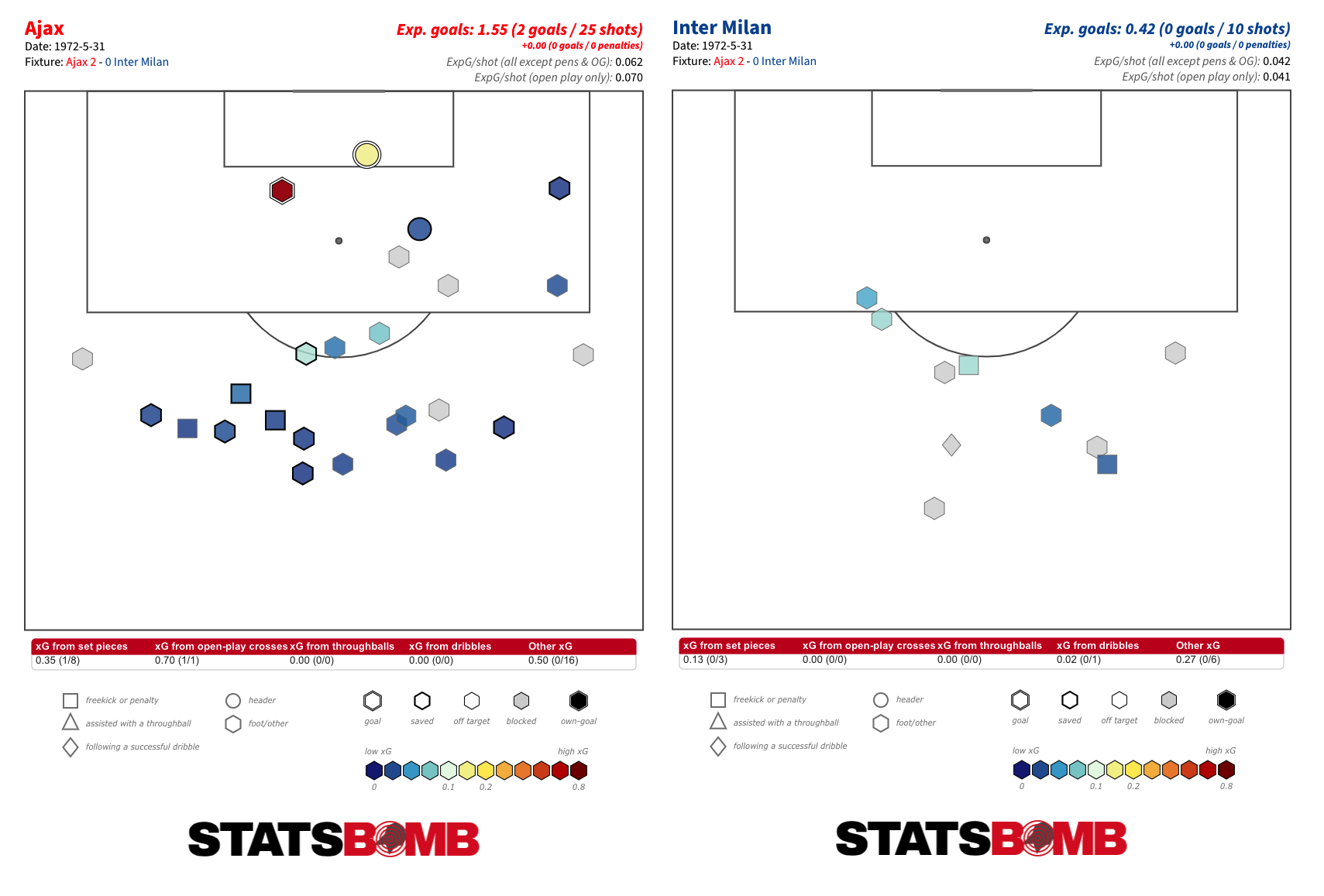

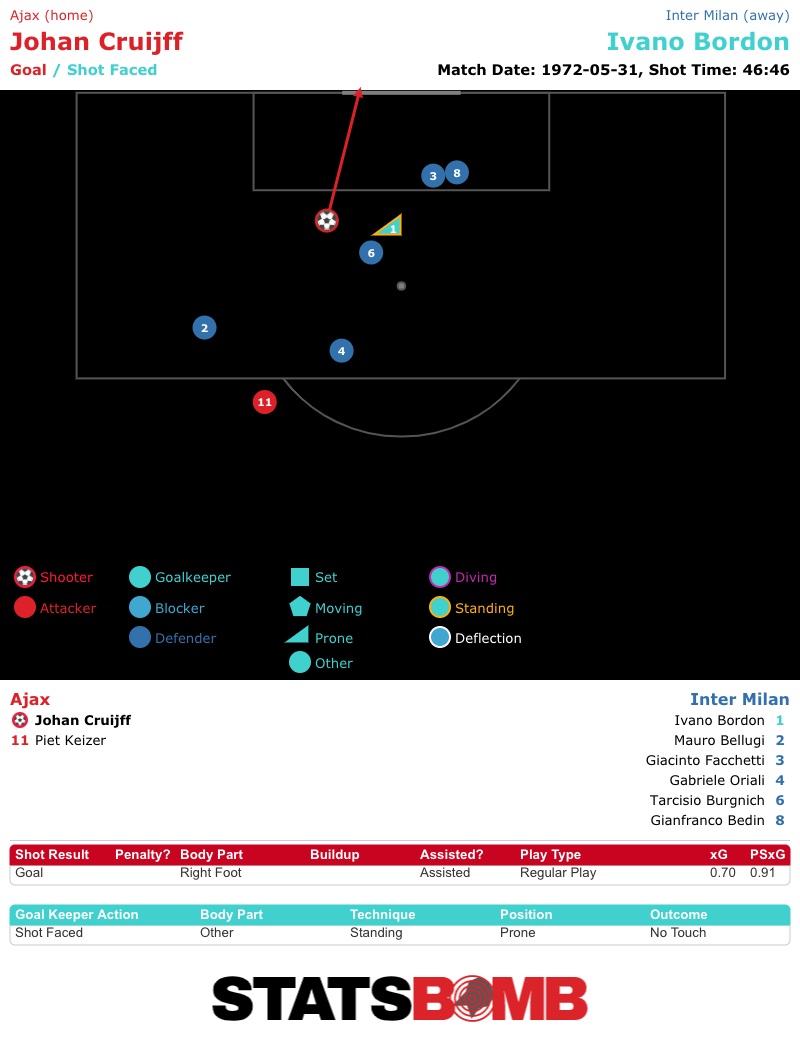

Overall, Ajax dominated in terms of territory, possession, shots and expected goals (xG). Two goals from Johan Cruyff, the second a header from a left-wing corner, saw them to victory.

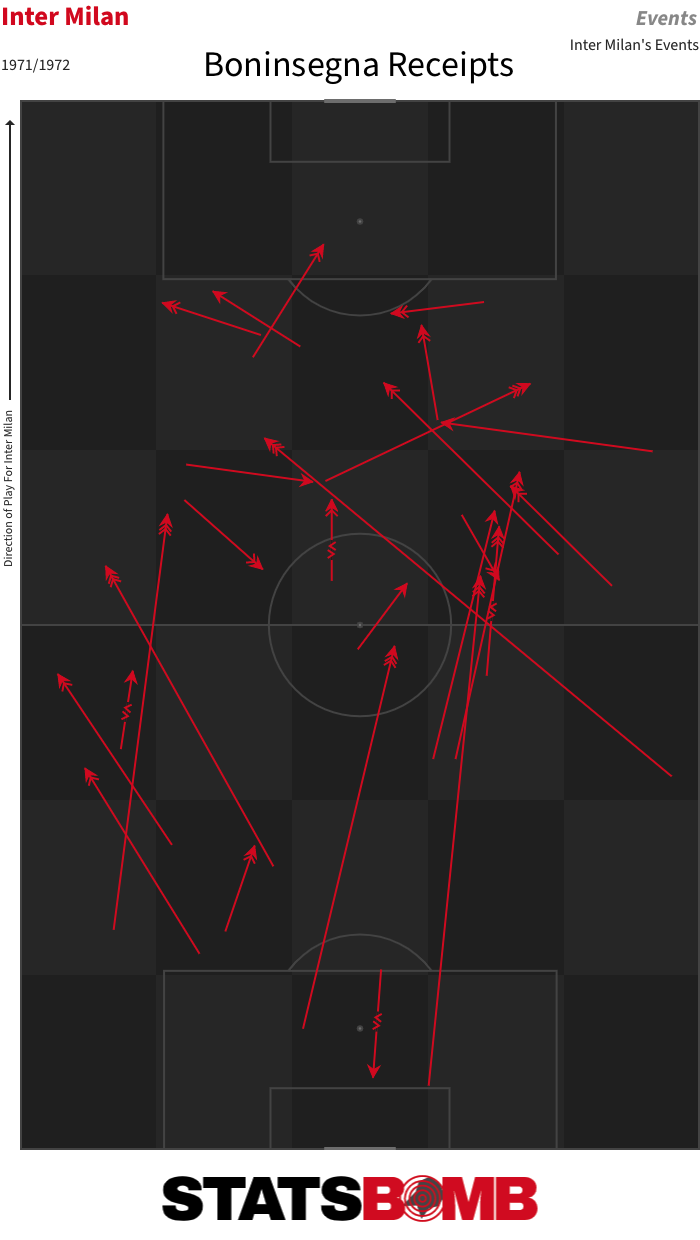

This Ajax team are largely thought of as an attacking one, but their approach was often just as, if not more effective in stifling their opponents. Their three consecutive European Cup triumphs in this era were all coupled with clean sheets. In this match, Inter were barely able to work the ball forward. When they did, it was usually thanks to the astute movement of Roberto Boninsegna off the front and into the channels.

But Boninsegna, Inter’s top scorer for seven consecutive seasons between 1969 and 1976, barely got a sniff at goal, and he and his teammates were only able to muster 0.42 xG from their 10 shots. Sandro Mazzola picked out a couple of nice passes in transition but was largely unable to influence things, partly due to the close attention of Johan Neeskens.

Mazzola and the other holdovers from the Grande Inter of the 1960s still weren’t all that old at the time of this match. Gianfranco Bedin was 26; Mazzola and Giacinto Facchetti, 29; and Jair da Costa, 31. Only Taricisio Burgnich, at 33, was obviously past his prime. Yet while their players might not have been, their style of play was certainly made to look so by a trailblazing Ajax side.

Long-Range Shots and Lots of Crosses

Where Ajax’s approach deviated from the modern game was in what happened once they got into the final third. Two of the key early takeaways from statistical analysis of football were that central shots closer to goal are far more valuable than wider and long-range efforts, and that crosses are generally a fairly inefficient means of creating chances.

Clearly neither team got the shots memo:

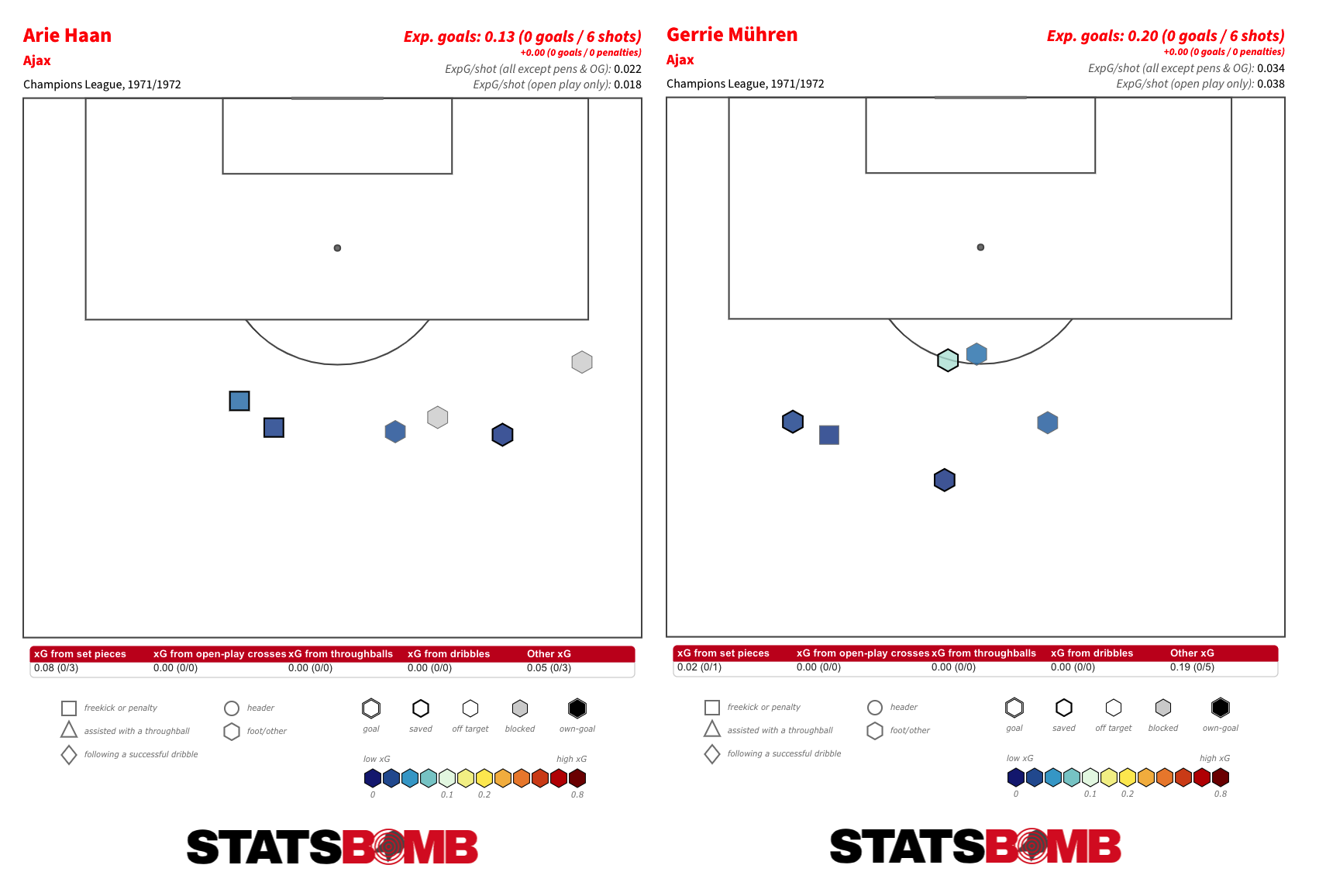

A shoot-on-sight policy particularly prevailed among the midfielders of Ajax:

Given their territorial dominance, Ajax really struggled to create good-quality chances from open play. Aside from Cruyff’s opener, none of their other 16 shots from open play were even 1-in-10 opportunities. There were even a couple of 1-in-100 swings. Indeed, that Cruyff goal, an easy finish after goalkeeper and defender collided to provide him with an open goal from an otherwise fairly harmless hanging cross, accounted for 58% of Ajax’s open-play xG.

That was also the only effort on goal to directly originate from one of the 29 crosses Ajax swung into the Inter penalty area. For comparison, the highest team average in last season’s Champions League was 14; the competition average, 7.84. Over half of their attempted box entries came from crosses, versus a competition average of 28% in 2018-19. Just two of the 15 deliveries from the right by Sjaak Swart and the ever-advancing full-back Wim Suurbier found their target.

This graphic of Ajax’s box entries shows how infrequently they moved the ball through the centre into the area. There was a cute early pass from Arie Haan and a couple of other incursions but not much given how much time they spent in the Inter half. Neither they nor Inter completed a throughball.

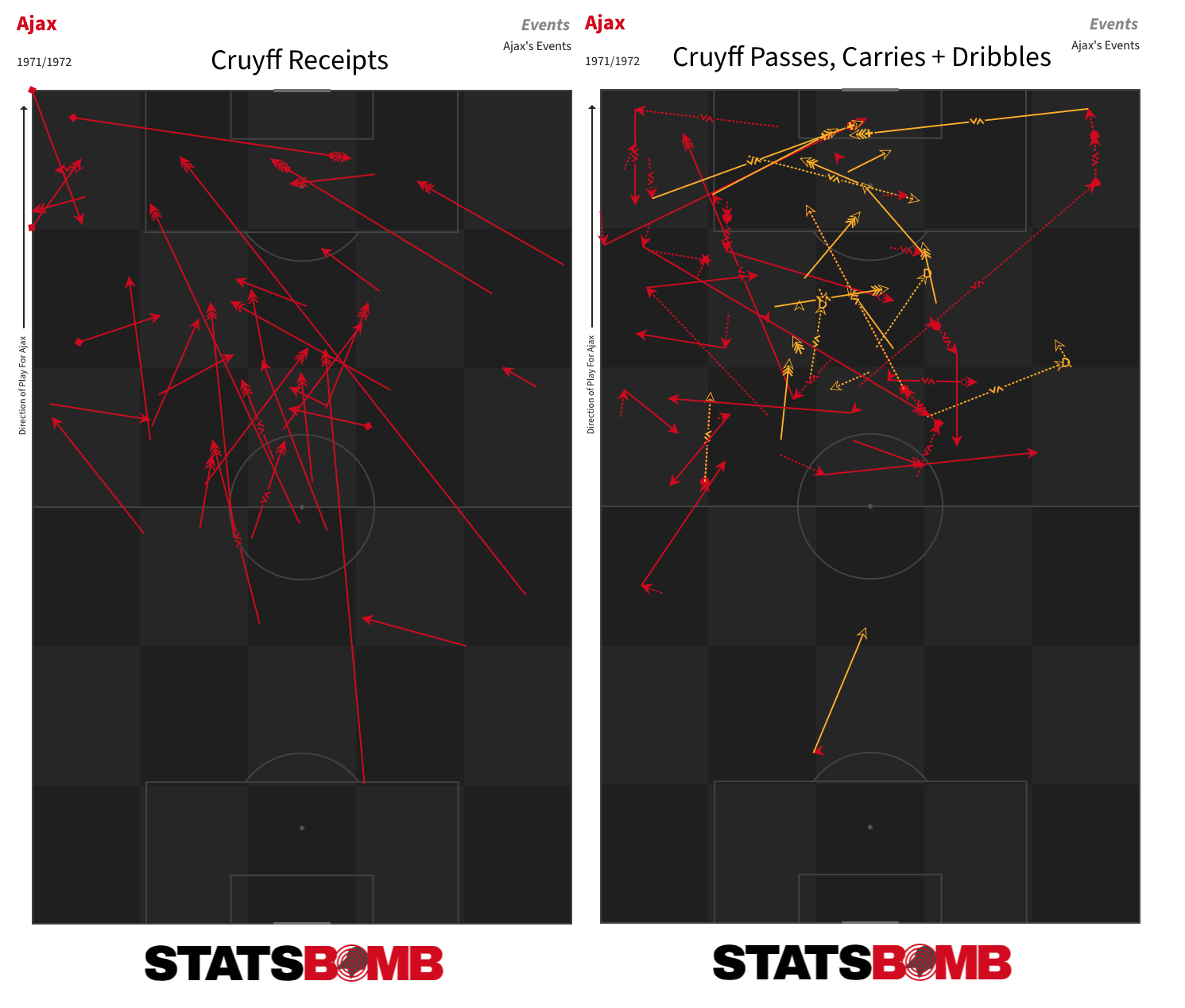

Johan Cruyff

Cruyff scored both of Ajax’s goals in this match, but it doesn’t act as a particularly good example of the idea we have of Cruyff as orchestrator of play. While he did drop back to receive in midfield at times, he attempted more individual actions than collective ones, and completed just 53% of his passes -- only two players, both for Inter, completed less. It was his supple changes of direction and neat burst of acceleration that stood out.

In amongst all of those Ajax shots, Cruyff only set up two, worth a paltry 0.05 xG. Three teammates moved the ball into the penalty area more often than he did. Where he did lead the team was in touches inside the area. Indeed, from this super small sample size of just a single match from a 20-year career he profiles as more of a mobile centre-forward than a playmaker masquerading as one.

Some Random Numbers and Observations

- the players who took part in this match were more ambidextrous than most. There were seven players within a 15% range of an even 50/50 split of passes between both feet. Inter’s Boninsegna had an exact split; Cruyff was only three percentage points off. For comparison, there were only two players within that 15% range in the 1960 final; and just one in 2019.

- the number of dribbles was slightly down from the 1960 final, but the figures of 47 attempted and 30 completed were both still well above those usually seen in the modern game.

- this match featured something we very rarely see these days: an indirect free-kick for obstruction inside the area.

The brainchild of Gabriel Hanot, editor of L’Équipe, the European Cup, now known as the Champions League, very quickly established itself as the pinnacle of European club football after its introduction in 1955. Many of the sport’s greatest teams have since made concrete their legacies by lifting the famous trophy.

With the help of our data, I am going to analyse a European Cup final from each decade, from the 1960s through to the present day, looking at the trends, developments and differences over the years.

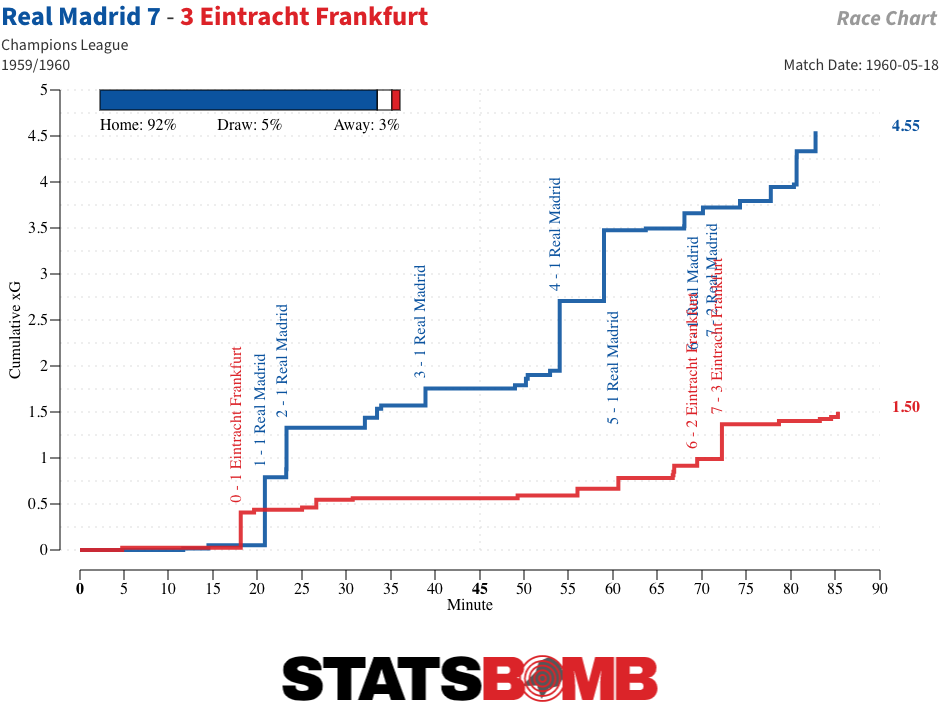

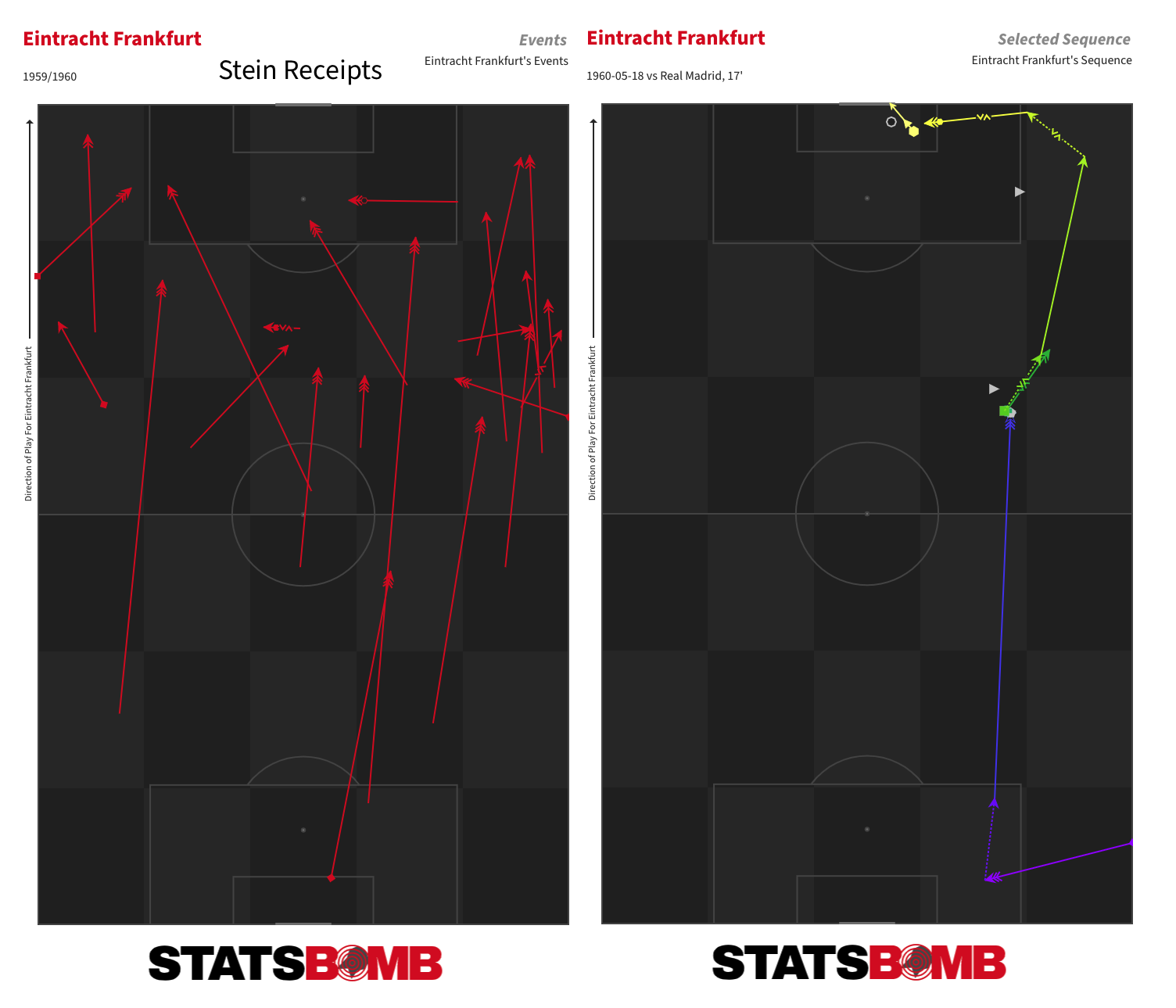

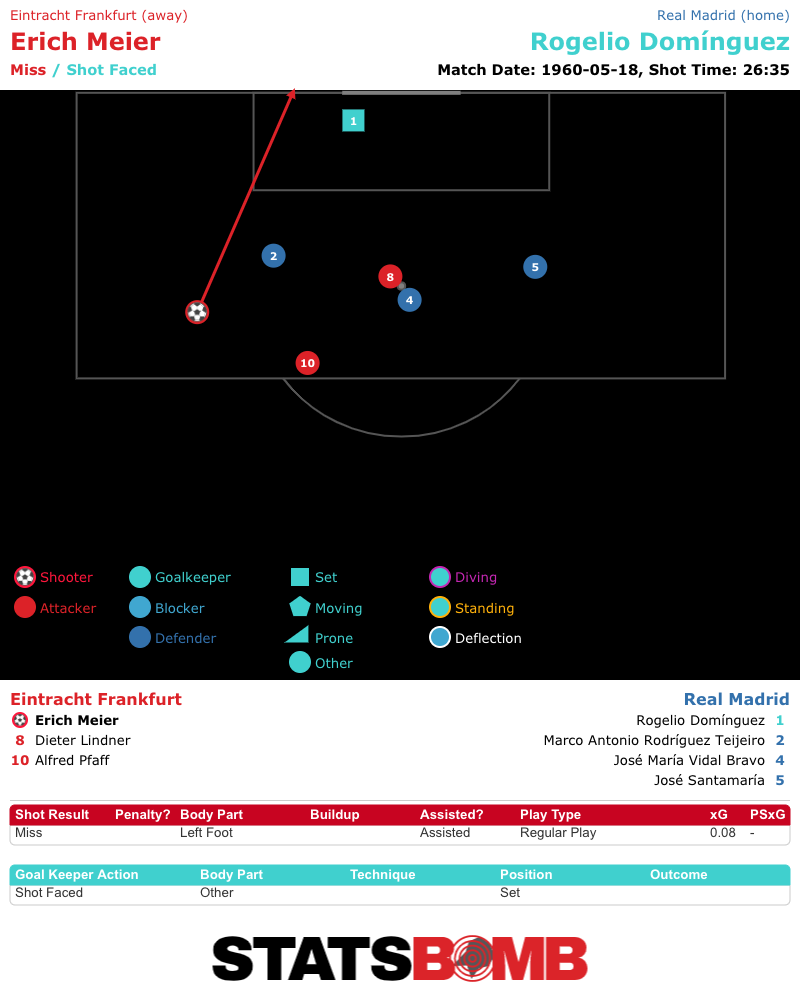

First up is Real Madrid’s 7-3 win over Eintracht Frankfurt in the 1960 final at Hampden Park in Glasgow, which remains the highest-scoring final in the history of the competition.

Real Madrid had won each of the first four editions and had lost just six times in 35 European Cup matches prior to this encounter. More than any other, they are a team defined by this competition.

Formations

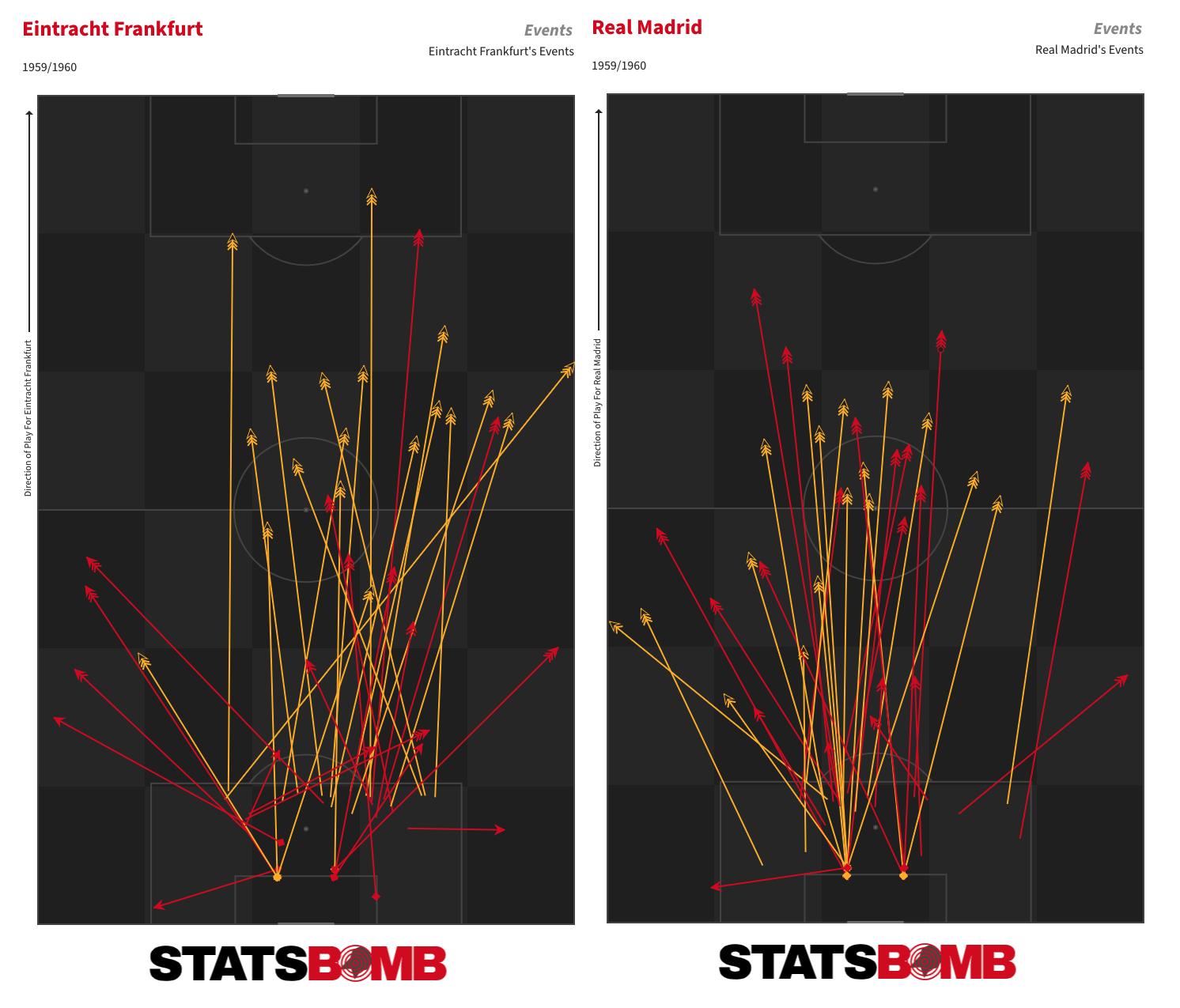

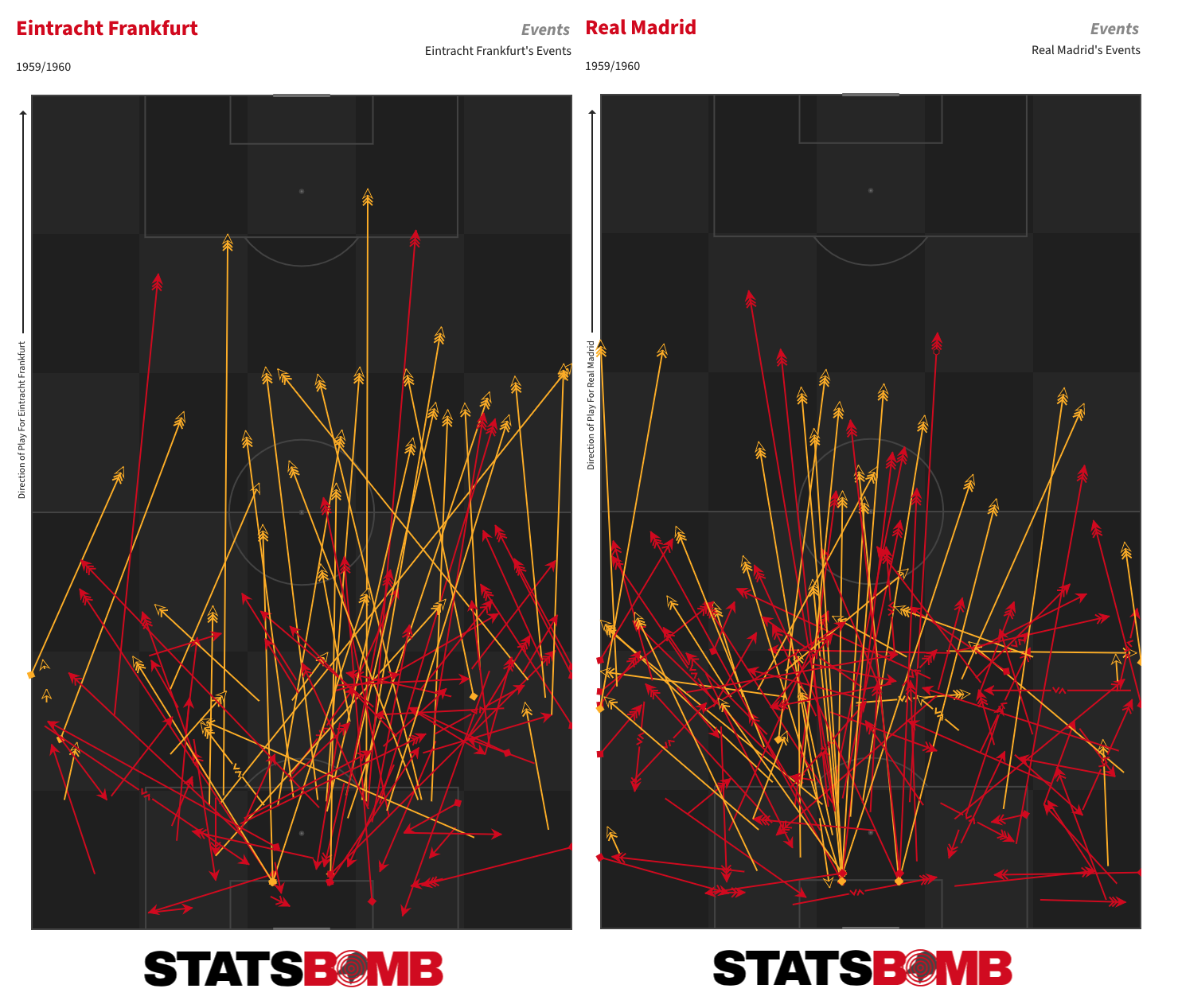

This is still more or less the era of the 3-2-2-3 (WM) formation, with wingers, inside forwards and a centre-forward making up the front line. With certain variations, both teams employed that system.

A Fast and Imprecise Game

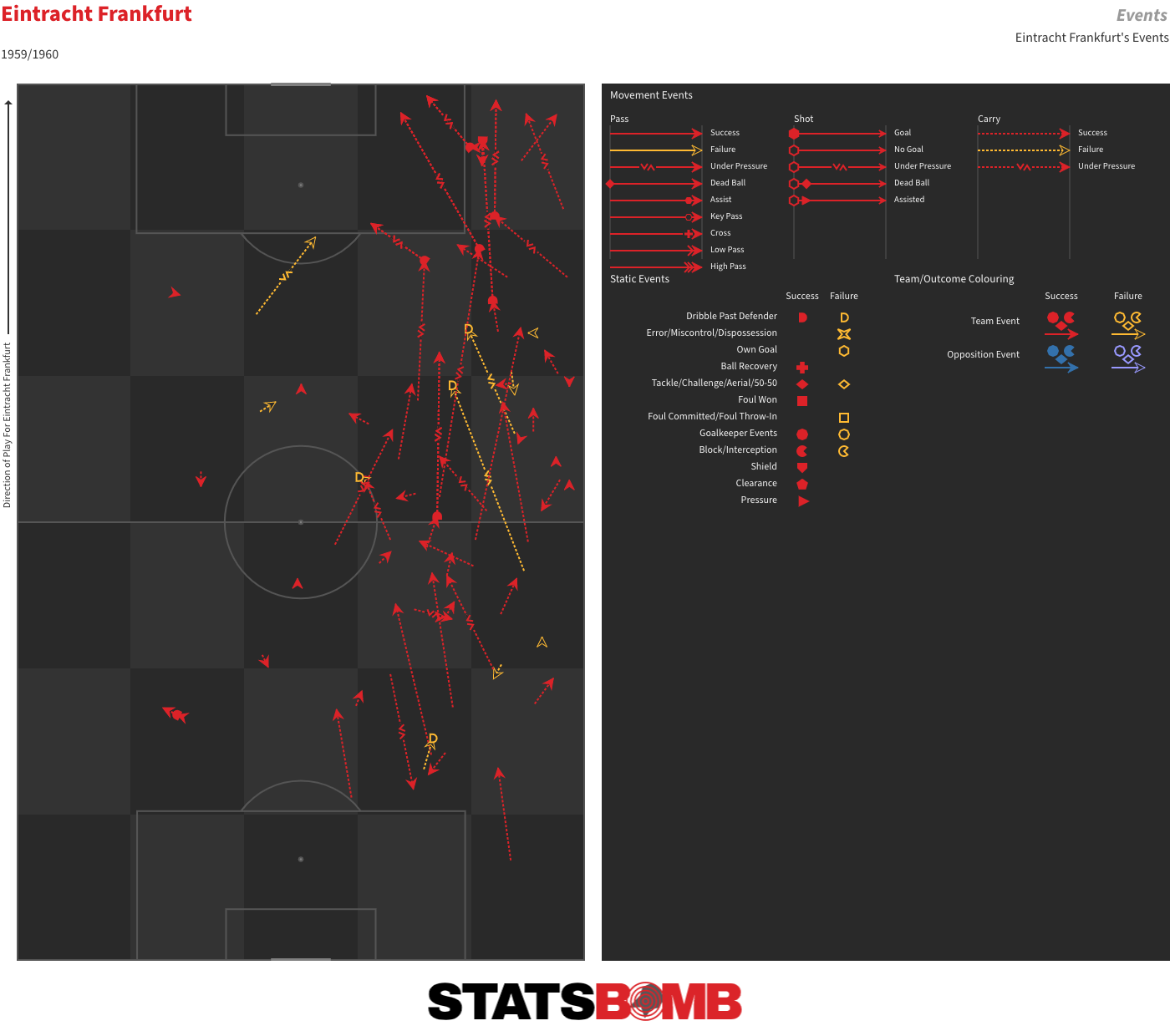

The first thing that immediately stands out is the number of times the teams turned over possession. Real Madrid completed just 69% of their passes; Frankfurt only 61%. For comparison, the average passing completion rate in last season’s Champions League was 80%. There were 483 distinct possessions in this match, compared to 374 in an average modern-day match in the competition.

In the commentary, much is made of the bumpy surface at Hampden Park. That may certainly have contributed, but those completion rates feel more like a consequence of the directness with which both teams played. This is the textbook example of a back and forth shot-fest. Upon gaining possession, both teams moved forward at a faster rate than modern-day teams, and the final shot count of 42 was 13 more than the tally in the 2018-19 final, and 15 more than last season’s competition average.

You don’t see many matches with xG sums like this these days:

This was a contest of quick passes, flick-ons and direct duels. Between them, the two teams attempted a mammoth 55 dribbles, of which 33 were completed -- itself about the average rate of attempted dribbles in last season’s competition.

Goalkeepers Go Long

The impression I had when watching the match was that the two goalkeepers kicked long a lot more often than those of top teams in the modern game. Frankfurt’s Egon Loy got particularly impressive distance on a number of his first-half dropkicks.

The numbers bear that out. The average goalkeeper pass lengths of the large majority of teams considered viable winners of the contemporary Champions League fall within a range of about 32-40 metres. In this match, Real Madrid’s average was 48.86 metres; Frankfurt’s 50.93.

There were very few passing moves built up patiently from deeper areas. Real Madrid elaborated a little more inside their defensive third, but both teams mainly sought to quickly get the ball forward into the attacking half.

The majority of attacking moves arose from contested loose balls in the middle third of the pitch.

Alfredo Di Stéfano: All-Round Forward

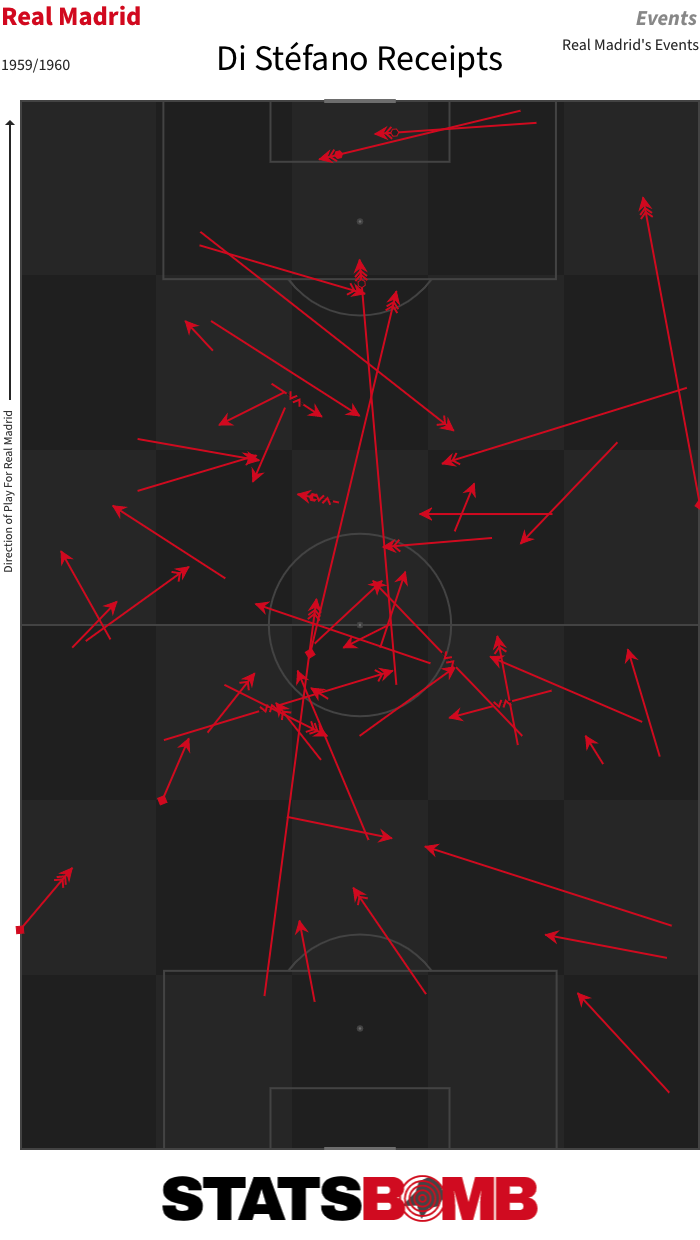

Alfredo Di Stéfano perhaps deserves a more prominent place in discussions over the best player of all time. A league-title winner in three different countries and the driving force behind Madrid’s five consecutive European Cup triumphs, he was not only a prime goalscorer but also a highly adept organiser of play.

In our recent series on Lionel Messi, I mentioned that Di Stéfano was the kind of withdrawn and roving forward that we’d probably describe as a “False Nine” in modern parlance, and that is very much played out by his role in this match.

Di Stéfano’s first involvement is deep inside own half, receiving the ball from a teammate, dummying to pass and moving forward into the created space. It is a scene repeated throughout, usually accompanied by gestures of suggested movements for those around him. His receipt locations demonstrate the extent of his involvement in constructing play and bringing the ball forward.

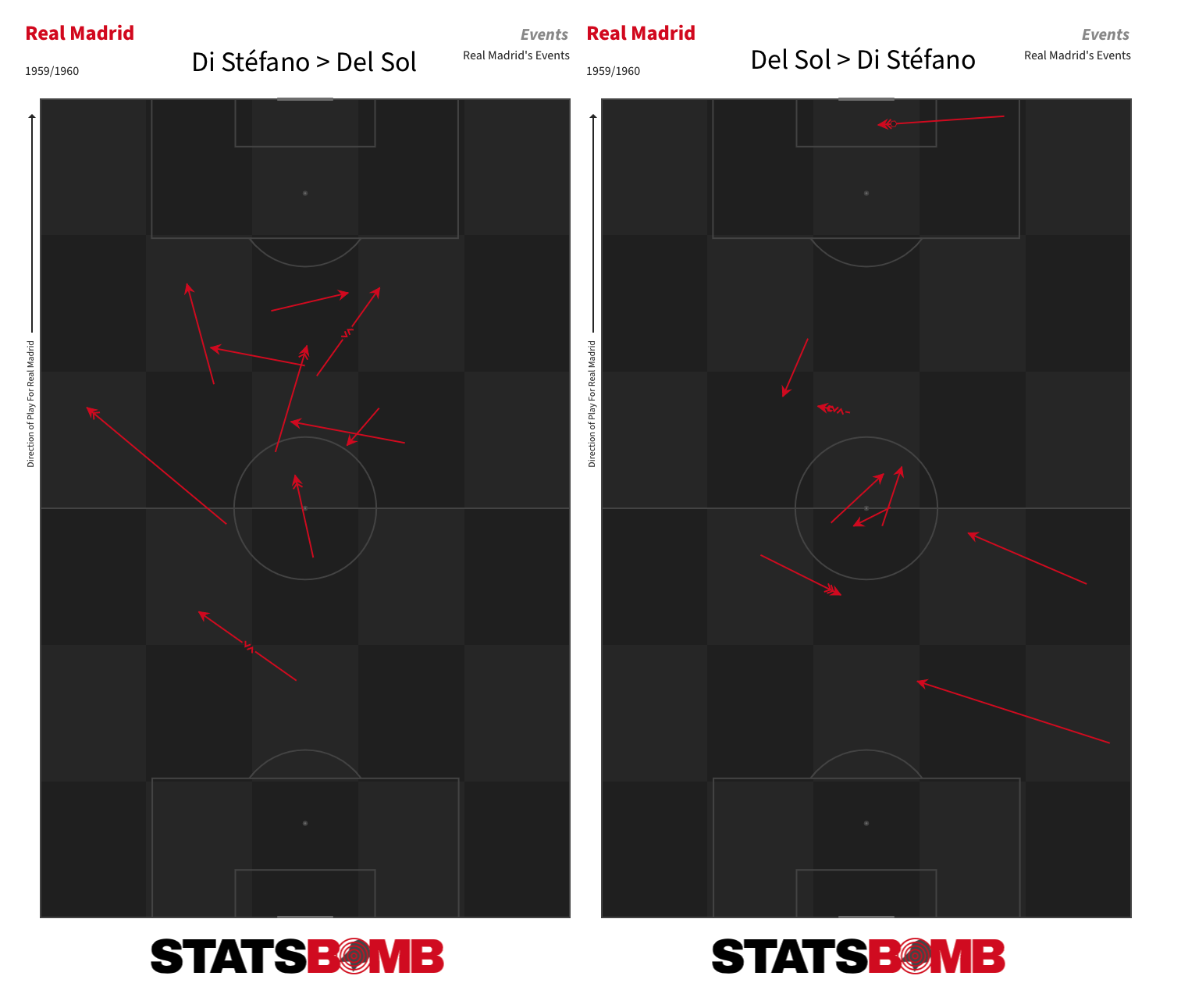

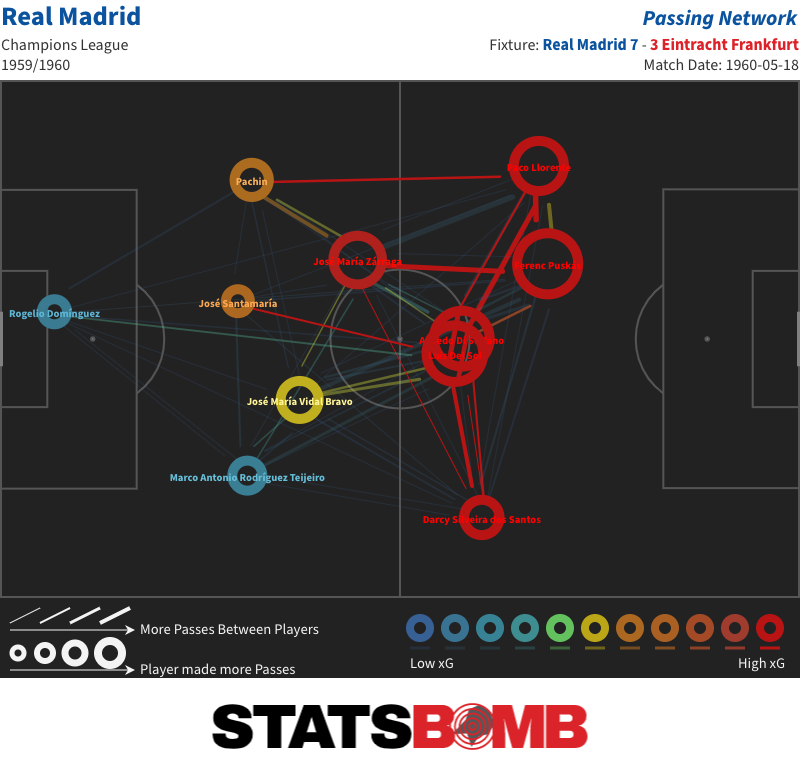

In Luis del Sol, an inside forward of energy and class, he had a key accomplice. They exchanged more passes than any other pair of players.

When Di Stéfano did appear in areas more consistent with his starting position as a centre forward, it was largely to finish from close range inside the penalty area. That was how two of his three goals arose.

The third came from a kickoff. After exchanges with Gento and Del Sol, he accelerated through the centre of the pitch before firing home a crisp effort into the corner from outside the area. One of the great European Cup final goals.

Puskás the Sharpshooter Di Stéfano may have notched a hat-trick, but he wasn’t Madrid’s top scorer on the day. That honour fell to Ferenc Puskás, nominally the inside left but more often than not Madrid’s most advanced player.

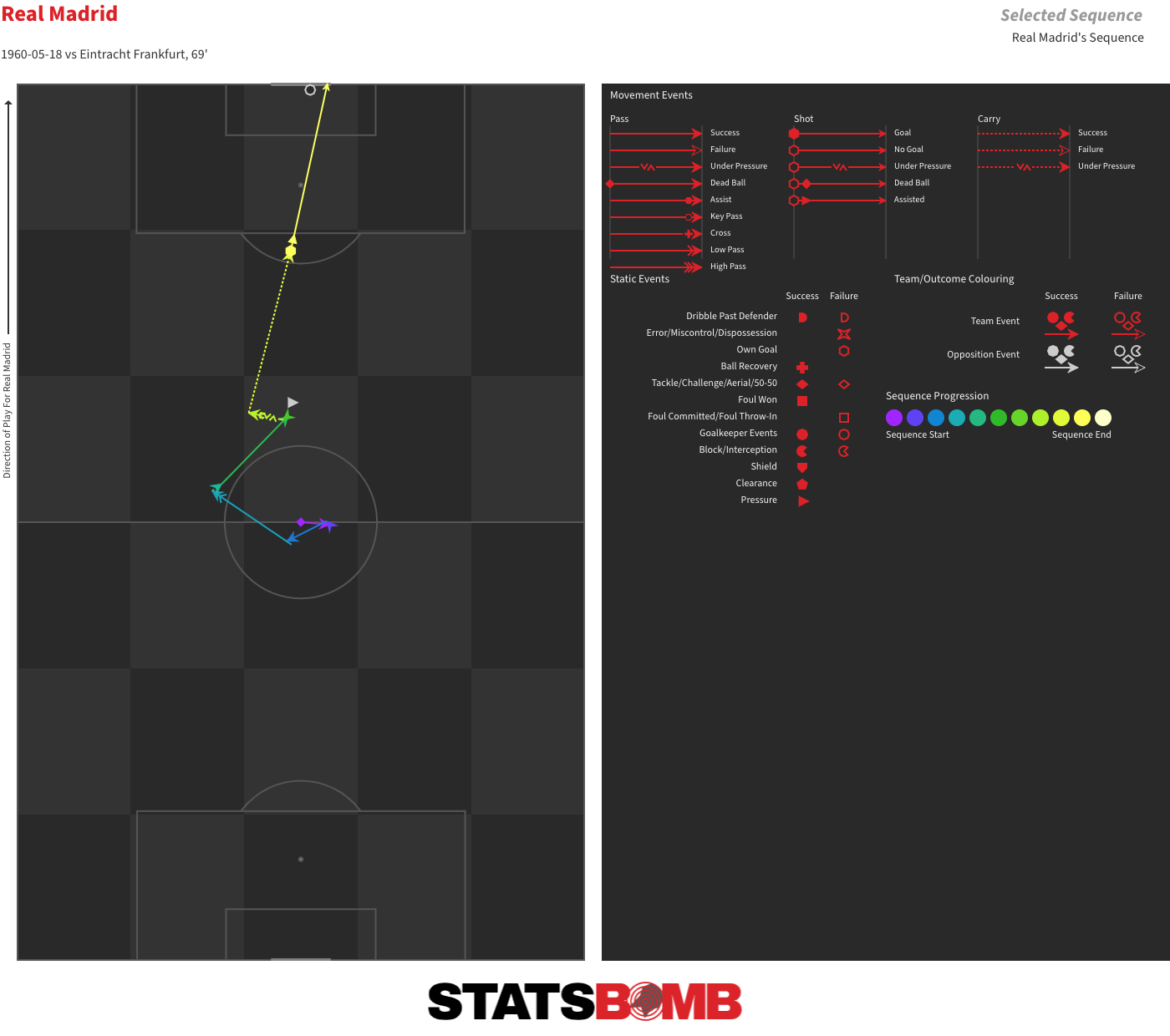

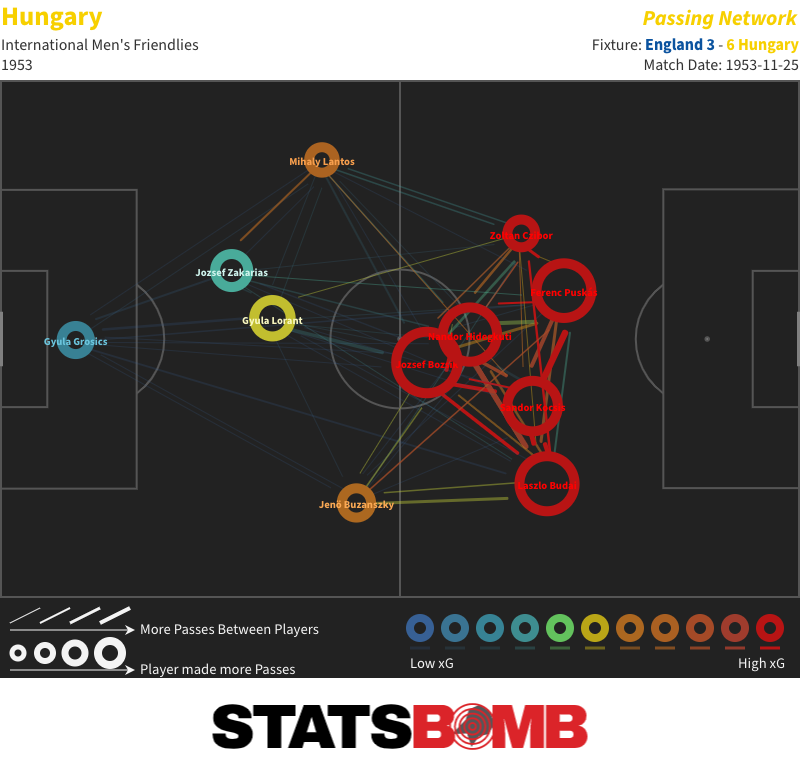

It was a role Puskás was used to performing. In the great Hungary side of the 1950s, he played alongside Nándor Hidegkuti, who, like Di Stéfano, was often more of a withdrawn playmaker than an outright centre-forward. If we look at the pass map from Hungary’s famous 6-3 win over England at Wembley in 1953, it is interesting to note just how similar the relative positioning and spacing is between Puskás and Hidegkuti there, and Puskás and Di Stéfano in this final.

Puskás was notorious for his powerful shot, and he does seem to spend a fair amount of this match casually walloping the ball goalwards whenever it comes his way. Even in a match of many shots, his total of 11 is still five more than any other player on either side.

His four goals (including one penalty) should have earned him the match ball for keeps. But the persistence of Frankfurt captain Hans Weilbächer eventually wore him down.

Eintracht Frankfurt’s Attack Frankfurt started the match well and even took the lead, but Madrid’s greater talent eventually began to shine through. By half-time, it already seemed likely they would be the losing side. The attacking output provided by their two inside forwards was much more limited than that of their Madrid counterparts.

The threat Frankfurt did carry came from the two wingers and centre-forward Erwin Stein. Richard Kress was a regular menace down the right, receiving and driving forward at every opportunity.

But it was Stein who caused most damage, scoring twice and assisting the other. In an era of man-marking schemes, it was interesting to note just how disruptive his peeled runs into the right channel proved for the Madrid defence. It was Frankfurt’s most reliable method for advancing into the final third and it yielded the opening goal of the match. He received a pass into that space from Dieter Lindner, drove on to the byline and crossed to the near post for Kress to finish.

Obstruction

To the modern eye, some of the fouls called in this match looked very soft indeed. The standard for what was considered an obstruction was obviously much lower at the time. Merely placing yourself somewhat across your opponent’s path was enough to be penalised. Madrid’s penalty is the very mildest of mild obstructions.

“He Should Have Scored” Watch

Our commentator, Kenneth Wolstenholme: “You can’t afford to miss chances like that and win the European Cup.”

Zinedine Zidane, ahead of the 2018 Champions League final. "I'm not the best coach, and I will always say that. I am not the best coach tactically... and, well, I don't need to say that because you lot always say that, anyway.” When Zidane returned to Real Madrid in March of last year, nobody knew what to expect. His first spell was a paradox, pairing historic achievements with bizarre inconsistency. The squad was incredible but also heavily reliant on individual heroics; with Cristiano Ronaldo gone and less talent at his disposal, many felt he would have to evolve. Madrid’s collective organization declined over the course of Zidane’s original tenure.

His first season was characterized by his unique strengths: convincing stars to defend and accept rotation, and starting Casemiro over more glamorous names in spite of Florentino Perez’s pressure. His final season was a tactical disaster: excessive crossing, Casemiro making runs forward, and Luka Modric defending at right back. One thing was abundantly clear then and now: Zidane’s ego doesn’t distort his evaluations, be it of players, coaches, or even himself. He is aware of his limitations, a theme going back to his own playing career. This is a man who resigned after a Champions League threepeat because he saw the writing on the wall for his burned out squad and didn’t try to defy it.

When he returned he was risking his legacy, but he seemed convinced he could again achieve success.

The Enigmatic Start To The Season

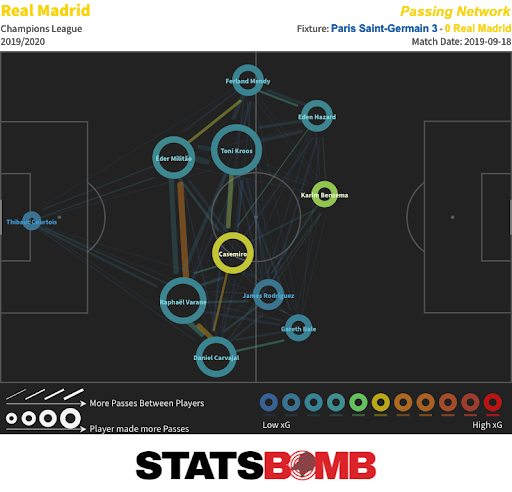

If Zidane had evolved, it was not immediately apparent. Pre-season was muddled by injuries to key players, a 7-3 loss to Atletico Madrid, and confusion over transfers. With Ronaldo long gone and the team needing goals from midfield to compensate, the squad depth seemed to lend itself to a 4-2-3-1 shape, accommodating James Rodriguez:

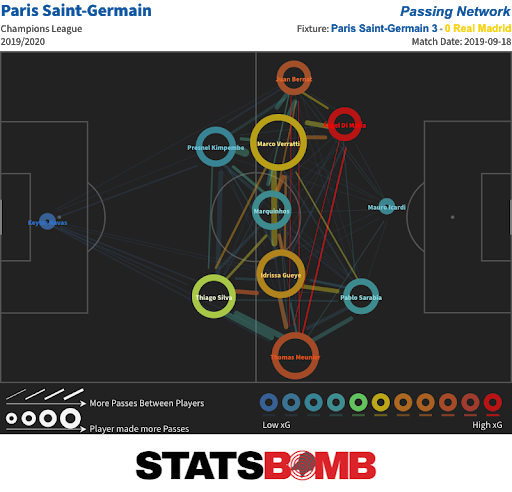

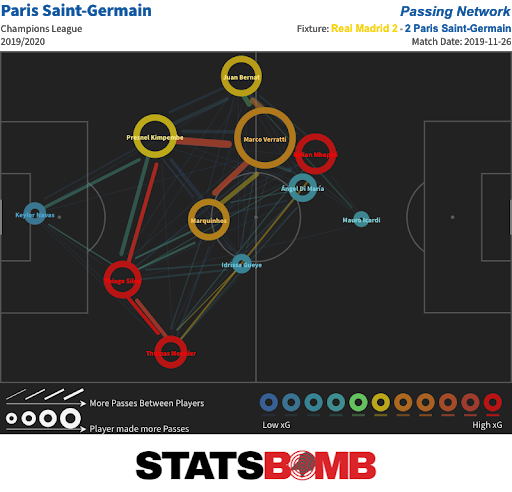

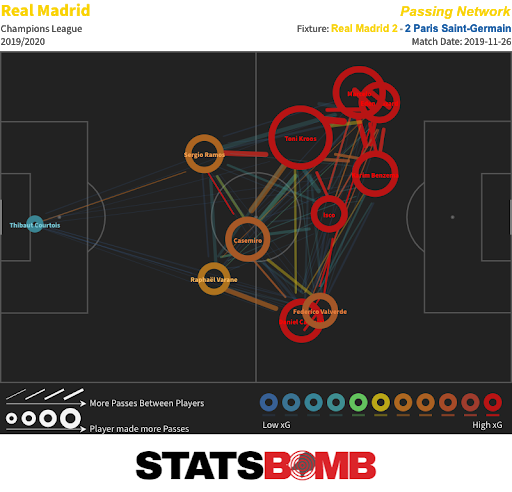

But every time Zidane played this midfield, Madrid’s buildup play suffered regardless of opposition. Without Luka Modric next to him, Casemiro took far too many risks near his own box. The defense wasn't working either, and much like Zidane’s first spell, Sergio Ramos and Raphael Varane were left to defend acres of space whenever they conceded a counterattack. This all culminated in the loss to Paris Saint-Germain. With Casemiro playing in the double pivot against Thomas Tuchel’s high pressing side, Madrid were played off the park. Casemiro’s usage and the total lack of connectivity standout:

PSG, however, managed to maintain excellent symmetric spacing. They sliced through the Madrid defense even without Neymar and Kylian Mbappe:

The aftermath of this game brought suggestions that Zidane could be sacked. Six full weeks into the season, after a huge summer outlay, the team was performing far below potential.

Revitalizing The Defense

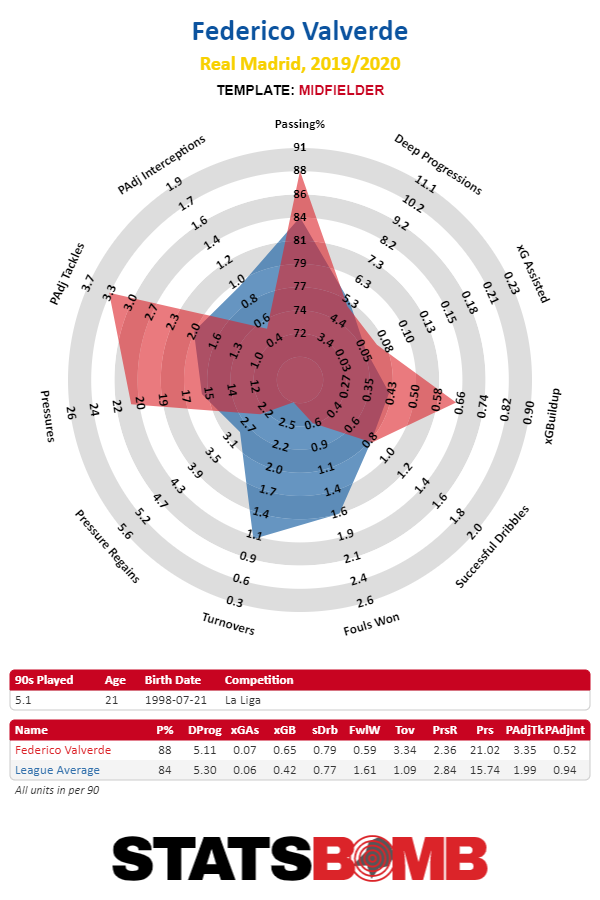

With the 4-2-3-1 experiment failing, Zidane moved back to a three-man midfield. Most importantly, he organized a stifling defense based around a more frequent press. The key to this change was the introduction of Federico Valverde as a box to box midfielder. His defensive intensity rubbed off on his teammates.

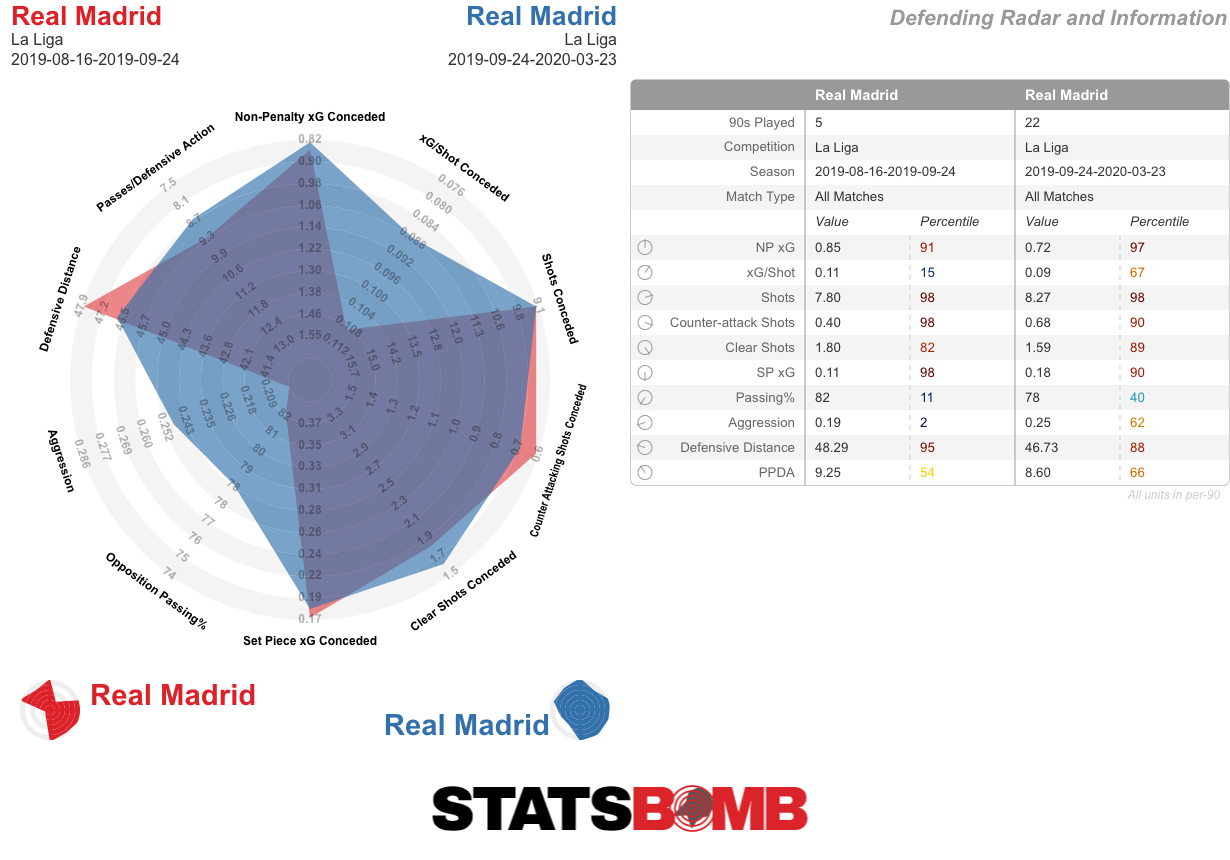

Valverde’s pace and physicality catalyzed a much more aggressive Real Madrid able to lean into their defensive identity. Opposition passing chains were more frequently contested, and opponents’ passing completion rates dropped. The shift is perhaps best illustrated by the change in the percentage of their defensive actions that we define as aggressive -- actions recorded within two seconds of the opposition receiving the ball. In the six games before Valverde’s introduction, Madrid were in the 2nd percentile of this metric. Ever since, they’ve ranked comfortably above average:

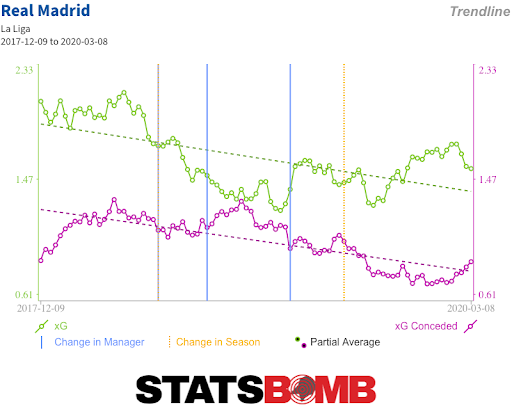

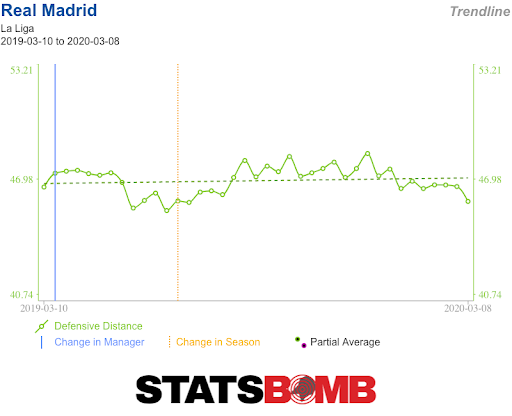

Opponents struggled to create high quality chances. This reorganized Madrid defense was among the best in Europe, and the best at the club in years. Their improvement is clearly visible in the xG trendline:

Buildup play also improved. Casemiro started taking a more passive role in buildup with Valverde available. The team was better able to reach the final third, and for a brief period when both Eden Hazard and Marcelo were healthy, they created chances at will. This is well illustrated by the reverse fixture against PSG. Madrid dictated terms with their high press, and Tuchel’s side were the ones with a disheveled passing network:

Zidane opted to play Isco in the diamond shape that won Madrid their Champions Leagues, with Hazard and Valverde replacing Ronaldo and Modric respectively. For the first hour this was one of Madrid’s most dominant performances in recent seasons.

The difference in Casemiro’s role between each game is telling. He played roughly the same number of passes in both games, even though Madrid had much more of the ball at the Bernabeu. When the team was clicking offensively, his relative usage rate was down.

Lingering issues

After a strong end to 2019, the xG trendlines correctly reflect that, for many reasons, Madrid have been relatively inconsistent. Offensively, the team has caught bad luck with injuries. Marcelo’s injuries signal the definitive end of his prime, and he isn’t even attempting one dribble per 90 anymore. His replacement, Ferland Mendy, is completing 2.5 per 90, but he is more effective with space than against a deep defense. Eden Hazard has missed most of the season due to injury.

Behind him, Vinicius Junior’s finishing and combination play leaves much to be desired. That he is up to 0.48 expected goals and assists per 90 minutes is encouraging in the long term, but his actual scoring contribution is only 0.28 goals and assists. This season, Madrid needed Hazard to reach their offensive ceiling. Marco Asensio, who was set to get an extended run at right wing, tore his ACL in the summer.

The domino effect played a role in both Rodriguez and Gareth Bale staying at the club. Rodriguez has struggled to stay fit and has barely contributed. Bale’s production is down to 0.43 expected goals and assists per 90 minutes, and he doesn’t appear to have the ability to seize games anymore. Arguably more than any other top coach, rotation is at the heart of Zidane’s coaching philosophy as well. He is uncompromising, and has reaped the rewards by winning the Champions League in every season he completed as head coach.

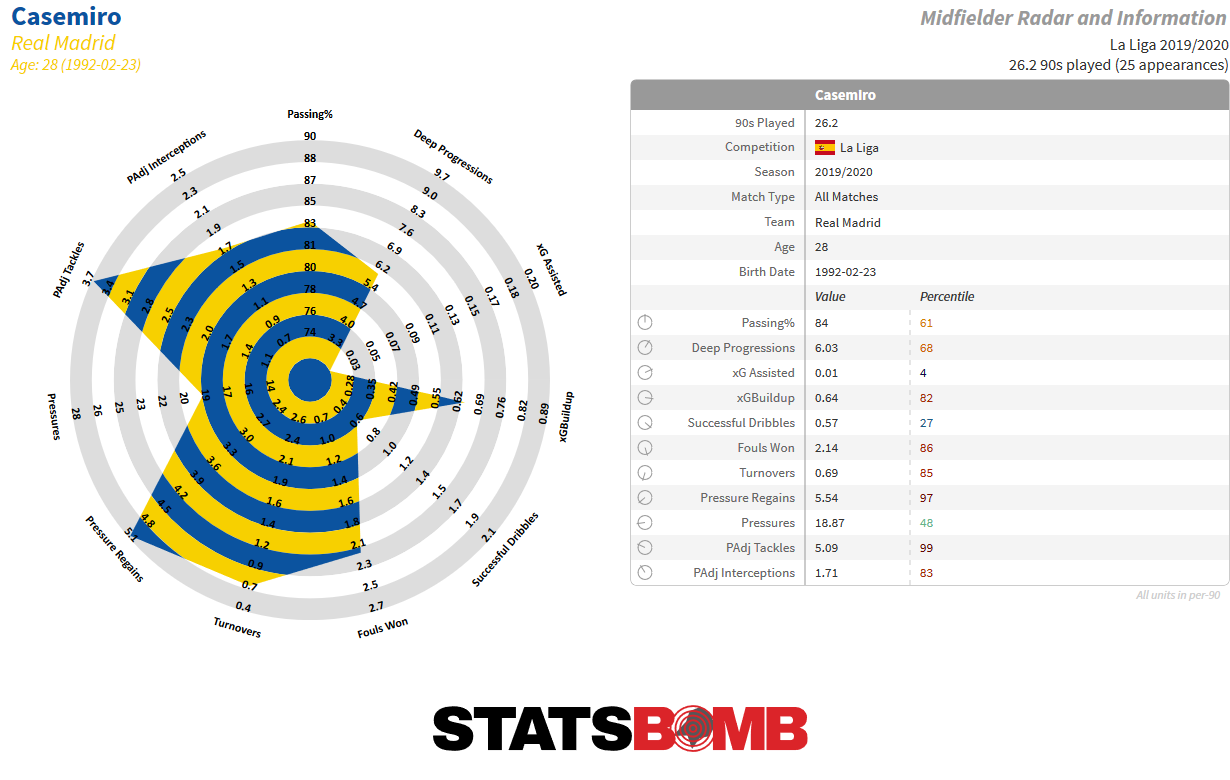

This season, however, that rotation has hurt the team’s cohesion. Defensively, there is no natural replacement for Casemiro. He sat on the bench as Madrid conceded four goals en route to a Copa Del Rey elimination against Real Sociedad. He is arguably the best destroyer in Europe. Over the past few seasons, he ranks in the 98th percentile for possession-adjusted tackles and 99th percentile in pressure regains among midfielders in the big five leagues.

Valverde is also hard to replace. Modric was an excellent defensive presence a couple years ago, but at 34 he struggles to match Valverde’s tenacity. Starting January, Zidane began rotating the duo more heavily, and Madrid’s defensive line has moved slightly deeper as a result:

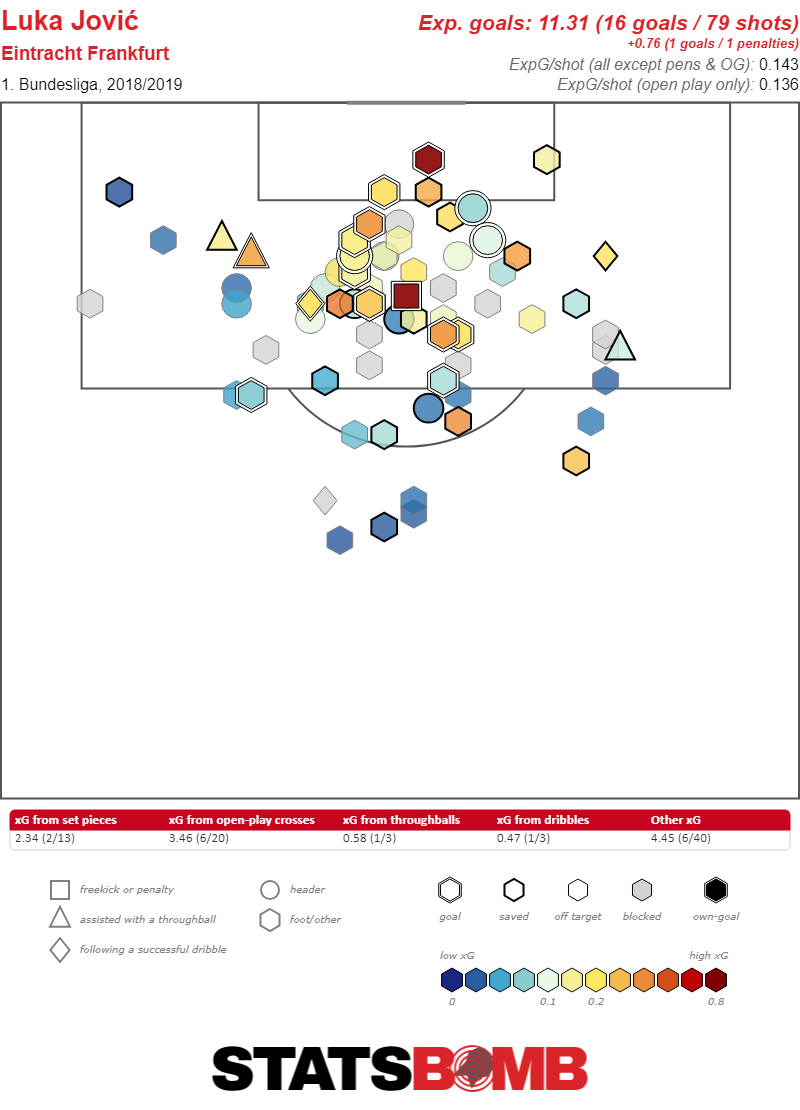

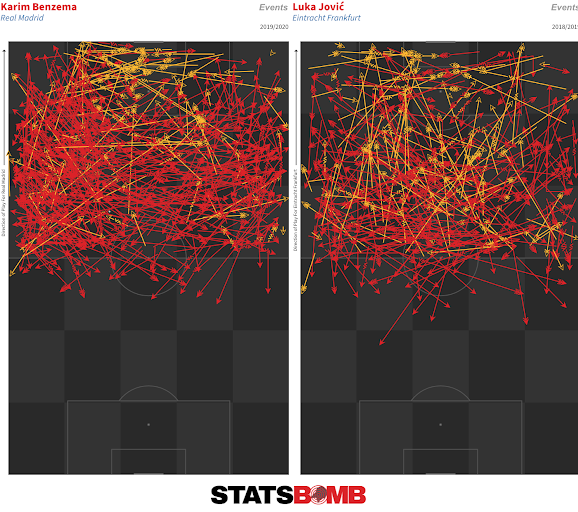

This rotation policy, combined with a limited approach in the final third, is why Zidane has struggled to integrate Luka Jovic. The Serbian was supposed to help replace Ronaldo’s production, but has only played five full games worth of minutes in La Liga. Karim Benzema has had to shoulder the scoring load, with others chipping in.

Jovic is putting up far fewer shots at Real Madrid, often looking disconnected from the unit on the pitch. This is partly fuelled by a change in role. At Frankfurt, Jovic was involved in a far more direct team, and had more space to work with. He would receive the ball in central areas and lay it off against less compact defenses. With more space, he had the license to take more risks.

At Madrid, he often faces deep lying defenses, is often isolated up front, and rarely seeks to combine at a slow pace. It doesn’t help that he’s trying to replace Benzema, who is among the best strikers in Europe at this very role. Benzema is all about making himself available to receive the ball in the half spaces to combine with full backs. The difference in pass attempts also reflects how Jovic was used to playing faster and more vertically:

Zidane isn’t blameless here. Jovic has only started four games in the league. He often comes onto the pitch at the expense of a midfielder, when Zidane switches to a 4-4-2 while chasing the game. This leaves Casemiro exposed in a double pivot, and Madrid have subsequently lost control of the ball instead of feeding Jovic. On a team level, Madrid attempt far too many aerial crosses. This is a habit carrying over from Zidane’s first spell, when Ronaldo was a target, but is less effective with Benzema leading the line alone. Perhaps more low, cut back crosses are in order. The bulk of the improvement, however, will come with new personnel and time.

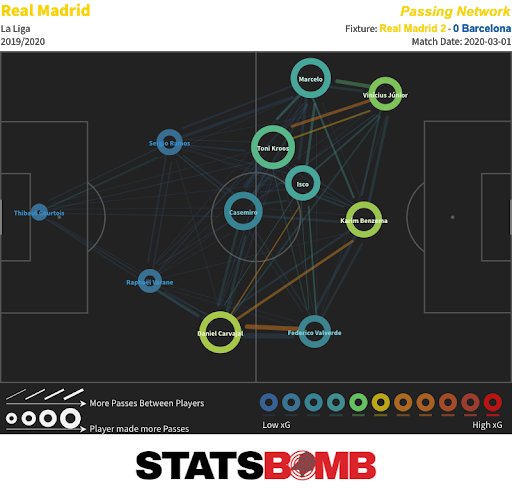

Completing The Team

To succeed with Zidane, Madrid will primarily require better offensive talent and depth. The attack also needs more symmetry; most of the team’s high usage players in each line of play operate on the left (Ramos, Toni Kroos, Isco, Hazard and Vinicius). Most passing networks resemble this:

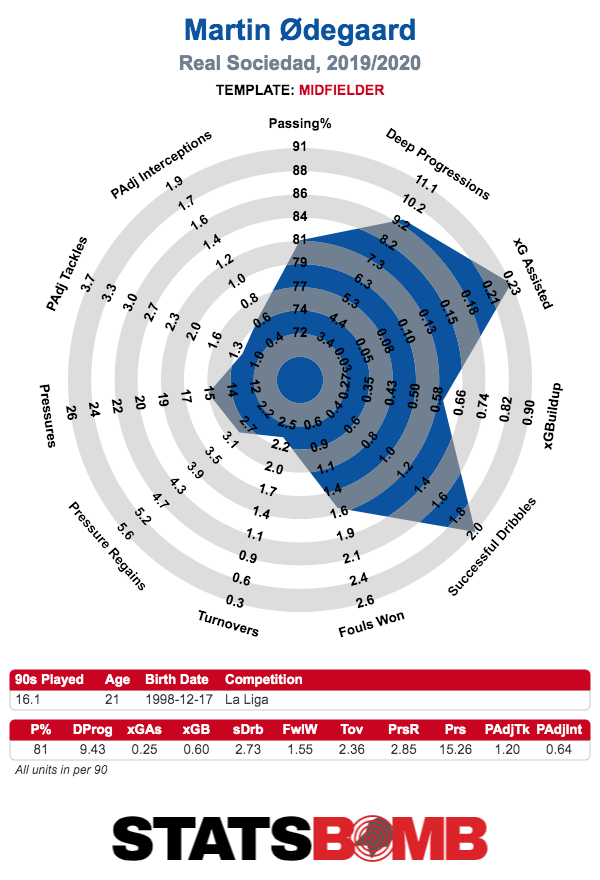

Given their needs, Madrid’s returning loanees and the players they’ve been linked with fit extremely well. For starters, Martin Ødegaard - if his loan is cut short - would be a better fit than Isco. Isco is a ball magnet. He excels at creating numerical overloads, dribbling and drawing fouls in tight spaces, but is not great at creating chances. This is why he’s been more effective for Madrid in big Champions League ties, helping Madrid control the ball and evade the high presses of Liverpool, Bayern Munich and others, than in the league, where he’s asked to break lines against deep defenses.

In contrast, Ødegaard is among the best at scanning his surroundings and breaking defensive lines. Team style shouldn’t be discounted here, but on the evidence of this season, he is a much more direct player, consistently seeking to receive the ball between the lines and completing more deep progressions. Ødegaard plays 26% of his passes forward to Isco’s 15%, and only 9% backwards to Isco’s 14%. They complete a similar number of dribbles, but the former releases the ball faster instead of drawing fouls:

Ødegaard is a high IQ passer, and would help restore some symmetry by operating on the right of the midfield zone:

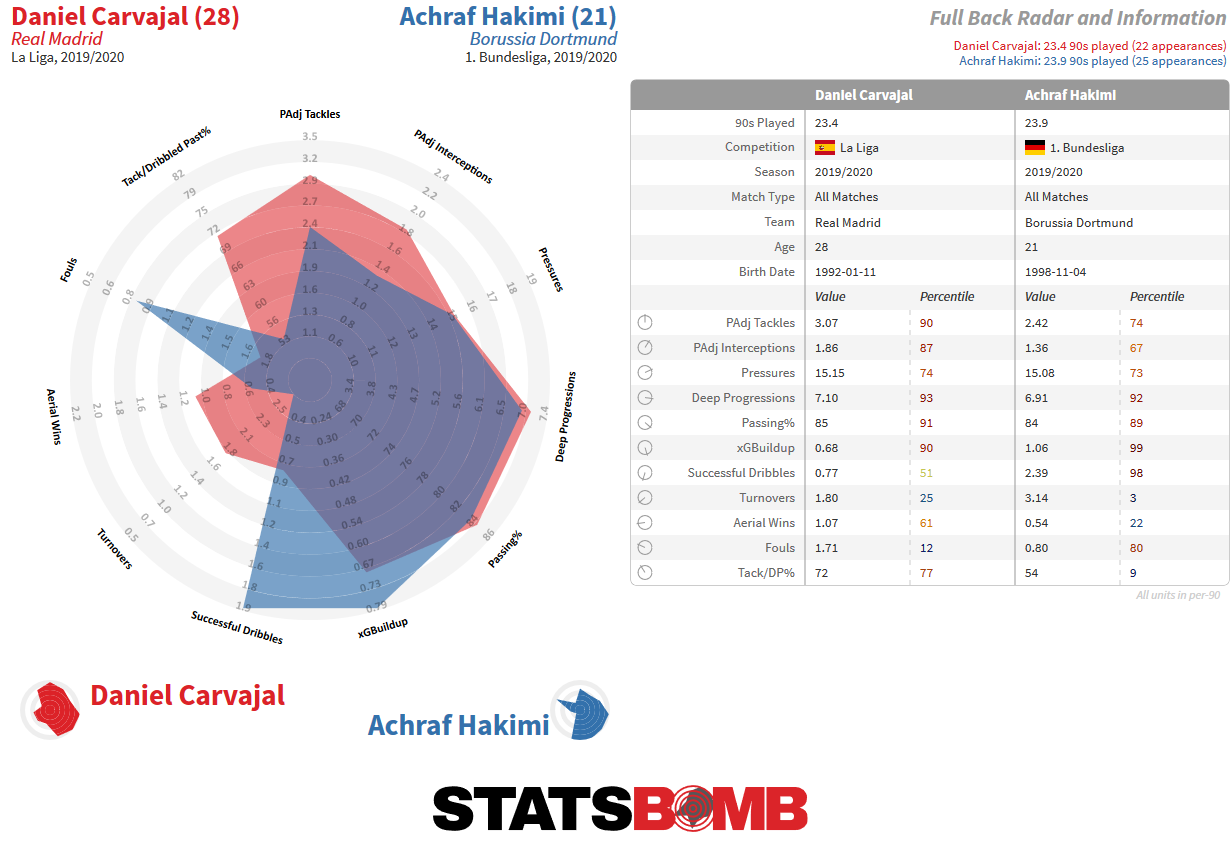

Achraf Hakimi is set to return from loan and is an excellent fit as well. Madrid need more attacking quality at full back to replace Marcelo. Carvajal sufficed in the past, but his solid aerial crossing technique has proven less useful since Ronaldo’s departure. Hakimi is by no means as diligent a defender as Carvajal. This bears out in the numbers: Carvajal is dribbled past less often, contests and wins double the aerial duels. But Hakimi is a better dribbler, carrying the ball more often and further when he does.

At 21, Hakimi is still growing. He has turned the ball over more often this season than any Real Madrid player barring Eden Hazard. He may not displace Carvajal immediately, but he does address Madrid’s offensive weakness on the right wing. On the right wing, the suspension of football gives Marco Asensio a fantastic chance to return from injury as the same player as well.

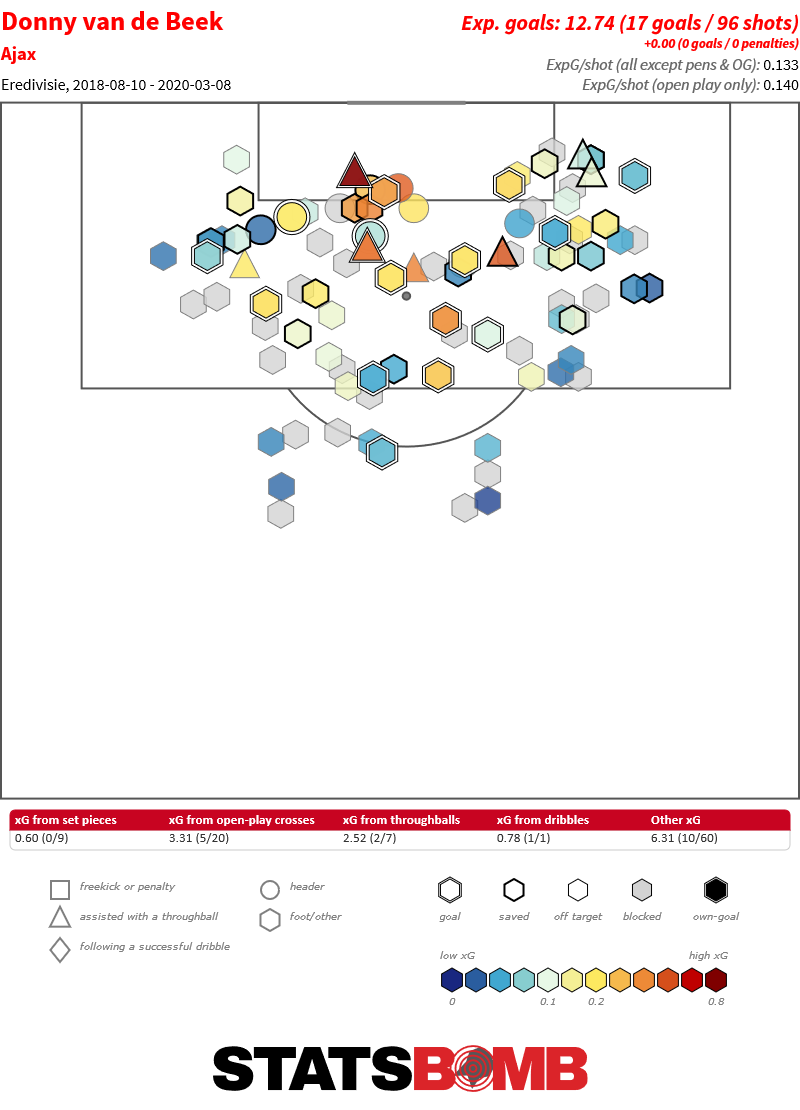

Most complications after recovering from ACL tears take place when a player is rushed back. Another name linked to Madrid is Donny van de Beek. Profiling as an offensive alternative to Valverde, he is a high volume tackler, and also excels with his late runs into the area. He shoots and gets more touches in the box than any Madrid midfielder, contributing to a goal every other game -- albeit in the Eredivisie.

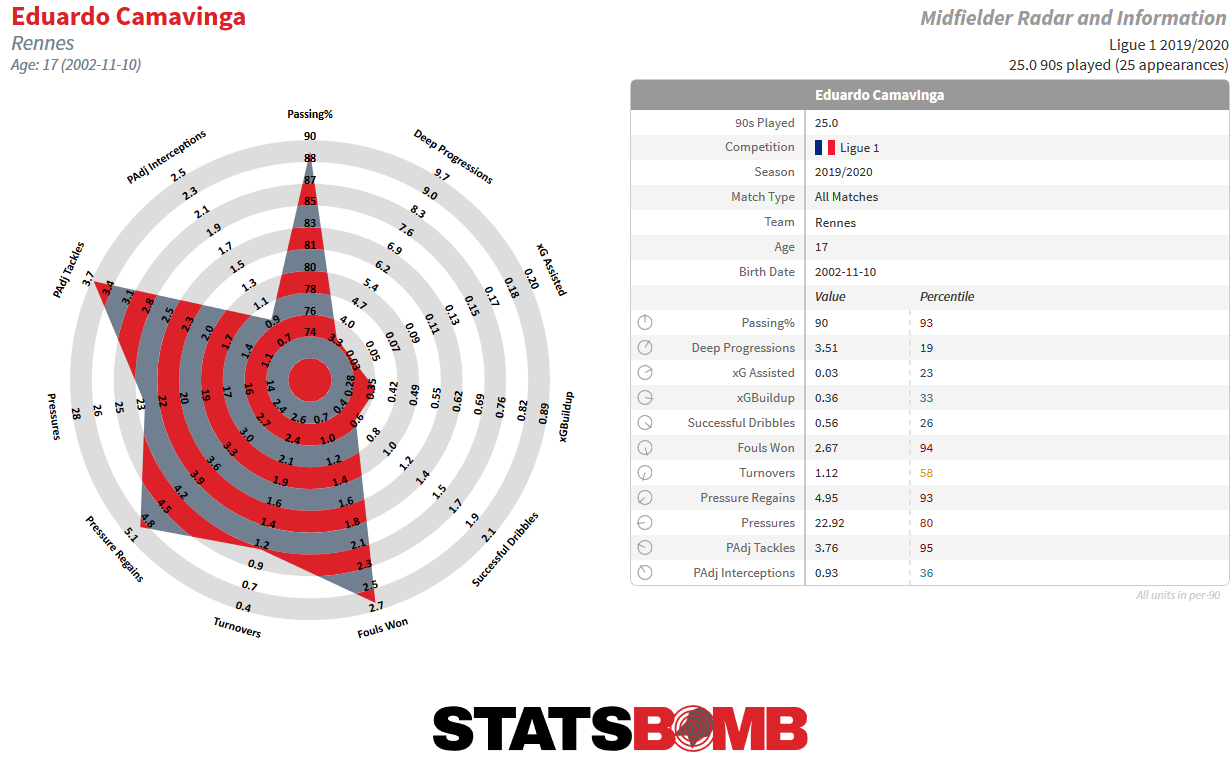

The team also needs a backup for Casemiro. Rennes’ Eduardo Camavinga profiles especially well. At just 17, he has been among the best defensive midfielders in Ligue 1. Zidane’s French connection could push the deal through:

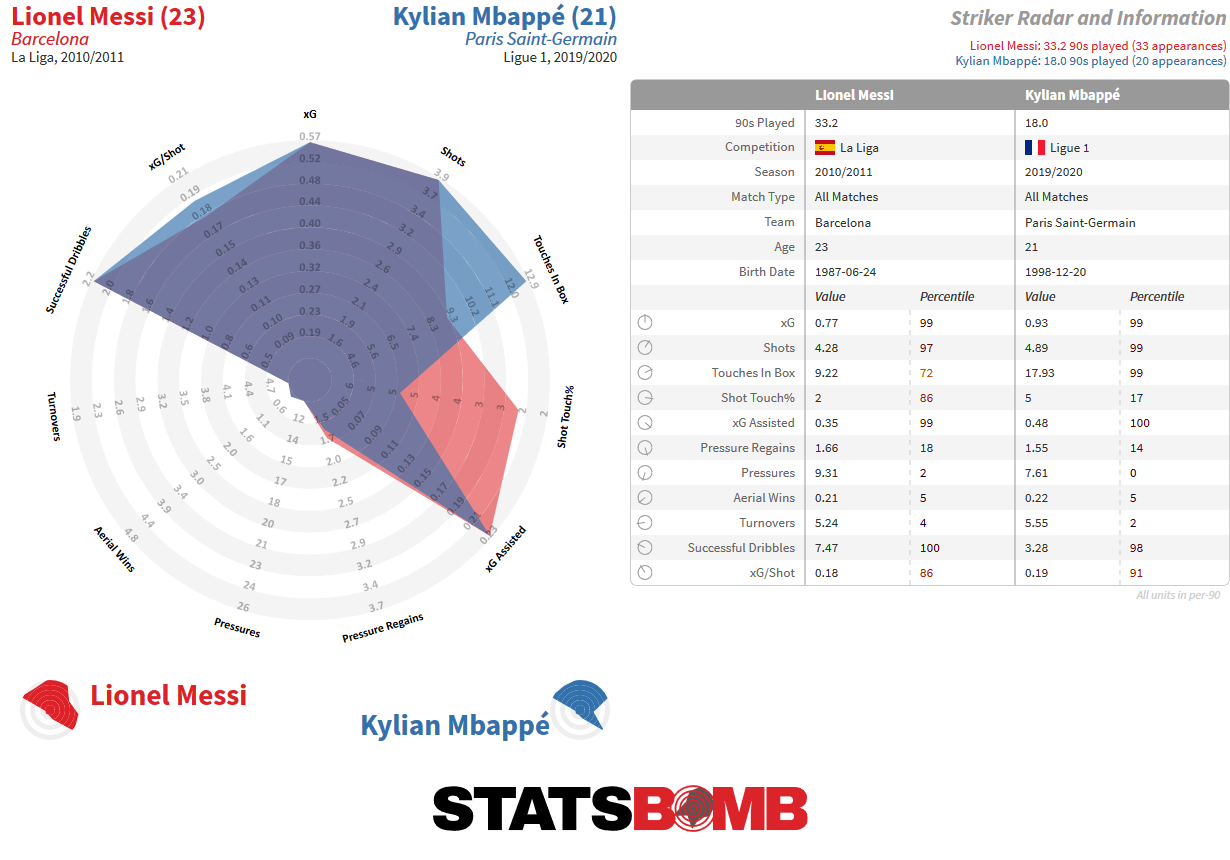

Lastly, Madrid have publicly courted Kylian Mbappe. The French superstar is now the most devastating goalscorer in the top 5 leagues. His production is historic:

Mbappe alone should shoot Real Madrid’s offense back to the levels of the Ronaldo era. That is likely Zinedine Zidane’s endgame.

Throughout the 1990s, the UEFA Cup was a favourite hunting ground of Italian teams, who took home 8 out of 11 trophies, and accumulated 14 total appearances in the final of the competition.

The 1998 UEFA Cup final between Inter and Lazio was the fourth - and so far the last - occasion in which two Italian teams competed for the trophy, a worthy epilogue to a season that has marked, even in controversy, the history of the two clubs and of all Italian football. At the beginning of that campaign, Massimo Moratti, in his third season as Inter's president, bought Ronaldo from Barcelona for the record sum of 50 billion lire. The previous season, Ronaldo had been Pichici with 34 goals and had scored a total of 47 goals in 49 games (or, if you prefer, 0.91 goals for 90, penalties excluded). The number nine of Moratti's dreams finally signed for a team, which could also count on a young Javiér Zanetti, Youri Djorkaeff and striker Iván Zamorano, among others.

Defender Taribo West, midfielders Diego Simeone and Benoît Cauet and winger Francesco Moriero also became Nerazzurri players that summer too. And finally, Moratti purchased also a 21-year-old Uruguayan fantasista with chubby cheeks and bowl-shaped hair, who made his debut 20 minutes before the final whistle of the first game of the season against Brescia, and overshadowed Ronaldo with two goals from a remarkable distance and bewitched his president with an irrational love. He was El Chino Álvaro Recoba.

For the managerial role, now left vacant by Roy Hodgson, Inter appointed Luigi Simoni, known as Gigi, unemployed after the end of a difficult relationship with Napoli president Corrado Ferlaino. He was a coach who still believed in rigid man marking and the use of the libero.

The Nerazzurri started off with 3 wins in the league and took the lone lead in Serie A, keeping it until match-day 17, when they were overtaken by Juventus, perhaps the strongest team in Europe at the time and not surprisingly a Champions League finalist.

The head-to-head with the Bianconeri continued until the direct clash at the Delle Alpi on April 26th, decided by a goal by Alessandro Del Piero, but, inevitably, also by a controversial body check between Mark Iuliano and Ronaldo, an event that became perhaps the most debated refereeing decision in the history of Italian football.

Moratti and Ronaldo's Scudetto dreams vanished with the final whistle and Inter were left to concentrate on the UEFA Cup, where they had reached the final, after a semifinal with Spartak Moscow, decided by two 2-1 wins and above all by Ronaldo's double in Russia.

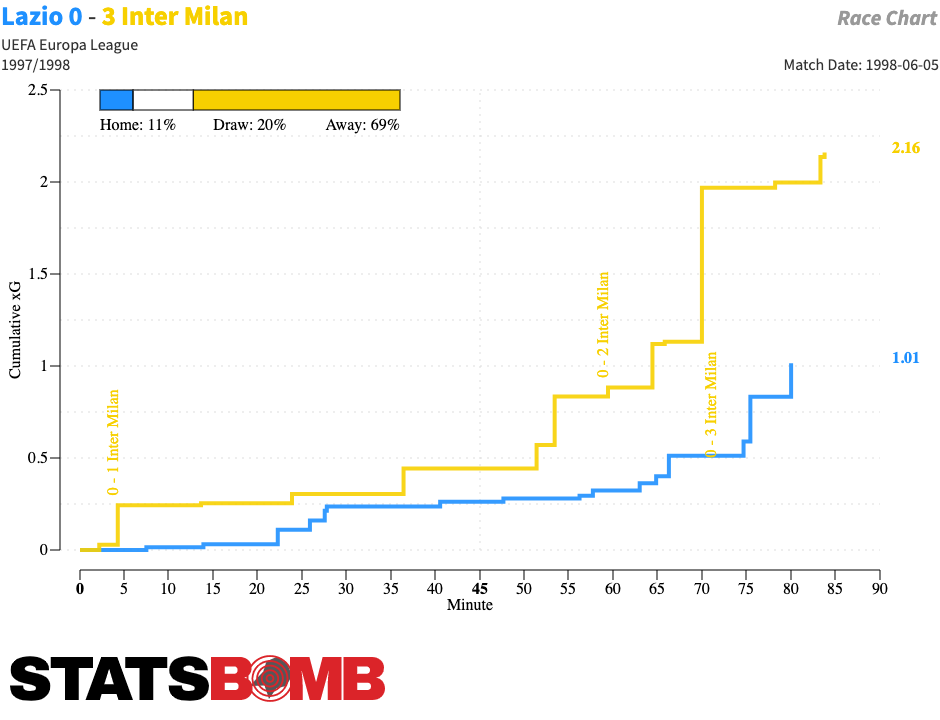

The other finalists were Lazio; a team that had thrashed the Nerazzurri 3-0 at the end of February and who had held title aspirations of their own deep into the season before, before a very bad final run of results, which saw the Biancocelesti lose at the Olimpico to Juventus and collect just one point in the last six games, eventually dropping to the 7th place in the standings.

Like Inter, Lazio had strengthened considerably behind the will of their owner Sergio Cragnotti, who had entrusted the team to Swedish coach Sven-Göran Eriksson. The former Sampdoria coach brought number 10 Roberto Mancini from Genoa, while the club snatched Vladimir Jugović and the prodigal son Alen Boksić from Juventus. The midfield was renewed with the arrival of Matías Almeyda, while the defence was bolstered with full-back Giuseppe Pancaro.

Among its ranks, Lazio also included the elegant 21-year-old defender Alessandro Nesta (whom Eriksson called the strongest player he trained at Lazio) and a 24-year-old Pavel Nedved, who was their top-scorer in all competitions--alongside Boksić--with 15 goals.

Though the league challenge was derailed, Eriksson retained the faith of Cragnotti and president Dino Zoff by winning the Coppa Italia against AC Milan, and laid the foundations for Lazio's 1999/2000 Scudetto. Their path to the UEFA Cup final was relatively straightforward and they arrived unbeaten and with just 3 goals conceded and 16 scored throughout the competition, beating Atlético Madrid in the semifinal.

By coincidence the day of the final, 6th May 1998 was also the date on which the club became the first Italian team to be listed on the stock exchange.

The game was held at the Parc des Princes in Paris, and was particularly important as a dress rehearsal of the 1998 World Cup that was just around the corner.

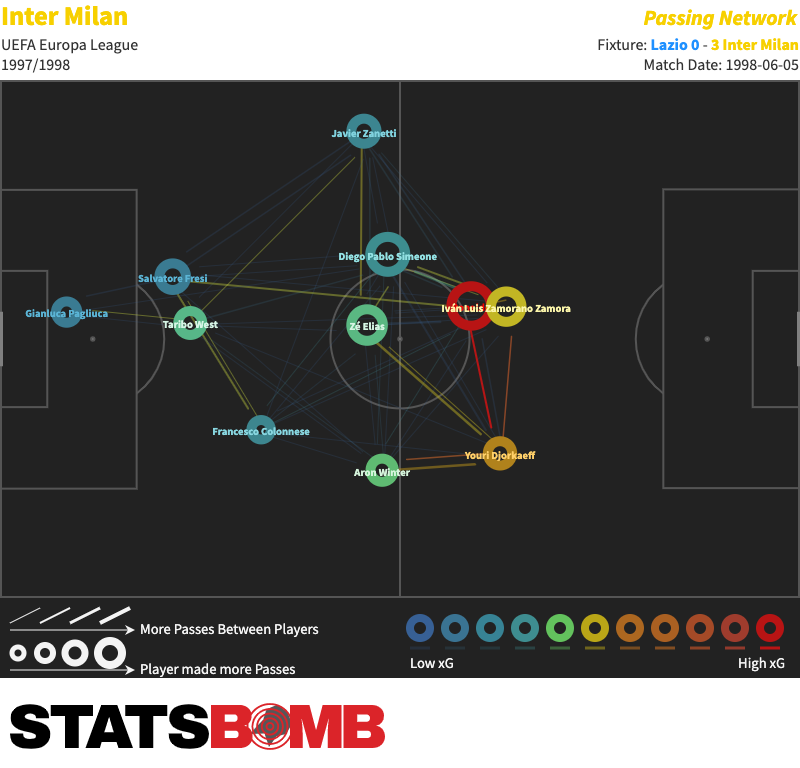

Simoni was forced to do without captain Giuseppe Bergomi and chose Salvatore Fresi for the role of the libero. West, Francesco Colonnese and Zanetti completed the defense in front of Gianluca Pagliuca’s goal. The four midfielders were arranged in a sort of diamond, with Zé Elias as the playmaker, Aron Winter and Simeone on his sides and Djorkaeff as the offensive midfielder. In attack, Ronaldo was paired with Ivan Zamorano.

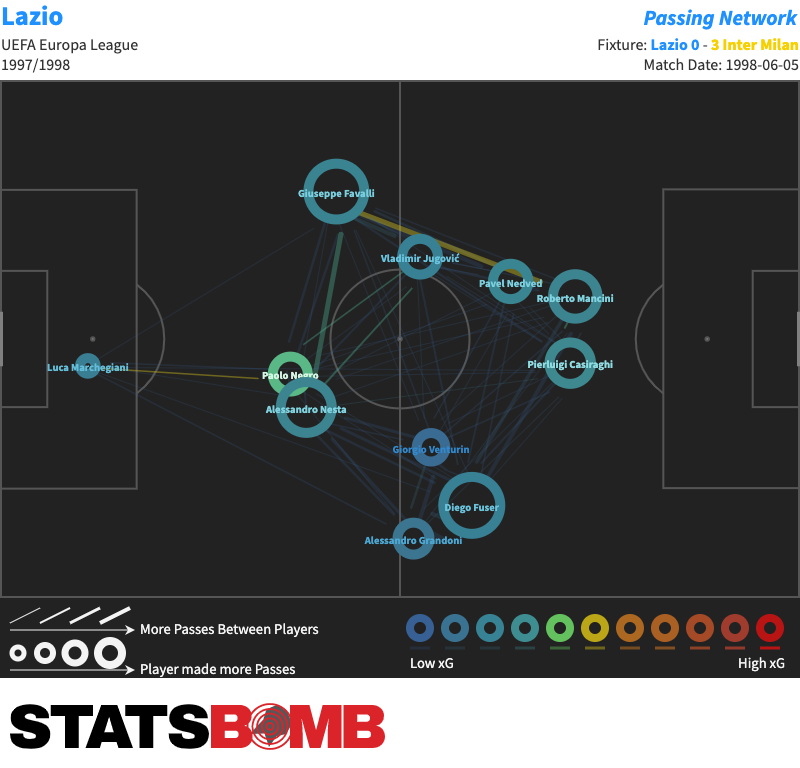

Eriksson was unable to call upon Boksić (who also missed the World Cup with a knee injury), and replaced him with Pierluigi Casiraghi. Alessandro Grandoni came in for Pancaro at right full-back. With Marchegiani in goal, the first line of the 4-4-2 was formed from right to left by the then Italy Under-21 right back, Nesta, Paolo Negro and Giuseppe Favalli. Giorgio Venturin and Jugović were the two central midfielders, with captain Diego Fuser wide on the right and Nedved on the left wing. Mancini acted as second striker behind Casiraghi.

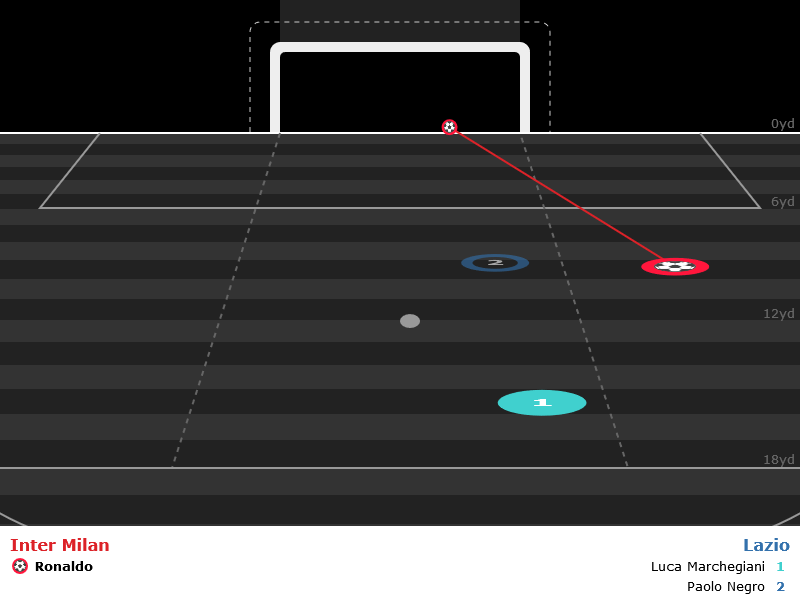

The deadlock was quickly broken. Simeone, left without pressure by Lazio, delivered a long ball behind the defense to Zamorano for the first goal of the game. The mistake of Erikisson’s defense was quite clear, as defenders were neither positioned to set an offside trap, nor were they running backwards as would have been advised by the situation.

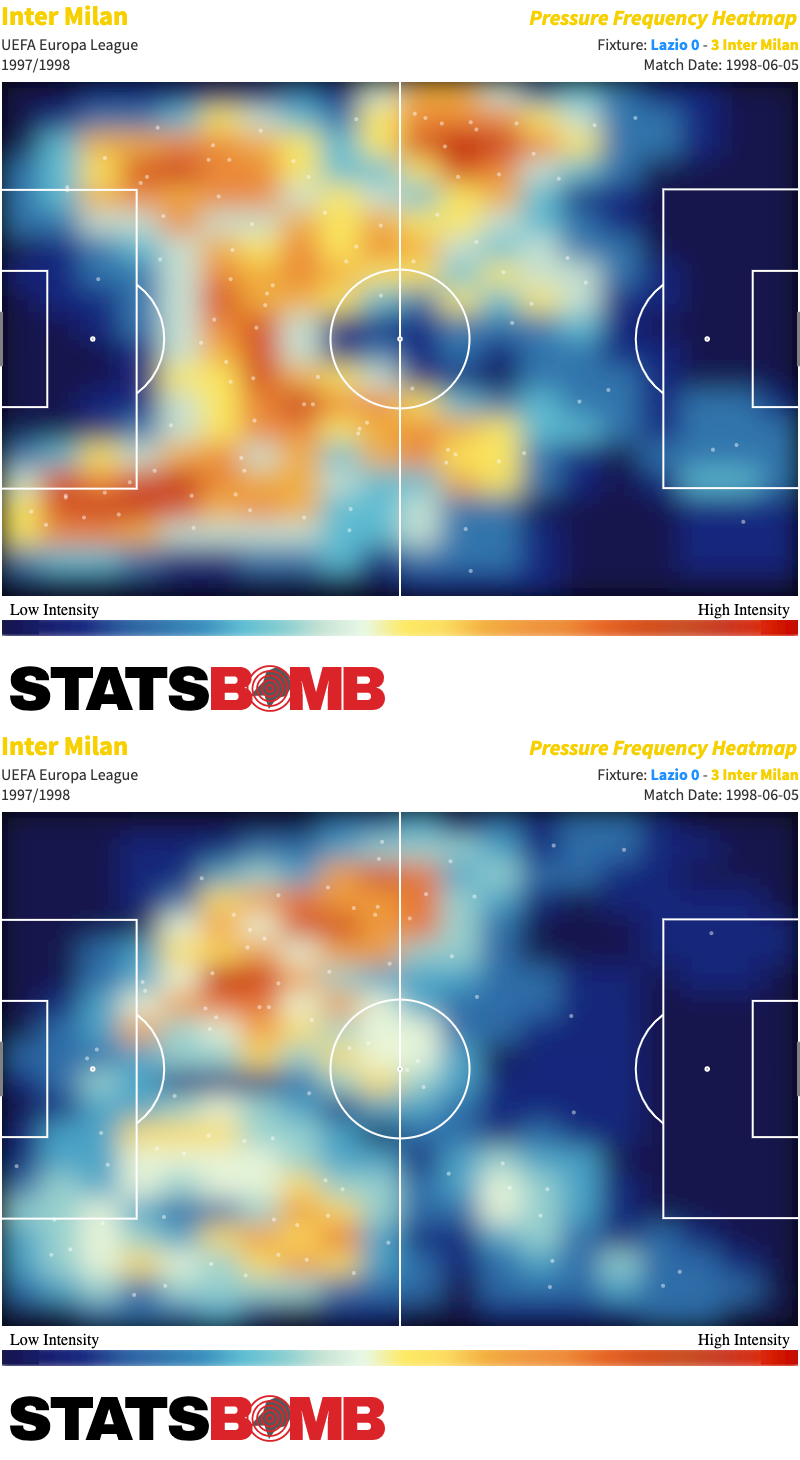

Both Inter and Lazio were two teams that were at their best when on the counter and after the 1-0 Simoni was very happy to leave the ball possession (63% to 37%) to his opponents. From the very beginning, however, the difference between the two coaches' defensive approach was also emblematic. Simoni's system of play was still strongly influenced by the mixed zone: in addition to the use of the libero, the man-marking applied by his team was rigid, so much so that the formation of Inter in the defensive phase was determined exclusively by the positions of the opposing players.

Without the ball, Fresi positioned himself behind the defensive line, with West marking Casiraghi and Colonnese with Mancini. Zanetti engaged a personal duel with Fuser right from the start, both defensively and offensively, while Nedved was marked by Winter, leaving Simeone and Zé Elias in numerical parity with Lazio's midfielders. Even in the defensive phase, Inter's formation was peculiar: Winter - who perhaps could have been a fullback today - offered a wide pass line, while Djorkaeff dropped on the right halfspace to balance their occupation of the field.

Eriksson, on the other hand, used a 4-4-2 with a zone defense, using a medium-low block in the defensive phase and without exerting particularly aggressive pressure on the opponent's ball carrier. There were moments in which Lazio compacted the two lines of 4 to reduce the space available on the side of the ball, but also those in which the Swedish coach decided to raise the pressing. In these situations, one attacker pressed the opponent's defender in possession and the other marked the closest pass option, while the midfield prepared to block passing lanes, with the aim of forcing a risky pass or a long ball.

During the offensive phase, Lazio used to rely heavily on its center forward, in this case Casiraghi, but Inter was also repeatedly looking for Zamorano. Reviewing the amount of long passes towards the two teams’ target men makes a certain effect and gives a clear idea of how much having a striker good in the air was important for almost all the coaches of the time, as well as how much football has changed since then.

Both Zamorano and Casiraghi probably had good strength in their aerial game and a trademark move in the header. However, the confrontation between the two was clearly in favor of the Chilean, who won 6 out of 10 aerial duels and assisted Zanetti’s goal with an headed pass, while Casiraghi came out as the winner only 3 times (33%), limited by West’s dominance on high balls (7 aerial duels won, 78% of the total).

If Casiraghi acted as the offensive focal point, Mancini would roam across the attacking front, looking for the combination with Fuser or Nedved, or alternatively to create dangers through dribbling or a first touch pass towards a running teammate. Even at 34 years of age, Mancini was still a useful player, but although he was second only to Nesta for touches in the game, during the match he was often neutralized by an excellent marking by Colonnese, whose performance was one of the keys to Inter's victory.

Although they had to overturn the result and thus control game with the ball, Lazio was a team built to play vertically. Nesta (134 touches) and Negro (92), rather than Venturin, were the players who controlled the rhythm of the game starting from the defense, deciding whether to accelerate with a play towards the strikers or to distribute the ball along the flanks. On the right side most of the responsibility for the progression of the game depended on Fuser, the Lazio player with the most dribbles (4) and passes in the last third (23), an throughout he did ran the inside channel, waiting for the overlap of Grandoni.

During the 2nd half the right back was also replaced by Eriksson with the more offensive Gottardi, perhaps to try to get to the touchline and cross with more consistency, as Fuser's movements on the inside attracted his marker Zanetti and left the left side of Inter's defense unprotected, where Fresi had to be the one to leave position intervene. On a couple of occasions Grandoni even had the time to receive the ball behind the defense, forcing the libero to save the situation with a desperate tackle. Nedved started wide on the left, but gradually moved inside the field, in part because of Winter's marking in the defensive phase, which saw him practically acting as the right wing back. Across the field, Jugović made similar movements.

Inter’s pressure heatmap in the 1st half (top) and the 2nd half (bottom)

Lazio came close to a draw in the first half, but Inter's defensive scheme, which bargained almost entirely on their superiority in individual duels, proved to be decidedly solid and more reliable than Eriksson's zone defense. Zamorano found another chance shortly after the start of the second half having beatne the offside trap, but it was a rare goal by Zanetti, perhaps the most beautiful and important of his career (alongside one in 2007/2008 against Roma) to double the Nerazzurri’s lead: a volley with the ball bouncing in his direction, which ended its trajectory on the top corner of the goal.

By now, the UEFA Cup was virtually on its way to Milan. All that was missing at that point was the Fenomeno’s signature on the trophy. And Ronaldo’s goal naturally arrived, when in the 70th minute he was served by Moriero, beat a close offside decision and scored to make it 3-0. An iconic run that ended with him dribbling past even Marchegiani.

The 90 minutes in Paris are illustrative of how Ronaldo was a unicorn before unicorns, a complete forward with a pioneering quickness that made him literally unplayable even in Italy, where the attention to the defensive phase – and it’s not a cliché - was much more accentuated than in the Eredivisie or La Liga. In 1998 Ronaldo was the future of football and his talents were timeless, he would be similarly feted today. We remember him as one of the best number nines of all time, but on that occasion, wearing the number 10, he played as a second striker, supporting Zamorano and helped the team in all areas of the pitch, despite having a talent several orders of magnitude greater than any of his teammates. The amazing aspect of this performance, which perhaps wasn't even the best in the competition compared to the semi-final against Spartak, was the magnetism he emitted.

Ronaldo eluded Gottardi twice and on the second occasion he sat him down with an “elastico” in one of the 5 dribbles completed in the final.

Ronaldo was Inter's mainstay in that match, being not by chance the player with the most touches or the most decisive player in chance creation. With only 3 shots, he accumulated 0.91 xG but if we examine his overall involvement with xG chain (xGc), a metric that measures the xG of all the actions in open play in which a player is involved, the figure rises even to 1.71 xGc (out of 2.16 xG overall).

If the 0.91 xG shows his ability to be in the right place at the right time, the remaining part of the metric is an indirect measure of the gravitational attraction that Ronaldo exerted on his opponents. The Brazilian was the "Phenomenon" but also the great facilitator of Simoni's Inter, able to generate superiority and consequently to open spaces and to create opportunities for his companions either directly or otherwise. This was an unique feature, which can only lead to an immediate comparison with Lionel Messi, perhaps the only other player able to attract opponents as if he were a celestial body.

We could dismiss the Paris final as the last triumph of an obsolete and reactionary football, almost a revamp of the mixed zone, on pure zonal defense and Eriksson's modern 4-4-2. But it would be a superficial assessment that would overlook how Simoni's Inter system, regardless of its ideological roots, was built to maximize Ronaldo's futuristic talent, without leading to tactical imbalances or bad moods in the locker room. A concept that transcends footballing eras and remains very relevant even in the age of "super teams" and "unicorns". And that explains how the gentleman coach of Crevalcore has remained one of the most beloved managers in the history of Inter, also for his undoubted bond with Ronaldo. That evening, in addition to the UEFA Cup, the Brazilian also won the bet to cut his coach's hair, shaving him with an electric razor.