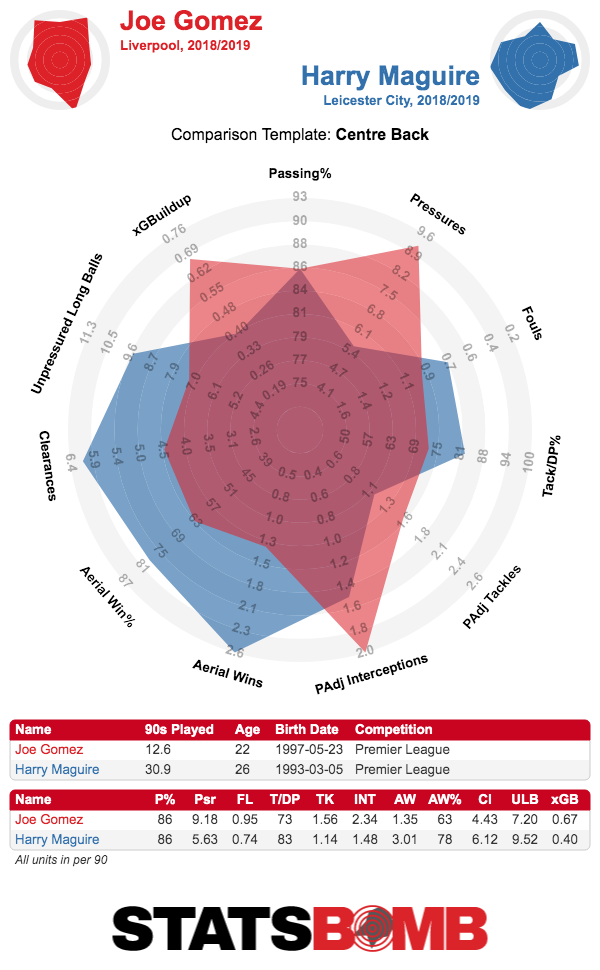

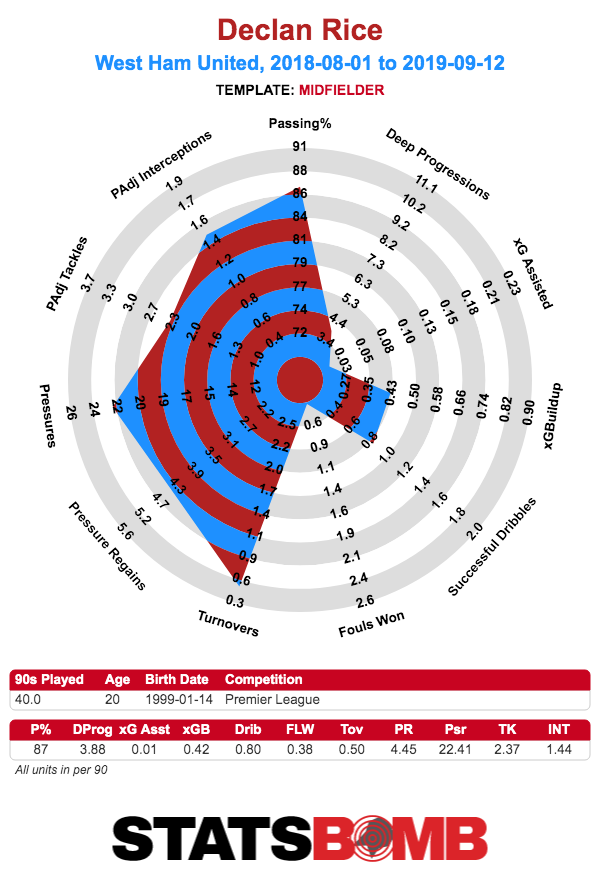

The Three Lions look well on their way to qualifying for next summer’s European Championships, but questions about the side’s approach remain. Gareth Southgate’s time in charge of England has certainly seen a lot of steps forward. “Adequate” is the word best used to describe the 2018 World Cup qualification process, with the Three Lions topping the group and making it to Russia very comfortably but without playing any memorable football or looking like a cohesive side in the process. England looked very much like a cohesive side in the World Cup itself, however, reaching the semi-finals for the first time since 1990 and, arguably more importantly, re-establishing an emotional connection with the public that had gradually drifted away over the past two decades. Without getting too much into whether it counts as a “proper” competition, the Nations League saw some real positives with England deservedly topping the group over Spain and Croatia, though a poor showing against the Netherlands in Portugal left a bitter taste in the mouth. As for the current challenge of the Euro 2020 qualifiers, it’s going rather well. England have won all four matches and already scored more goals than the ten game qualification process for the last World Cup. Southgate’s team are joint top scorers in the whole “tournament” so far, a feat made more impressive by the fact that they have played two fewer games than Belgium and France. This hasn’t stopped large swaths of the internet calling Southgate “clueless” for his team selections, but when the biggest complaint in a 4-0 win over Bulgaria is that the team didn’t do it with enough vigour, I think most managers would take that. Southgate has prioritised winning the fixtures and qualifying first and foremost, but since England are now all but sure to achieve that (one more win would do it with four games remaining), the question is no longer really about getting three points but building a platform to put together a competitive side next summer. In some regards progress has been made on this front, but there are still issues to deal with and questions about England’s approach even the manager doesn’t know the answer to. The biggest tactical shift in the past 18 months has been the move away from the 3-5-2 that England were known for in the World Cup to a more conventional 4-3-3. The previous shape had its positives, but was ultimately a way of avoiding some holes in the squad. It was particularly flawed when it came to creating chances in open play, and England relied heavily on set pieces to get the job done. At times, this is not as drastic a shift as it seems. The deepest midfielder in the three has generally dropped between the centre backs and England have thus been able to build with a back three. That the two holding midfield options Southgate has used, Declan Rice and Eric Dier, were both centre backs earlier in their careers is not an accident. In terms of progressing the ball forward, the full backs are important outlets aiming at a fluid interchangeable front three, while the central midfielders have been playing more industrious roles. There’s a heavy dose of Liverpool here, but the side has additionally been making use of more Manchester City style low crosses for poaching opportunities. Southgate is, if nothing else, a planner. It would be very uncharacteristic of him to now deviate from these principles before the European Championships. But questions about personnel and smaller details still remain. Defensively, Southgate made some selections in the 5-3 thriller against Kosovo that compounded issues. At right back, Trent Alexander-Arnold has obvious technical qualities and can be a vital cog if England are to rely on the fullbacks for ball progression, but he has his physical limitations and sides have at times exploited Liverpool in behind him. The main way this is resolved at club level is through the excellent pace of Liverpool’s centre backs, largely able to cover for him easily. Against Kosovo, he had Michael Keane and Harry Maguire. The split centre backs further asks Keane to defend in wide areas and it’s not clear that he’s capable of doing it. That Ben Chilwell was the only player who could really be called “fast” suggested the balance wasn’t right. Finding the ideal centre back paring is an issue where no one quite fits into the middle of the Venn diagram. Keane is dominant in the air, winning a fairly huge 4.69 aerial duels per 90 last season, and good enough on the ball, but too slow to turn and recover. Joe Gomez is extraordinarily fast for a centre back, but questionable in the air. His 63% aerial win rate last year doesn’t seem too bad, but mostly because he was contesting barely over two of them per 90, with Liverpool’s system designed to ensure that Virgil van Dijk sweeps that stuff up. John Stones is famously comfortable with the ball at his feet, but his physical limitations are exposed much more frequently with England than in Pep Guardiola’s incredible pressing system. My personal preference would be a Gomez/Maguire pairing as it seems to cover the most bases, though Southgate has been very fond of Stones in the past.  There could be an alternate solution if Kyle Walker starts at right back. Instead of the deepest midfielder dropping between the centre backs, he holds his position, and when the left back pushes forward, Walker, shuffles along with the centre backs. If you start Stones and Maguire, you’ve exactly recreated the back three from the World Cup. It doesn’t seem as though Southgate is considering this, in part presumably because it would require the right sided wide forward to move further out and keep the team’s shape on that side rather than come into the box, but it would be a potential way of building from 3 at the back while still starting with 4. But enough about that. The place everyone has been complaining about has been in midfield. Declan Rice and Eric Dier are not the most exciting players to occupy the deepest role. Both look every bit the converted centre backs at times. But this might be why Southgate is so likely to utilise one of them. He needs someone to split the centre backs, and at this moment in time Rice is ideal (sorry, Eric. We’re gonna need you to improve your form before you earn this spot back.) England have decent options in terms of ball playing centre backs so a lack of penetrative passing in this role shouldn’t be a huge issue.

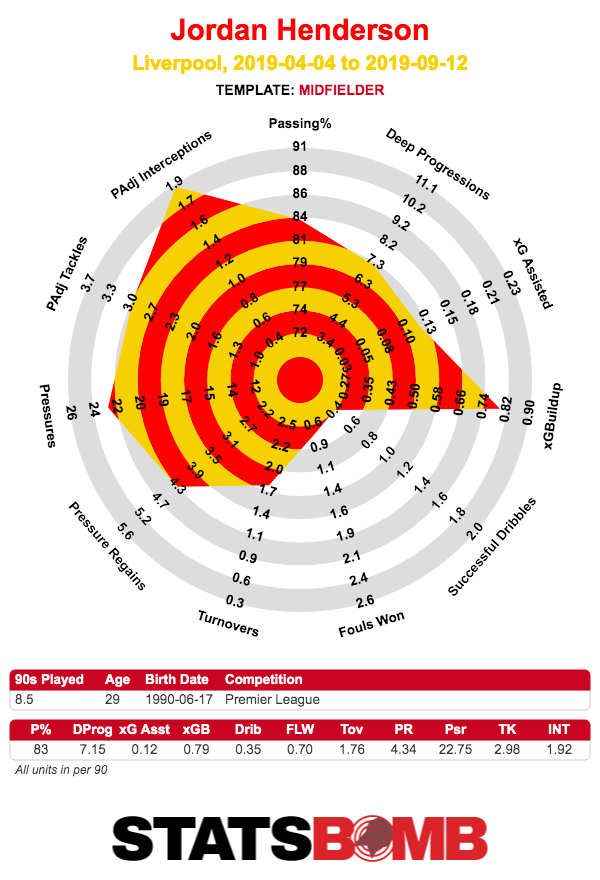

There could be an alternate solution if Kyle Walker starts at right back. Instead of the deepest midfielder dropping between the centre backs, he holds his position, and when the left back pushes forward, Walker, shuffles along with the centre backs. If you start Stones and Maguire, you’ve exactly recreated the back three from the World Cup. It doesn’t seem as though Southgate is considering this, in part presumably because it would require the right sided wide forward to move further out and keep the team’s shape on that side rather than come into the box, but it would be a potential way of building from 3 at the back while still starting with 4. But enough about that. The place everyone has been complaining about has been in midfield. Declan Rice and Eric Dier are not the most exciting players to occupy the deepest role. Both look every bit the converted centre backs at times. But this might be why Southgate is so likely to utilise one of them. He needs someone to split the centre backs, and at this moment in time Rice is ideal (sorry, Eric. We’re gonna need you to improve your form before you earn this spot back.) England have decent options in terms of ball playing centre backs so a lack of penetrative passing in this role shouldn’t be a huge issue.  It’s the two players in front of him where there is the most cause for concern. Jordan Henderson and Ross Barkley started in these roles against Bulgaria and Kosovo. Henderson has been reinvented as a roaming number 8 since April, and there are still some misnomers as to how he interprets the role. His main attribute is his runs forward, and he contributes plenty of defensive work in addition, while his passing is as solid-if-unspectacular as ever. But his positioning tends to be very aggressive. He makes a number of runs into the half spaces in the final third with the assumption that someone else will cover him. As he’s not quite as athletic as a few years ago, he can’t cover all the space himself. With England’s defensive midfielders not as energetic as he’s used to with Fabinho at Liverpool, this isn’t ideal for the team shape.

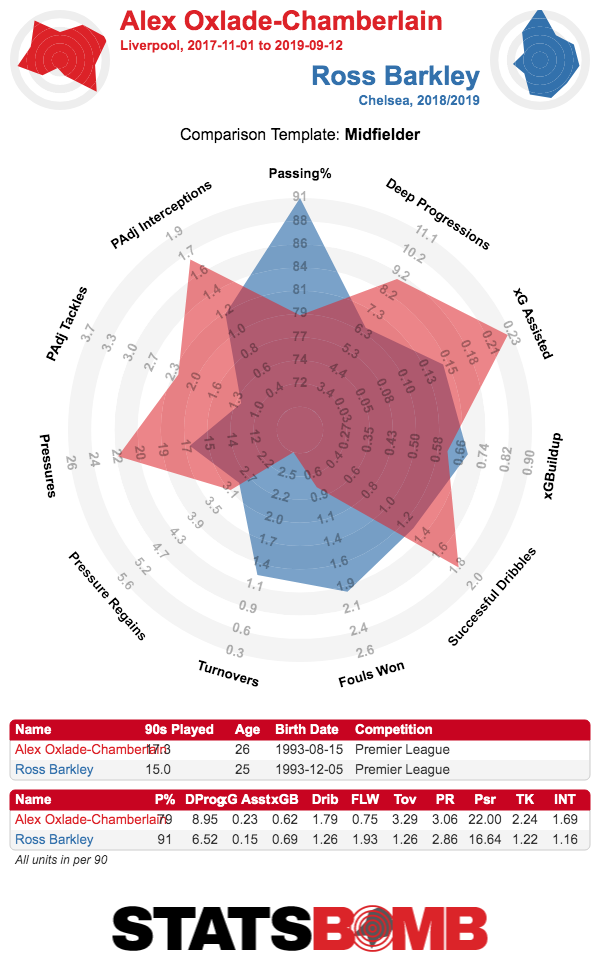

It’s the two players in front of him where there is the most cause for concern. Jordan Henderson and Ross Barkley started in these roles against Bulgaria and Kosovo. Henderson has been reinvented as a roaming number 8 since April, and there are still some misnomers as to how he interprets the role. His main attribute is his runs forward, and he contributes plenty of defensive work in addition, while his passing is as solid-if-unspectacular as ever. But his positioning tends to be very aggressive. He makes a number of runs into the half spaces in the final third with the assumption that someone else will cover him. As he’s not quite as athletic as a few years ago, he can’t cover all the space himself. With England’s defensive midfielders not as energetic as he’s used to with Fabinho at Liverpool, this isn’t ideal for the team shape.  Barkley is surely the most frustrating player to get regular minutes in this team. Against Bulgaria he looked reasonably effective, linking up with the forward line well. Against Kosovo, well, we all know his tactical understanding at this point. What summed it up for me was that, with the score at 5-3 and the aim surely being to slow things down and see out the result, Barkley was still attempting expansive passes and making runs into the box. If Southgate believes that a Barkley-like skillset is needed in this system, though, me might be wise to swap him out for Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. The Liverpool midfielder is coming off an awful long term injury, but the feeling seems to be positive that he’s made a good recovery, and this could be of use to England. He remains an underrated creative passer while his ability to drive forward with the ball at his feet is widely understood. He could solve a lot of problems in terms of breaking down sides and it’s good that he seems to be in Southgate’s plans.

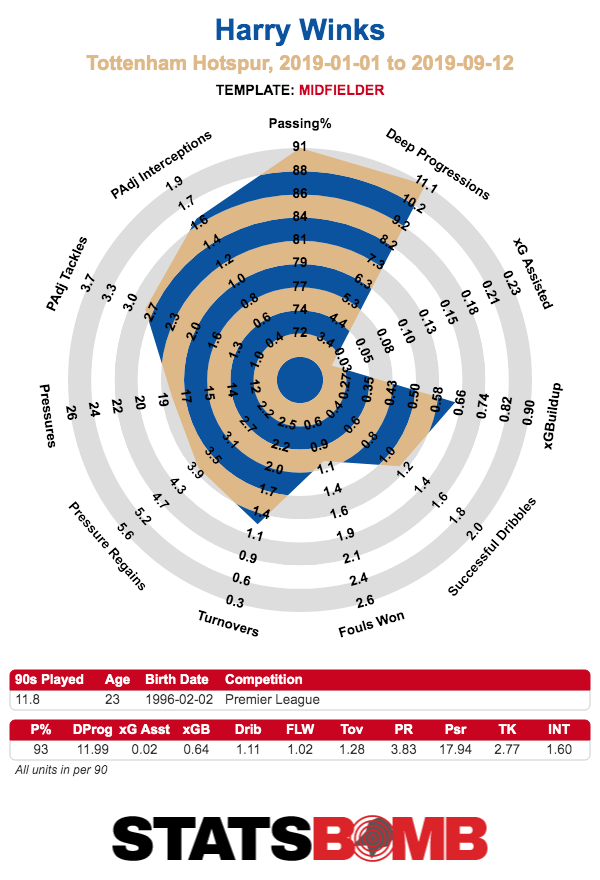

Barkley is surely the most frustrating player to get regular minutes in this team. Against Bulgaria he looked reasonably effective, linking up with the forward line well. Against Kosovo, well, we all know his tactical understanding at this point. What summed it up for me was that, with the score at 5-3 and the aim surely being to slow things down and see out the result, Barkley was still attempting expansive passes and making runs into the box. If Southgate believes that a Barkley-like skillset is needed in this system, though, me might be wise to swap him out for Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. The Liverpool midfielder is coming off an awful long term injury, but the feeling seems to be positive that he’s made a good recovery, and this could be of use to England. He remains an underrated creative passer while his ability to drive forward with the ball at his feet is widely understood. He could solve a lot of problems in terms of breaking down sides and it’s good that he seems to be in Southgate’s plans.  Harry Winks is the other player I would slot in here. England were particularly poor at keeping possession in midfield against Kosovo and that is the thing Winks does. He has become a very able high volume passer at Spurs, though more as a calm option rather than a true creator. He’d likely need to be fielded alongside someone more adventurous with England, but he can certainly help improve Southgate’s side with the ball.

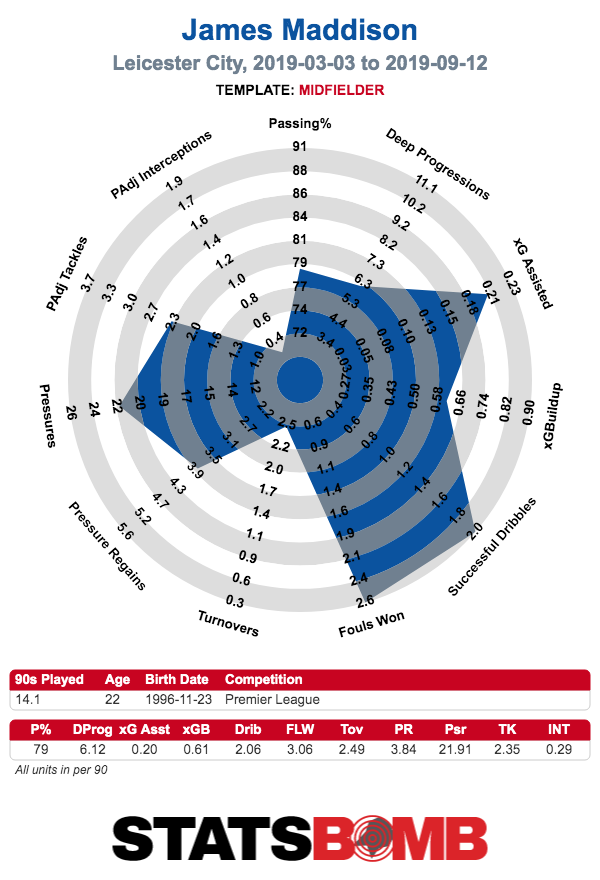

Harry Winks is the other player I would slot in here. England were particularly poor at keeping possession in midfield against Kosovo and that is the thing Winks does. He has become a very able high volume passer at Spurs, though more as a calm option rather than a true creator. He’d likely need to be fielded alongside someone more adventurous with England, but he can certainly help improve Southgate’s side with the ball.  Dele Alli remains, despite some of the hype going quiet on him, an outstanding option, though it’s not clear that this system suits him as there isn’t always space for him to move into the box. Nonetheless, he has a part to play. James Maddison seems to have become the public’s preferred choice here, and it’s not difficult to understand why. As a creative passing option. England have none better than the Leicester man. It’s easy to imagine previous England managers adjusting the set up to fit him in, but Southgate is reluctant to adjust his shape. For all Maddison’s talent, he does pose some tactical fit issues as he’s much more a classic number ten than an eight. He’s certainly an able worker, but in terms of fitting into a coherent midfield that holds its shape, he could be a problem. His club manager, Brendan Rodgers, seems to agree, fielding him in a more attacking role in bigger games. As much as he is among the eleven best English players right now, a role on the bench will probably have to do.

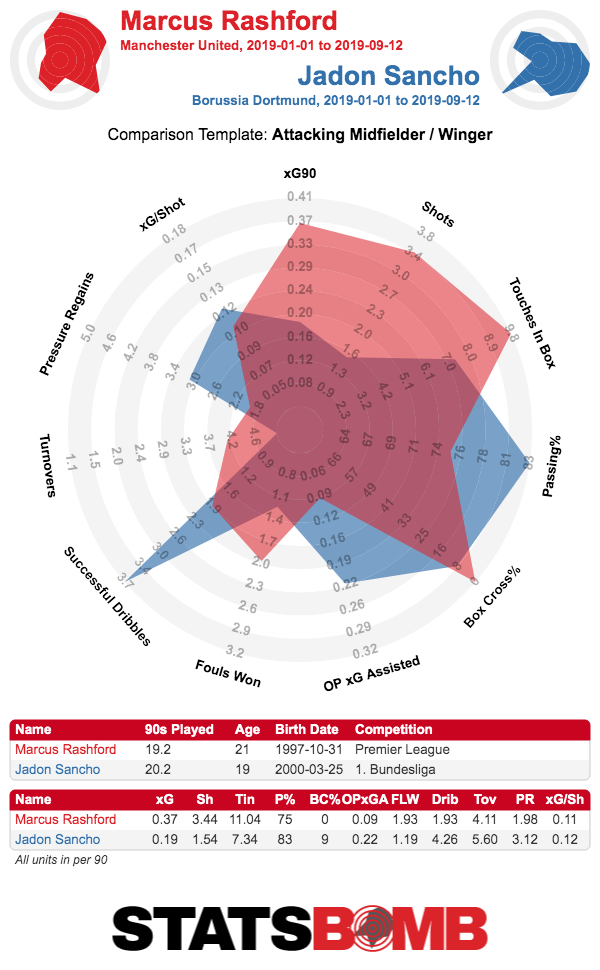

Dele Alli remains, despite some of the hype going quiet on him, an outstanding option, though it’s not clear that this system suits him as there isn’t always space for him to move into the box. Nonetheless, he has a part to play. James Maddison seems to have become the public’s preferred choice here, and it’s not difficult to understand why. As a creative passing option. England have none better than the Leicester man. It’s easy to imagine previous England managers adjusting the set up to fit him in, but Southgate is reluctant to adjust his shape. For all Maddison’s talent, he does pose some tactical fit issues as he’s much more a classic number ten than an eight. He’s certainly an able worker, but in terms of fitting into a coherent midfield that holds its shape, he could be a problem. His club manager, Brendan Rodgers, seems to agree, fielding him in a more attacking role in bigger games. As much as he is among the eleven best English players right now, a role on the bench will probably have to do.  Maddison could be squeezed into the front three, but you would hardly want to mess with something that seems to be working. Before the switch to the 4-3-3, Raheem Sterling had scored two international goals in 44 appearances. Since then, he’s on eight in eight. He may well cool off a touch, but he looks much more comfortable coming inside from a wide position. If nothing else, the formation change to the 4-3-3 is worth it for what it’s gotten out of him. What makes it even better is that he’s forming a connection with the other obvious star in this team, Harry Kane. Increasingly, Kane plays a slightly more withdrawn role for England than he does for Spurs, dropping deeper to receive the ball and creating space for the wide forwards to run into. Kane’s shot volume has dropped off at club level from his best seasons, but his link up play remains outstanding, so this seems to be best for everyone. Sterling and Kane have combined to create and score a goal five times in their last seven starts together, and the thought of the Three Lions’ two biggest names becoming a really potent pair is really something. Southgate doesn’t seem to have decided whether Jadon Sancho or Marcus Rashford will join the pair, and it’s understandable that he’s trying both as they’re such different options. Rashford is the more direct player, taking up narrower positions, running directly at goal and generating more shots. Sancho, on the other hand, is more of a high volume dribbler and creative passing threat. It’s understandable that the manager perhaps feels he trusts Rashford more, having worked with him over a longer period, but with two good shot generators already in Kane and Sterling, adding Sancho to dribble past opponents and put in low crosses at the byline feels like it gives the side a better balance.

Maddison could be squeezed into the front three, but you would hardly want to mess with something that seems to be working. Before the switch to the 4-3-3, Raheem Sterling had scored two international goals in 44 appearances. Since then, he’s on eight in eight. He may well cool off a touch, but he looks much more comfortable coming inside from a wide position. If nothing else, the formation change to the 4-3-3 is worth it for what it’s gotten out of him. What makes it even better is that he’s forming a connection with the other obvious star in this team, Harry Kane. Increasingly, Kane plays a slightly more withdrawn role for England than he does for Spurs, dropping deeper to receive the ball and creating space for the wide forwards to run into. Kane’s shot volume has dropped off at club level from his best seasons, but his link up play remains outstanding, so this seems to be best for everyone. Sterling and Kane have combined to create and score a goal five times in their last seven starts together, and the thought of the Three Lions’ two biggest names becoming a really potent pair is really something. Southgate doesn’t seem to have decided whether Jadon Sancho or Marcus Rashford will join the pair, and it’s understandable that he’s trying both as they’re such different options. Rashford is the more direct player, taking up narrower positions, running directly at goal and generating more shots. Sancho, on the other hand, is more of a high volume dribbler and creative passing threat. It’s understandable that the manager perhaps feels he trusts Rashford more, having worked with him over a longer period, but with two good shot generators already in Kane and Sterling, adding Sancho to dribble past opponents and put in low crosses at the byline feels like it gives the side a better balance.  For most of this millennium, England managers have prioritised individual talents. The question has usually been “how do we fit them all in?”. This approach felt like it hit its nadir in Euro 2016, when Roy Hodgson abandoned the ideas he’d been working on for the past two years to slot Wayne Rooney in a deeper midfield role, a position he had never played for England before the opening game. Memories of 2004 with Paul Scholes starting on the left of a midfield four to accommodate a double pivot (if the phrase can really be used for such attack minded players) of Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard still haunt some. Southgate saw all of these tournament failures up close, and he took notes. Some of those were in terms of dressing room culture, and it has been generally agreed that England now have a much better atmosphere around the place, with players entering games in a better mental state. But the changes extend to on the pitch as well. Past regimes would have seen all sorts of systems fiddled with to fit Maddison or Rashford into the starting eleven, without any cohesive tactical vision to back it up. Like it or not, Southgate has his plan and he won’t mess with it. England might not always put the best players out in a starting eleven, but that is not the aim. This is the first England side in a generation to have genuine tactical ideas that come first.

For most of this millennium, England managers have prioritised individual talents. The question has usually been “how do we fit them all in?”. This approach felt like it hit its nadir in Euro 2016, when Roy Hodgson abandoned the ideas he’d been working on for the past two years to slot Wayne Rooney in a deeper midfield role, a position he had never played for England before the opening game. Memories of 2004 with Paul Scholes starting on the left of a midfield four to accommodate a double pivot (if the phrase can really be used for such attack minded players) of Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard still haunt some. Southgate saw all of these tournament failures up close, and he took notes. Some of those were in terms of dressing room culture, and it has been generally agreed that England now have a much better atmosphere around the place, with players entering games in a better mental state. But the changes extend to on the pitch as well. Past regimes would have seen all sorts of systems fiddled with to fit Maddison or Rashford into the starting eleven, without any cohesive tactical vision to back it up. Like it or not, Southgate has his plan and he won’t mess with it. England might not always put the best players out in a starting eleven, but that is not the aim. This is the first England side in a generation to have genuine tactical ideas that come first.

2019

How can Gareth Southgate solve England’s tactical issues

By admin

|

September 12, 2019